Library of Congress's Blog, page 21

August 28, 2023

The March on Washington, Revisited

It’s 30 minutes before midnight on June 1, 1963. Martin Luther King Jr. is on the phone.

For eight long years, ever since the Montgomery bus boycott with Rosa Parks, he’s been the nation’s most visible civil rights leader. Freedom Riders, sit-ins, voting rights volunteers spreading out across the South. The waves of terrorist violence. His house has been bombed. He’s been arrested. He wrote “Letter from Birmingham Jail” two months ago.

“We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed,” he wrote. And: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

Now hundreds of protests are taking place across the country. Now the wildfire is spreading. In the phrase he will make famous, the fierce urgency is indeed now.

“We are on a breakthrough,” he’s telling fellow organizers in this conference call, as recounted from FBI surveillance tapes in Taylor Branch’s Pulitzer Prize-winning history, “Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954-63.”

“We need a mass protest,” he’s saying. The place? Washington.

Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders in the front row of the march, as news crews ride on a truck just in front of them. Photo: Warren K. Leffler. Prints and Photographs Division.

Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders in the front row of the march, as news crews ride on a truck just in front of them. Photo: Warren K. Leffler. Prints and Photographs Division.Less than two weeks later, a white supremacist assassinates Medgar Evers, the NAACP leader in Mississippi, in his driveway.

Now the wildfire is roaring. The “mass protest” King envisioned spawns into the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The date selected is impossibly early: Aug. 28. It’s crazy. It’s less than three months away. And yet somehow organizers, anchored by union official A. Philip Randolph and veteran activist Bayard Rustin, pull together a march of some 250,000 people from across the nation — the vast majority of them Black — creating one of the most moving, consequential moments in American history.

“Freedom Now,” read the hats of many marchers who ride by bus for hours to get here. Spirits are high. Men wear suits. Women wear pearls. Everyone laughs, a little giddy. The heat stays in the low 80s; there’s a slight breeze. Star power? How about Josephine Baker, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Paul Newman, Harry Belafonte, Marlon Brando, Sidney Poitier, Sammy Davis Jr., Bob Dylan, Mahalia Jackson, Marian Anderson, Joan Baez, Odetta?

King’s concluding speech of the rally, from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial to a sea of listeners stretching as far back as the eye can see, is “I Have a Dream.” It is one of the dazzling moments in American rhetorical history, certainly one that led to his Nobel Peace Prize the next year. It is preserved in the Library’s National Recording Registry.

That afternoon, he seems to sense the moment even as it is happening:

“I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation,” are some of the first words he says.

Many parts of that day are preserved at the Library. The papers of Rustin. The papers of Randolph, who was the first speaker of the day. The papers of Rosa Parks. The papers of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Those of legendary activist James Forman. The work by photographer Warren K. Leffler. And so many others.

They all document an amazing accomplishment, these peaceful crowds, this energy.

People arriving for the speeches at the Lincoln Memorial at the conclusion of the march. Photo: David L. Harris. Prints and Photographs Division.

People arriving for the speeches at the Lincoln Memorial at the conclusion of the march. Photo: David L. Harris. Prints and Photographs Division.But it is not a perfect day.

Parks doesn’t get to speak; no woman is allowed any significant time on stage during the main program. James Baldwin, the eloquent novelist, the gay icon, the man who has spoken truth to power in any forum anywhere, was not invited to speak for fears he will be too incendiary. Malcolm X has derided the proceedings as a “circus,” too inclusive of too many other groups and causes. President Kennedy, who is sympathetic to the cause, meets with King and others after the march in the Oval Office, but does not speak at the event and doesn’t stand next to King in the group photo. (This may be the clearest example of how dangerous King was seen to be at the time.)

Still, the magic. It can’t be denied.

King had given variations of his “I Have a Dream” speech before, but this time, broadcast on national television, it seems injected into the national consciousness.

“Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!” he shouts at the conclusion, quoting lines from a Negro spiritual, to a whirlwind of emotion from the crowd.

And then.

Part of the March on Washington delegation that met with the president: (l to r): Whitney Young, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.,John Lewis, Rabbi Joachim Prinz, A. Philip Randolph, President John F. Kennedy. Photo: Warren K. Leffler. Prints and Photographs Division.

Part of the March on Washington delegation that met with the president: (l to r): Whitney Young, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.,John Lewis, Rabbi Joachim Prinz, A. Philip Randolph, President John F. Kennedy. Photo: Warren K. Leffler. Prints and Photographs Division.And then everyone goes home to the same terrorist violence they had left behind, because there is another America that sees King’s dream as a nightmare.

Less than three weeks later, four Black girls will be killed by white supremacists in the bombing of a Black church in Birmingham, Alabama. Kennedy will be assassinated in November. Freedom Summer and the murder of three civil rights workers in Mississippi lies in the next turning of the calendar. In 1965, the shooting death of voting rights activist Jimmie Lee Jackson by an Alabama policeman will spark the Selma-to-Montgomery March and the passage of the Voting Rights Act.

And then.

And then King will be shot dead by a white supremacist on a motel balcony in Memphis on April 4, 1968, less than five years after the March on Washington. He was 39.

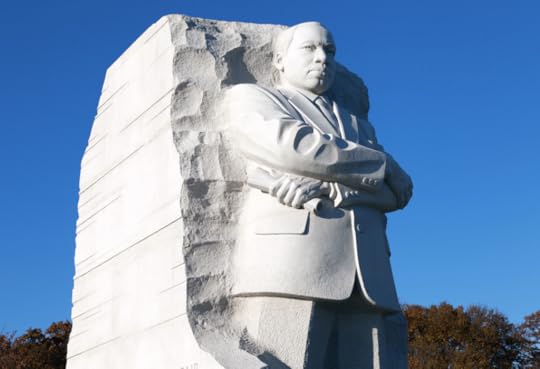

His memorial, a granite sculpture emerging from a rock face, now stands on the Tidal Basin. It is a short walk from where an inscription marks the spot of his speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, given in the fading light of that summer afternoon in 1963, when the March promised a dream for so many.

The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial in Washington, D.C. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial in Washington, D.C. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 24, 2023

My Job: Cheryl Regan

Cheryl Regan is a veteran of the Library’s exhibits office, bringing the treasures of the world’s largest library to the public. Here, she answers a few questions about her work.

Describe your work at the Library.

I am a senior exhibition director in the Exhibits Office — the office charged with planning, developing and mounting Library of Congress exhibitions, both on-site and online. I began working at the Library in 1991, hired on as a picture researcher for the “City of Magnificent Distances: The Nation’s Capital” exhibition, and I never left.

I have directed exhibitions, both national and international in scope, and worked collaboratively with recognized scholars and in-house curators and staff, always with the institution’s mission in mind of providing access to the collections.

The audience for exhibitions at the Library is impressive. Over 30-plus years, I have seen attendance swell from the tens of thousands to well over a million for more recent offerings. But it is working with the amazing Library staff and the phenomenal collections that has made mine a truly great job.

How did you prepare for your job?

As I was preparing to start school as a fine arts major (painting) at Carnegie Mellon University, my father assured me of his whole-hearted support — but also asked that he not have to support me for the rest of his days.

So, as an undergraduate I began interning in museums. That led to my first job at the Carnegie Museum of Art, one of many museum jobs and subsequent internships I held in Pittsburgh; Rochester, New York; Charlottesville, Virginia; and Washington, D.C.

After three years of working as an assistant to the director of Carnegie Mellon Art Galleries, the director encouraged me to enter graduate school. I received a master’s in art history at the University of Virginia in 1991, then came to the Library.

What are some of your standout projects?

So many, really. We mounted an exhibition examining the life and work of Sigmund Freud that garnered worldwide attention and allowed me to work with renowned historians and thinkers. The Lewis and Clark and a century of Western exploration exhibition sparked what my love affair with maps. “Creating the United States” — with its message of creativity, conflict and compromise that went into crafting this nation’s founding documents — drew a broad audience, including members of Congress.

Working with colleagues on “The Civil War in America,” “Jacob Riis: Revealing ‘How the Other Half Lives,’ ” “Echoes of the Great War: American Experiences of WWI” was particularly rewarding. I helped develop and curate the Library’s “American Treasures” exhibition during its 10-year-run, and now my career has come full circle: We currently are preparing “Collecting Memories: Treasures from the Library of Congress,” which promises to be a spectacular showcase for collections from all corners of the Library.

What are some of your favorite collection items?

I have direct contact with thousands of collection items, and I don’t think there is a custodial or collecting division that I haven’t worked with.

I remember giving tours of “With Malice Toward None: The Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Exhibition” and choking up reading the last lines of Lincoln’s first inaugural address. The collections are amazing for what they represent and the information that they contain, but the awe I feel in front of objects that were in the hands of Lincoln or Meriwether Lewis or some anonymous photographer doesn’t ever diminish. These objects bore witness to their time — that is so powerful, and it’s why I do the work that I do.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 22, 2023

The Library Reimagined, with You in Mind

This story also appears in the July-August edition of the Library of Congress Magazine.

First-time visitors to the Library of Congress campus often ask the same question: Where do I even begin?

It’s easy to see why.

For many, it’s awe of the historic Jefferson Building that stops them. One of the most beautiful spaces in America, the Jefferson is a head-spinning whirl of murals, marble, sculpture, stained glass and soaring architecture.

For others, it’s the lure of the institution’s massive collections.

The Library holds an endless array of fascinating things, more than 175 million items that form the most comprehensive collection of human knowledge ever assembled. Together, those millions chronicle millennia of world history and culture.

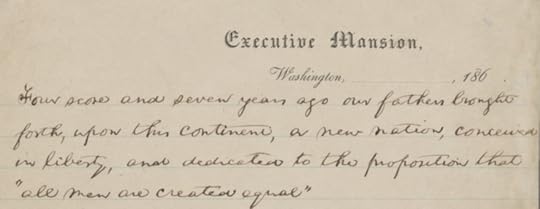

Here is Abraham Lincoln’s original draft of the Gettysburg Address, neatly written on Executive Mansion letterhead. There is an ancient fragment of the “Iliad,” one of the greatest and earliest works of Western literature. The world’s first selfie. The world’s largest collection of films. The papers of 23 presidents. The map Lewis and Clark carried across the continent. A perfect copy of the Gutenberg Bible. Rosa Parks’ papers. Original Beethoven music manuscripts. That crystal flute, and on and spectacularly on.

The Great Hall

in the Jefferson Building. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith.

The Great Hall

in the Jefferson Building. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith.So, where do you begin?

If you ask a librarian, the answer lies in finding more ways to connect visitors with collections and programs that match their interests.

“At the Library of Congress, we want you to make a make a personal connection, to find yourself here and explore your own history, so you can tell your own stories,” Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden said. “We want to transform the visitor experience for the people who visit the Library of Congress in person and the millions more who access us online.”

Over the next few years, the Library will deliver a new experience, “A Library for You,” to bring that vision to life.

“By opening windows to our world,” Hayden said, “by sharing more of the Library’s treasures with the public and engaging children and young adults in its collections, we will greatly increase Americans’ access to knowledge.”

The opening paragraph of Lincoln’s first draft of the Gettysburg Address. Manuscript Division.

The opening paragraph of Lincoln’s first draft of the Gettysburg Address. Manuscript Division.The multiyear A Library for You initiative has several key elements:

An orientation gallery. Once the project is completed, visitors will enter the Jefferson Building through an orientation gallery located on the ground floor. There, they will discover more about the Library’s history, mission, collections and programs.The gallery will center around one of the Library’s foundational and most significant holdings: the personal library of Thomas Jefferson. The Library at one time was located in the U.S. Capitol. During the War of 1812, the British sacked Washington, D.C., and burned the Capitol, destroying most of the volumes in the Library. Jefferson sold his books to the government in 1815 as a replacement — the foundation of the modern Library of Congress.

The gallery will showcase the art and architecture of the Jefferson Building itself, with immersive and interactive experiences that explore the magnificent space. Visitors also will have an opportunity to see behind the scenes into the original book stacks.

The David M. Rubenstein Treasures Gallery. This new gallery will offer visitors a window into the Library’s collections, creating a public space where visitors can see firsthand some of the fascinating and special items held by the Library in rotating, thematic exhibitions.The inaugural installation, centered on the theme of remembrance, will include a draft of the Gettysburg Address handwritten by Lincoln, original handwritten lyrics from “The Sound of Music,” Maya Lin’s original drawings for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, original artwork by Stan Lee and Steven Ditko for the Spider-Man comic, President James Madison’s crystal flute, 4,000-year-old cuneiform tablets and more.

A working image of the new teen center. An educational research studio. The Library’s new education center, called The Source, will provide children, ages 8 years and older, and their families with a space within the Library to discover how information and research can nourish curiosity, creativity and change. The space also will host teens with special programming and volunteer and internship opportunities.

A working image of the new teen center. An educational research studio. The Library’s new education center, called The Source, will provide children, ages 8 years and older, and their families with a space within the Library to discover how information and research can nourish curiosity, creativity and change. The space also will host teens with special programming and volunteer and internship opportunities.Through fun hands-on activities and interactive experiences, children will explore the Library’s resources, while actually modeling the research process by finding information, analyzing primary sources and considering perspectives.

“The Source will introduce young visitors to the process of research, inviting them to practice critical skills, such as primary source analysis while allowing them to consider how research can use materials from the past to shape the future,” said Shari Werb, the director of the Library’s Center for Learning, Literacy, and Engagement. “That is what will make it unique from other spaces.”

The Jay I. Kislak Gallery of the Early Americas. In 2004, businessman Jay I. Kislak donated nearly 4,000 artifacts, paintings, maps, rare books and documents to the Library. This extraordinary material chronicles the history of the early Americas, from the ancient Maya to the encounters between European explorers and Indigenous peoples.The collection spans 2000 B.C. to the 21st century. There are pre-Columbian artifacts such as a panel relief of a ballplayer from the ruined Maya city of La Corona. Manuscripts written by important figures like Queen Isabella of Castile, King Philip II of Spain and explorer Hernán Cortés. Rare manuscript letters and annotated books by Founding Fathers George Washington and Jefferson. And there are the creative endeavors of 20th-century artists, including a unique series of watercolors depicting Popol Vuh, the Maya creation myth, by Mexican muralist Diego Rivera.

A working image of the new Kislak gallery.

A working image of the new Kislak gallery.A new exhibition, “Voices of the Early Americas,” will highlight key pieces of the Kislak collection — many of them displayed for the first time through a state-of-the-art, transparent artifact wall.

Food, drink and a view. On the Jefferson Building mezzanine level, a new café will invite visitors to linger and admire the beautiful Great Hall and the grand views of the U.S. Capitol, located across the street.The new features of A Library for You are scheduled to open over the next few years, beginning in spring 2024 with the Rubenstein treasures gallery, followed by the orientation gallery, café and education center.

A transformation of this scale and with a mission this vital requires a dynamic collaboration between the public and private sectors.

At this moment of great opportunity for the Library of Congress, both the U.S. Congress and the private sector have stepped forward to help ensure that the nation’s library can extend its reach and democratize access to the Library’s vast collections and resources.

“At the Library of Congress, we want you to make a personal connection, to be able to find yourself here and explore your own history, so you can tell your own stories,” Hayden said. “You can look up maps from your hometown. You can locate your grandfather’s store and use census data and genealogical resources to research your family tree.

“We are focused on expanding our collections to reflect all the people we serve and to make them easy to access because they belong to you.”

August 18, 2023

Q & A: Jessica Tang

Jessica Tang is a library technician in the Asian Division.

Tell us about your background.

My parents are Chinese American immigrants, and I was born and raised in Fairfax County, Virginia. I went to McLean High School, played clarinet in the marching band and attended Hope Chinese School in Annadale on the weekends.

Afterward, I studied elementary education at James Madison University. At the time, it was one of my dreams to teach children. Another dream, which I viewed as less attainable, was to become a clarinetist in a U.S. Army band. One day, I decided to just go for it and auditioned. The Army accepted me.

What brought you to the Library, and what do you do?

I realized how great it is to work in a library after falling off an obstacle tower in Army basic combat training and breaking my shin in half — three days from graduation.

I begged my drill sergeants and my commander not to chapter me out of the Army, since I’d already won an audition and was so painfully close to attaining my dream. Because of that, the Army put me in a trainee rehabilitation center, where they kept me for another 10 months.

Rehab is a tough place for trainees. We couldn’t leave the building or have family visitors or access to phones or computers. I was cut off from the world.

But, luckily, the rehab center had a library. Its lead librarian sussed me out from day one as a bibliophile and persuaded our drill sergeants to let me work in that oasis.

That’s where I first experienced just how life-changing a library can be. We had trainees who came from tough backgrounds and had never read a book in their lives. I would introduce them to any page-turner that piqued their interest and, within a month or two, they’d be devouring classics.

Inspired by this experience, I started working at public library after rehab. Then, last year, a friend texted me a posting for a job in the Asian Division. It was such an ideal fit for me, so I applied, and now I’m here!

Another factor that pushed me to library work was my own experience as a researcher. I write historical fiction, and much of my world-building research relies on old medical records collected in local libraries. Sometimes, my records requests would turn out to be “not on the shelf,” and each time I would be so disappointed. Often, the staff wouldn’t take a second look for me.

Now that I’m on the other side of the counter, I’m passionate about doing everything possible to hunt down missing items. You never know how much of a researcher’s work depends on them.

What are some of your standout projects?

First, I’m very happy to say that I’m part of a unique team of multilingual technicians in the Asian Division.

Right now, I’m helping to sort and inventory more than 40,000 items in the division’s Pre-1958 Chinese Collection. It is full of records in both Chinese and English with different types of romanization that makes it challenging to navigate. We often receive requests that are difficult to serve because of the confusing records.

And, physically, many of the collection items are old and fragile, so I’m also working on rehousing them. In short, I’m trying to make the collection easier to use for everyone who wants to explore these books.

What do you enjoy doing outside of work?

On weekends and holidays, I serve as a clarinetist and fifer in the U.S. Army’s 29th Infantry Division Band. I also enjoy letterboxing, which is a treasure-hunting hobby. Basically, you carve rubber stamps that can be inked and pressed in journals, then hide them in cool places for others to find. You also carry a journal of your own to collect stamps that other people have hidden.

What is something your co-workers may not know about you?

I’m into graphology, or handwriting analysis. I can tell you things about your personality based on a sample, like your degree of extroversion, pessimism or self-discipline. Of course, it’s all pseudoscientific, so take my feedback with a hunk of salt!

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 15, 2023

George Saunders Accepts the Library’s Prize for American Fiction

Novelist, short-story writer and essayist George Saunders was awarded the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction Saturday evening in one of the final sessions of the 2023 National Book Festival, conferring a lifetime honor on a versatile writer whose most famous book cast one of Washington’s most famous residents in a surreal light.

“This year’s winner is George Saunders, and you might as well clap right now,” Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden told the enthusiastic crowd before giving the winner’s impressive resume.

Saunders, the author of 12 books and a professor of creative writing at Syracuse University, won the 2017 Man Booker Prize for “Lincoln in the Bardo,” a fantastical take on actual visits by the 16th president to a Georgetown cemetery where the body of his dead son was held in a crypt during the Civil War. Saunders, 64, has also been awarded the PEN/Malamud Award for Excellence in the Short Story and received fellowships from the MacArthur and Guggenheim foundations.

Saunders cheerfully posed for pictures with Hayden before pretending to drop the crystal trophy, drawing a laugh from the audience in the convention center’s mammoth Ballroom A. In the subsequent conversation with Clay Smith, the festival’s literary director, Saunders discussed his career of writing short stories, nonfiction, essays and his stunning novel about Lincoln’s visit to Oak Hill Cemetery one night to visit the corpse of child Willie, who died in 1862 at the age of 11 of typhoid fever. More than 160 ghosts comment, narrate, argue and debate his presence in a cacophony of voices.

Saunders said he first heard the story about the grieving Lincoln during a visit to Washington in the 1990s but thought the material wasn’t in his wheelhouse. Two decades later, a more intimate tour of the cemetery spurred him to take on the challenge of writing about one of the most well-known, well-loved and mythologized of American presidents. “I just stood there (in front of the mausoleum) for a couple of minutes and something said to me, ‘If you can’t write this, and you don’t try it, then you have to stop saying you’re a writer.’ It’s such a beautiful, profound story, and if your excuse is, ‘I don’t have the depth to do it,’ just quit.”

It was hardly an easy process; he was bedeviled by self-doubts about taking on such a different, emotionally laden project: “Every day, it was, ‘Is it cheesy yet?’ ”

George Saunders on stage during the National Book Festival. Photo: Shawn Miller.

George Saunders on stage during the National Book Festival. Photo: Shawn Miller.Polished on stage, comfortable in jeans, shirt, loose tie and a blue sport coat, Saunders was eloquent on the importance of writing and reading fiction. It can be both a balm and a gentle nudge toward acceptance and love during difficult times, he said, as we live in a world that is often beyond our intellectual and emotional grasp.

“I feel like we went off base a bit when we started treating literary fiction as a kind of an interesting side gig, you know, something that some English nerds do,” he said. And, a moment later: “Fiction does something just to remind us in the tiniest way that the real big truths of the world evade us mostly, except maybe in moments of love, tragedy, crisis,” he said. “Fiction can be a way of, sort of, in the safety of our own home, re-creating such moments, so that we remember that we have a greater ability to empathize with other people, even our enemies, than we thought we did.”

The Library’s Prize for American Fiction, begun under a slightly different name in 2008, seeks to recognize writers whose works convey something essential about the American experience with a unique style and heft. Previous winners include Toni Morrison, Philip Roth, Louise Erdrich, Isabel Allende, Don DeLillo and E.L. Doctorow. Last year’s winner was Jesmyn Ward.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 10, 2023

National Book Festival This Saturday!

This Saturday, when book lovers descend on the D.C. convention center, many will no doubt lose themselves in a good book (or two). But if they also find themselves in the process, the festival’s carefully crafted lineup will have achieved its mission.

In its 23rd edition, the National Book Festival’s theme is “Everyone Has a Story” — meaning those attending as well as onstage. From 9 a.m. to 8 p.m., more than 70 authors will engage readers on topics across American life and beyond.

Festival-goers will encounter poetry, history, memoir, horror, sci fi, children’s lit, popular fiction, literary fiction, food, social justice and science. The list goes on. The breadth of offerings guarantees every type of reader will hear conversations reflecting their own stories or deepening their understanding of the world.

A few things are new this year. For one, the date. The Library moved the festival earlier in the summer — Aug. 12 as opposed to Labor Day weekend — based on the convention center’s availability.

Mary Louise Kelly will speak about her book “It. Goes. So. Fast.” Photo: Courtesy of NBF.

Mary Louise Kelly will speak about her book “It. Goes. So. Fast.” Photo: Courtesy of NBF.The festival also has fewer authors this year and will unfold over less square footage: six stages compared with 11 last year. The 2022 festival — the first held in person since 2019 because of the COVID-19 pandemic — attracted smaller crowds than past festivals at the convention center.

In response, Library organizers recalibrated, seeking to determine what size festival audiences are comfortable with in a post-pandemic world in which COVID-19 remains on people’s minds.

“This is an experiment this year,” said Jarrod MacNeil, director of the Signature Programs Office. “We’re seeing what it looks like to have a smaller footprint, to have fewer stages.”

Clay Smith, the festival’s literary director, sees potential benefits in bringing readers and sessions closer together.

“When you have the geography of the festival smaller, you’re having more interactions between readers. That’s very positive,” he said. “And when you are making it easier for people to get to sessions, you increase the sense of discovery.”

Each of this year’s six stages — Creativity, Inspiration, Insight, Understanding, Curiosity and Discovery — mix genres. Session titles alert festival-goers to subject matter.

Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden will officially welcome festival-goers on the Creativity stage at 9:30 a.m., followed by a session with beloved children’s author R.J. Palacio. She adapted her graphic novel “White Bird: A Wonder Story” into a prose novel with Erica S. Perl, who will appear with her. National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature Meg Medina will moderate the session.

Tahir Hamut Izgil will be speaking at this year’s festival. Photo: Courtesy of NBF.

Tahir Hamut Izgil will be speaking at this year’s festival. Photo: Courtesy of NBF.Medina and Palacio are among 12 authors of Hispanic heritage to take the stage at this year.

Although last year’s festival may have had smaller crowds, the group was the most diverse of any National Book Festival. The Library aims to build on this success, understanding that authors’ backgrounds do not necessarily correlate with those of audiences.

“We want to diversify our overall attendance at the festival,” MacNeil said. “We want to have a good representation of Americans.”

The sessions following Palacio on the Creativity stage — which, like the Inspiration stage, will be livestreamed — reflect the variety of genres festival-goers can expect on stages this year.

David Grann will discuss his new release, “Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder,” with National Book Festival Co-Chair David M. Rubenstein. TJ Klune will present “In the Lives of Puppets” about artificial intelligence robots and their human son. And Beverly Gage will discuss her Pulitzer Prize-winning book about J. Edgar Hoover, “G-Man,” with author James Kirchick.

Then, Oscar-nominated actor and trans activist Elliot Page will discuss his memoir, “Pageboy,” and NPR journalist Mary Louise Kelly will speak about hers, “It. Goes. So. Fast.”

Their memoirs are among 10 the festival will showcase, including Uyghur poet Tahir Hamut Izgil’s “Waiting to Be Arrested at Night”; teacher Chasten Buttigieg’s “I Have Something to Tell You”; football player R.K. Russell’s “The Yards Between Us”; and Atlantic writer John Hendrickson’s “Life on Delay: Making Peace with a Stutter.”

In other highlights, author Amor Towles will discuss his latest bestseller, “The Lincoln Highway.” Tananarive Due and Grady Hendrix will talk horror fiction in a session titled “Hauntings Aren’t Just for Houses.” Pulitzer Prize-winning sociologist Matthew Desmond will discuss his latest book, “Poverty, by America.” And festival stalwart Douglas Brinkley will pair up with David Lipsky in the session “History Is Heating Up,” about climate change. Food as a key to people’s hearts takes center stage in “Dig In” with authors Cheuk Kwan and Anya von Bremzen.

At 5:15 p.m. on the Inspiration stage, Hayden will confer the Library’s 2023 Prize for American Fiction on acclaimed author George Saunders, after which Saunders will speak.

As always, the festival will feature rich selections for children and young adults, the aforementioned titles by Palacio, Medina, Buttigieg, Due and Hendrix being only a small sample.

Children can also enjoy a new offering on the expo floor, Story District, where festival authors will read to families. At Roadmap to Reading, kids can visit Center for the Book affiliates to learn about authors from different states and win prizes.

Cheuk Kwan, author of “Have You Eaten Yet?’ Photo: Courtesy of NBF.

Cheuk Kwan, author of “Have You Eaten Yet?’ Photo: Courtesy of NBF.Book sales and signings and Library merchandise will also be on offer on the expo floor (located where the Main Stage was last year), as will a Library of Congress area where staff members will present Library-based content and activities.

Those who visit will get to try their hands at transcribing historical documents; learn how to research LGBTQ+ history in Chronicling America; find out about culinary treasures and comics in the collections; and discover the Library generally, including through a Spanish-language overview.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 7, 2023

Q & A: Hannah Whitaker, Preserving Live Music from Long Ago

Hannah Whitaker is pursuing a master’s degree in library and information science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She is interning this summer as a junior fellow in the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center (NAVCC).

Tell us a little about your project.

I’m working with Erika Cooley, a junior fellow from the University of South Florida, at NAVCC in Culpeper, Virginia. We’re processing 16-inch lacquer discs from the Universal Music Group collection.

The collection contains thousands of discs that were created between the 1930s and the 1950s, primarily under the Decca label. Notable artists featured in the collection include Bing Crosby, Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday and Jimmy Dorsey, among countless others.

Lacquer discs, which are made by coating an aluminum disc with a thin layer of nitrocellulose, were used in the early 20th century to capture live recording sessions. The lacquers were then used to form metal masters and stampers, designed to mass-produce discs to be sold commercially. Our job is to inventory the original lacquers and create metadata for them so they can be cataloged.

Describe a typical day.

Each day, Erika and I input the metadata we create into an Excel spreadsheet.

First, we remove the discs from their original — and often damaged — sleeves and insert them into sturdy sleeves on which we write the disc’s identifying matrix number that was assigned at the time of recording, the artist’s name and the song title. We then assign each disc a new number — called an IDC (instantaneous disc) number — so archivists can easily identify specific materials within the vaults.

When working with discs that are nearly 80 years old, it is not uncommon to find broken or damaged discs. When we inevitably do, we inventory the discs, then place them into broken disc housing. From there, NAVCC audio engineers will digitize them before further damage can be done. Our goal is to mitigate any damage and preserve the music.

When creating metadata, Erika and I include as much information as we can glean from the contents of the disc and its accompanying sleeve, including who the artist was, the song title, how many tracks are cut into the disc and any notes that may have been written or etched directly onto the disc. Once the lacquer discs are inventoried, researchers will be able to more easily access the collection.

What have you discovered of special interest?

What I find most interesting about this project hasn’t been one specific thing, but rather the time period during which many of these lacquers were cut, including during World War II.

During the war, aluminum was rationed, forcing recording studios to adapt and use glass as the base for lacquers. Erika and I processed a glass-based lacquer from 1939. I can’t help but become emotional when I realize that during the darkest time in global history, artists continued to create, bringing light into the lives of petrified, weary individuals. Still, we danced.

Additionally, Erika and I were taught about IRENE, which stands for Image, Reconstruct, Erase, Noise, Etcetera. IRENE can play back damaged discs that cannot withstand a stylus by using a camera with microscopic capabilities to detect the edges of the grooves. It was fascinating to learn how broken discs can still be digitized with ingenious technological advances.

What attracted you to the Junior Fellows program?

As a library science master’s student, I was searching for a fellowship that would allow me to draw on my knowledge of music trivia while providing me with relevant archival experience. This junior fellowship is doing just that. I have learned so much in the few short weeks I have been here and know that I will carry these preservation and conservation skills throughout my career in libraries, wherever it may take me.

What has your experience been like so far?

Both Erika and I find working at NAVCC educational and exciting. We got to attend the 2023 Audio Engineering Society’s international conference on audio archiving, preservation and restoration, which was hosted here in Culpeper, providing us with invaluable networking opportunities.

NAVCC is staffed by such intelligent and supportive librarians, archivists, engineers and technicians who are gracious and eager to teach. This fellowship has granted us a strong foundation in audio preservation and archival practices and will only serve to benefit our future careers as librarians and archivists.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 3, 2023

Hannah Carson: “Like a Fire in All My Bones”

This is a guest post by Sara Augustin, a 2023 Junior Fellow in the Office of Communications.

Nestled in the archives of the Daniel A.P. Murray Collection is a short account of the remarkable life of Hannah Carson. It’s a small, 50-odd page book called “Glorying in Tribulation: A Brief Memoir of Hannah Carson, For Thirteen Years Deprived of the Use of All Her Limbs.” It was published by the Protestant Episcopal Book Society in Philadelphia shortly after Carson’s death in 1864.

It’s actually a short biography written by her friends rather than a memoir penned by herself, but no matter. Though almost completely disabled by severe rheumatism for the final years of her life, Carson’s Christian faith, “like a fire in all my bones,” was deeply moving to those around her. They regarded her as something near a saint.

At the ecumenical service after she died in her own bed on March 8, 1864, at the age of 55, “Her little room was crowded by her friends, both white and colored, who assembled to pay the last tribute of respect” to her, the book notes. She was buried in Lebanon Cemetery. (More on that in a minute.)

The book was not a bestseller but came to the attention of Murray, who in 1871 became only the second Black person to work at the Library of Congress. He would stay for half a century, becoming an assistant librarian and prominent in Washington society and politics.

During his tenure, he compiled a Preliminary List of Books and Pamphlets by Negro Authors, which surveyed the field up to 1900. Carson’s memoir is featured on Murray’s list, and a copy is now in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

Carson’s story was as straightforward as it was heartbreaking.

She was born Hannah Tranks in southern Pennsylvania in 1808 to free parents. She was raised in the Methodist Church. At 18, her mother died and she was left with the care of her six younger siblings, according to the book. She eventually moved to the Philadelphia area and married Robert Carson. They had three children, but only one, a son, survived infancy.

Robert Carson died in 1841, leaving her a widow and single mother at age 33. She cheerfully took to hired housework to pay the bills. After half a dozen years of this labor, she noticed a soreness one day in her right thumb that stretched up her arm and into her shoulder. She continued to work, but the pain eventually spread down her left arm and then into her legs. It was diagnosed as acute inflammatory rheumatism, an autoimmune disease.

Over four years, the disease progressed until she was completely bedridden, unable to feed herself or brush a fly from her face. She was almost completely paralyzed and would remain so for the remaining 13 years of her life.

For Carson, like other disabled Americans at the time, there was neither a federal safety net nor any other government-backed accommodation that could provide for her. As a Black woman on her own, her situation was even more difficult. She was completely dependent on the charity of family and friends. With that aid, she hired “a little girl who waited on her.” Her apartment was “scrupulously neat and clean,” but she was constantly in need of basic supplies.

If someone came to visit, it took work to get her into a sitting position: “…she would request her attendant, a little colored girl, to raise her by means of a girth fastened round her waist, and by which she was elevated to a sitting posture; her limbs were then slowly drawn around, until they reached the floor; her back was propped with pillows, and her arms stretched out, resting on her lap, the palms inwardly.”

Carson’s religious beliefs, meanwhile, gave her a new career: Evangelizing for her faith.

Long a faithful member of “the colored Bethel church in Sixth Street, below Pine,” she was well known to the Christian community. At her home, Carson emulated the environment of the Negro church and benefited from creating her own sanctuary: “always welcomed, who beheld, with astonishment, an unlearned mulatto woman discoursing on Divine things with a spirituality and unction that the pulpit well might emulate.”

In the still of the nights, she prayed until she could see visions of heaven. During the days, she often read a Bible placed in her lap, a helper turning the pages. Once she proclaimed that she had seen a vision of Christ himself. She prayed constantly for her “absent, wandering son,” who seldom visited.

And yet her faith was a beacon. As she told one group of friends who visited: “While you have been with me, the love of Christ has kindled like a fire in all my bones, and has driven out the pain and anguish, till I am full of joy.”

The disease finally took its final toll: “she passed away without a struggle, quietly as a child falling asleep on its mother’s bosom.”

The book’s reverence for Carson’s life is touchingly sincere — her many admirers were both white and black, her funeral ceremony included speakers from several Christian denominations who attested to the testimony her life had been — but respect and admiration could only go so far in 19th-century Philadelphia.

After the ceremony, Hannah Carson was buried in a segregated cemetery, as whites did not allow the Black dead in their own burial grounds.

Carson’s life not only proved to be a deep testament to her Christian faith but also offers a unique window into the life of Black disability in the late 19th century.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 2, 2023

Let’s Dance!

This article also appears in the July-August issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Garth Fagan is known around the world for bringing Simba, Mufasa and Scar to life as choreographer for Broadway’s “The Lion King.” More than 100 million people have seen the beloved musical since its debut a quarter century ago, either on Broadway itself or in one of 25 global productions.

But Fagan’s renown extends well beyond “The Lion King.” Over the decades, he has developed a unique form of American dance combining the strength training and precision of ballet with the Afro Caribbean rhythms and movements of his native Jamaica.

When the Library acquired Fagan’s papers earlier this year, they joined, and built on, Music Division collections of an array of dance luminaries: Martha Graham, Alvin Ailey, Bronislava Nijinska, Katherine Dunham and the American Ballet Theatre to name a few.

The Library’s dance-related materials cover the American art form from Colonial times to the present. Early on, materials came into the collections mostly by virtue of their connection to other subjects — dances depicted on sheet music covers, for example, or instructions and commentary in books.

But dancing can be hard to document, dance curator Libby Smigel said: “Transmission is often through person-to-person teaching and coaching.”

Most choreographers and dancers did not maintain personal collections until the mid-20th century, a fact the Library’s holdings reflect.

Programs, photos and recordings form the core of most dance personal collections, along with scrapbooks assembled by a loving relative or fan, Smigel said. “I’m excited when we get a special prop.”

Two of her favorites: the umbrella Judith Jamison danced with in Ailey’s “Revelations” and fans and masks from Java that dancers from the Denishawn Company used in South Asia.

Some of the Denishawn Company masks. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Some of the Denishawn Company masks. Photo: Shawn Miller.A concerted effort to acquire dance at the Library grew out of a pilot program in the 1980s with the nearby John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. The pilot aimed to advance knowledge about dance and inspired the Library’s purchase of multiple collections.

Early acquisitions document pioneers such as Russian-born ballet choreographer Nijinska and modern dancer Ruth St. Denis, co-founder of the Denishawn Company.

In 1998, the Library purchased the eagerly sought-after archives of Graham, followed by acquisitions of complementary collections — some 20 of them, including those of dancers from her company.

“The Library is a cornerstone for serious research on Graham now. You can’t really do without it,” Smigel said.

Even before acquiring her archive, the Library had a special relationship with Graham.

In 1942, Library benefactor Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge commissioned a collaboration between Graham and composer Aaron Copland to produce a ballet. “Appalachian Spring” premiered in the Library’s Coolidge Auditorium on Oct. 30, 1944.

Graham danced the role of the bride in the tale of 19th-century rural Pennsylvania newlyweds. Erick Hawkins, a dancer from her company (whose papers the Library also has), played her husband — a role he later assumed in real life.

Martha Graham in 1959. Photo: Unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.

Martha Graham in 1959. Photo: Unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.

The ballet earned Copland a Pulitzer Prize for Music and has continued to resonate with audiences ever since.

To celebrate the acquisition of Graham’s archive, the Library presented a 54th-anniversary performance of “Appalachian Spring” in the Coolidge Auditorium by the Martha Graham Dance Company.

“It was a really moving way to honor Graham’s relationship with the Library,” Smigel said.

Graham’s collection includes some 100,000 items in more than 400 boxes: photographs, recordings of rehearsals and performances, music, posters, Graham’s choreographic notes and her correspondence with major 20th-century figures, as well as her personal papers. Researchers can access these collection items at the Library along with magazines, books and films that shed light on Graham’s legacy.

A particular strength of the Library’s dance holdings, Smigel said, is the rich context in which they exist: alongside other collections that deepen understanding of productions.

The American Ballet Theatre’s production of “Fall River Legend” is Smigel’s go-to example.

Agnes de Mille choreographed the ballet, which premiered in New York City in 1948. It interprets the story of Lizzie Borden, famously acquitted of hatchet-murdering family members in Fall River, Massachusetts, in 1892.

The Library also has costume designs by Miles White and the papers of set designer Oliver Smith, breakthrough lighting designer Peggy Clark and composer Morton Gould. (His scrapbooks contain a Life magazine story that reprints photos from the original crime scene.)

But the Library also has publicity photos of the original cast by Louis Melancon, news stories from across the country about the Borden murders, a book de Mille wrote about her research to create “Fall River Legend” and another book from 1893 by journalist Edwin H. Porter, who made a case for Borden’s guilt.

De Mille relied heavily on Porter’s book to research the Borden story, Smigel said. And contrary to the jury’s conclusion, de Mille ends “Fall River Legend” with Borden’s hanging.

“Each of these pieces comes from a different collection,” Smigel said. “You can’t tell any story with just one piece of information or one person’s papers or special collection.”

Now, Smigel is looking forward to the stories that will be told from Fagan’s materials. “How did he transform his start-up company in Rochester, New York, into the company that did ‘Lion King?’ ”

“At long last,” Smigel said, “we’ll have the material to celebrate his achievement.”

July 27, 2023

Free to Use and Reuse — Gardens

It’s been a while since we’ve checked in on our Free to Use and Reuse sets of photographs, those delightful copyright-free images that you can use any way you like for anything you like. We’ve featured dozens of these on the blog, including those covering autumn and Halloween, wedding pictures and everybody’s favorite, travel posters.

Since we’re in the middle of summer, let’s take a look at gardens.

There are various ways to define the word, but what better way to kick things off than with a hand-colored lantern slide by the most wonderful Frances Benjamin Johnston? She was a pioneer of portrait photography, architectural photography and women’s rights. Born into an educated family, she was a striver who worked to be well-connected in the upper realms of society. She photographed presidents (she took the last photograph of President William McKinley before he was assassinated), socialites, industrialists and artists. Her landscape photography is famous today, but she didn’t start until she was 50.

“Blue Garden,” part of her “Beacon Hill House” series, takes us back to the summer of 1914 and the mansion of Arthur Curtiss James, whose 33-acre estate on Beacon Hill Road in Newport, Rhode Island, was quite the spread. James, largely forgotten today, was a railroad baron with an enormous fortune.

His garden was all about Gilded Age wealth and prosperity, about making America beautiful. “Garden” here is about landscaping in the highest sense of the art form, a cultivated landscape for a particular effect. It was part of a movement to beautify the nation, to turn the riches of the industrial age into refined, classic beauty. Johnston’s composition of the manicured landscape — the tranquil pool, the delicate purple of the flowers, the urns, statuary and columns — matches its expensive elegance.

This photo is something of a Library darling, as it was the focus of the “Every Photo is a Story” video series about how to read, or interpret, photographs. The image was also an important find by Sam Watters, an architecture and landscape historian, in his work into Johnston’s career, as more than 1,100 of her images at the Library were uncatalogued for decades. Most had little or no identification. Watters selected 250 for his book, “Gardens for a Beautiful America, 1895-1935: Photos by Frances Benjamin Johnston.” was co-published with the Library in 2012. The pictures had not been seen publicly since the 1940s.

As Watters noted in a 2013 lecture, Johnston never quite made it into those upper social realms of the people whose lives, houses and gardens she photographed so beautifully.

“She never gets to be a member of a garden club; she is the hired help,” he said. “Photographers like Johnston were down below artists, and so were landscape architects.”

Today, her work outlives many of the names and reputations of those she photographed.

Bob Jarrell working in his West Virginia vegetable garden. 1996. Photo: Mary Hufford. American Folklife Center.

Bob Jarrell working in his West Virginia vegetable garden. 1996. Photo: Mary Hufford. American Folklife Center.This right here is Bob Jarrell’s vegetable garden in West Virginia. The year is 1996 and that is Jarell in the foreground. It’s one of about 1,250 photos in the Coal River Folklife Collection in the American Folklife Center.

This photograph is pretty much the opposite of “Blue Garden” — not pretentious in manner, composition or subject matter. The beauty is not in its grandeur but in its working-class simplicity. The sagging sunflowers. The soft sunlight of late summer.

It’s also a more recent window into our past. If you grew up in rural America in the second half of the 20th century, then “garden” almost certainly meant “vegetable garden,” a place your parents made you go almost every day in summer, picking things you didn’t want to eat at a time you didn’t want to do it. Also, there were bugs. These gardens were family affairs, for canning and preserving for the winter ahead.

“Garden” in this sense carried an implication of self-reliance, of independence, of a work ethic that involved sweat and dirt. There were no trendy raised and boxed beds for planting, no irrigation systems and nobody used the word “artisanal” when they put the butterbeans on the table. The pressure cooker or canner was probably the one that your grandma used; it weighed a ton didn’t look like it came out of a Williams-Sonoma catalog.

That’s an American garden, too.

The Medici Fountain in Luxembourg Gardens, as it appeared in the 1890s. Photochrom print: Detroit Publishing Company. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Medici Fountain in Luxembourg Gardens, as it appeared in the 1890s. Photochrom print: Detroit Publishing Company. Prints and Photographs Division.Let’s do something completely different for our third example — Luxembourg Gardens, the delight of Paris and one of the world’s great promenades. It was built by Marie de Medici, the widow of Henry IV and regent on behalf of her son. She started in 1612, inspired by the Boboli Gardens of Florence, Italy, where she grew up.

The Medicis knew how to make a grand garden, a regal blend of open space, trees, flowers, walkways, grottoes, statues, art and architecture. The Boboli would become the model for royalty across the continent and Marie had a stunning example built in Paris. She started with 2,000 elm trees. Eventually, it would expand from its original 15 acres to nearly 60 acres of landscaped loveliness around the equally stunning palace that is today home to the French Senate.

One of the highlights of the garden always has been the Medici Fountain. It was originally constructed as a grotto, or artificial cave, also like ones she remembered from the Boboli. But centuries passed and the fountain fell into disrepair. A major revision in the 1860s moved the fountain about 30 yards, added the urn-lined basin in front and replaced the statuary.

Our photo from the 1890s is a photochrom by the Detroit Publishing Company, which was famous for making these sorts of early color images for postcards. You can almost feel the peace of the Parisian sunlight on this afternoon when the photographer trundled his equipment through the park to the fountain and set to work. The afternoon passed. The light glinted. Perhaps a breeze. It was a job, sure, but it’s not hard to imagine that the photographer, like visitors before and since, wanted to linger. Rarely do we find places so beautiful.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers