Jack Ross's Blog, page 3

February 4, 2025

The Uncollected Henry James

Floyd R. Horowitz, ed.: The Uncollected Henry James (2004)

Floyd R. Horowitz, ed.: The Uncollected Henry James (2004)The moment I saw this book in a second-hand shop I knew I had to have it. It's exactly the kind of thing I love: a monomaniac academic's life work, nestled neatly between two covers.

That's not to say that it doesn't come with impressive literary credentials. As the blurb on the back-cover puts it:

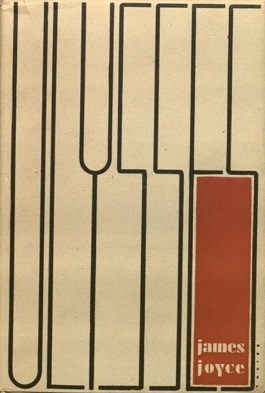

More than two decades of research, study, and literary detection lie behind this treasury of stories by one of the undisputed giants in the field of American fiction, as Professor Floyd Horowitz here offers a collection of tales that he himself has authenticated to be the work of the prodigiously gifted Henry James, ... justly remembered for his novellas and scores of short stories. And there may indeed be scores more [my emphasis], as this important volume shows. Published anonymously or under noms de plume in magazines like nineteenth-century New York's favourite The Knickerbocker, Frank Leslie's Lady's Magazine, The National Magazine, and The Continental, these previously uncollected pieces represent both apprentice work and early stories that already bear the mark of Jamesian artistry. Written in a period of more than ten years before James's first signed fiction appeared (in 1865) ... these uncovered stories add significantly to the James canon.Well, you can't say better than that! So precocious was this studious young man that he apparently wrote (and published) at least 24 stories between the ages of 9 (!) and 26 as a kind of side-hustle to his burgeoning official career as a professional author, which began with "The Story of a Year" in 1865, and eventually grew to include no fewer than 112 stories (as you'll see if you consult this list of his work in that genre).

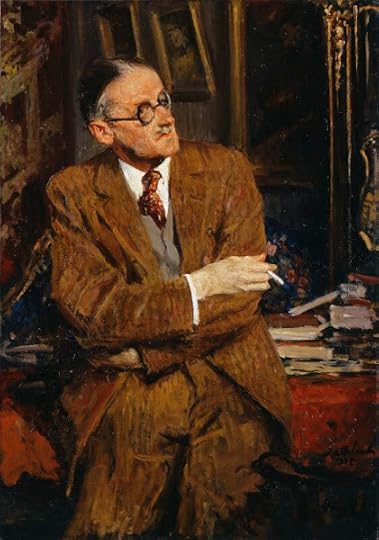

"Henry James as a Young Man" (1843-1916)

"Henry James as a Young Man" (1843-1916)My comments above may sound a little sceptical, but they're not meant to be. After all, most young writers fill page after page with more-or-less accomplished juvenilia before they eventually begin to publish - and many are subsequently anxious to suppress any evidence of early work which appeared in print before they were ready ...

And, in at least partial support of Horowitz's claims, the first item on the list of authenticated James short stories, "A Tragedy of Error" (1864) was indeed published anonymously, and only identified by his biographer Leon Edel through a chance reference in a letter.

Leon Edel, ed. The Complete Tales of Henry James (12 vols: 1962-64)

Leon Edel, ed. The Complete Tales of Henry James (12 vols: 1962-64)For that matter, the first dozen or so of his canonical stories could probably be quietly shelved without any great loss to posterity. The Master himself only included a little over half of the 100-odd novellas and short stories he'd previously published in the multi-volume New York Edition (1907-09), which he definitely intended to stand as his last word on the matter.

Philip Horne, ed. Henry James: A Life in Letters (1999)

Philip Horne, ed. Henry James: A Life in Letters (1999)So what are these new stories like? And, more to the point, are they really all by Henry James? Distinguished Jamesian Philip Horne, editor of the Life in Letters pictured above, is, unfortunately - according to the précis at the top of his review - "not convinced of the authorship of Floyd R Horowitz's 'newly discovered' Henry James stories." That, however, "does not mean that they are not worth reading."

His Guardian article is too long and closely argued to quote here in detail, but I thought I might tease out a few of the more telling points:

Horowitz's central notion is that young James had a secret life as "Leslie Walter", consistently using that pseudonym to get his stories into (mostly unremunerated) print: eight of those here, mostly later ones, seem to be attributable to that author.Horne, however, detects certain problems with this hypothesis:

I discovered, for example, that in January 1869, well after James had broken cover under his own name, "Lesley Walter" published a pretty awful sentimental poem called "Among the Lilies" in the Galaxy: Horowitz doesn't mention the supposed alter ego's unJamesian propensity for verse. And then Leslie Walter's rather monotonous subject matter, supposedly showing a closeness to James's father's Swedenborgian philosophy, seems just conventionally pious ... Indeed, these tales often amount to cases of what [Henry James] used to call with withering scorn "flagrant morality". Horowitz might have done better to claim they were parodies.But he goes on to concede:

This is not to say that one steeped in James, and reading for resemblance, doesn't occasionally come across something that seems strikingly close to the master's voice in these tales, or fleeting parallels of situation. Horowitz has built a certain plausible deniability into his case, moreover, in the sense that these stories are presented as apprentice works, written to the house style of the Knickerbocker or the Newport Mercury, from a period mostly before we have any authenticated James fiction.In other words, anything unlike James can be attributed to his desperation to break into print by aping each journal's house-style. Anything that is like him is clear proof of his authorship. Either way, Horowitz can claim to be vindicated. Horne, however, is not having any:

The greatest value and interest of this collection ... is ultimately not that it's by James, but that it isn't. Short stories reveal worlds even when they're affected or sentimental or badly written, and this book constitutes a vivid picture of the literary, cultural and social universe James entered. Apart from showing us just how original he actually was, it reeks of the dead past ...

Vladimir Nabokov: Pale Fire (1962)

Vladimir Nabokov: Pale Fire (1962)"From time to time one catches a whiff of Pale Fire mania in the confident circularity of Horowitz's logic," Horne comments about the former's methodology - the magic wand which rendered this Computer Science professor capable of nosing out lost pieces of Jamesiana amongst all the reams of abandoned fiction he'd been assembling for the past thirty years.

Pale Fire , for those of you unfamiliar with this most teasing and, in some respects, most worrying of Nabokov's fictions, "is presented as a 999-line poem titled "Pale Fire", written by the fictional poet John Shade, with a foreword, lengthy commentary and index written by Shade's neighbor and academic colleague, Charles Kinbote."

Kinbote, who is (most readers would agree) a delusional monomaniac, "inherited" (i.e. stole) the manuscript of "Pale Fire" after John Shade's murder, and is now attempting to prove in his commentary-cum-autobiography that this poem, which never directly mentions the subject, is nevertheless is almost entirely about him and the (possibly imaginary) country of Zembla, whose lost king he may or may not be.

E. T. A. Hoffmann: Lebens-Ansichten des Katers Murr nebst fragmentarischer Biographie

E. T. A. Hoffmann: Lebens-Ansichten des Katers Murr nebst fragmentarischer Biographiedes Kapellmeisters Johannes Kreisler in zufälligen Makulaturblättern (1855)

Clear? No? You're not alone in feeling a bit puzzled. Suffice it to say that the nutty, monocular professor is a commonplace of post-modern fiction - but actually the idea of writing a self-refuting, self-satirising commentary on what is alleged to be someone else's work goes way back beyond that: to E. T. A. Hoffmann's Life and Opinions of the Tomcat Murr together with a fragmentary Biography of Kapellmeister Johannes Kreisler on Random Sheets of Waste Paper (1819-21); or, even further, to Laurence Sterne's Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy (1759-67); or, for that matter, to the fons et origo of most of Sterne's erudition, Robert Burton's Anatomy of Melancholy (1621).

Tristram Shandy: "And When Death Himself Knocked at My Door" (1769)

Tristram Shandy: "And When Death Himself Knocked at My Door" (1769)So how exactly did Professor Horowitz set about distinguishing Henry James's work from all the other sludge in these ancient journals from the 1850s and 1860s? Philip Horne summarises the two, rather technical, appendices in Horowitz's book as follows:

First, by reading his way through the myriad American magazines and journals of the period, "using a set of critical discriminators". These included "the use of particular words, the employment of what I came to recognise as distinctive syntactical and word patterns, the use of puns and other wordplay, as well as the repetition of symbolic allusions, themes, and ideas". He also found "corroborating ideational evidence in the texts", which built up, in his vision, into "a coherent linguistic and philosophical framework that was consistent with the structures and themes of James's later, signed work". In other words, the evidence is massively internal, and interpretative - one might say subjective.It puts me in mind of that old hymn about Jesus we used to sing at Sunday School:

You ask me how I know He lives?In other words, I don't know, but I'd like to pretend that I do.

He lives within my heart.

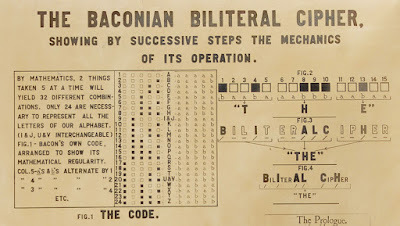

This "I know it when I see it" argument, familiar from Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart's classic 1964 definition of obscenity, is backed up by some pretty hard science in Horowitz's case, however:

In an appendix called "The Computer and the Search for Henry James", Horowitz took the 20,783 words known to have been written by James between 1858 and 1871 and ran stylometric tests on the tales he'd attributed to James - the test being similarity of vocabulary (single words). This yielded a total of 72 stories by James, and another 12 "probably written by James". I was unable to follow the complicated details of his explanation, but confess to an impression that the hurdle set for identification as Jamesian was worryingly low. Stories with the same kinds of setting and with similar themes will surely generate many chimings of vocabulary without being being really similar in style. And there's no test of quality: some of these tales are pretty execrable.72 (+ 12 doubtful cases) is a pretty high number for us to credit. After all, these are stories James allegedly published, not simply wrote, during this period. He must have been banging them out, rain or shine, at a rate of about one a month!

But wait, there's more!

The allusion test, in another appendix called "Allusion as Proof in the Search for Henry James", turns out to mean echoes of things in books in Henry James senior's library, including the Arabian Nights and the King James Bible. Horowitz also detected his young Henry James in putative quasi-Oulipian games with his copy of Anthon's Latin Primer and Reader, taking English words from different columns of the Latin vocabulary lists to generate stories. The problem with these "tests" seemed to me that either the source was very widely known (for example the Bible) or that the words used were not so unusual as to be striking (the Anthon words used to cement Horowitz's case in the short passage he selects as most convincing include "with", "made", "will", "against" and "all") ...Even the most credulous of readers will probably part company with Horowitz when he starts to explain just how James could construct an almost unlimited number of stories out of odd words which just happened to be placed more-or-less contiguously in his Latin Grammar! It all sounds just a little too uncomfortably like those calculations about infinite numbers of monkeys tapping away on infinite typewriters.

Perhaps it's just as well that Horowitz never got to publish the follow-up book Searching for Henry James promised on the blurb for The Uncollected Henry James. At least, I don't think he did. I haven't succeeding in finding any allusions to it online, even in self-published form. What I did find, sadly, was the following for the author himself.

From this I learned that Floyd Horowitz (1930-2014) taught Computer Science at Kansas University for over 30 years, then English at Hunter College, New York for another five years, until his retirement in 1996. He died on August 9th, 2014 "from complications of vascular dementia."

De mortuis nil nisi bonum, as the saying has it: Speak no ill of the dead. I can't help wondering a bit, though. There are some very odd statements - not to mention strikingly eccentric word-choices - in those two appendices at the end of Prof. Horowitz's book. Just how carefully did his editors actually check them before clearing the text for publication?

His obituary concludes, rather poignantly, "He is now at peace."

•

The Lost Love Letters of Heloise and Abelard (1999)

The Lost Love Letters of Heloise and Abelard (1999)Constant J. Mews. The Lost Love Letters of Heloise and Abelard: Perceptions of Dialogue in Twelfth-Century France. Trans. Neville Chiavaroli & Constant J. Mews. 1999. The New Middle Ages. Ed. Bonnie Wheeler. Palgrave. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2001.Mind you, just because it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck doesn't necessarily mean that it is a duck. I recall having a similar uneasy feeling roughly halfway through the book above, by Prof. Constant Mews, son of the composer Douglas Mews, whom I remember very well from my years singing in the Auckland University choir.

Mews's claim to have identified a lost correspondence between medieval scholastic philosopher Peter Abelard and his lover Héloïse d'Argenteuil seemed just a little too good to be true.

The Letters Of Abelard And Heloise (1999)

The Letters Of Abelard And Heloise (1999)Pretty much everyone interested in the story of these two star-crossed lovers is familiar with the book above: a translation of a Latin correspondence between the two conducted many years after Abelard's seduction of the young girl Heloise, whom he'd been hired to tutor by her uncle Fulbert, a canon of Notre Dame.

The Letters of Abelard and Heloise. Trans. Betty Radice. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1974.

The uncle, as you've no doubt heard, took a fearful revenge on the lustful philosopher. He arranged for him to be castrated by some hired ruffians. Abelard survived, just barely, but that and a number of other scandals (including accusations of heresy) made it almost impossible for him to advance in the church.

François Villon (1431-c.1463)

François Villon (1431-c.1463)The story was so famous that it's even referred to in fifteenth-century jailbird poet François Villon's famous "Ballade des dames du temps jadis" [Ballad of Ladies of Past Times]:

Où est la très sage Heloïs,

Pour qui fut chastré et puis moyne

Pierre Esbaillart à Sainct-Denys?

Pour son amour eut cest essoyne.

[Where is the very wise Heloise,

For whom Peter Abelard was castrated

then made a monk at Daint Denis?

For his love had this travail.]

John Hughes: Letters of Abelard and Heloise to Which Is Prefix'd a Particular Account of Their Lives, Amours, and Misfortunes (1743)

John Hughes: Letters of Abelard and Heloise to Which Is Prefix'd a Particular Account of Their Lives, Amours, and Misfortunes (1743)Most readers prefer Heloise's honest and insightful letters to the pompous, top-lofty prevarications of the great scholar, who presumes to lecture her on virtue despite his own obvious shortcomings in that regard.

Mews, however, argues that some earlier letters exchanged by the couple, possibly at the time they first met, have survived in the form of a book of "exemplary letters" for the use of students. As one reviewer commented:

Although the correspondence reproduced and translated [by Mews] has been available to scholars in Latin since Ewald Könsgen's 1974 publication, Mews' edition is the first to translate the letters into English and devote to them the comprehensive commentary they deserve. Könsgen may have made the first tentative suggestions that they might be the letters of Heloise and Abelard, but it is Mews who offers convincing evidence that they are.

Ewald Könsgen: Epistolae duorum amantium (1974)

Ewald Könsgen: Epistolae duorum amantium (1974)In her own, more comprehensive review, Barbara Newman explains that:

Ewald Könsgen's edition of the twelfth-century Latin text he titled Epistolae duorum amantium: Briefe Abaelards und Heloises? [Correspondence of Two Lovers: Letters by Abelard and Heloise?] (Leiden: Brill, 1974), could not have appeared at a worse time. Scholars had been debating the authenticity of Abelard's famous exchange with Heloise for almost a century, but that controversy, after remaining at a simmer for decades, had just reached the boiling point. At a conference at Cluny in 1972, John Benton had proposed that the entire correspondence was forged in the late thirteenth century to influence a disputed election at the Paraclete. In the same year, D. W. Robertson argued in Abelard and Heloise (New York: Dial Press, 1972) that the real forger was Abelard, who created the literary fiction of Heloise's letters as part of an exemplary treatise on conversion ...Which is not to say that Mews's own claims for the correspondence have been accepted by everyone. His critics, however, are quick to deny the accusation that "they are motivated by professional envy at not having got there first."

In such a climate, no scholar could have been expected to stake his credibility on the anonymous love letters discovered by Könsgen in a late 15th-century manuscript from Clairvaux. Könsgen himself, after all, appended a question mark to his title, arguing only that the letters must have been composed in the Ile-de-France in the early twelfth century by two people "like" Abelard and Heloise. Even Peter Dronke, the staunchest defender of Heloise's writing, did not want to connect the famous lovers with this newly edited correspondence. Such an ascription would have seemed literally too good - or too self-interested - to be true. So Könsgen's edition attracted little notice and vanished without a ripple.

"It's not jealousy, it's a question of method," said Monique Goullet, director of research in medieval Latin at Paris's Sorbonne University. "If we had proof that it was Abelard and Heloise then everyone would calm down. But the current position among literature scholars is that we are shocked by too rapid an attribution process."While, as Barbara Newman asserts, "the majority of scholars now accept the established letters as authentic", the burden of proof is certainly on Mews to demonstrate "beyond a reasonable doubt that the authors of these letters were indeed Heloise and Abelard."

Mews argues on both textual and contextual grounds, providing evidence that: (1) learned women did exchange Latin poems and letters with their male admirers in the early twelfth century; (2) the fragmentary narrative that emerges from the recently discovered letters is consistent in all particulars with what we know of Abelard and Heloise; and (3) most important, the philosophical vocabulary, literary style, classical allusions, and contrasting positions on love apparent in Könsgen's letters are so thoroughly consistent with the known writings of Heloise and Abelard that the supposition of their authorship is simpler than any alternative hypothesis.

Jacques Trébouta, dir.: Héloïse et Abélard (1973)

Jacques Trébouta, dir.: Héloïse et Abélard (1973)I guess what surprised me most, after reading Mews's book, was the fact that there hadn't been a lot more fuss about so immense and exciting a claim. After all, the love story between Abelard and Heloise, and in particular the character of Heloise herself, have been revisited repeatedly in popular novels and movies, as well as being exhaustively picked over as a theme in medieval studies. Why, then, isn't Mews's book shelved beside Betty Radice's classic translation of the "established letters"?

Clive Donner, dir. Stealing Heaven (1988)

Clive Donner, dir. Stealing Heaven (1988)Mews is certainly no fool, and his claims for these letters have been subjected to considerable scrutiny. The alternative explanations offered by some of his critics that it may be "a literary work written by one person who decided to reconstitute the writings of Abelard and Heloise," or "a stylistic exercise between two students who imagined themselves as the lovers, or that it was written by another couple," are perhaps rather less convincing than their own authors may imagine.

As Barbara Newman puts it:

the woman of the Troyes letters simply sounds like Heloise and like no other medieval Latin writer known to us.I wish that that could be the last word on the matter, but I fear that the jury will remain out for a long time yet: possibly forever.

•

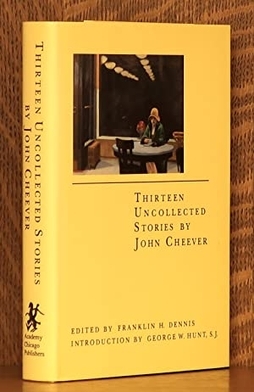

John Cheever: Thirteen Uncollected Stories (1994)

John Cheever: Thirteen Uncollected Stories (1994)So, we have one probable attribution: the "new" Heloise and Abelard letters; and one rather more dubious item, the "uncollected" Henry James stories. Let's conclude with another bibliographical curiosity, these 13 stories by American author John Cheever.

Thirteen Uncollected Stories by John Cheever. Ed. Franklin H. Dennis. Introduction by George W. Hunt, S.J. Note by Matthew Bruccoli. Chicago: Academy Chicago Publishers, 1994.

John Cheever (1912-1982)

John Cheever (1912-1982)This is how Wikipedia describes the débâcle surrounding their appearance:

The publication of Thirteen Uncollected Stories by John Cheever had its genesis in a copyright dispute beginning in 1988 between a small publisher, Academy Chicago Publishers, and Cheever's widow, Mary Wintemitz Cheever. Mary Cheever had entered into a contract with Academy for the nominal fee of $1500 to permit publication of a sampling of Cheever's uncollected early short fiction, pending family consultation. When the publisher sought to include all the works not published in The Stories of John Cheever (1978) — a total of 68 stories — a protracted legal struggle ensued.Here there are no doubts at all about the stories' status and genesis: just the desirability of having them in print, alongside the more mature work of this consummate fictional stylist.

Mary Cheever prevailed, but Academy Chicago succeeded in securing publication rights to a total of thirteen stories whose copyrights had lapsed. These are the stories that appear in Thirteen Uncollected Stories by John Cheever.

But that's not really how most academics think: they see the recovery of lost texts as the crown of their scholarly achievements. No wonder so many writers end up burning all their papers - if they get the chance, that is!

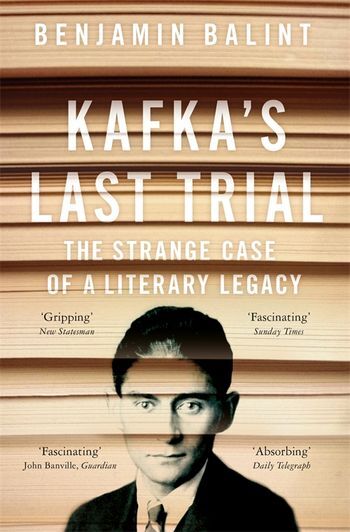

Having a foot in both camps, I can sympathise with both of these attitudes. For the most part, I tend to side with the writers. Who knows, though? Which of us isn't ready to call down blessings on the head of Max Brod for not heeding the instructions of his friend Franz Kafka to burn all of his unpublished literary remains, including The Trial, The Castle, and America?

Benjamin Balint: Kafka's Last Trial: The Case of a Literary Legacy (2018)

Benjamin Balint: Kafka's Last Trial: The Case of a Literary Legacy (2018)•

Published on February 04, 2025 12:29

January 24, 2025

Favourite Children's Authors: Rosemary Sutcliff

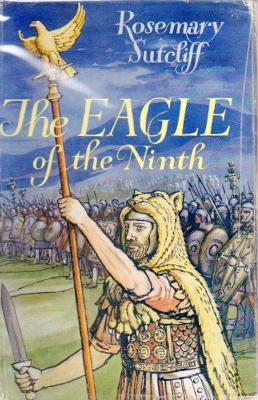

Rosemary Sutcliff: The Eagle of the Ninth (1954)

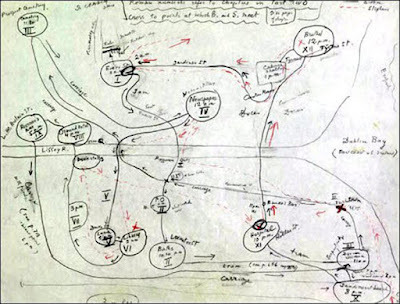

Rosemary Sutcliff: The Eagle of the Ninth (1954)I wonder how kids nowadays would respond to a book like this? It's exerted a strange fascination over me ever since I first read it in our little school library when I was about 10 or 11 - not so much the details of Roman Army life as the curious atmosphere of the land beyond the frontier: the tribal territories past Hadrian's wall which Marcus Flavius Aquila is forced to negotiate in order to recover the Eagle emblem of his father's legion, the lost Ninth.

In particular, I was impressed by the decision of the sole survivor of the massacred army to stay where he was: "There is no way back past the waters of Lethe." I didn't know (then) what the waters of Lethe were, or even how to pronounce the word, but I got the point. Like a white settler adopted by a Native American community, his incentive to rejoin "civilisation" seemed strangely lacking.

Kevin Macdonald, dir.: The Eagle (2011)

Kevin Macdonald, dir.: The Eagle (2011)That was where the (fairly) recent movie fell short for me - there was too much emphasis on macho heroics, and Channing Tatum was not at all my image of the sensitive, cerebral Marcus of Sutcliff's book.

Michael Simpson & Baz Taylor, dir.: The Eagle of the Ninth (1977)

Michael Simpson & Baz Taylor, dir.: The Eagle of the Ninth (1977)There is, apparently, an old British TV miniseries as well, but I've never seen it. It looks pretty clunky from the excerpts included on the imdb, but it would be rather amusing to see Patrick Malahide playing a Pictish tribesman at what must have been the very outset of his career ...

So popular was The Eagle of the Ninth when it first appeared, that Rosemary Sutcliff decided to use Marcus's family, the Aquilas, as the basis for a whole series of novels about the last days of Roman rule in England - and the growth of a new, Anglo-Saxon culture in its place. In each of these books reference is made at some point to an emerald seal ring with a dolphin embossed on it, which had been handed down in the family for generations.

Here (courtesy of Wikpedia) are all eight novels in order - not of publication, but of fictional chronological sequence:

Rosemary Sutcliff: Three Legions (1980)

Rosemary Sutcliff: Three Legions (1980)The Eagle of the Ninth Series:

The Eagle of the Ninth (1954)The Silver Branch (1957)Frontier Wolf (1980)The Lantern Bearers (1959)Sword at Sunset (1963)Dawn Wind (1961)Sword Song (1997)The Shield Ring (1956)

Sutcliff herself was clearly someone who had to surmount more than her fair share of challenges. Confined to a wheelchair from most of her adult life as a result of contracting Still's disease (or juvenile rheumatoid arthritis) as a child, she grew up in Malta and various other bases where her father, a Naval Officer, was stationed.

As a result she had a rather unconventional education, not even learning to read until she was 9 years old. She eventually left school at 14 to attend Art College. After graduating from there, she worked initially as a painter of miniatures. She published her first book, The Chronicles of Robin Hood, in 1950, at the age of 30. The Eagle of the Ninth, her sixth novel, came out in 1954.

Having been runner-up for the Carnegie Medal for the year's best children's book by a British writer on four previous occasions, she eventually won it in 1959 for The Lantern-Bearers.

Perhaps I'm prejudiced, but the books she wrote in the 1950s and early 1960s seem to me more powerful and lasting than much of her later work. That may simply be a matter of having read them at the right age, however. Certainly it was during that period that her own engagement with the Arthurian legend began.

Rosemary Sutcliff: Sword at Sunset (1963)

Rosemary Sutcliff: Sword at Sunset (1963)Arthurian novels:

The Lantern Bearers (1959) Sword at Sunset (1963) Tristan and Iseult (1971)The Arthurian Trilogy:The Sword and the Circle (1981)The Light Beyond the Forest (1979)The Road to Camlann (1981) The Shining Company (1990)

Her most powerful and enduring contribution to the subject, Sword at Sunset, begins - like Mary Stewart's The Crystal Cave - with an epigraph: Francis Brett Young's poem "Hic Jacet Arthurus Rex Quondam Rexque Futurus

It's interesting, in retrospect, to observe just how much this "End of Empire" theme resonated with Sutcliff, as with many other writers of the post-war generation. Imperial Rome was clearly, for them, almost interchangeable with Imperial Britain - and their intense nostalgia for the order and unquestioned assumptions of childhood creeps into all their accounts of "Saxon hordes" overwhelming the last few urbane flickers of Roman civilisation.

Arthur is gone . . . Tristram in Careol

Sleeps, with a broken sword - and Yseult sleeps

Beside him, where the Westering waters roll

Over drowned Lyonesse to the outer deeps.

Lancelot is fallen . . . The ardent helms that shone

So knightly and the splintered lances rust

In the anonymous mould of Avalon:

Gawain and Gareth and Galahad - all are dust.

Where do the vanes and towers of Camelot

And tall Tintagel crumble? Where do those tragic

Lovers and their bright eyed ladies rot?

We cannot tell, for lost is Merlin's magic.

And Guinevere - Call her not back again

Lest she betray the loveliness time lent

A name that blends the rapture and the pain

Linked in the lonely nightingale's lament.

Nor pry too deeply, lest you should discover

The bower of Astolat a smokey hut

Of mud and wattle - find the knightliest lover

A braggart, and his lilymaid a slut.

And all that coloured tale a tapestry

Woven by poets. As the spider's skeins

Are spun of its own substance, so have they

Embroidered empty legend - What remains?

This: That when Rome fell, like a writhen oak

That age had sapped and cankered at the root,

Resistant, from her topmost bough there broke

The miracle of one unwithering shoot.

Which was the spirit of Britain - that certain men

Uncouth, untutored, of our island brood

Loved freedom better than their lives; and when

The tempest crashed around them, rose and stood

And charged into the storm's black heart, with sword

Lifted, or lance in rest, and rode there, helmed

With a strange majesty that the heathen horde

Remembered when all were overwhelmed;

And made of them a legend, to their chief,

Arthur, Ambrosius - no man knows his name -

Granting a gallantry beyond belief,

And to his knights imperishable fame.

They were so few . . . We know not in what manner

Or where they fell - whether they went

Riding into the dark under Christ's banner

Or died beneath the blood-red dragon of Gwent.

But this we know; that when the Saxon rout

Swept over them, the sun no longer shone

On Britain, and the last lights flickered out;

And men in darkness muttered: Arthur is gone . . .

Sutcliff, however, was unusual in being able to see the other side of the equation as well. Her doomed Saxon warriors facing the oncoming Norsemen in The Shield Wall shows an evenhandedness of treatment, as well as a determination to back underdogs against aggressive invaders somewhat reminiscent of the revisionist historical novels of her near-contemporary Geoffrey Trease.

Sutcliff's later works on King Arthur largely content themselves with retelling Malory. But Sword at Sunset is still well worth reading. Her intimate knowledge of weariness and despair seems to have made her exceptionally good at depicting self-doubting, non-triumphant heroes.

That's what continues to ring true in her books, and makes her portrayal of the savage, tormented Cuchulain, the so-called "Hound of Ulster", so much more successful than her dutiful recital of The High Deeds of Finn MacCool.

Rosemary Sutcliff: The Hound of Ulster (1963)

Rosemary Sutcliff: The Hound of Ulster (1963)When I think now about my first acquaintance with her books, I remember that I was almost afraid of them. She wasn't content with simple plots about everyday dilemmas: there was genuine violence and fear in almost all of them, as well as a lot more squalid (and smelly) local detail than was typical in children's historical novels of the time.

I can't help thinking that the hardships of her own life must have played against the sentimental romanticism implanted by her mother to create a strikingly realistic - and, for the time, very well researched - series of fantasies of the past. Books such as Warrior Scarlet or Outcast do not sugarcoat the subjects of violence and dispossession.

At times, as in Dawn Wind, she let her guard down and allowed a few rays of hope to steal in - her preference though, as in Francis Brett Young's poem, seems always to have been for the defiant last stand.

Anthony Lawton: Which book do readers think is Rosemary Sutcliff’s best? (2022)

Anthony Lawton: Which book do readers think is Rosemary Sutcliff’s best? (2022)•

Rosemary Sutcliff (1984)

Rosemary Sutcliff (1984)Rosemary Sutcliff

(1920-1992)

Books I own are marked in bold:Children's Novels:

The Chronicles of Robin Hood. Illustrated by C. Walter Hodges (1950)The Queen Elizabeth Story. Illustrated by C. Walter Hodges (1950)The Armourer's House. Illustrated by C. Walter Hodges (1951)The Armourer's House. Illustrated by C. Walter Hodges. 1951. Oxford Children’s Library. London: Oxford University Press, 1962. Brother Dusty-Feet. Illustrated by C. Walter Hodges (1952)Brother Dustyfeet. Illustrated by C. Walter Hodges. 1952. Oxford Children’s Library. London: Oxford University Press, 1961. Simon. Illustrated by Richard Kennedy (1953)Simon. Illustrated by C. Walter Hodges. 1953. Oxford Children’s Library. London: Oxford University Press, 1959. The Eagle of the Ninth. Illustrated by C. Walter Hodges (1954)The Eagle of the Ninth. Illustrated by C. Walter Hodges. 1954. London: Oxford University Press, 1973.Included in: Three Legions: The Eagle of the Ninth; The Silver Branch; The Lantern Bearers. 1954, 1957, 1959, 1980. Puffin Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985. Outcast. Illustrated by Richard Kennedy (1955)Outcast. 1955. Illustrated by Richard Kennedy. 1955. New Oxford Library. London: Oxford University Press, 1980. The Shield Ring. Illustrated by C. Walter Hodges (1956)The Shield Ring. Illustrated by C. Walter Hodges. 1956. London: Oxford University Press, 1957. The Silver Branch. Illustrated by Charles Keeping (1957)The Silver Branch. Illustrated by Charles Keeping. 1957. Puffin Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1980.Included in: Three Legions: The Eagle of the Ninth; The Silver Branch; The Lantern Bearers. 1954, 1957, 1959, 1980. Puffin Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985. Warrior Scarlet. Illustrated by Charles Keeping (1958)Warrior Scarlet. Illustrated by Charles Keeping. 1958. Puffin Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1976.Iincluded in: The Best of Rosemary Sutcliff: Warrior Scarlet; The Mark of the Horse Lord; Knight's Fee. Illustrated by Charles Keeping. 1958, 1963, 1960. London: Chancellor Press, 1987. The Lantern Bearers (1959)The Lantern Bearers. Illustrated by Charles Keeping. 1959. London: Oxford University Press, 1972.Included in: Three Legions: The Eagle of the Ninth; The Silver Branch; The Lantern Bearers. 1954, 1957, 1959, 1980. Puffin Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985. Knight's Fee. Illustrated by Charles Keeping (1960)Knight's Fee. Illustrated by Charles Keeping. 1960. Oxford Children’s Library. London: Oxford University Press, 1974.Iincluded in: The Best of Rosemary Sutcliff: Warrior Scarlet; The Mark of the Horse Lord; Knight's Fee. Illustrated by Charles Keeping. 1958, 1963, 1960. London: Chancellor Press, 1987. Bridge Builders. Illustrated by Douglas Relf (1960)Beowulf: Dragonslayer. Illustrated by Charles Keeping (1961)Dawn Wind. Illustrated by Charles Keeping (1961)Dawn Wind. Illustrated by Charles Keeping. 1961. London: Oxford University Press, 1970. The Hound of Ulster. Illustrated by Victor Ambrus (1963)The Hound of Ulster. Illustrated by Victor Ambrus. London: The Bodley Head, 1963. The Mark of the Horse Lord. Illustrated by Charles Keeping (1965)Iincluded in: The Best of Rosemary Sutcliff: Warrior Scarlet; The Mark of the Horse Lord; Knight's Fee. Illustrated by Charles Keeping. 1958, 1965, 1960. London: Chancellor Press, 1987. The Chief's Daughter. Illustrated by Victor Ambrus (1967)The Chief's Daughter. 1966. Illustrated by Victor Ambrus. 1967. Piccolo. London: Pan Books, 1978. The High Deeds of Finn MacCool. Illustrated by Michael Charleton (1967)The High Deeds of Finn MacCool. Illustrated by Michael Charlton. London: The Bodley Head, 1967. A Circlet of Oak Leaves. Illustrated by Victor Ambrus (1968)The Witch's Brat. Illustrated by Richard Lebenson (1970)The Truce of the Games. Illustrated by Victor Ambrus (1971)Tristan and Iseult (1971)Tristan and Iseult. 1971. Illustrated by Victor Ambrus. Puffin Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1974. Heather, Oak, and Olive: Three Stories ["The Chief's Daughter", 1967; "A Circlet of Oak Leaves", 1968; "A Crown of Wild Olive", 1971]. Illustrated by Victor Ambrus (1972)The Capricorn Bracelet: Six Stories. Illustrated by Charles Keeping & Richard Cuffari (1973)The Changeling. Illustrated by Victor Ambrus (1974)[with Margaret Lyford-Pike] We Lived in Drumfyvie (1975)Blood Feud. Illustrated by Charles Keeping (1976)Blood Feud. 1976. Illustrated by Charles Keeping. Puffin Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978. Sun Horse, Moon Horse. Illustrated by Shirley Felts (1977)Sun Horse, Moon Horse. 1977. Decorations by Shirley Felts. Knight Books. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1982. Shifting Sands. Illustrated by Laslzo Acs (1977)Song for a Dark Queen (1978)The Light Beyond the Forest. Illustrated by Shirley Felts (1979)Three Legions [aka Eagle of the Ninth Chronicles (2010)] ["The Eagle of the Ninth", 1954; "The Silver Branch", 1957; "The Lantern Bearers", 1959] (1980)Three Legions: The Eagle of the Ninth; The Silver Branch; The Lantern Bearers. 1954, 1957, 1959, 1980. Puffin Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985. Frontier Wolf (1980)Frontier Wolf. 1980. Puffin Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1984. Eagle's Egg. Illustrated by Victor Ambrus (1981)The Sword and the Circle. Illustrated by Shirley Felts (1981)The Road to Camlann. Illustrated by Shirley Felts (1981)Bonnie Dundee (1983)Bonnie Dundee. 1983. Puffin Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985. Flame-coloured Taffeta. Illustrated by Rachel Birkett (1986)The Roundabout Horse. Illustrated by Alan Marks (1986)A Little Dog Like You. Illustrated by Jane Johnson (1987)The Best of Rosemary Sutcliff ["Warrior Scarlet", 1958; "The Mark of the Horse Lord", 1965; "Knight's Fee", 1960]. Illustrated by Charles Keeping (1987)The Best of Rosemary Sutcliff: Warrior Scarlet; The Mark of the Horse Lord; Knight's Fee. Illustrated by Charles Keeping. 1958, 1965, 1960. London: Chancellor Press, 1987. The Shining Company (1990)The Minstrel and the Dragon Pup. Illustrated by Emma Chichester Clark (1993)Black Ships Before Troy. Illustrated by Alan Lee (1993)Chess-Dream in a Garden. Illustrated by Ralph Thompson (1993)The Wanderings of Odysseus. Illustrated by Alan Lee (1995)Sword Song (1997)Sword Song. 1997. Red Fox Classics. London: Random House Children’s books, 2001. King Arthur Stories: Three Books in One [aka The King Arthur Trilogy (2007)] ["The Sword and the Circle", 1981; "The Light Beyond the Forest", 1979; "The Road to Camlann", 1981] (1999)

Novels for adults:

Lady in Waiting (1957)The Rider of the White Horse (1959)The Rider of the White Horse. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1959. Sword at Sunset (1963)Sword at Sunset. London: The Book Club, 1963. The Flowers of Adonis (1969)The Flowers of Adonis. 1969. London: Hodder Paperbacks, 1971. Blood and Sand (1987)Blood and Sand. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1987.

Autobiography:

Blue Remembered Hills: A Recollection (1983)Blue Remembered Hills: A Recollection. 1983. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984.

Non-fiction:

Houses and History. Illustrated by William Stobbs (1960)Rudyard Kipling (1960)Heroes and History. Illustrated by Charles Keeping (1965)People of the Past: A Saxon Settler. Illustrated by John Lawrence (1965)

•

Rosemary Sutcliff: Blue Remembered Hills (1983)

Rosemary Sutcliff: Blue Remembered Hills (1983)•

Published on January 24, 2025 14:41

January 8, 2025

Favourite Children's Authors: Mary Stewart

Mary Stewart: A Walk in Wolf Wood (1980)

Mary Stewart: A Walk in Wolf Wood (1980)It seems like an auspicious sign that I should have run across a first edition of Mary Stewart's A Walk in Wolf Wood in a vintage shop on New Year's Eve.

It's not my favourite among her children's books, but it's still a nice piece of timeslip fiction, with werewolves, and enchantments, and enchanted talismans, and all the usual appurtenances of her stories.

The American edition was actually subtitled "A Tale of Fantasy and Magic", in case potential buyers might be in doubt on the matter.

Mary Stewart: Ludo and the Star Horse (1974)

Mary Stewart: Ludo and the Star Horse (1974)More to the point, I'd only seen it previously as a rather scruffy little paperback, whereas this hardback looks exceptionally handsome alongside my copies of her other two books in the genre, Ludo and the Star Horse and The Little Broomstick.

Mary Stewart: The Little Broomstick (1971)

Mary Stewart: The Little Broomstick (1971)The latter has recently been filmed - with a largely rewritten plot and somewhat sub-standard animation - as Mary and the Witch's Flower by Studio Ghibli. I'm normally a fan of their work, but in this case they didn't really succeed in catching the richly atmospheric simplicity of the original: a fantasy classic if ever there was one.

In particular, Endor College, Madam Mumblechook's School of Witchcraft and Wizardry seems like a definite prototype for J. K. Rowling's Hogwarts. And there are many other seemingly throwaway details in Stewart's story, such as the strangely offkilter nursery rhymes recited within the walls of the college, which have stayed stuck in my head for all these years.

Hiromasa Yonebayashi, dir.: Mary and the Witch's Flower (2017)

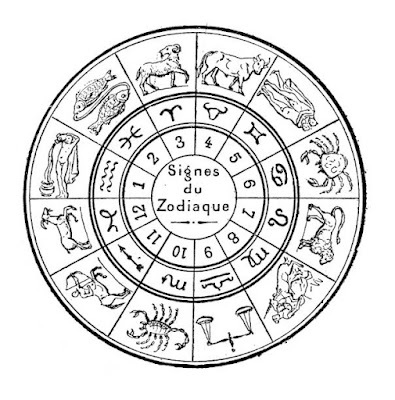

Hiromasa Yonebayashi, dir.: Mary and the Witch's Flower (2017)The Little Broomstick is probably Stewart's best and most inventive children's book. And yet, despite that, I wouldn't call it my favourite among the three. Ludo and the Star Horse, her cleverly concocted guide to the signs of the Zodiac and other wonders of the night sky, is the one I never tire of.

Of course, as with most children's books, to get their full flavour you really have to have been there - to have read them when you were still a kid. The Little Broomstick was published when I was nine, and Ludo when I was twelve. I don't know when my parents first bought them, but probably on first publication, given the fact that both are first editions.

I certainly had no objections at that age to reading "girly" kid's books alongside the more boy's-own offerings of W. E. Johns, Arthur Catherall et al. My sister Anne was a fan of Mary Stewart's romance novels, which meant that I ended up reading all of those, too. Despite my initial misgivings, I found I really liked them - particularly the ones set in exotic locales such as Provence or the Greek Islands.

Mary Stewart: Romance Novels (2020)

Mary Stewart: Romance Novels (2020)It's alleged that Charles Darwin had two criteria for the novels he read as a respite from his labours: they had to have a happy ending, and the heroine must be good-looking. Much ink has been spilt on the rich irony of this juxtaposition: the prophet of biological determinism a closet sentimentalist in his off-hours!

There's something to be said for such comfortable generic expectations, though. Mary Stewart, the uncrowned "Queen of Romantic Suspense", understood exactly what her audience wanted: a frisson of fear, some dark shadows at the heart of the narrative, but no devastating surprises at the end. She was always more of an Ann Radcliffe than a Monk Lewis.

Mary Stewart: The House of Letterawe

Mary Stewart: The House of LetteraweAnd so it might have gone on indefinitely. She published a new book virtually every year between 1955 and 1968. Her publishers were happy; the fans were satisfied; she seemed to have found her ideal role both in literature and life, in her grand estate on Loch Awe in the Scottish Highlands.

Mary Stewart: The Crystal Cave (1970)

Mary Stewart: The Crystal Cave (1970)But then something happened: something unprecedented and completely off-topic. She wrote the autobiography of a Dark Ages boy with prophetic gifts, a boy called Merlin. She called it The Crystal Cave, after a strange little poem by Orkney writer Edwin Muir:

O Merlin in your crystal caveFans of her romance novels had no idea what to make of all this. She did write a few more in that vein, at widely scattered intervals, but from now on she was firmly in the grip of the Arthurian bug, which I've written more about here and here.

Deep in the diamond of the day,

Will there ever be a singer

Whose music will smooth away

The furrow drawn by Adam's finger

Across the memory and the wave?

Or a runner who'll outrun

Man's long shadow driving on,

Break through the gate of memory

And hang the apple on the tree?

Will your magic ever show

The sleeping bride shut in her bower,

The day wreathed in its mound of snow

and Time locked in his tower?

I called it "England's Dreaming" in the second of these posts, where I tried to link this fascination with the possible historicity of a figure called "King Arthur" with the wider subject of literary psychogeography.

However you try to account for it, though, this fascinating mania was at its height in the 1960s and 70s - presumably as part of the contemporary revival of New Age ideologies of nature worship and revived paganism.

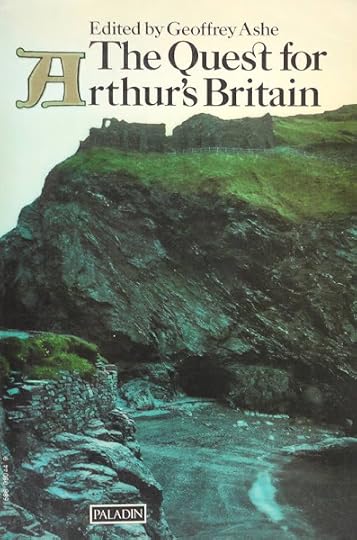

Geoffrey Ashe, ed.: The Quest for Arthur's Britain (1971)

Geoffrey Ashe, ed.: The Quest for Arthur's Britain (1971)Geoffrey Ashe's Quest for Arthur's Britain was one of the Bibles of the new faith - even more than his slew of other books on the subject - principally because it seemed to promise concrete archaeological evidence for the existence of a charismatic warlord who flourished in the late 5th century, at much the same time as the romanticised "King Arthur."

A kind of orthodoxy grew up which took for granted that the resistance of the last Romano-Britains against the incoming Saxons had given rise not only to the idea but also a good deal of the detail of the exploits of this "Arthur" - whatever he looked like, and wherever he was based.

The intensity of Mary Stewart's imagination enabled her to flesh out this Romano-British world, still full of the relics of empire but gradually sliding into the chaotic world of tribal rivalries and local warlords.

Joan Grant: Winged Pharaoh (1937)

Joan Grant: Winged Pharaoh (1937)Her book was, accordingly, a massive success. It remains not only tremendously readable but also strangely persuasive in its vision of those long-lost times, poised between Classical antiquity and the oncoming heroic age. It was as if she'd had a vision, or an out-of-body experience, along the lines of the "reincarnation novels" of English parapsychologist Joan Grant.

The difference was that Mary Stewart could write.

Mary Stewart: The Hollow Hills (1973)

Mary Stewart: The Hollow Hills (1973)Am I the only one to have found the sequel a little disappointing? Merlin gradually retreats from centre stage to share the limelight with the boy Arthur who (I'm sorry to say) has little of the same incandescent star power.

There's less (I suppose inevitably) of the magic of a child's intense perceptions of the world, and more of the necessary politics involved in setting up a kingdom in Dark Age Britain.

It's still all very well written, mind you - and it's hard to imagine any normal reader actually stopping reading following Stewart's expertly woven story at the end of book one, but I'm afraid that it's The Crystal Cave which remains the masterpiece. The other books simply serve to flesh out the theme it proposes.

Mary Stewart: The Last Enchantment (1979)

Mary Stewart: The Last Enchantment (1979)Those of us who read these books when they first came out had a long weary wait before we could get out hands on The Last Enchantment. And it was bound to be a disappointment on some level, given this level of anticipation.

It's good enough. It completes the trilogy - Merlin's story is told to its end, though there are still some aspects of Arthur's left to fill in. Or so Stewart must have thought, anyway, as she went on to write a further instalment, devoted to the equally crucial figure of Mordred.

Mary Stewart: The Wicked Day (1983)

Mary Stewart: The Wicked Day (1983)He is, of course, in many ways the most interesting character in the whole story: the Judas to Arthur's Christ. No-one's exactly cracked him yet, but there have been some pretty good attempts along the way.

Is this one of them? Up to each reader to decide, I guess. ...

Mary Stewart: The Prince and the Pilgrim (1995)

Mary Stewart: The Prince and the Pilgrim (1995)And finally, last and definitely least, there's The Prince and the Pilgrim. Stewart was nearly 80 when she published this last addendum to her Arthurian world, and by then the kettle was no longer really on the boil.

The only reason I knew this book even existed was because I found a copy in a bach where I was staying one summer. Of course I promptly read it from cover to cover.

It's not really part of her main Arthurian sequence - nor is it simply a romance novel set in those historical times - but it has elements of both of those things. There's no real harm in it, but it's doubtful if there's much point in it either.

From anyone else, it would simply seem a straightforward potboiler, but I guess it's just the contrast with the wildly passionate writer of The Crystal Cave which makes it seem an unfortunate coda to her career as a visionary historical novelist.

Mary Stewart Omnibus: Rose Cottage / Stormy Petrel / Thornyhold (1999)

Mary Stewart Omnibus: Rose Cottage / Stormy Petrel / Thornyhold (1999)She published a few last novella-length fictions in her original romance vein, with occasional flashes of the old brilliance, but the heart of her work lies earlier: in those first fresh novels, intoxicated by the love of travel and romance in foreign parts; also in the magic of the three children's books.

Above all, it rests on the unforgettable intensity of The Crystal Cave.

Weird Tales: The Werewolf Howls (1941)

Weird Tales: The Werewolf Howls (1941)•

Mary Stewart

Mary StewartLady Mary Florence Elinor Stewart [née Rainbow]

(1916-2014)

Novels:

Madam, Will You Talk? (1955)Madam, Will You Talk? 1955. London: Hodder Paperbacks Ltd., 1971. Wildfire at Midnight (1956)Wildfire at Midnight. 1956. Coronet Books. London: Hodder Paperbacks Ltd., 1974. Thunder on the Right (1957)Thunder on the Right. 1957. Coronet Books. London: Hodder Paperbacks Ltd., 1972. Nine Coaches Waiting (1958)Nine Coaches Waiting. 1958. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1964.The Castle of Danger [Young Adult version] (Longman simplified TESL Series, 1981) My Brother Michael (1959)My Brother Michael. 1959. Coronet Books. London: Hodder Paperbacks Ltd., 1973. The Ivy Tree (1961)The Ivy Tree. 1961. Coronet Books. London: Hodder Paperbacks Ltd., 1975. The Moon-Spinners (1962)The Moonspinners. 1962. Coronet Books. London: Hodder Paperbacks Ltd., 1973. This Rough Magic (1964)This Rough Magic. 1964. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1966. Airs Above the Ground (1965)Airs Above the Ground. London: Readers Book Club, 1965. The Gabriel Hounds (1967)The Gabriel Hounds. 1967. London: Hodder Paperbacks Ltd., 1968. The Wind Off the Small Isles (1968)The Wind off the Small Isles. Illustrated by Laurence Irving. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1968. Touch Not the Cat (1976)Touch Not the Cat. 1976. Coronet Books. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1977. Thornyhold (1988)Stormy Petrel (1991)Stormy Petrel. London: BCA, by arrangement with Hodder and Stoughton, 1991. Rose Cottage (1997)

Series:

The Merlin Chronicles (1970-1995)The Crystal Cave (1970)The Crystal Cave. 1970. Hodder Paperbacks. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1971. The Hollow Hills (1973)The Hollow Hills. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1973. The Last Enchantment (1979)The Last Enchantment. 1979. Coronet Books. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1980. The Wicked Day (1983)The Wicked Day. 1983. Coronet Books. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1984. The Prince and the Pilgrim (1995)The Prince and the Pilgrim. 1995. Coronet Books. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1996.

Children's novels:

The Little Broomstick (1971)The Little Broomstick. Illustrated by Shirley Hughes. Leicester: Brockhampton Press Ltd., 1971. Ludo and the Star Horse (1974)Ludo and the Star Horse. Illustrated by Gino D’Achille. Leicester: Brockhampton Press Ltd., 1974. A Walk in Wolf Wood (1980)A Walk in Wolf Wood. Illustrated by Doreen Caldwell. Hodder and Stoughton Children's Books. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1980.

Poetry:

Frost on the Window: And other Poems (1990)

•

Signs of the Zodiac

Signs of the Zodiac

Aquarius: The Water-Bearer (January 20 – February 18)Deity: GANYMEDE, cupbearer of the gods Pisces: The Fish (February 19 - March 20)Deity: APHRODITE & EROS, goddess of love & god of desire Aries: The Ram (March 21 – April 19)Deity: ARES, god of war Taurus: The Bull (April 20 – May 20)Deity: ZEUS, king of the gods Gemini: The Twins (May 21 – June 20)Deity: APOLLO & ARTEMIS, the divine siblings Cancer: The Crab (June 21 – July 22)Deity: HERA, queen of the gods Leo: The Lion (July 23 – August 22)Deity: ZEUS, king of the gods Virgo: The Virgin (August 23 – September 22)Deity: DEMETER, goddess of agriculture Libra: The Scales (September 23 – October 22)Deity: THEMIS, goddess of justice Scorpio: The Scorpion (October 23 – November 21)Deity: ARTEMIS, goddess of the hunt Sagittarius: The Archer (November 22 – December 21)Deity: APOLLO, the archer Capricorn: The Sea-Goat (December 22 – January 19)Deity: PAN, god of the wild

•

Published on January 08, 2025 13:58

January 6, 2025

The World of Shakespeare

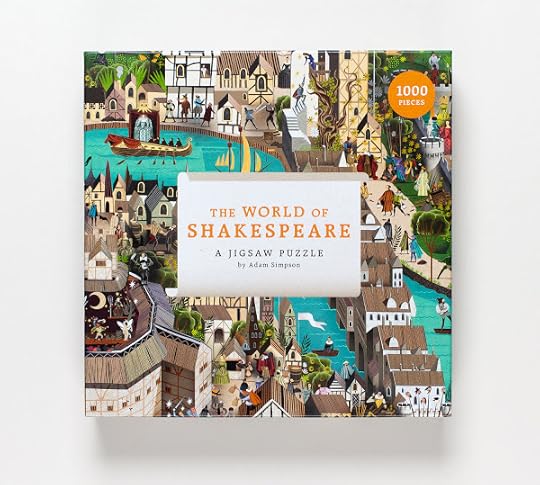

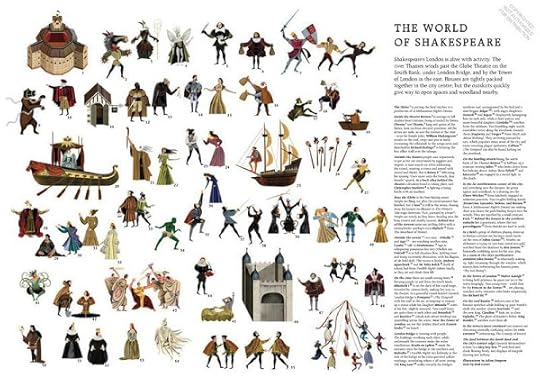

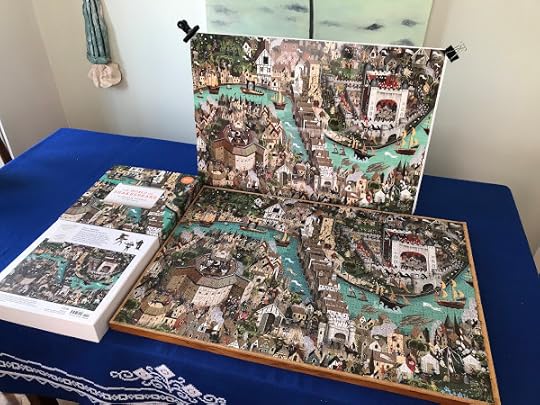

Adam Simpson: The World of Shakespeare (2019)

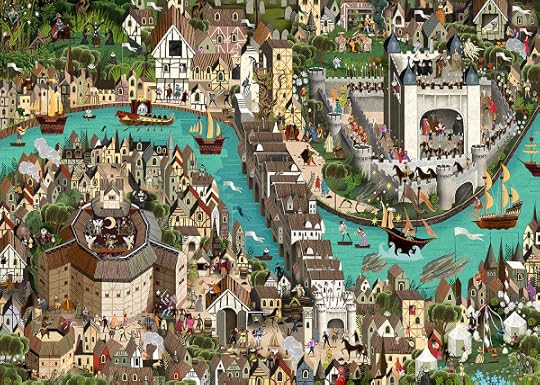

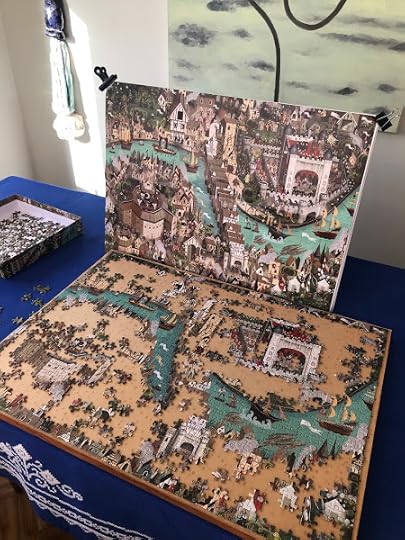

Adam Simpson: The World of Shakespeare (2019)I'm not sure if four times in a row constitutes a tradition, but this is the fourth time Bronwyn and I have seen the New Year in with a (for us, at least) maniacally difficult jigsaw puzzle.

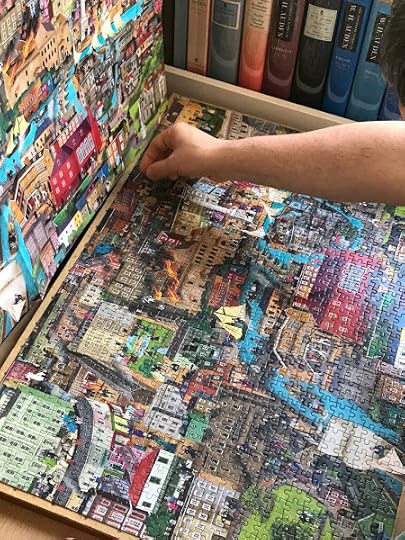

In 2022 it was The World of Charles Dickens :

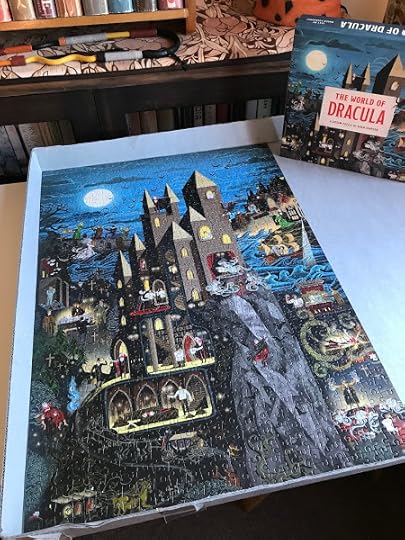

In 2023 it was The World of Dracula :

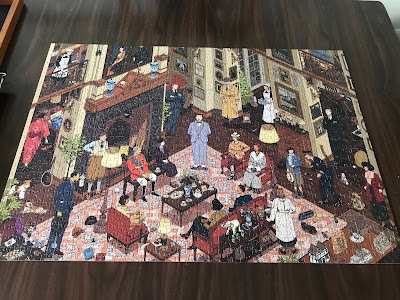

Last year, 2024, it was The World of Hercule Poirot :

This year, 2025, it's Shakespeare in the hot seat:

Adam Simpson: The World of Shakespeare (2019)

Adam Simpson: The World of Shakespeare (2019)I've already written a number of posts about Shakespeare - one about the sources for his plays; another about the differences between the quarto and folio editions of his works; and, most recently, one about that perennial question whether Shakespeare was really Shakespeare - or somebody else of the same name.

The World of Shakespeare

The World of ShakespearePhotograph: Bronwyn Lloyd (5/1/25)

To tell you the truth, it's a bit of a relief to get out from under that last question and down to the nitty-gritty details of Shakespeare's London: complete with rebel heads on pikes, Gloriana on a floating barge, and a variety of theatrical troupes performing his plays.

Adam Simpson: The World of Shakespeare (2019)

Adam Simpson: The World of Shakespeare (2019)As you'll have gathered, Shakespeare for me has mostly been a matter of books: biographies, collected editions, contextual "interpretations" ... Watching Kenneth Branagh's absurd adaptation of As You Like It the other day on Neon, though, I was struck by just how much fun Shakespeare can be.

The play is, admittedly, a rather silly one - and Branagh's decision to set it in Meiji-era Japan made literally no sense at all - but it was all still so delightful: exiled maidens running around in drag (for no obvious reason), pinning their love poems on the poor, long-suffering trees; melancholy Jaques spouting long speeches about nothing in particular. What's not to like?

Kenneth Branagh, dir.: As You Like It (2006)

Kenneth Branagh, dir.: As You Like It (2006)It reminded me of the good old days when we used to sit down dutifully to watch each new instalment in Cedric Messina's (then Jonathan Miller's) long-running BBC Television Shakespeare (1978-85). There were some real revelations there. Who would have thought that his early Henry VI trilogy could be made into so gripping a Brechtian presentation on the roots of power? Who knew that the long-neglected Pericles could be made into such a profoundly beautiful and moving drama?

I ended up writing a poem about it, in fact:

William Shakespeare (with George Wilkins?): Pericles, Prince of Tyre (1984)

William Shakespeare (with George Wilkins?): Pericles, Prince of Tyre (1984)The Late Romances: Pericles

We have reached the 3rd Act

& Pericles

is ranting on the deck

the young Marina

lies in her mother’s arms

(still cold & dark

before revival)

which is coast

which sea?

the billows surge

up to the heavens

bodies bound below

by mortal surges

&how fares the dead?

[8/6/86]

•

What can I say? I was young at the time ...

It's easy enough to get the chance to see the great tragedies, or the Roman plays, or the Richard II / Henry IV / Henry V tetralogy, but the virtue of this BBC version was that they did everything. Timon of Athens, Cymbeline, King John - you name it, it was there. The productions were wildly various in quality, mind you. Some were pretty hard to sit through, others delightful - but they gave you a sense of what each of those 37 plays could be.

As you can guess from the above, it was the late romances - Pericles, Cymbeline, The Winter's Tale, and The Tempest - which were the real thrill for me. You see the last two performed sometimes, but hardly ever the first two.

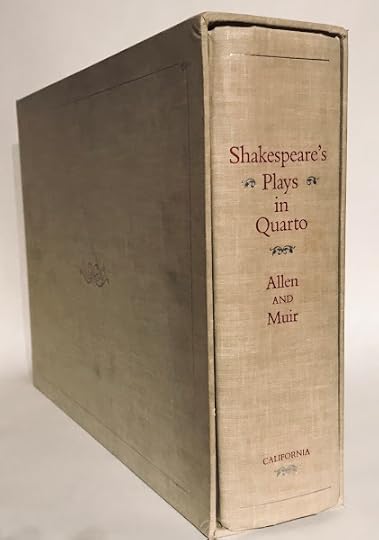

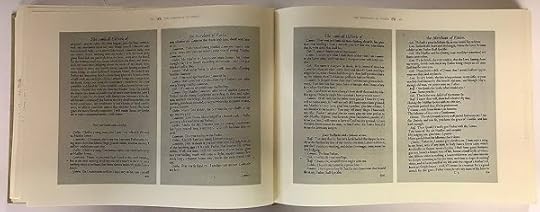

Michael J. B. Allen & Kenneth Muir, ed.: Shakespeare's Plays in Quarto (1981)

Michael J. B. Allen & Kenneth Muir, ed.: Shakespeare's Plays in Quarto (1981)I spent a good deal of time poring over the volume above in the Auckland University Library. So much time, in fact, that I eventually had to buy a copy for myself: a doorstopper if ever there was one!

Shakespeare's Plays in Quarto

Shakespeare's Plays in QuartoIt's almost unreadable, to be honest - but if you need to track some errant detail of wording, there it is.

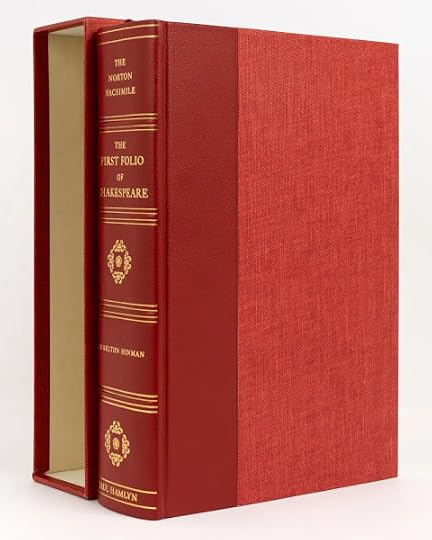

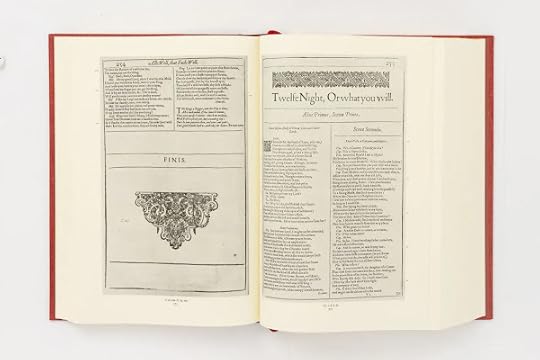

Charlton Hinman, ed.: The Norton Facsimile: The First Folio of Shakespeare (1968)

Charlton Hinman, ed.: The Norton Facsimile: The First Folio of Shakespeare (1968)The Shakespearean First Folio is a different matter. There are various facsimiles to choose from - it's unlikely that any of us will ever have the money (or the hubris) to purchase one of the few surviving copies of the original edition. You'd have to keep it in a bank vault, in any case!

The First Folio of Shakespeare

The First Folio of ShakespeareIt's a very handsome volume - colossal, yes, but clearly laid out and printed, with a host of important creative and critical issues hanging on virtually every line.

In any case, if you're looking for an absorbing way to pass a few idle hours, I'm afraid I can't recommend The World of Shakespeare. It's by far the most difficult of the puzzles we've done to date. There are few tell-tale blocks of colour once you've laid down the blue of the Thames, and a ridiculous number of tricky spires, towers, turrets, gable rooftops and leafy gardens to fill in one by one.

There's certainly some satisfaction in getting it done, but I'm afraid that it's back to the grindstone now for me - as well, I fear, as the rest of you.

•

A Happy New Year to All in

2025!

•

Published on January 06, 2025 11:59

December 24, 2024

Christmas Books = Christmas Cheer!

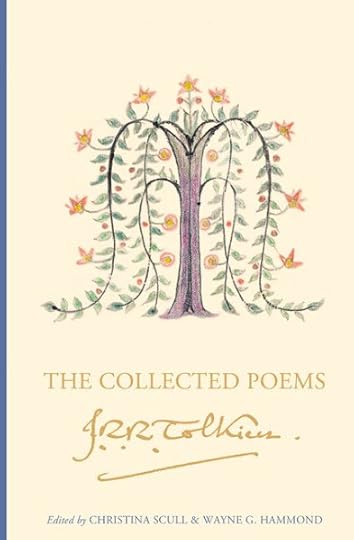

J. R. R. Tolkien: The Collected Poems (3 vols: 2024)

J. R. R. Tolkien: The Collected Poems (3 vols: 2024)Some years ago now I wrote a blogpost called "The Tolkien Industry." It seemed to cause a bit of a stir at the time, and even ended up being reprinted on the Scoop Review of Books (16/6/09).

What I thought were some fairly mild remonstrances at the relentless commercialisation of J. R. R. Tolkien's literary remains apparently touched a raw nerve in quite a few readers. A certain "Mister Lit" enquired:

... does Ross the academic subscribe to the increasingly meaningless dichotomy between ‘high’ and ‘lowbrow’ culture which sees meaningless ‘poetry’ by so-called ‘postmodernists’ studied in great depth while popular, human-oriented authors like Tolkien and Wilbur Smith are regarded as not ‘good enough’?To which I'd reply (some 16 years later): No, not then and not now. I have to say, though, that I do find the juxtaposition of Tolkien and Wilbur Smith somewhat eccentric. So far as I know, no-one's yet been tempted to publish Wilbur Smith's scribbled notes and papers in vast, annotated, scholarly editions. Perhaps it's just a matter of time, though.

The next comment, by a Henry Saltfleet, was even more indignant:

Jack Ross writes: “What’s a poor collector to do? A poor completist collector, that is.” Well, in his case I think he should get rid of his collection and take up a hobby more suited to his intellect — perhaps bowling. His main argument against newly published Tolkien material seems to be that it takes up shelf space. But what is more egregious is his underlying belief that because (for whatever reason) he isn’t interested in such material that he thinks those of us who are interested in it should be deprived of the chance to read it. Fie on him.That sideswipe at bowlers and bowling seems rather more egregious than any of my own misdeeds, I must say. What did they ever do to get dragged into this argument? Bowling is (by all accounts) a sport requiring great visual acuity and muscular skill, which puts it a fair few rungs above balancing books on shelves, I would have thought. If only I had chosen to cultivate it in my misspent youth, how much better off I would be now!

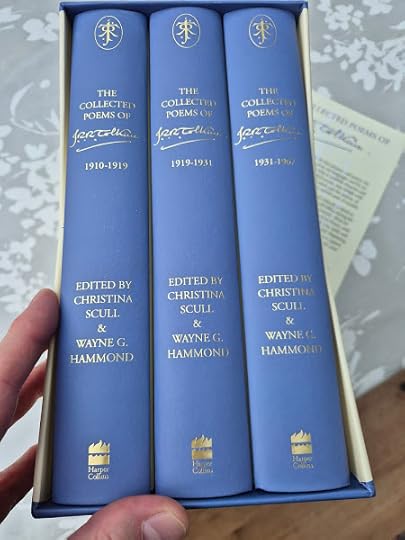

As for the rest, I think Mr. Saltfleet rather missed my point. It wasn't that this material isn't interesting - more that this piecemeal, over-annotated and commentated mode of publication doesn't really do it justice. However, my lament (in 2009) that we still lacked a decent Collected Poems for Tolkien, has finally, a decade and a half later, been met by a massive 3-volume boxed-set edition edited by Tolkienophiles extraordinaire Christina Scull and Wayne G Hammond.

WHICH I JUST GOT FOR CHRISTMAS! (all those heavy-handed hints to Santa must have paid off ...)

Christina Scull & Wayne G Hammond, ed.: The Collected Poems of J. R. R. Tolkien (3 vols: 2024)

Christina Scull & Wayne G Hammond, ed.: The Collected Poems of J. R. R. Tolkien (3 vols: 2024)"Thrills for Noddy!" - as some of the coarser denizens of my old school used to say when encountering excessive displays of enthusiam. Never mind. Damn them if they can't take a joke. It is quite a thrill - for me, at least.

•

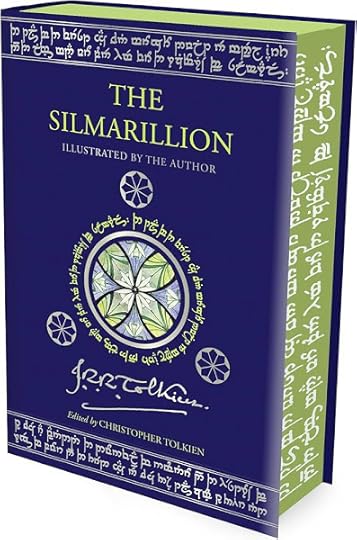

But wait, there's more. As a suitable companion volume, I'd already decided to invest in another absurdly over-elaborate piece of book design, a new edition of Tolkien's The Silmarillion illustrated by its own author!

Christopher Tolkien, ed.: The Silmarillion. Illustrated by J. R. R. Tolkien (2022)

Christopher Tolkien, ed.: The Silmarillion. Illustrated by J. R. R. Tolkien (2022)I look forward to rereading it over Summer, savouring Tolkien's clumsy daubs and line-drawings, and perhaps even comparing them from time to time to Ted Nasmith's perhaps slightly over-skilful illustrations for his own 2004 version of The Silmarillion.

J. R. R. Tolkien: The Silmarillion. Illustrated by Ted Nasmith (2004)

J. R. R. Tolkien: The Silmarillion. Illustrated by Ted Nasmith (2004)•

Curiously enough, I had much the same experience recently comparing two different illustrated texts of Tolkien's masterpiece, The Lord of the Rings.

J. R. R. Tolkien: The Lord of the Rings. Illustrated by the author (2021)

J. R. R. Tolkien: The Lord of the Rings. Illustrated by the author (2021)On the one hand, there's this sumptuous new hardback edition, with illustrations culled from the author's papers, which I purchased when it first came out in 2021. I mean, what reasonable person could resist the temptation of owning "the complete text printed in two colors, plus sprayed edges and a ribbon bookmark"?

J. R. R. Tolkien: The Lord of the Rings. Illustrated by Alan Lee (1991)

J. R. R. Tolkien: The Lord of the Rings. Illustrated by Alan Lee (1991)But then, on the other hand, there's this thirty-year old veteran I picked up second-hand a couple of months ago, with illustrations that now look rather prophetic of much of the visual imagery of the feature films.

Not, perhaps, that that's all that surprising when you consider that Alan Lee (together with Canadian illustrator John Howe) was one of the two main concept designers on The Lord of the Rings trilogy (2001-03) - as well as working on its prequel, The Hobbit (2012-14).

There's never a shortage of arguments for getting new books, unfortunately - it's persuading yourself that you can jettison some, or (better still) not buy them in the first place, which is hard.

•

J. R. R. Tolkien: The Hobbit. Illustrated by the author (2023)

J. R. R. Tolkien: The Hobbit. Illustrated by the author (2023)I'm not falling for this one, though. I can promise you that! I mean, who needs it? I already own a nice old hardback copy of the original edition, which was already "illustrated by the author":

J. R. R. Tolkien: The Hobbit (1937 / 1974)

J. R. R. Tolkien: The Hobbit (1937 / 1974)And, if that's not enough, I also have copies of the two books below which (between them) surely provide more Hobbit-iana than even the most exigent fan could require:

Douglas A. Andersen, ed.: The Annotated Hobbit (1988 / 2002)

Douglas A. Andersen, ed.: The Annotated Hobbit (1988 / 2002) John Rateliff: The History of the Hobbit (2007 / 2011)

John Rateliff: The History of the Hobbit (2007 / 2011)•

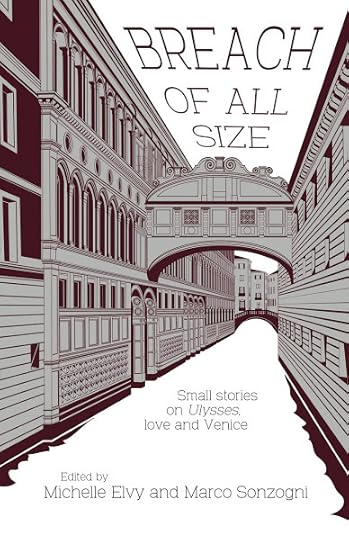

What else? Well, there's an intriguing new addition to the Heaney canon, to stand alongside Marco Sonzogni's excellent 2022 edition of The Translations of Seamus Heaney:

Christopher Reid, ed.: The Letters of Seamus Heaney (2024)

Christopher Reid, ed.: The Letters of Seamus Heaney (2024)There's also the latest Murakami novel, of which I have high hopes after a couple of duds from the Japanese literary superstar:

Haruki Murakami: The City and Its Uncertain Walls. Trans. Philip Gabriel (2023 / 2024)

Haruki Murakami: The City and Its Uncertain Walls. Trans. Philip Gabriel (2023 / 2024)•

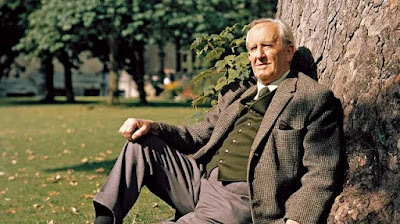

J. R. R. Tolkien (1895-1973)

J. R. R. Tolkien (1895-1973)To return to Tolkien, though ("Tollers" to his friends - just as C. S. Lewis was "Jack" and his brother Major W. H. Lewis "Warnie").

If by any chance you're still having difficulties disentangling the relationships between his various works: the two main ones published during his lifetime - The Hobbit (1937) & The Lord of the Rings (1954-55) - and that other, posthumous compilation - The Silmarillion (1977); together with its myriad supplementary texts - you could certainly do worse than have a quick squiz at the diagram below:

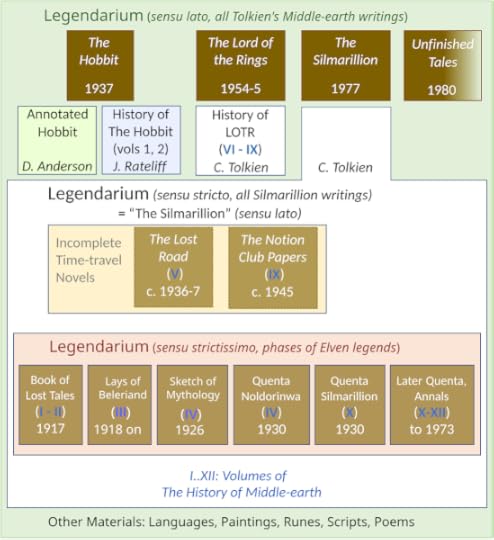

Ian Alexander: Tolkien's Legendarium (2021)

Ian Alexander: Tolkien's Legendarium (2021)Clear as crystal, wouldn't you say? In any case, this is just to wish you all a similarly

MERRY CHRISTMAS

& A Happy New Year

•

Published on December 24, 2024 13:24

December 17, 2024

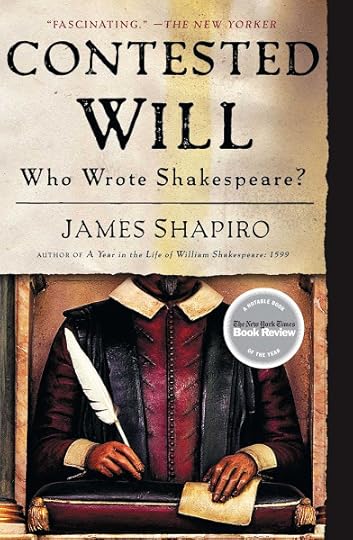

Was Shakespeare a woman?

Jodi Picoult: (2024)

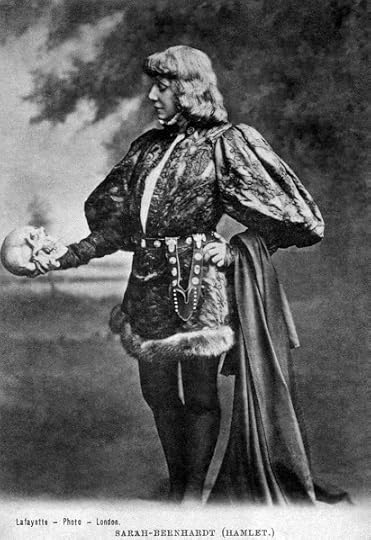

Jodi Picoult: (2024)Bronwyn's brother and sister-in-law came to visit us the other day. In the course of a very cordial - and wide-ranging - conversation, my sister-in-law asked me if I thought Shakespeare had really written the plays published under his name. I said that I did. She explained that she'd just finished reading Jodi Picoult's latest novel, which argues otherwise.

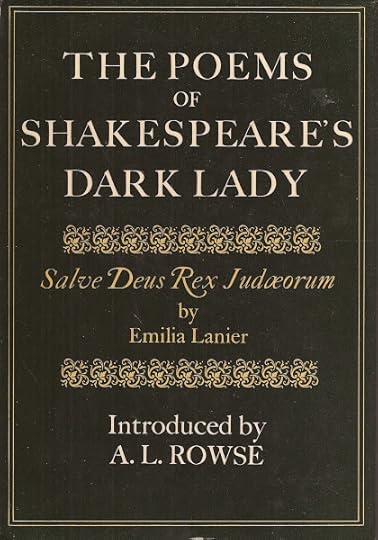

I hadn't actually heard of the novel, but what she told us about it did enable me to identify Picoult's principal candidate for authorship of the plays. In fact, I felt quite chuffed to be able to produce my own copy of the book below, A. L. Rowse's edition of The Poems of Shakespeare's Dark Lady, Emilia Lanier.

Emilia Lanier: Salve Deus Rex Judæorum (1611 / 1979)

Emilia Lanier: Salve Deus Rex Judæorum (1611 / 1979)Picoult refers to Emilia Lanier under her maiden name, Bassano, but she certainly is the lady in question.

Whether she really was Shakespeare's "dark lady" of the Sonnets, let alone the author of his plays, is of course a matter for speculation, but she was definitely "the first woman in England to assert herself as a professional poet" by publishing the volume above - surely quite an encomium in itself!

It's also, alas - in my view, at least - the biggest stumbling block to Picoult's theory. That is to say, the theory Picoult admits borrowing from journalist Elizabeth Winkler, who argued it in a 2019 essay in the Atlantic, and subsequently in her 2023 book Shakespeare Was a Woman and Other Heresies: How Doubting the Bard Became the Biggest Taboo in Literature .

This hypothesis has now earned its own Wikipedia page: "The Emilia Lanier theory of Shakespeare authorship", which traces the idea back to John Hudson's article "Amelia Bassano Lanier: A New Paradigm", in the anti-Stratfordian journal The Oxfordian, 11 (2009).

•

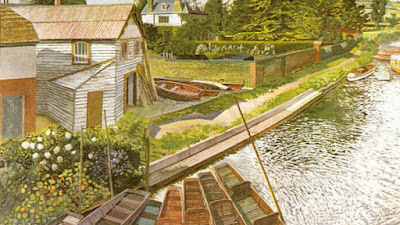

Stanley Spencer: View from Cookham Bridge (1936)

Stanley Spencer: View from Cookham Bridge (1936)Let's look at a few lines from Lanier's book, which can be found reprinted in its entirety on the Renascence Editions website. This passage is taken from the description of "Cooke-ham" which concludes her work:

It's not that these verses are bad. On the contrary, they seem to me very accomplished of their kind. They're regularly end-stopped, conventional in metre, and pious in their overall effect.

Farewell (sweet Cooke-ham) where I first obtain'd

Grace from that Grace where perfit Grace remain'd;

And where the Muses gaue their full consent,

I should haue powre the virtuous to content:

Where princely Palate will'd me to indite,

The sacred Storie of the Soules delight.

Farewell (sweet Place) where Virtue then did rest,

And all delights did harbour in her breast:

Neuer shall my sad eies againe behold

Those pleasures which my thoughts did then vnfold:

Yet you (great Lady) Mistris of that Place,

From whose desires did spring this worke of Grace;

Vouchsafe to thinke vpon those pleasures past,

As fleeting worldly Ioyes that could not last:

Or, as dimme shadowes of celestiall pleasures,

Which are desir'd aboue all earthly treasures.

The fact that the book they come from was published in 1611 does not mean that they were actually written then, but there is a sense in which they belong to a tradition of writing which predates even the first publications of - let's refer to him/her as [Shakespeare] from now on, given the identity questions which continue to bedevil ... them.

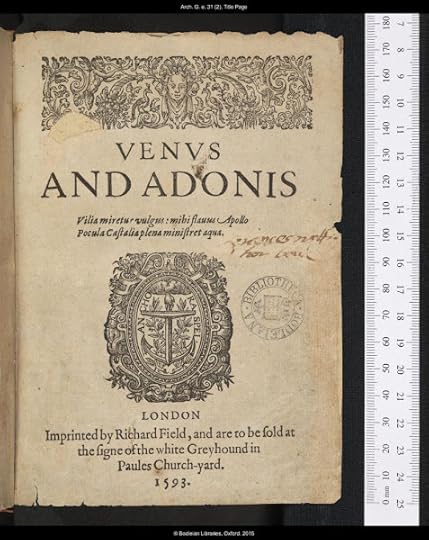

William Shakespeare: Venus and Adonis (1593)

William Shakespeare: Venus and Adonis (1593)Here are the opening lines of Venus and Adonis, first published in 1593, some twenty years before the appearance of Lanier's book:

Even as the sun with purple-colour'd faceEven in this most conventional of [Shakespeare]'s early publications - probably the closest in style to Emilia Lanier's set-piece poems - we note the rhythmic variety ("Hunting he loved, but love he laugh'd to scorn"), and galloping energy of the lines ("The field's chief flower, sweet above compare, / Stain to all nymphs, more lovely than a man"). They could, I suppose, have been written by the same hand, but it doesn't seem very likely to me.

Had ta'en his last leave of the weeping morn,

Rose-cheek'd Adonis hied him to the chase;

Hunting he loved, but love he laugh'd to scorn;

Sick-thoughted Venus makes amain unto him,

And like a bold-faced suitor 'gins to woo him.

'Thrice-fairer than myself,' thus she began,

'The field's chief flower, sweet above compare,

Stain to all nymphs, more lovely than a man,

More white and red than doves or roses are;

Nature that made thee, with herself at strife,

Saith that the world hath ending with thy life.

•

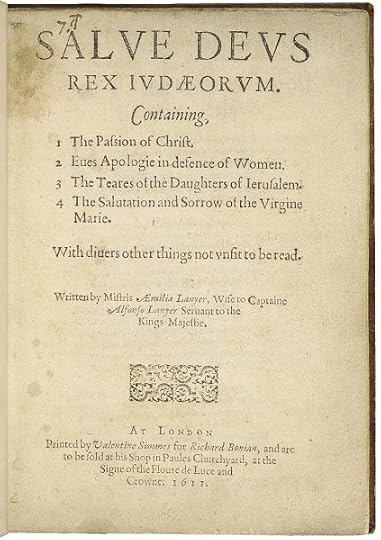

Emilia Lanier: Salve Deus Rex Judæorum (1611)

Emilia Lanier: Salve Deus Rex Judæorum (1611)Moving forward to 1611, the date of Salve Deus Rex Judæorum - what was happening in actor / producer William Shakespeare's life then? It's the year he retired from London and the life of the theatre to return to his roots in Stratford-on-Avon. So what did the writing produced by [Shakespeare] in that year sound like?

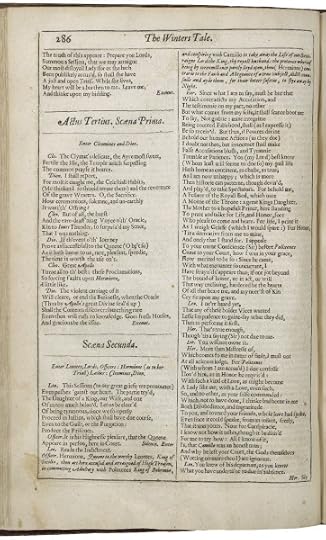

William Shakespeare: The Winter's Tale (First Folio, 1623)

William Shakespeare: The Winter's Tale (First Folio, 1623)Here's a passage from The Winter's Tale , one of [Shakespeare]'s "late Romances", which can either be seen as a retreat from the great tragedies of the early Jacobean period - or, alternatively, as a step on from them into a sense of balance and forgiveness of human frailty. The speaker here is the play's chorus, Time:

Like Emilia Lanier's poem about Cookham, this one is written in rhyming pentameters - or heroic couplets, as they're commonly known. There, however, the resemblance ends. Even at their simplest, as here, [Shakespeare]'s verses are distinguished by complex, at times almost baffling, syntax, together with flights of linguistic derring-do.

I, that please some, try all — both joy and terror

Of good and bad, that makes and unfolds error —

Now take upon me, in the name of Time,

To use my wings. Impute it not a crime

To me or my swift passage that I slide

O’er sixteen years, and leave the growth untried

Of that wide gap, since it is in my power

To o’erthrow law and in one self-born hour

To plant and o’erwhelm custom. Let me pass

The same I am ere ancient’st order was

Or what is now received. I witness to

The times that brought them in. So shall I do

To th’ freshest things now reigning, and make stale

The glistering of this present, as my tale

Now seems to it. Your patience this allowing,

I turn my glass and give my scene such growing

As you had slept between ...

Once again, it's not absolutely impossible that the author of these lines also authored the poems in Salve Deus Rex Judæorum, but if so the latter must have been early experiments - perhaps an adolescent's first attempts at formal verse. It's as close to impossible as makes no matter when you consider the sheer extent of Lanier's book, though. Who on earth would authorise such a publication at such a late stage in their literary career? And if it was unauthorised, why was she so keen to promote it?

If you have a tin ear for verse, which appears to be the case with most anti-Stratfordians (the collective noun for all the various sectaries who doubt Shakespeare was [Shakespeare] - instead favouring a bewildering list of some 80+ other candidates), I suppose that one set of heroic couplets sounds much like another. It doesn't really matter to you whether they were written by [Shakespeare], Jonson, Dryden, or even Alexander Pope. I imagine it's a bit like being tone-deaf in music.

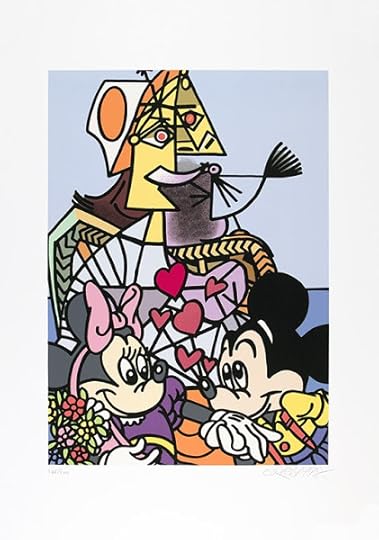

Erró: Homage to Picasso (1998)

Erró: Homage to Picasso (1998)Of course I can't simply ask you to take my word for it, but imho, it's about as likely that the poet of Salve Deus Rex Judæorum wrote the surviving corpus of [Shakespeare]'s works, as that Picasso secretly designed the early Mickey Mouse cartoons: the clash in style and tone is as blatant as that. On the one hand, Steamboat Willie ; on the other, Guernica . Both very good of their type, mind you - but, well, different.

•

William Shakespeare: The Complete Works. Ed. Gary Taylor & Stanley Wells (1986)

William Shakespeare: The Complete Works. Ed. Gary Taylor & Stanley Wells (1986)It's salutary to note, though, that even the most belaurelled experts can get it wrong. In 1986, prominent Shakespearean Gary Taylor announced his conviction that a poem ascribed to Shakespeare in a manuscript collection of verses probably written in the late 1630s was indeed an authentic addition to the canon. He and his co-editor Stanley Wells therefore decided to include "Shall I die?" in the New Oxford Shakespeare, their revisionist edition of the Complete Works of [Shakespeare].

Judge for yourself:

Whatcha reckon? I remain unconvinced, I'm afraid. If [Shakespeare] did write it, then it must have been during some drunken game of Bouts-rimés at the Mermaid Tavern. It's certainly no adjunct to the bard's diadem: 90 lines of pointless rhyming signifying next-to-nothing.

Shall I die? Shall I fly

Lover's baits and deceits

sorrow breeding?

Shall I tend? Shall I send?

Shall I sue, and not rue

my proceeding?

In all duty her beauty

Binds me her servant for ever.

If she scorn, I mourn,

I retire to despair, joining never.

[and so on in the same vein for another eight 10-line stanzas] ...

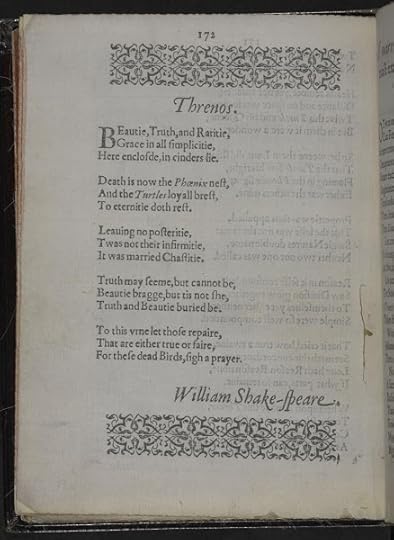

William Shakespeare: The Phoenix and the Turtle, 1601 (2nd ed., 1611)

William Shakespeare: The Phoenix and the Turtle, 1601 (2nd ed., 1611)I suppose Taylor may have been inspired by some fancied resemblance to the clearly genuine "Phoenix and the Turtle" (1601):

Once again, it's chalk and cheese, I'm afraid. [Shakespeare]'s knotty rhymes foreshadow the kinds of paradoxical reasoning familiar to us from the work of such metaphysical poets as John Donne and Andrew Marvell. The lines are both marvellously intricate in style, and deceptively complex in their implications.

Beauty, truth, and rarity,

Grace in all simplicity,

Here enclos'd, in cinders lie.

Death is now the Phoenix' nest,

And the Turtle's loyal breast

To eternity doth rest,

Leaving no posterity:

'Twas not their infirmity,

It was married chastity.

Truth may seem but cannot be;

Beauty brag but 'tis not she;

Truth and beauty buried be.

To this urn let those repair

That are either true or fair;

For these dead birds sigh a prayer.