Jack Ross's Blog, page 2

June 26, 2025

Fifty Years after the Fall of Saigon

Tim O'Brien: If I Die in a Combat Zone (1973)

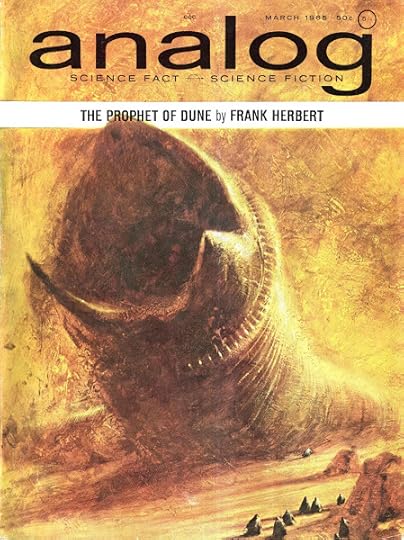

Tim O'Brien: If I Die in a Combat Zone (1973)The other day I bought a copy of Tim O'Brien's classic Vietnam war memoir from a Hospice Shop. It felt strange, very strange, to reread it - to revisit the atmosphere of those times. It was, after all, first published while the war was still going on, after the withdrawal of American troops, but before the ultimate humiliation of the fall of Saigon.

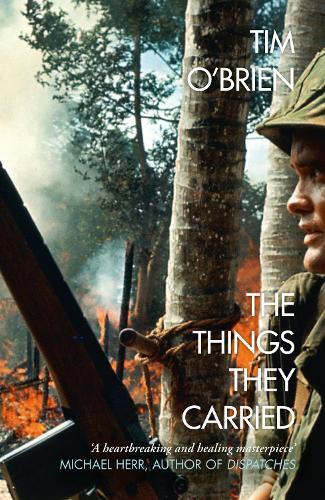

O'Brien is probably better known, now, for his National Book Award-winning Vietnam novel Going After Cacciato (1978), together with the linked stories in The Things They Carried (1990), but it's worth remembering that this memoir, whose original title was If I Die in a Combat Zone, Box Me Up and Ship Me Home was named the Outstanding Book of 1973 by the New York Times.

Why? I guess because O'Brien tried to cover all the bases: he was honest about his own internal debate about the "morality" of the war, but also admitted that it was largely by chance that he failed to run away to Sweden rather than being shipped off to Vietnam with his unit.

He turned out, by chance, to be serving in the same region where the infamous My Lai massacre had taken place the year before. He records the casual killings and cruelty which were part of everyday life as an occupying force. But he also explains the constant fear of being killed or maimed by mines or mortar fire which gnawed away at most soldiers - apart from the occasional hero (or psychopath) - from day 1 to day 365 of their tours.

James Fenton: All the Wrong Places (1988)

James Fenton: All the Wrong Places (1988)Mind you, if you want to draw any actual parallels between present day geopolitics and the fall of Saigon on on 30 April 1975, you'll have to look elsewhere. One place to go might be English poet and roving war correspondent James Fenton's classic All The Wrong Places: Adrift In The Politics Of Southeast Asia.

Fenton is still, perhaps, most famous - or notorious - for hitching a ride on a North Vietnamese tank just before it broke into the compound of the Saigon Presidential Palace. You can read some of his own thoughts on the matter in "The Fall of Saigon," from Granta 15 (1985).

And here are a few lines from one of his strangely Kiplingesque war poems, "Out of the East":

... it's a far cry from the temple yard

To the map of the general staff

From the grease pen to the gasping men

To the wind that blows the soul like chaff

And it's a far cry from the paddy track

To the palace of the king

And many go

Before they know

It's a far cry.

It's a war cry.

Cry for the war that has done this thing.

Stanley Karnow: Vietnam: A History (1983)

Stanley Karnow: Vietnam: A History (1983)As usual, there are Academic histories a-plenty. Stanley Karnow's Vietnam: A History, billed in its later editions as "the first complete account of Vietnam at war," is the one that I dutifully read from cover to cover when I had to teach The Things They Carried in a Modern Novel course at Auckland Uni in the early 1990s.

I must admit, though, to a preference for the shorter and more focussed Vietnam: The Ten Thousand Day War , based on Michael Maclear's epic 1980 26-part Canadian television documentary about the Vietnam War.

Michael Maclear: Vietnam: The Ten Thousand Day War (1981)

Michael Maclear: Vietnam: The Ten Thousand Day War (1981)Even further back than that, when all these "old, unhappy far-off things" seemed considerably closer to us in time, I was asked to review an essay collection called Tell Me Lies About Vietnam: Cultural Battles for the Meaning of the War. Here's a quote from what I had to say about the subject then, in 1989:

Alf Louvre & Jeffrey Walsh, ed.: Tell Me Lies About Vietnam (1988)

Alf Louvre & Jeffrey Walsh, ed.: Tell Me Lies About Vietnam (1988)... the fact that one has compiled and classified a series of responses to Vietnam in different media does not add up to a consistent view from which one can generalize. The war was appropriated by various interest groups ... but the infinite suffering and death that was inflicted on Indo-China by the Americans and their allies seems to me to be a fact which somewhat outweighs the importance, in the final analysis, of yet another spate of Narcissistic films and books about ‘the end of American innocence’. The virtues of this book lie in its particularity – its emphasis on individual artists (Ralph Steadman, Tim Page, Susan Sontag) and popular media (cartoons, comic books, rock music). Its errors reside in the assumption that some over-view of the falsification of the war can be deduced from all this – an attitude which is, in itself, as dangerous a ‘lie’ about Vietnam as any of those which the contributors expose.I might say it rather differently now - talk about over-complex, Grad School-inflected, run-on sentences! - but I still agree with that remark that "the infinite suffering and death ... inflicted on Indo-China by the Americans and their allies seems to me to be a fact which somewhat outweighs the importance ... of Narcissistic films and books about ‘the end of American innocence’." It's really just a question of proportion:

Grethe Cammermeyer: Visiting Vietnam (2019)

Grethe Cammermeyer: Visiting Vietnam (2019)A 2008 study by the British Medical Journal came up with a ... toll of 3,812,000 dead in Vietnam between 1955 and 2002.The Wikipedia article from which I took these figures estimates 58,098 American casualties overall. Even if you dispute the BMJ's analysis - and some do - you still have a discrepancy of literally millions of military and civilian casualties inflicted in Vietnam by two foreign armies - the French and the Americans - neither of whom suffered even a tenth of this death toll themselves.

North Vietnamese Spring offensive (13 December 1974 – 30 April 1975)

North Vietnamese Spring offensive (13 December 1974 – 30 April 1975)And yet, despite all that fire power and overwhelming military might - on paper - they still didn't win. The French were driven out by the Viet Minh, and a treaty of partition between North and South Vietnam was signed in Geneva on July 21, 1954. But the Americans insisted on reenacting the whole conflict on a larger scale, only to sign their own "Peace Accord" in Paris on January 27, 1973, officially ending their direct involvement in the Vietnam War.

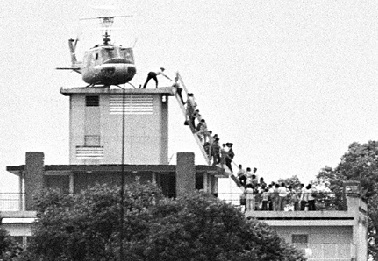

Hubert van Es: Evacuating Saigon (29 April 1975)

Hubert van Es: Evacuating Saigon (29 April 1975)A year later North Vietnamese forces toppled President Thieu's regime without any significant response from the U.S. The war had become too unpopular for anyone in power there to wish to resume it, and so the last pictures of what was then America's longest war were those disgraceful sauve-qui-peut scenes of America's friends and allies clamouring desperately for space on the last helicopters out.

It did take some time after that debacle for the old adage to be forgotten: "Never get into a land war in Asia". Just as it took Europe 25 years after 1914 to nerve itself up for another world war, so it took 25 years after 1975 before the Americans again decided to get into a quick war in Afghanistan to punish a few "fanatical extremists" - oddly enough, the same extremists (then referred to as the mujahideen) they'd been funding for decades, ever since the Soviet invasion in 1979.

Taliban offensive (1 May – 15 August 2021)

Taliban offensive (1 May – 15 August 2021)Twenty years later, in 2021, the Americans withdrew in even more disgraceful circumstances than in 1975, having achieved far less, and leaving even larger crowds of those who had helped them at the mercy of the vengeful Taliban.

The parallels seem too obvious to be stressed, but maybe they still don't seem real to those who don't remember 1975, and perhaps weren't even born when the post-9/11 invasion of Afghanistan took place. Wars, however, are very real. They have a horrible way of coming home to you in unexpected ways: when a bomb goes off next to you for some obscure geopolitical reason, for instance.

I just wish we could show some signs of learning a few lessons from all this ancient history. For instance, that humiliating a whole country, and their rulers - as Donald Trump has just done in Iran - is sowing the wind to reap the whirlwind. All empires crumble, and the fact that they tend to flex their muscles most ostentatiously just before their fall ought to remind the "great powers" that a return to the arts of peace and diplomacy is not necessarily a sign of weakness.

It's tempting, too, to remark that if the armies of the "free world" could learn to stop stomping around other people's backyards, their health services might end up having to deal with far fewer cases of PTSD. But the Forever War (as Noam Chomsky and others have called it) continues: sometimes it's Iraquis who are the enemy, sometimes Iranians, occasionally even Russians, but there's always got to be someone to machine-gun and bomb in the name of "liberal democracy".

The Taliban in the Presidential Palace (Kabul, 15 August 2021)

The Taliban in the Presidential Palace (Kabul, 15 August 2021)•

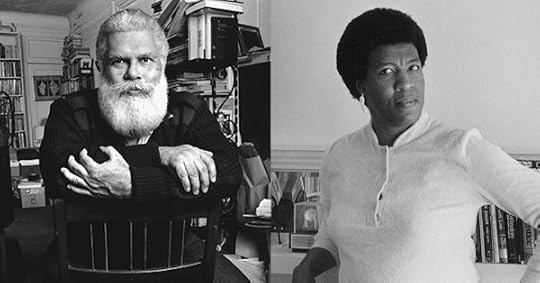

Tim O'Brien (2023)

Tim O'Brien (2023)Tim O'Brien

(1946- )

Fiction:

"Where Have You Gone, Charming Billy?" (1975)Northern Lights (1975)Northern Lights. 1975. Flamingo. London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1998.Going After Cacciato (1978)Going After Cacciato. 1978. Flamingo. London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1998.The Nuclear Age (1985)The Things They Carried (1990)The Things They Carried. 1990. Flamingo. London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1991.In the Lake of the Woods (1994)Tomcat in Love (1998)July, July (2002)America Fantastica (2023)

Non-fiction:

If I Die in a Combat Zone, Box Me Up and Ship Me Home (1973)If I Die in a Combat Zone. 1973. Flamingo Modern Classics. London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1995.Dad's Maybe Book (2019)

Secondary:

Greene, Graham. The Quiet American: Text and Criticism. 1955. Ed. John Clark Pratt. The Viking Critical Library. New York: Penguin, 1996.Herr, Michael. Dispatches. 1977. Introduction by David Leitch. Textplus. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1989.Karnow, Stanley. Vietnam: A History. 1983. Rev. ed. London: Pimlico, 1990.Louvre, Alf & Jeffrey Walsh, ed. Tell Me Lies About Vietnam: Cultural Battles for the Meaning of the War. Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1988.Maclear, Michael. Vietnam: The Ten Thousand Day War. 1981. London: Thames / Methuen, 1982.Sheehan, Neil. A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam. 1988. London: Guild Publishing, by arrangement with Jonathan Cape, Ltd., 1989.

•

Tim O'Brien: The Things They Carried (1990)

Tim O'Brien: The Things They Carried (1990)

Published on June 26, 2025 15:07

June 16, 2025

Jack Ross: Stories

Simon Creasey: Coromandel (2005)

Simon Creasey: Coromandel (2005)Preface

'Talking against death'! yep that sums our craft up

in three brutal words ..."- Tracey Slaughter. Email to Jack Ross (14/2/2024)

While I was in the early stages of compiling the pieces which would eventually turn into my latest book of stories, Haunts (2024), I decided to try to straighten out all the myriad drafts I'd accumulated by pasting them up online.

As it turned out, that didn't help me much (if at all), but it did provide the kernel for a larger Stories site which has now grown to include the texts of all my published short fiction to date - with the exception of my three novels, each of which already has one (or more) websites dedicated to it.

Like the earlier Poems site, then, to which this is intended as a companion,

Jack Ross: Stories

contains the texts of all three novellas and four short fiction collections I've published so far. It's almost a year since Haunts was launched for sale online (well in advance of the actual physical booklaunch on Saturday, 5th October), so it seems like an appropriate time to share its contents with any of you who'd like to sample the text before buying a copy.

Before outlining the content of the site, though, I thought I'd better say some more about its structure.

The first thing you see, if you click on this link, will be the warning above.

After you've clicked on the orange "I understand and I wish to continue" button, you'll be taken to the following page:

This should give you full access to the site.

The reason for all this is because some of the stories do contain swear words and sexually explicit material, and I've found in the past that this tends to attract the attention of roving web editors, who red flag and - in some cases - simply take down any pages which offend in this way.

I've therefore decided to mark both this and my Poems site - as well with those devoted to the three novels in my R.E.M. trilogy - as containing "Adult content":

This "sensitive content" gateway will, unfortunately, have to be renegotiated every time you access any of these sites. No doubt this will have the effect of reducing the number of visits to each of them, but it also increases the level of dedication needed to get there - not in itself a bad thing. Bona fide readers are always welcome.Jack Ross: Nights with Giordano Bruno (2000)

Nights with Giordano Bruno. ISBN 0-9582225-0-9. Wellington: Bumper Books, 2000. [xii] + 224.Jack Ross: The Imaginary Museum of Atlantis (2006)

The Imaginary Museum of Atlantis. ISBN 0-9582586-8-6 . Auckland: Titus Books, 2006. 164 pp.Who am I? Automatic WritingWhere am I? CuttingsJack Ross: E M O (2008)

E M O. ISBN 978-1-877441-07-3. Auckland: Titus Books, 2008. [vi] + 258 pp.EVA AVEMoons of MarsOvid in Otherworld

Here, then, is a breakdown of the contents of my new fiction website. At present it contains 59 stories, ranging in length from novellas to flash fictions, taken from seven books:

•Jack Ross: Monkey Miss Her Now (2004)

Monkey Miss Her Now & Everything a Teenage Girl Should Know. ISBN 0-476-00182-X. Auckland: Danger Publishing, 2004. 138 pp. [13 short stories]Jack Ross: Trouble in Mind (2005)

Trouble in Mind. ISBN 0-9582586-1-9. Auckland: Titus Books, 2005. [ii] + 102 pp. [single novella]Jack Ross: Kingdom of Alt (2010)

Kingdom of Alt. ISBN 978-1-877441-15-8. Auckland: Titus Books, 2010. [iv] + 240 pp. [8 short stories]Jack Ross: The Annotated Tree Worship: Draft Research Portfolio (2017)

The Annotated Tree Worship: Draft Research Portfolio. ISBN 978-0-473-41328-6. Paper Table Novellas. Auckland: Paper Table, 2017. iv + 88 pp. [first of 2 novellas]

Jack Ross: The Annotated Tree Worship: List of Topoi (2017)

The Annotated Tree Worship: List of Topoi. ISBN 978-0-473-41329-3. Paper Table Novellas. Auckland: Paper Table, 2017. iv + 94 pp. [second of 2 novellas]Jack Ross: Ghost Stories (2019)

Ghost Stories. ISBN 978-0-9951165-5-9. 99% Press. Auckland: Lasavia Publishing, 2019. 140 pp. [12 short stories]Jack Ross: Haunts (2024)

Haunts. ISBN 978-1-991083-17-3. 99% Press. Auckland: Lasavia Publishing, 2024. 202 pp. [13 short stories]

•

Jack Ross: Stories (1996- )

Along with my Opinions site ("Essays, Interviews, Introductions & Reviews - 1987 to the present"), and the already available Poems , this showcases pretty much all of the work I've published to date. Enjoy!

•

Published on June 16, 2025 14:23

May 22, 2025

'Everyone should be noted': Richard & Victor Taylor

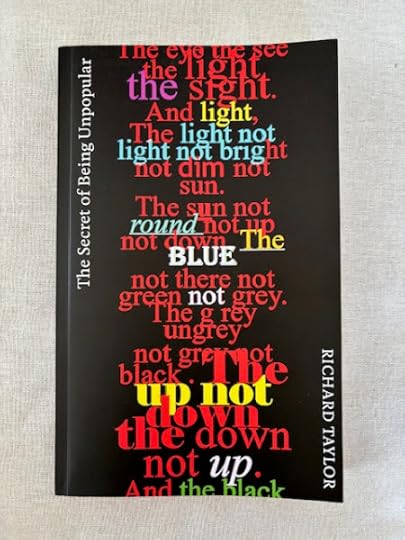

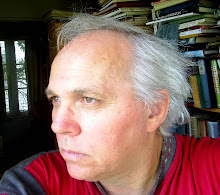

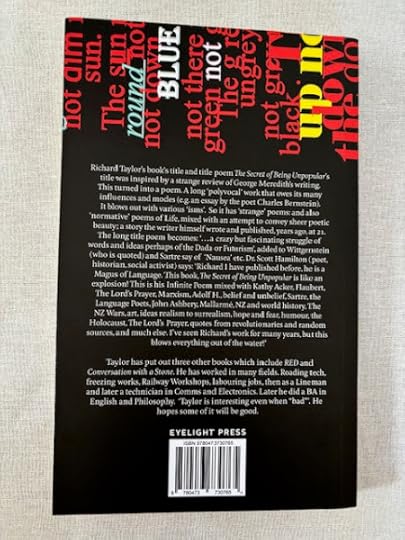

Richard Taylor: The Secret of Being Unpopular (2024)

Richard Taylor: The Secret of Being Unpopular (2024)[photograph: Bronwyn Lloyd]

'Everyone should be noted' is the last line of the Acknowledgments at the back of Auckland poet Richard Taylor's latest book, The Secret of Being Unpopular.

This post isn't really meant as a formal review of his work - he is, after all, large, he contains multitudes - but more as a few comments, combined with reminiscences.

I've capped it off with two email interviews, one with Richard and the other with his son Victor, who's also just published a collection of poems, his first, entitled Rift.

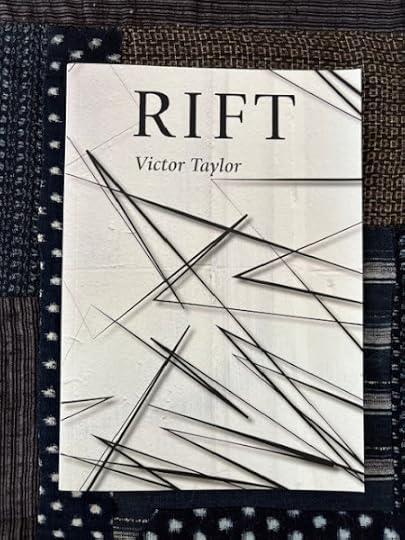

Victor Taylor: Rift (2024)

Victor Taylor: Rift (2024)[photograph: Bronwyn Lloyd]

•

Richard Taylor (1948- )

Richard Taylor (1948- )I've known Richard Taylor for nearly thirty years. We first met at Poetry Live, the weekly poetry reading / performance roadshow which has been migrating from bar to bar around Auckland's K. Rd for the last several decades. We were both friends with the late Rev. Leicester Kyle, and he might be said to have introduced us.

How shall sum up Richard? He can be quite a disconcerting person to meet for the first time. While immensely erudite and well-read, he doesn't exactly project a bookish demeanour. No, there's something more Rabelaisian about him than that: someone who loves food and drink and witty conversation - and is sometimes a little the worse for wear.

The freeflowing allusiveness of his talk is certainly not for the uptight, either. There have been some face-offs over the years - never (that I can recall) between Richard and me, but between him and others of the thinskinned poetry tribe.

Richard's mind is never asleep. He always pursues his own bent. I recall some of his experiments with photography and typography on his marvellous blog Eyelight (2005- ) - long treks over fields of associative imagery, which must have taken forever to construct, but which seem as anarchic and fluid as Walt Whitman's dithyrambic diatribes must have been to readers in the 1850s.

This dizzying sense of multiplying associations comes through in his prose, too. When, in the past, as a magazine editor, I commissioned pieces from Richard, I found that a little compression and tidying did have the effect of burnishing the power and originality of his ideas. But I also knew I was normalising them - attempting to obscure the particularity of the personality behind this mode of discourse.

He's not one of those law-giving critics people fear: a Belinsky, or an Edmund Wilson, whose verdicts can make or break a career. Richard belongs more to the side of the accommodating and celebratory: a Coleridge, or a Harold Bloom, wearing his idiosyncracies on his sleeve. He reads so much! Richard's always under the spell of some book or other, and he's combined all these years of apparently random text-sampling into an immensely powerful lens of critical insight.

Richard Taylor: Conversation with a Stone (2007)

Richard Taylor: Conversation with a Stone (2007)[cover design: Ellen Portch]

There was a rather studied elegance to his previous book Conversation with a Stone. Now, as I glance through it, I can admire the ways in which Richard's anarchic muse has been kept in bounds (if not wholly tamed) by a clear layout with lots of white space around the lines. Is it quite him, though? The appearance of this book also spurred him to start a new blog: Richard, You MUST try to be more focused - (2012- ) - a quote (apparently) from one of his university tutors way back when - which continues to partner, but not supplant, his older site Eyelight.

For me, part of the interest of this new book is that it represents Richard's version of Richard, rather than that of a well-meaning editor or publisher. It's far closer to the true comprehensiveness of his vision (insofar as that's possible in the print medium).

Henry Wallis: The Death of Chatterton (1856-58)

Henry Wallis: The Death of Chatterton (1856-58)I guess everybody knows the story of the death of Chatterton - both the suicide of the starving young poet ("marvellous boy", as Wordsworth called him), and the strange story of the commemorative painting above, by Pre-Raphaelite artist Henry Wallis.

The young poet and novelist George Meredith agreed to pose for the picture, as Wallis was a friend of his brother-in-law. To compound this chain of connections, Meredith's wife Mary Ellen eloped with Wallis shortly after the picture had been exhibited at the Royal Academy, and the two fled together to Capri.

"Richard Taylor's book's title and title poem The Secret of Being Unpopular's title was inspired by a strange review of George Meredith", he informs us on the back-cover blurb of his book. So just why was George Meredith so unpopular? Wikipedia informs us that:

His style, in both poetry and prose, was noted for its syntactic complexity; Oscar Wilde likened it to "chaos illumined by brilliant flashes of lightning".There's more to it than that, though. His fame as a poet is based mainly on the sonnet sequence Modern Love (1862), "a sequence of fifty 16-line sonnets about the failure of a marriage, an episodic verse narrative that has been described as 'a novella in verse'." This sequence, while not directly autobiographical, was clearly inspired by his own experience of being abandoned by Mary Ellen. The impulse to write it came from her lonely death in 1861 - though neither Meredith nor her ex-lover Wallis nor her father Thomas Love Peacock, another well-known poet and novelist, deigned to attend the funeral.

The bitterness and disillusionment fostered by these early experiences informed almost all of Meredith's subsequent work. It has been argued, in fact, that his style grew more complex and convoluted in direct response to the public demand for further romans-à-clef from him. Only those works of his which seemed to have clear parallels in contemporary scandal achieved more than a succès d'estime.

Richard Taylor: Blogger profile (2005- )

Richard Taylor: Blogger profile (2005- )Can one see in all this certain resemblances to Richard Taylor's own "chaos illumined by brilliant flashes of lightning"? You never know just what will come up in a Taylor poem or prose-piece - that is, if there really is much of a difference between the two genres for him.

Meredith's work, too, tends to be more honoured in the breach than the observance - his public, now, tends to be made up predominantly of literature professors. But Modern Love, in particular, is a very powerful poem indeed. As - for that matter - is that long title-piece of Richard's, "The Secret of Being Unpopular." If you're serious about learning more about the nature of Richard's work, this is probably the best place to start.

One thing's for certain: you'll be opening up a new and unaccustomed world for yourself if you do so.

Richard Taylor: The Secret of Being Unpopular (2024)

Richard Taylor: The Secret of Being Unpopular (2024)•

Victor Taylor: Rift (2024)

Victor Taylor: Rift (2024)Richard Taylor has written of his son Victor's book:

For a father and son to publish poetry or anything else at the same time is very unusual and means there is surely hope for, not only human life (despite the many trials we are all subject to) but culture and creativity.For, "while at times a philosophical pessimist," Richard says he "cannot help being a living and day by day optimist, except perhaps on a cold dreary morning before breakfast!"

I myself am writing this on just such a morning - cold and dreary, with a driving rain coming in from the sea - but I have had breakfast, so let's continue.

University of Auckland: Kate Edger Information Commons

University of Auckland: Kate Edger Information CommonsI have a (probably bad) habit of starting to read poetry collections at the back, with the last poem, then dipping a tentative toe into the middle and leafing around a little before ever venturing to turn to the front.

In the case of Rift, this led me straight to a poem called "Star of south":

They call this university "an institution of learning". I sit with kateI like that. I like it a lot. I like the picture it paints: the sparrows, the students, the pomposity of this shabby old "institution of learning". What I like particularly, though, is the absence of fine writing or pretentious word choices in the descriptions. The sparrows "jump along" - they don't hop or frisk or congregate or anything else of that sort. And then one of them "leaps up" - rather than nuzzling or pecking or fluttering. Simple and to the point.

edger in her block. The sparrows chirp, I feed them, I watch them

jump along; young students walk by. I sit and watch sparrows.

One leaps up and takes bread from my hand - back to his friends.

We then get a profusion of imagery suggested by a young lady descending a nearby set of stairs, absurdly hymned and idealised with full Keatsian exuberance through four full stanzas, until, again, the poet comes back down to earth:

Apart from that, not much happens in the kate edger block, or toIn form, this is clearly reminiscent of a Frank O'Hara "I do this, I do that" poem: the use of first person and present tense, accompanied by a kind of appositional irony.

kate edger or the block. I will just keep feeding sparrows, watching

students, or maybe I will go to the bookshop. think up another

poem, short or prose. I could unleash four elements of multiple

patterns from all seven realms, circle earth, tap into ley-lines -

create a world of gold pyramids and bronze shine a pale sheen.

And, as with Frank O'Hara's work, there's a delightful insouciance about it. O'Hara had to learn to curb his original surrealist urge and counterpoint it with more quotidian details. Victor, too, seems to have discovered how to retain portions of his more florid linguistic instincts by tempering them with the everyday. It's a splendid coda to his book.

Leafing back a few pages, I find "Golden horse":

Here is Jakey an autistic 15-year-old boy, he sits at his computerWell, I for one am hooked. I have to find out more of Jakey's story. I don't want to introduce any unnecessary spoilers, but I fear (like me) you already suspect that it will end badly.

playing computer games all day no one knows he exists except his

mother and his uncle; they all live in a rundown trailer park. "Be

quiet!" - His mother is opening the door to his room. "Shhhhhh!"

But Jakey already exists by the end of that first stanza. Victor's talent for characterisation and vivid narrative is perhaps the most notable thing about this first collection of his poetry to date. It's an unusual skill in a field so often dominated by imagery and autbiographical musings. And it bodes well for the future, I think.

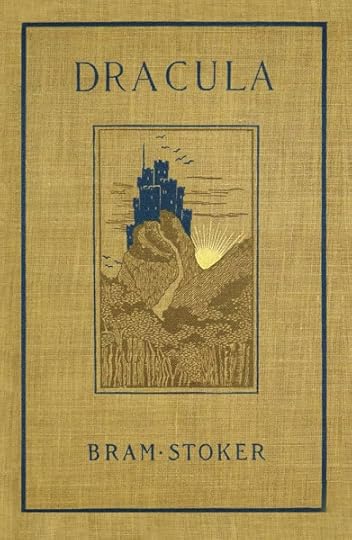

Bram Stoker: Dracula (1897)

Bram Stoker: Dracula (1897)"I’m also chipping away at Dracula," says Victor below, towards the end of his interview. I suspect that the reason this comment interests me is not simply because of my obsession with Bram Stoker, Sheridan Le Fanu, M. R. James, and other writers of gothic literature, but also because of the nature of the novel itself.

Readers who've come to the story by way of screen adaptations are often surprised by how complex and "intertextual" a novel Dracula is. It's made up of letters, diary entries, news reports - even transcripts of recordings made on wax cylinders: pretty dazzlingly innovative technology for the late 1890s.

In fact it could be argued that not only did this aspect of Stoker's narrative help to inspire steampunk, but its nature as a self-questioning artefact anticipates many of the innovations of the Nouveau roman of the 1950s.

I remark on it here because I think that it offers clues on how Victor might accommodate his taste for metaphysics with his undoubted talent for characterisation and narrative as he continues to develop as a writer.

If his father Richard exhibits a Walt Whitman-like taste for the vast and multifarious, sounding his "barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world", it might be said that it is Victor who more closely resembles George Meredith: not so much the syntactic complexity, but certainly the "chaos illumined by brilliant flashes of lightning."

How else could one characterise Jakey's story, this account of an "autistic 15-year-old boy" no one else knows exists?

I look forward to reading more by Victor in the future, while continuing to follow, with awe, Richard Taylor's fascinating, visionary, Blakean career.

George Meredith (1828-1909)

George Meredith (1828-1909)•

Richard Taylor (1948- )

Richard Taylor (1948- )'No Great Fixed Ideas':

Seven Questions with Richard Taylor

What are the strengths of your new book of poems, would you say?

I think the mix of "voices" and a mix of an intuitive and 'planned' way of writing. Thus I have mixed older (in style) with more recent work. I have a kind of focus. However I use as can be seen a range of texts to point to various ideas. In a sense - except inside my poems - I am not saying anything in the long titular poem -- or I am taking a position that explores. Also the book in the early stages signals later works. Often the quotes are either myself, others or a mixture of ... This creates an eerie effect sometimes beautiful. I mix more obviously 'beautiful' poems with more densely 'written' or language based.Why did you give it that title?

The title is from a review of Meredith as explained. Then it grew upon me that I am referring to myself. I think I am somehow and even want to be 'unpopular' but not in any radical way. I like the idea I have read almost nothing of Meredith but he seems to fascinate me and he evokes that review which in an essay on Meredith, Pritchett quotes, which I found out later ... It, the words of the review inspired me to write and I wrote that long poem very quickly. The other poems echo later poems and things in that long poem. Acker describes, in a way, my technique in the interview I quote. Bouvard and Pecuchet I love and they question forever! Thus I am a questioner ... Like Wittgenstein.What pleases you most about it?

I like the mix of poems. At the moment I need to do some more copies and correct some errors. But poems such as my truck poem join in with say 'Humpty Empty Back Make' or 'Glass Swan'. Although I use references or hints to other works I avoid the Eliot-Pound obsession with the decline of culture. I like their methods but I would celebrate William Carlos Williams as much as Eliot or his Paterson and also Hart Crane's Bridge, or the spirit of it, and also Moore's quotes sometimes as with Williams of 'ordinary' things and people. Hence both my father and mother talk in the poems as does the tramp in Gavin Bryars 'Jesus Christ never...' and there is a Maori Tohunga saying things we might not agree with but there he was, then my early story based on working in the freezing works (published) in Mate a long time ago, is there and some of a dramatic 'Shakespearean' poem mixes with my early paen to (it was my father and father-in law's death and so on. When I read the long poem or poems I find things that seem new each time.Is there anything about it that displeases you?

I always feel limited by a single medium. I wanted, but can afford, images and colours and much much more in the book and the text esp. the long poem. I am also a bit unfair calling Einstein 'Deathstein' but it was Leo Szilard (invented and patented (!) the chain reaction) who persuaded E. to write a letter to Roosevelt. Hence the Manhattan (Richard Rhodes The Making of the Atomic Bomb. I read this way before this film re Oppenheimer or Oppenhimmel.) But like Wittgenstein I think science and technology have been too highly lifted up into the light - this is something he felt during and after WWII and I feel this. But how to show my interest in philosophy and avoid something someone has seen in a movie and so on? There are poems in the first two parts I might have replaced but overall I feel I have a sufficient mix. I am trying to avoid one 'style'... perhaps influenced, say, by Barthes' Writing Degree Zero but also the idea to play, mix things, take a chance. The "bad" poems are always there. [Of course there are also typos etc but I am thinking of leaving them all in!] Ashbery and Sylvia Plath were two poets who in different ways were also important to me as Eliot was and still is given my wariness of him and Pound's obsessions ... Also Auden and some of the French symbolists et al ...Which people - writers, artists, musicians, or otherwise - have influenced you most?

I think that as a teenager all the usual Romantic poets, Shakespeare, Eliot, certain artists (all art interests me) and many novelists. Also my reading of Gerald Durrell, and the Scientific Book Club Books, and much else. Lewis Carroll, R A K Mason, and much else. But more recently from about 1988 or so. Jacob Bronowski's The Ascent of Man, and later Oliver Sacks, but I read for years a lot of John Ashbery's poetry, but also the US Language Poets, Stein somewhat, Beckett, Auden when I was a teenager but I still quote him and many others. Wordsworth and Keats, Coleridge but there are many modern poets in NZ also, and elsewhere. I like writers like Donald Barthelme and Kafka and Richard Brautigan, Rilke. Possibly Ted Berrigan and Berryman. It is accumulative as I am 'always reading'!

(1904-1987)

(1904-1987)Joseph Campbell said "Follow your bliss" - what's your bliss?

I wasn't sure who Campbell was. I would say it is reading but also being and being healthy in the world. Also learning but added to that a proviso like the narrator in Ford's The Sportswriter I like also to not know some things. The myths etc I invent myself as if talking to myself. I like Ovid's Metamorphosis rather than Dante. One bliss was reading The Brothers Karamazov more recently. In the world, just being, seeing beautiful things and trees and flowers or experiencing beautiful or interesting ideas and word combinations. The general phenomena of this world. No great fixed ideas.What are you reading at the moment? Poetry, or something else?

I am reading one of the diaries of Anne Truitt, an artist I hadn't known until I read her first book. Also I read some of Stein's 'Stanzas in Meditation', some Keats, but I like what to me is the comedy of Beckett so decided to read his trilogy Molloy, Malone Dies, and the Unnamable. I read widely but I read fairly recently Carson McCullers' The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. She was indeed a great writer.

Richard, You MUST try to be more focused - (2012- )

Richard, You MUST try to be more focused - (2012- )•

Janet Robin: Richard & Victor Taylor at a Protest (2012)

Janet Robin: Richard & Victor Taylor at a Protest (2012)'Pepperoni Pizzas & Metaphysical Ideas':

Seven Questions with Victor Taylor

What are the strengths of your new book of poems, would you say?

I’d say the main strength of my book lies in the variety of forms. The idea is to further separate and isolate each poem from the others. Every poem exists in its own spiritual domain — they don’t link up or form a narrative chain. This means the reader is encountering something entirely new with each piece.Why did you give it that title?

There is a similarity, however, in the metaphysical ideas. Many of the poems are surreal and transcendent, so the central strength is really in the images themselves.

Well, I played around with a few names — VAST, VOID, and some other more extravagant ones. RIFT felt simpler, perhaps more neutral. A rift means a break, split, or crack in something, and one of my goals is to break the reader’s perception of reality — to get them to question what is real. To me, dreams are just as real as waking reality.What pleases you most about it?

RIFT may have been chosen unconsciously. Maybe I felt isolated, like there’s a rift between me and everything else. Maybe I should have called it I am in the rift.

This is my first book, and I’m really pleased with it. For one, it’s the best thing I’ve ever produced. I began my journey into poetry when my father encouraged me to start reading books. From there, I eventually started writing a few poems of my own. I fell in love with the art form — it felt like magic, which, in many ways, it is.

What pleases me most is being able to express all my visions and images through poetry. That, to me, is the greatest joy.

Fiona McEwen: Victor Taylor reading at Poetry Live (April 1, 2025)

Fiona McEwen: Victor Taylor reading at Poetry Live (April 1, 2025)Is there anything about it that displeases you?

Nothing really displeases me about poetry itself — except perhaps the continuous wave of confessionalist poetry. At its height, particularly around 2022 and 2023, it felt like a dense cloud of pathological blackness. That trend became overwhelming. Recently, I noticed an new style of poetry I call “Encryptic” poetry - emerging in 2025.Which people - writers, artists, musicians, or otherwise - have influenced you most?

Many people have influenced me. In the early days, I probably absorbed too much from others, which made it difficult to develop my own voice. That’s a common challenge when you’re starting out. But over time, with more experience, I’ve learned how to hold on to my own style while still drawing inspiration from others.Joseph Campbell said "Follow your bliss" - what's your bliss?

My dad — who’s a great poet — introduced me to many poets early on. I was especially drawn to the Romantic symbolists: Blake, Keats, Shelley. More recently, I’ve been reading Bob Kaufman, whose work offers a different kind of intensity and rhythm.

These days, with Facebook full of poetry groups and so many styles circulating, I think originality is more important than ever. I also have several friends who are poets, and being around them keeps me sharp and engaged with the craft.

Apart from pepperoni pizzas? Well — fantasy, and useless metaphysical ideas.What are you reading at the moment? Poetry, or something else?

I’m currently reading American Literature, which I was introduced to through my university course at Massey. Some of the authors include Henry James, Emily Dickinson, Sylvia Plath, and many others. I’m also chipping away at Dracula.

Father's Day (July 6, 2018)

Father's Day (July 6, 2018)l-to-r: Finnegan, Ellery, Richard & Victor Taylor

Times like this make life worth living

- Richard Taylor

•

Published on May 22, 2025 15:33

May 6, 2025

Confederates

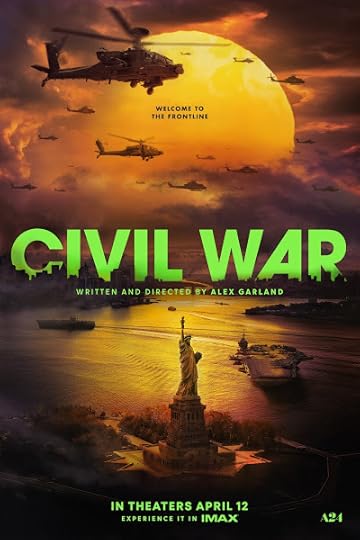

Alex Garland, dir.: Civil War (2024)

Alex Garland, dir.: Civil War (2024)I couldn't quite bring myself to go and see Alex Garland's much-hyped action film Civil War when it first hit the cinemas last year. It felt like an unnecessary incitement to violence at the time, pre-US election, when it still seemed possible - likely, even - that reason would prevail.

Now, a year later, having finally watched the movie, it's hard to see what what all the fuss was about. The Trump-like president, played by Nick Offerman, who's somehow hijacked his way into a third term, is opposed by a helicopter and tank-toting band of uniformed secessionists who appear to have almost infinite resources at their command.

Civil War core cast:

Civil War core cast:[l-to-r: Kirsten Dunst, Wagner Moura, Stephen McKinley Henderson, Cailee Spaeny]

No, the morality of the plot is all to do with the coarsening effects of passively witnessing - and, in some cases, getting off on - other people's violent acts, in the guise of objective reportage. Kirsten Dunst (who plays a kind of updated version of World War II photojournalist Lee Miller) has become severely burnt out in the process.

She and her band of misfit reporters all learn a lot about themselves, and each other, in their perilous trek across war-torn America - replete with tortured looters on gibbets and corpses being trucked into mass graves - but unfortunately such self-knowledge seems to equate with being too slow to get out of the way of bullets in this movie, so most of the information ends up getting lost in transmission.

Tony Horwitz: Confederates in the Attic (1998)

Tony Horwitz: Confederates in the Attic (1998)The main reason I decided to watch the film at all was because I'd just finished reading the book above, Tony Horwitz's 25-year-old exposé of the sheer extent of sympathy with the so-called "Lost Cause" of the Confederacy - not only in the Southern States, but across the United States as a whole.

Horwitz tries to stress the humorous side of this obsession, as in his account of a five-man reenactment of Pickett's charge by a squad of hardcore neo-rebels:

A lobster-red woman in a halter top matched Rob stride for stride, carefully studying his uniform.It all seems considerably less quaint and amusing now, after the 2021 Capitol riot and the exponential growth of such extremist groups as the Proud Boys and other far-right militants.

"What are you guys?" she asked.

"Confederates," Rob mumbled.

"Ferrets?"

"Confederates," Rob repeated.

"Oh," she said, looking underwhelmed. - Confederates in the Attic: 278.

Tony Horwitz (1958-2019)

Tony Horwitz (1958-2019)•

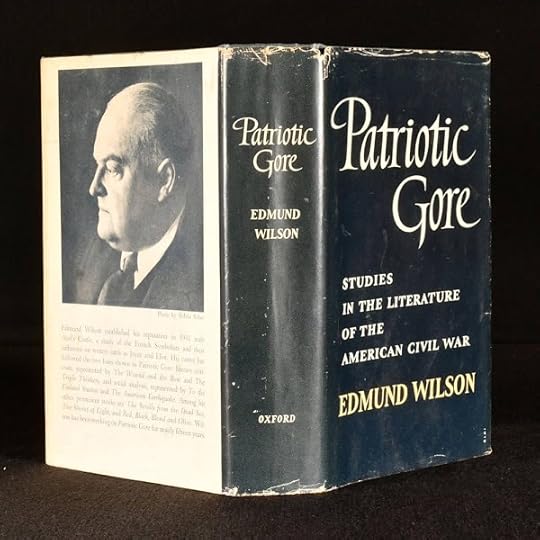

Edmund Wilson: Patriotic Gore (1963)

Edmund Wilson: Patriotic Gore (1963)It's not that unusual for me to read several books simultaneously. Sometimes I move through them at about the same rate; other times one takes over altogether. It can be quite a long drawn out process to get to the end of all of them.

Alongside Confederates in the Attic, I found myself rereading Edmund Wilson's rather ponderous set of "Studies in the Literature of the Civil War", Patriotic Gore. The two books have a lot more in common than simply treating the same subject in different ways.

Tony Horwitz won the Pulitzer Prize for national reporting in 1995, so he's no light-weight, despite the rather garish design and packaging of his book. But Edmund Wilson is certainly far more of a name to conjure with: one of America's most celebrated literary critics, three-time finalist in the National Book Awards (the second time for Patriotic Gore), he remains a distinctly impressive figure.

However, his dismissive, off-the-cuff verdicts on such present-day luminaries as H. P. Lovecraft ("Tales of the Marvellous and the Ridiculous," 1945) and J. R. R. Tolkien ("Oo, Those Awful Orcs!," 1956) have become so notorious that they now threaten to overshadow his more substantive achievements.

Edmund Wilson: Literary Essays and Reviews of the 1930s and 40s (2007)

Edmund Wilson: Literary Essays and Reviews of the 1930s and 40s (2007)Actually, Wilson's greatest legacy may well turn out to be the idea for the Library of America (1979- ), a uniform set of classic works from the United States, based loosely on the French Bibliothèque de la Pléiade (1931- ). It came to fruition only after his death, largely through the efforts of Jason Epstein and others, and it wasn't until a quarter of a century later that Wilson himself finally joined its ranks with a double-volume selection from his literary essays and reviews.

Edmund Wilson: Literary Essays and Reviews (2 vols: 2007)

Edmund Wilson: Literary Essays and Reviews (2 vols: 2007)The two books, Wilson's and Horwitz's, were published exactly 35 years apart, the first during the intense period of self-examination triggered by the Civil War centennial in the early 1960s, the second in the late Clinton era, pre-9/11, when the much-touted Pax Americana could still be seen as a valid concept.

In between the two came Shelby Foote.

•

Ken Burns: Shelby Foote (1916-2005)

Ken Burns: Shelby Foote (1916-2005)Or rather, in the early 1990s, Ken Burns's phenomenally successful 9-part PBS documentary series The Civil War (1990) had the inadvertent effect of propelling a hitherto largely unknown Southern writer to international stardom.

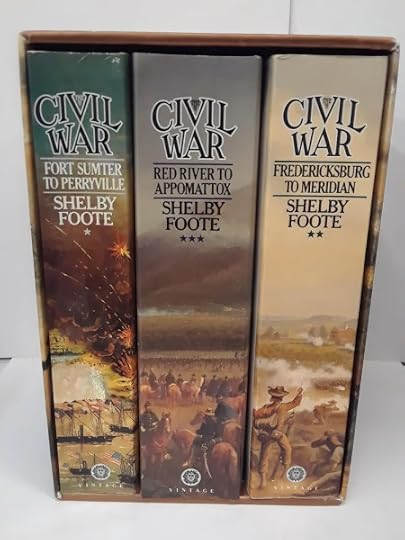

Shelby Foote: The Civil War: A Narrative (3 vols: 1958-74)

Shelby Foote: The Civil War: A Narrative (3 vols: 1958-74)That's the other book I've been rereading recently: Foote's immense narrative history of the civil war - a labour of love which took him almost twenty years to complete. I've already written a couple of posts on this subject - one in the larger context of the literature of the Civil War, the other as part of a piece on the alleged "amateurism" of narrative historians in general.

In the first of these pieces, written more than a decade ago, I was content to echo Foote's own assessment of his authorial stance:

Foote corrects the Union bias of earlier historians: an unabashed Southerner, he achieves a kind of imaginative empathy with the principal protagonists in the drama which is unlikely ever to be repeated or surpassed. This is certainly the best history of the war to date. It is a military history above all, though - if you want political insights, then Foote still needs to be supplemented by various others.In the second, composed more recently, in 2023, I'd altered my view somewhat:

Since the appearance of Ken Burn's ... Civil War ... which made Shelby Foote a star, his epic narrative history of the war has somewhat fallen from grace.

It's true that he does consciously go out of his way to present a more Southern view of the so-called "irrepressible conflict" than such Northern historians as Bruce Catton and Allan Nevins in their own multi-volume works. [However], his view that the two undoubted geniuses produced by the civil war were Abraham Lincoln and Nathan Bedford Forrest is no longer seen as an amusing paradox, but rather a clear statement of "Lost Cause" belief.

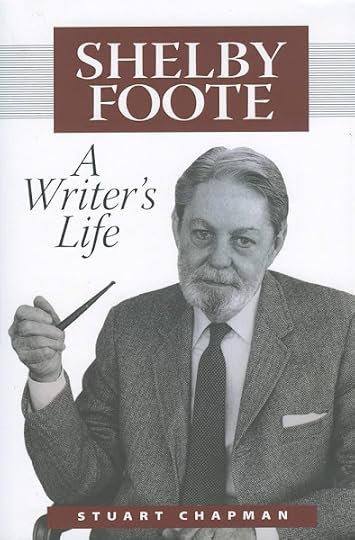

Certainly he was a man of his own time and place. Stuart Chapman's critical biography of Foote reveals the complexity of his upbringing and self-positioning in the America of Jim Crow and the early Civil Rights movement.

For myself, I find it far too facile to arrange the writers and thinkers of the past into convenient columns of "right-thinking" and "aberrant". It's perhaps going too far to say that tout comprendre, c'est tout pardonner, but being a liberal Southerner in the mid-twentieth century was not an easy row to hoe.

The fact that he's been criticised roundly by both sides for his views is surely some kind of testimony to his even-handedness? He's no apologist for racism by any means: no hagiographer of Southern rights, unlike General Lee's biographer Douglas Southall Freeman.

C. Stuart Chapman: Shelby Foote: A Writer's Life (2003)

C. Stuart Chapman: Shelby Foote: A Writer's Life (2003)It was rather a salutary experience to read Stuart Chapman's biography of Foote. The fact that it appeared two years before the writer's death may have inhibited Chapman somewhat in his analysis of the contradictions between Foote's warring ideological positions: on the one hand, sympathy for the South first and last; on the other, recognition of the futility of their continued refusal to recognise civil rights. Nevertheless, there was still much there to ponder.

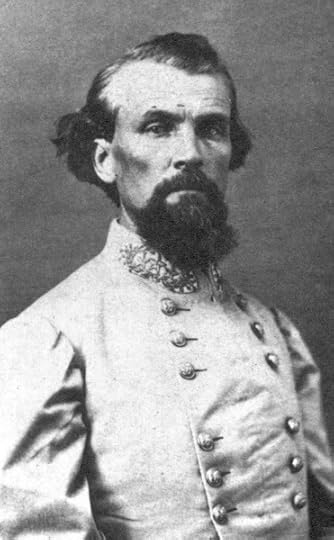

Nathan Bedford Forrest (1821-1877)

Nathan Bedford Forrest (1821-1877)Anove all, Chapman highlights Foote's passionate admiration for the dashing bravado of Nathan Bedford Forrest, slave-trader, military wizard, and first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, contrasting it with the historian's slightly grudging respect for the genius of the Union hero, Abraham Lincoln.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865)

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865)I had thought that the two opposing principles were held in some kind of equilibrium - albeit precarious - in Foote's actual history of the war, but I now think I was wrong. What I detect there now is a resolute denial of the evidence for virtually any Southern atrocities (the Fort Pillow massacre, the appalling conditions at Andersonville prison), and a strange method of attributing victory to the side reporting the fewest overall casualties, regardless of the strategic consequences of such "triumphs". Antietam and Gettysburg become, for him, near-Southern successes rather than Union victories.

I can now see what his despised "professional historians" were complaining about when they criticised Foote for his uncritical use of a single, often unreliable, source when discussing complex issues and events. His failure to provide the complete set of references he'd earlier promised for the end of his third volume also begins to look a little suspicious in hindsight. Essentially he used the information which best suited his thesis, even when it came from dubious "Lost Cause" apologias.

In this respect, the chapter "At the Foote of the Master" in Horwitz's Confederates in the Attic makes even more interesting reading today than when it was first written. Rather than any kind of reconciliation with Yankeedom, it's Foote's fierce Southern nationalism which comes out most strongly in Horwitz's interview:

His great-grandfather [Colonel Hezekiah William Foote ... who owned five plantations and over one hundred slaves] had opposed secession but fought without hesitation for the South. "Just as I would have," Foote said. "I'd be with my people, right or wrong. If I was against slavery, I'd still be with the South. I'm a man, my society needs me, here I am. The difference between North and South in the war is that there was no stigma attached to the Northern man who paid two hundred dollars to not go to war, or who hired a German replacement. In the South you could have done that, but no one would. You'd have been scorned." [149-50]The saddest thing about all this is that the reader feels increasingly that this romanticising of the old South has come to mean more to Foote than any attempt to get at the truth - and also to suspect that the motives behind it are largely personal.

Although Foote did serve as an artillery captain in World War II, he missed going into combat on D-Day as a result of being court-martialled for falsifying documents: to wit, a mileage report he wrote to cover a clandestine trip to Belfast to see his then girl-friend (later wife).

Returning to America, Foote enlisted as a private in the marines and went through boot camp. But the war ended just as he was bound for combat again, this time in the Pacific. To paraphrase what he'd said of the Civil War, Foote had missed the great trauma of his own generation's adolescence. [149]His views on race are also somewhat troubling. He remarks on the consequences of Reconstruction:

"What has dismayed me so much is the behavior of blacks. They are fulfilling every dire prophecy the Ku Klux Klan made. It's no longer safe to be on the streets in black neighborhoods. They are acting as if the utter lie about blacks being somewhere between ape and man were true." [152]This particular diatribe, from a man who claims to have always supported racial integration, concludes with a comparison of the Klan "to the Free French Resistance to Nazi occupation," together with an "explanation" that:

"Freedom riders were a pretty weird-looking group to Southerners ... The men had odd haircuts and strange baggy clothes and seemed to associate with people with an intimacy that we didn't allow. So the so-called right-thinking people of the South said, 'They're sending their riffraff down here. Let our riffraff take care of them.' Then they sat back while the good ol' boys in the pickup trucks took care of it, under the Confederate banner." [154]And, à propos of Foote's claims about the greater social stigma of a failure to serve in the Confederate than in the Union army, it's curious that he fails to mention the 1862 "Twenty Negro Law" in the Southern States which "exempted from Confederate military service one white man for every twenty slaves owned on a Confederate plantation."

It was at this point in the conflict that the soldiers began to complain about a "rich man's war and a poor man's fight" - or, as Confederate soldier Sam Watkins put it:

Soldiers had enlisted for twelve months only, and had faithfully complied with their volunteer obligations; the terms for which they had enlisted had expired, and they naturally looked upon it that they had a right to go home ... War had become a reality; they were tired of it. A law had been passed by the Confederate States Congress called the conscript act. A soldier had no right to volunteer and to choose the branch of service he preferred. He was conscripted. From this time on till the end of the war, a soldier was simply a machine, a conscript ... All our pride and valor had gone, and we were sick of war and the Southern Confederacy.That has more of the ring of truth about it - to my ears, at least.

Samuel R. Watkins (1839-1901)

Samuel R. Watkins (1839-1901)•

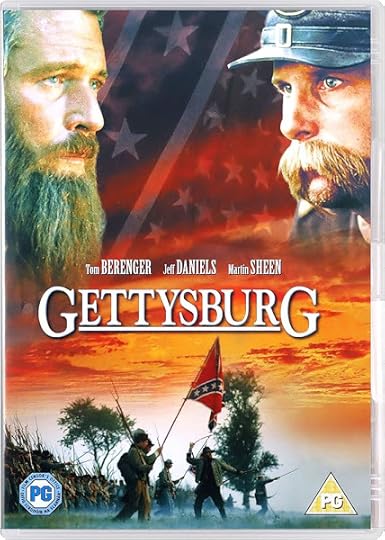

Ronald F. Maxwell, dir.: Gettysburg (1993)

Ronald F. Maxwell, dir.: Gettysburg (1993)[Based on The Killer Angels, by Michael Shaara (1974)]

A good deal of Tony Horwitz's book is concerned with the growing craze of Civil War reenactment. I remember seeing a vast horde of these reenactors - most of them looking disconcertingly well-fed - puffing up the slopes towards the Union centre in the "Pickett's Charge" scenes of Ronald Maxwell's four-hour war epic Gettysburg.

It's largely as a protest against such dilettantish, "farb" reenactments that Horwitz's friend Robert Lee Hodge and his friends perform their own hommage to Pickett's Charge - the one referred to in the passage quoted above.

Hodge and those like them try to recreate the actual - not the counterfeit - garb and physique of Confederate soldiers, as well as admiring their ethos. Another of his neologisms is "wargasm": an intense series of visits to as many classic battle sites as possible in a severely limited time-frame. And while it's hard to dispute Old Glory -author Jonathan Raban's view that he

would as soon tramp bare-foot through a snake-infested Ecuadorian marsh as spend a week in period costume, in the undiluted company of Robert Lee Hodge on a Civil Wargasm.It's almost equally difficult to disagree with his claim that "Horwitz deserves some sort of medal for valor on the reader's behalf as he immerses himself in a society that most readers would instinctively shun":

his version of the South is solidly credible throughout - and seriously bad news for the rest of America.Yes, the sting is in the tail there. It was - and still is - bad news for the rest of America. And while it may only have been the central concern of a few hardcore eccentrics in 1998, now, in 2025, the lunatics have definitely taken over the asylum.

I wish I could claim to have foreseen something of the sort some years ago, when I wrote the following poem - based on a viewing of the interminable Gettysburg (1993) and its even more tedious successor Gods and Generals (2003). Alas, at the time, like Horwitz, I still saw the whole thing as a bit of a laugh.

•

Ronald F. Maxwell, dir.: Gettysburg (1993)

Ronald F. Maxwell, dir.: Gettysburg (1993)

Gettysburg

The worst fake beards

in the history of cinema

Tom Berenger in particular

looked like the pirate king

in panto

but more to the point

I never realized

so many Confederates

detested slavery

regretted it hadn’t

already been abolished

what they were fighting for

was liberty of conscience

independence

pushing back Northern invaders

(by invading the North)

nor did I know that Robert E. Lee

had never abandoned a battlefield

in the face of the enemy

Antietam?

so the whole thing was just

a ghastly mistake

where the Northerners took advantage

of their nobler opponents

in their mechanistic way

In Gods and Generals

the prequel

we further learn

that not only did Jackson too

hate slavery

but that he used to prance round

playing horsey

with five-year-old girls

and weeping buckets

when the latter died

he’s crying for all of us

for the whole war

said an awestruck aide

I know just how he felt

[20/1/16-22/10/17]

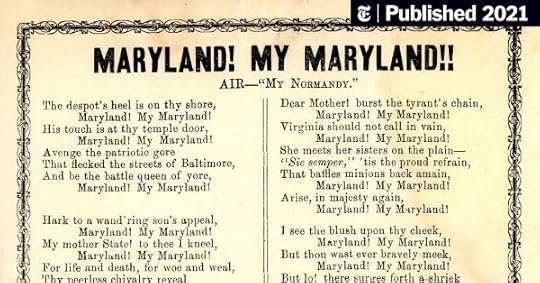

James Ryder Randall: Maryland, My Maryland (1861)

James Ryder Randall: Maryland, My Maryland (1861)•

Tony Horwitz (2009)

Tony Horwitz (2009)Anthony Lander Horwitz

(1958-2019)

Books:

One for the Road: a Hitchhiker's Outback (1987)Baghdad Without A Map (1991)Confederates in the Attic (1998)Blue Latitudes: Boldly Going Where Captain Cook Has Gone Before [aka "Into the Blue: Boldly Going Where Captain Cook Has Gone Before"] (2002)The Devil May Care: 50 Intrepid Americans and Their Quest for the Unknown (2003)A Voyage Long and Strange: Rediscovering the New World (2008)Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid That Sparked the Civil War (2011)BOOM: Oil, Money, Cowboys, Strippers, and the Energy Rush That Could Change America Forever (2014)Spying on the South: An Odyssey Across the American Divide (2019)

Tony Horwitz: Spying on the South (2019)

Tony Horwitz: Spying on the South (2019)•

Published on May 06, 2025 15:37

April 12, 2025

Favourite Children's Authors: Laura Ingalls Wilder

Laura Ingalls Wilder: Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography (1930 / 2014)

Laura Ingalls Wilder: Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography (1930 / 2014)It was Wednesday the 6th of October, 2021. Auckland was in the middle of yet another COVID lockdown. We were feeling a bit peeved because (as usual) it seemed to be just us again: stuck in our bubbles, cycling through the same old bits of dross on TV, while the rest of the country went out to meet one another and enjoy the Spring weather.

But, as it turned out, we had not been forgotten! A care package arrived from my brother-in-law Greg and his partner Celia in Martinborough: two boxes of books from the Book Grocer.

I seized on the box of biographies, Bronwyn the box of craft books. Besides a couple of celebrity pop star memoirs, which didn't really take my fancy, my box contained: Frederick Forsyth: The Outsider: My Life in Intrigue (2015)Caroline Fraser: Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder (2017)Nelson Mandela: Dare Not Linger: The Presidential Years (2016)Philip Norman: Paul McCartney: The Life (2016)Ramie Targoff: Renaissance Woman: The Life of Vittoria Colonna (2018)Frances Wilson: Guilty Thing: A Life of Thomas De Quincey (2016) I wrote a post about the last one in the list a few years ago, but haven't really had a chance to do justice to any of the others until now.

It's probably only right that I should confess that the first book that fell open in my hand was the biography of Paul McCartney, Since then I've gone even further down that particular rabbit hole by purchasing Irish poet Paul Muldoon's weirdly compelling edition of the former's collected lyrics:

Paul McCartney: The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present. Ed. Paul Muldoon (2021)

Paul McCartney: The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present. Ed. Paul Muldoon (2021)Getting back to the point, though, I was especially excited to see there a copy of Caroline Fraser's Pulitzer-Prize-winning biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder, an author whom I read a good deal of as a child once I managed to get over my prejudice against such a "girly-looking" set of books.

Caroline Fraser: Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder (2017)

Caroline Fraser: Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder (2017)My mother and sister were particular devotees of her work; all of us watched the saccharine, Michael Landon-dominated Little House on the Prairie TV series with gritted teeth, amid repeated asseverations that the books were "not like that."

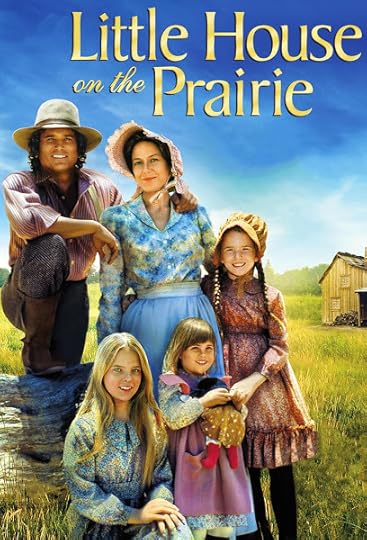

Blanche Hanalis: Little House on the Prairie (1974-83)

Blanche Hanalis: Little House on the Prairie (1974-83)l-to-r: Michael Landon as 'Charles Ingalls', Melissa Sue Anderson as 'Mary', Karen Grassle as 'Caroline',

Rachel Lindsay Greenbush as 'Carrie', & Melissa Gilbert as 'Laura'

•

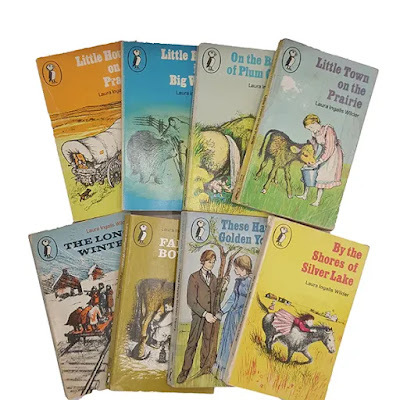

Laura Ingalls Wilder: The Little House Books (1932-43)

Laura Ingalls Wilder: The Little House Books (1932-43)Here they all are, in the 1970s Puffin copies we read, with the charming pencil and charcoal illustrations commissioned from American artist Garth Williams for a uniform edition in the late 1940s / early 1950s:

Little House in the Big Woods (1932)Farmer Boy (1933)Little House on the Prairie (1935)On the Banks of Plum Creek (1937)By the Shores of Silver Lake (1939)The Long Winter (1940)Little Town on the Prairie (1941)These Happy Golden Years (1943)

Laura Ingalls Wilder: The Little House Books (1932-43)

Laura Ingalls Wilder: The Little House Books (1932-43)The picture directly above, from Roslyn Jolly's own book-related blog, comes from a post written during the 2020 COVID lockdown in Australia. She, too, saw certain parallels between the privations described in Wilder's books and the strange new lifestyle imposed on us by the virus mandates:

That does seem to be a common theme when these books are discussed - not so much the moral lessons inculcated by them, as their direct appeals to shared experience. The Long Winter is probably my favourite among them, too. It's so much more condensed and single-minded than the others - and the settlers' failure to heed the old Indian's warning at the beginning gives a satisfying sense of poetic justice to the whole story.

The Long Winter must have made a great impression on me, because I found myself thinking of it almost as we started to find the shape of our days under the new COVID-19 restrictions. No travel. No leaving the house except for essential purposes. No meetings with anyone outside the household. The restlessness of being cooped up. Tensions flaring within the family. A growing sense of isolation from the rest of society. I’d encountered it all before, in Wilder’s book.

•

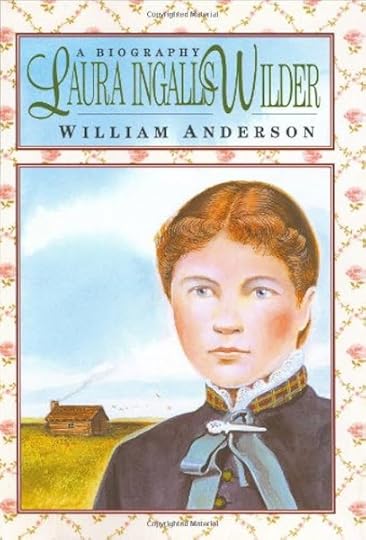

Wiliam Anderson: Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Biography (1992)

Wiliam Anderson: Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Biography (1992)Laura Ingalls Wilder scholarship, too, is certainly the province of some very engaged and single-minded enthusiasts. Before Caroline Fraser's biography was published in 2017, the main sources of information about the author were the biographies by William Anderson - who also edited Wilder's Selected Letters (2017) - and Pamela Smith Hill.

Pamela Smith Hill: Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Writer's Life (2007)

Pamela Smith Hill: Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Writer's Life (2007)Despite the fact that Hill also edited the 2014 annotated edition of Laura Ingalls Wilder's original 1930 autobiography, Pioneer Girl, I was surprised to find virtually no reference to her in Fraser's work. She isn't mentioned in the index, and - since Fraser's book has notes but no bibliography - it's a little difficult even to locate the details of the annotated Pioneer Girl there, either.

Pamela Smith Hill (1954- )

Pamela Smith Hill (1954- )Am I wrong to suspect some friction between the two? It certainly looks a bit like that. Fraser - one of whose previous books was entitled Rewilding the World - has solid credentials in the environmental movement. Hill, by contrast, is a children's writer and creative writing teacher with more pronounced roots in the American MidWest.

Caroline Fraser (2025)

Caroline Fraser (2025)I guess it came as a surprise to many when Laura Ingalls Wilder achieved canonisation in the Library of America series in 2012, the first purely children's writer to do so - though she's since been joined there by Madeleine L'Engle and Virginia Hamilton. The editor of their two 'Little House' volumes was Caroline Fraser:

Laura Ingalls Wilder: The Little House Books (Vol. 1: 2012)

Laura Ingalls Wilder: The Little House Books (Vol. 1: 2012) Laura Ingalls Wilder: The Little House Books (Vol. 2: 2012)

Laura Ingalls Wilder: The Little House Books (Vol. 2: 2012)Hill's version of Pioneer Girl came out two years after this. So far as I can tell, it makes no reference to the Library of America edition: either by citing its (very useful) chronology or its bibliographical details. Hill's latest word on the subject is, however, due to appear from the University of Nebraska Press in a couple of months time:

Pamela Smith Hill: Too Good to Be Altogether Lost (2025)

Pamela Smith Hill: Too Good to Be Altogether Lost (2025)Curiously enough, Caroline Fraser - but not Pamela Smith Hill - was asked to contribute to a 2017 symposium of essays on Wilder which appeared under the same auspices as the annotated Pioneer Girl.

Nancy Tystad Koupal, ed.: Pioneer Girl Perspectives: Exploring Laura Ingalls Wilder (2017)

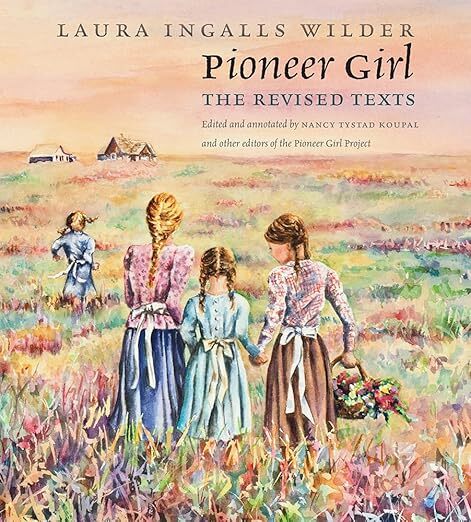

Nancy Tystad Koupal, ed.: Pioneer Girl Perspectives: Exploring Laura Ingalls Wilder (2017)And, lest that be seen as an accidental omission, it's perhaps equally significant that the editors of the "Pioneer Girl project" have gone on to supplement Pamela Smith Hill's syncretic version of Wilder's original scribbled pencil manuscript with a new edition of the original revised typescripts of her autobiography.

Nancy Tystad Koupal, ed: Pioneer Girl: The Revised Texts (2022)

Nancy Tystad Koupal, ed: Pioneer Girl: The Revised Texts (2022)Mind you, I could easily be seeing friction where there's actually mutual respect - either that, or complete indifference. I somehow doubt it, though. The world of scholarship is not exactly replete with constructive, happy rivalries. Caroline Fraser's mainstream triumphs - the Library of America, the Pulitzer Prize - have ended up putting Pamela Smith Hill rather in the shade, whether intentionally or not.

•

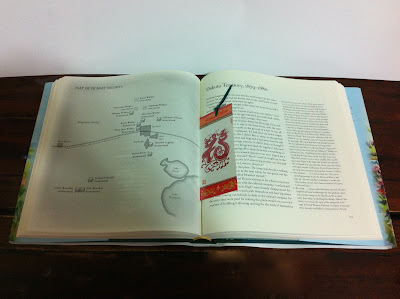

Laura Ingalls Wilder: Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography (2014)

Laura Ingalls Wilder: Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography (2014)The real winners, though, are undoubtedly readers such as myself. I certainly found the annotated Pioneer Girl a wonderfully immersive book. As Marthe Bijman remarks in her review of it on the Seven Circumstances site:

The text of Wilder’s original Pioneer Girl memoir is reproduced in the book, and contrasted and highlighted with copious, and I do mean copious, annotations, references and explanations.

Laura Ingalls Wilder: Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography (2014)

Laura Ingalls Wilder: Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography (2014)It is hard to fault in that regard. The maps are clear and well-placed, and the pictures - such as the Helen Sewell illustration above - judiciously chosen for maximum impact. As something of a connoisseur of annotated editions, I'd have to rate this one in the top ten percent for both entertainment and information. It's perhaps a little large for casual reading, but then that is the norm for such books.

Bijman stresses that, while "Pioneer Girl is much more complicated and personal than the books":

This is the definitive guide to Laura Ingalls Wilder and her life from to 1869 in Kansas to 1888 in Dakota Territory. Almost every word in the memoir has been annotated and the references are detailed, with documents, photos, registers and archival materials. Yes, the Little House books have lost some of their charm because I now understand they are more fiction than autobiographical – but there is still magic in the books.

•

Caroline Fraser: Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder (2017)

Caroline Fraser: Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder (2017)As for Caroline Fraser's work, the chorus of praise it's attracted really speaks for itself. It should be stressed, however, that this is a warts-and-all biography which omits none of the unfortunate contradictions between the reality of Laura Ingalls Wilder's life and the neat resolutions imposed on it by her autobiographical fictions.

It's not so much a simple life-and-times, as an expert weaving of American history in all its variety and violence into an account of the crippling hardships suffered by the Ingalls family and their neighbours during the late, post-Civil War period of Westward Expansion.

John Gast: American Progress (1872)

John Gast: American Progress (1872)From the Dakota war of 1862, with its barbarous aftermath of mass executions and enforced displacement of the Sioux people; through the homesteading era, with its droughts and locust infestations; all the way to the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression, Fraser points out the hidden significances behind Wilder's apparently ingenuous and factual books.

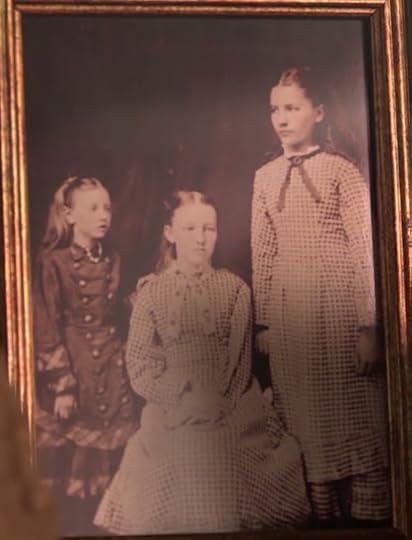

Carrie, Mary, & Laura Ingalls (c.1879)

Carrie, Mary, & Laura Ingalls (c.1879)In particular, she traces the vexed relationship between Laura Ingalls Wilder and her daughter Rose Wilder Lane, herself a celebrated writer in the 1920s and 30s - though she's now better known as one of the ideologues (along with Ayn Rand) behind the American libertarian movement.

Lane was both her mother's Maxwell Perkins, the editorial presence who inspired and helped to shape her books, and her nemesis: a conscienceless spirit of misrule, who alternately longed for and repudiated her family but could never really separate herself from them.

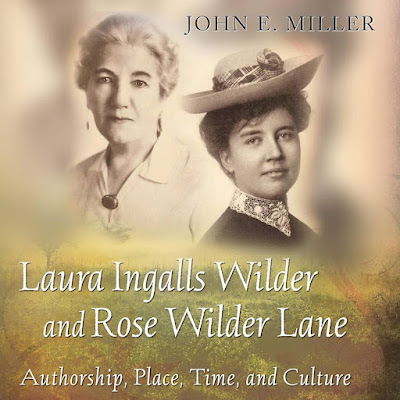

John E. Miller: Laura Ingalls Wilder & Rose Wilder Lane (2022)

John E. Miller: Laura Ingalls Wilder & Rose Wilder Lane (2022)All in all, it's a rattling good yarn - every bit as good as any of Wilder's own. It's hard to imagine any serious study or appreciation of the Little House books being possible in the future without a thorough grounding in Caroline Fraser's insights. But it's also easy to see how much it must have offended some of Wilder's more conservative admirers when it first came out.

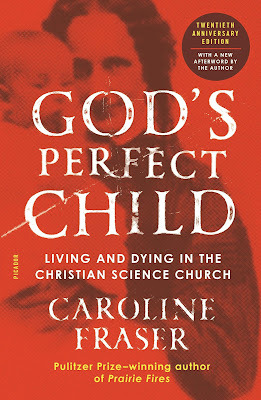

Given that Fraser's previous books include God's Perfect Child (1999), an account of her upbringing in the Christian Science Church - described as follows in a New York Times review by Philip Zaleski: "Few darker portraits of [Mary Baker Eddy] have emerged since the days when Mark Twain called her a brass god with clay legs" - her status as a tearer-down of false gods is undeniable.

Caroline Fraser: God's Perfect Child (1999)

Caroline Fraser: God's Perfect Child (1999)That great sceptic and authority on the lunatic fringe, Martin Gardner, said of her:

No one has written more entertainingly and accurately than Fraser about the history of Christian Science ... No one has more colorfully covered the ... endless bitter schisms and bad judgments that have dogged it ...Anita Sethi, in her turn, has praised Prairie Fires for demonstrating that "Memories can be both 'treasures' and 'consuming fires of torment':

Caroline Fraser’s rigorously researched biography shows how [Laura Ingalls Wilder]’s life was so much more painful than it appears in her autobiographical writings ... At its best, the book displays both the perils and the power of memory.

•

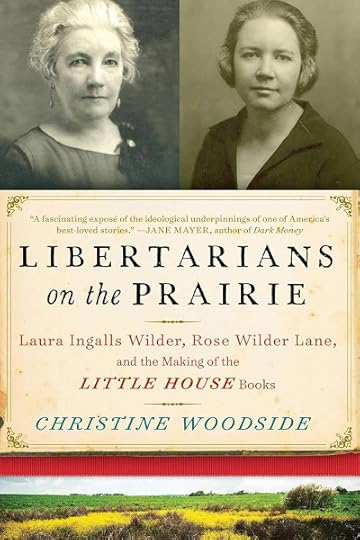

Christine Woodside: Libertarians on the Prairie (2016)

Christine Woodside: Libertarians on the Prairie (2016)In the dark days we're living through at present, with a USA which has revived its delusions of Manifest Destiny in a globalised world no longer equipped to co-exist with them, the parable of Laura Ingalls Wilder's actual life, and self-created legend, seems to have particular significance.

American exceptionalism; American lives; American this, that and the other ... the unfortunate elision of this adjective with the word "human" is something we've had to put up with for many years now. But whether any of us like it or not, I doubt that this collective mirage can survive for much longer.

Americans are notorious for being both their own bitterest critics and their own windiest boosters. It's nice to take confirmation from Caroline Fraser's excellent, hard-hitting book, that the defenders of the former tradition are alive and well and ready to do battle for the meaning of their history - which may, ominously, turn out to be the shape of their own future.

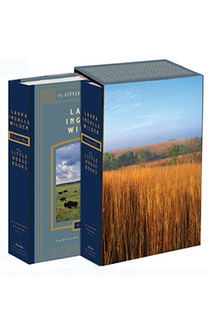

Laura Ingalls Wilder: The Little House Books: Boxed Set (Library of America: 2012)

Laura Ingalls Wilder: The Little House Books: Boxed Set (Library of America: 2012)•

Laura Ingalls Wilder (1885)

Laura Ingalls Wilder (1885)Laura Elizabeth Ingalls Wilder

(1867-1957)

The Little House books:

Little House in the Big Woods. Illustrated by Helen Sewell (1932)Little House in the Big Woods. 1932. Illustrated by Garth Williams. Puffin Books. 1963. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978. Farmer Boy. Illustrated by Helen Sewell (1933)Farmer Boy. 1933. Illustrated by Garth Williams. Puffin Books. 1972. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1981. Little House on the Prairie. Illustrated by Helen Sewell (1935)Little House on the Prairie. 1935. Illustrated by Garth Williams. Puffin Books. 1964. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1975. On the Banks of Plum Creek. Illustrated by Helen Sewell & Mildred Boyle (1937)On the Banks of Plum Creek. 1937. Rev. ed. 1953. Illustrated by Garth Williams. Puffin Books. 1965. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1974. By the Shores of Silver Lake. Illustrated by Helen Sewell & Mildred Boyle (1939)By the Shores of Silver Lake. 1939. Illustrated by Garth Williams. Puffin Books. 1967. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972. The Long Winter. Illustrated by Helen Sewell & Mildred Boyle (1940)The Long Winter. 1940. Illustrated by Garth Williams. Puffin Books. 1968. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1980. Little Town on the Prairie. Illustrated by Helen Sewell & Mildred Boyle (1941)Little Town on the Prairie. 1941. Illustrated by Garth Williams. Puffin Books. 1969. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978. These Happy Golden Years. Illustrated by Helen Sewell & Mildred Boyle (1943)These Happy Golden Years. 1943. Illustrated by Garth Williams. Puffin Books. 1970. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971. The Little House Books, Vol. 1. Ed. Caroline Fraser. Library of America, 229 (2012)Little House in the Big Woods (1932)Farmer Boy (1933)Little House on the Prairie (1935)On the Banks of Plum Creek (1937) The Little House Books, Vol. 2. Ed. Caroline Fraser. Library of America, 230 (2012) By the Shores of Silver Lake (1939)The Long Winter (1940)Little Town on the Prairie (1941)These Happy Golden Years (1943)The First Four Years (1971)

Published posthumously:

On the Way Home: The Diary Of A Trip From South Dakota To Mansfield, Missouri in 1894. Ed. Rose Wilder Lane (1962)The First Four Years (1971)The First Four Years. 1971. Epilogue by Rose Wilder Lane from "On the Way Home". 1962. 1973. Puffin Books. 1978. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1981. West From Home: Letters Of Laura Ingalls Wilder, San Francisco, 1915. Ed. Roger Lea MacBride (1974)A Little House Sampler. With Rose Wilder Lane. Ed. William Anderson (1988 / 1989)Little House in the Ozarks: The Rediscovered Writings. Ed. Stephen W. Hines (1991)Laura Ingalls Wilder & Rose Wilder Lane, Letters 1937–1939. Ed. Timothy Walch (1992)Laura Ingalls Wilder Farm Journalist: Writings from the Ozarks. Ed. Stephen W. Hines (1997)A Little House Reader: A Collection of Writings. Ed. William Anderson (1998)Laura's Album: A Remembrance Scrapbook of Laura Ingalls Wilder. Ed. William Anderson (1998)Laura Ingalls Wilder's Fairy Poems. Ed. Stephen W. Hines. Illustrated by Richard Hull (1998)A Little House Traveler: Writings from Laura Ingalls Wilder's Journeys Across America (2006)On the Way Home (1894)West from Home (1915)The Road Back Home (1931) Writings to Young Women. Ed. Stephen W. Hines (2006)On Wisdom and VirtuesOn Life as a Pioneer WomanAs Told by Her Family, Friends, and Neighbors Before the Prairie Books: The Writings of Laura Ingalls Wilder 1911–1916: The Small Farm. Ed. Dan L. White (2010)Before the Prairie Books: The Writings of Laura Ingalls Wilder 1917–1918: The War Years. Ed. Dan L. White (2010)Before the Prairie Books: The Writings of Laura Ingalls Wilder 1919–1920: The Farm Home. Ed. Dan L. White (2010)Before the Prairie Books: The Writings of Laura Ingalls Wilder 1921–1924: A Farm Woman. Ed. Dan L. White (2010)Laura Ingalls Wilder's Most Inspiring Writings: Covering the Years 1911 Through 1924. Ed. Dan L. White (2015)Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Pioneer Girl's World View: Selected Newspaper Columns (2014)Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography. Ed. Pamela Smith Hill (2014)Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography. Ed. Pamela Smith Hill. A Publication of the Pioneer Girl Project: Nancy Tystad Koupal, Director; Rodger Hartley, Associate Editor; Jeanne Kilen Ode, Associate Editor. Pierre: South Dakota Historical Society Press, 2014. The Selected Letters of Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Pioneer's Correspondence. Ed. William Anderson (2017)Pioneer Girl: The Revised Texts. Ed. Nancy Tystad Koupal (2022)

Secondary:

Zochert, Donald. Laura: The Life of Laura Ingalls Wilder (1976)Anderson, William. Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Biography (1992)Holtz, William. The Ghost in the Little House: A Life of Rose Wilder Lane (1993)Miller, John E. Becoming Laura Ingalls Wilder: The Woman Behind the Legend (1998)Hill, Pamela Smith. Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Writer's Life (2007)Miller, John E. Laura Ingalls Wilder and Rose Wilder Lane: Authorship, Place, Time, and Culture (2008)Pioneer Girl Perspectives: Exploring Laura Ingalls Wilder. Ed. Nancy Tystad Koupal (2017)Fraser, Caroline. Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder. Metropolitan Book. New York: Henry Holt And Company, 2017.Hill, Pamela Smith. Too Good to Be Altogether Lost: Rediscovering Laura Ingalls Wilder's Little House Books (2025)

Laura Ingalls Wilder (1951)

Laura Ingalls Wilder (1951)•

Published on April 12, 2025 13:17

April 1, 2025

Favourite Children's Authors: Peter Dickinson

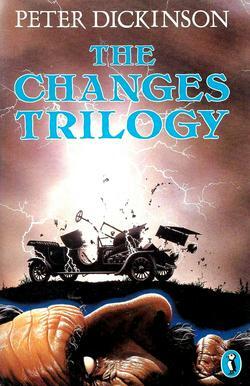

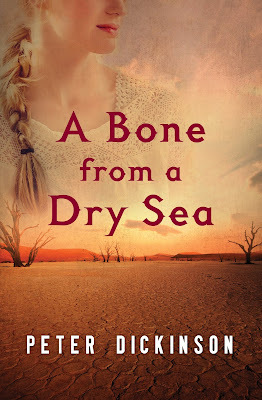

Peter Dickinson: The Changes Trilogy (1975)

Peter Dickinson: The Changes Trilogy (1975)When Robert Lowell's groundbreaking collection Life Studies first came out in the UK in 1959, "the British reviews were fairly tepid." After listing the reservations of such luminaries as Al Alvarez, G. S. Fraser, Roy Fuller, Frank Kermode, and Philip Larkin, Lowell's biographer Ian Hamilton throws in as a parthian shot:

... and someone called Peter Dickinson in Punch announced that "few of the poems are in themselves memorable."- Ian Hamilton, Robert Lowell: A Biography (1982): 269.Nice going. They didn't call Hamilton "Mr. Nasty" for nothing. That "someone called Peter Dickinson" was, admittedly, not very well known for anything much at the time - besides being the literary editor of Punch, that is.

His first detective novels were still some years in the future, and it'd be another decade before he started publishing the children's books which would, eventually, make his name. But even so ... "Do you have to leave blood on the floor at the end of every meeting?" as an academic of my acquaintance once said to an up-and-coming careerist in the same field.

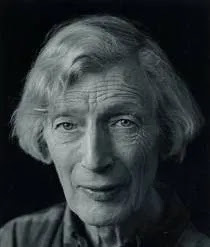

Fay Godwin: Peter Dickinson (1975)

Fay Godwin: Peter Dickinson (1975)I used to wonder why Dickinson used to claim, at the end of his "About the Author" blurbs:

His main interest, he says, "is writing verse. A lost art, in the way I do it. I feel like a man making wooden carriage wheels for the one customer who wants them."A collection of these "verses", The Weir (2007), was eventually published by his four children as a birthday tribute a few years before his death. Here's a sample, from an advertisement for the book: