Library of Congress's Blog, page 27

December 21, 2022

How “It’s a Wonderful Life” Almost Never Happened

James Stewart and Donna Reed, center, in a famous scene from “It’s a Wonderful Life.” Photo: RKO publicity still.

Elizabeth Brown is a reference librarian in the Researcher and Reference Services Division. This article appears in the Library of Congress Magzine , Nov.-Dec. 2022.

Perhaps the most beloved Christmas film of all time got its start during a morning shave.

Philip Van Doren Stern, while getting ready for work one day in 1938, had an idea for a story: A stranger appears from nowhere to save a husband and father from a suicide attempt on Christmas Eve, restoring his joy of living by helping him realize his value to others.

Stern, an author and editor, eventually wrote a draft that he polished periodically and, in 1943, shared with his literary agent. It didn’t sell.

But Stern still liked the little story, so he had 200 copies printed as a pamphlet titled “The Greatest Gift: A Christmas Tale” and sent most of them out as holiday cards — and two to the U.S. Copyright Office at the Library of Congress.

Good Housekeeping ran this short story in January 1945, “The Man Who Was Never Born,” which became the basis for the film, “It’s a Wonderful Life.” Serial and Government Publications Division.

The next year, RKO Radio Pictures bought the film rights for $10,000 as a vehicle for Cary Grant. Film rights helped: The story was published by two magazines and as a book in 1944 and 1945.

But film scripts proved unworkable, and RKO sold the rights to Frank Capra’s newly formed Liberty Films. With a new script, a new star in Jimmy Stewart and a new title in “It’s a Wonderful Life,” the film finally got made.

Despite earning five Oscar nominations, “Wonderful Life” lost money and, in 1948, Capra sold Liberty Films to Paramount. Ownership of the film changed a few more times and, in 1974, National Telefilm Associates failed to renew its copyright. With no royalty fees required, TV stations aired the film repeatedly, and “Wonderful Life” became a holiday favorite — while earning nothing for its owner. In 1994, its next owner, Republic Pictures, restored the copyright through court action, and Paramount bought it back in 1998.

Today, Library collections hold items that chronicle the “Wonderful Life” story: the original Stern pamphlet, magazines that published early versions of the tale, the continuity script from the film, promotional posters for the movie and more.

What a wonderful life it has been for a story that nobody wanted to publish. (You can read more about the life of “It’s a Wonderful Life” in this post by Samantha Kosarzycki, a former legal intern in the Copyright Office.)

The first page of the script of “It’s a Wonderful Life.” Motion Picture, Film & Recorded Sound Division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

December 19, 2022

Library Acquires Rare Codex from Central Mexico

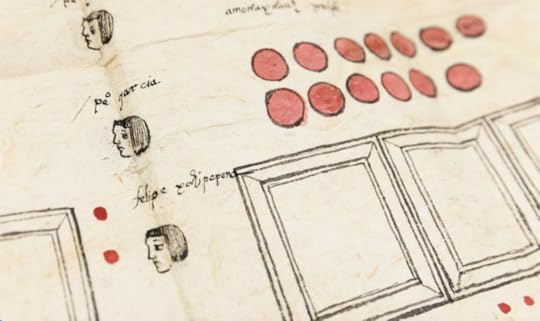

This drawing from the San Salvador Codex shows the portraits and names of Indigenous workers next to the amount in pesos (red circles) they were underpaid. Geography and Maps Division.

Theft, fraud, harassment, withholding of payment — courts around the world hear these charges all the time. Yet, they’re far from modern. The Library’s newly acquired San Salvador Huejotzingo Codex, for example, documents a legal proceeding from 1571 in which Indigenous Nahuatl officials in central Mexico accused their village’s Spanish administrator of these very same crimes.

The Library purchased the rare codex this fall. It contains new details about the earliest legal structures in Mexico after Spanish colonization and the way Indigenous people used Spanish laws to defend their rights. The codex is one of only six 16th-century pictorial manuscripts from central Mexico known to still exist. With its acquisition, the Library now holds three of the six manuscripts.

“The San Salvador Codex adds significantly to the Library’s collection of Indigenous manuscripts from the early contact period,” said John Hessler, recently retired from the Geography and Map Division. “It is by any measure a world-class acquisition.”

The manuscript has 96 pages on 48 folios and includes six foldout drawings in Mixtec and Nahuatl hieroglyphs in red, yellow, coffee, green, blue and black carbon ink. Written by at least two different Indigenous hands, the hieroglyphs illustrate charges against Alonso Jiménez, the canon of San Salvador, a village to the south of Mexico City. Jiménez, a church official, administered the village on behalf of Spanish colonial authorities.

Two lawsuits arose after a colonial inspector arrived in San Salvador unannounced in 1570 to assess how well it was being managed. The Indigenous people reported mistreatment and harassment of their nobles and accused Jiménez of charges including refusing to pay for the services of artisans, charging for woolen blankets meant to be free, taking more corn than the church was entitled to and stealing textiles.

“It gives you insight into this village, what life was like in this village,” Hessler said. “People are helping the canon make his furniture. They’re farming corn and getting woolen blankets, and they’re also being exploited. We get a real sense of the everyday out of this document, which makes it so important.”

One drawing depicts different amounts of maize, tortillas and other foodstuffs provided to Jiménez as tribute from 1570 to 1571. Another drawing features the faces and names of carpenters not paid for constructing the local church and making Jiménez’s furniture. Yet another represents the value of paintings done for him in tortillas — it shows how many tortillas each painting was worth.

Robert Morris, a G&M acquisitions specialist, alerted Hessler that the codex was available for purchase in 2019. The news came as a complete surprise.

Before the codex came on the market, scholars didn’t know of its existence. “It does not appear on any of the inventories of Mesoamerican manuscripts or Indigenous drawings,” Hessler said.

On top of that, only three colonial-era manuscripts with Indigenous drawings, plans or maps have come up for sale in the past century.

“It is a super-rare opportunity when one gets a chance to buy something like this,” Hessler said. “We have been so lucky in the last five years to purchase two of these, the Codex Quetzalecatzin and also this one.” The Library acquired the 1593 Codex Quetzalecatzin in 2017.

After learning of the San Salvador Codex’s availability, Hessler set out to investigate its authenticity and provenance. He consulted experts, the most prominent being Baltazar Brito Guadarrama, director of Mexico’s National Anthropology Library. Early on, Guadarrama examined a digital copy of the codex provided by the Basil, Switzerland, antiquarian manuscripts dealer conducting the sale.

Hessler traced the provenance of the codex to 19th-century France, where an aristocratic family long owned it. More recently, a Texas collector purchased it, then sold it to the Swiss antiquarian dealer. A few months before the Library purchased the codex, the dealer flew it to the Library, where Conservation Division experts viewed it under ultraviolet light. Library curators, including Hessler, also examined it.

“The manuscript is solid in its provenance,” Hessler said. “It looks like what it’s supposed to be.

Like the San Salvador Codex, one of the Library’s other 16th-century central Mexican pictorial manuscripts — the 1531 Huexotzinco Codex, acquired in the late 1920s as part of the Edward S. Harkness Collection — also narrates a legal dispute. It features testimony against representatives of the Spanish colonial government by the Nahua people of Huexotzinco.

Although it originates beyond central Mexico, yet another colonial-era map at the Library, the Oztoticpac Lands Map, is a Nahua pictorial document drawn for a court case in the city of Texcoco around 1540.

What makes the newly acquired San Salvador Codex remarkable is its completeness, Hessler said. The Huexotzinco Codex presents only the Indigenous side of a dispute, while the Oztoticpac Lands Map is just a map and, again, contains only Indigenous testimony.

The San Salvador Codex, on the other hand, has all the information about the lawsuits involved: the Indigenous testimony in Nahautl, the canon’s defense in Spanish, signatures of the parties, drawings and even the verdict.

The court acquitted the canon on some charges and found him guilty of others. As part of his penalty, he had to pay two pesos of gold to be shared among people who provided him with six jars fig tree oil.

“It’s incredible, both in its detail and in the fact that you have the complete story,” Hessler said. “From that perspective, it is rare.”

The codex arrived at the Library from Basil on Sept. 23. In early October, several experts including Guadarrama came to the Library to view it.

“Guadarrama, who has spent his career looking at manuscripts like this, was moved to tears on seeing it in person,” Hessler said.

The Library is now scanning and cataloging the codex to make it available online.

As for Hessler, he retired from the Library on Oct. 31.

“This was a great way to go out, I have to say,” Hessler said. “In my career, it’s one of the top two or three acquisitions I ever made.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

December 14, 2022

“Iron Man,” Marvel, Rocket Into the 2022 National Film Registry

Marvel Studios President Kevin Feige was excited, explaining why he and his filmmaking team were thrilled that their cornerstone feature, 2008’s “Iron Man,” was being inducted into cinematic Valhalla, the Library’s National Film Registry, in the class of 2022.

“All of our favorite movies are the ones that we watch over and over again, and that we grow up with,” he said in an interview with the Library. “Almost 15 years after the release of ‘Iron Man’… to have it join the film registry tells us it has stood the test of time and it is still meaningful to audiences around the world.”

The Library’s annual list of 25 designated for preservation for their cultural, historic or aesthetic value to the nation always brings a list of studio hits, independently made features, powerful documentaries and even home movies into the canon. This year’s inductees cover 124 years, from 1898 to 2011. It include hits such as “When Harry Met Sally,” “Carrie” and “House Party”; documentaries such as “Mingus” and “Union Maids”; shot-on-a-shoestring features such as “The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez” and “Pariah”; and even the home movies of mid-century entertainer Cab Calloway.

“Films have become absolutely central to American culture by helping tell our national story for more than 125 years,” said Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden. “We’re grateful to the entire film community for collaborating with the Library of Congress to ensure these films are preserved for the future.”

The 2022 selections include at least 15 films directed or co-directed by filmmakers of color, women or LGBTQ+ filmmakers. The selections bring the number of films in the registry to 850, many of which are among the 1.7 million films in the Library’s collections.

One of the iconic scenes in “When Harry Met Sally,” a film including in this year’s National Film Registry. Photo: Castle Rock Entertainment.

Other highlights: The original “Hairspray” from 1988, featuring Ricki Lake and directed by John Waters; “The Ballard of Gregorio Cortez,” featuring a young Edward James Olmos; and the 1950 version of “Cyrano de Bergerac,” which made José Ferrer the first Hispanic actor to win an Oscar for Best Actor. The first Native American film on the registry is this year’s “Itam Hakim, Hopiit” (“We/someone, the Hopi”) from Victor Masayesva Jr., Hopi director and cinematographer.

Documentary filmmaking legend Julia Reichert, who died of cancer earlier this month, learned a few weeks earlier that “Union Maids,” a 1976 documentary she co-directed, was being inducted.

“Even though ‘Union Maids’ was a black & white, super low-budget film, with interviews shot on open reel videotape to save money, the film has shown remarkable staying power,” Reichert emailed, in response to questions, days before she passed away. She co-directed the film with Jim Klein and Miles Mogulescu.

Turner Classic Movies will host a television special Tuesday, Dec. 27, starting at 8 p.m. ET to screen a selection of motion pictures named to the registry this year. Hayden will join TCM host, film historian and Academy Museum of Motion Pictures Director and President Jacqueline Stewart, chair of the National Film Preservation Board, to discuss the films.

“I am especially proud of the way the Registry has amplified its recognition of diverse filmmakers, experiences, and a wide range of filmmaking traditions in recent years,” Stewart said. “I am grateful to the entire National Film Preservation Board, the members of the public who nominated films, and of course to Dr. Hayden for advocating so strongly for the preservation of our many film histories.”

Actress Sissy Spacek said she was unaware she was holding her arms out from her side with palms upraised in this “Carrie” scene, giving her a witch-like appearance.:”I was in the moment of being the prom queen.” Photo: Red Bank Films

Sissy Spacek, the star of “Carrie,” makes her third appearance on the registry, joining her earlier films “Badlands” and “Coal Miner’s Daughter.” Her role as Carrie White, the telekinetic teen misfit who is abused by her mother and taunted by her classmates, drew an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress and a lasting image in pop culture as a vengeful, blood-soaked prom queen.

She credits Stephen King’s novel, the basis for the film, as striking a nerve with teenagers in each generation who are desperate to fit in with their peers for the film’s lasting resonance. The other factor, she said, was a superb cast that included Piper Laurie (also nominated for an Oscar), John Travolta and Amy Irving.

“Brian De Palma was just such a wonder to work with,” she said in a recent interview, crediting the film’s director. “He would tell us exactly what he needed and then he’d say, ‘Within those parameters, you can do anything you want. That was just so wonderful.”

Several selections were defining works in their genres. Among romantic comedies, “When Harry Met Sally” from 1989 is a classic — Vanity Fair named it this year as the best American rom-com ever made — that brought together several major talents. Screenwriter Nora Ephron, director Rob Reiner, actor Billy Crystal and actress Meg Ryan all cemented their status in pop culture fame with the film.

“I just felt so plugged into the process of making the movie,” Crystal said in an interview. “…not that anything is every easy, but it was just such a joy to see it come to life.”

“Super Fly” stars Sheila Frazier and Ron O’Neal in a famously stylish scene from “Super Fly,” a 2022 NFR inductee. Photo: Warner Bros.

“Hairspray,” the quirky story of a plus-sized Baltimore teen and her friends integrating a local television dance show in the early sixties, wasn’t a huge success at first but has gone on to have a life of its own. It was remade as a Tony Award-wining musical on Broadway, a megahit musical film in 2007 and a live TV version in 2016. But in John Waters’ 1988 original, it was an 18-year-old Ricki Lake who was first tapped to play the lead role of Tracy Turnblad.

“I didn’t even really process that I was the star of the movie,” Lake said in a recent interview from her home in Malibu, “until the movie was made and we were seeing right before it came out. I was like, ‘Oh, WOW.”

Among Latino films, “The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez” from 1982 is one of the key feature films from the 1980s Chicano film movement. Edward James Olmos was a working actor but not yet a star when he and several friends, meeting at what would become the Sundance Film Festival, decided to make a film about a true story of injustice from the Texas frontier days.

Shot on a tiny budget for PBS, “The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez” accurately tells the story of a Mexican-American farmer who in 1901 was falsely accused of stealing a horse. Cortez killed the sheriff who tried to arrest him, outran a huge posse for more than a week, barely escaped lynching and was eventually sentenced to more than a decade in prison. The incident became a famous corrido, or story-song, that is still sung in Mexico and Texas.

“This film is being seen more today than it was the day we finished it,” Olmos said in an interview. “‘The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez’ is truly the best film I’ve ever been a part of in my lifetime.”

“House Party” joins the registry as a 1990 comedy landmark, as it put Black teenagers, hip-hop music and New Jack swing culture directly into the American cultural mainstream. It spawned the pop-culture careers of stars Kid ‘n Play, sequels and imitations — and the career of Reginald Hudlin, its writer and director. Hudlin is now a major player in Hollywood — but “House Party” was his first film.

“The day we shot the big dance number in ‘House Party’ is easily one of the best days of my life,” he said in a recent interview, still gushing about how much fun it all was. “We had all the enthusiasm in the world, all the commitment in the world.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

December 7, 2022

Jurij Dobczansky: Working with Libraries in Ukraine During War

Photo courtesy of Jurij Dobczansky.

Jurij Dobczansky is a senior cataloging specialist in the East Central Europe Section of the Germanic and Slavic Division.

Tell us about your background.

Growing up in New Haven, Connecticut, I spoke Ukrainian at home until I went to kindergarten. My parents were World War II refugees from Ukraine. After regular school hours, I attended a community-run Ukrainian school for 10 years. There, I learned about my cultural heritage by reading and writing in the Ukrainian language.

In 1975, I earned a bachelor’s degree in comparative European literature from the College of the Holy Cross. Soon after graduation, I came to Washington, D.C., to work as a volunteer for a committee in defense of human rights.

What brought you to the Library, and what do you do?

In December of that year, I accepted a temporary appointment to the Theodore Roosevelt film project in the Prints and Photographs Division. My supervisor encouraged me to pursue library studies while working full time. A permanent position compiling the annual “American Bibliography of Slavic and East European Studies” offered me a chance to develop new skills while I attended evening classes.

I earned a master’s degree in library science from the Catholic University of America in 1981. In 1983, I began my cataloging career as a Slavic subject cataloger in the Social Sciences Section. Continuing to work with the languages and cultures I was familiar with, I joined the Central and East European Languages team. It has been an ongoing educational journey. I presently work with Ukrainian and Polish resources in a wide variety of subjects.

How has the war in Ukraine affected Library collecting?

The war effectively cut off our contacts with several of the Library’s exchange partners. Our commercial vendor suspended shipping in April but was able to resume in June. Remarkably, the Ukrainian postal service continued to function. In fiscal 2022, our section received over 1,700 items from Ukraine.

The senseless and unprovoked war against Ukraine began in 2014 with the occupation of Crimea and the invasion of its Donbas region. Then, as everyone knows, Russia launched a full-scale invasion on February 24 of this year.

The war has affected me personally and professionally. Over the years, I have worked methodically to develop accurate subject and descriptive access to Ukrainian resources. It pains me to see the wholesale destruction of Ukraine’s cultural institutions and heritage; places for which I established name authority records are disappearing.

Besides military targets, Russia has destroyed libraries, archives, museums, hospitals, schools and civilian housing. Yet amid the bombing, annual book festivals continued in Kyiv and Lviv. A large contingent of Ukrainian publishers participated in the Frankfurt Book Fair.

As the ongoing documentation of Russian atrocities and war crimes proceeds, we at the Library must likewise continue to collect and preserve manifestations of Ukraine’s cultural heritage. After the war, I hope the Library will assist in rebuilding and restoring Ukrainian libraries.

What projects are you most proud of?

Especially gratifying to me are special assignments, details to other divisions and translation projects. From 1994 to 1996, I felt privileged to participate in the Congressional Research Service’s parliamentary assistance program in Ukraine, which included three trips to Ukraine.

As a docent, I have enjoyed leading tours of the Jefferson Building for members of the Embassy of Ukraine and delegations from Ukraine, including those of Ukrainian first ladies Lyudmyla Kuchma and Maryna Poroshenko.

Occasionally, I have come across items in the collection, which turn out to be rare. Especially rewarding was processing collections of Ukrainian ephemera related to the Orange Revolution of 2004 and the Euromaidan Protests of 2013 and 2014.

What do you enjoy doing outside work?

My favorite activities at home are gardening and landscaping. For over three decades, I have taught the art of pysanky — Ukrainian Easter eggs — at an annual workshop. For many years, I also enjoyed singing as a member of the Library of Congress Chorale. My wife and I sing in our church choir and in a local Ukrainian a cappella group.

What is something your co-workers may not know about you?

On Sept. 18–20, 2015, I organized the fifth meeting of the Ukrainian Heritage Consortium of North America, an informal network of Ukrainian American museums, libraries and archives. The meeting included an all-day program at the Library. I am ever grateful to several Library staff members for their valuable assistance and presentations. Since 2012, I have also chaired the Archives and Library Committee of the Shevchenko Scientific Society, a scholarly organization of Ukrainian specialists based in New York City.

Jurij Dobczansky is a senior cataloging specialist in the East Central Europe Section of the Germanic and Slavic Division.

November 28, 2022

My Job: Jeffrey Lofton

Jeffrey Lofton. Photo: Alyona Volgelmann.

Jeffrey Lofton is senior adviser to the Library’s chief human capital officer.

Tell us about your background.

I hail from Warm Springs, Georgia, best known as the home of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Little White House and ubiquitous red claylike soil.

I attended LaGrange College and studied the more-useful-than-I-imagined triad: speech, communications and theater. Later, I earned a master’s degree in public administration from the University of Nebraska (the beginnings of scratching a public-sector itch) and a master’s in library and information science from Valdosta State University.

What brought me to Washington, D.C.? It was my first career as a professional actor. I spent many a night trodding the boards of D.C.’s theaters and performing arts centers, including the Kennedy Center, Signature Theatre, Woolly Mammoth and Studio Theatre. I even scored a few television appearances, including a Super Bowl halftime commercial that my accountant wisecracked was “the finest work” of my career. My luck to find a CPA who longed to moonlight at comedy clubs.

What brought you to the Library, and what do you do?

After I left acting — much to the delight of my parents whose echo-chamber plea was always, “When will you get a real job?” — I spent the next few years as an account manager with public relations firms, many of my clients being nonprofits of various descriptions. My aforementioned parents were never quite sure what being a PR account manager entailed, but it met their chief criterion: I wasn’t cavorting about on stage or screen.

I realized over time that my heart truly was in public service, so when I saw a public affairs position with the Library’s Veterans History Project advertised, I applied with both alacrity and soberingly low expectations. Amazingly (to me), I got the job. They must have liked my bow tie, I reasoned.

I worked as a congressional liaison, program manager and section head those early years. Next, I was chief of the Employee Resources Management and Planning Division. All of that led me to my current role as senior adviser to the chief human capital officer. I just marked my 18th year at the Library, which remains my dream work home.

What are some of your standout projects?

I created the FutureBridge mentoring program and managed it for about 10 years. We envisioned it as the premiere professional development program for what was then called Library Services. It continues as a resource for employees Librarywide.

I also worked on the team that shaped the VIBRANT initiative, which is a blueprint and strategic path to enable our workforce to thrive and flourish in a future increasingly defined by disruptive forces. VIBRANT stands for virtual, interdependent, balanced, resilient, ardent, nimble and talented — all of which, together, comprise a dynamic and results-driven workforce. I am very proud of both FutureBridge and VIBRANT.

What do you enjoy doing outside work?

Writing (and, of course, rewriting), which is a lifelong avocation. Having grown up in the Deep South, I came to appreciate a good story very early. And now I like to tell them myself. I also enjoy playing and snuggling with our toy poodle, Petunia. I strive in life to be as good a person as she thinks I am.

What is something your co-workers may not know about you? Hmmmm. Well, I’m delighted to report that my debut novel “Red Clay Suzie,” inspired by true events, will be released this winte as a hardcover, digital and audio book.

What’s “Red Clay Suzie” about, you may ask? In one sentence: Fueled by tomato sandwiches and green milkshakes and obsessed with cars, my protagonist, Philbet, struggles with life and love as a gay, physically misshapen boy in the Deep South. Christopher Castellani, author of “Leading Men” calls the novel “an arresting debut … a vivid depiction of a unique childhood that feels universal in its longing.”I used the Library’s collections in my research for “Red Clay Suzie,” and it’s amazing how much one can glean from our online resources. In particular, I learned a great deal about the topography of the central Georgia region that is the setting for most of the book. I also drew inspiration from dialogue I read in some of Zora Neale Hurston’s play scripts, fully accessible on the Library’s site. I was even able to listen to VHP interviews, including several that my mother conducted with veterans who hailed from my hometown, where “Red Clay Suzie” takes place. Exciting times ahead!

November 23, 2022

My Job: Katie Klenkel, Connecting Visitors to the World’s Largest Library

Katie Klenkel. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Describe your work at the Library.

I’m the chief of the Visitor Engagement Office. I oversee a team of people — both staff and volunteers — who welcome thousands of visitors to the Library’s public spaces and exhibitions each day.

In addition to acting as front-line customer service, we also help visitors connect to the Library on a personal level and become lifelong users of our services and resources. Sometimes that connection is made through a guided experience or a public program, but more often it’s through a one-on-one interaction with a volunteer.

I also support special projects, such as expanding our evening hours, recruiting and training volunteers, updating wayfinding signage and building resources as well as hundreds of other tasks designed to improve every visitor’s experience.

How did you prepare for your position?

I traveled a bit of a winding road to get here. I started my career in building and event management and visitor services in higher education, with roles at the University of Maryland, the Catholic University of America and George Mason University.

I transitioned to the Library in 2015 as the public programs manager and, after four years in event and program operations, moved to program administration for the Center for Learning, Literacy and Engagement.CLLE. I became chief of Visitor Engagement in December 2020, just as we were ramping up plans to reopen to the general public. I think a lot of the qualities needed to succeed in a higher-education space (enthusiasm, flexibility, a positive attitude) translated well to visitor engagement.

What are some of your standout projects?

I will never forget the effort and dedication it took for our team to reopen the Library to the general public after the March 13, 2020, COVID-19 closure. We came back in July 2021 with timed-entry passes, capacity restrictions, virtual volunteering and masking requirements. I’m extremely proud of the way we slowly and steadily restored operations without having to drastically alter or roll back our plans.

The project involved dozens of staff members from across the Library, including leadership from the director of our center. We could not have successfully reopened without the support of the Health Services Directorate, the Security and Emergency Preparedness team and so many others. We safely restored on-site volunteering in December 2021, which was a huge milestone for us — it doesn’t feel like the Library without our dedicated volunteers.

What have been your most memorable experiences at the Library?

Some of my favorite memories have been one-on-one interactions with our incredible visitors. I’ll never forget the father-daughter duo that drove all the way from Indiana for her 16th birthday so she could get her Library of Congress researcher card and study in one of our reading rooms. I also remember a lovely couple that flew in from Atlanta for their 40th anniversary to see the Library, because the woman was a lifelong public librarian and had always wanted to visit.

And even small moments, like when I manage the line outside of the building and there are young kids bouncing with excitement because they can’t wait to see the “biggest library ever.” It’s a daily reminder to appreciate how special this place really is.

November 10, 2022

Lakota “Winter Count” Artistry

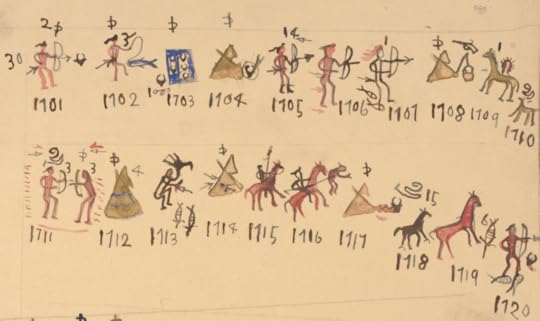

Detail from the Lakota winter count. Manuscript Division.

The winter counts created by some Native American peoples chronicle centuries of their history in pictures: battles fought, treaties struck, buffalo hunts, meteor showers, droughts, famines, epidemics. The counts — painted mostly on buffalo hides until the species was hunted to nearextinction in the late 19th century — served as a way for tribes of the Great Plains to document significant events and pass a record of them from generation to generation. Each year, a band’s elders would choose the most important event in the life of the community. The winter count keeper — generally, a trusted elder — would paint a scene on the hide to represent it, adding to the years of images that came before. Each individual image is called a “glyph.”

One such keeper was Battiste Good, born around 1821 under the name Wapostan Gi, or Brown Hat. Good was a member of the Sicangu (or Brulé) Lakota, who at the time inhabited the plains west of the Missouri River in present-day South Dakota and Nebraska. In 1868, Good was present at the signing of the Treaty of Fort Laramie, under which the Lakotas surrendered many thousands of acres of their lands in exchange for the establishment of the Great Sioux Reservation — a large part of what’s now western South Dakota, including the sacred Black Hills.

In 1878, the Rosebud Agency was officially established in South Dakota, and the U.S. government began relocating bands of Sicangus and Oglalas to the new agency. While there, Good copied his winter count into a drawing book given to him by William Corbusier, a U.S. Army surgeon. He introduced Arabic numerals to the count and labeled each event by year — the entry for 1868 shows Good himself shaking hands with Gen. William Harney following the signing of the Laramie treaty. Good died in 1894, and the responsibility of the winter count fell to his son, High Hawk. In 1907, he used watercolor, pen, ink and paper to produce the copy of the Good winter count shown below. High Hawk’s work eventually was donated to the Library’s Manuscript Division, where today it chronicles a history long gone by but not forgotten.

Two colorful lines from the winter count, each depicting a decade with one drawing above each year. Manuscript Division.

November 9, 2022

Harjo, Library Honored by Native American Tribal Association

Joy Harjo walks onstage for a performance of poetry and music at the Library. Photo: Shawn Miller.

The Association of Tribal Archives, Libraries, and Museums has presented one of its most significant awards to the Library and former U.S. Poet Laureate Joy Harjo for “Living Nations, Living Words,” Harjo’s signature project during her 2019 to 2022 term.

Harjo, the first Native American to hold the nation’s poet laureate position, was honored with the ATALM’s Outstanding Project/Non-Native Organization Award for her work that shows the dynamic, living poetry being written and performed by Native Americans across the country. The project features 47 Native American poets through an interactive StoryMap and a newly developed Library audio collection. The map is marked by dots showing the home region of each Native poet and features their photo, biography and a link to hear them recite and talk about one of their works.

“I conceived the idea of mapping the U.S. with Native Nations poets and poems,” said Harjo, an enrolled member of the Muscogee Nation. “I want this map to counter damaging false assumptions — that Indigenous peoples of our country are often invisible or are not seen as human. You will not find us fairly represented, if at all, in the cultural storytelling of America, and nearly nonexistent in the American book of poetry.”

As part of the project, Harjo edited a companion anthology, also titled “Living Nations, Living Words,” published in 2021 by the W. W. Norton & Company in association with the Library. Harjo also edited “When the Light of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through: A Norton Anthology of Native Nations Poetry,” published by W. W. Norton & Company in 2020.

The ATALM presented the award during its October annual meeting, saying it “applauds Harjo’s work to illuminate the poetry of Native America and expresses its gratitude to the Library of Congress for a living tribute to a vibrant culture.”

Accepting the award alongside Harjo was Lori Pourier, president of the First Peoples Fund and member of the Board of Trustees for the Library’s American Folklife Center. Pourier (Oglala Lakota), an enrolled member of the Oglala Sioux Tribe, offered remarks on behalf of Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden.

The ATALM’s Guardians of Culture and Lifeways International Awards Program identifies and recognizes organizations and individuals that serve as outstanding examples of how Indigenous archives, libraries, museums and individuals contribute to the vitality and cultural sovereignty of Native Nations. The Guardian Award takes its name from the sculpture that stands atop the Oklahoma State Capitol — the work of Seminole Chief Kelly Haney.

For more information about the Poet Laureateship as well as other poetry and literature programs of the Library, visit the Poetry and Literature website.

November 8, 2022

Vote!

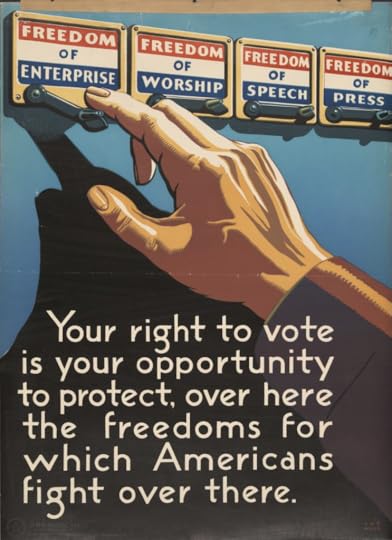

A 1943 poster encouraging Americans to vote during World War II. Artist: Chester R. Miller. Prints and Photographs Division.

This civic poster from the days of World War II is always a good reminder that the right to vote is something that millions of Americans have fought to earn, protect and defend. It cost something. So, as we always do on Election Day, we encourage you to exercise that right. Vote your conscience. We keep the blog short to give you more time to get there. We’ll see you later in the week.

November 3, 2022

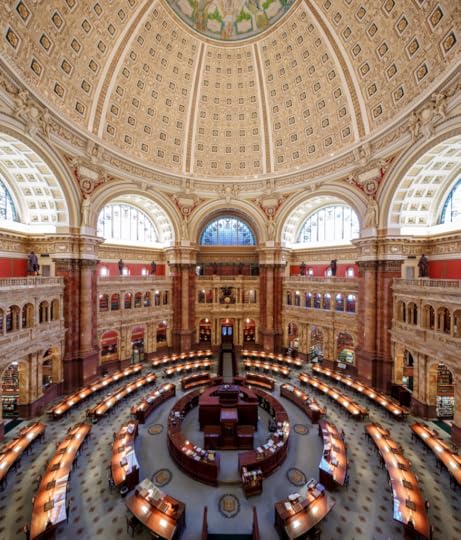

The Library’s Jefferson Building: 125 Years Old and Loving It

Design for Library’s Jefferson Building, between . Smithmeyer and Pelz. Prints and Photographs Division.

The morning of Nov. 1, 1897, dawned warmish and wet in Washington, D.C. — heavy rains were predicted through the evening. But the gray skies failed to dampen the spirits of readers anticipating a long-awaited event: the opening of the new and reportedly fabulous Library of Congress reading room.

When a watchman began allowing visitors inside at 9 a.m., an achievement a quarter century in the making came to pass: The U.S. had a national library set to rival any other, both in splendor and in function.

This November, the Library is celebrating the 125th anniversary of that milestone.

The road toward it had more than a few twists and turns, to put it mildly. But, in the end, it led to a stunning monument to America’s turn-of-the-20th-century ambitions and creative ingenuity.

As those first readers filed into the building that rainy Nov. 1, they began to grasp why popular magazines had been writing about the wonders of the new structure for months. They saw the Library’s granite exterior and imposing size; the flame of learning atop a brilliant 23-carat-gold-plated dome; and some of the artwork and sculpture that left observers breathless.

The Jefferson Building on a recent late afternoon. Photo: Shawn Miller.

“In construction, in accommodations, in suitability to intended uses, and in artistic luxury of decoration,” the Washington Post reported, “there is no building that will compare with it in this country and very few in any other country.”

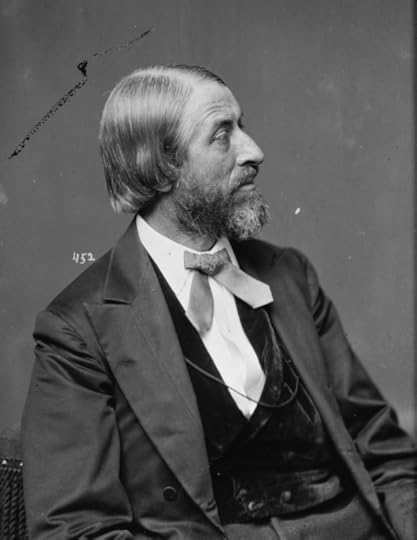

The accolades went on, no doubt deeply gratifying to one man in particular: Ainsworth Rand Spofford, the valiant Librarian of Congress from 1865 to 1897, whose vision and persistence brought the new facility into being.

From the moment the former Cincinnati bookseller and journalist joined the Library’s staff of six in 1861, he saw its potential to grow into an institution on a level with national libraries of Europe — even though, at the time, it sat within the U.S. Capitol and served as a reference library for Congress.

After President Abraham Lincoln appointed Spofford Librarian of Congress on Dec. 31, 1864, he quickly gained congressional approval for several expansions. When, following a tireless campaign by Spofford, Congress revised the Copyright Act in 1870, the Library’s future as a national institution took a leap forward.

The new law centralized copyright registration and deposit activities at the Library, dramatically increasing the number of copyrighted U.S. works set to flow in — books, maps, prints, music. Spofford needed more space.

In his 1872 annual report to Congress, he advocated for a new building. He envisioned a domed circular reading room like that of the British Museum, with books arranged in alcoves “rising tier above tier” around its circumference.

The Library would continue to support Congress, of course, but it also would serve the public and have ample room for collections and exhibits.

Ainsworth Rand Spofford. between 1870-1880. Photo: Brady-Handy. Prints and Photographs Division.

“In every country of where civilization has attained a high rank, there should be at least one great library, universal in its range,” Spofford wrote, referencing France’s Bibliothèque nationale and the British Museum.

The capital’s political climate favored Spofford’s expansive vision. “It was a time when America was feeling its oats,” Library historian John Y. Cole says. “The Civil War was over. Washington, D.C., was growing. Spofford took full advantage of the situation to promote his national library idea.”

Congress funded a design competition for a new building in 1873, and the Washington, D.C., firm of John L. Smithmeyer and Paul J. Pelz won the $1,500 first prize with an Italian Renaissance design that included a circular reading room.

Hopes were high that construction would soon follow. Alas, it was not to be.

Just a year later, Congress reopened the design competition when some members wanted an even grander structure. That move set off more than a decade of squabbling by committees and commissions — revisiting whether to construct a new building, arguing about its location, debating its style.

Ironically, after all that, Smithmeyer and Pelz won again with a more ornate 1885 version of their Italian Renaissance design. In 1886, Congress authorized construction of a new building across from the Capitol, yet the controversies continued.

Smithmeyer, appointed project architect, became embroiled in a dispute about cement for the foundation, leading to delays and congressional hearings, followed by his dismissal. The humiliation devastated him — he was later found with pistol in hand inside the Library, apparently planning to take his own life. (He didn’t.)

The troubled project got back on track when Congress appointed Brig. Gen. Thomas Lincoln Casey, chief of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and Bernard Richardson Green, a Harvard-educated civil engineer. The pair’s reputation preceded them: They had successfully collaborated to construct the Washington Monument and, more recently, the lavishly decorated State, War and Navy Building.

“Their momentum and nationalism carried the day,” Cole says.

Workers erect the southwest clerestory arch of the Library’s new building in 1892. Prints and Photographs Division.

Soon, Casey submitted a plan for an even bigger structure, and Congress approved around $6.5 million to construct it. Pelz designed the larger building, retaining the general features of his and Smithmeyer’s Italian Renaissance design, and he created sketches for the interior. But then he, too, lost his job after yet more infighting. Neither he nor Smithmeyer were ever fully compensated.

When it became clear Casey and Green would complete the building for less than what Congress appropriated, more money became available for interior embellishment.

“Casey and Green seized the opportunity and turned an already remarkable building into a cultural monument,” Cole says.

Casey’s son, Edward Pearce Casey, a trained architect, succeeded Pelz in 1892 and oversaw a program of majestic interior decoration that used tiles, mosaics, rosettes and columns to set off scores of sculptures and paintings. For guidance, Casey drew on the example of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

In fact, most of the more than 40 American painters and sculptors commissioned to contribute to the Library’s interior were involved in some way with the exposition, and many repeated idealistic themes from it. One of them, Edwin H. Blashfield, painted “The Evolution of Civilization” in the collar of the circular reading room Spofford had so desired. The mural is among the building’s most famous artworks.

It depicts 12 historical cultures and eras that contributed to Western civilization, starting with Egypt and ending with America. In the dome above, a painted figure lifts a veil of ignorance, signaling the nation’s intellectual progress.

Form did not, however, crowd out function. The new Library was one of the first public buildings in Washington, D.C., equipped with electricity. And Green himself designed its steel bookstacks, nine tiers high and serviced by the first efficient library pneumatic tube and conveyor system in America.

The tubes carried books back and forth between the reading room and each level of the stacks, while one tube each whisked books to and from the Librarian’s office and the Capitol.

“The book-carrying apparatus is a marvel of ingenuity,” one observer reported.

Even such a wonder, however, could not produce the first book requested on Nov. 1, 1897, about three minutes after the reading room opened. “Roger Williams’ Year Book” was not on the shelf, having just been published. Fortunately, the second book asked for, Martha Lamb’s “History of the City of New York,” was available.

In the 125 years since that rainy day, elements of the grand building have evolved. Copper replaced the dome’s gold plating in the 1930s. In 1980, the no-longer-new structure, by then one of three Library of Congress buildings, was renamed for Thomas Jefferson.

The Main Reading Room today. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Then, over a dozen years in the 1980s and 1990s, a major repair and renovation program restored the splendor of artwork and architecture obscured by decades of wear and tear, enabling people today to understand the awe of early witnesses.

“All good Americans should hope to visit the new Congressional Library before they die,” one advised in 1898. “It is one of the world’s wonders, well worth a trip across a continent to view.”

Based on the millions who visit the Library each year now, many Americans still share that view.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers