Library of Congress's Blog, page 37

January 13, 2022

Mystery Photographer: Who Is the Altamont Cameraman?

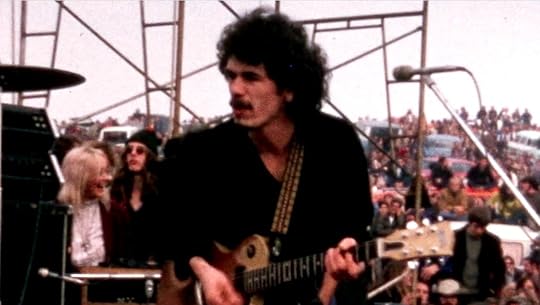

Mick Jagger (in red) and Keith Richards (in shades and white shirt) at the Altamont concert. Photo: Image from newly discovered home video.

This is a guest post by Mike Mashon, head of the Moving Images Section.

We’ve been gratified by the international reaction to our having discovered a never-before-seen home movie of the 1969 Altamont concert, one of the darker hallmarks of the 1960s.

That story, picked up by several national media outlets, has triggered an international mystery: Who was the heroic cameraman? Who shot this remarkable 26 minutes of footage, from right at the stage, dropped it off for processing but never picked it up? Is it possible, more than half a century later, to identify that person?

Possibly. We’d love your crowdsourcing help. Ready?

First, more than 300,000 people showed up for the free, day-long show, featuring Carlos Santana, Jefferson Airplane, the Flying Burrito Brothers and, of course, the Rolling Stones. The concert was the subject of “Gimme Shelter,” the Maysles brothers 1970 documentary. There was news coverage, too, and lots of the young fans took their cameras, so there is plenty of documentation of who was on and near the stage. Despite all that, there is no wide-shot film of the stage for the entire concert.

The images we have reveal four primary contenders, all appearing to be young white men. Here are our limitations: We have yet to come across an image or footage that show all of them at once, which might us identify the cameraman by matching his position with the home footage. The images of the cameramen are not entirely clear, and in one instance is just the back of the guy’s head. There may be images of one of these men on the home footage itself — we haven’t verified that yet — which would rule that person out as our cameraman.

Still, we have some good clues.

Mystery cameraman #1. Image from “Gimme Shelter,” documentary by the Maysles brothers.

Cameraman #1: Blue Shirt Man, seen here in a screen grab from the Maysles film. He’s in the correct place for the daytime scenes (stage right, house left), so that makes him a solid contender. But our film experts note he’s using a Keystone K-27 camera that didn’t shoot Super 8 film. The home movie footage is Super 8. So, unless he was working with two cameras, he’s not our guy. Nice smile, though!

Mystery camerman #2.

Cameraman #2: Brown Jacket Man. He’s in the correct place, too, and appears to be using a Super 8 Kodak Instamatic camera. Right camera, right place, right time. He checks out. There’s nothing we’ve seen to disqualify him.

Mystery cameraman #3.

Cameraman #3: Green Shirt Man. This gentleman is using a Super 8 camera—a Canon 318, we think — so he definitely makes the first cut. But he appears to be camped out at center stage. All of the daytime footage in our mystery video is shot from stage right. That apparently rules him out … unless there were two cameramen and his footage got separated from our film. See below for more on this theory.

Mystery cameraman #4. Screen image from “Gimme Shelter.”

Cameraman #4: Night Shooter. This guy, with the beard and blue shirt at the bottom left, appears in this, another shot from “Gimme Shelter.” He’s shooting with a Super 8 camera, a Technicolor Super V, which could have shot our footage. He’s at center stage, just in front of Stones guitarist Keith Richards. This is a different position from where the daytime footage was shot, but it roughly matches our nighttime footage. Can’t rule him out.

So there you have it. The footage is in two reels. It was dropped off at Palmer Films in Los Angeles and never picked up. Collector Rick Prelinger bought all of Palmer’s stock when they went out of business and eventually donated it to the Library as part of his vast collection.

Now, as some of you have theorized, it’s possible that the two reels were shot by different people – say, two or more guys on assignment for an as-yet-unknown client – and turned their film into Palmer for processing. The client, in this scenario, is the one who never picked it up.

Or, possibly, there was much more footage shot for this client, by multiple cameraman, and said client picked up all of it … except for our two orphan reels, which had gotten separated from the rest of the footage. (In this scenario, yes, that would mean there’s a heck of a lot more Altamont footage out there that’s still never been seen, presuming it still survives. Also possible it was thrown away or lost years ago.)

At the moment, it’s our best guess that our mystery man is #2, Brown Jacket Man with the Instamatic. He’s in just the right spot working with just the right camera. As luck would have it, he’s the only one whose face we can’t see.

That’s it from us. Put your thoughts in the comments, identifying each guy by the cameraman’s number, one through four. We’ll track down any reasonable ideas, and thank you in advance.

Meanwhile, we hope you’ll check out some of the other titles in the National Screening Room. They’re not as buzzy as this, but they’re still fascinating. And your friendly national film preservation institution encourages you to preserve your own home movies. You never know what they might turn up.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox

January 10, 2022

Jason Reynolds: Grab The Mic: Welcome to 2022

Ahem. Is this thing on? It is? Well …

Ahem. Is this thing on? It is? Well …

Happy … New Year.

Here’s the thing: Screaming “Happy New Year” has felt so strange over the last few years because of everything going on. And I’ll be honest with you all: This year, my New Year’s Eve was spent lying on a beanbag in my house alone, binging a Netflix show. It came and went and there was a part of me that felt so exhausted by the last year — the last two years — that I didn’t even have the energy to welcome 2022 with cheer. Well, that’s not the only reason. I think I also have become a bit nervous about being joyous about the new year just because life still seems to be in a strange knot, one that seems to be tightening due to what seems to be an immortal virus. Oof. But on New Year’s Day, I woke up and realized … I woke up. Again. And even though it’s been a complicated time, joy is still not only possible, but … inevitable. It’s coming. Because it has to. And guess why it has to? Guess?

Because I say so.

That’s how it works. We choose it. We go searching for it. We reach for it and hold onto it as tightly as possible. But we have to decide that it’s so.

Know what it reminds me of? Trying to hold water. I know, strange transition, but go with me.

If you’ve ever tried to hold water, you know that it’s such a strange experience because it never actually feels like you’re holding anything. And then when you open your hands, the water drips out and now you’re holding nothing. So the question is, how do we keep water in our hands? Well, we keep it there by trusting it’s actually there. And if we believe it’s there, we just hold it tighter. There’s no need to check and see. There’s no need to doubt it because doubt will leave us empty-handed. That’s what we have to do with joy this year.

It’s there for us. It’s in us and around us and we just have to trust that. Which means as we enter into this new year, and we wish people a Happy New Year, we have to mean it despite our circumstances. We have to trust that the newness of the year guarantees happiness, and that our belief that it belongs to us will make it so that Happy Old Year will be an accurate statement.

So buck up, Buttercup. We’re still here. Laughter still lives in us. Beauty still blossoms around us. Love has never lost and is even more infectious than you-know-what.

I love you, and Happy Happy Happy New Year.

Jason

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

January 6, 2022

Building the Library’s Collections: From (and for) The People

Image from “Visions of the Daughters of Albion,” by William Blake, 1793. Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

Over the past two centuries, the unparalleled collections of the Library of Congress have, in no small part, been built by America’s citizens themselves — truly collections for and by the people.

Generations of civic-minded folks have donated important collections to the Library, allowing them to remain accessible to the public for posterity.

In this way, the Library has acquired an amazing array of material that collectively chronicles centuries of human achievement, history and culture.

Lincoln’s original drafts of the Gettysburg Address, the diaries of Theodore Roosevelt, Walt Whitman’s notes for “Leaves of Grass,” the journals of Alexander Graham Bell documenting his invention of the telephone, Irving Berlin’s handwritten score for “God Bless America,” the papers of Rosa Parks, the diaries of Orville Wright chronicling the first powered flight — all were obtained by the Library via donation, gifts from citizens to the American public.

The list of donated treasures stretches on and on: first folios of Shakespeare’s plays, the original Disney storyboards for Mickey Mouse, the first photographic “selfie,” Sigmund Freud’s home movies, Steinbeck’s typescript for “The Grapes of Wrath,” 3D models of Normandy beaches used to train troops for D-Day landings, and thousands of rare baseball cards collected by businessman Benjamin K. Edwards and donated to the Library in 1954 by poet Carl Sandburg.

The Library is the oldest federal cultural institution in the nation and, with over 171 million collection items, the largest library in the world.

From the start, 221 years ago, it has been funded through the generosity of Congress and the U.S. taxpayer.

In 1800, President John Adams approved legislation that appropriated $5,000 to purchase “such books as may be necessary for the use of Congress.” After the British burned the U.S. Capitol in 1814, Congress spent $23,940 to buy Thomas Jefferson’s personal library — 6,487 volumes that formed the foundation of the modern Library’s collections.

Congressional funding built the Library’s magnificent facilities on Capitol Hill and, today, pays for operations and acquisitions with money that ultimately comes from taxpayers.

But the collections likewise have been directly built by America’s citizens, by folks who follow their passions and invest their time, money and energy into researching and acquiring material, then hand over this life’s work to the Library for safekeeping in the public trust.

Collectors are the ultimate crowdsource, gathering material on whatever subjects strike their particular fancy, adding to our knowledge of our world and our past.

Early in his career, Jay I. Kislak moved to Florida and began to study the history of his new home. Over five decades, he amassed a comprehensive collection on the early history of Florida, the Caribbean and Mesoamerica and, in 2004, donated it to the Library.

Hollow sculpture of a kneeling man from western Mexico. Made between 200 B.C.-A.D. 300. Jay I. Kislak Collection. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

The collection is among the finest of its kind — rare masterpieces of indigenous art, original manuscripts written by historic figures such as King Philip II of Spain, conquistador Hernán Cortés, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, great maps such as the Martin Waldseemüller’s 1516 Carta Marina.

An unidentified Black Union soldier, posing with his wife and daughters. The picture was found in Cecil County, Maryland. Liljenquist Family Collection, Prints and Photographs Division.

Inspired by a chance encounter with a Civil War photograph in a shop in Ellicott City, Maryland, Tom Liljenquist and his three sons spent some 15 years building a major collection of rare photographic portraits of Union and Confederate soldiers and their families. The family gave the collection to the Library in 2010 and continue to add to it — its value has surpassed $4.5 million.

Gertrude Clarke Whittall grew up hearing musicians perform live in her Massachusetts home, fostering a lifelong love of classical music. Later, as she traveled the world, Whittall saw great examples of musical instruments on exhibit, sitting behind glass, and had an idea: Wouldn’t it be nice to build a collection of instruments by the supreme makers and make them accessible to the public back home in America, to not just be seen but also heard in concert?

The incredible collection she built and donated to the Library in the 1930s — five stringed instruments by Stradivari and five others by Amati, Vuillaume and Guarneri — is available to researchers and, today, the instruments still are regularly played for public audiences, just as she’d intended.

Not all collections are so grand in ambition; they often reflect the extremely specific interests of the folks who build them.

Charles B. Sonneborn, a music-loving ophthalmologist, collected nearly 800 examples of sheet music that feature the word “eyes” in the title, putting classics (“Smoke Gets in Your Eyes”) alongside long-forgotten efforts that, nevertheless, instantly evoke the sensibilities of eras gone by (“Never Make Eyes at the Gals with the Guys Who Are Bigger Than You”).

During the mid-20th-century golden age of travel, railway engineer György Rázsó so enjoyed the colorful, arty luggage labels produced by hotels that he planned vacations around collecting them — and, naturally, declined to actually stick them on his luggage so that they would remain pristine.

Noemi Razso donated her father’s collection of luggage labels from hotels across the United States in the mid-20th century. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Rázsó gathered 1,882 such labels over 30 years and eventually donated them to the Library — a collection of perhaps trivial-seeming things that nonetheless presents a visual record of American hotel advertising.

Collections of such things, of so-called “ephemera,” help bring history to life.

Travelers today, accustomed to the cattle-car quality of modern travel, can look at a luggage label for the Clover Inn, tucked cozily away among the giant redwoods, and just feel the difference in the eras. A music lover could leaf through Sonneborn’s collection and appreciate the seismic shifts in artistic sensibilities across the generations.

The Library and, ultimately, the public get the benefits of not just the collectors’ time, energy and resources, but also their expertise.

Collectors spend years searching and researching, finding important and unique items and learning about them. In the course of doing so, they often develop specialized knowledge that is an invaluable resource in itself.

The world is big, the material that might be collected from it is endless, and the Library’s time and resources are finite. Billions of photos are taken in a year; the Library can’t assess, gather or accept them all.

Collectors, using their knowledge and experience, select out the best. As a result, they build remarkable, important compilations that chronicle countless aspects of our history.

Lessing J. Rosenwald, heir to the Sears, Roebuck and Co. fortune, built a collection of thousands of exceptionally rare illustrated books and prints that bring the most pivotal eras of Western history to life — great works such as “Epistolae et Evangelia,” the finest illustrated book of the 15th century; a supreme gathering of books, drawings and engravings by poet and artist William Blake; or the Giant Bible of Mainz, the last large handwritten Bible produced before the advent of the printing press.

Katherine Golden Bitting, a food chemist for the Department of Agriculture, amassed a personal collection of materials about growing, preparing, cooking, preserving and eating food — including a 15th-century Italian manuscript that served as the basis of history’s first printed cookbook. After Bitting died, her husband presented the 4,346-volume collection to the Library.

Dayton C. Miller grew up in Ohio obsessed with science and music — at his high school graduation, he delivered a lecture about the sun and, as part of the ceremony, played the flute.

Miller studied astronomy, became an expert on acoustics, helped design sonically perfect music venues, debated Einstein on relativity and pioneered the use of X-rays in medicine — he toured the country promoting them and once underwent a full-body X-ray to demonstrate the procedure’s value.

He also became one of the world’s foremost experts on the flute. Miller collected enormous numbers of music scores, reference books and related material and thousands of flutes, creating the definitive collection on the instrument.

He also wrote music for the flute and built his own — including one of 22-karat gold that, he calculated, took 2,250 hours to make. He was such an expert that makers from around the globe traveled to him to consult on manufacturing their instruments.

That continues today, in a way. Miller donated his collection to the Library and, 80 years after his death, researchers and musicians from around the world still come here to study it and play the instruments.

Likewise, shelves are lined with Civil War books whose pages feature portraits from the Liljenquist collection, staring back at you across the generations. Researchers from across the globe have applied modern technology to their studies of the Whittall Strads to learn how a maker from a small town in 17th-century Italy could make a violin that still sounds so good 300 years later.

Those things wouldn’t happen without the civic-minded citizens who play their own role in the preservation of our cultural heritage, building collections and sharing them with the rest of the world — gifts that keep on giving.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

January 4, 2022

The Rolling Stones, Hell’s Angels and Altamont: A New View

Mick Jagger (in red) and Keith Richards (in shades, natch), just off stage at the Altamont concert, hours before their segment turned deadly. Dec. 6, 1969. Home video footage. National Audio-Visual Conservation Center.

This is a guest post by Mike Mashon, head of the Moving Image Section.

Here at the Library, we’re dedicated to the acquisition, description, preservation and accessibility of our film, video, and sound recording collections regardless of perceived “worth.” We really do want to make it all available for future generations ̶ so we don’t necessarily prioritize beloved classics over a refrigerator ad or the song “Fido is a Hot Dog Now.”

But every so often something comes along that attracts a lot of attention – such as a never-before-seen home movie from the notorious Altamont Free Concert in 1969, in which the Hell’s Angels, who had been hired to provide security, stabbed a fan to death during a confrontation over a gun. It was a major cultural turning point of the era, and the heart of the Maysles Brothers 1970 documentary “Gimme Shelter.”

But this new find was home footage from the event that had never seen the light of day and it’s now available for viewing on the National Screening Room. (There is no audio, so don’t try to fix your sound.)

And as is so often the case, the tale of how this remarkable video emerged from a mass of unprocessed films is a pretty good story on its own.

It starts in 1996 when archivist/historian/collector/polymath Rick Prelinger — one of the most influential thinkers in our field—acquired a cache of reels from Palmer Labs, a San Francisco company that was going out of business. He added them to his burgeoning collection of ephemeral films.

In 2002, the Library acquired the roughly 140,000 reels in the Prelinger Collection. A press release predicted it would “take several years before the Library will be in a position to provide access to these films.” As it turns out, that was optimistic — we are still making steady progress on the collection 19 years later.

Then, not long ago, a technician working on the Prelinger Collection came across two reels of silent 8mm reversal positive—a common home movie format. The handwritten note on the film leader read “Stones in the Park,” so that was the title he gave it for our inventory.

When I saw that, I immediately thought that it could be a home movie of the July 5, 1969, Rolling Stones Hyde Park concert held in London a couple of days after the death of guitarist Brian Jones. But it could also be a copy of a documentary of the same name, which would make the discovery considerably less interesting.

Regardless, I sent the reels up for 2K digitization by our film preservation laboratory. A couple of days later, I heard from some very excited colleagues that the scan wasn’t the Hyde Park show. It was from the Altamont Speedway concert in California and it definitely wasn’t footage from the 1970 documentary.

Many people know the “Gimme Shelter” documentary pretty well, but there’s a lot more in this home movie.

Carlos Santana performs at Altamont, Dec. 6, 1969. Home video footage. National Audio-Visual Conservation Center.

Although the footage is silent, we were all thrilled to see close-up footage of concert performers who were cut from the film, such as Carlos Santana and Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young. (CNSY wasn’t pleased with their performance and refused to let the Maysles include them.) It was especially great to see Gram Parsons fronting the Flying Burrito Brothers, since you only see the back of his head in “Gimme Shelter.” Even better, there are good shots of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards off-stage watching him perform!

The second reel is from the Stones’ evening performance, which, while it captures some of chaos so memorably seen in “Gimme Shelter,” doesn’t add anything to our understanding of the death of Meredith Hunter at the hands of a member of the Hell’s Angels.

So what’s the legal status of this home movie? After checking in with Rick to see if he had any inkling of the film’s existence—he didn’t—and not discovering any pertinent documentation, we believe that it is an orphan work, in this case abandoned at Palmer Labs by whoever shot it. They just never picked it up.

We have a particular fondness for home movies here at the Library. Several are on the National Film Registry and of course the Prelinger Collection is full of them, so who knows what further treasures will emerge?

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox

December 30, 2021

World War II: The Debut of G.I. Joe

David Breger with his alter-ego, G.I. Joe. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by Meg McAleer, a historian in the Manuscript Division. It ran in the Nov.-Dec. issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

The “Private Breger” cartoon was born under mosquito netting in densely humid Louisiana. David Breger, a successful freelance cartoonist, drafted into the Army in 1941, created the cartoon during his off-duty hours at Camp Livingston. It quickly caught on, and “Private Breger” became a popular feature in the Saturday Evening Post, one of the most popular magazines of the day. That’s where the Army discovered it and wanted it for its own — just under a different name.

That was how “Private Breger” acquired an identical twin, “G.I. Joe,” Breger’s name for his new cartoon character. It appeared in Yank, the Army Weekly, and then Stars and Stripes, while “Private Breger” remained stateside. As David Breger had to explain repeatedly, the “G.I.” in G.I. Joe stood for “government issue.”

American soldiers quickly adopted the G.I. Joe moniker as their own, but not because the cartoon portrayed an ideal warrior. The Private Breger and G.I. Joe characters bore a striking resemblance to Breger himself with comic embellishments — freckles, soft bodies of short stature, wide eyes encased in round glasses, upturned faces, forward-leaning postures and innocent expressions that occasionally betrayed mischievousness, but never cynicism.

G. I. Joe, as drawn by Breger. Prints and Photographs Division.

Breger’s G.I. Joe was the antithesis of the muscled Hasbro action doll of the same name in the 1960s, yet he was somehow more. He represented a generation that found itself in unimaginable situations and yet went all in, summoning all that it had, not always performing to perfection, yet giving its best.

Breger’s children recently donated their father’s collection to the Library, where it is housed in the Manuscript Division and Prints and Photographs Division. The gift was one of many donated during the pandemic, the result of people having more free time to sort through attics, but also from a desire to give generously during a world crisis. This particular gift has renewed American memories of an old hero who bore tough times with resilience, humor and imperfect humanness just as we grapple with our own challenging times.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

December 27, 2021

My Job: Michele Glymph

Michele Glymph.

Concert producer Michele Glymph helps bring music to the masses.

Describe your work at the Library.

As a senior music specialist/concert producer, my responsibilities include producing the Concerts from the Library of Congress series and working closely with the Library’s Events Office to present high-profile events. The events include the Gershwin Prize for Popular Song, special exhibitions, lectures and book signings.

Additionally, I serve as the Music Division’s fund manager, with responsibilities for monitoring the operations of 43 gift and trust funds while working closely with the Financial Service Directorate and the chief and assistant chief of the Music Division. I also serve as facility manager of the Coolidge Auditorium and Whittall Pavilion, which houses the Library’s renowned Stradivarius instruments.

How did you prepare for your position?

Growing up, I listened to all types of music, never realizing that music would become my career. I came to the Library as a 16-year-old work-study student on a referral from a U.S. senator.

I planned to spend only a summer at the Library but fell in love with the music collections and live performances. One summer turned into a 44-year love affair, and I am still here and still in love with my work. I have been fortunate to have great mentors who observed my talents early in my career and trusted me to get the job done.

What have been your most memorable experiences at the Library?

In my position, I have met and worked with many luminaries, including three U.S. presidents: William J. Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama. I interviewed Gershwin Prize for Popular Song honoree Smokey Robinson and produced memorable concerts that featured Stevie Wonder, Dolly Parton, Paul McCartney, Garth Brooks, Willie Nelson, Shirley Caesar, Billy Joel and Gloria and Emilio Estefan.

Another treasured memory was going to Thailand for the retrieval of traditional Thai instruments, on exhibit from the Library at the King’s Palace (the instruments were given to the Library in 1960 as a gift from King Bhumibol Adulyadej). I also traveled to St. Louis to pack and ship the Katherine Dunham Dance Collection, working from her home surrounded by items she collected during her travels.

While all these memories are important to me, the most significant event that I will most cherish was witnessing the first African American woman become the Librarian of Congress. This really stands apart from everything else!

What are your favorite collections items?

I really do not have a favorite item. There are so many amazing items in our collections, however, if I had to name a few they would be the Louis Armstrong collection of letters; “The Wiz” production materials; Gershwin self-portraits; the Federal Theatre Project, which includes the first all-black “Macbeth” cast; the Alvin Ailey Dance Collection; and Beethoven’s hair.

I’ve really enjoyed being able to work with the Stradivarius instrument collection and to hear them played by some of the most famous artists in the world on the Coolidge Auditorium stage. There is so much history throughout the Library, and I am grateful to continue to be a part of making history that will be stored within our collections.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

December 22, 2021

Poinsettia: How a U.S. Diplomat Made a Mexican Flower an International Favorite

Woman with a poinsettia, 1910. Publisher unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by Maria Peña, a public relations strategist in the Library’s Office of Communications.

No Christmas holiday scene in the U.S. would be complete without the poinsettia, available in more than one hundred varieties but mostly sold in vibrant red, pink, white and marbled colors. With more than 35 million sold annually, the pre-Columbian plant is the best-selling potted bloom in the United States, contributing roughly $250 million to the economy. Most are sold in a six-week stretch leading up to the Christmas holiday.

But did you know that those red poinsettias sitting on your mantle, in your dining room or under your tree are indigenous to Mexico and parts of Central America?

The plant’s name in English name stems from Joel Roberts Poinsett, an American botany enthusiast and the first U.S. Minister (ambassador) to Mexico in the early 19th century, whose papers are kept in the Manuscript Division. He came across it in Taxco, in the state of Guerrero, in 1828, brought it back to his South Carolina home and began its worldwide popularization.

But long before that, the plant had been blooming in Mexico and Central America for centuries, called by a variety of names. In Nahuatl, both the name of the peoples and the language in Central Mexico, the name for the plant was “Cuetlaxóchitl,” meaning “a flower that withers.” According to some legends, the Aztecs in pre-Columbian Mexico harvested them and used them in different war rituals, to produce dye for textiles and cosmetics, or for medicinal purposes (the milky white sap was used to reduce fevers).

In the “General History of the Things of New Spain,” published in1577, Fray Bernardino de Sahagún describes the shrubs as having leaves that resemble those of the cherry tree but are “very red and pliable,” according to a liberal translation of the old text. They are not fragrant, he continues, yet “they’re indeed beautiful and that’s why they’re prized.”

After the Spanish conquest, during the 17th century, Franciscan friars used the colorful, showy plant not only to decorate altars and nativity scenes but also to evangelize indigenous populations. The friars renamed it “flor de Nochebuena” (“Holy Night flower”) because it blooms around Christmas. In other parts of Latin America, the flower goes by other names, including “pastora” and “flor de Pascuas.”

Joel Poinsett, diplomat, statesman and amateur botanist. Portrait: Chas. Fenderich, 1838. Prints and Photographs Division.

But when Poinsett brought it back to his greenhouses, his success with the star-shaped blooms quickly earned him international recognition far beyond his political accomplishments. Poinsett sent one of his specimens to Robert Buist, a famous Philadelphia botanist with the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, who exhibited the plant for the first time at a flower show in 1829.

A successful floral import-export executive, Buist introduced the plant in Europe in the1830s and christened it “Euphorbia Poinsettia” in honor of his friend. Apparently, people soon forgot the difficult Latin name, but “poinsettia” stuck with American and European consumers. After the Vatican began using this most universal of all Mexican flowers for Christmas decoration in the 19th century, all Catholic churches soon followed suit.

The mass cultivation of poinsettias reached an industrial scale in the U.S. early in the 20th century when Albert Ecke, a German immigrant, settled in Encinitas, California, and began growing them in earnest. His son, Paul, inherited the thriving business in 1919. The Ecke family soon held about 500 plant patents in the U.S., nearly a fifth of them for the poinsettia modifications the family patriarch crafted.

By 2002, the plant’s success was enshrined, with Congress formally recognizing Dec. 12 as National Poinsettia Day to honor Poinsett and mark his death on that day in 1851.

Today, the plant is an important source of revenue for Mexican farmers, who export cuttings to American growers. Poinsettias account for 60 percent of cuttings exported to global markets, although the COVID-19 pandemic caused a drop in 2020, according to the Mexican Flower Council.

According to Mexican popular culture, if you receive a poinsettia plant as a gift it will bring you good luck and prosperity. Call it poinsettia, “Cuetlaxóchit,” “pastora” or “Nochebuena,” it’s a great gift to brighten your hearth this season.

A poinsettia, now popular worldwide, grows in Lachung, an Indian village close to the border of Tibet. Photo: Alice Kandell. Prints and Photographs Division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox

December 21, 2021

The (St. Louis) Story Behind “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas”

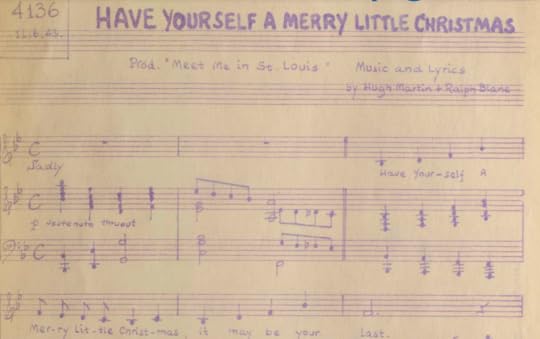

The copyright submission for “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas.”

Few holiday songs strike a melancholy note quite like “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas,” the poignant Hugh Martin and Ralph Blane tune that summons hope in troubled times and the comfort of friends and family close by.

It wasn’t always so.

The original, unpublished version of the song (above), submitted to the Copyright Office at the Library in November 1943, made for a most bleak holiday:

Have yourself a merry little Christmas

It may be your last

Next year we may all be living in the past. …

Faithful friends who were dear to us

Will be near to us no more.

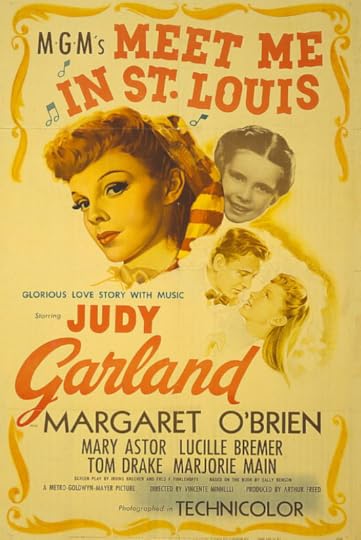

The song debuted in the the 1944 hit musical “Meet Me in St. Louis,” starring Judy Garland. In the film, Garland and her siblings learn the family soon will move across the country to New York — devastating news that would upend romances and friendships. The script called for Garland to soothe her youngest sister on Christmas Even by singing “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas.”

She balked: Those lines would be more cruel than comforting to a kid afraid she’d never see her friends again.

Martin resisted a rewrite but eventually altered the lyrics to those Garland sang in the film, a version submitted for copyright 11 months after the original.

The new lines, wistful but warm, offered hope — to Garland’s on-screen sister, to an audience separated from loved ones by World War II. Seven decades later, they still do:

Have yourself a merry little Christmas

Let your heart be light

From now on your troubles will be out of sight.

The 1944 movie poster for “Meet Me in St. Louis.” Prints and Photographs Division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox

December 20, 2021

“A Christmas Memory,” Truman Capote’s Classic, Handwritten at the Library

The cover of “A Christmas Memory,” with young Truman Capote standing next to his beloved cousin “Sook,” Nanny Rumbley Faulk.

“A Christmas Memory,” Truman Capote’s story about his Alabama childhood with an eccentric elderly cousin, has been one of the nation’s most beloved tales in the holiday canon for more than half a century.

First published in Mademoiselle magazine in the winter of 1956, it starts this way:

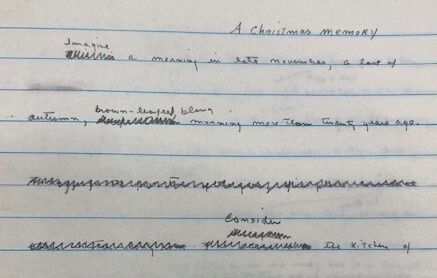

“Imagine a morning in late November. A coming of winter morning more than twenty years ago. Consider the kitchen of a spreading old house in a country town.”

His cousin, Nanny Rumbley Faulk, soon arises to exclaim, with her sherry-colored eyes, her breath smoking the windowpane, “Oh my! It’s fruitcake weather!” They were two misfits in a no-nonsense Southern household in the 1920s and ’30s. He called her “Sook.” She called him “Buddy.” They were cheerful co-conspirators at the opposite end of their lives; each delicate, sensitive and adoring of one other.

Since then, the story has been issued and reissued in books and anthologies, over and over again, adapted to television at least twice, staged as an off-Broadway musical and even as an opera. Sook has been portrayed on camera by legendary actresses Geraldine Page and Patty Duke; the musical featured Tony Award-winner Alice Ripley. It’s around every Christmas, as dependable as holly and mistletoe.

Capote was an icon to me as a young writer, also growing up in a tiny Southern town lost among the pines, so you can imagine my delight when I discovered that the Library has Capote’s original, handwritten copy of the tale as part of his early papers. It is penciled into two thin brown notebooks marked with his neat, tiny script. “A Christmas Memory 1” he wrote on the cover of one, and “A Christmas Memory 2” on the other.

The story fills just a few lines on each page. There are several word edits, but only a couple of crossed out passages. The image that features in the story’s famous ending popped into his mind midway through the second notebook. He wrote it at the very top of the page: “kites like a pair of mingled hearts hurrying toward heaven.” A few pages later, he dropped it in for the story’s heartbreaking conclusion, exactly as it appears in the published version: “As if I expected to see, rather like hearts, a lost pair of kites hurrying toward heaven.”

Just like that, the entire piece seems to have emerged from his hand in a single sitting.

Brick ruins show the outlines of the “spreading old house” in Monroeville, Alabama, where Capote lived with his extended family, the setting for “A Christmas Memory.” Photo: Carol M. Highsmith

Today, the notebooks rest inside in a green folder tucked into a beige box, part of his collection in the Manuscript Division. Taken together, these early stories are a marvelous insight into his working technique and personal style.

He bought the occasional leather-bound journal for note-taking. He used a black one for his interviews with Marlon Brando on a movie location in Japan, which would become the classic 1957 New Yorker piece “The Duke in His Domain.” (More than two decades later, when I was a college journalism student, the professor taught that article as “how the masters wrote a profile” lesson. And here, lo and behold, was the actual notebook from the interview.)

His papers show he bought other fancy, hard-bound ledgers every now and again, say, from Italian bookshops during his vacations there. The first notebook he took with him to Kansas for reporting what would become “In Cold Blood” is one of these. Given his high-flying style, it’s about what one would expect.

But mostly, he worked with flimsy grade-school notebooks that cost a nickel or 10 cents. One is actually “Schooltime Compositions,” with a blank spot on the cover for one’s name, school and grade. He rarely filled out complete pages, but usually just a few paragraphs. His handwriting was precise and almost indecipherably miniscule.

And so it was with “Christmas.”

It’s written in two small “Double Q” notebooks “(Quality! Quantity),” which cost 10 cents each.

On top of the first line of the first page, he wrote his title, like a kid composing a high-school essay. Then, on the next line, he took a swing at the opener. The finished version is quoted above. Here was his first take: “Imagine a morning in late November, a last day of autumn, brown-leafed blowing morning more than twenty years ago.” The next line is crossed out, before picking up with “Consider the kitchen of a rambling old house in a country town.”

The opening page of “A Christmas Memory.” Manuscript Division

He crossed out his very first word, replacing it with “Imagine.” It appears, under the scratching, to be “This is,” as if he was starting the story in the present tense.

That’s about as much editing as you’ll see on any page. The story as it is written here is very close to the finished text. It’s tempting to think that the story came to him this cleanly, this clearly, and that we are looking at his first draft. Certainly he went through it again for a typewritten manuscript to send off for publication.

But I doubt there were many drafts. This was a deeply felt story for Capote. He was 32 when it was published — almost certainly a year younger when he wrote it — and was known only as the author of a daring debut novel, “Other Voices, Other Rooms.” He had yet to publish “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” the novella that would make him a star. (“Christmas” would first be published in book form as collection of stories with “Breakfast” two years later.)

Reading these pages, looking at his pencil moving carefully across the page, you don’t get the idea he’s copying earlier notes. You get the idea that the story is flowing, his mind is focused and that a moment of youthful innocence, a long-lost period when he felt safe and happy and loved, was upon him once more.

It was so short, so sincere and so touching that audiences called upon him to give readings from it for the rest of his life. In the wake of “In Cold Blood,” his mammoth success, crowds still wanted “Christmas.” After one such posh Manhattan gathering in the winter of 1966, audience members had tears in their eyes when he finished, writes Gerald Clarke in his biography, “Capote.” “It was a very moving moment for me,” Barbara Paley, the socially powerful wife of CBS founder William S. Paley, is quoted as saying.

Later that year, when publishers announced “Christmas” was going to be reissued as a special boxed set, Capote was ecstatic about the cash flow. “It’s forty-five pages long, and it’s going to cost five dollars and be worth every cent,” he chortled. That’s about $43 in 2021 dollars for a book the width of your little finger. It sold phenomenally well.

Capote died in 1984 after long years of drug and alcohol abuse, often in the public eye. He had become a caricature of himself, his talent and drive long since dissipated. He was only 59.

But here, on these youthful pages, there is not a teaspoonful of anything artificial and there’s nothing diluted, either. The sincerity of his emotion and the surety of his vision is in every line. On his deathbed, his mind wandering, his final words? “It’s me, it’s Buddy.” As if he was reunited with Sook at last.

It was, at the end, where he always wanted to be.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

December 16, 2021

The “tick, tick … BOOM!” Research at the Library

Lin-Manuel Miranda (from left), Steven Levenson and Jennifer Tepper view musical theater holdings in the Performing Arts Reading Room in October 2017. Photo: Roswell Encina.

When Lin-Manuel Miranda visited the Library on Oct. 10, 2017, not many people knew about it. Clad in jeans and sweatshirt, the celebrated “Hamilton” creator quietly made his way to the Performing Arts Reading Room.

There, with two companions, he began sifting through the papers of theater composer Jonathan Larson. The trio was on a mission to bring one of Larson’s works to cinematic life.

The result became public in November, when Netflix released Miranda’s directorial debut, “tick, tick … BOOM!” The film expands on a semiautobiographical one-man show Larson wrote before his breakthrough musical, “Rent,” took Broadway by storm.

Larson conceived “tick, tick” (with a different title) in 1990 when he was about to turn 30, anxious his career was going nowhere after a decade of devotion. The film tells a similar story about a theater composer, Jonathan, wondering if he should give up his Broadway dream for a different life.

Tragically, Larson died suddenly in 1996 just before the first scheduled performance of “Rent.” Several years later, his family donated his papers to the Library.

When Miranda came to the Library in 2017, his companions were “tick, tick” scriptwriter Steven Levenson of “Dear Evan Hansen” fame and theater historian Jennifer Tepper. She had used Larson’s papers extensively and guided Miranda and Levenson to gems within them. [https://go.usa.gov/xeVAZ]

“What’s particularly exciting to us … is how much of what they discovered in the Larson collection ended up being added to the film,” Mark Horowitz, senior music specialist, said. “This is the fantasy for us archivists — that because we acquired … a collection, previously unknown, lost or forgotten work has had life breathed into it.”

There really is no definitive “tick, tick” script, Horowitz said. Larson’s papers contain various iterations and drafts. After he died, playwright David Auburn adapted “tick, tick” into a three-person off-Broadway musical. That’s when Miranda first encountered it.

Already an aspiring composer, he saw the musical in a small New York theater in 2001 when he was a college senior, he’s said. Then, in 2014, before “Hamilton” made him a household name, Miranda played Jonathan in a “tick, tick” revival. His performance, wrote the New York Times, “throbs with a sense of bone-deep identification.”

The movie version of “tick, tick” adds details about Larson that aren’t in his script and draws on his collection at the Library, including original songs that haven’t previously had a public audience.

A song from the collection, “Swimming,” became a major number in the film, Horowitz said, and a dance scene unfolds to a piece of original music by Larson. In a car scene, Larson’s music plays on the radio.

“It’s thrilling to us,” Horowitz said of the movie’s interpolation of Larson’s music. “You get collections because you hope they’ll be used and appreciated, but there are no guarantees.”

Larson’s collection is among Horowitz’s favorites. “I’ve actually never seen a collection quite like it,” he said.

Larson wrote notes and questions to himself that he would try to answer, Horowitz said. And for “Rent,” he wrote biographies of major characters more than once as the show changed.

“It’s just really rich, incredible stuff,” Horowitz said.

He acquired the collection for the Library and processed it, an experience he described as approaching otherworldly.

“It’s happened to me on a handful of collections,” he said. “You begin to feel the ghost of the creator standing over your shoulder. They become a presence … and you want to honor them.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers