Jack Ross's Blog, page 6

December 31, 2023

The World of Hercule Poirot

The World of Hercule Poirot

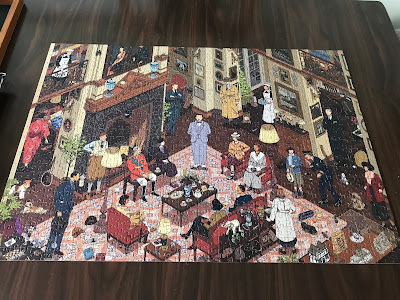

The World of Hercule Poirot[photograph: Bronwyn Lloyd (2023)]

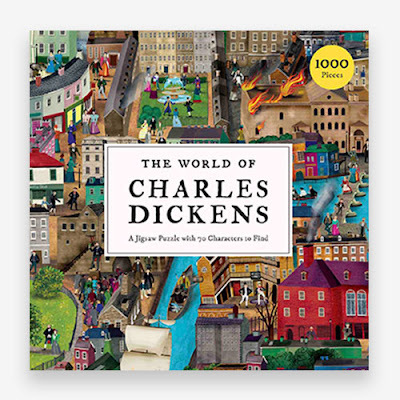

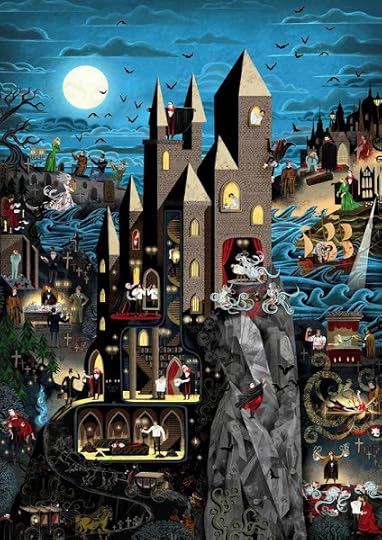

We didn't really intend to make a tradition out of it, but at the beginning of 2022 I posted a piece about a 1,000-piece jigsaw puzzle called The World of Charles Dickens ; then, in 2023, another about completing a new puzzle called The World of Dracula to usher in the New Year:

Barry Falls: The World of Charles Dickens (2021)

Barry Falls: The World of Charles Dickens (2021) Adam Simpson: The World of Dracula (2021)

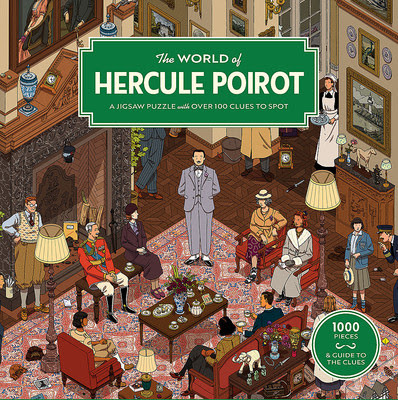

Adam Simpson: The World of Dracula (2021)This year, as you'll have gathered from the picture at the head of my post, we have the world of Agatha Christie's Hercule Poirot - and here I am starting on the task on (or about) Christmas day:

So why Poirot? I can remember a time when some people adopted a rather sneering attitude towards Agatha Christie. Not a real author, they said (whatever that means) - a mere hack, a penny-a-line writer with no real sense of style of atmosphere.

She was contrasted adversely with more self-consciously literary crime writers such as Dorothy L. Sayers and G. K. Chesterton - wordsmiths for whom detective fiction was simply a day-job, a way to finance their more artistic endeavours. How absurd - and patronising - all that sounds now!

Ilya Milstein: The World of Hercule Poirot (2023)

Ilya Milstein: The World of Hercule Poirot (2023)I guess what did it for me - and, no doubt, for many others - was David Suchet's superlative interpretation of the character in the wonderfully entertaining British TV show Poirot , which ran for a quarter of a century, from 1989 to 2013.

Poirot: 70 episodes (UK, 1989-2013)

Poirot: 70 episodes (UK, 1989-2013)I'd read a number of the books as a teenager (my father had a huge collection of them upstairs jammed onto an old wire display frame he'd liberated from a local stationery shop which was going out of business; it made a horrible graunching sound when you swung it around, so we always referred to it as 'the squeaker' ...) However, I tended to prefer such stand-alone mysteries as Crooked House (1949) and The Hound of Death (1933) to what seemed to me the more predictable puzzles of Poirot and Miss Marple (let alone the egregious Tommy and Tuppence).

Sidney Lumet, dir.: Murder on the Orient Express (1974)

Sidney Lumet, dir.: Murder on the Orient Express (1974)I did enjoy Albert Finney's interpretation of Poirot in the original 1974 movie, and (to a somewhat lesser extent) that of Peter Ustinov in Death on the Nile (1978) and its various successors. David Suchet took the character in an entirely new direction, though: away from slapstick to the intensely serious world Poirot himself inhabits.

It's not that the Suchet Poirot isn't funny - it's just that he himself is completely unaware of the fact. Ustinov, in particular, tended to play to the audience on the other side of the camera. Suchet never does that.

Kenneth Branagh, dir.: Murder on the Orient Express (2017)

Kenneth Branagh, dir.: Murder on the Orient Express (2017)Which leads us to the vexed question of Kenneth Branagh's Poirot trilogy (if it actually is a trilogy, that is - there seems little reason for him to stop at three if they're still pulling in audiences). There's no question that they're all sumptuous-looking films, with dazzling casts of A-listers.

They are awfully gloomy, though. Branagh's Poirot is constantly castigating himself for various crimes of omission (and commission), and large slabs of biography - his First World War service, for instance - have been rather awkwardly shoehorned into the original plots of the stories.

Kenneth Branagh, dir.: Death on the Nile (2022)

Kenneth Branagh, dir.: Death on the Nile (2022)It's hard not to admire the durability of stories which continue to invite this kind of reappraisal and reinvention so many years after they were written, though. The ingenuity and originality of Agatha Christie's plots continues to astonish after all this time. She was, it seems, constantly being castigated for offending against the spirit (if not the letter) of the oath sworn solemnly by members of the Detection Club:

Do you promise that your detectives shall well and truly detect the crimes presented to them using those wits which it may please you to bestow upon them and not placing reliance on nor making use of Divine Revelation, Feminine Intuition , Mumbo Jumbo, Jiggery-Pokery, Coincidence or Act of God?It was Monsignor Ronald Knox who codified these rules into a set of Ten Commandments (or Decalogue) for detective writers:

The criminal must be mentioned in the early part of the story, but must not be anyone whose thoughts the reader has been allowed to know.All supernatural or preternatural agencies are ruled out as a matter of course.Not more than one secret room or passage is allowable.No hitherto undiscovered poisons may be used, nor any appliance which will need a long scientific explanation at the end.No Chinaman must figure in the story.No accident must ever help the detective, nor must he ever have an unaccountable intuition which proves to be right.The detective himself must not commit the crime.The detective is bound to declare any clues which he may discover.The "sidekick" of the detective, the Watson, must not conceal from the reader any thoughts which pass through his mind: his intelligence must be slightly, but very slightly, below that of the average reader.Twin brothers, and doubles generally, must not appear unless we have been duly prepared for them.It was claimed - at least by some - that the central conceit of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926), where the narrator is himself the murderer [sorry for the plot spoiler for those of you who haven't read it - but it has been in the public eye for the past century, so I do feel that it's roughly equivalent with revealing that Hamlet dies at the end of the play] was not really an acceptable innovation, but with the passage of time Christie's brilliance as a fabulist is what shines out from these early novels, in particular.

Kenneth Branagh, dir.: A Haunting in Venice (2023)

Kenneth Branagh, dir.: A Haunting in Venice (2023)In any case, as the proverb has it, "the dogs bark, but the caravan travels on.' Whatever your opinion of Branagh's own innovations, the result is certainly very watchable, if a little too self-consciously Orson-Wellesian at times. In any case, it's very much in the spirit of other modern adaptations of Christie: such films as Crooked House (2017) and And Then There Were None (2015) showed that there was still lots of room for manoeuvre in these old tales.

For me, The ABC Murders (2018) went a step too far. John Malkovich's portrayal of Poirot as an aging loser suffering from depression at his failing powers was certainly original, but not precisely enchanting - if that's the right word. The joy and zest of Christie's story was lost in a morass of self-pity (together with a truly awful performance by Rupert Grint as an grim and humourless young police detective). But no doubt the book will survive it, and go on into further incarnations in the future ...

That is, if the Agatha Christie Estate can be dissuaded from rewriting all her old books in line with modern sensibilities. It's not that it's not shocking to come across the "n-" word in the original title of And Then There Were None, and the offensively racist and misogynist attitudes of many of Christie's characters might well be a stumbling block to some readers.

But Bowdlerising Shakespeare doesn't seem to have done much good in the long run: except to illustrate the absurdity of rewriting an author to fit a completely different cultural context. One of the many reasons we read is to learn about the past: how people lived, how they thought. If we try to recast them in our own (surely equally flawed?) image, then all we're really doing is adding another wing to our own hall of mirrors.

•

A Happy New Year to All in

2024!

Published on December 31, 2023 14:30

December 27, 2023

Napoleon - For and Against

Ridley Scott, dir. Napoleon (2023)

Ridley Scott, dir. Napoleon (2023)Even bad Ridley Scott movies are generally worth seeing. As he himself has remarked, "I have an eye." There are definitely ravishing moments in Napoleon, as well as any number of nods to famous pieces of Napoleonic iconography.

Ridley Scott, dir. Napoleon (2023)

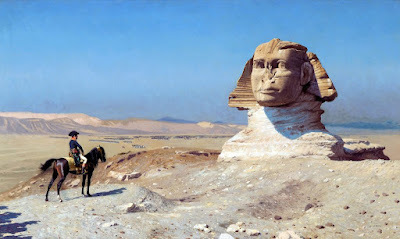

Ridley Scott, dir. Napoleon (2023)Most famously, of course, there's the above juxtaposition from the (alas, rather too short) Egyptian section of the movie, which echoes Jean-Léon Gérôme's classic late nineteenth century heroic painting:

Jean-Léon Gérôme: Bonaparte Before the Sphinx (1886)

Jean-Léon Gérôme: Bonaparte Before the Sphinx (1886)Is it a bad film, though? The question is a complex one. Earlier this year I wrote a long blogpost about the (so-called) "Man of Destiny" on my bibliography blog.

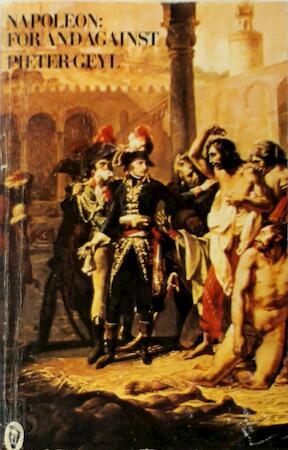

Pieter Geyl: Napoleon: For and Against (1949)

Pieter Geyl: Napoleon: For and Against (1949)I used there as my leit-motif there Dutch historian Pieter Geyl's classic analysis of Napoleonic historiography early and late. Written shortly after the Second World War, the inevitable comparison with a more recent charismatic dictator inevitably arose:

The case of the persecution of the Jews remains singular: for the rest we must be alive to the fact, when we compare them then and now, that although there is a difference in degree, there is none in principle.

Ridley Scott, dir. Napoleon (2023)

Ridley Scott, dir. Napoleon (2023)Recently I've been indulging myself by reading through English novelist Fanny Burney's letters and diaries, which cover the whole period of the Napoleonic wars - as well as their aftermath, the "White Terror" of the restored Bourbon regime.

Fanny was an almost grovellingly loyal admirer of the English Royal Family, whom she served as assistant Mistress of the Robes in the mid-1790s (interestingly, the period of George III's first madness). Subsequently she lived from almost ten years in France with her husband, Royalist general Alexandre d'Arblay, between 1802 and 1812.

Her testimony, then, while undoubtedly partisan, cannot be faulted for its quality of personal witness. Her defence of the systematic programme of executions which began immediately after Napoleon's final defeat at Waterloo, does, however, seem a little tone-deaf, to say the least:

Once restored to its rightful monarch, all foreign interference was at an end. Having been seated on the throne by the nation, and having never abdicated, though he had been chased by rebellion from his kingdom, [Louis XVIII] had never forfeited his privilege to judge which of his subjects were still included in his original amnesty, and which had incurred the penalty or chances of being tried by the laws of the land - and by them, not by royal decree, condemned or acquitted.As Fanny's Victorian editor reminds us, this rather chilling passage was written à propos of a daring attempt by three Englishmen to smuggle a French diplomat, condemned to death by the Bourbons, out of jail:

His wife implored the king's mercy in vain, Lavalette was confined in the Conciergerie, and December 21, 1815, was the day fixed for his execution. The evening before that day his wife visited him in the prison. He exchanged clothes with her, and thus disguised, succeeded in making his escape. His safety was secured by three English gentlemen, one of whom, Sir Robert Wilson, conveyed Lavalette, in the disguise of an English officer, across the Belgian frontier. For this generous act the three Englishmen were tried in Paris, and sentenced, each, to three months' imprisonment.It's as well to bear this in mind when condemning the undoubted brutality and cruelty of Napoleon's wars. It's not as if the realms and rulers he displaced were models of compassion and probity. The imposition of the Code Napoléon on so many conquered regions was literally the first glimpse many of their inhabitants had ever had of legal process and the rights of man.

No wonder Fanny Burney and her like were so anxious to restore a system which guaranteed the subordination of the many to the luxurious lifestyles of the few.

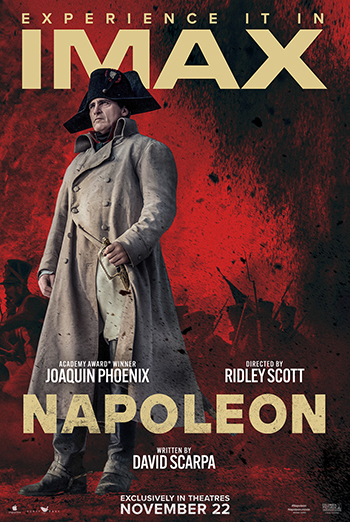

Joaquin Phoenix as Napoleon

Joaquin Phoenix as NapoleonHowever, while there may be a good deal to say in defence of Napoleon himself, what about Ridley Scott's movie? I was reading Michael Sullivan's enticingly titled article "" this morning: Napoleon clocks in at no. 15, with an explanatory quote from film critic Ann Hornaday:

The biggest flaw in Napoleon, it turns out, is the actor who plays him. It's difficult to understand why [Ridley] Scott would cast Joaquin Phoenix - one of the most subtle, recessive, almost fey actors working today - to play someone with such a commanding temperament.There's something in that, I'm afraid. Phoenix was brilliant as the Joker, and as the evil emperor Commodus in Gladiator, but he lacks the epic intensity of a Russell Crowe or a Harrison Ford. He behaves more like a sleepwalker than a man of destiny: so childishly pleased by the adulation of the midshipmen on the British ship he ends up on at the end of the bio-pic that any remaining doubts he might be feeling over Waterloo seem quite submerged.

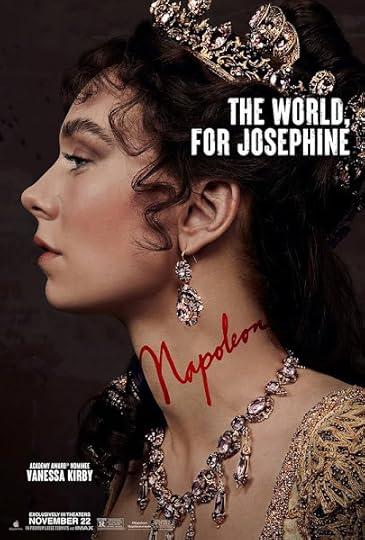

Vanessa Kirby as Josephine

Vanessa Kirby as JosephineI would be interested to see the four-hour 'director's cut' we've been promised at some point in the future, but it's doubtful whether this central piece of miscasting can really be overcome no matter how conscientiously the rest of the action - and characterisation - is filled in.

All in all, Scott's film leaves one wishing that Stanley Kubrick had lived to complete his own big screen epic about the Emperor. The one thing I'm genuinely thankful for is that they didn't cast Adam Driver. He seems to star in every other film nowadays, and it's a relief that he must have been otherwise occupied at the time chasing dinosaurs in the singularly charmless 65 ...

Scott Beck & Bryan Woods, dir.: 65 (2023)

Scott Beck & Bryan Woods, dir.: 65 (2023)

Published on December 27, 2023 12:05

October 14, 2023

Slightly Foxed (b.o.f.)

John Fenton. Slightly Foxed b.o.f. [= but otherwise fine]. Auckland: John Denny, 1997.

I once belonged to a secret society.

It wasn’t especially secret – just a group of book enthusiasts who met once every month at the Kinder House in Auckland to jaw about their latest finds. It was called “Slightly Foxed.”

I first found out about it during a last-minute Christmas shopping spree. I’d just located a facsimile edition of Shackleton’s Terra Australis journal to give to my father, when I got to chatting to the salesman behind the desk.

He was quite a young guy, but very eager to talk – some relief from the surging crowds in Whitcoull’s basement, I suppose. When I admitted I was a bit sorry to give away such a prize rather than keeping it for myself, he urged to buy another copy. “Go on, you know you want to.”

Then we started skiting about how many books we respectively owned. Then onto this strange little club he apparently belonged to, and the respective tastes of its various members. One, I recall, was an enthusiast for the works of John Cowper Powys, but (as my new friend remarked) his own attitude to that author was “why use one word when ten will do?”

Having been a card-carrying Powysian since my teens, I vigorously demurred, and so it went on. It took me quite some time to extricate myself from there, but I have to say that the whole exchange remains quite vivid in my mind.

I never saw him again.

When I mentioned this “Slightly Foxed” group to a friend of mine, Murray Beasley, back at Auckland University, where we were both teaching at the time, he said that he had once attended a meeting of theirs, had a good time, but never been invited back. “It wasn’t really clear what the set-up was. Did one have to be shoulder-tapped? Were they judging the cut of my jib? Or should I simply have … turned up?”

A few years later, back in Auckland from a sojourn abroad, another friend, Kate Stone, asked me along to a meeting. She, it seemed, was a regular attendee, and knew all the regulars.

It was odd. From my long-ago conversation with the chap in the bookshop, I’d imagined something terribly high-powered: erudite discussions of colophons and signatures; all that bibliographical panoply I’d so eagerly tried to master in my years away at the University of Edinburgh.

Not so. The first time I attended the talk was (I think) entitled “Books on Waiheke,” and featured an old cloth bag containing various random finds obtained from the stalls and bookshops on the island, with desultory discussion of how much (or little) they’d cost. Hobbyist rather than serious collector talk.

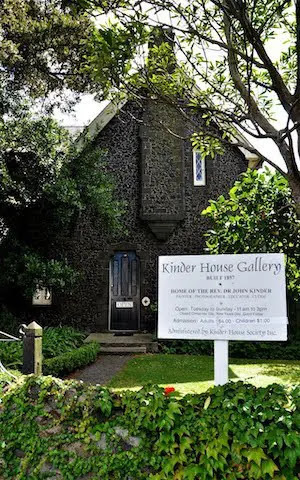

The Kinder House (Parnell, Auckland)

The Kinder House (Parnell, Auckland)But I was lonely, and it was a chance to get out and about, and the Kinder House was quite an atmospheric place to sit on a dark winter evening, with books on the table and mulled wine in one’s glass. So even when Kate stopped attending regularly, I kept on going along. I’d got on the mailing list somehow, so I suppose I had been shoulder-tapped, if such rituals ever actually took place. The whole thing was so informal, really, that it seemed impossible to imagine that there could have been that many obstacles to another person filling a chair.

The members were certainly both various and interesting. The oldest and most eminent was undoubtedly Ron Holloway, famous for printing so many New Zealand classics at his Griffin Press in the 1930s and 40s. He was pretty deaf, and seldom (if ever) took part in the discussions.

Then there was John Denny, a far younger, far more onto-it artisanal printer. He remains a friend. But the heart and soul of the group, so far as I was concerned, was John Fenton. A generous and clubbable man, interested in all aspects of the bookish game, especially Beat poetry and Jazz. It was he who wrote the society's history, pictured above - and, yes, that club logo on the cover was contributed by the great Ronald Searle!

Who else? Let's see - there was David Greeney, who'd had a career working in the publishing trade, and who knew it inside out as a result; there were Jan & Peter Riddick, a canny pair of local environmentalists; then there was the printer Ken Wood, who had a passion for collecting the same number from each numbered, limited edition he encountered. He must have had a magnificent collection even then!

1997 - (24 September) “The Thousand and One Nights.”1998 - (18 March) “Kendrick Smithyman.”1998 - (10 June) “Maxim Gorky” [with Bruce Grenville]1999 - (1 September) “Mikhail Lermontov” [with Bruce Grenville]2000 - (19 July) “Henry James.”2001 - (21 March) “Antarctica.”2001 - (19 September) “Edgar Allan Poe.”2002 - (24 April) “Shakespeare.”

Probably the most successful of these - from the point of view of the other members, at any rate - were the ones where fellow-member Bruce Grenville, the (self-styled) Sultan of Occussi-Ambeno, showed a film from his massive collection of old celluloid – much of it inherited from the defunct stores of the Soviet embassy – while I talked about the life and works of the author concerned.

It was Bruce who contributed indirectly to my exit from the society, in fact. At one of the last of these talks – I think probably the one on Edgar Allan Poe – he got into an argument with the club’s president, and the two of them almost came to blows.

“If this continues, I’m out of here.” I proclaimed. There was no pleasure to be found in sitting at a table with these two gentlemen sniping at each other, and I think I came back just once after that, to give one last talk on Shakespeare.

I still run into old “Slightly Foxed” alumni, though, some twenty years on. I met up with John Fenton again recently, and he tells me that the society has, in fact, folded - but then he would say that, wouldn't he? Perhaps it still continues in some clandestine form.

To be honest, more of my energies were directed into writing groups by then: first the (so-called) “Bookshop Poets,” who met at Lee Dowrick’s house in Devonport; and subsequently the “Eye Street Poets,” who gathered at Raewyn Alexander’s place in Western Springs. I rather miss those convivial gatherings, too.

•

Published on October 14, 2023 13:00

October 10, 2023

Memories of Don Smith

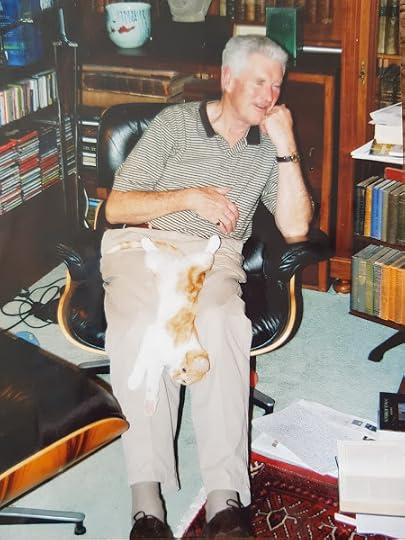

D. I. B. Smith (1934-2023)

D. I. B. Smith (1934-2023)[photograph courtesy of Caitlin Smith]

i. m. Emeritus Professor Donal Ian Brice Smith

(4/2/1934 - 27/9/2023)

I don't think I ever had a conversation with Don Smith which didn't end in some interesting book recommendation - or else a new insight into a long-beloved classic. He was the first Academic I ever met who seemed to be driven solely by a love for books and reading in general. "Great stuff!" he would intone, as he leafed through another shabby-looking prize from the second-hand bookshops downtown.

I was somewhat in awe of him to start with - and for quite a long time after that. I had, for some unaccountable reason, decided in the early 1980s that it was up to me to reclaim from oblivion the long-neglected novels of British Poet Laureate John Masefield by composing a Master's thesis about them.

Constance Babington Smith: John Masefield: A Life (1978)

Constance Babington Smith: John Masefield: A Life (1978)"How many novels did he actually write?" asked one of the prospective supervisors I approached. "Twenty-three," I replied. "And how many of them have you read?" "Twenty-three." Strangely enough, that particular prospect discovered he had urgent duties elsewhere and could not accept a new research student at that time ...

Don - or 'Professor Smith', as I continued to address him till long after I had ceased to be his student - actually was far too busy to take me on. He was, after all, Head of Department at the time. But when I went to see him about it, he said that he would do it - but only if nobody else was able to.

Which left me with the somewhat invidious task of visiting each and every one of the Academics in the of the University of Auckland English Department who might conceivably be interested in such a project. It was certainly very educational to sample the variety of excuses they came up with - from the straight 'no' to the 'maybe some other time' to the 'perhaps if you changed it to ... [something quite unrelated].'

But no, I was - no doubt foolishly - quite determined, so I eventually made my way back to Don's door, and to his somewhat reluctant oversight ...

How did he approach it? He sat there and talked, while I took notes. His talk ranged over many subjects, some relevant and others perhaps not quite so relevant. At the time I recall he was reading the work of Anglo-Irish writer Shane Leslie - who was pretty obscure even by my standards - as well as working on some of the lesser known novels of Ezra Pound's early mentor (and Joseph Conrad's collaborator) Ford Madox Ford.

Was any of this relevant to Masefield? Well, in a curious way, as it turned out, yes. The interface between the 'commercial' and the 'literary' faces of Edwardian literature fitted rather nicely into studying the work of a poet, Masefield, who was publishing at the same time as Eliot and Pound, but inhabited a world almost literally invisible to their admirers. Ford was a good example of the same phenomenon, though in a rather different way.

Andrew Marvell: The Rehearsal Transpros'd, ed. D. I. B. Smith (1971)

Andrew Marvell: The Rehearsal Transpros'd, ed. D. I. B. Smith (1971)Don's original field of specialisation had been seventeenth century literature. He'd published an edition of Andrew Marvell's satirical prose work The Rehearsal Transpros'd in the Oxford English Texts series. When I asked him about this, he said, "Well, it got me this job." What he seemed to like most, though, was exploring the more offbeat byways of Anglo-Irish literature - not to mention New Zealand writers such as Robin Hyde: far less well-known then than she is now.

Robin Hyde: Passport to Hell, ed. D. I. B. Smith (1986)

Robin Hyde: Passport to Hell, ed. D. I. B. Smith (1986)The more I heard from him, the more I liked it. I'd been trained in my undergraduate career to admire such extreme Modernists as Eliot and Joyce, and this (still) makes perfect sense to me. On the other hand, there was a rich penumbra of weirdos such as Chesterton and de la Mare, whom I liked just as much, but whom I'd been encouraged to dismiss as dead ends in the grand obstacle race of literary innovation.

Don wasn't interested in any of that survival-of-the-fittest nonsense. Is it enjoyable? was his central criterion for a book. Yes, he was certainly interested in the finesse and skill behind particular pieces of writing, but he still seemed to steer instinctively towards the anecdotal and - above all - towards enthusiasm in his approach to what he read.

I resolved to do likewise, and so, much later, when I in my turn became an English Academic with my own graduate students, I tried to give them as much as possible of the same formula: Read the book, not - till much later - the secondary literature about it. If you don't like it, acknowledge the fact - but then try and work out why.

It is, I suppose, an approach designed to produce readers, not students or teachers of literature. But then, if you don't actually get a kick out of the stuff you read, you probably shouldn't be teaching the subject in the first place.

That was the first - and probably the most important - of my many, many debts to Don.

Most prominent among the others would have to be the innumerable letters of recommendation he wrote for me while I was undertaking my long and arduous quest for an actual job in the fields of Academia. Once again, I've tried to follow his good example when asked to do the same thing for my ex-students.

But then I could never have got that far in the first place if I hadn't got a scholarship to study overseas, and I doubt very much that that would have happened without his powerful advocacy.

Roger Elwood, ed.: The Many Worlds of Andre Norton (1974)

Roger Elwood, ed.: The Many Worlds of Andre Norton (1974)What else? Well, after he retired, I visited him a few times at his wonderful house in Mission Bay, and admired the cupboard where he kept his very extensive collection of Sci-fi and Fantasy literature. That was another subject on which we saw eye to eye (for the most part). He had what seemed to me an inexplicable enthusiasm for Andre Norton, whereas I was more attuned to Philip K. Dick and Samuel R. Delany, but there was generally some new fantasy epic he'd been reading which I ended up making a mental note to get hold of as soon as I could.

He made all them sound like so much fun - though he did stray into heresy on one occasion, I recall, by claiming to prefer Tad Williams to J. R. R. Tolkien as a writer of epic fantasy. This was, as I solemnly informed him, a little like preferring some latter-day SF luminary to Arthur C. Clarke - if they're able to see further, it's because they're standing on giant shoulders ...

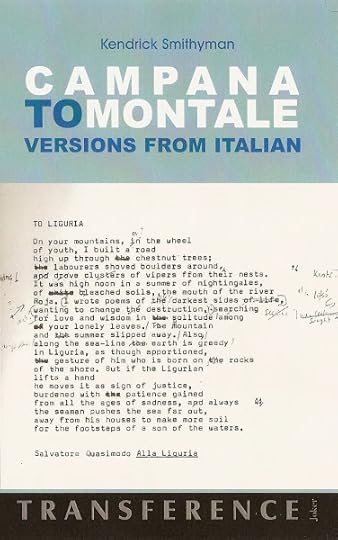

Kendrick Smithyman: Campana to Montale, ed. Jack Ross (2004)

Kendrick Smithyman: Campana to Montale, ed. Jack Ross (2004)He knew I was passionate about the poetry of our Auckland University colleague , and since Don and I could both read Italian, he lent me the typescript of some versions the monolingual Smithyman had concocted of certain modern Italian poets through the medium of other people's translations.

That, too, was a precious gift. I ended up editing and publishing the entire collection, which still seems to me - like Pound's Cathay - to prove that the end result of a process of translation counts for far more than the way that a writer actually gets there. Kendrick's versions from Italian have a supple ease and charm which far better linguists than he have tried in vain to achieve - and, in the process, he found in the poet Salvatore Quasimodo a virtual alter ego.

Kendrick Smithyman: Campana to Montale, ed. Jack Ross & Marco Sonzogni (2010)

Kendrick Smithyman: Campana to Montale, ed. Jack Ross & Marco Sonzogni (2010)I was also presumptuous enough to ask Don to launch my first novel, Nights with Giordano Bruno , which he did with great style and panache. I remember he compared it to Mario Praz's famous critical book The Romantic Agony, which is, I'm sure, far more credit than it deserved. It was characteristic of his ready wit as well as his charity, though.

Another of my favourite memories of him is the time he hunted me down at my student lodgings in Edinburgh and took me out to dinner at a local tratteria called Pinocchio's. It was wonderful to see him en famille, with his wife Jill and daughter Caitlin, and - as I recall - a great deal of red wine was drunk and pasta eaten in the course of the evening!

As Stephen King's writer hero says of his friend in the movie Stand by Me: "I'll miss him forever." That's certainly true. I'd love to have another of those wonderful, unexpected conversations where Don Smith turned all my prejudices and presuppositions on their heads. But in another, realer sense he's not dead - he'll never be dead.

I can hear him now saying "Great stuff" and reading out another passage from his latest essay, where he juxtaposes a quote from Ford Madox Ford about his latest drivelly historical romance The Young Lovell with another precisely contemporary set of Fordian instructions on how to be absolutely modern to his errant young protégé Ezra Pound ...

Notes:

You can find them all listed here, at https://madbookcollection.blogspot.com/2009/04/acquisitions-86-john-masefield.html - if you're curious.

Arthur Rimbaud, "Il faut être absolument moderne." Une Saison en enfer (1873). Pound said of Ford Madox Ford in his 1939 obituary:[H]e felt the errors of contemporary style to the point of rolling (physically, and if you look at it as mere snob, ridiculously) on the floor of his temporary quarters in Giessen when my third volume displayed me trapped, fly-papered, gummed and strapped down in a jejune provincial effort to learn ... the stilted language that then passed for 'good English' ...

And that roll saved me two years, perhaps more. It sent me back to my own proper effort, namely, toward using the living tongue ... though none of us has found a more natural language than Ford did.

Don, Caitlin, & Jill Smith

Don, Caitlin, & Jill Smith[photograph courtesy of Caitlin Smith]

•

Published on October 10, 2023 12:14

September 29, 2023

Mike Johnson Triple Booklaunch (5/10/23)

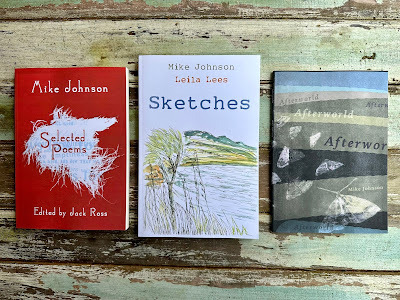

Mike Johnson: Selected Poems, ed. Jack Ross (2023)

Mike Johnson: Selected Poems, ed. Jack Ross (2023) Mike Johnson & Leila Lees: Sketches (2023)

Mike Johnson & Leila Lees: Sketches (2023) Mike Johnson: Afterworld (2023)

Mike Johnson: Afterworld (2023)Mike Johnson:

Afterworld / Sketches / Selected Poems

Celebrated New Zealand novelist and poet Mike Johnson is having a triple booklaunch on Waiheke Island, where he lives, on Thursday next week. This biblioblitz of material includes a new novella, a new book of poems, and a substantial Selected Poems (edited by yours truly), sampling from his work in that medium over the last four decades.

Unfortunately I'm unable to be there, but I'm sure it will be a riproaring event - Murray Edmond will be launching the novella, and there will be discussion and readings from Mike and his collaborator Leila Lees, as well.

The details are as follows:

Afterworld, a novella, will be launched on Oct 5th, 6.30 – 7.30 pm, Waiheke Library, 133/131 Ocean View Road, Oneroa, part of our triple book launch which also includes Sketches, with Leila Lees, and Selected Poems edited by Jack Ross.

Afterworld is a novella length work of magical realism with a whodunit element. The plot follows a ghost who ends up in a hut on a New Zealand mountain. As the ghost seeks to understand their life and death, fragments of their past are remembered. Contending identities, times and events emerge.

Sketches contains lines caught on the fly. Poems which capture and celebrate the momentary, provisional nature of existence. Here we find the natural world, and matters of the heart, caught as they happen in language both natural and precise. They are beautifully complemented by the drawing and sketches of Leila Lees.

‘The immense complexity of human relationships, social, sexual and everyday are at the heart of much of Mike’s best poetry. However, there’s an almost equal pull towards the empyrean: the cosmic mysteries of nature and the visible world.' - Jack Ross, editor of Mike Johnson's Selected Poems (1983-2023).

Where: Waiheke Library, 133/131 Ocean View Road, Oneroa

When: Thursday 5 October, 6.30 to 7:30 pm

Mike Johnson: Three Books (21/8/23)

Mike Johnson: Three Books (21/8/23)Mike himself comments:

I'm excited to have three new books to launch. These projects came together at the same time.

Sketches – Facebook readers might remember the Wednesday Poems that ran from June 2019 to June 2021, accompanied by Leila Lees' illustrations.

Afterworld – A novella which was also posted on Facebook, over 21 posts and finishing on Oct 19th 2022. Here it is thoroughly revised.

Selected Poems – Edited by Jack Ross, a selection of my poems since 1983, including Sketches.

NB: For further information, please go here

•

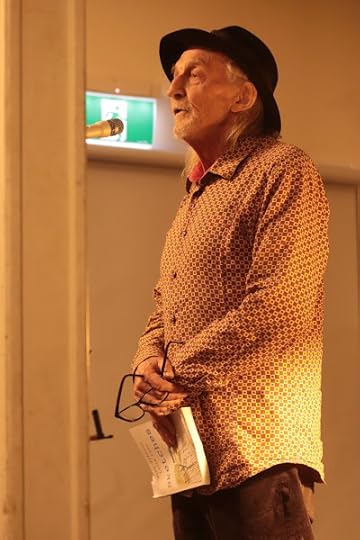

Katy Soljak: Mike Johnson (27/9/23)

Katy Soljak: Mike Johnson (27/9/23)

Published on September 29, 2023 13:14

September 11, 2023

PhD Days

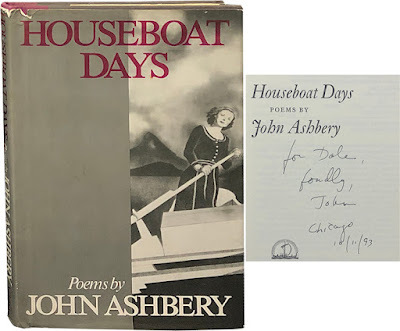

John Ashbery: Houseboat Days (1977)

John Ashbery: Houseboat Days (1977)Despite all he did and wrote subsequently, I'm still probably most fond of John Ashbery's rather dreamy poetry collection Houseboat Days , published shortly after his Pulitzer-prize winning Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror:

The mindIn this case, as my last PhD student completes her oral examination, it's interesting (for me, at least) to look back over more than thirty years of involvement with the institution - or the qualification - or whatever exactly it is ...

Is so hospitable, taking in everything

Like boarders, and you don’t see until

It’s all over how little there was to learn

Once the stench of knowledge has dissipated

At times it feels more like a lifestyle choice than anything else.

•

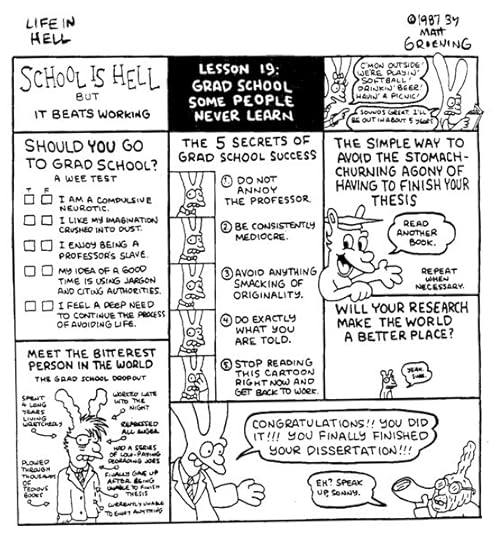

Matt Groening: Life in Hell (1987)

The cartoon above - by Simpsons-creator Matt Groening - may strike you as a little cynical, but it does seem like a good place to start when discussing my own engagement with the degree we call the "Doctorate in Philosophy": both the one I did myself (University of Edinburgh - 4 years: 1986-1990), and my subsequent experiences as supervisor / co-supervisor of dozen-odd more (Massey University - 15 years: 2008-2023).

Not only that, but I also acted as the examiner of another ten or so (Australia & NZ - 13 years: 2008-2021), which entailed reading and annotating each thesis, writing a comprehensive report on it, and - in most cases - attending an oral exam (what used to be called a "viva voce" [with the living voice], but is now usually shortened to a viva).

Rather than Groening's "life in hell", though, I'd prefer to see it as something more akin to Ashbery's poetry collection: a strange, kaleidoscopic drift through the bazaar of world culture, albeit with an at times disproportionate emphasis on gamesmanship and the arbitrariness of academic conventions - rather like the rules of metre and rhyme, I suppose: there to be broken.

Houseboat DaysIn my dream I was talkingto a group of studentsabout the genesisof Poetry NZback in the dayin Palmerston NorthI asked them to write me a haiku – making sure they knewwhat that was –then collected all their emailsfor next timeso loud was the dinof the next classinvadingI could hardly hear myself thinklet alone make out the crabbed scrawlon the notes they gave meI suppose it’s a reactionto hearing of Bronwyn’s workmatewhowhen told we were going to see Emilyasked who’s Emily Brontë?have I started teaching againin my dreams?a relief then to be woken by clattering dishesthis morningthe old life done

•

Illusion and Reality

Doctoral Catechism:

What exactly is a PhD?

Well, Wikipedia, as ever, provides a wealth of information on the subject:

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, Ph.D., or DPhil; Latin: philosophiae doctor or doctor philosophiae) is the most common degree at the highest academic level, awarded following a course of study and research. PhDs are awarded for programs across the whole breadth of academic fields.How do you get one?

Because it is an earned research degree, those studying for a PhD are required to produce original research that expands the boundaries of knowledge, normally in the form of a dissertation, and defend their work before a panel of other experts in the field.That point about an "original contribution to knowledge" is the crucial factor here. A Masters degree in any subject also - often - requires a thesis, but this can be a summary of other people's work in the field: it doesn't have to (though it certainly can) make an original contribution to the field.

Why do people do them?

The completion of a PhD is typically required for employment as a university professor, researcher, or scientist in many fields. Individuals who have earned the Doctor of Philosophy degree use the title Doctor (often abbreviated "Dr" or "Dr."), although the etiquette associated with this usage may be subject to the professional ethics of the particular scholarly field, culture, or society.In my experience, insisting on the title "Doctor" in casual conversation generally causes more trouble than it's worth. Most people - quite rightly - associate the term solely with a medical qualification, so explaining that your expertise in (say) literary criticism doesn't really extend to offering them health advice is a bit of a waste of everyone's time.

How long does it take?

In the New Zealand Academic system, still mostly based on the British model, it will probably - depending on your field and the topic you've chosen - take you at least three or four years. It's extremely rare to finish under three years. It's pretty common to go over four years, in fact, though these days institutions are trying very hard to discourage indefinitely protracted Doctoral research projects.

In the American system, which harks back more to the Germanic paradigm, I gather it can take from five to seven years to achieve much the same end (I myself did mine in the UK, so that's not something I can testify to personally). In the USA a substantial amount of course work needs to be completed, over a period of years, before you can even start on your dissertation. In the UK, NZ and other Commonwealth countries, by contrast, the initial preparation and the composition of the thesis are all one journey.

Is it expensive?

Doctoral scholarships are increasingly difficult to get. There's a good deal of competition in virtually every field, and very few of them will fund you completely for the entire length of your degree. Even getting admitted to a Doctoral programme can be hard sometimes. Unless you got Honours in your Masters degree, or have a very strong professional background in your area of study which can be regarded as equivalent, you may not be allowed to enrol at some institutions. It simply isn't true that tertiary institutions are only interested in the fees students pay them. They're far more interested in results: which in this case means successful completions.

I've successfully supervised (or co-supervised) six PhDs now. But I've started on at least six other supervisions which were unsuccessful for one reason or another. For the most part people drop out of their Doctoral programmes for personal reasons. It can take a heavy toll on your personal life, as well as your finances. Sometimes, too, there are clashes of personality or expectations, which can entail the student switching to another supervisor or even another institution. But all that really matters is that holy grail of successful completion.

Should I do one myself?

Not until you've thought through all the pros and cons associated. Do you have a research project in mind which can only really be accomplished with institutional support and advice? If so, then yes indeed, it could be a good fit for you.

Or, if you have a strong desire to work as a university teacher, Academic institutions increasingly require a PhD as a minimum qualification for appointment. So in that case, again, yes - it's your best way forward, and you can probably pick up some tutoring along the way which will increase your professional experience and thus your eventual job prospects.

If, however, there's a subject which really interests you, and which you are already researching already on your own time, with your own resources (online sources, the public library, etc.), it's worth asking yourself whether it might not be better simply to write an article - or even a book - on the subject and eliminate the middleman?

The university will certainly charge you for any professional advice they offer. And if you don't really need that for this particular project, why not just try approaching some publishers yourself? It's where you'll probably end up at the culmination of your degree, so you have to be very sure that that end result is a lot better than it would have been if you'd simply followed your own star.

•

PhD = Time Served

My God, these cartoonists! It may seem at times as if everyone's trying to talk the qualification down, but I don't think that's really the case. As with any obsession, you have to try to see the dark and light of it when you're trying to convey what it's actually like.

The theses I read as an examiner included topics as various as Jorge Luis Borges' relationship to the Pragmatism of William James, Children’s Fantasy Fiction, Indonesian Postcolonial Politics, Contemporary Scottish Writing, the Semiotics of Modern Poetry, Australian Settler Fiction, the Poetics of Joan Retallack, Pasifikafuturism, New Zealand Local History, and the Poetics of Photographic Ekphrasis.

Do I know much about any of those subjects? Well, some of them, yes. I wrote my own thesis, back in the 1980s, on South American literature, so Borges was pretty familiar to me - as (by extension) was the question of Postcolonial representation in general. Some of the others I learnt about just by reading the dissertations. My job was to judge how effectively they communicated the specialised information each of them contained - and the cogency of the writer's overall argument.

It's a bit different from just reading a book on some subject you'd like to more about - different even from writing a book review. Examining a thesis involves grappling with a topic to which someone has devoted years and years of careful and painstaking labour. You have to treat that with respect, but not to the extent of refusing to identify flaws in the work as it stands.

What about the ones I supervised myself? Again, not all of them were on subjects I knew well going in - though of course they did have to be in the general field of creative writing and literary criticism which were my professional area of teaching and study. I won't go through them all, but suffice it to say that each one of them was an education in some very precise field of research.

•

Matt Groening: The Grad School Dropout (1987)

Matt Groening: The Grad School Dropout (1987)I do not know what I may appear to the world, but to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the seashore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.- Isaac NewtonPerhaps this quote from Newton is a better way to think about it than the mordant sarcasms of Matt Groening et al. I know it's absurd to compare myself to the founder of Modern Physics, but no matter where you're starting from, you can always improve on your own state of ignorance. My own blindness before what he calls "the great ocean of truth" may be far greater than his, but that doesn't mean that I'm not just as keen to learn.

So, no, true though it undoubtedly is in some cases, the above is definitely not the whole picture. It's a useful warning to keep in mind - but, as the saying has it, verbum sapienti sat est [a word to the wise is sufficient].

•

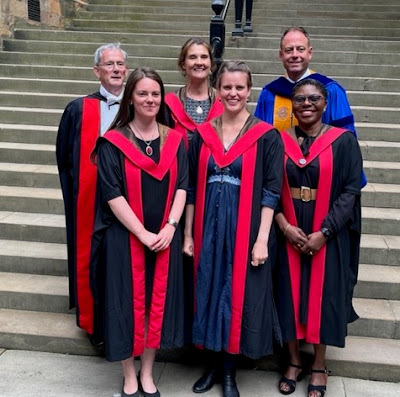

University of Edinburgh: PhD Graduands (2022)

University of Edinburgh: PhD Graduands (2022)

Published on September 11, 2023 12:43

August 4, 2023

Takapuna Library Poetry Reading - Tuesday 22/8/23

Poetry Day Prelude: Shore Words

Poetry Day Prelude: Shore WordsPoetry Day Prelude:

Shore Words

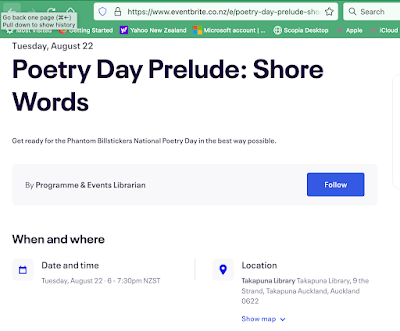

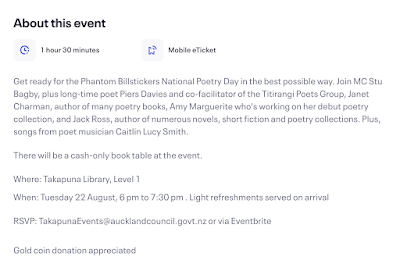

Get ready for the Phantom Billstickers National Poetry Day in the best possible way. Join MC Stu Bagby, plus long-time poet Piers Davies and co-facilitator of the Titirangi Poets Group, Janet Charman, author of many poetry books, Amy Marguerite who's working on her debut poetry collection, and Jack Ross, author of numerous novels, short fiction and poetry collections. Plus, songs from poet musician Caitlin Smith.

There will be a cash-only book table at the event.

Where: Takapuna Library, Level 1

When: Tuesday 22 August, 6 pm to 7:30 pm

Light refreshments served on arrival

RSVP: TakapunaEvents@aucklandcouncil.govt.nz or via Eventbrite

Gold coin donation appreciated.

Poetry Day Prelude: Shore Words / Takapuna Library (22/8/23)

Poetry Day Prelude: Shore Words / Takapuna Library (22/8/23)•

Published on August 04, 2023 16:25

July 15, 2023

Red Mole & the Romance of Alan Brunton

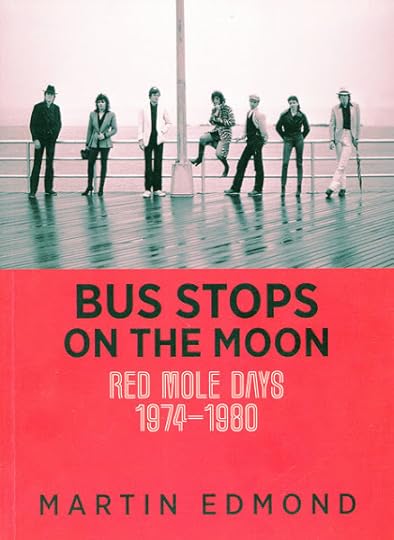

Martin Edmond: Bus Stops on the Moon (2020)

Martin Edmond: Bus Stops on the Moon (2020)This morning (16/7/23), the Stuff news site posted an article listing three "unmissable Kiwi docos" at this year's New Zealand International Film Festival. One of the three is award-winning documentarist Annie Goldson's latest film Red Mole: A Romance , which will be premiered there:

You can find a full list of Festival venues here, and - for those of us based in Tāmaki Makaurau - a full list of the films which will be on offer locally.

Red Mole: A Romance explores the origins, performances, personalities and fate of Red Mole, an experimental theatre troupe that took young NZ by storm in the 1970s. Red Mole was founded by poet Alan Brunton, ex-University of Auckland English Department, along with Sally Rodwell his partner in art and life. The two assembled a talented group of performers and musicians around them. An indefinable genre of poetry, dance, mask, fire-eating and rock music, Red Mole appeared everywhere from camping grounds to the Opera House. The troupe reached heights with its satirical cabaret at Carmen’s Balcony and the apocalyptic performances based on Brunton’s poetic scripts. Red Mole left Aotearoa for New York City at their peak where they received some acclaim until the demands of the city led to its core fragmenting. Red Mole: A Romance is both a social history and a poignant personal story told in part by Ruby Brunton, Alan and Sally’s daughter, herself a talented poet and performer. It draws on an extraordinary archive of scripts, videos, music, photographs, posters and more.

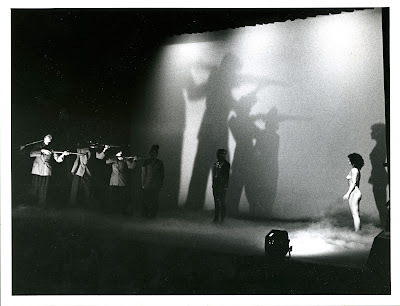

Joe Bleakley: Red Mole at Coney Island

Joe Bleakley: Red Mole at Coney IslandRed Mole was, I must confess, rather before my time. My own acquaintance with the mercurial Alan Brunton came later on, when he'd returned to Wellington and was busy with his publishing imprint Bumper Books. I've written more about that here.

Alan Brunton (1946-2002)

Alan Brunton (1946-2002)This new film seems very apposite, then, coming as it does hard on the heels of Martin Edmond's fascinating Red Mole memoir Bus Stops on the Moon (2020), pictured above.

I have watched the film of Red Mole's production of City of Night, Brunton's wildly eccentric adaptation of Aeschylus's Oresteia, though, so I do have some idea of what they were capable of!

Lord Galaxy's Travelling Players (1970s)

Lord Galaxy's Travelling Players (1970s)For anyone interested in NZ poetry or theatre, it would clearly be crazy to miss this film.

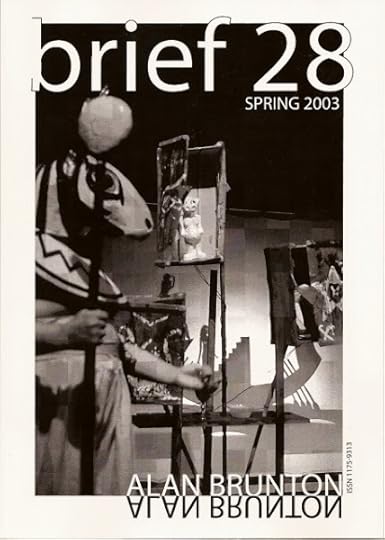

brief #28: Alan Brunton (October 2003)

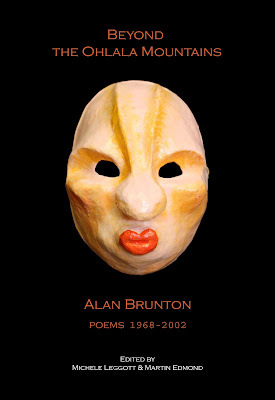

brief #28: Alan Brunton (October 2003)Scrolling back through my own archives, I find that I've reviewed three of Alan Brunton's books over the years: Fq (2003); Grooves of Glory (2005); and his selected poems Beyond the Ohlala Mountains (2013), as well as editing a special Brunton issue of the alt lit journal brief (#28, 2003).

Ave atque vale, Alan & Sally - you're both still sorely missed.

Michele Leggott & Martin Edmond, ed.: Beyond the Ohlala Mountains (2013)

Michele Leggott & Martin Edmond, ed.: Beyond the Ohlala Mountains (2013)•

Alan Brunton (26/10/2002)

Alan Brunton (26/10/2002)Alan Brunton

(1946-2002)

Select Bibliography

[from my collection]

Poetry:

Black and White Anthology. Taylors Mistake: Hawk Press, 1976.[with Sally Rodwell] Day for a Daughter. Wellington: Untold Books, 1989.Slow Passes: 1978-88. Introduction by Peter Simpson. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1991.Romaunt of Glossa: A Saga. Wellington: Bumper Books, 1998.Moonshine. Wellington: Bumper Books, 1998.Ecstasy. Wellington: Bumper Books, 2001.Fq. Wellington: Bumper Books, 2002.Beyond the Ohlala Mountains: Poems 1968-2002. Ed. Michele Leggott & Martin Edmond. Pokeno: Titus Books, 2013.

Performance:

A Red Mole Sketch Book. Wellington: Victoria University Press, 1989.Grooves of Glory: Three Performance Texts. Wellington: Bumper Books, 2004.

Prose:

Years Ago Today: Language & Performance, 1969. New Zealand Cultural Studies. Wellington: Bumper Books, 1997.

Edited:

[with Murray Edmond & Michele Leggott] Big Smoke: New Zealand Poems 1960-1975. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2000.The Brian Bell Reader. Wellington: Bumper Books, 2001.

Video:

Heaven’s Cloudy Smile: Two Poets Go for a Walk, dir. Sally Rodwell – with Alan Brunton & Michele Leggott. Wellington: GG Films / Red Mole, 1998. Video Cassette.Red Mole’s City of Night, dir. Alan Brunton & Sally Rodwell. Wellington: Red Mole, 2000. Video cassette.

Secondary:

Alan Brunton : Author Page. Auckland: nzepc, 2004.brief #28 (Oct 2003): Alan Brunton . Ed. Jack Ross. Auckland: The Writers Group, 2003.Celebrating Alan Brunton: A Concert and Book Launch for Fq. Auckland: Friday 6 December, 2002.Edmond, Martin. Bus Stops on the Moon: Red Mole Days 1974-1980. Dunedin: Otago University Press, 2020.Howard, David, & Michele Leggott, ed. "'When You Give So Much’: Some Recollections of Alan Brunton." Auckland: nzepc, 2002.

•

David Howard & Michele Leggott, ed.: 'When You Give So Much' (2002)

David Howard & Michele Leggott, ed.: 'When You Give So Much' (2002)

Published on July 15, 2023 13:51

June 22, 2023

Gore Vidal: Narratives of Empire

David Shankbone: Gore Vidal (2009)

David Shankbone: Gore Vidal (2009)Ralph came over to Stu and knelt down. 'Can we get you anything, Stu?'

Stu smiled. 'Yeah. Everything Gore Vidal ever wrote - those books about Lincoln and Aaron Burr and those guys. I always meant to read the suckers. Now it looks like I got the chance.'

- Stephen King, The Stand (1990): 923.

Towards the end of Stephen King's apocalyptic masterpiece The Stand, one of his main characters, Stu Redman, is left behind by his companions in a washed-out gully because he's sprained his ankle and they're unable to lift him out.

Stu's last, rather plaintive request is for a set of Gore Vidal's American history novels. We already know that he's a big reader. Earlier in the story he was enthralled by the adventures of Fiver and the other rabbits in Watership Down, but the Vidal novels seem like quite a departure from the quest narratives Stu loves - and which he and the others are far-from-coincidentally reenacting at this very moment in the story.

Stephen King: The Stand (1978 / 1990)

Stephen King: The Stand (1978 / 1990)Curiously enough, if we go back in time to 1978, when The Stand originally appeared - in a form severely truncated by the demands of his publisher's accounting department, much to King's chagrin - we find a rather different version of this scene:

Ralph came over to Stu and knelt down. 'Can we get you anything, Stu?'Ralph's crooked grin is the same on both occasions, but the books Stu longs to read have changed somewhat in the twelve years between the two texts of King's novel.

Stu smiled. 'Yeah. All those books about that Kent family. I always meant to read em. Now it looks like I got the chance.'

Ralph grinned crookedly. 'Sorry, Stu. Looks like I'm tapped.'

- Stephen King, The Stand (1978): 661.

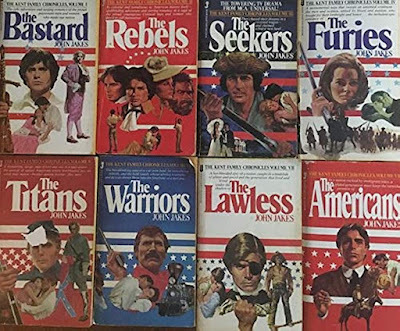

John Jakes: The Kent Family Chronicles (1974-79)

John Jakes: The Kent Family Chronicles (1974-79)For those of you who (like me) didn't happen to know, the "Kent Family Chronicles" are, according to Wikipedia:

a series of eight novels by John Jakes written for Lyle Engel of Book Creations, Inc. to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence of the United States.They were published between 1974 and 1979, which positions them nicely to be read by the 1978 version of Stu. All of the books were "best sellers, with no novel in the series selling fewer than 3.5 million copies."

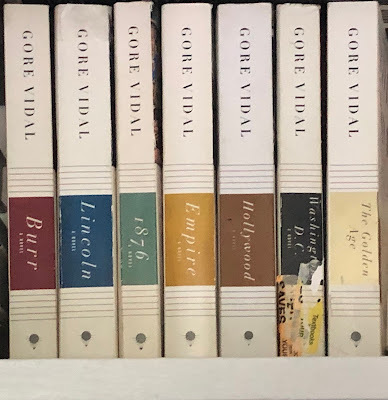

Gore Vidal: Narratives of Empire (1967-2000)

Gore Vidal: Narratives of Empire (1967-2000)Could the same be said of Gore Vidal's "Narratives of Empire" series? That was the author's final choice for an overall title, though his publisher apparently preferred "the politically neutral series-title 'American Chronicles'."

Although written at various times, over a period of thirty-odd years, out of historical sequence, these seven novels do have interlocking stories and characters - some, admittedly, rather crudely soldered onto the earlier books in order to fit them into Vidal's later vision for the series.

Here they are in order of appearance:

And here they are in chronological sequence:

(1967) (1973) (1976) (1984) (1987) (1990) (2000)

They were, at various times, referred to as "American Chronicles", "Narratives of a Golden Age" and "Narratives of Empire". Does this apparent indecision on their author's part explain some of the difficulties we find when trying to discuss them as a whole? What are they actually about? Certainly they don't aim to emulate the bicentennial boosterism of John Jakes's Kent Family Chronicles, but do they present a clear alternative to that?

(1775-1840) (1861-1865) (1875-1877) (1898-1906) (1917-1923) (1937-1952) (1939-2000)

•

Gore Vidal: Burr (1973)

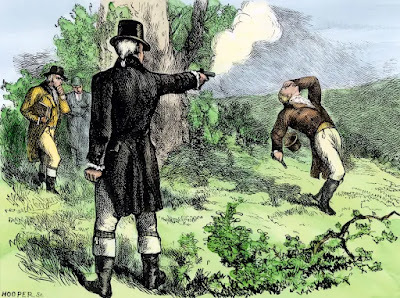

Gore Vidal: Burr (1973)The series began very promisingly with Burr, a multi-faceted romp through the Revolutionary War and the early years of the Republic, seen through the quizzical eyes of that pantomime villain Aaron Burr (or, rather, a young journalist's attempts to turn Burr's fragments of memoir into a coherent account of a long-lost age).

Of course, all this was long before the musical Hamilton made that particular founding father a household name. I have to confess to not having heard of Aaron Burr before reading Vidal's novel, let alone about his notorious duel with Alexander Hamilton. It was all news to me, in other words.

Lin-Manuel Miranda: Hamilton (2015)

Lin-Manuel Miranda: Hamilton (2015)Burr is clearly a kind of alter-ego for Gore Vidal: a kind of internal émigré, despised by his contemporaries for largely spurious reasons, but brighter and better-informed than any of them. Vidal makes no secret of Burr's flaws - just as he is open about his own in Palimpsest, his 1995 memoir - but the unspoken offence constituted by Vidal's unashamed homosexuality in repressed late-twentieth century America makes a good parallel with Burr's alleged "treason" - another name for the same political opportunism practised more successfully by the Empire-building Thomas Jefferson.

Stylistically, the book had much in common with other post-modern novels of the era such as John Barth's Sot-Weed Factor (1960) or John Berger's Little Big Man (1964). There was, however, a sophistication and depth to Vidal's knowledge of American history which gave it an extra edge. And I suspect that that's why it's still so readable today, when so many of the other dazzling fictions of the era have faded into obscurity.

The Burr-Hamilton Duel (1804)

The Burr-Hamilton Duel (1804)•

Gore Vidal: Lincoln (1984)

Gore Vidal: Lincoln (1984)With the next volume in the series - in chronological, though not in publication order - Vidal went into another gear. Lincoln is a brilliantly empathetic and subtle portrait of America's most famous president. Even Vidal's detractors were forced to admit that he'd managed to transform some of the most hackneyed material imaginable into a kind of secret history of the Civil War.

This was, admittedly, a few years before Ken Burn's classic PBS Documentary series woke up even non-history buffs to the sheer horror and momentousness of this "nineteenth-century catastrophe". Lincoln stands up very well to the comparison, though.

I've read many books about the era - Bruce Catton's and Shelby Foote's Civil War trilogies, Carl Sandburg's six-volume life of Lincoln, Freeman's seven-volume series about Robert E. Lee and his lieutenants, even Allan Nevin's 8-volume Ordeal of the Union - but I haven't spotted any obvious solecisms in Gore Vidal's knowledge, let alone his sophisticated treatment of the characters involved.

Honoré Morrow: Great Captain (1930)

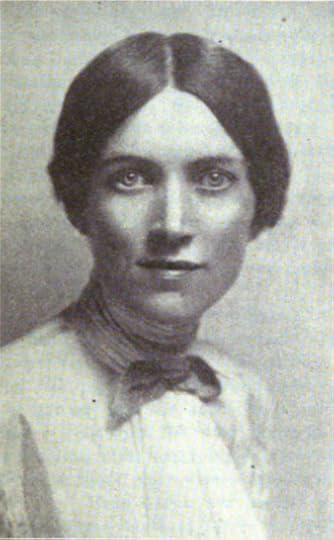

Honoré Morrow: Great Captain (1930)The same could certainly not be said for the above trilogy of Lincoln novels, by Theodore Dreiser-protégée Honoré Morrow, which I also happen to have on my shelves. It dates roughly from the era of movies such as Young Mister Lincoln (1939) and Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1940), and is rather like them in spirit.

Morrow has concocted a spirited yarn, with heavily fictionalised elements such as the Confederate spy Miss Ford who dominates the Lincoln household in the first novel, Forever Free (1927). Despite the fact that she's been detected separately by each member of the household (with the possible exception of the obnoxious Tad) she's allowed to run loose, concocting abduction and assassination plots with monotonous regularity, until she's finally stabbed by a kitchen hand - whilst disguised as a black slave - in a last desperate attempt to prevent the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation!

The second novel, With Malice Toward None (1928), centres upon a particularly saccharine love affair conducted by Senator Sumner with a Washington socialite, under the watchful eyes of his intimate friends, the Lincolns. Given the unrelenting, abundantly-documented hostility between the real Lincoln and Sumner, this is perhaps the weakest of the three books. (Or, as I'm tempted to add: "What's on the board, Miss Ford?")

Morrow's third and culminating volume, The Last Full Measure (1930), is largely concerned with the ins and outs of John Wilkes Booth's assassination plot. Like Vidal, Morrow doubles the President's wise and wholesome activities with the nefarious treachery of Booth and his low-life accomplices. Like Vidal - and yet so unlike. Once again, she fictionalises freely, and shifts speeches and events as it suits her. It is, nevertheless, probably the best written and constructed of her three novels.

Honoré Morrow's Lincoln is a devoted admirer of the poetry of Walt Whitman; his wife Mary Todd Lincoln is a constant help to him, despite occasional passing fits of temper; Seward, in her version, is a laughing buffoon and Chase a non-entity - it is Sumner who dominates the politics of the time. Above all, her Lincoln is sentimental and teary-eyed to an appalling degree. His obsession with deporting American negroes to Africa, and his refusal to see them as equal with whites are glossed over with facile phrases.

Given the way in which Vidal deconstructs all the convenient myths about Lincoln, it's hard to explain why 'the ancient' (as Nicolay and Hay, his two private secretaries, call him) remains so compelling and - let's face it - loveable as the central figure of his novel. Perhaps it's because he's constantly seen through the eyes of others: particularly John Hay (shown in a far more frivolous light in Morrow's version).

Reading the two novels in such swift succession doesn't really do justice to Morrow, who did a pretty good job under the constraints of her era - and who lacked the splendid Civil War histories now so readily available. The fact that one can still read Gore Vidal's book with admiration forty years after it was published, however, is a tribute not only to his consummate skill as a writer, but also to the profundity of his grasp of American history. He makes up almost nothing, and his book is the stronger for it.

Honoré Willsie Morrow (1880-1940)

Honoré Willsie Morrow (1880-1940)•

Gore Vidal: 1876 (1976)

Gore Vidal: 1876 (1976)If Lincoln is the high point of Gore Vidal's whole series of fictional histories, perhaps it's because his fascination with a figure of the past whom he is unable, finally, to fathom, let alone patronise, drives him to new heights as a writer. 1876, by contrast, albeit another fascinating historical tapestry, was written more in the cynical spirit of Burr.

This is hardly surprising, as it has the same narrator: Charles Schermerhorn Schuyler, Aaron Burr's illegitimate son, a reasonably well-known (though unfortunately almost penniless) writer who's been living in Europe since 1839. His return to the bustling republic of the gilded age is the subject of the book, which consists of 'notes' for the series of articles he hopes to write on the experience.

If all this sounds like a foreshadowing of Henry James's year-long return to America in 1904, which inspired his late masterpiece The American Scene (1907) - with its memorable pictures of the devastation of "the great lonely land", and the triumph of greed over the simpler country of his youth - that's presumably quite intentional. The young James only appears in passing in this novel, but will play a far more important part in the next one in line.

James A. Michener: Centennial (1974)

James A. Michener: Centennial (1974)1976, the bicentennial year, was, of course, a time when any number of backward looks over the United States' two centuries of history were to be expected. Besides the Kent Chronicles, one of the best known and most successful was James A. Michener's huge, episodic, chronicle novel Centennial.

Centennial is by no means a casual or optimistic celebration of the journey from there to here. It is, in fact, a long saga of deceit and bloodshed, culminating in the acquittal of a local entrepreneur who has devised a way for rich men to shoot (protected) bald eagles out of helicopters - they almost always miss, so he's devised a way of exploding a small plastic bag of offal outside the cockpit as he surreptitiously shoots the bird himself!

Beyond its rather sombre tone, it has little in common with Vidal's chronicle of political chicanery and intrigue, culminating in the first unequivocally stolen presidential election in American history - until the Bush / Gore débâcle of 2000, that is. Michener, by contrast, tries to take solace in the rich pageant of life on the plains.

The fact that both authors end up in so downbeat a mood may have something to do with the nadir of trust in the American system caused by the Watergate scandal of 1972-74 - Michener's narrator actually watches the hearings in his hotel room whilst charting the fortunes of his representative Colorado middletown of Centennial.

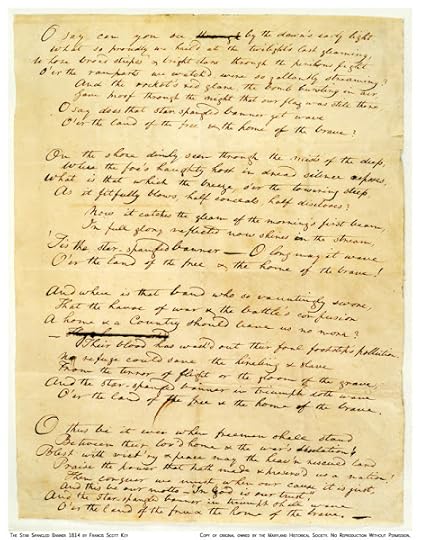

Whatever inspired this gloom in each case, though, it's as well for us as readers to be reminded from time to time that bad as things undoubtedly are now with the 'the land of the free and the home of the brave', they weren't all that great in 1976 - or 1876 - or virtually any other date in history one can name, for that matter - either.

Francis Scott Key: The Star-Spangled Banner (1814)

Francis Scott Key: The Star-Spangled Banner (1814)•

Gore Vidal: Empire (1987)

Gore Vidal: Empire (1987)Empire tries to do a great deal in a short space of time. This could be seen as admirable or unfortunate, depending on your prior expectations of a novel of this type - or in this series.

On the one hand, it provides us with a kind of updated version of Henry James's Portrait of a Lady in its account of the fascinating rise of Caroline Sanford from cheated heiress to self-assured newspaper publisher (there's something there, too, of Katharine Graham's successful tenure at the Washington Post, I suspect).

However, it's mostly a political history of the McKinley / Roosevelt era of imperial expansion on the part of America: it was, afer all, during this period that Puerto Rico, Hawaii, Guam, the Philippines, and a number of other Caribbean and Pacific dependencies were added to the "protection" of the United States.

The rise of yellow journalism and the growing dominance of William Randolph Hearst is also explored in some depth, largely through the former's relations with Caroline's scheming brother Blaise Sanford.

What else? There's a brief history of "the hearts": a group of wealthy Washingtonians including Henry Adams, his dead wife Clover, Secretary of State John Hay, and various others, who seem - in context - to embody some alternate philosophy of life superior to the merciless materialism of the fin de siècle.

All these ingredients would seem to promise a major novel. And it's certainly this which Vidal has laboured to compose. They fail, somehow, to cohere - perhaps because they lack a single central focus, unlike the earlier novels in the sequence.

If it ends up being a fascinating might-have-been in purely fictional terms, so much talent and skill has gone into it that it can still serve as a storehouse of contemporary attitudes and events. Where else, for instance, could I have found out about John Hay's early dialect poems "Little Breeches" and "Jim Bludso", which Henry James persists in quoting at him, embarrassingly, every time they meet?

John Hay: Pike County Ballads (1912)

John Hay: Pike County Ballads (1912)•

Gore Vidal: Hollywood (1990)

Gore Vidal: Hollywood (1990)The problem with Hollywood, which picks up pretty much where Empire left off - albeit with a decade or so in between - is that there's a bit too much scheming and politicking, and not nearly enough Hollywood.

The sordid saga of Warren Gamaliel Harding's rise to power and influence despite (or because of) his legion of crooked, small-town friends is expounded in great - though at times confusing - detail. Interesting though this undoubtedly is, it's hard to see precisely how it meshes with the continuing saga of Caroline Sanford, her brother Blaise, and their various lovers and friends.

Once again, this is an immensely informative novel for those of us who are bit shaky in our knowledge of early twentieth century American politics. For every reader who feels this to be a deficiency, however, I'll bet there are a dozen others who would rather hear more about the silent movies Caroline finds herself first starring in, then producing!

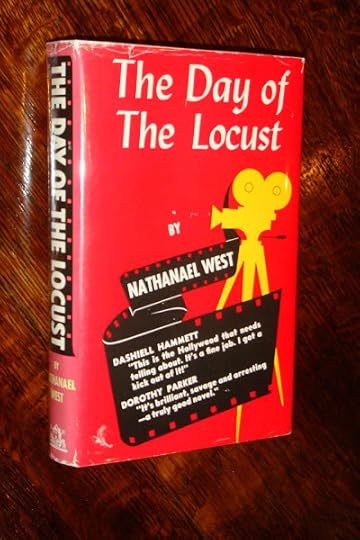

One glimpses, at times, in the livelier chapters of Vidal's book, the possibility of some modern rival to such classic Hollywood novels as Budd Schulberg's What Makes Sammy Run? (1941) or even Nathanael West's Day of the Locust (1939).

Alas, for the first time one begins to feel that the constraints of Vidal's series are beginning to outweigh the benefits. The book as a whole remains a fascinatingly panoramic view of many aspects of contemporary American life. It just lacks focus. But then, that no longer seems to be a vital part of Vidal's overall scheme.

Nathanael West: The Day of the Locust (1939)

Nathanael West: The Day of the Locust (1939)•

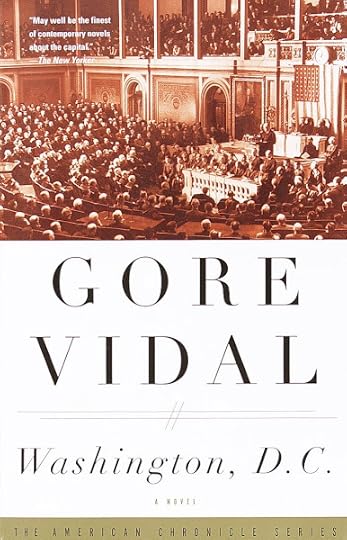

Gore Vidal: Washington, D. C. (1967 / 1994)

Gore Vidal: Washington, D. C. (1967 / 1994)The same could not be said of the next in the series - which was also, confusingly, the first to be written. The reason for this, of course, is that even if Vidal dreamed of such a roman fleuve in 1967, when he first published this book, he can have had little idea what precise form it would take.

Washington, D.C. is a very focussed novel indeed. Unfortunately, the main burden of the plot is the evil and underhanded way in which Enid Sanford, daughter of the nefarious Blaise (already familiar to readers of the previous two books), and sister to the protagonist, Peter Sanford, is sacrificed to the political ambitions of her husband, a JFK-clone called Clay Overbury.

The absence of Caroline Sanford from the narrative is due to the fact that she had not yet been invented when Vidal wrote it. In his introduction to the 1994 reissue of 1876, however, he reassures us that:

Now I have rewritten Washington, D.C., the summing-up novel, in order to bring together all the strands of the story. - Gore Vidal, "Narratives of a Golden Age." 1876: A Novel. 1977. London: Abacus, 1994. vii-xii.I was interested to check just how substantive this "rewriting" of the earlier novel was. Comparing my 1976 paperback to one published in 2000, I could find only two substantive new passages. The first, in chapter one, involved a more detailed account of Peter's genealogy, based on the events of the earlier books. The second, in chapter seven, involves a two-page exposition of just how their family is related to Aaron Burr, another subject intensively canvassed in Burr and 1876.

Beyond this, it's hard to see any really significant difference between the two texts. Washington, D.C. is largely a morality tale: a denunciation of the inevitable compromises involved in political advancement. Enid, however, is so poisonously mendacious and self-destructive a drunk, and Peter so pompous a prig, that it's hard to see them as constituting much of a moral centre to the narrative. As a whole, it lacks the more nuanced and complex picture of human relationships familiar to us from the earlier (or should I say later?) books in the series.

Perhaps it's just a question of what one expects from it, though. In his own online essay "Gore Vidal's American Chronicles: 1967-2000" (2005), Harry Kloman explains that:

With the appearance of The Golden Age in 2000, Washington, D.C. no longer stands as the closing volume in the Chronicles. Nonetheless, it remains unique among the seven books, arguably the best, and surely - with its introspective look at Washington politics, revealed through the experiences of Vidal's provocative fictional creations - the most intimate and original.I can't really agree, but it's certainly interesting to read an alternate view on the subject. The trouble is, the more vindictive and self-righteous Peter and his band of buddies became, the more I found myself sympathising with the undeniably dynamic, if a little too morally pliable, Clay Overbury.

Gore Vidal: Washington, D. C. (1967)

Gore Vidal: Washington, D. C. (1967)•

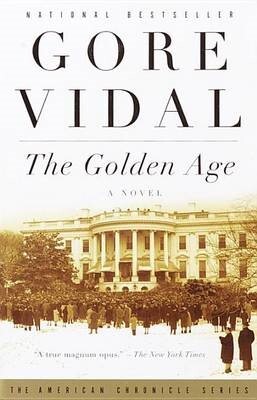

Gore Vidal: The Golden Age (2000)

Gore Vidal: The Golden Age (2000)Which brings us to The Golden Age. I wish I could see this as the triumphant culmination of Vidal's immense fictional design it was clearly meant to be.

And, yes, it begins well, with Caroline Sanford's return to America after twenty-odd years in France, and her gradual reintroduction to the new realities of the Franklin - rather than Theodore - Roosevelt era.

Unfortunately she dies halfway through, which leaves us with her self-satisfied nephew Peter as cicerone to the distinct lack of action which distinguishes the rest of the book.

There's a great deal of noise about the old canard that Roosevelt deliberately provoked the Japanese into attacking Pearl Harbour. There are a lot of cheap shots at his successor, Truman. There are even some perfunctory attempts at metafiction when Vidal introduces himself (both young and old) as a character in the narrative.

But there's none of the old zest, the sense of being in the hands of an immensely knowing and well-informed fictional prestidigitator. Tiresome factual glitches and even downright errors disfigure the pages: Churchill is described as a major player at the post-war Potsdam conference whereas he was actually replaced by his successor Clement Attlee early in the discussions; Clay Overbury has to share the stage with his presumed original, the real JFK (Vidal gets out of this one by having Clay die in a plane crash, which it's hinted may have been arranged by Peter!) ...

Ford Madox Ford: Last Post (1928)

Ford Madox Ford: Last Post (1928)Vidal ends up sounding more and more like a tiresome old conspiracy theorist, and so tendentious are some of his readings of the Second World War and its aftermath that it has the effect of casting doubt on many of his earlier interpretations of "received" history. Was he just a blustering fantasist all the time? It would be a shame to have to think so.

No, like Last Post, that thoroughly dispensable final part of Ford Madox Ford's Parade's End sequence, one would probably be better off not reading this one at all. Or certainly not rereading it. For all its chronological and thematic difficulties, it's best to continue to regard Washington D.C. as the last link in his fictional tapestry.

At least, that's what I would have advised Stu Redman, as he lay in his bivouac under the ruined interstate highway. Of course, given it was his version of 1990 at the time, he had little choice in the matter - but he was certainly fortunate that Hollywood would have just appeared to distract him from his seemingly desperate plight!

Gore Vidal: Palimpsest: A Memoir (1995)

Gore Vidal: Palimpsest: A Memoir (1995)•

Gore Vidal (1948)

Gore Vidal (1948)Eugene Luther Gore Vidal

(1925-2012)

Novels:

Williwaw (1946)In a Yellow Wood (1947)The City and the Pillar (1948)The Season of Comfort (1949)A Search for the King (1950)Dark Green, Bright Red (1950)[as Katherine Everard] A Star's Progress [aka Cry Shame!] (1950)The Judgment of Paris (1952)[as Edgar Box] Death in the Fifth Position (1952)[as Cameron Kay] Thieves Fall Out (1953)[as Edgar Box] Death Before Bedtime (1953)[as Edgar Box] Death Likes It Hot (1954)Messiah (1954)Julian (1964)Julian. 1962. Panther Books Ltd. Frogmore, St Albans, Herts: Granada Publishing Limited, 1972. Washington, D.C. [Narratives of Empire, 6] (1967)Washington, D.C. 1967. Panther Books Ltd. Frogmore, St Albans, Herts: Granada Publishing Limited, 1976.Washington, D.C. 1967. Narratives of Empire. Vintage. New York: Random House, Inc., 2000. Myra Breckinridge (1968)Two Sisters (1970)Burr [Narratives of Empire, 1] (1973)Burr. 1973. Panther Books Ltd. Frogmore, St Albans, Herts: Granada Publishing Limited, 1974. Myron (1974)1876 [Narratives of Empire, 3] (1976)1876. 1976. Narratives of a Golden Age. An Abacus Book. London: Little, Brown and Company (UK) Limited, 1994. Kalki (1978)Three by Box: The Complete Mysteries of Edgar Box (1978)Creation (1981)Creation: A Novel. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1981. Duluth (1983)Lincoln [Narratives of Empire, 2] (1984)Lincoln. 1984. Panther Books. London: Granada Publishing Ltd., 1985. Empire [Narratives of Empire, 4] (1987)Empire. 1987. Grafton Books. London: Collins Publishing Group, 1989. Hollywood [Narratives of Empire, 5] (1990)Hollywood: A Novel of America in the 1920s. 1990. Narratives of Empire. Vintage. New York: Random House, Inc., 2000. Live From Golgotha (1992)The Smithsonian Institution (1998)The Golden Age [Narratives of Empire, 7] (2000)The Golden Age. 2000. Narratives of Empire. An Abacus Book. London: Little, Brown and Company (UK), 2001.

Stories:

A Thirsty Evil (1956)Clouds and Eclipses: The Collected Short Stories (2006)

Plays:

Visit to a Small Planet (1957)The Best Man (1960)On the March to the Sea (1960–61 / 2004)Romulus [adapted from Friedrich Dürrenmatt's Romulus der Große (1950)] (1962)Weekend (1968)Drawing Room Comedy (1970)An Evening with Richard Nixon (1970)

Screenplays:

Climax!: A Farewell to Arms [TV adaptation] (1955)Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde [TV adaptation] (1955)The Best of Broadway [TV adaptation of Stage Door] (1955)The Catered Affair (1956)I Accuse! (1958)The Left Handed Gun (1958)The Scapegoat (1959)Ben Hur (1959)Suddenly Last Summer (1959)The Best Man (1964)Is Paris Burning? (1966)Last of the Mobile Hot Shots (1970)Caligula (1979)Dress Gray (1986)The Sicilian (1987)Billy the Kid (1989)Dimenticare Palermo (1989)

Non-fiction:

Rocking the Boat (1963)Reflections Upon a Sinking Ship (1969)Sex, Death and Money (1969)Homage to Daniel Shays: Collected Essays, 1952–1972 (1972)On Our Own Now: Collected Essays 1952-1972. 1974. Panther Books Ltd. Frogmore, St Albans, Herts: Granada Publishing Limited, 1976. Matters of Fact and of Fiction (1977)Sex is Politics and Vice Versa [Limited edition] (1979)[Ed.] Views from a Window (1981)The Second American Revolution (1983)Vidal In Venice (1985)Armageddon? [UK only] (1987)At Home (1988)A View From The Diner's Club [UK only] (1991)Screening History (1992)Decline and Fall of the American Empire (1992)United States: Essays 1952–1992 (1993)Palimpsest: A Memoir (1995)Palimpsest: A Memoir. 1995. An Abacus Book. London: Little, Brown and Company (UK), 1996. Virgin Islands [UK only] (1997)The American Presidency (1998)Sexually Speaking: Collected Sex Writings (1999)The Essential Gore Vidal. Ed. Fred Kaplan (1999)The Essential Gore Vidal. Ed. Fred Kaplan. 1999. An Abacus Book. London: Little, Brown and Company (UK), 2000. The Last Empire: Essays 1992–2000 (2001)Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace or How We Came To Be So Hated (2002)Dreaming War: Blood for Oil and the Cheney-Bush Junta (2002)Inventing a Nation: Washington, Adams, Jefferson (2003)Imperial America: Reflections on the United States of Amnesia (2004) Point to Point Navigation: A Memoir (2006)The Selected Essays of Gore Vidal (2008)Gore Vidal: Snapshots in History's Glare (2009)I Told You So: Gore Vidal Talks Politics: Interviews with Jon Wiener (2013)History of the National Security State. Introduction by Paul Jay (2014)Buckley vs. Vidal: The Historic 1968 ABC News Debates (2015)