Library of Congress's Blog, page 17

February 9, 2024

It’s Sew Complicated

This article also appears in the January-February issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

For 10 cents a copy, Harper’s Bazar magazine opened up a wide world for the modern woman of 1902.

In its March issue, there are essays on the growing women’s movement and advice on husband management. There are European travelogues, bedtime stories, home improvement suggestions, fiction series and spreads illustrating the latest styles (one indelicately headlined “Fashions for Old Ladies”).

For DIYers looking to save a buck on clothing, Harper’s also offered help, tucked between the regular “Recent Happenings in Paris” column and a how-to titled “Poultry Raising as a Vocation.”

There, a large foldout sheet lays out sewing patterns for the thrifty homemaker to use in making clothes for the family — “at the lowest computation,” Harper’s assured readers, a value of $3.50.

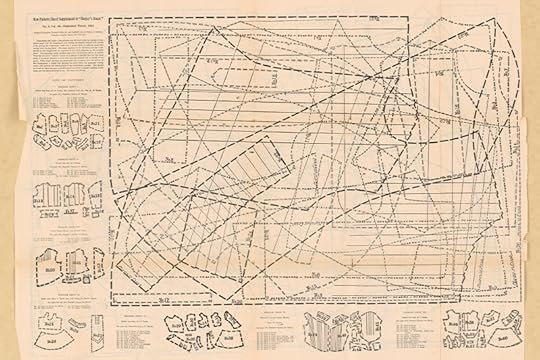

Harper’s 1902 foldout sheet with 60 designs for pieces of clothing.

Harper’s 1902 foldout sheet with 60 designs for pieces of clothing.When unfolded, the sheet reveals a bewildering tangle of dots, dashes, lines, X’s and ovals that crisscross a total of 1,134 square inches of paper in an unholy mess covering both front and back. The marks delineate patterns for a whopping 60 different component parts of articles of clothing.

From the chaos, nine outfits could emerge: a girl’s bodice, a baby’s petticoat, a boy’s shirtwaist, a girl’s corset cover, a little girl’s dress, a dress for a girl of about 12, a woman’s lawn waist, a tucked fancy lawn waist and a fancy stock and tie.

The trick, of course, was making them happen. The magazine provided instructions, perhaps easier read than done: Simply place transparent paper over a pattern and trace the lines with a pencil or, alternately, place the pattern itself over a sheet of paper and use a tracing wheel to copy the design. The seamstress then would extrapolate the proper size of each piece, take out the sewing machine and, voilà, the kids have new clothes.

Today, with the benefit of hindsight and easy modern clothing options, we can admire the resourcefulness of any Harper’s reader willing to tackle that job and, then, silently offer up a few words of gratitude: Thank goodness for off the rack.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

February 6, 2024

Life and Fashion in the American 20th Century

This is a guest post by Sahar Kazmi. It appears in the January-February issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

In between drawings of corseted debutantes and ads for breeches and hair tonic, the 1892 first issue of the iconic Vogue fashion magazine includes a brief feature on the origins of its namesake. Vogue, the excerpt explains, comes from the Italian “voga,” the French “voguer” and the German “wogen” — all of which refer to rowing, sailing or floating.

The words are fitting roots for a publication about fashion, an art form famous for bouncing along the waves of change. Throughout the ages, fashion has responded to social events and reflected the shifting culture of its time. It’s been an avenue for reference and reinvention, expressing societal viewpoints and political movements through fabric and adornment.

As the Library’s collections demonstrate, this was especially true for 20th-century fashion in the U.S. The story of American style is depicted in the Library’s century-old newspapers and magazines; in department store catalogs and home-sewing pattern books; in vintage lithographs and high-gloss photography.

Fashion is a tale of changing conventions: the loosening of a silhouette, the rise of a hemline. It’s a history of attitudes embraced and rejected: the anxieties of war or the delights of social liberation. Often showcased as the terrain of women, it routinely embodies their fantasies and evolving place in society.

Part of a page from McCall’s Magazine in 1930, showing womens’ sportswear designs.

Part of a page from McCall’s Magazine in 1930, showing womens’ sportswear designs. Publications in the first decade of the 1900s depicted mainly women of wealth and status, richly ornamented with embroidery and tailored lace. Their ideal shape, achieved with what was dubbed a “health corset” in advertisements, was the contorted S-curve.

“It is the result of much study of all the points most essential to a perfect figure and conformity to the present fashion,” proclaimed an ad for the Paris Model corset in a 1903 issue of Vogue.

The S-shaped corset pushed the bustline forward while tilting the hips back, creating a narrow waist and curvy profile. The look wasn’t a dramatic departure from the rigid styles of the 1890s, but bulky skirts and bendy waistlines began to loosen as the 1910s approached.

The empire waist dress, popularized during the late 18th-century Greco-Roman revival, made a comeback in fashion literature. Its shape featured a fitted bodice with fabric flowing down from the bustline, creating a relaxed silhouette around the waist.

Clothing with room to move and breathe was key as World War I erupted in 1914. European women put on trousers and overalls to serve in wartime factories. American women, already familiar with the simplified tunics and uniform-style jackets of the suffrage movement, followed suit when the U.S. joined the fray in 1917.

Even the wealthiest women who never stepped foot in a munitions plant or military unit took part in the shifting aesthetics of the day. A 1917 newspaper spread touting the latest designs from British clothier Lady Duff-Gordon showcased, “A new walking dress with a military touch.”

As the war ended and women gained the right to vote in 1920, fashion publications highlighted the vibrancy of the Roaring Twenties. Alcohol was prohibited nationwide, but the postwar economy was booming and the middle class was richer than ever. Speak-easies popped up like weeds to sell homemade liquor to the war-weary masses as jazz rang out through the night.

Women’s fashion championed straight lines and much shorter skirts — all the better for dancing the Lindy Hop and the Charleston. A once-voluptuous bodily ideal gave way to a more androgynous form, with the loose and swingy flapper dress quickly becoming a favorite of the period.

When the party came crashing to end with the Great Depression, hemlines once again fell to the ankles. Simplicity still reigned supreme, in large part because it was more affordable. For working and middle-class women struggling to make ends meet in the 1930s, the sensuous fashions of Hollywood stars provided the romantic standard of the day.

A fashion model poses on the steps of the Jefferson Memorial in 1952. Photo: Toni Frissell.

A fashion model poses on the steps of the Jefferson Memorial in 1952. Photo: Toni Frissell.Their garments, made of slinky silk and satin, were cut “on the bias,” hanging diagonally across the body. In an age of uncertainty and financial fear, figure-hugging femininity was back in vogue. At the same time, women’s fashion embraced structured suiting, incorporating wide shoulders and crisp jackets.

But drapery wasn’t only for women. Black, Latino and other men of color favored the flamboyantly wide legged and long-jacketed “zoot suit” as a symbol of political subversion in the 1930s. Labor activist César Chávez was said to have sported zoot suits in his teens, and Malcom X even describes purchasing his first zoot suit (“Sky-blue pants thirty inches in the knee”) in his famed autobiography.

The Delta Rhythm Boys, a popular mid-century quartet, wearing zoot suits. Wikimedia Commons.

The Delta Rhythm Boys, a popular mid-century quartet, wearing zoot suits. Wikimedia Commons.Eventually, just as World War I had dominated the styles of the 1910s, the Second World War came to have an outsized effect on the clothing of the 1940s. Skirt suits retained their popularity, now simplified even further by material rationing into regulated “utility dresses.” Overalls and trousers for women came back strong, with functional fabrics like tweed and cotton finding prime place in women’s wardrobes.

The end of World War II gave way to what became known as “The New Look.” In 1947, the French couturier Christian Dior debuted his “Corolle” collection, a line of tiny-waisted, voluminous skirts and exaggerated padded hips. Fashion publications hailed it as a return to formalized femininity and luxurious use of fabrics after the deprivation of war.

But as with the continuous reimagining of the female form, each era of fashion was in some way a reaction to the styles that came before it. By the time the 1960s rolled around, the U.S. was in the throes of a cultural rebirth — the civil rights movement was growing in urgency, students were protesting the Vietnam War and second-wave feminists were widening the gains of their suffragist forebears.

Popular fashion in magazines was no longer prim and dainty. This was the age of the miniskirt and knee-high go-go boot. The “Black is Beautiful” movement spotlighted traditional African prints and fabrics, and the burgeoning hippie look turned to flowing peasant shirts and bell-bottom jeans for men and women alike.

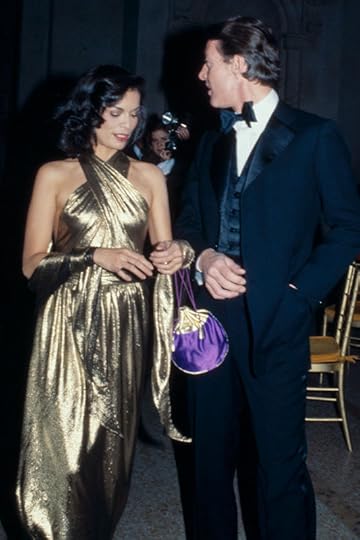

Fashion icon Bianca Jagger at a gala in 1977. Photo: Bernard Gotfryd.

Fashion icon Bianca Jagger at a gala in 1977. Photo: Bernard Gotfryd.While the short, straight-line dresses of the 1960s had harkened back to the linear fashions of the ’20s, the aesthetics of the following decade drew inspiration from the 1930s. Disco outfits and prairie dresses held prime place in the 1970s, but the everyday woman might just as easily be found in a smart suit or below-the-knee skirt. Designer Diane von Furstenberg’s iconic wrap dress touted a flattering, body-skimming silhouette reminiscent of bias-cut favorites from the ’30s.

Fashion was more democratized than ever, available everywhere and increasingly casual. Sportswear as day-dressing had been popular since the pleated tennis dresses of the ’20s, but everything was bigger and louder in the 1980s. This was the era of dancewear and sweatshirts, leggings and high-cut leotards. Shoulders were wider even than those of the ’30s, accessories bolder than the embellishments of the early-1900s and sleeves as puffy and ballooning as the ones in the original European Renaissance.

It’s no surprise then that 1990s fashion publications featured a more minimalistic direction. Plain white T-shirts and denim were all the rage, and sportswear reached new heights with hip-hop artists popularizing tracksuits and luxury sneakers.

Casually oversized looks, from baggy grunge and plaid to practical puffer coats found their way into catalogs and magazine spreads. Even on red carpets, women wore simple column and slip dresses.

“Fashion is and has been and will be, through all ages, the outward form through which the mind speaks to the material universe,” the scholar George Patrick Fox once said in his 1872 treatise on the philosophy of style.

As the 20th century reached its end, fashion had left the exclusive domain of the elite. It had become the playground of an ever-changing culture.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

January 30, 2024

Elton John & Bernie Taupin = 2024 Gershwin Prize

Elton John and Bernie Taupin, one of the great songwriting duos of all time, will be the 2024 recipients of the Library of Congress Gershwin Prize for Popular Song, Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden announced today.

The pair met in the U.K. in 1967, when John was a young piano player and Taupin was a struggling lyricist. They quickly forged a a songwriting partnership that shaped popular music, sold hundreds of millions of records and became a cultural juggernaut that continues to influence musicians today.

“Crocodile Rock,” “Tiny Dancer,” “Rocket Man, ” “Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me,” “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road,” “Bennie and the Jets,” “Your Song” — all became pop standards.

“Elton John and Bernie Taupin have written some of the most memorable songs of our lives,” Hayden said. “Their careers stand out for the quality and broad appeal of their music and their influence on their fellow artists. More than 50 years ago, they came from across the pond to win over Americans and audiences worldwide with their beautiful songs and rock anthems. We’re proud to honor Elton and Bernie with the Gershwin Prize for their incredible impact on generations of music lovers.”

The pair still work together and the process has always been the same: Taupin writes lyrics and sends them to John, who goes to work at the piano and creates a song.

“I’ve been writing songs with Bernie for 56 years, and we never thought that that one day this might be bestowed upon us,” John said. “It’s an incredible honor for two British guys to be recognized like this. I’m so honored.”

“To be in a house along with the great American songwriters, to even be in the same avenue is humbling, and I am absolutely thrilled to accept,” Taupin said.

The pair will be honored with a tribute concert in Washington, D.C., that will premiere on PBS stations nationwide on April 8 at 8 p.m. ET.

Bernie Taupin and Elton John. Photo: Gavin Bond.

Bernie Taupin and Elton John. Photo: Gavin Bond.Today, John is among the top-selling solo artists of all time with more than 70 Top 40 hits over the course of six decades, including nine No. 1s and 29 Top 10s on the Billboard Hot 100. He has sold more than 300 million records worldwide. He holds the record for the biggest-selling physical single of all time with Taupin’s rewritten lyrics for “Candle in the Wind 1997,” which sold more than 33 million copies. In 2018, he was named the most successful male solo artist in Billboard Hot 100 chart history. In America, John holds the record for the longest span between Billboard Top 40 hits at 50 years.

In 1992, John established the Elton John AIDS Foundation, which continues to be a leader in the global fight against HIV/AIDS. The foundation has raised more than $565 million for HIV/AIDS grants that have funded more than 3,000 projects in over 90 countries to care for patients and provide education for AIDS prevention. His music and charitable service have been honored with a knighthood from Queen Elizabeth II; the Légion d’honneur, France’s highest award; and the National Humanities Medal awarded by President Joe Biden at the White House in 2022.

Since launching his first tour in 1970, John has delivered more than 4,000 performances in more than 80 countries. His work has spanned recording studios, stadiums, stages and screens — always with music that resonates with new generations of audiences. Disney’s “The Lion King,” carried by John’s tunes, continues to be one of Broadway’s longest running shows.

In January, John won an Emmy Award for outstanding variety special for his show “Elton John Live: Farewell from Dodger Stadium,” making him just the 19th performer to achieve rare EGOT status, having also won five Grammys, two Oscars for his work on “The Lion King” and with Taupin on the movie “Rocketman,” and a Tony Award for the score to the Broadway musical “Aida.”

Soon John and Taupin will have a Gershwin Prize to add to the mix for an even more exclusive distinction.

While their work has been intertwined for decades as co-writers, Taupin often preferred to stay behind the scenes. In their first two years, Taupin and John mostly wrote for other artists. Their first album, “Empty Sky” in 1969, was followed by “Elton John” in 1970. That second album, including the single “Your Song,” helped define their style for soaring ballads and rock songs. Taupin’s narrative songwriting, influenced by folk music, blues and country, offered the words that helped John’s melodies soar.

In addition to his work with John, Taupin has written hit songs for other artists, including Starship’s “We Built This City” and Heart’s “These Dreams,” as well as songs for Alice Cooper and Brian Wilson. In 2006, he earned a Golden Globe for “A Love That Will Never Grow Old” from the movie “Brokeback Mountain.”

Taupin moved to Southern California, became a U.S. citizen, and developed a love for the American West. He competed in weekend horse shows and hosted a competition for cowboys at his Santa Barbara ranch. All along, he continued writing for John from a distance, and began writing and making music with his Americana band, Farm Dogs. Taupin also turned to another of his passions — painting abstract and contemporary mixed-media — and he considers art his full-time career.

The 1975 album “Captain Fantastic and the Brown Dirt Cowboy” has been called their autobiographical album as alter egos, with the song “We All Fall in Love Sometimes” describing their partnership as one of the most important relationships of their lives. Taupin and John were inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1992. In 2023, John inducted Taupin into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Established in 2007 in recognition of the legendary songwriting team of George and Ira Gershwin, the Library’s Gershwin Prize for Popular Song is the nation’s highest award for influence, impact and achievement in popular music. (The Gershwins’ papers are preserved at the Library, and George’s piano is on permanent display.)

The honoree is selected by the Librarian in consultation with a board of scholars, producers, performers, songwriters and music specialists, as well as curators from the Library’s Music Division, American Folklife Center and National Audio-Visual Conservation Center. Previous recipients are Paul Simon, Stevie Wonder, Sir Paul McCartney, songwriting duo Burt Bacharach and the late Hal David, Carole King, Billy Joel, Willie Nelson, Smokey Robinson, Tony Bennett, Emilio and Gloria Estefan, Garth Brooks, Lionel Richie and Joni Mitchell.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

January 25, 2024

The Library Wants Your COVID-19 Stories!

The COVID-19 pandemic that erupted on a global scale almost four years ago left a long trail of loss and grief. It also showcased the unity, resilience and humanity of Americans.

Now the Library, in collaboration with the nonprofit organization StoryCorps, has launched the COVID-19 Archive Activation website to encourage everyone share their COVID-19 stories.

Stories will be deposited into the American Folklife Center and made accessible at archive.StoryCorps.org. The new website will contribute to a deeper and more complete understanding of how Americans faced this public health crisis.

The outbreak was first declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization in March 2020 after tens of thousands of cases were reported in 114 countries. The pandemic claimed the lives of more than 1.1 million people in the United States alone, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It also triggered the lockdown of schools and the shutdown of businesses and forced Americans to adapt to an unwelcomed new normal.

By creating a tool to collect and preserve Americans’ pandemic experiences, the Library is honoring those who lost loved ones to COVID-19, those who worked on the frontlines and those who were, and continue to be, impacted during this time in American history.

“Curators and specialists at the Library are skilled at documenting history as it happens,” said Carla Hayden, Librarian of Congress. “Recording the voices and stories of Americans’ experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic for our national collections will honor this history and ensure these stories will not be forgotten.”

The new website is part of the COVID-19 American History Project — a congressionally mandated initiative to document and archive Americans’ experiences with the pandemic. In addition, the AFC has contracted oral historians to document the stories of frontline workers and created a research guide to COVID-19 collections.

One person interviewed is Benjamin Ezra Ciereszynski, a student at Louisiana State University, who worked in the service and hospitality sector in New Orleans when COVID hit.

Cierenszynksi remembers “the hushed rumors” and the anxiety creeping in about the virus while other colleagues in the mom-and-pop restaurant hoped it would “blow over in two or three weeks.”

“It made the work environment a little tense; everyone was on edge because they thought they might lose their jobs for a good bit, which they did,” said Cierenszynksi. “At first (staying home) was fantastic … no work, no school, no obligations at all except for household chores, so it was just me locked in my room playing video games with my friends for about six months.”

When the novelty of the lockdown wore off and the new reality set in, “things started to get depressing. It felt like I was in a zoo enclosure … looking for any excuse to get out of the house.”

For some, COVID-19 remains part of their everyday experience. Some still are battling long-haul symptoms and sharing one’s story can be a way to heal, to commemorate and to honor others affected by the pandemic.

“Our goal for the COVID-19 Archive Activation page is to honor those who experienced this tumultuous moment in our nation’s history, commemorate those who were lost to the pandemic and to educate future generations about what life was like during COVID-19,” said Nicole Saylor, AFC director.

The website Key to the COVID-19 Archive Activation page is the AFC’s partnership with StoryCorps.

Both StoryCorps and the AFC share a mission to collect and preserve personal-experience stories that portray the everyday, often-undocumented moments of Americans’ lives, so documenting oral narratives from the pandemic came as a natural fit.

“This partnership will build on over 20 years of collaboration between the American Folklife Center and StoryCorps and serve to further the mission of each institution to capture, describe and preserve the cultural heritage of the United States,” said Virginia Millington, managing director of program operations at StoryCorps.

To share how you experienced the pandemic, enter the COVID-19 Archive Activation website and follow the instructions to record your story or to interview someone else. The page includes tips and considerations for recording your story and a list of questions to prepare for interviews. Once finished, you can find your story, or that of others, on the StoryCorps Archive.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

January 22, 2024

“Feeling Good” About the Leslie Bricusse Collection

In the late spring of 1962, two young British songwriters were following up on their first hit play, “Stop the World — I Want to Get Off.”

The songwriting team — Leslie Bricusse and Anthony Newley — were up-by-the-bootstraps types, just hitting their 30s, and would become big stars. Bricusse, whose papers are now in the Library, would win two Oscars and one Grammy, writing or co-writing hits for everything from two James Bond films to “Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory” to “Victor/Victoria.”

But on this day — May 15, 1962 — none of that had happened yet.

Bricusse flipped open his notebook and sketched in a song they were putting together. It was set to be the 12th piece in their new musical, “The Roar of the Greasepaint — The Smell of the Crowd,” a comic allegory about class differences in Britain. The song was a minor piece for a minor character.

He called it “Feeling Good.” The play, with its awkward title and weighty subject, was only a modest hit on Broadway.

But that song! Its simple lyrics, rooted in sunshine and swagger, opening in a cappella clarity, were set off perfectly by brassy horns that saunter in on the second verse. It’s so malleable, so simple in emotion, that it became a template for a performer with a big voice and a big personality.

Nina Simone was one of the first, stamping it as an anthem of female sensuality and self-confidence in 1965. Bolstered by her unique vocals, it hit with the knowing power of a Maya Angelou poem.

Bird flying high

You know how I feel

Sun in the sky

You know how I feel

It quickly became one of her iconic songs and is still popular with millions; a flashy new music video of it was released in 2021, featuring four generations of Black women. Canadian balladeer Michael Bublé released his swanky version in 2005, gaining worldwide audiences and more than 238 million views on YouTube. Others? Plenty, in pop and jazz, by names such as John Coltrane, Sammy Davis Jr., George Michael and, yes, The Pussycat Dolls.

Not a bad day’s work for Bricusse and Newley in the spring of ’62. One hopes they took the rest of the day off.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

January 19, 2024

Q&A: Jessica Castelo

Jessica Castelo is a museum technician in the Visitor Engagement Office.

Tell us about your background.

I am originally from a city in the greater Los Angeles area called Downey. I attended California State University Channel Islands for my bachelor’s in history and the University of Southern California (USC) for my master’s in library and information science. I was fortunate to intern at the Library from September to December 2022 while finishing grad school.

After my internship, I worked as a medical records clerk in Los Angeles briefly before moving back to Washington, D.C.

What brought you to the Library, and what do you do?

During my Library internship, I worked in the Visitor Engagement Office and the Informal Learning Office. Shortly after my internship ended, my current position opened, and I returned to the Library in August 2023.

As a museum technician, I help to oversee visitor operations in the Jefferson Building and ensure that our visitors have a positive experience.

Examples of daily tasks include running the Main Reading Room experience, staffing the ticketing podium and information desks and engaging with visitors by sharing my knowledge of the Library. I also work Live at the Library events on a rotating schedule with my fellow museum technicians.

What are some of your standout projects?

One of my standout projects is from my internship last fall. I worked on a research project for the 125th anniversary celebration of the Jefferson Building’s opening. I conducted research in the online catalogs of the Manuscripts and the Prints and Photographs divisions to create a PowerPoint presentation on the building’s construction and its first few years of being open. I also created a reference sheet for volunteers to get a sense of what the very first opening day was like for visitors.

This was a very rewarding project, and I am grateful my internship allowed me to be a part of such a monumental event. The project was especially valuable to my current position, because I can now speak to how the Library can be used for in-person and online research.

What do you enjoy doing outside of work?

I enjoy reading and exploring the different neighborhoods of D.C. I am still pretty new in town and love exploring everything D.C. has to offer. I combine my interests by visiting different bookstores in the city and finding new parks outside of my neighborhood on Capitol Hill to sit in and read.

What is something your co-workers may not know about you?

I have a twin sister! We are fraternal twins and opposites in personality. So, even when we are standing next to each other, people don’t usually guess it.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

January 18, 2024

Historic Photos: The Wright Brothers, at Home and in the Air

This story appears in slightly different fashion in the November-December issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

In the old days, when people reached a certain level of wealth and/or prominence, it wasn’t unusual for them to give their house a name. It conjured up a certain identity, a presence of the sort engendered by also calling the house an “estate,” “residence,” “family retreat,” or just “mansion.” The Rockefellers had Kykuit in New York’s Hudson Valley, the Vanderbilts had Biltmore in North Carolina, Faulkner named his Mississippi home Rowan Oak, Hemingway had Finca Vigía in Cuba, and so on.

Orville Wright, a modest and practical man, named his Ohio home Hawthorn Hill. He named it for the Hawthorn trees that grew on the property and it was, indeed, built atop a small rise. (We said he was practical.) He and Wilbur, his brother and aviation partner, had designed the place and both planned to live there, but Wilbur died of typhoid fever before it was completed. Orville, his sister Katharine and their father made it their home. It’s nothing on the scale of Kykuit or Biltmore, but grander than Rowan Oak or Finca Vigía. Like all of the places mentioned above, it’s now a museum and tourist attraction.

You can see it as the backdrop — built to impress but not to overwhelm — in several photographs that were among the materials the Wrights gave to the Library after Orville’s death in 1948. Included were over 300 glass plate and nitrate negatives of photographs taken (mostly) by Orville and Wilbur between 1897 and 1928 — images that provide an important and fascinating record of their home lives and of their attempts to fly.

About 200 of the photos chronicle the brothers’ successes and failures with their new flying machines. Taken from 1900 to 1911, the images document the Wrights’ laboratory, engines, models, runways, flights, mishaps and daily life at Kitty Hawk.

The remodeled 1905 Wright machine, altered to allow the pilot to sit instead of lay flat, plus a passenger seat, on the launching track. Prints and Photographs Division.

The remodeled 1905 Wright machine, altered to allow the pilot to sit instead of lay flat, plus a passenger seat, on the launching track. Prints and Photographs Division.Orville and Wilbur assemble a plane in a covered building on the beach. A crumpled glider rests on the sand following a crash. A local boy holds a freshly caught drum fish. And, that December day in 1903, the first powered flight, with Orville at the controls and Wilbur running alongside as the machine lifts from the Earth.

Orville Wright’s Saint Bernard, Scipio, in his summer cut, relaxes on the family front porch. Prints and Photographs Division.

Orville Wright’s Saint Bernard, Scipio, in his summer cut, relaxes on the family front porch. Prints and Photographs Division.The collection also shows the brothers with family and friends back home in Ohio, in and around Dayton. Orville works in their bicycle shop. His pet Saint Bernard, Scipio, lies on the front porch of the family’s home. A third brother, Lorin, poses with his three children.

And then there’s the semi-formal family photo at the top of this post. Dayton History, the nonprofit organization that manages Hawthorn Hill today, refers to it as Orville’s “success mansion” and that’s just right. The double set of stately white columns framing the entrance, the wide steps, the grand door — it presents itself with the grandeur of a manor, the home of someone who has made a success in the world and the house is the emblem of that success.

The house says a lot about Orville Wright, mainly in its reserved stateliness, and the rest of the photographs in the collection show he and his brother’s eye for the world that they shaped and thern remade with their world-changing invention.

The full collection is online, waiting to be explored.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

January 10, 2024

“Dr. Atomic,” The Oppenheimer Opera

This is a guest post by Kate Rivers, a specialist in the Music Division. It also appears in the January-February issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

The setting: the San Francisco Opera and the 2005 sneak preview of “Doctor Atomic,” a new opera by Pulitzer Prize-winning composer John Adams based on the compelling saga of physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer and the other scientists who engineered the world-altering test of the first atomic bomb.

In the audience sat Marvin L. Cohen, president of the American Physical Society, amateur musician and real-life physicist from the University of California, Berkeley — the school that had been Oppenheimer’s academic home.

The opera’s first words drew Cohen’s professional attention:

Matter can be neither created nor destroyed, but only alter ed in form.

Energy can be neither created nor destroyed, but only altered in form.

Sheet music from “Doctor Atomic.” Music Division. Copyright by Hendon Music Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company. Used with permission.

Sheet music from “Doctor Atomic.” Music Division. Copyright by Hendon Music Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company. Used with permission.Celebrated director and Adams collaborator Peter Sellars had devised the libretto, drawing directly from once-secret government documents, official government publications and firsthand accounts of scientists working to pull off the Trinity test. (Oppenheimer’s papers, which document much of this history, are also preserved at the Library.)

Cohen, however, believed those first words presented a problem: The text did not reflect scientists’ knowledge in 1945. Oppenheimer would have known better.

The solution to that problem is documented in the archival collection of Adams’ music manuscripts and papers, acquired by the Library this year even as Christopher Nolan’s blockbuster film “Oppenheimer” brought renewed buzz to the subject.

The material related to “Doctor Atomic” includes costume designs, concert programs depicting the famous blast and oversized music manuscript pages, rich with Adams’ pencil handwriting.

To correct the error noticed by Cohen, Adams and Sellars adjusted the music and text to convey a scientific perspective that would have been right in Oppie’s view:

We believed that “matter can be neither created nor destroyed but only altered in form.”

We believed that “energy can be neither created nor destroyed but only altered in form.”

But now we know that energy may become matter, and now we know that matter may become energy, and thus be altered in form.

It goes to show that words, and words in music, matter.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

January 5, 2024

Q&A: Angela Kinney

Angela Kinney was named deputy director of the Acquisitions and Bibliographic Access Directorate in November.

Tell us about your background.

I was born in Cincinnati to a family of 11, including my parents. My father and mother believed strongly that one is best educated in Catholic schools. Following their religious beliefs, I spent nearly the entirety of my formal education attending Catholic schools, including college and graduate school.

After graduating from an all-girls high school, I set my sights on moving to the Washington, D.C., area to further my education and interest in foreign languages. I applied only to Georgetown University and Trinity College, both Catholic schools that had outstanding foreign language study programs.

Ultimately, I completed my bachelor’s degree at Georgetown in languages and linguistics and later obtained a master’s degree in library science at the Catholic University of America.

What brought you to the Library, and how has your career evolved?

My original goal after finishing my undergraduate degree was to pursue a career as a diplomat in the foreign service. However, a fellow student from Ohio told me about job opportunities at the Library. I remain so thankful that I was able to express my gratitude to my friend, to whom I owe my professional career, before he passed away. He died shortly after I got my job at the Library.

At that time, I had no idea that the help he lent me to navigate the process of applying would turn into a career that would last for 42 years and counting, all at the Library.

My first job was as an information counter attendant in retail sales, where I learned about the Library’s infrastructure and how to manage federal funds. I met some of the most renowned dignitaries in the world in that position, including Henry Kissinger. He stopped by the gift shop one day to make a purchase and ended up chatting with me for 10 minutes!

Over the past four decades, I have held progressively responsible positions — technician, librarian, first-line supervisor, chief of the Social Sciences Cataloging Division. For 15 years, I served as chief of the African, Latin American and Western European Division, an acquiring and cataloging unit. I will always look back on the years I spent managing SSCD and ALAWE as some of the most inspiring of my tenure at the Library.

Most recently, I was thrilled to be selected for the position of deputy director in the Acquisitions and Bibliographic Access (ABA) Directorate, a job I assumed on Nov. 20. My duties are to support the ABA director and to provide oversight for the U.S./Anglo, Asian and Middle Eastern and Germanic and Slavic divisions. Stepping into this new position, I feel a sense of satisfaction knowing that I have brought about positive changes at Library.

What are some of your standout projects?

While serving on detail as a Leadership Development Program intern two decades ago, I led the Library’s initiative to launch the Employee Express program, the precursor to the Employee Personal Page. I also implemented the Library’s first shelf-ready cataloging operation, which involved training a book vendor to create cataloging records in the same fashion Library staff members do.

The most significant task that lies ahead for me as deputy director is to develop an arrearage reduction plan for ABA. I am excited about the careful collaboration with colleagues this monumental assignment will entail.

What do you enjoy doing outside of work?

I do not have much spare time, because I have always been one to work long hours. However, I do enjoy traveling and spending most of my leisure time with family and close friends.

What is something your co-workers may not know about you?

What most colleagues do not know about me is that I am super passionate about genealogy. I am a big fan of Henry Louis Gates’ PBS program “Finding Your Roots.” Following the genealogical techniques from his show, I successfully traced the lineage of my father’s side of my family back six generations. I shared the results at a family reunion last summer, and the joy I saw on the faces of my relatives confirmed that they will be depending on me to be the family genealogist in the future!

January 4, 2024

Football Forever!

We’re down to the college football national championship game next week and the NFL playoffs are just around the corner. It’s a perfect time to check in with “Football Nation” author Susan Reyburn as she chooses favorite items from the Library’s collections. This article is slightly adapted from the January-February issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

The First Football Card

Tobacco companies produced the first sets of sports cards, which were packaged with cigarettes and other tobacco products, to encourage repeat purchases from consumers wanting to collect complete sets of featured cards. Captain Edward Beecher, who played quarterback for Yale, then the nation’s dominant college team, was the great nephew of Harriet Beecher Stowe and Henry Ward Beecher. He had the distinction of appearing on the first football trading card, produced by Old Judge and Gypsy Green Cigarettes in 1888.

‘On, Wisconsin!’

Written by William T. Purdy and Carl Beck in 1909 at the height of the Tin Pan Alley era in popular music, the University of Wisconsin fight song is among the most highly rated examples of the niche musical genre. The lyrics specifically address football prowess, such as “plunge right through that line,” and hundreds of high school bands nationwide have borrowed the instantly recognizable tune — with revised words — for their own use on game night.

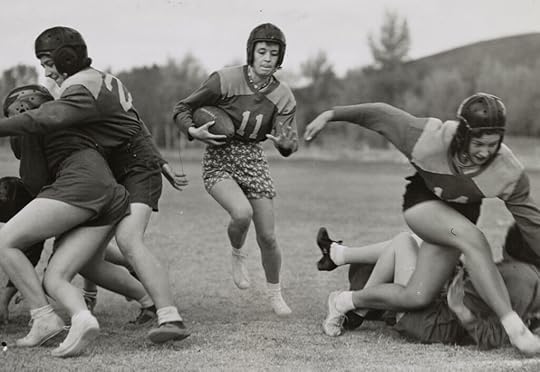

The ‘Powder Puff’ Game

Aided by terrific blocking, team captain Alice Shanks cuts through the line, leading the upper-class women to a 13-6 intramural win over the sophomore-freshman team at the Western State College Powder Bowl in Gunnison, Colorado, in 1939. That season, Spalding & Bros. published “American Football for Women: Official Rules,” and “powder puff” games associated with homecoming festivities grew in popularity. Women’s informal tackle football first appeared on a few college campuses in the 1890s, and various professional and semipro leagues have operated since 1965 to the present day.

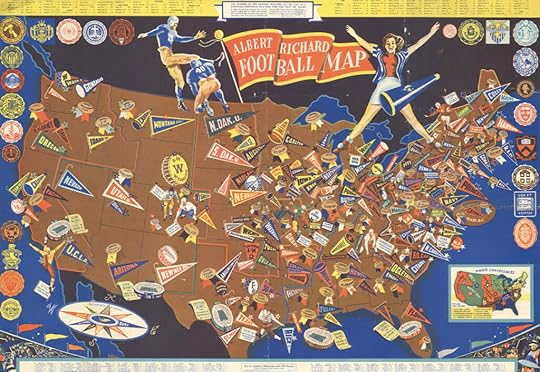

Albert Richard All-America Football Map

Waving banners, smiling players and dancing mascots flash across the United States in this cartographic depiction collegiate sports conferences by F.E. Cheseman in 1941. The map also lists the NFL’s 10 professional clubs, offers a key to referee signals and provides recent team records and bowl game results. Viewed today, the map is a visual celebration and record of the major college conference system that is now undergoing dramatic change.

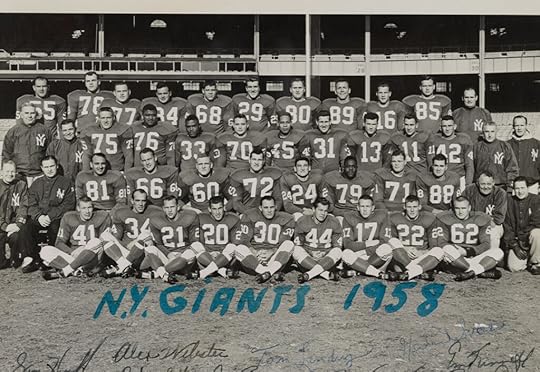

1958 New York Giants

This New York Giants team lost in overtime to the Baltimore Colts in the 1958 NFL championship game, known as “The Greatest Game Ever Played.” The core of that team featured two future Hall of Fame coaches (assistants Vince Lombardi, third row, second from left, and Tom Landry, third row, far right) and notable players such as Pat Summerall (88), Rosey Grier (76), Sam Huff (70), Don Maynard (13), Charlie Conerly (42) and Frank Gifford (16). Future New York congressman and 1996 Republican vice presidential nominee Jack Kemp, who played on the Giants’ taxi squad, signed the image but doesn’t appear in the photograph. The photo comes from the Kemp papers in the Library’s Manuscript Division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers