Library of Congress's Blog, page 3

July 21, 2025

Antrim’s Mexican Journey, a 19th-century Time Capsule

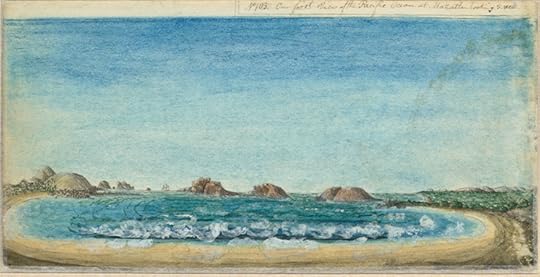

Their route took them on a guided trek by packhorse across Mexico, passing through plains and rich agricultural valleys, rocky mountain passes, small towns and grand cities. Antrim recorded the journey in three diaries and two sketchbooks that trace his experience at sea and then camping and moving overland from Tampico via San Luis Potosí and Guadalajara, ending in April at Mazatlán with his first sighting of the Pacific Ocean.

Antrim was impressed by the natural landscapes and built environments, architecture, design, feats of engineering and infrastructure, and he sketched as often as he could. He found geology, stones and minerals intriguing and wrote of crops, trees and the types of foods available in local markets. He observed class differences and noted the varied receptiveness of people to Americans that his group encountered. He saw poverty as well as prosperity and experienced the social authority of the Mexican military and the Catholic Church.

Antrim drew grand views of the changing and often epic geography. He also captured the intricacies of Spanish colonial architecture, cathedrals, government buildings, plazas, parks, haciendas and city landscape design.

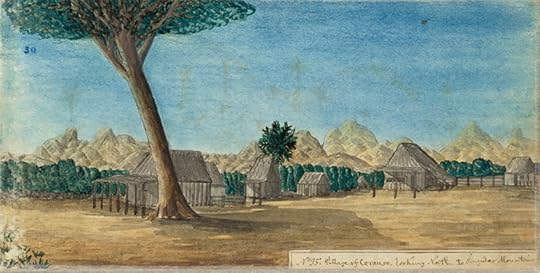

Antrim titled this sketch, “Village of Cerauso looking North to singular Mountain.” Manuscript Division.

Antrim titled this sketch, “Village of Cerauso looking North to singular Mountain.” Manuscript Division. The result was an illustrated travelogue, a kind of time capsule that captured relatively undeveloped parts of rural Mexico as he witnessed them in midcentury and many edifices that remain destinations for tourists and religious pilgrims today.

Antrim went on to make a living as a daguerreotypist in California and Hawaii before returning to the Eastern United States for the remainder of his life.

A finding aid to the Antrim journals and sketchbooks is available online with links to the digital content on the Library’s website. In February 2025, transcriptions created by volunteers were added to the digital presentation by the Library’s By the People crowdsourcing transcription program.

Reaching the west coast, Antrim sketched the ocean. “Our first view of the Pacific Ocean at Mazattan looking S West.” Manuscript Division.

Reaching the west coast, Antrim sketched the ocean. “Our first view of the Pacific Ocean at Mazattan looking S West.” Manuscript Division.Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

July 17, 2025

“Amazing Grace” Didn’t Stand out as “Amazing” When First Published

-This is a guest post by Sahar Kazmi, a public affairs specialist in the Office of the Chief Information Officer. It also appears in the July-August edition of the Library of Congress Magazine.

There’s a famous bit of country music lore that says Dolly Parton wrote two of her biggest hits, “Jolene” and “I Will Always Love You,” on the same night.

The story may not be perfectly true (Parton has said she might have written the songs a few days apart, though they were first recorded on the same cassette), but it’s stuck around in pop culture mythology for years. There’s something almost mystical about the idea that two such celebrated works could share a single point of origin. The stars don’t often align so perfectly. But rare is a Library specialty.

Centuries ago, in the village of Olney, England, the Rev. John Newton and poet William Cowper produced two iconic cultural artifacts for a single collection, the “Olney Hymns” of 1779.

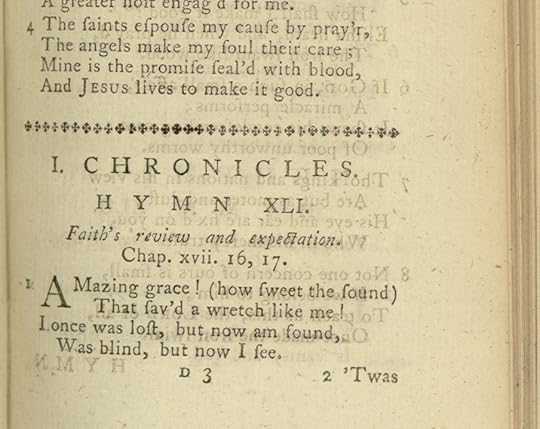

The hymnal’s best-known work, the beloved “Amazing Grace,” is one of the most-recorded songs in history. It didn’t particularly stand out at the time of publication, though — it’s not called “Amazing Grace,” just numbered “Hymn 41” and begins at the bottom of page 53 (in viewing the Library’s digital version, this is image 94). The hymnbook was huge, running to three volumes and more than 450 pages, containing 280 hymns by Newton and 68 by Cowper.

Newton wrote in the preface that the pieces should be simple, for the common folk, and not strain to the reach the heights of poetry. “They should be hymns, not odes, if designed for public worship and for the use of plain people,” he wrote. “Perspicuity, simplicity and ease, should be chiefly attended to; and the imagery and coloring of poetry, if admitted at all, should indulged very sparingly and with great judgment.”

In the book’s layout, “Grace” is the first entry in a group of songs listed under the biblical book of I Chronicles. Under “Hymn 41,” a subheading says that the hymn relates to Chapter 17, verses 16 and 17, and is about “Faith’s review and expectation.”

“Amazing Grace” was just called “Hymn XLI,” when first published in “Olney Hymns.” XLI is the Roman numeral for 41. Music Division.

“Amazing Grace” was just called “Hymn XLI,” when first published in “Olney Hymns.” XLI is the Roman numeral for 41. Music Division.Newton, once a self-described infidel and libertine, wrote it after a life of near-miss accidents — a horse-riding injury, a deadly storm at sea, a stroke — drew him to faith and ministry. In the hymn, modern readers will notice the elongated letter “s,” which looks like a modern “f,” but still be able to easily read the famous first lines:

Amazing Grace! (how sweet the sound)

That sav’d a wretch like me!

I once was lost, but now am found,

Was blind, but now I see.

His friend, Cowper, sought religion through his own trials. His hymn “Light Shining Out of Darkness” coined the well-known maxim, “God moves in mysterious ways.” Although he’d published multiple texts and earned acclaim, Cowper suffered from severe depression and made multiple attempts on his own life.

Cowper’s handwritten note in the first, blank pages of the Library’s copy of “Olney Hymns,” give the book a personal touch. It describes a coachman’s refusal to drive Cowper to the Thames River, in which he’d planned to drown himself.

Cowper’s handwritten note in the first pages of “Olney Hymns,” including his famous line at the end: “God moves in a mysterious way.” Music Division.

Cowper’s handwritten note in the first pages of “Olney Hymns,” including his famous line at the end: “God moves in a mysterious way.” Music Division.Cowper later referred to the incident with a version of the line that is today paraphrased to explain all kinds of uncertainty and distress: “God moves in a mysterious way, his wonders to perform.”

Maybe it was just chance that saved Cowper’s life that day. Or maybe there’s a bit of providence somewhere behind the enduring power of the “Olney Hymns.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

July 15, 2025

Hang Onto That Cliff! Kay Aldridge, “The Serial Queen”

Return with us to those thrilling days of yesteryear, when Saturday afternoon movie matinees had an action-packed serial just before the main feature, and none other than Kay Aldridge was The Serial Queen!

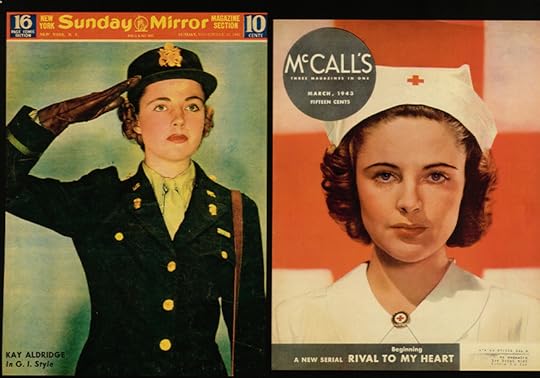

There she was in 1942, the cover girl and model, one of the “most photographed girls in the world,” kicking and clawing in “Perils of Nyoka”! And the next year in “Daredevils of the West,” horseback ridin’ and rifle shootin’!

“Millions of hysterically screaming kids in 11,000 U.S. movie theaters greet Republic’s cliff-hanging serials with cheers for the lady whose life hangs in the balance,” said one newspaper column at the peak of her fame. “Kay Aldridge, tall, willowy, with a placidly beautiful face …”

Aldridge, who died at age 77 in 1995 as a much-loved figure in Camden, Maine, the small coastal town where she had settled and went by her married name of Kay Tucker, may be mostly forgotten now. But the Library preserves a unique take of her life in “Memoirs of a Southern Belle,” a scrapbook/pictorial biography by her daughter, Carey Cameron Ferrero.

Six models from the Powers Agency in New York were selected to go to Hollywood to appear in “Vogues of 1938.” Kay Aldridge, second from the right, would go on to appear in 25 films, including three popular serials. Photo: Courtesy of Carey Cameron Ferrero.

Six models from the Powers Agency in New York were selected to go to Hollywood to appear in “Vogues of 1938.” Kay Aldridge, second from the right, would go on to appear in 25 films, including three popular serials. Photo: Courtesy of Carey Cameron Ferrero.Going through her mom’s house after the funeral, Ferrero writes that she found “several dusty cardboard boxes” of her mother’s “brief but splashy career as a model, cover girl and actress.” Inside were a jumble of magazine covers, movie stills, family photos, diaries, fan letters (many containing marriage proposals), newspaper clippings and the like.

Aldridge had never been shy about anything — an affectionate editorial in The Camden Herald after her death noted her “lack of bashfulness for the center stage” — but many of the images and anecdotes were new to her daughter. Many of them had been in scrapbooks that had fallen apart years ago, but were now scattered in no real order.

Ferrero realized that, if she assembled the material into a narrative, it would tell the story of her mother’s “9-year career and its lifelong consequences.”

“The images — some spectacular, others charming, others embarrassing, the majority of them emblematic of American popular culture before and during World War II — compelled me to want to examine the contents of every one of the boxes,” she wrote in the foreword.

The result is an engaging story of a young woman who made it from difficult childhood circumstances in rural Virginia (her father died when she was 5) to almost instant fame by the time she was 19. A relative arranged for her to walk into the fancy Powers Agency in New York and ask for a modeling job — and she was shooting an ad that afternoon to run in Vogue magazine.

Kay Aldridge on the cover of LIFE magazine, then one of the most popular in the country, in 1939. Photo: Courtesy of Carey Cameron Ferrero.

Kay Aldridge on the cover of LIFE magazine, then one of the most popular in the country, in 1939. Photo: Courtesy of Carey Cameron Ferrero.Many of the personal items in the scrapbook have a touching immediacy, like her diary entry of March 1, 1937, the day she signed her first movie contract. She was 19 years old and on her own in Hollywood: “I am thrilled and frightened,” she wrote. “I feel that the course of my life is changing. I am a scared little girl tonight.”

Success blew in — she was on at least 44 magazine covers and in 25 films in nine years. She hung out with stars like Jimmy Stewart and Henry Fonda and was featured on radio shows and in newspaper profiles. You’d see her on the cover of major national publications such as Life, Look, Redbook and Collier’s. She was the smiling girl in ads for Chrysler cars, Jergens skincare and any number of cigarettes — Camel, Chesterfield, Raleigh, Lucky Strike. You’d also see her in newspaper ads for long-forgotten products such as WILDROOT Hair Tonic and Dr. Lyon’s Tooth Powder.

But that quick success was also one of her Hollywood limitations, she told an interviewer years later. She was so young, so green, and scarcely had time for acting lessons before finding herself in small film roles. Since she was a star model, she didn’t take those little roles seriously and squandered opportunities, she said.

“I always wanted to do light romantic comedy,” she told Merrill T. McCord, author of the 1979 short biography, “Perils of Kay Aldridge: Life of the Serial Queen.” “I was always, I felt, miscast as this superior Eastern society type girl and haughty. Since I couldn’t act and it (the role) wasn’t natural to my personality, it was like casting me across the grain. … I think my career was handicapped by the overemphasis on how photogenic I was supposed to be.”

Dropped from her contract, she took the lesser role of starring in a serial, “Perils of Nyoka,” by Republic Pictures. The 12-chapter story, with one episode coming out each week to draw kids back to the cinema, was popular. It paid good money and was notable because featured as actress as the headliner. She committed to the bit, drawing headlines for doing many of her own action sequences and getting bruises in the process.

Aldridge was on the cover of at least 44 magazine in her 9-year career, with many during World War II. Photo: Courtesy of Carey Cameron Ferrero.

Aldridge was on the cover of at least 44 magazine in her 9-year career, with many during World War II. Photo: Courtesy of Carey Cameron Ferrero.The trailer for her next serial, “Daredevils of the West,” billed her as “The Serial Queen” and promised “12 EPISODES OF … PUNCH-PACKED, HAIR-RAISING, THRILL-CRAMMED ACTION!” (On screen, the exclamation point is an arrow, of the type that keeps getting shot at our heroine.)

Serials faded into the Hollywood sunset after the 1950s, though they would remain popular with film buffs and in the memories of children of the era. Filmmakers George Lucas and Steven Spielberg modeled their hugely popular “Star Wars” and “Indiana Jones” movies on the serials they loved as kids.

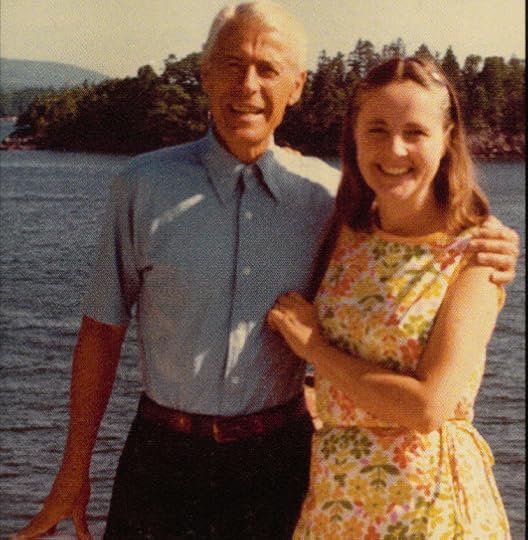

Aldridge married Richard Tucker, her second husband, in the 1950s. He had a second home in Camden, Maine. She remained there after his death in the late 1970s and became a fixture in town. Photo: Courtesy of Carey Cameron Ferrero.

Aldridge married Richard Tucker, her second husband, in the 1950s. He had a second home in Camden, Maine. She remained there after his death in the late 1970s and became a fixture in town. Photo: Courtesy of Carey Cameron Ferrero.After three serials, Aldridge married a wealthy man (she had been supporting most of her family, and this was apparently something of a career goal) and left Hollywood at 28. She never went back to acting.

Over the years, there were three marriages, kids and a happy second act as a much-admired hostess and life of the party in Camden, a little town on Penobscot Bay. She attended the occasional film festival, delighting fans, often as excited as they were.

“Camden will not be quite same without Kay Tucker,” wrote Bill Patten, publisher of The Camden Herald, in an op-ed on Jan. 19, 1995, shortly after her death. “… what an extraordinary asset she had become to this community … she had become a local institution.”

It’s always the good picture that has a happy ending.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

July 10, 2025

The Montgomerys of Mississippi: How a Once Enslaved Family Bought Jefferson Davis’ Plantation House After the Civil War

On the pleasant winter day of Jan. 17, 1872, Mary Virginia Montgomery, the precocious 21-year-old daughter of one of Mississippi’s largest cotton planters, used her diary to record the day’s activities on Brierfield, the family’s sprawling cotton plantation south of Vicksburg.

“Brierfield is so beautiful this morning,” she wrote in her careful penmanship. “… I spent fully two hours practicing [piano] after dinner. … After supper read Byron and some chemistry.”

Before the Civil War, Brierfield belonged to Jefferson Davis, who became president of the Confederacy, but it was now the Montgomery’s. The adjoining plantation, which her family also now owned, was named Hurricane and had belonged to Davis’ brother, Joseph. This was several thousand acres on a peninsula that formed a deep curve in the Mississippi River, called Davis Bend.

Brierwood, Jefferson Davis’ plantation home on Davis Bend, in 1862 during the Civil War. The Montgomery family lived here after purchasing it in 1866. Photo: George Holmes Bixby. Prints and Photographs Division.

Brierwood, Jefferson Davis’ plantation home on Davis Bend, in 1862 during the Civil War. The Montgomery family lived here after purchasing it in 1866. Photo: George Holmes Bixby. Prints and Photographs Division.The remarkable thing about Mary Virginia’s musings, considering the Deep South’s brutal reality, is that she was Black, a former slave on Davis Bend, and that in less than a decade she and her family had moved from being the property of Joseph Davis to being owners of his plantation and that of his famous brother.

Further, Isaiah Montgomery, one of her brothers, would go on to create and help run Mound Bayou, the all-Black Delta community that was a nationally known model of Black self-sufficiency in the early 20th century. President Theodore Roosevelt toured the town and dubbed it the “jewel of the Delta.” Booker T. Washington was a staunch supporter.

The Montgomery family story is one of the most unique tales to arise from the ashes of the Confederacy and attempts during Reconstruction to create a democratic society in its wake. They tread a delicate balancing act born of their unique circumstances — freedoms, living standards and educational levels that were unimaginable to nearly all other formerly enslaved people. In 1870, five years after the Civil War, Benjamin Montgomery’s estate was valued at an astonishing $50,000.

Two pages from Mary Virigina Montgomery’s 1872 diary. She put her initials at the end of each entry. Manuscript Division.

Two pages from Mary Virigina Montgomery’s 1872 diary. She put her initials at the end of each entry. Manuscript Division.Family records preserved at the Library (and many others at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History) show that Benjamin Montgomery, the family patriarch, was born into slavery in Virginia in 1819 and was sold at auction in 1836 to Joseph Davis, then a wealthy lawyer who had branched out into being one of the state’s largest cotton farmers. Davis was a firm believer in slavery — at one point he owned more than 200 slaves — but he had been influenced by British social reformer Robert Owen and educated and trained many of his enslaved workers.

Montgomery was his star protégé. He was an accomplished engineer and mechanic, he kept Davis’ books, ran the dry goods store on the plantation (keeping the profits) and often managed the place in Davis’ absence. He married Mary Lewis, another slave on the plantation, but effectively bought her out of slavery, for she worked only at their house and garden, taught her children and did not work for the Davis household.

When the Civil War broke out, Davis fled with most of his enslaved workers, leaving Montgomery to tend the place.

Gen. Ulysses Grant’s army swept in and confiscated the property en route to taking Vicksburg, and Montgomery took the advice of Union officials and moved his family north to Ohio for the remainder of the war. Isaiah stayed behind to join the Union Army until illness forced him out.

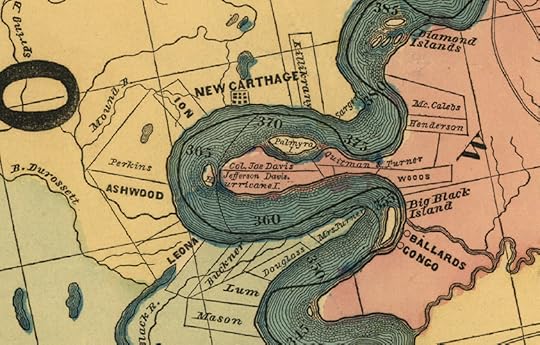

In this 1862 map, Davis Bend stuck out into the Mississippi River like a thumb. The land is denoted as belong to “Col. Joe Davis and Jefferson Davis.” The river has since changed course, making Davis Bend an island. Lloyd’s Maps. Geography and Map Division.

In this 1862 map, Davis Bend stuck out into the Mississippi River like a thumb. The land is denoted as belong to “Col. Joe Davis and Jefferson Davis.” The river has since changed course, making Davis Bend an island. Lloyd’s Maps. Geography and Map Division.After the war, the family returned as free people to Davis Bend. Montgomery both impressed and annoyed Reconstruction officials, who considered him to be Joseph Davis’ de facto agent, bent on disrupting their work.

When the military left, Davis won the right to reclaim Davis Bend. He sold it to Montgomery in 1866, for $300,000 plus interest, to be repaid in nine years.

The Montgomerys went to work, planting their own cotton, renaming the dry goods store “Montgomery & Sons,” managing a cotton gin and leasing plots to other freedmen in a bid to create an independent, all-Black enclave.

But the river changed course and flooded often (so much so that the peninsula would eventually be cut off into an island), insects ravaged crops, the Depression of 1873 wrecked the national economy and most freedmen wanted to own their own land, not lease it from anyone.

In the 1870s, Joseph Davis and Montgomery died, Jefferson Davis (now freed from prison) sued to claim what he still regarded his plantation. Banks eventually foreclosed on the mortgage and the Montgomerys left the place in 1880s.

But while Benjamin Montgomery had worked hard for Black independence, he almost entirely avoided politics, wrote historian Thavolia Glymph in her 1994 doctoral dissertation on Davis Bend. Blacks were the majority in Mississippi, about 60 percent of the population, and Black male suffrage was the overwhelming topic of the day. In the Reconstruction years of the late 1860s and 1870s, Montgomery was the third–largest cotton planter in the state. He might have competed for high office.

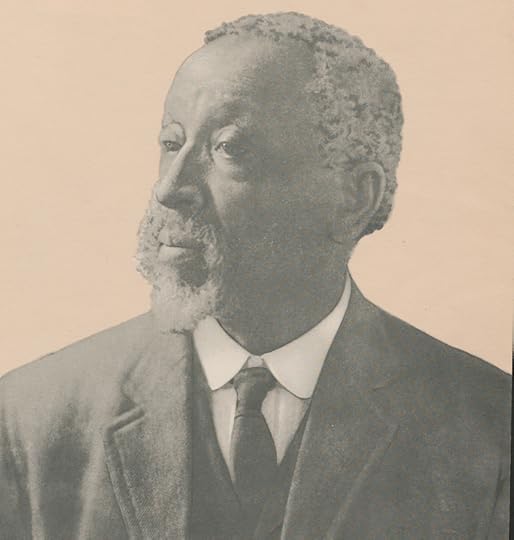

Isaiah Montgomery, who was born enslaved in Davis Bend and later founded Mound Bayou, the all-Black town in the Mississippi Delta. Photo: The Gerlach-Barklow Co. Manuscript Division.

Isaiah Montgomery, who was born enslaved in Davis Bend and later founded Mound Bayou, the all-Black town in the Mississippi Delta. Photo: The Gerlach-Barklow Co. Manuscript Division.Instead, father and son had maintained close ties to Joseph Davis and other “leading whites” as business connections and as protection from the Ku Klux Klan. By the time he was an adult, Isaiah Montgomery began to think that most Black men, often illiterate and just released from far harsher slavery than his family had endured, were not qualified to vote.

This stance made national news in 1890, when he was the lone Black delegate at a state constitutional convention openly dedicated to expelling Black men from politics. In a speech that was reprinted in many newspapers across the country, he told the crowd that most Black men should be kept from voting “because of their inferior development in the line of civilization.”

He offered an “olive branch” to whites, saying that most Blacks (and some whites) should be barred from voting until they could obtain more education. He asked that in exchange whites allow Blacks to live in peace separately.

Many whites hailed it as heroic; most Black leaders in the state and elsewhere were apoplectic. Frederick Douglass lambasted Montgomery as guilty of “treason, to the cause of colored people, not only to his own state but of the United States.”

Montgomery, undeterred, developed Mound Bayou with his cousins as a church-going, farming and entrepreneurial home of Blacks who built nice houses, quietly made decent money and were so law-abiding that the town of 4,000 or so had no jail or need for one. White politicians and the KKK left it alone, even while they viciously attacked Blacks elsewhere in the state.

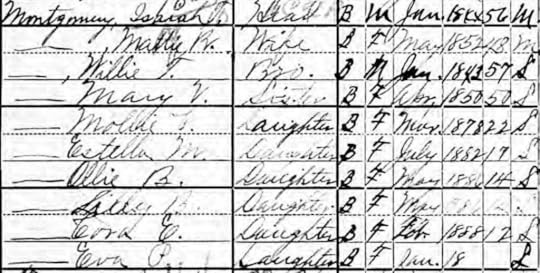

In the 1900 census, Isaiah Montgomery was living in Mound Bayou with his wife, Martha; Willie, his brother; and Mary Virginia, his sister’ as well his children.

In the 1900 census, Isaiah Montgomery was living in Mound Bayou with his wife, Martha; Willie, his brother; and Mary Virginia, his sister’ as well his children.Mound Bayou’s fortunes eventually faltered, but the family held onto a unusual version of history for decades.

In a 1937 celebration marking the town’s 50th anniversary, a brochure featured a full-page celebration of Jefferson Davis, claiming that was he was actually the “first white man” to help freed slaves “have a chance to become self-supporting and independent citizens” and had urged his brother to sell land to the Montgomerys. (Neither claim was true.)

It left a confounding legacy.

“To the end, (Isaiah) Montgomery seemed unable to recognize that whites had not lived up to the bargain he had struck with them in 1890,” wrote Glymph, now the Peabody family distinguished professor in history at Duke University. “In his public statements, he made no link between black disfranchisement and the powerlessness of blacks against white violence. He continued to believe that ‘leading whites’ would be able to separate the idlers of the race from the progressive, well-mannered ones at Mound Bayou.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

July 8, 2025

The National Book Festival’s 25th Edition!

The National Book Festival’s 25th edition returns to D.C. on September 6 with a stellar list of novelists, historians, poets, young-adult and childrens authors, more than 90 in all.

You’ll see novelists such as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Scott Turow and Jess Walter; non-fiction authors such as Ron Chernow, Jill Lepore and Geraldine Brooks; and Academy Award-winning actress Geena Davis with her picture book for children. Associate Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett will be on stage to discuss her book, “Listening to the Law: Reflections on the Court and Constitution.”

Founded by first lady Laura Bush in 2001, the National Book Festival has always sought to feature some of the most thoughtful American writers talking about their latest books and engaging with readers.

The festival has changed over the years, moving from a small festival on Library of Congress grounds and in its buildings on Capitol Hill, to a sprawling one on the National Mall to the air conditioned one (phew!) that occupies the Washington Convention Center.

Claiborne Smith, the Library’s literary director, summarizes the NBF as a unique distillation of what’s happening in American book culture each year. It’s always a good time — and a very busy day for book lovers.

If you can’t make it to D.C., no worries. Main Stage events will be livestreamed and C-SPAN’s Book TV will be interviewing authors and broadcasting some presentations. Videos of some presentations will be made available on the Library’s YouTube channel (and all will be on our website) a few days after the festival.

Meanwhile, here’s the complete list.

Fiction

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie – “Dream Count”

Kashana Cauley – “The Payback”

Susan Choi – “Flashlight”

Ron Currie – “The Savage, Noble Death of Babs Dionne”

Alison Espach – “The Wedding People”

Elizabeth Harris – “How to Sleep at Night”

Cristina Henríquez – “The Great Divide: A Historical Novel of the Panama Canal”

Katie Kitamura – “Audition”

Laila Lalami – “The Dream Hotel”

Liz Moore – “The God of the Woods”

Nnedi Okorafor – “Death of the Author”

Helen Phillips – “Hum”

V.E. Schwab – “Bury Our Bones in the Midnight Soil”

Maggie Su – “Blob: A Love Story”

Scott Turow – “Presumed Guilty”

Willy Vlautin – “The Horse”

Jess Walter – “So Far Gone”

Chris Whitaker – “All the Colors of the Dark”

Genre Fiction

Joe Abercrombie – “The Devils”

Agustina Bazterrica – “The Unworthy”

Shannon Chakraborty – “The Adventures of Amina al-Sirafi”

Alexis Daria – “Along Came Amor”

Fiona Davis – “The Stolen Queen”

Stephen Graham Jones – “The Buffalo Hunter Hunter”

Tochi Onyebuchi – “Harmattan Season”

Kennedy Ryan – “Can’t Get Enough”

Biography, History and Memoir

Rick Atkinson – “The Fate of the Day: The War for America, Fort Ticonderoga to Charleston, 1777-1780”

Geraldine Brooks – “Memorial Days: A Memoir”

Ron Chernow – “Mark Twain”

Paul Elie – “The Last Supper: Art, Faith, Sex and Controversy in the 1980s”

Garrett M. Graff – “The Devil Reached Toward the Sky: An Oral History of the Making and Unleashing of the Atomic Bomb”

Jill Lepore – “We the People: A History of the U.S. Constitution”

Yuval Levin – “American Covenant: How the Constitution Unified Our Nation – And Could Again”

Clay Risen – “Red Scare: Blacklists, McCarthyism and the Making of Modern America”

General Nonfiction

David Baron – “The Martians: The True Story of an Alien Craze That Captured Turn-of-the-Century America”

Justice Amy Coney Barrett – “Listening to the Law: Reflections on the Court and Constitution”

Elias Weiss Friedman – “This Dog Will Change Your Life”

Brian Goldstone – “There Is No Place for Us: Working and Homeless in America”

John Green – “Everything Is Tuberculosis: The History and Persistence of Our Deadliest Infection”

Alexandra Horowitz – “Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell and Know”

Honorée Fanonne Jeffers – “Misbehaving at the Crossroads: Essays & Writings”

Ian Kumekawa – “Empty Vessel: The Story of the Global Economy in One Barge”

Peter Kuper – “Insectopolis: A Natural History” and “Coloring Insectopolis”

Kate Marvel – “Human Nature: Nine Ways to Feel About Our Changing Planet”

Patrick McGee – “Apple in China: The Capture of the World’s Greatest Company”

Imani Perry – “Black in Blues: How a Color Tells the Story of My People”

Mark Rowlands – “The Word of Dog: What Our Canine Companions Can Teach Us About Living a Good Life”

Jenny Slate – “Lifeform”

Leah Sottile – “Blazing Eye Sees All: Love Has Won, False Prophets and the Fever Dream of the American New Age”

Gianna Toboni – “The Volunteer: The Failure of the Death Penalty in America and One Inmate’s Quest to Die with Dignity”

Alan Weisman – “Hope Dies Last: Visionary People Across the World, Fighting to Find Us a Future”

Poetry and Translation

Academy of American Poets Laureate Fellows

Joy Harjo – “Washing My Mother’s Body: A Ceremony for Grief”

Ada Limón – “Startlement: New and Selected Poems”

Daniel Mendelsohn – “The Odyssey”

Tracy K. Smith – “To Free the Captives: A Plea for the American Soul”

Young Adult

Kelly Andrew – “I Am Made of Death”

Susan Dennard – “The Executioners Three”

Tracy Deonn – “Oathbound”

Channelle Desamours – “Needy Little Things”

Erin Entrada Kelly and Kwame Mbalia – “On Again, Awkward Again”

Tahereh Mafi – “Watch Me”

Maika Moulite and Maritza Moulite – “The Summer I Ate the Rich”

Caroline O’Donoghue – “Skipshock”

Marisha Pessl – “Darkly”

Ransom Riggs – “Sunderworld, Vol. I: The Extraordinary Disappointments of Leopold Berry”

Elle Gonzalez Rose – “The Girl You Know”

Mariko Tamaki – “This Place Kills Me”

Middle Grade

Kwame Alexander and Jerry Craft – “J vs. K”

Katherine Applegate – “Pocket Bear”

Andrea Beatriz Arango – “It’s All or Nothing, Vale”

Mac Barnett – “The First Cat in Space and the Wrath of the Paperclip”

Jorge Cham – “Oliver’s Great Big Universe: Volcanoes Are Hot!”

Gale Galligan – “Fresh Start”

Tiffany D. Jackson – “Blood in the Water”

Leah Johnson – “Bree Boyd Is a Legend”

Kate Messner – “The Trouble with Heroes”

Chris Raschka – “Peachaloo in Bloom”

Raúl the Third – “The Snips: A Bad Buzz Day”

Eleanor Spicer Rice – “The Deadliest: Spider”

R.L. Stine – “Stinetinglers 4: 3 Chilling Tales by the Master of Scary Stories” and “The Last Sleepover”

J.E. Thomas – “The AI Incident”

Paul Tremblay – “Another”

Renée Watson – “All the Blues in the Sky”

Picture Books

Leigh Bardugo and John Picacio – “The Invisible Parade”

Geena Davis – “The Girl Who Was Too Big for the Page”

Devin Elle Kurtz – “The Bakery Dragon”

Kiese Laymon – “City Summer, Country Summer”

Debbie Levy – “The Friendship Train: A True Story of Helping and Healing After World War II”

Christy Mandin – “Millie Fleur Saves the Night”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

June 27, 2025

Bill Moyers: A Lifetime Preserved at the Library of Congress

Bill Moyers, who died yesterday at the age of 91, was at the Library’s Coolidge Auditorium one night in the fall of 2023 to mark the preservation of more than 1,000 of his public television programs in The American Archive of Public Broadcasting, a collaboration between the Library and the Boston public media producer GBH.

His relationship with the Library went back to the summer of 1954, he told the packed auditorium, when he was a 19-year-old from a little town in Texas, in D.C. for a summer internship with U.S. Senator Lyndon Baines Johnson.

On his first day, Johnson’s top aide took him to the Library’s Congressional Research Service as the place to do his background work for Johnson’s policies and work on Capitol Hill.

“I came over and I was shown what they do, it’s incredible,” Moyers told the crowd, 69 years later. “All summer, I was much smarter than anyone knew I was because it was coming from the Congressional Research [Service] … I’ve been a fan of the research office and the process here and the Library all my life.”

The night was a crowning moment to one of the most influential careers in American media. The AAPB Bill Moyers collection preserves more than 50 years of his work, an invaluable look at American history as it was happening.

The collection “will allow viewers for generations to come to see what mattered to us over the years,” he told the Library, “and how we covered our times through the stories of contemporary democracy and its struggle to survive and thrive as well as the perceptions of many of our society’s foremost thinkers and creators.”

Moyers, born during the Depression in Hugo, Oklahoma, became an ordained Baptist minister and picked up a journalism degree from the University of Texas after his internship with Johnson. He worked for the Peace Corps and then returned to work for Johnson after he became president, eventually serving as his press secretary from 1965 to 1967.

He turned to television journalism a few years later, first with public broadcasting. His interview-based shows were driven by his genial, intelligent demeanor and persistent questioning of newsmakers. “The Bill Moyers Journal” debuted in 1972. His work as a news analyst with CBS began nearly a decade later, and in 1986 he formed a production company, Public Affairs Television, for a long-running series of programs that pursued, as one series was titled, “A World of Ideas.”

Working with his wife and creative partner, Judith Davidson Moyers, some of his most famous programs included “Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth,” “Genesis: A Living Conversation” and “Moyers on America.” The signature component of his career found its stride in these thought-provoking, long-form interviews. He had significant talks with, among many others, Chinua Achebe, Margaret Atwood, Toni Morrison, Elie Wiesel, Bill Gates, Salman Rushdie, Barbara Tuchman, Carlos Fuentes, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, five U.S. Supreme Court justices and four U.S. presidents. He wrote bestselling books that stemmed from those interviews. This work led to more than 35 Emmy awards amid a slew of other honors and hall-of-fame inductions.

That 2023 night in the Coolidge Auditorium, Moyers was in conversation with veteran journalist Judy Woodruff, who often worked for PBS and also was serving as chair of the executive advisory council of the AAPB.

At one point in the hourlong event, she asked him about his turn from the White House to public television. He worked as publisher of Newsday for a few years after leaving politics, then wrote a magazine story and book called “Listening to America” that had him travel across the country. It was a bestseller and a PBS producer in New York who read the piece happened to see him on the street. The man told him, “Moyers, you’re a good listener. I’ve got a job for you.”

That was an interview show on public television.

“I spent the next three years listening to America,” he said. “All levels, all kinds, Black, white, everything….and that just opened my pores. Stories flowed into me from other people and from what I read and from what I saw. And I just decided I’d spend my life asking questions.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

June 26, 2025

That Haunting Song from the “Severance” Finale? It’s an Oscar Winner…From the 1960s.

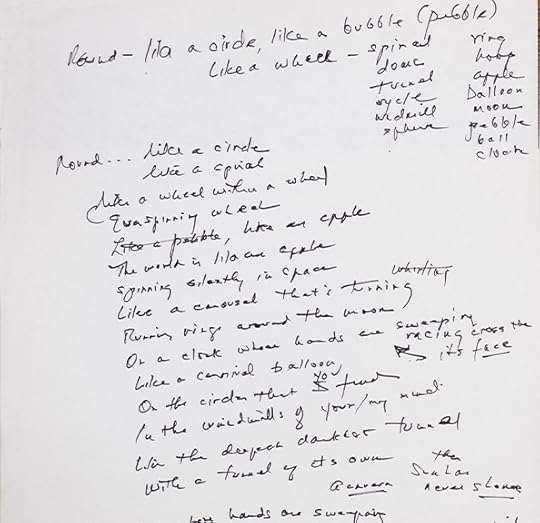

We’re working on lyrics here, something for a pop song with a stream-of-consciousness approach. These lyrics are going to be sung over a baroque, hypnotic melody. The song is about a wealthy thief with a cool exterior that hides the swirling, dreamlike thoughts he can conceal but not contain.

First ideas?

Maybe something like, “Round – like a circle, like a bubble (pebble)…”?

Hmm. Maybe “like a wheel” would be better? Or like a spiral, dome, tunnel, cycle, windmill or sphere? Or ring, hoop, apple, balloon, moon, pebble (again!), ball or clock?

Get it wrong and this piece, destined for a movie soundtrack, might sink into the category of forgotten flops and tank the flick besides. Get it right and who knows? Might be a classic, an Oscar winner, the kind of thing that could headline a Steve McQueen movie in 1968, be covered more than 300 times and show up again this spring, 57 years later, in the finale of “Severance,” the Apple TV+ hit series.

Songwriters Alan and Marilyn Bergman famously got it right – the song, “The Windmills of Your Mind,” won the Academy Award for Best Original Song from the McQueen film, “The Thomas Crown Affair.”

One of the working lyrics sheets for “The Windmills of Your Mind.” Music Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

One of the working lyrics sheets for “The Windmills of Your Mind.” Music Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.Over the rippling orchestration by Michel Legrand, they opened with:

Round … like a circle in a spiral, like a wheel within a wheel

Never ending or beginning on an ever-spinning reel

Like a snowball down a mountain or a carnival balloon

Like a carousel that’s turning, running rings around the moon

Like a clock whose hands are sweeping past the minutes of its face

And the world is like an apple whirling silently in space

A working lyrics sheet to “Windmill” and other Bergman songs are preserved in the Library’s Music Division, showing the progression of the song from sketch to finished product. It’s a speck in a snowstorm of a staggering career – the husband-and-wife duo were among the most successful lyricists in Hollywood history, winning three Oscars and being nominated another 16 times. (They also won four Emmys, two Grammys, were inducted into Songwriters Hall of Fame, as well as winning just about every other songwriting honor out there.)

They won a second Oscar for “The Way We Were” (along with composer Marvin Hamlisch), the title song for the 1973 Barbra Streisand/Robert Redford romantic drama, and a third for the score of “Yentl,” another Streisand film. They were Oscar finalists for six consecutive years in the late ’60s and early ’70s. In 1982, they had three of the five finalists for best original song but lost out to “Up Where We Belong” from “An Officer and a Gentleman.”

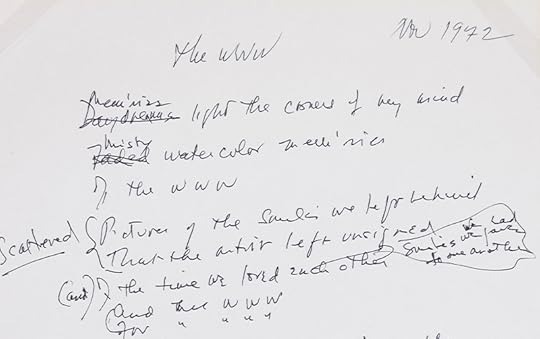

A working lyrics sheet, dated November 1972, for “The Way We Were.” Music Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

A working lyrics sheet, dated November 1972, for “The Way We Were.” Music Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.Television? They wrote the theme songs for ‘70s and ’80s staples such as “Maude” with music by Dave Grusin and sung by Donny Hathaway (“That uncompromisin’, enterprisin’, anything but tranquilizin’ Right on Maude!”); the upbeat “Good Times” (“Ain’t we lucky we got ’em?”); plus “Alice” and “In the Heat of the Night.”

The Bergmans, both native New Yorkers, later took leadership positions in the entertainment ndustry. Marilyn served as president of the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers for 15 years. In 2002, she was appointed to chair the Library’s inaugural panel of the National Recording Preservation Board. Alan also later served on the Library’s National Film Preservation Board. Marilyn died in 2022; Alan is 99.

Alan performed both of their Oscar winning songs at the Library’s ASCAP Collection Concert in 2010.

For “Windmills,” he told the crowd that “Crown” director Norman Jewison showed them a rough cut of McQueen’s character, a millionaire art thief, piloting a yellow hang glider, coolly aloof, while beset with nerves about an upcoming heist. Write me something for that, he said.

Legrand was staying with them at the time, Bergman said, and played the couple eight possible melodies for the scene; they all picked the same one. That settled, the lyrics tumbled out, a series of images that might flash through your mind while falling into a restless sleep. The cascade of images made it complicated but the rhyming structure was as simple as it gets: AA/BB/CC. They worked in most of their word choices from their list at the top of the lyric sheet and made a lost love affair the central focus:

Keys that jingle in your pocket, words that jangle in your head

Why did summer go so quickly, was it something that you said?

Lovers walk along the shore and leave their footprints in the sand

Is the sound of distant drumming just the fingers of your hand?

When they were finished, they had what would become a modern standard, recorded by hundreds of artists the world over in the coming decades. Still, it was a hard thing to name.

“We didn’t know what to call it,” Bergman told the ASCAP crowd, but there was “one phrase in there that was attractive to us and we decided to call it ‘The Windmills of Your Mind.’ ”

They got that one right, too.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

June 23, 2025

True Crime: William Kennoch, The Ace Counterfeit Detective

-Research by Micah Messenheimer in the Prints and Photographs Division and Jake Bozza, formerly of the Manuscript Division, contributed to this report.

It turns out that William “Bill” Kennoch, one of the nation’s top counterfeit detectives in the chaotic post-Civil War era, didn’t have any nifty nicknames, such as “Dollar” or “Wild.”

He was a rather somber native New Yorker who spent most of the Civil War in what is now the Coast Guard, then got busted on a Havana steamer in 1870 with contraband Cuban cigars. The arresting agent spotted something in the 29-year-old, though. Instead of charging him with a crime, he offered Kennoch a badge and a career with the U.S. Secret Service, the agency created in 1865 to combat counterfeit enforcement.

Kennoch took to the gig with gusto. He traveled undercover, used aliases, staked out sleazy houses, hung out in bars. Tools of his trade included a long thin knife in a leather sleeve (some of his suspects were violent) and a brass loupe to inspect bills.

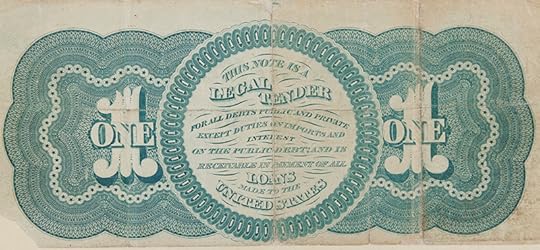

That’s why they called them greenbacks — the back of an 1865 one dollar bill. Photo: Shawn Miller. Manuscript Division.

That’s why they called them greenbacks — the back of an 1865 one dollar bill. Photo: Shawn Miller. Manuscript Division.“I’ve just arrived at this place and have just got on the scent of my man,” he wrote his wife, Dora, on Aug. 9, 1871, from Tyrone, Pennsylvania, a small town about 100 miles east of Pittsburgh. “I have only got a description of him from five years ago when he shot Marshal Butter and Van Vleet. He is somewhere within a 2.5 mile radius of this place in a perfect wilderness.”

His territory also ranged to upstate New York. He once wrote Dora that he was “going north toward the Canadian border between Vermont-New Hampshire … keep this note secret and do not tell anyone where I am.” He was mentioning his location, he wrote, so that in case anything should happen to him, she would know where to start looking. He tartly added: “It is very cold here – it would freeze a brass monkey’s bollocks.” .

Kennoch’s papers – diaries, letters, work reports, photographs of more than 1,200 criminals – are preserved at the Library. His adventures and office drudgery are well documented. He filed daily reports, including what time he got to work at his New York office, where he went, who he met with and for how long, what he spent and what time he went home. More expansive are his personal diaries and those letters to Dora. (He begins them all, “Dear wife.…”)

He was good at it, too. Hiram Whitley, the head of the Secret Service for the first years of Kennoch’s career, described him as “one of my ablest agents.” A newspaper described him as “better acquainted with counterfeiters, their ways and haunts than any other detective in the country.”

His work also gives a personal window into a tumultuous period of American history, when the country was trying to right itself from the disaster of the Civil War. Amid the ugly battles over Reconstruction, there was the cornerstone issue of rebuilding the economy.

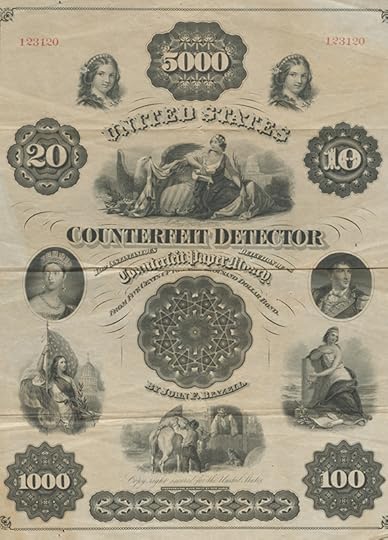

A flyer alerting consumers how to “Instantaneously Detect Counterfeit Paper Money” in the the late 1800s. Manuscript Division.

A flyer alerting consumers how to “Instantaneously Detect Counterfeit Paper Money” in the the late 1800s. Manuscript Division.This was complicated in some very fundamental ways. The nation never had a single national currency but after the Civil War broke out, the government started issuing millions of dollars in various notes and designs of paper currency, nicknamed greenbacks for the distinctive shade to the back of the bill, to cover its wartime expenses.

These were not backed by gold reserves. It wasn’t clear how or if they should be used after the war. There were also gold and silver coins in circulation. The currency situation was so profound that the Greenback Party, which favored the national bills’ continued use, won a number of state and congressional elections during the 1870s.

Further, the Panic of 1873 turned markets upside down, closed the stock market for more than a week and then settled into a yearslong downturn. It known as the Great Depression until the 1930s came along.

It was in this chaotic and often violent maelstrom that Kennoch and fellow agents fanned out across the country to track down legions of counterfeiters – the Secret Service estimated that one in every three bills in circulation was fake.

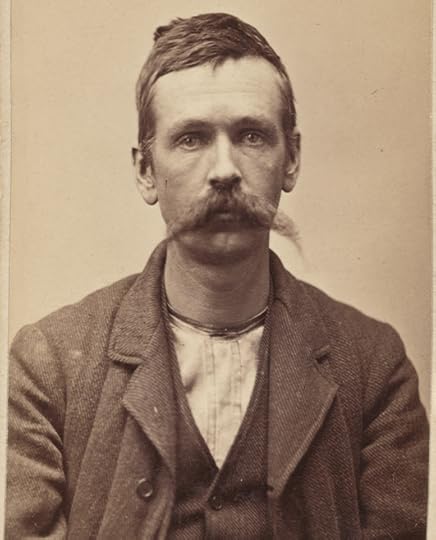

Dudley Vaught was arrested for counterfeiting in Milledgeville, Kentucky, on Feb. 12, 1884, and sentenced to five years in prison at hard labor. Prints and Photographs Division.

Dudley Vaught was arrested for counterfeiting in Milledgeville, Kentucky, on Feb. 12, 1884, and sentenced to five years in prison at hard labor. Prints and Photographs Division.Dudley Vaught, he of desultory expression, worn clothes and a magnificent handlebar moustache, was out on bail for homicide when he was arrested as one of the “Lincoln County counterfeiters” in Milledgeville, Kentucky, on Feb. 12, 1884. He was sentenced to five years at hard labor for the counterfeiting, with the homicide trial still to come.

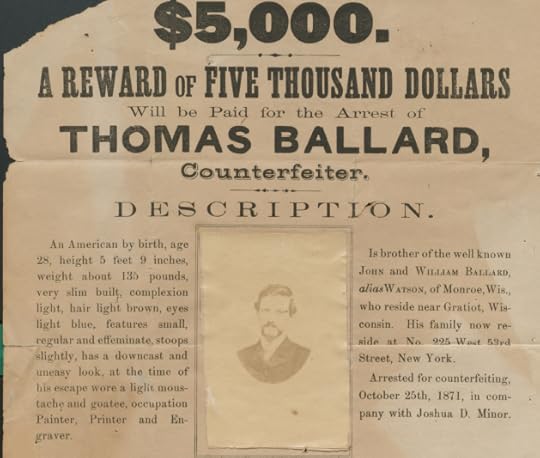

In 1871 New York,the Secret Service offered a whopping $5,000 reward for arrest of counterfeiter Thomas Ballard after he escaped from a local jail. The wanted poster describes him as blue-eyed, brown-haired man standing 5 feet, 9 inches tall, with features “small, regular and effeminate, stoops slightly, has a downcast and uneasy look.”

Counterfeiting was a serious crime, as this Wanted poster from the U.S. Secret Service lists a huge $5,000 reward for Thomas Ballard, a counterfeiter who had escaped from a New York jail in 1871. Manuscript Division.

Counterfeiting was a serious crime, as this Wanted poster from the U.S. Secret Service lists a huge $5,000 reward for Thomas Ballard, a counterfeiter who had escaped from a New York jail in 1871. Manuscript Division.Kennoch excelled at his work but as the years passed, he and Dora had two children. Finances were tight. An enterprising sort, he went into business with a patented burglar alarm of his own creation, but the venture didn’t get off the ground.

By the winter of 1880, nine years after excitedly getting on the scent of a suspect hiding in a “perfect wilderness,” he was still out in the field, slogging 12 miles on foot through the snow in rural Pennsylvania to meet five suspected counterfeiters. Taking a horse and sleigh, he wrote home to Dora, would have tipped them off that he had too much money on him.

If all this undercover work once had been an adventure, that day had passed. He was pushing 40, financially strapped, missing his family and tired of it all.

“I cannot make the same amount of money that I am now making if I remained at home,” he wrote to Dora, “and as we must live what else am I to do but stick it out…If I could do so I would leave this business tomorrow.”

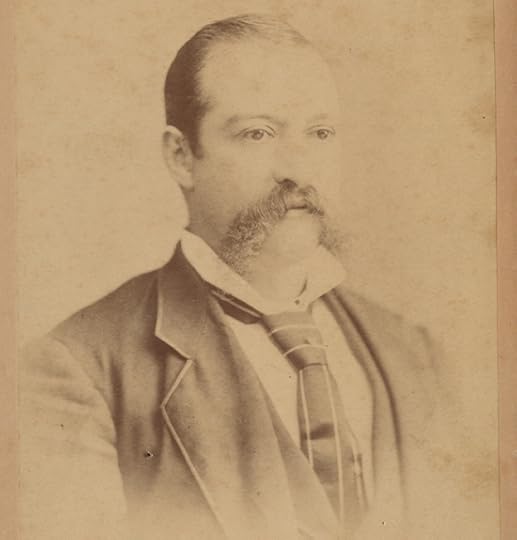

WIlliam Kennoch, later in life, in an undated portrait. Photo: Unknown. Manuscript Division.

WIlliam Kennoch, later in life, in an undated portrait. Photo: Unknown. Manuscript Division.He never did, though.

Seven years later, still working for the Secret Service, Bill Kennoch endured months of ill health before dying of heart disease. He was 46.

Dora was so destitute that Congress approved a special pension for her, citing a long-ago foot injury to Kennoch during his Civil War service. It was $12 per month, and she and the children carried on. The nation’s currency changed and settled and massive counterfeiting waned. Kennoch’s name, and his time as a lawman on the nation’s financial frontier, passed into a drama that would be preserved in the Library’s collections.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

June 18, 2025

Angela Napili’s “Charmed Life” at the Congressional Research Service

Angela Napili is a senior research librarian in the Congressional Research Service.

Tell us about your background.

I’ve lived a charmed life. Our family left the Philippines after Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law, and I grew up in beautiful San Francisco. Every week, our parents took us to the main children’s reading room of the public library. Libraries have felt like home ever since. I earned bachelor’s degrees in philosophy and math from Stanford, where my student job was assisting the cataloging team of the university’s Green Library. The librarians were some of the nicest and most interesting folks on campus. Then, I earned master’s degrees in philosophy and library and information services at the University of Michigan. There, I worked the late shifts at the reference desks of the graduate and undergraduate libraries. Helping students the night before their term papers were due was good practice for the short deadlines of the Congressional Research Service.

What brought you to the Library, and what do you do?

As a grad student, I did a summer internship at CRS, attracted by the lofty mission. An informed legislature is crucial for democracy! Then, I was hired through CRS’ Graduate Recruit Program. Almost 25 years later, I still feel privileged to work here every day. The vast majority of my time is spent either answering congressional research requests directly or doing research for CRS policy analysts and attorneys to help them prepare briefings, memos and other work for Congress. Sometimes, that means hunting down elusive statistics. Sometimes it means doing literature searches or compiling relevant excerpts from academic studies or reports of advisory commissions, government agencies or think tanks. Sometimes, to describe a statutory provision’s history, we search committee reports, floor debates, scholarly literature and contemporaneous press accounts for clues about why a provision was enacted. Sometimes, we check federal program eligibility rules in case they might apply to a constituent’s situation. In other words, Congress gives us a huge variety of work. It’s a super fun job if you’re curious and enjoy intellectual challenges. My colleagues are kind, indefatigable and brilliant. Like I said, a charmed life.

What are some of your standout projects?

Because confidentiality is a core CRS value, some of our most impactful achievements are things we can’t talk about. However, Congress.gov publicly posts some CRS reports written for general congressional audiences. Our Medicaid team updated our Medicaid overview, and my colleague Sarah Braun and I wrote a new guide to Medicaid enrollment data sources to help Congress learn about the beneficiaries in their states and districts. CRS has a series of “Connecting Constituents” reports to help Congress connect constituents to resources and benefits. I helped write reports about health information and services and on longterm services and support for older adults. When my dad started having health issues, I gained firsthand experience with some of the resources I’d written about, such as the State Health Insurance Assistance Program’s free Medicare consultations and the Aging and Disability Resource Center’s free options counseling. They helped our family navigate a complicated health care system. A particularly meaningful Library experience was volunteering with my colleague Pam Hairston to do “Man-on-the-Mall” Veterans History Project interviews at the 2004 World War II Memorial dedication. We interviewed one of the first soldiers to land at Omaha Beach on D-Day, a prisoner-of-war survivor of the Bataan death march, two survivors of Pearl Harbor and a nurse who treated concentration camp survivors. I will never forget their stories.

What do you enjoy doing outside of work?

I’m a volunteer photographer for Indy Honor Flight, which flies older and terminally ill veterans to D.C. to visit memorials. I’m also a volunteer photographer for the National Mall and the Library’s costume balls and family days. The DC Public Library recently acquired eight of my National Mall and animal photos for its Exposed DC Photography Collection. My most famous snapshots, though, are those that won the Washington Post’s squirrel photography contest! These days, my favorite photo subjects are the National Zoo’s goofy pandas and my handsome cat, Captain Georg von Trapp (“Georgie”).

What is something your coworkers may not know about you?

I’m a longtime National Park Service volunteer. If you see me at the Washington Monument, where I volunteer most Sundays, ask me about “The Pope’s Stone.” The story is bananas!

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

June 13, 2025

Indigenous History Kept Alive at the Library

This story also appears in the May-June issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Last summer, two men from Fulton Township, Michigan, walked onto the mosaic floor of Jefferson Building’s Great Hall. There, dressed in regalia of the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi, brothers Devonne Harris and Kevin Harris II began to dance. A videographer recorded their performance for a project documenting their culture and heritage.

“I felt proud,” said Kevin Harris II. “I felt brave. I felt love, humility, pride and motivation.”

The Huron Band is one of 30 awardees to receive a Community Collections Grant between 2022 and 2024. Funded by the Mellon Foundation and administered by the American Folklife Center at the Library, the yearlong grants are helping communities preserve unique cultural practices for future generations.

The band’s project, funded in 2024, combines oral history interviews with videography, an approach JW Newson, the project’s executive director, describes as “ethnographic research shot in a documentary style.”

Devonne Harris and Kevin Harris II dance in the Library’s Great Hall. Photo: Johnathon Moulds.

Devonne Harris and Kevin Harris II dance in the Library’s Great Hall. Photo: Johnathon Moulds.The Harrises and four other members of the Huron Band visited the Library last summer after learning about a rare Potawatomi-language sound recording preserved in AFC’s collections. Two young girls, thought to be residents of an Indian boarding school, sing on the recording, made in Lawrence, Kansas, by Willard Rhodes. Between 1939 and 1952, the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Library sponsored his ethnographic field expeditions to Native American communities.

“To know that those little kids, whatever they were going through in the boarding-school era, were still actively doing traditional things .… It’s just a feeling of resiliency,” said Onyleen Zapata, the band’s historic preservation officer. Over the past three years, folklife specialists in AFC have offered training and technical support to grantees. The center is also archiving materials communities create and sharing completed projects on the Library’s website.

But communities themselves are carrying out the projects.

“Self-representation is a huge part of it,” said John Fenn, AFC’s research head. “We want to empower communities to self-represent in the archive through creating their own cultural documentation.”

AFC will soon release records from a project funded in 2022 and led by Tammy Greer, a member and scholar of the United Houma Nation.

Through oral history interviews, photos and video and audio recordings, she and her team documented tribal traditional arts, including basketmaking, wood carving, weaving and doll making.

“We are well aware that some of our traditional art ways are in jeopardy of going to sleep,” Greer said.

She is now transcribing interviews from the local idiom, which is influenced by Cajun. She is also providing metadata so that language describing the collection in Library records originates with the community itself.

“It’s painstaking work,” said Guha Shankar of the AFC, “but well worth it.”

“I always teach fieldworkers they are the first archivists,” he said. “They’re the eyes and ears. We would never get all of the nuances that define local customs and cultural expressions if not for the community supplying that metadata.”

Boots Lupenui, another 2022 grantee, documented historical songs of the Kohala region of Hawaii. A native Hawaiian, he interviewed composers or their descendants to uncover stories behind the songs and then recorded several of them.

Boots Lupenui performs traditional Hawaiian music with the Kohala Mountain Boys at the Library on April 10. Photo: Shawn Miller

Boots Lupenui performs traditional Hawaiian music with the Kohala Mountain Boys at the Library on April 10. Photo: Shawn Miller“We are trying to preserve these heirloom songs, these snapshots of our history, culture and way of life before the last remaining memories of them disappear forever,” Lupenui said.

He performed in the Library’s storied Coolidge Auditorium in April to celebrate the launch of his collection online.

Other Community Collections Grants are documenting artistic creations of the Comanche Nation of Oklahoma; stories of Baltimore Lumbee elders; and traditional methods used by the Nuwä community of California to prepare plants for food and medicine.

All of the projects grow out of AFC’s decades-long tradition of collaborating — with Native communities, agencies such as the Smithsonian Institution and groups like the National Breath of Life Archival Institute for Indigenous Languages — to preserve and maintain Native cultural and language traditions.

This work began with the Federal Cylinder Project of the 1970s and 1980s in which AFC transferred thousands of turn-of-the-20th-century field recordings of Native American communities to reel-to-reel and cassette tape, then shared the tapes with communities.

More recently, AFC has worked with partners to make numerous digitized holdings — 1960s recordings of Zuni tribal elders, for example, and photos and recordings from the Rhodes collection — available to communities to support revitalization of ancestral languages and cultural practices.

“Doing this work is a process of continuous improvement,” AFC director Nicole Saylor said. “I am grateful for our collaborations with communities to ensure their voices and perspectives are reflected in the collections we steward.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers