Library of Congress's Blog, page 20

October 11, 2023

Dancing the Danzón: Hispanic Heritage Month

Ballroom dancers would argue that the danzón is a metaphor for romance, like a graceful waltz through history, and with good reason. The rhythms of different cultures have blended in Caribbean and Latin American dance halls in this sensuous genre for nearly 150 years. The dancers’ steps narrate stories spanning generations.

Born in 19th-century Cuban dance halls, danzón eventually became the country’s official national dance. It continues to thrive outside the big island’s borders, in Mexico and beyond, in orchestra halls and dance salons, leaving an indelible mark on Latin American culture. Its legacy resonates in dances such as salsa, mambo, cha-cha and bolero. It also shares similarities with American music traditions, such as jazz and big band swing.

Still, it’s a genre all its own and a lovely bit of romance to remember during Hispanic Heritage Month here in the U.S. The Library has plenty of music, films and books to help you explore its rich history. It also held a danzón exhibition in late September.

Originating from the English country (or folk) dance, danzón was adapted by the French as contredanse and the Spanish as contradanza. Originally, this kind of dancing was for several couples, starting in two lines (gentlemen on one side, ladies on the other), with each couple working their way to the front of the line, then falling back to the rear. This developed into the quadrille, which included four, if not five, couples executing swirling (but chaste) turns with different partners in the group, working their way back to the beginning.

But in 19th-century colonial Cuba, with sugar plantations mixing European and African cultures, the danzón melded African rhythms with European musical structure. Something new was afoot.

Danzón’s charm lay in the connection between a couple as they engaged in fluid movements without being overtly sexual, their eyes locked. As the women’s flowing dresses billowed and twirled, and the men dipped and spun them until the music faded, audiences would nod, smile and applaud. This sensuous genre took off in dance salons, where Cuba’s elite gathered. It quickly became a symbol of national identity.

The father of danzón was Miguel Faílde. His orchestra premiered the first danzón piece, “Las alturas de Simpson,” (“The Heights of Simpson”) in Matanzas in 1879. It had the characteristic slow tempo, charanga instrumentation and intricate dance choreography that came to define the genre.

You can see this in the 1991 film “Danzón” by Mexican director María Novaro. (The Library’s National Audio-Visual Conservation Center preserves 35 mm prints of the film.) The film captures the music’s nostalgic and romantic essence.

The story revolves around Julia (María Rojo), a telephone operator by day and danzón enthusiast by night. She goes on a frantic search for her missing dance partner, Carmelo (Daniel Rergis), in the port town of Veracruz.

The film showcases the elegance and tradition of danzón against a backdrop of vintage décor. Couples in elegant attire glide across polished dance floors under the soft, warm glow of ornate chandeliers. Young enthusiasts and seasoned aficionados yield to the music with deliberate movements and intricate footwork, swaying with grace and poise, powering through turns, spins and dips.

“Danzón is a movie that bets on nostalgia, reviews our sentimental education, and that I tried all the time to make in a ludic, playful way,” said Novaro during a 2015 interview in Mexico City with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Oral History Project. “[This movie] was about revisiting our sentimental education but in the ’90s, and also feminist, right? With a different perspective of how things should be or how the dialogue between men and women should be.”

A song from the score, “El teléfono a larga distancia” (“Long-distance Telephone”), a lively instrumental composed by Aniceto Díaz in 1921, is also preserved at the Library. A click on the link will take you to the recording.

The Library holds other resources about danzón, including books, recordings, music scores and documentary films. This includes a documentary about the life and music of Israel López, known as “Cachao,” an extraordinary bass player and composer of danzón and mambo. “Salón México,” a 1949 film directed by Emilio Fernández — featuring a cabaret dancer who wins a danzón contest — is also part of the Library’s collection.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

October 5, 2023

Hundreds of Hebrew Manuscripts Now Online

The Library recently digitized some 230 historic manuscripts, some of them more than a thousand years old, in Hebrew and similar languages such as Judeo-Arabic, Judeo-Persian and Yiddish.

The collection, available online for researchers and the public for the first time, includes a 14th-century collection of responsa, or rabbinic decisions and commentary, by Solomon ibn Adret of Barcelona. He is considered one of the most prominent authorities on Jewish law of all time.

The digital project, funded by the David Berg Foundation, offers a highly diverse collection of materials from the 10th through the 20th centuries, including responsa, poetry, Jewish magic and folk medicine.

“The generosity of the Berg Foundation has enabled the Library of Congress to achieve a long-standing goal of making its rich collection of Hebrew manuscripts even more accessible to researchers,” said Lanisa Kitchiner, chief of the African and Middle Eastern Division. “The collection reflects an extraordinary manuscript tradition of immeasurable research value.”

Its existence and online presence, she added, are “both an inspiration and an invitation to admire, engage, draw upon and advance Jewish contributions to humanity from the 10th century onward.”

Italy in the 17th and 18th centuries is particularly well represented in the collection through numerous manuscripts on subjects including wedding poetry in Judeo-Italian and a considerable corpus on Kabbalah, or Jewish mysticism. Together, the newly digitized manuscripts offer a rich and often intimate glimpse into Jewish life over the centuries.

An illustration from “Order of Prayers Before Retiring at Night.” African and Middle Eastern Division.

An illustration from “Order of Prayers Before Retiring at Night.” African and Middle Eastern Division.Other highlights of the collection include:

The Passover Haggadah, also known as the“Washington Haggadah,” created in 1478 by Joel ben Simeon, a Hebrew scribe who is today considered one of the finest Jewish artists of the period.The 18th-century“Order of Prayers Before Retiring at Night,” a Hebrew miniature created in Mainz, Germany, in or around 1745.A fragment of unpublished poems by Solomon Da Piera (1342–c.1418), one of the last of the great Hebrew poets of Spain.A large fragment of an autograph manuscript by Moses b. Abraham Provençal from 1552.An unpublished novel in Hebrew written just after the first Zionist Congress in 1896.Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

September 28, 2023

An African American Family History Like No Other

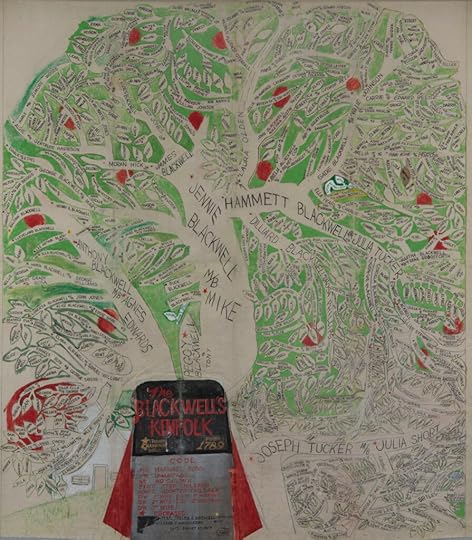

When the Library opens its new Treasures Gallery next year, displaying some of the most striking papers and artifacts that span some 4,000 years, one of them will certainly stand out: The Blackwell’s Kinfolk Family Tree.

It’s a dizzying, almost overwhelming piece of folk art that depicts the genealogical history of an African American family from Virginia. It’s 8 feet tall and 6 feet wide, contains more than 1,500 names spread out on curving trunks, branches and leaves and details family connections from 1789 to the 1970s. Its most famous member? Arthur Ashe Jr., the tennis great.

“The first time I saw it, my chin nearly dropped to the floor,” says Ahmed Johnson, the reference librarian in the History and Genealogy Section who worked with the family to donate the canvas. “And the fact that it’s an African American family that can trace its way back to the first ancestor? Slavery usually made that impossible.”

The Blackwell’s Kinfolk Family Tree as of 1959. Artist: Wilfred T. Washington. History and Genealogy Section.

The Blackwell’s Kinfolk Family Tree as of 1959. Artist: Wilfred T. Washington. History and Genealogy Section. The research, and the strikingly original canvas, comes from decades of work by the late Thelma S. Doswell, a D.C. school teacher and genealogist who wrote several books on the field. She got started early, being entranced by all the people she did not know at a family reunion.

“I met so many people I didn’t know,” she told a family newsletter in 1982. “I told my mother then that I had to know who these people were.”

She dug into files at the U.S. National Archives, state and local courthouses and antebellum census documents that listed names of the enslaved and sending detailed questionnaires to relatives. The genealogical work, as Johnson pointed out, succeeded in undoing what slavery was designed to do: dehumanize the people trapped in its clutches. Her work was admirable by any standard, Johnson said, but considering the historical hurdles faced by Black American families, it was exceptional.

“It’s always a hit every time we display it,” Johnson said. “People just can’t get over it.”

Doswell created the tree’s folk-art design and artist Wilfred T. Washington put ink to canvas, writing in names by freehand. It was unveiled at the 1959 family reunion.

“I was just a kid then,” says JoAnne Blackwell, president of the Blackwell Family Association, in a phone call from her home in New Jersey. “But it made such an impression on me and everyone else. It made me want to go back to the reunion every year.”

At the foot of the tree is a heavy black rectangle with “The Blackwell’s Kinfolk” written out by hand, in red ink and capital letters. “From 1789” is in gold lettering at the bottom right corner.

A gray rectangle lies directly below that, with an explanatory code in red and black lettering. It spells out the abbreviations used in the tree: “M/B” means marriage bond, “U/M” means unmarried, “N/C” means no children and so on.

The spreading tree above is massive and irregular — it sometimes resembles a meandering river breaking off into multiple streams and creeks rather than orderly tree branches marking the procession of time and generations.

Another striking feature: The tree follows the Blackwells’ matrilineal heritage, with women’s names as or more prominent than the men’s. JENNIE BLACKWELL is the huge name at the base of the trunk, from which everyone else descends, with a smaller notation of “M/B” MIKE below it.

Most names are in small, neat black lettering tucked within the boundaries of a green-bordered leaf. Jeanette. Alvin. Cleotis. Josephine. Cordelia. The name of Ashe, the tennis star, is marked out in gold leaf. Matching gold lettering at the bottom explains: “Tennis Champion – World.” (Ashe won five Grand Slam titles, playing singles or doubles.)

The Blackwell family. Photo: Courtesy JoAnne Blackwell.

The Blackwell family. Photo: Courtesy JoAnne Blackwell.“I chose the oak tree for its characteristic strength,” Doswell told a Washington Post reporter in 1987 in a feature story about the family tree.

Doswell hardly stopped in 1959. She kept at her research and, aided by enthusiastic family members filling out their own histories, completed two more family trees. Both are larger, more detailed and more straightforward in design. The second version, completed in 1971, has 3,333 names and is at the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History & Culture in Baltimore.

The third tree, completed in 1991, documents some 5,000 names and is at the Virginia Museum of History & Culture in Richmond.

Ultimately, Doswell was able to trace the family back to west Africa. The names of the first members put on a slave ship bound for the United States: Ama and her daughter, Tab. They were forced upon the Doddington and landed in Yorktown, Virginia, in 1735. There, her research shows, they were bought at an auction by slave owner James Blackwell.

The family’s newest historians, Richard Jones and Laura Blackwell Anderson, have digitized more than 6,200 family members onto a genealogical website service, making the history accessible to all family members.

The family is also planning their reunion next summer in Yorktown, so that they can visit the places where the family’s story began in North America nearly 300 years ago. It has been, as Doswell’s work makes clear, an epic journey.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

September 21, 2023

Missed You Much: The Library’s ASCAP Concert Bursts Back into Life

Pop hits, R&B grooves and Broadway anthems thumped through the Coolidge Auditorium Wednesday night as the We Write the Songs concert burst back into life for the first time in four years, featuring songwriters such as Jermaine Dupri, Jimmy Jam & Terry Lewis, Madison Love and Matthew West.

You wanted to hear Janet Jackson’s “Miss You Much” by the songwriters who put it together? A song from Broadway’s Tony Award-winning “Dear Evan Hansen” by the duo that scored it? Mariah Carey’s monster hit “We Belong Together” presented by co-writer Dupri?

This was your night — with the occasional asterisk. Dupri cheerfully noted his vocals were best kept to demo tapes and studio sessions. “I don’t let people actually hear me sing my demos,” he told an amused audience. “I actually, like, destroy the demos after I do it and the artist hears it.” He let backup singer Nicki Richards handle the soaring vocals.

The 90-minute, invitation-only showcase is an annual event (save for the recent COVID-caused gap) by the Library and the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers Foundation. It demonstrates to an audience heavy with members of Congress and Capitol Hill staffers, often in danceable fashion, why the rights of creative artists have to be protected. The Library is the home of the U.S. Copyright Office, which registers creative works for legal protection. ASCAP is the nonprofit organization that represents the individual artists.

“I have hugged so many legislators in the last half minute, I feel like running for office,” Paul Williams, the Academy Award-winning songwriter and ASCAP president, told the crowd as he helped open the show with Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden. “To us music creators, the Library is our Fort Knox. It’s the Fort Knox for our copyright.”

The show was composed of two-song sets by five artists: Dupri, Love, West, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul, and Jimmy Jam & Terry Lewis. Each was introduced by the congressional representative from their home district, which, in the above order, meant Georgia, California, Tennessee, New York and Virginia.

In between the hits were backstories about the songs and one-liners about the music business.

Pasek and Paul’s Broadway patter got laughs from the crowd by noting the wild spectrum of across-the-aisle groups that identified with their showstopper, “This is Me,” from “The Greatest Showman.”

“It was an LGBTQ anthem and also Trump played it at Camp David,” Pasek said.

Jimmy Jam (left) and Terry Lewis closed the show at the We Write the Songs concert at the Library. Photo: Kevin Silverman.

Jimmy Jam (left) and Terry Lewis closed the show at the We Write the Songs concert at the Library. Photo: Kevin Silverman.Pop music’s Love, who has written (or co-written) songs for Pink, Ava Max, Lady Gaga, Demi Lovato, Addison Rae and Jason Derulo, thanked her mom for making her take chess lessons in high school, which gave her the framework for “Kings & Queens,” a 2020 hit she co-wrote for Max.

“It’s a super female-empowerment anthem,” she told the crowd. “Sometimes a song comes together day-of, but other times it takes months and months of chipping away to make it perfect, and that was the case with this one.”

Singer and songwriter West, who sings “songs of hope for people who are feeling hopeless” in a Christian tradition, brought his guitar and a sense of humor onstage.

“A lot of people who don’t know contemporary Christian music, they think that we don’t celebrate platinum (records),” he said. “They think we only give out gold, frankincense and myrrh records.”

Just a few minutes later, Jimmy Jam & Terry Lewis were up there, closing the show with the thumping “Miss You Much,” with backup singer Jenny Douglas-Foote knocking out the lead vocals.

The crowd rose by the third note, as if on cue. Dupri bopped just across aisle from Love. Child swayed two rows down. Everyone sang along.

It was that kind of crowd. That kind of night.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

September 18, 2023

“Books That Shaped America” Series Starts

Some of the most important works by Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, Frederick Douglass, Willa Cather, Zora Neale Hurston and Cesar Chavez will be the focus of a new television series being produced by C-SPAN and the Library.

The 10-part series — “Books That Shaped America” — starts on Sept. 18 and will examine 10 books by American authors published over a span of nearly 250 years and that are still influential today. It will be hosted by Peter Slen, the longtime executive producer of C-SPAN’s BookTV.

“The idea that C-SPAN, working with the Library of Congress, has is to just start talking about books that matter,” said Douglas Brinkley, the author and presidential historian, in an onstage conversation last week with Librarian Carla Hayden, “and these are 10 to get us going.”

The series arises from a 2012 Library exhibit, “Books that Shaped America.” That exhibition was assembled by Library curators and specialists with the final selections determined by a public survey. The dozens of books on the list were chosen for their sustained impact on the nation, not whether they were the “best” or “most well-loved,” and the exhibit provoked plenty of conversation.

Likewise, viewers of this televised version will be able to weigh in with their own thoughts. This guide from C-SPAN provides background on the books and when they will be featured.

This time around, the Library didn’t select the books but it is helping to feature those being discussed. The audience will see Library copies of first editions authored by Paine, Douglass, Hurston, Mark Twain and others. More context will be given by the Library’s copies of rare photos, maps and correspondence.

” ‘Books That Shaped America’ will shine a light on a diverse group of books and authors whose skill with the written word and powerful storytelling left a lasting impression on our nation,” said Hayden. LOC press release.

The show will proceed chronologically, with the first book published in 1776 and the final one in 2002.

Zora Neale Hurston in 1938. Photo: Carl Van Vechten. Prints and Photographs Division.

Zora Neale Hurston in 1938. Photo: Carl Van Vechten. Prints and Photographs Division.There are two books from the 18th century, both central to the foundation of the country: “Common Sense” by Thomas Paine and “The Federalist” by Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay. The Library holds original copies of each.

The 19th century is represented by four works, three nonfiction and one novel. They are propelled by epic journeys of one sort or another as the nation fought over slavery and expanded relentlessly westward.

They are “History of the Expedition Under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark,” based on the journals kept by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark as their crew of explorers set out to cross the western part of the continent after the Louisiana Purchase. “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave” was the astonishing literary debut of a man who would become the nation’s clearest moral voice against the evils of slavery and white supremacy. “The Common Law” by Oliver Wendell Holmes is regarded as one of the great works of American law and legal reasoning.

The sole work of fiction from the century, often argued to be the great American novel, is “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” by Twain. The 1884 novel saw Twain put his good-hearted but socially outcast teen, who has faked his own death to escape his abusive father, in league with Jim, a Black man who has just escaped slavery, on a raft down the Mississippi River, both in search of freedom.

By the end of October, the show will move into the 20th century for three books, none of which address the world wars, Depression, civil rights movement, space race or any other of the major events of the century.

Willa Cather’s “My Ántonia” from 1918 is a beautifully written novel set in the frontier country of rural Nebraska, where orphaned young Jim Burden meets young Ántonia Shimerda. It’s a story of immigrant families on hardscrabble farms, the Great Plains rolling out before them. Jim and Ántonia’s friendship evolves over the years as the West and the Great Plains do, too.

“Their Eyes Were Watching God,” once nearly forgotten, is Zora Neale Hurston’s classic from the Harlem Renaissance. It’s a tale within a tale, as Janie Crawford, approaching middle age, returns to her Florida hometown and recounts her tumultuous life and relationships to a friend. It’s Janie’s story, but it’s really about the Black neighborhoods and towns of Florida in the early 20th century struggling to survive.

“Oftentimes novelists can get into the tone and tenor of your time and bring you into feel what it was like,” Brinkley said. “Some of the books on our list, particularly Zora Neale Hurston, is one that does that. It brings you there.”

The final book of the 20th century to make the list is something completely different — a set of economic and sociological essays by Milton and Rose Friedman. Published in 1980, “Free to Choose: A Personal Statement” is a treatment of the relative merits of free market economics. It spawned a 10-part series on public television, too.

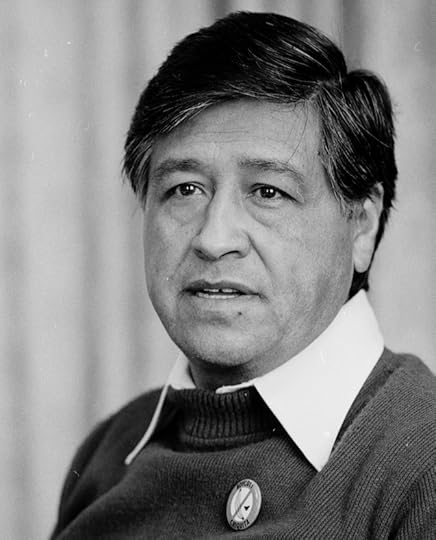

Lastly, placing a foot into the current century, there is “The Words of Cesar Chavez,” a 2002 anthology of works and speeches by the famed labor leader, who founded the organization that gained fame as United Farm Workers. He was also recognized with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Cesar Chavez in a 1979 interview. Photo: Marion S. Trikosko. Prints and Photographs Division.

Cesar Chavez in a 1979 interview. Photo: Marion S. Trikosko. Prints and Photographs Division.Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

September 11, 2023

John Phelan and the Sinking of the USS Oneida

This is a guest post by Candice Buchanan, writing with recently retired colleague Mark F. Hall. Both are/were reference librarians in the History and Genealogy Section.

My career started in a graveyard. I still do volunteer work there.

The graveyard in question is Green Mount, located on a hilltop on the outskirts of Waynesburg, Pennsylvania. This is in the far southwestern pocket of the state. My family has been there for several generations. As a teenager, I discovered my love of genealogy in no small part by walking past the rows of tombstones in this cemetery, fascinated by the shorthand accounts of lives buried beneath them.

The career that resulted from this youthful fascination is now to be working as a reference librarian in the History and Genealogy Section of the Library. On a recent visit back home, I walked through Green Mount — a dutiful affection keeps drawing me back — and I found my professional curiosity piqued by a white marble cenotaph in the Phelan family plot, which lies just a few steps from that of my family.

Most of the Phelan markers were made of brown sandstone, so the taller, whiter marker stood out. The inscription was also striking. The rest of the family had the basic names and dates. This one was a short story unto itself:

“Erected in the Memory of Lieut. John R. Phelan, U. S. N., Aged 23 Years & 4 Mo., who was lost on board the USS Oneida by a collision with the British steamer Bombay on the 24th day of Jan. 1870 in the Bay of Yokohama, Japan.”

The sinking of the Oneida, from a sketch by a survivor. Engraving: Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper March 19, 1870.

The sinking of the Oneida, from a sketch by a survivor. Engraving: Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper March 19, 1870.I was intrigued, though I had never heard of the Oneida or the Bombay or the international incident that followed, much less of John Phelan. But fellow genealogists will relate to the way in which each past person in our research seems to wait their turn to step forward so that their story might be told.

And so it was here.

I took my fascination back to the Library. With the collaboration of my colleague, Mark Hall, who specializes in maritime history, we dove into the long-ago international scandal that took young John Phelan’s life and that of so many others. Along the way, we created an in-depth research guide for readers and researchers to use. It’s filled with ship documentation, government records, books, magazines and newspapers that reported on the sinking. There are also strategies for how to apply genealogical research.

We are still digging, for John indeed stepped forward for his turn.

Briefly: The Oneida was a screw (propeller-driven) sloop with three masts and square sails. It was launched in 1861 and commissioned in 1862. The ship served in the West Gulf Blockading Squadron operations during the Civil War. Eight of her crew were awarded the Medal of Honor for actions during the 1864 Battle of Mobile Bay. After the war, the Oneida was recommissioned and assigned to the Asiatic Squadron.

Three years later, on Jan. 24, 1870, the ship departed the Japanese port city of Yokohama. Soon after, in the early darkness, the Oneida was hit by the Bombay, a British steamer. The Bombay sped on, offering no help. The Oneida went down in about 15 minutes, taking 115 sailors with her, among them Phelan. (Though the figure 125 was frequently reported, official government records identify 115.) His body was never recovered. Only 61 sailors survived.

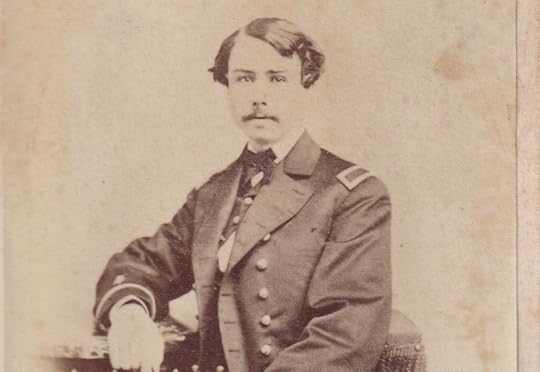

John R. Phelan, just promoted to the rank of ensign. Photo: S. G. Rogers. Waynesburg University, Paul R. Stewart Museum Collection.

John R. Phelan, just promoted to the rank of ensign. Photo: S. G. Rogers. Waynesburg University, Paul R. Stewart Museum Collection.The disaster sparked a heated controversy on the far side of the world. Who was responsible for the collision? Why didn’t the Bombay help? Could lives have been saved?

The diplomatic result was a split decision.

A British Court of Inquiry decided on Feb. 12, 1870, that the Oneida crew was responsible for the collision, but censured Capt. Arthur W. Eyre of the Bombay for not “waiting and endeavoring to render assistance.” A subsequent U.S. Court of Inquiry provided an opinion on March 2, 1870, which placed blame for both the collision and desertion on the Bombay, but did fault Capt. Edward P. Williams of the Oneida for failing to replace lifeboats that had been lost in an earlier typhoon.

And John Rogers Phelan, one of the many lost at sea?

Our research, built on a range of sources, shows that he grew up a child of promise, raised in financial comfort, with good family connections. He was the youngest son of John Phelan and Jane Walker. His father was a lawyer (who, by chance, studied the profession under my fourth-great-grandfather, Andrew Buchanan) and a politician. Both men served in the Pennsylvania state legislature. The Phelan and Buchanan families lived near each other on High Street in Waynesburg, within walking distance of the Greene County Courthouse.

The Phelans lived in, and added onto, one of the most impressive houses in town, the Whitehill Place (named for the original owner, who built it in 1808). It’s now a historic landmark and stands on the northwest corner of High and Cumberland streets.

Still, John did not choose to stay in these privileged surroundings and follow in his father’s profession. Instead, at 15, he entered the . He was successful in his career, being promoted from midshipman to ensign to master. He was in his early 20s then and had not married. If he kept a diary, it is lost. So far, we have not found any letters. We did find photos of him, one in his U.S. Naval Academy uniform and the other after he was promoted to ensign, in a photo book kept by his only sister, Mary (Phelan) Hogue, in the archives of Waynesburg University. She had been one of its earliest women graduates in 1864.

In the last surviving ship log of the Oneida, there are regular written reports of weather and conditions in what we think is Phelan’s handwriting and with his signature, but we are still working to confirm that.

John Phelan’s signature in the ship’s log. We believe it to be in his hand, not filled in by another colleague, but are still working to confirm this. U.S. National Archives.

John Phelan’s signature in the ship’s log. We believe it to be in his hand, not filled in by another colleague, but are still working to confirm this. U.S. National Archives.And then the record goes silent. The Oneida is hit and sinks.

In the 1870 U.S. Census Mortality Schedule, John’s family reported him as drowned. More than a century later, the family’s grief can still be documented in that cenotaph (and its detailed inscription) that caught my attention — it’s so strikingly different from those of the rest of the family. John’s death was clearly shocking and outrageous to them, no doubt exacerbated by his body never being found.

For several other Oneida sailors, we have found family papers. One of the men lost at sea had supported his mother, and she was granted a pension. Included in the paperwork are his letters home from service. They are heartbreaking to read in the aftermath. These and papers from other Oneida sailors can be found in our research guide.

This project has been engulfing. We plan to do a presentation to share some of the individual case studies because they are unique and incredible, plus they reveal research paths that can be learned from as examples.

John Phelan was the starting point for us. He stepped forward and caught our attention. Now he’s introducing us to each of his shipmates as well.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

September 8, 2023

Proclaiming a New Nation: The Library’s Copies of the Declaration of Independence

After the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, the delegates wanted to spread word of their momentous action throughout the Colonies as quickly as possible.

The president of Congress, John Hancock, ordered the document to be printed as a broadside, a single-sheet format popular in that era for quickly distributing important information.

That first printing of the Declaration today is known as the Dunlap Broadside, named for the man who produced it for Congress, Philadelphia printer John Dunlap. Original copies are extremely rare: Only about two dozen survive, most of them held by institutions in the U.S. and a few by British institutions and private individuals.

The Library of Congress holds two copies. One, part of the George Washington Papers in the Manuscript Division, survives only in incomplete form: The text below line 54 is missing. The second copy, held by the Rare Book and Special Collections Division, is complete.

In keeping with congressional resolutions, Hancock on July 6 had dispatched one of Dunlap’s newly printed broadsides to Gen. Washington, then in New York with his troops, and asked him to “have it proclaimed at the Head of the Army in the Way you shall think most proper.”

On the evening of July 9, with British warships visible offshore, Washington assembled his troops and had the Declaration read to them from the broadside now in the Washington papers. They were, the Declaration asserted, no longer subjects of a king. Instead, they were citizens and equals in a new democracy.

Later that night, to Washington’s dismay, a riled-up crowd pulled down an equestrian statue of King George III, located at the foot of Broadway on the Bowling Green. Ahead lay seven years of war and, eventually, the independence proclaimed to Washington’s troops from a broadside now preserved at the Library.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

September 6, 2023

Poetry in National Parks: Ada Limón’s New Project

Ada Limón’s signature project as the U.S. Poet Laureate, “You Are Here,” will feature two major new initiatives: an anthology of nature poems and poetry installed as public art in seven national parks.

“I want to champion the ways reading and writing poetry can situate us in the natural world,” Limón said. “Never has it been more urgent to feel a sense of reciprocity with our environment, and poetry’s alchemical mix of attention, silence, and rhythm gives us a reciprocal way of experiencing nature — of communing with the natural world through breath and presence.”

A new anthology, “You Are Here: Poetry in the Natural World,” will be published by Milkweed Editions in association with the Library next spring, on April 2. It will feature original poems by 50 contemporary American poets, including former U.S. Poet Laureate Joy Harjo, Pulitzer Prize winner Diane Seuss, and PEN/Voelcker Award winner Rigoberto González, who reflect on and engage with their particular local landscape. As Limón said, “With poems written for vast and inspiring vistas to poems acknowledging the green spaces that flourish even in the most urban of settings, this anthology hopes to reimagine what ‘nature poetry’ is during this urgent moment on our planet.”

“You Are Here: Poetry in Parks,” an initiative with the National Park Service and the Poetry Society of America, will feature site-specific poetry installations in seven national parks across the country. These installations, which will transform picnic tables into works of public art, will each feature a historic American poem that connects in a meaningful way to the park and will “encourage visitors to pay deeper attention to their surroundings,” according to Limón.

Participating national parks are:

Cape Cod National Seashore (Massachusetts)Cuyahoga Valley National Park (Ohio)Great Smoky Mountains National Park (North Carolina and Tennessee)Everglades National Park (Florida)Mount Rainer National Park (Washington)Redwood National and State Parks (California)Saguaro National Park (Arizona)Limón will travel to each of the parks in the summer and fall of 2024 to unveil the new installations.

“In this moment when the natural world is making headlines, Ada Limón’s signature project will help us connect more personally to America’s greatest parks as well as show how the poets of our time capture the natural world in their own lives,” said Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden. “It also extends our laureate’s engagement with federal agencies and literary partners, to promote poetry to the nation.”

Ada Limón. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Ada Limón. Photo: Shawn Miller.Limón has a number of major collaborations under way to share poetry with the public. In June, she returned to the Library to reveal “In Praise of Mystery: A Poem for Europa,” which she wrote for NASA’s Europa Clipper mission. Limón’s poem will be engraved on the spacecraft that will travel 1.8 billion miles to explore Europa, one of Jupiter’s moons. The poem is part of NASA’s “Message in a Bottle” campaign, which has gathered more than 450,000 signatures from people around the world signing on to the poem. The campaign will run through 2023.

For National Poetry Month, Limón has served as the guest editor for the Akcademy of American Poets Poem-a-Day series in a first-ever series collaboration between the Academy and the Library.

Limón was born in Sonoma, California, in 1976 and is of Mexican ancestry. She is the author of six poetry collections, including “The Carrying,” which won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry in 2018. began her first term as poet laureate in September 2022. During her term, she participated in two events hosted by the first lady of the United States for the National Student Poets Program and for the state visit with Brigette Macron, wife of the president of France. Limón also participated in an event hosted by Beatriz Gutiérrez Müller, wife of the president of Mexico, for the North American Leaders Summit in Mexico City, and she participated in a conversation with Argentine and Brazilian poets for the Library’s Palabra Archive.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

September 2, 2023

Fair Winds and Following Seas to You, Jimmy Buffett

Jimmy Buffett, whose “Margaritaville” was inducted into the National Recording Registry this year, died yesterday at age 76. He was surrounded by his family, friends and his beloved dogs, his family announced on social media. There was no mention of the cause.

It was a shock to his millions of fans across the globe, as the vibrant, still-touring Buffett was not publicly known to be ill. He had performed in concert as recently as May.

I interviewed him in late March for the NRR honors. The man was both the picture of health and tickled by the recognition, as his laid-back songs were not the type that tended to get awards, he chuckled.

So he happily joined us via a streaming platform and told the familiar story of how he wrote the hit that changed the last four decades of his life and helped make him one of the wealthiest entertainers of his generation.

It was the early 1970s and he was day drinking in Austin, Texas, after a rough night out with his friends Willie Nelson and Jerry Jeff Walker. He ordered a margarita – on the rocks with salt – and it hit the spot.

“I started writing it right there on a napkin like you hear about,” he said. A friend took him to the airport for his flight back to Miami, from which he’d shuffle a rental car back down to Key West for a friend who was in that business. (He also needed the free transportation.) A traffic jam ensued on the Seven Mile Bridge and, stuck for an hour or so, he finished the song.

“I got to Key West and I was working in a little club on Duval Street called Crazy Ophelia’s. And I went in and I had to work that night and I played the song. People liked it! I went, ‘Wow, this is pretty good.’ And you know, it was fresh, it was probably, you know, six hours old …. It was maybe even four years before it got recorded (in 1977). It was just part of my repertoire that people liked as I was going around as a performer.”

He was very familiar with the Library, having performed here in September 2008 when his friend Herman Wouk was honored with the Library’s first Lifetime Achievement Award for the Writing of Fiction (today known as the Prize for American Fiction). In one of those “only at the Library” moments that demonstrate the sweep of the place, Buffett spoke, and then sang, just before Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg spoke and read from Wouk’s writing. (Imagine that advertising card: “Tonight Only! Herman Wouk! Jimmy Buffett! Ruth Bader Ginsburg!”)

The announcement of Buffett’s passing. Image from Buffett’s website.

The announcement of Buffett’s passing. Image from Buffett’s website.This March, ours was a simple, half-hour interview. He wore a baseball cap, an upbeat smile and a camo tee shirt. It came with a sweet nostalgic undertone, at least for me.

How I had idolized this man when I was a teenager! How I had memorized every line of every song!

Buffett was nearly two decades older but, like me, grew up in Mississippi, him down there on the Gulf Coast. I was a seventh generation Mississippian, living outside a small town in the middle of the state. I was very much into music and very much into not living the rest of my life outside a small town in the middle of Mississippi.

And there he was! A Mississippi kid, living the dream in the Florida Keys and the Caribbean! Writing romanticized, chilled-out songs about the seas, the islands, roaming the planet, another life in another world.

I must stress this was before “Margaritaville,” before he was on the cover of Rolling Stone, before Parrotheads, before the restaurants and “Cheeseburger in Paradise.” I was “A White Sport Coat and a Pink Crustacean.” I was “A1A.” I even wrote to rare record shops, getting a copy of his first album, “Down to Earth.”

After college, I took a job at a newspaper on the east coast of Florida, right by the ocean, in no small part because my hero, Jimmy Buffett, had gone to Florida, too. I eventually became a foreign correspondent and roamed the planet, my wanderlust having been kindled by listening to Buffett as a teen.

And so here we were this March, both of us now old guys.

We played back home for a minute or two. Because it’s a very small state it turned out we had mutual friends. He said that when in Washington he often ate at the Bethesda Crab House. It’s a mile from where I live, we eat there as well, and I said I’d keep a lookout for him. The man is worth some $600 million, thanks to his ceaseless touring and ever-expanding merchandising of “Margaritaville,” but you wouldn’t have known it that day. We might as well have been two Magnolia State refugees who happened to bump into one another on adjacent bar stools at Sloppy Joe’s in Key West.

He was working on a new album about his time as a busker in New Orleans and urged me to buy it when it came out. He was planning a concert in the D.C. area and told me to come on out and introduce myself. It had the gist of sincerity to it, not just a “let’s have lunch” pleasantry that people say but of course don’t actually mean. (And, even if it was, it was kind of him to say so.)

So, like the rest of you, I was stunned and saddened this morning when I heard the news. The cover of the “Changes in Latitude” album popped up before my mind’s eye. “Trying to Reason with Hurricane Season” played in my head, his soft tenor opening the lyrics:

Squalls out on the Gulf Stream

Big storm’s coming soon

Passed out in my hammock

And God, I slept till way past noon

Fair winds and following seas to you, Jimmy Buffett.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 31, 2023

The Scenic Route? The Library’s 117-foot Map from 17th-century Japan

—This is a guest post by Dylan Carpenter, an intern in the Office of Communications this year. It also appears in the July-August issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Long before the advent of Google Earth and glossy travel books, ancient cartographers used pictographic maps to guide travelers through the world around them. Many of these are held in the Geography and Map Division.

Among the most remarkable of these navigational aids is the Tokaido bunken-ezu, a 17th-century Japanese map charting the route from what is now Tokyo to the then-capital of Kyoto. The map not only provides valuable insights into Japan’s rich cultural heritage but also offers a fascinating glimpse into the world of mapmaking before the age of digital technology.

One thing that makes the Tokaido bunken-ezu truly unique is its massive size. The map, painted on two scrolls, measures about 117 feet in length, dwarfing most other pictorial maps of its time and even more contemporary counterparts.

The Tokaido bunken-ezu, created as an everyday guide for a road trip, today is also recognized as a great cultural artifact: It is considered a masterpiece of Japanese mapmaking.

Cartographer Ochikochi Doin surveyed the 319-mile route from Edo (now known as Tokyo) to Kyoto in 1651, and the well-known artist Hishikawa Moronobu gave form to his findings via this pen-and-ink illustrated map in 1690.

The map renders five main stretches on the Tokaido road, providing a detailed account of the amenities, landmarks and terrain set against images of mountains, rivers and seas.

The map shows the 53 stations, or post towns, that lined the route to provide travelers with lodging and food. Famous landmarks such as Mount Fuji and Mount Oyama are depicted from multiple angles and various stations. Travelers walked the road in groups of various sizes.

“A road of a thousand miles comes from a single step,” a famous Japanese proverb goes.

Centuries ago, adventure awaited those who took that first step on the path leading from Edo. Looking at this great map today, it’s easy to appreciate the travelers who made the journey — and the mapmakers who helped make it possible.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers