Library of Congress's Blog, page 19

November 10, 2023

World War II’s Navajo Code Talkers, In Their Own Words

This is a guest post by Nathan Cross, an archivist in the American Folklife Center. It also appears in slightly different form in the November-December issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Before radio communications could be encrypted through technological means, the U.S. military struggled to find fast and effective means to send secure messages. Perhaps the best method they found was to employ Native American troops as Code Talkers — radio operators who communicated to each other using their native languages. Native American languages were rarely written and almost entirely unknown to enemy nations on other continents. This meant even their casual onversations could not be understood or translated by the enemy, much less their messages being decoded.

Code Talkers from 14 different Native American nations served in World War I and World War II, including over 400 Navajo Marines during World War II. After the war, the Japanese chief of intelligence acknowledged they never broke the Navajo code. The original 29 Najavo Marine Code Talkers were awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 2001. The Veterans History Project maintains oral history interviews from more than 20 Navajo Code Talkers.

In their interviews, the troops speak of the lifelong adversity they had faced. Growing up in an era of forced assimilation, most attended boarding schools that forbade them from speaking in Navajo. The irony of later being asked to use this language at war was not lost on them.

“Now my mind went back to the past — first they told me not to speak Navajo, but now they want me to speak Navajo in combat,” recalled Teddy Draper, who served with the Marines on Iwo Jima.

In addition to being a fascinating chapter of military history, the Code Talkers’ unique experiences have much to teach us about the human dimensions of war. They faced almost continuous combat. Due to high demand for their services, the Code Talkers frequently were sent directly from one battlefield to another instead of rotating to the rear with their units. Many are open and honest about the stress combat placed on them and how that affected them after the war.

Upon coming home, some participated in traditional Navajo ceremonies that provided healing and reintegration and often speak highly of these ceremonies’ effectiveness. All of them offer valuable insights into the importance for veterans of finding community and purpose after their service ends.

These accounts of their life experiences can be accessed through the online research guide, “Navajo Code Talkers: A Guide to First-Person Narratives in the Veterans History Project.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

November 7, 2023

Eavesdropping on Ernest Hemingway at Finca Vigía

In the middle of the 20th century, when Ernest Hemingway was living in Cuba, his friend and future biographer A.E. Hotchner got the man to record himself on a wire recorder — the precursor of the tape recorder — so that one of the world’s most celebrated personalities could pop off about anything he’d like whenever he’d like.

The idea was to capture the sound and feel of Hemingway himself, unguarded and spontaneous, joyful and opinionated, comfortable in his own home, a part of him not on public display.

These off-the-cuff recordings, then, would give Hotchner hours of raw material from one of greatest literary minds in American history. Who, after all, would not think it an unforgettable experience to have plopped on Papa’s couch, listening to the man go off about war, writing, bullfights or fishing the Gulf Stream?

The closest you can get to that today is sitting in a soundproof booth at the Library, headphones clamped over your ears. Those 1949-50 tapes, initially recorded on 15 wire reels and lasting about 41/2 hours, are preserved in digital form as part of the Hotchner Collection. (They are not online and require an in-person appointment at the Library. There are other recordings of Hemingway, most notably at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. )

The front entrance to Hemingway’s home in Cuba, Finca Vigía (“Lookout Farm”). It’s now a state-run museum, just outside Havana. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith, Prints and Photographs Division.

The front entrance to Hemingway’s home in Cuba, Finca Vigía (“Lookout Farm”). It’s now a state-run museum, just outside Havana. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith, Prints and Photographs Division.The recording quality is low and scratchy, but you can listen as Hemingway reads a poem about World War II, part of a play he wrote, gripes about criticism of his recent work, dictates letters and book introductions, and offers salty recollections of working as a bouncer in a bordello. There’s also small talk among friends, live music and singing.

The last scenario is the case one afternoon in which things went (briefly) just at Hotchner must have hoped. The recorder was running in one of the open areas of the house, likely the living or dining room. There was a male voice singing an operatic tune in Spanish, one or two people clapping at the end, and then Hemingway speaking into the mic.

“Here, here we are at, ah, Papa’s this afternoon, with most of the old familiar gang around,” he says, a little stilted. He then lists his pals: Roberta Herrera, Sinsky Dunabeitia, Father Don Andres. The guests were Spaniards who had decamped to Cuba. Herrera, a doctor, and Andres, a Catholic priest, had both fought on the losing side of the Spanish Civil War. Dunabeitia wa a “salty, roaring, boozing, fun-loving Basque sea captain,” as Hotchner later described him.

Mary Hemingway, the writer’s fourth wife, was also there. The chatter was about an upcoming fishing tournament in which Hemingway hoped he might win some money for a hunting club in Idaho, where the couple also had a place.

“We’re thinking mostly today of preparation for the, for the coming tournament, in which Mary and I are teamed and are going to fish for the Ketchum Rod and Gun Club.” He laughs, a rapid ha-ha-ha. “We hope — Mary has been training this morning, she said made about five laps in the swimming pool, in getting herself in shape for it. I took a long walk into the back country and feel fit. We’re looking forward to this thing and I hope it’ll be a success.”

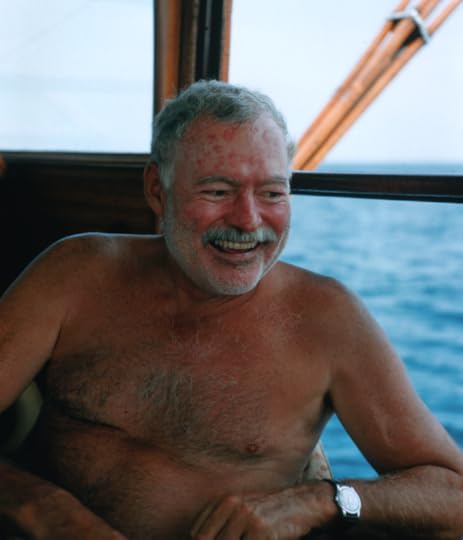

Hemingway aboard the Pilar in June 1956. Photo: Earl Theisen, Look Magazine. Prints and Photographs Division.

Hemingway aboard the Pilar in June 1956. Photo: Earl Theisen, Look Magazine. Prints and Photographs Division.He’s clearly trying to have a good time, but the fun seems a little forced. His cadence is awkward, slowing and then accelerating for a burst of a few of a years words. And instead of the baritone, barroom bravado that one might expect from such a big man (his voice was high and uneven, with a hint of his Midwestern roots), what we really hear is how self-conscious he was with a microphone in front of him.

“It seems I’m doing very badly at this now,” he says at another point, likely in 1949 when he was working on “Across the River and Into the Trees,” “but I wrote 1,260 words this morning and am not overly enthusiastic at the moment about talking into something that feels as dead in the hand as this does.”

Hotchner, writing in “Papa Hemingway,” a biography published in 1966, noted that this discomfort extended to telephone calls. “Ernest advanced upon a telephone with dark suspicion, virtually stalking it from behind. He picked it up gingerly and placed it to his ear as if to determine whether something inside was ticking. When he spoke into it his voice became constricted and the rhythm of his speech changed, the way an American’s speech changes when he talks with a foreigner.”

Paul Hendrickson, the author and journalist, spent years working on “Hemingway’s Boat: Everything He Loved in Life, and Lost, 1934-1961,” published to critical acclaim in 2011. He was also struck by the odd delivery: “Years ago, starting out on this book, I used to go into small soundproof booth at the Library of Congress and listen to Ernest Hemingway’s voice on old wire recordings,” he wrote. A few lines later: “…he was said to be very tentative with it at first, and I can picture him holding the mic like a man holding something that’s about to bite. Six decades later, I could go into a room and hear the disembodied self of Ernest Hemingway spookily speaking in my ear in a thin, precise, high-timbered pitch.”

He notes that others don’t recall Hemingway sounding quite like that, and Hemingway, after playing back another segment, didn’t think it sounded like himself at all: “Ed, I just listened back to that voice, and it could not be more horrible.”

There are a few casual moments in the tapes, but he still sounds like he’s reading a script someone just handed him: “Here, Mary is lovely and we work every day and the animals are still eating. Gregorio has the boat on the waves and is painting her for the marlin season. I am jamming, trying to get work done so that I can fish.”

Hemingway’s house featured an open floor plan

that he used to accommodate his frequent guests. It has not been changed since he left. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.

Hemingway’s house featured an open floor plan

that he used to accommodate his frequent guests. It has not been changed since he left. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.Hemingway was as famous at that point for his larger-than-life persona as he was for his novels, short stories and nonfiction. He was arguably the most famous author on the planet. He would win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for “The Old Man and the Sea” in 1953 and the Nobel Prize in Literature the following year.

It was also in 1954 that he suffered the final of several major concussions he had absorbed over the years (as many as nine), this time in two plane crashes in a remote part of modern-day Uganda. Further, the Hemingway family suffered from genetic mental disorders, including severe depression and bipolar disorder. His father, sister and brother all committed suicide as he did; later in life, facing serious health issues. His youngest son, Gregory, who eventually underwent gender reassignment surgery and was also known as Gloria, suffered from bipolar disorder and died in a holding cell in a Miami jail. His famous granddaughter, the model and actress Margaux Hemingway, suffered from severe depression and committed suicide at age 42.

For Hemingway himself, the combination of genetics, brain injuries, aging and alcohol further degraded his mental abilities until he committed suicide in 1961, a few weeks short of his 62nd birthday.

So these recordings in 1949 and 1950 give us a poignant window into some of his last good years. There are moments of startling clarity. He dictates a touching letter to Gregory, a father in anguish. Another time, frustrated with the whole recording project, he snaps at the impossibility of what Hotchner has asked him to do, at the paradox of being a novelist asked to explain his art: “It’s hard enough to write a damned story without talking about it and maybe it would be better to write and not talk at all, period.”

Hemingway often wrote just this way at Finca Vigía: standing at his bedroom bookcase, pecking away at a typewriter. One of his dogs sleeps just behind him. Photo: Earl Theisen, Look Magazine. Prints and Photographs Division.

Hemingway often wrote just this way at Finca Vigía: standing at his bedroom bookcase, pecking away at a typewriter. One of his dogs sleeps just behind him. Photo: Earl Theisen, Look Magazine. Prints and Photographs Division.Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

November 2, 2023

The Wright Brothers History Takes Wing at the Library

This article will appear in the November-December 2023 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

You know this story. Or at least the story in the famous “First Flight” picture above.

It goes like this: At 10:35 on the morning of Dec. 17, 1903, on a remote sand dune in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, mankind flew for the first time. Orville Wright piloted a homemade airplane powered by a homemade engine for a few wobbly seconds while his brother and co-creator Wilbur ran alongside the right wingtip.

“Success four flights thursday morning” Orville telegraphed their father back home in Dayton, Ohio.

The world would never be the same. Humans flew to the moon 65 years later. We live in a different universe. Et cetera.

But here’s the more complicated story, one that becomes clear by looking through the Wright brothers remarkable collection in the Library.

“Flight” was such a tricky term at the time that the Wright brother’s achievement was barely noticed, much less celebrated. Germany’s Otto Lilienthal had become internationally famous as the “flying man” in the early 1890s for making the first heavier-than-air flights in a glider. After that, so many “fliers” from so many countries made so different claims of incremental gains in the field that the public tired of the spectacle.

So that December, about the only notice paid to one of mankind’s greatest achievements — the first heavier-than-air powered flight — was a largely incorrect wire-service story that ran in several papers around the country. It was treated as an unverified curiosity. Typical of the coverage, the St. Paul Globe put the three-paragraph report at the bottom of page four under the headline “This Flying Machine Actually Flies.”

Even the Wright brother’s father, Milton, recipient of one of the most momentous telegrams in world history, didn’t exactly run screaming into the streets.

The historic telegram that relayed the news of the first flight. Prints and Photographs Division.

The historic telegram that relayed the news of the first flight. Prints and Photographs Division.“Well, they’ve made a flight,” he told the family cook, after scanning the telegram she handed him. Dinner was slightly delayed.

It was not until Aug. 8, 1908 — more than 4½ years after the Kitty Hawk breakthrough — that the world finally sat bolt upright. In Le Mans, France, in front of a skeptical crowd, Wilbur flew two circles above a racetrack at a blazing 60 mph. He turned, he swooped, he went up, he went down and he coasted back to a stop on the ground just so. The crowd went bananas.

“WRIGHT FLIES EASILY,” read the front-page headline in the Washington Sunday Star in the nation’s capital the next day as news shot around the globe. “WRIGHT’S AIRSHIP IN RAPID FLIGHT,” The New York Times reported, also at the top of the front page, adding “Wildly Cheering Spectators” loved the spectacle.

Only then did the Wright brothers become the historical entities, the fathers of flight, the icons of the age, that we know today.

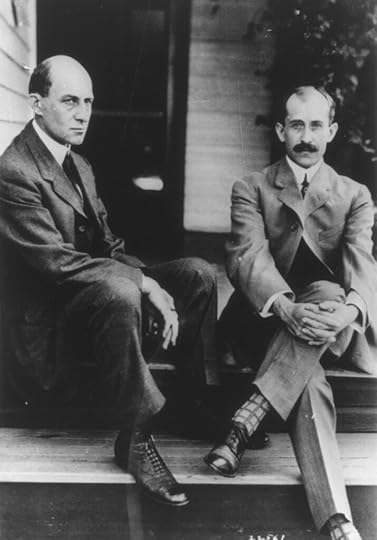

Wilbur (left) and Orville Wright in 1909, a year after their Paris flights made them world famous. Photo unknown. Prints and Photgraphs Division.

Wilbur (left) and Orville Wright in 1909, a year after their Paris flights made them world famous. Photo unknown. Prints and Photgraphs Division.Their collection in the Library is a rare combination of significance, detail and candor. It spreads over 31,000 items that fill more than 130 boxes, extending for 61 feet of shelf space. There are also more than 300 glass-print negatives. There are copious personal letters from family members, diaries, scrapbooks, engineering sketches and financial records. You can chart the family’s entire odyssey here, from small-town Midwestern simplicity to worldwide fame, from youthful newspaper publishers to bicycle shop owners to builders of the world’s first airplanes.

“Rare is the collection that provides so much depth and range, and all in such detail,” wrote David McCullough, the two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning author and historian, after using the papers in researching “The Wright Brothers,” his No. 1 New York Times bestseller. “In a day and age when, unfortunately, so few write letters or keep a diary any longer, the Wright Papers stand as a striking reminder of a time when that was not the way and of the immense value such writings can have in bringing history to life.”

The papers show that the family was always extremely close knit. Milton and Susan Wright had seven children, five of whom survived infancy. Milton rose to the post of bishop in the Church of the United Brethren in Christ, a Protestant group that was strongly abolitionist and ardently opposed to alcohol. Susan, an accomplished student in college and also devoutly Christian, kept the family together while her husband traveled. (She died of tuberculosis in 1889, cared for by Wilbur for the last three years of her life in which she was largely bed-ridden.)

Wilbur and Orville were the third and sixth born. Here are a few lines from the earliest written missive that survives from one of them, a postcard from the adventurous Orville to his father in 1881, when he was 9 years old:

“Dear Father …. My teacher said I was a good boy to day. We have 45 in our room. The other day I took a machine can and filled it with water then I put it on the stove I waited a little while and the water came squirting out of the top about a foot.”

Later, on the eve of their first glider test flights, Wilbur wrote to their father from the Hotel Arlington in Elizabeth City, North Carolina, on Sept. 9, 1900. He was waiting for a boat to take him to a remote barrier island with steady winds and soft sand dunes called Kitty Hawk.

The Wright brothers’ shack at Kitty Hawk in 1901 was spartan. Photo: Unknkown. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Wright brothers’ shack at Kitty Hawk in 1901 was spartan. Photo: Unknkown. Prints and Photographs Division.“I have no intention of risking injury to any great extent, and have no expectation of being hurt. I will be careful, and will not attempt new experiments in dangerous situations. I think the danger much less than in most athletic games. I will write you again soon. Affectionately your son Wilbur.”

The striking thing here is that Wilbur wrote this “I’ll be careful, Dad” letter not as a teen, but as a 33-year-old man and successful business owner of the Wright Cycle Company, he and Orville’s bicycle business. It’s the kind of intimate communication that underscores that both brothers still lived at home with their widowed father at the time and that neither ever married.

These were not men given to poetic statements. Neither formally graduated from high school. They were no-nonsense Midwestern fellows, average-looking, determined, deliberate, frugal, practical, energetic, conservative, quiet, resourceful.

They had been fascinated with the idea of flight since their father bought them a toy “helicopter” when they were children. Later, Lilienthal’s glider flights intrigued them. His death from a crash in 1896 while pursuing the mysteries of flight galvanized them, Orville later said. They approached the problem of flight as engineers. They invested their time in computations and angles and wind speeds and physics and testing and welding iron and the sheer physical courage required to test their contraption in the air.

The overall effect was striking.

Hart O. Berg, their European business representative, wrote in May 1907 that he had recognized Wilbur Wright on first sight at a London train station though he’d never seen his photograph nor heard him described.

“…. either I am a Sherlock Holmes,” Berg wrote, “or Wright has that peculiar glint of genius in his eye which left no doubt in my mind as to who he was.”

Their sister, Katharine, also became something of a celebrity, particularly after joining her brothers in Europe after they had become a sensation. She even went flying in February 1909: “Yesterday afternoon, Will took Madame de Lambert for a five minute ride and me for a seven minute one,” she wrote her father. ‘Them is fine!’ It was cold but I was not particularly uncomfortable.”

Orville, flying away from the camera, over Huffman Prairie on October 4, 1905. Photo unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.

Orville, flying away from the camera, over Huffman Prairie on October 4, 1905. Photo unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.Another surprise made clear in their papers is how short their glory days in the air actually were.

They were not widely lauded until 1908. Wilbur died of typhoid fever four years later at age 45. Within half a dozen years of Wilbur’s death, Orville stopped flying, sold the Wright Company and set up a research business, the Wright Aeronautical Laboratory. It was a modest one-story brick building on North Broadway in Dayton. It was his office, six days a week, for three decades. He largely retreated from public speaking and the limelight, save for politely turning up when monuments or tributes to he and his brother were unveiled. He was unfailingly regarded as a gentleman.

He died in 1948 at the age of 76. He was buried in Woodland Cemetery in Dayton along with Wilbur, Katharine and their parents. He and Wilbur had seemed at peace with their legacy during their lifetimes — they had given mankind flight and reaped fame and financial rewards, and that was certainly enough for a couple of bachelor brothers living in the vast ocean of the middle continent, deep among the prairies and trees and small towns and rivers and lakes and bustling cities that would come to be called, in part thanks to their own invention, “flyover America.”

The brothers Wright would, no doubt, find that ironic.

In 1915, not long after Wilbur’s death, Orville Wright (left, standing) posed on the porch of his mansion with family and friends. His hand is on the chairs supporting his sister Katharine and his father Bishop Milton Wright. Photo unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.

In 1915, not long after Wilbur’s death, Orville Wright (left, standing) posed on the porch of his mansion with family and friends. His hand is on the chairs supporting his sister Katharine and his father Bishop Milton Wright. Photo unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

November 1, 2023

The First Children’s Picture Book Might Be This One

Back to school in 17th-century America meant going back to cramped one-room schoolhouses where children were taught Latin, reading, writing and math, peppered with a heavy dose of religious instruction.

If you could afford to send your children to school, “Orbis Sensualium Pictus” — considered the first children’s picture book — or a textbook based on it would have been used to help children become “wise” and learn work skills.

Often translated into English as “Visible World in Pictures,” the book was published in 1658 by Johann Amos Comenius. Born in northern Moravia (in present-day Czech republic), Comenius was a theologian and education reformer who believed in experiential, lifelong learning and in teaching children from a Christian perspective. The book intertwined education and religion in the aftermath of Europe’s brutal Thirty Years’ War.

Designed for school-aged children, Comenius’ book was first printed in Latin and German and later translated into other languages throughout Europe. Combining text, 150 woodcut illustrations and parallel columns in Latin and a local language, this extraordinary book featured myriad subjects ranging from nature to animal husbandry, science, music, cooking, the human soul and biblical references.

The popularity of Orbis extended for more than 200 years; it continued to be used into the early 19th century and helped spawn other children’s illustrated books. The earliest edition in English was published in 1659. In 2012, the Library acquired a 1664 version printed in London.

Another children’s book published a century earlier may have been the precursor to Orbis but never gained widespread acceptance. It’s the last of a three-volume set titled De re Vestiaria, Vascularia & Nauali, or “about clothing, vessels and boats,” by Lazare de Baïf. The Library holds the 1553 printing of the volume on boats and navigation, which is illustrated with eight woodcuts.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

October 31, 2023

José Guadalupe Posada’s Lively Calaveras and Enduring Legacy

The late Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison once famously said, “All good art is political! There is none that isn’t.” While the novelist never crossed paths with Mexican printmaker and lithographer José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913), her words aptly capture the essence of his work during a time of great social and political upheaval in Mexico, especially his calaveras or depictions of skeletons.

Posada’s striking illustrations graced the covers of books, newspapers, magazines, flyers, posters and commercial ads. His legacy inspired artists in the Chicano movement in the 1970s and continues to influence artists in the U.S., Mexico and beyond as they seek to address political and social issues through various art forms.

The Library of Congress boasts one of the most extensive collections of Posada’s work in the United States, providing a valuable resource for understanding Mexican culture. This treasure trove of prints, housed within the Library’s Prints and Photographs Division, originated from a generous gift and bequest from Caroline and Erwin Swann, a private collector who acquired a significant cache of Posada zinc blocks and broadsides during their travels in Mexico in the 1970s.

Posada helped popularize the calavera as a satirical graphic motif, often printed with rhyming ballads or corridos. The Aguascalientes engraver created tens of thousands of illustrated broadsides and flyers brimming with biting political humor, frequently targeting historical figures and political candidates. The vivid visual content ensured that the message could reach the Mexican masses, even those who were illiterate. The songs accompanying his images became part of an oral tradition, imparting morals, customs and political commentary.

Sara W. Duke, a librarian in the Prints and Photographs Division, characterized some of these broadsides as “ephemeral,” selling for mere pennies. They resembled the supermarket tabloids of their time, covering topics like suicide and true crime.

“They were fascinating. He was really publishing quickly,” said Duke. “Some of the poetry (from these broadsides) has come down through the generations as songs, and people in Mexico and Texas still sung them in the 2000s.”

One of his most famous creations, a broadside titled “Calaveras del montón, número 1,” is featured prominently on a vibrant community altar assembled by the Library’s Hispanic Reading Room as part of the “Día de los Muertos,” an annual celebration throughout Mexico and the rest of Latin America to honor and remember deceased loved ones. The Library owns the zinc block Posada used for the image, a blend of photo etching and hand engraving.

The zinc block original to “La Calavera Oaxaqueña” by José Guadalupe Posada. (Courtney Pomeroy/Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

The zinc block original to “La Calavera Oaxaqueña” by José Guadalupe Posada. (Courtney Pomeroy/Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

The print on pink ground wood paper, also known as “La Calavera Oaxaqueña,” features one of Posada’s most striking portrayals of skeletons in motion. It depicts a menacing, machete-wielding calavera surrounded by skeletons. Dressed in a charro outfit, this angry-looking male skeleton is shown clenching his fists while producing, as the title suggests, fresh new heaps of calaveras. Skulls lie at his feet, creating a whirlwind of truly morbid action.

Posada created festive representations of death, and as noted by critics, his skeletons became his undeniable contribution to art. Calavera images inspired by Posada’s oeuvre are now used to decorate altars on November 1 and 2 (the Roman Catholic celebrations for All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day, respectively).

Katherine Blood, a librarian in the Prints and Photographs Division, notes that Posada was not the first to use calaveras in the Mexican popular press. Also, the motif of death had been depicted in artists’ images dating back to the Middle Ages, “featuring animated skeletons that underscore the idea of death as the great equalizer—that we all share our mortality, regardless of rank or merit.”

However, “Posada popularized them as a national symbol (in Mexico) and is deeply-associated with them today. There are many American artists in our collection and wider world whose work is influenced by Posada, including Ester Hernández, Juan Fuentes, Enrique Chagoya and numerous others,” added Blood.

A prolific artist during turbulent times in Mexico, Posada—or “don Lupe” as his friends and collaborators affectionately called him,—often used his calavera creations to lampoon the upper class, bourgeois life and the corruption of the political elite. The skulls, such as his iconic “La Calavera Catrina,” remind us that death is a universal experience that comes to us all, rich or poor.

October 23, 2023

Hans Christian Andersen’s Wild Scrapbooks

In his fairy tales, Hans Christian Andersen created worlds of imagination and full of heart: A lovestruck mermaid seeks an eternal soul, a foolish emperor parades around in invisible clothes, an outcast duckling searches for a welcoming family.

Besides authoring timeless stories such as “The Little Mermaid,” “The Emperor’s New Clothes” and “The Ugly Duckling,” Andersen occasionally created special scrapbooks as gifts for children of a few lucky acquaintances.

The Library holds one of them in its collections, assembled by Andersen and good friend Adolph Drewsen in 1862 for Drewsen’s 8-year-old grandson, Jonas.

Andersen and Drewsen filled the scrapbook (or “billedbog,” Danish for picture book) with images chosen from American, English, German and French periodicals and books. They cut out pictures, hand-colored them and glued them into the book. Andersen wrote poems or rhymes for 19 of them.

Over 140 pages, Andersen showed a world of adventure and fantasy. Soldiers fought battles in faraway places, explorers traversed the unknown. Around them moved a menagerie of walking, flying, swimming, slithering creatures.

Between a snake, a crocodile and figures of a man and a woman, Andersen inscribed a verse: “He is not afraid of/ the big snake/ and has come so close/ that the hair on his head is standing up straight/ He is engaged/ You will notice his sweetheart/ standing near the snake’s tail/ Her skirt is blue; the maiden has poise/ She glances at the snake and the crocodile/ and says: “Little ones, please lie still.”

The scrapbook is part of a collection of first editions, manuscripts, letters and presentation copies gathered over a 30-year span by Danish actor Jean Hersholt — probably the most comprehensive collection of Andersen material in America. Hersholt donated it to the Library in the 1950s.

Today, some 160 years after he put scissors, glue and pen to paper, this billedbog demonstrates in different way Andersen’s unsurpassed talent for appealing to young imaginations.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

October 19, 2023

New! “The ‘Canary’ Murder Case” from Library’s Crime Classics Series

This is a guest post by Allen Nguyen, a Widening the Path intern in the Library’s Publishing Office .

Ambitious and daring showgirl Margaret O’Dell, nicknamed the “Canary,” has earned the ire of multiple men. When she is found murdered in her apartment, the blame quickly falls on the men entangled in her aspirations; all were near her home on the night of her death. But the apartment is securely locked when the body is found the next day. The police are baffled.

Such is the setup of the “The ‘Canary’ Murder Case” by S. S. Van Dine, the latest in the Library’s Crime Classics series. Originally published in 1927, the novel follows Philo Vance, a man of high intuition and powerful psychological analysis, as he discovers the culprit behind this locked-room mystery. He observes not just the facts, but also the minds of the suspects, delving into the realm of psychology. He dissects their personalities and behaviors, and, in the climax of the novel, analyzes how they play their cards when under the watchful eyes of the law, deducing who among them could have the wits — and bravado — to pull off this seemingly impossible murder.

S. S. Van Dine, 1936. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection. Prints and Photographs Division.

S. S. Van Dine, 1936. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection. Prints and Photographs Division.S. S. Van Dine — a pen name for Willard Huntington Wright — not only serves as the author but is also the narrator and assistant to the sleuth. Wright, born in 1888 in Virginia, began his writing career as a literary editor for the Los Angeles Times, eventually becoming an influential art critic. Facing financial instabilities, in the mid-1920s he turned to writing detective fiction and assumed the name of S. S. Van Dine, penning a dozen novels featuring Philo Vance. The majority of these novels became bestsellers, alleviating Wright of his financial troubles.

Published during the golden age of detective fiction, “Canary” was the second book in this eventual 12-volume series. As Kirkus wrote in their review of our Crime Classics reissue, the novel is an “undeniable landmark in the history of the genre.” Philo Vance’s popularity placed him alongside other great sleuths of the time, such as Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot and Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe. Like them, Philo Vance appeared in multiple film adaptations.

Just two years after the publication of “Canary,” it received a film adaptation in 1929 starring William Powell as Philo Vance and Louise Brooks as Margaret O’Dell. But it came at a difficult moment in film history — the switch from silent to sound films, or “talkies.” The first was the landmark Al Jolson film, “The Jazz Singer,” in 1927. Silent films then in production scrambled to add sound, which required scenes to be reshot; that was the situation for “Canary.”

But after Paramount reneged on a salary increase promised in Brooks’ contract, she refused to reshoot her scenes.

Louise Brooks in a publicity shot from the early 1920s. Bain News Service. Prints and Photographs Division.

Louise Brooks in a publicity shot from the early 1920s. Bain News Service. Prints and Photographs Division.Contract disputes between actors and their studios were common in this period. Hollywood saw the transition to talkies as “a splendid opportunity … for breaking contracts, cutting salaries, and taming the stars,” as Brooks put it.

This frustration had been years in the making. Several of the biggest stars of the day had banded together in 1919 to create their own production company, United Artists. At the helm were renowned Hollywood figures D. W. Griffith, Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks. (The National Audiovisual Conservation Center at the Library houses a wealth of resources on this significant era of film.)

(L-R, front row) D. W. Griffith, Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks establishing United Artists, 1919. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection. Prints and Photographs Division.

(L-R, front row) D. W. Griffith, Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks establishing United Artists, 1919. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection. Prints and Photographs Division.Fast forward a decade later to talkies. Brooks’ efforts were not successful. Paramount planted a lie in the papers about her voice being unusable for talkies, irreversibly damaging her reputation in the new era of sound films, and hired actress Margaret Livingston to voice over Brooks’ original scenes. Despite critics panning the overdubbing, the film was fairly successful, and the series — both books and film — continued to be popular. Eventually 17 Philo Vance films would grace the silver screen, leading the American Film Institute to nominate Vance to their list of “100 Years … 100 Heroes & Villains” in 2003.

Van Dine contributed significantly to the detective fiction genre, and “The ‘Canary’ Murder Case” stands out as one of his most popular works. This most recent publication of the Library’s Crime Classics series will give readers a taste of Philo Vance as they seek the truth alongside this inimitable detective.

Library of Congress Crime Classics are published by Poisoned Pen Press, an imprint of Sourcebooks, in association with the Library. Each volume includes the original text, an introduction, author biography, notes, recommendations for further reading and suggested discussion questions from mystery expert Leslie S. Klinger. “The ‘Canary’ Murder Case” is available in softcover ($14.99) from booksellers worldwide, including the Library of Congress shop.

October 17, 2023

Primary Documents: The Library’s Amazing Resource for Teachers

This is a guest post by Lee Ann Potter, the Library’s director of educational outreach.

Lisa Suders hears a familiar refrain from her students as they begin history lessons about child labor: We’d rather be out making money at a job than sitting in class.

“There is always a chorus of students who say they would rather be working than be in school,” says Suders, who teaches eighth-grade social studies in Northville, New York.

Their interest in work, however, offers a teachable moment: Suders draws on primary resources from the Library to show students what work historically has meant for children.

She and her students examined photographs taken by sociologist Lewis Hine and read a report he wrote for the National Child Labor Committee in 1909, titled “Child Labor in the Canning Industry of Maryland.”

For young people today, Hine’s report and photos are eye-openers.

A boy working in a low tunnel more than a mile inside the Turkey Knob Mine in Macdonald, West Virginia, in 1908. Photo: Lewis Hine. Prints and Photographs Division.

A boy working in a low tunnel more than a mile inside the Turkey Knob Mine in Macdonald, West Virginia, in 1908. Photo: Lewis Hine. Prints and Photographs Division.He describes shocking conditions in workplaces that employ very young children. “Little tots” worked long hours around dangerous machinery, with no safety precautions. During the winter, many of them went south with their families to shuck oysters. In one family, children aged 3, 6, 8 and 9 all worked, and all but the youngest worked long, hard hours. “They were routed out of their beds by the boss at 3 a.m. and worked until about 4 p.m.,” Hine reported.

Suders’ students worked in pairs to answer questions about the report, analyzed Hine’s photos of the children at work and participated in a class discussion. The lesson, Suders says, “definitely took away the ‘glamour’ of making money as a kid instead of ‘just sitting in school,’ ” and her students showed genuine wonder about what life might have been like for those children.

What Suders and her students experienced was the power of primary sources — original documents, photos and accounts of history from people who had a direct connection to it. Primary sources generate enthusiasm for learning by helping students make personal connections with the past and its participants.

Since 2006, the Library’s Teaching with Primary Sources program has been empowering educators like Suders to make use of the Library’s digitized collections in ways that are valuable to them and their students.

The program does this by offering professional learning opportunities such as workshops, webinars, institutes and fellowships; developing teaching resources, including the Teachers Page and the Teaching with the Library of Congress blog; extending TPS grants to schools, libraries, universities, museums and associations; and supporting the TPS Consortium, a network of hundreds of partners across the country.

Every year, the program engages thousands of teachers, who reach millions of learners. At the core of the program are the Library’s collections. Across the curriculum, across the grade spectrum and across the country, Library collections serve as teaching tools that capture students’ attention, foster inquiry and promote problem solving skills.

“This has been transformational,” says Jeff Farr, a teacher of at-risk students in an alternative education environment. “Students that previously acted out so that they could leave the classroom are now coming in and actively participating. Wish I could bottle this …”

Farr had witnessed a significant change in student engagement when he taught a unit about Japanese American internment during World War II, using primary sources from the Library’s collections.

One photograph in particular captured the attention of, and surfaced empathy from, his students — most of whom have been unsuccessful in traditional classroom settings and come to his school under burden of expulsion, reassignment, pending judicial action and/or as a transition from a detention facility.

The photograph (at top of this post), taken by Farm Security Administration photographer Russell Lee featured a Japanese American child — bundled in an overcoat, a tag hanging off the coat — preparing to be evacuated from the West Coast with his parents in April 1942.

Other FSA photographs inspired teachers and students in Peñasco, New Mexico. In fact, the nearly 500 images of people, structures and activities taken in their small town during the early 1940s by Lee and John Collier have played a major role in the Peñasco Independent School District’s efforts to design and implement a K-12 curriculum to teach the history of New Mexico, of the Peñasco area and of Picuris Pueblo, a historic pueblo just south of Taos.

Father Cassidy, a local priest, speaking at the dedication of the new health clinic operated by the Taos County cooperative in Peñasco, New Mexico, in 1943. Photo: John Collier. Prints and Photographs Divsion.

Father Cassidy, a local priest, speaking at the dedication of the new health clinic operated by the Taos County cooperative in Peñasco, New Mexico, in 1943. Photo: John Collier. Prints and Photographs Divsion.But the power of the photographs extends beyond the curriculum. The photos have encouraged intergenerational communication and relationship building — students are learning from elders about the people and places featured. These conversations and student interest in the portraits of community members taken decades ago led to an unexpected after-school program where students, primarily from Picuris, have been taking portraits of their peers and families. This program prompted another unexpected outcome.

“To support their photography,” Michael Noll of the Peñasco ISD says, “we were able to connect with the son of photographer John Collier, who returned unpublished photos, taken at Picuris, from a personal collection to the Pueblo.”

Haley Rooney, a middle school teacher in Michigan, also was drawn to photographs taken by Lee and others as she was developing a lesson for her Introduction to Spanish class focused on combating stereotypes about where Spanish is spoken around the world. For the activity, she identified dozens of images in Library collections that included Spanish words and encouraged her sixth-graders to analyze and annotate them to determine where they were taken.

“My students were incredibly engaged in this activity,” Rooney says. “There were many great discussions about what clues they could see in the photos that backed up what they thought. After we discussed all of the photos and they had looked at all of them so deeply through the primary source analysis, our conversations regarding the use of Spanish were much more informed.”

Prompting wonder about another place and time, and the experiences of those who came before is something primary sources do exceptionally well for students of every age.

Ilene Berson and Michael Berson are professors at the University of South Florida who are co-directing a Teaching with Primary Sources grant project that involves a number of partnering organizations, including the University of South Florida College of Education, the Tampa Bay History Center, the Florida Office of Early Learning and the three Tampa Bay Early Learning Coalitions.

Their project focuses on infusing primary sources into early childhood instruction to foster emergent visual literacy and historical inquiry with young children. In the first phase of their project, while identifying community-based primary sources that are appropriate for preschoolers, they developed a supplemental resource for educators called “Tampa Bay ABCs.” Similar to flashcards, each letter of the alphabet is represented by a word, illustrated by a primary source related to Tampa Bay. For example, P is for pirate, illustrated with a stereograph image from 1926 of the pirate ship Gasparilla in the bay.

“By engaging with primary sources, children are able to explore complex topics and develop a deeper understanding of historical and cultural contexts,” the Bersons report. “This has also helped to foster empathy, tolerance and respect for diversity, as children are exposed to a range of perspectives and experiences.”

Furthermore, their observations suggest that the “implementation of research-informed strategies that infuse primary sources into early childhood instruction can have a transformative impact on the learning experiences and outcomes of young children.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

October 13, 2023

Louise Glück, Nobel Prize Winner, Former U.S. Poet Laureate, Dies at 80

Louise Glück, the poet whose often personal, always searching work won the Nobel Prize in 2020 and who served as the U.S. poet laureate for the Library in 2003-2004, has died at the age of 80. The cause was cancer, and she passed away at her home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the New York Times reported.

It was a notable passing in American letters, as Glück won almost every poetry award in the canon — the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, the National Book Critics Circle Award, the National Humanities Medal — during a career that established her as one of the nation’s greatest writers of the past half-century.

“Louise Glück was masterful in her craft,” said Carla Hayden, the Librarian of Congress, in a statement. “The precision and beauty in her work spoke to all of her readers because it was a reflection of their own lives.”

She was born in New York in 1943, raised on Long Island and graduated from Columbia University, publishing her first book of poetry in the late 1960s. She rose to prominence in the 1970s, but her career ascended to lofty heights in the 1980s and 1990s, as awards, honors and fellowships poured in. She joined Yale University as a professor in 2004.

The Library has many resources on Glück, but perhaps none is more touching than a recording of her reading at an event nearly half a century ago. It’s from her second collection, “The House on Marshland,” at the Library’s Coolidge Auditorium on April 21, 1975. (She starts at the 36:50 mark.)

It is, in retrospect, a remarkable moment. The young poet, then in her early 30s, so much in front of her, so clearly nervous at the podium. A bit later in the program, she’ll say she was pleased that in this book she was better able to write love poems than in early efforts.

“Um, mostly they didn’t turn out well — I mean, not as poems but as experiences — but it was nice to be able to record them,” she said, drawing a laugh from the audience.

Still, there’s a solemn air here at the beginning. She’s introduced by another U.S. poet laureate, Stanley Kunitz, who closes his remarks by saying, “everything she touches turns to music and legend.”

Applause, silence, footsteps on the stage, papers rustle. The place is as quiet as church.

Then:

“Can you hear? In the back?” she asks the crowd softly, and you’re struck, from the vantage point of today, by how incredibly young she sounds.

Her first poem, then, “All Hallows.” Her voice — clear, slow, almost a chant — reads the first seven lines about a rural farm field, the hills darkening, the crops picked clean, a “toothed moon” rising. And then she reads the rest:

“This is the barrenness

of harvest or pestilence.

And the wife leaning out the window

with her hand extended, as in payment,

and the seeds

Distinct, gold, calling

Come here

Come here, little one

And the soul creeps out of the tree.”

It’s a voice, a vision, that the world would come to revere.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Hispanic Heritage Month: Two Mexican Stories, Including Dolores del Rio

It’s Hispanic Heritage Month, which makes it an excellent time to check in on the Library’s collection of Free to Use and Reuse images, this time from a set devoted to Hispanic life and culture. Visitors to this space will recall that the Library has tons of images that are copyright free, and you may use them in any way you wish.

This time, let’s look at two very different images of Mexican women who came to the U.S. for work.

First is the dazzling image of the legendary actress Dolores del Río (the stage name of María de los Dolores Asúnsolo y López Negrete), who rose to incandescent stardom in the silent film era, became an international symbol of Hollywood’s golden age and then went home to become a star in Mexican cinema for three decades. She was the first Latina to be a major star in Hollywood.

Her first film was in 1925; her last was in 1978. She was so sophisticated, so gorgeous, so magnetic on screen that, in the 1920s, she was billed as the female Rudolph Valentino. She later had an affair with Orson Welles, who called her “the most exciting woman I’ve ever met.” Playwright George Bernard Shaw once gushed “the two most beautiful things in the world are the Taj Mahal and Dolores del Río.” She was besties with Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. She hung out with Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich. You want to know how big a star she was? In 1933’s musical farce, “Flying Down to Rio,” one of her best-known movies, she got solo top billing, her name far larger and more prominent than two young co-stars just starting out … Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire.

She was born in 1904 to an aristocratic family in Durango. The family finances were wiped out in the Mexican Revolution, and they were often in physical danger. They fled to Mexico City, and, still a teenager, she got into acting as a way back to high society. Suffice it to say, it worked. She married young and was in Hollywood, with her new stage name and her first screen credit, by the time she was 21.

But by the mid-1940s, she tired of Hollywood’s controlling studio system and returned to Mexico to work as a collaborative actress, not just a movie star. She was a fabulous success there, too. She died in 1983, at her home in Newport Beach, California, at the age of 78.

The mural was painted in 1990 by Mexican American artist Alfredo de Batuc at the intersection of Hollywood Boulevard and North Hudson Avenue. Touched up and refreshed over the years, it was photographed in 2010 by Carol M. Highsmith. It’s no surprise that de Batuc used such swirling colors and romantic imagery to portray the woman who both lived a dream and inspired dreams in so many more. It is, like the lady herself, a show-stopper. Also like her, it has staying power. It’s still there.

Daughter of a Mexican field laborer; her name was not recorded. Taken near Chandler, Arizona, in May of 1937. Photo: Dorothea Lange. Prints and Photographs Division.

Daughter of a Mexican field laborer; her name was not recorded. Taken near Chandler, Arizona, in May of 1937. Photo: Dorothea Lange. Prints and Photographs Division.Here’s another image with staying power, but from a different part of the Mexican experience in the U.S.: This intense, Depression-era photograph of the child of a Mexican field laborer in 1937 Arizona.

It’s the work of legendary photographer Dorothea Lange, who had been working as a photographer for the federal Resettlement Administration, a government agency formed to raise public awareness of the plight of farmers. This agency evolved into the better known Farm Security Administration. The FSA photographs, now at the Library, produced many images that have become part of the national narrative, none more famous than the “Migrant Mother” photograph that Lange took in 1936 of field laborer Florence Owens Thompson.

We don’t know much about this child at all, other than she was somewhere near Chandler, Arizona, in May 1937. Chandler, these days an outlying suburb of Phoenix, was a tiny town then, around 3,000 people, with farm fields all around. Lange was there to document the poverty of the Depression. Her film rolls show she worked her way around town, taking photographs at several different locations and moving fairly quickly.

She viewed her photography as social activism, not as art. She did not record the names of many of her FSA subjects, including “Migrant Mother,” and often only took a few exposures – just seven for “Mother,” for example. It’s almost certain this encounter with the child was quick and straightforward: A stranger approaches, an introduction, the camera raised, a few snaps. The stranger leaves.

Did Lange ask the girl to frame her face with her hands? Did she say, “Look at me, please?” In any event, caught in the frame are those burning black eyes that match her hair, the furrowed brow on one so young, the simple clothes and, most of all, the uncertainty, the worry.

Two photographs, one of a glamorous woman painted on a brick wall, the other of a tentative girl posed in front of a blank one. Two Mexican women who came north and found such different countries.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s freeLibrary of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers