Jack Ross's Blog, page 7

June 4, 2023

SF Luminaries: Ray Bradbury

Ray Bradbury (1920-2012)

Ray Bradbury (1920-2012)As various fans have already pointed out, Stephen King's latest novel Fairy Tale (2022) - despite being overtly dedicated to Edgar Rice Burroughs, Robert E. Howard, and H. P. Lovecraft, also contains a number of covert references to another distinguished predecessor in the horror/fantasy genre: Ray Bradbury.

For one thing, it takes place in a small town called Sentry's Rest, Illinois - which seems like a nod to the mythical Green Town, Illinois, setting for Bradbury's classic novel Something Wicked This Way Comes (1962). The alternate universe of Empis which King's protagonist, Charlie Reade [get it? "Read"] explores also contains a magic carousel, one of the central features of the travelling carnival in Bradbury's own book.

Ray Bradbury: Something Wicked This Way Comes (1962)

Ray Bradbury: Something Wicked This Way Comes (1962)Mind you, once you start looking for parallels with other fantasy writers, King's story threatens to fall apart under the sheer weight of allusion. Readers have postulated links with William Goldman's The Princess Bride; Lord Dunsany's realm of Elfland, "beyond the fields we know"; not to mention numerous echoes of King's own Dark Tower saga.

Bradbury is special for him, though. As he himself once put it: "without Ray Bradbury, there is no Stephen King." Or, as he wrote on hearing the news of Bradbury's death in 2012, at the age of 91:

Ray Bradbury wrote three great novels and three hundred great stories. One of the latter was called 'A Sound of Thunder.' The sound I hear today is the thunder of a giant's footsteps fading away. But the novels and stories remain, in all their resonance and strange beauty.So who exactly was this starry-eyed visonary - this laureate of space and small-town life - and why has he left such a strangely equivocal and contradictory reputation behind him?

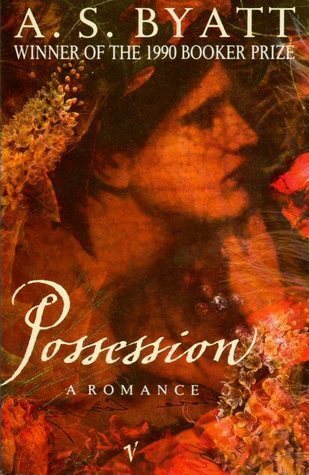

Library of America: The Ray Bradbury Collection (2022)

Library of America: The Ray Bradbury Collection (2022)You know that you've really arrived when they not only reprint your collected works in the canonical Library of America series, but even provide a specially designed slipcase to put them in!

Novels & Story Cycles. Ed. Jonathan R. Eller. The Library of America, 347. [‘The Martian Chronicles’, 1950; ‘Fahrenheit 451’, 1953; ‘Dandelion Wine’, 1957; ‘Something Wicked This Way Comes’, 1962]. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 2021.

The Illustrated Man, The October Country & Other Stories. Ed. Jonathan R. Eller. The Library of America, 360. 1951, 1955. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 2022.

Ray Bradbury: The Martian Chronicles (1950)

Ray Bradbury: The Martian Chronicles (1950)You'll notice, though, that most of the work included in this set is comparatively early - dating roughly from the 1940s to the early 1960s. And even Stephen King claims only three great Bradbury novels among the dozen or so he actually published.

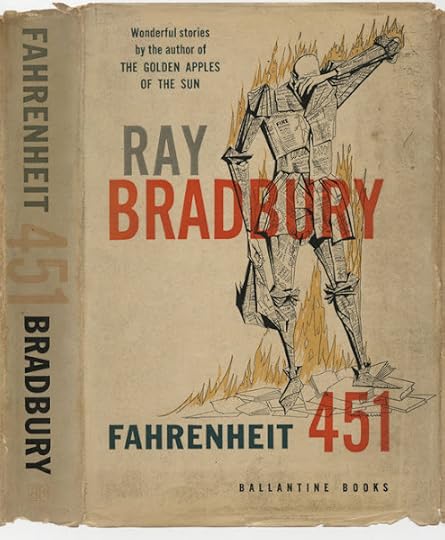

Ray Bradbury: Fahrenheit 451 (1953)

Ray Bradbury: Fahrenheit 451 (1953)There's little doubt that two of the three must be Fahrenheit 451 (1953) and Something Wicked This Way Comes (1962). The third is more debatable: The Martian Chronicles (1950) would be most people's first choice for the honour, but it is technically a 'story-cycle' rather than a novel. That would leave us with Dandelion Wine (1957) - to me almost unbearably saccharine in its evocation of untroubled boyhood, but certainly a book which has its admirers.

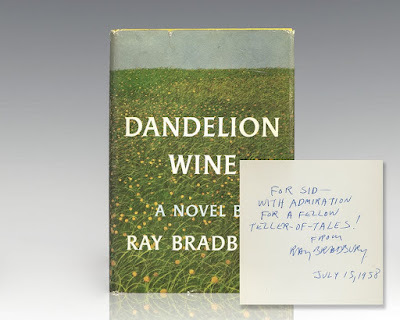

Ray Bradbury: Dandelion Wine (1957)

Ray Bradbury: Dandelion Wine (1957)Are there any other serious candidates? Not really. Ray Bradbury was a writer who peaked comparatively early, with a dazzling series of science fiction and horror short stories published throughout the 1940s and 50s, some of the strongest of which were reprinted in the early collection Dark Carnival, by H. P. Lovecraft's disciple and friend, August Derleth, at his legendary imprint Arkham House.

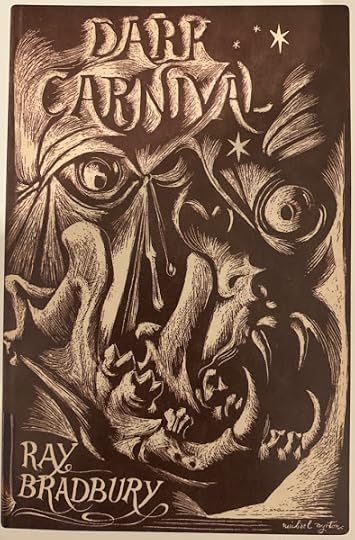

Ray Bradbury: Dark Carnival (1947)

Ray Bradbury: Dark Carnival (1947)Only 15 of the 27 stories in this unrelentingly dark and pitiless collection were reprinted, several in revised versions, in The October Country (1955). As Wikipedia tells it:

For many years, Bradbury did not permit Dark Carnival to be reprinted ... However, a limited edition ... with five extra stories and a new introduction by Bradbury, was printed by Gauntlet Press in 2001.A new paperback edition of this seminal collection is promised for early 2024.

The fact is that it was horror stories such as "The Veldt" (in The Illustrated Man), "The Next in Line" (in Dark Carnival & The October Country), and "Mars is Heaven!" (in The Martian Chronicles) which were responsible for much of Bradbury's early vogue. Cannibalism, live burial, and homicidal children are just a few of his early themes.

So before you go writing him off as an old sentimentalist dreaming of some kind of Tom Sawyer-like childhood paradise in rural Illinois, never forget the dark, Lovecraftian roots behind much of his best work.

The Illustrated Man (2012)

The Illustrated Man (2012)A couple of his early Martian stories interested me particularly as I reread all the early collections reprinted in the Library of America boxset.

They're entitled (respectively) "Way in the Middle of the Air" [included in early editons of The Martian Chronicles, 1950] - which concerns a mass exodus of African American people to Mars; and "The Other Foot" [included in The Illustrated Man, 1951] - which tells us what happens when the news of the return to Mars of the last few white people left after their latest suicidal war reaches the now exclusively black population of the red planet.

By today's standards both stories sound rather naive and patronising. There's a lot of Huck Finn-style dialect, use of the "n"-word, and other now unacceptable linguistic usages. Both stories are also intensely well-meaning - it's worth noticing that they long predate such civil rights landmarks as the Montgomery Bus Boycott, let alone the compulsory integration of US schools.

And yet, both now read like museum exhibits: Liberal Northern White Attitudes (c.1950). By contrast, his more complex and haunting stories of the time: "Dark They Were, and Golden-Eyed" (1949), for instance - about the gradual possession of an all-American family by the haunting (and haunted?) landscapes and mores of Mars - have a mysterious resonance as powerful now as it was then.

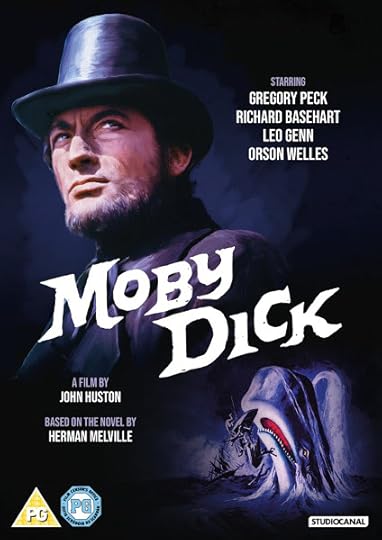

John Huston, dir. Moby Dick (1956)

John Huston, dir. Moby Dick (1956)Perhaps the true turning point for Bradbury was the year he spent working on John Huston's adaptation of Moby Dick. It's not a terrible screenplay - there's a bit too much poetic language in the voice-overs, maybe, but the two of them did a competent enough job at transferring an almost unfilmable novel to the screen.

But Huston's habit of belitting and insulting his collaborators - allegedly (he claimed) to get the best out of them, but actually (it would appear) to indulge his own petty sadism - had a particularly bad effect on the ebullient Bradbury. He wrote a fictionalised version of their encounter in the novel Green Shadows, White Whale , which made it clear that he'd been brooding on the matter for quite some time.

John Huston, dir. Green Shadows, White Whale (1992)

John Huston, dir. Green Shadows, White Whale (1992)It's not that there aren't gems among the later stories - "The Parrot Who Met Papa" (1972), about the search for a legendary parrot alleged to have memorised Hemingway's last novel as a result of his endless rambling monologues in its presence, for instance - but they're pretty few and far between.

Some terrible lapse in self-confidence - or, perhaps, reluctance to indulge the dark side of his nature any further than he'd already done (one of the most prominent themes in Something Wicked This Way Comes) - seems to have kept him largely on the sunny side of the street thereafter. There's a relentless verbosity in his work from the 1970s onwards - occasionally, mercifully, spiked by humour, but mostly a turbid stream of two-bit words and phrases.

He leaves behind, then, a divided legacy: the dark mysteries of his early stories and novels, and the wordy bathos of his later work. As the Library of America has already signalled, there's little doubt which will prevail in the eyes of posterity.

It does leave you wondering, though, just what did Huston (and, for that matter, Herman Melville) do to him in that windy old castle in Ireland? The novel he wrote about it - after, he claimed, having read Katharine Hepburn's account of her own mistreatment at Huston's hands during the making of "The African Queen" (1951): How I Went to Africa With Bogart, Bacall and Huston and Almost Lost My Mind (1987) - is just that: a novel. What really happened to him there we'll never know.

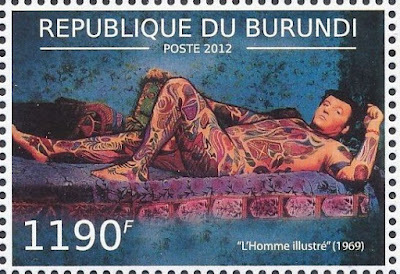

Ray Bradbury Postage Stamp (2012)

Ray Bradbury Postage Stamp (2012)•

Charley Gallay: Ray Bradbury (2007)

Charley Gallay: Ray Bradbury (2007)Ray Douglas Bradbury

(1920-2012)

Books I own are marked in bold:

Novels:

The Martian Chronicles [aka The Silver Locusts] (1950)The Silver Locusts. 1950. London: Corgi Books, 1969.Fahrenheit 451 (1953)Fahrenheit 451. 1953. London: Corgi Books, 1963.Dandelion Wine (1957)Dandelion Wine. 1957. London: Corgi Books, 1972.Something Wicked This Way Comes (1962)Something Wicked This Way Comes. 1962. London: Corgi Books, 1969.The Halloween Tree (1972)The Halloween Tree. 1972. Illustrated by Joseph Mugnaini. London: Hart-Davis, MacGibbon, 1973.The Novels of Ray Bradbury (1984)The Novels of Ray Bradbury: Fahrenheit 451, Dandelion Wine, Something Wicked This Way Comes. 1953, 1957, 1962. London: Book Club Associates, by arrangement with Granada Publishing Limited, 1984.Death is a Lonely Business (1985)A Graveyard for Lunatics (1990)Green Shadows, White Whale (1992)From the Dust Returned (2001)Let's All Kill Constance (2002)Farewell Summer (2006)Novels & Story Cycles. Library of America (2021)Novels & Story Cycles. Ed. Jonathan R. Eller. The Library of America, 347. [‘The Martian Chronicles’, 1950; ‘Fahrenheit 451’, 1953; ‘Dandelion Wine’, 1957; ‘Something Wicked This Way Comes’, 1962]. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 2021.

Collections:

Dark Carnival (1947)The HomecomingSkeletonThe JarThe LakeThe MaidenThe TombstoneThe Smiling PeopleThe EmissaryThe TravelerThe Small AssassinThe CrowdReunionThe HandlerThe CoffinInterimJack-in-the-BoxThe ScytheLet's Play 'Poison'Uncle EinarThe WindThe NightThere Was An Old WomanThe Dead ManThe Man UpstairsThe Night SetsCisternThe Next In Line The Illustrated Man (1951)The VeldtKaleidoscopeThe Other FootThe HighwayThe ManThe Long RainThe Rocket ManThe Fire BalloonsThe Last Night of the WorldThe ExilesNo Particular Night or MorningThe Fox and the ForestThe VisitorThe Concrete MixerMarionettes, Inc.The CityZero HourThe Rocket The Illustrated Man. 1951. Corgi SF Collector’s Library. London: Corgi Books, 1972.The Golden Apples of the Sun (1953)The Golden Apples of the Sun. 1953. Corgi SF Collector’s Library. London: Corgi Books, 1973.The October Country (1955)The DwarfThe Next in LineThe Watchful Poker Chip of H. MatisseSkeletonThe JarThe LakeThe EmissaryTouched With FireThe Small AssassinThe CrowdJack-in-the-BoxThe ScytheUncle EinarThe WindThe Man UpstairsThere Was an Old WomanThe CisternHomecomingThe Wonderful Death of Dudley Stone The October Country. 1955. London: New English Library, 1973. A Medicine for Melancholy (1959)The Day It Rained Forever (1959)The Day It Rained Forever. 1959. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969.The Small Assassin (1962)The Small Assassin. 1962. London: New English Library, 1970.R is for Rocket (1962)R is for Rocket. 1962. London: Pan Books, 1972.The Machineries of Joy (1964)The Machineries of Joy. 1964. London: Panther Books, 1977.The Autumn People (1965)The Vintage Bradbury (1965)Tomorrow Midnight (1966)S is for Space (1966)S is for Space. 1966. New York: Bantam Books, 1978.Twice 22 (1966)I Sing The Body Electric (1969)I Sing The Body Electric! 1969. London: Corgi Books, 1972.Ray Bradbury (1975)Long After Midnight (1976)Long After Midnight. 1976. London: Panther Books, 1978.The Mummies of Guanajuato (1978)The Fog Horn & Other Stories (1979)One Timeless Spring (1980)The Last Circus and the Electrocution (1980)The Stories of Ray Bradbury (1980)The Night (1946)Homecoming (1946)Uncle Einar (1947)The Traveler (1946)The Lake (1944)The Coffin (1947)The Crowd (1943)The Scythe (1943)There Was an Old Woman (1944)There Will Come Soft Rains (1950)Mars Is Heaven! (1948)The Silent Towns (1949)The Earth Men (1948)The Off Season (1948)The Million-Year Picnic (1946)The Fox and the Forest (1950)Kaleidoscope (1949)The Rocket Man (1951)Marionettes, Inc. (1949)No Particular Night or Morning (1951)The City (1950)The Fire Balloons (1951)The Last Night of the World (1951)The Veldt (1950)The Long Rain (1950)The Great Fire (1949)The Wilderness (1952)A Sound of Thunder (1952)The Murderer (1953)The April Witch (1952)Invisible Boy (1945)The Golden Kite, The Silver Wind (1953)The Fog Horn (1951)The Big Black and White Game (1945)Embroidery (1951)The Golden Apples of the Sun (1953)Powerhouse (1948)Hail and Farewell (1948)The Great Wide World over There (1952)The Playground (1953)Skeleton (1943)The Man Upstairs (1947)Touched by Fire (1954)The Emissary (1947)The Jar (1944)The Small Assassin (1946)The Next in Line (1947)Jack-in-the-Box (1947)The Leave-Taking (1957)Exorcism (1957)The Happiness Machine (1957)Calling Mexico (1950)The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit (1958)Dark They Were, and Golden-Eyed (1949)The Strawberry Window (1954)A Scent of Sarsaparilla (1953)The Picasso Summer (1957)The Day It Rained Forever (1957)A Medicine for Melancholy (1959)The Shoreline at Sunset (1959)Fever Dream (1959)The Town Where No One Got Off (1958)All Summer in a Day (1954)Frost and Fire (1946)The Anthem Sprinters (1963)And So Died Riabouchinska (1953)Boys! Raise Giant Mushrooms in Your Cellar! (1962)The Vacation (1963)The Illustrated Woman (1961)Some Live Like Lazarus (1960)The Best of All Possible Worlds (1960)The One Who Waits (1949)Tyrannosaurus Rex (1962)The Screaming Woman (1951)The Terrible Conflagration Up at the Place (1969)Night Call, Collect (1949)The Tombling Day (1952)The Haunting of the New (1969)Tomorrow's Child (1948)I Sing the Body Electric! (1969)The Women (1948)The Inspired Chicken Motel (1969)Yes, We'll Gather at the River (1969)Have I Got a Chocolate Bar for You! (1976)A Story of Love (1951)The Parrot Who Met Papa (1972)The October Game (1948)Punishment Without Crime (1950)A Piece of Wood (1952)The Blue Bottle (1950)Long After Midnight (1962)The Utterly Perfect Murder (1971)The Better Part of Wisdom (1976)Interval in Sunlight (1954)The Black Ferris (1948)Farewell Summer (1980)McGillahee's Brat (1970)The Aqueduct (1979)Gotcha! (1978)The End of the Beginning (1956) The Stories of Ray Bradbury. London: Granada, 1981. The Fog Horn and Other Stories (1981)Dinosaur Tales (1983)A Memory of Murder (1984)The Wonderful Death of Dudley Stone (1985)The Toynbee Convector (1988)Classic Stories 1 (1990)Classic Stories 2 (1990)The Parrot Who Met Papa (1991)Selected from Dark They Were, and Golden-Eyed (1991)Quicker Than The Eye (1996)Driving Blind (1997)Ray Bradbury Collected Short Stories (2001)The Playground (2001)Dark Carnival: Limited Edition with Supplemental Materials (2001)One More for the Road (2002)Bradbury Stories: 100 of His Most Celebrated Tales (2003)The Whole Town's SleepingThe RocketSeason of DisbeliefAnd the Rock Cried OutThe Drummer Boy of ShilohThe Beggar on O'Connell BridgeThe Flying MachineHeavy-SetThe First Night of LentLafayette, FarewellRemember Sascha?JuniorThat Woman on the LawnFebruary 1999: YllaBansheeOne for His Lordship, and One for the Road!The Laurel and Hardy Love AffairUnterderseaboat DoktorAnother Fine MessThe DwarfA Wild Night in GalwayThe WindNo News, or What Killed the Dog?A Little JourneyAny Friend of Nicholas Nickleby's Is a Friend of MineThe Garbage CollectorThe VisitorThe ManHenry the NinthThe MessiahBang! You're Dead!Darling AdolfThe Beautiful ShaveColonel Stonesteel's Genuine Home-made Truly Egyptian MummyI See You NeverThe ExilesAt Midnight, in the Month of JuneThe Witch DoorThe Watchers2004-05: The Naming of NamesHopscotchThe Illustrated ManThe Dead ManJune 2001: And the Moon Be Still as BrightThe Burning ManG.B.S.-Mark VA Blade of GrassThe Sound of Summer RunningAnd the Sailor, Home from the SeaThe Lonely OnesThe FinneganOn the Orient, NorthThe Smiling PeopleThe Fruit at the Bottom of the BowlBugDownwind from GettysburgTime in Thy FlightChangelingThe DragonLet's Play 'Poison'The Cold Wind and the WarmThe MeadowThe Kilimanjaro DeviceThe Man in the Rorschach ShirtBless Me, Father, for I Have SinnedThe PedestrianTrapdoorThe SwanThe Sea ShellOnce More, LegatoJune 2003: Way in the Middle of the AirThe Wonderful Death of Dudley StoneBy the Numbers!April 2005: Usher IIThe Square PegsThe TrolleyThe SmileThe Miracles of JamieA Far-away GuitarThe CisternThe Machineries of JoyBright PhoenixThe WishThe Lifework of Juan DíazTime Intervening/InterimAlmost the End of the WorldThe Great Collision of Monday LastThe PoemsApril 2026: The Long YearsIcarus Montgolfier WrightDeath and the MaidenZero HourThe Toynbee ConvectorForever and the EarthThe HandlerGetting Through Sunday SomehowThe PumpernickelLast RitesThe Watchful Poker Chip of H. MatisseAll on a Summer's day Is That You, Herb? (2003)The Cat's Pajamas: Stories (2004)A Sound of Thunder and Other Stories (2005)The Dragon Who Ate His Tail (2007)Now and Forever: Somewhere a Band Is Playing & Leviathan '99 (2007)Somewhere a Band is Playing: Early Drafts and Final Novella (2007)Summer Morning, Summer Night (2007)Ray Bradbury Stories Volume 2 (2009)We'll Always Have Paris: Stories (2009)A Pleasure To Burn (2010)The Lost Bradbury: Forgotten Tales of Ray Bradbury (2010)The Collected Stories of Ray Bradbury: A Critical Edition – Volume 1, 1938–1943 (2011)The Collected Stories of Ray Bradbury: A Critical Edition – Volume 2, 1943–1944 (2014)Killer, Come Back to Me: The Crime Stories of Ray Bradbury (2020)The Illustrated Man, The October Country & Other Stories. Library of America (2022)The Illustrated Man, The October Country & Other Stories. Ed. Jonathan R. Eller. The Library of America, 360. 1951, 1955. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 2022.

Edited:

Timeless Stories for Today and Tomorrow (1952)The Circus of Dr. Lao and Other Improbable Stories (1956)

Children's Books:

Switch on the Night (1955)The Other Foot (1982)The Veldt (1982)The April Witch (1987)The Fog Horn (1987)Fever Dream (1987)The Smile (1991)The Toynbee Convector (1992)With Cat for Comforter (1997)Dogs Think That Every Day Is Christmas (1997)Ahmed and the Oblivion Machines: A Fable (1998)The Homecoming (2006)

Non-fiction:

No Man Is an Island (1952)The Essence of Creative Writing: Letters to a Young Aspiring Author (1962)Creative Man Among His Servant Machines (1967)Mars and the Mind of Man (1971)Zen in the Art of Writing (1973)Zen in the Art of Writing. 1973. In The Capra Chapbook Anthology. Ed. Noel Young. Santa Barbara, CA: Capra Press, 1979.The God in Science Fiction (1978)About Norman Corwin (1979)There is Life on Mars (1981)The Art of Playboy (1985)Zen in the Art of Writing: Essays on Creativity (1990)Yestermorrow: Obvious Answers to Impossible Futures (1991)Conversations with Ray Bradbury. Ed. Steven L. Aggelis) (2004)Bradbury Speaks: Too Soon from the Cave, Too Far from the Stars (2005)Match to Flame: The Fictional Paths to Fahrenheit 451 (2007)

Poetry:

Where Robot Mice & Robot Men Run Round in Robot Towns (1977)To Sing Strange Songs (1979)Beyond 1984: Remembrance of Things Future (1979)The Ghosts of Forever (1980)The Complete Poems of Ray Bradbury (1982)The Love Affair (1982)I Live By the Invisible: New & Selected Poems (2002)

Screenplays:

The Best of The Ray Bradbury Chronicles (2003)It Came from Outer Space: Screenplay (2003)The Halloween Tree: Screenplay (2005)

Miscellaneous:

Long After Ecclesiastes: New Biblical Texts (1985)Christus Apollo: Cantata Celebrating the Eighth Day of Creation and the Promise of the Ninth (1998)Witness and Celebrate (2000)A Chapbook for Burnt-Out Priests, Rabbis and Ministers (2001)The Best of Ray Bradbury: The Graphic Novel (2003)Futuria Fantasia: SF Fanzine (2007)

Secondary:

Weller, Sam. The Bradbury Chronicles. Harper Perennial. 2005. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2006.Eller, Jonathan R. Becoming Ray Bradbury. Vol. 1 of 3. Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2011.Eller, Jonathan R. Ray Bradbury Unbound. Vol. 2 of 3. Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2014.Eller, Jonathan R. Bradbury Beyond Apollo. Vol. 3 of 3. Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2020.

•

Jonathan Eller: The Bradbury Trilogy (2011-2020)

Jonathan Eller: The Bradbury Trilogy (2011-2020) Sam Weller: The Bradbury Chronicles (2005)

Sam Weller: The Bradbury Chronicles (2005)

Published on June 04, 2023 14:48

May 24, 2023

The Life of the Mind

The Coen Brothers: Barton Fink (1991)

The Coen Brothers: Barton Fink (1991)All Balled Up at Head Office

Certainly the , Joel and Ethan, do not present a particularly attractive picture of the writing life in their satirical masterpiece . "You never listen!" John Goodman (aka Karl "Mad Dog" Mundt) thunders at the hapless Barton as he charges down the burning corridor.

I published a post called "Two Views of the Writer" some years ago, but now I'd like to update the examples I gave there with my own favourite description of what Barton Fink refers to as "the life of the mind". It comes from H. G. Wells' 1896 short story "The Lost Inheritance":

The Daily Mirror: H. G. Wells (1866-1946)

The Daily Mirror: H. G. Wells (1866-1946)“My uncle — my maternal uncle ... had — what shall I call it — ? A weakness for writing edifying literature. Weakness is hardly the word — downright mania is nearer the mark. He’d been librarian in a Polytechnic, and as soon as the money came to him he began to indulge his ambition. It’s a simply extraordinary and incomprehensible thing to me. Here was a man of thirty-seven suddenly dropped into a perfect pile of gold, and he didn’t go — not a day’s bust on it. One would think a chap would go and get himself dressed a bit decent — say a couple of dozen pair of trousers at a West End tailor’s; but he never did. You’d hardly believe it, but when he died he hadn’t even a gold watch. It seems wrong for people like that to have money. All he did was just to take a house, and order in pretty nearly five tons of books and ink and paper, and set to writing edifying literature as hard as ever he could write. ...

“He was a curious little chap, was my uncle, as I remember him. ... Hair just like these Japanese dolls they sell, black and straight and stiff all round the brim and none in the middle, and below, a whitish kind of face and rather large dark grey eyes moving about behind his spectacles. ... He looked a rummy little beggar, I can tell you. Indoors it was, as a rule, a dirty red flannel dressing-gown and a black skull-cap he had. That black skull-cap made him look like the portraits of all kinds of celebrated people. He was always moving about from house to house, was my uncle, with his chair which had belonged to Savage Landor, and his two writing-tables, one of Carlyle’s and the other of Shelley’s, so the dealer told him, and the completest portable reference library in England, he said he had — and he lugged the whole caravan, now to a house at Down, near Darwin’s old place, then to Reigate, near Meredith, then off to Haslemere, then back to Chelsea for a bit, and then up to Hampstead. He knew there was something wrong with his stuff, but he never knew there was anything wrong with his brains. It was always the air, or the water, or the altitude, or some tommy-rot like that. ‘So much depends on environment,’ he used to say, and stare at you hard, as if he half suspected you were hiding a grin at him somewhere under your face. ‘So much depends on environment to a sensitive mind like mine.’”

“What was his name? You wouldn’t know it if I told you. He wrote nothing that anyone has ever read — nothing. No one could read it. He wanted to be a great teacher, he said, and he didn’t know what he wanted to teach any more than a child. So he just blethered at large about Truth and Righteousness, and the Spirit of History, and all that. Book after book he wrote and published at his own expense. He wasn’t quite right in his head, you know really; and to hear him go on at the critics — not because they slated him, mind you — he liked that — but because they didn’t take any notice of him at all. ‘What do the nations want?’ he would ask, holding out his brown old claw. ‘Why, teaching — guidance! They are scattered upon the hills like sheep without a shepherd. There is War and Rumours of War, the unlaid Spirit of Discord abroad in the land, Nihilism, Vivisection, Vaccination, Drunkenness, Penury, Want, Socialistic Error, Selfish Capital! Do you see the clouds, Ted —?’ My name, you know — ‘Do you see the clouds lowering over the land? and behind it all — the Mongol waits!’ He was always very great on Mongols, and the Spectre of Socialism, and suchlike things.”

“Then out would come his finger at me, and with his eyes all afire and his skull-cap askew, he would whisper: ‘And here am I. What did I want? Nations to teach. Nations! I say it with all modesty, Ted, I could. I would guide them; nay! But I will guide them to a safe haven, to the land of Righteousness, flowing with milk and honey.’”

“That’s how he used to go on. Ramble, rave about the nations, and righteousness, and that kind of thing. Kind of mincemeat of Bible and blethers. From fourteen up to three-and-twenty, when I might have been improving my mind, my mother used to wash me and brush my hair (at least in the earlier years of it), with a nice parting down the middle, and take me, once or twice a week, to hear this old lunatic jabber about things he had read of in the morning papers, trying to do it as much like Carlyle as he could, and I used to sit according to instructions, and look intelligent and nice, and pretend to be taking it all in. ...

“’A moment!’ he would say. ‘A moment!’ over his shoulder. ‘The mot juste, you know, Ted, le mot juste. Righteous thought righteously expressed — Aah —! Concatenation. And now, Ted,’ he’d say, spinning round in his study chair, ‘how’s Young England?’ That was his silly name for me.”

“Well, that was my uncle, and that was how he talked — to me, at any rate. With others about he seemed a bit shy. And he not only talked to me, but he gave me his books, books of six hundred pages or so, with cock-eyed headings, ‘The Shrieking Sisterhood,’ ‘The Behemoth of Bigotry,’ ‘Crucibles and Cullenders,’ and so on. All very strong, and none of them original. The very last time, but one, that I saw him, he gave me a book. He was feeling ill even then, and his hand shook and he was despondent. I noticed it because I was naturally on the look-out for those little symptoms. ‘My last book, Ted,’ he said. ‘My last book, my boy; my last word to the deaf and hardened nations;’ and I’m hanged if a tear didn’t go rolling down his yellow old cheek. He was regular crying because it was so nearly over, and he hadn’t only written about fifty-three books of rubbish. ‘I’ve sometimes thought, Ted —’ he said, and stopped.”

“’Perhaps I’ve been a bit hasty and angry with this stiff-necked generation. A little more sweetness, perhaps, and a little less blinding light. I’ve sometimes thought — I might have swayed them. But I’ve done my best, Ted.’”

“And then, with a burst, for the first and last time in his life he owned himself a failure. It showed he was really ill. He seemed to think for a minute, and then he spoke quietly and low, as sane and sober as I am now. ‘I’ve been a fool, Ted,’ he said. ‘I’ve been flapping nonsense all my life. Only He who readeth the heart knows whether this is anything more than vanity. Ted, I don’t. But He knows, He knows, and if I have done foolishly and vainly, in my heart — in my heart —’”

“Just like that he spoke, repeating himself, and he stopped quite short and handed the book to me, trembling. Then the old shine came back into his eye. I remember it all fairly well, because I repeated it and acted it to my old mother when I got home, to cheer her up a bit. ‘Take this book and read it,’ he said. ‘It’s my last word, my very last word. I’ve left all my property to you, Ted, and may you use it better than I have done.’ And then he fell a-coughing.”

“I remember that quite well even now, and how I went home cock-a-hoop, and how he was in bed the next time I called. ... He was sinking fast. But even then his vanity clung to him.

“’Have you read it?’ he whispered.”

“’Sat up all night reading it,’ I said in his ear to cheer him. ‘It’s the last,’ said I, and then, with a memory of some poetry or other in my head, ‘but it’s the bravest and best.’”

“He smiled a little and tried to squeeze my hand as a woman might do, and left off squeezing in the middle, and lay still. ‘The bravest and the best,’ said I again, seeing it pleased him. But he didn’t answer. ... I looked at his face, and his eyes were closed, and it was just as if somebody had punched in his nose on either side. But he was still smiling. It’s queer to think of — he lay dead, lay dead there, an utter failure, with the smile of success on his face.

Helen Allingham: Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881)

Helen Allingham: Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881)The will, alas, is nowhere to be found, so the whole estate goes to another, far less attentive nephew instead. The narrator falls "on hard times, because as you see, the only trade I knew was legacy-cadging."

"I was hunting round my room to find something to raise a bit on for immediate necessities, and the sight of all those presentation volumes — no one will buy them, not to wrap butter in, even — well, they annoyed me. I promised him not to part with them, and I never kept a promise easier. I let out at them with my boot, and sent them shooting across the room. One lifted at the kick, and spun through the air. And out of it flapped — You guess?

“It was the will. He’d given it to me himself in that very last volume of all.”

... “It just shows you the vanity of authors,” he said, looking up at me. “It wasn’t no trick of his. He’d meant perfectly fair. He’d really thought I was really going home to read that blessed book of his through. But it shows you, don’t it —?” his eye went down to the tankard again —, “It shows you too, how we poor human beings fail to understand one another.”

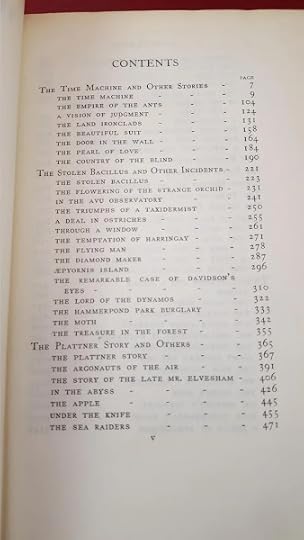

H. G. Wells: The Plattner Story and Others (1897)

H. G. Wells: The Plattner Story and Others (1897)It's a cruel story, in many ways. The absurdity of the uncle's ambitions, all his attempts to sound like Carlyle or some other great sage, are skewered with immaculate precision by the ruthless young Wells, whose books, in 1896, were already starting to sell - in increasingly large numbers.

But the last laugh is, of course, on the nephew, whose cadging flattery inspires the old man to slip him what he wants most, the will, in this furtive way. And yet, one can hear a certain reluctant affection breaking through all the cynical chatter - despite himself, it's hard to believe that he didn't feel something for his uncle. After all, he didn't have to go quite to those lengths to placate him: "It’s the last, but it’s the bravest and best."

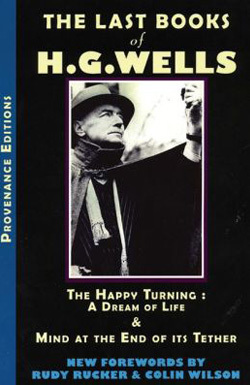

I've wondered sometime if this early story came into Wells's mind at all as he was composing his own last book - not so much of Bible, but of Science and blethers - Mind at the End of Its Tether, in 1945. He'd long since lost his audience, and was largely talking to himself by this stage. But there's a horrible woolly vagueness about his work at the end which is sadly reminiscent of the author of The Shrieking Sisterhood, The Behemoth of Bigotry, or Crucibles and Cullenders ... Beware of what you mock, because that may turn out to be you in the end.

H. G. Wells: The Last Books of H.G. Wells: The Happy Turning & Mind at the End of its Tether (1945 / 2006)

H. G. Wells: The Last Books of H.G. Wells: The Happy Turning & Mind at the End of its Tether (1945 / 2006)I was reminded irresistibly of this story when I came across an article on "The dream job most New Zealanders long for, and how to get it", by Annemarie Quill, on the Stuff website in January this year:

One career tops the list in Aotearoa as the most desirable job in the country, according to new Google search data, yet it is not always the easiest or best paying.But what kind of a writer?

The dream job that most New Zealanders long to do for a living has been revealed by global analysis of 12-months of Google search data around job types, including the question “How to be a...”

The answer for Kiwis was, apparently ... a writer.

NZ Herald: Keri Hulme & Eleanor Catton (28/1/15)

NZ Herald: Keri Hulme & Eleanor Catton (28/1/15)Kiwis aspiring to win the Booker prize like Eleanor Catton or Keri Hulme, or think they can soar to the top of bestseller lists by knocking out the next Harry Potter or Fifty Shades, could find that the reality of being a writer might not live up to the dream.Bay of Plenty book editor Chad Dick agrees that "It’s a career that people should follow for love, not money ... If the thought of having your book in your hand is enough, then you are half way there.”

“There are big rewards if you reach the very top and yet, it also promises to be a gruelling career for many filled with rejection, self-doubt and financial concerns,” said a spokesperson for Remitly, the financial services group which collated the data.

New Zealand sports journalist turned novelist Peter White said he wasn’t too surprised that so many New Zealanders dreamed of writing.It's not that there isn't a lot of very sensible advice in this article: there is. Those of us in the trade of teaching Creative Writing certainly have to get used to introducing - as diplomatically as possible - a touch of realism into the unrealistically lofty hopes and dreams of aspiring novelists and poets.

“I would have thought it would be All Black, but it makes sense. Everyone has a story inside them, and writing is the perfect way to express it.”

But the question still needs a good deal of unpacking. Is it the idea of being a writer that attracts people, or the actual brute work of writing? The rewards, when they come, are seldom commensurate to the superhuman effort of creating something genuinely worth reading - and the prodigies who seemingly effortlessly spin stories out of thin air are rarer than one might think.

In the end "the thought of having his book in his hand" was apparently not enough for Wells's uncle - even that tottering stack of 53-odd self-published tomes - as he despaired on his deathbed. What he craved was some whisper of recognition. Did he believe those last lying words of his nephew? Perhaps - perhaps not.

But he was still smiling. It’s queer to think of — he lay dead, lay dead there, an utter failure, with the smile of success on his face.

Jack Ross: Biblioblitz (2006)

Jack Ross: Biblioblitz (2006)Perhaps that's the final irony of Wells's story. It's presumably meant to be a satire on the vanity of authors, but no writer can read it without feeling a reluctant affinity with that poor absurd old man with his vanload of paper and Walter Savage Landor's chair.

"Fake it till you make it." I remember hearing Martha Stewart angrily denouncing this doctrine on her own abortive version of The Apprentice Reality TV show: "I never faked anything. I went to jail, for God's sake!"

I'm not quite sure how being convicted of insider trading equates with not being a fake, but then "that's just facts", as another popular adage has it. All writers are fakes. Even the ones who win huge prizes and the adulation of millions have, somewhere inside them, some last remaining vestiges of impostor syndrome.

Which is not to say that there's no difference between H. G. Wells, or Thomas Carlyle, and the poor deluded uncle in the story - but it's more one of degree and scale than of species. If I had to pick a patron saint of writers, it would definitely be the uncle.

H. G. Wells: The Short Stories (1927)

H. G. Wells: The Short Stories (1927)

Published on May 24, 2023 13:38

May 13, 2023

Amis & Son

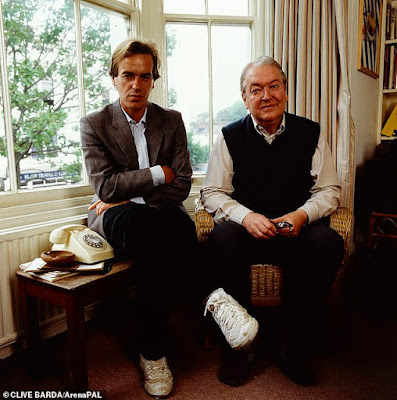

Neil Powell: (2008)

Neil Powell: (2008)Amis fils & Amis père

The other day I was in a bookshop where they were having a "five for five dollars" sale. Even at that price, I found few items to tempt me. An old copy of Spycatcher - yes, I missed reading that at the time, back in the paranoid '80s, but my friend John Fenton assures me it's a valuable piece of social history - that went in the bag. What else? An anthology of writings about the Battle of Britain, edited by some flying ace or other; a companion volume about pioneer aviators; Andrew Motion's Selected Poems; and - Amis & Son: Two Literary Generations ...

You'd think the latter would have been a shoo-in, given my longstanding obsession with the life and works of Kingsley Amis and (to a somewhat lesser extent) his son and literary rival Martin. Not so. I already own no fewer than three full-length biographies of "Kingers", as his friends used to call him, and - to be honest - I felt a bit reluctant to add to their number.

Still: five for five dollars - not to mention the fact that there isn't, so far as I'm aware, much biographical writing as yet about Martin - or 'Amis fils', as he's sometimes called. So I duly bought it and stowed it away on the shelf devoted to just such Amisiana. Until, the other day, feeling in dire need of a bit of a laugh - and I do find both Amises irresistibly amusing at times - I picked it up and started to read it.

London Remembers: Sir Kingsley Amis

London Remembers: Sir Kingsley AmisIt begins, sensibly enough, with a visit to "Kingsley Amis's earliest childhood home - 16 Buckingham Gardens, Norbury, SW16." The author is quick to refute "the green plaque stating that Sir Kingsley Amis was born here" placed there by the local council. Apparently he wasn't. As for the house itself, and its immediate ambience:

Even if Buckingham Gardens hasn't gone down in the world much since the Amises lived here, it hasn't come up; only one of the houses shows the slightest hint of ownerly gentrification, and it looks out of place.So far so good. Class insecurity is a major theme of Neil Powell's book as a whole, so this seems a good place to start. But then:

The air carries a stong and unmistakable whiff of curry, which Kingsley mightn't in one sense have minded (it was among the few foods he actually enjoyed), though in another he'd have minded quite a bit: he was no racist, but he strongly disliked the quality of English life being mucked about. [p.1]I had to read this sentence a couple of times before its implications really began to sink in. I mean, I have lived in the UK. I do know the terrain - to some extent, at least. What Powell appeared to me to be saying was that the area has been taken over by foreigners - the kind who eat a good deal of curry. Not only that, there is - is there not? - an implication that their very presence here constitutes some kind of affront to the "quality of English life."

Carcanet Press: Neil Powell

Carcanet Press: Neil PowellPerhaps I'm overreading it, I thought, resisting my first impulse to throw the book across the room. Surely he can't mean that. In any case, I decided to give him the benefit of the doubt and persevere.

Certainly Neil Powell knows a good story when he hears one. I'm not sure that I came across many in his pages which I hadn't already encountered in Amis's Memoirs or one of the other biographies, but they were certainly just as amusing when retold here. He also quotes lengthy passages from Amis's Letters, which reminded me of just how rib-ticklingly funny that book can be - one of the few such volumes that it actually is dangerous to be caught reading in a public place. People are liable to think that you're throwing a fit.

But is this enough? Is this really a necessary book? As D. J. Taylor puts it in his own notice of Amis and Son in the Literary Review :

On the shelf beside me as I write this are, in chronological order, Kingsley’s Memoirs (1991), Eric Jacobs’s Kingsley Amis: A Biography (1995), Martin’s Experience (2000), Zachary Leader’s edition of The Letters of Kingsley Amis (2000), Richard Bradford’s Lucky Him (2001), advertised as a ‘biography’ but in fact an exceptionally astute critical survey, and Leader’s jumbo-sized The Life of Kingsley Amis (2006). They are all interesting books, up to a point, but there are an awful lot of them and the message emerging from their three or four thousand collective pages is generally the same.I too own all of these books, and am forced - somewhat reluctantly - to concur with Taylor's opinion that "one can think of novelists twice as good who have attracted half the volume of scholarly, or not so scholarly, exegesis."

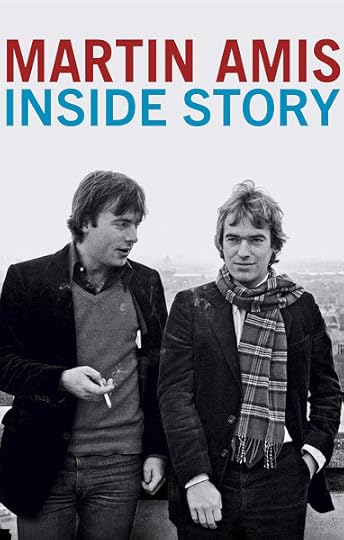

Martin Amis: Inside Story (2020)

Martin Amis: Inside Story (2020)Where there's already so much competition, justifying the appearance of yet another tome on much the same subject surely requires a bit of special pleading. So, unless Powell has an exceptionally compelling new reading of Amis père to offer (and I'm not sure that he does), his book really stands or falls on the value of any new material he can provide on Amis fils.

It's true that Powell evinces a number of opinions which are (to put it mildly) not in line with my own. He seems to take it for granted that any time spent reading Science Fiction is time wasted, and that Kingsley Amis's pioneering efforts as a critic and anthologist of the field ought therefore to be written off as simple self-indulgence. Powell even claims that Kingsley (he refers to him by his first name throughout, so I don't see why I shouldn't) would have been much better off expanding his (failed) BLitt thesis on the popular audience for Victorian poetry into a monograph than dignifying such disposable 'genre fiction' with his attention. And yet, to me, that's one of the strongest arguments in favour of Kingsley's critical acumen.

But just because I happen to disagree with many of Powell's views is no reason to dismiss them out of hand. At this point I thought it might be a good idea to see what some other readers thought of his book. There are a couple of puffs on the cover: "A delight: witty, clever and astute" - Observer, plus a blurb description of it as a "witty, opinionated and thoroughly readable critical biography"; D. J. Taylor, too, refers to it "a thoughtfully written study," in the passage from his review quoted above.

The Wheeler Centre: Peter Craven

The Wheeler Centre: Peter CravenThere was at least one writer who felt much as I did about it, however. You can, if you wish, read it for yourself on the website of the Melbourne Age for July 22, 2008, but here are a couple of quotes from Australian critic Peter Craven's review:

That's going straight for the jugular! But why exactly does he think so?

Amis and Son, Neil Powell's would-be critical biography of Kingsley Amis, author of Lucky Jim and Take a Girl Like You, and Martin Amis, his son, author of The Rachel Papers and London Fields, is ... a silly and sickening book that is liable to be taken more seriously than it deserves.

It is essentially a critical book, buttressed by biographical summary that tends to be used as an increasingly impertinent crutch for the evaluative judgements that keep jumping about between the lives and the works of Amis father and son.Certainly this is a problem if, as I've argued above, the book's raison d'être really has to be providing a substantive reading of Martin's work, rather than rehashing the far more readily available material on Kingsley. But Powell, according to Peter Craven, is:

It is less obviously debilitating in the case of Kingsley because the burden of Powell's book is that Smarty isn't half the writer that his Dad was. Smarty Anus, you'll recall, is Private Eye's empathic nickname for Martin Amis, a homage of an epithet if ever there was one.

the kind of narrow and overweeningly snooty critic who is constantly confusing the limitations of human beings with the faults of their work. It is not a vice confined to the British, but one they exhibit with a peculiar intensity and obnoxiousness.

At its worst this kind of writing is constantly sliding into what sounds like social condescension. It is especially dominant where criticism and biography meet, as in the truly appalling studies of Anthony Burgess and Laurence Olivier by Roger Lewis.

Roger Lewis

Roger LewisI, too, have read Roger Lewis's rambling and incoherent 'critical biography' of Anthony Burgess, so I do see the point Craven is making here. I haven't read Lewis on the subject of Olivier, but I do have a copy of his apparently equally venomous Life and Death of Peter Sellers lying around somewhere. Is Powell really as bad as that?

Certainly he says some odd things at times. While describing a seduction scene in Martin's The Rachel Papers (1973), which takes place to the accompaniment of the Beatles' Sergeant Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, regarded by the hero as "a safe choice, since to be against the Beatles (late-middle period) is to be against life", Powell calls 'When I'm Sixty-Four' and 'Lovely Rita':

the two songs which despite their jaunty surfaces most clearly reveal the Beatles' underlying callousness and contempt for other people. [pp.297-98]Really? Do they? Maybe I've been getting them wrong all these years. It does seem a rather extreme view, though it certainly matches up with an earlier diatribe by Powell about "a truly shocking moment in Experience", where Martin mentions:

Bach's 'Concerto for Cello', in four words conveying ignorance of musical history, the composer's oeuvre and the difference between a concerto and a sonata ... His father had been able to take a scurrilously disrespectful view of received culture precisely because he knew a good bit about it from quite early on. Martin didn't have that luxury; hence, despite his plumage, he had to become a successfully diligent gnome. [pp.288-89]Yes, Martin (or his editor) should have picked up on that mistake. But then, Powell's own book is not exactly error-free. In any case, isn't all this a bit of an overreaction? Does it really justify describing him a "successfully diligent gnome"? Perhaps it's an English thing. As my Birmingham-born friend Martin Frost once remarked to me, "It's not that you're outside the class system, Jack, it's that you're beneath it."

The nuances of class are clearly something that fascinates Powell, though one can't help feeling that he's not talking solely about the two Amises when he mounts his own "unfashionable defence" of these curious caste divides:

at least since the mid-eighteenth century, class in England has been extraordinarily fluid, enabling immense social leaps to be made within individual lifetimes ... [and] this fluidity coincides with the rise of the English novel, which has made class - in its nuances, misunderstandings and unexpected transitions - one of its major themes. [p.315]"For the novelist it remains an indispensable resource". Powell's defence of class seems to boil down to two not easily reconcilable statements: 1/ that it doesn't really work; 2/ that it's great to write about. Sometimes it's nice to be a New Zealander and not feel that you have to worry about that kind of thing.

I'm not myself a great fan of Martin Amis, whose works I stopped collecting some years back, but I have read a number of them, including Money and London Fields, and would certainly agree with Peter Craven's praise of his attempts to reclaim:

the vast underworld of London street talk and the way contemporary Britain actually talked in his mature fiction. Powell's culpable stupidity about this goes most of the way towards disqualifying him from saying anything of critical interest about Martin.In short, then:

Craven concedes that "it's easy enough to be irritated by Martin Amis."

Amis and Son is a book by a critic of some intelligence who nonetheless constantly dissipates his insights because his swaggering irritation at one of his two subjects makes him blindingly daft.

You can even go halfway with Tibor Fischer's assessment, quoted by Powell, of Martin Amis as "an atrocity-chaser ... constantly on the prowl for gravitas enlargement offers (the Holocaust, serial killers, 9/11, the Gulag, the Beslan siege) as if writing about really bad things will make him a really great novelist", and still acknowledge that, on a good day, he is one of the most significant writers in Britain to have produced fiction in the past 30 years.

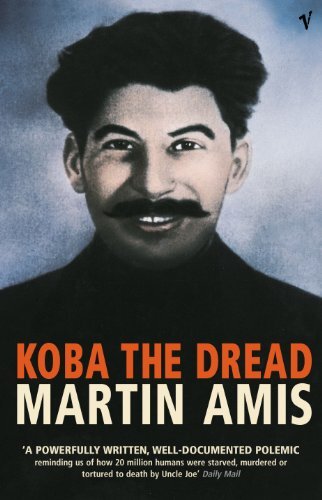

Martin Amis: Koba the Dread (2002)

Martin Amis: Koba the Dread (2002)That seems like a pretty judicious distinction to me. One of the books I have read by Martin Amis is his account of Stalin, Koba the Dread. It inspired me to verse, in fact:

There was definitely a smug, de haut en bas tone about Amis's book which I found irksome. But then, I almost died laughing at the antics of the two warring novelists in his 1995 novel The Information - you'll have noticed the clever way I've inserted a reference to it in the clerihew above - not to mention the appalling works they're respectively responsible for:

Koba the Dread: Laughter and the Twenty Million

Stalin’s a bad man I know

Martin Amis told me so

It's not exactly a revelation

but thank you for the Information

[26/9/2002]

What's your novel called?That's the book by thwarted novelist Richard Tull which causes anyone who tries to read it to start bleeding from the eyes, a condition rapidly escalating into a brain hemorrhage if they're foolish enough to persist. His rival Gwyn Barry's successful Utopia Amelior sounds equally emetic, though fortunately far less lethal.

Untitled

Don't you have a title for it yet?

No, it's called "Untitled" ...

I'm still not sure what The Information is actually about, but it's hard to care when the incidental details are as good as that. Martin Amis is certainly not a jolly or a likeable writer, but the sheer power and variety of his prose makes up for an awful lot.

One of the oddest passages in Powell's book is the one where he unpacks "one of the riddling paradoxes of fiction":

an unambitious form is one crucial respect more ambitious than an ambitious one: it is, in this sense, easier to write Ulysses than a novel by, say, Barbara Pym or C. P. Snow. Ulysses competes only with itself, with its own ambition; a novel by Pym or Snow competes with thousand others about middle-class women, strange clergymen and mendacious academics. [pp.311-12]Carried to an extreme, wouldn't this doctrine militate against Powell's earlier dismissal of Ian Fleming, one of Kingsley's favourite writers, as "a bad and pernicious author" [p.148]? I mean, isn't it harder to compete with a thousand other thrillers replete with "pornographic sadism" than to write, say, Tom Jones or Tristram Shandy? Fielding and Sterne were only competing with themselves, after all, whereas Fleming has Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett and Micky Spillane all barking at his heels ...

As one progresses through his book and encounters more and more opinions of this nature, it becomes increasingly difficult to take Powell seriously as a critic. There's an ad hominem tone to his judgements which seems driven by personal animus rather than disinterested analysis. Peter Craven, too, has difficulties with this aspect of his writing:

You're free to think that none of Martin Amis has as sure a place in the canon as Lucky Jim, but that's not the point. Powell is an interesting guide to the ins and outs of Kingsley's fiction, and some of his tips about particular books may be worth following. On the other hand he is an admirer of Martin's Time's Arrow - the Holocaust novel that runs backward - so you have to wonder.Yes, I'm with him there. For me, Time's Arrow is a one-page idea dragged out to the length of an entire novel. On the other hand, I was intrigued to see that (unlike Richard Bradford in Lucky Him), Powell likes Kingsley's late novel The Folks Who Live on the Hill as much as I do. And, while I remain unconvinced by his defence of the quasi-psychotic excesses of Stanley and the Women, it's interesting to hear his views on the matter.

Craven concludes his review as follows:

The word about this book is that it's the bollocking Martin Amis always had coming to him. It isn't, it's a spiteful and thoughtless book by a vain and shallow critic who is defeated by everything in his hugely talented contemporary that shows up his own narrowness and pettiness and lack of feeling for the rough and ready words and grand ambitions that might encompass a world or transform it in fiction."What defeats him is human beings and the way the details of a life might illuminate a writer's work." Strong words here from Craven; it's hard to dissent, though, if you've actually made your way through Powell's book. It's a pity, in particular, that he makes such great play with the (alleged) carelessness and ignorance of the two Amises when you consider his own vulnerability on this score.

To take one example. He concludes, on p.371, a long denunciation of Martin's use of Americanisms in his prose by saying that a writer's job is "To purify the dialect of the tribe" - a dictum he attributes to T. S. Eliot. While it's true that this phrase does indeed appear in Part II of "Little Gidding" (1942), the last of Eliot's Four Quartets, it is actually (of course), an Englishing of Mallarmé's famous line "Donner un sens plus pur aux mots de la tribu" from the sonnet "Le tombeau d'Edgar Poe".

There's a double irony in this. Powell's view of Amis's prose style as "veering away as far as possible from an English conversational voice towards a demotic statelessness" would surely apply far better to the work of the deracinated American T. S. Eliot than to unrepentant Londoner Martin Amis? And, given that Mallarmé attributed this purification of the "tribal" dialect to another American, Edgar Allan Poe, its use as a guarantor of "Englishness" here seems particularly eccentric.

Edgar Allan Poe (1970s)

Edgar Allan Poe (1970s)But if Powell's book is so bad, why waste so much time and energy on it? It's a fair question. I suppose that the answer might be because I wanted it to be better than it is. For my all my reading and rereading of their works, I still find even the elder Amis - let alone the younger - something of a mystery.

Since I know so much less about Martin than Kingsley, it was really this aspect of Powell's book that I hoped to learn most from. I've read almost all of the novels he analyses - the early to mid-career ones - and was surprised to find how little validity I found in his assessments of them. The two most - to me - doctrinaire and mechanical, Success and Time's Arrow, he rates most highly, whereas the verbal pyrotechnics of Money, London Fields, and The Information seem to leave him cold.

Mind you, there's no accounting for tastes, and there's no moral obligation on him to like these books. I'm not sure that I exactly like them myself. But I do agree with Peter Craven about the immense gravitas of the task Martin Amis set himself in attempting to reclaim "the vast underworld of London street talk and the way contemporary Britain actually talked in his mature fiction."

Like Dickens, Martin Amis has trouble with plots: there's always either too much or too little of it in all of his novels. But that's not really why I read them. Not purely for pleasure, but for "news that stays news" (to employ another Americanism) - in this case, news about the language.

In any case, Powell's book is clearly not the one I need. Maybe, in fact, I don't need any more critical books or biographical accounts of either author, but simply to reimmerse myself in their works. If so, I should probably tender some thanks to Neil Powell for reminding me of that.

Kingsley & Martin (1970s)

Kingsley & Martin (1970s)•

Kingsley Amis (1989)

Kingsley Amis (1989)Sir Kingsley William Amis

(1922-1995)

Poetry:

Bright November (1947)[Bright November: Poems. London: the Fortune Press, n.d. (1947?)] A Frame of Mind (1953) Poems. Fantasy Portraits (1954)A Case of Samples: Poems 1946–1956 (1956)The Evans County (1962)A Look Round the Estate: Poems, 1957–1967 (1968)Collected Poems 1944–78 (1979)Collected Poems 1944-1979. London: Hutchinson & Co. (Publishers) Ltd., 1979.

Novels:

The Legacy (1948) [unpublished]Lucky Jim (1954)Lucky Jim: A Novel. 1953. London: Victor Gollancz, Ltd., 1954. That Uncertain Feeling (1955)That Uncertain Feeling. 1955. Four Square Books Ltd. London: New English Library Ltd. / Sydney. Horwitz Publications Inc. Pty. Ltd., 1962. I Like It Here (1958)I Like it Here. 1958. Penguin Book 2884. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1968. Take a Girl Like You (1960)Take A Girl Like You. 1960. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1976. One Fat Englishman (1963)One Fat Englishman. 1963. Penguin Book 2417. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966. [with Robert Conquest] The Egyptologists (1965)[with Robert Conquest. The Egyptologists. 1965. Panther Books Ltd. Frogmore, St Albans, Herts: Granada Publishing Limited, 1975. The Anti-Death League (1966)The Anti-Death League. 1966. Penguin Book 2803. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1968. [as Robert Markham] Colonel Sun: A James Bond Adventure (1968)[as ‘Robert Markham’]. Colonel Sun: A James Bond Adventure. 1968. London: Pan Books Ltd., n.d. I Want It Now (1968)I Want It Now. 1968. London: Panther Books, 1969. The Green Man (1969)The Green Man. London: Jonathan Cape Ltd., 1969. Girl, 20 (1971)Girl, 20. 1971. London: The Book Club, by arrangement with Jonathan Cape Ltd., 1972. The Riverside Villas Murder (1973)The Riverside Villas Murder. 1973. London: Book Club Associates / Jonathan Cape Ltd., 1974. Ending Up (1974)Ending Up. London: Jonathan Cape Ltd., 1974. The Crime of the Century (1975)The Crime Of The Century. 1975. Introduction by the Author. Everyman Paperbacks: Mastercrime. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1987. The Alteration (1976)The Alteration. 1976. Triad / Panther Books. Frogmore, St Albans, Herts: Triad Paperbacks Ltd, 1978. Jake's Thing (1978)Jake's Thing. 1978. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1979. Russian Hide-and-Seek (1980)Russian Hide-and-Seek: A Melodrama. 1980. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1981. Stanley and the Women (1984)Stanley and the Women. London: Hutchinson & Co. (Publishers) Ltd., 1984. The Old Devils (1986)The Old Devils. 1986. Hutchinson. London: Century Hutchinson Ltd., 1986. Difficulties with Girls (1988)Difficulties With Girls. 1988. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1989. The Folks That Live on the Hill (1990)The Folks That Live on the Hill. Hutchinson. London: Century Hutchinson Ltd, 1990. We Are All Guilty (1991)We Are All Guilty. London: Reinhardt Books / Viking, 1991. The Russian Girl (1992)The Russian Girl. 1992. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1993. You Can't Do Both (1994)You Can't Do Both. Hutchinson. London: Random House (UK) Ltd., 1994. The Biographer's Moustache (1995)The Biographer's Moustache. 1995. Flamingo. London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1996. Black and White (c.1995) [unfinished]

Short Stories:

My Enemy's Enemy (1962)My Enemy's Enemy. 1962. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1965. Collected Short Stories (1980)Collected Short Stories. 1980. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983. Mr Barrett's Secret and Other Stories (1991)Mr Barrett's Secret and Other Stories. 1993. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1994. Complete Stories (1980)Complete Stories. Foreword by Rachel Cusk. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin, 2011.

Non-fiction:

Socialism and the Intellectuals. Fabian Society pamphlet (1957)New Maps of Hell: A Survey of Science Fiction (1960)New Maps of Hell: A Survey of Science Fiction. 1960. A Four Square Book. London: New English Library Limited., 1963. The James Bond Dossier (1965)The James Bond Dossier. 1965. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1966. [as Lt.-Col William ('Bill') Tanner] 1965 The Book of Bond, or Every Man His Own 007 (1965)What Became of Jane Austen?, and Other Questions (1970)What Became of Jane Austen?, and Other Questions. 1970. Panther Books Limited. London: Granada Publishing Limited, 1972. On Drink (1972)On Drink. Pictures by Nicolas Bentley. 1972. Panther Books Ltd. Frogmore, St Albans, Herts: Granada Publishing Limited, 1974. Rudyard Kipling and His World (1974)Everyday Drinking (1983)Every Day Drinking. Illustrated by Merrily Harpur. London: Hutchinson & Co. (Publishers) Ltd., 1983. How's Your Glass? (1984)The Amis Collection (1990)The Amis Collection: Selected Non-Fiction, 1954-1990. Introduction by John McDermott. 1990. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1991. Memoirs (1991)Memoirs. Hutchinson. London: Random Century Group Ltd., 1991. The King's English: A Guide to Modern Usage (1997)The King’s English: A Guide to Modern Usage. London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1997. Everyday Drinking: The Distilled Kingsley Amis. ['On Drink' (1972); 'Everyday Drinking' (1983); 'How's Your Glass?' (1984)]. Introduction by Christopher Hitchens (2008)

Edited:

[with Robert Conquest] Spectrum anthology series. 5 vols (1961-66)Spectrum I: A Science Fiction Anthology. Ed. Kingsley Amis & Robert Conquest. 1961. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1964.Spectrum II: A Second Science Fiction Anthology. Ed. Kingsley Amis & Robert Conquest. 1962. Pan Science Fiction. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1965.Spectrum III: A Third Science Fiction Anthology. Ed. Kingsley Amis & Robert Conquest. London: Victor Gollancz, Ltd., 1963.Spectrum IV: A Fourth Science Fiction Anthology. Ed. Kingsley Amis & Robert Conquest. 1965. Pan Science Fiction. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1967.Spectrum V: A Fifth Science Fiction Anthology. Ed. Kingsley Amis & Robert Conquest. 1966. Pan Science Fiction. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1969. G. K. Chesterton. Selected Stories (1972)The New Oxford Book of Light Verse (1978)The New Oxford Book of Light Verse. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978. The Golden Age of Science Fiction (1981)The Golden Age of Science Fiction. London: Hutchinson & Co. (Publishers) Ltd., 1981. The Amis Anthology: A Personal Choice of English Verse (1988)

Letters:

The Letters of Kingsley Amis. Ed. Zachary Leader (2000)Leader, Zachary, ed. The Letters of Kingsley Amis. London: HarperCollins Publishers, 2000.Leader, Zachary, ed. The Letters of Kingsley Amis. 2000. Rev. ed. London: HarperCollins Publishers, 2001.

Secondary:

Jacobs, Eric. Kingsley Amis: A Biography. Hodder & Stoughton. London: Hodder Headline PLC, 1995.Bradford, Richard. Lucky Him: The Life of Kingsley Amis. London: Peter Owen Publishers, 2001.Leader, Zachary. The Life of Kingsley Amis. 2006. Vintage Books. London: The Random House Group Limited, 2007.

•

Martin Louis Amis

(1949- )

Novels:

The Rachel Papers (1973)The Rachel Papers. 1973. Frogmore, St Albans, Herts: Granada Publishing Limited, 1976. Dead Babies (1975)Dead Babies. 1975. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1988. Success (1978)Success. 1978. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1988. Other People (1981)Other People: A Mystery Story. 1981. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1988. Money (1984)Money: A Suicide Note. 1984. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1986. London Fields (1989)London Fields. London: Jonathan Cape Ltd., 1989. Time's Arrow: Or the Nature of the Offence (1991)Time's Arrow, or The Nature of the Offence. 1991. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1992. The Information (1995)The Information. 1995. Flamingo. London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1995. Night Train (1997)Yellow Dog (2003)House of Meetings (2006)The Pregnant Widow (2010)Lionel Asbo: State of England (2012)The Zone of Interest (2014)The Zone of Interest. Jonathan Cape. London: Random House, 2014. Inside Story (2020)

Short stories:

Einstein's Monsters (1987)Two Stories (1994)God's Dice (1995)Heavy Water and Other Stories (1998)Heavy Water and Other Stories. 1998. Vintage. London: Random House UK Limited, 1999. Amis Omnibus (1999)The Fiction of Martin Amis (2000)Vintage Amis (2004)

Screenplays:

Saturn 3 (1980)London Fields (2018)

Non-fiction:

Invasion of the Space Invaders (1982)The Moronic Inferno: And Other Visits to America (1986)The Moronic Inferno, and Other Visits to America. 1986. King Penguin. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1987. Visiting Mrs Nabokov: And Other Excursions (1993)Experience (2000)Experience. 2000. Vintage. London: The Random House Group Limited, 2001. The War Against Cliché: Essays and Reviews 1971–2000 (2001)Koba the Dread: Laughter and the Twenty Million (2002)Koba the Dread: Laughter and the Twenty Million. 2002. Vintage. London: The Random House Group Limited, 2003. The Second Plane (2008)The Rub of Time: Bellow, Nabokov, Hitchens, Travolta, Trump. Essays and Reportage, 1986–2016 (2017)

Secondary:

Powell, Neil. Amis & Son: Two Literary Generations. Macmillan. London: Pan Macmillan Ltd., 2008.

Father and Son? (2020)

Father and Son? (2020)

Published on May 13, 2023 15:55

May 8, 2023

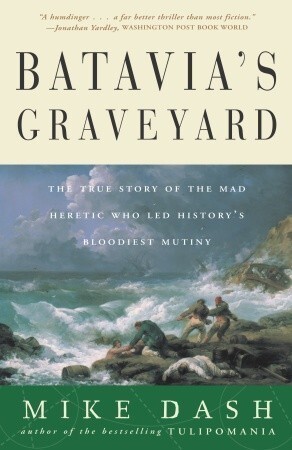

The Wreck of the Batavia

Mike Dash: Batavia's Graveyard (2002)

Mike Dash: Batavia's Graveyard (2002)The other day I picked up a second-hand copy of Mike Dash's Batavia's Graveyard, a sober, no-nonsense account of what his publishers describe as "history's bloodiest mutiny."

The subject is far from novel for me. I remember as a young boy watching a documentary called "The Wreck of the Batavia" which left me with nightmares for weeks afterwards. I don't know if I've ever quite got over it, in fact: especially some of the reenactments where the chief mutineer's henchmen hunted down their victims with knives in the shallow waters of the reef that surrounded them.

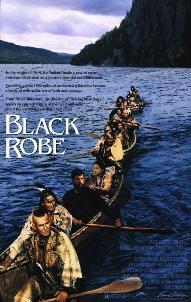

Bruce Beresford, dir.: The Wreck of the Batavia (1973)

Bruce Beresford, dir.: The Wreck of the Batavia (1973)It doesn't surprise me that this film turns out to have been an early work by renowned Australian director Bruce Beresford. There was a horrible authenticity about the live action sequences, in particular, which seems to prefigure the future creator of Breaker Morant , and - in particular - one of my favourite movies of all time, Black Robe .

Bruce Beresford, dir.: Black Robe (1991)

Bruce Beresford, dir.: Black Robe (1991)Another important - though unjustly neglected - work inspired by the event is Australian writer Henrietta Drake-Brockman's novel The Wicked and the Fair, which, despite the garish cover-picture below, is quite an interesting and serious work.

Henrietta Drake-Brockman: The Wicked and the Fair (1957)

Henrietta Drake-Brockman: The Wicked and the Fair (1957)She followed it up with a factual account based on her own extensive local as well as archival research: Voyage to Disaster (1963). Even Mike Dash is forced to admit a considerable debt to this ground-breaking book, though he tempers his admiration for her thoroughness with some rather grudging remarks about her frustrating lack of clear indexing.

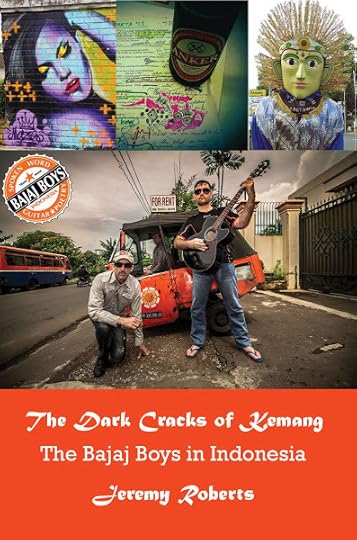

Jeremy Roberts: The Dark Cracks of Kemang: The Bajaj Boys in Indonesia (2022)

Jeremy Roberts: The Dark Cracks of Kemang: The Bajaj Boys in Indonesia (2022)Why did this story leave such an indelible mark on me? Recently I've been reading poet Jeremy Roberts' account of his own time in Indonesia - in Jakarta, in fact, the 'Batavia' of the Dutch colonists.

One can read in every line of his book his simultaneous attraction / repulsion for the chaotic city and its teeming sea of inhabitants. I've never visited Indonesia, so can't really comment, but my own travels in Thailand and India give me some hint of what he's talking about - that incommunicable atmosphere one feels in a large sprawling Eastern urban centre, especially at evening, when the heat of the day recedes and everyone comes out on the street to eat and talk.

Of course, though Batavia was the planned destination for the ship, in fact the Batavia itself never got there. It was wrecked off the coast of Western Australia. It's possible, in fact, that two of the mutineers eventually marooned on the mainland were the first Europeans to set foot on the lucky country. Batavia, capital of the Dutch East Indies, is where the rest of the survivors ended up, though.

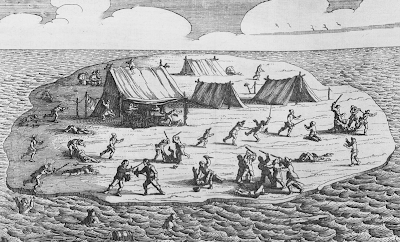

Massacre of the Batavia's survivors (1628)

Massacre of the Batavia's survivors (1628)I suppose that it was the nightmarish revelation of just how far - to what insane and illogical extremes - a truly charismatic leader can go which affected me most about the story. To the very end, even when he stood in front of the gallows, the murderous Jeronimus Cornelisz was still trying to bargain his way out of any responsibilty for what had taken place. The man who had ordered so many deaths for his own amusement could not credit that the same thing might actually happen to him.

In the Bruce Beresford documentary he's described as an Anabaptist - certainly he had idiosyncratic religious views, which included a conviction that any idea that came to him must come from God, and that therefore anything he did, regardless of whether or not it might be considered conventionally "sinful", was ipso facto justified.

Saki: Sredni Vashtar (1912)

Saki: Sredni Vashtar (1912)The only previous association I had with the word "Anabaptist" came from the Saki story "Sredni Vashtar", where the sickly, neglected boy Conradin has only two friends: "a ragged-plumaged Houdan hen, on which the boy lavished an affection that had scarcely another outlet", and "a large polecat-ferret", which lived in a cage at the back of the tool-shed he spent most of his time in.

And one day, out of Heaven knows what material, he spun the beast a wonderful name, and from that moment it grew into a god and a religion.The Houdan hen, however,

was never drawn into the cult of Sredni Vashtar. Conradin had long ago settled that she was an Anabaptist. He did not pretend to have the remotest knowledge as to what an Anabaptist was, but he privately hoped that it was dashing and not very respectable.Conradin's loathsome guardian Mrs. de Ropp is unimpressed with his choice of a place to play, and announces one morning at breakfast that the hen has been sold and taken away:

With her short-sighted eyes she peered at Conradin, waiting for an outbreak of rage and sorrow ... But Conradin said nothing; there was nothing to be said. Something perhaps in his white set face gave her a momentary qualm, for at tea that afternoon there was toast on the table ...Sredni Vashtar comes through for his worshipper, though. When Mrs. de Ropp goes down to find out just what Conradin has been hiding at the back of the shed ("I believe it's guinea-pigs. I'll have them all cleared away") she gets a little more than she bargained for:

out through that doorway came a long, low, yellow-and-brown beast, with eyes a-blink at the waning daylight, and dark wet stains around the fur of jaws and throat.It's hard not to cheer as the "great polecat-ferret made its way down to a small brook at the foot of the garden, drank for a moment, then crossed a little plank bridge and was lost to sight in the bushes." And yet - much though, like most readers, I relish his triumph - it's disturbing to sense a little of Cornelisz in Coradin, with his great choric hymn:

Sredni Vashtar went forth,

His thoughts were red thoughts and his teeth were white.

His enemies called for peace but he brought them death,

Sredni Vashtar the Beautiful.

Execution of Cornelisz and the Other Mutineers (1628)

Execution of Cornelisz and the Other Mutineers (1628)

Published on May 08, 2023 18:56

May 1, 2023

The Road Not Taken

Richard von Sturmer: doppelgänger (9/12/2020)

The Interrupted JourneyYesterday I packed up my office at the University of Waikato and am now back in Auckland. When I was passing the photo wall in the foyer of the Arts building, I saw you and wondered, “What is Jack doing here?” Looking closer, your hair was the wrong colour. But in the background there was the message “Ross the face of.” Sort of Yoda-speak. It left me rather confused. And why are you, if it is you, why are you holding up an illustrated map of the Central North Island? I’m still a bit perplexed.- Richard von Sturmer, email to JR (9/12/2020)When Richard sent me the image above with the query: ‘Is this you?’ I too felt quite perplexed. The photo does indeed look quite a lot like me. The words ROSS THE FACE OF are also unequivocal, but the Central North Island is certainly not a region with which I have any particular affinity. My roots lie more in Northland.

Another interesting thing about it is that it shows a middle-aged man with full cheeks, narrow-rimmed glasses and ruffled orange hair. I have the full cheeks and the glasses, but my hair is dark brown going on grey. I did once have it dyed, in a moment of feverish reinvention, during a trek in Thailand. The idea was to go blond, but unfortunately, due to the hairdresser’s unfamiliarity with European hair, it came out orange instead.

So, yes, I did once have hair to match that in the picture, but I was much thinner and younger-looking then – it was more than two decades ago – so while all those attributes have certainly belonged to me at one point or another, I never had them all at the same time: in this part of the multiverse, at any rate.Gabriel White: Jack in Mumbai (15/1/2002)

Another perturbing recent event involved one of those late night searches to confirm your own existence, which in this case took the form of a series of clicks on the ISBN codes for my own books.

Most of them were fine – they duly led to the publication in question – but one of them came up with quite another book. Presumably the National Library had made a mistake, and confused one obscure small publication with another. I had a lot of problems with that book, in fact: it was an anthology of student life writing, and I decided to title it [your name here] in order to gesture (as I thought cleverly), at the essential interchangeability of all such human experiences.

Unfortunately the librarians took that title to be a mere stand-in for the actual title still to come, and refused to list it in their catalogue under that appellation. I had to explain to them again and again just what I had in mind before they would relent. Indexing a title which begins with a square bracket also offers some unique challenges for both human and machine intelligence.

I wonder if John Ashbery had the same problems with his own 1998 book of poems Your Name Here, which appeared a few years after my stroke of bravado? Whether he did or not, any merit there may have been in this jeu d’esprit has now been eclipsed by the so-many-times-brighter magnitude of his star.

•

All of which brings me to the principal pretext for this meditation. The other day I made a surprising find: a large grey volume of variations and additions to Georges Perec’s famed 1979 short story ‘Le Voyage d’hiver’ [The Winter Journey] by members of the European experimental literature club Oulipo [[OUvroir de LIttérature POtentielle] = Workshop of Potential Literature].Georges Perec / Oulipo. Le Voyage d’hiver & ses suites. Postface de Jacques Roubaud. La Librairie du XXIe Siècle. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 2013.

The reason this seemed so strange is that I’m the only local Perec enthusiast I know of (despite all my best efforts to turn others onto his work), so it’s hard to see how this particular volume ended up, second-hand, in a vintage bookshop in Auckland.

What’s more, this particular story is probably my favourite among all of his fictions. It has a strange atmospheric charm to it which seems – to me at least – almost to outweigh its admittedly intriguing hypothesis.

The conceit of the story is that a single author, Hugo Vernier, wrote an obscure book in the mid-nineteenth century which anticipated not just the ideas but even the verbal substance of most of the greatest works of French poetry from Baudelaire onwards. Unfortunately the one copy of this work seen and scrutinised by the protagonist is torn from him by the fortunes of war. His Winterreise, winter journey, takes place in 1940, just before the fall of France, and he is never able to relocate the book subsequently.

The various members of Oulipo run with this basic idea of anticipation and turn it into an extraordinary farrago of counter-plots involving Hitler, J. Edgar Hoover, and a whole raft of Journeys here, there and everywhere.

A good deal of the merit of Perec’s story comes from its brevity. This book of sequels is over 400 pages long. So where did it come from? How did it end up on the neglected ‘foreign language’ shelf of a city bookshop? Did it belong to some visiting scholar, compelled to abandon their luggage by the demands of the coronavirus? Or a local experimental literature fanatic, who either read and forgot it, or else found the somewhat demanding idiom of some of the stories beyond their linguistic abilities?

Not that I found them particularly easy going either. The only way I got through them, in fact, was to ration myself to just one of the 26 voyages per diem (a device I’ve employed before to get through seemingly impossible reading tasks: the whole of Proust in French, for instance, or the multiple discursive volumes of Casanova’s memoirs).

Most of the stories in the Oulipo book are predictable enough: more-or-less ingenious variations on the forest of themes built up by their predecessors – since the concept of this group of stories as a ‘roman collectif’ appears to have arisen fairly early in the piece.

As I kept on reading, though, the conviction that they’d somehow missed the point of Perec’s story grew and grew. His protagonist’s fortuitous discovery of Vernier’s book is the central moment in his existence mainly because he allows it to be. The rest of his life is spent in a futile search for it as a way of recovering not so much the artefact itself as that lost moment.

It was, after all, the last instant at which France – or even European civilisation – could be said to have been truly itself, before the events of June 1940, the Nazis processing through Paris, the long inexorable ‘Night and Fog’ of the occupation.

Vernier’s book was an apport from an unknown, frankly impossible past. Its very existence adds to but does not cause the uncanny atmosphere of Perec’s story, one of the last he was to publish before his untimely death at the age of 45.