Library of Congress's Blog, page 15

April 24, 2024

Researcher Story: Cormac Ó hAodha & the Heart of Irish Music

Cormac Ó hAodha, a resident fellow in the John W. Kluge Center, is taking a deep dive into the American Folklife Center’s Alan Lomax Collection. Ó hAodha is looking at field recordings that Lomax, a major figure in 20th-century folklore and ethnomusicology, made in the Múscraí region of County Cork, Ireland. A native of Múscraí, Ó hAodha is now completing his Ph.D. dissertation on the Múscraí song tradition in the Department of Folklore and Ethnology at University College Cork.

Tell us about the Múscraí singing tradition.

The Múscraí Gaeltacht (Irish-speaking) region is a recognized heartland of the Irish language and traditional Irish-language singing.

There are hundreds and hundreds of songs in the tradition, and they relate to all kinds of things — from lullabies to love songs to songs praising place, the people, nature, the rivers and the mountains.

There really is no limit to the kinds of songs — they can be about loss and mourning as well as about celebration and happiness, the entire range of human experience.

Many songs describe the beauty of a woman who the poet meets in a dream. In these songs, this woman represents Ireland with her features recounted in verse, her long tresses of hair sweeping the dew from the grass as she walks at dawn and so on.

A singer’s individual delivery and skill in deploying stylistic ornamentation and musical decoration to the words is what, I believe, makes a good traditional Irish-language, or “sean-nós,” singer.

The “sean-nós” style is a cappella, ideally for an audience that understands and speaks the Irish language. The location can be anywhere, in the pub or at a house party.

I would describe what’s happening as the singer guiding, not dictating, the audience through a series of images described in the poetry of the words.

How did you come to perform?

Personally, I always found singing appealing, and I wanted to join the singers, both in my extended family as well as those in the community, in singing our songs.

I sang “Baile Bhuirne,” which is the name of the village where I live, at the Library’s 2024 Botkin Folklife Lecture Series in March.

It was made, or composed, around 1901 by Micheál Ó Murchadha and Donnchadh Ó Laoghaire. I learned it from the singing of my mother’s first cousin, Diarmuid Ó Súilleabháin.

Diarmuidín, as he was known locally, was among the finest traditional singers of his generation. He died in a car accident in 1991 at age 44. The next year, an annual traditional singing and music festival, Éigse Dhiarmuid Uí Shúilleabháin, was established in his native Cúil Aodha to honor him.

In 2022, the festival issued an album of his singing, also on Spotify, entitled “Diarmuidín.” For anyone who is interested in hearing the best of Irish traditional singing (songs in Irish, songs in English and even bilingual songs), I would highly recommend listening to Diarmuidín.

Why did you seek a Kluge Center fellowship?

I knew Lomax was in Múscraí in 1951 and that he had collected songs from Múscraí singers. When I saw the opportunity to come to the Library and work on the Alan Lomax Collection, I went for it.

Have you discovered anything unexpected so far?

I have discovered quite a lot, especially about initiatives and practices already underway at the Library and elsewhere to “repatriate,” or digitally return, culturally important artifacts and records to the creative sites from which they were collected.

In the case of my own work, that would be songs that are in national repositories in Dublin that need to be repatriated to the community in Múscraí in County Cork. I find all of this fascinating and hope to bring some of these ideas and approaches into practice on my return to Ireland.

What will be the end product of your research at the Library?

I’ll be promoting the notion of “slow archiving” — prioritizing collaborative relationships with community stakeholders when it comes to artifacts in the care of national institutions in Ireland, the majority of which are in Dublin, a seven-hour round trip by road from Múscraí.

Anything else you’d like to share about your time at the Library?

It has been an opportunity that rarely comes in an entire lifetime, and I am very conscious of that.

With the help of the wonderful staff in AFC’s reading room, I have had the privilege of listening to all of the radio programs on folksongs that Lomax made and that were broadcast in the 1950s and 1960s on American radio and, in the case of Irish folksongs, on BBC radio.

I simply cannot praise the staff of the Library enough. I am grateful to all of the specialists I have come into contact with at the Kluge Center, AFC and the Performing Arts Reading Room. My thanks also to my fellow Kluge scholars.

Go raibh míle maith agaibh go léir (thank you all).

Read more about the Lomax collection.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

April 16, 2024

National Recording Registry 2024! Green Day, Blondie, Doug E. Fresh, Juan Gabriel!

-Brett Zongker, the Library’s chief of media relations, contributed to this story.

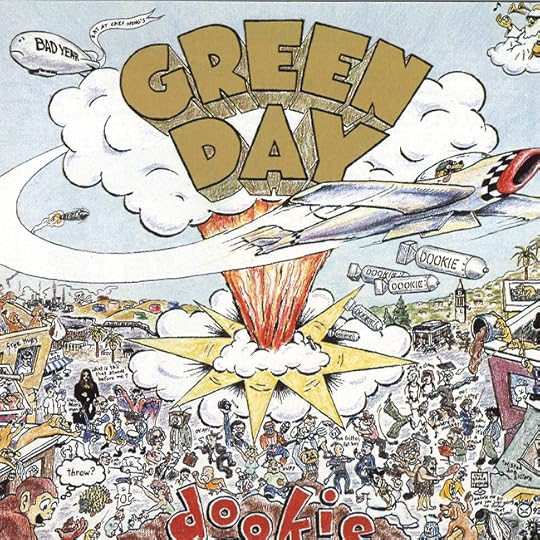

Billie Joe Armstrong, the lead singer and songwriter for Green Day, said that the youthful band wasn’t thinking of making a generation-defining album when they starting work on “Dookie,” their breakout record of 1994. They just wanted to keep rocking.

Still, the record that produced hits such as “Longview,” “Basket Case” and “Welcome to Paradise” is still relevant 30 years later, and that makes it one of the headline entries of the 2024 National Recording Registry class, announced today by Carla Hayden, the Librarian of Congress.

“I think in the back of our minds was to be able to play music together for the rest of our lives,” Armstrong said in an interview with the Library. “That’s quite a goal when you’re 20 or 21 years old. But, you know, we’ve managed to do it, and it’s just been an amazing journey.”

“Dookie,” Green Day’s breakout 1994 album.

“Dookie,” Green Day’s breakout 1994 album.Other headliners: ABBA’s “Arrival” album, Blondie’s “Parallel Lines,” The Notorious B.I.G.’s landmark “Ready to Die,” and The Chicks’ “Wide Open Spaces.” They’re among the 25 songs, albums, broadcasts or other recordings that were selected by the National Recording Preservation Board and the Librarian to join the registry this year.

“We have selected audio treasures worthy of preservation with our partners this year, including a wide range of music from the past 100 years,” Hayden said. “We were thrilled to receive a record number of public nominations, and we welcome the public’s input on what we should preserve next.”

The 2024 class also includes Gene Autry’s “Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” The Cars’ debut album, Juan Gabriel’s “Amor Eterno,” Héctor Lavoe’s salsa hit “El Cantante,” Kronos Quartet’s “Pieces of Africa,” Johnny Mathis’ “Chances Are,” Bobby McFerrin’s “Don’t Worry, Be Happy,” Patti Page’s “Tennessee Waltz” and Bill Withers’ “Ain’t No Sunshine.”

There are now 650 recordings in the registry, a miniscule fraction of the Library’s holdings of nearly 4 million recordings. The registry, begun in 2002, holds items from the beginning of recorded sound in the 1850s to things created as recently as 10 years ago, the cutoff point for consideration.

A record 2,899 nominations were made by the public this year. (You can nominate additions for next year’s class until Oct. 1, 2024.)

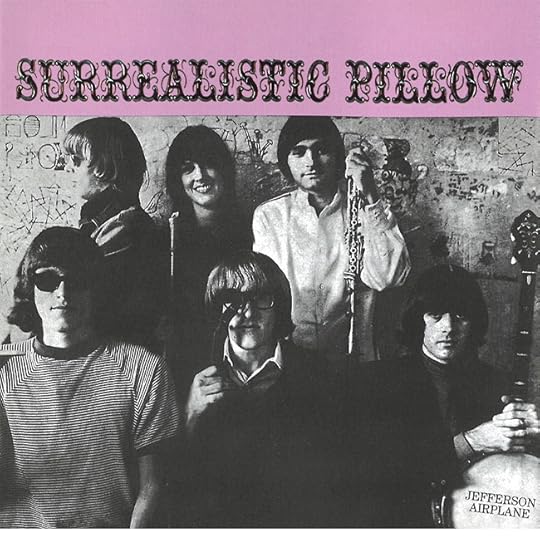

Jefferson Airplane’s “Surrealistic Pillow” launched the band into pop-culture fame.

Jefferson Airplane’s “Surrealistic Pillow” launched the band into pop-culture fame.Jefferson Airplane brought the San Francisco hippie scene of the mid-1960s to the rest of the nation, knocking out psychedelic hits such as “White Rabbit” even as tour buses trundled through their Haight-Ashbury neighborhood to get a glimpse of the wild side.

Their second album, “Surrealistic Pillow,” made an indelible mark on the era, with “Somebody to Love” joining “Rabbit” as a major hit. The band would go on to play at both the Woodstock and Altamont music festivals and become synonymous with rock music of the day.

“We thought that we invented sex, drugs and rock and roll, and we might have invented some rock and roll, but I don’t think we had much to do with inventing the other two,” Jorma Kaukonen, the band’s lead guitarist, told the Library in recent interview.

Lead singer Grace Slick wrote “White Rabbit” based on Lewis Carroll’s children’s novel, “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.” The Victorian story became a classic, Slick read it as a child and, as many others had, took Alice’s surreal experiences “down the rabbit hole” (with a fussy white rabbit as her guide) as a metaphor for drug use. “Go ask Alice,” she intones over the song’s march-like bass line, referring to an incident in the book, “when she’s 10 feet tall.”

The song was “a shot” at her parents’ generation, she said, who thought little of their own alcohol use but excoriated ’60s kids for smoking marijuana and dropping acid.

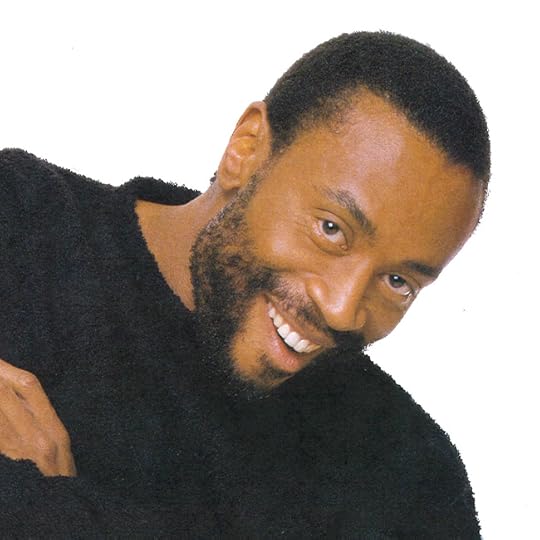

Bobby McFerrin’s “Don’t Worry, Be Happy” is in the registry.

Bobby McFerrin’s “Don’t Worry, Be Happy” is in the registry.Juan Gabriel’s “Amor Eterno,” a heartrending ballad he started performing in the 1990s in memory of his deceased mother, has long been a staple in the singer’s native Mexico and across Latin America, and this year it joins the registry.

Gabriel died in 2016 at the age of 66, but his son, Ivan Aguilera, said his father would have been thrilled to see one of his most famous songs be enshrined in the registry.

“He would always say that ‘as long as the public, people, keep singing my music, Juan Gabriel will never die,’ and it’s nice to see that happening here,” Aguilera said.

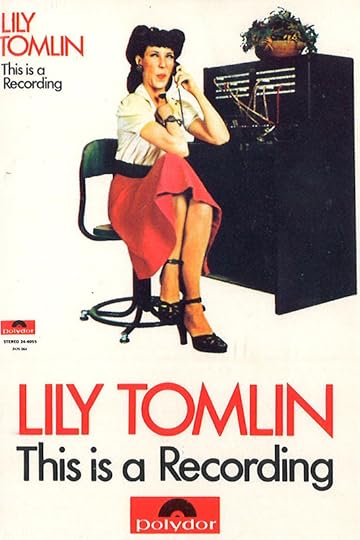

Lily Tomlin’s trademark character, “Ernestine,” made it into the registry with her comic album, “This is a Recording.”

Lily Tomlin’s trademark character, “Ernestine,” made it into the registry with her comic album, “This is a Recording.”Here’s the complete 2024 list, in chronological order:

“Clarinet Marmalade” – Lt. James Reese Europe’s 369thS. Infantry Band (1919)“Kauhavan Polkka” – Viola Turpeinen and John Rosendahl (1928)Wisconsin Folksong Collection (1937-1946)“Rose Room” – Benny Goodman Sextet with Charlie Christian (1939)“Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer” – Gene Autry (1949)“Tennessee Waltz” – Patti Page (1950)“Rocket ‘88’” – Jackie Brenston and His Delta Cats (1951)“Catch a Falling Star” / “Magic Moments” – Perry Como (1957)“Chances Are” – Johnny Mathis (1957)“The Sidewinder” – Lee Morgan (1964)“Surrealistic Pillow” – Jefferson Airplane (1967)“Ain’t No Sunshine” – Bill Withers (1971)“This Is a Recording” – Lily Tomlin (1971)“J.D. Crowe & the New South” – J.D. Crowe & the New South (1975)“Arrival” – ABBA (1976)“El Cantante” – Héctor Lavoe (1978)“The Cars” – The Cars (1978)“Parallel Lines” – Blondie (1978)“La-Di-Da-Di” – Doug E. Fresh and Slick Rick (MC Ricky D) (1985)“Don’t Worry, Be Happy” – Bobby McFerrin (1988)“Amor Eterno” – Juan Gabriel (1990)“Pieces of Africa” – Kronos Quartet (1992)“Dookie” – Green Day (1994)“Ready to Die” – The Notorious B.I.G. (1994)“Wide Open Spaces” – The Chicks (1998)Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

April 15, 2024

The Adams Building Turns 85!

-This is a guest post by Jennifer Harbster, head of the science section.

The year was 1939. Pan American Airways’ Yankee Clipper made its first transatlantic passenger flight. The technology company Hewlett-Packard was founded in a garage in Palo Alto, California. Scientists at Iowa State College developed the prototype for the first digital computer.

And at the Library, the John Adams Building opened just three days into the year. Boasting elevators, pneumatic tubes and air-conditioning, the building was available to researchers in April.

To celebrate this 85th anniversary, the Science and Business Reading Room is hosting a “A Night at the Adams,” on April 18 from 5 to 8 p.m. The event, which is sold out, will feature tours of the stunning reading room, curated displays and a scavenger hunt.

The Adams Building. Photo: Shawn Miller

The Adams Building. Photo: Shawn MillerThe building was proposed to Congress in 1928. It was orginally known as “the Annex” to the adjacent Thomas Jefferson Buildling and funding was appropriated in 1930 and 1935. David Lynn, then the Architect of the Capitol, commissioned a design from the architectural firm of Pierson and Wilson. The result was an elegant building that today complements its next-door neighbor, the Folger Shakespeare Library. It was renamed for the second U.S. president in 1980.

The Adams incorporates traditional beaux arts architectural styles, including Italian Renaissance and classical Greco-Roman details, along with fashionable art deco designs. This mixture of styles was popular in the U.S. in the 1920s and 1930s and is today referred to as “Greco deco,” an architectural term coined by art historian James M. Goode.

Beautifully selected marble, stone and other materials from around the country grace the building at every turn. The exterior is faced in Georgia white marble with a skirt of North Carolina pink granite around the base. Inside, St. Genevieve rose marble from Missouri, Travertine limestone from Montana and Cardiff green marble from Maryland are featured.

Underfoot are beautifully crafted terrazzo and mosaic floors produced by the National Mosaic Company of Washington, D.C., the same company responsible for the floors of many of the city’s federal buildings.

Advertisements and articles in the Federal Architect and Modern Plastics magazines from the late 1930s tout the Adams’ architecture and design achievements — the building incorporates examples of industrial arts and materials science considered exceptional at the time.

Tiles made of Vitrolite, a shiny structural pigmented glass popular in art deco designs, cover stairwell walls and other surfaces. Aluminum, bronze and nickel are used in metalwork details.

The use of Formica, in particular, is noteworthy. The building won awards for it. A laminated plastic material used in decorative applications, Formica features in the reading room’s green wall paneling and study tables.

At its core, the Adams Building contains 12 tiers of bookstacks extending from the basement to the fourth floor. Each tier covers 13 acres of space; together, the tiers can hold up to 10 million books. Staff offices and workspaces encircle the bookstacks.

Topping everything off on the fifth floor are two high-ceilinged reading rooms adorned with murals by artist Ezra Winters and art deco designs by sculptor Lee Lawrie.

Winters was commissioned to paint murals in the South Reading Room, the current home of the Science and Business Reading Room, as a tribute to Jefferson — the space was known fondly as the Jefferson Reading Room for many years.

Panels highlight individuals from Colonial and Federalist America and quotations from Jefferson’s letters on the themes of freedom, labor, education and democratic government. In a lunette above the book services desk, a stately dedication depicts Jefferson in front of his Monticello, Virginia, residence.

In the North Reading Room, now a collection management space accessible only to staff members, Winters painted a colorful and animated procession of characters from Chaucer’s “Canterbury Tales.”

The east and west walls depict pilgrims as they are introduced in the prologue with the west wall also showcasing a cameo of Chaucer himself. The north clock wall illustrates the opening lines of the prologue, while the south wall lunette, inspired by the prologue of “The Franklin’s Tale,” shows three musicians.

A sculpted owl gazes out from the Adams Building entrance on Independence Avenue. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith.

A sculpted owl gazes out from the Adams Building entrance on Independence Avenue. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith.Architectural sculptor Lee Lawrie, a notable artist of the time, adorned the Adams Building with an array of modernist details and deco designs. His standout works include the sculpture “Atlas” at Rockefeller Center in New York City and “The Sower” and other sculptures decorating the Nebraska state capitol in Lincoln.

Ground-floor bronze doors in the Adams Building feature sculptural reliefs Lawrie designed to symbolize the history of the written word, and exterior friezes tell stories from antiquity and ancient civilizations.

Elsewhere, Lawrie’s artistic touch is visible in beautiful grille work on reading room doors and on elevator doors that take staff members to the stacks. His plant motifs in metal and stone appear in elevator lobbies and on doors, water fountains and walls. Owls he designed with geometric shapes and dressed in nickel, aluminum or stone, nest about the reading room and on the exterior of the building.

The intricate and highly symbolic designs and wealth of detail Winter and Lawrie incorporated into the Adams Building — along with the artistry of many others — make the Adams much more than an annex: It is truly a worthy a companion to its older sibling, the Jefferson Building.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

April 11, 2024

My Job: Alan Gevinson

Alan Gevinson will retire later this year as special assistant to the chief of the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center.

Tell us about your background.

I grew up in Silver Spring, Maryland, during the ’50s and ’60s. After getting my driver’s license at age 16, I discovered a world of foreign films and classic Hollywood movies screened at funky Washington, D.C., repertory houses that no longer exist. I was hooked.

Later, I went to a small liberal arts college, where I was able to run the film society for a year. Afterward, I spent two years at New York University’s Graduate Institute of Film and Television learning the craft of filmmaking. I wanted both to make and study films, but after working on a few television documentaries, my filmmaking career path came to a dead end.

I was fortunate, though, to land a job with the American Film Institute Catalog of Feature Films project in Los Angeles, researching, editing, writing and viewing films for a series of reference books. It was really a dream job, especially because of the collegiality of my fellow AFI catalogers.

After 12 years, I went back to school, this time in cultural studies at George Mason University. A couple of years later, I migrated to a Ph.D. program in history at Johns Hopkins University. I then did adjunct teaching in GMU’s graduate history program before beginning my current job at the Library in 2011.

What brought you to the Library?

In 1980, after my first year at NYU, I worked in a summer job in the Prints and Photographs Division helping Beverly Brannan organize the Alexander Graham Bell and Toni Frissell collections. When I’ve mentored interns in recent years, I’ve told them I hope the experience of immersing themselves in a sea of primary sources and learning ways to make sense of them is as rewarding for them as it was for me 40 years ago.

Over the ensuing years, I worked in a variety of temp and contract jobs for the Library. When my current position was created in 2011, I jumped at the opportunity to bring a cultural history perspective to NAVCC projects.

What achievements are you most proud of?

Over the past 10 years, I’ve worked with fantastic colleagues at the Library and GBH, Boston’s public broadcaster, on the American Archive of Public Broadcasting project. To date, we have digitally preserved more than 160,000 public television and radio programs from more than 500 stations, producers and archives at NAVCC and made more than 100,000 available online for free on the project’s website, americanarchive.org. It is managed by GBH but co-branded by both institutions.

The collection includes a wealth of local programming from all over that now is accessible nationwide for the first time. AAPB offers many programs produced by Black, Latino, Asian and Native American communities who long have advocated for the public broadcasting system to live up to its foundational goal of diversity.

And we make available online tens of thousands of nationally acclaimed news and public affairs shows, like the Bill Moyers and PBS NewsHour collections and 40 years of Harry Shearer’s wickedly clever weekly satirical radio program “Le Show,” which I listened to on Sunday mornings in the 1980s when I lived in LA.

It’s been immensely rewarding to work with hundreds of people throughout the nation who respect the mission of public broadcasting and with talented Library interns who have created wonderfully engaging exhibits for the AAPB website on a variety of salient topics.

What are some standout moments from your time at the Library?

I was honored to show Rep. John Lewis clips of himself from a 1960 television documentary on the Nashville sit-ins at the opening of “The Civil Rights Act of 1964” exhibit, curated by Manuscript Division historian Adrienne Cannon.

In conjunction with an exhibit in the Library’s Bob Hope Gallery of American Entertainment, I gave tours to Norman Lear and his family, Gary Sinise and his daughter and Paula Poundstone and her daughter. I also gave a presentation to the Military Officers Association of America, where almost all hands in the packed house went up when I asked how many had actually seen Bob Hope at a Christmas show during tours of duty in Vietnam. The indelible impact of entertainment in wartime really hit home to me that instant.

But my most memorable moment occurred during a research trip to the Library in the early 1990s when I still worked for the AFI. As I was viewing a 35mm film, a hand tapped me on the shoulder. I turned and looked for the very first time into the face of the woman who would become my wife, Nancy Seeger, then a recorded sound cataloger. She had been told by our mutual friend, Sam Brylawski, that she should meet me. Nancy retired from the Library a few years ago, and I’ll join her in retirement in the spring.

What’s next for you?

When I met Bill Moyers at a Library event a few months ago, he gave me a word of advice about what to do once I retired. Read, he said. I look forward to taking that advice.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

April 9, 2024

An 800-Year-Old (Tiny) Book of Hours

— This is a guest post by Marianna Stell, a reference specialist in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division. It also appears in the March-April issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

In the medieval world, impossibly small, cleverly constructed objects made of precious materials were appreciated for their craftsmanship and their inherent miraculous quality.

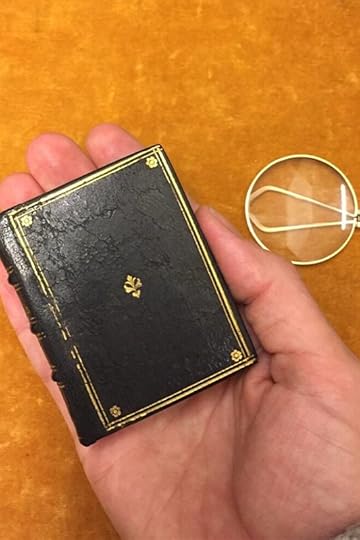

The Edith Book of Hours, a handwritten 14th-century volume of prayers, is such an object, one that today still prompts viewers to ask: How could anyone create something so small?

The book, which measures just 25/8 inches tall and 17/8 inches wide, contains more than 300 pages. It is a masterpiece of Gothic illumination, with its many lovely leaves containing delicate, scrolling border designs and flawless miniatures crafted in the style of Parisian artist Jean Pucelle.

Renowned collector Lessing J. Rosenwald presented the book to his wife, Edith, on her birthday in 1951 — along with a custom case and a small magnifying glass to make viewing easier. Edith donated the book to the Library in 1981 in commemoration of her husband, who had passed away two years earlier.

Today, the Edith Book of Hours is part of the Library’s Rosenwald Collection and the beauty and meaning found in its pages still amazes.

The Edith Book of Hours with its magnifying glass. Rare Book and Special Collections Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

The Edith Book of Hours with its magnifying glass. Rare Book and Special Collections Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.In a miniature rendering of the Annunciation, the Virgin Mary holds a book in her hand and a centrally placed scroll highlights the moment when, in the Christian tradition, the “Word became flesh” in a verbal exchange between Mary and the angel Gabriel. “Ave maria gratia plena,” the scroll reads: “Hail Mary, full of grace.”

The scene, and the book itself, invites its readers to experience the miracle of just how small words can be: tiny letters written on a tiny scroll within a tiny miniature within a tiny book.

Recently digitized, the volume now can be appreciated by more than one person at a time, allowing people everywhere to experience the smallness of the Edith Book of Hours. Centuries after the book was created, it still feels nothing short of miraculous.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

April 2, 2024

“Language is Life” and Native American Historical Voices

The anticipation in the small room in Culpeper, Virginia, was palpable as the stylus touched down on a rare 100-year-old wax cylinder recording. Chin in hand, film producer Daniel Golding sat while his son, Nate, stood behind him, hands in pocket.

A scratchy sound emerged, followed by a man’s voice, which Golding identified as his great-grandfather’s. He was singing a deer song in the language of the Quechans, a Native American tribe indigenous to an area along the Mexico border in Arizona and California.

“My great-grandfather was the last one to sing these songs,” Golding said. “There’s nobody left in the community that sings them.”

Golding brought a film crew to the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center in July 2022 to document a collaboration between the Library and another tribe — the Passamaquoddy of Maine — to recover and share tribal language and cultural practices from wax cylinder recordings in the collections.

Golding’s film, “Language Is Life,” showcases efforts by three Native communities — the Passamaquoddy, the Cherokee and the Navajo — to revitalize their languages and, through language, to revive cultural heritage.

Narrated by Joy Harjo, the former U.S. poet laureate, the film premiered at the Library last November in advance of its broadcast as one of four episodes in the PBS series, “Native America.”

Anthropologist Jesse Walter Fewkes documented Passamaquoddy folktales, origin stories and vocabulary in 1890 using wax cylinders, the recording medium of the day. The 31 Passamaquoddy recordings donated to the Library are the oldest ethnographic field recordings known to survive anywhere.

The Library holds a total of about 9,000 turn-of-the-20th-century field recordings of Native communities, the largest collection in the U.S. Between 1977 to 1987, the Library’s American Folklife Center transferred these early field recordings to reel-to-reel cassette tape as part of the Federal Cylinder Project.

Since 2015, using cutting-edge laser-assisted technology, NAVCC has been digitizing and restoring these recordings through a project called Ancestral Voices — informally dubbed Federal Cylinder Project 2.0. Ancestral Voices is part of a larger collaboration involving the AFC, Native communities and other cultural institutions to support revitalization of Native languages and cultures.

The task is urgent: According to “Language Is Life,” linguists predict that only 20 Native languages will be spoken in North America by 2050, down from more than 300 in 1492, if language loss isn’t reversed.

AFC is collaborating with communities to curate digitized recordings and release them selectively on the Ancestral Voices portal — communities do not want all materials shared publicly. The folklife center also provides copies directly to Native tribes.

In recent years, for example, it provided the Warm Springs Reservation in Oregon with copies of out-of-circulation recordings that allowed the community to reincorporate content not used in 70 years and Sioux communities with copies of photographs and recordings that they said documented the proper way to butcher buffalo, an important cultural tradition..

When Golding heard the newly digitized recording of his great-grandfather in Culpeper in 2022, he immediately recognized a big improvement over a recording his parents had played for him in the 1970s. The speed was corrected, and the sound was much clearer.

For his son, Nate, then 16, the experience was more profound — he had never heard his great-great-grandfather’s voice before.

“I hope these traditions are passed down to the younger generation so the tradition can live on,” Nate said, holding back tears. “It gives me hope for our community to become stronger. It just gives me hope in my heart.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Gershwin Winner Bernie Taupin in Conversation

The word “extraordinary” came up a lot in the Coolidge Auditorium last Thursday evening. Bernie Taupin took the stage on March 21 to speak with Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden about his songwriting journey with Elton John.

The night before, the duo accepted the 2024 Gershwin Prize for Popular Song during an all-star tribute concert in Constitution Hall.

The concert itself was extraordinary, Taupin said, as were the renditions of his and John’s songs.

“Metallica, come on!” Taupin exclaimed of the metal band’s raucous performance of “Funeral for a Friend/Love Lies Bleeding.”

“He just tore it up,” he said of Billy Porter’s version of “The Bitch Is Back.” And of Jacob Lusk’s “Bennie and the Jets”: “He just was preachin’ now!”

“Hearing all of those songs from those wonderfully diverse acts last night, it was, I mean this from the bottom of my heart, it was really, really extraordinary,” Taupin said.

But perhaps most extraordinary of all, in Taupin’s telling, were the collections of the Library itself, which curators shared with him and John in the days before the concert.

“The things that I’ve seen since I’ve been here are just completely staggering,” Taupin said. “It boggles the mind to know that they exist still — things that influenced me, influenced Elton, influenced us as a unit together.”

Taupin spoke of the lyrics to Marty Robbins’ Western ballad “El Paso” on Robbins’ album “Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs.”

“It’s still one of the most important records to me in my life,” Taupin said.

Growing up in rural England in the 1950s and early 1960s, Taupin didn’t hear much country music on the radio. When he became acquainted, he was hooked.

“When I heard those songs, I went ‘Wow, there’s a way here that you can actually tell … stories and sing them,’” he said. “What I needed to do was find somebody who could create the other 50% of the magic.”

“Well, that worked out,” Hayden quipped.

Taupin met John in 1967, when they each separately answered a newspaper ad from a record company. Soon, they established a pattern: Taupin writes lyrics, then gives them to John to set to music.

Since the 1969, the duo has sold an estimated 300 million albums and made Billboard history multiple times over. Last year, John’s “Farewell Yellow Brick Road” tour became the highest-grossing concert tour of all time.

They weren’t an overnight success, though.

At first, Taupin said, “I was flying by the seat of my pants.”

His lyrics “all came out on a page, and Elton had to decipher what was what.”

But over time, he became musically proficient. His process now, Taupin said, is “guitar, legal pad, computer, finish.”

He plays a few chords on a guitar, sings a little to himself, then scrawls lyrics on yellow legal pad. Periodically, he types the lyrics into a computer to assess their flow.

He works quickly, but his reputation for speed writing is overstated, he said.

“I didn’t write ‘Your Song’ in 10 minutes,” he joked. “It was probably 15.”

Taupin insists he is a storyteller, not a poet. “I loathe it being called poetry,” he said of his writing. “I want my things to be regarded as stories.”

For inspiration, he draws on the American West — he’s lived there since the 1970s — and literature.

“I have farmed and mined 20th-century literature,” Taupin said, and the writing of Graham Greene “more than most.”

“A lot of my characters are certainly based on characters he created,” Taupin said.

Meeting Greene by chance “was one of the greatest moments of my life, outside of being given the Gershwin Prize,” Taupin said.

Another almost chance encounter also greatly impacted his life. For his 40th birthday party, Taupin — a huge jazz and blues fan — asked his managers in jest to invite Willie Dixon, “probably the greatest blues songwriter of all time.”

To Taupin’s surprise, Dixon came.

“We just hit it off,” Taupin said. “There are a handful of people who were huge, huge influences on my life. … He was so generous, just an extraordinary man.”

After Dixon died in 1992, Taupin found out Dixon hadn’t yet been inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame. Taupin threatened to give back his own awards if Dixon wasn’t added “straight away.” He was.

A visual artist since the early 1990s, Taupin spends more time on his art these days than songwriting. In the early 1970s, he and Elton made two albums a year.

“Now, you’re lucky if we make one record every 10 years,” he said. “Visual art is a huge part of my life.”

Before Taupin took the stage, ticket holders were treated to a special exhibition in the Whittall Pavilion of some of the treasures he and John viewed.

The American Folklife Center and the Recorded Sound Section displayed items tracing the history of the song “Rock Island Line” from a 1934 recording John Lomax made in an Arkansas state prison to a 1940s Lead Belly rearrangement to a 1955 chart-topping skiffle reinterpretation by the English singer Lonnie Donegan.

When Taupin saw the original 78 by Donegan at the Library, he said it brought him back to “a little house in the suburbs of London where I discovered that 78 when I was 12 years old.”

Other items on display included a 1966 ad for a London gig in which John’s then band, Bluesology, opened for The Move, later known as Electric Light Orchestra; a 1967 copyright application filed under John’s birth name, Reginald Kenneth Dwight; and words and phrases Ira Gershwin jotted down in 1926 while brainstorming “Someone to Watch Over Me,” recorded by John decades later.

At the end of the evening, to commemorate Taupin’s Gershwin Prize experience, Music Division chief Susan Vita presented him with a facsimile of Gershwin’s first draft of the lyrics to “Love Is Here to Stay” beside a typewritten final version.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Gershwin Winner Bernie Taupin in Coversation

The word “extraordinary” came up a lot in the Coolidge Auditorium last Thursday evening. Bernie Taupin took the stage on March 21 to speak with Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden about his songwriting journey with Elton John.

The night before, the duo accepted the 2024 Gershwin Prize for Popular Song during an all-star tribute concert in Constitution Hall.

The concert itself was extraordinary, Taupin said, as were the renditions of his and John’s songs.

“Metallica, come on!” Taupin exclaimed of the metal band’s raucous performance of “Funeral for a Friend/Love Lies Bleeding.”

“He just tore it up,” he said of Billy Porter’s version of “The Bitch Is Back.” And of Jacob Lusk’s “Bennie and the Jets”: “He just was preachin’ now!”

“Hearing all of those songs from those wonderfully diverse acts last night, it was, I mean this from the bottom of my heart, it was really, really extraordinary,” Taupin said.

But perhaps most extraordinary of all, in Taupin’s telling, were the collections of the Library itself, which curators shared with him and John in the days before the concert.

“The things that I’ve seen since I’ve been here are just completely staggering,” Taupin said. “It boggles the mind to know that they exist still — things that influenced me, influenced Elton, influenced us as a unit together.”

Taupin spoke of the lyrics to Marty Robbins’ Western ballad “El Paso” on Robbins’ album “Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs.”

“It’s still one of the most important records to me in my life,” Taupin said.

Growing up in rural England in the 1950s and early 1960s, Taupin didn’t hear much country music on the radio. When he became acquainted, he was hooked.

“When I heard those songs, I went ‘Wow, there’s a way here that you can actually tell … stories and sing them,’” he said. “What I needed to do was find somebody who could create the other 50% of the magic.”

“Well, that worked out,” Hayden quipped.

Taupin met John in 1967, when they each separately answered a newspaper ad from a record company. Soon, they established a pattern: Taupin writes lyrics, then gives them to John to set to music.

Since the 1969, the duo has sold an estimated 300 million albums and made Billboard history multiple times over. Last year, John’s “Farewell Yellow Brick Road” tour became the highest-grossing concert tour of all time.

They weren’t an overnight success, though.

At first, Taupin said, “I was flying by the seat of my pants.”

His lyrics “all came out on a page, and Elton had to decipher what was what.”

But over time, he became musically proficient. His process now, Taupin said, is “guitar, legal pad, computer, finish.”

He plays a few chords on a guitar, sings a little to himself, then scrawls lyrics on yellow legal pad. Periodically, he types the lyrics into a computer to assess their flow.

He works quickly, but his reputation for speed writing is overstated, he said.

“I didn’t write ‘Your Song’ in 10 minutes,” he joked. “It was probably 15.”

Taupin insists he is a storyteller, not a poet. “I loathe it being called poetry,” he said of his writing. “I want my things to be regarded as stories.”

For inspiration, he draws on the American West — he’s lived there since the 1970s — and literature.

“I have farmed and mined 20th-century literature,” Taupin said, and the writing of Graham Greene “more than most.”

“A lot of my characters are certainly based on characters he created,” Taupin said.

Meeting Greene by chance “was one of the greatest moments of my life, outside of being given the Gershwin Prize,” Taupin said.

Another almost chance encounter also greatly impacted his life. For his 40th birthday party, Taupin — a huge jazz and blues fan — asked his managers in jest to invite Willie Dixon, “probably the greatest blues songwriter of all time.”

To Taupin’s surprise, Dixon came.

“We just hit it off,” Taupin said. “There are a handful of people who were huge, huge influences on my life. … He was so generous, just an extraordinary man.”

After Dixon died in 1992, Taupin found out Dixon hadn’t yet been inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame. Taupin threatened to give back his own awards if Dixon wasn’t added “straight away.” He was.

A visual artist since the early 1990s, Taupin spends more time on his art these days than songwriting. In the early 1970s, he and Elton made two albums a year.

“Now, you’re lucky if we make one record every 10 years,” he said. “Visual art is a huge part of my life.”

Before Taupin took the stage, ticket holders were treated to a special exhibition in the Whittall Pavilion of some of the treasures he and John viewed.

The American Folklife Center and the Recorded Sound Section displayed items tracing the history of the song “Rock Island Line” from a 1934 recording John Lomax made in an Arkansas state prison to a 1940s Lead Belly rearrangement to a 1955 chart-topping skiffle reinterpretation by the English singer Lonnie Donegan.

When Taupin saw the original 78 by Donegan at the Library, he said it brought him back to “a little house in the suburbs of London where I discovered that 78 when I was 12 years old.”

Other items on display included a 1966 ad for a London gig in which John’s then band, Bluesology, opened for The Move, later known as Electric Light Orchestra; a 1967 copyright application filed under John’s birth name, Reginald Kenneth Dwight; and words and phrases Ira Gershwin jotted down in 1926 while brainstorming “Someone to Watch Over Me,” recorded by John decades later.

At the end of the evening, to commemorate Taupin’s Gershwin Prize experience, Music Division chief Susan Vita presented him with a facsimile of Gershwin’s first draft of the lyrics to “Love Is Here to Stay” beside a typewritten final version.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

March 28, 2024

Working with Young Readers: Monica Smith

Monica Smith is chief of the Informal Learning Office.

Tell us about your background.

I’m a native Californian. I grew up in San Diego with my teacher parents and sister, earned a bachelor’s degree in American history at Pomona College, then worked briefly in San Francisco before moving to Washington, D.C.

A high school internship at the San Diego History Center’s Research Archives inspired me to pursue four more internships through and just after college, ending with the Smithsonian Institution. In 1995, I began my career at the National Museum of American History’s Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation. Starting as a researcher, I became an exhibition curator, an educator, a project director and, finally, acting deputy director of the center. I transitioned to the Library in December 2023.

What brought you to the Library, and what do you do?

After three decades at the Smithsonian, I was ready for a career move, and the Library was about the only place I could think of that would be a step up. Fortunately, the position of chief of the Informal Learning Office felt like the perfect fit for my interests, skills and experience.

It’s a thrill to work in the nation’s library to help engage, educate and inspire the next generation of researchers and their families. I enjoy overseeing the team spearheading ILO’s new monthly Family Days at the Library featuring creative hands-on activities with related take-home resources based on Library collections.

ILO also runs the Young Readers Center and Programs Lab in the Jefferson Building; writes the blog Minerva’s Kaleidoscope for families and educators; hosts or co-hosts internships, including for teens; and pilots on-site and online school programs as we gear up for the opening of The Source: A Creative Research Studio for Kids, part of the visitor experience, in 2026.

My overall goal is to raise the profile of the Library’s programs and resources among more, and more diverse, youth and families.

What are some of your standout projects?

At the Smithsonian I was proud to be the project director, co-curator and principal investigator for three National Science Foundation-funded exhibition projects, “Invention at Play,” “Places of Invention” and “Change Your Game/Cambia tu juego,” which opens at the National Museum of American History on March 15.

Among my friends, however, I’m best known for being the curator of an exhibition about the invention of the electric guitar early in my career. I gave numerous presentations about it, wrote articles and was a featured speaker in the film “Electrified: The Guitar Revolution.” I was also interviewed on BBC, CNN and other media outlets, including a local news broadcast honoring Prince after his death. My first project nickname “Stratocaster Woman” evolved into “Monicaster,” a name I’m still called by former colleagues.

What do you enjoy doing outside of work?

My main passion — besides spending quality time with family and friends, reading, baking and volunteering — is most certainly travel. I’m on a quest to visit as many countries as my age; currently, I’m a couple ahead at 55.

Just since 2019, I’ve been to Bali, Belgium, Costa Rica, Croatia, England, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Italy, Jordan, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, Montenegro, Qatar, Singapore, Switzerland and Turkey. Overall, my favorite trip was probably to the Galápagos Islands with Egypt and Tanzania close behind.

I’ve also loved touring all 50 U.S. states. If you come to my office in the Madison Building, you’ll see a world map on the wall with pins showing where I’ve been. It inspires me to think about where I want to travel next and maybe spend more time in retirement.

What is something your co-workers may not know about you?

I attended a public school in San Diego for the creative and performing arts. It was an amazing experience to be part of a very racially and economically diverse student body with kids from across the city. It didn’t matter your age, background or even talent: You could participate in any art that interested you.

I focused on playing the violin, singing in choir and taking ballet, but I also dipped my toes into dramatic acting, musicals and all kinds of dance. I also loved academics, especially history and English.

The experience helped build my self-confidence, providing tools I still use for giving public speeches or even just meeting new people. It also instilled in me a lifelong love and appreciation for the arts and for youth education.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

March 26, 2024

Blood Sausage and Family Ties: An Immigrant Story

This is a guest post by Clinton Drake, a reference librarian in the History and Genealogy Section.

Listen: It turns out my family used to eat blood.

As far as I know, we’re not vampires or anything — although my people do hail from the dark lands of northern Europe — but no kidding, the things you learn looking through old grocery lists.

In my case, these lists were a pair of thin, palm-sized grocery store account books for Juho (John) Säkkinen, my second great-grandfather. In the 1880s, he emigrated from the tiny town of Taivalkoski, Finland (population about 3,000), to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

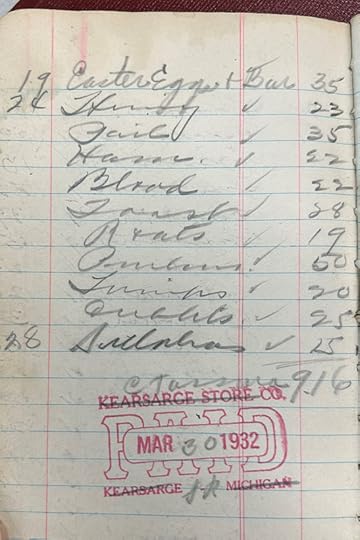

Nearly 50 years later, as the Depression began, he was shopping at a local store and had a certain amount of credit, as was common then. Someone in the family would stop by to pick up a few things and the storekeeper (Charles Tossava, another Finn) would jot down the item and the cost, the payment to be arranged later. The Säkkinen family account shows a mix of Old World staples and American brand names, a glimpse into the life of an immigrant family in the small-town world of the Midwest in another era.

“1 # Sillaka” (salted herring) 15 cents,” Tossava scrawled in pencil. “1 pkg Corn Flakes, 10 cents.” And so on.

And then, on March 24, 1932, he scratched out on a line by itself: “Blood. 22 cents.”

A page from Juho Säkkinen’s 1932 grocery account, with “Blood” as the fifth item. Photo: Clinton Drake.

A page from Juho Säkkinen’s 1932 grocery account, with “Blood” as the fifth item. Photo: Clinton Drake.That certainly caught my attention. I had come across these books during a recent move from my Texas-sized home in Austin to my D.C.-sized apartment in the nation’s capital, starting a new job at the Library. I tend to be the unofficial keeper of the family flame, with heirlooms that others don’t want somehow finding their way to me. But this move required some serious downsizing, so I found myself going through a stack of such things, saw the account books and started flipping through them, curious.

Before I could fully register the surprise of seeing “blood,” I was transported back to the world of my youth. Memories came flooding back of my grandmother, Juho’s granddaughter, telling me about the strange foods of “our people.” Kalamojakka (fish head stew), lutefisk (dried fish rehydrated in lye) and … blood soup.

But was that a real memory, blood soup?

So, professional librarian and personal family heirloom keeper that I am, I did some research into my Finnish roots. I quickly found a soup recipe with dumplings. It was prepared from rye flour and reindeer blood (!) from northern Finland, where Taivalkoski is located. I went back to the grocery accounts — yep, “rye” was a frequent purchase for my family.

This lead fizzled, though, when I checked with Kent Randell, former archivist at the Finnish American Heritage Center in Hancock, Michigan. He didn’t doubt the purchase for blood, just that it was unlikely to have been used for soup. Kent then introduced me to Jim Kurtti, former director of the FAHC and current honorary consul to Finland, who gave me a list of books to review. I was in luck — one of Jim’s recommended titles, a translation of ethnologist Ilmar Talve’s “Finnish Folk Culture” — was in the Library’s collections.

I dug into this and came across his discussion of “festive fare.” He mentions that Easter day and the end of Lent were celebrated with blood sausage, called “verimakkara,” a dish that is made around much of the world. In Britain, they call it black pudding. In Latin America, it goes by morcilla. (The blood is gathered when the animal is bled at slaughter.) Variations are endless, but in a typical Finnish recipe, I learned, rye flour, grains and several spices are used to make a sausage. After it was cooked, Finns liked to serve it with lingonberry jam.

Did this hold up for my family history here in the U.S.? The account book noted that Juho bought “Easter eggs” a few days before buying the blood. Easter was, in turn, three days later. It certainly seemed plausible.

In the book “Odd Bits: How to Cook the Rest of the Animal,” author Jennifer McLagan provides some history about blood consumption in Nordic countries. In northern areas where food was scarce, blood provided a practical source of nourishment. Between 1866 and 1868, a famine killed about 8% of Finland’s population. When many people were trying to stay alive by eating pine bark bread, discarding nutrient-rich blood likely felt like throwing away the next meal.

Maybe this is why Finns popularized blood cakes (pancakes) called “veriohukainen.” Blood was the substitute for eggs in the recipe, holding the flour and milk together, while adding a dose of nutritious iron. It also, as you might expect, gave the cakes a dark red color.

It’s widely believed that Finns created this dish, so immigrants certainly didn’t leave it in the old country. In 1914, a Finnish domestic worker named Mina Walli wrote a dual language cookbook designed to teach other Finnish domestics how to cook so that they might increase their wages. “Suomalais-amerikalainen keittokirja” (“Finnish American Cookbook”) went through at least four printings. She included a recipe for blood pancakes.

We can agree it was a different era. There are three recipes on page 140. The first is for “Fried Tripe,” the second is for “Stewed Lungs” and then there’s “Blood Cakes.”

For ingredients, she calls for two cups of blood, two cups of milk, two eggs, ½ of an onion, four tablespoons of suet or butter, four tablespoons of rye flour, four tablespoons of white flour, ½ tablespoon of salt and a dash of thyme.

Then — what, you don’t want to know more?

While consuming blood remains taboo in many cultures who equate blood as the life source of the animal, McLagan writes that early Nordic peoples believed that the strength and other desirable qualities of the animal were transferred through consumption.

Whether such beliefs persisted into the modern era, or whether blood dishes were just a traditional taste of home on foreign shores, the recipes clearly made their way to the U.S. That solved the mystery for me. I closed the little grocery store account books and have decided to donate them to a regional archive, where anyone can access them for research or just out of curiosity. Meanwhile, looking at the photo of Juho, I notice it was taken in daylight, so he couldn’t have been a vampire. However, I don’t know what year the photo was taken, and sunshine as a vampire weakness is fairly recent addition to the folklore cannon, popularized with the 1922 German film “Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers