Library of Congress's Blog, page 25

March 17, 2023

Joni Mitchell’s Conversation in the Library

The Library wrapped up its tribute to Joni Mitchell on a high note last week with a conversation between the 2023 Gershwin Prize winner and Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden. In an exchange punctuated by laughter and ending in song, Mitchell detailed her unexpected evolution as a musical pathbreaker.

The March 2 event followed a joyous all-star concert in Constitution Hall the previous evening, which Mitchell likened to one of her “Joni Jams,” gatherings she hosts bringing together musicians across generations.

“The musical excitement of last night was very intense,” Mitchell said. “You have my beautiful band, which is my generation, and then all these young’uns, too. They’re playing with musicians that were their heroes. … It was beautiful.”

Now considered one of the most influential songwriters of our time, Mitchell didn’t dream of becoming a musician growing up. “I always wanted to be a painter,” she said. “I didn’t do air guitar in front of the mirror or any of that.”

When she was in sixth grade, a teacher noticed she liked painting. She remembered him telling her, “Well, if you can paint with a brush, you can paint with words.” In that act, she said, “he gave me permission to do both.”

Georgia O’Keeffe at one point tried to persuade her otherwise — Mitchell stayed with the famous modernist “for a while” — telling Mitchell that you can’t, in fact, do both.

Not true, Mitchell quipped, “You just have to give up TV.”

Joni Mitchell sits at George Gershwin’s piano at the Library. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Joni Mitchell sits at George Gershwin’s piano at the Library. Photo: Shawn Miller.Trained as a commercial artist, Mitchell designed her own album covers, many featuring her own paintings, mostly self-portraits. She carried disposable cameras with her (after expensive models were stolen) and painted based on the photos. Her catalog now extends back decades.

When she started as a musician, she sang folk songs, “because they were easy. They didn’t take a lot of skill,” she said.

She was already a Miles Davis fan, however, and she became known for crossing and combining genres, drawing on jazz, classical and rock.

“My songs … they’re not folk music, they’re not jazz, they’re art songs. They embody classical things and jazzy things and folky things, long line poetry,” Mitchell said.

Despite receiving many, many accolades over her career, early on, she “got nothing but bad reviews.”

“It didn’t discourage you … all those reviews?” Hayden asked.

“[I’m] hard to discourage and hard to kill,” Mitchell responded to applause. In 2015, she suffered a devastating brain aneurysm and has since regained her voice.

As a special gift from the Library, Susan Vita, the Music Division’s chief, presented Mitchell with a facsimile of the original title page to George Gershwin’s “Porgy and Bess” and the score to the start of its iconic “Summertime” — the night before, Mitchell brought the audience to its feet with her rendition of the song, her favorite Gershwin composition.

“I love the melody of it. I like the simplicity of it,” Mitchell said. “I really get a kick out of singing it.”

Vita also presented Mitchell with a gold lapel pin modeled on the Gershwin Prize medal, which she attached to Mitchell’s signature beret — a beautiful deep purple on March 2.

Earlier in the day, Mitchell viewed treasures from the Library — folklife interviews and maps from Saskatchewan, Canada (Mitchell grew up in the province); a film clip of Ray Charles performing at the Montreux Jazz Festival (Mitchell attended her first concert when Charles played her hometown); an artist’s book inspired by the Charles Mingus’ composition “Pithecanthropus erectus” (Mitchell collaborated with the great jazz bassist); and original copyright applications for Mitchell’s works (she was presented with an official certified copy for “Big Yellow Tax.”)

Mitchell also viewed the first edition of the “Star-Spangled Banner”; the manuscript of Mozart’s violin sonata, K. 379; and Gershwin’s autograph manuscript sketchbook, 1937, open to the page with his original sketch for “Love Is Here to Stay,” from which Mitchell sang a verse with music specialist Ray White.

In the Jefferson Building’s Gershwin gallery, Mitchell played on Gershwin’s piano and viewed self-portraits by George and Ira Gershwin — self-portraiture is another art Mitchell has in common with the brothers, Vita said.

One item presented to Mitchell on March 2 had special meaning: the unpublished manuscript copyright deposit for “Hammer Head” by Wayne Shorter. A dear friend and collaborator of Mitchell’s, he died earlier in the day.

“Wayne Shorter to me was the best saxophonist ever,” Mitchell said.

She has ideas for new songs, she said, but is kind of “stumped” on how to move forward.

“The world seems to have lost its way,” Mitchell said. “So, to write songs along those lines is a big responsibility.”

She a lot of ideas, however, about what to paint, first and foremost her new cat — she has painted all of her cats.

“My house is full of memories as I go around,” Mitchell said.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

March 15, 2023

Crime Classics: “A Gentle Murderer” Joins the List!

This is a guest post by Zach Klitzman, editorial assistant in the Library’s Publishing Office .

A priest, a detective and an impoverished poet might sound like the setup to a joke—but Father Duffy, Sergeant Ben Goldsmith and Tim Brandon are no laughing matter in the gripping new addition to the Library of Congress Crime Classics series, “A Gentle Murderer.”

Dorothy Salisbury Davis’ landmark novel, first published in 1951, combines suspense and innovative psychological insight as Duffy, a Catholic priest, and Goldsmith, an NYPD detective, attempt to track down Brandon, who had confessed — anonymously — to murdering a call girl.

Critic Anthony Boucher described the novel as “one of the greatest detective stories of modern times” and in the introduction to the Library’s edition, Crime Classics series editor Leslie S. Klinger describes it as “a masterpiece” for blending two subgenres of crime fiction: clerical detectives and criminal profiling.

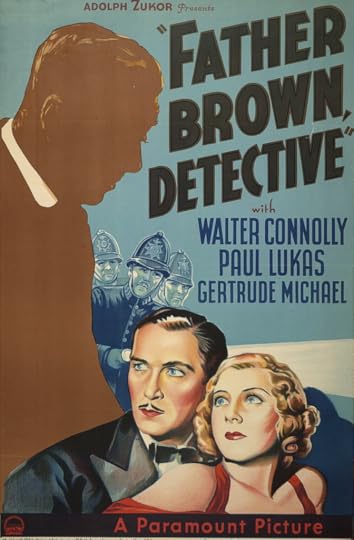

Although there are some biblical antecedents, clergy investigating crimes in detective fiction dates to the early 20th century. G. K. Chesterton’s Father Brown appeared in more than 50 stories, starting with 1911’s “The Innocence of Father Brown.” Several radio, television and film adaptations followed, including a 1934 film starring Walter Connolly as the Catholic priest.

“Father Brown, Detective,” a 1934 Paramount film. Prints and Photographs Division.

“Father Brown, Detective,” a 1934 Paramount film. Prints and Photographs Division.Other famous clerical detectives post-date Davis’ protagonist and include Rabbi David Small, who first appeared in Harry Kemelman’s “Friday the Rabbi Slept Late” in 1964. There’s also Cadfael, the 12-century Benedictine monk who appeared in 21 novels written by Ellis Peters (a pseudonym for Edith Pargeter), starting in the late 1970s; and, of course, William of Baskerville, the Franciscan friar of Umberto Eco’s 1980 seminal work, “The Name of the Rose.”

In “A Gentle Murderer,” Father Duffy investigates Brandon’s past and present, through the tenements of New York City to rural Pennsylvania and to Cleveland. Goldsmith, meanwhile, utilizes traditional police methods including interviewing witnesses, canvassing the neighborhood where the crime was committed, and using what we would call criminal profiling to try to understand what kind of person would commit the murder.

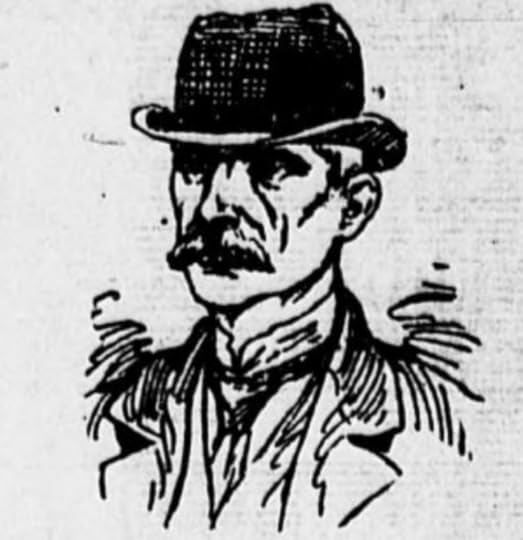

Criminal profiling first came into vogue in the late 19th century with the Jack the Ripper killings in London, which transfixed the public on both sides of the Atlantic. Several theories emerged about the identity of the killer of at least five women. Surgeon Thomas Bond created an 11-point profile of the killer for the Metropolitan Police, concluding that the killer was likely “a man subject to periodical attacks of Homicidal and erotic mania” who also “would probably be solitary and eccentric in his habits.” Although the offender was never caught, Bond’s theories ushered in a new era of crime detection.

“Jack the Ripper’s Mark,” April 25, 1891. “The Sun” (New York, NY). Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

“Jack the Ripper’s Mark,” April 25, 1891. “The Sun” (New York, NY). Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.One of the next big cases of criminal profiling occurred in the 1950s with the Mad Bomber of New York City. From 1940 to 1956, the perpetrator planted 32 bombs, 22 of which exploded, injuring 15 people. The police were stymied until psychiatrist James A. Brussel created a profile of a man who was roughly 40 to 50 years old; likely lived alone, possibly in Connecticut; was a disgruntled former Con Edison employee (the first bomb had been sent to that power company); and likely would wear a double-breasted suit when he was arrested.

The profile was publicly released in newspapers December 25, 1956, and it led to hundreds of false leads, bomb threats and confessions. But within a month George Metesky — a 53-year-old Waterbury, Connecticut, resident who had been injured while working for Con Edison in 1931 — was arrested. He wore a double-breasted suit when the police removed him from his house.

George Metesky, known as the Mad Bomber, under arrest. Photo: Ed Ford, 1957. Prints and Photographs Division.

George Metesky, known as the Mad Bomber, under arrest. Photo: Ed Ford, 1957. Prints and Photographs Division.The FBI established a Behavior Science Unit in 1972. The trope of using psychology to figure out criminal identities in popular entertainment became commonplace, as seen in films such as “Silence of the Lambs,” television shows such as “Criminal Minds” and nonfiction books with titles like “Manhunters: Criminal Profilers & Their Search For The World’s Most Wanted Serial Killers.”

Dorothy Salisbury Davis’ use of criminal profiling made her a trendsetter, a distinction that holds true for much of her 20 novels and many short stories. Before her crime fiction took off, she worked as a magician’s assistant, a technical writer for a meatpacking company and a research librarian and editor at a magazine.

She received several Edgar Award nominations and was named a Grand Master by the Mystery Writers of American in 1985. Though women mystery writers such as Anna Katharine Green and Agatha Christie had achieved success, Davis was part of the first generation of women to write domestic suspense novels. She was a founding member of Sisters in Crime, an organization of women mystery writers. Davis died at the age of 98 in 2014.

Library of Congress Crime Classics are published by Poisoned Pen Press, an imprint of Sourcebooks, in association with the Library of Congress. Each volume includes the original text, an introduction, author biography, notes, recommendations for further reading and suggested discussion questions from mystery expert Leslie S. Klinger. “A Gentle Murderer,” published on March 7, is available in softcover ($14.99) from booksellers worldwide, including the Library of Congress shop.

March 8, 2023

My Job: Jan Grenci

Jan Grenci helps bring poster collections to light. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Jan Grenci helps bring poster collections to light. Photo: Shawn Miller.Describe your work at the Library.

As the reference specialist for posters in the Prints and Photographs Division, my workdays are full of varied tasks. I spend part of most days working on our reference desk, helping patrons with their research on a wide range of topics — every specialist also should be a generalist. We can and do answer questions about all parts of the visual material collections for any topic a researcher may be interested in.

I also am the go-to person for every reference question related to posters. In addition to in-person service, I answer hundreds of questions a year through our Ask a Librarian online reference service.

When not helping our nation’s readers, I get to spend time working on poster-related projects — for example, surveying the contents of our large collections of posters, preparing the circus poster collection for its recent digitization and working with a volunteer who is translating and cataloging 20th-century Japanese posters in our collection.

I also give tours to groups, especially those with interest in graphic design and posters, as well as preparing displays for visitors to the Library. When not doing all of the above, I also write for the Picture This blog and create thematic albums for the Library’s Flickr photostream.

How did you prepare for your position?

Though I didn’t know it at the time, my educational background prepared me well for my work here. I have an undergraduate degree in history and a master’s in art history. Posters reflect the times and art styles of when and where they were made.

When I started working in Prints and Photographs as a reference technician, I asked as many questions as I could and paid attention to my colleagues with years of experience. I was very fortunate to work closely with Elena Millie, then the curator of posters, who taught me all about the collection. Hands-on work with our one-of-a-kind poster collection has been the best preparation for my job.

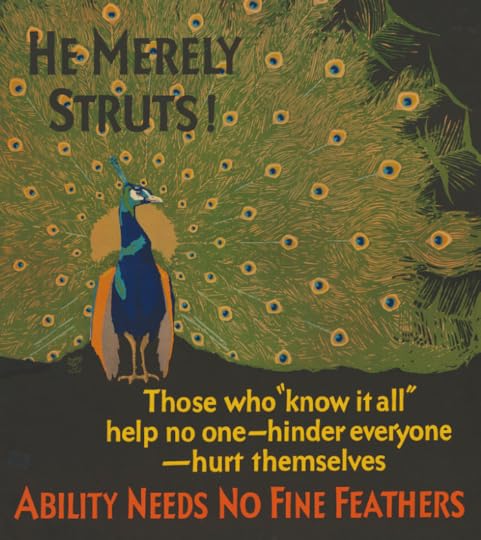

“He Merely Struts!” a 1929 poster by Willard Frederic Elmes. Prints and Photographs Division.

“He Merely Struts!” a 1929 poster by Willard Frederic Elmes. Prints and Photographs Division.What are your favorite collection items?

Picking a favorite collection item is like asking a mother to pick her favorite child. I have many favorite posters. One is a 1929 work-incentive poster by Willard Elmes titled “He Merely Struts!” The poster features a beautifully rendered peacock, with a message that always has rung true to me: “Ability Needs No Fine Feathers.” To me, this means that doing your work well is more important than tooting your own horn.

What have been your most memorable experiences at the Library?

Discussing Josef Albers’ color theory with a group of weavers. Because of a very excited audience and an overly enthusiastic presenter, some say this was the loudest tour ever given in Prints and Photographs.

I often take on searches for patrons for pictures of their family members in our collections, most notably in the LOOK Magazine Photo Collection, the Farm Security Administration Collection and, recently, in the Milton Rogovin Collection. It’s extremely satisfying to connect people to a part of their past that they had only imagined, and those moments have been some of my most memorable.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

March 2, 2023

Joni Mitchell’s Gershwin Prize Concert Showcases Her Music and Influence

“You don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone,” Joni Mitchell famously once wrote. On Wednesday night at Constitution Hall, Mitchell showed that she’s definitely still got it.

The 79-year-old Mitchell, who has performed sparingly since suffering a brain aneurysm in 2015, closed a concert staged in her honor in dramatic fashion, leaning against the piano and flawlessly delivering a slow and sultry rendition of the Gershwin standard “Summertime” — the highlight of an evening filled with them.

The Library of Congress on Wednesday bestowed its Gershwin Prize for Popular Song on Mitchell, the singer-songwriter best known for such 1970s classics as “Both Sides Now,” “Big Yellow Taxi” and “Help Me.” Her lyrics were deeply personal, her music was technically accomplished and her sound incorporated elements of folk, pop, rock and jazz.

“Oh, my God, it’s overwhelming. It’s just a beautiful event,” Mitchell said, noting that the evening brought together artists from the entire range of her career. “New friends, old friends — it’s thrilling.”

The cast of admiring musicians on hand to celebrate the Mitchell legacy indeed spanned generations and genres.

An all-star ensemble cast performs at Joni Mitchell’s Gershwin Prize concert. The artworks are enlargements of Mitchell’s paintings. Photo: Shawn Miller.

An all-star ensemble cast performs at Joni Mitchell’s Gershwin Prize concert. The artworks are enlargements of Mitchell’s paintings. Photo: Shawn Miller.There were contemporaries like classic soft rockers Graham Nash and James Taylor. There was Herbie Hancock, one of the great pianists in jazz history and an inspiration for Mitchell’s own forays into the genre. And there were performers who followed in Mitchell’s footsteps, drawing inspiration from her work: ’80s pop divas Cyndi Lauper and Annie Lennox, acclaimed jazz pianist and singer Diana Krall, world music star Angélique Kidjo, R&B singer Ledisi, indie pop band Lucius and modern folkies Brandi Carlile and Marcus Mumford.

Mumford kicked things off, walking onto a stage framed by massive reproductions of Mitchell’s paintings — she also is an accomplished visual artist — to perform “Carey.” That song, written by Mitchell while she was living among a cave-dwelling hippie community on the Greek island of Crete, was one of five drawn on Wednesday from her 1971 album “Blue,” regarded by critics as one of the rock era’s great records.

Mitchell broke with Gershwin Prize tradition, eschewing a box seat for a spot in front of the stage — a move that paved the way for performers to get up close and personal with their audience.

Carlile, Kidjo, Ledisi, Lennox, Lauper and Lucius combined their talents on “Big Yellow Taxi,” starting the song on center stage, then dancing their way down the steps and through the crowd, finally singing directly to the woman of the hour sitting in the first row. Kidjo, supported by Lucius, did likewise on her performance of Mitchell’s biggest hit, “Help Me.”

Carlile, a nine-time Grammy winner and ardent Mitchell fan, did a solo turn on “Shine” and brought down the house. Hancock and Ledisi delivered a cool, jazzy version of “River.” Lennox, half of the Grammy-winning 1980s pop duo Eurythmics, delivered a dramatic version of “Both Sides Now,” Mitchell’s best-known song.

Angélique Kidjo came onto the concert floor to sing directly to Mitchell, delighting the audience. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Angélique Kidjo came onto the concert floor to sing directly to Mitchell, delighting the audience. Photo: Shawn Miller.Some performances carried a special resonance.

Nash and Mitchell were romantically involved in the late 1960s, and one of his best-known songs, “Our House,” was inspired by the domestic bliss of the home they shared in Laurel Canyon: “I’ll light the fire. You place the flowers in the vase that you bought today.” (Nash said in an interview earlier in the day those lines were a diary-like entry of exactly what the couple had done the day he wrote the song. He composed it in about ninety minutes, he said, while Mitchell was in their garden picking flowers for the new vase.)

More than a half century later, Nash took to the stage to perform “A Case of You” — a song Mitchell wrote after their romantic relationship ended.

“Love is touching souls, surely you touched mine,” Nash sang, a portrait she’d painted of him spotlighted on the stage backdrop. “Cause part of you pours out of me in these lines from time to time.”

Lauper recalled the impact of Mitchell’s artistry on her own life and a lesson she learned from it: If Joni can do it, I can too.

“When I was growing up, the landscape of music was mostly men,” Lauper said. “There were a few women — far and few, for me. Joni Mitchell was the first artist who really spoke about what it was like to be a woman navigating in a male world. You taught me so much, Joni.”

Toward the end of the program, Mitchell and Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden took the stage, along with members of Congress and Madison Council Chairman David M. Rubenstein.

“Joni Mitchell’s music hits you straight to your heart, down to your soul,” Hayden said in awarding the Gershwin Prize. “Millions grew up listening to Joni’s music — a distinct musical language — and it has touched and moved them uniquely at different periods of all of our lives. You could say she truly helped all of us look at both sides now.”

With the award came a request from Hayden: Would you honor us with a song?

Mitchell would — in fact, she’d make it a double: “Summertime” and a show-closing singalong of “The Circle Game” by the whole cast.

Joni Mitchell performs at the Gershwin Concert. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Joni Mitchell performs at the Gershwin Concert. Photo: Shawn Miller.Mitchell chose “Summertime,” she said, as a tribute to the great songwriting team that gave its name to the prize she’d just received. She and Hancock had recorded the song, written by the Gershwin brothers and DuBose Heyward, some 25 years ago for his Grammy-winning album “Gershwin’s World.”

Against a bluesy musical backdrop, her voice husky and the tempo slow, she sang: “One of these mornings, you’re gonna rise up singing. You’ll spread your pretty wings, and you’ll take to the sky.”

“Joni Mitchell: The Library of Congress Gershwin Prize for Popular Song” will be broadcast on PBS stations at 9 p.m. EST on March 31.

Purim Holiday: The Library’s Esther Scrolls

The handwritten Esther scroll, inked onto parchment and protected by a cylindrical case of silver filigree, is a delicate work of beauty and religious faith, more than a century old. It tells the biblical story of Queen Esther of Persia and how she helped save the nation’s Jews from annihilation by a wicked ruler.

The story of Esther, thought to have originated about 2,450 years ago, explains the foundation of Purim, the annual Jewish holiday being celebrated next week March 6-7. The scroll and its case, crafted in Jerusalem at the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts (today the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design) in the early 20th century, is one of the centerpieces of the Library’s collection of 30 Esther scrolls, and an important moment in Jewish culture.

The scroll “simply breathes ‘Bezalel’ with all its milestones for modern Jewish culture, and all the aspirations and dreams it implies,” wrote Ann Brener, the Library’s former Hebraic specialist, who led the acquisition of the piece in 2021.

The Library’s Esther scroll, made at the Bezalel Academy of Art in Jerusalem in the early 20th century. Photo: Shawn Miller.

The Library’s Esther scroll, made at the Bezalel Academy of Art in Jerusalem in the early 20th century. Photo: Shawn Miller.The Scroll, or Megillah, of Esther is one of five sacred books read from scrolls in synagogues on Jewish holidays. Such scrolls, whether plain or ornate, have been an important part of worship over the centuries, though only Esther scrolls are illustrated. The earliest known examples date to Renaissance Italy.

The Library’s collection of Esther scrolls spans seven centuries. The oldest entry, from Germany in the 14th century, is also the largest, at 32 inches tall, with writing in beautiful calligraphy. The most recent is from the late 20th century.

The Bezalel scroll is itself plain – black ink on faded parchment – but the silver filigree case is strikingly ornate. It is illustrated with characters from the story of Esther, lettering in Hebrew and exquisite floral work.

Equally important is who made it: master silversmiths at the Bezalel workshop, the ambitious academy founded by Boris Schatz, himself the former court sculptor to Prince Ferdinand of Bulgaria.

Schatz, as Brener noted in a 2021 post, wanted to create a new kind of Jewish art, blending the western influences of art nouveau with ancient motifs from the Near East. To this end, he founded the Bezalel school in 1906, envisioning it as a kind of artistic society set within the Jewish homeland. The school initially focused on painting, sculpture, carpet making and metal working.

The school started with two silversmiths, but the department soon grew to 80, mostly Jewish immigrants from Yemen, as their work was extremely popular. It’s not known who created the Library’s Esther scroll, or the year it was made, but it remains as a beautiful example of the form.

Every part of the scroll, including the handle, shows off its delicate silver filigree. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Every part of the scroll, including the handle, shows off its delicate silver filigree. Photo: Shawn Miller.The school closed in 1929 due to financial difficulty. Schatz died in 1932. The school was reopened in 1935 and, after the state of Israel was founded in 1948, the school flourished. It gained status as an academic institution in 1975. Today, with more than 2,300 students, it describes itself as “the essence of Israeli art and design.”

The scroll from its early days, depicting the foundation of one of the faith’s major holidays, is now preserved at the Library for future generations.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!February 23, 2023

“Just Jazz,” The Trailblazing Radio Show, Now at the Library

In the years before Donald Fagen co-founded the rock band Steely Dan, he rushed home to catch Ed Beach’s “fabulously erudite” jazz show on WRVR-FM. The New York Times described it as “the best of jazz interestingly presented. In fact, there’s nothing else quite like it on the air.”

From 1961 to 1976, Beach hosted “Just Jazz” on WRVR-FM in New York City. For two hours every weekday and four hours on Saturday nights, Beach played jazz — soloists, bands, traditional, modern — offering commentary in his distinctive deep voice. His playlist ranged from the early 1920s to the 1970s. He featured artists who achieved great fame — Charles Mingus, Duke Ellington, Max Roach, Gerry Mulligan, Lester Young — along with musicians new to his audience, often airing first releases of recordings or first-generation reissues.

His show is a standout slice of the new releases that the American Archive of Public Broadcasting (AAPB) unveiled on its website last year. The AAPB, a joint project of the Library and the Boston public broadcaster GBH, digitally preserves public radio and television programs and shares online content. The Council on Library and Information Resources awarded $330,816 to New York’s renowned Riverside Church and the AAPB in 2018 to digitize, preserve and make public previously unavailable WRVR archival recordings. Beach’s programs were separate — the Library acquired his collection in the 1990s — but they were digitized as part of the project. Beforehand, only a few were available on-site at the Library on request.

“Ed’s collection had incredible range,” said Rob Bamberger, the longtime host of “Hot Jazz Saturday Night” on WAMU 88.5, the National Public Radio station in Washington, D.C. “One of the things that I actually find so sweet about listening to Ed is that his presentation is stripped of the decades of analysis on jazz that we have now. Ed was working from a frame of personal reference, because he was so much closer to the original ground.”

“Just Jazz” is part of a larger new exhibit on the AAPB website devoted to WRVR-FM, a pioneering noncommercial broadcaster that influenced public radio’s early years. Operated by the Riverside Church — its dramatic limestone structure sits atop one of New York City’s highest points — the station presented a rich diversity of religious programming along with public affairs and current events.

WRVR’s civil rights reporting helped win the station a Peabody Award in 1964, and Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous antiwar speech, “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence,” into a WRVR microphone in 1967. Countless others were also heard over its signal: Nelson Mandela, the Dalai Lama, presidents and Supreme Court justices, novelists and playwrights.

But WRVR devoted most of its broadcast hours to music, especially in its early years, and “Just Jazz” was the station’s flagship jazz program. When Beach did his show, only the most celebrated early jazz recordings were publicly available, and jazz writing likewise focused on a small circle of performers. Beach’s show was far more wide-ranging.

Alan Gevinson, who directs the Library’s side of the AAPB project, invited Bamberger to help select which Beach programs to make available on the AAPB website. (Researchers can now access all 1,000-plus programs on-site at the Library or through GBH.)

Bamberger is a familiar face not only in Washington, but also at the Library. He joined the Congressional Research Service (CRS) in 1975 on a temporary appointment and retired in 2010 as an energy policy specialist.

A lifelong devotee of vintage jazz — a Tommy Dorsey Orchestra album hooked him in sixth grade — Bamberger started broadcasting weekly on WAMU in 1980 while continuing to work for CRS.

Occasionally, Bamberger also assisted with acquisitions, including the Library’s Jerry Valburn/Duke Ellington collection and the expansive 78 rpm jazz record collection of former Columbia Records executive Robert Altshuler. Bamberger also served as a liaison in acquiring the stunning William P. Gottlieb collection of jazz photographs.

In selecting Beach recordings for the AAPB website, Bamberger was guided partly by his interest in Beach’s take on artists from an era before jazz became an academic discipline and reissues became common.

Sydney Bechet playing at a New York club in 1947. Photo: William P. Gottlieb. Prints and Photographs Division.

Sydney Bechet playing at a New York club in 1947. Photo: William P. Gottlieb. Prints and Photographs Division.Bamberger cites Sidney Bechet, master of the soprano saxophone, as an example. Born in New Orleans, Bechet lived in Europe in the last half of the 1920s.

“I’m curious to hear what Ed says of Bechet,” Bamberger said. “Louis Armstrong has gotten the predominant nod as jazz music’s first great soloist. I suspect that had Bechet been making records then in the U.S., the histories might regard him as Armstrong’s equal.”

In any case, Bamberger said, “The shows are an embarrassment of riches. How do you make choices when you can’t go wrong?”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

February 22, 2023

New Blog Look, Same Great Stories

The Library is coming up on its 223rd birthday in April and we got ourselves a modest present a bit early today: A refresh of our blog sites, to bring you the same great stories in an updated appearance. We can thank you readers for the motivation — readership of the Library’s blogs was up 18 percent last year, to some 5.5. million readers.

For this redesign, we’ve remade the entire look of the blogs, from the headlines to the layouts to the way photographs are featured. The page is cleaner, the reading space wider and overall look more streamlined. You’ll notice how much better this layout displays on your mobile phones and devices — which is important, since roughly half of our readers come to us on their phones.

This change has been in the works for more than a year, said John Sayers, chief of digital and content strategy in the office of communications.

“The Library’s blogs serve a critical role in telling the stories of the Library’s collections and services,” he said. “The blogs continue to be authoritative resources on the subjects they cover, and there are several posts that maintain strong traffic years after publication. Since they serve as the face of the Library to the public at large, we’re delighted to be relaunching them.”

Sayers expressed his gratitude to the Library’s internet technology team and to the more than 125 Library blog writers for their help. “The blog authors are the Library’s ambassadors and storytellers,” he said, “and their work brings to life everything we do.”

Another splashy change you’ll notice is that the landing page for all blogs also has been redesigned, with each blog getting a new signature image. This blog even has a new name, changing from the Library of Congress Blog to “Timeless.” It’s meant to evoke both the reach across the ages that the Library covers (some 4,000 years) in its collections of nearly 200 million items, as well as the future role that these items (and the stories they tell) will play in the nation’s culture.

The rotunda clock and surrounding sculpture in the Library’s Main Reading Room. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith.

The rotunda clock and surrounding sculpture in the Library’s Main Reading Room. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith.Our new signature image, the rotunda clock in the Library’s Main Reading Room, has a nifty story itself. It, and the sculpture that surrounds it, was cast in 1896 and been greeting readers and keeping good time ever since. (It’s wound once a week by technicians in the Architect of the Capitol’s office.) It’s known as “Mr. Flanagan’s clock” for its designer/sculptor, John Flanagan. The name might not sound familiar, but virtually everyone in the nation has seen his work — he also designed the original U.S. quarter.

In the close-up, you’ll see two young people, one reading and one writing, lounging on either side of time itself. It’s a pretty good summation of what a day at your favorite national library is all about.

Subscribe t o the blog— it’s free!February 14, 2023

Jacqueline Katz, Library’s Einstein Scholar

Jacqueline Katz. Photo courtesy of the subject.

Jacqueline Katz is the Library’s 2022–23 Albert Einstein Distinguished Educator. The fellowship program appoints accomplished K–12 teachers of science, technology, engineering and mathematics — the STEM fields — to collaborate with federal agencies and congressional offices in advancing STEM education. She has taught biology and chemistry at Princeton High School in Princeton, New Jersey, for the past 10 years. She began working with the Library last September.

What drew you to science teaching?

I grew up dancing, and it always fascinated me that the actions of microscopic cells and molecules allow for the macroscopic actions of a dancer.

In high school, I felt as if I did not get a chance to develop an understanding of how this connection is possible, so I majored in biochemistry as an undergrad. About halfway through undergrad, I started tutoring and encountered another fascinating puzzle: How can you present scientific information to people who do not process it the same way you do?

Tutoring showed me I could combine my curiosities surrounding the physical abilities of organisms and people’s cognitive abilities as a science teacher. I enrolled in a teacher certification program and figured I would see what happened. Ten years later, I am continually learning new things.

What resources at the Library have captivated you?

In one of my first weeks at the Library, Lee Ann Potter, director of Professional Learning and Outreach Initiatives, took me to meet Manuscript Division historian Josh Levy. He showed me corn kernel samples from the papers of molecular biologist Nina Fedoroff.

The samples made me reflect on the many doors that corn research has opened in the sciences and its major role in our food systems. I then set off on a corn-themed rabbit hole that has taught me so much.

Many of the Library’s collections contain evidence of experiments that outline the evolutionary journey from teosinte, corn’s wild ancestor, to modern-day corn. These experiments were carried out by scientific characters such as Luther Burbank (the Library has his papers) and George Beadle. These stories of corn can be used to help students understand that science is a human endeavor that relates to economics, politics and society.

Luther Burbank in 1890, tending to a bed of cactus plants. Photo: Unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.

What are your stand-out projects so far?

Part of Fedoroff’s collection is born digital, and I worked with Chad Conrady and Kathleen O’Neil of the Manuscript Division to emulate older versions of software Fedoroff used to view documents. Opening some files required a bit of detective work, but we were ultimately able to view Excel spreadsheets of raw data, images taken with scanning microscopes and DNA sequences. I am very excited to bring these resources into the classroom and have my students think like Federoff.

Another project I have been working on in collaboration with Eileen Jakeway Manchester of LC Labs focuses on data as a primary source. I have been able to explore the selected datasets collection and unearth some interesting spreadsheets that will provide students with great opportunities to develop their data literacy.

Both of these projects have expanded what I thought was possible with the Library’s resources.

How are you sharing the resources you’ve discovered with other teachers?

As a part of the PLOI team, I have been given many opportunities to share.

One major outlet is the Teaching with the Library of Congress blog. A blog series now underway explores concepts that traverse all disciplines of science and suggests how primary sources can help elevate these concepts in the classroom.

I also presented at the National Council for Social Studies conference in early December. The ability to get feedback from other teachers in real time has been extremely helpful in my journey. I am looking forward to presenting at several other conferences in the spring and heading back to my home district for a workshop in February.

What do you wish more STEM educators knew about the Library?

I wish more STEM educators saw the Library as a hub of interdisciplinary learning. There are so many rich conversations that can be had surrounding the resources at the Library. Students need to incorporate knowledge from multiple disciplines to make sense of a primary source. The prospect of this type of interdisciplinary thinking has been incredibly motivating to me as a teacher.

I would urge other teachers to come to the Library to expand the way they think about their content area. You never know what you will find and the connections that can be made.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

February 9, 2023

Burt Bacharach, Gershwin Prize Winner: A Fond Farewell

The Library’s Mark Hartsell, in the Communications Office, and Mark Horowitz, in the Music Division, contributed to this post.

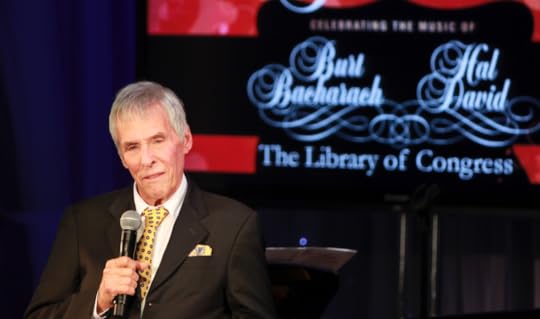

Burt Bacharach, the elegant songwriter and composer whose lifetime of work the Library honored with the 2012 Gershwin Prize for Popular Song, died yesterday in Los Angeles. He was 94.

Bacharach’s iconic career stretched for more than half a century, co-writing hits with lyricist Hal David (the pair shared the Gershwin Prize) that seemed to defy age or pop trends. His first big break in the 1950s was touring with show biz legend Marlene Dietrich; in the 21st century, he was working with rap impresario Dr. Dre and English singer/songwriter Elvis Costello. In between, he won eight Grammys, three Oscars and an Emmy.

“His songs were a uniquely American imprint on popular music and a testament to the power the creative spirit has to unify and uplift people all over the world,” said Carla Hayden, the Librarian of Congress.

Hits came for decades, most particularly in the 1960s and 1970s, with easy-on-the-ear melodies found in “Alfie,” “I Say a Little Prayer,” “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again,” “Walk on By” and the Oscar-winning “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head.”

He was a noted perfectionist and often said that he and David wrote only one song in a single day (“I’ll Never Fall In Love Again.”) The rest of his arrangements were crafted and then chiseled. “Songs that sound simple are deceptive,” he told The Guardian, the British Daily, in 2015. “It’s a very complicated process.”

The results were admired by musicians and adored by audiences. His songs were recorded by hundreds of artists, from Elvis Presley to Aretha Franklin to Frank Sinatra. His favorite interpreter was Dionne Warwick. Over time, his and David’s work became, much like the songs of George and Ira Gershwin, part of the American songbook.

The Gershwin Prize in 2012 was so meaningful to him that in his memoir, “Anyone Who Had a Heart,” published the following year, the final chapter was “The Gershwin Prize.” During his two-day visit to the Library, he spent nearly an hour discussing his work with the Music Division’s Mark Horowitz. (David, who had a stroke a few weeks before the concert, was unable to attend. He died in September of that year.)

The show, performed in the Library’s Coolidge Auditorium, began with host comedian and Bacharach fan Mike Myers in tuxedo, crooning Bacharach and David’s “What’s New Pussycat?” He first channeled through the song through his Austin Powers character, a natural fit since Myers had gotten Bacharach to make cameos in the Austin Powers films. Myers then crossed to performing the song as the soulful Tom Jones. Stagehands ran out to rip off his tear-away tuxedo, revealing a blue Elvis-style jumpsuit secured by a giant buckle bearing a name: Burt.

The artists who performed his songs as tributes that night showed off his range — jazz singer Diana Krall; pop star Sheryl Crow; the hard-to-define Lyle Lovett; and previous Gershwin Prize winner Stevie Wonder.

“I have followed you since I was a little boy,” Wonder said as he sat at the piano, playing and musing. “I’ve loved your music. I loved the chord structures. They inspired me so much — the words, the lyrics.”

Burt Bacharach at the 2012 Library of Congress Gershwin Prize for Popular Song, when he and lyricist Hal David were inducted.

Bacharach ended the evening by leaning against the piano on stage, talking about his carer.

It was clearly a touching moment for a man who’d been in the spotlight before the dawn of the rock era. He recounted that when a journalist had asked him to put the Gershwin Prize in context of all his many awards, he listed it at the top.

“The Academy Award is just for one song or one score,” he said, recounting the conversation. “This award was for all of my work, and so for me, it was the best of all awards possible, and I meant that with all my heart.”

Warwick closed the show with “What the Words Needs Now is Love.” It was a fitting end to the night, and a fitting epitaph to his lifetime of work.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

February 8, 2023

NLS Shares Ukrainian Books to Aid War Refugees

People fleeing the war in Ukraine in March 2022, crossing into Moldova. Photo: UN Women/Aurel Obreja.

This is a guest post by Claire Rojstaczer, a writer-editor in the National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled. It recently appeared in slightly different form in the Library’s Gazette.

Since Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, a flood of Ukrainian refugees has washed over Europe. The National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled has found a way to help those distant refugees — thanks to an earlier wave of Ukrainian immigrants who settled in Cleveland, Ohio, some one hundred and forty years ago.

“I was attending a … meeting for the [International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions] section for libraries serving people with print disabilities in July when someone brought up the shortage of accessible Ukrainian-language books for refugees,” said Kelsey Corlett-Rivera, an NLS foreign language librarian.

She remembered that NLS had a selection of books in Ukrainian but held off on speaking up — she wasn’t sure that the NLS would be able to share them.

Since 2019, the United States has been a member of the Marrakesh Treaty, which allows it to exchange special-format books with other signatory nations even when those materials are under copyright. However, the treaty only allows NLS to share books it produced — which was indeed the case for the NLS Ukrainian collection.

“It turned out that almost all those books were produced by the Cleveland Society for the Blind on contract for the local NLS network library in the 1980s and ’90s,” Corlett-Rivera says. Cleveland has one of the largest and most established Ukrainian immigrant communities in the United States, with the first wave of immigrants coming in the 1870s and 1880s and settling on the west side of the city, according to the “Encyclopedia of Cleveland History,” researched and published by Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland.

During a follow-up meeting in September, Corlett-Rivera shared the good news with nations hosting refugees. “The main country excited was Lithuania,” she says, “but Finland, Norway and Germany also expressed interest.”

The Cleveland Society for the Blind tapes are just a small part of the foreign language collection at NLS’ Multistate Center East, a storehouse for books and other NLS materials located in Cincinnati. This collection, which includes approximately 900 Ukrainian books, is on cassette tapes, an analog format that NLS began phasing out 15 years ago — but MSCE employee Quincy Jones has been slowly working to digitize them. Once Jones converts a book from cassette, the digital files are uploaded to BARD, the NLS Braille and Audio Reading Download website.

It takes an additional round of format conversion to make the Ukrainian titles that Jones has digitized ready for upload to the Global Book Service of the Accessible Books Consortium , the online catalog that supports the practical implementation of the Marrakesh Treaty. That’s because NLS uses a different accessible book format than most of the world.

Sometimes cataloging works in foreign languages poses challenges for NLS staff, but not in the case of Ukrainian. Anita Kazmierczak, head of the NLS Bibliographic Control Section, speaks Ukrainian — so she was able to listen and confirm that the books matched their catalog records.

By year’s end, 59 NLS Ukrainian titles were available for download from GBS by authorized entities in Marrakesh signatory countries. They range from translations of world literature, such as short stories by Agatha Christie and Ernest Hemingway, to original Ukrainian works, including the poems of Taras Shevchenko, known as the father of Ukrainian literature.

“We’re delighted,” says Monica Halil Lövblad, head of the Accessible Books Consortium in Switzerland. “Now any of our participating ABC libraries located in countries that have implemented the Marrakesh Treaty looking for books in Ukrainian can immediately get them.”

Corlett-Rivera hopes to eventually add more and is also looking into other languages that NLS can contribute. “We have U.S.-produced Hungarian and Romanian collections we could share, too,” she says.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers