Library of Congress's Blog, page 31

July 18, 2022

A New Vision for an Inspiring Location

Artist’s rendering of the future oculus – a circular glass window that will allow visitors to look up to the dome of the Library’s Thomas Jefferson Building from a new orientation center.

The first time I stepped onto the floor of the Library of Congress’ Main Reading Room and looked up at the soaring, picturesque dome, I was overcome with a sense of wonder and gratitude for the opportunity to experience the inspiration that this iconic American space provides.

Because the Main Reading Room continues to serve as a working space for researchers, I had an opportunity to experience this majestic dome that many of the 2 million yearly visitors to the Library’s Thomas Jefferson Building cannot have … yet.

One of the many features in the Library’s comprehensive Visitor Experience Master Plan will offer every visitor is the opportunity to gaze up at that dome — a painting that represents Human Understanding in the act of lifting the veil of ignorance and looking forward to intellectual progress.

A rendering of the new orientation center. The oculus, in the center of the room, will allow visitors to see the ceiling of the Main Reading Room.

The Library will accomplish this, while also preserving the quiet character and intended function of the Main Reading Room, by installing an oculus – a circular glass window that will allow all visitors to see the dome from a new orientation center below the Main Reading Room. It’s where visitors will begin their Library journey.

For the researcher seeking insight, information and inspiration in the Main Reading Room, the experience will change very little. Librarians will be available to assist researchers. Staff will still deliver and distribute books and other research materials for use there. Access to digital resources will continue. The circular desk at the center of the room will remain. Only the cabinet enclosing a central staircase and book elevator at the center of the room, which has been modified and updated several times since 1897, will be removed to make way for the oculus. In most areas of the Main Reading Room, the oculus will be invisible, since it will be inside the perimeter of the circular desk.

Meanwhile, the new orientation center will occupy the space previously used as the control room. The historic functions of the control room, where books arrived for delivery to the Main Reading Room via the book elevator (which replaced the original dumbwaiter), have evolved many times since 1897 when the Library opened.

Today, the delivery of materials no longer requires a central control room. Repurposing that space will provide visitors with an educational and inspiring orientation to the Library’s vast resources, as well as a stunning view of the Main Reading Room’s dome.

A new learning center is part of the renovation project.

These are just a few of the exciting elements of the Library’s Visitor Experience Master Plan, which also includes a new Treasures Gallery and a learning center that will offer families, teens and school groups with opportunities to engage with Library collections through innovative interactive experiences.

All of these new experiences are possible thanks to generous investments from Congress and from generous private sector donations. David Rubenstein, the chairman of the Library’s James Madison Council and co-executive chairman of The Carlyle Group, has pledged $10 million to support the visitor experience project, and other private sector donors will also support it. Congress has expressed enthusiastic support and has appropriated $40 million to fund it.

The planning, design and construction of a project of this scope is significant. If current efforts remain on track, we look forward to welcoming our first visitors to experience some of the new elements included in the Visitor Engagement Master Plan in 2023 when the Treasures Gallery opens.

The Library seeks to democratize access. We want to share the art and architecture of one of Washington’s most grand and beautiful rooms with the many, not the few. This is a public treasure funded by the American people — and more people should experience the wonder of their national library.

The Library’s mission is to engage, inspire and inform Congress and the American people – researchers and visitors alike – with a universal and enduring source of knowledge and creativity. The Visitor Experience Master Plan represents a visionary pathway to engage more Americans than ever in their Library, the Library of Congress.

A new gallery of the Library’s treasures will allow more visitors to see more of the Library’s most important holdings.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

July 14, 2022

The 2022 National Book Festival Lineup Reveal!

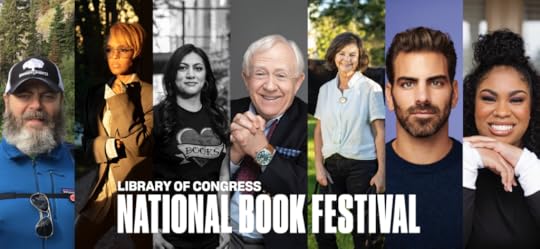

Featured authors, from left to right: Nick Offerman, Janelle Monáe, Sabaa Tahir, Leslie Jordan, Geraldine Brooks, Nyle DiMarco, Angie Thomas.

The 2022 Library of Congress National Book Festival returns to returns to live audiences this Labor Day weekend for the first time in three years, bringing celebrities and cult favorites back to Washington for the first time since the COVID-19 pandemic shut down live events across the nation’s capital.

The one-day, all-day festival — Saturday, Sept. 3, from 9 a.m. until 8 p.m. — will feature more than 120 authors, poets and writers under the theme of “Books Bring Us Together.” It’s not quite the same festival as fans have known in past years, as there will be new storytelling and audiobook events. Festival stages have been renamed and refocused, including the addition of a Life/Style stage to encompass changing pop culture trends.

Big names abound. Singer-songwriter Janelle Monáe discusses bringing the Afrofuturistic world of her albums to the written page for her book, “The Memory Librarian: And Other Stories of Dirty Computer.” Deaf activist Nyle DiMarco shares his story in “Deaf Utopia: A Memoir — and a Love Letter to a Way of Life.”Actor Nick Offerman, perhaps best known for his role as Ron Swanson on NBC’s “Parks and Recreation,” talks about his love of the great outdoors in “Where the Deer and the Antelope Play: The Pastoral Observations of One Ignorant American Who Loves to Walk Outside.” Comedian and internet personality Leslie Jordan is sure to entertain with a discussion of his book, “How Y’all Doing?: Misadventures and Mischief from a Life Well Lived.”

Young audiences will be enthralled by a conversation featuring the six authors behind “Blackout” —Dhonielle Clayton, Tiffany D. Jackson, Nic Stone, Angie Thomas, Ashley Woodfolk and Nicola Yoon. Author Donna Barba Higuera joins the Young Adult stage to discuss her award-winning dystopian novel “The Last Cuentista.”

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Geraldine Brooks shares her latest novel “Horse.” Clint Smith discusses his recent work “How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America.”

The festival will be held at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center in Washington, D.C. Doors will open at 8:30 a.m. The festival is free and open to everyone.

Can’t make it? No problem. Events on several of the stages will be livestreamed. Videos of all presentations will be made available on demand shortly after the festival.

The full lineup of featured authors follows, organized by stage.

Main Stage: Dhonielle Clayton, Tiffany D. Jackson, Nic Stone, Angie Thomas, Ashley Woodfolk and Nicola Yoon; Nyle DiMarco; Leslie Jordan; Janelle Monáe; Nick Offerman.

History & Biography: Tomiko Brown-Nagin; Jack E. Davis; Howard W. French; Kate Clifford Larson; Kelly Lytle Hernández; David Maraniss; Candice Millard; Clint Smith; Danyel Smith.

Life/Style: Geoffrey L. Cohen; Tracy Dennis-Tiwary; Todd Doughty; Hekima Hapa and Lesley Ware; Celeste Headlee; David M. Rubenstein; Ellen Vora.

Pop Lit: Mitch Albom; Louis Bayard; Jennifer Close; Susan Coll; Karen Joy Fowler; Grant Ginder; Xochitl Gonzalez; Katie Gutierrez; Dolen Perkins-Valdez; Amanda Eyre Ward.

Science Fiction & Fantasy: Chelsea Abdullah; Holly Black; B. L. Blanchard; Rob Hart; M. J. Kuhn; Victor Manibo; Tochi Onyebuchi; Leslye Penelope; Lucinda Roy; Nghi Vo.

Society & Culture: Rachel Aviv; Gal Beckerman; Daniel Bergner; Juli Berwald; Will Bunch; Morten Høi Jensen, Shawn McCreesh and Becca Rothfeld; Kathryn Judge; Brendan McConville; Robert Samuels; Linda Villarosa; Edith Widder; Elizabeth Williamson; Ed Yong.

Writers Studio: Nuar Alsadir; Geraldine Brooks; Kim Fu; Diana Goetsch; Rebecca Miller; Tomás Q. Morín; Sarah Ruhl; Morgan Talty; Jesmyn Ward; Lidia Yuknavitch.

KidLit: Kwame Alexander; Mac Barnett and Shawn Harris; Fred Bowen and James E. Ransome; David Bowles; Soman Chainani; Johnnie Christmas; Erin Entrada Kelly; Kat Fajardo; Lev Grossman; Gordon Korman; Juliet Menéndez; Andrea Davis Pinkney and Tybre Faw; Julian Randall; Tui T. Sutherland; Jennifer Ziegler.

Please Read Me A Story: Derrick Barnes and Vanessa Brantley-Newton; Mac Barnett; Ruth Behar; Ruby Bridges; Marc Brown; Xelena González; Bakari Sellers; Brittany J. Thurman.

Young Adult: Samira Ahmed; Victoria Aveyard; Donna Barba Higuera; Namina Forna; Chloe Gong; Tiffany D. Jackson; Ryan La Sala; Ebony LaDelle; Darcie Little Badger; Malinda Lo; E. Lockhart; Anna-Marie McLemore; Jason Reynolds; R. M. Romero; Sabaa Tahir; David Valdes.

All authors will participate in book signings following their events. Festivalgoers will be able to purchase books by the featured authors from Politics & Prose, the official bookseller of the 2022 National Book Festival.

In collaboration with the Library’s National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled, the festival will feature a panel of popular audiobook narrators sharing insights into their work. The festival will also feature for the first time performances by the literary nonprofit Literature to Life, a performance-based literacy program that presents professionally staged verbatim adaptations of American literary classics.

July 12, 2022

Ada Limón, the Nation’s New Poet Laureate

Ada Limón at the U.S. Capitol. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden today announced the appointment of Ada Limón as the nation’s 24th Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry for 2022-2023. Limón will take up her duties in the fall, opening the Library’s annual literary season on Sept. 29 with a reading of her work in the Coolidge Auditorium.

“Ada Limón is a poet who connects,” Hayden said. “Her accessible, engaging poems ground us in where we are and who we share our world with. They speak of intimate truths, of the beauty and heartbreak that is living, in ways that help us move forward.”

Limón joins a long line of distinguished poets who have served in the position, including Joy Harjo who served three terms in the position (2019-2022), Juan Felipe Herrera, Charles Wright, Natasha Trethewey, Philip Levine, W.S. Merwin, Kay Ryan, Charles Simic, Donald Hall, Ted Kooser, Louise Glück, Billy Collins, Stanley Kunitz, Robert Pinsky, Robert Hass and Rita Dove.

“What an incredible honor,” Limón said. “Again and again, I have been witness to poetry’s immense power to reconnect us to the world, to allow us to heal, to love, to grieve, to remind us of the full spectrum of human emotion.”

Limón was born in Sonoma, California, in 1976 and is of Mexican ancestry.

She is the author of six poetry collections, including “The Carrying” (Milkweed Editions, 2018), which won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry; “Bright Dead Things” (2015), a finalist for the National Book Award and the National Books Critics Circle Award; “Sharks in the Rivers” (2010); “Lucky Wreck” (Autumn House, 2006); and “This Big Fake World” (Pearl Editions, 2006). She earned a Master of Fine Arts degree from New York University and is the recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the New York Foundation for the Arts, the Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center and the Kentucky Foundation for Women.

Her newest poetry collection, “The Hurting Kind,” was recently published as part of a three-book deal with Milkweed Editions that includes the publication of “Beast: An Anthology of Animal Poems,” featuring work by major poets over the last century, followed by a volume of new and selected poems.

Limón is currently the host of “The Slowdown,” the American Public Media podcast series which was launched as part of Tracy K. Smith’s poet laureateship in 2019. Limón serves on the faculty of Queens University of Charlotte Low Residency MFA program. She lives in Lexington, Kentucky.

The Library’s Poetry and Literature Center is the home of the Poet Laureate, a position that has existed since 1937, when Archer M. Huntington endowed the Chair of Poetry at the Library. Since then, many of the nation’s most eminent poets have served in the position. A 1985 congressional law states it is “equivalent to that of Poet Laureate of the United States.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

July 7, 2022

The Neil Simon Collection: Now Playing at the Library of Congress

Neil Simon on the cover of Time Magazine in 1986. Music Division. Photo: Shawn Milller.

Flipping through one of Neil Simon’s scrapbooks in the Library’s recently arrived collection of his work, one comes across an article about his first Broadway play, “Come Blow Your Horn.”

The 1961 play was a huge success, running for more than 600 performances. But one New York newspaper, echoing Simon’s own worries, wondered if he might be a one-hit wonder. Simon was a working professional in his mid-30s, after all, busy with a day job of writing quips for comedians and hosts on radio and television. It had taken him more than three years and a dozen top-to-bottom rewrites to put together “Horn.” Plus, he said, playwriting was “totally different” from his usual work.

“Now I’m supposed to come up with another hit to prove my first smash wasn’t some sort of fluke,” Simon told Newsday, the Long Island daily.

The resulting headline: “His 1st Play Drew Raves, Problem Is How to Repeat.”

If this was a Simon play, this is the part where the lead character, after reading that aloud, would turn to the audience, deadpan, and with merely a knowing look, let the laughs rain down.

Simon, of course, went on to become the most commercially successful playwright in American history and one of the most honored. “Barefoot in the Park,” “The Odd Couple,” “The Sunshine Boys,” “Biloxi Blues,” “Plaza Suite,” “Lost in Yonkers.” By the time he died at age 91 in 2018, he his career included 28 Broadway plays, five musicals, 11 original screenplays and 14 film adaptations of his own work.

One of Simon’s artworks. Music Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Focusing on comedy and usually autobiographically inspired, he rarely took on the heavy socials issues of the era, yet he and his work won the Pulitzer Prize, four Writers Guild of America Awards, four Tony Awards, the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor, a Kennedy Center Honor and the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award, among others. His screenwriting earned four Academy Award nominations.

His collection was donated to the Library earlier this year, an acquisition marked with a ceremony featuring his widow, Elaine Joyce, and actor Matthew Broderick, who starred in many of his works. Mark Horowitz, a senior specialist in the Music Division, says Simon’s vast collection is “everything we hoped for and more.”

“It preserves and documents the history, work and creative process of one of our most significant American writers,” Horowitz says.

It’s a dazzling addition to the Library’s collection of theater work, including at least some script material for more than 180 plays, films and musicals. In addition to numerous drafts of all of his famous works, there are many completed works that went unproduced and are unknown to the public. Other titles are fragments, with only a scene or two.

There is also a vast trove of letters, photographs, programs, newspaper clippings, and most unexpectedly, several notebooks filled with his drawings, cartoons and artwork. There’s even a pair of his glasses and a collection of signed baseballs. (The latter includes Hall of Famers such as Tommy Lasorda, Eddie Murray and Tony Gwynn.)

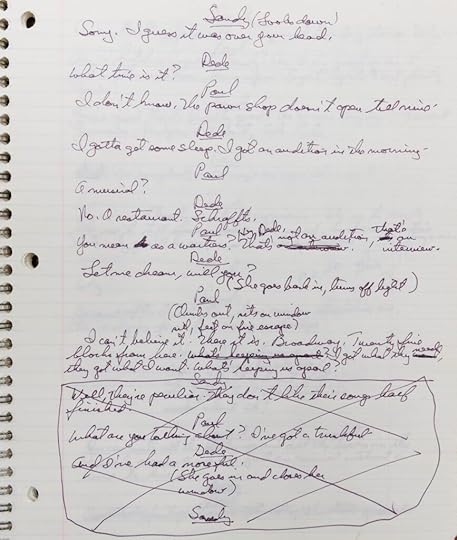

Simon’s notebook draft of “The Odd Couple” for a 2005 revival starring Nathan Lane and Matthew Broderick. Music Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

His first drafts are neatly written out in longhand — in cursive you can read! — in dime-store notebooks. Most typescript drafts are dated, numbered and often signed, such as “7th draft, 9/99.”

Writing in pen, in notebooks he often mimicked a play’s typeset layout— neatly rendering the play’s title, his name and the date in the style of a title page. He did the same in his handwritten script pages, centering the dialogue and set directions with the character’s name above their lines.

Sometimes, even after typing up a second or third draft, he would go back to handwriting for later drafts. This is a fascinating thing to note — despite his mammoth success, he was still copying and rewriting line after line in pen. He changed or deleted words, sentences and sections. He marked those changes by hand in the margins, or in additional notebooks, or sometimes he inserted different colored pages to mark new passages. Those scenes were listed in the front of the manuscript. When, deep in these notebooks, he wanted to indicate a change to be typed up later, he would write in act and scene numbers along with pagination of where the inserts were to go.

One of Simon’s draft pages Photo: Shawn Miller.

Despite Simon’s record-breaking success, it didn’t mean that everything he did made it to the market.

One unproduced screenplay in the late 1980s had at least three different titles. It started off as “Just Looking,” was then titled “Jake and Kate” and, finally between 1987 and 1989, was called “A Couple of Swells.” One early draft is written in longhand in a green notebook. Later drafts are typed, signed and dated, along with notes indicating the earlier titles.

Still, the show remained unproduced.

By 1989, he was back to writing in longhand on a third draft, this time in a notebook with a bright yellow cover. He worked on it meticulously, changing small things from the first page to the last.

And still, even at the peak of his career, it never made it to the screen. (He did use “A Couple of Swells” as a chapter title in his memoir, fittingly titled “Rewrites,” in 1996.)

You want the mark of greatness? It’s that sort of far-from-the-glamour dedication, right down to making word edits on a script that, even after three years of off-and-on work, showed no signs of being brought to life. Even then, he kept up with each draft, each set of changes, neatly labeling and signing the work.

The most successful playwright in American history didn’t get that way by chance – he just kept sweating the details, getting the laughs just right.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

July 5, 2022

Average Jones: Solving Crimes via the Classifieds

“Average Jones” by Samuel Hopkins Adams. Cover art: George Reiter Brill, adapted from an 1896 magazine cover.

This is a guest post by Zach Klitzman, the editorial assistant in the Library’s Publishing Office .

Does a B-flat trombone player have anything to do with an assassination attempt? Why does a man only speak in Latin? Can the word “mercy” have a sinister meaning? And who stole a necklace of “blue fire” from a hotel room?

These puzzles and more are central to the latest Library of Congress Crime Classic, “Average Jones” by Samuel Hopkins Adams, a popular and prolific journalist and novelist in the early 20th century whose works were often turned into popular films.

First published in 1911, “Average Jones” is a collection of 10 short stories featuring Adrian Van Reypen Egerton Jones, known to his friends as “Average.” Jones is anything but average, though, as his brilliant mind allows him to become a successful “Ad-Visor,” an investigator of classified ads on behalf of clients to root out swindlers.

The stories have newspaper advertising at their heart, but they also have all the elements that mystery readers enjoy. Identifying possible crimes in ads, while placing his own ads to stop them, Jones uncovers plots to steal inheritances, defraud the public into viewing fake exhibits, and assassinate both a New York City mayoral candidate and New York state’s governor. While many stories take place in and around the Big Apple, adventures also include a foray into Mexico to rescue a possibly kidnapped wayward son; a sojourn to Baltimore to meet the Latin-speaking man; and an investigation into puzzling letters mailed from Connecticut. The final story serves as a romantic coda, when Jones falls in love with a potential victim of a crime.

Adams was born and educated in western New York, became an expert on the state’s history, and these stories no doubt drew on his career as a muckraking journalist, especially his investigations into dishonest advertising and patent medicine. Collier’s magazine published his 11-part exposé, “The Great American Fraud,” in 1905, and its successful denunciation of the patent medicine industry played a role in the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906.

Samuel Hopkins Adams, front left, carrying a pen nib, along with other muckraking journalists in “The Crusaders.” Illustration: Carl Hassman. Prints & Photographs Division.

He was very well known for this work; in an illustration for Puck magazine in 1906, Carl Hassman depicted Adams front and center-left wielding a pen nib as a sword. His fellow muckrakers also appear, including Ida Tarbell, lifting a banner for McClure’s Magazine on horseback, and Lincoln Steffens, also on horseback, on the right.

Adams went on to write more than 50 books, including mysteries, presidential biographies, nonfiction and works for children. During the 1920s, writing under the pseudonym of Warner Fabian, he published half a dozen novels featuring Jazz Age characters and risqué plots. Several of these and other works were adapted into successful films.

A poster for “It Happened One Night,” based on an Adams’ short story.

“The Wild Party” starred Clara Bow and “Sailors’ Wives” starred Mary Astor, both huge names in the 1920s. His short story “Night Bus” was adapted in 1934 to “It Happened One Night,” now regarded as one of Hollywood’s classic films. Starring Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert, directed by Frank Capra, it’s one of only three films to win all five major Academy Awards. It was inducted into the Library’s National Film Registry in 1993.

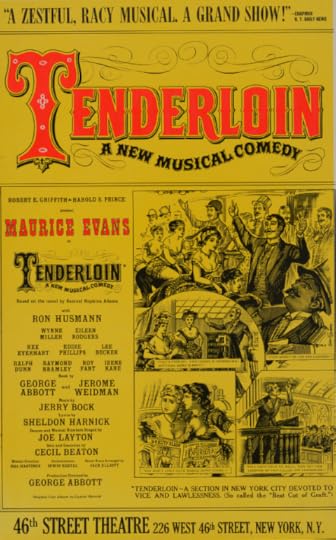

Other stories adapted into films included “The Gorgeous Hussy” (starring Joan Crawford) in 1936 and “The Harvey Girls” (starring Judy Garland and Angela Lansbury) in 1945. His final novel, “The Tenderloin,” was made into a Broadway musical in 1961, three years after Adams died at the age of 87.

Poster from 1961 for “Tenderloin,” a musical based on Adams’ novel. Prints & Photographs Division.

While the Average Jones stories were just a small part of Adams’ output, they displayed their creator’s socially conscious attitudes and dedication to muckraking, along with intriguing mysteries and a sharp sense of humor.

Launched in 2020, the Crime Classics series features some of the finest American crime writing from the 1860s to the 1960s. Drawn from the Library’s collections, each volume includes the original text, an introduction, author biography, notes, recommendations for further reading and suggested discussion questions from mystery expert Leslie S. Klinger. This special edition also features illustrations from the original edition of the book, drawn by M. Leone Bracker.

Crime Classics are published by Poisoned Pen Press, an imprint of Sourcebooks, in association with the Library of Congress. “Average Jones,” published on June 7, is available in softcover ($14.99) from booksellers worldwide, including the Library of Congress shop

June 30, 2022

Mississippi Author Jesmyn Ward: Winner of the 2022 Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction

Jesmyn Ward. Photo: Beowulf Sheehan.

This is a guest post by Leah Knobel, a public affairs specialist in the Library’s Office of Communications.

Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden announced today that the 2022 Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction will be awarded to Jesmyn Ward, whose lyrical works set in her native Mississippi feature the lives of Black people finding a way to endure and prevail over a world of harsh racism and violence. At 45, Ward is the youngest person to receive the Library’s fiction award for her lifetime of work.

“Jesmyn Ward’s literary vision continues to become more expansive and piercing, addressing urgent questions about racism and social injustice being voiced by Americans,” said Hayden. “Jesmyn’s writing is precise yet magical, and I am pleased to recognize her contributions to literature with this prize.”

One of the Library’s most prestigious awards, the annual Prize for American Fiction honors an American literary writer whose body of work is distinguished not only for its mastery of the art but also for its originality of thought and imagination. The award seeks to commend strong, unique, enduring voices that — throughout consistently accomplished careers — have told us something essential about the American experience.

“I am deeply honored to receive this award, not only because it aligns my work with legendary company, but because it also recognizes the difficulty and rigour of meeting America on the page, of appraising her as a lover would: clear-eyed, open-hearted, keen to empathize and connect,” Ward said. “This is our calling, and I am grateful for it.”

Hayden selected Ward as this year’s winner based on nominations from more than 60 distinguished literary figures, including former winners of the prize, acclaimed authors and literary critics from around the world. The virtual prize ceremony will take place at the Library’s 2022 National Book Festival on Sept. 3.

The fiction prize was inaugurated in 2008, recognizing Herman Wouk. Last year’s winner was Joy Williams. Other winners have included Toni Morrison, Philip Roth, Isabel Allende and E.L. Doctorow.

Ward is the acclaimed author of the novels “Where the Line Bleeds” and then two books that each won the National Book Award: “Salvage the Bones” in 2011 and “Sing, Unburied, Sing” in 2017. Her nonfiction work includes the memoir “Men We Reaped,” a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, and the 2020 work “Navigate Your Stars.” Ward is also the editor of the anthology “The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks About Race.”

Ward is one of only six writers to receive the National Book Award more than once and the only woman and Black American to do so. Ward was the recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship in 2017 and was the John and Renée Grisham Writer in Residence at the University of Mississippi for the 2010-2011 academic year. In 2018, she was named to Time Magazine’s list of 100 most influential people in the world.

Ward lives in Mississippi and is a professor of creative writing at Tulane University.

The National Book Festival will take place Sept. 3 from 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center in Washington. This will be the first time the festival has been in person since 2019. A selection of programs will be livestreamed, and recordings of all presentations can be viewed online following the festival.

June 29, 2022

Toy Theaters: 19th Century Home Entertainment

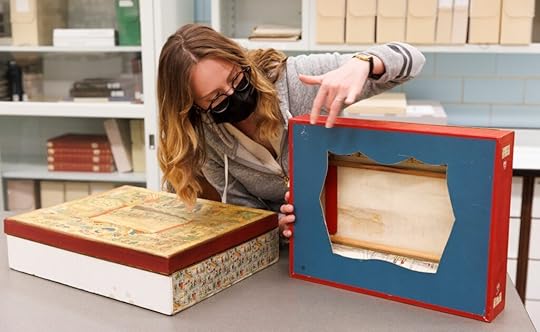

Basia Nosek displays a 19th century shadow box animation toy. Conservation Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Dashing heroes, evil bandits, high drama and adventure. Toy theaters, beloved playthings of the 19th century, offered all these. Charles Dickens staged productions with them in his living room. Robert Louis Stevenson wrote an ode to them. And a 14-year-old Winston Churchill was said to vault over the counter of a local stationer’s to grab the latest title.

Long before Netflix or video games, these tiny paper theaters served as home entertainment, outlets for imagination crafted for young people but popular with adults, too.

The Library’s Rare Book and Special Collections Division has dozens of the miniature theaters, many in colorful boxes containing magical characters and intricate scenes from the past. Over the past few years, Library paper conservators have been painstakingly mending damage caused by historical use, making sure researchers can draw insights from the theaters for years to come.

For “a penny plain and twopence coloured” — the title of Stevenson’s tribute — the stationer in his city sold “pages of gesticulating villains, epileptic combats, bosky forests, palaces and war-ships, frowning fortresses and prison vaults — it was a giddy joy,” he recalled, and the shop itself was a lodestone rock for “all that bore the name of boy.”

At first, English publishers sold sheets of principal characters from popular plays, imprinting the name of the theater staging a play and often the star actors. Enthusiasts — mainly boys and young men — bought them as souvenirs.

By 1812, sheets of scenes from plays were being sold with characters and, eventually, boxed kits appeared containing all the essentials of the stage: backdrops, curtains, props, orchestras and, of course, tiny actors, all to cut out and (if one spent just a penny) color. Some kits came with special script booklets or stage directions.

Nearly 300 toy productions, also known as juvenile dramas, were published in England between 1811 and 1860. Fans could choose military exploits (“The Battle of Waterloo,” “Conquest of Mexico,” “Invasion of Russia”), dramas and pirate stories (“Black Beard,” “Brigand and the Maid”) and even Shakespeare (“Macbeth,” “The Merry Wives of Windsor,” “Julius Caesar”).

Basia Nosek demonstrates the setup of a 19th century French shadow box. Conservation Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Such was the popularity of toy theaters that the first play written specifically for the medium, “Alone in the Pirate’s Lair,” published in 1866, made its way to the actual stage, followed by other original toy theater plays, according to theater historian Nicole Sheriko.

“They’ve turned out to be really compelling examples of what occupied a child in a certain period,” Mark Dimunation, RBSCD chief, said of a collecting effort focused not just on toy theaters, but also on other printed objects children played with, such as games, paper dolls and boxes with moving scenes.

The division initiated a “very self-conscious push” to collect these objects to complement its substantial holdings of children’s literature, Dimunation said. “They help us understand what is going on in some of the literature.”

Their research value also lies in the vivid hues imprinted on many, enabled by the rise of chromolithography in the 19th century. “They’re part of the history of printing, too,” Dimunation said. “The world suddenly becomes colorful.”

In England, the raucous stage of early 19th century London inspired the art form. But toy theaters flourished elsewhere as well — America, Germany, France — where they evolved and took different forms, a fact reflected in the collections.

Multiple theaters in the Library’s collection are panoramas — paper scenes wrapped around rods. When turned, cranks on either side of the theater advance scenes. Sometimes, the scenes progress through a play; in other cases, they are unassociated with one another.

These theaters, especially, have wear and tear, as paper ripped as a panorama was unwound, or cranks went missing or broke over time. The Library’s conservation lab has treated both issues. Basia Nosek, a recent intern in the lab, crafted an entirely new wooden crank to restore one theater.

“Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea.” Conservation Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Betsy Haude of the Conservation Division finished work in the spring on “Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea,” a beautifully illustrated panorama in deep blues and greens based on Jules Verne’s “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.”

It arrived with tears that had been repaired by an earlier owner with pressure-sensitive tape, “which is terrible for paper,” Haude said. So, she carefully removed the tape and mended the tears with archival-quality materials.

Sometimes, however, when a historical mend is determined not to be causing damage, conservators leave it in place, not wanting to remove something that might tell a bigger story about the object and its use, Haude said.

She is the paper liaison to RBSCD. The division’s retired children’s literature specialist, Sybille Jagusch, reached out to her to assess which theaters needed treatment. Haude and colleague Gwenanne Edwards identified an initial batch most in need of repair.

Edwards completed work recently on a shadow puppet theater, a variety that includes cutouts that were placed behind the theater’s paper curtain. A light illuminated them from behind, and viewers could see silhouettes of the cutouts from the front. A single theater could have up to 100 puppets, some with moveable parts.

“The little players … sometimes had an unfortunate habit of creasing up or becoming unglued,” biographer Peter Ackroyd wrote of Dickens’ theaters.

“There’s a lot of structural work that we have to do with the puppets if it’s that kind of theater,” Edwards said.

Betsy Haude shows the setup of a 19th century shadow box toy. Conservation Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

As a final step before returning repaired theaters to RBSCD, conservators construct archival-quality housing to ensure their longevity.

The most popular English toy theater play, “The Miller and His Men,” debuted in London’s Covent Garden in 1813. The story climaxes with fire and an explosion, an exciting spectacle that, in toy form, caused some home setups to perish.

The play captivated Dickens and, many years later, Churchill. It’s possible Churchill’s immersion in the story even inspired some of his trademark rhetoric as the United Kingdom’s World War II prime minister, theater historian George Speaight speculates.

In the final scene of “Miller,” a cornered villain exclaims, “Surrender? Never! I have sworn never to descend from this spot alive!”

Can there be a remembered echo in Churchill’s dramatic words to the House of Commons in 1940? Speaight asks — “We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds … we shall never surrender!”

Likewise with Stevenson: “What is ‘Treasure Island’ but one of the piratic dramas retold?” Speaight postulates.

Gradually, toy theaters faded in popularity as the 20th century brought new diversions. But their magic is such that even a researcher today, visiting the Library’s Rare Book Reading Room, is sure to find delight in the carefully preserved record left behind.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

June 24, 2022

Len Downie: The Washington Post Papers

Leonard Downie Jr. speaking at the Library’s “50 Years of Watergate” event on June 17. Photo: Screenshot from video of the panel discussion.

This is a guest post by Ryan Reft in the Manuscript Division. It has been slightly adapted from its original publication last week on the “Unfolding History” blog.

Steven Spielberg’s 2017 film “The Post” depicts The Washington Post’s efforts to publish its account of the Pentagon Papers, but if you’ve only seen the movie’s first 40 minutes you might think it’s about New York Times journalist Neil Sheehan. “Sheehan!” Post executive editor Ben Bradlee (Tom Hanks) gripes as he wonders about the reporter’s activities. Sheehan came to prominence covering the Vietnam War and in 1971 he broke the Pentagon Papers story, the epic, constitutionally challenging scoop that drives the film’s plot.

Former Post executive editor Leonard Downie Jr., at the time a reporter for the newspaper, had his doubts about the movie’s depiction of Bradlee’s Sheehan obsession. “I have a hard time believing Ben paid attention to what Sheehan was doing,” he wrote to the movie’s producers.

Having been brought on as a consultant to the film, Downie praised “The Post” as one of “the most realistic and meaningful screen depictions of the importance of newspaper journalism” and placed it among classics such as “All the President’s Men” and “Spotlight.” In his notes, which can be found in the Manuscript Division’s recently acquired Leonard Downie Jr. Papers, he offered numerous other insights.

Some were mundane but important for authenticity, such as when he pointed out that the Post had no garage at the time, so the newspaper’s publisher Katharine Graham had to be dropped off in front of the old building on L Street. Others proved more revealing. Downie noted the movie’s accuracy in capturing Graham’s role as tipster for Bradlee and himself.

Katharine Graham at her desk in 1976. Photo: Marion S. Trikosko. Prints and Photographs Division.

Downie’s consultancy provides a useful entry point into a collection that spans decades at one of the nation’s most august newspapers. His papers, which recently opened in the Manuscript Division, provide not only an overview of Downie’s career but also as a perch on the Post’s inner workings.

Starting as an intern during the 1960s, Downie worked his way up the Post food chain, including stops as deputy (1972-1974) and assistant managing editor (1974-1979) for the Metro desk, foreign correspondent in London (1979-1982), national editor (1982-1984), managing editor (1984-1991) and then as executive editor (1991-2008).

The Post won its share of Pulitzers during Downie’s leadership, taking six of the fourteen prizes in journalism in 2007, only the fourth time a newspaper emerged with more than three Pulitzer Prizes in a single year. Though he retired from the newspaper in 2008, Downie continues to work in the field, including the Committee to Protect Journalists and at Arizona State University to name just two.

Downie’s work consulting on “The Post” serves as just one dot in his collection’s pointillist rendition of journalistic history, which is full of strong characters and personalities. Downie succeeded legendary editor Ben Bradlee. Together they stewarded the Post’s rise to national prominence. The Downie papers do not lack for vantage points from which to witness Bradlee’s combative dynamism.

In an email to Robert Kaiser, a fellow Post editor, Downie offered his perspective on Bradlee’s tenure, correcting a popular memory that envisioned him roaming the newsroom and regularly engaging reporters.

In reality, he suggests, the famed editor sought out “those journalists he knew best and liked to talk to.” Still, his “aura” pervaded the newsroom, and he stood by his reporters’ stories. Downie recalled his 1960s series on the scandals in the savings and loan industry which cost the newspaper hundreds of thousands of dollars in advertising when local S&L institutions boycotted the paper over his reporting. Bradlee, aware of the financial costs of Downie’s reporting, simply told him to “get it right kid.”

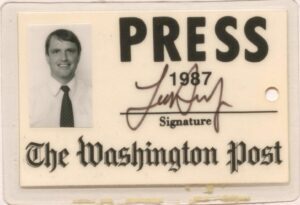

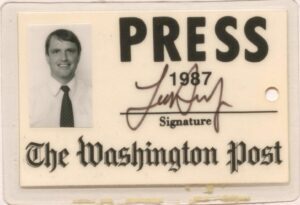

Downie’s press credential. Manuscript Division.

While Bradlee vigorously supported the newspaper’s journalists, the inspiration one drew from his praise could also curdle. “His turning his back on you when you failed was devastating,” Downie recalled. As for his “personal touch,” it could sometimes be described as “favortism” (sic), and often left Bradlee blindsided when women and non-white reporters complained about inequality at the paper.

For researchers interested in the newspaper’s internal dynamics, the collection offers a unique window. The Pugwash Files, named after the newspaper’s annual retreat, includes a number of publisher Don Graham’s annual state of the newspaper addresses. At the retreat, editors and journalists bounced around ideas for the newspaper’s direction in the coming years and discussed pressing internal issues.

Following the 1994 Pugwash, deputy managing editor and future ombudsman Michael Getler wrestled with the direction of the paper’s competitors. Should the Post run fewer series and investigative projects like the New York Times and Los Angeles Times, the two papers he identified as focusing on simply being the “best daily paper?” “The Washington Post, however, wants to do it all and does a very good job at trying,” observed Getler.

At its 1993 retreat, attendees made clear that the newspaper needed to do better in regard to diversity. Characterizing the 1993 Pugwash meeting with its associate managing editors as “extraordinarily productive,” Downie recounted a survey of the newspaper’s journalists that credited the newspaper with diversifying the newsroom generally, but asserted that greater strides needed to be made: “You said the least progress has been made in the promotion of women and minorities into high level editing jobs.”

As result, the Post organized a task force chaired by Getler to address the issue. According to a 2005 Downie memo, the seed planted at that 1993 Pugwash had begun to sprout. The numbers of women and persons of color working in the newsroom had reached all-time highs for the Post that year, with minorities at 23 percent. “This newsroom is stronger than ever,” he wrote.

Researchers will also find correspondence and other materials featuring coverage of events such as Watergate, the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars, the Bill Clinton and George W. Bush administrations, the Valerie Plame affair, 9/11, the Unabomber and much more.

“Journalism, the old adage goes, should comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable,” Downie wrote in his 2020 memoir, “All About the Story.” “This is just what the Post did during my leadership of the newsroom.” A lifetime at one of the nation’s most influential newspapers is laid out in the Leonard Downie Jr. Papers.

Len Downie

Leonard Downie Jr. speaking at the Library’s “50 Years of Watergate” event on June 17. Photo: Screenshot from video of the panel discussion.

This is a guest post by Ryan Reft in the Manuscript Division. It has been slightly adapted from its original publication last week on the “Unfolding History” blog.

Steven Spielberg’s 2017 film “The Post” depicts The Washington Post’s efforts to publish its account of the Pentagon Papers, but if you’ve only seen the movie’s first 40 minutes you might think it’s about New York Times journalist Neil Sheehan. “Sheehan!” Post executive editor Ben Bradlee (Tom Hanks) gripes as he wonders about the reporter’s activities. Sheehan came to prominence covering the Vietnam War and in 1971 he broke the Pentagon Papers story, the epic, constitutionally challenging scoop that drives the film’s plot.

Former Post executive editor Leonard Downie Jr., at the time a reporter for the newspaper, had his doubts about the movie’s depiction of Bradlee’s Sheehan obsession. “I have a hard time believing Ben paid attention to what Sheehan was doing,” he wrote to the movie’s producers.

Having been brought on as a consultant to the film, Downie praised “The Post” as one of “the most realistic and meaningful screen depictions of the importance of newspaper journalism” and placed it among classics such as “All the President’s Men” and “Spotlight.” In his notes, which can be found in the Manuscript Division’s recently acquired Leonard Downie Jr. Papers, he offered numerous other insights.

Some were mundane but important for authenticity, such as when he pointed out that the Post had no garage at the time, so the newspaper’s publisher Katharine Graham had to be dropped off in front of the old building on L Street. Others proved more revealing. Downie noted the movie’s accuracy in capturing Graham’s role as tipster for Bradlee and himself.

Katharine Graham at her desk in 1976. Photo: Marion S. Trikosko. Prints and Photographs Division.

Downie’s consultancy provides a useful entry point into a collection that spans decades at one of the nation’s most august newspapers. His papers, which recently opened in the Manuscript Division, provide not only an overview of Downie’s career but also as a perch on the Post’s inner workings.

Starting as an intern during the 1960s, Downie worked his way up the Post food chain, including stops as deputy (1972-1974) and assistant managing editor (1974-1979) for the Metro desk, foreign correspondent in London (1979-1982), national editor (1982-1984), managing editor (1984-1991) and then as executive editor (1991-2008).

The Post won its share of Pulitzers during Downie’s leadership, taking six of the fourteen prizes in journalism in 2007, only the fourth time a newspaper emerged with more than three Pulitzer Prizes in a single year. Though he retired from the newspaper in 2008, Downie continues to work in the field, including the Committee to Protect Journalists and at Arizona State University to name just two.

Downie’s work consulting on “The Post” serves as just one dot in his collection’s pointillist rendition of journalistic history, which is full of strong characters and personalities. Downie succeeded legendary editor Ben Bradlee. Together they stewarded the Post’s rise to national prominence. The Downie papers do not lack for vantage points from which to witness Bradlee’s combative dynamism.

In an email to Robert Kaiser, a fellow Post editor, Downie offered his perspective on Bradlee’s tenure, correcting a popular memory that envisioned him roaming the newsroom and regularly engaging reporters.

In reality, he suggests, the famed editor sought out “those journalists he knew best and liked to talk to.” Still, his “aura” pervaded the newsroom, and he stood by his reporters’ stories. Downie recalled his 1960s series on the scandals in the savings and loan industry which cost the newspaper hundreds of thousands of dollars in advertising when local S&L institutions boycotted the paper over his reporting. Bradlee, aware of the financial costs of Downie’s reporting, simply told him to “get it right kid.”

Downie’s press credential. Manuscript Division.

While Bradlee vigorously supported the newspaper’s journalists, the inspiration one drew from his praise could also curdle. “His turning his back on you when you failed was devastating,” Downie recalled. As for his “personal touch,” it could sometimes be described as “favortism” (sic), and often left Bradlee blindsided when women and non-white reporters complained about inequality at the paper.

For researchers interested in the newspaper’s internal dynamics, the collection offers a unique window. The Pugwash Files, named after the newspaper’s annual retreat, includes a number of publisher Don Graham’s annual state of the newspaper addresses. At the retreat, editors and journalists bounced around ideas for the newspaper’s direction in the coming years and discussed pressing internal issues.

Following the 1994 Pugwash, deputy managing editor and future ombudsman Michael Getler wrestled with the direction of the paper’s competitors. Should the Post run fewer series and investigative projects like the New York Times and Los Angeles Times, the two papers he identified as focusing on simply being the “best daily paper?” “The Washington Post, however, wants to do it all and does a very good job at trying,” observed Getler.

At its 1993 retreat, attendees made clear that the newspaper needed to do better in regard to diversity. Characterizing the 1993 Pugwash meeting with its associate managing editors as “extraordinarily productive,” Downie recounted a survey of the newspaper’s journalists that credited the newspaper with diversifying the newsroom generally, but asserted that greater strides needed to be made: “You said the least progress has been made in the promotion of women and minorities into high level editing jobs.”

As result, the Post organized a task force chaired by Getler to address the issue. According to a 2005 Downie memo, the seed planted at that 1993 Pugwash had begun to sprout. The numbers of women and persons of color working in the newsroom had reached all-time highs for the Post that year, with minorities at 23 percent. “This newsroom is stronger than ever,” he wrote.

Researchers will also find correspondence and other materials featuring coverage of events such as Watergate, the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars, the Bill Clinton and George W. Bush administrations, the Valerie Plame affair, 9/11, the Unabomber and much more.

“Journalism, the old adage goes, should comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable,” Downie wrote in his 2020 memoir, “All About the Story.” “This is just what the Post did during my leadership of the newsroom.” A lifetime at one of the nation’s most influential newspapers is laid out in the Leonard Downie Jr. Papers.

June 22, 2022

George Chauncey, Kluge Winner

“Professor Chauncey’s trailblazing career gave us all better insight into, and understanding of, the LGBTQ+ community and history,” Hayden said. “His work that helped transform our nation’s attitudes and laws epitomizes the Kluge Center’s mission to support research at the intersection of the humanities and public policy.”

Chauncey is the first scholar in LGBTQ+ studies to receive the prize. He is known for his pioneering 1994 history “Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940,” his 2004 book “Why Marriage? The History Shaping Today’s Debate over Gay Equality,” and his work as an expert in more than 30 court cases related to LGBTQ+ rights. These include such landmark U.S. Supreme Court cases as Romer v. Evans (1996), Lawrence v. Texas (2003), and the marriage equality cases United States v. Windsor (2013) and Obergefell v. Hodges (2015).

“I am deeply honored to receive the Kluge Prize,” Chauncey said, “and grateful that the Library of Congress has recognized the importance and vibrancy of the field of LGBTQ history.”

Drew Gilpin Faust, former Kluge Prize winner and Harvard historian, was delighted by the news.

“(He) has entirely revised our understanding of LGBTQ history in the United States and in so doing has established it as one of the most vibrant fields of current historical inquiry,” she said. “Through his testimony in numerous court cases, he has brought the meaning of his work into the public sphere and has contributed in powerful ways to the establishment of marriage equality.”

“Gay New York.” Image courtesy of Basic Books.

“Gay New York” was released in 1994 during the 25th anniversary of the LGBTQ+ rights protests at the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, focusing on the gay community in New York City before World War II. Chauncey’s research utilized newspapers, police records, oral histories, diaries and other primary sources to show that there was a much more vibrant and visible gay world than is generally understood today, less than a century later.

It argued that there was a permeable boundary between straight and gay behavior, especially among working-class men. “Gay New York” won numerous prizes for its scholarship including the Frederick Jackson Turner Prize from the Organization of American Historians, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for History and the Lambda Literary Award for Gay Men’s Studies.

“Why Marriage?” drew on Chauncey’s extensive research prepared for court cases in which he provided expert testimony. It traces the history of both gay and anti-gay activism and discusses the origins of the modern struggle for gay marriage.

Legal historian Sarah Barringer Gordon said Chauncey’s “work gave rise to an entire new field…and has expanded into arenas that affect daily life, such as marriage equality.”

George Chauncey.

Chauncey grew up as the son of a minister in the Deep South, whose work on civil rights issues was often deeply unpopular with his white evangelical congregations. “He was sometimes asked to leave” churches, Chauncey recalled, causing the family to move often.

Chauncey received a Bachelor of Arts and a doctorate from Yale University. He was the Samuel Knight Professor of History & American Studies at Yale from 2006 to 2017, and held posts as chair of the History Department, chair of the Committee for LGBT Studies, and director of graduate studies and undergraduate studies for the American Studies program. He was awarded Yale’s teaching prize for his lecture course on U.S. Lesbian and Gay History, which more than 300 students took the final time he taught it. Chauncey taught at the University of Chicago from 1991 through 2006 before coming back to New York to teach at Columbia.

He has been an elected member of the New York Academy of History since 2007 and a member of the Society of American Historians since 2005. He is married to Ronald Gregg, a film historian and director of the master’s program in Film and Media Studies at Columbia University.

The Library will collaborate with Chauncey to create programming to bring his expertise on LGBTQ+ history to the public and policymakers.

The Kluge Prize recognizes individuals whose outstanding scholarship in the humanities and social sciences has shaped public affairs and civil society. Awarded to a scholar every two years, the international prize highlights the value of researchers who communicate beyond the scholarly community and have had a major impact on social and political issues. The prize comes with a $500,000 award. Additional funds from the Library’s Kluge endowment, which funds the award, are being invested in Kluge Center programming.

Chauncey joins a prestigious group of past prize winners that includes German philosopher Jürgen Habermas; former president of Brazil, Fernando Henrique Cardoso; and the groundbreaking scholar of African American history, John Hope Franklin.

Danielle Allen, a renowned scholar of justice, citizenship, and democracy, was the 2020 winner of the Kluge Prize. She held a series of events with the Library titled “Our Common Purpose,” which explored American civic life and how it might be strengthened. Faust won the 2018 prize and participated in a conversation with Hayden on women in leadership.

he Kluge Center brings some of the world’s great thinkers to the Library to make use of its collections and engage in conversations addressing the challenges facing democracies in the 21st century.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers