Jack Ross's Blog, page 4

October 17, 2024

Hammett & Hellman

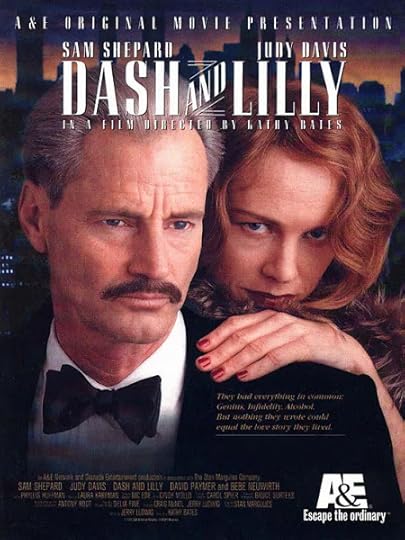

Kathy Bates, dir.: Dash and Lilly (2000)

Kathy Bates, dir.: Dash and Lilly (2000)The reality may not have been quite so glamorous as the picture above, but it's fair to say that they were, in their way, a handsome pair:

Lillian Hellman & Dashiell Hammett

Lillian Hellman & Dashiell HammettHere are the two of them again, from Fred Zinneman's 1977 movie Julia , based on a chapter from Lillian Hellman's memoir Pentimento: A Book of Portraits (1973):

Julia: Jane Fonda as Hellman & Jason Robards as Hammett (1977)

Julia: Jane Fonda as Hellman & Jason Robards as Hammett (1977)They've become one of those legendary couples, like Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, Clark Gable and Carole Lombard - or Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh. Lillian Hellman and Dashiell Hammett, too, were in show business, but on the typewriter side of the ledger rather than in front of the camera.

Except once.

They were also pretty dedicated Communists. Hammett was sent to prison in 1951 when the Civil Rights Congress, of which he was president, was designated a Communist front group by the US Attorney General. He spent over a year in jail for refusing to name any of the people who had contributed to the CRC bail fund, and who might therefore have been liable to being accused of being Reds or Fellow Travellers:

Instead, on every question regarding the CRC or the bail fund, Hammett declined to answer, citing the Fifth Amendment, refusing to even identify his signature or initials on CRC documents the government had subpoenaed.On his release, he was definitively blacklisted, after refusing to cooperate or name names during a further appearance before HUAC, Senator Joseph McCarthy's House Un-American Activities Committee. This had the effect of depriving him of any income from his books or films for virtually the rest of his life.

Perhaps it's sentimental of me, but I find it difficult to argue with Hellman's verdict that he submitted to prison rather than reveal the names of the contributors to the fund because "he had come to the conclusion that a man should keep his word."

The fact that he subsequently revealed that he didn't actually know any of their names - he'd had nothing to do with that particular piece of fund-raising - adds the essential touch of deadpan Hammettian irony to the whole sorry affair.

Lewis Milestone, dir.: The North Star (1943)

Lewis Milestone, dir.: The North Star (1943)Hellman herself is a more complex case. She was definitely sympathetic to the Communist line, and her wartime propaganda film North Star shows the most naive attitudes towards Stalinist Russia. However, one should add in her defence that every attempt she made to introduce a tincture of realism into the script was immediately vetoed by the studio.

Despite its absurdities, the film was unexpectedly popular in Russia, as she found when she was despatched on a semi-official visit to America's wartime ally a few months later.

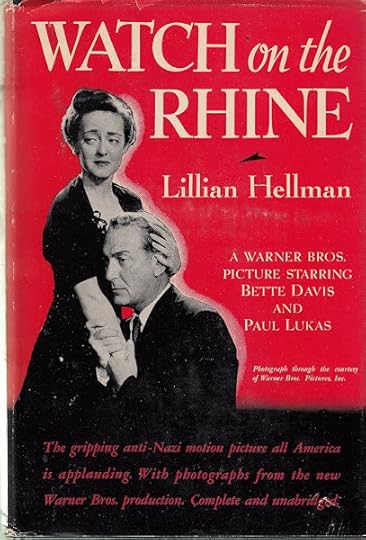

Lillian Hellman: Watch on the Rhine (1941)

Lillian Hellman: Watch on the Rhine (1941)More significantly, at the height of the Nazi-Soviet pact, when anyone toeing the the Communist party line was strictly forbidden from criticising Hitler, her popular stage play "The Watch on the Rhine" argued a fiercely anti-Nazi position. She can hardly therefore be accused of being a simple tool of the party, given the amount of criticism she received from her more radical colleagues for this act of deviationism at the time.

A few months later, after Hitler's invasion of Russia, the same people were queueing up to praise Hellman's "prescient" play to the skies.

Lillian Hellman: Scoundrel Time (1941)

Lillian Hellman: Scoundrel Time (1941)Hellman's own testimony before HUAC remains a controversial matter to this day. Like Hammett, she refused to name names. However, having seen the effect it had on him, she was also anxious to avoid going to prison, which would have been the inevitable result of her willingness to testify on some matters - such as her own activities in the 1930s and 1940s - but not others, i.e. the names of the people who had participated in the committees and congresses she attended at the time.

Her lawyer, Joseph Rauh, experienced in these matters, advised her to record her views in a letter to the Chairman of the Committee, and then ask to be allowed to read it out at the hearing. While the Committee rejected her request to be permitted to testify only about herself but not others, they did agree to enter her letter into the record.

The moment that decision was handed down, Rauh's assistant promptly started to distribute printed copies of the letter to as many as possible of the journalists present, despite strenuous attempts to stop him by the Committee's security guards. Hellman's (and Rauh's) letter was a rhetorical masterpiece, with one phrase in particular which has gone down in history:

I do not like subversion or disloyalty in any form and if I had ever seen any I would have considered it my duty to have reported it to the proper authorities. But to hurt innocent people whom I knew many years ago in order to save myself is, to me, inhuman and indecent and dishonorable. I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year's fashions [my emphasis], even though I long ago came to the conclusion that I was not a political person and could have no comfortable place in any political group. I was raised in an old-fashioned American tradition and there were certain homely things that were taught to me: to try to tell the truth, not to bear false witness, not to harm my neighbour, to be loyal to my country, and so on. In general, I respected these ideals of Christian honor and did as well as I knew how. It is my belief that you will agree with these simple rules of human decency and will not expect me to violate the good American tradition from which they spring. I would therefore like to come before you and speak of myself.You can't send the grand old lady of American Theatre to jail after she's trumpeted "I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year's fashions" right in your face. The committee saw that they'd been out-grandstanded, and were forced to content themselves with the inevitable blacklisting and loss of all income which followed her appearance before them.

Somewhat of a Pyrrhic victory, one might say, but a victory nevertheless.

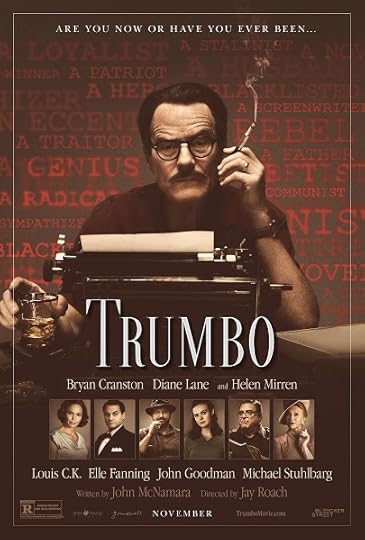

Jay Roach, dir.: Trumbo (2015)

Jay Roach, dir.: Trumbo (2015)So were Hammett and Hellman heroes or villains? Neither, really. They were certainly criminally naive in their judgement of Stalin and Stalinism, but it's hard to see laissez-faire Capitalism as all that much better in the various ways it's raped and pillaged the world we've inherited from these warring ideologies.

Certainly portraying McCarthyism as an evil commensurate with the Soviet gulag, as politically simplistic films such as Trumbo implicitly do, is not really a viable position - but I suppose it's the ease with which all democratic safeguards were set aside in the late 1940s and 1950s which explains why we keep on returning to this period again and again: whether the stricken hero in question be Oppenheimer, Trumbo, or Dashiell Hammett.

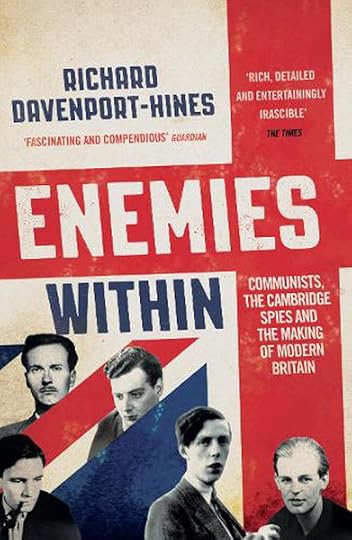

Richard Davenport-Hines: Enemies Within (2019)

Richard Davenport-Hines: Enemies Within (2019)The situation in Britain at this time was complicated by the undeniable presence of actual Communist agents at the highest levels of the government and, in particular, the secret services. Richard Davenport-Hines' recent, rather hysterical, book on the subject attempts to argue that the real damage done by Burgess, Philby, Maclean and co. was to the public's faith in Establishment values.

He attributes BREXIT and various other contemporary follies to the fact that people no longer trust any information that reaches them from "official" channels. Oddly, he fails to see any problem with the actual falsehoods peddled by successive British governments beyond the fact that no-one seems inclined to believe them on their mere say-so anymore.

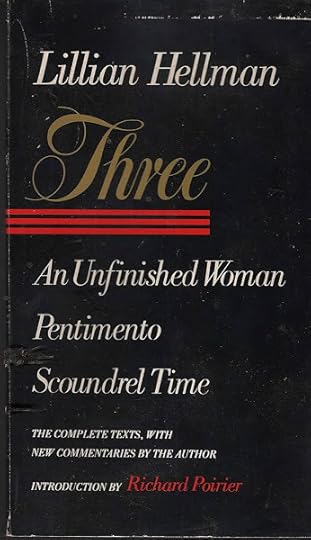

Lillian Hellman: Three: An Unfinished Woman, Pentimento & Scoundrel Time (1979)

Lillian Hellman: Three: An Unfinished Woman, Pentimento & Scoundrel Time (1979)After Hammett's death - and without his restraining critical influence - Hellman decided to set the record straight in a set of very selective and, it would now appear, heavily fictionalised memoirs.

In Pentimento, in particular, she wrote a long section about an old friend of hers, disguised under the pseudonym "Julia", who'd been a political activist in Spain, then Austria, in the late 1930s, and who once asked Hellmann to smuggle some funds to her through Nazi Germany to support the anti-Fascist cause.

The actual existence of this Julia - played by Vanessa Redgrave alongside Jane Fonda's Lillian Hellman in the 1977 film of the same name - has been called into question. It's also been suggested that Julia may have been based on the Freudian psychiatrist Muriel Gardiner, who was indeed active in anti-Fascist politics in Austria at the time.

Hellman, however, denied it, and continued to claim that her story was true, despite the fact that she'd had to change her friend's name. Nor had she ever met Muriel Gardiner. As she wrote to the film's producer at the time:

I do not deny the danger I was in when I took the money into Germany ... And nobody and nothing can change that unless you write a fictional and different story ... Isn't it necessary to know that I am a Jew? That, of course, is what mainly made the danger.Entertaining though they are, and successful though they were at the time, these books gave her enemies all the ammunition they needed to cut her down to size once and for all. Mary McCarthy, in particular, an ex-Trotskyite who'd maintained her hatred of Stalinists since the late 1930s, took the opportunity to denounce Hellman in no uncertain terms on an episode of the Dick Cavett Show:

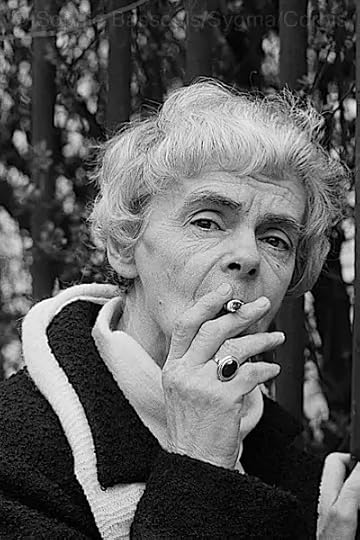

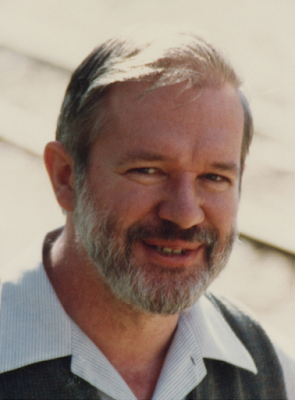

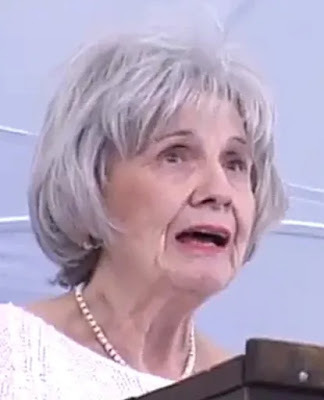

Mary McCarthy (1912-1989)

Mary McCarthy (1912-1989)McCarthy ... called Hellman “a bad writer, overrated, a dishonest writer” during an interview with TV host Dick Cavett on his national talk show in late January of 1980. When Cavett asked what exactly was dishonest about Hellmann, McCarthy replied, "Everything. I once said in an interview that everything she writes is a lie, including 'and' and 'the.'"Hellman promptly sued McCarthy for libel, and the case limped along without coming to trial - despite McCarthy's unavailing attempts to have it dismissed on the grounds that "her comments were simply her opinions about a public figure" - until it was abandoned by Hellman's executors after her death in mid-1984.

Admirers of McCarthy's waspish wit continue to quote that "everything she writes is a lie, including 'and' and 'the'" bon mot with glee. Long ago bitchiness from famous figures - even that of long-faded littérateurs such as Mary McCarthy - tends to have that effect.

For myself, despite all the personal and political stumbles she undoubtedly made in her long life, despite all her grande dame affectations and her admitted elisions of history, I find that Hellman appeals to me in a way her two principal detractors - both of them surnamed McCarthy, oddly enough - do not.

Beth Lipson: Lillian Hellman and Dashiell Hammett

Beth Lipson: Lillian Hellman and Dashiell HammettFor all its ups-and-downs and complexities, the Hellman-Hammett alliance still has a certain lustre to it. They may have been complex, flawed people, but they were willing to put everything on the line when it counted. Hellman's famous letter to the committee was certainly a very calculated act of defiance, but defiant it undoubtedly was:

... to hurt innocent people whom I knew many years ago in order to save myself is, to me, inhuman and indecent and dishonorable. I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year's fashions ... I was raised in an old-fashioned American tradition and there were certain homely things that were taught to me: to try to tell the truth, not to bear false witness, not to harm my neighbour, to be loyal to my country, and so on. In general, I respected these ideals of Christian honor and did as well as I knew how.That phrase about "Christian honor" may sound a little discordant to us now, but when you consider it comes from a Jewish woman writer, one who fought Hitler and Fascism long before it became fashionable, it takes on a more complex meaning.

This was a woman who dispassionately analysed the wrongs of her own family and caste in such plays as The Little Foxes (1939), wrote presciently about witch-hunts in her first play The Children's Hour (1934), and who thought nothing of defying every convention of "womanly" behaviour in her own private life.

She was, in short, every male chauvinist's worst nightmare. The laconic Dashiell Hammett needs no defence from me or anyone else, given his almost mythic status in American letters. I do, however, think it's high time for a bit more celebration of his partner in life and literature, Lillian Hellman.

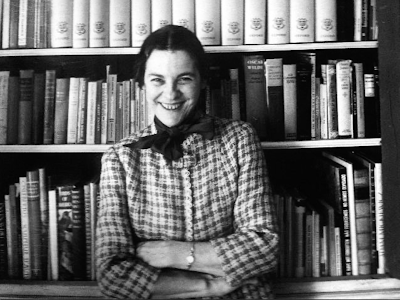

Carl Rollyson: Lillian Hellman: Her Life and Legend (1912-1989)

Carl Rollyson: Lillian Hellman: Her Life and Legend (1912-1989) Lillian Hellman (1935)

Lillian Hellman (1935)Lillian Florence Hellman

(1905–1984)

Books I own are marked in bold:Plays:

The Children's Hour (1934)Days to Come (1936)The Little Foxes (1939)The Little Foxes: A Play in Three Acts. New York: Random House, 1939. Watch on the Rhine (1941)Four Plays: The Children's Hour / Days to Come / The Little Foxes / Watch on the Rhine (1942)The Searching Wind (1944)Another Part of the Forest (1946)Montserrat [Adapted from Emmanuel Robles' play] (1949)The Autumn Garden (1951)The Lark [Adapted from Jean Anouilh's play L'Alouette] (1955)Toys in the Attic (1960)Six Plays: The Children's Hour / Days to Come / The Little Foxes / Watch on the Rhine / Another Part of the Forest / The Autumn Garden (1960)My Mother, My Father and Me [Adapted from Burt Blechman's novel How Much?] (1963)The Collected Plays: The Children's Hour / Days to Come / The Little Foxes / Watch on the Rhine / The Searching Wind / Another Part of the Forest / Montserrat / The Autumn Garden / The Lark / Candide / Toys in the Attic / My Mother, My Father and Me (1972)

Novel:

Maybe: A Story (1980)

Operetta:

Candide (1956)

Screenplays:

[with Mordaunt Shairp] The Dark Angel [based on the play by Guy Bolton] (1935)These Three [based on her play The Children's Hour] (1936)Dead End [based on the play by Sidney Kingsley] (1937)The Little Foxes [based on her play] (1941)The North Star (1943)The Searching Wind [based on her play] (1946)The Chase [based on the play by Horton Foote] (1966)

Memoirs:

An Unfinished Woman: A Memoir (1969)Pentimento: A Book of Portraits (1973)Scoundrel Time (1976)Three (1979)Three: An Unfinished Woman: A Memoir / Pentimento / Scoundrel Time: With New Commentaries by the Author. 1969, 1973 & 1976. Introduction by Richard Poirier. London: Macmillan London Limited, 1979. [with Peter Feibleman] Eating Together: Recipes and Recollections, with Peter Feibleman (1984)

Edited:

The Selected Letters Of Anton Chekhov (1955)Dashiell Hammett: The Big Knockover (1966)The Dashiell Hammett Story Omnibus. Ed. Lillian Hellman. London: Cassell & Co. Ltd., 1966.

Secondary:

Rollyson, Carl. Lillian Hellman: Her Legend and Her Legacy. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1988.

•

Dashiell Hammett (1935)

Dashiell Hammett (1935)Samuel Dashiell Hammett

(1894–1961)

Novels:

Red Harvest (1929)The Dain Curse (1929)The Maltese Falcon (1930)The Glass Key (1931)The Thin Man (1934)The Dashiell Hammett Omnibus (1950) [DHO]Red HarvestDead Yellow WomenThe Dain CurseThe Golden HorseshoeThe Maltese FalconHouse DickThe Glass KeyWho Killed Bob Teal?The Thin Man The Dashiell Hammett Omnibus: Red Harvest / The Dain Curse / The Maltese Falcon / TheGlass Key / The Thin Man & Four Short Stories. A Crime Connnoisseur Book. London: Cassell & Co. Ltd., 1950. Complete Novels. Ed. Steven Marcus (Library of America, 1999)Complete Novels: Red Harvest; The Dain Curse; The Maltese Falcon; The Glass Key; The Thin Man. Ed. Steven Marcus. The Library of America, 110. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 1999.

Short Stories:

The Big Knockover. Ed. Lillian Hellman (1966) [BK]The Gutting of CouffignalFly PaperThe Scorched FaceThis King BusinessThe Gatewood CaperDead Yellow WomenCorkscrewTulipThe Big Knock-Over$106,000 Blood Money The Dashiell Hammett Story Omnibus [aka "The Big Knockover"]. Ed. Lillian Hellman. London: Cassell & Co. Ltd., 1966. The Continental Op. Ed. Steven Marcus (1974) [CO]The Tenth ClewThe Golden HorseshoeThe House in Turk StreetThe Girl with the Silver EyesThe Whosis KidThe Main DeathThe Farewell Murder The Continental Op. Ed. Steven Marcus. 1974. Picador. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1977. Nightmare Town (1999) [NT]Crime Stories and Other Writings. Ed. Steven Marcus. (Library of America, 2001) [CS]Crime Stories:Arson PlusSlippery FingersCrooked SoulsThe Tenth ClewZigzags of TreacheryThe House in Turk StreetThe Girl with the Silver EyesWomen, Politics and MurderThe Golden HorseshoeNightmare TownThe Whosis KidThe Scorched FaceDead Yellow WomenThe Gutting of CouffignalThe Assistant MurdererCreeping SiameseThe Big Knock-Over$106,000 Blood MoneyThe Main DeathThis King BusinessFly PaperThe Farewell MurderWoman in the DarkTwo Sharp KnivesOther Writings:The Thin Man: An Early TypescriptFrom the Memoirs of a Private DetectiveSuggestions to Detective Story WritersCrime Stories and Other Writings. Ed. Steven Marcus. The Library of America, 125. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 2001. Lost Stories. Introduction by Joe Gores (2005) [LS]The Hunter and Other Stories. Ed. Richard Layman & Julie M. Rivett (2013) [Hunter]The Big Book of the Continental Op (2017) [BCO]

Stories:

The Parthian Shot (1922) [LS][as Daghull Hammett] Immortality (1922) [LS][as Peter Collinson] The Barber and His Wife (1922) [LS][as Peter Collinson] The Road Home (1922) [LS]The Master Mind (1923) [LS][as Peter Collinson] The Sardonic Star of Tom Doody [aka "Wages of Crime"] (1923) [LS][as Peter Collinson] The Vicious Circle [aka “The Man Who Stood in the Way”] (1923) [Woman in the Dark (1951)]The Joke on Eloise Morey (1923) [LS]Holiday (1923) [LS][as Mary Jane Hammett] The Crusader (1923) [LS][as Peter Collinson] Arson Plus (1923) [CS] [BCO]The Dimple [aka "In the Morgue"] (1923) [LS]Crooked Souls [aka "The Gatewood Caper"] (1923) [BK] [CS] [BCO][as Peter Collinson] Slippery Fingers (1923) [CS] [BCO]The Green Elephant (1923) [LS]It [aka "The Black Hat That Wasn't There"] (1923) [BCO]The Second-Story Angel (1923) [NT][as Peter Collinson] Laughing Masks [aka "When Luck's Running Good"] (1923) [LS]Bodies Piled Up [aka "House Dick"] (1923) [DHO] [BCO][as Peter Collinson] Itchy [aka "Itchy the Debonair"] (1924) [LS]The Tenth Clew [aka "The Tenth Clue"] (1924) [CO] [CS] [BCO]The Man Who Killed Dan Odams (1924) [NT]Night Shots (1924) [BCO]The New Racket [aka "The Judge Laughed Last"] (1924) [The Adventures of Sam Spade (1944)]Esther Entertains (1924) [LS]Afraid of a Gun (1924) [NT]Zigzags of Treachery (1924) [CS] [BCO]One Hour (1924) [BCO]The House in Turk Street (1924) [CO] [CS] [BCO]The Girl with the Silver Eyes (1924) [CO] [CS] [BCO]Women, Politics and Murder [aka "Death on Pine Street" / "A Tale of Two Women"] (1924) [CS] [BCO]The Golden Horseshoe (1924) [CO] [CS] [DHO] [BCO]Who Killed Bob Teal? (1924) [DHO] [BCO]Nightmare Town (1924) [CS]Mike, Alec or Rufus? [aka "Tom, Dick or Harry?"] (1925) [BCO]Another Perfect Crime (1925) [LS]The Whosis Kid (1925) [CO] [CS] [BCO] Ber-Bulu [aka "The Hairy One"] (1925) [LS]The Scorched Face (1925) [BK] [CS] [BCO]Corkscrew (1925) [BK] [BCO]Ruffian's Wife (1925) [NT]Dead Yellow Women (1925) [DHO] [BK] [CS] [BCO]The Glass That Laughed (1925) [Electric Literature (2017)]The Gutting of Couffignal (1925) [BK] [CS] [BCO]The Nails in Mr. Cayterer (1926) [The Creeping Siamese (1950)]The Assistant Murderer [aka "First Aide to Murder"] (1926) [CS]Creeping Siamese (1926) [CS] [BCO]The Advertising Man Writes a Love Letter (1927) [LS]The Big Knock-Over (1927) [BK] [CS] [BCO]$106,000 Blood Money (1927) [BK] [CS] [BCO]The Main Death (1927) [CO] [CS] [BCO]The Cleansing of Poisonville [reworked into Red Harvest] (1927) [BCO]Crime Wanted—Male or Female [reworked into Red Harvest] (1927) [BCO]This King Business (1928) [BK] [CS] [BCO]Dynamite [reworked into Red Harvest] (1928) [BCO]The 19th Murder [reworked into Red Harvest] (1928) [BCO]Black Lives [reworked into The Dain Curse] (1928) [BCO]The Hollow Temple [reworked into The Dain Curse] (1928) [BCO]Black Honeymoon [reworked into The Dain Curse] (1929) [BCO]Black Riddle [reworked into The Dain Curse] (1929) [BCO]Fly Paper (1929) [BK] [CS] [BCO][as Samuel Dashiell] The Diamond Wager (1929) [Hunter]The Farewell Murder (1930) [CO] [CS] [BCO]The Glass Key [reworked into The Glass Key] (1930)The Cyclone Shot [reworked into The Glass Key] (1930)Dagger Point [reworked into The Glass Key] (1930)The Shattered Key [reworked into The Glass Key] (1930)Death and Company (1930) [BCO]On the Way (1932) [Hunter]A Man Called Spade (1932) [NT]Too Many Have Lived (1932) [NT]They Can Only Hang You Once [aka ] (1932) [NT]Woman in the Dark [3 parts] (1933) [CS]Night Shade (1933) [LS]Albert Pastor at Home (1933) [Nightmare Town (1948)]Two Sharp Knives [aka "To a Sharp Knife"] (1934) [CS]His Brother's Keeper (1934) [NT]This Little Pig (1934) [LS]The Thin Man and the Flack (1941) [LS] Tulip [unfinished novel] [BK]A Man Named Thin [aka "The Figure of Incongruity"] (1961) [NT]Seven Pages (2005) [Hunter]Faith (2007) [Hunter]So I Shot Him [aka "The Cure"] (2011 [Hunter]The Hunter (2013) [Hunter]The Sign of the Potent Pills (2013) [Hunter]Action and the Quiz Kid (2013) [Hunter]Fragments of Justice (2013) [Hunter]A Throne for the Worm (2013) [Hunter]Magic (2013) [Hunter]An Inch and a Half of Glory (2013) [Hunter]Nelson Redline (2013) [Hunter]Monk and Johnny Fox (2013) [Hunter]The Breech-Born (2013) [Hunter]The Lovely Strangers (2013) [Hunter]Week-End (2013) [Hunter]A Knife Will Cut for Anybody [Unfinished] (2013)[Hunter]The Secret Emperor [Unfinished] (2013)[Hunter]Time to Die [Unfinished] (2013) [Hunter]September 20, 1938 [Unfinished] (2013)[Hunter]Three Dimes [Unfinished] (2017) [BCO]The Man Who Loved Ugly Women (n.d.) [LS]

Screenplays:

Watch on the Rhine [based on Lillian Hellman's play] (1943)

Screen Stories:

The Kiss-Off [City Streets] (1931) [Hunter]Devil's Playground [unproduced] [Hunter]On the Make [Mister Dynamite] (1935) [Hunter]After the Thin Man (1936) [Hunter]Another Thin Man (1939) [Hunter]Sequel to the Thin Man [unproduced] [Hunter]

Non-fiction:

The Great Lovers (The Smart Set, 1922)From the Memoirs of a Private Detective (The Smart Set, 1923)In Defence of the Sex Story (The Writer's Digest, 1924)Three Favorites (Black Mask, 1924, Short autobiographies of Francis James, Dashiell Hammett and C. J. Daly.)Vamping Sampson (The Editor, 1925)The Advertisement IS Literature (Western Advertising, 1926)Advertising Art Isn't Art —- It's Advertising (Western Advertising, 1927)Have You Tried Meiosis? (Western Advertising, 1928)The Literature of Advertising in 1927 (Western Advertising, 1928)The Editor Knows His Audience (Western Advertising, 1928)[with Robert Colodny] The Battle of the Aleutians. [pamphlet]. Illustrated by Harry Fletcher. Adak, Alaska: Field Force Headquarters, 1944.

Edited:

Creeps by Night: Chills and Thrills (1931)

Comics:

Secret Agent X-9, Book 1. [Daily comic strip]. Illustrated by Alex Raymond (David McKay Publications, 1934)Secret Agent X-9, Book 2. Illustrated by Alex Raymond (David McKay Publications, 1934)Secret Agent X-9. Illustrated by Alex Raymond (Nostalgia Press, NY, 1976)Dashiell Hammett's Secret Agent X-9. Illustrated by Alex Raymond (International Polygonics Ltd, 1983)Secret Agent X-9. Illustrated by Alex Raymond (Kitchen Sink Press, 1990)[with Leslie Charteris] Secret Agent X-9. Illustrated by Alex Raymond (IDW Publishing, 2015)

Film Adaptations:

Roadhouse Nights [adaptation of Red Harvest] (1930)The Maltese Falcon (1931)Woman in the Dark (1934)The Thin Man (1934)The Glass Key (1935)Satan Met a Lady [adaptation of The Maltese Falcon] (1936)After the Thin Man (1936)Another Thin Man (1939)The Maltese Falcon (1941)The Glass Key (1942)No Good Deed [adaptation of "The House in Turk Street"] (2002)

Letters:

The Selected Letters of Dashiell Hammett, 1921-1960. Ed. Richard Layman & Julie M. Rivett. Introduction by Josephine Hammett Marshall. Washington, DC: Counterpoint, 2001.

Secondary:

Johnson, Diane. Dashiell Hammett: A Life. New York: Random House, 1983.

Joan Mellen: Hellman and Hammett (1996)

Joan Mellen: Hellman and Hammett (1996)•

Published on October 17, 2024 13:11

October 12, 2024

The Bounty Mythos

Nordhoff & Hall: The Bounty Trilogy (1982)

Nordhoff & Hall: The Bounty Trilogy (1982)Charles Nordhoff & James Norman Hall: The Bounty Trilogy: Comprising the Three Volumes Mutiny on the Bounty; Men Against the Sea; Pitcairn’s Island. 1932, 1933, 1934, 1936. Illustrated by N. C. Wyeth. 1940. An Atlantic Monthly Press Book. Boston & Toronto: Little, Brown & Company, 1982.

Date: 28th April, 1789. Place: the middle of the Pacific Ocean. The most famous mutiny in history is about to break out.

The storming of the Bastille in Paris would not take place until July 14th of that year, but stormclouds were already looming over the Bourbon monarchy. Or, as William Blake put it in his projected seven-part epic The French Revolution (1791):

The dead brood over Europe, the cloud and vision descends overNor would the rest of the British navy be exempt from the shockwaves of these great events. Less than a decade after the Bounty mutiny, the fleet would endure two of the worst uprisings in their history: at Spithead (April to May 1797) and the Nore (May to June 1797).

chearful France ...

Both of these mutinies involved multiple ships and men. At the Nore, Richard Parker, the self-styled President of the "Floating Republic", made no secret of his admiration for the French Revolution and for its declared principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity - ideas taken straight from Tom Paine's The Rights of Man (1791).

The crew of Bligh's ship, HMS Director, put him ashore - like most of their other commanding officers - during the Nore rebellion. There's no evidence that he was treated more harshly than anyone else on that occasion. It was, nevertheless, the second of three mutinies against his leadership during his long career.

So it's probably fair to say that a spirit of radicalism was beginning to pervade the British navy even before the crew of the Bounty, and their ringleader, Fletcher Christian, were (or so the story goes) seduced by the comforts of "Aphrodite's Island", Tahiti.

Anne Salmond: Aphrodite's Island (2009)

Anne Salmond: Aphrodite's Island (2009)Anne Salmond. Aphrodite's Island: The European Discovery of Tahiti. Viking. Auckland: Penguin Group (NZ), 2009.

Whatever the causes of the Bounty mutiny - whether or not Captain Bligh actually was the foaming, flogging monster of legend, or just a firm-but-fair, by-the-book commander, as various revisionist historians have claimed - it's been written about and dramatised almost continuously since.

The fact that Bligh was yet again deposed as Governor of New South Wales by rebellious officers in 1808 makes him seem, at the very least, somewhat misguided in his methods of governance. Or, to paraphrase Lady Bracknell in The Importance of Being Earnest:

To lose one command, Captain Bligh, may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose three looks like carelessness.In any case, I was happy to find a copy of Charles Nordhoff & James Norman Hall's classic Bounty trilogy in Devonport the other day. I read my father's scruffy paperback copies of the three books many years ago, as a teenager, and they made a deep impression on me.

Nordhoff & Hall: Mutiny on the Bounty (1932)

Nordhoff & Hall: Mutiny on the Bounty (1932)Nordhoff, Charles, & James Norman Hall. Mutiny on the Bounty. 1932. Four Square Books. London: New English Library / Sydney: Horwitz Publications, 1961.

Nordhoff & Hall: Men Against the Sea (1933)

Nordhoff & Hall: Men Against the Sea (1933)Nordhoff, Charles, & James Norman Hall. Men Against the Sea. 1933. Fontana Books. London: Collins, 1956.

Nordhoff & Hall: Pitcairn’s Island (1934)

Nordhoff & Hall: Pitcairn’s Island (1934)Nordhoff, Charles, & James Norman Hall. Pitcairn’s Island. 1934. New York: Pocket Books, 1976. I think it was the last, the one about all the things that went down on Pitcairn after the mutiny, which impressed me most. There was a relentless horror about it which reminds me more than a little of the wreck of the Batavia, 150 years before.

In any case, I thought it might be interesting to list here the main accounts - and dramatisations - of the Bounty mutiny which I've collected over the years. There are quite a few of them, though I'd have to stress that this collection is in no way exhaustive: a complete Bounty bibliography would no doubt stretch to many pages.

•

The Bounty Replica in Hong Kong (1978)

The Bounty Replica in Hong Kong (1978)Books I own are marked in bold:

William Bligh (1754-1817): The Mutiny on Board H.M.S. Bounty (1790)

William Bligh (1754-1817): The Mutiny on Board H.M.S. Bounty (1790)William Bligh. The Mutiny on Board H.M.S. Bounty. 1790. Afterword by Milton Rugoff. A Signet Classic. New York: New American Library, 1961.

It's generally best to get your own version of events out there first. Bligh's account is perhaps more notable for what it doesn't say than what it does. Despite the huge gaps in his story, though, what he chooses to tell us seems to be reasonably accurate.

There the whole matter might have rested if it hadn't been for the rediscovery of Pitcairn island - colonised in 1790 by nine Bounty mutineers, together with eighteen Tahitian men and women - by the American sealing ship Topaz, under Mayhew Folger, in February 1808.

Folger's report, which mentioned the presence there of the last surviving mutineer, John Adams, was forwarded to the Admiralty, together with a more accurate location for the island.

None of this was, however, known to Sir Thomas Staines of the Royal Navy, whose two ships visited Pitcairn on 17 September 1814. As a result, John Adams, now the patriarch of the small community, was pardoned for his part in the mutiny, and the rest of the islanders were left in peace.

•

George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824): The Island (1823)

George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824): The Island (1823)Lord Byron. "The Island". The Poetical Works. Ed. Frederick Page. 1904. Rev. ed. 1945. Oxford Standard Authors. London: Oxford University Press, 1959. 349-66.

Lord Byron's long narrative poem "The Island; or, Christian and His Comrades" is one of the last pieces he wrote before leaving for Greece in July 1823. He died there of fever less than a year later.

His poem has received rather mixed reviews. It lacks the humour and zest of his late masterpiece Don Juan (1819-24), but also fails to rekindle the revolutionary passion of early works such as Childe Harold's Pilgrimage (1812-18).

On the one hand, his completely fictionalised picture of life on the island is clearly inspired by Rousseau's idea of the Noble Savage; on the other hand, his revulsion from politics makes it impossible for him to endorse the radical, levelling ideas of the original mutineers.

His poem seems, in many ways, more inspired by a desire to assert kinship with his seagoing grandfather "Foul-Weather Jack" Byron, who survived a terrifying shipwreck as a young midshipman in the 1740s, and subsequently circumnavigated the globe in the 1760s (a few years before Captain Cook), than by any real sympathy for Christian and his comrades.

•

John Barrow (1764-1848): The Eventful History of H.M.S. Bounty (1831)

John Barrow (1764-1848): The Eventful History of H.M.S. Bounty (1831)Sir John Barrow. The Eventful History of the Mutiny and Piratical Seizure of HMS BOUNTY its Causes and Consequences. 1831. Ed. Captain Stephen W. Roskill. London: The Folio Society, 1976.

This is widely considered to be the classic account of the mutiny and its aftermath. It begins with an account of the island of Tahiti, and concludes with a full discussion of events on Pitcairn. The narrative is based firmly on the surviving documentary record.

Its author, Sir John Barrow, is discussed in detail in the 1998 book Barrow's Boys, by Fergus Fleming. His zeal for exploration in general - particularly Arctic expeditions - was vital in maintaining public interest in the voyages of discovery by such luminaries as Sir John Ross, Sir William Edward Parry, Sir James Clark Ross, and Sir John Franklin. The Barrow Strait in the Canadian Arctic, as well as Point Barrow and the city of Barrow in Alaska are named after him.

Barrow was what would now be called a career civil servant, working for successive administrations as Permanent Secretary to the Admiralty. It was his forty-year incumbency of this post which allowed him to exert such a strong influence on the direction of nineteenth century British exploration. He was not, by most accounts, particularly susceptible to correction: an Establishment man through and through.

•

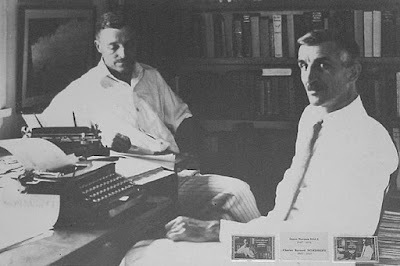

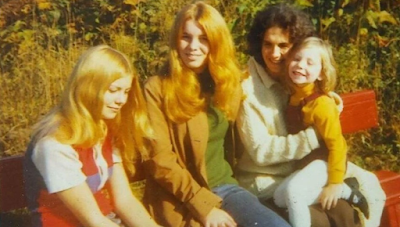

James Norman Hall (1887–1951)

James Norman Hall (1887–1951)& Charles Bernard Nordhoff (1887-1947)

Charles Nordhoff & James Norman Hall: The Bounty Trilogy: Comprising the Three Volumes Mutiny on the Bounty; Men Against the Sea; Pitcairn’s Island. 1932, 1933, 1934, 1936. Illustrated by N. C. Wyeth. 1940. An Atlantic Monthly Press Book. Boston & Toronto: Little, Brown & Company, 1982.

Nordhoff and Hall made friends during the First World War. They were both members of the famous Lafayette Escadrille, and their first collaboration was on a history of the squadron and its wartime exploits.

It was Nordhoff who suggested that the two of them move to Tahiti and work on more books about life in the South Seas. After a few false starts, their first big success came with the novel Mutiny on the Bounty and its two sequels. The Hurricane (1936) is probably the only other one of their novels to strike a nerve with the public.

As with The Hurricane, it was the film adaptation of Mutiny on the Bounty which has kept it in print ever since. Which is a pity, as it's a far better book than one might assume.

The two men's paths diverged in 1936, when Nordhoff left Tahiti. He died, an embittered alcoholic, in California in 1947. James Norman Hall, by contrast, stayed on in Tahiti, with his part-Polynesian wife Sarah (Lala) Winchester. They had two children, Nancy and Conrad, the latter of whom became the Academy-award winning cinematographer of such fims as In Cold Blood (1967), Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), and American Beauty (1999).

•

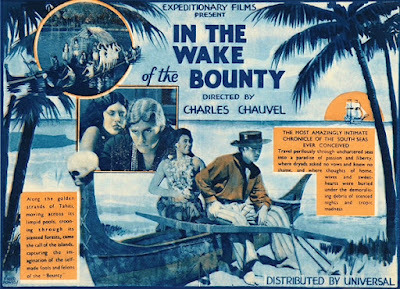

Charles Chauvel (1897-1959): In the Wake of the Bounty (1933)

Charles Chauvel (1897-1959): In the Wake of the Bounty (1933)In the Wake of the Bounty, directed & written by Charles Chauvel; starring Arthur Greenaway, Mayne Lynton, Errol Flynn, Victor Gouriet, & John Warwick (Australia, 1933)

This is the first of four major feature films inspired by the Bounty story. It also marked the screen debut of Tasmanian-born actor Errol Flynn, the first of the bankable Hollywood stars (the others are Clark Gable, Marlon Brando, and Mel Gibson) to have taken on the role of Fletcher Christian. It's important, however, to note - for patriotic reasons if no others - that there was at least one film on the topic before this:I have to confess to not having seen either of these two films. The first remains unavailable, and the second, made in Australia in the early days of sound, is - by all accounts - a fairly stilted affair.

The Mutiny of the Bounty is a 1916 Australian-New Zealand silent film directed by Raymond Longford ... It is the first known cinematic dramatisation of this story and is considered a lost film.

Its one major selling point at the time was the chance to see some documentary-style footage of life on Pitcairn Island, complete with Polynesian dancers and some footage of "an underwater shipwreck, filmed with a glass bottomed boat, which [Chauvel] believed was the Bounty but was probably not."

•

Frank Lloyd (1886-1960): Mutiny on the Bounty (1935)

Frank Lloyd (1886-1960): Mutiny on the Bounty (1935)Mutiny on the Bounty, dir. Frank Lloyd, written by Talbot Jennings, Jules Furthman, Carey Wilson, & John Farrow; based on Mutiny on the Bounty (1932) & Men Against the Sea (1933), by Charles Nordhoff & James Norman Hall; starring Charles Laughton, Clark Gable, Franchot Tone, Movita Castaneda, & Mamo Clark (USA, 1935)

I doubt that it's a picture that anyone can ever erase from their minds: Charles Laughton mopping and mowing and generally biting the scenery as that epitome of all tyrants, Captain Bligh.

How dare this limey mountebank hassle the king of cool, Clark Gable, at the apex of his screen popularity!

If the official line on the mutiny - that it was the work of a few disaffected malcontents, and undertaken against the will of most of the crew - had more or less prevailed up to this point, this film achieved an almost complete paradigm shift.

From now on it was clear that Fletcher Christian was - in spirit if not in fact - an honorary American, whereas Captain Bligh was a true-blue, beef-guzzling Englishman. They might as well have been labelled "Thomas Jefferson" and "King George" in the way they were portrayed.

•

George Mackaness (1882-1968): A Book of the Bounty (1938)

George Mackaness (1882-1968): A Book of the Bounty (1938)George Mackaness, ed. A Book of the 'Bounty' and Selections from Bligh's Writings. 1790, 1792, 1794. Everyman's Library, 1950. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd. / New York: E. P. Dutton & Co. Inc., 1938.

The Empire always does its best to strike back, however. The Book of the Bounty is a balanced and judicious attempt to set the record straight by returning to the remaining documentary evidence.

For the most part it's an edition of all of the writings of Captain Bligh on the subject - not just the book listed at the top of this post.

As well as this, Mackaness, an Australian bibliophile and antiquarian, has included transcripts of the original court martial and other useful witness accounts.

But try setting this rather dry-as-dust approach against the brilliance of the 1935 MGM epic - not to mention the powerful and very readable novels that inspired it - and see how far you get!

•

Lewis Milestone (1895-1980): Mutiny on the Bounty (1962)

Lewis Milestone (1895-1980): Mutiny on the Bounty (1962)Mutiny on the Bounty, directed by Lewis Milestone; written by Charles Lederer; based on Mutiny on the Bounty (1932) by Charles Nordhoff & James Norman Hall;starring Marlon Brando; Trevor Howard; Richard Harris; Hugh Griffith; Richard Haydn; Tarita (USA, 1962)

Times change, however, and - probably for as much for copyright reasons as any others - MGM decided that it might be wise to revisit their property 25 years after the first film was released.

In an age of excessively overblown budgets and unprecedented interference by stars, however, Brando's turn to play Christian was an entirely different matter from Errol Flynn's or Clark Gable's.

It was, for a brief time, the most expensive film ever made - until it was supplanted by Liz Taylor's Cleopatra a year or so later. Filming on location is always costly, and the original director, Carol Reed, was forced to leave three months into the shoot. His successor, Lewis Milestone, was unable to communicate with Brando, who was described by a New Yorker critic as playing "Fletcher Christian as a sort of seagoing Hamlet."Indeed, we tend to sympathize with the wicked Captain Bligh, well played by Trevor Howard. No wonder he behaved badly, with that highborn young fop provoking him at every turn!Ouch! The film did do quite well at the box office, and the beauty of the setting was undeniable, but the cost overruns were such that it would have had to do unprecedented business to get out of the red.

•

Richard Hough (1922-1999): Captain Bligh and Mr Christian (1972)

Richard Hough (1922-1999): Captain Bligh and Mr Christian (1972)Richard Hough: Captain Bligh and Mr Christian: The Men and the Mutiny. 1972. London: Arrow Books, 1974.

My father swore by this book. In fact, every time the subject came up, he would ask: "Have you read Captain Bligh and Mr Christian?"

It is, indeed, quite a revolutionary restatement of the original context of this much misunderstood event. The fact of Bligh and Christian's previous friendship, and a host of other details ignored by previous writers, put the mutiny in a completely different light.

Many of these revelations have been revised or expanded on since, but it remains an indispensable source of information on the historiography of the Bounty, as well as the actual events associated with the mutiny.

•

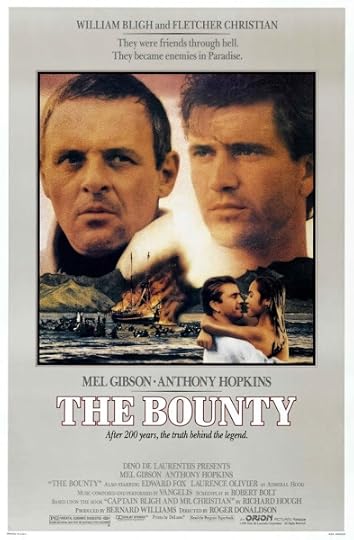

Roger Donaldson (1945- ): The Bounty (1984)

Roger Donaldson (1945- ): The Bounty (1984)The Bounty, directed by Roger Donaldson, written by Robert Bolt; based on Captain Bligh and Mr. Christian (1972), by Richard Hough; starring Mel Gibson, Anthony Hopkins, Edward Fox, Laurence Olivier (UK, 1984)

As an abject fan of David Lean's movies, the news that he was working on a pair of films about the Bounty mutiny during the long hiatus between Ryan's Daughter (1970) and A Passage to India (1984) was pretty thrilling.

A replica Bounty was built, but the mechanics of the project could never be settled, so all that actually resulted from Lean's extensive preparations was the documentary Lost and Found: The Story of Cook's Anchor (NZ, 1979).

Instead, the Bounty film ended up in the blander but probably more business-like hands of Australian / NZ filmmaker Roger Donaldson.

Once again, casting was everything: Mel Gibson had the right New World credentials to play an old-school rebellious Fletcher Christian (a kind of pallid forerunner of his immortal William Wallace). Anthony Hopkins, by contrast, tried to dial back any suggestions of Charles Laughton in favour of a quieter portrayal: a kind of Hannibal-Lecter-in-waiting, one might say.

The script had finally morphed from the Nordhoff-Hall version to Richard Hough's revisionist account, and the results must be said to be richly entertaining - if a little thin in parts. Certainly it's not much of a substitute for what the two David Lean films might have been.

•

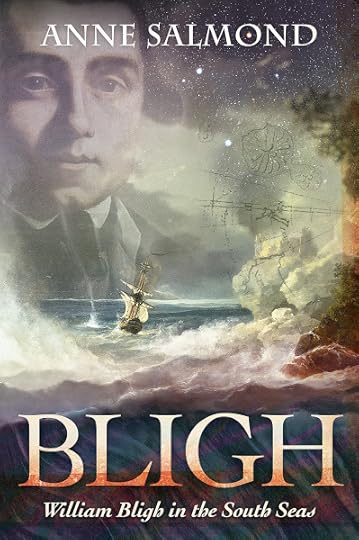

Anne Salmond (1945- ): Bligh (2011)

Anne Salmond (1945- ): Bligh (2011)Anne Salmond. Bligh: William Bligh in the South Seas. Viking. Auckland: Penguin Group (NZ), 2011.

I conclude with the latest major contribution to the Bounty story. Having written about Captain Cook in The Trial of the Cannibal Dog, and Tahiti in Aphrodite's Island, Pacific historian and anthropologist Anne Salmond felt ready to take on the equally formidable subject of Captain Bligh.

If the result isn't quite so satisfactory as her two previous histories, that's perhaps because her methods seem less surprising here than they were in (particularly) the Captain Cook book.

It's hard to know what remains to be said on the subject. It was all a long time ago. It cast a long shadow over everyone involved - and the horrific 2004 sex scandals on Pitcairn Island unfortunately revealed that life there is no more idyllic now than it was in the immediate aftermath of the Mutiny.

•

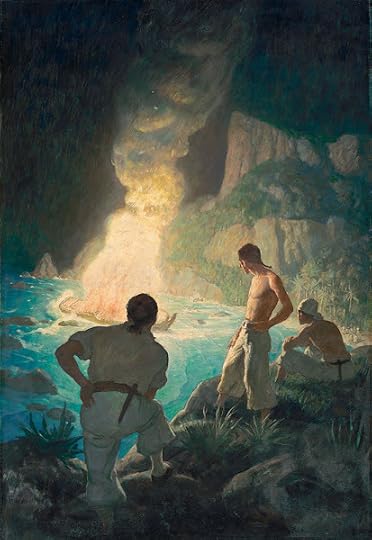

N. C. Wyeth: The Burning of the "Bounty" (1940)

N. C. Wyeth: The Burning of the "Bounty" (1940) N. C. Wyeth (1882-1945): Self-portrait (1940)

N. C. Wyeth (1882-1945): Self-portrait (1940)•

Published on October 12, 2024 14:25

September 23, 2024

HAUNTS Launch / Emma Smith Exhibition - 5-6/10/24

Emma Smith: "The second sun" (The Municipal Gardens, 2024)

Emma Smith: "The second sun" (The Municipal Gardens, 2024)[images courtesy of the artist]

Bronwyn Lloyd will be hosting an exhibition

of recent paintings

by Emma Smith

at 6 Hastings Road

Mairangi Bay, Auckland

Saturday-Sunday 5-6 October

from 11am-4pm

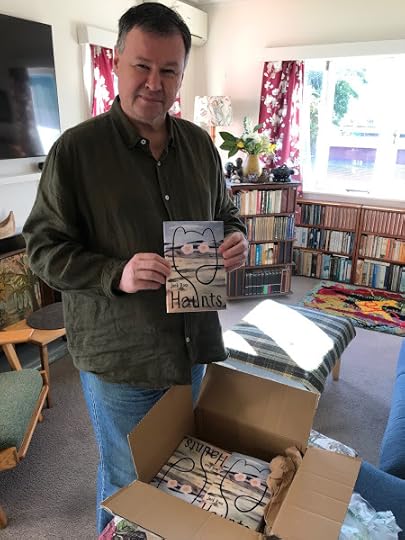

Jack Ross's new collection of stories

Haunts (Lasavia Publishing)

will be launched on the Saturday at 2pm

$30 cash or bank deposit (no EFTPOS)

ALL WELCOME

Refreshments provided

updates on Instagram: @lloyd.bronwyn

Emma Smith: "Living with caves" (The Municipal Gardens, 2024)

Emma Smith: "Living with caves" (The Municipal Gardens, 2024)•

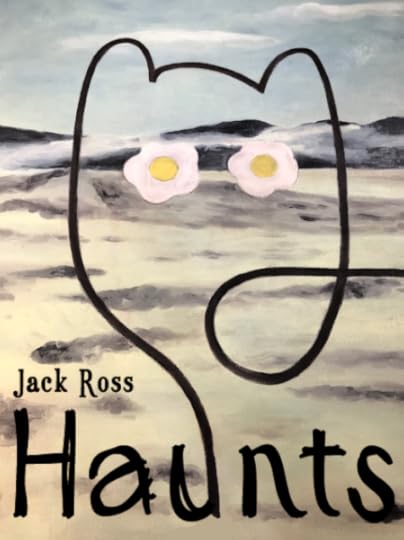

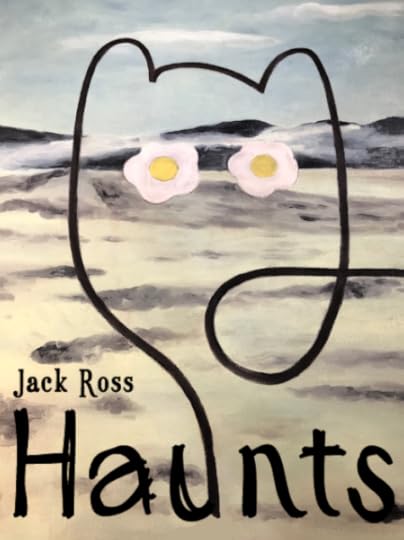

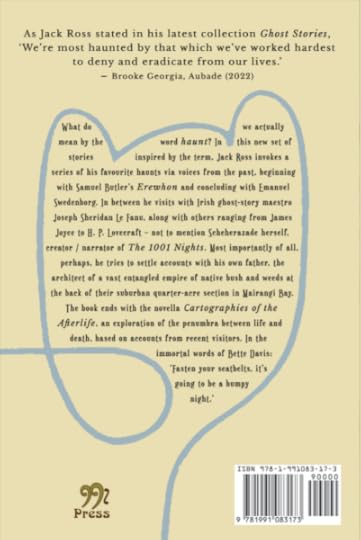

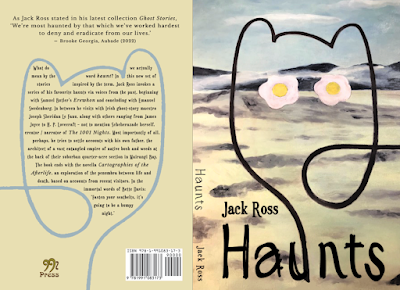

Haunts (Lasavia Publishing, 2024)

Haunts (Lasavia Publishing, 2024)Image: Graham Fletcher (by courtesy of the artist) / Design: Daniela Gast

Back cover blurb:What do we actually mean by the word haunt? In this new set of stories inspired by the term, Jack Ross invokes a series of his favourite haunts via voices from the past, beginning with Samuel Butler’s Erewhon and concluding with Emanuel Swedenborg.

In between he visits with Irish ghost-story maestro Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, along with others ranging from James Joyce to H. P. Lovecraft – not to mention Scheherazade herself, creator / narrator of The 1001 Nights.

Most importantly of all, perhaps, he tries to settle accounts with his own father, the architect of a vast entangled empire of native bush and weeds at the back of their suburban quarter-acre section in Mairangi Bay.

The book ends with the novella Cartographies of the Afterlife, an exploration of the penumbra between life and death, based on accounts from recent visitors.

In the immortal words of Bette Davis: ‘Fasten your seatbelts, it's going to be a bumpy night.’

Jack Ross is the author of six poetry collections, four novels, and four books of short fiction. His previous collection, Ghost Stories (Lasavia, 2019), has been prescribed for writing courses at three local universities. He’s also edited numerous books, anthologies, and literary journals, including (most recently) Mike Johnson’s Selected Poems (2023).

•

Emma Smith: "The second to last" (The Municipal Gardens, 2024)

Emma Smith: "The second to last" (The Municipal Gardens, 2024)

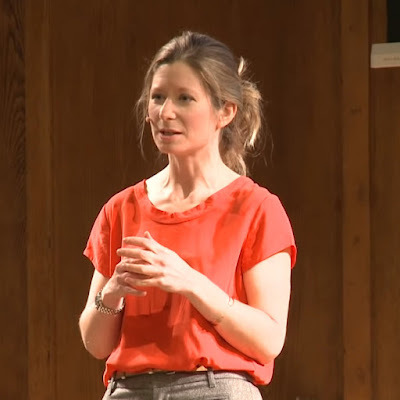

Artist's statement:'Years ago, I lived in a downstairs flat with wide windows that let the night right into the room. There were white datura flowers with pink throats on the fence line. They hummed at dusk. For a long time I tried to paint them as they seemed utterly their own thing. The blooms became sails, became tents, ripped tarps, ropes whipping, planes noses, thick smoke, drones, white flags, stadium lights, search lights, anxious lanterns, distant fires, phosphorescence from below. These shapes still resist a final form and so too do the conditions about them. They are in scorched fields, floating in the dead air of space and falling in fiery plumes.’

Emma Smith was born in Tāmaki Makaurau, Aotearoa/ New Zealand in 1975. Smith currently teaches Contemporary Arts at Unitec Institute of Technology, Auckland. Further information can be found at her website https://emmasmithtingrew.wordpress.com/.

•

Published on September 23, 2024 12:10

September 10, 2024

6X10 Poetry Event, Avondale 28/9/24 @ 7 for 7.30 pm

Whau Arts Festival (21 September - 3 October 2020)

Whau Arts Festival (21 September - 3 October 2020)•

Whau Arts Festival

6X10 Poetry Event

All Goods Community Arts Space

99 Rosebank Road, Avondale

(Behind the Public Library)

MC: Bronwyn Bent

Whau The People

Festival Organiser

Janet Charman

Stu Bagby

Anne Kennedy

Elizabeth Morton

Jack Ross

Leilani Tamu

Saturday September 28 @7 for 7.30 pm

•

Janet Charman

Janet Charman Stu Bagby

Stu Bagby Anne Kennedy

Anne Kennedy Elizabeth Morton

Elizabeth Morton Jack Ross

Jack Ross Leilani Tamu

Leilani Tamu•

All Goods Community Arts Space (Avondale)

All Goods Community Arts Space (Avondale)

•

Published on September 10, 2024 14:36

August 20, 2024

Byzantium

San Vitale, Ravenna: The Emperor Justinian and his Court (c. 547 CE)

San Vitale, Ravenna: The Emperor Justinian and his Court (c. 547 CE)

The unpurged images of day recede;

The Emperor's drunken soldiery are abed;

Night resonance recedes, night-walkers' song

After great cathedral gong;

A starlit or a moonlit dome disdains

All that man is,

All mere complexities,

The fury and the mire of human veins.

- W. B. Yeats, "Byzantium" (1932)

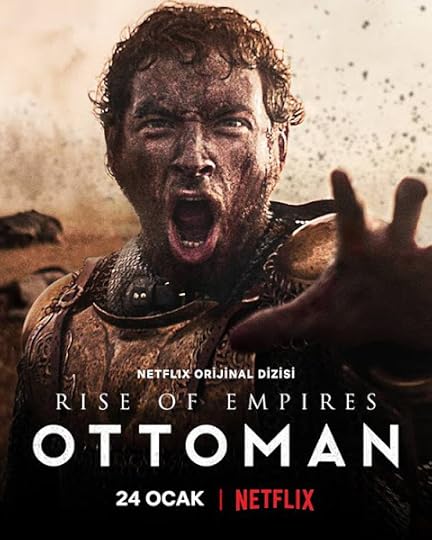

Rise of Empires: Ottoman: The Fall of Constantinople (2020)

Rise of Empires: Ottoman: The Fall of Constantinople (2020)Every now and then you run across a genuinely exciting documentary series on Netflix. One such was " Age of Samurai: Battle for Japan " (2021), a dramatic and informative - albeit blood-soaked - account of the unification of Japan by various warring daimyō (or clan-lords) over the period from 1551 to 1616.

Another was " Rise of Empires: Ottoman ." The first series of this Turkish docudrama told the story of the siege and fall of Constantinople in 1453. The second - even more gripping, if somewhat gruesome - instalment of six episodes outlined the bloody conflict between Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror and his childhood companion Vlad the Impaler, culminating in the 1462 Ottoman invasion of Wallachia.

If you want to know who a bit more about Vlad than the fact that he was the original for Bram Stoker's Count Dracula, this is the place to go. Trigger Alert: if anything, he was even more terrifying in the flesh than in fiction ...

Steven Runciman: The Fall of Constantinople 1453 (1965)

Steven Runciman: The Fall of Constantinople 1453 (1965)Steven Runciman. The Fall of Constantinople 1453. 1965. Cambridge University Press. London: Readers Union Ltd., 1966.The other day I picked up a copy of Steven Runciman's classic account of the siege, The Fall of Constantinople. Sir Steven Runciman (1903-2000), one of the strangest people ever to adorn the profession of history, specialised in the subject of the Eastern Roman empire before and after the era of the Crusades, as you'll discover if you look into the pages of his biography, Outlandish Knight:

Minoo Dinshaw: Outlandish Knight (2017)

Minoo Dinshaw: Outlandish Knight (2017)Minoo Dinshaw. Outlandish Knight: The Byzantine Life of Steven Runciman. 2016. Penguin Books. London: Penguin Random House UK, 2017.His magnum opus, the three-volume History of the Crusades (1951-54), remains the most elegant and lapidary account of the period despite the seventy years that have passed since its appearance.

Steven Runciman: The History of the Crusades (3 vols: 1951-54)

Steven Runciman: The History of the Crusades (3 vols: 1951-54)Steven Runciman. A History of the Crusades. 3 vols. 1951-54. Peregrine Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1965.The First Crusade and the Foundation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem (1951)The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187 (1952)The Kingdom of Acre and the Later Crusades (1954)Admittedly, it has its rivals. Notably, a spirited single-volume account of the first three Crusades by the almost equally eccentric and glamorous Russian-French novelist-historian Zoë Oldenbourg.

Zoë Oldenbourg (1916–2002)

Zoë Oldenbourg (1916–2002)Zoë Oldenbourg. The Crusades. 1965. Trans. Anne Carter. Pantheon Books. New York: Random House, Inc., 1966.The question remains: what is it about Byzantium? Why does it arouse such intense passions in people even now, nearly six centuries after its fall?

I suppose it might be because it still remains a bit of an unknown quantity for most readers. Rightly or wrongly, we all have some kind of mental image of the Romans and their Empire (slaves, togas, the forum, the legions, SPQR).

We also have certain select vignettes of the Ancient Greeks: Socrates and Plato arguing in the agora at Athens, swift Greek triremes defeating the Persian fleet at Salamis - even, perhaps, the last stand of the 300 at Thermopylae ...

Or perhaps you prefer Lord Byron?

Tell them in Sparta, passer-by

That here, obedient to their will, we lie.

- Simonides of Ceos

The mountains look on Marathon —

And Marathon looks on the sea;

And musing there an hour alone,

I dream’d that Greece might still be free;

For standing on the Persians’ grave,

I could not deem myself a slave.

- "The Isles of Greece"

Joshua Reynolds: Edward Gibbon (1737-1794)

Joshua Reynolds: Edward Gibbon (1737-1794)Edward Gibbon. The History of the Decline & Fall of the Roman Empire. 1776-88. Ed. Betty Radice & Felipé Fernández-Armesto. 8 vols. London: Folio Society, 1983-90.The Turn of the Tide (1983)Constantine and the Roman Empire (1984)The Revival and Collapse of Paganism (1985)The End of the Western Empire (1986)Justinian and the Roman Law (1987)Mohammed and the Rise of the Arabs (1988)The Normans in Italy and the Crusades (1989)The Fall of Constantinople and the Papacy in Rome (1990)But what about Constantinople and the Byzantine Empire? It doesn't help that the most celebrated historian to have written on the subject, Edward Gibbon, had an intense prejudice against the Byzantines, and seized every possible chance to disparage them in his epic, immensely influential history of the long decline of Rome and its empire.

Nor has anything comparable been written in their defence. W. B. Yeats adored them, of course. I quoted above from his great poem "Byzantium", but there's also the earlier "Sailing to Byzantium" (1927) to consider:

Once out of nature I shall never take

My bodily form from any natural thing,

But such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make

Of hammered gold and gold enamelling

To keep a drowsy Emperor awake;

Or set upon a golden bough to sing

To lords and ladies of Byzantium

Of what is past, or passing, or to come.

Lady Ottoline Morrell: Yeats at Garsington (1930)

Lady Ottoline Morrell: Yeats at Garsington (1930)[l-to-r: Walter de la Mare, Georgie Yeats, W. B. Yeats, unknown]

Yeats was, admittedly, a bit of a weirdo. He spent much of his youth studying magic with the self-appointed Magi of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, but it was the spirit messages he received at a series of séances with his newly married wife Georgie Hyde-Lees on their honeymoon which inspired him to construct a whole theory of history based on repeating cycles (or "gyres").

This led him to the conclusion that medieval Byzantium was the apex of all human cultures, and - presumably - to his (alleged) desire to spend eternity as a golden clockwork bird on a tree-branch.

These ideas also led him to write great, resonant poems, such as "The Second Coming" ("what rough beast, its hour come round at last, / Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?"). Beyond that, though, it's hard to say to what degree he actually believed in his theories, despite the immense detail devoted to the subject in his prose work A Vision (1925 / 1937).

Clara Molden: John Julius Norwich (1929-2018)

Clara Molden: John Julius Norwich (1929-2018)John Julius Norwich. A History of Byzantium. 3 vols. 1988-1995. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1990-1996.The Early Centuries (1988)The Apogee (1991)The Decline and Fall (1995)It wasn't, in fact, until the last decades of the twentieth century that Byzantium received anything like the historical treatment it deserved. Popular historian John Julius Norwich decided to bite the bullet and try to produce a three-volume history to stand alongside Runciman's earlier work on the Crusades.

Did it redress the balance? Not really, no. Norwich is no Runciman. But he's a very accessible writer, who's written illuminating books about Venice, the Norman conquest of Sicily, and a variety of other Mediterranean events and personages. His history of Byzantium (also available in abridged form in a single volume) is a fine addition to the bibliography of the subject.

Robert Graves: Count Belisarius (1938)

Robert Graves: Count Belisarius (1938)Robert Graves. Count Belisarius. 1938. London: Cassell & Co. Ltd., 1962.Which is, of course, immense. In fact, so many books touch on various aspects of Imperial Byzantium's thousand-year history, that it can be hard to know where to begin.

If in doubt, start off with an historical novel can be good advice on such occasions. After the immense success of I, Claudius (1934) and Claudius the God (1935), maverick English poet Robert Graves attempted to repeat the trick with a book about the great Byzantine general Belisarius (500–565).

Just as the Claudius books were largely based on the surviving writings of Roman historians Suetonius and Tacitus, so this new one was inspired by Procopius's History of Justinian's Wars and Secret History.

Procopius: The Secret History (1966)

Procopius: The Secret History (1966)Procopius. Works. Trans. H. B. Dewing, with Glanville Downey. 7 vols. 1914-1940. Loeb Classics. London: William Heinemann / Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1968, 1969, 1971, 1978 & 1979.History of the Wars, Books I & II. Trans. H. B. Dewing. 1914 (1979)History of the Wars, Books III & IV. Trans. H. B. Dewing. 1916 (1979)History of the Wars, Books V & VI. Trans. H. B. Dewing. 1919 (1968)History of the Wars, Books VI.16-VII.35. Trans. H. B. Dewing. 1924 (1979)History of the Wars, Books VII.36-VIII. Trans. H. B. Dewing. 1928 (1978)The Anecdota or Secret History. Trans. H. B. Dewing. 1935 (1969)Buildings / General Index to Procopius. Trans. H. B. Dewing, with Glanville Downey. 1940 (1971)Procopius is unique among Classical historians in that as well as writing a long, tediously official history of Justinian's wars in Persia and Italy, he also left behind a scurrilous volume of scandalous gossip about the Emperor Justinian and his wife Theodora - allegedly a circus performer and even prostitute before she became an Empress - the Secret History.

Graves takes full advantage of this material, and compiles a spirited yarn about the virtuous Belisarius, betrayed by his own wife Antonina as well as the corrupt Imperial couple who employed him to clean up their mistakes for so long.

Is Procopius's backstairs gossip all true? Who knows? Perhaps not the stuff about Justinian transforming into a hairy demon when he thought he was unobserved - but a lot of the rest sounds uncomfortably plausible. However, some contemporary historians have advanced a rather different reading of the Secret History:

... it has been argued that Procopius prepared the Secret History as an exaggerated document out of fear that a conspiracy might overthrow Justinian's regime, which — as a kind of court historian — might be reckoned to include him. The unpublished manuscript would then have been a kind of insurance, which could be offered to the new ruler as a way to avoid execution or exile after the coup. If this hypothesis were correct, the Secret History would not be proof that Procopius hated Justinian or Theodora. - Wikipedia: ProcopiusSpeaking for myself, that sounds to me like one of those perverse hypotheses historians like dreaming up to avoid the obvious conclusions already sanctioned by other scholars - a bit like the one about how the poet Ovid just pretended to have been banished to the Black Sea by the Emperor Augustus, but instead just sat in his house at Rome and wrote poems about being in exile.

In other words, given the tone of his invective, the chances that the author of the Secret History actually admired Justinian and Theodora are about as likely - in my humble opinion - as the possibility that Q-Anon was actually right about Pizzagate, and Donald Trump really was divinely ordained to combat demon worship in Washington D.C.

John Masefield: Basilissa: A Tale of the Empress Theodora (1938)

John Masefield: Basilissa: A Tale of the Empress Theodora (1938)John Masefield. Byzantine Trilogy. London: William Heinemann, Ltd., 1940-47.Basilissa: A Tale of the Empress Theodora (1940)Conquer: A Tale of the Nika Rebellion in Byzantium (1941)Badon Parchments (1947)Mind you, Justinian and Theodora do have their admirers. British Poet Laureate John Masefield, in his two historical novels Basilissa and Conquer, portrayed the Empress Theodora as a kind of distant cousin of Wallis Simpson - a potential breath of fresh air for a moribund court and royal family. She can do little wrong in his eyes (though Justinian does come across as a bit of a wimp).

The final volume in his trilogy (and the last novel he ever wrote), Badon Parchments, presents the story of King Arthur's victory over the Saxons at Mons Badonicus through the eyes of some official Byzantine observers, sent by the authorities of the Eastern Empire to observe, and - if possible - encourage this new manifestation of Roman fighting spirit.

William Rosen: Justinian's Flea (2006)

William Rosen: Justinian's Flea (2006)William Rosen. Justinian’s Flea: Plague, Empire and The Birth of Europe. 2006. London: Pimlico, 2008.A no less absorbing, and considerably more accurate picture of the Byzantine Empire at its apogee under Justinian, is given by William Rosen's account of one of the very worst outbreaks of plague ever to afflict the human race - and its possible influence on both the rise of Islam and of an independent Europe.

Isaac Asimov: Constantinople: The Forgotten Empire (1970)

Isaac Asimov: Constantinople: The Forgotten Empire (1970)Isaac Asimov. Constantinople: The Forgotten Empire. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1970.However, if that sounds like a bit of a fun bypass, you could do worse than check out either SF writer Isaac Asimov's focussed and informative short history of the "Forgotten Empire", or - for a more recent view - Aussie Radio personality Richard Fidler's travel book Ghost Empire.

Fidler attempts to recount certain picturesque events from the history of Byzantium in a series of rather stilted dialogues with his young son. It's a surprisingly successful formula, and gives a good basis for further reading - just like its even more beguiling follow-up Saga Land (2017), about the wondrous world of the Icelandic Sagas.

Richard Fidler: Ghost Empire (2016)

Richard Fidler: Ghost Empire (2016)Richard Fidler. Ghost Empire. 2016. ABC Books. Sydney: HarperCollins Publishers Australia Pty Ltd., 2017.

•

David Talbot Rice: Byzantine Art (1968)

David Talbot Rice: Byzantine Art (1968)(1929-2018) (1916–2002) (1903-2000)

Books I own are marked in bold:

John Julius Norwich (1929-2018)

John Julius Norwich (1929-2018)[John Julius Cooper, 2nd Viscount Norwich]

(1929–2018)

[with Reresby Sitwell] Mount Athos (1966)The Normans in the South, 1016–1130 [aka 'The Other Conquest'] (1967)Included in: The Normans in Sicily: The Normans in the South, 1016-1130 & The Kingdom in the Sun, 1130-1194. 1967 & 1970. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1992. Sahara (1968)The Kingdom in the Sun, 1130–1194 (1970)Included in: The Normans in Sicily: The Normans in the South, 1016-1130 & The Kingdom in the Sun, 1130-1194. 1967 & 1970. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1992. Great Architecture of the World (1975)Venice: The Rise to Empire (1977)Included in: A History of Venice. 1977 & 1981. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2003. Venice: The Greatness and Fall (1981)Included in: A History of Venice. 1977 & 1981. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2003. A History of Venice (1982)A History of Venice. 1977 & 1981. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2003. [with Suomi La Valle] Hashish (1984)The Architecture of Southern England (1985)Fifty Years of Glyndebourne (1985)A Taste for Travel (1985)Byzantium: The Early Centuries (1988)Byzantium: The Early Centuries. 1988. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1990. The Normans in Sicily (1992)The Normans in Sicily: The Normans in the South, 1016-1130 & The Kingdom in the Sun, 1130-1194. 1967 & 1970. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1992. Byzantium; vol. 2: The Apogee (1992)Byzantium: The Apogee. 1991. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1993. Byzantium; vol. 3: The Decline and Fall (1995)Byzantium: The Decline and Fall. 1995. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1996. A Short History of Byzantium (1997)[with Quentin Blake] The Twelve Days of Christmas (1998)Shakespeare's Kings: the Great Plays and the History of England in the Middle Ages: 1337–1485 (2000)Paradise of Cities, Venice and its Nineteenth-century Visitors (2003)Paradise of Cities: Nineteenth-century Venice Seen through Foreign Eyes. London: Viking, 2003. The Middle Sea: A History of the Mediterranean (2006)The Middle Sea: A History of the Mediterranean. 2006. London: Vintage Books, 2007. Trying to Please [autobiography] (2008)The Popes: A History [aka 'Absolute Monarchs: A History of the Papacy'] (2011)A History of England in 100 Places: From Stonehenge to the Gherkin (2012)Sicily: An Island at the Crossroads of History (2015)Four Princes: Henry VIII, Francis I, Charles V, Suleiman the Magnificent and the Obsessions that Forged Modern Europe (2016)Four Princes: Henry VIII, Francis I, Charles V, Suleiman the Magnificent and the Obsessions that Forged Modern Europe. London: John Murray (Publishers), 2016. France: A History: from Gaul to de Gaulle [aka 'A History of France'] (2018)

Edited:

Christmas Crackers: Being Ten Commonplace Selections 1970-1979 (1980)Britain's Heritage (1983)The Italian World: History, Art and the Genius of a People (1983)More Christmas Crackers, 1980-1989 (1990)Oxford Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Art (1990)Venice: a Traveller's Companion (1990)Still More Christmas Crackers, 1990-1999 (2000)Treasures of Britain (2002)The Duff Cooper Diaries (2006)The Great Cities in History (2009)The Big Bang: Christmas Crackers, 2000–2009 (2010)Darling Monster: The Letters of Lady Diana Cooper to Her Son John Julius Norwich (2013)[with Quentin Blake] The Illustrated Christmas Cracker (2013)Cities That Shaped the Ancient World (2014)A Christmas Cracker: being a Commonplace Selection (2018)

•

Zoë Oldenbourg

Zoë Oldenbourg[Зоя Сергеевна Ольденбург]

(1916–2002)

Fiction:

Argile et cendres (1946)The World is Not Enough. 1946. Trans. Willard A. Trask. 1948. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1964. La Pierre angulaire (1953)The Cornerstone. 1953. Trans. Edward Hyams. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1954. Réveillés de la vie (1956)The Awakened. Trans. Edward Hyams (1957) Les Irréductibles (1958)The Chains of Love. 1958. Trans. Michael Bullock. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1959. Les Brûlés (1960)Destiny of Fire. 1960. Trans. Peter Green. 1961. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969. Les Cités charnelles, ou L'Histoire de Roger de Montbrun (1961)Cities of the Flesh, or The Story of Roger de Montbrun. Trans. Anne Carter (1962) La Joie des pauvres (1970)The Heirs of the Kingdom. 1970. Trans. Anne Carter. 1971. Fontana Books. London: Wm. Collins., 1974. La Joie-souffrance (1980)Le Procès du rêve (1982)Les Amours égarées (1987)Déguisements [short stories] (1989)

Non-fiction:

Le Bûcher de Montségur, 16 mars 1244 (1959)Massacre at Montségur: A History of the Albigensian Crusade. 1959. Trans. Peter Green. 1961. Phoenix Giant. London: Orion Books Ltd., 1998. Les Croisades (1965)The Crusades. 1965. Trans. Anne Carter. Pantheon Books. New York: Random House, Inc., 1966. Catherine de Russie (1966)Catherine the Great. 1966. Trans. Anne Carter. Preface by Arthur Calder-Marshall. Women Who Made History. Geneva: Heron Books, 1968. Saint Bernard (1970)L'Épopée des cathédrales (1972)Que vous a donc fait Israël ? (1974)Visages d'un autoportrait (1977)Que nous est Hécube ?, ou Un plaidoyer pour l'humain (1984)

Plays:

L'Évêque et la vieille dame, ou La Belle-mère de Peytavi Borsier, pièce en dix tableaux et un prologue (1983)Aliénor, pièce en quatre tableaux (1992)

•

Sir Steven Runciman (1903-2000)

[Sir James Cochran Stevenson Runciman]

(1903-2000)

The Emperor Romanus Lecapenus and His Reign: A Study of Tenth-Century Byzantium (1929)A History of the First Bulgarian Empire (1930)Byzantine Civilization (1933)The Medieval Manichee: A Study of the Christian Dualist Heresy (1947)A History of the Crusades, Volume One (1951)A History of the Crusades. Vol. 1: The First Crusade and the Foundation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. 1951. Peregrine Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1965. A History of the Crusades, Volume Two (1952)A History of the Crusades. Vol. 2: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. 1952. Peregrine Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1965. A History of the Crusades, Volume Three (1954)A History of the Crusades. Vol. 3: The Kingdom of Acre and the Later Crusades. 1954. Peregrine Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1965. The Eastern Schism (1955)The Eastern Schism: a Study of the Papacy and the Eastern Churches during the 11th and 12th Centuries. 1955. Panther History. London: Panther, 1970. The Sicilian Vespers (1958)The Sicilian Vespers: A History of the Mediterranean World in the Later Thirteenth Century. 1958. A Pelican Book. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1960. The White Rajahs: A History of Sarawak from 1841 to 1946 (1960)The Fall of Constantinople 1453 (1965)The Fall of Constantinople 1453. 1965. Cambridge University Press. London: Readers Union Ltd., 1966. The Great Church in Captivity: A Study of the Patriarchate of Constantinople from the Eve of the Turkish Conquest to the Greek War of Independence (1968)The Last Byzantine Renaissance (1970)Orthodox Churches and the Secular State (1971)Byzantine Style and Civilization (1975)The Byzantine Theocracy: The Weil Lectures, Cincinnati (1977)Mistra: Byzantine Capital of the Peloponnese (1980)The First Crusade (1980)A Traveller's Alphabet: Partial Memoirs (1991) ISBN 9780500015049

Secondary:

Dinshaw, Minoo. Outlandish Knight: The Byzantine Life of Steven Runciman. 2016. Penguin Books. London: Penguin Random House UK, 2017.

•

Anna Komnene (1083-1153 CE)

Anna Komnene (1083-1153 CE)Anna Komnēnē [Comnena] (1083–1153)

The Alexiad. Trans. E. R. A. Sewter. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969.

Procopius of Caesarea (c.500–c.565)

Works. Trans. H. B. Dewing, with Glanville Downey. 7 vols. 1914-1940. Loeb Classics. London: William Heinemann / Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1968, 1969, 1971, 1978 & 1979.History of the Wars, Books I & II. Trans. H. B. Dewing. 1914 (1979)History of the Wars, Books III & IV. Trans. H. B. Dewing. 1916 (1979)History of the Wars, Books V & VI. Trans. H. B. Dewing. 1919 (1968)History of the Wars, Books VI.16-VII.35. Trans. H. B. Dewing. 1924 (1979)History of the Wars, Books VII.36-VIII. Trans. H. B. Dewing. 1928 (1978)The Anecdota or Secret History. Trans. H. B. Dewing. 1935 (1969)Buildings / General Index to Procopius. Trans. H. B. Dewing, with Glanville Downey. 1940 (1971)The Secret History. Trans. G. A. Williamson. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966.The Secret History. c.550 CE. Trans. G. A. Williamson. 1966. Introduction by Philip Ziegler. London: The Folio Society, 1990.

Michael Psellos / Psellus (c.1017/18-c.1078)

Fourteen Byzantine Rulers: The Chronographia of Michael Psellus. Trans. E. R. A. Sewter. 1953. Penguin Classics. 1966. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1979.

•

The Sack of Constantinople by the Crusaders (1204)

The Sack of Constantinople by the Crusaders (1204)Asimov, Isaac. Constantinople: The Forgotten Empire. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1970.Burckhardt, Jacob. The Age of Constantine the Great. 1852. Rev. ed. 1880. Trans. Moses Hadas. 1949. A Vintage Book V-393. New York: Random House, 1967.Byron, Robert. The Station. Athos: Treasures and Men. 1928. Introduction by Christopher Sykes. A Phoenix Press Paperback. London: The Orion Publishing Group Ltd., 2000.Byron, Robert. The Road to Oxiana. 1937. Introduction by Bruce Chatwin. London: Picador, 1981.Dalrymple, William. From the Holy Mountain: A Journey in the Shadow of Byzantium. 1997. Flamingo. London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1998.Fidler, Richard. Ghost Empire. 2016. ABC Books. Sydney: HarperCollins Publishers Australia Pty Ltd., 2017.Gibbon, Edward. The History of the Decline & Fall of the Roman Empire. 1776-88; 1910. Ed. Betty Radice & Felipé Fernández-Armesto. 8 vols. London: Folio Society, 1983-90.The Turn of the Tide. Ed. & with an introduction by Betty Radice (1983)Constantine and the Roman Empire. Ed. & with an introduction by Betty Radice (1984)The Revival and Collapse of Paganism. Ed. & with an introduction by Betty Radice (1985)The End of the Western Empire. Ed. & with an introduction by Betty Radice (1986)Justinian and the Roman Law. Ed. & with an introduction by Felipe Fernández-Armesto (1987)Mohammed and the Rise of the Arabs. Ed. & with an introduction by Felipe Fernández-Armesto (1988)The Normans in Italy and the Crusades. Ed. & with an introduction by Felipe Fernández-Armesto (1989)The Fall of Constantinople and the Papacy in Rome. Ed. & with an introduction by Felipe Fernández-Armesto (1990)Hodgkin, Thomas. The Barbarian Invasions of the Roman Empire. ['Italy and her Invaders,' 1880-1899]. Introduced by Peter Heather. 8 vols. London: The Folio Society, 2000-3.The Visigothic Invasion. 1880. rev. ed. 1892 (2000)The Huns and the Vandals. 1880. rev. ed. 1892 (2000)The Ostrogoths, 476-535. 1885. rev. ed. 1896 (2001)The Imperial Restoration, 535-553. 1885. rev. ed. 1896 (2001)The Lombard Invasion, 553-600. 1895 (2002)The Lombard Kingdom, 600-744. 1895 (2002)The Frankish Invasion, 744-774. 1899 (2003)The Frankish Empire. 1899 (2003)Hallam, Elizabeth, ed. Chronicles of the Crusades: Eye-Witness Accounts of the Wars Between Christianity and Islam. 1989. Godalming, Surrey: CLB International, 1997.Hill, Rosalind, ed. Gesta Francorum et Aliorum Hierosolimitanorum. Nelson’s Medieval Texts. London: Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1962.Joinville & Villehardouin. Chronicles of the Crusades: The Conquest of Constantinople / The Life of Saint Louis. Trans. M. R. B. Shaw. 1963. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969.Rice, David Talbot. Byzantine Art. 1935. A Pelican Book. 1954. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1968.Rosen, William. Justinian’s Flea: Plague, Empire and The Birth of Europe. 2006. London: Pimlico, 2008.Wilmot-Buxton, E. M. The Story of the Crusades. 1910. Told Through the Ages. 1912. London: George G. Harrap & Co. Ltd., 1927.

San Vitale, Ravenna: The Empress Theodora (c.540s CE)

San Vitale, Ravenna: The Empress Theodora (c.540s CE)•

Published on August 20, 2024 15:07

August 8, 2024

The Antikythera Conundrum

Jo Marchant: Decoding the Heavens (2008)

Jo Marchant: Decoding the Heavens (2008)Jo Marchant. Decoding the Heavens: Solving the Mystery of the World's First Computer. 2008. Windmill Books. London: The Random House Group Limited, 2009.The other day I ran across an interesting-looking book in one of the vintage shops I frequent. What's more, it appeared to have been signed by its author, presumably at some book festival or other, which added even further to its cachet.

Of course I'd heard of the Antikythera Mechanism. As I recall, it figured in an old episode of Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World (1980), and since then it's been used as the principal plot point in the latest - hopefully last - Indiana Jones movie:

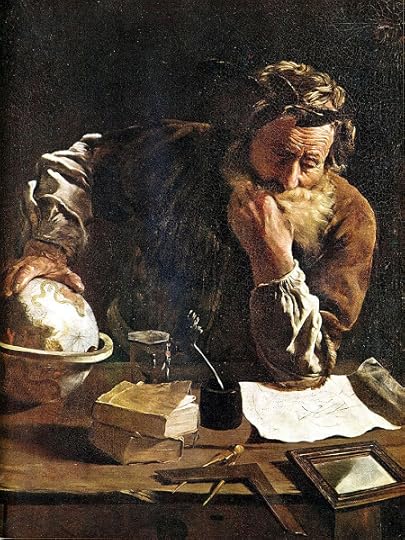

James Mangold, dir.: Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny (2023)

James Mangold, dir.: Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny (2023)The conceit there was that it was an Ancient Greek time machine, built by Archimedes of Syracuse, which some Nazi was trying to use to go back and change the course of history so that the Germans would win the Second World War.

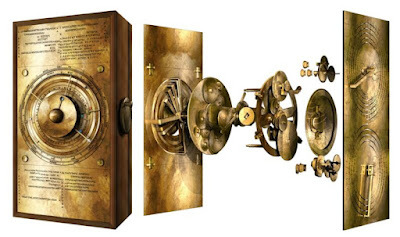

As is so often the case, the truth in this case is far more interesting than the fiction. Jo Marchant and her publishers seem to have found it difficult to settle on a subtitle adequate to the significance of this artefact: "Decoding the Heavens: A 2,000-Year-old Computer and the Century Long Search to Discover Its Secrets" was the first one they came up with. The paperback edition simplified this to "Solving the Mystery of the World's First Computer."

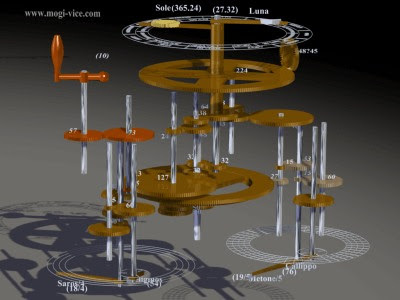

Digital replica of the Antikythera Mechanism (2021)

Digital replica of the Antikythera Mechanism (2021)Is it a computer? Well, that depends on what you mean by the term. Certainly it's an extremely complex calculating machine used - it would appear - to collate and chart astronomical phenomena. So, while it's an analogue rather than a digital device, the concensus of opinion seems to be that "computer" is indeed an appropriate description for it.

Jo Marchant, an award-winning science writer who also has a PhD in Microbiology, has put together a fascinating read. She charts the story of this strange piece of machinery from its recovery in 1901 from an Ancient Greek shipwreck off the island of Antikythera, to its present day place of honour in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Like her predecessor in this particular subgenre, Dava Sobel in Longitude (1995), Marchant assembles a varied cast of heroes and villains along the way. Among the heroes are:

Derek J. de Solla Price (1922-1983)

Derek J. de Solla Price (1922-1983)Derek de Solla Price, who became interested in the mechanism in 1951, after it had been unearthed from the hiding place in which it was concealed during the Nazi occupation of Greece, and who made the first (approximate) reconstruction of it in the early 1970s.

Michael T. Wright (1948- )

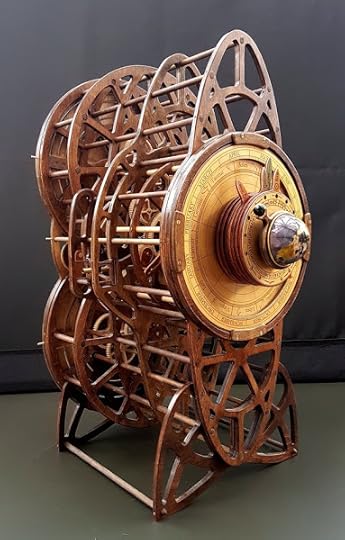

Michael T. Wright (1948- )Michael Wright, who, initially fascinated by Price's monograph Gears from the Greeks (1974), has worked on the mechanism ever since, creating a model in 2006 which is the most accurate so far, and which is now in the Athens museum.

So far so good. There's no doubt that both of these ingenious scholars deserve the warmest praise. Wright appears to have cooperated fully with Marchant's book, which earned him the following encomium in her acknowledgements:

I am greatly indebted to Michael Wright, a gentleman who fielded my never-ending questions with honesty and grace ...

Charles Sturridge, dir. Longitude (2000)

Charles Sturridge, dir. Longitude (2000)Wright is, in effect, Marchant's equivalent to Dava Sobel's John Harrison (1693-1776), the working-class hero whose pioneering work on marine chronometers made possible the accurate determining of longitude at sea.