Library of Congress's Blog, page 11

September 18, 2024

Louis Bayard’s Novel Research at the Library

Bestselling author Louis Bayard has written nine historical novels over the past two decades and has researched them all at the Library, poring over maps, sorting through personal love letters, consulting societal details of the lost worlds that he brings to life.

His latest novel, “The Wildes,” a fictionalized account of Oscar Wilde and his wife and children, was released this week. His penchant of weaving real people (Wilde, Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln, Edgar Allan Poe, Theodore and Kermit Roosevelt, Jacqueline Kennedy, etc.) into fictional adventures is so distinctive that The New York Times recently referred to it as “Bayardian.”

Creating a distinctive literary style over two decades — with books set across several centuries and three continents — takes a lot of work. A lot of that gets done in the Library’s stacks, reading rooms and collections, spread across three buildings on Capitol Hill. He’s on the Library campus so often that he has his own researcher shelf (#1433) in the stacks just off the Main Reading Room. He has lauded Abby Yochelson, a now-retired reference specialist in English and American literature, in the acknowledgements of several books as his “research angel.”

“It just makes you feel more secure when you’re putting these worlds together because they’re all lost to time,” he says during a recent interview at a Capitol Hill restaurant a few doors down from the Library. “I’m trying to reanimate them, and the only way to do that is through books, through the stacks.” A moment later, he adds: “The book is always telling me what I still need to know. It’s often considerable. That’s when I dash back to the Library.”

Louis Bayard researched the life, and particularly the trial, of Oscar Wilde, at the Library. Above: Wilde in 1882. Photo: Napoleon Sarony. Prints and Photographs Division.

Louis Bayard researched the life, and particularly the trial, of Oscar Wilde, at the Library. Above: Wilde in 1882. Photo: Napoleon Sarony. Prints and Photographs Division.Bayard is 60 and comes across much like his books do: urbane, witty, charming. He was born in New Mexico, grew up in Northern Virginia and went to college at Princeton. He got a master’s in journalism from Northwestern University and moved back to Washington, where he soon worked as a staffer for congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-D.C.) and for U.S. Rep. Philip Sharp (D-Ind.).

His books have been translated into more than a dozen languages, he’s served as chair of the PEN/Faulkner Awards and taught at George Washington University. He often writes about pop culture for major newspapers and magazines. The father of two sons, he lives with his husband, Don Montuori, on Capitol Hill, just a few blocks from the Library.

He’s also settled into a professional routine — a book about every two years — and a consistent research method. Once he’s settled on a new character storyline, he heads to the Library’s website and on-site resources and starts digging.

Let’s look back at the beginning to see how he got here.

By his late 30s, he’d written two contemporary novels that were perfectly fine but didn’t catch on. He struck out on a new tack with the idea of writing a historical thriller, following the fictional Timothy Cratchit (Tiny Tim in Charles Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol”) into adulthood. Bayard pictured him in London’s seamy 1860s underbelly, where he stumbles across the bodies of two dead young women, each of whom has been branded with the same mark.

But how was one to fill out nearly 400 pages with those “teeming markets, shadowy passageways and rolling brown fog” of the London demimonde, as “Mr. Timothy’s” dust jacket would ultimately promise?

Bayard, with his journalism background, went to the Library to do his due diligence. He at first found the place confusing if not bewildering. The Library is filled with collections from different eras — it’s not like Google — and some parts of a single subject might be found in contemporary books, or maybe in personal letters of participants, others in histories published decades (or centuries) later and still more in maps or in long-forgotten newspapers and magazines. These can be in different divisions and sometimes in different buildings. They have come in over nearly two centuries and might have been cataloged in ways that would have made perfect sense in 1890 but not so much so in 1990. Some were online, some were not.

This is when he met Yochelson, a highly respected research librarian.

“It wasn’t an easy process to figure out,” he says, “and I needed my friend Abby to practically hold my hand. But once I was in, I found Henry Mayhew, who was this amazing social scientist who was basically walking through the streets of London in the Victorian era and taking notes about everything he saw, the statistics, man-on-the-street interviews, everything. It was just like, ‘Oh my God, I’ve found the treasure trove. I’ve found gold.’ ”

The book sold well and drew strong critical reviews, and Yochelson was delighted to see some of the research she helped him find turn up in the book.

“I still remember he wanted to know what banking was like in Charles Dickens’ England,” she said in a recent phone call. “ ‘Would you get a check? What was a photography studio like?’ All sorts of things. Two years later, the book comes out and I would come across something and go, “Oh, there it is!”

She and Bayard have kept up their friendship, though she is modest about her help. “There are ‘research angels’ all over the library,” she says.

This 1830 map of West Point shows an icehouse at the top center, identified by an “I.” It gave author Louis Bayard the idea for a key plot point in “The Pale Blue Eye.” Geography and Map Division.

This 1830 map of West Point shows an icehouse at the top center, identified by an “I.” It gave author Louis Bayard the idea for a key plot point in “The Pale Blue Eye.” Geography and Map Division.Research magic struck again for his next book, “The Pale Blue Eye,” set at the U.S. Military Academy in West Point, New York, in 1830, when a young cadet named Edgar Allan Poe becomes caught up in a grisly murder mystery. (Poe really did attend the academy.) In the Geography and Map Division, Bayard came across a layout of the campus that showed, right in the middle, an icehouse. He made a copy of the map, kept it with him while writing to ensure accuracy and made the icehouse the central focus of the investigation.

That book did even better and was turned into a 2022 film starring Christian Bale.

In researching “Roosevelt’s Beast,” a tale about supernatural evil in the Amazon rainforest that has devastating effects on Kermit Roosevelt, the president’s son, he came across love letters in the Manuscript Division between Kermit and his fiancé, Belle Wyatt Willard. They were so touching that he used excerpts verbatim in the book.

“What have I done that God should choose me out of all the world for you to love — but as He has done this, so perhaps He will make me a little worthy of your love,” Willard wrote, in one passage Bayard quoted. “May He keep you safe for me! I love you, Kermit, I love you.”

“…I think it must be my soul going out across the world to you Beloved — to tell you how I love you — Good Night — Belle.” One of Belle Willard’s love letters to Kermit Roosevelt in 1914. Manuscript Division.

“…I think it must be my soul going out across the world to you Beloved — to tell you how I love you — Good Night — Belle.” One of Belle Willard’s love letters to Kermit Roosevelt in 1914. Manuscript Division.One hundred and ten years later, you can still hold the hotel stationery on which she wrote, see how delicately she pressed the pen into the paper. The passion, the intensity, the intimacy of her writing — it really does bring goosebumps.

It’s that kind of immediacy, Bayard says, that brings his lost worlds to life, that brings modern readers the touch of lives long gone.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

September 17, 2024

Ralph Ellison, Photographer

—This is a guest post by Barbara Bair, a historian in the Manuscript Division.

Ralph Ellison, author of the award-winning 1952 novel “Invisible Man” and the posthumously published “Juneteenth,” long has been celebrated as a writer, teacher and consummate cultural critic of jazz, African American literature and the blues.

But Ellison was a polymath, possessed of a wide range of interests and talents. He studied music at Tuskegee, apprenticed in sculpture as a young newcomer to New York and gathered street game lyrics from children in Harlem for the Federal Writers’ Project. He loved technology and design — and he was an accomplished photographer.

For a brief time before the success of “Invisible Man,” Ellison earned money as a freelance photographer. He took portraits for publishers and covered events for newspapers, from car accidents to dog shows. He continued to work artistically, documenting everyday pursuits and beauties of Manhattan life. He collaborated with Gordon Parks and shot images of literary friends like Langston Hughes and Richard Wright. He created intimate portraits of his wife, Fanny Ellison, and images of African Americans shopping and gathering together. He took pictures of children in the parks and on street corners.

Fanny Ellison poses for a fashion shot. Photo: Ralph Ellison. Prints and Photographs Division.

Fanny Ellison poses for a fashion shot. Photo: Ralph Ellison. Prints and Photographs Division.By the 1960s, he was captivated by Polaroids. He made still-life studies of modernist furniture, African artwork, computers, the television, plants and flowers, bookshelves and other objects in his apartment on Riverside Drive.

The Ralph Ellison Papers in the Library’s Manuscript Division contain documentation about his photographic equipment and assignments. Visual holdings in the Ellison collection in the Prints and Photographs Division, meanwhile, include over 23,000 images dating from circa 1930 to 1990 — nearly 300 of which have been digitized and are available online. The 2023 photo book, “Ralph Ellison: Photographer,” drew heavily on this collection.

The collection include pictures of the Ellisons in Manhattan and at their rural Massachusetts home, as well as a myriad of images that reveal to us Ellison’s unique visual conceptions from behind the camera’s eye — proof positive of his artistic imagination.

Ralph Ellison in St. Nicholas Park in New York City around 1950. Photo: Fanny Ellison.

Ralph Ellison in St. Nicholas Park in New York City around 1950. Photo: Fanny Ellison.Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

September 12, 2024

Inventing the Capitol Building

-This article also appears in the September-October issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

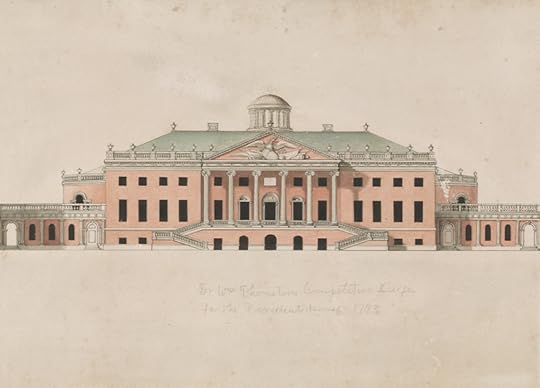

The U.S. Capitol building, the worldwide symbol of American democracy, got its beginnings on a piece of paper on the Caribbean island of Tortola, sketched out by a temperamental doctor in his early 30s.

William Thornton, born in what is now the British Virgin Islands and educated in England and Scotland, immigrated to the U.S. in 1787, became a citizen the next year but soon returned to his native island. In 1792, he belatedly learned of a competition to design the new country’s congressional home.

He worked “day and night” on the drawings and revised them heavily after he got to Philadelphia (then the capital city), and they immediately caught the eye of President George Washington and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson. The neoclassical design had sections for the House and Senate on each end connected by a domed rotunda with an impressive portico. Washington loved its “grandeur, simplicity and convenience” and formally approved a further modified design, with a floor plan designed by Stephen Hallet, the only trained architect to have entered the competition, in July 1793.

Detail of the Tortola scheme. Architect: William Thornton. Prints and Photographs Division.

Detail of the Tortola scheme. Architect: William Thornton. Prints and Photographs Division.The District of Columbia was a swampy backwater in the 1790s and what is now known as Capitol Hill was a wooded rise, filled with scrub oak. There was no building on the continent that looked remotely like their ambitions.

During construction — which has only seemed to pause during the past 200 years, as the building and grounds are constantly evolving — things changed. The Capitol expanded with the nation, growing from the original bid for a modest 15-room brick building into a complex covering 1.5 million square feet with more than 600 rooms and miles of hallways over a ground area of about 4 acres. The cast-iron dome weighs 8.9 million pounds. It is also a museum of American art and history, with gorgeous tile floors, delicate friezes and masterpieces of painting and statuary.

That construction was like many a Washington project — filled with competing political visions, never-finished ideas, delays, conflicts of interest, hirings, firings, rehirings, egos, a libel suit, cost overruns, disasters and, somehow, stunning success.

“It is America’s greatest building; it is in the monumental and classical tradition of Western art and is among the great symbols of Western civilization,” writes Arthur Ross of The Institute of Classical Architecture & Art in the 2005 foreword to “The United States Capitol: Its Architecture and Decoration.”

The Library preserves a significant chunk of that history, with personal papers, architectural renderings, plans and drawings. These include not only the papers of Washington and Jefferson, whose architectural ideals shaped the building’s concept, but also an archive of work by Benjamin Henry Latrobe, the second architect of the Capitol and responsible for much of its neoclassical design; an archive of Charles Bulfinch, Latrobe’s successor as architect of the Capitol; and an idea book of Constantino Brumidi, whose murals, friezes and frescoes, including the “The Apotheosis of Washington,” fill the building.

The oldest known photograph of the Capitol building, 1846, with its copper-sheathed wooden dome. Photo: John Plumbe. Prints and Photographs Division.

The oldest known photograph of the Capitol building, 1846, with its copper-sheathed wooden dome. Photo: John Plumbe. Prints and Photographs Division.There are also the papers of Frederick Law Olmsted, the nation’s preeminent landscape architect of the 19th century who reshaped the Capitol’s wooded grounds into a marvel of beauty; and the papers of Montgomery C. Meigs, a prominent Civil War officer and engineer who oversaw key additions to the Capitol, including its stunning dome. (The Architect of the Capitol, as you might expect, also as vast history of the building.)

These collections are buttressed by foundational items such as the 1792 newspaper ad announcing the design competition that drew Thornton’s entry as well as Thornton’s original “Tortola Scheme”; Washington’s original letter to the commission endorsing it; Pierre L’Enfant’s original 1791 plan of Washington with the site of the Capitol Building; and the first photograph of the Capitol, taken in 1846.

These combine to tell an unlikely story, for there were few architects and craftsmen in the young nation, none of the original commissioners overseeing the project had qualifications for the work and there was little funding. Thornton and Latrobe, the first two architects of the Capitol, insulted one another so viciously that Latrobe successfully sued Thornton for libel.

“Few buildings have begun under less favorable circumstance, and fewer still enjoy greater architectural success,” writes William C. Allen in “History of the United States Capitol,” a 2001 government publication.

The eye of the Rotunda. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.

The eye of the Rotunda. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division. Principal construction dragged on for decades. The Capitol was burned by the British in 1814, and another fire in 1851 destroyed much of the Library of Congress (then housed in the Capitol). Dozens of workaday ovens were installed during the Civil War to help feed Union troops who were camped nearby. It was only that war that brought an end to using enslaved workers to build the “temple to democracy.”

One of those workers was Philip Reid, an enslaved man who in 1860 played a key role in casting the Statue of Freedom that crowns the dome. Then in his 40s, he was a free man by the time it was raised in 1863.

The Statue of Freedom, down from its spot atop the Capitol Dome for repairs. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Statue of Freedom, down from its spot atop the Capitol Dome for repairs. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.From the statue’s vantage point nearly 300 feet above the city, workers who put it in place would have seen the Anacostia and Potomac rivers slicing around L’Enfant’s planned city and the expanse of the country spreading beyond the western horizon.

So much of the nation’s history had yet to be written, and the building that would become its symbol was, like the rest of the nation, still growing.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

September 9, 2024

Laundromats, Refugee Camps and Other LOC Literacy Winners

The Library’s 2024 Literacy Awards recognized four top honorees from around the world for their work in promoting a love of reading, language preservation and literacy lessons in refugee camps, Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden said yesterday on International Literacy Day.

The year’s awards recognize work in six countries and in more than a dozen spots across the United States, showcasing the Library’s annual recognition of literacy efforts. In addition to the four top prizes, worth a combined $350,000, another 20 organizations were recognized for their work with smaller awards.

“I am encouraged by the work that this year’s winners and honorees have accomplished in helping people of all ages not only learn to read in a primary or secondary language, but also in inspiring communities to enjoy the practice of reading,” Hayden said.

The LaundryCares Foundation received the Literacy Awards top prize. Photo: LaundryCares Foundation.

The LaundryCares Foundation received the Literacy Awards top prize. Photo: LaundryCares Foundation.The program’s $150,000 top award, the David M. Rubenstein Prize, went to the LaundryCares Foundation, an Illinois-based non-profit that has transformed hundreds of laundromats across the United States into learning spaces that encourage reading for children and families.

“This prestigious distinction will be a game changer for us and help us reach more children through our everyday spaces and places,” said Liz McChesney, the early childhood partnerships and community engagement director of LaundryCares.

The foundation was established in 2006 by the Coin Laundry Association in the wake of Hurricane Katrina as a means of helping under-served communities in the New Orleans area, in particular with providing spaces for children to read and learn. The effort now has some 250 laundromats across the country participating in their Family Read, Play, & Learn program. McChesney, the former director of children’s services at the Chicago Public Library, co-authored an article (“Soap, Suds, and Stories”) about the program in a journal of the American Library Association in 2020.

On the other side of the world in New Zealand, Te Rūnanga Nui o Ngā Kura Kaupapa Māori Inc., a network of schools, was awarded the inaugural $100,000 Kislak Family Foundation Prize for their work in preserving and promoting the Māori language, which was recently under the threat of extinction.

“This recognition underscores the transformative power of indigenous language, not just as a tool for education and literacy but as a means of intergenerational transmission that ensures our culture thrives across generations,” said Hohepa Campbell, chief executive officer of TRNKKM. TRNKKM’s work was recognized for having an outsized impact on Native language revitalization efforts in indigenous communities worldwide.

Just outside D.C., We Need Diverse Books in Bethesda, Maryland, received the $50,000 American Prize for supporting authors and illustrators with diverse backgrounds and helping them get their books published. “Imagine a world in which all children can see themselves in the pages of a book,” reads the front page of their website, summarizing their mission.

Finally, the Alsama Project in Beirut, Lebanon, received the $50,000 International Prize for implementing an effective curriculum that condenses 12 years of standard schooling into half that time and empowering Syrian refugee youth who are often left out of Lebanese schools due to low literacy skills.

The Library’s Literacy Awards Program, established in 2013 with Rubenstein’s support (and bolstered by the Kislak Family Foundation in 2023) has awarded 223 prizes, totaling more than $3.8 million. More than 200 organizations from 40 countries have been recognized for their work.

Nonprofit organizations, schools, libraries, and literacy initiatives from across the country and around the world apply for the awards every January. The 15-member Literacy Awards Advisory Board then reviews the applications before Hayden makes the final decisions.

This year’s other international honorees were in Afghanistan, Norway, Pakistan and Poland. There were 14 other U.S. honorees, ranging from locally focused efforts to nationwide campaigns.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

September 6, 2024

Postcards from America

This is a guest post by Helena Zinkham, chief of the Prints and Photographs Division. It also appears in the July-August issue of Library of Congress Magazine.

Greetings from Washington, D.C.!

And from Gordon, Nebraska; Black River Falls, Wisconsin; San Francisco, California; and countless other big cities and tiny hamlets spread across the vastness of the United States.

The Library’s Prints and Photographs Division recently placed online more than 8,000 “real photo” postcards from the early 1900s — cards that preserve images of life as it existed in turn-of-the-century America.

Let’s hope he doesn’t see a squirrel…a 1911 gag postcard photo. Prints and Photographs Division.

Let’s hope he doesn’t see a squirrel…a 1911 gag postcard photo. Prints and Photographs Division.The production and use of postcards exploded in the United States after a federal law, passed in 1907, allowed for messages to be written on the backs of the cards along with the addresses. Previously, postcards were widely used, but messages could only be added to the fronts of cards, which detracted from the images.

At a time when relatively few households had a telephone, postcards provided quick and convenient communication. Many people also collected cards as souvenirs in albums.

Large companies fed this new market with millions of cards featuring popular landmarks and tourist sites, humorous pictures, holiday greetings and advertisements. Local photographers participated in the craze by printing their negatives on a photographic card stock, typically 31/2 by 51/2 inches in size. The Library’s postcard holdings are vast.

Dome Rock in Gering, Nebraska, in 1908. Photo: S.D. Buther and Son. Prints and Photographs Division.

Dome Rock in Gering, Nebraska, in 1908. Photo: S.D. Buther and Son. Prints and Photographs Division.Their images show an America hard at work and play, and the country’s innate sense of humor. In South Dakota, men top off a giant haystack. A boy rides an enormous prize rooster at the Minnesota State Fair. In Olustee, Oklahoma, a couple poses in the back seat of their Overland automobile, their dog in the driver’s seat, paws on wheel.

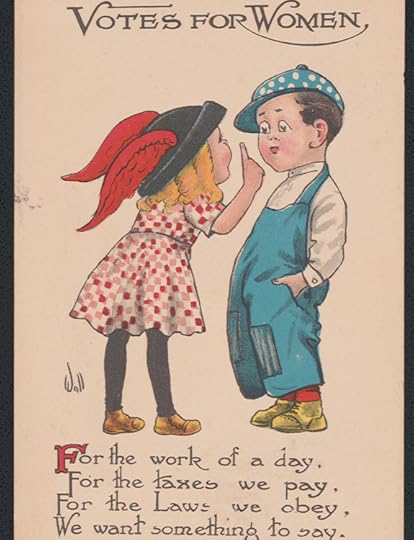

And they show an America moving ahead into a new, modern era: A biplane flies down Main Street in Mayville, Wisconsin; an 1913 illustrated card calls for votes for women.

A 1913 postcard advocating for womens right to vote. Prints and Photographs Division.

A 1913 postcard advocating for womens right to vote. Prints and Photographs Division.When photographers expected large sales for a card, they could deposit a copy of the card for copyright protection. The Prints and Photographs Division now preserves thousands of those copyright deposit postcards.

The Collections Digitization Division scanned all the cards in 2023, fronts and backs — now all waiting online to be explored.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

September 4, 2024

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Finding a Voice in America

Viet Thanh Nguyen fled Vietnam as a child, escaping Saigon with his family the day before the capital city fell to communist forces. They went to military bases in the Philippines and Guam, then lived in Pennsylvania for a few years before finally settling in San Jose, California, where he discovered the American dream was complicated.

By the time he was in college, he explained at the National Book Festival last Saturday, he was reading James Baldwin and Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison, and he became acutely aware of the ties between American imperialism abroad and its domestic racism.

His mother, who had survived internal displacement, war and colonialism in Vietnam and then remade herself once more in the United States, could no longer handle the stress. In his late teens, she was hospitalized with mental illness. It was all very disorienting.

“I was raised in a very Vietnamese household in a Vietnamese refugee community and my parents told me, ‘You are 100 percent Vietnamese,” he told C-Span during the festival. “At the same time, I was constantly being exposed to American culture, so I felt like an American spying on these Vietnamese people.”

That dual identity, of seeing both the peril and the promise of the United States as a world power – and seeing the pain within a family that was doing well in its new home – is the driving force behind his literary work, most notably in his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, “The Sympathizer,” now an HBO series.

“It’s been a long struggle to wrestle with the idea of the United States, its mythology, the American dream, which is so seductive to so many immigrants and refugees who come here,” he said during the Celebrating James Baldwin’s Centennial panel at the NBF. “And to be able to root out American mythology from within oneself is extremely difficult to do.”

Viet Thanh Nguyen. Photo: Hopper Stone.

Viet Thanh Nguyen. Photo: Hopper Stone.Nguyen, 53, a MacArthur fellow and the Aerol Arnold chair of English at the University of Southern California, was onstage with novelist and professor Ayana Mathis. NPR’s Eric Deggans moderated the hourlong discussion, which covered Baldwin’s lasting influence on American society, literature, the LGBTQ+ movement and civil rights activism.

Nguyen focused on Baldwin’s international perspective during his time onstage, but in a separate interview he spoke about the role that libraries and reading played early on. After the upheaval of fleeing the war, his parents worked long days at their small grocery store. They were saving to educate their children, but they “struggled tremendously” and their long absences while working left young Nguyen adrift.

His “salvation,” as he puts it? The San Jose Public Library.

“It was the place where I went for stories and entertainment and fantasies and escape because I couldn’t afford to buy any books myself,” he said. “These books were free and they connected me to the world — a world beyond my parents’ grocery store, beyond San Jose — a world of books that were not written for me … but those books did connect with me and gave me the idea I could be a writer.”

From the beginning, he set a high standard of both academic and literary success. He figured that it would take him at least 20 years to learn how to write the books the way he wanted, full of history and social critique and irony and interconnected storylines that tied all these themes together. He attended a private high school and went to U.C. Berkeley, where he obtained two degrees and then a Ph.D. in English.

He had not read many books by Black American authors until university, but he was then greatly impressed by Baldwin and many others. He was so taken with Ellison’s “Invisible Man” that he would later name his first child Ellison and use the opening imagery of “Invisible Man” as the inspiration for the first page of “The Sympathizer.” (The Library preserves Ellison’s papers, including his personal library.)

“Invisible Man” starts like this: “I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids — and I might even be said to possess a mind.”

The first lines of Nguyen’s “The Sympathizer” are a clear homage: “I am a spy, a spook, a man of two faces. Perhaps not surprisingly, I am a man of two minds. I am not some misunderstood mutant from a comic book or a horror movie, although some have treated me as such.”

“The Sympathizer,” some two decades in the making, drew on Nguyen’s lived experiences, of what had happened to his home country and his family, but he was also drawing energy and parallels from Black American authors of the mid-20th century who were taking on political and social themes, such as Wright’s “Native Son,” Baldwin’s “Go Tell It on the Mountain” and Ann Petry’s “The Street.”

In his new life in America, Vietnam “wasn’t even a subject” in school, he said in a 2022 PBS interview, and the American culture he was exposed to — Hollywood films and books at the library — viewed Vietnamese people most often in “deeply racist and sexist ways” and “that was shocking for me.”

“I was looking for role models, and I was finding that in Asian American literature,” he told the NBF crowd. “But the other tradition that was really powerful for me was Black writers, Black literature. … It was really important for me to think through, ‘What does it mean to be a writer of color?’ Black writers are offering these arguments that they’re putting forth about the relative relationship of politics, putting literature into art … and it was a very fundamental debate. I think it shaped a lot of people and we’re still talking about that to a certain extent today.”

Since “Sympathizer” marked his literary debut nine years ago, Nguyen has published a second volume extending the story (and is working on the third book in the trilogy), a book of short stories, a nonfiction book on the Vietnam War, two children’s picture books and, most recently, a memoir. It’s called “A Man of Two Faces,” again emphasizing that sense of duality.

He lives with his family in Los Angeles and is delighted that there is a “tiny neighborhood library that’s so beautiful” just three blocks from their house. In a city of cars and freeways, it’s an easy walk.

His face lights up when he remembers this: His young daughter Simone went there on a recent day and saw his children’s book, “Simone,” prominently featured in the front window. She proudly took it to the librarian at the front desk, holding out the cover.

“‘That’s my name and my father wrote this book,’” he recounts her saying. Delighted, smiling, he adds: “And for me, that just brought everything home.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 30, 2024

Kelsey Beeghly, Library’s Albert Einstein Fellow

Kelsey Beeghly, a science curriculum and assessment coordinator from Orlando, Florida, was the Library’s 2023–24 Albert Einstein distinguished educator fellow.

Tell us about your background.

I grew up in central Florida and earned a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Central Florida.

While at UCF, I taught physics to my fellow undergraduate students. Through this part-time job, I discovered how much I love teaching science and decided to become a science teacher.

After graduation, I moved to Brooklyn, New York, where I taught advanced placement environmental science, biology and chemistry for two years while earning my master’s degree in teaching with a dual certification in secondary science and special education.

My journey brought me back home to central Florida, where I transitioned to teaching life and physical science at the middle school level.

Then, I went back to UCF to earn my Ph.D. in science education. For three years, I taught science methods and content courses to undergraduates in UCF’s teacher education school while completing coursework and serving as a research assistant on a grant to support English learner education. Simultaneously, I worked as a high school administrator, leading curriculum and assessment practices.

What inspired you to come to the Library as an Einstein fellow?

When I discovered the Department of Energy’s Albert Einstein Distinguished Educator Fellowship opportunity, which places STEM educators in federal agencies and congressional offices, I was fascinated.

My teaching experiences, as well as my Ph.D. program, alerted me to many of the systemic issues facing teachers and students in this country. Where better to learn more than the nation’s capital?

Immediately after meeting with the Professional Learning and Outreach Initiatives office last year, I knew the Library was the right fit for my fellowship placement. The team’s passion for use of primary sources to promote deeper understanding of the nature of science — what science is, how it works and how scientists operate within society — strongly resonated with me.

What resources at the Library have captivated you?

First, Chronicling America — I loved exploring its historical newspapers using every search term that popped into my head. I also loved reading “The Tradition of Science,” a compilation of landmark items that the Library holds from the history of Western science.

I really enjoyed searching through photographs in the digital collections, especially for curating a “Scientists and Inventors” free to use and reuse set. The Library has so many interesting pictures that represent the diversity of science but also shed light on societal norms that impacted who could participate in science for much of our nation’s history — the effects of which can be observed in STEM engagement today.

How will your experience this year affect your approach to education?

I have learned about so many federal resources freely available to educators, including the Library’s resources, and now see the Library itself as a huge fountain of knowledge.

I also have an appreciation for and awareness of all the possibilities for conducting research using the Library’s digitized collections from anywhere in the world. Any time I am seeking a historical perspective on an issue from now on, I will consult the Library’s website and its experts and encourage others to do the same.

What would you like STEM educators to know about the Library?

STEM educators need to know about all of the amazing things the Library has to offer. My own past teaching in grades 6–12 and of preservice teachers would have greatly benefited from incorporating the Library’s primary sources.

I’m very confident that every topic taught in a science classroom can be made more engaging by including a piece of history related to it, the people involved with it and its impact on society.

STEM educators could start with the Teaching with the Library blog, where I have shared some of my discoveries. Next, they might consult primary source sets available a the teacher’s page, then use the Library’s Ask a Librarian service and research guides to support themselves and their students in exploring topics.

I also want STEM educators to know about the science that takes place within the Library‘s Preservation Research and Testing Division. I’ve met the division’s scientists and learned about some incredible projects I plan to feature in my upcoming “Doing Science” series on the blog.

Teachers can bring these ideas into their classrooms and encourage students to investigate careers that combine a love of science with a passion for art or history.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 27, 2024

James McBride at the NBF: “Love is the greatest … novel ever written.”

James McBride, winner of the Library’s 2024 Prize for American Fiction, took the main stage at the National Book Festival last weekend, delighting a rapturous crowd with anecdotes and observations about his bestselling books and his remarkable writing career.

A Washington Post journalist early on, and a professional musician for years, McBride did not write his first book until his mid-30s — and that was the “The Color of Water,” a memoir that has sold millions of copies all over the world.

“I like people, I listen to people,” he said at Saturday’s event. “… and I happen to look to the kindness in people. And when you look to the kindness in people, you see their depth.”

He pulled a small notebook from a pocket to show he always carries one to jot down names, ideas and quotes he overhears in everyday conversation, which he then uses or approximates in his fiction.

“People are just handing me money when they talk,” he said.

It was that kind of wry remark, delivered with perfect comic timing, that delighted the audience through his nearly hourlong presentation. Smart, insightful and thoughtful, McBride got his biggest laughs when being down to earth. When asked by moderator Michel Martin of NPR how he was handling being the Fiction Prize winner and the festival’s marquee attraction, McBride — seated, with his legs crossed, on a raised stage in front of nearly 3,000 people — looked down and said, “Well, I wish I’d worn some longer socks so that people can’t see my ankles.”

A 66-year-old native New Yorker and a distinguished writer-in-residence at New York University, McBride went to New York City public schools, studied music composition at Oberlin Conservatory of Music and got his master’s degree in journalism at Columbia University.

After an impressive music career — he composed songs for Anita Baker and toured as a saxophone player for jazz singer Jimmy Scott — the success of “Water” led him to pursue writing full time. He has written eight books, most of them fiction. “The Good Lord Bird,” winner of the 2013 National Book Award for Fiction, was a freewheeling retelling of John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859. His most recent novel, “The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store,” set in the Black section of a small Pennsylvania town in the 1930s, was awarded the 2023 Kirkus Prize for Fiction and named the 2023 Book of the Year by Barnes & Noble. His previous novel, “Deacon King Kong,” was an Oprah’s Book Club selection.

He was awarded the National Humanities Medal by President Barack Obama in 2015 for “for humanizing the complexities of discussing race in America.”

His books have “have pierced through American psyche and culture,” said Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden, introducing him on Saturday. “He connects diverse people in his thought-provoking and poignant art, taking us on an emotional joyride in his stories.”

An overflow crowd listens to James McBride at the National Book Festival. Photo: Shawn Miller.

An overflow crowd listens to James McBride at the National Book Festival. Photo: Shawn Miller.“The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store” is vintage McBride, telling a small-town story about people whose actions are sometimes questionable but whose humanity is not.

The narrative centers around a modest store run by a Jewish woman in the Black community called Chicken Hill on the outskirts of Pottstown, Pennsylvania, in the 1930s. Hardworking Black and Jewish people, ignored or insulted by the town’s white founders and leaders, get by as best they can.

Community life takes a turn when a 12-year-old orphaned, nearly deaf Black boy is blamed for assaulting a white doctor who is, as everyone knows, a leader in the local Ku Klux Klan. The child is sent to a horrific asylum for the mentally ill, drawing the cast of characters together.

The book grew from McBride’s teenage experiences working as a summer counselor at a camp for neuro-divergent children. He learned, he said on Saturday, that “disabled” people were actually marvelous observers of life around them, as nearly everyone discounted and ignored them.

“It changed my life,” he said of the experience, adding later: “If your job is to find the humanity in people, look to the differently abled.”

McBride, as he wrote about so poignantly in his now-classic memoir, was mostly raised by his mother, a Jewish woman who passed herself off as “light skinned” in their Black neighborhood. As a child, when he asked her what color God was, she replied, “the color of water,” giving the book its title and McBride his concept of universal acceptance.

“Love is the greatest,” he said in closing. “It’s the greatest novel ever written.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 23, 2024

Riding a Wave with Kazu Kibuishi

This weekend at the Library’s National Book Festival, fans of Kazu Kibuishi’s epic Amulet series will have a chance to hear him read from his ninth and final book in the series, “Waverider” and talk about how he created the immersive world where his graphic novels are set.

Maya Shibayama, one of my favorite sixth graders, is a huge fan of the Amulet series and is great at explaining how captivating the series can be.

“I was so excited when Book 9 came out,” she said. “My mom wouldn’t give it to me until spring break since she knew I wouldn’t sleep or do homework until I was done reading it.”

Kibuishi will read a selection from “Waverider” and then will join fellow graphic novelist Vera Brosgol to talk about the characters, worlds and moods they create for their books in a panel called “I Built This World, Come Visit!” Afterwards, he will sign copies of his books.

If you miss him on Saturday, look for a recording of his conversation with Vera in the coming days. It will be on the Library’s website and YouTube channel.

Maya and I wrote a few questions for Kazu, and he was nice enough to answer them for us.

Where do you get such cool ideas? How long does it take for you to write a new story?

I feel like most artists have an abundance of cool ideas! The difficult thing is choosing which cool ideas to spend a lot of time working on to turn into a book. Deciding what to work on is often the toughest creative decision I have to face.

Are the characters in Amulet inspired by real people you know?

Very few of the characters are inspired by real people, but there are a handful of side characters that are definitely based on my friends. Some of the characters definitely have my mannerisms, which I suppose can be expected.

Did you always know how you wanted the Amulet series to end? If not, when did you decide what the ending would be?

I had the ending of the series in mind from the start. It’s one of the things that has remained consistent throughout.

When you are creating a new story, what comes first for you – the visual elements or the plot?

Both. I think of images that tell a story, so the images are much like words in my mind.

What advice would you give to kids who wants to write or illustrate books or graphic novels of their own?

Just get started and don’t stop. It takes a long time to get used to making books, and the more you do it, the better you get. If you can become comfortable with the process of improving, there’s no limit to where that approach can take you.

What is your favorite food?

My favorite food is Japanese-style Western food (Yoshoku). This includes stewed hamburger steak, chicken or pork katsu curry. I also love noodles like ramen, udon, soba, or somen.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 22, 2024

Catching a “Curveball” with Pablo Cartaya

Pablo Cartaya’s novels touch on themes of family, culture and community, so it was no surprise when my 11-year-old daughter Ellie connected with the young characters of his latest book, “Curveball.”

He’ll be at the National Book Festival this Saturday, reading from his book “Tina Cocolina: Queen of the Cupcakes,” and talking on a panel, “Sports and Why We Love Them: Graphic Novels with Pablo Cartaya and Hena Khan. Pablo and Hena will also sign copies of their books.

If you can’t attend, their conversation will be posted in a few days on the Library’s website and YouTube channel.

Ellie and I came up with some questions for Pablo about “Curveball,” as she loved the book.

“I really felt a connection to Elena and the pressure she felt to always work harder to be the best baseball player on the team,” Ellie said. “I don’t play baseball, but sometimes I get tired of the things I love because I want to be perfect at them … and I’m glad that Elena learned how fun it is to use her imagination!”

Here are our questions and Pablo’s answers.

What inspired you to write this story and what do you hope your readers take away from the book?

Have you ever felt pressure to perform? Have you ever felt like you were going to let someone you care about (a parent, a teacher, a coach) down if you didn’t succeed? When I was a kid, I felt that a lot. I played many sports growing up (basketball, soccer and baseball specifically) and my dad was the coach on many of my teams. My dad was an Olympian representing his country of Cuba, my dad is in the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame, my dad was recruited by a Major League Baseball team. That casts a really big shadow. And he was my coach! I was a pretty good athlete and even the leading scorer on a few of my teams, but I always worried that I was never going to live up to my dad’s success. It wasn’t anything my dad was doing, it was more the way I was thinking about that pressure. Then one day, I was with my grandfather after a baseball game in which I missed a ground ball and the opposing team scored a run and won the game. I was feeling really bummed. My grandfather told me, “You don’t look like you’re having fun out there, mijo.” And it was so hard to admit that I wasn’t having fun but my grandfather told me that I should tell my dad how I felt. So I did. What my dad said surprised me. He said, “You have to do things for you, not for anybody else.” I never realized he just wanted me to love to play. So when I was writing “Curveball” I thought about that experience.

How did you work with illustrator Miguel Díaz Rivas to create the illustrations that bring this graphic novel to life?

The incredible team at Disney asked me to write the script first and, well, to be perfectly honest, I was terrified. Yes, even after writing a whole bunch of books, writers still get scared to write. The reason I was so nervous was that I had never written a graphic novel before! But that’s the great thing about teams, you see, you work together to achieve a common goal. The team at Disney, led by my incredible editor, sent me guidelines and tips and emails of encouragement and before I knew it, I had written my very first graphic novel script! And when the script was sent over to Miguel, he really knocked it out of the park. Teamwork makes the dream work!

How is it different writing a graphic novel versus a chapter book?

The writer of the graphic novel (if they are not also the illustrator) is to give direction to the illustrator about how you want the story to unfold. It’s a collaboration between two art forms (creative writing and visual art) to tell a story. You have to give enough information to the illustrator to allow them to interpret the story. There’s a lot of trust involved and it was a great deal of fun. When I write a chapter book, the process is a little different. You have to rely on your storytelling to engage a reader. That has its own challenges, but like a graphic novel, when you do it well and a reader connects with the story you wrote, it’s an awesome feeling.

What do you think happened for after the book ended? Is there an epilogue for Elena?

I’ve written epilogues in other novels but hadn’t really thought about one for Elena.

What advice would you give to kids who wants to write a book of their own?

Remember three very important things: 1. Your voice matters. 2. Read as much as you can. 3. Revision is your friend.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers