Library of Congress's Blog, page 26

February 1, 2023

Black History Month, Day 1: A Petition for Justice Nearly 20 Yards Long

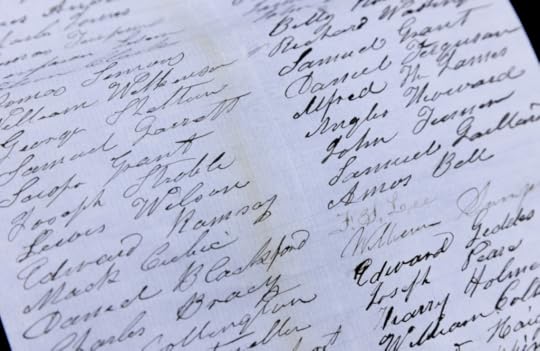

A small section of the unrolled petition. Manuscript Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

This is a guest post by Michelle Krowl, a historian in the Manuscript Division. It appears in the Jan.-Feb. issue of the Library of Congress Magazine .

In the wake of emancipation during the Civil War, African Americans submitted petitions to government entities in greater numbers than ever before to advocate for equal treatment before the law.

One such petition, submitted by Black South Carolinians just months after the war ended, is unusual: The introductory page containing the text addressed to the U.S. Congress is followed by individual pages of signatures glued end-to-end to form a document that is just over 54 feet in length when fully extended.

According to the Congressional Globe (the predecessor of today’s Congressional Record), on Dec. 21, 1865, Sen. Jacob Merritt Howard (R-Mich.) introduced a petition to the Senate, then meeting in the first session of the 39th Congress.

Howard noted that the petition contained 3,740 signatures of Black South Carolinians, who requested that Congress ensure that any new state constitution adopted in South Carolina following the Civil War guarantee African Americans “equal rights before the law.”

The petition contains 3,740 signatures. Manuscript Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

The text of the petition further advocated “that your Honorable Body will not sanction any state Constitution, which does not secure the exercise of the right of the elective franchise to all loyal citizens,” as “without this political privilige [sic] we will have no security for our personal rights and no means to secure the blessings of education to our children.”

Howard requested that the petition be referred to the Joint Committee on Reconstruction.

Little is currently known about this petition in terms of the conditions under which it was created or how it came to be part of the Manuscript Division’s papers of Justin S. Morrill, a Vermont congressman and U.S. Senator of the era.

The petition may have been created in conjunction with the “State Convention of the Colored People of South Carolina,” which met in Charleston from Nov. 20 to 25, 1865, which also produced a memorial to Congress containing different text.

Morrill (R-Vt.) served on the Joint Committee of Reconstruction, so it is possible the petition came into his possession during his committee service. Organized as part of the “Miscellany” series of the Morrill Papers, the petition seems to have been little known until recently.

After Manuscript Division staff became reacquainted with it, the document was displayed as part of the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s exhibition on Reconstruction, which ended last year. The issues of race, citizenship and voting rights that would be critical during the Reconstruction period that followed the Civil War, however, continue to be relevant.

The Library’s By the People crowdsourcing project is planning a transcription campaign of the document this spring, with the goal of making the signatures more discoverable and encouraging further contextual research on the signers and the petition’s creation.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

January 30, 2023

A Voice Among the Stars: Poem by U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón Will Ride to Europa on NASA Spacecraft

U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón, who is known for work that explores the human connection to the natural world, is crafting a new poem dedicated to NASA’s Europa Clipper mission.

Her poem, to be released in the coming months, will be engraved on the Europa Clipper spacecraft. It will travel 1.8 billion miles on its path to the Jupiter system – and will be part of an upcoming NASA-led program that will invite international public participation.

The spacecraft is set to launch from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in October 2024 and by 2030, it will be in orbit around the gas giant. It will conduct multiple flybys of Jupiter’s icy moon Europa, to gather detailed measurements and determine if the moon has conditions suitable for life. Europa is thought to contain a massive internal ocean and is considered one of the most promising habitable environments in our solar system, beyond Earth.

More information – about the new work by Limón and how the public can get involved – will be released in the coming months. The project is a special collaboration, uniting art and science, by NASA, the U.S. Poet Laureate and the Library.

Meanwhile, Europa Clipper is under construction at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, and the work is broadcast live, 24-7 from JPL’s Spacecraft Assembly Facility. In addition, you can check out these other ways to learn more and to participate in the mission.

Limón, 46, was appointed 24th Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry by Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden last year. She was born in Sonoma, California, and is of Mexican ancestry. She is the author of several poetry collections. “The Carrying” won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry and “Bright Dead Things” was a finalist for the National Book Award and the National Books Critics Circle Award. Her most recent is “The Hurting Kind,” published last year.

Her official position — the Library’s Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry — was created in 1937, when Archer M. Huntington endowed the Chair of Poetry at the Library. Previous laureates include Joy Harjo, Tracy K. Smith, Juan Felipe Herrera, Robert Penn Warren, Rita Dove, Robert Frost and William Carlos Williams.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

January 26, 2023

Posters Power!

An 1893 poster by Jules Cheret, showing a fashionable Parisian woman ice skating. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by Sahar Kazmi, a writer-editor in the Office of the Chief Information Officer. It appears in the January-February issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Before the internet meme, there were posters.

Once upon a time, posters full of dazzling images and arresting slogans dominated the media landscape. They were displayed in shop windows, covered billboards and were even draped over human bodies — the so-called 19th-century “sandwich men” who patrolled city sidewalks carrying advertising posters over their shoulders.

Posters were designed to speak to the people, to catch their attention and evoke their curiosity. Not unlike today’s memes, they spoke to cultural trends, replicating and repeating popular artistic styles, often with an amusing twist. Perhaps most notably, they brought art to the masses.

The Library’s collection of posters traverses nearly two centuries and multiple continents. Its contents tell the story of an evolving form that exhibited the work of major artists and promoted everything from food to political candidates.

They tout dance shows and circuses, tourism and theater, military recruitment and social rebellion. They advertise household goods and mind-melting drugs. They sell war bonds and butter, victory gardens and deli meats.

“Five Celebrated Clowns,” creating art (and nightmares) since 1856. Morse, M’Kenney and Company. Prints and Photographs Division.

One of the Library’s oldest posters, an enormous (and possibly, for some, terrifying) woodcut print titled “Five Celebrated Clowns” hails from 1856. Punctuated with bright blues and tangerine reds, the poster for Sands, Nathans & Company’s Circus features five clowns with painted faces, flouncy collars and polka-dot tights posed in exaggerated pantomime gestures.

They are distinctly American — one is even decked out in the patterns of Old Glory — and their sheer size gives a hint about the scale and popularity of circuses in the era. But the Library’s many European posters also showcase the cultural significance and artistic impacts of the medium in its early heyday.

The elegant work of 19th-century French artist Jules Chéret, an example of which is at the top of this post, showcases women at play and leisure, demonstrating their more liberated roles in the Paris of the Belle Époque. Among the Library’s assorted Chéret posters, women in ornate and sometimes sensual fashions are depicted riding bikes, ice skating or reading the newspaper. The characters in Chéret’s posters, who became known as Chérettes, embodied a whole new ethos of womanhood — vivacious and cosmopolitan.

Other artists, too, used posters to push the bounds of old social mores. In one print from painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, a glamorous woman in a red dress plants a bold kiss on an older gentleman over dinner. The poster served double duty as the cover of a book from author Victor Joze, although it has since far surpassed the novel in fame.

The figures in Ethel Reed’s posters are mysterious and darkly alluring, such as the sly red-haired woman who holds a vivid poppy on the otherwise entirely black book cover for José Echegaray’s “Folly or Saintliness.”

Another often-reproduced example from Henri Privat-Livemont shows a woman in diaphanous fabrics as she raises a glass of absinthe in practically spiritual awe. Billowing curlicues dance in the background, the intoxicating terrain of the “Green Fairy.”

Revelry and entertainment are common themes in poster art spanning the ages. In the Library’s collection of works from Czech artist Alphonse Mucha, plays and concerts are advertised like scenes in an elaborate painting.

The poster for a performance of the play “Lorenzaccio” features opulent golden lines and delicately detailed borders surrounding a snarling green dragon as it peers down at the titular character, lost in thought. Mucha’s poster for the play “La Dame aux Camélias” is equally sumptuous, presenting an ethereal lady Camille against a background glittering with silver stars.

With such magnificent images posted in public spaces, it wasn’t uncommon for Mucha’s posters, and those of his contemporaries, to routinely be stolen by art lovers. Decades later, psychedelic poster art promoting rock-and-roll concerts would become equally covetable for collectors.

The Library’s collection of works from Wes Wilson, dubbed the father of the 1960s rock poster, flaunt swirls of eye-popping neon text contrasted against dramatic human figures. One poster for a concert featuring the Grateful Dead and Otis Rush & His Chicago Blues Band depicts a woman’s face in profile, the names of the event’s performers spiraling through her hair in a trippy kaleidoscope of pink and seafoam blue.

The Library’s posters aren’t all fun and games, though.

Between the liberated merrymaking of the Belle Époque and the experimental decadence of the Swinging Sixties were two world wars that shook the soul of the planet. Strife and survival were foremost in people’s minds, and governments and revolutionary causes alike seized on the atmosphere to capture the public’s attention.

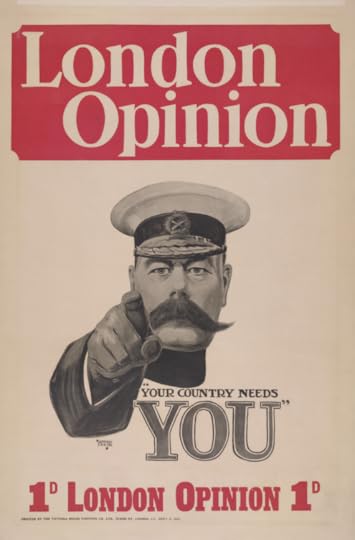

This British poster from World War I inspired the famous “I Want You” Uncle Sam poster for the United States military. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Library holds an original World War I poster of Britain’s Secretary of State for War Earl Kitchener pointing straight at the reader. The text reads, “Your country needs you.” It was this image that inspired James Montgomery Flagg’s definitive portrait of a white goateed Uncle Sam a few years later.

In one, a U.S. Marine points at the viewer. In another, a stern Statue of Liberty invokes the reader to buy war bonds. There’s a pointing poster of a Black Uncle Sam, and even an anti-war poster in which a bandaged version of Flagg’s Sam extends an open hand pleading, “I want out.”

Russian and Soviet propaganda posters, too, are widely known for their distinctive style, a “constructivist” technique full of hard lines and abstract shapes. The Library holds a reproduction of a famed 1920 example from the artist El Lissitzky, in which a red triangle symbolizing the Bolsheviks wedges into a white circle representing anti-communist forces. The design has been replicated on album covers, in the sci-fi television series “Farscape” and most recently on Russian billboards promoting COVID-19 vaccination, in which the white circle now appears as a spiked coronavirus cell.

These variations stand as sterling examples of the cultural weight and staying power of poster imagery. Their creators often printed hundreds if not thousands of copies. Much more than just information bulletins, posters encapsulated cultural moods and reflected shared ideas.

Dorothy Waugh’s colorful prints advertised U.S. National Parks in stunningly bold designs fit for modern travelers. Japanese tourism posters spotlighted blushing cherry blossom trees against steely cityscapes and winding rivers, inviting visitors to experience a country both innovative and idyllic.

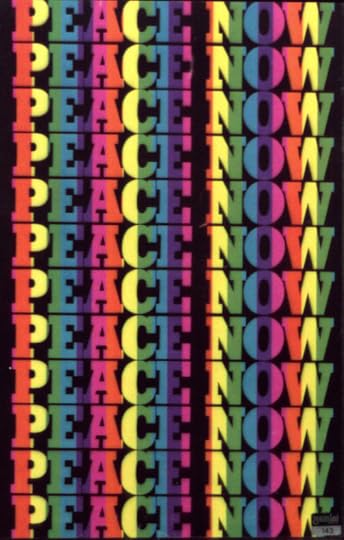

“Peace Now,” a poster created by Gemini Enterprises during turbulent late ’60s and early ’70s. Prints and Photographs Division.

In one of the most remarkable displays of the poster’s persuasive powers, the Library’s Yanker Poster Collection contains political and social issue posters from dozens of nations, primarily created in the 1960s and 1970s. Through their striking artwork, they call for world peace, the Equal Rights Amendment, recycling programs, union strikes, cancer screenings and political candidates.

One poster repeats “Peace Now” in rainbow letters across its width, from top to bottom. Another depicts a simple flower with the words, “War is not healthy for children and other living things,” winding through its stem. On another, an image of a shattered globe, bursting with mud and worms, hangs in black space. At the bottom, a brief message: “Love is the answer.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

January 23, 2023

Bewitched by TV Themes

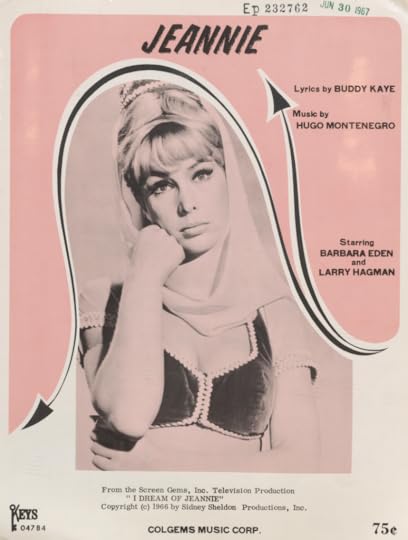

The sheet music for “Jeannie,” the theme song to the hit TV show. Music Division.

Most folks know the ridiculously catchy instrumental theme song for the 1960s classic TV comedy “I Dream of Jeannie.” But how many can recite its lyrics — “Jeannie, fresh as a daisy!/Just love how she obeys me” — or even knew it had any?

The theme for “Bewitched,” another ’60s favorite, briefly had its day: Peggy Lee, among others, recorded a jazzy vocal version in 1965. The lyrics weren’t used in the series, however, and over many decades of reruns faded from public consciousness.

The original lyrics for both songs, and countless others, are preserved in Library collections as submissions to the U.S. Copyright Office, which is part of the Library. Such submissions for registration help preserve mostly forgotten stories about pop culture staples: They chronicle the creators’ original ideas and, sometimes, the subsequent histories of their works.

In 1966, Alexander Courage composed the theme music for a new show, called “Star Trek,” and submitted it for copyright under his name that Nov. 7.

Fifty days later, the Copyright Office received a second registration for the same music — with two additions. Beneath Courage’s name, another had been written — that of series creator Gene Roddenberry — in a different ink and handwriting. Below that, lyrics had been scrawled alongside the music.

The “Star Trek” theme, Courage had understood, would be instrumental. But a clause in Courage’s contract allowed Roddenberry to add lyrics if he chose. So, he did: “Beyond the rim of the starlight/My love is wandering in starflight.”

The lyrics never were used in the show and weren’t intended to be. Roddenberry had other motivations: He received a co-writer credit for the lyrics — and 50% of the royalties. Courage’s share, meanwhile, was cut in half.

The financial ramifications, it turned out, were enormous.

“Star Trek” ran for only three seasons but lives on in syndication (the Associated Press once dubbed it “the show that wouldn’t die”). It also spawned other TV series, video games, novels, comic books and, to date, over a dozen films.

Courage’s original theme, in some form, has been heard in every film — living long and prospering.

The sheet music to the “Star Trek” theme, with Gene Roddenberry’s credit added.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

January 18, 2023

Meet Meg Medina, the Library’s New Ambassador for Young People’s Literature

Meg Medina, the new National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature. Photo: Scott Elmquist.

Meg Medina, a writer whose work explores how culture and identity intersect through the eyes of children and young adults, today was named as the National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature for 2023-2024, the Library of Congress and Every Child a Reader announced.

Medina, a Cuban-American, is the eighth author to hold the position and the first of Latina heritage to do so. She succeeds Jason Reynolds, whose term stretched from 2020 through 2022.

“I am delighted Meg Medina will serve as the next National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature,” said Carla Hayden, the Librarian of Congress. “Meg’s warmth and openness, coupled with her long-running commitment to young readers, libraries and librarians, is extraordinary. I look forward to the ways she will invite young people — especially Spanish and bilingual speakers — to share their favorite books and stories.”

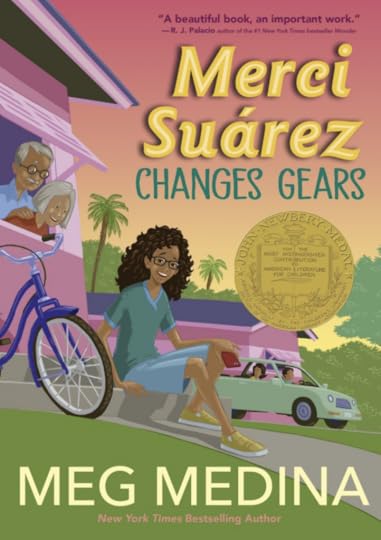

Medina’s middle-grade novel, “Merci Suárez Changes Gears,” the first of three books in a trilogy about the Suárez family, received the 2019 Newbery Medal and was named a notable children’s book of the year by the New York Times Book Review. Her young adult novels include “Yaqui Delgado Wants to Kick Your Ass,” which won the 2014 Pura Belpré Author Award and will be published in 2023 as a graphic novel illustrated by Mel Valentine Vargas; “Burn Baby Burn,” which was long-listed for the National Book Award; and “The Girl Who Could Silence the Wind.”Her most recent picture book, “Evelyn Del Rey Is Moving Away,” received multiple honors, including the 2021-2022 Charlotte Zolotow Award.

Raised in Queens, New York, Medina, 59, now lives with her family in Richmond, Virginia.

“It’s an enormous honor to advocate for the reading and writing lives of our nation’s children and families,” Medina said. “I realize the responsibility is critical, but with the fine examples of previous ambassadors to guide me, I am eager to get started on my vision for this important work. More than anything, I want to make reading and story-sharing something that happens beyond classroom and library walls. I want to tap into books and stories as part of everyday life, with all of us coming to the table to share the tales that speak to us and that broaden our understanding of one another.”

For her two-year term, Medina will engage readers across the country through her new platform, “!Cuéntame!: Let’s talk books.” Inspired by the Spanish phrase that friends and families use when catching up with one another, ¡Cuéntame! encourages conversations about books that reflect the readers’ experiences and those that expose readers to new perspectives.

“Merci Suárez Changes Gears” won a 2019 Newbery Medal.

Medina’s work will include encouraging families and young people to build relationships with their local libraries. She’ll also create materials to introduce and connect readers with authors across a range of styles and genres. During in-person visits with students, she will discuss her work and host book talks.

Hayden will inaugurate Medina into the role on Jan. 24 at 10:30 a.m., in a ceremony at the Library. Reynolds will be on stage as well. Local school groups will be in attendance, too. The event will be livestreamed on the Library’s YouTube page.

“We couldn’t be more pleased with the selection of Meg Medina as the next ambassador,” said Carl Lennertz, executive director of Every Child a Reader and the Children’s Book Council. “She will inspire young people of all ages over the next two years with her energy, ideas and passion for reading and storytelling.”

The National Ambassador is chosen for their contributions to young people’s literature, the ability to relate to children and teens, and dedication to fostering children’s literacy. The selection, made by the Librarian, is based on nominations from a diverse pool of distinguished professionals in children’s publishing and from an independent selection committee comprising educators, librarians, booksellers and children’s literature experts.

The program was established in 2008 by the Library, the Children’s Book Council and Every Child a Reader. It is supported by the The Library of Congress James Madison Council, The Capital Group Companies Charitable Foundation and Dollar General Literacy Foundation.

Previous National Ambassadors include authors Jon Scieszka (2008–2009), Katherine Paterson (2010–2011), Walter Dean Myers (2012–2013), Kate DiCamillo (2014–2015), Gene Luen Yang (2016–2017), Jacqueline Woodson (2018–2019) and Jason Reynolds (2020-2022).

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

January 17, 2023

Picasso, Man Ray and Modernist Wonders on Display! One Night Only!

“The Meeting” by Man Ray, from “Revolving Doors,” 1926. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

This is a guest post by Emily Moore, assistant curator of the Aramont Library.

What is a book, exactly? Is it an object, made of paper and ink? Is it a portal to a different reality, an embodiment of memory or a method of communicating across space and time? Can it be art?

“Making the Modern Book: The Aramont Library,” a Jan. 19 symposium in the Library’s Coolidge Auditorium, will present some of our treasures to ask just that question. We are thrilled to host this event and introduce the collection to everyone. The afternoon and evening events will treat you to an exploration of the Aramont, a stunning modernist collection of 1,700 volumes that is as much about art as it is about books.

Housed in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division, the Aramont is home to first editions, livres d’artistes (books by artists) and exhibition bindings. It features authors such as James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, Joseph Conrad, William Faulkner and Willa Cather, plus giants of the art world including Pablo Picasso and Max Ernst. Speakers at the symposium will include artists, bookmakers, publishers, scholars and book dealers. In two sessions, they will explore the collection’s holdings while examining the intersection of modernism, art and the book. Afternoon lectures will be followed by an evening display of some of the most impressive books, along with roundtable discussions. This event is free and open to the public.

Pablo Picasso, photographed by Man Ray in 1932. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Rare Book Division is home to many strange and beautiful objects. It’s a place where you can find Charles Dickens’ walking stick next to antique paper toys and where obscure medieval manuscripts live alongside Harry Houdini’s scrapbooks.

It’s also home to the Aramont collection, a 2020 donation from a private collector who spent decades assembling it. It’s composed of works from the 17th to the 20th centuries, with an emphasis on livres d’artiste. It’s also a stunning collection of bespoke bindings, featuring works by Sangorski & Sutcliffe, the Doves Bindery and six bindings by Paul Bonet, the most celebrated binder of the 20th century.

As a collection, the Aramont embodies modernism and experimentation, a spirit captured in one of its most beautiful holdings: Man Ray’s “Revolving Doors.”

Self-portrait by Man Ray, 1930. Prints and Photographs Division.

The 10 pochoir (stencil) prints that make up “Revolving Doors” were made in 1926, based on a series of paper collages created by Ray during World War I. First exhibited at the Daniel Gallery in New York, Ray designed the pages to hang from a metal structure. Suspended in the gallery, the prints evoked their title, revolving and responding to the breeze and flow of the room. Viewers were encouraged to move the prints themselves – a gesture of co-authorship that expressed Ray’s interest in challenging traditional power structures, both in the art world and society at large.

His use of line and pigment demonstrates his interest in taking the height/length/width of art and putting it into motion, creating what he called the fourth dimension. His sharp transitions of color combined with lines, squiggles and overlapping shapes that respond and reach to each other in space.

These interactions mimic people passing, sounds of the street and other features of city life. This play between color and line, between machine, environment and form, makes Ray’s work dynamic and exuberant – through stripping objects down to their bare essentials, he uncovers their primal vitality and expression.

“Revolving Doors” is one of the many modernist masterpieces held in the Aramont. The collection’s body of livres d’artistes offer Library visitors the unique opportunity to page through original works of art. Its first editions are often inscribed by the authors and still in their original dustjackets. In many ways, the Aramont is a collection that is bigger than the sum of its parts, offering a sensory experience equal to an intellectual one. And now is your chance to see it.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!January 9, 2023

Jason Reynolds: Grab the Mic One Last Time

This is the final guest post by Jason Reynolds, who is concluding his third term as the National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature.

This is the final guest post by Jason Reynolds, who is concluding his third term as the National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature.

FIVE WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE (a farewell newsletter)

SEE YOU SOON. This is not the same as, See you later. I repeat, this is not the same as, See you later. “See you later” lacks urgency. It lacks seriousness and commitment. But my time as your National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature was certainly very serious to me and I was relentlessly committed. So to walk away from it, to bow out with a cavalier, See you later, is like throwing my hand up and waving goodbye while already turned away. Instead, I’ll say, See you soon. Because soon implies effort. That I’ll work to still be a light, partially to shine on the next ambassador, and always to shine on you.No words. Just the involuntary vibration our bodies experience whenever we feel joy, and sometimes anxiety. In this case, both fit the bill. We spent so much time joking around, finding new things to laugh about, new ways to find spiked moments of bliss in such a complicated time, and we’ll need the laughter to linger as we part. I met a lot of you who were nervous to talk to me at first, and there would be nervous laughter. But by the end of our time, I’d like to think even if some of the nerves were still there, most of our hooting became rooted in relationship. That we got the joke. And still get it. So we get each other.KEEP TRYING. As I take a step back, as I take off my medal, remove myself from this incredible position, I want us, you and me, to make a promise to each other. I promise to keep trying, if you do.THANK YOU. One of the best ways to say goodbye. It can be interchanged with, I love you. They both work, and they typically have the same effect. You should know, I have been forever changed. Serving you these last three years has confirmed everything I already thought about the young folks of this country. That they love. And love big and wide and deep and high and whole. That they love enough to cry for their peers—I’ve seen it—or to cheer for them as if they are already famous. I’ve seen this, too. So, I could say I love you, but you already know that. Instead, in this moment, I’m going to offer some gratitude. Thank you for reminding what it is to be human. And for trying. And laughing. With effort and urgency.DON’T. That’s all. Just don’t. Instead, say, hi. Reach out and let me know when you’ve dunked for the first time, or when you’ve written your first poem, or got your first pair of Jordans, or got your learner’s permit, or booked the role, or got into college, or made the team, or passed that class, or finally finally finally finished reading your first book. And I’ll tell you, hopefully, that I’ve just woken up from a sweet, sweet nap. My first in a while.January 5, 2023

“The Master of Mysteries,” Latest in Library’s Crime Classics Series

“The Man of Mysteries,” the newest title in the Library’s Crime Classics series.

This is a guest post by Polina Lopez, Widening the Path intern in the Library’s Publishing Office .

Can one detective successfully solve kidnapping, espionage and murder cases, uncover social poseurs and secret love affairs, all while maintaining the guise of psychic powers? In the newest addition to the Library of Congress Crime Classics series, Gelett Burgess’ Astro the Seer does all that and more, proving he is “The Master of Mysteries.”

In this collection of short stories, victims bring their troubles to Astro, who, they believe, finds solutions by consulting their auras and vibrations. In reality, as soon as his clients leave, Astro sheds his turban and robe and assumes the role of a private detective. He interviews witnesses, follows suspects, stakes out hideouts and uses scientific methods of the day. However, Astro’s most effective weapon is his attention to minute details of his clients’ appearance and behavior.

Astro’s methods bring to mind another fictional sleuth: Sherlock Holmes, the creation of Arthur Conan Doyle. The appearance of Doyle’s genre-defining detective launched what Crime Classics editor Leslie S. Klinger calls “a tsunami of Holmes imitators,” of which Astro is a notable representative. Like Holmes, Astro demonstrates a wealth of expertise in many fields, employs a specific meditating method to organize his thoughts and heavily relies on his companion, Valeska Wynne. Unlike Holmes, however, Astro trusts his sidekick with serious tasks and occasionally gives Valeska credit, though he never misses a chance to tease her.

Gelett Burgess, 1910. Photo: Unknown. Public domain from The Bancroft Library Portrait Collection.

Given Burgess’s background, such humor is not unexpected. Born in 1866 into a conservative Boston family, he was educated at the Massachusetts Institute for Technology before fleeing for the artistic freedoms of San Francisco. He worked as a draftsman for a railroad and taught technical drawing at the University of California, Berkeley. He resigned after apparently taking part in the silliness of knocking over a campus statue of a temperance leader. In 1895, he launched a humorous literary magazine, The Lark. The first issue featured Burgess’s famous nonsense verse, “The Purple Cow”:

I never saw a Purple Cow,

I never hope to see one;

But I can tell you, anyhow,

I’d rather see than be one.

Burgess also invented the Goops, quirky little creatures who exemplified ill-mannered children; he produced five books about them. Another literary bon mot: He coined the the term “blurb,” a short testimonial for book advertising. His papers are at the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley.

Burgess ventured into crime writing, producing more than 20 tales about Astro the Seer for the Associated Sunday Magazine between 1908 and 1909 under the pen name of Alan Braghampton. The series achieved success, but when in 1912 the Astro stories were produced in book form, titled “The Master of Mysteries,” Burgess published it anonymously.

These stories, consciously or not, played upon a key debate of the day: Were psychic powers a new frontier that humanity was just beginning to tap into, or were they so much stuff and nonsense?

While Astro used his mystical persona to disguise his shoe-leather detective work, his contemporary, the real-life magician Harry Houdini, not only rejected any claims that he possessed supernatural powers, but debunked fraudulent mediums and their ilk.

In 1927, through Houdini’s bequest, the Library received nearly 4,000 items from his personal library, forming the Harry Houdini Collection.

Another day at the office for Harry Houdini in 1906. Photo: Unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.

Houdini had become famous in the late 1890s as an escape artist, magician and stunt performer. In one of his stunts, he had himself bound into a straitjacket and suspended by his ankles from a tall structure, escaping in full view of fascinated onlookers. Proud of his craft, he readily revealed his methods.

As a professional tradesman, he ridiculed fellow magicians who professed special powers or psychic gifts. He loathed those who capitalized on the distressed and grief-stricken. In the 1920s, Houdini embarked on a mission to debunk psychics and put them out of business. He published books and articles, naming the charlatans and exposing their tricks. He testified before Congress in support of criminalizing fortune-telling for fees in the District of Columbia, and he sacrificed friendships for his cause (for example, with the aforementioned Arthur Conan Doyle, an ardent spiritualist).

Houdini (seated, left) exposes techniques used by fraudulent mediums on the stage of the New York Hippodrome. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

Houdini delivered his final piece of evidence posthumously. Bess, his wife, held annual séances for ten years after his death, attempting to contact him, waiting for a secret message they had agreed on before his death. No such message arrived, thereby confirming, anecdotally, that spirits could not communicate with the living.

A 1909 poster advertising Harry Houdini’s exposé performance. McManus-Young Collection, Prints & Photographs Division.

With “The Master of Mysteries,” the Library’s Crime Classics series continues its mission of bringing back to light some of the finest, albeit lesser-known, American crime writing from the 1860s to the 1960s. Drawn from the Library’s collections, each volume includes the original text, an introduction, author biography, notes, recommendations for further reading and suggested discussion questions from mystery expert Leslie S. Klinger.

Crime Classics are published by Poisoned Pen Press, an imprint of Sourcebooks, in association with the Library of Congress. “The Master of Mysteries,” published on January 3, is available in softcover ($14.99) from booksellers worldwide, including the Library of Congress shop.

January 3, 2023

My Job: Monica Varner in Rare Books

Monica Varner, taking some time off work. Photo courtesy of the subject.

Monica Varner is collections manager for the Rare Book and Special Collections Division.This article appeared in the Library’s Gazette.

Tell us about your background.

I grew up in Arlington, Virginia, and went to H-B Woodlawn Secondary Program (“Hippie High”) before heading down to Lynchburg, Virginia, to study art history at Randolph College. During college, I spent a year at Reading University in England.

On returning to the Washington, D.C., area, I enrolled in the museum studies master’s program at George Washington University. I interned at the National Museum of Women in the Arts and the Scottish Rite Temple in D.C., and I worked in various museum or library-adjacent jobs, including as a circulation manager at the public library system in Alexandria, Virginia.

My coursework and experiences in fine arts, archaeology and conservation, historic preservation, fashion history, exhibit design and collections management made working at the Library a natural fit — it’s all here.

What brought you to the Library, and what do you do?

I’ve wanted to work at the Library since I was very young. During an early, formative visit here with family, my aunt reports that I was furious that despite the Library reportedly having every book in the world, I, a small child, was not allowed to go into the stacks and start reading.

In 2018, I started with the Serial and Government Publications Division as a newspaper deck attendant and was introduced to the wild world of rare comic books, colonial newspapers and the mysteries of the overseas acquisition departments. I also used a microfilm reader for the first time.

The following year, I joined Rare Book and Special Collections, and I recently became collections manager for the division. I help organize and make room for incoming and outgoing special collections, monitor the environmental conditions of the stacks, answer reference questions and assist with special tours and displays of our material. Baby E would be thrilled to know I ended up here!

What are some of your standout projects?

I love helping plan themed displays using our material, such as a Disney Cinderella gala a couple years ago and a recent class on the history of structure in architecture.

I’ve also slowly been organizing the division’s materials in a size-based system to maximize our stack space and improve storage conditions for the books. I’ve stumbled upon some great finds in that process. As a large public institution, the Library has become the final resting place for books from all over the world and from all different types of owners.

It’s fascinating to make connections across our material — for example, to learn that two books once in the same medieval monastery but dispersed after its dissolution ended up here together again after hundreds of years.

And any time someone finds a mysterious signature or stamp in a book, I pop up behind the researcher’s chair in the reading room to do some detective work. I love researching the people who read and used the books in our collections, especially children’s doodles.

During COVID, the division started recording videos about our collections, and I’ve enjoyed showcasing particularly interesting items in that way. The Multimedia Group has done an amazing job helping translate our research into this recorded format in an engaging way.

What do you enjoy doing outside work?

I just finished an October horror movie marathon we do annually in my home, and I’m almost done knitting a complex sweater vest (that I may or may not actually wear). Some friends and I meet once in a while for “Bad Book Club,” where we read goofy contemporary suspense novels.

My partner is an architectural historian, so during the summer I join him in Italy and help document 13th-century construction techniques. We both grew up in or near D.C. and enjoy walking around downtown seeing old sights in new ways. My dad was an architect, and I love visiting the buildings he worked on.

I also enjoy taking weekend trips in the area, visiting my family in the Pacific Northwest and hitting up yard sales and thrift stores to stock my ever-expanding cabinet of curiosities.

What is something your co-workers may not know about you?

I have never been pulled over and never used a card catalog until I worked at the Library. I also play the cello (but am way out of practice).

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

December 27, 2022

The Soldier’s Letter: The Civil War from the Western Frontier

The Soldier’s Letter, issue No. 15. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Oliver V. Wallace was neither a great soldier of the Civil War nor an imposing man of his era. He was a private in the 2nd Colorado Cavalry and spent most of the conflict on the third floor of the Union Hotel in Kansas City.

Still, he found a place in history. It was from that perch that he created, edited and wrote much of the Soldier’s Letter, the unofficial newspaper of his regiment, that ran for 50 editions between 1864 and 1865. The four-page paper, printed on notebook-sized pulp, formed a loose diary of Union soldiers who were — although far removed from the war’s epic battles — “instrumental to the Civil War-fueled expansion of the American empire across the West,” writes military historian Christopher Rein in 2020’s “The Second Colorado Cavalry.”

The Library recently acquired a bound copy of the full print run of Wallace’s paper, an extremely rare find. It is a hardbound if unpretentious presentation copy, given to the regiment’s commander, James Hobart Ford, after the war as a memento. It is the size of a notebook, unlabeled, weathered, with the editions of the paper inside printed on pulp stock.

Though there is a long-standing national obsession with the Civil War, regimental newspapers never quite caught on as something to be preserved. More than 200 such papers in at least 32 states printed at least one edition, according to historian Earle Lutz, but they had mostly vanished by the time he surveyed the nation’s libraries, museums and major private collections in the early 1950s.

“A large number simply do not exist, and, in many, many instances, there is only one copy held anywhere,” he wrote in The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America in 1952. “It would be far easier to assemble a collection of the signers of the Declaration of Independence than to make up a collection of just one-half of the soldier publications that I have on my list.”

More recent scholarship has helped document the history of the military papers, and the national Library leaped at the chance to get the Soldier’s Letter from a dealer in rare manuscripts.

“I was struck by its uniqueness: a complete run of an American Civil War regimental newspaper and a specially collected set presented to the regimental commander,” said Georgia Higley, head of the Physical Collections Services in the Serial and Government Publications Division, who recommended the acquisition of the paper. “Researchers and Civil War enthusiasts value regimental newspapers for the honesty expressed by the men and their descriptions of life on the front lines — both at times at odds with mainstream newspapers.”

Three pages in each edition were devoted to a narrative history of the regiment, war news, local gossip, rumors and jokes. The fourth was left blank for soldiers to write letters or notes to family and then mail home. Each copy cost 10 cents. Much of the war was over by the time Wallace started his paper, but he and his unnamed correspondents did note Lincoln’s assassination, accounts of skirmishes and the general tenor of the last days of the Confederacy.

“The rebels have taken to smuggling in bacon past the blockage,” a short item noted in one edition near the end of the war. “The evidences multiply that they are on their last legs.”

There were asides about eligible women — some wrote in, looking for marriage — but Wallace admonished his peers not to date Confederate women. Charming as they were, he noted, they were traitors to the Union cause at best and spies at worst.

The Union cause was a particular focus for the regiment, as Colorado was a territory whose white citizens longed to join the United States. Wallace surveyed his peers and published the results, providing a clear snapshot of the regiment’s demographics: Nearly all of them rushed west after an 1859 gold strike in the Rocky Mountains, and nearly all were working as miners or farmers when they signed up. The unit was composed of men from nearly two dozen states (primarily Ohio, New York and Pennsylvania), with a smattering of European immigrants. A few had been born at sea.

They first fought slave-holding Texans to prevent them from expanding into New Mexico, then moved to Oklahoma and eventually Kansas and Missouri. They were primarily “guerilla hunters,” both of Confederate bushwhackers and Native Americans, and relegated to an “obscure theater of the war,” Rein writes.

The paper was devoutly against slavery, and a few times units fought alongside the freed Black slaves of the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry. The editorial columns repudiated Confederates and Copperheads (Northern sympathizers).

But as historians have noted, the regiment was part of the bridge between the Civil War and the Indian wars that followed, and there is little doubt that the soldiers identified Native Americans as their most hated enemy. This becomes clear in their reaction to the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado, one of the worst atrocities against Native Americans in U.S. history.

Throughout 1864, while most of the nation was focused on the Civil War, white settlers in Colorado were advancing rail and wagon-train lines through the lands of the Cheyenne and Arapaho, attempting to connect themselves more concretely to the United States.

Native American war parties attacked the settlers making those routes, killing and raiding as they went. Peace talks ensued and by late November, some 750 Native American non-combatants were camped outside a U.S. fort, waiting to turn themselves over for protection from the hostilities. It’s a remote spot in eastern Colorado, flat and featureless, about 175 miles southeast of Denver, not far from the Kansas state line.

On Nov. 29, 1864, without warning or provocation, units of the 1st Colorado Infantry and the 3rd Colorado Cavalry, led by Col. John Chivington, attacked them at dawn.

“Over the course of eight hours the American troops killed around 230 Cheyenne and Arapaho people composed mostly of women, children and the elderly,” the National Park Service writes in its official history of the place, now a National Historic Site. “During the afternoon and the following day, the soldiers wandered over the field committing atrocities on the dead.”

Capt. Silas Soule of the 1st Colorado vehemently protested plans for the attack, held his men out of the conflict and later testified against Chivington as a war criminal. “I tell you Ned it was hard to see little children on their knees have their brains beat out by men professing to be civilized,” he wrote to a friend weeks after the attack.

Soule was shot and killed in Denver less than a year later, an unsolved attack widely viewed as retribution for his testimony. Chivington escaped legal punishment but resigned from the military and was socially and politically ostracized.

Strikingly different from the rest of the nation’s reaction, the Soldier’s Letter editorialized the massacre wasn’t vicious enough to suit their taste.

“The only fault we have to find with Colonel Chivington and his troops is that they did not sweep the last ‘red skin’ in that part of the country, from the face of the earth! …. nothing short of annihilation will protect our brothers, sisters and parents, on the frontier, from their savage cruelties,” the paper wrote in January 1865 (original italics and punctuation).

It’s a stark paragraph or two, lost in a small sea of other type about quotidian details of camp life. More than a century and a half later, it’s a reminder that the Civil War was, on the Great Plains, only one of two conflicts that would define the nation.

The final edition of the Soldier’s Letter sums up its history. The top item at far right notes there were 20 copies of the full run of the paper on hand, all 50 editions. The Library’s copy is the only one known to still survive. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers