Library of Congress's Blog, page 5

May 8, 2025

Raúl Ruiz, La Raza Collection Lands at the Library

This is a guest post by Zoe Herrera, an intern in the Office of Communications.

It’s the last half of the 1960s. The Vietnam War is at its height. Martin Luther King Jr. is assassinated. The battle for civil rights stretches across the country.

Passion, grief and change come with protests, riots and strikes.

That is exactly what journalist, photographer and activist Raúl Ruiz captured when he joined La Raza, a newspaper and magazine in East Los Angeles started by Chicano activists and creatives in the last half of the ’60s.

Ruiz and the magazine focused on covering the struggles of Chicanos (Mexican Americans), his photographs capturing the community’s mobilization that flourished despite hardships.

The Library will preserve that legacy, announcing today that it has acquired the Raúl Ruiz Chicano Movement Collection, some 17,500 photos by Ruiz and original page layouts for La Raza. It also has nearly 10,000 pages of manuscripts, which include original correspondence, the unpublished draft of Ruiz’s book on Los Angeles Times journalist Ruben Salazar and handwritten minutes from the staff meetings of La Raza.

“The Ruiz collection speaks to the heart of the Chicano movement and will be an important resource for the study of journalism and Latino history and culture at the Library of Congress,” said Adam Silvia, curator of photography in the Prints and Photographs Division.

A young child holding a sign at a Chicano protest in Los Angeles. Photo: Raúl Ruiz. Prints and Photographs Division.

A young child holding a sign at a Chicano protest in Los Angeles. Photo: Raúl Ruiz. Prints and Photographs Division.As an undergraduate at California State University, Los Angeles, Ruiz became active in student and community organizing during the height of the civil rights era. Once he began reporting for La Raza, it was apparent to him what role the publication played for the community.

“A lot of us wanted to bring out the truth of who we were,” Ruiz recalled years later on “Artbound,” a documentary series by Public Broadcasting SoCal. “We wanted to come out with our own news, with our own version, with our own story.”

As the Chicano community in East L.A. began to mobilize, so did La Raza’s staff. They covered school walkouts, marches and the police crackdowns that often came along with those protests.

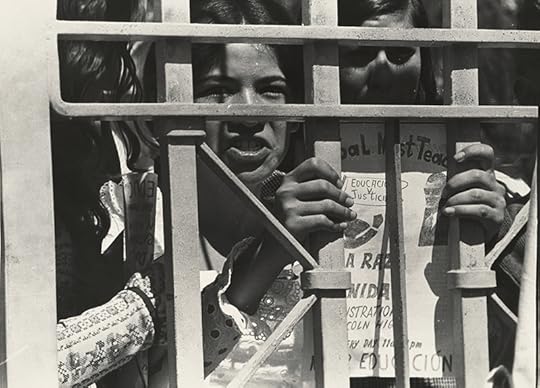

Protesters gather for at protest for education reform in Los Angeles in the late 1960s. Photo: Raúl Ruiz. Prints and Photographs Division.

Protesters gather for at protest for education reform in Los Angeles in the late 1960s. Photo: Raúl Ruiz. Prints and Photographs Division.During a school walkout, Ruiz tried to intervene when a student was being violently arrested by police.

“I was taking pictures,” Ruiz said on the “Artbound” series. “Taking pictures of the kids, taking pictures of the cops, of things that were going on and acting responsibly as a journalist.”

His attempt to deescalate the situation led to him being thrown in the back of a squad car and beaten by police in an alley. He came back and kept reporting, though, as police arrested 13 more protesters. Among them was Sal Castro, a high school teacher accused of disturbing the peace.

Ruiz, La Raza and the greater East L.A. Chicano community followed Castro’s detainment and eventual release. When the local board of education refused to allow Castro to teach again, Chicano activists held sit-ins at the school board. Some three dozen activists, including Ruiz, stayed after being told they’d be arrested if they didn’t leave.

“Determined to make our point clear, and our commitment clear, we were willing to risk arrest,” Ruiz said in the documentary.

The school board eventually allowed Castro back into the classroom, but other events ended in tragedy.

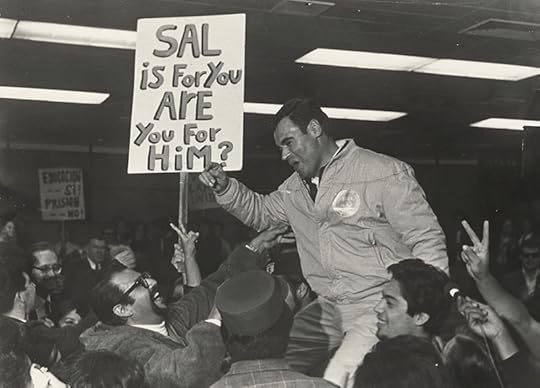

Crowd celebrates activist and teacher Sal Castro. Photo: La Raza staff. Prints and Photographs Division.

Crowd celebrates activist and teacher Sal Castro. Photo: La Raza staff. Prints and Photographs Division.In August of 1970, more than 20,000 people marched as part of the National Chicano Moratorium in East Los Angeles to protest the disproportionate number of Mexican American soldiers dying in Vietnam. Ruben Salazar, the most famous Mexican-American reporter of his generation — he was the news director at a local television station and a well-known columnist at the Los Angeles Times — was also covering the event.

Police had moved in, the protest was becoming chaotic and Ruiz was taking pictures of police firing tear gas canisters into the open doorway of the Silver Dollar bar. One canister hit Salazar in the head, killing him. It became a major event in the Chicano movement, particularly as police were never charged with any wrongdoing.

“I kept thinking, ‘Oh my god, we were there,’ ” Ruiz said in the documentary.

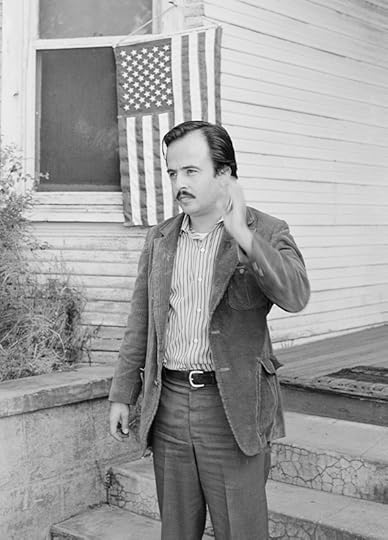

Raúl Ruiz in Los Angeles around 1971. Prints & Photographs Division.

Raúl Ruiz in Los Angeles around 1971. Prints & Photographs Division.Ruiz’s photographs ran on the on the front page of the L.A. Times and have since become well known. His images from the Moratorium, some of which have become part of the permanent collections at institutions such as UCLA and now at the Library, served as visual testimony of the violence inflicted on peaceful protestors.

After La Raza’s dissolution in 1977, Ruiz became a college professor, teaching Chicano studies and journalism at CSU, Northridge until his retirement in 2015.

Ruiz died in 2019. He was 79. He left a legacy as a witness, a storyteller and an early voice of the Chicano movement. He captured a critical era in American history from the perspective of those who lived it. His work is a testament to the idea that journalism, at its best, can be a revolutionary act.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 5, 2025

Ashley Dickerson, Powerlifting Librarian

Ashley Dickerson is the acquisitions and cataloging librarian for Finland and the Baltic states.

Tell us about your background.

I was born in Washington, D.C., and lived in the area my entire life. My family is from North Carolina. I studied anthropology at the University of Maryland, College Park. My focus was biological anthropology with a subfocus in archeology and a minor in creative writing. I’ve been at the Library for most of my professional career. I started as a work-study student during my senior year of high school at Forestville Military Academy, left for college and came back as a contractor in 2013 after I graduated.

What brought you to the Library, and what do you do?

I told myself when I was a workstudy student in the Regional Cooperative Cataloging Division (RCCD) that I wanted to come back, because I truly enjoyed this place. I worked with so many languages. I always had an interest in languages prior to that experience, but what I learned deepened my interest. I worked with Japanese, Korean, Mandarin Chinese, Persian, Arabic and Hebrew. At the time, I had studied Spanish and French in school and Finnish on my own, so all of the newer languages were so exciting. I went off to college, but I never forgot the Library. I visited when I could, and I always made sure to see who came and went. I made sure to always find David Maya Hernandez. He was my rock in RCCD when I was growing up, and now we work together in the Germanic and Slavic Division. For me, working at the Library was meant to be, I think.

What are some of your standout projects?

My favorite would have to be the DK Reclassification Project for the Baltic states. DK is the classification for the history of Russia, the Soviet Union and former Soviet Republics. Most of the countries I work with (Finland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) were occupied by Imperial Russia, the Soviet Union or both. Finland was occupied by Imperial Russia from 1809 to 1917. The Baltic states were occupied by Imperial Russia from the late 17th century to 1918 and by the Soviet Union from 1940 to 1990. Regardless of their independence, those countries were classed in the DK schedule. Finland moved to the DL schedule, which covers northern Europe and Scandinavia, during the late 1970s and early 1980s. But the Baltic states remained under DK even though their independence from the Soviet Union was restored between 1990 and 1991. Last year, I was asked if the Baltic states would be receptive to reclassification. I asked when I could start. I’d wanted to begin with at least Estonia when I first became a librarian in 2017, but I did not yet have the knowledge to make the massive changes needed. I’m passionate about what I do and enjoy the countries that I work with, so this to me is important work. The DK Reclassification Project did not start with the Baltic states — it began with Ukraine, which was moved from under the history of Russia to the history of Ukraine. But when I complete the project for the Baltic states, hopefully later this year, I will consider it one of my major achievements.

What do you enjoy doing outside of work?

I enjoy finding new restaurants to go to with friends. Food is culture, and sharing a meal with someone is to see them, know them and love them. I’m truly a nerd at heart. I’m always watching a new anime or trying to tackle my manga backlog, but I keep adding four titles for every one I take off my list. It’s a toxic cycle.

What is something your coworkers may not know about you?

I did archery and kendo in college. I want to get back into archery, but judo and powerlifting have my attention at the moment.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 2, 2025

Ada Limón’s Final Lecture as Poet Laureate: “You have to love.”

Winding down her historic two- term, three-year appointment as the 24th U.S. poet laureate, Ada Limón defended poetry as a tool for courage, personal healing and community connection.

More than a farewell, her final lecture last week in the Coolidge Auditorium was a love letter to poetry, to libraries and librarians and to the collective soul of a country still learning how to feel. Her lecture, titled “Against Breaking: On the Public and Private Power of Poetry,” framed poetry as a shared, not solitary, experience and as a celebration of humanity’s range of voices and perspectives at its core.

Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden praised Limón as “one of the greatest voices of this century” and said her work “has helped to extend and deepen the Library’s outreach and partnership, moving us closer to the vision of connecting all Americans.”

Limón’s signature project as poet laureate, “You Are Here,” involved creating permanent poetry installations in seven national parks.

Through a collaboration with NASA, she also composed the first poem ever to launch into space — it began its journey to Jupiter’s moon Europa last year engraved on NASA’s Europa Clipper. Limón recalled visiting communities across America as poet laureate and meeting people who turned to poetry as solace or a lifeline during grief, isolation or transition. She met a grandfather who memorized poems and left them to his grandchildren before he died and a woman born in Mexico who wrote poems in Spanish and translated them into English to witness the world in two languages. People told her about carrying poems in their back pockets, reading them in hospitals, at funerals, or writing them again after years of silence.

Addressing the rise of AI and its role in creating art, Limón noted that poetry’s true value is its human element and unrivaled power in capturing human experiences and providing comfort and understanding. She praised libraries as sacred spaces and repositories of memory “for anyone with curiosity to learn and explore.”

Limón’s lecture carried a quiet undercurrent of activism in uncertain times, not loud or preachy, but rather to stress the power of words to bring people together. Looking out into the packed auditorium, the soft-spoken poet encouraged people to “stand in poetry” to gather courage and find hope and strength again.

“If you need to be reminded of what makes us human, tender, brave, flawed and worthy of love, then you need poetry.…You do not have to love poetry, but you have to love something; even simpler: You have to love,” she said, drawing a rousing ovation.

In an interview, Limón, 49, said she has always believed in poetry’s enduring power to help people connect.

“My whole life, I really felt that,” she said. “As a kid, I was very moved by going to poetry readings at the local bookstore, and I felt that it was important to hear poetry out loud.”

Limón’s lecture was a reminder that the ancient art of poetry still holds a vital place in society.

“As she said, the right poem can make us recommit to the world,” said Karen González, a member of Tintas DC, a group of budding Hispanic writers in the Washington, D.C., area. Limón, an award-winning author of six books of poetry, is the first Latina to serve as U.S. poet laureate. Her latest book, a compilation of new and earlier poems, will come out in September.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

April 25, 2025

The Librarian as Hero: Ainsworth Spofford

“Know ye,” Lincoln proclaimed on New Year’s Eve in 1864, “That reposing special Trust and Confidence in the Integrity, Diligence and Discretion of Ainsworth R. Spofford of Ohio, I do appoint him Librarian … .”

Spofford would serve as Librarian of Congress for over 32 years — a period during which, thanks largely to his drive and vision, the Library grew into a position of national prominence.

At the time of Spofford’s appointment, the Library was a small institution that served only Congress. The Boston Public Library, Boston Athenaeum and Astor Library in New York City were bigger, as were the Harvard and Yale libraries.

The Library wasn’t in good shape, either. Dust coated everything, Spofford noted, large numbers of books needed repair and the collections suffered “remarkable deficiencies” — the newest encyclopedia available to members of Congress was 20 years old.

Spofford argued for more funding and bigger, more current collections. He expanded the Library’s physical space in the Capitol. Working with Congress, he centralized all copyright activities at the Library, adding two copies of every copyrighted work to the collections, enormously expanding their size and range.

With the collections growing quickly, the Library soon needed more space. Spofford doggedly lobbied for the Library to get a building of its own — today’s magnificent Jefferson Building.

He also supplied the Library with something new and important: a vision of the institution as a library, not just for Congress, but for the nation and its citizens. More than 160 years after Spofford first took the job, the Library still holds his vision — a library for all.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

April 21, 2025

A Precious Bible Blessed By Pope Francis at the Library

-This is a guest post by Courtney Pomeroy, a social media specialist in the Office of Communications.

In 2015, when Pope Francis became the fourth pope to visit the U.S., he blessed a modern masterpiece of a Bible that was then donated in his honor to the Library.

As the world mourns the pontiff, we wanted to share this beautiful artifact and remember that special moment.

The pope’s time in the U.S. was filled with all the pomp befitting a papal visit. He was greeted by huge crowds in each city of his six-day trip: Washington, New York and Philadelphia.

President Barack Obama and the first family escort Pope Francis from the tarmac at Joint Base Andrews. Official White House photo by Pete Souza.

President Barack Obama and the first family escort Pope Francis from the tarmac at Joint Base Andrews. Official White House photo by Pete Souza.The journey began just outside the nation’s capital at Joint Base Andrews on Sept. 22, where he was received by President Barack Obama and his family. Two days later, he made history as the first pope to address a joint session of Congress.

Later that same day on Capitol Hill, Pope Francis was present for the donation of an Apostles Edition of The Saint John’s Bible — the first entirely handwritten and illuminated Bible commissioned by a Benedictine monastery in more than 500 years.

Commissioned by St. John’s University and St. John’s Abbey in 1998 and directed and overseen by Donald Jackson, a British master calligrapher, it is a 1,130-page, seven-volume, art-filled edition of the Bible. Its vellum pages are 2 feet tall, and the open volume measures 3 feet across. Jackson and his team used the ancient crafts of calligraphy and illumination but brought the book to life with the help of modern tools and understandings of world history. The project took 13 years and was completed in 2011.

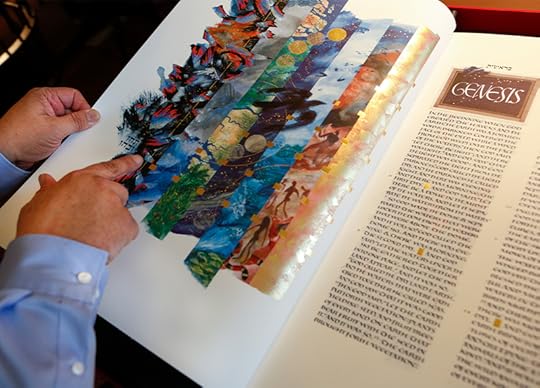

The structure of this illumination reflects the seven-day progression of the Bible’s creation story, with seven vertical strips, one for each day. Photo: Shawn Miller.

The structure of this illumination reflects the seven-day progression of the Bible’s creation story, with seven vertical strips, one for each day. Photo: Shawn Miller.St. John’s holds the original manuscript version of the Saint John’s Bible. Just twelve precious “Apostles Editions” were also created. They reside at institutions such as the Library, the Vatican Museum and Library and the Morgan Library.

St. John’s Abbey and St. John’s University donated a copy to the Library in 2015 to mark the papal visit.

“The Library of Congress is truly honored to receive this priceless work of human creativity and divine inspiration in honor of Pope Francis’ visit,” said then-Librarian James Billington.

The Library’s copy was then put on display in the Jefferson Building for three months. Parts of it were also on display during a 2006 national tour while it was being made.

The Bible is now part of the Library’s extensive collection of holy texts of many religions from around the world, including one of only three complete vellum copies of the Gutenberg Bible and the Giant Bible of Mainz.

The Gutenberg Bible on display at the Library. Photo: Shawn Miller.

The Gutenberg Bible on display at the Library. Photo: Shawn Miller.“The St. John’s Bible is a rare work of art and a commemoration of divine inspiration in honor of Pope Francis,” said Carla Hayden, the Librarian of Congress. “The Library of Congress is honored to have it as part of our special collection after His Holiness blessed it during his visit to Washington, D.C., in 2015. The Bible is now available to researchers for study as part of the Library’s extensive collection of Bibles and religious texts from all the world’s religions.”

In a lecture at the Library in 2016, Tim Ternes, director of The Saint John’s Bible, spoke about the creation of the Bible. He detailed how Jackson had dreamed of creating a handwritten and illuminated Bible since childhood and brought the idea to the monks at Saint John’s Abbey in 1995 as a way to mark the millennium.

The idea moved from there and 20 years later, a copy was blessed by Pope Francis. It is now preserved at the Library for future generations.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Keeping Your Powder Dry

“Keep your powder dry” has been a military maxim for at least 400 years. But how was one to do this in an age when gunpowder had to be manually loaded into an unsteady firearm, outdoors and in a hurry?

Let us now praise the lowly cow (or ox) horn, savior of many a soldier, hunter or marksman in need of a handy supply of the stuff at a moment’s notice. The light, hollowed-out horn, with a base and spout tamped in, was ubiquitous among early colonists to the United States, so much so that they needed a way to identify their personal horn.

Which brings us to praising the artisans, cartographers or just a bored guy with a knife, all of whom whiled and whittled away many an afternoon in turning a utilitarian object into a personal work of folk art: the engraved powder horn.

Three of the Library’s powder horns on display. Geography and Map Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Three of the Library’s powder horns on display. Geography and Map Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.The Library has 10 brilliant pieces of these relics of frontier life in the Geography and Map Division. The Library’s are all from the 1750s to early 1800s, just before they began to be replaced by paper cartridges. The Library’s well-preserved pieces, like the tens of thousands that filled the countryside during the Revolutionary War era, are carved with an array of images: maps, houses, cityscapes, trees, animals, birds or personalized motifs.

“ABEL CHAPMAN AND HIS HORN – MAID (sic) IN PROVIDENCE,” reads the inscription on one 1777 horn from Rhode Island, engraved with etchings of many buildings, a church and roads. Another has scenes from around the state of New York.

“During the mid-eighteenth century practically every American male owned a powder horn for hunting or military service,” wrote John S. duMont in “American Engraved Powder Horns,” a 1978 book that explores the history and art of the horns. “Ornamental as well as useful, the powder horn was almost as necessary a part of a man’s dress as his shoes or hat.”

Animal horns had been used for thousands of years, either to blow signals or to store almost anything – ink, snuff, grease, water – so gunpowder was a natural addition, particularly as a horn could be easily made water and spark proof.

“Robert Kelmn’s Horn,” one of the 18th-century engraved powder horns in the Library’s collection. The drawing of the horse and rider seems to be carved by a different artist. Geography and Map Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

“Robert Kelmn’s Horn,” one of the 18th-century engraved powder horns in the Library’s collection. The drawing of the horse and rider seems to be carved by a different artist. Geography and Map Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.On the armament side, the first firearms of any sort were made in China in the 10th century. By the time the 14th century rolled around, Europeans were using them and, as this tradition developed, matches, flashpans, wheel locks and flintlocks were the stuff of gun play from the from then until roughly the first third of the 18th century, when Samuel Colt patented his mass-produced, multi-firing revolver.

Until then, when gunpowder was doled out from large kegs to individuals, the gunman needed a way to mark his horn so that he could get it back. And so horn etchings, like their cousin scrimshaw art engraved onto bone or ivory, began to move from the prosaic to the ornate.

The outline typically was first penciled or penned onto the horn, then cut in with a needle, knife or graver. They could be quite elaborate. Officers and gentlemen often posed for portraits with them by their side.

Powder horns faded after paper and then metal cartridges were introduced. By the outbreak of the Civil War, they were history, save for a few hunters who pined for the old days. Still, they tended to be keepsakes.

“The soldier prized his horn, the companion piece of his musket, and invested it with the same romantic appeal,” wrote Stephen V. Grancsay, curator of arms and armor for the Metropolitan Museum of Art in his 1945 book, “American Engraved Powder Horns: A Study Based on the J.H. Grenville Gilbert Collection.” “In times of peace, horn and musket usually hung over the kitchen fireplace, a constant reminder of fighting days and campaigns against the Indians.”

Their long afterlife endures in museums and private collections, showing up at auctions and on antique websites, a reminder of who we used to be and how we used to live.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

April 17, 2025

Book(s) Burning: The Library Survived Two 19th-Century Fires

This article also appears in the March-April issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

The Thomas Jefferson Building has awed visitors ever since it opened its doors in 1897. The grand building is more than a marvel of art and architecture, though; it’s also a monument to function and safety — fire safety in particular.

It was built that way. For good reason.

Not once, but twice, within the decades preceding the building’s design, the Library literally went down in flames.

On Aug. 24, 1814, during the War of 1812, British troops set fire to government buildings in Washington, D.C. The Library’s 3,000 or so reference books, then housed in an unfinished U.S. Capitol, provided ready fuel for the fire.

The following year, Congress purchased the 6,487-volume library of former U.S. President Thomas Jefferson to replace the lost collection.

But just a decade later, those volumes, too, narrowly escaped complete destruction. On Dec. 22, 1825, Congressman Edward Everett detected a strange glow coming from windows in the Capitol on his way home from a late-night dinner.

A candle had been left burning in one of the Library’s galleries. The fire that erupted left the Library, “so lately one of the most beautiful rooms you ever saw … a sad spectacle,” Everett wrote.

Yet, no books perished that could not be replaced.

On Christmas Eve 1851, the Library was not so lucky. A chimney fire burned through about 35,000 of the roughly 55,000 volumes the Library had accumulated by then — including two-thirds of the books from Jefferson’s collection.

“The precious accumulations of more than 30 years have been reduced, in one short, melancholy hour, to a mass of black cinders,” The Union newspaper in Washington, D.C., lamented.

These catastrophes were front of mind in 1873 when Librarian of Congress Ainsworth Rand Spofford publicized a design competition for a new Library of Congress building.

All parts of the new building, he advised prospective architects, must be “of fire-proof materials, no wood being employed in any portion of the structure.”

Thanks to painful lessons from the 19th century, the Jefferson Building has not suffered a significant fire since it opened.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

April 14, 2025

College Records Add New Depth to Women’s Genealogy

-This is a guest post by Candice Buchanan and Wanda Whitney in the History and Genealogy Section. Buchanan wrote the first entry; Whitney, the second.

Lucy Lazear, the valedictorian of her 1853 graduating class at Waynesburg Female Seminary in Pennsylvania, paused her commencement speech to thank Margaret Bell, a key member of the faculty.

“That sisterly devotion which labored so ardently for our good — making our interests her own, that affectionate sympathy which joined in all our sorrows, that sweet gentleness which calmed every ruffled feeling, forgave every error, and threw a mantle of charity over our weaknesses, all contributed largely to hallow our school days,” Lazear said, no doubt delighting her teacher and touching the crowd.

Today, the student-thanks-inspirational-teacher moment is standard feature of commencement speeches, but Lazear’s was strikingly original. Women were just being allowed to attend colleges and universities in significant numbers (powered by the seminary movement, designed to train women to become teachers and educators), and their intellectual, personal and professional lives were beginning to blossom in ways that would change American society.

In turn, the records female students left behind at these early institutions created a genealogical window into women’s lives that had not previously existed. For decades to come, school was an exceptional period of independence for women. It was often the only time when they were identified as individuals, rather than someone’s daughter, wife or mother.

So today at the Library, and at university and local libraries across the country, we can find a unique trove of material about those young women in their own right — matriculation cards, course catalogs, graduation programs, minutes of literary societies and other social organizations, newsletters, yearbooks and alumni directories.

Within the larger community, school activities and interactions prompted targeted newspaper ads, articles and social columns. The networks of classmates and friends formed at school created letters, photograph albums and autograph books. All of this rich background fleshes out the individual lives of women in ways that we would not otherwise know.

Lucy, for example: She was born Sept. 23, 1835, in Greene County, Pennsylvania, where she appears in the 1850 census as a 15-year-old student in the household of her father, future U.S. Rep. Jesse Lazear. The Waynesburg Female Seminary was founded in 1849 by the Cumberland Presbyterian Church, just one year after the historic women’s rights convention at Seneca Falls, New York.

The family was comfortable; Thomas, her brother, was enrolled at Harvard.

Meanwhile, Lucy found that her seminary offered classes in grammar, rhetoric, algebra, trigonometry, geography, history, physiology, botany, chemistry, political science and religious studies. There were options to study languages: Greek, Latin and French.

Lucy excelled at her studies and, one can tell, chafed at the limitations of the era. In her handwritten valedictory speech (preserved in the Waynesburg University archives, along with the rest of her papers), she called on the school’s trustees to “open the fields of Literature to the female as to the male.”

She joined the faculty two years later, teaching instrumental music. The seminary soon was abandoned, as Waynesburg College began offering a coeducational curriculum, resulting in bachelor’s degrees for women and men by 1857.

She did not live to see the day.

Her papers show that she met and fell in love with Kenner Stephenson, her brother’s Harvard classmate. They were married on New Year’s Day, 1856, and the couple departed on a bridal trip in an open sleigh, crossing the frozen Ohio River. She contracted a cold and returned to Waynesburg. She died April 6, 1856, just 20 years old.

Without her college papers, how little we would have known of her short, vibrant life.

—Candice Buchanan.

Thaye Ann Richards Kearns graduation yearbook photo. Photo: Helianthus, the Randolph-Macon yearbook.

Thaye Ann Richards Kearns graduation yearbook photo. Photo: Helianthus, the Randolph-Macon yearbook. In modern times, college documents helped me flesh out the experiences of Thaye Ann Richards Kearns, a family friend, fellow church member and an older classmate at Randolph-Macon Woman’s College (now Randolph College).

Ann, who would devote her life to early childhood education, was in college during the turbulent years of 1965 to 1969, when the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War were convulsing the country. She was a mathematics major, but I was able to track down much more about her from the historical records, many of them here at the Library.

For starters, she played a key role in the university’s integration, as she was one of the first two Black women admitted as regular students in 1965, as documented in “Maconiana,” a history of the college.

The school’s weekly newspaper, The Sundial, which has been digitized as part of the Virginia Newspaper Program, Virginia Chronicle, was a key source in documenting Ann’s college days, as was its yearbook, Helianthus. The annual course catalogs were invaluable. Taken together, these helped me understand what life was like for Ann and other students — dorms had maids! laundry service! — and the social milieu in which she came into adulthood.

“Your attire is to be classic,” The Sundial reported in a tongue-in-cheek editorial aimed at new students the year Ann arrived, “however, this excludes those types of drapes known by the public as ‘shifts’ because it has been called to the attention of the management that these kangaroo-pocketed apparels have been known to camouflage cups of ice and bubble gum, pretzel sticks and M&Ms.”

Ann, the records make clear, was a serious young woman. She participated in the Young Women’s Christian Association, served as the secretary in 1966 and as co-head of current issues in 1967 and helped plan the Y’s poverty symposium that year. She also worked with underprivileged children one summer in the Madison Streeht Project sponsored by four area churches and served on a committee to study religious life at the college. The yearbook showed that she was secretary of the Baptist Student Union.

So while I began to see that faith and service were a large part of who she was, I also knew she had her fun — she was in the yearbook as a member of the Gammas, one of the school spirit groups.

The most important information — Ann expressing herself — appeared in newspaper articles. She was quoted in 1968 when asked how she felt about the local high school band being banned from playing “Dixie,” the ode to the Confederacy: “It glorifies the old South and for some people this has unpleasant memories.”

After college, Ann went on to get her master’s degree in education from Trinity College (now Trinity Washington University) and worked as an early childhood education teacher and specialist in Maryland and Kentucky. She died in 2021, at 74.

To me, the most telling words Ann had to say about her life in college came years afterward. She was interviewed at length in a 2019 Sundial piece, “Looking Back: Desegregation Through the Lens of R-MWC.” In the interview, Ann described how some students and even faculty expressed hostility about Black students being on campus, but that she had an unforgettable experience.

“I met some wonderful people and formed lasting relationships,” she said. “I was involved in meaningful activities on campus and in the Lynchburg community with the YWCA. I was able to gain confidence through the respect I earned and the honors I achieved, e.g., Who’s Who. It was a profoundly pivotal period in my life.”

Thanks to these college records, we know so much more about how she came to be who she was.

—Wanda Whitney

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

April 9, 2025

Take a “Fast Car” to the 2025 National Recording Registry

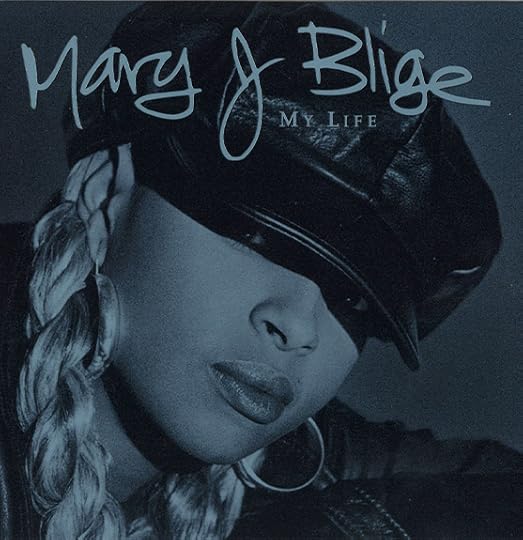

Elton John’s monumental album “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road,” Chicago’s debut “Chicago Transit Authority,” the original cast recording of Broadway’s “Hamilton,” Mary J. Blige’s “My Life,” Amy Winehouse’s “Back to Black,” Microsoft’s reboot chime and the soundtrack to the Minecraft video game phenomenon headline the 2025 class of the National Recording Registry.

The annual list of 25 recordings named as treasures worthy of preservation for all time based on their cultural, historical or aesthetic importance in the nation’s recorded sound heritage was announced by Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden.

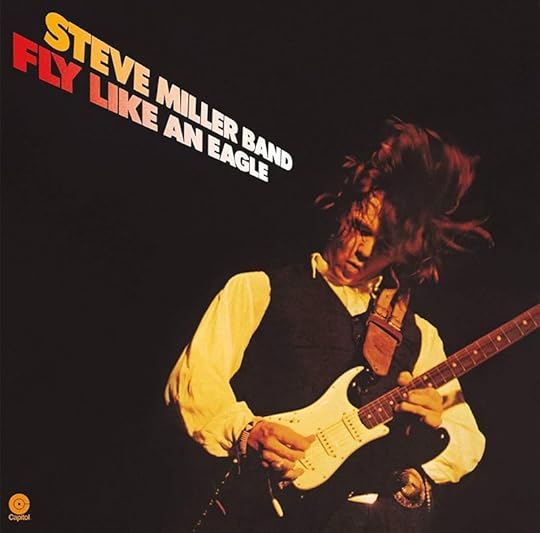

The 2025 class of inductees also includes Tracy Chapman’s self-titled debut album, which featured her timeless hit, “Fast Car.” There’s also Celine Dion’s 1997 single “My Heart Will Go On” from the blockbuster film “Titanic,” Roy Rogers and Dale Evans’ classic “Happy Trails,” Miles Davis’ jazz fusion album “Bitches Brew,” Charley Pride’s groundbreaking “Kiss an Angel Good Mornin,’” Vicente Fernandez’s enduring ranchera song “El Rey,” Freddy Fender’s breakthrough song “Before the Next Teardrop Falls” and the Steve Miller Band’s “Fly Like an Eagle.”

“These are the sounds of America – our wide-ranging history and culture,” Hayden said. “The National Recording Registry is our evolving nation’s playlist,” Hayden said.

More than 2,600 nominations were made by the public this year for recordings to consider for the registry. “Chicago Transit Authority” finished No. 1 in the public nominations this year. Other selected recordings in the top 10 of public nominations include “Happy Trails,” “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road” and “My Life.”

The recordings selected for the registry this year bring the number of titles on the registry to 675, a fraction of the national library’s vast recorded sound collection of nearly 4 million items.

Elton John, the 2024 winner of the Library’s Gershwin Prize for Popular Song with his songwriting partner Bernie Taupin, reflected on their 1973 album “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road.”

“Nobody really knows what a hit record is,” John told the Library.” I’m not a formula writer. I didn’t think ‘Bennie and the Jets’ was a hit. I didn’t think ‘Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me’ was a hit. And that’s what makes writing so special. You do not know what you’re coming up with and how special it might become.”

The Steve Miller Band blew up the charts in 1976 with the album “Fly Like an Eagle.”

The Steve Miller Band blew up the charts in 1976 with the album “Fly Like an Eagle.”Steve Miller’s “Fly Like an Eagle” sounded like a natural hit when it blew up pop charts in 1976, but it was three years in the making.

“When it came time to actually record it, I did something very unusual,” he said in an interview. “I used three different bands, three different sessions to record it.”

Mary J. Blige recalled her 1994 soulful hip-hop album “My Life.”

“My favorite lyric from the ‘My Life’ album is ‘Life can be only what you make of it,’” she said.

Mary J. Blige’s 1994 album “My Life” joins the NRR this year.

Mary J. Blige’s 1994 album “My Life” joins the NRR this year.The latest selections named to the registry span from 1913 to 2015. Ten of this year’s selections are from the 1970s. The earliest recording on the list is the long-beloved Hawaiian song “Aloha ‘Oe,” recorded in 1913 by the Hawaiian Quintette. The original Broadway recording of “Hamilton” by Lin-Manuel Miranda and the cast from 2015 becomes the newest recording to join the registry.

The 2025 selections span the sounds of folk, jazz, country, pop, comedy, sports, Latin, dance, R&B, tech, choral and musical theater. The recording from Minecraft is only the second video game soundtrack to join the registry, following the theme from Super Mario Brothers, selected in 2023.

“This year’s National Recording Registry list is an honor roll of superb American popular music from the wide-ranging repertoire of our great nation, from Hawaii to Nashville, from iconic jazz tracks to smash Broadway musicals, from Latin superstars to global pop sensations – a parade of indelible recordings spanning more than a century,” said Robbin Ahrold, chair of the National Recording Preservation Board.

The NRPB was created by Congress the National Recording Preservation Act of 2000; the registry list began in 2002.

NPR’s “1A” will feature selections in the series “The Sounds of America” about this year’s list, including interviews with Hayden and several featured artists in the weeks ahead.

The complete 2025 list:

“Aloha ‘Oe” – Hawaiian Quintette (1913) (single)“Sweet Georgia Brown” – Brother Bones & His Shadows (1949) (single)“Happy Trails” – Roy Rogers and Dale Evans (1952) (single)Radio Broadcast of Game 7 of the 1960 World Series – Chuck Thompson (1960)Harry Urata Field Recordings (1960-1980)“Hello Dummy!”– Don Rickles (1968) (album)“Chicago Transit Authority” – Chicago (1969) (album)“Bitches Brew” – Miles Davis (1970) (album)“Kiss An Angel Good Mornin’” – Charley Pride (1971) (single)“I Am Woman” – Helen Reddy (1972) (single)“El Rey” – Vicente Fernandez (1973) (single)“Goodbye Yellow Brick Road” – Elton John (1973) (album)“Before the Next Teardrop Falls” – Freddy Fender (1975) (single)“I’ve Got the Music in Me” – Thelma Houston & Pressure Cooker (1975) (album)“The Kӧln Concert” – Keith Jarrett (1975) (album)“Fly Like an Eagle” – Steve Miller Band (1976) (album)Nimrod Workman Collection (1973-1994)“Tracy Chapman” – Tracy Chapman (1988) (album)“My Life” – Mary J. Blige (1994) (album)Microsoft Windows Reboot Chime – Brian Eno (1995)“My Heart Will Go On” – Celine Dion (1997) (single)“Our American Journey” – Chanticleer (2002) (album)“Back to Black” – Amy Winehouse (2006) (album)“Minecraft: Volume Alpha” – Daniel Rosenfeld (2011) (album)“Hamilton” – Original Broadway Cast Album (2015) (album)Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

April 8, 2025

Catching up with … Eileen J. Manchester

Eileen J. Manchester is manager of the Lewis-Houghton Civics and Democracy Initiative in the Professional Learning and Outreach Initiatives office.

Tell us about your background.

I grew up in Charlotte, North Carolina, and attended the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. I studied English, French and German, which was my way of cobbling together a bachelor’s degree in comparative literature, even though my university didn’t offer it as a major.

I was always drawn to language and literature because, from my own experiences, I know that language shapes the way we view and make meaning of the world.

I was very lucky to have pivotal research experiences early in my academic career, using the archives at the Bibliothèque nationale de France and the British Library to uncover the story of a 16th-century French poet whose daughters published her work after her death.

Inspired by my mom’s second career in higher education, I simultaneously sought experiences in teaching. I tutored at my local library, interned at the Freedom School Partners literacy program in Charlotte and traveled to South Africa to learn more about its education system.

I then continued my studies of early modern women writers at the University of Oxford with the support of the Ertegun Graduate Fellowship in the Humanities.

At Oxford, I worked in local schools and libraries as a tutor and gained experience on various public humanities projects. As much as I loved historical research and analysis, I always knew I wanted to work in a role where I would be enabling other people’s learning as well.

What brought you to the Library, and what do you do?

While in graduate school, I had the privilege of connecting with two mentors (relationships lasting to this day!) who worked at the Library and opened my eyes to a career path in education and cultural heritage.

I was fortunate to land a position as a junior fellow in summer 2018. After the fellowship, I worked full time as a high school English teacher in Washington, D.C., then returned to the Library in the summer of 2019.

After five years as an innovation specialist in the Office of the Chief Information Officer, I joined the Professional Learning and Outreach Initiatives office in the Center for Learning, Literacy and Engagement. I manage the Lewis-Houghton Civics and Democracy Initiative, which is a new addition to the Library’s longstanding Teaching with Primary Sources Program.

Grants awarded under the initiative fund educational projects that use primary sources and approaches related to music and the arts to engage students in learning about history, civics and democracy.

What are some of your standout projects?

I consider every encounter with one of our Lewis-Houghton partners a standout moment, because I always come away with more knowledge about the Library’s primary sources and the many creative ways they can be used for teaching and learning.

One particular highlight took place at the 2024 National Council for the Social Studies conference. Our partners are not only music education and arts integration experts — they are musicians themselves. One of the teams flexed its musical muscles and performed “Do Doodle Oom,” a 1923 song by Fletcher Henderson and His Orchestra. It was amazing to see the Library’s collections brought to life in this way!

Another standout project was being detailed to the Informal Learning Office as part of the Leadership Development Program.

I had the privilege of working with fabulously talented colleagues to launch “Family Day,” the new monthly Saturday program for families and young audiences. The program just turned one — you can read about it in the Feb. 14 Gazette!

What do you enjoy doing outside of work?

While “enjoy” is a strong word, I am pursuing my Ph.D. in education and human development at George Mason University. I recently advanced into the dissertation phase and am very grateful to continue to grow and develop as a scholar. I also love to read, travel, visit museums, spend time with family and take long walks with my dog and husband.

What is something your co-workers may not know about you?

English is not my first language! I was born in Germany and grew up speaking mostly German until we moved to the U.S. when I was five years old. I also learned French in school and am constantly looking for language partners. Please be in touch!

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers