Library of Congress's Blog, page 30

August 22, 2022

25 Years Later, “Tuesdays with Morrie” Still Resonates

Mitch Albom. Photo: Jenny Risher.

Mitch Albom was a top-notch sportswriter three decades ago, thank you very much.

He was an award-winning columnist at the Detroit Free Press, had written a couple of books about Michigan sports figures and was popular on radio and television sports shows. People recognized him in airports. “Hey sports guy!” they’d call out, he remembers, as he hustled to catch a flight, “who’s gonna win the Super Bowl?”

Then he wrote a very short book not about sports. It was called “Tuesdays with Morrie.”

It was a memoir about visiting an old college professor who was dying and the final lessons he imparted. Albom’s book, clocking in at just under 200 pages, hit the bestseller charts … and stayed there for years. It sold more than 17.5 million copies (and still counting). It was translated into dozens of languages. Oprah turned it into a movie. It became a cultural touchstone about grief and loss.

After that, people in airports stopped asking about football. They said things like, “Hey, my mother died of cancer. The last thing we did before she died was read your book. Can I talk to you?”

“That began to happen to me multiple times a day,” Albom said in a recent interview, now 64 years old and talking from his home in Michigan. “And when I would go out and speak or talk on behalf of the book or whatever, this would happen hundreds of times. I began to hear so many stories of grief and loss and love — and what happens when you lose love. That totally changed my universe.”

Albom will be at the National Book Festival on Sept. 3 in conversation with David M. Rubenstein to discuss the 25th anniversary of the book, his popular faith-based novels and his philanthropic work in Detroit and Haiti. (He’s still a sportswriter, so he’s probably got a good take on this season’s Super Bowl, too.)

The life-changing event in his life didn’t look like that big a deal at the time.

The book began as a simple project: to help his old professor, Morris “Morrie” Schwartz, pay his end-of-life medical bills. Schwartz, the son of Russian-Jewish immigrants, taught sociology at Brandeis University in Massachusetts, where a young Albom took his classes and was touched. Years later, Albom saw Schwartz as a guest on “Nightline,” the television news show hosted by Ted Koppel. He was dying of ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

“I just went to visit him because I felt guilty that I hadn’t seen him in 16 years, even though we had been so close,” Albom said. “I … started going every Tuesday and then we started doing this sort of last class and what’s really important in life once you know you’re going to die …. Somewhere during those visits, I found out how in debt he was for his medical bills and that he was going to die and leave an enormous debt. His family was going to possibly have to sell the house just to pay off the bills. And so I got the idea that maybe I could help him pay his bills by writing a book.”

Schwartz died on Nov. 4, 1995. He was 78.

Albom’s book, subtitled “An Old Man, a Young Man, and Life’s Greatest Lesson,” was published in 1997. Though numerous publishers had rejected the project, and it started out with a small print run, it quickly became a publishing juggernaut.

Albom, a New Jersey kid, stayed on in Detroit, adopting the city as his adult home. He’s since published several novels, drawing on faith and inspiration. These have also sold millions of copies. The latest, “The Stranger in the Lifeboat,” was published late last year.

“The Stranger in the Lifeboat,” Mitch Albom’s latest novel.

“I start with the kind of lesson, or the moral thing that I want to explore, and then I create a story around that,” he said. “The characters, the plot all come from the North Star of what point am I kind of trying to make with this book? In “Stranger in the Lifeboat,” the point was about asking for help, which we all do in our own way.”

He still writes his newspaper column, but says the nine charities he runs take up “60 to 70 percent” of his time. He travels monthly to Haiti to help administer the orphanage he took over after the 2010 earthquake.

“People really took to the lessons that Morrie shared with me, because in the end,” he said, “I realize they were far more universal than they were just between Morrie and me.”

Mitch Albom will be at the National Book Festival on the Pop Lit stage Saturday, Sept. 3, at 11:05 a.m. He will be in conversation with David M. Rubenstein. He will sign books in line 7 from 12:30-1:30 p.m.

August 16, 2022

Tom Thumb’s Wedding Cake…Still at the Library, 159 Years Later

Charles Stratton (“Gen. Tom Thumb”) weds his co-star, Lavinia Warren, in New York in 1863.

The population of New York, the city’s most prominent newspaper opined in February 1863, could be divided into two groups: the lucky few who witnessed the wedding festivities of Charles Stratton … and everyone else.

Stratton, then 25 years old and 35 inches tall, was one of the biggest stars of the mid-19th century. Performing in P.T. Barnum’s shows under the name Gen. Tom Thumb, Stratton enthralled audiences in America and Europe — he appeared before a delighted Queen Victoria — with his song and dance routines and impersonations.

Stratton’s wedding to his slightly smaller co-star, Lavinia Warren, was the event of the season. The city’s elite filled the pews of the magnificent Grace Church. Outside, thousands filled Broadway or perched on rooftops, hoping for a glimpse of the happy couple.

When the newlyweds moved to the Metropolitan Hotel for the reception, the “breath-expurgating, crinoline-crushing, bunion-pinching mass,” as the New York Times put it, followed — in part because Barnum had sold 5,000 tickets to the event.

At the hotel, the newly minted Mr. and Mrs. Stratton greeted guests from atop a piano, surrounded by a motherlode of silver wedding gifts, including a ruby-inlaid miniature horse and chariot specially made by Tiffany’s.

Today, the Library preserves a little slice of that glittering history. In the 1950s, the Manuscript Division acquired a piece of the wedding cake served at the Metropolitan as part of the papers of actress Minnie Maddern Fiske and her husband, Harrison Grey Fiske, the editor of a prominent theater publication.

A slice of wedding cake from the ceremony. Manuscript Division.

Stratton died in 1883, and Lavinia eventually married the equally diminutive Count Primo Magri, who was indeed Italian but not actually nobility. In 1905, Lavinia sent a letter to the Fiskes, accompanied by the slice of cake, hoping they could give her career a boost. “The public are under the impression that I am not living,” she wrote.

Lavinia kept working into her 70s, even appearing with Magri in a silent film, “The Lilliputian’s Courtship,” in 1915. Four years later, she died and was buried beside Stratton beneath a headstone that read simply, “His Wife.”

A century later, that small piece of cake, now dark and moldy, reminds of a bright, glamourous day in the lives of two remarkable people and their city.

Sheet music for “General Tom Thumb’s Grand Wedding March,” by E. Mack. Prints and Photographs Division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 11, 2022

Hair! At the Library? Yes, and Lots of It

In 1783, James Madison gave a locket with a portrait of himself to a young woman as a token of love and attached this braided lock of his hair to the back. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

This story also appears in the July-August 2022 edition of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Of all the strange things in the Library’s collections, the most common strange thing is … hair. Lots of hair.

We have locks of it, tresses, braids, clippings and strands. We have the hair of famous people, not so famous people, and unknown people who sent their hair to someone else.

The Library holds hair from people in the arts such as Ludwig van Beethoven, Walt Whitman and Edna St. Vincent Millay; presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, John Quincy Adams, James Madison and Ulysses S. Grant; and any number of famous women, including Lucy Webb Hayes (first lady and spouse of President Rutherford B. Hayes); Confederate spy Antonia Ford Willard; Clare Boothe Luce and unidentified hair from Clara Barton’s diary.

Nearly all of the hair stems from the 18th and 19th centuries, in the era before photographs were common and lockets of hair were seen as tokens that could be anything from romantic to momentous. People might go months or years between seeing one another; a lock of hair was a meaningful talisman.

“It provided a tangible reminder of a loved one,” says Michelle Krowl, a historian in the Manuscript Division who oversees collections with many sets of clippings. “Hair from famous heads might be sought for its historic associations, similar to collecting autographs.”

The Library’s numerous hair samples, spread across multiple divisions, are incidental parts of much larger collections. Exchanging bits of hair was so common that President James A. Garfield kept a circular bit of woven hair sewed onto a small piece of paper, tied with a small green ribbon. A note in the middle reads, “My Compliments,” but there is no identification. Garfield thought it important enough to keep in his diary, so the Library preserves it as part of the historical record.

This small coil contains 26 strands of hair from Ludwig van Beethoven, obtained by an admirer following the composer’s death. Music Division.

Other samples fall into the souvenir category. Admirers cut off much of Beethoven’s after his death in 1827, so much so that a book was written about it in 2000 (title: “Beethoven’s Hair.”) A Leipzig attorney named Eduard Hase obtained a sample, but parceled much of it out to fellow fans. By the time the locks made it to the Library, the coil was just 26 strands.

Madison’s hair, though, is a thick, rich braided sample of chestnut brown. Long before he was president, the frail and delicate Madison (the shortest of all presidents at 5’4”) fell in love with Catherine Floyd, the daughter of a Continental Congress delegate. In 1783, the pair exchanged ivory miniature portraits of one another; Madison tucked a braided bit of his hair into the back of the locket. The courtship didn’t last; the locket did.

The bereaved also held on to hair as relics of their deceased loved ones, particularly during the Civil War. A small case holds a picture of a child named Carl, a locket of his hair and a note from one of his parents: “My beloved son Carl taken from me on April 1, 1865, at age 18, killed at Dinwiddie. Angels sing thee to thy rest.”

Researchers have determined the boy in the photo might be Union soldier Carlos E. Rogers of Company K, 185th New York. He was killed on March 29 or 30, in fight at Dinwiddie Court House, Virginia, less than two weeks before the Confederates surrendered.

While parents today would not likely take a bit of hair as a tangible reminder of their lost child, the impulse to hold onto something lost is with us still.

Bereaved parents preserved this lock of hair with a photo of their son, killed in the final weeks of the Civil War. Prints and Photographs Division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 9, 2022

Lamont Dozier, Legendary Motown Songwriter and National Recording Registry Member, Dies at 81

“Reach Out I’ll Be There” by the Four Tops was inducted into the 2022 National Recording Registry. Graphic: Ashley Jones.

Lamont Dozier, one third of Motown’s key hit-writing team, Holland-Dozier-Holland, has died at 81. It’s difficult to imagine the soundtrack of the 1960s without him. I chatted with him earlier this year, when the trio’s “Reach Out I’ll Be There,” was inducted into the 2022 class of the National Recording Registry. Here’s the story as it appeared in April, and best wishes for the Dozier family.

Lamont Dozier grew up in the last days of Detroit’s Black Bottom, the rough-hewn neighborhood just north of downtown that was adjacent to the jazz clubs and nightlife of the Paradise Valley section of the city.

By the early 1960s, he and his songwriting partners, brothers Brian and Eddie Holland, were in their early 20s. In a furious three-year span, they helped rewrite the city’s history as the home of Motown, the Black-owned record label that reshaped American pop music.

Holland-Dozier-Holland songs, recorded by acts including the Supremes, Marvin Gaye, the Four Tops, the Isley Brothers and Martha and the Vandellas, topped the charts and defined the Motown Sound. “Heat Wave,” “Baby Love,” “I Can’t Help Myself (Sugar Pie, Honey Bunch),” “Stop! In the Name of Love,” and “This Old Heart of Mine” were just some of the hits they wrote between 1964 and 1966.

“Reach Out I’ll Be There,” inducted into the 2022 class of the Library’s National Recording Registry, was a smash for the Four Tops in 1966. The H-D-H trio wrote it, like their other hits, in an upstairs office at Motown Studios, a converted two-story house on West Grand Boulevard. They worked from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., much like the auto factory workers in town. About the only thing in the room was a piano.

“It was a fun time, like kids playing in a playground,” Dozier, 80, said recently in a phone interview from his California home. “Everything we touched turned to gold.”

Life certainly didn’t start out that way for Dozier. Like nearly all of his Motown peers, he grew up in racism-based hardship. Blacks had fled the South for better-paying northern manufacturing jobs in the Great Migration during the first decades of the 20th century. But Detroit, among other destinations, proved to be “the promised land that wasn’t,” in the words of Rosa Parks, who fled Alabama for Detroit.

The new arrivals were forced into downtrodden neighborhoods, such as Black Bottom and Paradise Valley, where living conditions were segregated and often harsh.

“Whatever you called it, it was the ghetto,” Dozier remembers.

But jazz, the pop music of the day, had created a class of Black musicians who recorded, toured and made good money. In Detroit, Black kids grew up on that music. Many of them, like Dozier, also had relatives who played classical piano. Combined with the gospel played every Sunday in churches, a fusion emerged that would create soul, rhythm and blues and greatly influence rock and roll.

Dozier, who took to the piano after his aunt would come to their house and play Chopin and other classical composers, jumped into the local music scene when he was a teenager. He got his breakthrough from Berry Gordy, another musically minded, ambitious entrepreneur who was a few years older.

Soon after Gordy established Motown, Dozier began teaming with the Holland brothers. He and Brian Holland composed the music, sitting side by side at the piano. Eddie Holland added lyrics. They’d take the results to any number of the acts — many of whom were teenagers — who were constantly flowing through the studios.

They had their first national hit in 1963 with “Heat Wave,” recorded by Martha and the Vandellas. The next year, they emerged from their office with a song called “Where Did Our Love Go.” Dozier had composed it with the Marvelettes in mind, but they turned it down. The Supremes, who did not yet have a hit, reluctantly agreed.

It was not a happy recording session. In a 2020 interview with American Songwriter, Dozier said that he and lead singer Diana Ross were “throwing obscenities back and forth” about the key in which the song was to be recorded, and the other two singers did not like his complex arrangements for the backing vocals. They eventually agreed, he said, to just sing, “baby, baby.”

The song became the Supreme’s first No. 1 hit. (It was inducted into the registry in 2015.) The Supremes would go on to become one of the most successful acts in American music history, with 12 No. 1 songs. H-D-H wrote 10 of them.

Dozier remembers it all now with pride, saying it was remarkable how quickly the songs came to the trio in the little upstairs room.

For “Reach Out,” they were partly inspired by Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone,” in which Dylan half sang, half shouted the title refrain. They put “Reach Out” in the highest reaches of lead singer Levi Stubbs’ range, forcing his vocals to sound rough and urgent. The galloping percussion sound at the beginning of the song, which helped make it so instantly identifiable, came from musician and producer Norman Whitfield hitting a modified plastic tambourine — they removed all the jingles before the recording session.

“Brian and I came up with the melodies on the piano, sitting side by side, he would start ‘danh danh da danh’ and I’d push him over a bit and I’d play the next bar,” Dozier said. “Eddie would listen and get an idea of what should be said. The music and lyrics would come at the same time. The collaboration was something. The energy was just flying around in the room.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 8, 2022

Remembering Our Friend David McCullough

David McCullough, one of the nation’s most decorated historians and authors, died Sunday at the age of 89 at his Massachusetts home. He was a good friend of American readers and he was a good friend of the Library.

McCullough twice won the Pulitzer Prize and twice won the National Book Award (not to mention the Presidential Medal of Freedom), telling the story of both powerful and ordinary Americans, explaining the nation to itself in a genial and direct tone. He did this both in print, on the stage and on television, a thoughtful, reassuring presence. He was an honorary member of The Madison Council, the Library’s lead donor group, and appeared most recently at the National Book Festival in 2019 (before COVID-19 halted in-person festivals for two years).

“I’m saddened to hear about the passing of the great historian David McCullough,” said Carla Hayden, the Librarian of Congress. “His dedication in telling this nation’s story taught us more about the American spirit and its value to our collective history. For that we are forever grateful. He truly was an American treasure.”

He was known for his deep research and incisive narratives built on the accumulation of details and the personalities of those he studied — all traits that endeared him to librarians. He won Pulitzers for two presidential biographies: “Truman” in 1992 and “John Adams” in 2001. One of his National Book Award-winning works also focused on the presidency, “Mornings on Horseback: The Story of Extraordinary Family, a Vanished Way of Life and the Unique Child Who Became Theodore Roosevelt,” in 1981. The other NBA winner looked at the nation’s ambition and beginning world impact in “The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870-1914.”

He was popular everywhere he went — several of his books were major bestsellers — and of course he found huge audiences at the NBF. He was at the first NBF and when he was introduced at the 2019 event, the applause went on and on.

In conversation on stage with NBF director Maria Arana, he said that only late in his career had the theme of his work become apparent to him: “I see now that almost all of my books are about Americans who set out to accomplish something worthy that they knew would be difficult and was going to be more difficult even that they expected, and who did not give up and who learned from their mistakes and who eventually achieved what their purpose had been in the first place.”

McCullough was born in Pittsburgh in 1933, had a childhood which he always recalled fondly, and studied literature at Yale. He often had lunch with Thornton Wilder, the playwright and author best known for his timeless “Our Town,” itself a look at America through a fond but accurate eye. He retuned to his native Pennsylvania for his first book, “The Johnstown Flood,” an account of the 1889 disaster, launching his career from there.

David McCullough at the 2019 National Book Festival. Photo: Shawn Miller.

August 4, 2022

W.E.B. DuBois and The Brownies’ Book

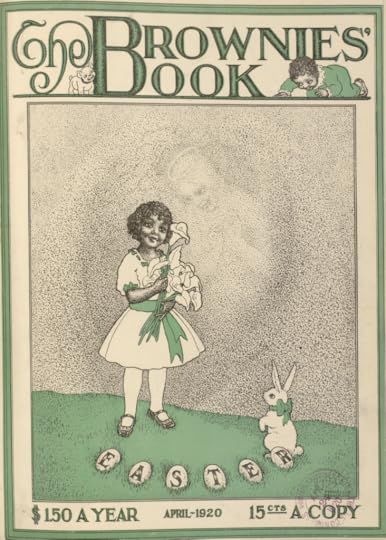

The March 1920 cover of “The Brownies’ Book.” Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

—This is a guest post by Rachel Gordon, an educational programs specialist in the Informal Learning Office. It appears in the Library of Congress Magazine and on the Library’s blog for families, Minerva’s Kaleidoscope.

In 2022, the movement for diversity and representation in children’s literature has ensured that more children can see themselves in books and learn about others’ lives, too.

A century ago, things were very different.

Writer, scholar and activist W.E.B. Du Bois recognized the need for young African Americans to see themselves and their concerns reflected in print. The Brownies’ Book, a monthly magazine for the “Children of the Sun … designed for all children, but especially for ours,” was his response.

Du Bois aimed to instill and reinforce pride in Black youth and to help Black families as they raised children in a segregated and prejudiced world. (The Library has and preserves the Brownies’s Books issues, along with many other Du Bois works and resources; use the two links above for more.)

The Brownies’ Book offered a groundbreaking mix of stories, advice, information and correspondence with the paramount goal of empowering Black children and validating their interests. Content included African folk tales, stories and poems about the origin of different races and messages about self-respect and pride in one’s appearance.

A story from the Jan. 1920 edition showcased stories of “shining examples” of children’s achievement.

The magazine also asked for “pictures and accounts of the deeds of colored children.” Readers responded enthusiastically — each issue included many photographs of African American youngsters and their activities. There are images of Boy Scouts and Girl Reserve groups, football games, debating teams, dance students, nursing school graduates and more. These must have been a welcome affirmation and validation of readers’ experiences and interests.

After just two years, financial problems ended publication of The Brownies’ Book. Today, some of the language and attitudes seem old-fashioned, and there’s some difficult content. Still, they deliver real insight into the lives and concerns of Black children a hundred years ago.

With the publication of the magazine, Du Bois aimed to create “a thing of Joy and Beauty” — or, as he put it in the dedication of the first issue in January 1920:

“To Children, who with eager look

Scanned vainly library shelf and nook,

For History or Song or Story

That told of Colored People’s glory,

We dedicate THE BROWNIES’ BOOK.”

The Easter 1920 edition of The Brownie’s Book.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 1, 2022

Bill Russell: In His Own Words

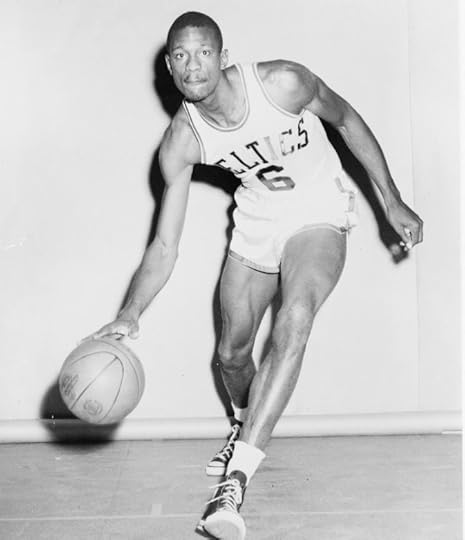

Bill Russell, who died Sunday at the age of 88, was a towering figure in American life. Standing, he went 6 feet, 10 inches. In history, he seemed to stride the continent like Paul Bunyan, like John Henry: mythical, impossible, huge.

He won basketball titles everywhere he went — high school, college, the pros, the Olympics — and won them over and over again. His coach, Red Auerbach, summed up his career of 11 NBA titles by describing him as “the single most devastating force in the history of the game.” He was among the first Black superstars in professional sports, encountered racism at a brutish level and, strikingly for the mid-century era, made no attempt to be liked by problematic fans. Woe betide anyone who might have thought of telling William Felton Russell to “shut up and dribble.”

His high-profile civil rights work included, but by no means was limited to, going to Mississippi to work for integration in the wake of the assassination of Medgar Evers and participating in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama, who noted that he “stood up for the rights and dignity” of all people.

Russell filmed an unforgettable conversation for the Civil Rights History Project, an oral history production by the Library and the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, in Seattle, Washington, on May 12, 2013. It’s three hours and was conducted by Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Taylor Branch (“Parting the Waters”). The pair combined to write Russell’s memoirs, “Second Wind: The Memoirs of an Opinionated Man.”

“I always had the confidence that my mother and father loved me,” he told Branch, right off the bat. “And what they taught me is that if they loved me, I must be OK. So if other people encounter me, and have a problem with me, my father said, then that’s their little red wagon. And so I never worked to be liked because that would be hypocritical to them.”

Bill Russell playing for the Boston Celtics, 1958. Photographer unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.

The conversation hadn’t been going for ten minutes when he tells two quick stories about his grandfather, whom he idolized. The man never went to school but was both smart and fearless. Once, his grandfather heard the Klan torturing a black man in the woods one night near his home in Monroe, Louisiana. He loaded a shotgun with cartridges filled with birdseed and fired it into the crowd half a dozen times. The crowd couldn’t find him in the dark and left. His grandfather went home, never checking on the victim.

The second story was about a white lumber store owner who took his grandfather’s money for enough wood to build a house. But when the man learned that Russell’s grandfather intended to build a school for Black children with it, he refused to give him the lumber or refund his money. His grandfather then matter of factly said he was getting the money, the lumber, or his shotgun to kill the man. He got the lumber and built the school.

“And that’s the kind of stuff where he said, ‘Bill, be sure you don’t take nothing from nobody,” Russell told Branch.

Russell, born in 1934, and the rest of the family moved to Oakland, California, when he was eight. He graduated high school and then college at the University of San Francisco, where he led his team to two national titles. Later, his daughter graduated from Harvard Law School.

“So it’s the evolution of my family from my grandfather to my kids,” he said, summing up his grandfather’s influence, “from no school to Harvard Law School.”

The interview is like that, three hours with one of the most remarkable Americans of the 20th century. It’s not always easy to listen to — the racism he encountered in Boston in the 1960s was scarcely different than the Louisiana in the 1930s — but the thing that comes shining through is the rock-solid voice of Bill Russell, American icon.

How much did he and his family value education — not so much sports?

“My most prized possession,” he famously said, “was my library card from the Oakland Public Library.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

July 27, 2022

My Job: Rachel Wetzel

Conservator Rachel Wetzel with Robert Cornelius collection items. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Describe your work at the Library.

I work in the conservation lab in the Madison Building. I am responsible for assessing, treating, housing and monitoring photographic materials within the Library’s collections. I am a liaison to the Prints and Photographs and Music divisions and to the American Folklife Center. My day-to-day tasks can vary from suggesting the proper type of storage box to performing conservation treatments on photographs that are torn, degraded, broken or damaged. I also collaborate with conservation scientists in the Preservation Research and Testing Division on scientific research studies designed to identify best conservation practices.

How did you prepare for your position?

I received a master’s degree in art conservation from (SUNY) Buffalo State College and a certificate from the Advanced Residency Program in Photograph Conservation at the George Eastman Museum/Rochester Institute of Technology. I was hired at the Library in 2019 after being employed at the Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts in Philadelphia for 12 years.

What have been your standout projects here at the Library?

I arrived eight months before the pandemic hit, so projects have looked very different for me from my early days on-site. In my first month, I was assigned three large collage photographs, each containing passport photographs of famous jazz musicians from the Bruce Lundvall collection in the Music Division. Each tiny photo was adhered with an undesirable adhesive to poor quality mat boards. I had to remove each photograph individually, reduce the adhesive on the verso and then remount them all to a new mat board in a safer, more stable manner.

We have a computerized mat cutter, and upon my first time using it I had to program it to cut out about 25 small openings for each photo with additional openings beneath each for the sitter’s name. It required a lot of precise measuring and patience to get it perfect. My colleagues seemed generally impressed with my ability to master this software and produce this mat. I was just relieved I didn’t have to cut 50 mat openings by hand.

What are your favorite collections items at the Library?

I am obsessed with 19th-century photography from Philadelphia, and the Library’s abundant collection of this was a huge factor in my decision to work here. One particular object that stands out is an album in P&P titled, “Views of Old Philadelphia, Collected by Joseph Y. Jeanes.” The album contains salted-paper prints and cyanotypes of the city, many taken by photographer Frederick de Bourg Richards in the mid-19th century. Each photograph was carefully compiled, and together the images capture the essence of the city in the most beautiful way.

De Bourg Richards was a daguerreotypist who started around 1849. He took a number of street views at a time when the rest of the city was focused on portraiture. More peculiarly, he photographed other earlier daguerreotype street views made by William G. Mason in the early 1840s and reprinted them in paper formats as part of this series. The concept of photographing the photograph this way is alluring, so this album is high on my list of research projects in the near future.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

July 25, 2022

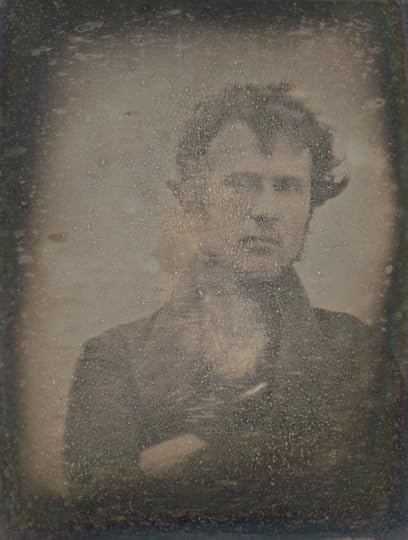

Robert Cornelius and the First Selfie

The world’s first “selfie,” a self-portrait taken by Cornelius in 1839. Prints and Photographs Division.

A 30-year-old man stood alone in the yard of his family’s Philadelphia gas lighting business. The year was 1839, and it was late October or early November. In front of him was a makeshift camera, its lens fashioned from an opera glass.

He’d already determined the daylight was adequate to expose the carefully prepared metal plate within the camera and take a photograph of himself. Last but not least, he had to remain motionless and gaze forward for 10 to 15 minutes — no easy task.

The man was Robert Cornelius, and people sometimes joke that he took the world’s first selfie that day when he posed in his yard, broodingly handsome with his collar upturned and his hair disheveled. But he accomplished much more than the term “selfie” implies.

“Taking a portrait is astounding in 1839,” said Rachel Wetzel of the Library’s Conservation Division. “Taking a self-portrait is a whole next level up from that. That portrait is incredibly significant.”

Cornelius’ picture, a daguerreotype, is considered the earliest extant photographic portrait in the world. The Library acquired it in 1996, along with other examples of Cornelius’ works, as part of the Marian S. Carson collection.

A collection of Cornelius material recently acquired by the Library included this original camera lens. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Now, the Library’s Cornelius holdings, already the largest anywhere, have grown even bigger: In December, Cornelius’ great-great-grand-daughter, Sarah Bodine, donated an important collection of his photographic materials and ephemera.

The trove includes a Cornelius daguerreotype and portraits of his children by other early Philadelphia daguerreotypists, along with Cornelius’ experimental camera lenses and papers associated with his business dealings and patent applications.

“The collection gives a much broader picture of Robert Cornelius at the Library, beyond the photographs we currently hold,” said Micah Messenheimer of the Library’s Prints and Photographs Division.

It is thanks largely to Wetzel’s expertise in all things Cornelius that the Bodine collection made its way to the Library.

Before joining the Library in 2019, Wetzel worked as a photo conservator at the Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts in Philadelphia (CCAHA). There, she and a team of conservators drawn from across institutions, including two from the Library, conducted research on early daguerreotypes and how best to preserve them.

A film storage box used by Cornelius. Photo: Shawn Miller.

To deepen knowledge of Cornelius’ work and techniques, Wetzel also began compiling a database (which now resides at the Library) to document his photographs and their condition. Even though Cornelius photographed subjects for only three years, he was enormously successful, and his photos now exist in far-flung locations.

Just months before Cornelius took his self-portrait in 1839, Louis J.M. Daguerre announced his invention of the daguerreotype process in France and published the formula. Cornelius’ collaborator, scientist Paul Beck Goddard, soon altered Daguerre’s formula for treating camera plates by combining bromine with iodine — Daguerre used just iodine.

The new treatment reduced exposure times — by a lot. So, instead of sitting in front of a camera for up to 25 minutes, a photographic subject had to remain still for only 30 seconds to two minutes.

“For portraiture, it was a big thing,” Wetzel said.

Most significantly, it made the daguerreotype process commercially viable. Cornelius set up Philadelphia’s first photo portrait studio to much acclaim. His portraits were so esteemed that Daguerre himself reportedly sent daguerreotypes from France in exchange for Cornelius’ work.

This daguerreotype shows the view from the window of Cornelius’ second- floor studio at 8th and Lodge. Prints and Photographs Division.

Publicity surrounding Wetzel’s quest to find and document Cornelius’ photography eventually brought her into contact with Bodine — and two other Cornelius descendants.

Robert Cornelius IV, who goes by Bob, was the first to get in touch. He brought his Cornelius daguerreotype to Wetzel at the CCAHA. Later, Bob brought his cousin from Connecticut, Albert Gee, another descendant, to show Wetzel his Cornelius materials.

Bodine found Wetzel, by then at the Library, through a Google search. Bodine had recently discovered Cornelius materials in her attic in New Jersey as she was downsizing to move. She had it in mind to donate the materials to a repository, but she wanted to know more about them first. So, she invited Wetzel to visit.

Wetzel brought Bob with her to New Jersey. He did not know Bodine, a cousin, beforehand. She descends from a different Cornelius child — Cornelius and his wife, Harriet, had eight children together.

Wetzel spent a day and a half with Bodine going over her materials. The collection includes one daguerreotype by Cornelius along with portraits of his family members and copious ephemera — deeds, calling cards, news clippings, a valentine to Harriet Cornelius from her husband, the eulogy he wrote for her in 1884 and locks of her hair and his.

Seven patent applications relate to improvements Cornelius invented for gas lighting, his family’s business, to which he returned after his brief but storied foray into photography.

A favorite item in Bodine’s collection is a box containing lenses wrapped in what looked like a cut-up nightshirt that still had a tag embroidered with a small “C” on it.

“Thinking about how the lens that might have been used to make that self-portrait could have been in that box was pretty thrilling for me,” Wetzel said.

Wetzel is continuing to study early daguerreotypes, analyzing how they age and ways to stabilize them. She’s now working with Messenheimer to create a database of every daguerreotype in P&P’s collection, documenting the condition of each with notes and photographs.

“While my work has focused on Cornelius,” Wetzel said, “all of the best practices that are being developed through the Cornelius project will be applied to ensuring the longevity of every daguerreotype at the Library.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

July 21, 2022

Library of the Unexpected: Cocaine, Hair and…Wedding Cake?

The contents of Lincoln’s pockets the night he was assassinated. Photo: Shawn Miller. Prints and Photographs Division.

This article also appears in the current issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

When a Library collects more than 171 million objects over the course of a couple of centuries, odds are that some unusual items will filter into the mix. Along with traditional library fare such as books, maps, manuscripts, magazines, prints, photographs, movies and recordings, the Library has … other things.

Like a piece of the World Trade Center and a piece of cake from Gen. Tom Thumb’s wedding (now nearly 160 years old). Here’s a secret Vietnam War POW list, written on toilet paper, and there’s a 1,000-year-old postclassic Mayan incense burner in the shape of a diving bat. We have an unidentified lock of hair from Clara Barton’s diary, and the whiteboard upon which astronomer Carl Sagan sketched out the plot to the movie “Contact.” Here’s a set of dessert plates hand-decorated by Rudyard Kipling, and there’s a map of the Grand Canyon made entirely of chocolate. Burl Ives’ custom-made guitar, anyone? Walking sticks of Charles Dickens and Walt Whitman? An Oscar for “High Noon” or Leonard Bernstein’s vanity license plate (“Maestro”) from his Ferrari?

All of those are real. But it is not true, no matter how delightful the rumor, that the Library has a very small stash of Sigmund Freud’s cocaine. We have a very small stash of Freud’s friend’s cocaine.

Also, we have a tuft of Canadian “muskox wool” from the collection of — did you doubt this? — Teddy Roosevelt.

“It is a capital misfortune,” Roosevelt wrote in 1918 to the explorer who sent it to him, “that the muskox has not been tamed.”

The Library preserves items from the 1918 influenza pandemic: A bottle of “Flu-Oil,” a jar of “Ec-to Balm” and two medals identifying medical workers. Photo: Shawn Miller.

These are all eyebrow-raising exceptions to the rule of what the Library collects. The Library is home to the national narrative, the papers of presidents, politicians, artists, inventors and everyday citizens. The Library’s mission is to serve Congress and preserve the nation’s story, along with a good bit of world knowledge. It’s not an artifact-filled museum and does not double as a collector of oddball ephemera.

But it would also be a capital misfortune if the nation’s library did not have a scattering of such delightfully offbeat and wholly original items. These items came in as part of larger collections and we kept them because the Library is also a history of us, of humankind, and that messy history can’t all be contained on paper, vinyl, film and tape. These are some of the items that help give the tactile sense of bygone people who were about our size and height, who lived with the same phobias and desires that we do today. They offer a bit of needed spice, of raw humanity.

Take Whitman’s walking stick. Put that and his haversack in hand and you can take the measure of the man himself. Along with a bronze cast of his hand (we have that, too), you get the sense of what a big-boned man he was, no matter the delicate nature of his poetic lyricism. If he shook your hand, you’d remember the grip.

The beginning of Norma Jenner’s letter to her husband, Joseph, a soldier in World War II.

Or consider lipstick kisses. Wives and girlfriends puckered up onto pieces of paper and sent them to their boyfriends and husbands in World War II (if not before), as the Veterans History Project documents. The colors are still vibrant.

“Darling, I really did kiss the paper and it was quite without a kick,” wrote Norma Jenner to her husband, Joseph, an Army corporal serving in Europe, on June 10, 1944, on a bright pink sheet of stationery designed for such smackers. “I’d much rather it were your lips.”

Aviators in World War II also signed currency for one another, sometimes stringing bills together into long strips. They were nicknamed “short snorters” after shots of whiskey, and the Library has a few. The toilet paper, a list of American POWS kept among themselves, including a young John McCain, is from the notorious “Hanoi Hilton” in Vietnam. Combined, these pieces give a visceral sense of the passions of war.

The contents of Abraham Lincoln’s pockets the night he was assassinated give us insight into the everyday aspect of the man’s life. They are touching and, in their way, almost impossibly sad. His brown leather wallet, containing a Confederate $5 bill and eight newspaper clippings. An embroidered linen handkerchief. A watch fob. Spectacles, mended with a piece of string. A pocketknife.

These are not the belongings of an immortal icon, striding through history. They are the belongings of a self-educated man born on the frontier of a rough nation, Robert’s father, Mary’s husband; perhaps a slightly distracted man who went out for an evening of comic relief at a theater and never came home. The items he carried show his life arrested in stop motion. They were not displayed at the Library until 1976, when then-Librarian of Congress Daniel J. Boorstin thought they would give a human touch to a president who was “mythologically engulfed.”

The Library captures lives around the world, too.

In Vienna in the early 1880s, at the city’s General Hospital, we meet a neuropathology lecturer named Sigmund Freud. He’s not yet famous, but he’s got big dreams.

This cocaine belonged to physician Carl Koller, who experimented with the drug as an anesthetic used during eye surgery. Photo: Shawn Miller. Manuscript Division.

Meg McAleer, the historian who oversees the Freud collection, explains that Freud and fellow doctors were experimenting with the pharmaceutical benefits of cocaine. Such a sense of calm! No anxiety in social situations! And what a feeling of strength! Freud even sent a vial to his fiancé. He published on the potential therapeutic uses of cocaine (depression, pain management, exhaustion, morphine addiction) in June 1884.

But then Carl Koller, a physician in his circle, began to experiment with cocaine at Freud’s urging. Koller subsequently made a breakthrough of using it as an anesthetic during eye surgery that same year. It made him world famous, much to Freud’s chagrin. Freud wrote to his fiancé on Oct. 29, 1884: “The cocaine business has indeed brought me much honor, but the lion’s share to others.”

Koller, meanwhile, put a tiny bit of the excess cocaine he’d used in that groundbreaking surgery in an envelope and tucked in his files. More than a century later, when his daughter donated a collection of his papers to the Library, staff members came across the envelope during processing. The FBI verified that the “fine, white, slightly yellow powder” was inert. It was returned to a vault.

People in South America, the native ground of the coca plant, had been chewing its leaves for thousands of years before Freud came along, and the Library also has rare coca bags from Mexico that are more than 2,000 years old. Alongside those is a green stone bead, also more than 2,000 years old, that still has a piece of necklace cord or twine running through it. This would have been suspended around the neck of a Maya, Nahua or Olmec noble.

This 2,000-year-old bead, once part of a necklace, still has a bit of twine running through it. Geography and Map Division.

“It’s not just a piece of stone but also an example of a complex interaction between an ancient craftsperson and their environment,” says John Hessler, curator of the Jay I. Kislak Collection of the Archaeology and History of the Early Americas. “Here we find not only a piece of material culture but also the preservation of a moment in time, of a person just being in the world.”

As Hessler points out, in items like these there’s the indescribable magic, the gasp-inducing sense of touch. When we hold the things of those who went before us, it shows us that his hand went here. Her pen moved along the page just there.

It is as close to touching ghosts as we can come.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers