Jack Ross's Blog, page 10

May 13, 2022

Fen Country: Edmund Crispin

Edmund Crispin: The Glimpses of the Moon (1977)

Edmund Crispin: The Glimpses of the Moon (1977)"Under another name, he's a sort of male C. V. Wedgwood"

- The Glimpses of the Moon, pp. 74-75.

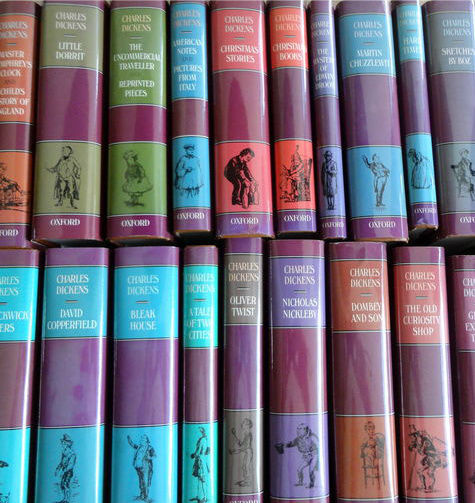

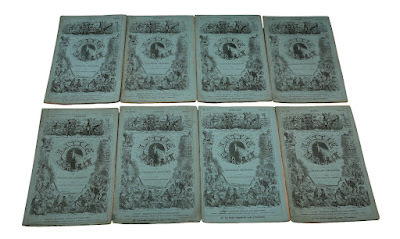

Between 1944 and 1955, promising young British composer Bruce Montgomery published eight detective novels and one collection of short stories under the pseudonym 'Edmund Crispin'. He also sold 38 stories to a variety of periodicals in Britain and the USA.

Most of these narratives featured the eccentric Academic Gervase Fen, Professor of English Language and Literature at the University of Oxford, as their presiding sleuth.

Edmund Crispin: Fen Country (1979)

Edmund Crispin: Fen Country (1979)After that there was a long silence until his final novel, The Glimpses of the Moon, appeared in 1977, the year before his death. It was followed by a further collection of short stories, Fen Country, which completed the canon.

Edmund Crispin: Swan Song (1947)

Edmund Crispin: Swan Song (1947)'There goes C. S. Lewis,' said Fen suddenly. 'It must be Tuesday.'

'It is Tuesday.' Sir Richard struck a match and puffed doggedly at his pipe.

- Swan Song, p.60.

Why does he interest me so? Is it the minute portrait his books convey of an austerity Britain, first in the grip of wartime rationing, then of post-war shortages? Is it the constant barrage of in-jokes, comprehensible only to those familiar with such contemporary cultural icons as C. S. Lewis and C. V. Wedgwood? Or his ornate, orotund style of writing?

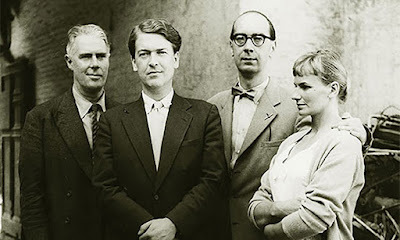

Anthony Powell, Kingsley Amis, Philip Larkin, Hilary Amis

Anthony Powell, Kingsley Amis, Philip Larkin, Hilary Amis"An undergrad left an essay for you. I've been reading it. It's called - Sally puckered up her attractive forehead - 'The influence of Sir Gawain on Arnold's Empedocles on Etna'."

"Good heavens," Fen groaned. "That must be Larkin: the most indefatigable searcher-out of pointless correspondences the world has ever known."

- The Moving Toyshop, pp.110-11.

As well as all that, there's the 'Movement' connection. He was up at Oxford at the same time as Kingsley Amis and Philip Larkin, and the pair were initially hugely impressed by his effortless cosmopolitan airs and (initial) success with publishers, only to become increasingly carping and bitchy about him and his work as their own social and literary prestige mounted into the stratosphere.

So, yes, there's a good deal of gossip about him and his ways to be gleaned from their respective memoirs and biographies and collections of letters. If you read that kind of thing, that is. Which I do (obviously).

Edmund Crispin: The Moving Toyshop (1946)

Edmund Crispin: The Moving Toyshop (1946)She talked about murder as she might have talked about the weather - being far too selfish, thick-skinned and unimaginative to see the implications either of that final, irrevocable act or of her own position. - The Moving Toyshop, p.105.

One of things that interests me most about the Montgomery / Crispin books is Gervase Fen himself. Not that Fen is a well-developed character. On the contrary, as I read my way through the books as a teenager, I was struck by how well portrayed and accurately placed most of the other people are, and how bizarrely unfocussed is Fen. It's almost as if the more we hear about him, the less there he is. His age seems fixed around 40, regardless of what year it is, and his Academic position at Oxford remains essentially unchanged throughout.

I don't know if this was intentional or not. I've sometimes wondered if it's connected to Crispin's unusual focus on the consequences of crime. His victims are not the cardboard cut-outs of an Agatha Christie or even a Dorothy Sayers, but living, breathing people, whose brutal deaths leave a gap in the world. It's as if he can't quite bring himself ever to forget the morality of the spectacle he's creating, however frivolously it may be framed.

Edmund Crispin: Frequent Hearses (1950)

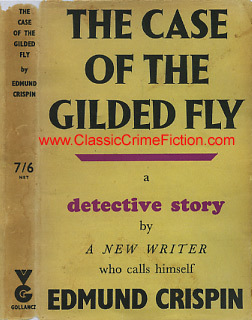

Edmund Crispin: Frequent Hearses (1950)Some of my taste for his work undoubtedly comes down to a similar taste in books. M. R. James is a persistent influence on Crispin throughout: most notably in the long description of the maze in Frequent Hearses, but also in the inset ghost story in his very first novel, The Case of the Gilded Fly, and the macabre goings-on in the cathedral in Holy Disorders.

Edmund Crispin: Holy Disorders (1945)

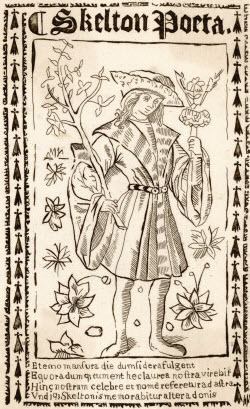

Edmund Crispin: Holy Disorders (1945)He's also very well acquainted with the highway and byways of 17th and 18th century English poetry, which provide a good many of his titles - as well as most of the numerous epigraphs scattered through his pages.

Edmund Crispin: Love Lies Bleeding (1948)

Edmund Crispin: Love Lies Bleeding (1948)In the last, longest and probably least focussed of his books, The Glimpses of the Moon, there's an illuminating aside by Fen, who's been forced by the insolvency of his publisher to abandon the book on modern British novelists he's been working on in a desultory manner throughout the whole narrative:

Fen pondered this; and the more he pondered it, the more he liked it. Some of the reading had been enjoyable, of course - The Doctor is Sick, I Want It Now, 'the Balkan trilogy', Elizabeth Bowen, The Ballad and the Source. But much more had not - and a great deal that was pending wasn't going to be either. [p.270]It's typical of Crispin that this passage will mean very little to anyone unfamiliar with the fiction of this period. I can't claim to have read all of the books on his list, but I have to say that this small selection seems to me very much on the money.

Edmund Crispin: The Long Divorce (1951)

Edmund Crispin: The Long Divorce (1951)Let's see then. In strictly alphabetical order, reference is being made to:

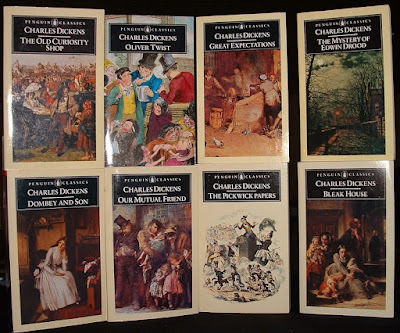

Amis, Kingsley. I Want It Now. 1968. London: Panther Books, 1969.Bowen, Elizabeth. The Collected Stories of Elizabeth Bowen. 1980. Introduction by Angus Wilson. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983.Burgess, Anthony. The Doctor is Sick. 1960. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1979.Lehmann, Rosamond. The Ballad and the Source. London: Collins, 1944.Manning, Olivia. The Balkan Trilogy. Volume One: The Great Fortune / Volume Two: The Spoilt City / Volume Three: Friends and Heroes. 1960, 1962 & 1965. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1982.They're not all obvious choices by any means. I haven't read the Lehmann book or much of Elizabeth Bowen beyond her short stories, but the others seem quite inspired to me.

The Doctor is Sick is one of four novels written by Anthony Burgess during his 1960 annus mirabilis, shortly after receiving a (later rescinded) sentence of death from his doctors. By far the most famous of these is A Clockwork Orange, but I'd already clocked The Doctor as by far the most entertaining of the bunch even before reading Crispin.

Kingsley Amis, too, is an author whom I've read both in bulk and in depth. I Want It Now is certainly not one of his most celebrated novels - no Lucky Jim or One Fat Englishman - but it is, again, quite exceptionally fun to read even in so impressive a line-up of hits.

As for The Balkan Trilogy, I've always been glad that this casual reference by Crispin inspired me to track it down and read it a number of times before it achieved temporary apotheosis as a TV miniseries with Kenneth Branagh and Emma Thompson. It is quite wonderfully moving and good, I think - far better than the follow-up, The Levant Trilogy. Nor did the TV adaptation really do it justice.

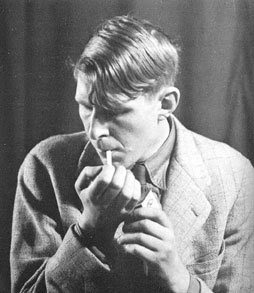

Alchetron: Edmund Crispin (1962)

Alchetron: Edmund Crispin (1962)I suppose that it shouldn't really come as a surprise that Crispin was so astute and pleasure-of-reading-focussed a critic. His distinguished series of anthologies of SF, crime, and horror stories did a great service to the dissemination of each of these forms on the UK literary scene, in particular. But they travelled as far as little ol' New Zealand, too.

As John Clute puts it in his magisterial Encyclopedia of Science Fiction :

Crispin's work in sf Anthologies was of great influence. When Best SF (1955) appeared it was unique in several ways: its editor was a respected literary figure; its publisher, Faber and Faber, was a prestigious one; and it made no apologies or excuses for presenting sf as a legitimate form of writing. Moreover, Crispin's selection of stories showed him to be thoroughly familiar with sf in both magazine and book form, and his introductions to this and succeeding volumes were informed and illuminating ... It would be difficult to exaggerate the importance of the early volumes in this series in working towards the establishment of sf in the UK as a respectable branch of literature.

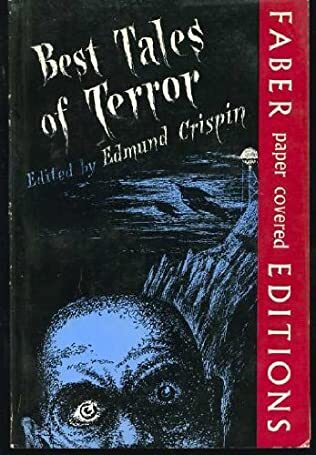

Edmund Crispin, ed.: Best Tales of Terror (1962)

Edmund Crispin, ed.: Best Tales of Terror (1962)All I can add is that it was in one of his Tales of Terror anthologies that I first encountered Elizabeth Jane Howard's classic ghost story 'Three Miles Up', and for that I remain eternally grateful.

The Passing Tramp: Bruce & Ann Montgomery (1976)

The Passing Tramp: Bruce & Ann Montgomery (1976)•

Edmund Crispin

Edmund CrispinRobert Bruce Montgomery

['Edmund Crispin']

(1921-1978)

Novels:

Edmund Crispin: The Case of the Gilded Fly (1944)

Edmund Crispin: The Case of the Gilded Fly (1944)The Case of the Gilded Fly [US title: Obsequies at Oxford] (1944)The Case of the Gilded Fly. 1944. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1946.

The wartime production of a new play in Oxford is disrupted by the murder of one of the actresses. The novel includes a set-piece recounting of a ghost story by an old Don very much in the style of M. R. James.Holy Disorders (1945)Included in: The Second Gollancz Detective Omnibus: Whose Body?, by Dorothy L. Sayers / The Weight of the Evidence, by Michael Innes / Holy Disorders, by Edmund Crispin. 1923, 1943 & 1945. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1952.

A series of sinister murders by Nazis in a cathedral town are counterpointed by an old ghost legend about an organ loft.The Moving Toyshop (1946)Included in: The Gollancz Detective Omnibus: The Moving Toyshop, by Edmund Crispin / Appleby’s End, by Michael Innes / Unnatural Death, by Dorothy L. Sayers. 1946, 1945 & 1927. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1951.

A Chestertonian poet goes looking for adventure, but ends up being coshed over the head in a toyshop in Oxford.Swan Song [US title: Dead and Dumb] (1947)Swan Song. 1947. A Four Square Crime Book. London: The New English Library Limited, 1966.

A postwar production of Wagner's Die Meistersinger is plagued with problems - including the suicide (or is it murder?) of one of the principal singers.Love Lies Bleeding (1948)Love Lies Bleeding. 1948. Penguin Crime Fiction. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1982.

An invitation to present prizes at a girl's school puts Fen on the trail of a Shakespearean discovery of epoch-making importance. Will Love's labours finally be won?Buried for Pleasure (1948)Buried for Pleasure. 1948. Penguin Books 1292. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1958.

Fen stands for Parliament in a rural district. Halfway through the campaign he realises he doesn't want the job.Frequent Hearses [US title: Sudden Vengeance] (1950)Frequent Hearses. 1950. Penguin Crime Fiction. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1982.

A loving tribute to the postwar British film industry - for which Bruce Montgomery composed so many scores - in the unlikely form of an abortive bio-pic about Alexander Pope.The Long Divorce [US title: A Noose for Her] (1951)The Long Divorce. 1952. Penguin Books 1304. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1961.

Someone is sending poison-pen letters in the small village where Gervase Fen is temporarily domiciled. Could something so trivial have led to murder?The Glimpses of the Moon (1977)The Glimpses of the Moon. 1977. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1981.

Fen is on sabbatical in a small Devon village plagued by a series of gruesome murders and dismemberments. A rich cast of characters are permitted to indulge their eccentricities to the utmost, until the actual murders become perhaps the least notable feature of the book.

Short Story Collections:

Edmund Crispin: Beware of the Trains (1953)

Edmund Crispin: Beware of the Trains (1953)Beware of the Trains (1953) [BT]Beware of the TrainsHumbleby AgonistesThe Drowning of Edgar FoleyLacrimae RerumWithin the GatesAbhorred ShearsThe Little RoomExpress DeliveryA Pot of PaintThe Quick Brown FoxBlack for a FuneralThe Name on the WindowThe Golden MeanOtherwhereThe Evidence for the CrownDeadlock Beware of the Trains. 1953. Penguin Classic Crime. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1987. Fen Country (1979) [FC]Who Killed Baker?Death and Aunt FancyThe Hunchback CatThe Lion's ToothGladstone's CandlestickThe Man Who Lost His HeadThe Two SistersOutrage in StepneyA Country to SellA Case in CameraBlood SportThe PencilWindhover CottageThe House by the RiverAfter EvensongDeath Behind BarsWe Know You're Busy Writing, But We Thought You Wouldn't Mind If We Just Dropped in for a MinuteCash on DeliveryShot in the DarkThe Mischief DoneMerry-Go-RoundOccupational RiskDog in the Night-TimeMan OverboardThe Undraped TorsoWolf! Fen Country: Twenty-Six Stories. 1979. Penguin Crime Fiction. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1981.

Edited:

Edmund Crispin, ed.: Best SF: Science Fiction Stories (1955)

Edmund Crispin, ed.: Best SF: Science Fiction Stories (1955)Best SF (1954)Best SF: Science Fiction Stories. 1954. London: Faber, 1962. Best SF 2 (1956)Best SF Two: Science Fiction Stories. 1956. London: Faber, 1964. Best SF 3 (1958)Best SF Three: Science Fiction Stories. 1958. London: Faber, 1963. Best SF 4 (1961)Best SF Four: Science Fiction Stories. 1961. London: The Science Fiction Book Club, 1962. Best SF 5 (1963)Best SF Five: Science Fiction Stories. 1963. London: Faber, 1971. Best SF 6 (1966)Best SF 7 (1970)

Best Detective Stories (1959)Best Detective Stories 2 (1964)

Best Tales of Terror (1962)Best Tales of Terror. 1962. London: Faber, 1966. Best Tales of Terror 2 (1965)

The Stars And Under: A Selection of Science Fiction (1968)Outwards From Earth: A Selection of Science Fiction (1974)

Best Murder Stories (1971)Best Murder Stories 2 (1973)

Secondary:

Whittle, David. Bruce Montgomery / Edmund Crispin: A Life in Music and Books (Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Group, 2007)

Edmund Crispin: Buried for Pleasure (1948)

Edmund Crispin: Buried for Pleasure (1948)

Published on May 13, 2022 15:01

May 6, 2022

SF Luminaries: Orson Scott Card

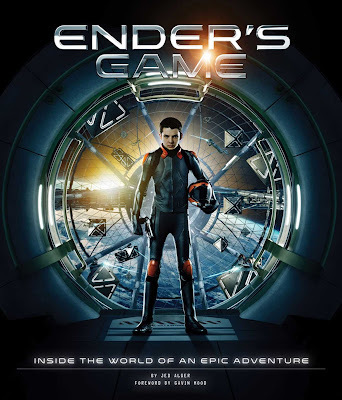

Gavin Hood, dir.: Ender's Game (2013)

Gavin Hood, dir.: Ender's Game (2013)Back in the early nineties when I was working as an English tutor at Auckland University, I was asked to supervise a research essay by one of the undergraduates. It was on Science Fiction, so no-one else felt sufficiently qualified, I suppose.

I don't remember all that much about the project, but I do recall some very interesting discussions with my supervisee about the overall tenor of SF as a genre. There's always been a good deal of talk - mainly by the more starry-eyed writers in the field - about the 'sense of wonder' and imaginative openness encouraged by its speculative, open-ended nature.

Orson Scott Card: Maps in a Mirror (1990)

Orson Scott Card: Maps in a Mirror (1990)However, I'd recently been reading Orson Scott Card's short story collection Maps in a Mirror, and its general tendency seemed quite otherwise. What stood out most for me in his work was an obsessive preoccupation with violence. There was one story in particular whose protagonist was killed in the most gruesome manner, then repeatedly revived by the authorities for further executions: his crime of dissent was such that mere death was regarded as insufficient punishment.

That's not all there was to the story, mind you. Its hero was finally sent into exile as the government had failed to break his indomitable will, so there was (at least ostensibly) a 'moral' purpose to it all. But the sheer detail supplied about the various methods of execution employed by his oppressors showed a kind of sadistic glee which seemed, to say the least, a little troubling.

Frank Herbert: The Dosadi Experiment (1977)

Frank Herbert: The Dosadi Experiment (1977)It put me in mind of Frank Herbert's late novel The Dosadi Experiment, which extended his notions on the necessity of extreme suffering to "train the faithful" (as expounded in Dune and its sequels) to almost ridiculous extremes. The more oppression is heaped upon people, the more likely it appears to be - in Herbert's view, at any rate - that you will end up with a race of super-beings.

I'd long been aware of the quasi-fascistic tendencies of (especially) the later work of Robert Heinlein and other Campbell-era SF writers, but this seemed an even more extreme doctrine - one which operated behind the overt scaffolding of the stories to imply a more sinister agenda.

I suspect that the student I was supervising began to think that I had a real bee in my bonnet on the subject of these subliminal themes in contemporary SF. He certainly showed little patience for the subject. At the time it seemed to me a legitimate exploration of the figure in the carpet for at least a few of its principal exponents, however.

Recently I've been catching up with some of Orson Scott Card's work from the thirty years since that short story collection, which spanned only the first two decades of his career. It's been a very interesting experience. He's always been a prolific writer, as you can see from the (partial) listings below, but of late a good deal of his energy seems to have gone into comics, games, and collaborations with other writers rather than the paperback novels that made his reputation.

Orson Scott Card: The Ender Series (1985-2008)

Orson Scott Card: The Ender Series (1985-2008)The first, and undoubtedly the best known of his story-cycles was first known as the 'Ender's Game Trilogy', then the 'Ender's Game Quartet', and finally the 'Ender's Game Series' as successive volumes were added.

The original 1985 novel, an expansion of his 1977 Analog novella "Ender's Game", remains an SF masterpiece. The ethical dilemmas involved in training children for a war which only they can win - without telling them that that's what you're doing - remain sharply relevant to this day. And the 2013 feature film did a pretty good job of encapsulating these themes in its (inevitably) truncated form - except for Sir Ben Kingsley's "Kiwi" accent, that is, which had to be heard to be believed.

After that things got a bit more complicated. First Card decided to send his hero off on a series of relativistic hops through the universe which took him a couple of thousand years into the future; then he landed him on a planet where the literally 'inhuman' values of another alien race, the Pequeninos (or "Piggies"), led to an even more complex conflict and the threat of another Xenocide.

This new conundrum takes a good three volumes to resolve, mainly owing to the tendency of Card's characters to sit down and talk things through - at inordinate length - on a regular basis. In the process Ender gets married to a typical Card heroine: stubborn, irritable, and prone to taking perverse, self-destructive decisions whenever reason threatens to prevail. I'm not quite sure what that implies, but it does make you wonder a bit about Card's own personal experience in this area ...

Orson Scott Card: The Shadow Series (1999-2005)

Orson Scott Card: The Shadow Series (1999-2005)But wait, there's more. Meanwhile, back on earth, the cast of the original Battle School set up to defeat the Formics (or "Buggers") are all still battling to restore the government of Earth to its proper state of blind obedience to the Hegemon, Ender's sociopathic brother Peter. All of that takes another four (or five, depending on how you count) volumes to settle.

Orson Scott Card & Aaron Johnston: The First Formic War Series (2012-14)

Orson Scott Card & Aaron Johnston: The First Formic War Series (2012-14)I can't speak to the events in the First (and now Second) Formic War Trilogies, as I haven't read them. All one can conclude is that any rumours of Ender's having actually ended hostilities with the Formics at the conclusion of Ender's Game appear to have been greatly exaggerated.

Nor has this series of spin-offs concluded as yet. And presumably there are many hardcore fans out there who are still anxiously watching this space ...

Orson Scott Card: The Tales of Alvin Maker (1987-2003)

Orson Scott Card: The Tales of Alvin Maker (1987-2003)Card's second major series is the alternate-history, American-frontier saga collectively labelled the (tall) Tales of Alvin Maker. Card's Mormonism comes through far more strongly in these books than in the Ender ones. Nevertheless, his vision of a North America half of which still belongs to the Native American tribes is a strangely inspiring one. And there's an infectious exuberance to (especially) the early volumes in the sequence which keeps you reading even as they become gradually more and more encumbered by plot and backstory.

There is still, apparently, one volume of tales to come, though I have my doubts about that. Card has a tendency to divide and subdivide his novels into they fill two or three volumes rather than just the one he originally promised. And his characters are so very, very talkative.

Orson Scott Card: The Homecoming Series (1992-95)

Orson Scott Card: The Homecoming Series (1992-95)A good example of this is the series above, originally intended as a trilogy, which grew into a huge, sprawling, five-volume saga.

I think that if I knew more about The Book of Mormon (had read it, for instance), I might be better equipped to judge these books. It is, it seems, a 'Science-fictional" version of the major events in the Mormon scriptures, which may account for the extreme perversity of many of the characters' basic motivations.

The hero, Nafai, for example, seems almost infinitely long-suffering, and his evil, plotting brothers, Elemak and Mebbekew, almost impossibly villainous. There is a certain narrative drive which kept me reading, but it does seem to be intended for a more specialised audience than most of his other fiction.

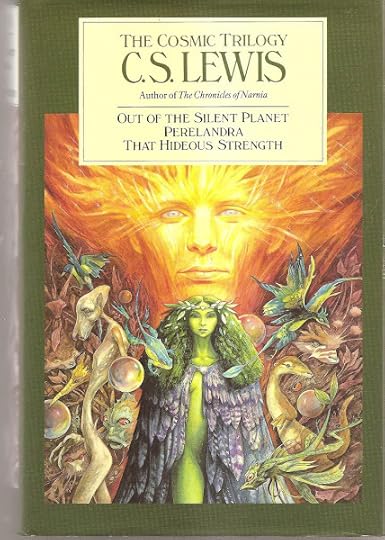

C. S. Lewis: The Cosmic Trilogy (1938-45)

C. S. Lewis: The Cosmic Trilogy (1938-45)What, then, is one to conclude about Orson Scott Card? Ender's Game remains a fine novel. Many of his other novels are also well worth reading, too - particularly the 'Alvin Maker' series. I wouldn't myself say that his experiment of mixing Mormon themes with the matter of conventional genre fiction has been a particularly successful one, but then the same could easily be said of other such ideologically driven Speculative Fiction such as C. S. Lewis's Interplanetary trilogy, or even Charles Williams' theological thrillers.

So I find myself inscribing a tick in the "yes" column, despite my reservations about the endless blah-blah in (especially) his later books, and despite my nagging suspicions of a certain residual sadism and misogyny at the root of much of his fiction. Once again, the same could be said of many canonical authors, and this inference remains, in any case, a debatable one.

Orson Scott Card: Assorted Enderverse Comics (1938-45)

Orson Scott Card: Assorted Enderverse Comics (1938-45)•

Orson Scott Card

Orson Scott CardOrson Scott Card

(1951- )

The Enders Game Series:

Ender’s Game. The Ender Quartet, 1. 1985. A Legend Book. London: Arrow Books Ltd., 1988.Speaker for the Dead. The Ender Quartet, 2. 1986. A Legend Book. London: Arrow Books Ltd., 1986.Xenocide. The Ender Quartet, 3. 1991. A Legend Book. London: Arrow Books Ltd., 1992.Children of the Mind. The Ender Quartet, 4. 1996. A Tor Book. New York: Tom Doherty Associates, LLC, 1997.Ender's Shadow. 1999. The Shadow Saga, 1. An Orbit Book. London: Little, Brown and Company (UK), 2000.Shadow of the Hegemon. 2000. The Shadow Saga, 2. An Orbit Book. London: Little, Brown and Company (UK), 2001.Shadow Puppets. 2002. The Shadow Saga, 3. A Tor Book. New York: A Tom Doherty Associates Book, 2003.Shadow of the Giant. 2005. The Shadow Saga, 4. A Tor Book. New York: A Tom Doherty Associates Book, 2006.First Meetings in the Enderverse. An Orbit Book. London: Time Warner Books UK, 2003.A War of Gifts: An Ender Story (2007)Ender in Exile (2008)Shadows in Flight. The Shadow Saga, 5 (2012)[with Aaron Johnston] Earth Unaware. First Formic Wars trilogy, 1 (2012)[with Aaron Johnston] Earth Afire. First Formic Wars trilogy, 2 (2013)[with Aaron Johnston] Earth Awakens. First Formic Wars trilogy, 3 (2014)[with Aaron Johnston] The Swarm. Second Formic Wars trilogy, 1 (2016)Children of the Fleet. Fleet School (2017)Ender's Way: short stories (2021)[with Aaron Johnston] The Hive. Second Formic Wars trilogy, 2 (2019)The Last Shadow. The Shadow Saga, 6 (2021)[with Aaron Johnston] The Queens. Second Formic Wars trilogy, 3 (tba)

The Tales of Alvin Maker:

Seventh Son. The Tales of Alvin Maker, 1. 1987. A Legend Book. London: Arrow Books Ltd., 1989.Red Prophet. The Tales of Alvin Maker, 2. 1988. An Orbit Book. London: Little, Brown and Company (UK), 2001.Prentice Alvin. The Tales of Alvin Maker, 3. 1989. An Orbit Book. London: Little, Brown and Company (UK), 2001.Alvin Journeyman. The Tales of Alvin Maker, 4. 1995. An Orbit Book. London: Little, Brown and Company (UK), 2001.Heartfire. The Tales of Alvin Maker, 5. An Orbit Book. London: Little, Brown and Company (UK), 2001.The Crystal City. The Tales of Alvin Maker, 6 (2003)Master Alvin. The Tales of Alvin Maker, 7 (tba)

The Homecoming Series:

The Memory of Earth. Homecoming, 1. 1992. Legend Books. London: Random House UK Ltd, 1993.The Call of Earth. Homecoming, 2. 1993. A Tor Book. New York: A Tom Doherty Associates Book, 1994.The Ships of Earth. Homecoming, 3. 1994. A Tor Book. New York: A Tom Doherty Associates Book, 1995.Earthfall. Homecoming, 4. 1995. A Tor Book. New York: A Tom Doherty Associates Book, 1996.Earthborn. Homecoming, 5. 1995. A Tor Book. New York: A Tom Doherty Associates Book, 1996.

Women of Genesis:

Sarah (2000)Rebekah (2001)Rachel and Leah (2004)

The Empire Duet:

Empire (2006)Hidden Empire (2009)

The Pathfinder Series:

Pathfinder (2010)Ruins (2012)Visitors (2014)

The Mithermages Series:

The Lost Gate (2011)The Gate Thief (2013)Gatefather (2015)

Miscellaneous Novels:

A Planet Called Treason [aka Treason (1988)] (1979)Songmaster. 1980 & 1987. A Legend Book. London: Arrow Books Ltd., 1990.Hart's Hope (1983)Saints [aka Woman of Destiny] (1983)Wyrms. 1987. A Legend Book. London: Arrow Books Ltd., 1988.with Lloyd Biggle, Jr.] Eye for Eye / Tunesmith. Tor double novel (1990)Lost Boys (1992)[with Kathryn H. Kidd] Lovelock (1994)Pastwatch: The Redemption of Christopher Columbus (1996)/li>Treasure Box (1996)Stone Tables (1997)Homebody (1998)Enchantment (1999)[with Doug Chiang] Robota (2003)Magic Street (2005)[with Aaron Johnston] Invasive Procedures (2007)A Town Divided by Christmas (2018)Lost and Found (2019)

Short Story Collections:

The Worthing Saga. ['Capitol' (1979); 'The Worthing Chronicle' (1982)]. A Legend Book. London: Random Century Group, 1991.The Folk of the Fringe. 1990. A Legend Book. London: Random Century, 1991.Maps in a Mirror. 1990. 2 vols. A Legend Book. London: Arrow Books Ltd., 1992.Keeper of Dreams (2008)

Poetry:

An Open Book (2004)

For Children:

Magic Mirror (1999)

Non-fiction:

Listen, Mom and Dad (1977)Ainge (1981)Saintspeak (1981)Characters and Viewpoint (1988)How to Write Science Fiction and Fantasy (1990)A Storyteller in Zion (1993)Complete Guide to Writing Science Fiction: Volume One, First Contact (2007)

Edited:

Dragons of Light (1980)Dragons of Darkness (1981)Future on Fire (1991)Future on Ice (1998)Masterpieces (2001)The Phobos Science Fiction Anthology, Volume 1 (2002)The Phobos Science Fiction Anthology, Volume 2 (2003)The Phobos Science Fiction Anthology, Volume 3 (2004)Orson Scott Card's InterGalactic Medicine Show (2008))

•

Orson Scott Card: Ender's Game (1985)

Orson Scott Card: Ender's Game (1985)

Published on May 06, 2022 16:38

May 2, 2022

James Hogg: Confessions of a Justified Sinner

Andrew Currie: Monument to James Hogg (St. Mary's Loch)

While I was living in Edinburgh in the late 1980s, a friend of mine, Martin Frost, and I were in the habit of driving madly around the countryside of Scotland in his tiny Mini in search of cups of coffee and chocolate cake - perhaps also in a vain attempt to evade the inevitable consequences of continued inattention to our studies ... "An element of pleasure-seeking there," as a cousin of mine, Roddie Macleod, remarked of a neighbouring farmer who'd been in the habit of going into Dundee from time to time to disport himself. If such a thing is possible in Dundee, that is.

On one of these expeditions, we happened upon St. Mary's Loch, and found the statue above, dedicated to the famed Ettrick Shepherd, James Hogg, but memorable mainly for the inscription on its base, the rather extravagant encomium:

He taught the wandering winds to singSince then I've discovered that that is the last line of his book-length poem The Queen’s Wake (1813), so perhaps it wasn't quite so vainglorious as I imagined.

James Hogg: The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824 / 1970)

I'm not sure if I'd read his novel The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner at the time. If not, it must have been shortly afterwards, because I remember that it had an electrifying effect on me. Why had I never heard of this novel before? It was every bit the equal of - possibly even better than - Stevenson's Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, and the sheer intensity and strangeness of the writing would be hard to match outside the works of De Quincey or even Edgar Allan Poe.

It does, in fact, bear a certain resemblance to such doppelgänger stories as Poe's "William Wilson" (1839) or Melville's "Bartleby, the Scrivener" (1853), though of course it long preceded them. The title may owe something to De Quincey's Confessions of an English Opium Eater (1821), but they have little else in common.

James Hogg: The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824 / 1947)

James Hogg: The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824 / 1947)In 1947, in his introduction to a new edition of the complete, uncensored text of Hogg's novel, the Nobel prize winner for that year, André Gide, confessed that he had read 'this astounding book ... with a stupefaction and admiration that increased at every page'. So, just as in the case of Poe, it was largely the admiration of the French (Baudelaire and Mallarmé for Poe; Gide for Hogg) that first plucked these great writers from provincial obscurity and brought their work to the attention of readers everywhere.

As you can see in the bibliography below, the pruned and bowdlerised versions of Victorian editors have been succeeded by a complete, textually rigorous edition of James Hogg's Collected Works. Whatever form you read it in, though, The Confessions of a Justified Sinner is every bit as important a text in the Fantastic tradition as Potocki's Manuscript Found in Saragossa (1805-15) or Schiller's Ghost-Seer (1787-1789). Indeed, it rivals Frankenstein itself.

James Hogg: The Works of the Ettrick Shepherd (vol. 1 of 2: 1865)

James Hogg: The Works of the Ettrick Shepherd (vol. 1 of 2: 1865)It was therefore with a great deal of excitement that I came across a copy of The Works of the Ettrick Shepherd in Devonport the other day. Admittedly, it was in an edition "Revised at the Instance of the Author's Family, by the Rev. Thomas Thomson," which hardly inspires one with confidence in its textual integrity, but even this atmosphere of pious disdain for Hogg's "crudities" has its points of interest.

Hogg's reputation had suffered greatly from the caricatured version of him presented, under the name "the Ettrick Shepherd", in Noctes Ambrosianae , a popular series of feigned conversations which appeared in Blackwoods Magazine between 1822 and 1835. The Shepherd, a Scots-spouting buffoon, is generally upstaged by the more urbane "Christopher North" (Professor John Wilson - himself the author of most of the dialogues) and his friends "Timothy Tickler" (Robert Sym) and - occasionally - "The English Opium Eater" (Thomas De Quincey).

Hogg, who had little part in the concoction of most of these pieces, made no public comment on the matter. However (according to Wikipedia, at any rate) "some of his letters to Blackwood and others express outrage and anguish." Certainly this picture of him as "a part-animal, part-rural simpleton, and part-savant" coloured his reputation throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth century.

A chance remark by Hogg to Wordsworth describing the two of them as fellow bards was greeted with some disdain by the English poet. His 1835 "Extempore Effusion upon the Death of James Hogg" includes the following stanza:

The mighty Minstrel breathes no longer,However, the first two of these lines probably refer to Sir Walter Scott. Wordsworth's own notes on the poem say of Hogg: "He was undoubtedly a man of original genius, but of coarse manners and low and offensive opinions."

'Mid mouldering ruins low he lies;

And death upon the braes of Yarrow,

Has closed the Shepherd-poet's eyes.

James Hogg: A Queer Book (2007)

James Hogg: A Queer Book (2007)All this patronising nonsense about his having somehow been a genius in spite of himself has hopefully now been laid to rest, however. Hogg is increasingly seen as a pillar of Scottish literature, in the tradition of Burns, Scott and Stevenson, as well as a profound influence on writers as diverse as George Douglas Brown, Alasdair Gray and Irvine Welsh.

Eden Ashley: Arthur's Seat and Salisbury Crags (Edinburgh) (2022)

Eden Ashley: Arthur's Seat and Salisbury Crags (Edinburgh) (2022)For myself, I think that it was partly the fact that I was living right in the middle of the place where his novel is set which lent the book such an extraordinary atmosphere for me. I boarded in a Hall of Residence sited directly below Arthur's Seat, and sat on the edge of Salisbury crags reading Baudelaire on more than one occasion.

The Brocken Spectre (2006)

The Brocken Spectre (2006)The scene in Hogg's novel where the narrator sees the approach of an extraordinary apparition (which turns out to be a version of the famous Brocken spectre) was therefore located right on my front doorstep.

Thomas Keith: The Grassmarket, Edinburgh (c.1850)

Thomas Keith: The Grassmarket, Edinburgh (c.1850)Nor has the rest of the city changed much since the nineteenth century. There's still the Old Town running down the Royal Mile from the Castle to Holyrood Abbey; the 18th-century New Town, with its Palladian squares and crescents, off to one side of it; and then all the Victorian infill housing shading off to the South. Such landmarks as the Cowgate and the Grassmarket remain pretty much as they were in Hogg's time.

It's strange for someone from the Antipodes to reside in so changeless a place, with the ghosts walking around right in front of you rather than drowned in a sea of new construction. Not restful, exactly, but somehow very satisfying to anyone with a strong sense of tradition.

If you've never read his novel, I envy you your first experience of it. Make sure that you choose the right text, though. The older editions of Hogg are quite unreliable. What you want is one based on the 1824 version - as most of them now fortunately are. It's not a case like Frankenstein where both texts, the 1818 one and Mary Shelley's 1831 revision, have their own points of interest. There's little evidence that Hogg had much - if anything - to do with the posthumous 1837 reprint of his novel, and (as Wikipedia puts it) "the extensive bowdlerization and theological censorship in particular suggest publisher's timidity."

James Hogg: The Works of the Ettrick Shepherd (c.1874)

James Hogg: The Works of the Ettrick Shepherd (c.1874)•

Sir John Watson Gordon: James Hogg, The Ettrick Shepherd (1830)

James Hogg

(1770-1835)

Works:

The Works of the Ettrick Shepherd: Centenary Edition. Revised at the Instance of the Author's Family, by the Rev. Thomas Thomson. 2 vols. 1865. With Many Illustrative Engravings. London, Edinburgh & Glasgow: Blackie & Son, 1878. Tales and Sketches Poems and Ballads: With a Memoir of the Author

The Stirling / South Carolina Research Edition of the Collected Works of James Hogg. Series Editors: Ian Duncan & Suzanne Gilbert. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1995-2021.The Mountain Bard. 1807. Ed. Suzanne Gilbert (2007)The Forest Minstrel. 1810. Ed. P. D. Garside & Richard D. Jackson (2006)The Spy: A Periodical Paper of Literary Amusement and Instruction. 1810-11. Ed. Gillian Hughes (2000)The Queen's Wake: A Legendary Poem. 1813. Ed. Douglas S. Mack (2004)Mador of the Moor. 1816. Ed. James E. Barcus (2005)The Jacobite Relics of Scotland, Vol. 1: First Series. 1819. Ed. Murray G. H. Pittock (2002)The Jacobite Relics of Scotland, Vol. 2: Second Series. 1821. Ed. Murray G. H. Pittock (2003)Winter Evening Tales: Collected Among the Cottagers in the South of Scotland. 1820. Ed. Ian Duncan (2002)The Bush aboon Traquair and The Royal Jubilee. 1822. Ed. Douglas S. Mack (2008)Midsummer Night Dreams and Related Poems. 1822. Ed. J. H. Rubenstein, Gillian Hughes & Meiko O'Halloran (2008)The Three Perils of Man: or War, Women, and Witchcraft: A Border Romance. 1822. Ed. Judy King and Graham Tulloch (2012)The Three Perils of Woman: or; Love, Leasing, and Jealousy: a series of Domestic Scottish Tales. 1823. Eds David Groves, Antony Hasler, & Douglas S. Mack (1995)The Three Perils of Woman, or Love, Leasing, and Jealousy: a Series of Domestic Scottish Tales. 1823. Ed. David Groves, Antony Hasler, & Douglas S. Mack. The Stirling / South Carolina Research Edition of the Collected Works of James Hogg. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1995. The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner: Written by Himself; With a Detail of Curious Traditionary Facts and Other Evidence by the Editor. 1824. Ed. P. D. Garside (2001)The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, Written by Himself: With a Detail of Curious Traditionary Facts and Other Evidence by the Editor. 1824. Ed. P. D. Garside. Afterword by Ian Campbell. Chronology by Gillian Hughes. The Stirling / South Carolina Research Edition of the Collected Works of James Hogg. 2001. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010. Queen Hynde. 1824. Ed. Suzanne Gilbert & Douglas S. Mack (1998)The Shepherd's Calendar. 1829. Ed. Douglas S. Mack (1995)Songs by the Ettrick Shepherd. 1831. Ed. Kirsteen McCue & Janette Currie (2014)Altrive Tales, Featuring a ‘Memoir of the Author’s Life’. 1832. Ed. Gillian Hughes (2003)A Queer Book. 1832. Ed. P. D. Garside (1995)Anecdotes of Scott. 1834. Ed. Jill Rubenstein (1999)A Series of Lay Sermons: on Good Principles and Good Breeding. 1834. Ed. Gillian Hughes (1997)Tales of the Wars of Montrose. 1835. Ed. Gillian Hughes (1996)Highland Journeys. 1802-4. Ed. by H. B. de Groot (2010)Contributions to Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Vol. 1: 1817–1828. Ed. Thomas C. Richardson (2008)Contributions to Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Vol. 2: 1829–1835. Ed. Thomas C. Richardson (2012)Contributions to English, Irish and American Periodicals. Ed. Adrian Hunter & Barbara Leonardi (2020)Contributions to Scottish Periodicals. Ed. Graham Tulloch & Judy King (2021)Contributions to Annuals and Gift-Books. Ed. Janette Currie, Gillian Hughes (2006)Contributions to Musical Collections and Miscellaneous Songs. Ed. Kirsteen McCue (2015)The Collected Letters of James Hogg, Vol. 1: 1800–1819. Ed. Gillian Hughes (2004)The Collected Letters of James Hogg, Vol. 2: 1820–1831. Ed. Gillian Hughes (2006)The Collected Letters of James Hogg, Vol. 3: 1832–1835. Ed. Gillian Hughes (2008)

James Hogg: The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824 / 2006)

James Hogg: The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824 / 2006)Novels:

The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, Written by Himself: With a Detail of Curious Traditionary Facts and Other Evidence by the Editor. 1824. Ed. John Carey. Oxford English Novels. 1969. London: Oxford University Press, 1970.

The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, with 'Marion's Jock' and 'John Gray o' Middleholm'. 1824, 1832 & 1820. Ed. Karl Miller. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin, 2006.

Karl Miller: Electric Shepherd (2003)

Secondary:

Miller, Karl. Electric Shepherd: A Likeness of James Hogg. London: Faber, 2003.

James Hogg: The Suicide's Grave (1895)

James Hogg: The Suicide's Grave (1895)

Published on May 02, 2022 19:13

March 30, 2022

The Material Interests: Reading Joseph Conrad

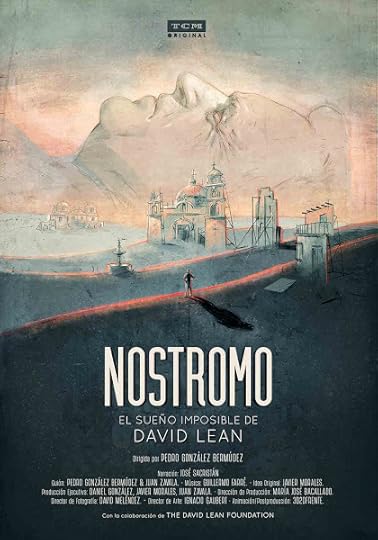

Pedro González Bermúdez, dir.: David Lean's Nostromo: The Impossible Dream (2017)

Pedro González Bermúdez, dir.: David Lean's Nostromo: The Impossible Dream (2017)The other night Bronwyn and I watched a documentary on TVNZ-on-Demand about David Lean's abortive attempts to make a feature film of Joseph Conrad's 1904 novel Nostromo. I already knew something about this project, both from Kevin Brownlow's exhaustive biography of the director, and also from the Faber edition of Christopher Hampton's filmscript for the project.

Christopher Hampton: The Secret Agent and Nostromo (Faber Filmscripts, 1996)

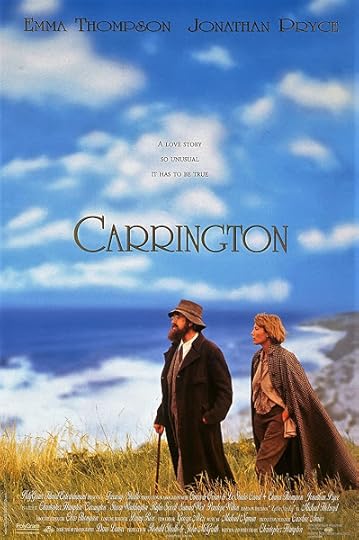

Christopher Hampton: The Secret Agent and Nostromo (Faber Filmscripts, 1996)Don't get me started on Christopher Hampton. I think he's one of the great unsung heroes of our time in both theatre and film. His filmscripts are brilliantly imaginative (Atonement, The Honorary Consul, The Father - those are all his); he won an Oscar for Dangerous Liaisons (a screenplay based on his own successful stage adaptation of Laclos's 1782 novel); and he directed his own screenplay for Carrington, one of my and Bronwyn's all-time favourite movies.

Christopher Hampton, dir. & writ.: Carrington (1995)

Christopher Hampton, dir. & writ.: Carrington (1995)Hampton's credentials as an imaginative interpreter of South America are also pretty impressive. He adapted Graham Greene's 1973 novel The Honorary Consul, set in Argentina, for the screen (as I mentioned above), but it's his own play Savages , about the genocide of the Amazonian Indians, which really shows his ability to transport himself imaginatively into that uneasy space where politics meets creativity.

Christopher Hampton: Savages (1974)

Christopher Hampton: Savages (1974)In short, what a dream team! David Lean, the 'poet of the far horizon', the epic filmmaker par excellence; the sharpwitted theatrical chameleon Christopher Hampton; and the longest, most complex novel Joseph Conrad - one of the greatest writers of all time - ever wrote. What could possibly go wrong?

Well, lots of things, obviously. I'll leave it to you to watch the whole dreary saga in Pedro González Bermúdez's documentary if such things interest you. Suffice it to say that the irresistible force of money ran into the various immovable egos involved in the project, and the whole thing ended in tears and acrimony. All we're left with is a tantalising might-have-been, like Stanley Kubrick's Napoleon or Orson Welles' Heart of Darkness ...

Joseph Conrad: Nostromo: A Tale of the Seaboard (1904)

Joseph Conrad: Nostromo: A Tale of the Seaboard (1904)I guess what struck me about the tiny fragments of Nostromo included in the documentary, though, was how little most of the speakers seemed to know about the book. I realise it has a rather fearsome reputation. One of the Academics interviewed remarked with a chuckle that he had to tell his students that they shouldn't worry if nothing in it made sense for the first seventy pages or so - after that it would all come into focus. Others opined that 100 or even 200 pages of exposition were required before the action really started to kick in. Clearly an ideal choice for a feature film ...

The main problem, of course, is that Conrad's novel isn't really about the character 'Nostromo' [short for nostro uomo, Italian for "Our Man" - a little like Graham Greene's Our Man in Havana]. Nostromo is certainly an important part of the plot. As the 'Capataz de Cargadores' [Captain of the Stevedores], he controls the workers at the port which is the lifeblood of the tiny town of Sulaco. But he remains a somewhat shadowy, enigmatic figure till the end - more like Kurtz in Heart of Darkness than Lord Jim in the novel of that name.

So why should I bother to read it, then? I hear you saying. Quite. Why struggle through an immensely long and detailed account of a revolution in a far-off (imaginary) Latin American country, written by a Polish novelist for whom English was not even a second but a third or fourth language, who had one brief day's sojourn ashore as his sole experience of the entire continent of South America?

When it comes to South-East Asia, Continental Europe, Great Britain - even Africa - Conrad had a rich stock of local knowledge to draw on. He knew the Congo river and how to navigate it (Heart of Darkness); he'd lived as a poor émigré in London (The Secret Agent); he was born and grew up in Central and Eastern Europe (Under Western Eyes); he'd sailed around the intricate islands and bays of the Malay archipelago (Almayer's Folly). But he certainly couldn't claim to know South America first-hand.

It didn't really shock me, then, when I heard of David Lean's attempts to find locations for his own cinematic version of Nostromo in Cuba, Baja California, Spain, and finally the South of France - anywhere, it seems, except the Northern coast of Colombia (or Venezuela) where Conrad's imaginary country must clearly, according to internal evidence (and the subject has been extensively canvassed, I assure you) be situated.

After all, if Spain could stand in for Russia in Doctor Zhivago, why not for the Spanish-speaking republic of Costaguana?

Hollywood in España (2012)

Hollywood in España (2012)•

Joseph Conrad: Nostromo (First edition: 2004)

Joseph Conrad: Nostromo (First edition: 2004)To explain why even so eccentric-sounding and difficult a novel seems to me, at least, so eminently worth reading, I have to go back to the beginnings of my own Conrad adventure.

A long time ago, in a country far, far away - my ancestral homeland: Scotland - I was searching for a project. For some reason which seemed very cogent to me at the time, I'd decided that I wanted to be an Academic, and I knew that for that I needed to do a PhD. Even then I was as addicted to Fantasy and Sci-fi as I was to 'serious' literature, so I came up with the idea of writing an examination of imaginary countries in fiction.

Colin Manlove (1942-2020)

Colin Manlove (1942-2020)Thanks to a UK Commonwealth scholarship, I'd ended up studying at Edinburgh University, where my supervisor - a well-known historian of fantasy literature, Mr. Colin Manlove - decided that the scope of the project was too broad, and that, since I'd started off with an essay about imaginary countries in South America, I should continue along those lines, using a select set of texts to interrogate the different ways in which that region had been 'recreated' by European observers - some of them with minimal or non-existent knowledge of the actual places they were writing about.

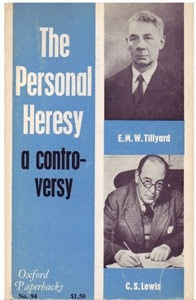

C. S. Lewis & E. M. W. Tillyard: The Personal Heresy: A Controversy (1939)

C. S. Lewis & E. M. W. Tillyard: The Personal Heresy: A Controversy (1939)Clearly Conrad was an ideal choice. His imaginary country of Costaguana is lovingly described, in immense detail, in the pages of Nostromo - the celebrated critic E. M. W. Tillyard in fact devoted a whole chapter of his book The Epic Strain in the English Novel (1958) solely to the geography of the novel - and yet it's based on little except armchair research and that one vital day ashore on the shores of the Caribbean.

Conrad is a much written-about author. He's been at the centre of the Eng. Lit. canon for quite a long time, and the books, monographs and theses are piled high on virtually every aspect of his work. Almost at once I was faced with the dilemma of how much of all this I could possibly read, and what good it would do me if I did.

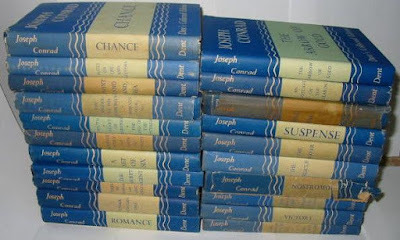

Joseph Conrad: Collected Works (New edition: 1947-57)

Joseph Conrad: Collected Works (New edition: 1947-57)Instead, I decided I would just read Conrad. And so I did. I started off on p.1 of Almayer's Folly (1896), and worked my way to the final pages of the unfinished, posthumous Suspense: A Napoleonic Novel (1925). Along the way I read all of his short stories, essays, and other materials such as journals and letters. You'll find a reasonably comprehensive listing of all that material below.

It took me quite a while. Mind you, I'd encountered some of them before, but reading them like that, in chronological sequence, taught me a lot of interesting things about Conrad I hadn't really understood before. And it also gave me a good vantage point to judge the various bits of secondary literature about him I really had to read.

I've often felt that that was a turning point for me. When it comes to a choice between knowing an author's work well, and having an intimate knowledge of the secondary literature about them, I'll always plump for the former.

This is not - to put it mildly - standard academic process. Bleating on about the conflicting views of various nobodies on some canonical work is definitely the way to get ahead in literary studies. But making any reference to other works by that writer besides the one under immediate discussion is often meant with blank looks.

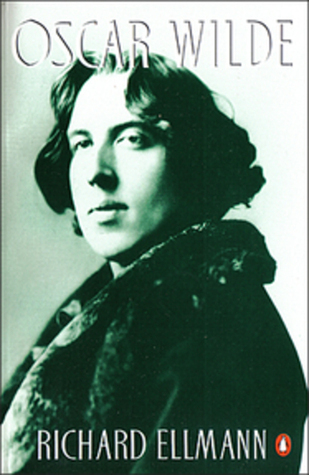

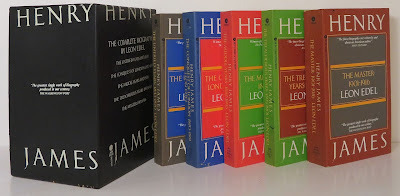

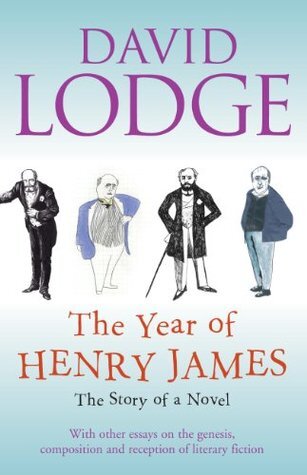

I recall once, when I worked at Auckland University, attending a talk by a visiting British professor on the nature of literary biography. Since he was primarily a James Joyce scholar, he'd decided to contrast Richard Ellmann's biography of Joyce with (I think) Deirdre Bair's biography of Samuel Beckett. It all went swimmingly until, in the q-&-a after his talk, I asked quite innocently how well he thought his conclusions applied to other classic literary biographies: Leon Edel's life of Henry James, for instance, or even Ellmann's own biographies of Yeats and Wilde?

Richard Ellmann: Oscar Wilde (1987)

Richard Ellmann: Oscar Wilde (1987)He glared at me angrily, as if I were deliberately conspiring to show him up. "I haven't read them," he grunted. I guess I was more surprised than shocked. How could one set out to pontificate about literary biography without reading at least a few of the major ones? It seems that the two he'd chosen constituted his whole knowledge of the subject ("Good enough for a tour of the provinces," he'd no doubt been reassured by his colleagues if he had felt any apprehension).

I'm afraid that that's a phenomenon I've encountered many times since then: huge generalisations based on insufficient reading, either of the author one's studying or the field as a whole.

Mind you, even way back in Biblical times the author of Ecclesiastes could lament that "of making many books there is no end; and much study is a weariness of the flesh." (Eccl, 12: 12). Nor has the situation improved much since then. It's literally impossible to keep up with all the work in one's own field nowadays, however restricted it may be, and the publications continue to pile up inexorably.

But reading Conrad! That was a joy. If you leave out the two collaborations with Ford Madox Ford, and long novellas such as "Heart of Darkness" and "Typhoon," there are only really 14 novels to cover, and even the weaker, later ones always have something unexpected to offer. If you've only ever read Nostromo, how can you possibly understand how it builds on and intensified the techniques he'd already tried out in his earlier work? How can you appreciate the incredibly swift advance in his art from the comparative crudeness of his first couple of novels to the certainty and mastery of his work in the early 1900s? It took him seven years to go from Almayer's Folly to Nostromo - an almost incredible conceptual leap.

Mind you, just sticking to the primary texts is no panacea. If you read all of Conrad, does that mean you have to read all of Arnold Bennett, Stephen Crane, Ford Madox Ford, John Galsworthy, Henry James, and H. G. Wells as well? And if you want to understand Conrad's larger literary milieu, do you have to read Flaubert, Turgenev, and Henryk Sienkiewicz, too? I suppose that the real answer is yes, but who has the time? You have to trust someone else's judgement at some stage, and there is a limit.

Nevertheless, I'd rather know Conrad well than the secondary literature on Conrad. It may not apply to every novelist, but it's certainly important for him. It can be difficult to pick up a work such as Nostromo and start to figure it out if you don't know Lord Jim or (especially) such terrifyingly deadpan early stories as "An Outpost of Progress" or "Heart of Darkness."

Conrad has a point to make. That's the vital thing to remember. Like all jobbing authors, he had to make a buck, which meant appealing to the public to some degree, but for the most part he wanted to talk about how the world actually works to an audience who'd been conditioned to demand romantic legends and fairy-tales. His work can be harsh at times, but that's one of the main reasons it's lasted - that, and his extraordinary gift for language, which still seems miraculous all these years later.

Joseph Conrad (1923)

Joseph Conrad (1923)•

Joseph Conrad: Collected Works (1925-26)

Joseph Conrad: Collected Works (1925-26)"So, after all that song and dance, what exactly do you think Nostromo is about?" I can hear you saying. "Put up or shut up!"

Well, I'm glad you asked me that. If you want to know how Nostromo fitted into the larger scheme of my thesis: the motivations (and mechanics) behind the creation of imaginary worlds, you can consult my original conclusions here. If you want to read the tidied-up version I published in Landfall a couple of years later, you can find it here.

If you want to cut straight to the chase, though, here it is: the material interests. Just that. That phrase. The material interests.

I realise that it needs some unpacking. Let me just start off by saying that where most authors treat the subject of buried treasure as an excuse for romantic derring-do and exotic locations, Conrad turns the idea on its head. What interests him about treasure is the things that financiers and the governments they control will do to maintain a steady supply of it. All the more adventurous aspects, though present, are really secondary to this sober-sided view of the realities of global supply and demand.

To explain what that means, I'll have to tell you a story. It's not a particularly glamorous story, and not one to be proud of exactly, but it's one of the main things that was in Conrad's mind as he set out to write his great novel.

Canal Crazy

Canal CrazyNot so very long ago, ships still had to navigate all the way around Cape Horn to get from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Ever since the French entrepreneur Ferdinand de Lesseps had opened the Suez Canal in 1869, at least part of the problem of how to get goods from East to West (and vice versa) had been solved, but there still remained a great bottleneck to world trade in the form of the immense double continent of the Americas.

De Lesseps tried to follow up his success with a French-backed Panama Canal project in 1879, but it ended in debt and acrimony a decade later. Which left the problem exactly where it was.

Panama Canal cartoon (1903)

Panama Canal cartoon (1903)At which point the Americans entered, stage left. It was a perfect project for the tub-thumping, sabre-waving US President Theodore Roosevelt, so - with his connivance - in 1902 the Senate voted in favour of trying to acquire suitable territory for a canal in the isthmus of Panama, then part of the Republic of Colombia.

Colombia wasn't quite so keen on this idea, so the Americans fomented a revolution in the north of their country with the sole object of creating a smaller, more malleable government with which they could deal. Sure enough, in 1903 the Republic of Panama was born, and promptly signed a deal with the US government offering them virtual sovereignty over the so-called 'canal zone'.

And so the great Panama Canal came into being, as a direct result of one of the dirtiest and most cynical bits of chicanery in contemporary history. Not that one would have to delve far into the annals of European colonialism to find even worse examples - in the Congo itself, for instance.

Conrad took careful note of all this (as he reveals through certain comments about 'Yankee conquistadors' in his correspondence with the veteran South American traveller R. B. Cunninghame Graham), and it had a part in inspiring him to put something similar at the heart of his novel - instead of the canal itself, though, we have the silver of the mine.

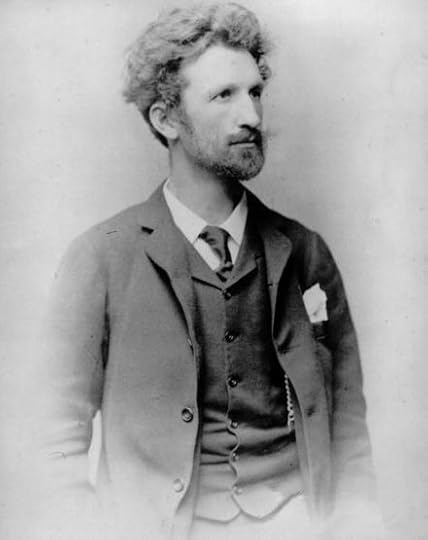

R. B. Cunninghame Grahame (1852-1936)

R. B. Cunninghame Grahame (1852-1936)It might help, at this point, to know a little more about Conrad's own background. I wrote some notes about that for my Stage Three Travel Writing course, where we contrasted his 'Congo Diary' with the written-up, fictionalised version in 'Heart of Darkness.' Here are a few of the points I made there:

Joseph Conrad (or Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, if you prefer) ... grew up speaking Polish, in Poland. And yet he didn't - because there was no such country. Prussia, Russia and Austria had divided up Poland between them in the late eighteenth century, and it didn't achieve independence again until 1918, after the First World War.Let's just say, then, that colonialism and realpolitik are never a neutral matter for Conrad. His immense suspicion of Russia's imperial ambitions, and consequent disdain for their culture, was regarded as a strange blindspot by his more complacent contemporaries in literary London, as they exclaimed over the beauties of Chekhov and Tolstoy.

Conrad's father Apollo was a writer and a patriot, and was accordingly arrested by the Tsarist authorities in 1861, when Joseph was four, and sent into exile in Siberia. Both his mother and father died as a result of the harsh conditions they were subjected to there, so Joseph was an orphan by the age of 11.

In an autobiographical essay Conrad records that he was fascinated by maps as a young boy, and particularly by the blank spot in the centre of Africa. "When I grow up I will go there," he said to himself - and, amazingly, many years later, after leaving Poland for France, and then for the British Merchant Marine, he did precisely that. He went there - to the heart of the King Leopold's private colony on the Congo river - and what he saw and brought back from that experience eventually became the story Heart of Darkness.

For me, the essential thing to remember when trying to understand this story is that Conrad was not British. His narrator and alter-ego Marlow is British - and is accordingly rather scornful of "foreigners", especially their attempts to run viable colonies. Conrad, though, as a loyal Pole, was scornful of Imperialism in all its forms - British, Russian and American - and his feelings about inhabiting a "blank spot" on the map can hardly be said to have been unambiguous either.

His is certainly an art of contrast and comparison. The fascinating thing is that it was by enlarging his terms of reference, by making his very real experience of the horror of the Belgian Congo into a fictionalised story, that he managed to create a work which has sparked so many analogues and echoes since - notably Francis Ford Coppola's 1979 Vietnam war film Apocalypse Now.

In the age of Putin, it's perhaps a little easier to understand how Conrad felt, and it's one of the many reasons that his works have such resonance today - for those who can be bothered to read them, that is. Virginia Woolf once famously remarked that George Eliot's Middlemarch was "one of the few English novels written for grownup people." One can see her point. The motivations described in that book are not really fully comprehensible to childish or even adolescent readers.

Conrad, too, almost alone among his contemporaries, was writing for grownups. The glamorous seascapes and long tropical descriptions he's most celebrated for certainly exist - and they continue to exert a strange attraction over those of us who love the world he has created. But the deep wounds inflicted by his own upbringing and the brutal suppression of his native land made it impossible for him to share the smug self-satisfaction of the rest of the English-speaking world.

The First World War hit European culture like a bomb. But even then the writers of the time could valorise it into a unique and world-shaking event: the 'war to end all wars.' Conrad knew better. Small wars kill and devastate in just the same way as global cataclysms. Greed - the material interests - and the casual cruelty it gives rise to, are something which needs to be analysed in depth if one is even to begin to understand it.

That's the main reason why Nostromo is a novel which can be spoken of in the same breath as Tolstoy's War and Peace. It attempts great things in a deliberately and carefully limited space. Nostromo the man is just one of the victims of this terrible process. Attempting to put him at the centre of this story of cynical greed and opportunism is to miss the stark contrast Conrad is suggesting between the idealism and pure intentions of so many of his nobler characters and the brutal ends to which they come.

Alec Guinness and David Lean (1984)

Alec Guinness and David Lean (1984)Did David Lean understand all that? Maybe. Though some of the more inflammatory statements about the glories of the British Raj he made while filming A Passage to India do give one pause. Certainly, as one might expect from the author of Savages, Christopher Hampton got it straight away, and held it in the centre of his vision of the story. Perhaps that's why he was fired.

I do miss Lean's movie. The 1997 TV series did its best to embody Nostromo as a whole, but ended up as a bit of an incoherent mess. Once again, they seem to have thought that because that's what it's called, that's what the novel is about. The careful way in which Conrad establishes the financier Charles Gould at the centre of the revolutionary action of the novel is largely ignored. And it would take a master film-maker to suggest it - perhaps one with a more Brechtian bent: Martin Scorsese, for instance.

Much has been made of the fact that Conrad was a man of action, a professional sea captain, as well as a writer - and it's all true - but more needs to be said about the hardheaded realism with which he confronted the vagaries of history. Despite his love of romance and mystery, he could never ignore the boot in the face, and the pitiless economic forces which guided it.

Alastair Reid, dir.: Nostromo (1997)

Alastair Reid, dir.: Nostromo (1997)•

Alvin Langdon Coburn: Joseph Conrad (1916)

Alvin Langdon Coburn: Joseph Conrad (1916)Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski

['Joseph Conrad']

(1857-1924)

[books owned by me are marked in bold:]

Novels:

Almayer's Folly (1895)Included in: The First and Last of Conrad: Almayer's Folly; An Outcast of the Islands; The Arrow of Gold; & The Rover. 1895, 1896, 1919, & 1923. London: Ernest Benn Limited, 1929. An Outcast of the Islands (1896)Included in: The First and Last of Conrad: Almayer's Folly; An Outcast of the Islands; The Arrow of Gold; & The Rover. 1895, 1896, 1919, & 1923. London: Ernest Benn Limited, 1929. The Nigger of the 'Narcissus' (1897)Included in: The Nigger of the 'Narcissus' / Typhoon; Amy Foster; Falk; Tomorrow. 1897 & 1903. Penguin Modern Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970. Heart of Darkness (1899)Included in: Two Tales of the Congo: Heart of Darkness & An Outpost of Progress. Copper-Engravings by Dolf Rieser. London: The Folio Society. 1952.Heart of Darkness: An Authoritative Text; Backgrounds and Sources; Essays in Criticism. 1899. Ed. Robert Kimbrough. A Norton Critical Edition. New York & London: W. W. Norton & Company, 1963.Heart of Darkness: An Authoritative Text; Backgrounds and Sources; Essays in Criticism. 1899. Ed. Robert Kimbrough. 1963. Second Edition. 1971. Third Edition. A Norton Critical Edition. New York & London: W. W. Norton & Company, 1988. Lord Jim (1900)Lord Jim: A Tale. 1900. Joseph Conrad’s Works: Collected Edition. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1946.Lord Jim: Authoritative Text; Backgrounds; Sources; Criticism. 1900. Ed. Thomas C. Moser. A Norton Critical Edition. 1968. 2nd ed. New York & London: W. W. Norton & Company, 1996. [with Ford Madox Ford] The Inheritors (1901)Included in: [with Ford Madox Ford] The Inheritors: An Extravagant Story / Laughing Anne: A Play / One Day More: A Play. 1901 & 1924. Illustrated by Jutta Ash. Joseph Conrad: Complete Works. Geneva: Heron Books, 1969. [with Ford Madox Ford] Romance (1903)[with Ford Madox Ford] Romance. 1903. Joseph Conrad’s Works: Collected Edition. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1949. Nostromo (1904)Nostromo: A Tale of the Seaboard. 1904. The Works of Joseph Conrad: Uniform Edition. London & Toronto: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd. / Paris: J. M. Dent et Fils, 1923.Nostromo: A Tale of the Seaboard. 1904. Ed. Martin Seymour-Smith. 1983. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1986. The Secret Agent (1907)The Secret Agent: A Simple Tale. 1907. Penguin Modern Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1974. Under Western Eyes (1911)Under Western Eyes. 1911. Penguin Modern Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966. Chance (1913)Chance: A Tale in Two Parts. 1913. Penguin Modern Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1984. Victory (1915)Victory: An Island Tale. 1915. Introduction by V. S. Pritchett. London: The Book Society, 1952. The Shadow Line (1917)The Shadow Line: A Confession. 1917. Ed. Jacques Berthoud. Penguin Modern Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1986. The Arrow of Gold (1919)Included in: The First and Last of Conrad: Almayer's Folly; An Outcast of the Islands; The Arrow of Gold; & The Rover. 1895, 1896, 1919, & 1923. London: Ernest Benn Limited, 1929. The Rescue (1920)The Rescue: A Romance of the Shallows. 1920. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1950. The Rover (1923)Included in: The First and Last of Conrad: Almayer's Folly; An Outcast of the Islands; The Arrow of Gold; & The Rover. 1895, 1896, 1919, & 1923. London: Ernest Benn Limited, 1929. Suspense (1925)Suspense. Introduction by Richard Curle. London & Toronto: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1925.

Short Story Collections:

Tales of Unrest (1898) [TU]Tales of Unrest [The Idiots; The Lagoon; An Outpost of Progress; The Return; Karain: A Memory]. 1898. Penguin Modern Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1977. Youth and Two Other Stories (1902) [Y]Youth; Heart of Darkness; The End of the Tether: Three Stories. 1902. Joseph Conrad’s Works: Collected Edition. 1946. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1961. Typhoon and Other Stories (1903) [T]Included in: The Nigger of the 'Narcissus' / Typhoon; Amy Foster; Falk; Tomorrow. 1897 & 1903. Penguin Modern Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970. A Set of Six (1908) [S6]A Set of Six [Gaspar Ruiz; The Informer; The Brute; An Anarchist; The Duel; Il Conde]. 1908. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1927. 'Twixt Land and Sea (1912) [TLS]’Twixt Land and Sea: Three Tales [A Smile of Fortune; The Secret Sharer; Freya of the Seven Isles]. 1912. Penguin Modern Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978. Within the Tides (1915) [WT]Within the Tides [The Planter of Malata; The Partner; The Inn of the Two Witches; Because of the Dollars]. 1915. Penguin Modern Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978. Tales of Hearsay (1925) [TH]Included in: Tales of Hearsay and Last Essays [The Warrior's Soul; Prince Roman; The Tale; The Black Mate]. 1925 & 1926. Joseph Conrad’s Works: Collected Edition. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1955. The Complete Short Stories (1933)The Complete Short Stories [To-morrow (1902); Amy Foster (1901); Karain: A Memory (1897); The Idiots (1896); An Outpost of Progress (1896); The Return (1897); The Lagoon (1896); Youth: A Narrative (1898); Heart of Darkness (1898-99); The End of the Tether (1902); Gaspar Ruiz (1904-5); The Informer (1906); The Brute (1906); An Anarchist (1905); The Duel (1908); Il Conde (1908); A Smile of Fortune (1910); The Secret Sharer (1909); Freya of the Seven Isles (1910-11); The Planter of Malata (1914); The Partner (1911); The Inn of the Two Witches (1913); Because of the Dollars (1914); The Warrior's Soul (1915-16); Prince Roman (1910); The Tale (1916); The Black Mate (1886)]. London: Hutchinson & Co. (Publishers), Ltd., [1933]. The Complete Short Fiction of Joseph Conrad. Ed. Samuel Hynes. 4 vols (1991-92)The Stories, Volume I [The Idiots (1896); The Lagoon (1896); An Outpost of Progress (1896); Karain: A Memory (1897); The Return (1897); Youth: A Narrative (1898); Amy Foster (1901); To-morrow (1902); Gaspar Ruiz: A Romantic Tale (1904-5)]. New York: The Ecco Press, 1991.The Stories, Volume II [An Anarchist: A Desperate Tale (1905); The Informer: An Ironic Tale (1906); The Brute: An Indignant Tale (1906); The Black Mate (1886); Il Conde: A Pathetic Tale (1908); The Secret Sharer: An Episode from the Coast (1909); Prince Roman (1910); The Partner (1911); The Inn of the Two Witches: A Find (1913); Because of the Dollars (1914); The Warrior's Soul (1915-16); The Tale (1916); Appendix: The Sisters (1895)]. New York: The Ecco Press, 1992.The Tales, Volume III [Heart of Darkness (1898-99); Typhoon (1899-1901]; The End of the Tether (1902)]. New York: The Ecco Press, 1992.The Tales, Volume IV [Falk: A Reminiscence (1901); The Duel (1908); A Smile of Fortune (1910); Freya of the Seven Isles: A Story of Shallow Waters (1910-11); The Planter of Malata (1914)]. New York: The Ecco Press, 1992.

Stories:

The Black Mate (1886) [TH]The Sisters (1895)The Idiots (1896) [TU]The Lagoon (1896) [TU]An Outpost of Progress (1896) [TU]Karain: A Memory (1897) [TU]The Return (1897) [TU]Youth: A Narrative (1898) [Y]Heart of Darkness (1898-99) [Y]Typhoon (1899-1901] [T]Amy Foster (1901) [T]Falk: A Reminiscence (1901) [T]To-morrow (1902) [T]The End of the Tether (1902) [Y]Gaspar Ruiz (1904-5) [S6]An Anarchist (1905) [S6]The Informer (1906) [S6]The Brute (1906) [S6]The Duel (1908) [S6]Il Conde (1908) [S6][with Ford Madox Ford] The Nature of a Crime (1909) [CD]A Smile of Fortune (1910) [TLS]The Secret Sharer (1909) [TLS]Prince Roman (1910) [TH]Freya of the Seven Isles (1910-11) [TLS]The Partner (1911) [WT]The Inn of the Two Witches (1913) [WT]The Planter of Malata (1914) [WT]Because of the Dollars (1914) [WT]The Warrior's Soul (1915-16) [TH]The Tale (1916) [TH]

Non-fiction:

The Mirror of the Sea (1906)Included in: The Mirror of the Sea: Memories and Impressions / A Personal Record: Some Reminiscences. 1906 & 1912. Everyman’s Library, 1189. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1972. A Personal Record (1912)Included in: The Mirror of the Sea: Memories and Impressions / A Personal Record: Some Reminiscences. 1906 & 1912. Everyman’s Library, 1189. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1972. Notes on Life and Letters (1921)Notes on Life and Letters. London & Toronto: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1921. Last Essays (1926)Included in: Tales of Hearsay and Last Essays [The Warrior's Soul; Prince Roman; The Tale; The Black Mate]. 1925 & 1926. Joseph Conrad’s Works: Collected Edition. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1955. The Congo Diary and Other Uncollected Pieces (1978) [CD]Congo Diary and Other Uncollected Pieces. Ed. Zdzislaw Najder. New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1978. Conrad's Congo (2013)Conrad’s Congo. Ed. J. H. Stape. Preface by Adam Hochschild. London: The Folio Society, 2013.

Plays:

One Day More (1917)Laughing Anne (1923)Laughing Anne & One Day More: Two Plays. Introduction by John Galsworthy. London: John Castle, 1924.Included in: [with Ford Madox Ford] The Inheritors: An Extravagant Story / Laughing Anne: A Play / One Day More: A Play. 1901 & 1924. Illustrated by Jutta Ash. Joseph Conrad: Complete Works. Geneva: Heron Books, 1969.

Letters:

Conrad’s Polish Background: Letters to and from Polish Friends. Ed. Zdzislaw Najder. Trans. Halina Carroll. London: Oxford University Press, 1964.Joseph Conrad’s Letters to R. B. Cunninghame Graham. Ed. C. T. Watts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969.

Secondary:

Baines, Jocelyn. Joseph Conrad: A Critical Biography. 1960. Pelican Biographies. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971.Brownlow, Kevin. David Lean: A Biography. Research Associate: Cy Young. 1996. A Wyatt Book. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1997.Conrad, Borys. My Father: Joseph Conrad. London: Calder & Boyars, 1970.Curle, Richard. Joseph Conrad: A Study. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., Ltd., 1914.Eames, Andrew. Crossing the Shadow Line: Travels in South-East Asia. Sceptre. London: Hodder and Stoughton Paperbacks, 1986.Hampton, Christopher. The Secret Agent and Nostromo: Based on the Novels by Joseph Conrad. Faber Filmscripts. London: Faber, 1996.Karl, Frederick R. Joseph Conrad: The Three Lives. A Biography. London: Faber, 1979.Sherry, Norman. Conrad's Eastern World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1966.

Published on March 30, 2022 13:43

March 17, 2022

SF Luminaries: The Singular Genius of Gene Wolfe

Gene Wolfe: The Island of Doctor Death and Other Stories and Other Stories (1980)

Gene Wolfe: The Island of Doctor Death and Other Stories and Other Stories (1980)The Island of Doctor Death and Other Stories and Other Stories. No, it's not a misprint. Recently I bought a rather battered first edition copy of Gene Wolfe's debut collection of short stories and novellas from Hard-to-Find Books in Auckland, one of the few local bookshops which still maintains a healthy stock of old SF paperbacks.

Admittedly it's not really a thing of beauty. That cover image, by Don Maitz, is quite accurate to the story it illustrates, but seems otherwise almost calculated not to appeal. The paper inside is brittle and the print miniscule. But the stories themselves are breathtaking!

One of the incidental characters in "Tracking Story" remarks to its unnamed protagonist:

You know nothing. You are like a child who has wandered by accident into a theater half a minute before the final curtain. You see people moving around, some masked; you hear music, observe actions you do not understand. But you do not know if the play is a tragedy or a comedy, or even know whether those you see are the actors or the audience. [217]That seems as good a way as any of summing up Wolfe's approach to storytelling. We know nothing. Nothing we are told can be trusted. No narrator is reliable, no action not open to doubt. How, then, are his readers to make their way through this baffling labyrinth of signs?

Along with the untrustworthy or just plain ignorant narrator, Wolfe is addicted to the idea of the story within a story. In the Nebula-award nominated "Seven American Nights," for instance, much of the plot hinges on the Muslim hero's haunting of a Washington theatre where J. M. Barrie's supernatural play "Mary Rose" is being performed. The more you know about that play, the more sense Wolfe's own story will make to you.

The extraordinary "Eyeflash Miracles", another Nebula Award nominee for best novella, overlays the experiences of a blind child runaway with, on the one hand, The Wizard of Oz - on the other, the Hindu myth of Krishna and Vishnu.

Gene Wolfe: Soldier of the Mist (1986)

Gene Wolfe: Soldier of the Mist (1986)The 'Soldier of the Mist' trilogy, possibly my favourite among all of his works (which I wrote about in an earlier blogpost here), is told by a brain-damaged soldier incapable of forming new memories, whose attention span lasts roughly one day. His account of the retreat of Xerxes' army from Classical Greece after their defeat at the Battle of Plataea in 479 BCE is therefore compiled from a series of disjointed diary entries, forgotten almost as soon as they're written down.

Another thing his head injury has gifted him with is the ability to see and converse with the gods. Or rather, the capacity to believe that that is what he is doing. It sounds like a pretty strange plot premise. It is an extremely weird idea for a story, but somehow Wolfe succeeds in making it both compelling and poignant.

Gene Wolfe: The Book of the New Sun (1980-83)

Gene Wolfe: The Book of the New Sun (1980-83)The Book of the New Sun is undoubtedly the work he's best known for - particularly the first volume of the tetralogy, Shadow of the Torturer. It is, in many ways, one of the most direct and straightforward of his stories, and yet even it seems, at times, almost calculated to confuse.

Why? Why did Wolfe refuse to tailor his works to the market? Why did he always insist on applying just one more turn to the screw? Not by accident did he issue a number of his limited edition novellas through an outfit called "The Pretentious Press".

One reason may have been, initially, because he had a full-time job as an industrial engineer for most of his working life, from the mid-1950s until 1984, when he retired to become a full-time writer. In other words, he didn't have to make continuous sales to the pulps for a living. He was, instead, free to experiment.

For the most part, though, it must have been just because he had that sort of mind. From the very beginning his work seemed more in tune with contemporary tricksters and game-players such as Barthelme and Borges, Cortázar and Calvino, than Sci-fi gurus such as Asimov and Clarke.

Gene Wolfe: The Wizard Knight (2004)

Gene Wolfe: The Wizard Knight (2004)Even his late sword-and-sorcery epic The Wizard Knight goes through an almost unbelievably convoluted set of plot pathways before reaching its denouement. Often, as you read him, you feel that this time he's gone too far: this time the weirdness has finally flipped over into complete incomprehensibility. But no, every time he pulls it off. You may not end up liking the result, but you can't deny the courage of a writer who literally doesn't care if you get it or not.