Library of Congress's Blog, page 36

February 14, 2022

Free to Use and Reuse: Aircraft!

All-Story Magazine, cover, Oct. 1908.Artist: Harry Grant Dart. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Library’s Free to Use and Reuse copyright-free prints and photographs are among the most popular items in the Library’s vast collections. They’re great images from days gone by and they’re yours for free! You can check out the pictures in travel posters, autumn and halloween, weddings, movie palaces and dozens more. You can download them, make posters for your home or wallpapers for your phone.

Let’s check out a few from our aircraft collection.

As the 1908 illustration above shows, we have a very liberal definition of “aircraft.” This contraption, with a nattily-attired couple purring through the heavens, appears to be akin to a two-seater convertible with wings, perched below a zeppelin. Our heroine has taken the wheel and her gentleman companion is, no doubt, mansplaining how to Fly This Danged Thing.

It’s not clear how high or fast they’re going, but nobody needs goggles and their hats are unbothered. She sensibly has her hands at 9 and 3 on the wheel and appears to be looking at the gauge in front of her. They’ve got a fancy brass headlight but … are they really going to flying that thing at night?

Stunt woman Lillian Boyer, performing “The Break Away” in 1922. Photo: Unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.

Next, it’s good to remember that it took human beings millions of years of existence to develop the airplane — and then about 15 minutes get out of them in midair. Welcome to those thrilling days of yesteryear, when barnstorming pilots fanned out over the country at festivals and county fairs, taking cash-paying passengers for a quick ride or performing death-defying aerial stunts.

This became a national phenomenon after World War I, when nearly all of the nation’s first military pilots trained on a Curtiss JN-4, a biplane nicknamed a “Jenny.” It had a 90 horsepower motor (less than most motorcycles today) and topped out at a daring 75 mph. After the war, the military sold surplus planes on the cheap. Pilots snapped them up. Barnstorming was born.

It didn’t take long for wing walkers to hop out of the cockpit and hang on to a strut or cables between the wings, producing gasps from crowds below. Lillian Boyer, a 20-year-old waitress from Nebraska, took exactly two flights to do this, as she most certainly did not want to remain in her seat and return her tray to the upright and locked position.

As crowds gathered at airfields, Boyer swooped past, walking on wings, hanging from them by a single hand and jumping from one plane to another — without a parachute or any sort of safety equipment. Sometimes she just hung onto a cable beneath the plane — with her teeth. Her real crowd pleaser was to stand up in a sports car tearing down a runway, reach up for a rope ladder dangling from her plane flying above, and climb up as it swooped higher in the sky. (On Youtube, you can see her do this on the backstretch of a horse racing track.) Headlines dubbed her Empress of the Skies. She performed hundreds of times across the Midwest and South during a seven-year career, until federal authorities shut down such stunts as unsafe. (Wing walker stunts were later revived at throwback shows, even in recent years. Deaths are rare, but still happen.)

“I don’t know if it was just lack of good sense, but I wasn’t afraid,” she said some 60 years after her heyday, when a reporter from Copley News Service caught up with her at an airfield near her home in San Diego. She was 82 then, in great spirits and out for a quick ride in a vintage biplane. She stayed in her seat the entire flight, the reporter noted.

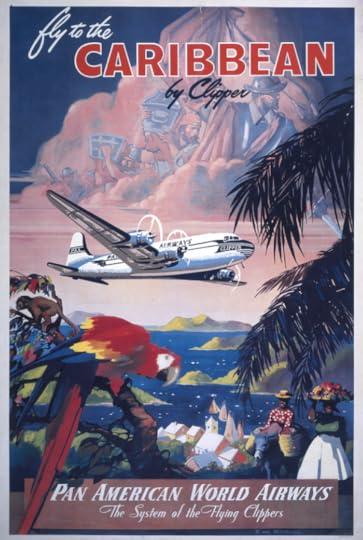

A Pan American travel poster from the late 1940s. Artist: Mark von Arenburg. Prints and Photographs Division.

Lastly, let’s remember the mid-century, the final days of the golden age of travel, when flying was something you dressed up to do. This Pan American poster captures that feel, presenting an alluring version of the Caribbean, though to no specific island. There’s more than a touch of colonialism featured as romance here, most notably the Spanish conquistadors magically in the rose-colored clouds. It was a world view that would shortly change.

The artist, Mark von Arenburg, was an ace at these sort of romantic travel posters, with the big block print, the plane soaring and a tropical locale beckoning. He makes great use of red here, as a bold pop against the azure blue.

The aircraft soaring past those clouds appears to be a Douglas DC-4. It was developed in the early 1940s, used extensively in World War II (particularly in the Berlin Airlift) and then made the switch to the civilian market. The planes were capable of transoceanic travel, but the cruising speed was about 230 mph, a little than half of what jets cruise at today. If flights were longer, at least passengers had leg room most travelers today would envy — in most configurations, only 44 passengers were on board, with four seats per aisle. I know, i know — there was no middle seat. Talk about the travel of your dreams.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

February 8, 2022

Black History Month: Family Health, Hidden in DNA

The Whitney family — parents Joyce and Harvey Sr. at each end; daughters Wanda and Donna, left to right.

This is a guest post by Wanda Whitney, head of the History & Genealogy Section. Candice Buchanan, a reference librarian in the section, contributed.

Working in the History and Genealogy Section of the Library, we routinely hear stories of surprising revelations that lie in the often-tangled roots of family histories, especially now with the growing popularity of DNA testing. I had already experienced this firsthand when I decided to take a DNA test. Still, I was shocked at the news it revealed about me and my family.

It wasn’t some unknown relative popping up in a previous century, a sibling I didn’t know I had, or that I was adopted, although those types of discoveries happen all the time. Instead, it was something that had health implications for me, my parents and my children — a genetic mutation for a hereditary type of anemia.

I thought, “What does this mean for me? For my parents and siblings, cousins, our children?”

This type of medical revelation is important to all families, but particularly for Black ones, as so many of our histories are lost and buried through slavery and its long, ugly legacy. Medical histories can be even more difficult to tease out, and this lack of knowledge can contribute to gaps affecting health outcomes for Black families. Since many times we know less about our backgrounds than other Americans, it’s a good thing to explore during Black History Month. It can be life-changing to talk to our parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins about our health history, too.

I already knew about the sickle cell anemia trait that several of my relatives, including my mother, carried. But I was floored to see DNA test results that indicated I carried a genetic mutation linked to G6PD deficiency. This is a condition that affects the health of red blood cells and can lead to anemia when one is exposed to certain medications, foods or infections. G6PD deficiency is quite common among people of African descent. Since this gene is located on the X chromosome, and females have two, I am not at high risk for developing symptoms because my second X chromosome doesn’t have the mutation. Men only have one X chromosome, so if they inherit the mutation from their mother, they are most at risk.

I read all I could about the mutation and what it might mean for my family and had several conversations with my doctors. I do not have G6PD deficiency, but I could have passed the genetic mutation to my children. I told them about the possibility and they ultimately decided that, since the condition does not cause serious symptoms for many people, they would not get tested.

I also told my parents. My father was fascinated. He has always loved delving into family history; learning about our health was just an extension of this. My mother was much more reluctant, but they went ahead with testing. The results showed that that I had inherited the mutation from her. We also were left with the knowledge that she carries two different mutations — one linked to sickle cell anemia and the other to G6PD deficiency.

Explaining the results to her did not go well. In the end, my father and I talked about what the mutation is and what it may mean for us. But my mother and I haven’t discussed it again. Communicating unexpected results when researching family histories can be tricky.

There is not a single catch-all solution to handling unexpected discoveries in the course of genealogical research. Every situation is unique and often deeply personal. One way to prevent unpleasant results is to keep in mind that anything is possible.

In the end, family history is human history. We must enter it with open hearts and minds. We must do our part to complete exhaustive research, weigh the evidence, analyze the results, and present the facts in as well rounded, honest and contextual a manner as possible. Privacy and ethical considerations determine what we share, as well as how and whom to share it. For guidance, support, and consideration, subject specialists at the Library have created resource guides and presentations on these topics.

Family Secrets: Emotional Fallout from Genealogical ResearchGenetic Genealogy: DNA and Family HistoryYou can also use Ask a Librarian to submit questions and discuss your research.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

February 7, 2022

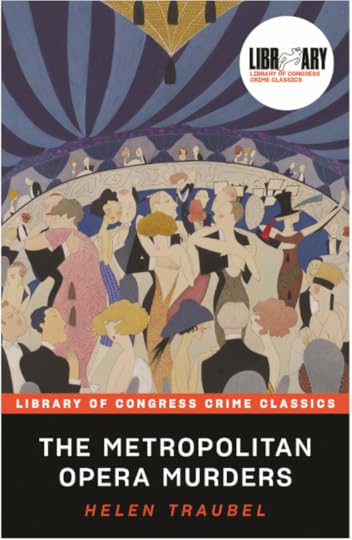

“The Metropolitan Opera Murders” — Crime Classics Latest

Helen Traubel as Brünnehilde in “Die Walküre.” Helen Traubel Papers. Music Division.

This is a guest post by Zach Klitzman, the editorial assistant in the Library’s Publishing Office .

As soprano Elsa Vaughn sings the role of Brünnehilde during the second act of Richard Wagner’s “Die Walküre,” she notices that prompter Rudolf Salz is making funny faces. Then he starts convulsing, grabs his throat, and falls down the steps to the orchestra pit. He’s dead!

So begins “The Metropolitan Opera Murders,” the latest entry in the Library’s Crime Classics series. (Available at all booksellers and via the Library of Congress shop.) Launched in April 2020, the critically acclaimed series features some of the finest American crime writing from the 1860s to the 1960s. Drawn from the Library’s collections, each volume includes the original text, an introduction, author bio, notes, recommendations for further reading and suggested discussion questions from mystery expert Leslie S. Klinger.

The author in this case was none other than Helen Traubel, a star soprano of the era, with the help of ghostwriter Harold Q. Masur. She knew the material well, having played Brünnehilde herself. Her only novel, “Metropolitan” offers an insider’s view of the world’s most famous opera company and the high drama that occurs both onstage and behind the scenes.

Originally published in 1951, the novel features a memorable cast of characters who might have played a role in Salz’s death. It seems as if the poison Salz ingested was meant to kill Vaughn, the soprano. And it’s not the only recent attempt to harm her: ground glass in her cold cream, toppling scenery, flowers treated to induce an allergic reaction.

Detective-Lieutenant Sam Quentin must figure out who would want her dead. Is it her understudy, the ambitious Miss Hilda Semple? What do opera financier Stanley DeBrett and his family have to do with the murder, if anything? Or was the poison truly intended for Salz, an embittered, formerly world-famous Wagnerian tenor, now reduced to coaching other singers? When a second murder takes place, Vaughn can no longer deny that she may be a target.

“The Metropolitan Opera Murders.” Cover art is adapted from a drawing by Anne Harriet Fish. Prints and Photographs Division.

Traubel, whose papers are held by the Library, lived a colorful life, though it did not involve murder. Born in St. Louis in 1899, she first sang with the St. Louis Symphony in 1923. She made her debut at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City in 1937 and worked there for sixteen years, taking over as the primary soprano for Wagnerian roles in 1941. As one of the most famous opera singers in the country, she collaborated with Leonard Bernstein on a concert version of Wagner’s “Tristan und Isolde” in 1949. She even gave first daughter Margaret Truman singing lessons. (Truman herself would later write a series of mystery novels, including “Murder at the Library of Congress.”)

After performing at USO shows during World War II, Traubel believed that she could reach a larger audience by performing non-operatic works. She began singing in night clubs and appearing on television, often as a straight woman alongside comedian Jimmy Durante. She even appeared in an abridged production of “The Mikado” with Groucho Marx. The manager of the Met, Rudolph Bing, felt that these appearances cheapened the institution. But Traubel did not want to give up her popular acts, so she declined to renew her Metropolitan Opera contract in 1953.

The bet paid off.

In her post-Met era, Traubel appeared in films like “Deep in My Heart” and debuted on Broadway in the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical “Pipe Dream.” In 1959, she published an autobiography, “St. Louis Woman.” Two years later, she sang “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” at a gala the night before John F. Kennedy’s inauguration. She received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and had a variety of roses named after her.

Helen Traubel in 1939. Photographer: Abresch. Charles Jahant Collection. Music Division.

Thanks to her success, Traubel became a minority owner of her hometown St. Louis Browns baseball team, but could not be the fan she wanted to be. The dustjacket to the original edition of “Metropolitan” reported, “One of the sorrows of her life is that she cannot go to many games because she roots so intensely and so vocally that she might damage her voice.”

When Traubel died in 1972, her husband and former business manager, William Bass, donated her papers to the Library. The collection documents her career through correspondence, photographs, scripts, scrapbooks, and her annotated music scores and orchestra library. Also included: a box of materials related to “Metropolitan,” including a draft of the book in German.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

February 4, 2022

The Case that “Gutted” Rosa Parks

The Montgomery bus boycott that Rosa Parks helped ignite, plan and carry out in 1955 was the opening salvo in what became one of the most influential social movements in the 20th century. It triggered not only the modern civil rights movement for Black Americans, but also rights-based movements for so many others — Asians, Hispanics, women, LGBTQ+ and so on. Such rights and social expectations have now become part of American society, and their influences have spread abroad.

Parks’ papers are at the Library, and the exhibit that features them, “In Her Own Words,” is still on display. Timed-entry tickets are free.

But her activism began long before that Dec. 1, 1955, day that she refused to give up her seat on the bus for a white man. The incidents that helped set the steel in her spine were the sexual violence of whites against Blacks that were common to the Jim Crow South.

Parks and her husband, Raymond, worked on the Scottsboro Boys case in 1931, in which a group of nine young Black men were falsely accused for raping two white women in Alabama. In 1944, she investigated the gang rape by white men of a young black woman named Recy Taylor, also in her home state.

But the case that “guts her the most,” according to Jeanne Theoharis, author of “The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks,” was the 1952 arrest of a Black teenager named Jeremiah Reeves, who was accused of raping a young white woman with whom he was having a consensual relationship. He was 16 when arrested and 22 when executed.

“[Police] actually put him in the electric chair at Kilby prison and told him that if he didn’t confess, he would be electrocuted on the spot, so he gave this false confession,” said Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, a longtime friend of Parks. “She began writing letters and trying to organize around trying to block that execution, got Dr. (Martin Luther) King involved. And it didn’t succeed and he was executed. She would tell me how devastating that was, and how it broke her heart.”

You can see the full story in the video above. On this, the 109th anniversary of her birth, it’s important to remember that Rosa Parks is a national heroine not because her activism was always a success. It’s because she kept pushing, for years and then for decades, even when it was not.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

February 1, 2022

Black History Month: Black Military History Crowdsourcing

Black “Buffalo soldiers” of the 25th Infantry, some wearing buffalo robes, Ft. Keogh, Montana. 1890. Photo: Christian Barthelmess. Gladstone Collection. Prints and Photographs Division.

Juba Freeman was just that — a free man — when he fought for the Continental Army in 1782, and his pay vouchers document that Black Americans were fighting for the national cause from the beginning. John S. Rock was a prominent teacher, doctor, orator and abolitionist in Boston during the mid 19th-century, but he also strove to become the first Black attorney admitted to practice before the U.S. Supreme Court.

“We have now a great and good man as our Chief Justice,” he wrote to a supporter on Dec. 13, 1864, as the Civil War still raged, “and with him I have no doubt my color will not be a bar to my admission.”

He was correct.

Black History Month at the Library is kicking off with a fascinating way for you to get involved in hands-on history — transcribing hundreds of items such as these in the William A. Gladstone Afro-American Military Collection.

It’s the latest By the People project, the Library’s crowdsourcing effort that has already transcribed some of the papers of George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, Clara Barton, Susan B. Anthony, Walt Whitman, Rosa Parks, John and Alan Lomax, Mary Church Terrell and many more.

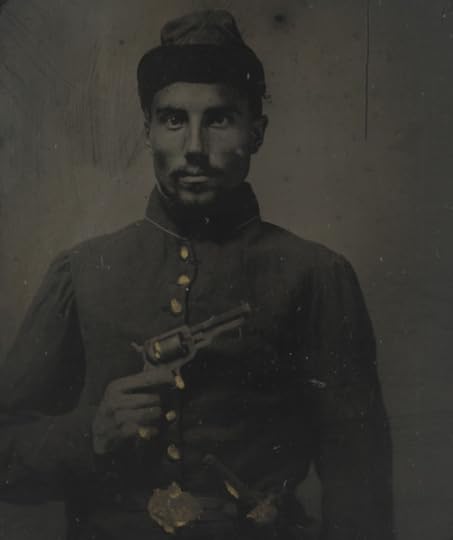

Gilbert Montgomery, 4th United States Cavalry, in the Civil War. Gladstone Collection. Prints and Photographs Division.

Gladstone was a private historian and collector whose principal interest was Black soldiers in the Civil War, but he also collected items about Black military service from 1773 through World War I. (He collected other publications that stretched to 1987.) The Library purchased the collection from him in 1995. While photographs and documents are online, the text has not been transcribed, which means they can’t be easily accessed by researchers, students and historians.

If you volunteer, you’ll be looking at correspondence, pay vouchers, orders, muster rolls, enlistment and discharge papers, receipts, contracts, affidavits, tax records and so on. The Revolutionary War items are primarily pay vouchers to Black soldiers in Connecticut who served in the Continental Army. World War I is represented in part by the papers of Lt. Edward Goodlett of the 370th Infantry, 93rd Division. There’s also the Honor Roll from the Harlem Hellfighters, the 369th Infantry Regiment that spent more time in combat than any other unit. In their off hours, they put together a jazz band that helped bring that world-changing music to France.

There are also printed copies of 19th-century century speeches and writings on slavery, government orders, broadsides, and 20th-century booklets and journal articles.

Many of the documents reveal a complicated, discriminatory history that targeted these military members. Juba Freeman, for example, was not a free man when he first enlisted in 1777. He was listed only as “Juba,” and half his pay went to his enslaver, perhaps to purchase his freedom, according to research by the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition (GLC) and the Center for Media and Instructional Innovation at Yale University.

There was also the famed Massachusetts 54th Regiment, the all-Black unit which fought in the Civil War and was the subject of the Oscar-winning 1989 film, “Glory.” The U.S. military did not begin to integrate until President Harry S Truman signed Executive Order 9981 on July 16, 1948 — although, as recent headlines point out, that discriminatory history is with us still.

An unidentified Black soldier in the Union Army poses with his pistol during the Civil War. Photographer unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

January 28, 2022

Protest Preserved: Signs from D.C.’s Black Lives Matter Memorial Fence

Some of the 78 sections of the protest fence on June 19, 2020. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.

It was a year ago this week that the Black Lives Matter signs came down from the Lafayette Park fence where they had garnered national attention as a rallying point for protests for nearly a year. The park, across the street from the White House, had been fenced off to keep protesters at a distance. Protestors, in turn, made artwork of the fence.

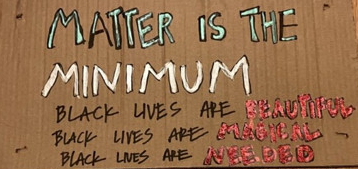

“I Can’t Breathe.” “Matter is the Minimum.” “Say Their Names.” “Fight the Power.”

There were hundreds of signs, protesting the police killings of George Floyd and others, as well as the nation’s long history of racial injustice. Some signs lasted days. Some lasted months. Some were torn down by counter-protestors and replaced. When volunteers removed the signs on Jan. 30, 2021, there were some 800 of them. A number of those have since been collected by the Library and Howard University. A small selection was exhibited in Tulsa, Oklahoma, last year as part of the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre. A digitization project is underway at the Enoch Pratt Free Library in Baltimore and the D.C. Public Library that will ultimately make them all available online.

You can see 33 of them now on the Library’s website.

“The World is Watching.” Creator unknown.

The Library’s Prints and Photographs Division has a long history of collecting protest art, both from the steady stream of protests along the National Mall and from across the world. The largest single example is the Yanker Collection of Political and Propaganda Posters, which features thousands of examples, mostly between the 1920s and 1970s. The Library preserves material from nationally significant protests, the most famous of which may be 1963’s March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which culminated in Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

Protestors used mass-produced signs during the 1963 March on Washington. Photo: Stanley Tretick. LOOK Magazine Photograph Collection. Prints & Photographs Division.

In this case, the Library’s collection effort was spearheaded by Aliza Leventhal, head of the technical services section in the Prints and Photographs Division, who visited the Lafayette Park site daily for eight months. She became entranced by what she saw as an evolving work of art, with signs being moved and rearranged to speak to one another.

“The signs ranged from crafted works of art either brought from home or created on the site, as well as scrap pieces of paper with hastily written messages,” she said. “Every day new signs were showing up, another person sharing their story and adding valuable layers to the ongoing conversation on the fence.”

“Matter is the Minimum.” Creator unknown.

The fence’s de facto curator was Nadine Seiler, an activist who took on care and maintenance of the site. She was joined by Karen Irwin, another activist. The pair went so far as to sleep at the site to prevent vandalism overnight. They eventually donated a group of posters to the Library to ensure broad public access.

“I was more drawn to the humorous protest signs,” Seiler said. “I guess it’s the vein of, ‘If I don’t laugh, I’ll cry.’ For me, it’s taking tragedy of our dehumanization and lightening it so it’s not so heavy on my psyche.”

Protests ebbed after Joe Biden was elected president, and protestors decided to remove the signs a year ago this week. Before it was removed, however, activists photographed each panel to capture the final positions of signs. Volunteers then took 800 signs off the fence, preserving nearly all of them.

They were gone from their spot in the national limelight, but headed for preservation and public access in the national library.

Untitled by Luther Wright. Prints and Photographs Division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

January 24, 2022

Trailblazing American Women on Quarters

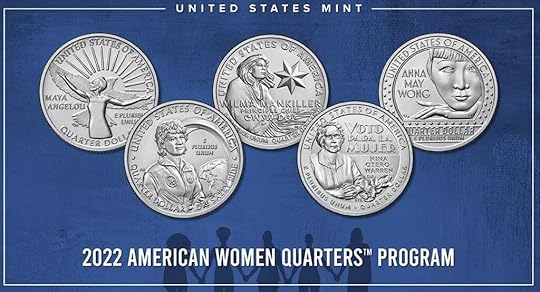

The U.S. Mint quarters saluting women trailblazers for 2022.

Maya Angelou broke ground as a multifaceted author, poet, actress, recording artist and civil rights activist, while Adelina “Nina” Otero-Warren left an indelible mark in New Mexico’s suffrage movement. This year, both are among five trailblazing women to appear on the U.S. quarter — on the flip side from George Washington — for the first time, so keep an eye on your pocket change and get your coin collector boards ready!

Angelou is the first Black woman to be featured on U.S. currency. Her coins will begin circulating this month. Otero-Warren is the first Latina to do so, with her coin appearing in August. Both will help ensure that future generations learn about these remarkable women’s place in American history.

“It is huge to have her (Otero-Warren) on the coin,” Anna M. Nogar, an associate professor of Hispanic Southwest Studies at the University of New Mexico, said in an interview. “She is a very significant figure in New Mexico. She worked so hard for women’s suffrage ̶ that was extremely important ̶ but she also spearheaded efforts in other parts of the political sphere.”

Through its American Women Quarters Program, established by a 2020 bill, the U.S. Mint is paying tribute to women who have contributed to social advancement in this country. The list of honorees for this year’s rollout includes Sally Ride, the first American woman astronaut in space; Wilma Mankiller, the first female principal chief of the Cherokee Nation; and Anna May Wong, the first Chinese American film star in Hollywood.

The Library recognizes women trailblazers, including these and many others, in its collections, events and exhibitions. Two current exhibitions are “Shall Not Be Denied,” about the campaign for women’s voting rights, and “In Her Own Words,” about the life of Rosa Parks. Parks is featured in a short documentary. Crowdsourcing campaigns to digitize the Library’s papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Mary Church Terrell and Susan B. Anthony and others have drawn hundreds of thousands of volunteers.

Angelou, longtime friends with Parks, was already a well-known Broadway performer, singer and civil-rights activist when her 1969 memoir “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings” became an instant landmark in American literature. In raw but elegant prose, she described her birth in Missouri and her poverty-stricken, turbulent youth in segregated Arkansas. When she was still a child, she was raped by a family friend; her uncles beat the man to death.

She took her title from the refrain of a Paul Laurence Dunbar poem, “Sympathy,” composed while he worked at the Library of Congress in the late 1890s. Dunbar’s job was to retrieve reserved books that were kept behind iron grates, which were referred to as “cages.” The stacks became hot and oppressive during the summer months, and Dunbar’s poem captured their sense of being a prison enclosure.

In Angelou’s use, the title is a metaphor for the wide arches of racism and misogyny that shackle Black women as they struggle to live free, full lives. The book became a perennial classic. It’s still taught in schools.

She went on to pen more than 30 bestselling titles of poetry, essays and memoirs. Her popularity soared when she recited “On the Pulse of Morning” at Bill Clinton’s first presidential inauguration in 1993, becoming the first Black woman to write and present a poem for such an occasion. She was later awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama in 2011. (Her autobiographical works are available in Braille through the National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled.)

She died in 2014 at the age of 86.

U.S. Rep. Barbara Lee, D-California, who co-introduced the bipartisan bill establishing the new coin program, said in a recent statement it was important to honor “these phenomenal women, who more often than not are overlooked in our country’s telling of history.”

“If you find yourself holding a Maya Angelou quarter, may you be reminded of her words, ‘Be certain that you do not die without having done something wonderful for humanity,’” said Lee.

Meanwhile, a 2020 Library of Congress exhibit noted that Otero-Warren’s militancy in the women’s suffrage movement was crucial in New Mexico, where she was tapped in 1917 by Alice Paul, a leading suffragist, to head the state chapter of the Congressional Union, forerunner of the National Woman’s Party.

Otero-Warren descended from wealthy and influential New Mexican settlers, but her family life was marked by violence: When she was still a toddler, a squatter shot her father to death. Still, her mother soon remarried and the family’s ranch prospered.

As an activist, she garnered support for a woman’s right to vote among Spanish- and English-speaking communities. Otero-Warren proved to be an ideal activist precisely because of her background. Her push for an inclusive environment and for bilingual materials helped widen the suffragists’ reach and attracted Latino support. She spearheaded efforts to have New Mexico ratify the19th Amendment in 1920.

She was an early supporter of bilingual education despite a federal English-only mandate then in place, serving as the first female school superintendent in Santa Fe County between 1918 and 1929. She promoted policies to empower rural Hispanic and Native American communities, according to biographers. In 1921, she was the first Latina to win the nomination for a Republican seat for the House of Representatives but lost the race by a razor thin margin in the general election.

Otero-Warren died in 1965, but her legacy is still alive in New Mexico. There’s a mural detailing her activism for suffrage in downtown Albuquerque, and there is a popular corrido, a narrative ballad, about her father’s murder. It resonates with people experiencing dispossession, said Nogar, the UNM professor.

From now through 2025, the mint will issue five new reverse designs each year, celebrating women’s accomplishments and contributions in fields like women’s suffrage, civil rights, abolition, government, humanities, science and the arts.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

January 20, 2022

Lionel Richie, 2022 Gershwin Prize Honoree: A Quick Look

Lionel Richie, the Alabama-born songwriter with a smooth voice and a deft touch for the romantic ballad, is the 2022 Library of Congress Gershwin Prize for Popular Song honoree.

Richie, 72, has sold more than 125 million albums, co-wrote one of the biggest singles in history, won an Oscar and, after a career that started in the late ’60s, is still a star of network television, as a judge on ABC’s “American Idol.” He wrote No. 1 songs for 11 consecutive years, was a star with the Commodores, on his own, and as a mellow voice on any number of hit duets.

“In so many ways, this national honor was made for Lionel Richie, whose music has entertained and inspired us — and helped strengthen our global connections,” said Carla Hayden, the Librarian of Congress. “Richie’s unforgettable work has shown us that music can bring us together. Even when we face problems and disagree on issues, songs can show us what we have in common.”

“This is truly an honor of a lifetime, and I am so grateful,” Richie said. “I am proud to be joining all the other previous artists, who I also admire and am a fan of their music.”

“Endless Love,” one of his biggest duets, was the eponymous hit from the 1981 film, which he memorably sang with Diana Ross. The song was No. 1 on Billboard charts for more than two months. His “Say You, Say Me,” a No. 1 hit from the 1985 film “White Nights,” won the Academy Award for Best Original Song.

But as anyone who had FM radio knows, there were plenty more. “Three Times a Lady,” “Still,” and “Easy,” all with the Commodores. Then, a flurry of solo hits: “All Night Long.” “Hello.” “Penny Lover.” “Dancing on the Ceiling.” “Truly.” He wrote “Lady” for country artist Kenny Rogers in 1980. It became the one of biggest songs in Rogers’ career. Richie recorded it on his own later in the decade, and it was a hit again.

But it was another cooperative effort, this one with Michael Jackson, that turned into a massive international hit for charity. Richie and Jackson wrote “We Are the World,” for USA for Africa, a fundraising effort to address a devastating famine in northeast Africa, principally Ethiopia. Along with Harry Belafonte, they recruited a cast of all-star talent to perform it, including Ross, Rogers, Stevie Wonder, Bette Midler, Ray Charles, Bob Dylan, Tina Turner, Bruce Springsteen, Cyndi Lauper, Willie Nelson, Paul Simon, Dionne Warwick, the Pointer Sisters and so on. It sold more than 20 million copies and raised more than $63 million.

Bestowed in recognition of the legendary songwriting team of George and Ira Gershwin, the Gershwin Prize recognizes a living musical artist’s lifetime achievement in promoting the genre of song as a vehicle of entertainment, information, inspiration and cultural understanding. The honoree is selected by the Librarian — in consultation with a board of scholars, producers, performers, songwriters and other music specialists. Previous recipients are Nelson, Simon, Wonder, Sir Paul McCartney, songwriting duo Burt Bacharach and the late Hal David, Carole King, Billy Joel, Smokey Robinson, Tony Bennett, Emilio and Gloria Estefan, and Garth Brooks.

Richie will receive the Gershwin Prize at an all-star tribute in Washington, D.C., on March 9. PBS stations will broadcast the concert — “Lionel Richie: The Library of Congress Gershwin Prize for Popular Song” — at 9 p.m. ET on Tuesday, May 17, and on PBS.org and the PBS Video App as part of the co-produced Emmy Award-winning music series. It will also be broadcast to U.S. Department of Defense locations around the world via the American Forces Network.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

January 18, 2022

Researching Nannie Helen Burroughs: Danielle Phillips-Cunningham

Danielle Phillips-Cunningham. Photo courtesy of author.

Danielle Phillips-Cunningham

Danielle Phillips-Cunningham teaches multicultural women’s and gender studies at Texas Woman’s University and writes about race and women’s labor history. She is writing a book about Nannie Helen Burroughs, who founded the National Association of Wage Earners, a little-known but important Black women’s labor organization. Phillips-Cunningham has researched the book in the Library’s Nannie Helen Burroughs papers.

Who was Nannie Helen Burroughs?

Burroughs was an African American labor leader, suffragist, educator and civil rights organizer born in Orange, Virginia, in 1879. In 1909, she founded the National Trade School for Women and Girls (NTS). Located in Washington, D.C., the NTS served as a trade school for Black girls and young women throughout the African diaspora until the 1960s.

Her primary mission in creating the NTS was to improve the working conditions of Black domestic workers. With formal education in domestic science, Burroughs believed, Black women could demand higher wages from household employers and could be more selective about the homes where they worked.

Burroughs also wanted Black women and girls to have the option of becoming entrepreneurs and pursuing a variety of professions where they were underrepresented because of discriminatory hiring practices. She created an extensive school curriculum that included courses in cooperative farming, stenography, printing, barbering and public speaking, to name a few.

What inspired you to tell Burroughs’ story, and how are you documenting it?

I was blown away when I discovered that Burroughs established the National Association of Wage Earners (NAWE) in 1921, one of the first national Black women’s labor organizations in U.S. history. The organization operated like a labor union and had an extensive membership of domestic workers, clubwomen, educators, pastors, insurance agents, beauticians and many other workers from across the country who fought for labor rights for Black domestic workers.

I am documenting Burroughs’ history for a wide range of people to learn about her work and possibly become inspired to research the Burroughs papers at the Library for themselves.

While writing my book, I have published an op-ed about Burroughs in the Washington Post.

Nannie Helen Burroughs in a portrait made between 1900 and 1920. Photographer unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.

What do you most want to let people know about Burroughs?

Nannie Helen Burroughs should be a household name. There is only one surviving building of the NTS, and her history could be lost if we do not continue to tell her story.

Burroughs contributed extensively to the labor and civil rights movements through her school, writings, speeches and leadership in women’s organizations. She worked on multiple fronts to push for Black women’s access to living wages, quality education, voting, safe living and working conditions and protection from lynchings and sexual assault.

While presiding over the NTS and NAWE, she took on other important roles as well, including as co-founder and president of the National League of Republican Colored Women, a women’s voting group that organized against lynchings and Jim Crow laws. [https://www.loc.gov/exhibitions/women...]

What are a couple favorite discoveries from the Burroughs papers?

Thousands of people from around the world came to Washington, D.C., to visit Burroughs’ remarkable school. I was heartened to see the names of professors from my alma mater, Spelman College, in an NTS guest book from the early 1910s. I later learned that Burroughs regarded Spelman as a model for her own school. I also found NAWE membership cards from professors of the Atlanta University Center, a group of historically Black colleges and universities that includes Spelman College.

Another favorite gem is the subscriber lists of The Worker, a paper that Burroughs started in the printing department of her school to circulate her writings about labor organizing, civil rights and religion. People from Cuba, Jamaica and large bustling cities and small rural towns of every single U.S. state subscribed to her paper.

Do you have any advice for other researchers on navigating the Library’s collections?

Get to know the archivists! I’ve found that many people at the Library have been working there for several years and have deep knowledge about the collections that you cannot get from secondary sources.

I am so glad that I met Patrick Kerwin in the Manuscript Reading Room during my first visit to the Library. Over the years, he has directed me to sources at the Library that I did not readily see online or in finding aids. He also suggested that I contact people who are connected to the Burroughs papers and whose names are not mentioned in published articles or books that cover Burroughs’ history.

Resplendent in their white dresses, nine students of the National Training School for Women and Girls pose for an unknown photographer. Taken between 1911-1920. Prints and Photographs Division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

January 13, 2022

Mystery Photographer: Who Is the Altamont Filmmaker?

Mick Jagger (in red) and Keith Richards (in shades and white shirt) at the Altamont concert. Photo: Image from newly discovered home video.

This is a guest post by Mike Mashon, head of the Moving Images Section.

We’ve been gratified by the international reaction to our having discovered a never-before-seen home movie of the 1969 Altamont concert, one of the darker hallmarks of the 1960s.

That story, picked up by several national media outlets, has triggered an international mystery: Who was the heroic filmmaker? Who shot this remarkable 26 minutes of footage, from right at the stage, dropped it off for processing but never picked it up? Is it possible, more than half a century later, to identify that person?

Possibly. We’d love your crowdsourcing help. Ready?

First, more than 300,000 people showed up for the free, day-long show, featuring Carlos Santana, Jefferson Airplane, the Flying Burrito Brothers and, of course, the Rolling Stones. The concert was the subject of “Gimme Shelter,” the Maysles brothers 1970 documentary. There was news coverage, too, and lots of the young fans took their cameras, so there is plenty of documentation of who was on and near the stage. Despite all that, there is no wide-shot film of the stage for the entire concert.

The images we have reveal four primary contenders, all appearing to be young white men. Here are our limitations: We have yet to come across an image or footage that show all of them at once, which might us identify the filmmaker by matching his position with the home footage. The images of the filmmakers are not entirely clear, and in one instance is just the back of the guy’s head. There may be images of one of these men on the home footage itself — we haven’t verified that yet — which would rule that person out as our filmmaker.

Still, we have some good clues.

Mystery filmmaker #1. Image from “Gimme Shelter,” documentary by the Maysles brothers.

Filmmaker #1: Blue Shirt Man, seen here in a screen grab from the Maysles film. He’s in the correct place for the daytime scenes (stage right, house left), so that makes him a solid contender. But our film experts note he’s using a Keystone K-27 camera that didn’t shoot Super 8 film. The home movie footage is Super 8. So, unless he was working with two cameras, he’s not our guy. Nice smile, though!

Mystery filmmaker #2.

Filmmaker #2: Brown Jacket Man. He’s in the correct place, too, and appears to be using a Super 8 Kodak Instamatic camera. Right camera, right place, right time. He checks out. There’s nothing we’ve seen to disqualify him.

Mystery filmmaker #3.

Filmmaker #3: Green Shirt Man. This gentleman is using a Super 8 camera—a Canon 318, we think — so he definitely makes the first cut. But he appears to be camped out at center stage. All of the daytime footage in our mystery video is shot from stage right. That apparently rules him out … unless there were two cameramen and his footage got separated from our film. See below for more on this theory.

Mystery filmmaker #4. Screen image from “Gimme Shelter.”

Filmmaker #4: Night Shooter. This guy, with the beard and blue shirt at the bottom left, appears in this, another shot from “Gimme Shelter.” He’s shooting with a Super 8 camera, a Technicolor Super V, which could have shot our footage. He’s at center stage, just in front of Stones guitarist Keith Richards. This is a different position from where the daytime footage was shot, but it roughly matches our nighttime footage. Can’t rule him out.

So there you have it. The footage is in two reels. It was dropped off at Palmer Films in Los Angeles and never picked up. Collector Rick Prelinger bought all of Palmer’s stock when they went out of business and eventually donated it to the Library as part of his vast collection.

Now, as some of you have theorized, it’s possible that the two reels were shot by different people – say, two or more guys on assignment for an as-yet-unknown client – and turned their film into Palmer for processing. The client, in this scenario, is the one who never picked it up.

Or, possibly, there was much more footage shot for this client, by multiple filmmakers, and said client picked up all of it … except for our two orphan reels, which had gotten separated from the rest of the footage. (In this scenario, yes, that would mean there’s a heck of a lot more Altamont footage out there that’s still never been seen, presuming it still survives. Also possible it was thrown away or lost years ago.)

At the moment, it’s our best guess that our mystery man is #2, Brown Jacket Man with the Instamatic. He’s in just the right spot working with just the right camera. As luck would have it, he’s the only one whose face we can’t see.

That’s it from us. Put your thoughts in the comments, identifying each guy by the filmmaker’s number, one through four. We’ll track down any reasonable ideas, and thank you in advance.

Meanwhile, we hope you’ll check out some of the other titles in the National Screening Room. They’re not as buzzy as this, but they’re still fascinating. And your friendly national film preservation institution encourages you to preserve your own home movies. You never know what they might turn up.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers