Library of Congress's Blog, page 14

June 10, 2024

Treasures Gallery: The AIDS Quilt

This is a guest post by Charles Hosale, an archivist in the American Folklife Center. It also appears in the May-June issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, which is devoted to the June opening the David M. Rubenstein Treasures Gallery.

The AIDS Memorial Quilt, regarded as the largest folk art project ever created, is like a chorus. Individual voices have been stitched together into a monumental whole, but that whole cannot exist without each part.

The quilt is composed of more than 50,000 panels, each one memorializing a life or lives lost to AIDS. Each panel is 3 feet by 6 feet, roughly the size of a human grave. Panels were combined by dedicated volunteers into 12-by-12-foot blocks that are displayed together to form the quilt.

Quilt block 1333 contains panels for eight men. One of those panels was made in 1989 by Steve Horwitz in memory of his partner, David Keisacker. Like other contributors, Horwitz sent photographs and a written memorial for Keisacker to the AIDS Quilt archive, along with the panel. The panel and these documents combine to form a moving glimpse of Horwitz’s and Keisacker’s lives — their submission joins tens of thousands of others to form a beautiful and devastating chorus. The Library’s American Folklife Center has held the quilt’s archival collections since 2019.

The AIDS Quilt displayed on the National Mall. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.

The AIDS Quilt displayed on the National Mall. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.Block 1333 is one of the thousands displayed at events across the world, including the displays on the National Mall. While displays continue today, the last full display of the quilt was on the Mall in 1996 — the quilt has grown too large to be displayed there all at once.

These exhibitions starkly show the scale of loss the United States and the world continue to experience. The undeniable magnitude of the quilt and the significance of each story stitched into it celebrate the memory of AIDS victims and demand justice for their suffering.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

June 5, 2024

Treasures Gallery: Spider-Man’s Origin Story

—This is a guest post by Sara Duke, a librarian in the Prints and Photographs Division. It also appears in the May-June issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, which is devoted to the June opening the David M. Rubenstein Treasures Gallery.

In 2008, the Library became even more aware that “with great power there must also come great responsibility!” The Library received the 24 original drawings by Steve Ditko for Amazing Fantasy No. 15, including the Spider-Man origin story.

The intact stories permit artists, historians and fans an opportunity to study the art, the nuances between penciling and inking and the use of opaque white to alter images and text. They also benefit from the evidence of artist and writer interaction. The real super hero of this acquisition story is the anonymous donor, who kept the art together and donated this priceless treasure to the Library for generations to enjoy.

With writer Stan Lee, Ditko created this classic of the comic book’s “Silver Age” (1956-1969), an era of superheroes’ resurgence in the mainstream comic book industry, following the genre’s decline after World War II. In this August 1962 issue, Ditko’s clean, eye-catching design pulls the viewer into the scene and sets the suspenseful tone for the eleven-page story.

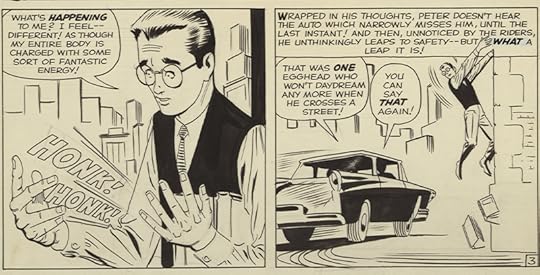

Two panels from the Spider-Man origin story in Amazing Fantasy. Image: Courtesy of Marvel. Prints and Photographs Division.

Two panels from the Spider-Man origin story in Amazing Fantasy. Image: Courtesy of Marvel. Prints and Photographs Division.Some changes in the Spider-Man! art occurred after inking and remain visible on the art but are invisible in the published version. In the lower right panel on the third page (shown above), writer Stan Lee asks Ditko to alter both the appearance of a vehicle and its passengers. Lee wrote, “Steve. Make this a covered sedan — no arms hanging. Don’t imply wild reckless driving. S.” The altered roof support is not visible in the published version.

On the sixth page, Peter Parker dresses in the costume he has made, and for the first-time readers can see the intricate webbing and fussy cape-like filigree under Spider-Man’s arms. Readers learn that the bookish Peter, with his knowledge of science, has invented web shooters and experimented with their use. It is not until a major change occurs at the end of the story that Parker becomes a super hero and learns the lessons of responsibility.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

June 3, 2024

Pride Month: Transcribe Walt Whitman?

Volunteers have been working over the past five years to transcribe the Library’s manuscripts of Walt Whitman, one of the nation’s most iconic poets, from three major collections. Can you help proofread the final 4,000 pages?

This June, the Library is hoping you’ll do just that as we celebrate Pride month.

Through By the People, the Library’s online crowdsourced transcription program, you can transcribe and review historical texts across the Library’s collections, from Clara Barton’s diaries to Leonard Bernstein’s papers. Completed transcriptions are published on our website to enhance accessibility and enable keyword search.

Whitman — the author of letters, notes, essays, memoir materials, and poetry, including “Song of Myself,” “O Captain, My Captain!” and many other poems compiled in his momentous 19th-century masterpiece “Leaves of Grass” — is one of voices that helped define the national character.

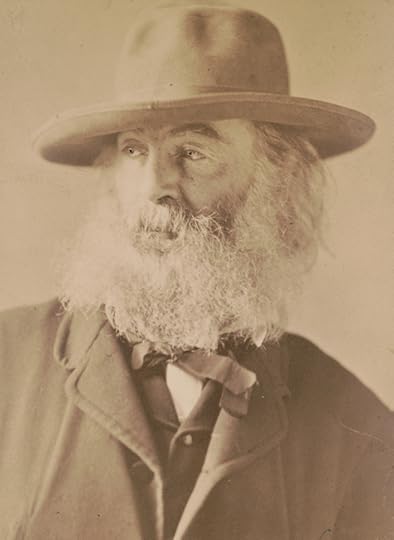

Walt Whitman in 1869. Photo: William Kurtz. Prints and Photographs Division.

Walt Whitman in 1869. Photo: William Kurtz. Prints and Photographs Division.The Library holds the largest number of Whitman materials in the world. Beginning with Whitman’s bicentennial birthday celebration in 2019, more than 3,700 volunteers have transcribed some 33,500 items, mostly handwritten pages, into typed text. Thanks to their work, anyone with access to the Library’s website from anywhere in the world can use keyword searches to help their research in the Library’s digital presentations of the Whitman collections. The transcriptions also enhance online access for those who need screen readers to understand the handwritten images.

This Pride month, again in Whitman’s honor, we’re looking to wrap up the project by encouraging volunteers to proofread the last 4,000 items of transcribed material. It’s the last, crucial step before transcriptions can be published to the website.

What would you be reviewing?

The papers that need work include correspondence, family papers and materials related to the production of Whitman’s books. But the vast majority fall into the varied and fascinating category of “miscellany” from the Charles E. Feinberg Collection of Whitman’s papers. Spanning from 1834 to 1918, these include autographs, correspondence, calling cards, programs, invitations, scrapbooks, railroad and ferry tickets, labels, wrappers and financial papers.

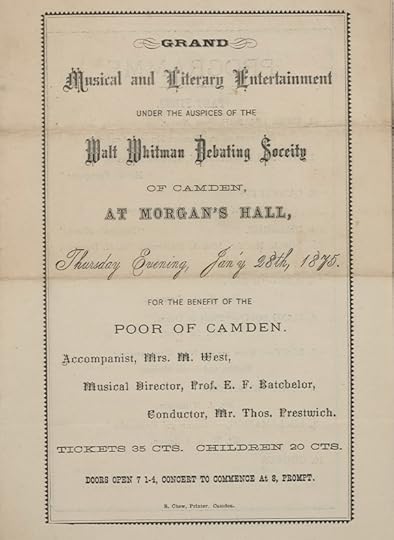

A program of the Walt Whitman Debating Society. Manuscript Division.

A program of the Walt Whitman Debating Society. Manuscript Division.These bits and pieces offer evidence about Whitman’s life and the activities of those who were close to him. There is evidence of his 1850s work in Brooklyn as a carpenter and contractor; his 1862 military passes to visit Army camps; the 1863 Christian Commission certificate for volunteering in Civil War military hospitals; his 1866 appointment for civil service work in the Attorney General’s office in Washington, D.C.; invitations to celebrations of his birthday during his Camden-Philadelphia years; annotated maps indicating travels; a copy of his will; and his sketched design for the Whitman burial vault at Harleigh Cemetery in Camden, New Jersey.

Here’s how you can jump in: Create an account, then explore the Walt Whitman campaign on By the People. Find a page that needs review and check that all the text is captured accurately. If everything is correct, just click “Accept!” If you need to make a few changes, click “Edit,” then save and resubmit the transcription for another volunteer to review. It’s that easy!

Every page you review brings us one step closer to completing this project and meeting our Pride month goal. We also hope you will reflect on the amazing life Whitman led as you encounter his life and words firsthand and contribute to his ongoing legacy.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 31, 2024

It’s a Small(er) World Without the Sherman Brothers

The Oscar-winning songwriter and composer Richard Sherman, whose musical work with his brother was such an essential part of Walt Disney Studios that the company renamed their premier soundstage after them, passed away over the Memorial Day weekend. He was 95. Robert, his brother and songwriter partner, died in 2012.

The pair, prolific since their teenage years in California, wrote the music that helped define the Disney brand during the 1960s and early 1970s. They wrote much, if not all, of the music for “Mary Poppins,” “Winnie the Pooh” and “The Jungle Book,” as well as the studio’s weekly television show.

They also composed what was the most played song in music history, at least until the digital era and streaming services.

“It’s a Small World (After All)” was first composed as the theme music for a ride at Disney’s exhibit at the 1964-65 World’s Fair in New York. The water ride, which took passengers past rows of mechanical dolls from around the globe singing the song, became a fixture at the company’s theme parks and the song played endlessly, as every parkgoer came to know all too well.

“People either want to kill us or kiss us,” Sherman said in an interview with the Library in 2022, when the song was inducted into the National Recording Registry.

Robert and Richard Sherman (l-r) in 2002. Photo: Howard352, Wikimedia Commons.

Robert and Richard Sherman (l-r) in 2002. Photo: Howard352, Wikimedia Commons.Together, the Shermans wrote hits for pop radio, such as “You’re Sixteen” hit for both Johnny Burnette and Ringo Starr; music for films outside of Disney, such as “Chitty Chitty Bang “Tom Sawyer”; and many songs for Broadway.

The pair won two Academy Awards (both for “Mary Poppins”) and three Grammys. They were inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame and were awarded the National Medal of Arts. Songs from many of their productions — “Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious,” “Let’s Go Fly a Kite,” “I Wan’na Be Like You,” “Chim Chim Cher-ee,” “Winnie the Pooh” — became staples for children of the era.

Sherman was in good spirits when I spoke with him by phone in April 2022 for the occasion of “Small World” being inducted into the NRR. He patiently explained how their father, Al, had fled Jewish persecution in what was then the Russian Empire (today, Ukraine), came to the U.S. and had an extremely successful songwriting career, penning hundreds of songs for Tin Pan Alley and for the film industry.

Robert and Richard were born in the 1920s and urged by their father to follow in his footsteps.

It wasn’t all Disney and show tunes, though. During World War II, Robert Sherman was one of the first U.S. troops who entered Dachau, the infamous Nazi death camp. Richard Sherman, two years younger, later served in the military but not overseas during the war.

Later, as the brothers’ fame increased, their relationship deteriorated to the point that they did not speak or socialize except for work. This was a delicate point of the 2009 documentary, “The Boys: The Sherman Brothers’ Story.” Still, the personal sourness did not bleed over into their professional work. The stars who came out to appear in the documentary, all with affectionate anecdotes, included Julie Andrews, Dick Van Dyke, Angela Lansbury and John Landis.

The best part of our 20-minute conversation, perhaps, was when Sherman recounted how easily the pair had written “Small.”

“We didn’t sweat blood over it,” he laughed.

Walt Disney had asked them to compose a song for the company’s exhibit at the World’s Fair, which was part of a tribute to UNICEF. The brothers worked up “Small” and, having no idea that Disney was about to embark on building more theme parks (the company had only one at the time), proposed to give the copyright of the song to UNICEF. It would be a very modest sum, they thought, since the ride would come and go with the fair.

Disney was driving them across the company lot when they proposed this. He was shocked.

Sherman, telling the story: “He stopped the car, turned and said, ‘Don’t you give that away! That’s for your grandkids! It’ll put them through college!’ ”

They kept the copyright and Disney knew his business. Out of all their major hits? “It’s our biggest copyright by far,” Sherman mused, more than half a century later.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 28, 2024

Treasures Gallery: What Did Lincoln Have in His Pockets the Night of His Assassination?

—This is a guest post by Mark Dimunation, former chief of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division. It also appears in the May-June issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, which is devoted to the June opening the David M. Rubenstein Treasures Gallery.

Soon after Abraham Lincoln was shot by John Wilkes Booth on April 14, 1865, at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., he was carried across the street to a boarding house. At 7:22 the next morning, the 16th president of the United States took his last breath.

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton is reported to have said, “Now he belongs to the ages.” A lock of Lincoln’s hair was cut at the request of his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln.

Upon Lincoln’s death, his son, Robert Todd Lincoln, was given the contents of the president’s pockets. It was, for the most part, a gathering of the ordinary and everyday: two pairs of eyeglasses; a chamois lens polisher; an ivory and silver pocketknife; a large white Irish linen handkerchief (slightly used) with “A. Lincoln” embroidered in red; a sleeve button with a gold initial “L”; a gold quartz watch fob without a watch; a new silk-lined leather wallet containing a pencil; a Confederate $5 bill; news clippings of unrest in the Confederate Army, emancipation in Missouri and the Union party platform of 1864; and an article on the presidency by John Bright.

Through their association with tragedy, these objects had become relics and were kept in the Lincoln family for more than 70 years. They came to the Library in 1937 as part of a gift from Lincoln’s granddaughter, Mary Lincoln Isham. They joined the Library’s holdings of Lincoln’s papers, forming the nation’s most lasting collection of one of its most revered presidents.

The items were not shown or exhibited until the 1970s. But when they are on display, they always fascinate Library guests. Most of the items in his wallet will be featured in “Collecting Memories: Treasures from the Library of Congress,” the inaugural exhibit of the Library’s new Treasures Gallery, opening June 13. The exhibit will also feature one of Lincoln’s handwritten drafts of the Gettysburg Address, delivered at the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery on Nov. 19, 1863, and an enlarged copy of the only known photo clearly showing him at the ceremony.

In this highly enlarged detail from a much larger photograph, Lincoln is at almost the center of the photograph, hatless, looking down slightly, and probably seated. It is such a small part of the original image that Lincoln was not spotted in it until 1952. Photo: Prints and Photographs Division.

In this highly enlarged detail from a much larger photograph, Lincoln is at almost the center of the photograph, hatless, looking down slightly, and probably seated. It is such a small part of the original image that Lincoln was not spotted in it until 1952. Photo: Prints and Photographs Division.Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 22, 2024

Library Treasures: New Gallery Shows Off Premier Holdings

This piece is adapted from articles in the May-June issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

The Library preserves collective memories representing entire societies as well as intimate records of of important moment and rites of passage in individual lives.

This June, the Library will open “Collecting Memories: Treasures from the Library of Congress,” an exhibition that explores the ways cultures preserve memory. The exhibition is the first in the Library’s new David M. Rubenstein Treasures Gallery.

Rubenstein — a co-executive chairman of the Carlyle Group and chair of the James Madison Council, the Library’s philanthropic support group — announced the project four years ago with a $10 million gift to help create the Library’s first permanent treasures gallery.

Since then, Rubenstein has inspired support from a number of other donors, including the Annenberg Foundation, AARP and many members of the council. Together, these donors helped the Library exceed its promise to Congress to raise $20 million toward a greatly reimagined visitor experience for the nearly 2 million people who visit the Jefferson Building each year.

“Collecting Memories,” the opening exhibit, juxtaposes recordings, moving images, scrolls, diaries, manuscripts, photos, maps, books and more to explore how cultures memorialize the past, assemble knowledge of the known world, create collective histories, recall the events of the day or recount a life.

The goal of the Treasures Gallery is to share the rarest, most interesting or significant items drawn from the more than 178 million items (and counting) in the world’s largest library.

Here is Abraham Lincoln’s reading copy of the Gettysburg Address, neatly handwritten on a browned sheet of Executive Mansion stationery. There are the original, stark designs created by Maya Lin for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Comic book panels drawn for the Spider-Man origin story. Oscar Hammerstein’s working drafts of lyrics for “Do-Re-Mi” from “The Sound of Music” — in early versions, “sew” is not a needle pulling thread but something farmers do with wheat. Clay tablets used by students thousands of years ago. The diary (in Arabic) of Omar Ibn Said, a native of West Africa, who was captured in 1807 and brought to South Carolina as a slave, the only such memoir known to exist. Sigmund Freud’s diaries and notebooks, one with “to remember is to relive” emblazoned in Italian across the front.

Over the next few weeks, we’re showcasing some of the fascinating items featured in the exhibition to give you an online preview. Much of this material can be found in “Collecting Memories: Treasures from the Library of Congress,” the exhibition’s companion volume, and in the May-June issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

“Such things collectively tell the story of all of us: our shared culture, our shared history,” writes Carla Hayden, the Librarian of Congress, in a short essay in the magazine.

Rubenstein, when announcing his initial gift: “I am honored to be a part of this important project to enhance the visitor experience and present the Library’s countless treasures in new and creative ways.”

Want to get started? How about a book depicting, in part, the life of the man who built the Taj Mahal?

This is the Pādishāh‘nāmah, also referred to as the Shāhjahān‘nāmah, one of the most beautiful Persian-language books in the Library. It chronicles the reign of Shah Jahan from 1627 to 1658 in Mughal-era India.

The work contains three parts, the first of which was written during the life of Shah Jahan, the monarch best known today for building the Taj Mahal mausoleum, a monument dedicated to immortalizing his love for his queen, Mumtaz Mahal.

The manuscript highlights the esteemed place the Indian Mughal court accorded Persian language and aesthetics in its literary and artistic traditions, bookmaking and in recording history.

The illustration above depicts the emperor, his crown prince and the royal family celebrating a joyous, nighttime Indian festival on the banks of a river with fireworks, music and feasting.

—Hirad Dinavari, a reference specialist in the African and Middle Eastern Division, contributed the account of the Pādishāh‘nāmah.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 20, 2024

L.A. As You’ve (Probably) Never Seen It

— This is a guest post by Katherine Blood, a librarian in the Prints and Photographs Division. This story also appears in the May-June issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

To retell the history of Los Angeles, artist Barbara Carrasco wove vignette scenes through the flowing tresses of “la Reina de los Ángeles,” based on a portrait of her sister.

Commissioned by the city’s Community Redevelopment Agency, the mural concept stretched from prehistory (the La Brea Tar Pits) to the imagined future (Los Angeles International Airport’s Space Age Theme Building) with subjects ranging from the inspiring to grievous.

Carrasco included such notable figures as folk hero Joaquin Murrieta Carrillo; Juan Francisco Reyes, the city’s first Hispanic and first Black mayor; Bridget “Biddie” Mason, who founded the First African Methodist Episcopal Church; slain journalist Ruben Salazar; and United Farm Workers founders César Chávez and Dolores Huerta.

Historical events included Depression-era breadlines, the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II and the Zoot Suit Riots.

“This was my chance to show what I wish was in the history books,” Carrasco said.

One scene references the whitewashing of David Alfaro Siqueiros’s 1932 mural “América Tropical.” For her own mural, Carrasco was asked to remove elements the CRA deemed controversial. She refused. After decades in storage, the 80-foot mural is now celebrated, and it was displayed in an exhibition, “Sin Censura: A Mural Remembers L.A.,” at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County in 2018–2019 before being acquired for the museum’s permanent collection in 2020. Carrasco’s original graphite design, depicting L.A. history flowing through long tresses of hair, now has a home in the Library.

The original graphite design for the Carrasco’s finished print. Prints and Photographs Division.

The original graphite design for the Carrasco’s finished print. Prints and Photographs Division.Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 16, 2024

Alan Haley, Preservation Specialist

Alan Haley is a preservation specialist in the Conservation Division.

Tell us about your background.

I was born and raised in New Hampshire and attended the University of New Hampshire for my undergraduate and graduate degrees.

Early on, I thought I was destined to be a math major, like my mom. It took me only one semester of college calculus, though, to sour on the idea. I declared a double major in Spanish and Greek because I liked the interactive dynamic of foreign-language classes. I went on to earn an M.A. in Spanish literature and linguistics, then taught Spanish-language classes at the university for several years.

Ready to try something different, I eventually earned a master craftsman’s certification in bookbinding at the North Bennet Street School in Boston. The school encourages students in their second year to seek further training. I applied for a rare book conservation internship at the Library and was accepted in September 1993. I’ve been here ever since.

Describe your work at the Library.

My responsibilities at the Library have morphed over time, but I have been de facto coordinator of the digitization preparation workflow in the Conservation Division for some years now. An amazing team of conservators prepares special collections materials to go under the camera, providing access to their content for Library patrons and the world at large. It is an unbelievable privilege to be part of this program.

What are some of your standout projects?

Working with our incomparable collections so many years makes it hard to choose a standout conservation treatment, and working alongside our conservators who excel in their different specialties is humbling.

Treating the original print transcript of the 1841 Amistad trial was memorable, as was treating the Boulder Dam photo album, which documents the dam’s construction in the 1930s. Last October, I worked on a Chinese scroll from around 600 A.D., the oldest artifact I have ever treated.

Every day brings a new surprise. Perhaps most impactful for me have been the preservation outreach assignments I have undertaken at the Library’s behest to advise on preservation of cultural heritage materials.

The assignments are always challenging, but the reception we experience representing the Library can differ greatly depending on where in the world we are asked to go and why we are there. Usually, the reception is warm (El Salvador and Moldova have my heart always). But sometimes the environment is more tense — Cairo during the Tahrir Square protests in 2013 and Baghdad in 2003 were daunting.

It isn’t about how your host institutions receive you; it is more about how they are functioning under duress and how I as an outsider should navigate those waters. I try to bring focus to what we have in common, a concern for the preservation of cultural heritage that may be under threat.

Currently, I am delighted to be assisting the New York City-based W.E.B. Du Bois Museum Foundation to implement a preservation plan for Du Bois’ personal library in Ghana, which suffers from climate-caused deterioration. We hope to make training Ghanaian students in collections care a part of our preservation outreach.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 13, 2024

Jefferson’s Secret Cipher for the Lewis and Clark Expedition

This article also appears in the March/April issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

In May 1804, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark set off into the great unknown of the Louisiana Territory, far from help and far from home. Ahead lay vast prairies, endless mountain ranges, uncharted streams, untold dangers.

Their mission: lead the Corps of Discovery across the continent, establish relations with Native peoples they met along the way, document plant and animal life and, most importantly, find a practical water route to the Pacific.

President Thomas Jefferson, who had ordered the expedition, expected no regular communication from the corps. But he did hope that traders or Natives might help get occasional messages back to Washington. Some of those communications, he believed, might contain sensitive information best kept secret.

Long fascinated by encryption, Jefferson devised a special cipher for use by the expedition and sent it to Lewis. Only they would understand any messages encoded with it.

“Avail yourself of these means to communicate to us, at seasonable intervals, a copy of your journal, notes & observations of every kind,” Jefferson wrote to Lewis on June 20, 1803, “putting into cypher whatever might do injury if betrayed.”

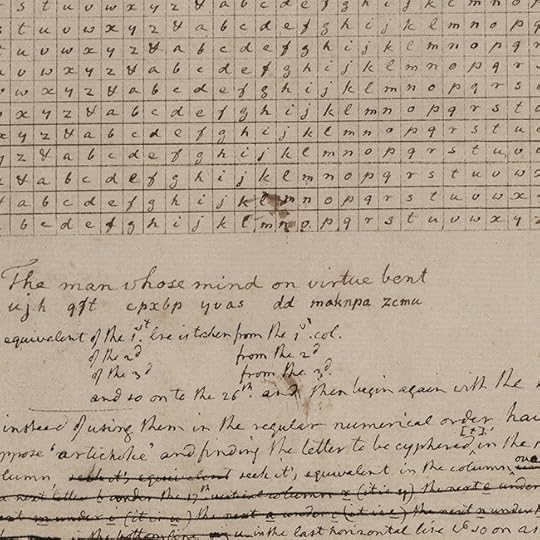

Two versions of the cipher, handwritten by the president, are preserved in the Jefferson papers held by the Library’s Manuscript Division. Both used grids of letters, numbers and symbols to encrypt and decode messages.

A portion of Jefferson’s cipher. Manuscript Division.

A portion of Jefferson’s cipher. Manuscript Division.In the earlier version, Jefferson proposed two different methods to use the cipher, one employing a previously agreed-upon keyword to encode letters of the alphabet.

At the very bottom of the page, he provided an example:

Jsfjwawpmfsxxiawprjjlxxzpwqxweudvsdmf&gmlibexpxu&izxpseer

Using the keyword “artichoke,” the incomprehensible string of letters and symbols reveals its hidden message: “I am at the head of the Missouri. All well, and the Indians so far friendly.”

Jefferson made a second, slightly revised version of the cipher and sent it to Lewis to carry west. Lewis never found the opportunity to use the cipher, which today remains a curious relic of a bold mission across a wild continent.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 10, 2024

Blondie’s “Parallel Lines” Hits the National Recording Registry

Blondie was a New York band finding its way in the mid 1970s, deeply enmeshed in the city’s arts scene but having more success in Europe after two albums than in the States.

Lead singer Debbie Harry and guitarist Chris Stein, then a couple in and outside the band, counted the young artist Jean-Michel Basquiat as a friend; the pair bought his first painting on canvas for a couple hundred bucks. They lived just off the Bowery and a few doors down from CBGB, the epicenter of punk rock.

“It was a great, decrepit atmosphere,” Stein laughed in a recent interview with the Library, with Harry joining in the conversation from a different location.

Then came “Parallel Lines,” their 1978 album that went platinum in multiple countries and helped define New Wave music. The production was crisp. The songs were short, tight and just a bit paranoid. There was “One Way or Another,” the sweet-but-cynical “Sunday Girl,” the hard-driving “11:59” and the sublimely strange “Fade Away and Radiate.” All very New York, all very punchy and all very edgy. But it was “Heart of Glass” that sent disco lights spinning and propelled the band into the pop music stratosphere.

Today, fashion boutiques and high-end grocery stores fill the old neighborhood. Basquiat’s paintings sell for tens of millions (he died in 1988; Harry and Stein sold their painting of his long ago). Blondie was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2006.

And, just a few weeks ago, that landmark album, “Parallel Lines,” was enshrined in the National Recording Registry at the Library, cementing the band’s legacy as a key part of American pop culture in the last years of the 20th century.

“‘Heart of Glass’ was the turning point,” Stein said. The song, finally released as a single in early 1979, was a megahit, particularly in the U.K.

But what set that album apart? The band had been performing for years, after all, with different versions of “Glass” in their live sets long before it was recorded.

In their interview with the Library, Stein and Harry broke it down into several key parts.

First, the group was paired for the first time with veteran producer Mike Chapman.

Chapman, an Australian native, achieved phenomenal success as a producer and songwriter in Britain in the mid-1970s. He had far more experience than anyone in the band and a sharp ear for radio singles.

Not only did he produce “Parallel Lines,” but in 1978 and 1979, he also produced the Knack’s No. 1 album “Get the Knack” (and it’s No 1 hit, “My Sharona,”) and co-wrote and produced Exile’s No. 1 hit “Kiss You All Over.” He co-wrote “The Best” and “Better Be Good to Me,” huge hits for Tina Turner, and “Love Is a Battlefield,” a No. 1 hit for Pat Benatar. He also produced Blondie’s run of hits in the 1980s.

So in a New York recording studio in the summer of 1978, he took charge. He didn’t have them play together as they had recorded in the past, but had them play individually (often after intense rehearsals), then stacked the tracks on top of another. It built a bigger, punchier sound and made the group much more “precise,” Harry said. Stein and Harry wrote most of the songs, and Chapman confidently tightened up the production, making the album sound like a unified set.

Disco was king at the time — the charts were dominated that year by the “Saturday Night Fever” soundtrack — but there was a new, post-punk sound taking shape, too. The Cars debut album came out a couple of months before “Parallel,” with hits like “Just What I Needed” and “My Best Friend’s Girl.” (That album was also inducted into the NRR this year.)

“Parallel Lines” fit this new mold perfectly, with the disco-inflected “Heart” finding the sweet spot. Released as a single early in 1979, it became one of the year’s 20 biggest selling singles.

Then there was that iconic album cover.

Broad black and white stripes filled the backdrop. The band’s five male members, all laughing or smiling, wore black suits and ties with white shirts. Harry, the lone woman, stood in the middle in a white dress, a scowl on her face and hands on her hips. It fit the attitude of the times perfectly — cool new wave, danceable pop. (The band hated the cover and weren’t aware it was going to be used. “We wanted to look like brooding rock stars,” Stein said.)

If the band didn’t like the look of the album, the executives at Chrysalis Records weren’t thrilled with how it sounded.

“They didn’t hear any hits,” Harry said.

Despite the drama, the album went No. 1 in the U.K. with three Top 10 hits. It peaked at No. 6 in the U.S. “Glass” was omnipresent on the radio and in clubs. It launched the band on a four-year run of hit records and concert tours that would ultimately land them in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

The cover, meanwhile, became instantly identifiable with the band. It still shows up as a pop culture meme, with casts of TV shows or other groups donning the suits, poses and backdrop.

The band had later hits such as “Call Me,” from the soundtrack of “American Gigolo,” and the No. 1 hits, “The Tide Is High” and “Rapture, but they broke up in 1982.

Most members pursued other music ventures, while Harry branched out as an actress, often starring in offbeat films such as John Waters “Hairspray” (now in the National Film Registry) and David Cronenberg’s “Videodrome.” (She’s continued film work ever since.)

The band reunited in the 1990s, and with drummer Clem Burke as a stalwart, Harry and Stein have kept the band going. Their most recent album, “Pollinator,” in 2017, showed them to be precise as they had been in the late ’70s with danceable tracks such as “Long Time” and “Already Naked.” They’re now on a summer-long tour that will carry them to Europe and back to the States.

Harry and Stein both say that Blondie’s existence has always been more about pushing artistic boundaries than just the pursuit of hits. Stein says that while the band achieved a spot in history, it’s not quite like they dominated the charts, the Grammys or arena-sized concert venues. They do some mass market business, but they’re not a mass market band.

“The old problems of art and commerce are sometimes very restrictive,” Harry said, “and I think that we, somehow being a bit of a fringe element, got to do some things that were groundbreaking.”

“We’re still big in CVS,” Stein joked. ” ‘Tide Is High’ is on almost every time I go in there.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers