Jack Ross's Blog, page 9

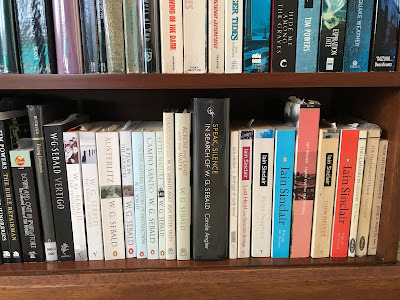

October 29, 2022

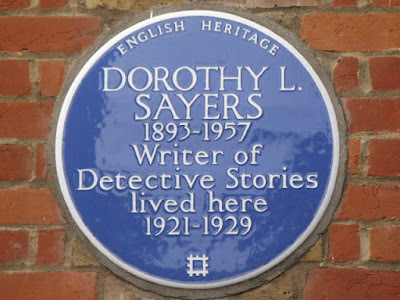

What the Dickens?

Edmund Wilson: Eight Essays (1954)

Edmund Wilson: Eight Essays (1954)Can All These Biographies be of the Same Man?

In his celebrated essay "The Two Scrooges," published in The New Republic in 1940, and subsequently collected in The Wound and the Bow (1941), American critic Edmund Wilson claimed to have detected a curious dichotomy in Charles Dickens's work. It is, according to Wilson:

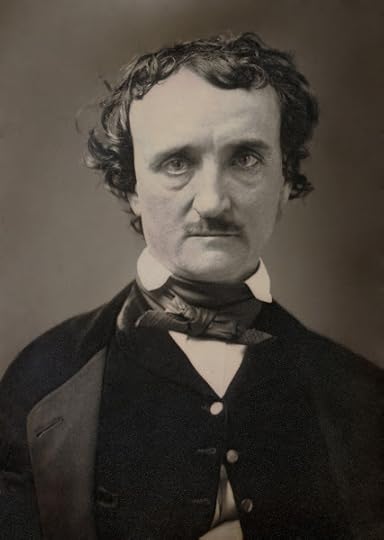

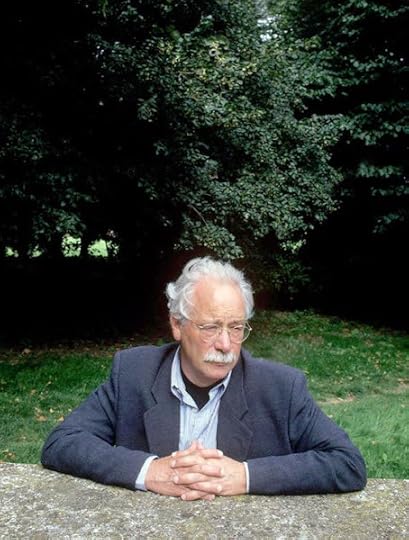

Edmund Wilson (1895-1972)

Edmund Wilson (1895-1972)organized according to a dualism which is based ... on the values of melodrama: there are bad people and there are good people, there are comics and there are characters played straight. The only complexity of which Dickens is capable is to make one of his noxious characters become wholesome, one of his clowns turn out to be a serious person. The most conspicuous example of this process is the reform of Mr. Dombey, who, as Taine says, “turns into the best of fathers and spoils a fine novel.”Earlier this year I posted a piece called "The World of Charles Dickens." In it I attempted to give a quick overview of my various collections of Dickens books, films and other ephemera (including jigsaw puzzles). But I only had space there to make a few references to the fascinating - and distinctly vexed - realm of Dickens biography. This is the brief summary I gave:

•

Michael Slater: Charles Dickens (2007)

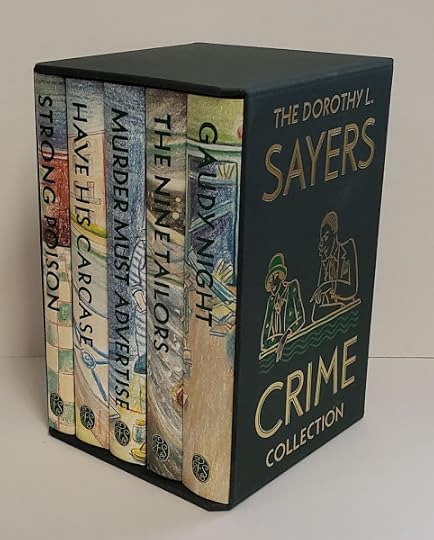

Michael Slater: Charles Dickens (2007)There are many biographies. At times it can seem as if the majority even of bookish people are far less keen on reading him than reading about him. The original Victorian biography by John Forster is still an essential source, and I must confess, too, to a soft spot for Edgar Johnson's exhaustive two-volume account of 1952.Claire Tomalin: The Invisible Woman: The Story of Nelly Ternan and Charles Dickens (1990)

I'm not myself a great admirer of Peter Ackroyd's strange biography-with-fictional-interludes, though it certainly has its moments. A far more significant contribution to scholarship came from Claire Tomalin's The Invisible Woman: a biography of Dickens's mistress Nelly Ternan, which appeared in the same year, 1990.Claire Tomalin: Charles Dickens: A Life (2011)

She's followed this up since with a full-dress biography of Dickens, perhaps meant as a riposte to Michael Slater's, also pictured above. Slater is, after all, a bit of a Ternan-sceptic, witness his book The Great Charles Dickens Scandal (2012), which takes issue with many of Tomalin's points.

In any case, whatever your views on this or other contentious points, you won't find too much difficulty in finding material to your taste in the vast untidy field of Dickens scholarship. Even the famously critical Frank Leavis finally decided to admit him to the fold of the 'great tradition' in English fiction.

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens' London: An Imaginative Vision. London: Headline Book Publishing PLC., 1987.Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens. London: Sinclair-Stevenson Ltd., 1990.Forster, John. The Life of Charles Dickens. With Thirty-Two Illustrations. 1872-74. London: Humphrey Milford / Oxford University Press, n.d.Johnson, Edgar. Charles Dickens. His Tragedy and Triumph. 2 vols. New York: Simon and Schuster Inc., 1952.Pope-Hennessy, Una. Charles Dickens: 1812-1870. 1945. London: The Reprint Society, 1947.Slater, Michael. Dickens and Women. 1983. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1986.Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens. 2009. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2011.Slater, Michael. The Great Charles Dickens Scandal. 2012. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2014.Tomalin, Claire. The Invisible Woman: The Story of Nelly Ternan and Charles Dickens. 1990. London: Penguin, 1991.Tomalin, Claire. Charles Dickens: A Life. 2011. London: Penguin, 2012.

F. R. & Q. D. Leavis: Dickens the Novelist (1970)

F. R. & Q. D. Leavis: Dickens the Novelist (1970)•

Michael Slater: The Great Charles Dickens Scandal (2012)

Michael Slater: The Great Charles Dickens Scandal (2012)Having now had time to think (and read) some more on the subject, I'd like to expand a bit on that rather bald account. Who exactly was Dickens? How is it possible for two biographies so thoroughly different as Michael Slater's (2007) and Claire Tomalin's (2011) to be published so hard on each other's heels?

It's not so much the protean nature of Dickens the man I mean to call into question: all of us are complex, contradictory, 'a million different people from one day to the next,' as the Verve's 1997 song "Bitter Sweet Symphony" so memorably puts it.

No, what interests me is the extent to which the 'Dickens' of these books resembles Wilson's analysis, quoted above, of the melodramatic assumptions underlying Dickens' own early work: "there are bad people and there are good people, there are comics and there are characters played straight."

Claire Tomalin (b.1933)

Claire Tomalin (b.1933)Tomalin, it's true to say, does her best to maintain an even playing field. She begins her own biography with an inspiring anecdote about the lengths to which Dickens was prepared to go to help the poor and downtrodden, when - as a juror on a murder case - he fought tooth and nail for the acquittal and subsequent welfare of a young servant girl accused of killing her own child. Dickens, that is to say, as crusader. And you'd have to be pretty jaded not to be impressed by the sheer extent of Dickens' involvement in the case. He just wouldn't let it go. It was no momentary spasm of indignation on his part, but a lifelong commitment.

Unfortunately, in context, this story simply serves as a prelude to Tomalin's very persuasive portrait of Dickens as a tyrannical husband and neglectful papa - not to mention dastardly seducer. Edmund Wilson, too, highlights these traits, remarking that Dickens seems, at times, "almost as unstable as Dostoevsky."

He was capable of great hardness and cruelty, and not merely toward those whom he had cause to resent ... his treatment of Mrs. Dickens suggests, as we shall see, the behavior of a Renaissance monarch summarily consigning to a convent the wife who had served her turn. There is more of emotional reality behind Quilp in The Old Curiosity Shop than there is behind Little Nell. If Little Nell sounds bathetic today, Quilp has lost none of his fascination. He is ugly, malevolent, perverse; he delights in making mischief for its own sake; yet he exercises over the members of his household a power which is almost an attraction ... Though Quilp is ceaselessly tormenting his wife and browbeating the boy who works for him, they never attempt to escape: they admire him; in a sense they love him.For Wilson, Dickens' work as a whole is a haunted palace, full of neglected corridors leading to unspeakable secrets: the very epitome of Gothic melodrama. And he wrote like that because that's how he lived:

Dickens’ daughter, Kate Perugini, who had destroyed a memoir of her father that she had written, because it gave “only half the truth,” told Miss Gladys Storey, the author of Dickens and Daughter, that the spell which Dickens had been able to cast on his daughters was so strong that, after his separation from their mother, they refrained, though he never spoke to them about it, from going to see her, because they knew he did not like it ... “I loved my father,” Miss Storey reports her as saying, “better than any man in the world — in a different way of course. … I loved him for his faults.” And she added, as she rose and walked to the door: “My father was a wicked man — a very wicked man.” But from the memoir of his other daughter Mamie, who also adored her father and seems to have viewed him uncritically, we hear of his colossal Christmas parties, of the vitality, the imaginative exhilaration, which swept all the guests along.Like Scrooge himself, the ostensible subject of Wilson's essay, Dickens sounds like "the victim of a manic-depressive cycle, and a very uncomfortable person."

How, then, does Michael Slater deal with all this, in his own comprehensive biography of the author?

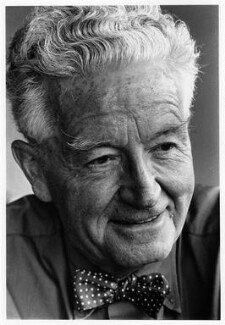

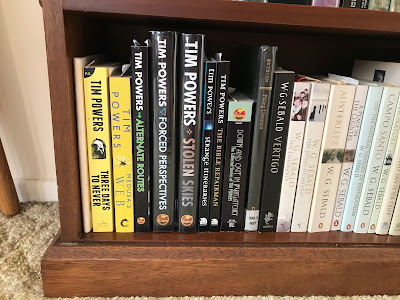

Michael Slater (b.1936)

Michael Slater (b.1936)Well, for the most part he ignores it, that's how. From the very first pages of his biography, he makes it clear that it's only really Dickens the Victorian man-of-letters who interests him, and whom he feels qualified to write about.

Professor Slater comments in great detail on the idea of serial publication, pioneered in The Pickwick Papers, and then carried on via a variety of vehicles: the monthly numbers used for such novels as Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby, and their various successors; but also the succession of weekly periodicals Dickens edited, among them Master Humphrey's Clock (1840-41), home of The Old Curiosity Shop; Household Words (1850-59), where he published Hard Times and A Child's History of England; and, finally, All the Year Round (1859-90), which eventually housed A Tale of Two Cities, Great Expectations, and The Uncommercial Traveller.

That's just the beginning for Slater, though. Amateur theatricals, occasional journalism, travel books, editing jobs such as the great clown Grimaldi's memoirs - all are woven together into a marvellous tapesty of mid-Victorian cultural life. His four-volume annotated edition of Dickens's collected journalism stands him in good stead when it comes to documenting and - above all - making sense of this mountain of circumstantial detail.

This is his crucial break with what might be called the Wilsonian tradition of Freudian (or at least psychoanalytical) criticism, as it's been applied to Dickens since the appearance of "The Two Scrooges" in the 1940s. The first biographer to employ these insights, albeit sparingly, was probably Una Pope-Hennessy in her wonderfully compact Charles Dickens: 1812-1870 (1945).

Edgar Johnson (1902-1995)

Edgar Johnson (1902-1995)The major monument to this tradition would, however, have to be Edgar Johnson's exhaustive two-volume critical biography Charles Dickens: His Tragedy and Triumph (1952). Johnson's "life and times" approach - which he applied again, a couple of decades later, to his similarly vast biography of Sir Walter Scott, The Great Unknown (1970) - has been found offputting by some (Peter Ackroyd principal among them). For myself, I love it.

I can see the advantages of focussing principally on Dickens's emotional life, as Tomalin does, or his professional life, as Slater does, but Johnson's system of alternating chapters of pure biography with chapters of analysis of each of Dickens's major works is surprisingly successful. Certainly one emerges from such a reading with a vivid knowledge of each of the novels as well as the minutiae of the novelist's life.

In Slater's terms, Johnson is a 'believer' - one who accepts that Nelly Ternan was Dickens's mistress, and that their relationship was almost certainly a sexual one. So is Pope-Hennessy. And Tomalin, of course, is the high priest of this tradition. Peter Ackroyd, whom I'll come to in a minute, is on the fence. He accepts the evidence of Ternan's importance in Dickens' life, but finds it unlikely that their relationship was ever consummated: his Dickens is far too weird for that. Michael Slater, of course, is the leader of the Denialist school who insists - quite correctly - on the extreme flimsiness of the evidence so far produced for the actual existence of this relationship.

Eppur si muove would be my own conclusion on this vexed matter, thrashed out so thoroughly in so many books over the last century or so. That's what Galileo is alleged to have said as he emerged from the Church tribunal which had just forbidden him to assert as fact the Earth's progress around the Sun: "but it does move, anyway." I just can't bring myself to believe that the whole affair is based on moonshine and a few misunderstood letters. It was too big a scandal to suppress at the time, and salutary though Slater's subsequent attempts to point out the deficiencies of the opposition's case have been, I fear that I would have to award the victory to Tomalin on this one, on points.

Peter Ackroyd (b.1949)

Peter Ackroyd (b.1949)Which brings us to undoubtedly the strangest of all of the modern biographies, Peter Ackroyd's Dickens (1990). Ackroyd's decision to incorporate fictional 'episodes', evocative dreamscapes a little reminiscent of some of De Quincey's opium visions, caused a great deal of comment at the time. Whether or not it's effective, it's certainly different - and while these sections co-exist rather oddly with the rest of his heavily researched text, it can't simply be written off as a failure. There's something in it, though it's not quite clear (to me, at least) just what.

Ackroyd's main innovation as a biographer, though, was his heavy dependence on the backfiles of The Dickensian, the Dickens-enthusiasts' journal which has been charting every minute detail of the Master's work since 1905. This immense heap of articles provided him with ammunition for his demolition of the Johnsonian life-and-times approach. Johnson's research turns out to have been largely library-based, whereas Ackroyd is able to explore both the texts and the landscapes through the eyes of legions of fanatical (and, for the most part, footsore) contributors to The Dickensian.

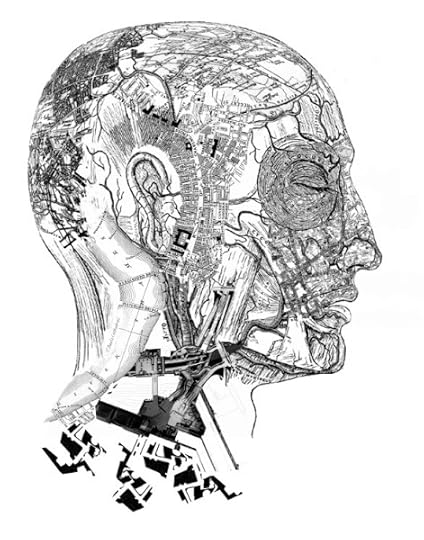

This does impart a curiously patchwork tone to Ackroyd's text, but given his devotion to psychogeography as a discipline, it also serves to highlight the strange interfusion he posits between Dickens and London, the city that defined him both as an author and a man, expanding in this on his earlier picture book Dickens' London: An Imaginative Vision.

Ackroyd was, however, somewhat handicapped by the fact that the magisterial Pilgrim edition of Dickens' complete letters (12 vols, 1965-2002) was not yet complete while he was writing. All subsequent biographies and scholarship on Dickens have been dominated by this massive piece of research, entailing, as it did, an exact charting of his doings on virtually every day of his adult life. Like his predecessors Pope-Hennessy and Johnson, Ackroyd was still forced to resort at times to the woefully incomplete Nonesuch edition of Dicken's correspondence (3 vols, 1938).

Charles Edward Perugini: John Forster (1812-1876)

Charles Edward Perugini: John Forster (1812-1876)Might it be said, in fact, that we know a bit too much about Dickens nowadays? The dichotomy between Slater and Tomalin's work seems a bit less surprising when you factor in the sheer weight of material at a modern biographer's fingertips: as well as those 12 volumes of letters, and the serried rows of back-issues of the Dickensian, there are books and articles on virtually every aspect of his life. One must, in other words, be selective: especially if you're trying desperately to cram your conclusions into a single manageable volume.

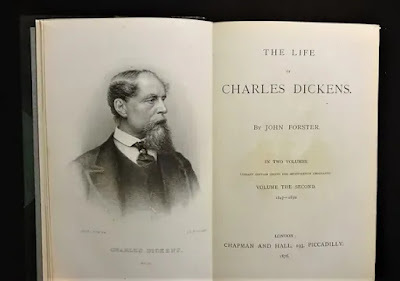

Which brings me to the great-grandaddy of all Dickens biographies, John Forster's Life of Charles Dickens (3 vols, 1872-74). Forster was a close friend of Dickens, and supported and counselled him at all stages of his professional life - not always successfully. He was also an accomplished biographer and man of letters in his own right, author of Oliver Goldsmith: His Life and Times (1848) as well as a life of the poet Walter Savage Landor (1868) - reputedly the original for the character Boythorne in Bleak House.

Lytton Strachey: The Illustrated Eminent Victorians (1989)

Lytton Strachey: The Illustrated Eminent Victorians (1989)Ever since Lytton Strachey did his demolition job on Victorian biographies in Eminent Victorians (1918), there's been a reaction against those respectable, four-square, generally multi-volumed Life and Letters which used to be the mainstay of every library. Many modern readers have got out of the habit of reading them at all, assuming that all the interesting stuff will have been edited out of them according to the wishes of the family, and that what is left will be, at best, the record of a whited sepuchre.

I haven't found it to be so. Forster's biography of Dickens is a masterpiece: famously revelatory of the sufferings of his early boyhood, but wonderfully vivid at every turn. It reads, in fact, like a Victorian three-decker - though probably not one of Dickens' own: more like a novel by Trollope or Thackeray. Often he says things so well that, given the fact that he was also saying them for the first time, there was not a lot to be added to his account subsequently.

John Forster: Life of Charles Dickens (1872-74)

John Forster: Life of Charles Dickens (1872-74)If I had to recommend one biography of Dickens, I'd probably recommend Forster's. For myself, I have an abiding love for Edgard Johnson's, but it is very long, and the abridged one-volume version (which is probably the one most people read) doesn't really do justice to his overall concept.

I once met Professor Michael Slater. It was at a conference at Auckland University, some 25 years ago. He gave a wonderful paper on Douglas Jerrold, and proved to be the gentlest, sunniest, kindest gentleman I think I've ever encountered at such an event. There was not the slightest self-vaunting or sidiness about him, though he was certainly keen to expound the merits of the new edition of Dickens's journalism he was then working on. I'm predisposed in his favour, in other words.

If you're interested mainly in Dickens as a writer, then Slater is the biographer for you. His book is tough going at times, but he keeps all the balls in the air with marvellous dexterity, and the painfully accumulated detail all comes home to roost if you're prepared to persevere.

If you're interested - in Wilsonian style - in the tormented genius behind the books, then Tomalin's biography will suit you much better. It's a more mature book in every way than The Invisible Woman - fascinating though the earlier book was, that particular job only needed to be done once. Tomalin bends over backwards to try to understand Dickens' point of view, but he was just a very difficult man to like - unless you were prepared just to sit back and enjoy the show, as so many of his friends and acquaintances were. His family and his business associates did not have that option, unfortunately.

But do any of these books really get us much closer to Dickens himself? You can end up knowing more raw information about him than you know about any other human being you ever met, and still be struck by how mysterious he seems. His innermost personality - even the most important details of his emotional life - seems, in the end (as the poet said of Robert E. Lee), secure from "the picklocks of biographers":

For he will smile

And give you, with unflinching courtesy,

Prayers, trappings, letters, uniforms and orders,

Photographs, kindness, valor and advice,

And do it with such grace and gentleness

That you will know you have the whole of him

Pinned down, mapped out, easy to understand —

And so you have.

All things except the heart.

...

For here was someone who lived all his life

In the most fierce and open light of the sun,

Wrote letters freely, did not guard his speech,

Listened and talked with every sort of man,

And kept his heart a secret to the end

From all the picklocks of biographers.

Stephen Vincent Benét: from 'Robert E. Lee' (1928)

Robert William Buss: Dickens's Dream (1875)

Robert William Buss: Dickens's Dream (1875)

Published on October 29, 2022 12:46

September 24, 2022

Time Travel and Beyond

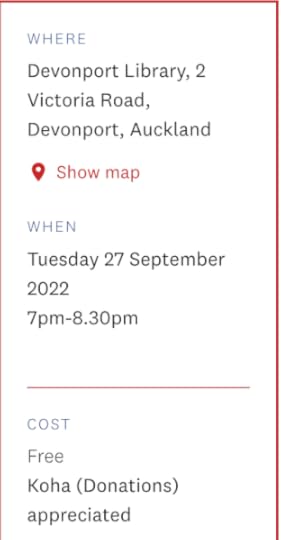

Bryan Walpert: Entanglement (2021)

Bryan Walpert: Entanglement (2021)Time Travel and Beyond

Is time travel possible? Why write another novel about it?

Jack Ross chats with Bryan Walpert, Devonport resident and author of the 2022 Ockham short-listed novel Entanglement, about time travel, the challenge of putting science into a novel, crossing the border from poetry to fiction, science fiction vs. science-in-fiction, and more.

Books will be available for purchase.

•

As a researcher [at the Centre for Time at the University of Sydney] was settling me into my cubicle, he gave me some advice: Don’t think about it too hard and you’ll know what time it is; think about it too much and you’ll confuse yourself. As it turns out, this more or less describes our relationship with time as expressed by St Augustine some 1800 years ago. He wrote, “What then is time? If no one asks me, I know what it is. If I wish to explain it to him who asks, I do not know.”Luckily for me, Bryan has already given us some pretty strong clues about how to interpret his novel Entanglement. In particular, the notion of whether or not the past and future are 'really' there is canvassed quite extensively:

Somewhat stranger than this, to me at least, is the question of how real the past and future are. Most of us have an intuitive sense that events in the past (e.g. the French Revolution) are no longer happening and that the future doesn’t exist until we, well, get there ... This corresponds with what has been called the “tensed” theory of time or “presentism.” But there are also proponents of what’s called the “block universe” or sometimes “eternalism.” By that way of thinking, the past, present and future all exist.His Newsroom article on the subject even gives us the moment of inception of the book:

When I’m asked what led me to write Entanglement, I recall the moment some years ago that inspired it. It was a summer’s day. I was standing just outside my house, my family waiting for me inside, and felt, suddenly, as though I’d come back from the future, some darker time — though what the future was I didn’t know. My kids are so young again, I remember thinking. My wife and I are amazingly young, too.If you'd like to hear more about these weighty matters, please come along to the Devonport Library this coming Tuesday to listen to me and Bryan discussing his fascinating novel and the myriad questions it poses.

I felt like I had been given another chance. I thought, There are so many mistakes I hadn’t yet made. It was a strange and powerful feeling, though it didn’t last — the moment passed. Or maybe the moment is still and eternally there in its little corner of the block universe ...

– Bryan Walpert, ‘Is time travel possible? Yes-ish’ Newsroom (3/3/22)

Once again, this event has been made possible by the Devonport Library Associates: chair Jan Mason, events organiser Paul Beachman, and publicity courtesy of Linda Hopkins.

•

Bryan Walpert

Bryan Walpert

Bryan Walpert is the author of four books of poems, most recently Brass Band to Follow (Otago UP), named among the top 10 poetry collections of 2021 by the NZ Listener. He is also the author of three books of fiction, including the novel Entanglement, short-listed for the Jann Medlicott Acorn Prize for Fiction at the 2022 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards. A Devonport resident, he is a Professor of Creative Writing at Massey University-Albany.

•

Te Pātaka Kōrero o Te Hau Kapua / Devonport Library

Te Pātaka Kōrero o Te Hau Kapua / Devonport Library•

Published on September 24, 2022 13:32

September 11, 2022

Breaking the Maya Code

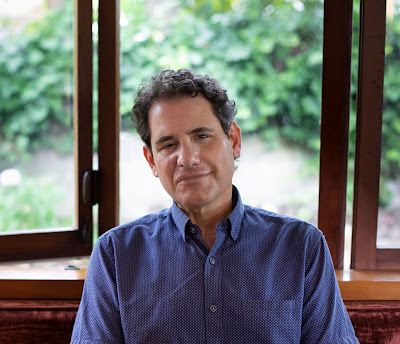

William Carlsen: Jungle of Stone (2016)

William Carlsen: Jungle of Stone (2016)William Carlsen. Jungle of Stone: The Extraordinary Journey of John L. Stephens & Frederick Catherwood, and the Discovery of the Lost Civilisation of the Maya. 2016. William Morrow. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 2017.

The other day I was in a Hospice shop where I ran across a copy of the book above, priced at the princely sum of $4. I promptly bought it, of course, mainly because the blurb proclaimed it to be in the 'tradition of Lost City of Z and In the Kingdom of Ice'.

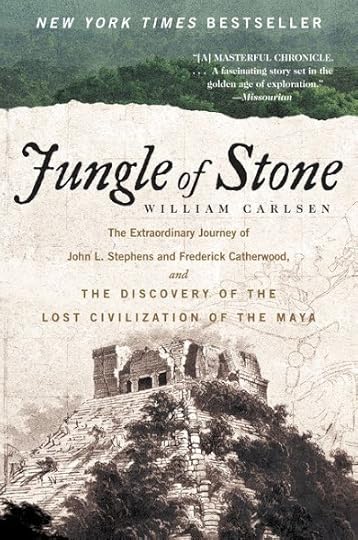

David Grann: The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon (2009)

David Grann: The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon (2009)The first of those two I'm only too familiar with, having both read the book and watched the weirdly entertaining movie, starring Charlie Hunnam as the intrepid (if somewhat misguided) Colonel Percy Fawcett, who disappeared in the Amazon jungle in 1925 and has never been seen since.

James Gray, dir.: The Lost City of Z (2016)

James Gray, dir.: The Lost City of Z (2016)I'd never heard of the second one, but it sounds very much like my kind of thing, and I'll certainly be on the lookout for a second-hand copy of it next time I'm out on the prowl:

Hampton Sides: In the Kingdom of Ice: The Grand and Terrible Polar Voyage of the USS Jeannette (2014)

Hampton Sides: In the Kingdom of Ice: The Grand and Terrible Polar Voyage of the USS Jeannette (2014)The superior attractions of Jungle of Stone, however, come both from its setting and its subject matter.

I'm rather a fan of books about the mysterious Mayan civilisation, as anyone motivated enough to have looked through my 2019 collection Ghost Stories will attest. The story 'Leaves from a Diary of the End of the World' begins with the following - lightly fictionalised - account of a not dissimilar windfall almost exactly ten years ago now:

Michael Coe: Breaking the Maya Code (1992)

Michael Coe: Breaking the Maya Code (1992)

Tuesday, 21 February, 2012:

Today I found an old book in the library, in the de-accessioned pile. It cost me two dollars to buy it (Hardback Non-fiction – if it had been Fiction, it would only have been a dollar). The title was Breaking the Maya Code, by Michael Coe.

But why on earth were they throwing it out?

It’s true that this was a copy of the first, 1992, edition, and since then – I checked – Coe has gone on to publish a number of revisions of his book (just as he did with his 1966 text The Maya, now in its eighth edition). So perhaps they thought it was too out of date to be useful.

What I suspect, though, is that they read those words ‘the Maya Code’ as something analogous to the Da Vinci Code – as a reference to the (alleged) Mayan Prediction of the end of days in December 2012.

If so, they were sorely mistaken. Far from an Occultist text full of babble about the Apocalypse, Coe’s is a profoundly scholarly work, which tells the tale of one of the greatest decipherments of all time.

The name of Yuri Valentinovich Knorosov, the Russian genius whose phonological and comparative methodology finally led to success in this two-hundred-year-old quest, should undoubtedly go down in history along with Jean-François Champollion, Michael Ventris, and other heroes of the intellect.

The fact that we can now actually read these texts from a far-off civilisation, mute for centuries, thanks solely to such feats of ingenuity is one of the few proofs I know that the cosmos is not entirely arbitrary.

Just as the patterns of Nature become clear over time when examined by the dispassionate intellect, so advances can be made in our knowledge, the stones can be made to speak.

David Lebrun, dir.: Breaking the Maya Code (2008)

David Lebrun, dir.: Breaking the Maya Code (2008)In fact, I subsequently went to the extra trouble of ordering a copy of a two-hour documentary on the subject, which I greatly recommend to anyone curious about just how precisely one goes about decoding an unknown script in an archaic version of an admittedly still living (though very complex) language.

C. W. Ceram: Gods, Graves and Scholars: The Story of Archaeology (1949 / 1951)

C. W. Ceram: Gods, Graves and Scholars: The Story of Archaeology (1949 / 1951)When it comes to Stephens and Catherwood, I did already know the rough outline of their story from early reading and rereading of the wonderfully exciting - to a nerdy teenager, at any rate - Gods, Graves and Scholars, by German journalist Kurt Wilhelm Marek (who published under the pseudonym 'C. W. Ceram').

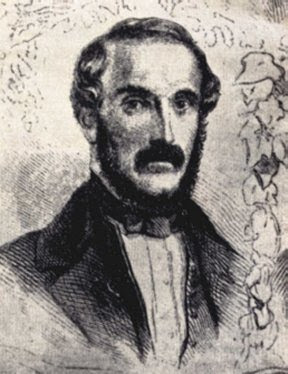

John L. Stephens (1805–1852)

John L. Stephens (1805–1852)I've written elsewhere about my interest in 19th-century American Historians such as Washington Irving, Francis Parkman and William H. Prescott, who were among the very first authors from the Western hemisphere to attract a substantial Old World audience. John Lloyd Stephens certainly has to be counted among their number.

John L. Stephens: Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, & Yucatán (1841 / 1949)

John L. Stephens: Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, & Yucatán (1841 / 1949)John L. Stephens. Incidents of Travel in Egypt, Arabia Petraea, and The Holy Land. 1837. Ed. Victor Wolfgang von Hagen. Illustrated by Frederick Catherwood. 1970. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1991.John L. Stephens. Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, & Yucatán. Illustrated by F. Catherwood. 1841. Ed. Richard L. Prodmore. 2 vols. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1949.John L. Stephens. Incidents of Travel in Yucatán. Illustrated by F. Catherwood. 2 vols. 1843. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1963.

John L. Stephens: Incidents of Travel in Yucatán (1843 / 1963)

John L. Stephens: Incidents of Travel in Yucatán (1843 / 1963)It's fair to say, though, that Stephens' two classic books about his rediscovery of the lost Mayan cities - both of which I own (and, more to the point, have read from cover to cover) - would never have known such immediate success it weren't for the work of his collaborator and illustrator, itinerant Englishman Frederick Catherwood.

Frederick Catherwood (1799-1854)

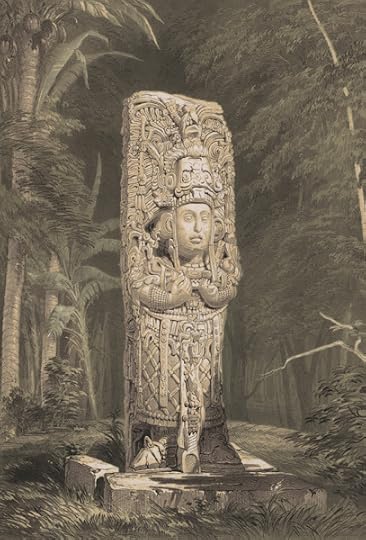

Frederick Catherwood (1799-1854)It was Catherwood whose immensely detailed and accurate sketches of Mayan inscriptions, ruins, and sculptures established beyond dispute the artistic merits of this long-vanished civilisation. Even now it's hard to imagine how they could be surpassed:

Frederick Catherwood: Stela at Copan, from Views of Ancient Monuments (1844)

Frederick Catherwood: Stela at Copan, from Views of Ancient Monuments (1844)Stephens was an exceptionally able journalist, who told a rattling good yarn. When he wasn't being threatened with instant death by murderous soldiers, he was being laid low by tropical diseases. Somehow he managed to keep going, though, despite the lawlessness of much of Central America at the time.

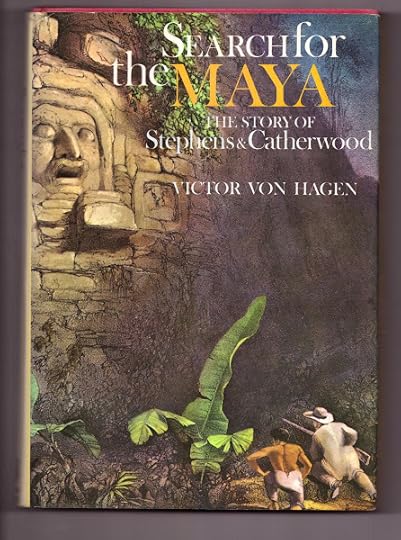

Victor von Hagen: Search for the Maya: The Story of Stephens and Catherwood (1973)

Victor von Hagen: Search for the Maya: The Story of Stephens and Catherwood (1973)It's really Catherwood one sympathises with most, however. He was often left behind at some inaccessible site to complete his sketches of the ruins while Stephens went off on some more glamorous (albeit even more dangerous) errand. Working, at times, up his ankles in mud, with jungle undergrowth obscuring his view, Catherwood used his camera lucida apparatus to trace each inscription and statue as carefully as he could.

Despite not knowing the meanings of any of the symbols he recorded, he drew them so carefully that many of his drawings are still used by Mayan scholars in preference to the original walls and statues, now further perished by time.

William Robertson (1721-1793)

Stephens and Catherwood were by no means the first to see these immense ruins, but they were certainly the most assiduous in recording and disseminating the wonders they'd found.

Thanks to the influence of sceptical British historians such as William Robertson, whose History of America (1777) threw considerable doubt on the existence of the architectural and artistic marvels described by the original Conquistadors, most people at the time still assumed that there had never been a civilisation in the Americas to rival those of Egypt and Mesopotamia. The dogmatic Scots clergyman stated it baldly:

The inhabitants of the New World were in a state of society so extremely rude as to be unacquainted with those arts which are the first essays of human ingenuity on its advance toward improvement.Their temples, he went on to stress, could have been little more than 'a mound of earth' and their houses 'mere huts, built with turf, or mud, or the branches of trees, like those of the rudest Indians.' 'There is not', he concluded:

in all the extent of that vast empire, a single monument or vestige of any building more ancient than the conquest.Robertson based this blanket dismissal of all the innumerable detailed chronicles of the Spanish conquest - by Cortés, Pizarro, and their many contemporaries - on the account of one informant who had (allegedly) 'travelled in every part of New Spain.'

Both Stephens and Catherwood had, however, travelled widely in the Middle East as well as the Americas, and it was apparent to them that the creators of cities such as Copán, Tikal, and Chichen Itza, were in no way inferior to Ancient Greeks and Romans when it came to urban planning. They had been, in fact, in many ways more culturally advanced than their classical contemporaries.

As Stephens himself put it, in the conclusion to Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, & Yucatán, 'The monuments and pyramids of Central America and Mexico are':

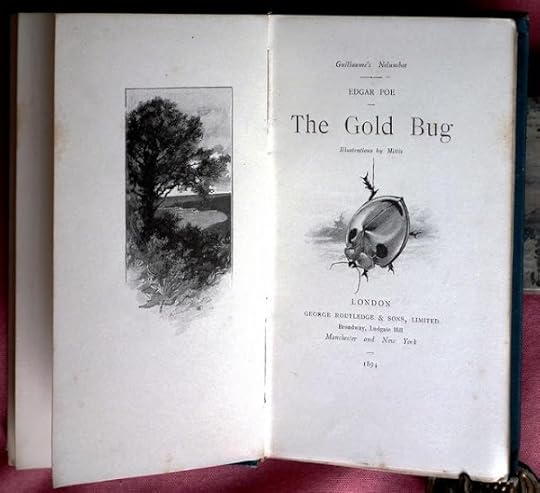

different from the works of any other known people, of a new order, and entirely and absolutely anomalous: they stand alone. ...What a resounding declaration of American intellectual independence! No wonder the book was an instant success. Even the notoriously picky Edgar Allan Poe hailed it as 'magnificent ... perhaps the most interesting book of travel ever published'.

Unless I am wrong, we have a conclusion far more interesting and wonderful than that of connecting the builders of these cities with the Egyptians or any other people. It is the spectacle of a people skilled in architecture, sculpture and drawing, and, beyond doubt, other more perishable arts, and possessing the culture and refinement attendant upon these, not derived from the Old World, but originating and growing up here, without models or masters, having a distinct, separate, independent existence; like the plants and fruits of the soil, indigenous.

•

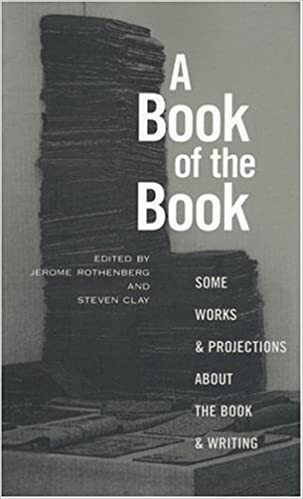

A Book of the Book (2000)

A Book of the Book (2000)Thanks to the work of contemporary scholars and translators such as Michael Coe, Sylvanus Morley, and Denis Tedlock, we can now read the creation epic of the Mayans, the Popol Vuh, in a variety of versions.

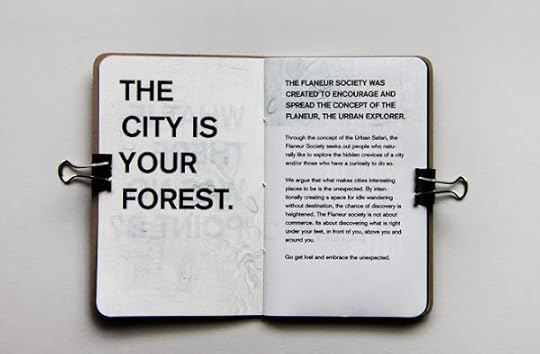

As well as the wonders of their advanced mathematical knowledge and wonderfully subtle script, Tedlock's essay 'Towards a Poetics of Polyphony and Translatability' - from the anthology pictured above, A Book of the Book: Some Works & Projections about the Book & Writing (2000) - demonstrates the complex nature of Mayan poetics, in particular the habit of Mayan writers of constantly rephrasing and paraphrasing their meanings, rather than treating poems "as if they were Scripture, composed of precisely the right words and no others':

In a poetics that always stands ready, once something has been said, to find other ways to say it, there can be no fetishization of verbatim quotation, which lies at the very heart of the Western commodification of words. In the Mayan case not even writing, whether in the Mayan script or the Roman alphabet, carries with it a need for exact quotation. When Mayan authors cite previous texts, and even when they cite earlier passages in the same text, they unfailingly construct paraphrases. [266-67]The implications of this tendency are extremely far-reaching, particularly when it comes to translation:

Translation caused anxiety long before the current critique of representations, especially the translation of poetry. Roman Jakobson pointed the way to a new construction of this problem, suggesting that the process of rewording might be called intralingual translation ...The conclusion of Tedlock's essay refuses to draw the conventional distinctions between the poetics and politics of the word, just as the Mayan poets he cites see no need to differentiate between quotation and paraphrase:

Here we have entered a realm in which the popular notion of an enmity between poetry and translation does not apply. To quote Robert Frost's famous phrasing of this notion ... 'Poetry is what gets lost in translation.' ... [Octavio] Paz countered by saying 'Poetry is what is translated.' ... To take this statement a step further and paraphrase it for the purposes of the present discussion, poetry is translation. [267-68]

we could try to see the complexity of Mayan poetry as the result of a conflict between centripetal forces in language, which are supposed to produce formal and authoritative discourse, and centrifugal forces, which are supposed to open language to its changing contexts and foment new kinds of discourse. But this is a profoundly Western way of stating the problem. Available to speakers of any language are multiple systems for phrasing utterances, including syntax, semantics, intonation, and pausing. Available to writers (even within the limits of a keyboard) is a variety of signs, of which some are highly individual and particulate while others are iconic and may stand for whole words. There is nothing intrinsic to any one of these various spoken and written codes, not even the alphabet itself, that demands the reduction of all or any of the others to its own terms. Bringing multiple codes into agreement with one another is not a matter of poetics as such, but of centralized authority [my emphasis]. It is no accident that Mayans, who never formed a conquest state and have kept their distance from European versions of the state right down to the current morning news, do not bend their poetic energies to making systems stack. [276]

•

Dennis Tedlock (1939- )

Mayan Literature in Translation

Coe, Michael D. The Maya. 1966. Eighth edition, fully revised and expanded. Ancient People and Places: Founding Editor Glyn Daniel. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd., 2011.

Coe, Michael D. Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs. 1962. Fourth edition, fully revised and expanded. 1994. Ancient People and Places: Founding Editor Glyn Daniel. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd., 1997.

Recinos, Adrián, ed. Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Ancient Quiché Maya. 1947. Trans. Delia Goetz & Sylvanus G. Morley. London: William Hodge & Company Limited, 1951.

Saravia E., Albertina, ed. Popol Wuj: Antiguas Historias de los Indios Quiches de Guatemala. Illustradas con dibujos de los Codices Mayas. 1965. “Sepan Cuantos …”, 36. Ciudad de México: Editorial Porrúa, S. A., 1986.

Sodi M., Demetrio. La literatura de los Mayas. 1964. El Legado de la América Indígena. México: Editorial Joaquín Mortiz, S. A., 1974.

Tedlock, Dennis, trans. Popol Vuh: The Definitive Edition of The Mayan Book of The Dawn of Life and The Glories of Gods and Kings. With Commentary Based on the Ancient Knowledge of the Modern Quiché Maya. 1985. Rev. ed. A Touchstone Book. New York: Simon & Schuster Inc., 1996.

Tedlock, Dennis. 2000 Years of Mayan Literature: With New Translations and Interpretations by the Author. Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2010.

Published on September 11, 2022 14:52

August 28, 2022

Sir John Lubbock's 100 Books

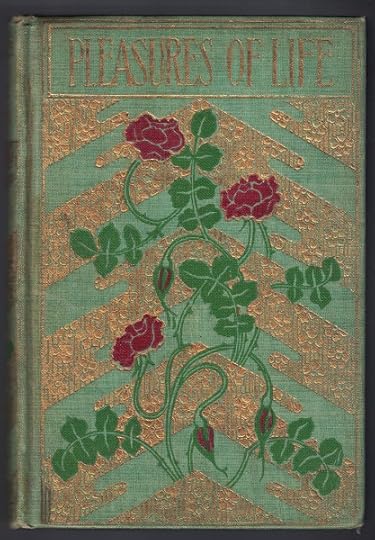

Sir John Lubbock: The Pleasures of Life (1887)

Sir John Lubbock: The Pleasures of Life (1887)One fateful evening in 1886, the Principal of the London Working-Men’s College, Sir John Lubbock, gave a speech to that institution. In it he outlined a list of 100 vital books which, if read attentively, might in themselves constitute a liberal education.

The idea took off with a vengeance, and after the list was reprinted in his essay-collection The Pleasures of Life, earnest self-improvers everywhere started to collect the various volumes.

Sir John Lubbock (1834-1913)

Sir John Lubbock (1834-1913)Lubbock himself never attended university, though he came from a privileged background, and had been educated at Eton by his wealthy family. A banker by profession, his real passions were archaeology and evolutionary biology, and he wrote extensively on both subjects.

Amongst other achievements, he was the the first to coin the terms "Neolithic" and "Palaeolithic" in one of his books about early man.

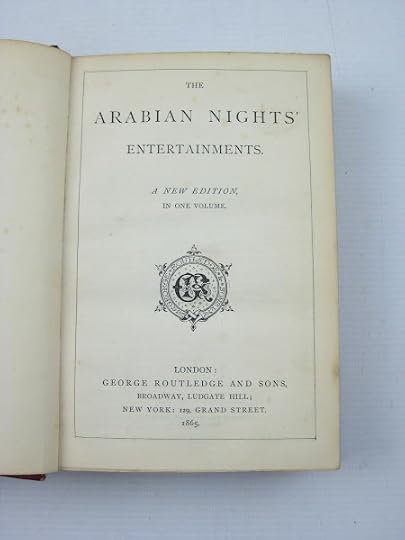

Antoine Galland: The Arabian Nights' Entertainments (London: Routledge, 1865)

Antoine Galland: The Arabian Nights' Entertainments (London: Routledge, 1865)The very first copy of the Arabian Nights I ever owned (rather similar to the one pictured above, but more battered and dogeared) proudly proclaimed itself as one of these "hundred books" - which gives some clue to the bonanza this must have constituted for enterprising publishers in the late nineteenth century.

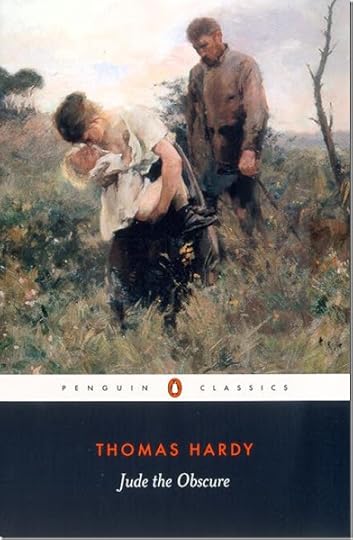

Thomas Hardy: Jude the Obscure (1894-95)

Thomas Hardy: Jude the Obscure (1894-95)It's easy to see how this idea of self-betterment through focussed reading informs Hardy's last prose masterpiece Jude the Obscure, with its almost unbearably poignant account of rural autodidact Jude's attempts to enter the sheltered cloisters of Christminster University through sheer effort and application. All in vain, of course (it is, after all, a Thomas Hardy novel).

There's a particularly poignant scene where Jude is sitting miserably by the side of the road realising the folly of his grand ambitions, and longing for someone to come by and comfort him:

But nobody did come, because nobody does: and under the crushing recognition of his gigantic error Jude continued to wish himself out of the world. - Jude the Obscure (1895)

•

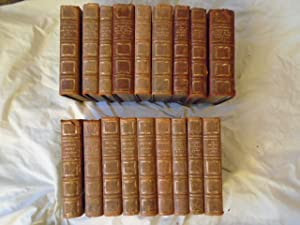

18 of the 100 Books (London: Routledge, 1890)

18 of the 100 Books (London: Routledge, 1890)[The Shi King of Confucius; The Iliad and Odyssey of Homer; Darwin's Journal of Discoveries; The Origin of Species; The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire I and II; Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations; Captain Cook's Voyages; Humboldt's Travels I-III; Scott's Ivanhoe; La Morte D'Arthur; Spinoza; The Arabian Nights' Entertainments; Bacon's Novum Organum; The Nibelungenleid; Thackeray's Pendennis]

Here, in any case, is a slightly tidied-up list of the original 100 books. It's rather hard to make the numbers fit consistently, given Lubbock's habit of listing multiple works under one author or, alternatively, listing separate works by a writer under different categories. He also published different versions of it at different times.

Each entry has been linked to a free online text wherever possible.

LIST OF 100 BOOKS

[Works by Living Authors are omitted]

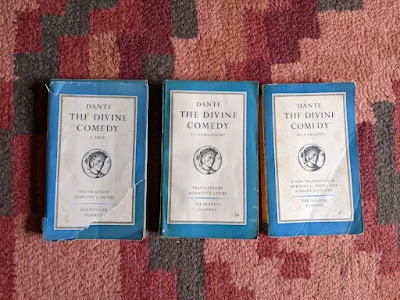

The Holy BibleThe Meditations of Marcus AureliusEpictetusAristotle’s EthicsThe Analects of ConfuciusSt Hilaire’s Le Bouddha et sa religionWake’s Apostolic FathersThomas à Kempis’ Imitation of ChristConfessions of St. AugustineThe KoranSpinoza’s Tractatus Theologico-PoliticusComte’s Catechism of Positive PhilosophyPascal’s PenséesButler’s Analogy of ReligionTaylor’s Holy Living and DyingBunyan’s Pilgrim’s ProgressKeble’s Christian YearPlato’s Apology , Phædo, & RepublicXenophon’s MemorabiliaAristotle’s PoliticsThe Public Orations of DemosthenesCicero’s Treatises on Friendship and Old Age Plutarch’s LivesBerkeley’s Human KnowledgeDescartes’ Discours sur la MéthodeLocke’s On the Conduct of the UnderstandingHomer’s Iliad & OdysseyHesiodVirgilLucretius The Mahabharata & The Ramayana [Epitomized in Talboy Wheeler’s History of India]Firdausi’s Shahnameh [Included in Persian Literature]The NibelungenliedMalory’s Morte d’ArthurThe Shi King [or Book of Songs]Kalidasa’s Sakuntala [or The Lost Ring]Aeschylus’ Tragedies and Fragments & TrilogySophocles’ OedipusEuripides’ MedeaAristophanes’ The Knights & The Clouds [In Comedies]HoraceChaucer’s Canterbury TalesShakespeareMilton’s Paradise Lost & minor poemsDante’s Divina Commedia (Cary’s translation) (Longfellow’s translation)Spenser’s Faerie QueeneDryden’s Poems [vol 1 & vol 2]Scott’s Poems [The Lady of the Lake & Marmion]Southey’s Thalaba the Destroyer & The Curse of Kehama [vol 1 & vol 2]Selected Poems of William WordsworthPope's Essay on Criticism; Essay on Man; Rape of the Lock and Other PoemsBurnsByron’s Childe HaroldGray [in The Poetical Works of Johnson, Parnell, Gray, and Smollett]Herodotus [vol 1 & vol 2]Xenophon’s AnabasisThucydidesTacitus’ GermaniaLivyGibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman EmpireHume’s History of EnglandGrote’s History of GreeceCarlyle’s French RevolutionGreen’s Short History of EnglandLewes’ History of Philosophy [vol 1 & vol 2]The Arabian NightsSwift’s Gulliver’s TravelsDefoe’s Robinson CrusoeGoldsmith’s Vicar of WakefieldCervantes’ Don QuixoteBoswell’s Life of JohnsonMolièreSchiller’s William TellSheridan’s The Critic , School for Scandal , & The Rivals Carlyle’s Past and PresentBacon’s Novum OrganumSmith’s Wealth of NationsMill’s Political EconomyCook’s VoyagesHumboldt’s Travels [vol 1, vol 2 & vol 3]White’s Natural History of SelborneDarwin's Origin of Species & Naturalist’s VoyageMill’s LogicBacon’s EssaysMontaigne’s EssaysHume’s EssaysMacaulay’s EssaysAddison’s EssaysEmerson’s EssaysBurke’s Select WorksSmiles’ Self-HelpVoltaire's Zadig & MicromegasGoethe’s Faust & AutobiographyMiss Austen’s Emma, or Pride and Prejudice Thackeray’s Vanity Fair & PendennisDickens' Pickwick, David CopperfieldLytton’s Last Days of PompeiiGeorge Eliot’s Adam BedeKingsley’s Westward Ho!Scott’s Waverley Novels

Notes:

Lubbock notes that this is “less generally suitable than most of the others in the list.” Lubbock chose later to omit this entry, commenting that English novelists were “somewhat over-represented.”

A revised version of the list was published in 1930, after Lubbock's death, with the following substituted entries:

Comte’s Catechism [no. 12] was replaced by SenecaDryden’s Poems [no. 47] was replaced by Tennyson’s Idylls of the KingHume’s Essays [no. 86] was replaced by Ruskin’s Modern Painters

•

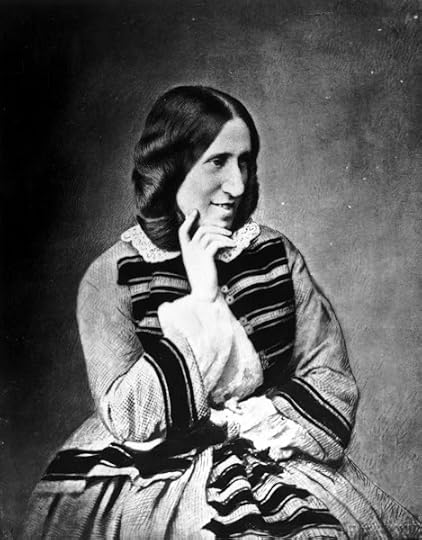

Mary Ann Evans ['George Eliot'] (1819-1880)

Mary Ann Evans ['George Eliot'] (1819-1880)Even making due allowance for the era in which it was compiled, it remains a somewhat surprising selection. There are only two female authors - both English novelists - and Lubbock eventually chose to omit Jane Austen and retain only George Eliot. Even there, it's her first novel Adam Bede, rather than the more mature Middlemarch or Daniel Deronda, which makes the cut.

There's also what would now seem a disproportionate emphasis on Christian theology, ancient and modern. I count no fewer than ten such volumes, ranging from Saint Augustine to Keble's Christian Year. By contrast, there's one book on Buddhism, another on Confucianism, one on Hinduism, and another on Islam.

There are ten British novelists there, too. But who would now think to include Edward Bulwer-Lytton and Charles Kingsley among their number? Cervantes, Goethe, and Voltaire are the only other fiction writers on the list. It's odd, moreover, to see the latter represented by Zadig and Micromegas rather than the more obvious Candide.

It's only to be expected, given Victorian ideas on education, that the Greek and Roman classics should make up a substantial part of the listings - Poets such as Homer, Hesiod, Horace, Lucretius & Virgil; Dramatists such as Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides & Aristophanes; Philosophers such as Plato, Aristotle, Epictetus & Marcus Aurelius; Historians such as Herodotus, Livy, Plutarch, Tacitus, Thucydides & Xenophon; Orators such as Demosthenes & Cicero ... In total, they make up almost a quarter of the readings.

To do him justice, Lubbock himself was the first to admit the limitations of his project:

It is one thing to own a library; it is quite another to use it wisely. I have often been astonished how little care people devote to the selection of what they read. Books, we know, are almost innumerable; our hours for reading are, alas! very few. And yet many people read almost by hazard. They will take any book they chance to find in a room at a friend's house; they will buy a novel at a railway-stall if it has an attractive title; indeed, I believe in some cases even the binding affects their choice.He goes on to specify:

The selection is, no doubt, far from easy. I have often wished some one would recommend a list of a hundred good books. If we had such lists drawn up by a few good guides they would be most useful. I have indeed sometimes heard it said that in reading every one must choose for himself, but this reminds me of the recommendation not to go into the water till you can swim.

In the absence of such lists I have picked out the books most frequently mentioned with approval by those who have referred directly or indirectly to the pleasure of reading, and have ventured to include some which, though less frequently mentioned, are especial favorites of my own. Every one who looks at the list will wish to suggest other books, as indeed I should myself, but in that case the number would soon run up.- The Pleasures of Life (1887)

I have abstained, for obvious reasons, from mentioning works by living authors, though from many of them — Tennyson, Ruskin, and others —I have myself derived the keenest enjoyment; and I have omitted works on science, with one or two exceptions, because the subject is so progressive.There's a lot more detail about his specific choices in chapter 4 of The Pleasures of Life, which makes very interesting reading. His reservations about some of the inclusions are particularly revealing. For instance:

I feel that the attempt is over bold, and I must beg for indulgence, while hoping for criticism; indeed one object which I have had in view is to stimulate others more competent far than I am to give us the advantage of their opinions.

Nor must I omit to mention Sir T. Malory's Morte d'Arthur, though I confess I do so mainly in deference to the judgment of others.Or, on the subject of which novelists to include:

Macaulay considered Marivaux's La Vie de Marianne the best novel in any language, but my number is so nearly complete that I must content myself with English: and will suggest Thackeray (Vanity Fair and Pendennis), Dickens (Pickwick and David Copperfield), G. Eliot (Adam Bede or The Mill on the Floss), Kingsley (Westward Ho!), Lytton (Last Days of Pompeii), and last, not least, those of Scott, which indeed constitute a library in themselves, but which I must ask, in return for my trouble, to be allowed, as a special favor, to count as one.

Pierre de Marivaux: La Vie de Marianne (1731-45)

Pierre de Marivaux: La Vie de Marianne (1731-45)Strangely enough, I've actually read La Vie de Marianne. It's a surprisingly entertaining novel, given that its principal subject is the endless rehearsal of the sufferings and woes of the title character - whom I'd always assumed to have been suggested by Samuel Richardson's Pamela in his 1640 novel of that name. Now, however, I see that the dates don't fit, and that if there was influence, it must have been in the opposite direction.

I'm not sure that I'd put it in any lists of must-reads, mind you, but then that just illustrates the invidiousness of such choices. The moment you start to legislate about such things, you end up putting in bizarre tomes such as Samuel Smiles' Self-Help rather than, say, Marx's Das Kapital.

Would it do a modern reader any harm to sit down and start reading their way through Sir John Lubbock's hundred books? No, I don't think so. At the very least it would give you quite a good idea of the classical idea of the canon - as it stood in the late nineteenth century.

I'm not sure that it would do you all that much good, though. You'd have to substitute more reliable texts on the world's great religions, more up-to-date histories than Carlyle's or Grote's, and a greatly increased number of books on economics and science. In fact, you might end up with something like this:

•

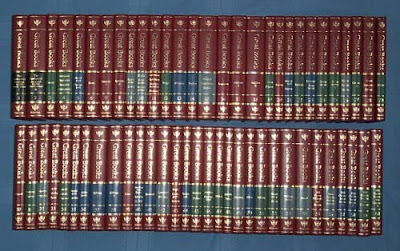

Britannica: Great Books of the Western World (1990)

Britannica: Great Books of the Western World (1990)The Britannica Great Books of the Western World series was first published, as a set of 54 volumes, in 1952:

The original editors had three criteria for including a book in the series drawn from Western Civilization: the book must have been relevant to contemporary matters, and not only important in its historical context; it must be rewarding to re-read repeatedly with respect to liberal education; and it must be a part of "the great conversation about the great ideas", relevant to at least 25 of the 102 "Great Ideas" as identified by the editor of the series's comprehensive index, ... dubbed the "Syntopicon".- WikipediaA second edition, enlarged to 60 volumes, was published in 1990. Among other revisions, "Four women authors were included, where previously there were none."

You can look at the original lists in the Wikipedia article above. I suspect that most of us probably have a few odd volumes of the series kicking around. The double-columns of print and large format make them difficult to read, but they are a useful source for otherwise difficult to locate texts. I see that I myself own ten of them - marked below in bold - though I've never consciously collected them: The Great ConversationSyntopicon ISyntopicon IIVolume 4: Homer (rendered into English prose by Samuel Butler)The IliadThe Odyssey

Homer. The Iliad & The Odyssey. Trans. Samuel Butler. 1898. Great Books of the Western World, 4. Ed. Robert Maynard Hutchins. 1952. Chicago: William Benton, Publisher / Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1989.Aeschylus / Sophocles / Euripides / AristophanesHerodotus / ThucydidesPlatoVolume 8: Aristotle ICategoriesOn InterpretationPrior AnalyticsPosterior AnalyticsTopicsSophistical RefutationsPhysicsOn the HeavensOn Generation and CorruptionMeteorologyMetaphysicsOn the SoulMinor biological works

Aristotle. The Works, Volume 1. Ed. W. D. Ross. Great Books of the Western World, 8. Ed. Robert Maynard Hutchins. Chicago: William Benton, Publisher / Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., 1952.Volume 9: Aristotle IIHistory of AnimalsParts of AnimalsOn the Motion of AnimalsOn the Gait of AnimalsOn the Generation of AnimalsNicomachean EthicsPoliticsThe Athenian ConstitutionRhetoricPoetics

Aristotle. The Works, Volume 2. Ed. W. D. Ross. Great Books of the Western World, 9. Ed. Robert Maynard Hutchins. Chicago: William Benton, Publisher / Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., 1952.Hippocrates / GalenVolume 11:EuclidThe Thirteen Books of Euclid's Elements ArchimedesOn the Sphere and CylinderMeasurement of a CircleOn Conoids and SpheroidsOn SpiralsOn the Equilibrium of PlanesThe Sand ReckonerThe Quadrature of the ParabolaOn Floating BodiesBook of LemmasThe Method Treating of Mechanical Problems Apollonius of PergaOn Conic Sections Nicomachus of GerasaIntroduction to Arithmetic

Euclid. The Thirteen Books of the Elements / Archimedes. The Works, Including the Method / Apollonius of Perga. On Conic Sections / Nichomachus of Gerga. Introduction to Arithmetic. Trans. Thomas L. Heath, R. Catesby Taliaferro, & Martin L. D’Ooge. 1926 & 1939. Great Books of the Western World, 11. Ed. Robert Maynard Hutchins. Chicago: William Benton, Publisher / Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., 1952.Lucretius / Epictetus / Marcus AureliusVirgilVolume 14: PlutarchThe Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans (translated by John Dryden)

Plutarch. The Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans (The Dryden Translation). Great Books of the Western World, 14. Ed. Robert Maynard Hutchins. Chicago: William Benton, Publisher / Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., 1952.TacitusVolume 16:PtolemyAlmagest, (translated by R. Catesby Taliaferro) Nicolaus CopernicusOn the Revolutions of Heavenly Spheres (translated by Charles Glenn Wallis) Johannes Kepler (translated by Charles Glenn Wallis)Epitome of Copernican Astronomy (Books IV–V)The Harmonies of the World (Book V)

Ptolemy. The Almagest / Copernicus. On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres / Kepler. Epitome of Copernican Astronomy: IV & V; The Harmonies of the World: V. Trans. R. Catesby Taliaferro, & Charles Glenn Wallis. Great Books of the Western World, 16. Ed. Robert Maynard Hutchins. Chicago: William Benton, Publisher / Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., 1952.PlotinusSt. AugustineVolume 19: Thomas AquinasSumma Theologica (First part complete, selections from second part, translated by the Fathers of the English Dominican Province and revised by Daniel J. Sullivan)

Aquinas, Thomas. The Summa Theologica, 1. Trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province. 1941. Rev. Daniel J. Sullivan. Great Books of the Western World, 19. Ed. Robert Maynard Hutchins. Chicago: William Benton, Publisher / Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., 1952.Volume 20: Thomas AquinasSumma Theologica (Selections from second and third parts and supplement, translated by the Fathers of the English Dominican Province and revised by Daniel J. Sullivan)

Aquinas, Thomas. The Summa Theologica, 2. Trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province. 1941. Rev. Daniel J. Sullivan. Great Books of the Western World, 20. Ed. Robert Maynard Hutchins. Chicago: William Benton, Publisher / Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., 1952.DanteChaucerMachiavelli / HobbesRabelaisMontaigneShakespeare IShakespeare IIGilbert / Galileo / HarveyCervantes: Don QuixoteSir Francis BaconDescartes / SpinozaMiltonPascalNewton / HuygensLocke/ Berkeley / HumeSwift: Gulliver's Travels / Sterne: Tristram ShandyFielding: Tom JonesMontesquieu / RousseauAdam SmithGibbon: The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire IGibbon: The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire IIKantAmerican State Papers / Hamilton, Madison, Jay: The Federalist / John Stuart MillBoswell: Life of JohnsonLavoisier / Fourier / FaradayHegelGoethe: FaustMelville: Moby DickDarwinKarl Marx / Friedrich EngelsTolstoy: War and PeaceDostoevsky: The Brothers KaramazovVolume 53: William JamesThe Principles of Psychology

James, William. The Principles of Psychology. Great Books of the Western World, 53. Ed. Robert Maynard Hutchins. Chicago: William Benton, Publisher / Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., 1952.Volume 54: Sigmund FreudThe Origin and Development of Psycho-AnalysisSelected Papers on HysteriaThe Sexual Enlightenment of ChildrenThe Future Prospects of Psycho-Analytic TherapyObservations on "Wild" Psycho-AnalysisThe Interpretation of DreamsOn NarcissismInstincts and Their VicissitudesRepressionThe UnconsciousA General Introduction to Psycho-AnalysisBeyond the Pleasure PrincipleGroup Psychology and the Analysis of the EgoThe Ego and the IdInhibitions, Symptoms, and AnxietyThoughts for the Times on War and DeathCivilization and Its DiscontentsNew Introductory Lectures on Psycho-Analysis

Freud, Sigmund. The Major Works. Great Books of the Western World, 54. Ed. Robert Maynard Hutchins. Chicago: William Benton, Publisher / Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., 1952.

•

Again it seems, in retrospect, 70 years on, quite an odd list. It's very anglocentric, for a start: Boswell's Life of Johnson, a whole slew of novels and other literary works easily available elsewhere ... but it does represent a certain advance on Lubbock, insofar (at least) that it admits upfront its 'Western' orientation - if you'll forgive the pun.

The editors were well aware of this, however, so when they revised it in 1990, they added six new volumes of more contemporary material: one on Philosophy, one on Science, one on Economics, one on Anthropology, and two on Modernist Literature (you can see further details here).

Like all such grand intellectual enterprises, however, it looks now more like an index of the blind-spots in the late twentieth-century mind than a truly satisfactory summary of the best of Western thought.

•

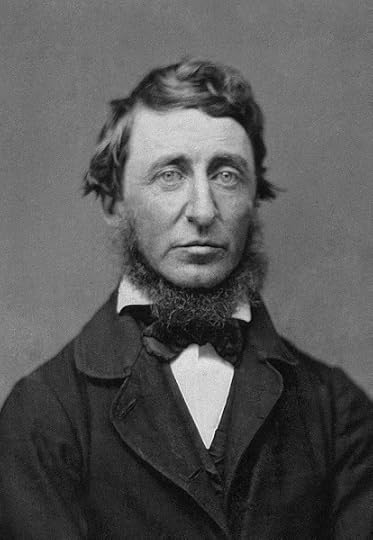

Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862)

Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862)So what's my conclusion? "Beware of all enterprises that require new clothes," as Henry Thoreau put it so succinctly (or, as in this case, new book-bindings). But he went on to say: "and not rather a new wearer of clothes" - which is perhaps the nub of the matter.

No set list of readings will produce an original, free-thinking intellect, whether it be Sir John Lubbocks's 100 books, the Britannica Great Books, the Harvard Classics, or The Sacred Books of the East. That's not to say that such collections of books have no abiding usefulness, however - it's probably better to take them as a series of local guides than as a grand, overarching index to the nature of the universe, however.

And, in the meantime, it can be useful - and salutary - to skim through such lists and remind yourself of just how far you've fallen short of the minimum knowledge expected of either a nineteenth-century or a more contemporary 'common reader'!

•

David Morrell & Hank Wagner: Thrillers: 100 Must-Reads (2010)

David Morrell & Hank Wagner: Thrillers: 100 Must-Reads (2010)

Published on August 28, 2022 16:21

August 22, 2022

Sandmania

The Sandman (Netflix, 2022- )

The Sandman (Netflix, 2022- )It's actually quite hard for me to remember a time before I knew Sandman. The graphic novel, that is, not the TV series. That's pretty new to all of us, I suppose.

Neil Gaiman: World's End (1994)

Neil Gaiman: World's End (1994)And yet, I do dimly recall getting out a single volume of The Sandman Library out from the Auckland Central Library. Sometime in the late 1990s, it must have been. The book in question was No. 8: World’s End, which was, in retrospect, not a bad introduction to strange and intricate world of Neil Gaiman's comic.

Neil Gaiman: World's End (1994)

Neil Gaiman: World's End (1994)After that I read odd volumes as they came to hand - mostly completely out of sequence, unfortunately - until I had more or less grasped the whole thing. At which point I realised that I really had to own it all myself, and started buying the ones available in Borders, then online, until I had a complete set and could read the whole work from start to finish.

According to Wikipedia, The original series ran for 75 separate issues, each with a cover by , from January 1989 to March 1996. When collected subsequently for book publication, it was divided into the following volumes:

Preludes and Nocturnes, illustrated by Sam Kieth, Mike Dringenberg & Malcolm Jones III, coloured by Robbie Busch, and lettered by Todd Klein, collects The Sandman #1–8 (1988–1989)The Doll's House, illustrated by Mike Dringenberg, Malcolm Jones III, Chris Bachalo, Michael Zulli & Steve Parkhouse, coloured by Robbie Busch, and lettered by Todd Klein, collects The Sandman #9–16 (1989–1990)Dream Country, illustrated by Kelley Jones, Charles Vess, Colleen Doran & Malcolm Jones III, coloured by Robbie Busch & Steve Oliff, and lettered by Todd Klein, collects The Sandman #17–20 (1990)Season of Mists, illustrated by Kelley Jones, Mike Dringenberg, Malcolm Jones III, Matt Wagner, Dick Giordano, George Pratt & P. Craig Russell, coloured by Steve Oliff & Daniel Vozzo, and lettered by Todd Klein, collects The Sandman #21–28 (1990–1991)A Game of You, illustrated by Shawn McManus, Colleen Doran, Bryan Talbot, George Pratt, Stan Woch & Dick Giordano, coloured by Daniel Vozzo, and lettered by Todd Klein collects The Sandman #32–37, 1991–1992)Fables and Reflections, illustrated by Bryan Talbot, Stan Woch, P. Craig Russell, Shawn McManus, John Watkiss, Jill Thompson, Duncan Eagleson, Kent Williams, Mark Buckingham, Vince Locke & Dick Giordano, coloured by Daniel Vozzo & Lovern Kindzierski/Digital Chameleon, and lettered by Todd Klein, collects The Sandman #29–31, 38–40, 50; The Sandman Special #1; and Vertigo Preview No. 1 (1991–1993)Brief Lives, illustrated by Vince Locke, Dick Giordano & Jill Thompson, coloured by Daniel Vozzo, and lettered by Todd Klein, collects The Sandman #41–49 (1992–1993)Worlds' End, illustrated by Michael Allred, Gary Amaro, Mark Buckingham, Dick Giordano, Tony Harris, Steve Leialoha, Vince Locke, Shea Anton Pensa, Alec Stevens, Bryan Talbot, John Watkiss & Michael Zulli, coloured by Danny Vozzo, and lettered by Todd Klein, collects The Sandman #51–56 (1993)The Kindly Ones, illustrated by Marc Hempel, Richard Case, D'Israeli, Teddy Kristiansen, Glyn Dillon, Charles Vess, Dean Ormston & Kevin Nowlan, coloured by Daniel Vozzo, and lettered by Todd Klein, collects The Sandman #57–69 and Vertigo Jam No. 1 (1993–1995)The Wake, illustrated by Michael Zulli, Jon J. Muth & Charles Vess, coloured by Daniel Vozzo & Jon J. Muth, and lettered by Todd Klein, collects The Sandman #70–75 (1995–1996)If you're suprised to see quite so much detail here about who illustrated, coloured, and lettered each issue, it's important to emphasise that the creation of American mass-market comics depends on taking a team approach. There's no other way to guarantee enough product on the newstands every month.

Simply put, the writer supplies a blow-by-blow account of what they have in mind (there are sample scripts in some of the Sandman reprints, if you're curious to see what these look like). The penciller does a rough sketch of each panel and page. The inker then draws in a final version of these images (with revisions, if necessary). The colours are then added by a further artist, after which the dialogue and captions are lettered into each speech balloon and inset panel.

This sounds like - and, I gather, is - quite a laborious process. Individual comics auteurs tend to take care of most or all of these levels of production all by themselves. But that's one reason why lone wolf comics take such an inordinate amount of time to create.

The work involved is staggering, and when one adds the information - supplied by Gaiman himself - that each page of his comics requires about four pages of description, the true scale of such enterprises as The Sandman begins to come into focus: 3,000-odd pages of comic = roughly 12,000 pages of writing.

What, then, of the TV series, revealed to us finally after 30 years in development limbo? Well, fans will immediately note some changes and elisions: John Constantine has been replaced by his ancestor Lady Johanna Constantine, and a number of characters (including Death) have changed their ethnicity. All in all, though, such shifts are less notable than the number of things which have remained intact.

And one can already detect, at the end of the first series (roughly covering the first two volumes of the comic) the plotlines lining up for more momentous developments in Morpheus's journey. Overall, I'd say I liked it a lot. It's rather schmaltzy at times, but then so is the comic. It's also gruesome - which I liked less - but then that's true to the spirit of the original, too.

One thing I particularly appreciated was how slow-moving most of the episodes were. There was none of that break-neck, frenetic pace which such shows as Dr Who have increasingly adopted as their trademark technique for engaging with 'youth'. Morpheus, by contrast, speaks slowly and deliberately and has long, detailed conversations with his collaborators (and victims) before making each of his moves on the celestial chessboard.

It was, in other words, written for people with a brain - whether they happened to be young or old - rather than the guppy attention-spanned audiences generally courted by streaming providers. The special effects are rich and (for the most part) well realised, and the episodes nicely balanced between atmosphere and action.

If the overall intention was to hook us on yet another epic fantasy serial like Game of Thrones, with its year-long waits between series, I'm afraid that they've been only too successful. I, for one, will be waiting impatiently to see where they go next with it. Bronwyn is so anxious to know what happens next that she may have to resort to reading the comics!

•

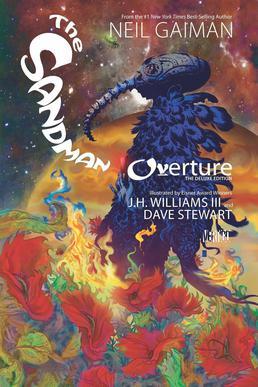

Neil Gaiman et al. The Sandman: Overture (2013)

Neil Gaiman et al. The Sandman: Overture (2013)There's a large number of spin-offs, sequels and part-sequels to The Sandman, some written by Gaiman himself and some by other people. Few of them could be said to be really essential reading, but there are some exceptions.

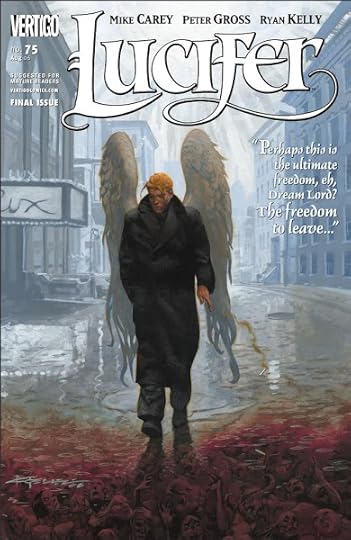

The most extended example, Mike Carey's Lucifer - which I suspect will survive its dreadful TV adaptation (even worse than the one of Gaiman's novel American Gods, which is saying something) - is, imho, a bona fide masterpiece which challenges comparison even with its original:

Mike Carey: Lucifer (1999-2007)

Mike Carey: Lucifer (1999-2007)Lucifer 1: Devil in the Gateway. The Sandman Presents – Lucifer 1-3: 1999 & Lucifer 1-4: 2000. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2001. Lucifer 2: Children and Monsters. Lucifer 5-13: 2000. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2001.Lucifer 3: A Dalliance with the Damned. Lucifer 14-20: 2001. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2002.Lucifer 4: The Divine Comedy. Lucifer 21-28: 2002. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2003.Lucifer 5: Inferno. Lucifer 29-35: 2003. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2004.Lucifer 6: Mansions of the Silence. Lucifer 36-41: 2003. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2004.Lucifer 7: Exodus. Lucifer 42-44, 46-49: 2004. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2005.Lucifer 8: The Wolf beneath the Tree. Lucifer 45, 50-54: 2004. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2005.Lucifer 9: Crux. Lucifer 55-61: 2005. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2006.Lucifer 10: Morningstar. Lucifer 62-69: 2006. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2006.Lucifer 11: Evensong. Lucifer – Nirvana: 2002 & Lucifer 70-75: 2006. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2007.

Some of the others, such as the 2013 "Overture" to The Sandman are also worth a look. I've provided a partial list below, but for more information, you could do worse than look here.

There's even, now, an annotated edition compiled by the indefatigable Leslie S. Klinger.

Leslie S. Klinger: The Annotated Sandman (2012-15)

Leslie S. Klinger: The Annotated Sandman (2012-15)•

Neil Gaiman (2013)

Neil Gaiman (2013)Neil Richard MacKinnon Gaiman

(1960- )

Comics:

[with Dave McKean] Violent Cases (1987)[with Dave McKean] Black Orchid (1988–1989 / 1991)Sandman (1989-1996)The Sandman Library I: Preludes & Nocturnes. 1991. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 1995.The Sandman Library II: The Doll’s House. 1990. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 1995.The Sandman Library III: Dream Country. 1991. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 1995.The Sandman Library IV: Season of Mists. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 1992.The Sandman Library V: A Game of You. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 1993.The Sandman Library VI: Fables & Reflections. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 1993.The Sandman Library VII: Brief Lives. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 1994.The Sandman Library VIII: World’s End. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 1994.The Sandman Library IX: The Kindly Ones. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 1996.The Sandman Library X: The Wake. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 1997.[with Yoshitaka Amano] The Sandman: The Dream Hunters. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 1999.The Sandman: Endless Nights. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2003.The Sandman: Overture. 2013-15. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2016.The Books of Magic (1990-1991)The Books of Magic. 1990-91; 1993. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2001.Death (1993-1996)Death: The High Cost of Living. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 1994.Death: The Time of Your Life. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 1997.The Last Temptation (1994-1995)[with Alice Cooper] The Last Temptation. Illustrated by Michael Zulli. 1994-95. Oregon: Dark Horse Comics, 2000.[with Dave McKean] The Tragical Comedy or Comical Tragedy of Mr. Punch (1994-1995)Neil Gaiman's Midnight Days (1999)Midnight Days. 1989-95. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 1999.Marvel 1602 (2003-2004)Marvel 1602. Illustrated by Andy Kubert. 2003-4. New York: Marvel Worldwide Inc., 2013.A Study in Emerald (2018)A Study in Emerald. Illustrated by Rafael Albuquerque. Milwaukie, Oregon: Dark Horse Books, 2018.

Novels:

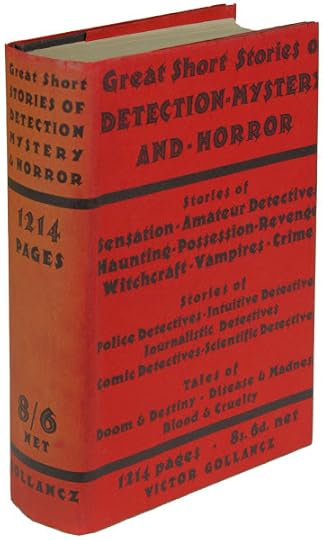

[with Terry Pratchett] Good Omens (1990)Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch. A Novel. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1990.Neverwhere (1996)Neverwhere. 1996. New York: HarperTorch, 2001.Neverwhere: Author's Preferred Text, with How the Marquis Got His Coat Back. 1996 & 2014. William Morrow. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2016.Stardust (1999)Stardust. London: Headline Book Publishing, 1999.American Gods (2001)American Gods. London: Headline Book Publishing, 2001.American Gods: The Author's Preferred Text. 2001 & 2004. Review. London: Headline Book Publishing, 2005.Anansi Boys (2005)Anansi Boys. London: Headline Book Publishing, 2005.[with Michael Reaves] InterWorld. InterWorld Series 1 (2007)The Graveyard Book (2008)The Graveyard Book. Illustrated by Chris Riddell. 2008. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2009.[with Michael Reaves & Mallory Reaves] The Silver Dream. InterWorld Series 2 (2013)The Ocean at the End of the Lane (2013)The Ocean at the End of the Lane. London: Headline Publishing Group, 2013.[with Michael Reaves & Mallory Reaves] Eternity's Wheel. InterWorld Series 2 (2015)

Picture Books:

The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish. Illustrated by Dave McKean (1997)[with Gene Wolfe] A Walking Tour of the Shambles. Illustrated by Randy Broecker (2002)Coraline. Illustrated by Dave McKean (2002) Coraline. Illustrations by Dave McKean. 2002. New York: Harper Trophy, 2003.The Wolves in the Walls. Illustrated by Dave McKean (2003)Melinda. Illustrated by Dagmara Matuszak (2005)MirrorMask. Illustrated by Dave McKean (2005)Mirrormask. Illustrated by Dave McKean. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2005.Odd and the Frost Giants. Illustrated by Brett Helquist (2008)The Dangerous Alphabet. Illustrated by Gris Grimly (2008)Blueberry Girl. Illustrated by Charles Vess (2009)Crazy Hair. Illustrated by Dave McKean (2009)Instructions. Illustrated by Charles Vess (2010)Chu's Day. Illustrated by Adam Rex (2013)Fortunately, the Milk. Illustrated by Skottie Young, US / Chris Riddell, UK / Boulet, France (2013)Chu's First Day of School. Illustrated by Adam Rex (2014)Hansel and Gretel. Illustrated by Lorenzo Mattotti (2014)The Sleeper and the Spindle. Illustrated by Chris Riddell (2014)Chu's Day at the Beach. Illustrated by Adam Rex (2016)Cinnamon. Illustrated by Divya Srinivasan (2017)Pirate Stew. Illustrated by Chris Riddell (2020)

Short Fiction:

Angels and Visitations (1993)Smoke and Mirrors (1998)Smoke and Mirrors: Short Fictions and Illusions. London: Headline Book Publishing, 1999.Smoke and Mirrors: Short Fiction and Illusions. 1999. Headline Feature. London: Headline Book Publishing, 2000.Fragile Things (2006)Fragile Things: Short Fictions and Wonders. 2006. London: Headline Publishing Group, 2013.M is for Magic (2007)Who Killed Amanda Palmer (2009)A Little Gold Book of Ghastly Stuff (2011)Trigger Warning (2015)Trigger Warning: Short Fictions and Disturbances. London: Headline Publishing Group, 2015.The Neil Gaiman Reader (2020)The Neil Gaiman Reader: Selected Fiction. Foreword by Marlon James. London: Headline Publishing Group, 2020.

Non-fiction:

Duran Duran: The First Four Years of the Fab Five (1984)[with Kim Newman] Ghastly Beyond Belief (1985)Ghastly Beyond Belief. Ed. Neil Gaiman & Kim Newman. Introduction by Harry Harrison. London: Arrow Books, 1985.Don't Panic: A Biography of Douglas Adams (1988)Adventures in the Dream Trade (2002)Make Good Art: A Commencement Speech Given at the UArts on 17 May 2012 (2013)The View from the Cheap Seats (2016)The View from the Cheap Seats: Selected Non-fiction. London: Headline Publishing Group, 2016.Norse Mythology (2017)Norse Mythology. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2017.

Screenplays:

[with storyboards by Dave McKean] MirrorMask: The Illustrated Film Script (2005)[with Roger Avary] Beowulf: The Script Book (2007)

Secondary:

Bender, Hy. The Sandman Companion. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 1999.

Hy Bender: The Sandman Companion (1999)

Hy Bender: The Sandman Companion (1999)

Published on August 22, 2022 14:47

August 13, 2022

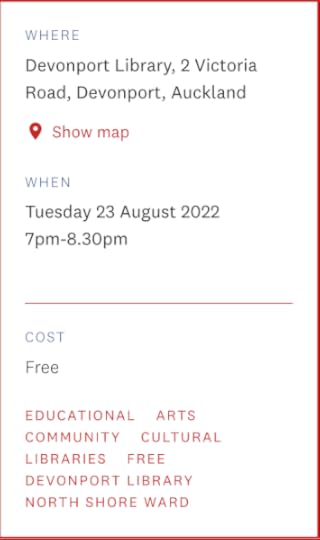

Devonport Library Poetry Reading - Tuesday 23/8/22

Te Pātaka Kōrero o Te Hau Kapua / Devonport Library

Te Pātaka Kōrero o Te Hau Kapua / Devonport LibraryWaxing Lyrical

The Devonport Library Associates present Jack Ross with Johanna Emeney, Elizabeth Morton, Lisa Samuels and Bryan Walpert, all eminent poets reading from their own works.

Jack is a recent editor of Poetry New Zealand.

This event is part of Auckland Libraries’ We Read Auckland | Ka Pānui Tātau I Tāmaki Makaurau.

The idea of this reading, which coincides with the beginning of the Auckland Writers Festival, is to celebrate the reopening of the Devonport Library's event series - after a couple of years of pandemic-prompted closures - with a showcase of local, North Shore-based poets.

Each writer will have the chance to read a representative sample from their work. Their latest books will also be on sale, thanks to our friends at Paradox Books.

The real heroes of the occasion are, however, the Devonport Library Associates: chair Jan Mason, events organiser Paul Beachman, and publicity courtesy of Linda Hopkins.

•

Johanna Emeney

Johanna Emeney

Johanna Emeney lives with her husband David and a family of cats, goats, sheep and ponies. Jo’s latest book, co-written with Sarah Laing, launches on September 7th, 6pm at Takapuna Library. Sylvia and the Birds is part-biography of Bird Lady Sylvia Durrant and part call-to-arms for young environmental activists.

Johanna Emeney: Felt (2021)

Johanna Emeney: Felt (2021)•

Elizabeth Morton

Elizabeth Morton

Elizabeth Morton is an Auckland writer, with three collections of poetry, the latest being Naming the Beasts (Otago University Press). She holds an MLitt from the University of Glasgow, and is completing an MSc at Kings College London. Her writing has appeared in publications from New Zealand, the UK, the USA, Canada, Ireland, Australia and online.

Elizabeth Morton: Naming the Beasts (2022)

Elizabeth Morton: Naming the Beasts (2022)•

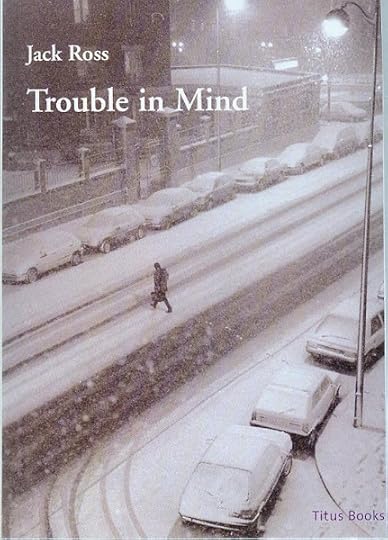

Jack Ross

Jack Ross

Jack Ross is the author of six poetry collections, most recently The Oceanic Feeling (2021), as well as numerous works of fiction, including The Annotated Tree Worship, highly commended in the 2018 NZSA Heritage Book Awards. He was managing editor of Poetry New Zealand from 2014-2020, and has edited many other books, anthologies, and literary journals. He lives in Mairangi Bay and blogs at The Imaginary Museum.

Jack Ross: The Oceanic Feeling (2021)

Jack Ross: The Oceanic Feeling (2021)•

Lisa Samuels

Lisa Samuels

Lisa Samuels is Professor of English at the University of Auckland and the author of eighteen books, mostly poetry, and of many influential essays on theories of interpretation and body ethics. Lisa also works with sound, visual art, film, and editing, including co-editing the anthology A Transpacific Poetics (Litmus Press 2017). Her most recent poetry book is Breach (Boiler House Press 2021), and a Serbian translation of her novel Tender Girl has just been published by Partizanska Press.

Lisa Samuels: Breach (2021)

Lisa Samuels: Breach (2021)•