Library of Congress's Blog, page 7

February 19, 2025

Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, Live at the Library

At times laughing and tossing back her long sisterlocks, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson engaged in a lively discussion with U.S. District Court Judge Carlton W. Reeves in the Coolidge Auditorium last week.

The packed event offered a window into the dynamic legal career of the first African American woman appointed to the Supreme Court in its history — her competitive drive, experiences in an interracial marriage and passionate dedication to helping aspiring law students.

As the featured guest of the 2025 Supreme Court Fellows Program Annual Lecture, Jackson held the audience with poignant and often humorous stories about her upbringing, the mentors who guided her and the “angels” who helped shape her unlikely journey to the nation’s highest court.

“The takeaway from my story is that anything is possible. If you believe in your ability to succeed and you put in the work … nothing worth having comes easy,” Jackson said. “I’m hoping that I’m inspiring people because if I can do it, really, anyone can.”

Her message of grit and grace, perseverance and the breaking of barriers is at the heart of her memoir, “Lovely One.” The title is inspired by her given name, Ketanji Onyika, which has roots in West Africa and her family translates as “lovely one.”

As Reeves noted, the book is a love story about the people who shaped her life.

Her parents wanted her to grow up with pride “in a society that, at least for them, had been closed off and unwelcoming to African Americans,” she shared.

Spanning nearly 400 pages, the book intertwines her personal and professional trek with the broader history of African Americans and civil rights.

She writes of her grandparents, who attended only grade school, and her parents, who grew up in the segregated South of the 1950s and 1960s. They earned degrees from historically Black colleges, and her father went on to law school, ultimately inspiring Jackson to follow in his footsteps.

A prolific writer and seasoned public speaker, Jackson said she felt compelled to write her memoir after enduring an “arduous” Senate confirmation process in 2022 and facing rising national curiosity about her journey.

“My success was not mine alone; there were so many people that had contributed, who had invested in me, and I wanted to pay tribute to them,” said Jackson, nominated by President Joe Biden to succeed Justice Stephen G. Breyer, for whom she had clerked in the 1999–2000 term.

She credited many mentors and role models along her journey, including her “flamboyant” and “larger-than-life” high school debate coach, Fran Berger.

She applied to Harvard University for college, recounting how she told the admissions committee: “I need to go to Harvard because it will help me fulfill my dream of being the first African American Supreme Court Justice to appear on a Broadway stage.”

(Last December, she checked off that box, stepping onto the stage at Broadway’s Stephen Sondheim Theatre for a walk-on role in the musical “& Juliet.”)

Once at Harvard, she excelled in debate, winning many tournaments. And she wasn’t kidding about her interest in theater. She told of once partnering in drama class with future Academy Award-winner Matt Damon, outshining him in their performance of a scene from “Waiting for Godot,” despite his community theater experience.

“When it was over, the professor said, ‘Ketanji, you were very good. Matt, we’ll talk,’” she said with a smile. “I remember thinking, ‘I was better than Matt Damon.’ ”

She earned both her undergraduate and law degrees with honors from Harvard, then moved to the professional world.

She interned with a public defender program in Harlem, clerked for three federal judges and served as both a staff attorney and vice chair of the U.S. Sentencing Commission.

She then worked at various corporate law firms, where she was often the only Black lawyer in the room — and overlooked or mistaken for a secretary.

Jackson and U.S. District Court Judge Carlton Reeves in conversation in the Coolidge Auditorium. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Jackson and U.S. District Court Judge Carlton Reeves in conversation in the Coolidge Auditorium. Photo: Shawn Miller.She met her future husband Patrick, now a prominent surgeon, while still in college. Reeves, the moderator, asked about the moment Patrick visited her parents in Miami to ask for her hand in marriage. Her father reminded him of the realities of interracial unions, which were still relatively rare in the 1990s.

“Patrick was willing to acknowledge that and accepted it, and what that meant for us, teaching and raising our daughters to be proud of who they are,” Jackson emphasized.

After Justice Antonin Scalia’s passing in 2016, Jackson’s youngest daughter, Leila, then 11, encouraged her mother to “apply” for the Supreme Court. When Jackson explained that presidents nominate justices, Leila sent a letter to President Barack Obama, signing off with, “Thank you for listening!”

At the time, Jackson said she thought that if her daughter “was not afraid to speak her mind even to the president of the United States, I must be doing something right.”

Jackson also reflected on the personal sacrifices of her legal career, including cutting her hair short during her Supreme Court clerkship to avoid time-consuming haircare routines. Sixteen years ago, with the help of her stylist, she returned to her sisterlocks as an affirmation of her heritage, she said.

In an interview following Jackson’s appearance, Sylvia Randolph, a longtime volunteer at the Library, said she appreciated Jackson’s openness about her family life.

“She didn’t have time for distractions or [to] give time to anything other than her work — not even her hair,” Randolph said. “I’ve gone through that journey. Sometimes, the little things that mean a lot have to go.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

February 18, 2025

Big Pat Bane, Tallest Soldier in the Civil War?

-This is a guest post by Candice Buchanan, a reference librarian in the History and Genealogy Section.

— Editor’s note: Due to an editing error, the original headline on this story omitted the question mark. This story has been updated to reflect reports of the Confederate soldier Martin Van Buren Bates and others. We’re writing another post about Bates, so be sure to check back on the blog.

William Patterson Bane, the Greene County Giant, one of the tallest soldiers in the Civil War, earned an almost mythical place in popular culture of late 19th-century America. He fought for the Union.

Martin Van Buren Bates, aka the Kentucky Giant, who fought for the Confederacy, was equally legendary and may have been even taller.

At a well-documented 6 feet, 9 inches (but sometimes reported as 7 feet 4 inches or “over 8 feet,”) Bane was a cheerful, blue-eyed Pennsylvania native appeared otherworldly. Clothes never fit Big Pat. His feet came out of his shoes. Crowds swarmed. Children ran and laughed and gaped. He led parades. Fellow soldiers, particularly at reunions, gawped and guffawed.

“A continuous shout ran along the line as the giant of Pennsylvania moved by,” wrote the Daily Public Ledger in Maysville, Kentucky, in September of 1893, recounting Bane’s progress during a parade of Union Army veterans.

“…groups of children and their elders, too, gathered about him to gaze up into his face and ask him strange questions of how it felt to be a giant,” reported the Montpelier Examiner of Idaho, picking up a story from across the country.

I learned a good bit about Pat — a modest farmer and shingle maker by trade — in my work as a genealogist, as he hailed from the same southwestern Pennsylvania counties of Washington and Greene that my ancestors called home.

He was born in Washington County but lived much of his life in Greene. He served during the Civil War in the Company A, 22nd Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment (Ringgold Battalion), apparently not seeing close conflict and being mustered out after the conflict ended. He’s buried beneath a simple marker in the veterans section of Washington Cemetery.

But by no means was he just a local hero. He was a newspaper darling, inspiring headlines nationwide for decades. No one knows for sure if he was, to a degree of scientific certainty, actually the tallest soldier in the Civil War. In the hunt for the title, you’ll come across names like Bates, Henry Clay Thurston, Thomas Marshal Jones, Mahlon Shaaber and several others. Since they never all lined up side by side, or had apples-to-apples measurements, there’s little way of documenting who was actually the tallest.

Bates, meanwhile, fought for both Kentucky and Virginia during the Civil War, ending the conflict at the rank of Captain. He later toured as a circus act sideshow and was popular as such in Europe. He doesn’t seem to have the same medical documentation as Bane, perhaps in part because as a Confederate, he was not eligible for a military pension after the war. But as an adult he was most often reported being anywhere from 7 feet 2 inches to 7 feet 11 inches. The Guinness Book of World Records lists him at both 7 feet 9 inches and 7 feet 11 inches and as being the half of the “Tallest Married Couple Ever.” Anna Haining Swan, his wife, was listed as 7 feet 11 inches. They toured as a circus act, both together and apart.

The complication?

While reports of Bane, Bates and others were often clearly exaggerated, Bane’s pension records document his height at several times by different doctors. Once Bates entered the circus world, reports of height were more likely to be overstated for commercial purposes. Guinness does not list their source for his height; we’ve reached out to them for documentation.

So, how tall was Big Pat exactly? It depends on who was doing the telling, and this gives us a glimpse into how unreliable all such reports were during the era. One way to explore this issue is through the Library’s Chronicling America historical newspaper database, which, among other Library collections, enables modern researchers to peek into the life of this lofty cavalryman.

Most consistent are the medically detailed surgeon’s certificates that accompanied his postwar pension claims. These put him at the aforementioned 6 feet, 9 inches. His earlier enlistment and military records, though, put him at a mere 6 feet, 5 inches. (This may have been intentional, to get around Army medical regulations regarding height, or perhaps he just grew later. He was 20 when he enlisted.) The National Tribune in Washington, D.C, reported that he stood “exactly 7 feet.” The man himself listed that as his height in an ad seeking a spouse. Still, a widely reprinted news report of his death pegged him at 7 feet, 4 inches. Not to be outdone, The Day Book, a Chicago newspaper, authoritatively stated “He was over 8 feet in height.”

The one thing everyone agreed on was that his personality matched his size.

He liked to draw attention through his wardrobe, props and poses. A widely reprinted story about the Union Army parade in Pittsburgh in November 1894 noted (as in The National Tribune) that Bane “… is very slender, and always on dress occasions wears a high silk hat, which adds greatly to his elongated appearance.”

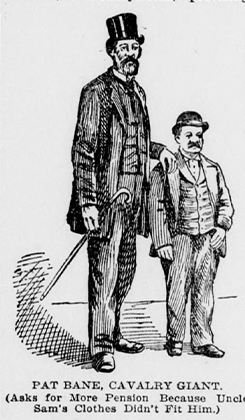

Pat Bane in an 1898 newspaper sketch. The Freeland Tribune. Chronicling America.

Pat Bane in an 1898 newspaper sketch. The Freeland Tribune. Chronicling America. A longer version of the same story, reprinted in Wyoming in the Rawlins Republican, noted that as Pat led his veterans unit “… cheers greeted him everywhere. In fact, Pat received a genuine ovation, which he returned with a smile.” And: “His manners are affable, and in his nature there is a large vein of humor. He considers it quite a joke to stand beside as small a specimen of manhood as he can find and make him look as diminutive as possible.”

The Montpelier Examiner in Idaho later recounted his joy as he once was swarmed at a circus, and the Baltimore County Union remarked on his status as the tallest spectator at the inauguration of President Theodore Roosevelt, the fourth such event Bane traveled to witness.

One thing that eluded such a good-natured man, however, was a spouse. On Jan. 19, 1893, Bane advertised in the National Tribune for a wife. His request appeared alongside 11 others who “desire[d] correspondence with a view to matrimony.” Each of these hopefuls provided a name and address. The only one to include any particulars was Bane, whose line read, “William P. Bane, Nineveh, Pa., (lady must be six feet six inches in h[e]ight, no less).”

It did not get the results he wanted. Not only did he run a second ad on Nov. 9, 1893, but he also repeated his height stipulation and required a photograph. Most notably — perhaps revealing something about the responses he received to his first ad — he included a closing statement: “No foolishness.”

Entertained by these specifications, the New Dominion in Morgantown, West Virginia, chortled “Pat seems to have high notions.”

Though there are several allusions to Bane’s matrimonial aspirations in the media, as well as in his military pension correspondence and depositions, there is no evidence that he ever married.

He also had health issues. Late in life, he reported problems with bronchitis, first contracted while on picket duty during the Civil War. On March 17, 1898, a headline on the front page of the Freeland Tribune in Pennsylvania read, “Wants More Pension. Giant Pat, the Tallest Man in the Civil War. Alleges Disabilities Due to the Poor Fit of His Uniforms.”

The article diminished Pat’s military service as “not especially noteworthy” and questioned his eligibility for support, claiming his disabilities “do not prevent him from plying his trade of shinglemaker … or from traveling about the country as extensively as possible on the spending money paid him by Uncle Sam.” They summed him up as “a very tall and healthy man … whose only troubles appear to come from his tailor and his shoemaker.”

At the time, Pat was receiving a veteran’s pension of $12 per month. He tried to convince pension boards that should be upped to the maximum of $30, arguing that his disability was “contracted in the service,” but was not successful. It was later increased to $17, but this seemed more related to inflation than to any particular ailment.

On March 16, 1912, the ever-cheerful Pat Bane passed away in Washington County, Pennsylvania. He was 68. His death made news across the nation, as headlines from Connecticut’s Bridgeport Evening Farmer to South Dakota’s the Lemmon Herald declared that the Union’s tallest soldier had led his last parade.

In the county where he would be laid to rest, his height remained his defining characteristic — even if no one ever knew quite what it was. A local newspaper, the Charleroi Mail, wrote that “the coffin in which Pat will be buried … with full military honors will be the largest ever ordered from Washington, measuring seven and one half feet.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Big Pat Bane, The Tallest Soldier in the Civil War

-This is a guest post by Candice Buchanan, a reference librarian in the History and Genealogy Section.

William Patterson Bane, the Greene County Giant, was almost certainly the tallest soldier in the Civil War, earning an almost mythical place in popular culture of late 19th-century America.

At a towering 6 feet, 9 inches, the cheerful, blue-eyed Pennsylvania native appeared otherworldly. Clothes never fit Big Pat. His feet came out of his shoes. Crowds swarmed. Children ran and laughed and gaped. He led parades. Fellow soldiers, particularly at reunions, gawped and guffawed.

“A continuous shout ran along the line as the giant of Pennsylvania moved by,” wrote the Daily Public Ledger in Maysville, Kentucky, in September of 1893, recounting Bane’s progress during a parade of Union Army veterans.

“…groups of children and their elders, too, gathered about him to gaze up into his face and ask him strange questions of how it felt to be a giant,” reported the Montpelier Examiner of Idaho, picking up a story from across the country.

I learned a good bit about Pat — a modest farmer and shingle maker by trade — in my work as a genealogist, as he hailed from the same southwestern Pennsylvania counties of Washington and Greene that my ancestors called home.

He was born in Washington County but lived much of his life in Greene. He served during the Civil War in the Company A, 22nd Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment (Ringgold Battalion), apparently not seeing close conflict and being mustered out after the conflict ended. He’s buried beneath a simple marker in the veterans section of Washington Cemetery.

But by no means was he just a local hero. He was a newspaper darling, inspiring headlines nationwide for decades. No one knows for sure if he was, to a degree of scientific certainty, actually the tallest soldier in the Civil War. But the fact that he was assserted as such for decades, without contradiction, makes a compelling case.

Many of these accounts are preserved through the Library’s Chronicling America historical newspaper database, which, among other Library collections, enables modern researchers to peek into the life of this lofty cavalryman.

How tall was Big Pat exactly? It depends on who was doing the telling.

Most consistent are the medically detailed surgeon’s certificates that accompanied his postwar pension claims. These put him at the aforementioned 6 feet, 9 inches. His earlier enlistment and military records, though, put him at a mere 6 feet, 5 inches. (This may have been intentional, to get around Army medical regulations regarding height, or perhaps he just grew later. He was 20 when he enlisted.) The National Tribune in Washington, D.C, reported that he stood “exactly 7 feet.” The man himself listed that as his height in an ad seeking a spouse. Still, a widely reprinted news report of his death pegged him at 7 feet, 4 inches. Not to be outdone, The Day Book, a Chicago newspaper, authoritatively stated “He was over 8 feet in height.”

The one thing everyone agreed on was that his personality matched his size.

He liked to draw attention through his wardrobe, props and poses. A widely reprinted story about the Union Army parade in Pittsburgh in November 1894 noted (as in The National Tribune) that Bane “… is very slender, and always on dress occasions wears a high silk hat, which adds greatly to his elongated appearance.”

Pat Bane in an 1898 newspaper sketch. The Freeland Tribune. Chronicling America.

Pat Bane in an 1898 newspaper sketch. The Freeland Tribune. Chronicling America. A longer version of the same story, reprinted in Wyoming in the Rawlins Republican, noted that as Pat led his veterans unit “… cheers greeted him everywhere. In fact, Pat received a genuine ovation, which he returned with a smile.” And: “His manners are affable, and in his nature there is a large vein of humor. He considers it quite a joke to stand beside as small a specimen of manhood as he can find and make him look as diminutive as possible.”

The Montpelier Examiner in Idaho later recounted his joy as he once was swarmed at a circus, and the Baltimore County Union remarked on his status as the tallest spectator at the inauguration of President Theodore Roosevelt, the fourth such event Bane traveled to witness.

One thing that eluded such a good-natured man, however, was a spouse. On Jan. 19, 1893, Bane advertised in the National Tribune for a wife. His request appeared alongside 11 others who “desire[d] correspondence with a view to matrimony.” Each of these hopefuls provided a name and address. The only one to include any particulars was Bane, whose line read, “William P. Bane, Nineveh, Pa., (lady must be six feet six inches in h[e]ight, no less).”

It did not get the results he wanted. Not only did he run a second ad on Nov. 9, 1893, but he also repeated his height stipulation and required a photograph. Most notably — perhaps revealing something about the responses he received to his first ad — he included a closing statement: “No foolishness.”

Entertained by these specifications, the New Dominion in Morgantown, West Virginia, chortled “Pat seems to have high notions.”

Though there are several allusions to Bane’s matrimonial aspirations in the media, as well as in his military pension correspondence and depositions, there is no evidence that he ever married.

He also had health issues. Late in life, he reported problems with bronchitis, first contracted while on picket duty during the Civil War. On March 17, 1898, a headline on the front page of the Freeland Tribune in Pennsylvania read, “Wants More Pension. Giant Pat, the Tallest Man in the Civil War. Alleges Disabilities Due to the Poor Fit of His Uniforms.”

The article diminished Pat’s military service as “not especially noteworthy” and questioned his eligibility for support, claiming his disabilities “do not prevent him from plying his trade of shinglemaker … or from traveling about the country as extensively as possible on the spending money paid him by Uncle Sam.” They summed him up as “a very tall and healthy man … whose only troubles appear to come from his tailor and his shoemaker.”

At the time, Pat was receiving a veteran’s pension of $12 per month. He tried to convince pension boards that should be upped to the maximum of $30, arguing that his disability was “contracted in the service,” but was not successful. It was later increased to $17, but this seemed more related to inflation than to any particular ailment.

On March 16, 1912, the ever-cheerful Pat Bane passed away in Washington County, Pennsylvania. He was 68. His death made news across the nation, as headlines from Connecticut’s Bridgeport Evening Farmer to South Dakota’s the Lemmon Herald declared that the Union’s tallest soldier had led his last parade.

In the county where he would be laid to rest, his height remained his defining characteristic — even if no one ever knew quite what it was. A local newspaper, the Charleroi Mail, wrote that “the coffin in which Pat will be buried … with full military honors will be the largest ever ordered from Washington, measuring seven and one half feet.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

February 14, 2025

My Job: D’Andrea Hamn, Copyright and Union Work

D’Andrea Hamn is an acquisitions program specialist in the U.S. Copyright Office.

Tell us about your background.

I grew up in Stafford, Virginia, after my father retired from the Marine Corps base located in Quantico, Virginia.

I graduated from Stafford High School with a curriculum in business, from Germanna Community College with a certificate in business machines and from Prince George’s Community College with an associate’s degree in business management.

I also completed coursework at the University of Maryland’s Global Campus in business administration and management.

What brought you to the Library, and what do you do?

I was working with a temp agency doing all types of secretarial assignments and was seeking full-time work. I applied for a typing job and began my career at the Library on April 27, 1976, in what is now the Cataloging in Publication and Dewey Section, then located on Massachusetts Avenue.

I went on to hold various positions in the U.S. Copyright Office, ranging from a technician to a team leader to a supervisor.

In 2004, I transferred to the Copyright Acquisitions Division on a detail. I was promoted to program specialist in the division in 2005 and to program specialist/special assistant to the chief in 2007. In 2011, I was promoted to acquisitions program specialist to the assistant chief of the division.

The division’s name changed a few years ago. It is now called Acquisitions and Deposits, but my position remains the same. I am in charge of daily workflows with numerous duties supporting the acquisitions technicians and librarians, the chief of the division and the supervisory librarians. I also work with staff of the Technical Processing Unit within the division and its supervisor.

What are some of your standout projects?

There are too many to name over my career at the Library.

But I pride myself in my affiliation and memberships with the staff unions — AFSCME Local 2910 (the Guild) and Local 2477. While a member of 2477, I was a steward for over 15 years. I worked hard to change policies and procedures affecting many lives.

I also take pride in my work ethic and outstanding performance reviews. I have always strived to help others and meet goals to enhance the divisions I worked for and the Library’s goals.

What do you enjoy doing outside of work?

Shopping, cooking, using new recipes, keeping up with the latest trends, crafting and being with family.

What is something your co-workers may not know about you?

I am an artist in the book folding world. I take books and make their pages into words, designs and shapes. From the many books I’ve created for various clients, I am proud to say these special book creations are housed or shelved in more than 10 states.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

February 7, 2025

Free! Winter Images

The Library’s Free to Use and Reuse sets of photographs and prints are copyright-free, yours to use any way you like. They cover any number of intriguing subjects – travel posters, grand movie theaters, genealogy – and they are completely free.

Let’s pick three from the Winter set, since a couple of winter storms are sweeping across the Midwest and Northeast this week.

Sawing ice blocks was hard, slow work. Photo: Detroit Publishing Co. Prints and Photographs Division.

Sawing ice blocks was hard, slow work. Photo: Detroit Publishing Co. Prints and Photographs Division.At first glance, this looks to be a vintage picture of snow shoveling, an ancient rite of winter. But look closer. That’s an ice saw, a thing that exists now almost entirely for those hardy souls who enjoy fishing in the deepest days of winter.

But when this picture was taken, in the first decade of the 20th century, ice saws, ice blocks, ice houses and ice boxes were common things. The delivery guy was known as the ice man. Horse-and-buggy wagons delivering huge slabs of ice were staples of winter life.

What we now call a refrigerator was invented in 1913, but a self-contained unit didn’t come along until a decade later and the use of Freon as a cooling agent was introduced around 1930. Those first units were wildly expensive, making them luxury items.

Non-mechanical cooling units, or informal ways of keep food and beverages chilled, had been around for centuries. Damp, cool pits were popular solutions, often with ice chopped up in winter, stored underground and used throughout the warmer months.

By the late 19th century in the U.S., the typical home had a refrigerator, but it’s what we would now call an icebox – a waist-high wooden cabinet with several compartments, secured with latches and handles, the interior lined with tin.

Getting the ice, though, wasn’t so easy.

The building blocks of the business were ice chunks cut out of frozen lakes and rivers as pictured here. Using an extremely sharp saw, workers carved a chunk out of the ice and used heavy metal tongs to lift it out and onto a wagon, then into a storage facility and delivered, house by house, business by business.

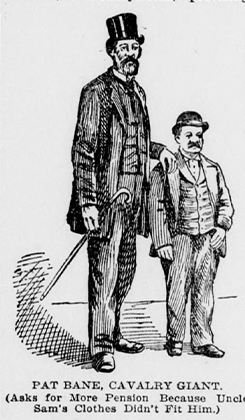

A stylish photographer by the pool in Palm Beach, Florida, in December 1954. Photo: Toni Frissell. Prints and Photographs Division.

A stylish photographer by the pool in Palm Beach, Florida, in December 1954. Photo: Toni Frissell. Prints and Photographs Division. Check out our man in Palm Beach right here! This is sunny Florida in the winter of 1954, and our friend is sporting a tropical shirt and a razor-sharp crease in those slacks. He’s at the high-end La Coquille Club, using a twin lens reflex camera, most likely a Rolleiflex.

The picture is from a Sports Illustrated photo essay, “Sporting Look,” by famed photographer Toni Frissell in midcareer form. She was primarily a high-end fashion and society photographer for the glossy magazines of the day, but revealed a new depth to her career during World War II, when she volunteered for the Red Cross and shot an influential range of photographs of Americans at war.

How trendy was La Coquille?

Its website notes the beachfront club was built in the early 1950s, about the time it “became one of the premiere destinations for celebrities, diplomats, and captains of industry as the Fords and Vanderbilts swam with Esther Williams, danced alongside Ginger Rogers, and downed gimlets with the Duke and Duchess of Windsor at the club’s Tortoise Bar.”

The club was demolished in the 1980s for the Eau Palm Beach Resort & Spa, but La Coquille endures within the larger resort.

Handmaking snowshoes in Alaska between 1900 and 1930. Photo: Frank and Frances Carpenter collection. Prints and Photographs Division.

Handmaking snowshoes in Alaska between 1900 and 1930. Photo: Frank and Frances Carpenter collection. Prints and Photographs Division. Snowshoes have been an integral part of winter weather for thousands of years, with the traditional one we think of today – the webbed footing inside a larger wooden frame – created by Native Americans. These shoes were found across all the snowy climes, from the Northeast to the Arctic.

The documentary-style photograph of a shoemaker at work here is part of the Frank and Frances Carpenter collection. Frank Carpenter was a highly influential globe-traveling journalist and photographer in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His dozens of travel books were popular and textbooks he wrote became standard fare in U.S. classrooms for decades.

Along with his daughter, Frances, he traveled and photographed Alaska over the course of 14 years, from 1910 to 1924. Their work, totaling more than 16,000 images and 7,000 negatives, is preserved at the Library, and in this case gives us a window into an age-old craft.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

February 6, 2025

Parallel Lives: King George and George Washington, Featured in an Upcoming Exhibit

-This is a guest post by Julie Miller, a historian in the Manuscript Division. It also appears in the January-February edition of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Because George Washington and George III were on opposite sides of America’s war of independence from Britain, we have learned to think of them as opposites.

Our research for an upcoming Library of Congress exhibition, “The Two Georges: Parallel Lives in an Age of Revolution,” however, has turned up something much more interesting: They were surprisingly alike in temperament, interests and, despite the obvious differences in their lives, experience.

The exhibition, which opens in March, is a close look at the lives of George Washington, first president of the United States, King George III of Great Britain and the world they shared. It features the papers of George Washington, at the Library, and those of George III, at the Royal Archives, which is housed at the picturesque round tower of Windsor Castle. Objects and images from London’s Science Museum, Mount Vernon and other repositories also will be included. A companion exhibition will open at the Science Museum in 2026.

While Washington came to be viewed as the embodiment of the American republic, he, like George III, began his life as a subject of Britain’s King George II. Growing up in Colonial Virginia, Washington showed no sign of the revolutionary he would later become. Instead, he took advantage of Colonial ladders of power, and he actively promoted British expansion in North America as a surveyor and as an officer in the French and Indian War.

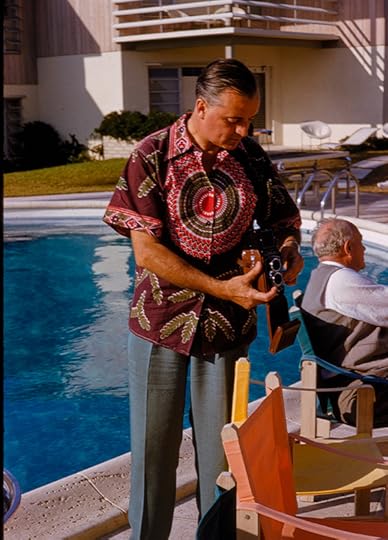

Detail of a 1779 George Washington portrait by George Willson Peale. Cleveland Museum of Art.

Detail of a 1779 George Washington portrait by George Willson Peale. Cleveland Museum of Art.Like other Virginia tobacco planters, he sold his crop to British merchants and with the proceeds outfitted himself as a fashionable London gentleman — at least until 1769, when he took his place as a leader of Virginia’s movement to boycott British goods to protest the imposition of British taxes.

But even in 1776, when Washington abandoned his identification as a British subject and adopted a new identity as an American, he had something in common with the other George.

George III had also, years earlier, made a deliberate assertion of national identity. His great-grandparents, grandparents and parents all were born in Germany and spoke German as a first language. In a speech to Parliament after his accession to the crown in 1760, he reassured his subjects: “Born and educated in this country, I glory in the Name of Britain.”

In private, the two Georges also had something in common: They were both the eldest sons of widowed mothers. Mary Ball Washington became a widow in 1743 when her husband, Augustine Washington, died. Her son George was 11. Princess Augusta of Wales lost her husband, Frederick, Prince of Wales, in 1751, when her George was 12.

Widowhood granted both women power that neither law nor custom allowed them when their husbands were alive. Mary Ball Washington became her family’s head, in charge of managing its property. Princess Augusta closely controlled her George’s upbringing and education. In claiming power for themselves, they attracted the scorn of men, both in their lifetimes and afterward. Only recently have historians and biographers begun a reassessment of Mary Washington and Princess Augusta that takes into account the prejudices and disadvantages they faced as women. Both Georges later formed marriages according to an Enlightenment model of virtuous family life in which women were granted an increasingly respectful, if still not equal, place.

In temperament the Georges were surprisingly alike. Both were committed to the virtuous values of duty, modesty and restraint. They were homebodies: George III never left Britain, not even to visit the German electorate of Hanover, whose rule he had inherited from Georges I and II. He didn’t travel much in Britain, either. Washington traveled the American Colonies during his military career, and he toured the states as president. But he left the American mainland only once, to go to Barbados with his brother in 1751.

Both Georges were committed to family life: As king, George III, his wife, Queen Charlotte, and their 15 children managed to convey the impression that they weren’t much different from a middle-class British family (even though they lived in a castle). The idea of the “royal family” evolved during the reign of George III.

Detail of a portrait of King George III and Queen Charlotte with several of their children. Mezzotint: John Murphy. Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025/Royal Collections Trust.

Detail of a portrait of King George III and Queen Charlotte with several of their children. Mezzotint: John Murphy. Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025/Royal Collections Trust. Washington’s lifelong commitment to the house and five farms of Mount Vernon on Virginia’s Potomac River was equal to his devotion to the family of children and grandchildren he acquired when he married, even though he and Martha Washington had no children of their own.

The greatest passion the two leaders shared was for agriculture, in particular, the new methods of farming, gardening and landscape design pioneered by wealthy landowners in 18th-century England that were a dimension of Enlightenment science.

Soon after his marriage, Washington sent to England for “the newest, and most approved Treatise of Agriculture” and, over the years, many other similar works. Many of the books on this subject that Washington owned, read and made notes on also were in George III’s library.

They both drew up crop rotation charts and took an interest in animal husbandry, cover crops and the design of farm buildings. George III earned the nickname “Farmer George” for his well-known agricultural interests. There was one significant difference in their methods, however: Washington used an enslaved work force. While the king profited from the coerced labor of enslaved workers in Britain’s American and Caribbean colonies, he did not have the same intimate engagement with slavery that Washington did.

Enlightenment only went so far.

The Georges lived during a complex era of change when the Enlightenment values of reason and humanitarianism and the expansion of individual rights were starting to take hold, while at the same time older practices of inherited status, hierarchy and dominance persisted. This paradox is present in the shared indifference of the two Georges to the suffering of the enslaved people whose coerced labor contributed to their wealth, even as movements to end slavery developed in both Britain and the United States in the 18th century.

Neither George was convinced by the abolitionist argument that slaves were entitled to full human rights, yet while both were in power Britain and the United States moved to end the international slave trade, though not slavery itself. In 1787, Washington signed the federal Constitution, whose Article 1, Section 9 set the United States on a path to end the international slave trade in 1808. As president, however, he deflected any action prior to that.

These etchings of King George III and George Washington, circa 1780-1790s, may have been part of a French print sellers sample book. Prints and Photographs Division.

These etchings of King George III and George Washington, circa 1780-1790s, may have been part of a French print sellers sample book. Prints and Photographs Division.After a visit from a Quaker abolitionist during his first term as president, Washington wrote: “The memorial of the Quakers (and a very mal-apropos one it was) has at length been put to sleep” and will not “awake before the year 1808.”

Washington did doubt the morality of slavery, and on another occasion he wrote that it was “among my first wishes to see some plan adopted, by the legislature by which slavery in this Country may be abolished by slow, sure, & imperceptable degrees.” Nonetheless, he never let go of the idea that he had the right to regard people as property. Pushed by political forces outside his control, George III signed Britain’s “Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade” in 1807. His papers, however, are notably silent on the question of slavery.

The idea that the two Georges, who never met, had some things in common is important because it deepens our understanding of these two consequential figures. We have tended to see both of them through a scrim of myth, but their papers, which reveal them in almost every dimension, help us get to know them as real, complicated people who lived through the same historical times within the boundaries of the same Atlantic world.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Mac Barnett Named New National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature

This is a guest post by Deb Fiscella, a public affairs specialist in the Office of Communications.

Mac Barnett, the bestselling author of more than 60 children’s books, including “Twenty Questions,” “Sam & Dave Dig a Hole,” “A Polar Bear in the Snow” as well as the “Mac B., Kid Spy” series, will be inaugurated today as the 2025-2026 National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature.

Barnett has won numerous prizes, including two Caldecott Honors, three New York Times/New York Public Library Best Illustrated Awards, three E.B. White Read Aloud Awards, and an International Children’s Literature Award.

“I’m excited for Mac Barnett’s tenure as the National Ambassador,” said Carla Hayden, the Librarian of Congress. “The way he elevates the picture book with originality and intentionality, making space for young readers to embrace the unknown, is magical.”

Barnett is the ninth author to hold this position; he succeeds Meg Medina, who served as the ambassador from 2023 through 2024.

“It’s a profound honor,” Barnett said. “When I got the news, I was speechless, which is unusual for me. Now I feel energized to proclaim the many glories of children’s literature, with a particular focus on a unique and marvelous way of telling stories: the children’s picture book.”

Barnett began working with children as a high school and college student, and these early experiences inspired a dream of writing for them. He’s known for his deep respect for children – for their intelligence, their emotional acumen and their time and attention.

“Picture books are a beautiful, sophisticated and vibrant art form, the source of some of the most profound reading experiences in children’s (and adults’) lives,” he said.

During his two-year term as ambassador, Barnett will showcase the children’s picture book through his platform, “Behold, The Picture Book! Let’s Celebrate Stories We Can Feel, Hear, and See.” Barnett will explore the ways picture books blend words and illustrations to create a powerful reading experience, one that is often the foundation for a lifetime of reading. Ultimately, Barnett will assert the picture book is a quintessential American art form and deserves its rightful place among the best American literature.

“We couldn’t be more pleased with the selection of Mac Barnett as the next ambassador,” said Shaina Birkhead, associate executive director of Every Child a Reader, which partners with the Library in administering the program. “Who better to champion picture books in this national role than someone who has been doing just that their entire career?”

Hayden will formally inaugurate Barnett today at 11 a.m. The program will be livestreamed on the Library’s YouTube page.

For those in the D..C. area, you can meet Barnett in a “Storytime for Grown Ups” event at 6:30 p.m. in the Thomas Jefferson Building. For those further afield, proposals are now being accepted from schools, libraries and community groups to host Barnett this year. The deadline for proposals is March 3.

The National Ambassador position was established in 2008 to raise awareness of the importance of young people’s literature for lifelong literacy and education. The selection, made by the Librarian of Congress, is based on recommendations from a diverse group of children’s literature publishing professionals, as well as an independent committee comprised of educators, librarians, booksellers and children’s literature specialists.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

January 30, 2025

“V as in Victim,” The Library’s Newest Crime Classic

This is a guest post by Zach Klitzman, a writer-editor in the Library’s Publishing Office .

“All we want are the facts, ma’am,” from “Dragnet.”

“Book ’em, Danno,” from “Hawaii Five-O.”

David Caruso flipping on his sunglasses before offering a pithy line in “CSI: Miami.”

These and other cop-show catchphrases have their roots in Lawrence Treat’s 1945 novel “V as in Victim,” the newest Library of Congress Crime Classic.

“V” was the first crime novel to feature ordinary cops and their plain language as the main attraction, launching the subgenre known as police procedurals and earning Treat an important place in American pop culture.

The procedural has since become a standard narrative of American entertainment, from novels to television series to films. Bestselling authors such as Ed McBain, Joseph Wambaugh, Patricia Cornwell and Michael Connelly have become staples in bookstores; “Hill Street Blues” and “Law and Order” are two of the dozens of television series that have influenced the field; “L.A. Confidential,” “The Silence of the Lambs” and “Mystic River” are Academy Award–winning procedurals on film.

Treat, born Lawrence Arthur Goldstone in 1903 in New York City, first became a lawyer. But after his firm broke up in 1928, he moved to Paris and soon got free room and board from a friend in Brittany. With time on his hands, he tried poetry, but found success with what he called “crime mystery picture puzzle books,” selling his first one in 1930. He returned to the U.S. and started writing crime stories, publishing short stories in mystery magazines as well as full-length novels, taking up the pen name of Lawrence Treat.

In his influential “V,” New York City police detective Mitch Taylor and lab technician Jub Freeman are called to the scene of a hit and run. None of the witnesses are particularly helpful — but one says a woman screamed before the accident from the overlooking apartment building.

Investigating the incident leads to a dead cat, a murdered paramour, a heavy drinker in the middle of a divorce and other shady characters. Set in the fall of 1944, the novel features references to World War II, including the rationing taking place at home. The climax takes place against the backdrop of the Great Atlantic Hurricane of 1944, which hit New York City that September.

In the decades prior to “V,” crime writing focused on amateur but brilliant sleuths like Sherlock Holmes. These stories often portrayed the police as “as unimaginative, ineffectual, boring, or a combination of all three,” writes series editor Leslie S. Klinger in the book’s introduction. Treat, however, believed that real police techniques, including the burgeoning science of forensics, could lead to a satisfying mystery.

Treat followed up “V” with several other procedurals, including “H as in Hunted,” “Q as in Quicksand,” “T as in Trapped” and “F as in Flight.” Two other procedurals from the era appear in the Crime Classics series: “Last Seen Wearing” by Hillary Waugh and “Case Pending” by Dell Shannon.

During a career that spanned 70 years, Treat wrote 17 novels and several hundred short stories, many of which were not police procedurals. A founding member of the Mystery Writers of America, he served the organization in several roles and received its top award, the Edgar, in 1965 for his short story “H as in Homicide” and for the “Mystery Writer’s Handbook” in 1976. He was also given a special Edgar award in 1987 for a television episode in “Alfred Hitchcock Presents.” He died in 1998.

Library of Congress Crime Classics are published by Poisoned Pen Press, an imprint of Sourcebooks, in association with the Library. “V as in Victim” is available in softcover ($15.99) from booksellers worldwide, including the Library of Congress Store.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

January 28, 2025

A Looted Bible, Returned to the Library

—This is a guest post by Allison Buser, a reference assistant in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division. It also appears in the January-February issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

The order that resulted in the devastation of the first congressional library during the War of 1812 arrived in the city of Washington on Aug. 24, 1814. As word reached Washington of the impending arrival of British forces, government officials and citizens fled.

The British easily marched in, ransacked and burned the Treasury, the President’s House (the White House), the Navy Yard, the Capitol (and the Library of Congress inside) and other federal buildings. Troops were ordered not to pillage or destroy civilian property, a command that largely was respected.

But one Royal Marines officer, Nathanael Cole, decided to extricate a keepsake, though it’s not clear from where: a King James family Bible, printed in Philadelphia in 1807 by Mathew Carey.

Cole later gave his prize to his sister-in-law, and it became the Cole/Dean family Bible. In the family record section, the family logged generations of births, marriages and deaths.

“This Bible was taken at the Battle of Washington….” an insert into the Cole/Dean family Bible details its history. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

“This Bible was taken at the Battle of Washington….” an insert into the Cole/Dean family Bible details its history. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.At some point during the Bible’s British captivity, a paper was attached to the inner front cover relating how the family came to possess the Bible, along with an injunction that it was “never to be given out of the Family.”

That order notwithstanding, the Bible eventually was gifted to the United States and returned to Washington with a second paper, attached to the inner back cover, inscribed thusly:

“This bible having left the possession of the family of Major Cole, for reasons and by ways unknown to the present owner, is returned to Washington by Commander Harry Bent Royal Navy as a gesture of goodwill and gratitude to the people of the United States of America. September 1957.”

After the 1812 ransacking, Washington was gradually rebuilt, and its collections of books, cultural artifacts and institutions expanded far beyond what was destroyed. Like the city, this Bible — now part of the Library’s collections — has endured over 200 years and bears the marks of its history.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

January 22, 2025

The (Sun) King’s View of the World

— This is a guest post by Sahar Kazmi, a writer-editor in the office of the chief information officer. It also appears in the January-February issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Louis XIV of France, the absolutist Sun King who ruled his nation from the monumental, lavish palace of Versailles, was not a man known for his modesty.

His personal world atlas, a large two-volume set of more than 120 maps now held in the Library’s Geography and Map Division, may not have been the monarch’s most ornate possession, but it created an appropriately memorable splash when it was unveiled in 1704.

Distinguished by special binding and the king’s royal cypher, or monogram, the atlas opens with a title page engraving showing a stately Louis XIV beside a map of the British Isles, his foot crushing the symbolically snake-haired man writhing beneath it.

The huge world map that follows is one of the most exceptional and scandalous features of the royal atlas. Although its creator, Jean-Baptiste Nolin, would later be sued for plagiarizing its greatest cartographic innovations, the map was groundbreaking.

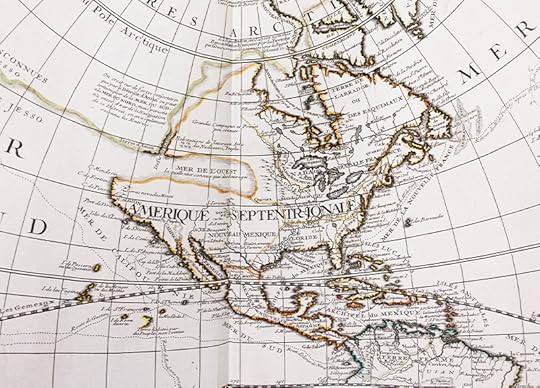

Jean-Baptiste Nolin’s 1704 map of North America. Geography and Map Division.

Jean-Baptiste Nolin’s 1704 map of North America. Geography and Map Division.It was the first world map to show the mythical Sea of the West, an eventually debunked inland sea in the Pacific Northwest. By depicting California as a peninsula, it also was the first world map to break a century-long trend of portraying the region as an island.

Other innovations include the first rendering of Australia’s east coast and a depiction of the start of French colonization in Louisiana.

In 1705, cartographer Guillaume De L’Isle (often also spelled Delisle) accused Nolin of stealing all of these concepts from a manuscript globe he’d created for the chancellor of France. Following a five-year legal battle that ended with his defeat, Nolin was discredited and forced to destroy the copperplates he used to create his world map.

During the controversy, Louis XIV issued new regulations to prevent future map forgeries and counterfeits. In true kingly fashion, however, he kept the contentious map in his own royal atlas.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers