Jack Ross's Blog, page 11

January 5, 2022

SF Luminaries: Walter M. Miller, Jr.

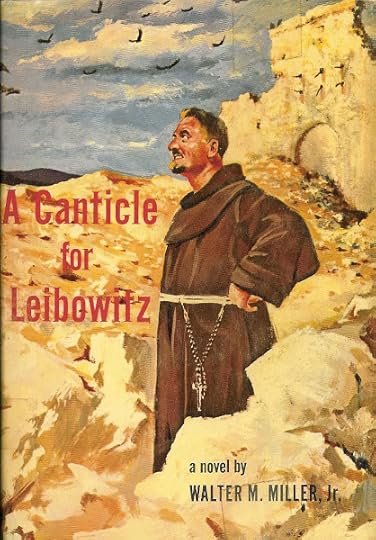

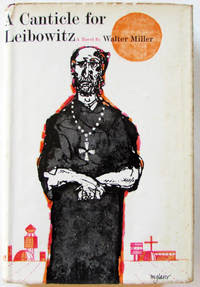

Walter M. Miller, Jr.: A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959)

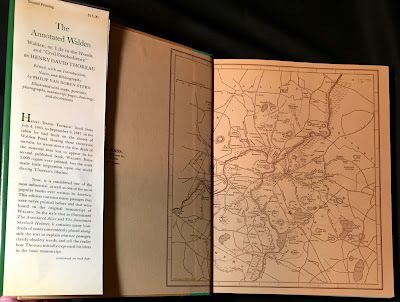

Walter M. Miller, Jr.: A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959)Ever since I first picked up a scruffy secondhand paperback copy in a local bookshop, I've been entranced by A Canticle for Leibowitz. As you can see from the montage below, there's been no shortage of editions and reprints of this 'famous and prophetic best seller of the new dark age of man". What of its author, though? Who was this strange man Walter M. Miller, Jr.?

Walter M. Miller, Jr.: Leibowitz covers

Walter M. Miller, Jr.: Leibowitz coversWell, as W. H. Auden states so succinctly in his sonnet Who's Who: "A shilling life will give you all the facts" - or, as in this case, a brief consultation of the relevant wikipedia entry:

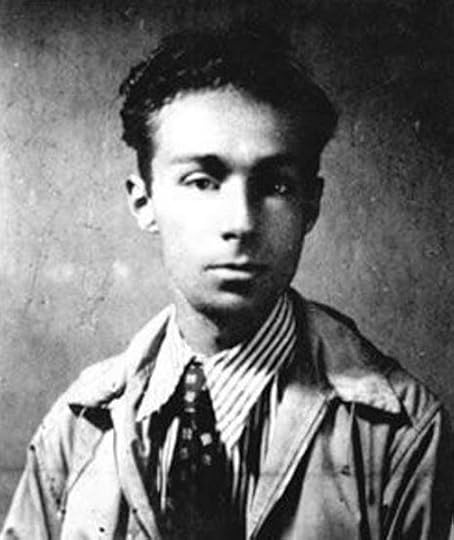

Miller was born on January 23, 1923, in New Smyrna Beach, Florida. Educated at the University of Tennessee and the University of Texas, he worked as an engineer. During World War II, he served in the Army Air Forces as a radioman and tail gunner, flying more than fifty bombing missions over Italy. He took part in the bombing of the Benedictine Abbey at Monte Cassino, which proved a traumatic experience for him. Joe Haldeman reported that Miller "had post-traumatic stress disorder for 30 years before it had a name"

Joe Haldeman: The Forever War (1974)

Joe Haldeman: The Forever War (1974)Joe Haldeman is, of course, the author of the classic Vietnam-cum-SF novel The Forever War, still in print after almost fifty years.

After the war, Miller converted to Catholicism ... Between 1951 and 1957, [he] published over three dozen science fiction short stories, winning a Hugo Award in 1955 for the story "The Darfsteller".

Late in the 1950s, Miller assembled a novel from three closely related novellas he had published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction in 1955, 1956 and 1957. The novel, entitled A Canticle for Leibowitz, was published in 1959. It is a post-apocalyptic novel revolving around the canonisation of Saint Leibowitz, and is considered a masterpiece of the genre. It won the 1961 Hugo Award for Best Novel.

After the success of A Canticle for Leibowitz, Miller ceased publishing, although several compilations of Miller's earlier stories were issued in the 1960s and 1970s.

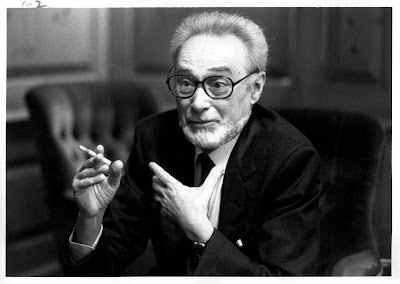

In Miller's later years, he became a recluse, avoiding contact with nearly everyone, including family members; he never allowed his literary agent, Don Congdon, to meet him. According to science fiction writer Terry Bisson, Miller struggled with depression, but had managed to nearly complete a 600-page manuscript for the sequel to Canticle before taking his own life with a firearm on January 9, 1996, shortly after his wife's death.

The sequel, Saint Leibowitz and the Wild Horse Woman, was completed by Bisson at Miller's request and published in 1997.

Walter M. Miller, Jr.: Saint Leibowitz and the Wild Horse Woman (1997)

Walter M. Miller, Jr.: Saint Leibowitz and the Wild Horse Woman (1997)I wish I could say that this last, posthumous work of fiction was a triumphant vindication of his decades in the wilderness. Alas, it is not. Various of the commentators on his Goodreads page do their best to defend it:

[Dropping Out]: Miller's "problem" was that he hit a grand-slam home-run in Canticle, and he spent the remainder of what must have been a sad and frustrating life trying to get out from under Canticle's shadow. ...Others seem more inclined to tell it like it is:

[Jason]: Saint Leibowitz reminded me very much of Herbert's Dune. They are both sprawling novels dealing with the political machinations of both Church and State, and they both center on the manipulations of the mysterious, isolated, less-civilized nomadic peoples whose loyalties will tip the balance of power.

[Doreen]: Oddly enough, I seem to be one of the few people here who enjoyed the sequel much more than its predecessor. I found A Canticle... devoid of much of the human suffering that pervades this book, which questions the conflict between faith and tradition, desire and happiness, and what it means to be a good human being.

[Bryn Hammond]: There’s almost no science fiction left. It was much more like reading a (burlesque) historical fiction on the medieval church, muddled up with the American West. Canticle’s concerns with science aren’t pursued, and the post-nuclear-war setting becomes accidental.Perhaps the best overall summary comes from Zoe's Human:

[Jon]: The sequel to A Canticle for Leibowitz was thirty years in the making, but unfortunately, Miller seems to have forgotten how to write a novel in those decades. Many of the moral and ethical arguments that made Canticle so brilliant are still present, as is the occasional bit of dry humor, but these are overshadowed by long and drawn-out passages, poor plotting, and a conclusion that seems to have been hastily written the night before the book went to press (the "Wild Horse Woman" from the title, for example, virtually never appears in the novel; I'm still confused as to why her name appears so prominently on the book's spine)

Life is too short for books you don't enjoy.

Maybe the fault is mine for trying to read this right after A Canticle for Leibowitz which would be a tough act to follow for anyone (including, apparently, the author who wrote it). Perhaps my expectations were just too high. This started off well enough with a nice premise about loss of faith, but it kind of fizzled after the first two or three chapters.

Or perhaps the fact that the author was suicidally depressed and took his own life before he finished it was a factor. Another author finished it from a reportedly almost complete manuscript, but how complete was it really? And how much did the original author's struggle with mental illness factor in?

The Year's Best Science Fiction Novels (1953)

The Year's Best Science Fiction Novels (1953)One of Miller's rarer stories, not included in any of the various collections of his short fiction, is "Izzard and the Membrane." An extra level of confusion is added by the fact that the book above, which I inherited from my father's science fiction collection, is the 1953 UK edition of a book which originally appeared in the USA in 1952. Despite its publication date, then, it actually constitutes The Year's Best Science Fiction Novels 1952, not 1953:

The Year's Best Science Fiction Novels (1952)

The Year's Best Science Fiction Novels (1952)The American edition also included an extra story, Arthur C. Clarke's "Seeker of the Sphinx", presumably omitted from the British reprint for copyright reasons.

The reason this bibliographical minutiae seems worth stressing is because "Izzard and the Membrane" is quite a remarkable story, every bit the equal of most of the novellas included in his officially sanctioned collections. Its cold war stereotypes may seem a little dated now, but Miller's astonishing intuitions about the possibilities of computer artificial intelligence and the creation of alternate realities are worthy of the creators of Westworld or the Metaverse itself.

So good is it, in fact, that it makes one feel rather curious about some of the other stories I've tried to list below as comprehensively as possible. By my count he wrote 43 stories in all (at least two of which were not SF). Of these 41, a mere fourteen were collected in his final selection The Best of Walter M. Miller, Jr. (1980) - subsequently reprinted under other titles, but without any expansion of the contents.

That leaves at least 26 other stories to read (not counting the two romance stories and a co-authored crime story) from that incredibly productive period of writing between 1951 and 1957. There may well be some duds among them, but it seems hard to believe that only "Izzard" is worthy of resurrection among such a number of pieces published - for the most part - in the top SF journals of the day.

That's the new Walter M. Miller book I'm holding out for: not the last, incomplete, rather depressing Saint Leibowitz. After all, his short stories and short novels were always his strongest work. From the much-anthologised "Crucifixus Etiam," with its unforgettable image of the purgatorial plains of Mars, to ,"Big Joe and the Nth Generation" (aka "It Takes a Thief"), he showed a flair for memorable characterisation and arresting plotlines second to none - not even such celebrated contemporaries as Philip K. Dick and Robert A. Heinlein.

James Blish: A Case of Conscience (1958)

James Blish: A Case of Conscience (1958)That's not to say that there was anything unprecedented about Miller's trajectory from slam-bang Sci-fi to the subtleties of religious dogma in the apocalypse-haunted 1950s. It wasn't just mainstream fiction which became obsessed with the ethical dilemmas associated with (mainly Catholic) Christianity. Authors such as Graham Greene, François Mauriac and Evelyn Waugh dominated the bestseller lists, and it seemed for a while there as if the twin blows of Hiroshima and Auschwitz had discredited scientific reductionism for good.

James Blish's A Case of Conscience is a good example - within the genre-boundaries of SF - of this type of writing. It could then be taken for granted that monastic orders would accompany any future space-faring expeditions, and that the local religious concerns of this world were bound to find echoes out in the great beyond.

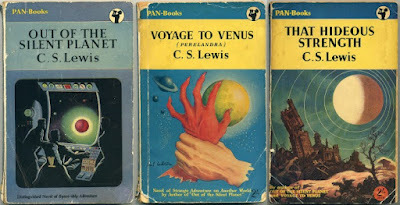

C. S. Lewis: The Cosmic Trilogy (1938-45)

C. S. Lewis: The Cosmic Trilogy (1938-45)C. S. Lewis's interplanetary trilogy undoubtedly helped to demonstrate the viability of such themes in a genre still dominated by the rationalist assumptions of Jules Verne and H. G. Wells. Ray Bradbury got in on the act, too, in his story "The Fire Balloons" [aka "In This Sign ..."] included in some editions of his classic Martian Chronicles.

C. S. Lewis: Out of the Silent Planet / Perelandra / That Hideous Strength (1938, 1943, 1945)

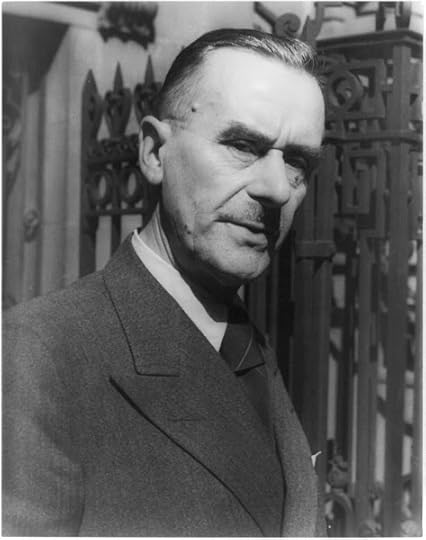

C. S. Lewis: Out of the Silent Planet / Perelandra / That Hideous Strength (1938, 1943, 1945)In a way, though, despite his obvious affinity with other such earnest Catholic strivers in the 1950s, the philosophical scope of Miller's Canticle seems to me to have more in common with Hermann Hesse's Glass Bead Game (1943) than with the likes of Blish, Bradbury or Lewis.

Ray Bradbury: The Fire Balloons (1951)

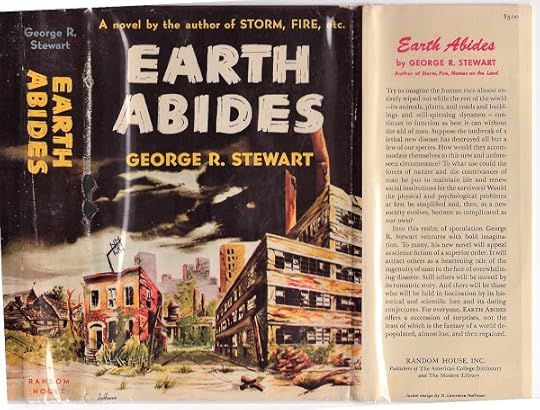

Ray Bradbury: The Fire Balloons (1951)Its popularity then and since has certainly depended to some extent on its links with other SF apocalypses of the 1950s: George Stewart's Earth Abides (1949), or Philip K. Dick's zany Dr Bloodmoney, or How We Got Along After the Bomb (1965). A Canticle for Leibowitz continues to evade us, though. It has elements of all of these things - Catholic apologia, SF Apocalypse, Dystopian satire - and yet it can't be said to be subsumed entirely by any of them.

George R. Stewart: Earth Abides (1949)

George R. Stewart: Earth Abides (1949)I do hope one day to be able to purchase at least some of the uncollected stories of Walter M. Miller in convenient book form, but there's still a strong case for believing that everything significant he had to say was contained in this one, stand-alone masterpiece. His mistake, then - if mistake it was - lay in thinking he could emulate or even surpass it in his final few years.

Walter M. Miller, Jr.: A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959)

Walter M. Miller, Jr.: A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959)•

Walter M. Miller, Jr. (1923-1996)

Walter Michael Miller, Jr.

(1923-1996)

Novels:

A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959) Fiat Homo [aka 'A Canticle for Leibowitz'] (1955) Fiat Lux [aka 'And the Light is Risen'] (1956) Fiat Voluntas Tua [aka 'The Last Canticle'] (1957) A Canticle for Leibowitz: A Novel. 1959. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1960.A Canticle for Leibowitz. 1959. Corgi Science-Fiction. London: Transworld Publishers Ltd., 1970. [with Terry Bisson] Saint Leibowitz and the Wild Horse Woman (1997)Saint Leibowitz and the Wild Horse Woman. Ed. Terry Bisson. 1997. An Orbit Book. London: Little, Brown and Company (UK), 1998.

Collections:

The Year’s Best Science Fiction Novels. Ed. Everett F. Bleiler & T. E. Dikty. London: Grayson & Grayson, 1953.Izzard and the Membrane, by Walter M. Miller, Jr.… And Then There Were None, by Eric Frank RussellFlight to Forever, by Poul AndersonThe Hunting Season, by Frank M. Robinson Conditionally Human (1962)Conditionally Human (1952)The Darfsteller (1955)Dark Benediction (1951) The View from the Stars (1965)Blood Bank (1952)Dumb Waiter (1952)Anybody Else Like Me? (1952)The Big Hunger (1952)The Will (1954)Crucifixus Etiam (1953)I, Dreamer (1953)Big Joe and the Nth Generation (1952)You Triflin' Skunk! (1955) The Science Fiction Stories of Walter M. Miller Jr. (1977)Conditionally Human (1952)Blood Bank (1952)Dark Benediction (1951)Dumb Waiter (1952)Anybody Else Like Me? (1952)The Big Hunger (1952)The Darfsteller (1955)The Will (1954)Crucifixus Etiam (1953)I, Dreamer (1953)Big Joe and the Nth Generation (1952)You Triflin' Skunk! (1955) Conditionally Human and Other Stories. 1980. Corgi Science-Fiction. London: Transworld Publishers Ltd., 1982.Conditionally Human (1952)Blood Bank (1952)Dark Benediction (1951)Dumb Waiter (1952)Anybody Else Like Me? (1952)The Big Hunger (1952) The Darfsteller and Other Stories. 1980. Corgi Science-Fiction. London: Transworld Publishers Ltd., 1982.The Darfsteller (1955)The Will (1954)Vengeance for Nikolai (1957)Crucifixus Etiam (1953)I, Dreamer (1953)The Lineman (1957)Big Joe and the Nth Generation (1952)You Triflin' Skunk! (1955) Dark Benediction. [aka 'The Best of Walter M. Miller, Jr.', 1980]. SF Masterworks. Gollancz. London: Orion Publishing Group, 2007.Conditionally Human (1952)Blood Bank (1952)Dark Benediction (1951)Dumb Waiter (1952)Anybody Else Like Me? (1952)The Big Hunger (1952)The Darfsteller (1955)The Will (1954)Vengeance for Nikolai (1957)Crucifixus Etiam (1953)I, Dreamer (1953)The Lineman (1957)Big Joe and the Nth Generation (1952)You Triflin' Skunk! (1955) Two Worlds of Walter M. Miller (2010)The Hoofer (1955)Death of a Spaceman (1954)

Chapbooks:

The Hoofer [1955] (2009)Death of a Spaceman [1954] (2009)Way of a Rebel [1954] (2010)Check and Checkmate [1953] (2010)The Ties That Bind [1954] (2010)Conditionally Human [1952] (2016)It Takes a Thief [1952] (2019)

Short Stories & Novellas:

[Included in The Year’s Best Science Fiction Novels (1952);

A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959);

Conditionally Human (1962);

The View from the Stars (1965);

The Best of Walter M. Miller, Jr. (1980);

Two Worlds of Walter M. Miller (2010)]

MacDoughal's Wife [not SF] (1950)Month of Mary [not SF] (1950)Secret of the Death Dome [novella] (1951)Izzard and the Membrane [novella] (1951)The Soul-Empty Ones [novella] (1951) Dark Benediction [novella] (1951)The Space Witch [novella] (1951)The Song of Vorhu ... for Trumpet and Kettledrum [novella] (1951)The Little Creeps [novella] (1951)The Reluctant Traitor [novella] (1952) Conditionally Human [novella] (1952)Bitter Victory (1952) Dumb Waiter [novella] (1952) Big Joe and the Nth Generation {aka "It Takes a Thief"} (1952) Blood Bank [novella] (1952)Six and Ten Are Johnny [novella] (1952)Let My People Go [novella] (1952)Cold Awakening [novella] (1952)Please Me Plus Three [novella] (1952)No Moon for Me (1952) The Big Hunger (1952)Gravesong (1952) Anybody Else Like Me? {aka "Command Performance"} [novella] (1952)A Family Matter (1952)Check and Checkmate [novella] (1953) Crucifixus Etiam {aka "The Sower Does Not Reap"} (1953) I, Dreamer (1953)The Yokel [novella] (1953)Wolf Pack (1953) The Will (1954) Death of a Spaceman {aka "Memento Homo"} (1954)I Made You (1954)Way of a Rebel (1954)The Ties that Bind [novella] (1954) The Darfsteller [novella] (1955) You Triflin' Skunk! {aka "The Triflin' Man"} (1955)A Canticle for Leibowitz {aka "The First Canticle"} [novella] (1955) The Hoofer (1955)And the Light is Risen [novella] (1956)The Last Canticle [novella] (1957)Vengeance for Nikolai {aka "The Song of Marya"} (1957)[with Lincoln Boone] The Corpse in Your Bed is Me (1957)The Lineman [novella] (1957)

Secondary:

David N. Samuelson, "The Lost Canticles of Walter M. Miller, Jr." Science Fiction Studies #8 (Vol 3, part 1) (March 1976) - "Appendix: The Books and Stories of Walter M. Miller, Jr.":"Secret of the Death Dome," novelette, Amazing (January, 1951; reprinted in Amazing (June, 1966)."Izzard and the Membrane," novelette, Astounding (May, 1951); anthologized in Everett Bleiler and T.E. Dikty, eds., Year’s Best Science Fiction Novels: 1952 (New York: Frederick Fell, 1952)."The Soul-Empty Ones," novelette, Astounding (August, 1951)."Dark Benediction," short novel, Fantastic Adventures (September, 1951); collected in Conditionally Human (1962)."The Space Witch," novelette, Amazing (November, 1951); reprinted in Amazing (October, 1966)."The Song of Vorhu ... for Trumpet and Kettledrum," novelette, Thrilling Wonder Stories (December, 1951)."The Little Creeps," novelette, Amazing (December, 1951); reprinted in Fantastic (May, 1968); anthologized in Milton Lesser, ed., Looking Forward (New York: Beechhurst, 1953)."The Reluctant Traitor," short novel, Amazing (January, 1952)."Conditionally Human," novelette, Galaxy (February, 1952); revised and collected in Conditionally Human (1962); anthologized in Everett Bleiler and T.E. Dikty, eds., Year’s Best Science Fiction Novels: 1953 (New York: Frederick Fell, 1953)."Bitter Victory," short story, IF (March, 1952)."Dumb Waiter," novelette, Astounding (April, 1952); collected in The View from the Stars (1965); anthologized in Groff Conklin, ed., Science Fiction Thinking Machines (New York: Vanguard, 1954) and Damon Knight, Cities of Wonder (Garden City: Doubleday, 1966)."It Takes a Thief," short story, IF (May, 1952); collected, as "Big Joe and the Nth Generation," in The View from the Stars (1965)."Blood Bank," novelette, Astounding (June, 1952); collected in The View from the Stars (1965); anthologized in Martin Greenberg, ed., All About the Future (New York: Gnome Press, 1953)."Six and Ten are Johnny," novelette, Fantastic (Summer, 1952); reprinted in Fantastic (January, 1966)."Let My People Go," short novel, IF (July, 1952)."Cold Awakening," novelette, Astounding (August, 1952)."Please Me Plus Three," novelette, Other Worlds (August, 1952)."No Moon for Me," short story, Astounding (September, 1952); anthologized in William Sloane, ed., Space, Space, Space (New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1953)."The Big Hunger," short story, Astounding (October, 1952); collected in The View from the Stars (1965); anthologized in Donald A Wollheim, ed., Prize Science Fiction (New York: McBride, 1953)."Gravesong," short story, Startling (October, 1952)."Command Performance," novelette, Galaxy (November, 1952); collected, as "Anybody Else Like Me?" in The View from the Stars (1965); anthologized in Everett Bleiler and T.E. Dikty, eds., The Best Science Fiction Stories: 1953 (New York: Frederick Fell, 1953); Horace Gold, ed., The Second Galaxy Reader (New York: Crown, 1954); and Brian W. Aldiss, ed., Penguin Science Fiction (London: Penguin, 1961)."A Family Matter," short story, Fantastic Story Magazine (November, 1952)."Check and Checkmate," novelette, IF (January, 1953)."Crucifixus Etiam," short story, Astounding (February, 1953); collected in The View from the Stars (1965); anthologized in Everett Bleiler and T.E. Dikty, eds., The Best Science Fiction Stories: 1954 (New York: Frederick Fell, 1954); Judith Merril, ed., Human? (New York: Lion, 1954); Michael Sissons, ed., Asleep in Armageddon (London: Panther, 1962); Kingsley Amis and Robert Conquest, eds., Spectrum V (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1966); and Robert Silverberg, ed., Tomorrow’s Worlds (New York: Meredith, 1969)."I, Dreamer," short story, Amazing (July, 1953); collected in The View from the Stars (1965)."The Yokel," novelette, Amazing (September, 1953)."The Wolf Pack," short story, Fantastic (Oct., 1953); reprinted in Fantastic (May, 1966); anthologized in Judith Merril, ed., Beyond the Barriers of Space and Time (New York: Random House, 1954)."The Will," short story, Fantastic (February, 1954); reprinted in Fantastic (April, 1969); collected in The View from the Stars (1965); anthologized in T.E. Dikty, ed., The Best Science Fiction Stories and Novels: 1955 (New York: Frederick Fell, 1955)."Death of a Spaceman," short story, Amazing (March, 1954); reprinted in Amazing (March, 1969); anthologized in William F. Nolan, ed., A Wilderness of Stars (Los Angeles: Sherbourne Press, 1971); anthologized as "Memento Homo" in T.E. Dikty, ed., The Best Science Fiction Stories and Novels: 1955 (New York: Frederick Fell, 1955); Robert P. Mills, ed., The Worlds of Science Fiction (New York: Dial Press, 1963); and Laurence M. Janifer, ed., Masters’ Choice (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1966)."I Made You," short story, Astounding (March, 1954)."Way of a Rebel," short story, IF (April, 1954)."The Ties that Bind," novelette, IF (May, 1954); anthologized in William F. Nolan, ed., A Sea of Space (New York: Bantam, 1970)."The Darfsteller," short novel, Astounding (January, 1955); collected in Conditionally Human (1962); anthologized in Isaac Asimov, ed., The Hugo Winners (Garden City: Doubleday, 1962)."The Triflin’ Man," short story, Fantastic Universe (January, 1955); collected as "You Triflin’ Skunk" in The View from the Stars (1965); anthologized in Judith Merril, ed., Galaxy of Ghouls (New York: Lion, 1955)."A Canticle for Leibowitz," short novel, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (F & SF) (April, 1955); revised as part of A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959); anthologized in T.E. Dikty, ed., Best Science Fiction Stories and Novels: 1956 (New York: Frederick Fell, 1956); Anthony Boucher, ed., The Best from Fantasy and Science Fiction, fifth series (Garden City: Doubleday, 1956); and Christopher Cerf, ed., The Vintage Anthology of Science Fantasy (New York: Vintage, 1966)."The Hoofer," short story, Fantastic Universe (September, 1955); anthologized in Judith Merril, ed., S_F: The Year’s Greatest Science-Fiction and Fantasy (New York: Dell, 1956), and S-F: The Best of the Best (New York: Dell, 1968)."And the Light is Risen," short novel, F & SF (August, 1956); revised as part of A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959)."The Last Canticle," short novel, F & SF (February, 1957); revised as part of A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959)."Vengeance for Nikolai," short story, Venture (March, 1957); anthologized in Joseph Ferman, ed., No Limits (New York: Ballantine, 1958)."The Corpse in Your Bed is Me," short story co-authored by Lincoln Boone, Venture (May, 1957)."The Lineman," short novel, F & SF (August, 1957); anthologized in William F. Nolan, ed., A Wilderness of Stars (Los Angeles: Sherbourne Press, 1971).

Walter M. Miller, Jr.: A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959)

•

Published on January 05, 2022 12:33

December 22, 2021

Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio

Herbert A. Giles, trans. Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio (1880)

Herbert A. Giles, trans. Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio (1880)I remember, back in the 1980s, trotting off one day to my regular haunt the Edinburgh Filmhouse to see a film called A Chinese Ghost Story.

Siu-Tung Ching, dir.: A Chinese Ghost Story (1987)

Siu-Tung Ching, dir.: A Chinese Ghost Story (1987)It wasn't the only Chinese film I saw at that time. They seemed to be distinguished mainly by irrepressible energy and humour. I saw Peking Opera Blues (1986), with its cross-dressing heroine and its gender-fluid cast of 1920s 'decadents' (I remember one scene where they expressed their disdain for convention by pouring champagne all over the record player blasting out jazz to shield their revels!). I found out later that it's one of Quentin Tarantino's favourite films.

Clarence Fok & Yuen Biao, dir.: The Iceman Cometh (1989)

Clarence Fok & Yuen Biao, dir.: The Iceman Cometh (1989)I also remember seeing a Hong Kong movie called The Iceman Cometh (1989), which had some very amusing scenes where an ultra-modern young lady puts an ancient frozen warrior in his proper place of obedience to her every whim.

I wouldn't say A Chinese Ghost Story displayed much more authenticity than the other two mentioned above, but it was certainly their equal in entertainment value. I did vaguely notice that the screenplay was based on a genuine ghost story, but at the time I knew little of Pu Songling or his celebrated 18th-century compilation of such stories, translated as Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio by sinologist Herbert Giles in the late nineteenth century.

John Minford, trans. Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio (2006)

John Minford, trans. Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio (2006)In fact, it wasn't until I bought a copy of John Minford's new version of selected stories from Pu Songling's collection that I began to realised just what a treasure I'd missed! Minford is perhaps best known for his completion of the Penguin Classics translation of Cao Xueqin's great novel The Story of the Stone, begun by his former teacher (and father-in-law) David Hawkes.

John Minford, trans. The Story of the Stone (1982)

John Minford, trans. The Story of the Stone (1982)Cao Xueqin. The Story of the Stone (Also Known as The Dream of the Red Chamber): A Chinese Novel by Cao Xueqin in Five Volumes, edited by Gao E. Vol. 4: The Debt of Tears. Trans. John Minford. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1982.The intention behind Minford's Penguin Classics version of Pu Songling's Strange Tales is to restore its original frankness and variety, a feature obscured by the "limitations of the taste of [Giles's] time, which dictated what he thought he could permissibly do":

Cao Xueqin. The Story of the Stone (Also Known as The Dream of the Red Chamber): A Chinese Novel by Cao Xueqin in Five Volumes, edited by Gao E. Vol. 5: The Dreamer Wakes. Trans. John Minford. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1986.

I had originally determined to publish a full and complete translation of the whole ... but on a closer acquaintance many of the stories turned out to be quite unsuitable for the age in which we live, forcibly recalling the coarseness of our own writers of fiction in the eighteenth century. [Giles, quoted by Minford, p.xxxii]Minford, by contrast, is fascinated by the "intensity and richness" of the collection:

In fact, so great an emphasis does Minford place on this aspect of Pu's compilation, that it can come as a bit of a relief to turn to the staider pages of Giles's own selection.

Strange Tales is (among other things) a casebook of Chinese sexual pathology ... A young man with a roving eye is deluded by his neighbour's pretty wife into having sex with a rotten log and as a result has his penis fatally bitten by a scorpion ... A kungfu master bashes his penis with a mallet and feels no pain. We encounter aphrodisiacs, love potions and dildos ... Above all, again and again, we read of the seduction of an enervated young scholar by some fatally attractive woman-as-fox or woman-as-ghost, their sexual liaison leading to his eventual debilitation and premature death. [xxi]

Yuan Mei: Censored by Confucius (1788)

Yuan Mei: Censored by Confucius (1788)Towards the end of the eighteenth century, famed Chinese poet Yuan Mei published his own collection of ghost stories and strange happenings. His original title for the book was "Censored by Confucius" (though he subsequently changed it to "New Wonder Tales" when he discovered that name had already been used by a 14th-century Yuan dynasty writer). The reference is to a passage in the Analects, where it is said of Confucius:

The Master never talked of wonders, feats of strength, disorders of nature, or spirits. [Arthur Waley's translation]

Arthur Waley: Yuan Mei (1956)

Arthur Waley: Yuan Mei (1956)The implication is, of course, that anecdotes about such subjects are irrelevant and even harmful to the well-ordered Confucian individual. Yuan Mei, by contrast, an addict of such "perverse, depraved, obscene and licentious ideas," as his contemporary Zhang Xuechen described them, felt thoroughly at home in such regions. As he remarks in one of his "Seven Poems on Aging":

Talk of books - why they please or fail to please -And certainly the above selection from Yuan Mei's collection, published in English in 1996, contains the same basic medley of fox-spirits, ghosts, and other Fortean phenomena as Pu Songling's. It does appear (to me, at least) to lack some of the latter's complexity and charm, however, though that could easily be a result of the choice of stories. Yuan Mei was, after all, one of the greatest poets and writers of his age, and there were 747 stories in the original collection, of which only 100 have been presented here.

Or of ghosts and marvels, no matter how far-fetched,

These are excesses in which, should he feel inclined,

A man of seventy-odd may well indulge. [quoted in Louie & Edwards, p. xxiv]

Lafcadio Hearn: Some Chinese Ghosts (1886)

Lafcadio Hearn: Some Chinese Ghosts (1886)Finally, last but not least, I'd like to say a few words about the collection above, one of many adaptation / translations put together by Irish-Greek-American writer Lafcadio Hearn. Hearn is, of course, far more famous for the numerous works he published about his adopted country, Japan.

This early book, written while he was still living in New Orleans, was largely cribbed from the publications of French travellers, though it's possible that it may have been influenced some of Giles's Strange Tales as well. Certainly it seems more redolent of fin-de-siècle Chinoiserie than what we might regard as more authentic folklore.

Hearn was, after all, a decadent, and if it were not for the continued vogue that his books still have among contemporary Japanese readers, he'd probably be largely forgotten now. In any case, if - like me - you're fascinated by tales of "ghosts and marvels, no matter how far-fetched", I thoroughly recommend these three collections of Chinese ghost stories.

There can be a certain monotony in any ghost story tradition, whether it features Ouija boards and clanking chains or - as in this case - fox-spirits and earth-bound ghosts. The solution seems to be to mix it up. And certainly, when A Chinese Ghost Story opened an unexpected door into strangeness for me all those years ago, I had no idea where it might end up.

Jack Ross: Ghost Stories (2019)

Jack Ross: Ghost Stories (2019)•

Pu Songling

Pu SonglingPu Songling

(1640-1715)

Translations:

Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio. Trans. Herbert A. Giles. London: T. De La Rue, 1880.Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio. Trans. Herbert A. Giles. 1880. Rev. ed. 1916. Honolulu, Hawai’i: University Press of the Pacific, 2003. Strange Stories from the Lodge of Leisure. Trans. George Soulie. London: Constable, 1913.Strange Tales of Liaozhai. Trans. Lu Yunzhong, Chen Tifang, Yang Liyi, & Yang Zhihong. Hong Kong: Commercial Press, 1982.Strange Tales of Liaozhai. Trans. Lu Yunzhong, Yang Liyi, Yang Zhihong, & Chen Tifang. Illustrated by Tao Xuehua. Hong Kong: The Commercial Press, Ltd., 1982. Strange Tales from Make-do Studio. Trans. Denis C. & Victor H. Mair. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1989.Strange Tales from Make-Do Studio. Trans. Denis C. & Victor H. Mair. 1989. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1996. Strange Tales from the Liaozhai Studio. Trans. Zhang Qingnian, Zhang Ciyun and Yang Yi. Beijing: People's China Publishing, 1997.Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio. Trans. John Minford. London: Penguin, 2006.Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio. Trans. John Minford. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2006. Strange Tales from Liaozhai. Trans. Sidney L. Sondergard. 6 vols. Jain Pub Co., 2008-2017.

Secondary:

Judith T. Zeitlin. Historian of the Strange: Pu Songling and the Chinese Classical Tale. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1993.

•

Luo Ping: Yuan Mei

Luo Ping: Yuan MeiYuan Mei

(1716–1797)

Translations:

Censored by Confucius: Ghost Stories. 1788. Ed. & trans. Kam Louie & Louise Edwards. New Studies in Asian Culture. An East Gate Book. New York & London: M. E. Sharpe, 1996.

Secondary:

Arthur Waley. Yuan Mei: Eighteenth Century Chinese Poet. London: George Allen and Unwin, 1956.

•

Frederick Gutekunst: Lafcadio Hearn (1889)

Frederick Gutekunst: Lafcadio Hearn (1889)Patrick Lafcadio Hearn(1850-1904)

America & the West Indies:

La Cuisine Creole: A Collection of Culinary Recipes (1885)"Gombo Zhèbes": A Little Dictionary of Creole Proverbs, Selected from Six Creole Dialects (1885)Chita: A Memory of Last Island (1889)Youma, the Story of a West-Indian Slave (1889)Two Years in the French West Indies (1890)

Japan:

Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan (1894)Out of the East: Reveries and Studies in New Japan (1895)Kokoro: Hints and Echoes of Japanese Inner Life. 1896. Tokyo & Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1977.Gleanings in Buddha-Fields: Studies of Hand and Soul in the Far East (1897)The Boy who Drew Cats (1897)Exotics and Retrospectives (1898)Japanese Fairy Tales (1898)In Ghostly Japan. 1899. Tokyo & Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1972.Shadowings (1900)Japanese Lyrics (1900)A Japanese Miscellany (1901)Kottō: Being Japanese Curios, with Sundry Cobwebs (1902)Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things. 1904. The Travellers’ Library. London: Jonathan Cape, 1927.Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation (1904)The Romance of the Milky Way and other studies and stories (1905)

Posthumous:

Letters from the Raven; being the correspondence of Lafcadio Hearn with Henry Watkin et al. (1907)Leaves from the Diary of an Impressionist (1911)Interpretations of Literature (1915)Karma (1918)On Reading in Relation to Literature (1921)Creole Sketches (1924)Lectures on Shakespeare (1928)Insect-musicians and other stories and sketches (1929)Japan's Religions: Shinto and Buddhism (1966)Books and Habits; from the Lectures of Lafcadio Hearn (1968)Writings from Japan: An Anthology. Ed. Francis King. Penguin Travel Library. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1984.Lafcadio Hearn's America: Ethnographic Sketches and Editorials (2002)Lafcadio Hearn's Japan: An Anthology of His Writings on the Country and Its People (2007)American Writings (Library of America, 2009): Some Chinese Ghosts | Chita | Two Years in the French West Indies | Youma | selected journalism and lettersInsect Literature (2015)Japanese Ghost Stories. Ed. Paul Murray (2019)Japanese Tales of Lafcadio Hearn. Ed. Andrei Codrescu (2019)

Translations &c.:

One of Cleopatra's Nights and Other Fantastic Romances, by Théophile Gautier (1882)Stray Leaves From Strange Literature; Stories Reconstructed from the Anvari-Soheili, Baital Pachisi, Mahabharata, Pantchantra, Gulistan, Talmud, Kalewala, etc. (1884)Chinese Ghost Stories: Curious Tales of the Supernatural. ['Some Chinese Ghosts', 1886]. Tuttle Publishing. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd., 2011.Tales from Théophile Gautier (1888) The Crime of Sylvestre Bonnard, by Anatole France (1890)The Temptation of Saint Anthony, by Gustave Flaubert (1910)Stories from Emile Zola (1935)The Tales of Guy de Maupassant (1964)

Secondary:

Elizabeth Bisland. The Life and Letters of Lafcadio Hearn. 2 vols. New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Company, 1906.Jonathan Cott. Wandering Ghost: The Odyssey of Lafcadio Hearn. New York: Knopf, 1990.Carl Dawson. Lafcadio Hearn and the Vision of Japan. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.Paul Murray. A Fantastic Journey: The Life and Literature of Lafcadio Hearn. Tokyo: Japan Library, 1993.

•

The Golden Casket: Chinese Novellas of Two Millennia (1965)

The Golden Casket: Chinese Novellas of Two Millennia (1965)Anthologies

Bauer, Wolfgang & Herbert Fiske, eds. The Golden Casket: Chinese Novellas of Two Millennia. 1959. Trans. Christopher Levenson. 1964. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1967.

Lin Yutang. Famous Chinese Short Stories. 1952. Montreal: Pocket Books of Canada, 1953.

Ma, Y. W. & Joseph M. Lau, eds. Traditional Chinese Stories: Themes and Variations. New York: Columbia University Press, 1978.

•

Published on December 22, 2021 12:05

December 11, 2021

SF Luminaries: Frank Herbert

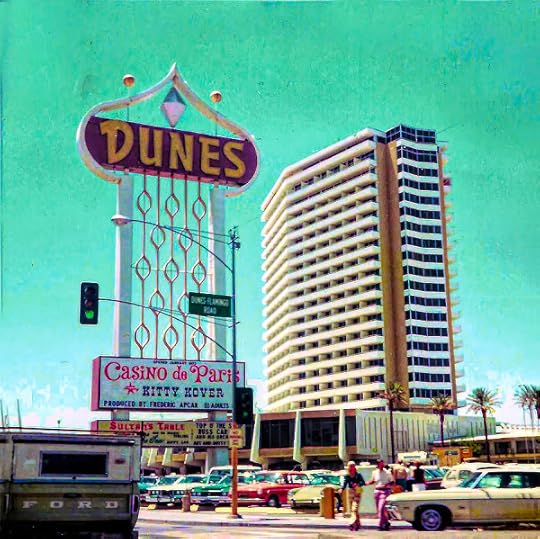

Denis Villeneuve, dir.: Dune: Part One (2021)

Denis Villeneuve, dir.: Dune: Part One (2021)Dunes

"These memories, which are my life"

- Evelyn Waugh, Brideshead Revisited (1945)

I see that my old paperback copy of Dune is dated 1973. I think that I must have got it for my birthday in 1975, when I was just turning 13. It didn't disappoint. In fact, I think that next to The Lord of the Rings, it probably had the biggest influence on me of anything I'd read up to then.

Frank Herbert: Dune (1965)

Frank Herbert: Dune (1965)Not that I found it flawless, even at the time. I found the italicised internal monologues by the main characters unnecessarily intrusive on the action, and I also found tedious the 'sayings' by each of these characters enshrined in quote marks at the opening of each chapter.

But, hey, those were small things beside the sheer fascination of Herbert's vision of planetary ecologies, his portrayal of the Fremen, and the tantalising glimpses he provided of an immensely complex galaxy-wide economy.

Frank Herbert: Dune Messiah (1969)

Frank Herbert: Dune Messiah (1969)Dune Messiah was an unexpectedly depressing cold shower-bath of a sequel to the lush vistas of Dune - though it's definitely grown on me over the years - but Frank Herbert seemed to be back on planet-spanning form in its follow-up, Children of Dune.

Frank Herbert: Children of Dune (1976)

Frank Herbert: Children of Dune (1976)I dutifully followed the saga through all its twists and turns in the next three sequels, until the ridiculously titled (though actually rather good) Chapter House Dune in 1985. Herbert died the year after it was published.

•

David Lynch, dir.: Dune (1984)

David Lynch, dir.: Dune (1984)By then, however, we'd entered the world of the movies. There were many rumours about the first Dune film before it came out. I think Sci-fi fans in general were most excited by the prospect of a Ridley Scott version, building on the artistry of his Alien and (in particular) Blade Runner triumphs.

Dune, dir. & writ. David Lynch (based on the novel by Frank Herbert) - with Francesca Annis, Linda Hunt, Kyle MacLachlan, Everett McGill, Kenneth McMillan, Siân Phillips, Jürgen Prochnow, Patrick Stewart, Sting, Max von Sydow, Sean Young - (USA, 1984).

I don't think anyone - or anyone in my circle, at any rate - knew about the Jodorowsky concept designs, or any of the other details of the rocky road that led to David Lynch's eventual De Laurentis-produced spectacular.

I wouldn't say that it was love at first sight. The movie was too campy and over-the-top for an SF-cinematic sensibility formed by Kubrick's 2001 and Scott's Blade Runner. Over time, however, I began to see that Lynch was a horse of a different colour. He saw Dune as a huge Italian melodrama, with a lush operatic score, and a massive cast of picturesque characters.

Francesca Annis as Lady Jessica and Kyle MacLachlan as Paul Atreides (1984)

Francesca Annis as Lady Jessica and Kyle MacLachlan as Paul Atreides (1984)The wonderful visual inventiveness of his guild navigators and planet-dwarfing space-ships remains impressive. And, once I had learned to recalibrate my expectations, I found his relish for teaasingly gnomic lines ("A beginning is a very delicate time" - Princess Irulan; "We have worm-sign such as God has never seen" - Stilgar; "The sleeper must awaken" - Duke Leto; "Tell me of your homeworld, Usul" - Chani; "The Spice must flow!" - passim) a source of rich entertainment at each of many reviewings over the years.

Sean Young as Chani with Paul Muad'Dib (1984)

Sean Young as Chani with Paul Muad'Dib (1984)Francesca Annis was a spectacularly beautiful Lady Jessica, Sean Young played Chani as a kind of slinky cat-woman, and Patrick Stewart as Gurney Halleck looked super-cool, as always. Kyle MacLachlan - well, what can you say? He seemed to be in training for Agent Cooper in Twin Peaks already, but then one doesn't go to Grand Opera for gritty realism.

John Harrison, dir.: Frank Herbert's Dune: TV Miniseries (2000)

John Harrison, dir.: Frank Herbert's Dune: TV Miniseries (2000)There were, of course, omissions. Putting so large a plot into one movie required some fairly violent surgery, but these were interestingly reexamined in John Harrison's 3-part miniseries, some fifteen years later.

Frank Herbert’s Dune, dir. & writ. John Harrison (based on the novel by Frank Herbert) – with William Hurt, Alec Newman, Saskia Reeves, Susan Sarandon, Daniela Amavia – (USA, 2000)

Alec Newman made a far more plausible Paul than MacLachlan had. He looked streetwise and desert-hardened from the very beginning, and only Saskia Reeves seemed to have blundered in from some BBC kitchen sink drama by mistake. The fact that it was largely filmed in the Czech Republic also guaranteed some strikingly imaginative costume and set designs. All in all, it was a thoroughly creditable effort, which complemented rather than superseding Lynch's pioneering film.

John Harrison, dir.: Frank Herbert's Children of Dune: TV Miniseries (2003)

John Harrison, dir.: Frank Herbert's Children of Dune: TV Miniseries (2003)It was in the sequel that John Harrison's vision really started to pay off, though. The addition of Herbert's two sequels to the original Dune plotline helped greatly in fleshing out the true richness of the Dune universe. James McAvoy made a great Duke Leto, Paul Muad'Dib's son and heir - the future God Emperor of Dune of the fourth novel - and the complex intrigues and machinations surrounding the new Fremen imperium were spectacularly embodied on screen.

Frank Herbert’s Children of Dune, dir. & writ. John Harrison (based on the novels Dune Messiah and Children of Dune by Frank Herbert)– with James McAvoy, Alec Newman, Alice Krige, Susan Sarandon – (USA, 2003)

Alice Krige made a far better Lady Jessica than Saskia Reeves ever had, and most of the other casting decisions were similarly shrewd.

Denis Villeneuve, dir.: Dune: Part One (2021)

Denis Villeneuve, dir.: Dune: Part One (2021)All of which brings us, I guess, to the $64,000 question: what do you think of Denis Villeneuve's new film? I should begin by saying that for a Dune-ophile such as myself, any new movie based on Herbert's work is big news.

Dune: Part One, dir. Denis Villeneuve, writ. Denis Villeneuve, Jon Spaihts, & Eric Roth (based on the novel by Frank Herbert) – with Timothée Chalamet, Rebecca Ferguson, Oscar Isaac, Josh Brolin, Stellan Skarsgård, Dave Bautista, Zendaya, Charlotte Rampling, Jason Momoa, Javier Bardem – (USA, 2021)

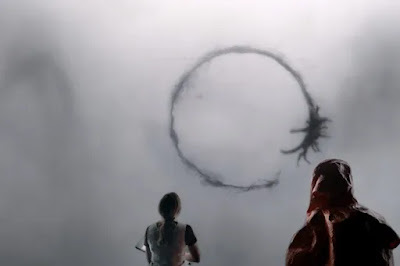

Denis Villeneuve, dir. Arrival (2016)

Denis Villeneuve, dir. Arrival (2016)Having said that, I guess that I have to make a couple of provisos. First of all, I do find some of the adulation heaped on Villeneuve's sci-fi movies to date a bit misplaced. Arrival was, I thought, very good - mainly because of the ingenious plot of Ted Chiang's original short story.

I did my level best to like Blade Runner 2049, and - once again - found some points of interest in its approach to the tried-and-true android theme, but already a certain visual blankness seemed to be standing in for the seedy baroque magnificence of Ridley Scott's imagination.

Denis Villeneuve, dir. Blade Runner 2049 (2017)

Denis Villeneuve, dir. Blade Runner 2049 (2017)Dune, too, looked frustratingly blank to me. The city of Arrakeen looked like an old concrete gun emplacement beefed up with a bit of CGI. The spaceships were larger and emptier than David Lynch's, but otherwise they lacked distinction - or any particular role beyond spectacle. Any cinema-goer these days has seen a few too many such space-scapes already.

What, then, of the performances? Some pretty impressive actors had been recruited to fill these oh-so-familiar roles, but they had - in almost every case - little to work with in the minimalist script. For all the richness of the plot material to get through in the first half of Herbert's book, this Dune (Part One) (as it's coyly labelled) seems to devote an inordinate amount of time to its characters' apparent desire to stare out to sea, or into space, or into the desert, without much to say.

It's not that I don't concede that internal monologues were somewhat overused as a device by Lynch, but that was a true reflection of Frank Herbert's own practice, and without them there's seldom enough in the dialogue to explain what's going on.

Who, then, stands out? Not, I'm afraid, Timothée Chalamet, who does a good enough job of playing the callow, young heir of a noble house, but shows few signs of his coming metamorphosis into Paul Muad'Dib, Messiah of Arrakis and Galactic Kwisatz Haderach. His puzzlement at the welcome he receives on arrival at the desert planet Arrrakis is, I fear, echoed by much of the cinema audience. There's just not a lot to him - at this point, at any rate.

Rebecca Ferguson as Lady Jessica

Rebecca Ferguson as Lady JessicaRebecca Ferguson as Jessica? Wonderful, I'm glad to say. It's true that I was already a bit of a fan, but she is, to me, the only actor on screen who seems actually to be there, on a strange, forbidding planet, caught in the toils of her Bene Gesserit sisterhood's plans.

Oscar Isaac - meh; Josh Brolin - God knows what movie he thought he was in; Stellan Skarsgård - a very disappointing Baron Harkonnen: a Halloween mask could have performed with more distinction; Dave Bautista - another massively talented comic actor, reduced to playing a thuggish sidekick; Zendaya - reduced mainly to wandering around in dream sequences; Chang Chen - when one thinks of what the late lamented Dean Stockwell made of his Doctor Yueh, this one seems pretty close to nothing; Sharon Duncan-Brewster - actually this seemed rather a nice notion: Max von Sydow (needless to say) was great in the role of Doctor Liet-Kynes, the imperial planetary ecologist, in the 1984 movie, but changing the character's gender and ethnicity made her far more believable, as well as the fact that she seemed more interested than most of the other in doing some actual acting; Charlotte Rampling - if you insist on hiding one of the best-known faces in cinema behind a rope net, little can be expected, and little was accordingly achieved: both of the previous cinematic Reverend Mothers were far superior; Jason Momoa - another interesting casting idea, but his obvious desire to be doing something all the time made him seem a bit out of step with the passivity of the production as a whole; and (last and unfortunately least) Javier Bardem - a dreadfully ill-judged casting decision; was he worse than the equally out-of-place Everett McGill's Stilgar in the original movie? He was certainly no better, that's for sure.

Cast Members of Dune

Cast Members of DuneA lot of the problems here come down to a single factor. Denis Villeneuve seems entirely to lack a sense of humour. In the case of very intense, confined dramas, this can lead to highly effective results: in his early film Incendies (2010), for instance, or even his first Hollywood film Prisoners (2013).

But when the action portrayed is a bit over-the-top (which is a good description of Herbert's work in general), he seems to lack the tonal sense of how to shift registers, make it somehow less unbelievable with a well-timed joke or the adoption of a slightly less ponderous approach to things. Hence the strange trainwreck that was the film Sicario: a lot of nonsense about a very serious subject - a theme treated far more adroitly in Breaking Bad. Hence, too, the nasty and irrelevant psychopath subplot in his Blade Runner sequel: a tiresome intrusion on a film whose legitimate interests lay elsewhere.

Jared Leto in Blade Runner 2049 (2017)

Jared Leto in Blade Runner 2049 (2017)To do the director credit, there's no character in Dune as irritating as Jared Leto in Blade Runner 2049, but Villeneuve still doesn't seem to understand that if you take out virtually all the background trimmings and subtleties from Frank Herbert's universe, you're left not with austerity but boredom. Cracking a joke or two, always David Lynch's first instinct to relieve the tension, seems to be quite off the agenda. There's not even any room in all these hours of cinema for a character so gleefully anarchic as Julie Cox's Princess Irulan in the John Harrison version.

Julie Cox in Frank Herbert's Dune (2000)

Julie Cox in Frank Herbert's Dune (2000)Vague disappointment - that, I'm afraid, was the emotion I was left with. There was indeed much there on screen to enjoy (I particularly liked the dragonfly-like thopters).

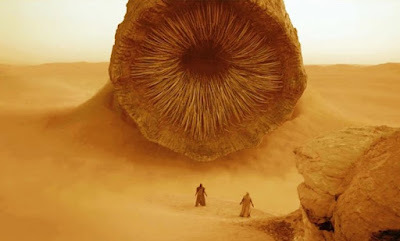

Shai-Hulud (2021)

Shai-Hulud (2021)As I said before, any Dune movie is cause for celebration among the faithful (the ones who intone "the Spice must flow" at regular intervals, and make a peculiar hand gesture at each appearance of the great sandworm, Shai-Hulud: "May His passage cleanse the world"). But Denis Villeneuve is no Ridley Scott, and there's little point in having such inflated expectations of him.

Shai-Hulud (2000)

Shai-Hulud (2000)Naturally I'll be trotting off to see Part Two when it's released - if only to admire the Garbo-esque Rebecca Ferguson once again - and (who knows?) maybe this time Villeneuve'll pull out the stops a bit further. He's promised as much, after all.

Shai-Hulud (1984)

Shai-Hulud (1984)But don't go dissing David Lynch in my presence anytime soon. A myth has grown up that his 1984 Dune movie was a disaster when it was, in fact, an eccentric masterpiece, one which gave fair warning of many transgressive cinematic excesses to come!

Floyd Snyder: The Dunes (2015)

Floyd Snyder: The Dunes (2015)•

Frank Herbert (1984)

Franklin Patrick Herbert Jr. [Frank Herbert]

(1920-1986)

The Dune Series:

Dune. [Part I, "Dune World": Analog (Dec 1963 – Feb 1964); Parts II and III, "The Prophet of Dune": Analog (Jan – May 1965)]. 1965. Times Mirror. London: New English Library, 1973.Dune Messiah. 1969. Times Mirror. London: New English Library, 1973.Children of Dune. 1976. Times Mirror. London: New English Library, 1977.God Emperor of Dune. 1981. London: New English Library, 1982.Heretics of Dune. 1984. London: New English Library, 1985.Chapter House Dune. 1985. London: New English Library, 1986.

The Pandora Sequence [aka the WorShip series]:

Destination: Void. 1966. Rev. ed. 1978. Penguin Science Fiction. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985.[with Bill Ransom]: The Jesus Incident. 1979. An Orbit Book. London: Futura Publications Limited, 1980.[with Bill Ransom]: The Lazarus Effect. 1983. An Orbit Book. London: Futura Publications Limited, 1984.[with Bill Ransom]: The Ascension Factor. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1988.

The ConSentiency Series:

Whipping Star. 1970. Times Mirror. London: New English Library, 1978.The Dosadi Experiment. 1977. A Futura Book. London: Futura Publications Limited, 1979.

Other Novels:

The Dragon in the Sea. 1956. [aka 'Under Pressure' and '21st Century Sub']. Penguin Science Fiction. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1963.The Green Brain. 1966. Times Mirror. London: New English Library, 1979.The Eyes of Heisenberg. 1966. Times Mirror. London: New English Library, 1976.The Heaven Makers. 1968. London: New English Library, 1982.The Santaroga Barrier. New York: Berkeley, 1968.Soul Catcher. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1972.The Godmakers. ["You Take the High Road", Astounding (May 1958); "Missing Link", Astounding (Feb 1959); "Operation Haystack", Astounding (May 1959); "The Priests of Psi", Fantastic (Feb 1960)]. 1972. London: New English Library, 1984.Hellstrom's Hive. New York: Doubleday, 1973.Direct Descent. New York: Ace Books, 1980.The White Plague. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1982.[with Brian Herbert] Man of Two Worlds (with Brian Herbert), New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1986.High-Opp. WordFire Press, 2012.Angels' Fall. WordFire Press, 2013.A Game of Authors. WordFire Press, 2013.A Thorn in the Bush. WordFire Press, 2014.

Short Story Collections:

The Worlds of Frank Herbert. 1970. Times Mirror. London: New English Library, 1975.The Book of Frank Herbert. New York: DAW Books, 1973.The Best of Frank Herbert. London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1975.The Priests of Psi. London: Gollancz Ltd, 1980.Eye. Illustrated by Jim Burns. 1985. New English Library. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1988.[with Brian Herbert & Kevin J. Anderson]. The Road to Dune. Foreword by Bill Ransom. London: Hodder & Stoughton Ltd., 2005.The Collected Stories of Frank Herbert. New York: Tor Books, 2014.

Secondary:

Brian Herbert. Dreamer of Dune: The Biography of Frank Herbert. New York: Tor Books, 2003

•

The Dune Saga (1965-1986)

The Dune Saga (1965-1986)

Published on December 11, 2021 12:59

December 6, 2021

Classic Ghost Story Writers: Wilkie Collins

The Woman in White (1982)

The Woman in White (1982)Recently Bronwyn and I rewatched this old British miniseries from the 1980s - The Woman in White. I remember back in the day experiencing ever increasing anxiety and horror as poor Jenny Seagrove sank deeper and deeper into the clutches of the evil Count Fosco.

Wilkie Collins: The Woman in White (1860)

Wilkie Collins: The Woman in White (1860)Which makes it sound like a kind of comic melodrama, but anyone who's ever read the novel knows it to be anything but. The creepy, claustrophobic atmosphere of the story seems to come out of some profound depth of personal paranoia and depression. Some of this can be perhaps attributed to Wilkie Collins' habit of taking opium, which took an ever greater hold on him in the decades after this, his first great success.

Deadwood, Series 1, episode 10: Mr. Swearengen & Mr. Wu (2004)

Deadwood, Series 1, episode 10: Mr. Swearengen & Mr. Wu (2004)But then, the nineteenth century was full of 'dope-fiends' (as Al Swearengen in Deadwood was wont to refer to them), and none of the others showed any signs of producing anything like The Woman in White ...

Kathleen Tillotson: Novels of the Eighteen-Forties (1954)

Kathleen Tillotson: Novels of the Eighteen-Forties (1954)Or did they? Kathleen Tillotson's fascinating book on the English novel of the 1840s points out a number of its distinctive features: a greater sexual frankness, in particular, than was possible later, as the Victorian era gradually became more and more morally bankrupt and intellectually stultifying.

Given that the four novels she chose to illustrate her thesis were Dickens' Dombey & Son (1848), Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre (1847), Elizabeth Gaskell's Mary Barton (1848) and Thackeray's Vanity Fair (1848), she might actually have called it "Novels of 1848", if it weren't for the fact that that would have sounded as if she meant to draw some parallel with the Year of Revolution.

Charles Dickens: Great Expectations (1860)

Charles Dickens: Great Expectations (1860)What, then, of the novel of the 1860s - the decade dominated by Wilkie Collins and The Woman in White? If, like me, you have a taste for the intricate pathways of the disturbed mind, spiritualism and psychogeography, then this is certainly the period for you.

Dostoevsky did not begin to appear in English translation until the 1880s, so it would be difficult to draw close parallels with Crime and Punishment (1867) or his memoir of exile in Siberia, The House of the Dead (1862). Victor Hugo's Les Misérables (1862) certainly had a strong influence on the English writers of the 1860s, however.

But the fact remains that The Woman in White predated all this, so the craze for novels of mystery and the occult does have to be seen as a home-grown phenomenon - a reaction, perhaps, to the predominant social realism of the preceding decades.

Mary Elizabeth Braddon: Lady Audley's Secret (1862)

Mary Elizabeth Braddon: Lady Audley's Secret (1862)Lady Audley's Secret was (in John Sutherland's words) "the most sensationally successful of all the sensation novels."

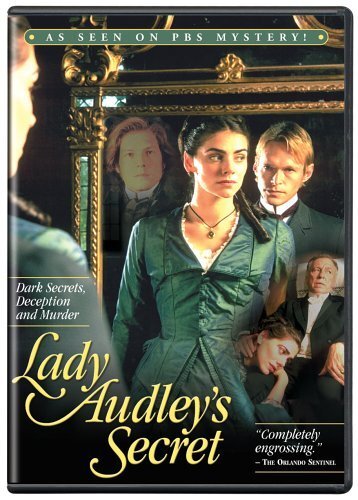

Lady Audley's Secret (2000)

Lady Audley's Secret (2000)Elaine Showalter accounts for at least some of its appeal when she summarises it as follows:

Braddon's bigamous heroine deserts her child, pushes husband number one down a well, thinks about poisoning husband number two and sets fire to a hotel in which her other male acquaintances are residing.

Wilkie Collins: (1862)

Wilkie Collins: (1862)The same anxieties about gender and the chafing constraints it imposes on individual freedom can be seen in Wilkie Collins' follow-up to the Woman in White. is an almost equally fascinating novel, which has unfortunately languished under the shadow of its supererogatory predecessor. Its heroine, Magdalen, while not quite as anarchic as Lady Audley, is just as determined to make her way in the world - in spite of the unfair obstacle of illegitimacy.

Charles Dickens: Our Mutual Friend (1864)

Charles Dickens: Our Mutual Friend (1864)By now Dickens, too, was affected by the trend. His last completed novel, Our Mutual Friend, is a strangely labyrinthine narrative full of doubles and dead men who won't lie down. It does include a love story - of a sort - but the nightmarish vision of a spectral London it concentrates on makes it, for most Dickensians, either their favourite or their least favourite among his works. I am, mind you, decidedly of the former persuasion.

Some of these 'sensationalist' tendencies were already apparent in its immediate predecessor Great Expectations - with its speaking tombstones and hideous convicts - the return of the repressed with a vengeance. Our Mutual Friend took him much further down the peculiar paths of the guilty conscience, however.

J. Sheridan Le Fanu: Uncle Silas (1864)

J. Sheridan Le Fanu: Uncle Silas (1864)There is a certain atmosphere of playacting, at times, even in the most bloodcurdling of these mystery novels. Those written by English writers, at any rate. The same could not be said of Sheridan Le Fanu's Uncle Silas. As in his ghost stories, Le Fanu shows every sign of believing what he writes, and of having a more intimate acquaintance with evil than any of his contemporaries.

Uncle Silas is grotesque, exaggerated, even burlesque at times, but it's not actually unbelievable. There's something only too credible about it all, since its author is clearly not joking. Killing a young girl for her inheritance is a standard melodramatic plot from way back, but if you did mean to do it, this might be how you might go about it. And, after all, it is something people do do - and did do - so it can't really be dismissed as a fantasy.

Wilkie Collins: Armadale (1866)

Wilkie Collins: Armadale (1866)I suppose that Wilkie Collins must have felt the pressure of all this competition, because his next novel, Armadale, really pulls out the stops. I must confess that there were moments while reading it when I could hardly believe my eyes. Did he really just say that? Shipwrecks, doubles, hauntings - you name it, it's all there.

The fever of an opium dream is combined here with the precision of a forensic accountant. I think it's safe to say that there can be few weirder novels in the whole of English literature than Collins's Armadale.

Wilkie Collins: The Moonstone (1868)

Wilkie Collins: The Moonstone (1868)But in the end, this was the one that scooped the pot. Long famed as the first English detective story, The Moonstone, too, has opium dreams, sinister orientals, lurking gypsies, damsels in distress, and all the usual trappings of a Wilkie Collins fantasia. The method of telling it through overlapping documents - while hackneyed enough - is deployed particularly effectively here.

I suppose, in the long run, it can't really be compared with the spectral complexities of The Woman in White, one of the great English novels, but it is understandable how many people still prefer The Moonstone to any of its predecessors.

Charles Dickens: The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870)

Charles Dickens: The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870)And, since one has to end somewhere when discussing the sensation novel of the 1860s, where better than with Dickens' last, unfinished novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood?

It can't really be judged as a novel, since only the opening portions survive, but they're enough to convince readers then and now that a radical readjustment both of style and subject matter was going on in their favourite author. From the opening scene in an opium parlour to the strange, haunted cathedral which dominates it, Edwin Drood reads more like a precursor of Kafka than a natural outgrowth of what had gone before in Dickens' work.

Unfortunately it proved difficult for Wilkie Collins to keep up these levels of intensity in his subsequent work. Many of his later novellas and short stories show just as much invention and skill as these long works of his maturity, but his novels began to suffer from the diffusion of concentration attendant on his longterm addiction.

Sheridan Le Fanu, too, having written a succession of strange masterpieces in the 1860s, fell off in his later work (except, again, in short stories such as the ones in his 1872 collection In A Glass Darkly). If you do want to go on from Uncle Silas, though, all three of the novels below can be strongly recommended: The House by the Churchyard. 1863. Introduction by Elizabeth Bowen. The Doughty Library. London: Anthony Blond, 1968.Wylder’s Hand. 1864. New York: Dover, 1978.Guy Deverell. 1865. New York: Dover, 1984.

The Mystery of Edwin Drood (UK, 2012)

The Mystery of Edwin Drood (UK, 2012)•

John Everett Millais: Wilkie Collins (1850)

John Everett Millais: Wilkie Collins (1850)William Wilkie Collins

(1824-1889)

Novels:

Iolani, or Tahiti as it was: A Romance. 1844 (1999)Antonina (1850)Basil (1852)Hide and Seek (1854)The Dead Secret (1856)A Rogue's Life (1856/1879)The Woman in White (1860)The Woman in White. 1860. Ed. John Sutherland. 1996. Oxford World's Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.The Woman in White. 1860. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd., n.d. No Name (1862)No Name. 1862. Ed. Mark Ford. 1994. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2004. Armadale (1866)Armadale. 1864-66. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1977. The Moonstone (1868)The Moonstone. 1868. Introduction by Dorothy L. Sayers. Everyman’s Library, 979. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd. / New York: E. P. Dutton & Co. Inc., 1944.The Moonstone. 1868. Afterword by T. S. Eliot. 1928. Ed. Sandra Kemp. 1998. Penguin English Library. London: Penguin, 2012. Man and Wife (1870)Poor Miss Finch (1872)Poor Miss Finch. 1872. Ed. Catherine Peters. Oxford World's Classics. 1995. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. The New Magdalen (1873)The New Magdalen. 1873. Pocket Classics. 1993. Phoenix Mill, Thrupp, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Alan Sutton Publishing Limited, 1998. The Law and the Lady (1875)The Two Destinies (1876)The Fallen Leaves (1879)The Fallen Leaves. 1879. Pocket Classics. 1994. Phoenix Mill, Thrupp, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Alan Sutton Publishing Limited, 1997. Jezebel's Daughter [novelisation of Collins' play The Red Vial (1858)] (1880)The Black Robe (1881)Heart and Science (1883)I Say No (1884)'I Say No'. 1884. Pocket Classics. 1995. Phoenix Mill, Thrupp, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Alan Sutton Publishing Limited, 1998. The Evil Genius (1886)The Guilty River (1886)The Legacy of Cain (1889)[with Walter Besant] Blind Love (1890)

Short Stories:

Mr Wray's Cash Box. Or, the Mask and the Mystery. A Christmas sketch (1852)A Terribly Strange Bed (1852)Gabriel's Marriage (1853)The Ostler (1855)After Dark (1856)The Lady of Glenwith Grange (1856)[with Charles Dickens] The Wreck of the Golden Mary (1856)Dickens, Charles, & Wilkie Collins. The Wreck of the Golden Mary. 1856. Illustrated by John Dugan. Venture Library. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1961. [with Charles Dickens, Elizabeth Gaskell & Adelaide Anne Procter] A House to Let (1858)[with Charles Dickens, Elizabeth Gaskell, Adelaide Anne Proctor, George Sala & Hesba Stretton] The Haunted House (1859)The Queen of Hearts (1859)Miss or Mrs? (1873)Miss or Mrs? 1873. Pocket Classics. 1993. Phoenix Mill, Thrupp, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Alan Sutton Publishing Limited, 1995. The Frozen Deep and Other Stories (1874)The Frozen DeepThe Frozen Deep. 1874. London: Hesperus Press Limited, 2012. The Dream WomanJohn Jago's Ghost; or The Dead Alive The Haunted Hotel (1878)My Lady's Money (1879)Who Killed Zebedee? (1881)The Ghost's Touch and Other Stories (1885)Little Novels (1887)The Queen's RevengeMad MonktonSights A-FootThe Stolen MaskThe Yellow MaskSister Rose [with Charles Dickens] The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices (1890)Tales of Terror and the Supernatural. Ed. Herbert van Thal. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1972.

Non-fiction:

Memoirs of the Life of William Collins, Esq., R.A. (1848)Rambles Beyond Railways, or, Notes in Cornwall taken a-foot. Illustrations by Henry C. Brandling (1851)My Miscellanies (1863)

Plays:

[with Charles Dickens] The Frozen Deep (1857)The Red Vial (1858)[with Charles Dickens] No Thoroughfare (1867)Black and White (18––)Miss Gwilt (18––)

Secondary:

Peters, Catherine. The King of Inventors: A Life of Wilkie Collins. 1991. Minerva. London: Mandarin Paperbacks, 1992.

•

Wilkie Collins: After Dark (1856)

Wilkie Collins: After Dark (1856)

Published on December 06, 2021 18:37

November 16, 2021

SF Luminaries: John Wyndham

John Wyndham: Plan for Chaos (1951 / 2009)

Plan for Chaos is a very odd book. It's certainly not without interest. However, I think one can see why no publishers actually leapt at the chance of putting it out back in the early 1950s when veteran Sci-fi writer Frederik Pohl (then moonlighting as a literary agent for John Wyndham and various other clients) was shopping it around New York.

There's the Nazi angle. In that respect, it serves as a precursor to Philip K. Dick's alternative history classic The Man in the High Castle (1962), or - for that matter - M. K. Joseph's Tomorrow the World , written in the late 1970s but only published posthumously in 2020.

There's the evil clone angle. In some ways it's very like Ira Levin's The Boys from Brazil (1976), only this time with flying saucers thrown in: quite a novel plot-twist for 1951, given that the expression wasn't actually coined until 1947, as a result of Kenneth Arnold's claim that the objects he saw on June 24 of that year "moved like saucers skipping across the water."

Amazing Stories (1946)

One can see so much in it, and yet it somehow doesn't quite work - it isn't visceral, actual, like his breakthrough title The Day of the Triffids (1951), or even its successor The Kraken Wakes (1953).

I'm not sure how much I need to say about them. I wrote a piece focussing on my early reading of The Day of the Triffids, in particular, in the introduction to my New Zealand Speculative Fiction website. I doubt that it's necessary to repeat all that here.

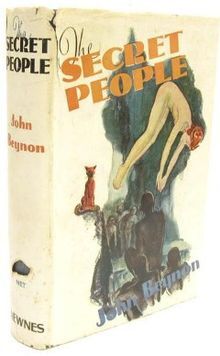

John Beynon: The Secret People (1935)

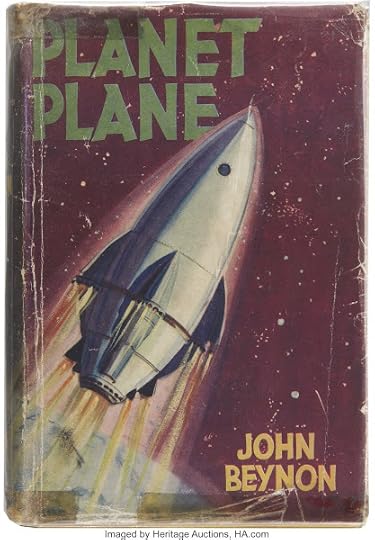

Nevertheless, having recently reread as much of his earlier work as I can easily access, it is facinating to see how many false starts one writer can have before settling into their mature style. There are flashes of Wyndham in all of the early novels, but the instinctively colonial attitudes displayed in both The Secret People (1935) and Planet Plane (1936) seem pretty repellent now.

John Beynon: Planet Plane (1936)

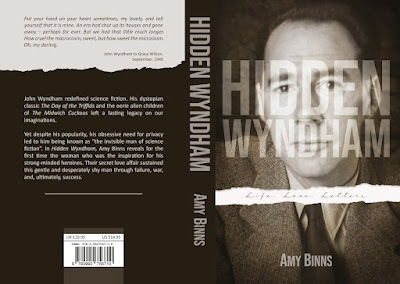

The John Wyndham heroine - smart, stylish, witty - familiar from later books begins to make an appearance quite early on, which is really the main attraction of these pre-war pulp serials and short stories. For those curious about how he came to create this character in the first place, Amy Binns' recent biography provides a number of new insights.

Amy Binns: Hidden Wyndham: Life, Love, Letters (2019)

It's probably not much of an exaggeration to say that without her book, the so-called "invisible man of Science Fiction" would have remained a shadowy figure, accessible only through his witty prose and a set of curiously repetitive ideas. Fatherless children, wiser than their elders (Chocky, The Chrysalids, The Midwich Cuckoos); alien invasions of the British countryside ("The Puffball menace", The Day of the Triffids, Trouble with Lichen); the oppressive nature of conventional domesticity ("Dumb Martian," "Survival," "Compassion Circuit") ... Binns supplies vital information about Jack Harris's early life which make seem these far less unaccountable.

But literary talent is, of course, not readily reducible to any such set of causes. Why did it take him so long to break through? Why did he persevere in the face of such steady discouragement? Where did those Triffids really come from?

H. G. Wells: SF Masterworks Series

We'll never know. It is, however, safe to say that without H. G. Wells, there would have been no John Wyndham. So many of his ideas - not to mention the ease of his story telling - find their roots in the vast turbulent sea of Wells's oeuvre (particularly the early SF romances and short stories). But Wyndham is not Wells: he lacks his didactic bent, and has a healthy cynicism about the expression of great ideas. His appeal was to as much to the readers of Evelyn Waugh and P. G. Wodehouse as it was to hard-core Sci-fi fans.

I suppose that John Wyndham's real tragedy was that his success came so late, and that he died so young. But then, that's more our tragedy than his. There's no doubt that he had more to say, but the few books he did write remain classics of the genre. The fact that they're still in print after half a century rather speaks for itself.

The John Wyndham Omnibus (1979)

A great deal of incidental information about him is available online at the John Wyndham Archive website. Beyond that, much though I would recommend Amy Binns's well-written and insightful biography, your first stopping-place should be the books themselves - from the Triffids onwards, at any rate. If you don't find them charming and absorbing at first sight, chances are he's not for you.

Brian AldissBillion Year Spree (1973)

In his 1973 history of the SF genre, Billion (later revised to 'Trillion') Year Spree, Brian Aldiss described John Wyndham's breakout books as ‘cosy catastrophes’:

Both novels [The Day of the Triffids and The Kraken Wakes] were totally devoid of ideas but read smoothly, and thus reached a maximum audience, who enjoyed cosy disasters. Either it was something to do with the collapse of the British Empire, or the back-to-nature movement, or a general feeling that industrialization had gone too far, or all three.Aldiss goes on to describe the characteristics of this ‘urbane and pleasing’ SF subgenre as follows:

The essence of cosy catastrophe is that the hero should have a pretty good time (a girl, free suites at the Savoy, automobiles for the taking) while everyone else is dying off … Such novels are anxiety fantasies. They shade off towards the greater immediacy of World War III novels, a specialist branch of catastrophe more usually practiced by American writers.He concludes with a rather premature epitaph on Wyndham and his ilk: ‘the race is not always to the swift, etc.’ Unfortunately, such dismissive judgements on a possible trade rival can cut both ways. Has Brian Aldiss himself fared much better?

Who (besides myself) now reads Non-stop (1958) or Hothouse (1962)? Who wades through The Malacia Tapestry or the Helliconia trilogy? Who remembers that one of Stanley Kubrick’s last film projects was an adaptation of Aldiss’s short story ‘Super-Toys Last All Season Long,’ which he delegated instead to Steven Spielberg, who turned it into the flawed, though not uninteresting, A.I.?

Steven Spielberg, dir.: A.I.: Artificial Intelligence (2001)

John Wyndham, by contrast, continues to be read. It seems safe to say now that he probably always will be. Aldiss's rather self-conscious attempts to be mod and up-to-the-minute sound even more uncomfortably dated now than what he saw as Wyndham's perverse determination to write "a kind of country-house science fiction."

And, as Hilaire Belloc once put it, speaking (perhaps) for all such writers who pop in and out of fashion with the passing years:

When I am dead, I hope it may be said:

"His sins were scarlet, but his books were read."

Amy Binns: Hidden Wyndham: Life, Love, Letters (2019)

•

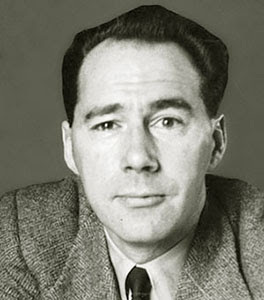

John Wyndham (1903-1969)

John Wyndham Parkes Lucas Beynon Harris

(1903-1969)

[His work appeared under a variety of pseudonyms, mostly constructed from his various initials: John Beynon, John Beynon Harris, John B. Harris, Johnson Harris, J. W. B. Harris, Lucas Parkes, Wyndham Parkes, & John Wyndham among them]

Novels:

[as 'John B. Harris']: The Curse of the Burdens. Aldine Mystery Novels No. 17 (London: Aldine Publishing Co. Ltd. 1927)

[as 'John Beynon']: The Secret People (1935)The Secret People. 1935. Coronet Books. London: Hodder Paperbacks Ltd., 1972.

Foul Play Suspected (London: Newnes, 1935)

Planet Plane [aka 'The Space Machine'] (1936)Stowaway to Mars. 1935. Coronet Books. 1972. London: Hodder Paperbacks Ltd., 1977.

[as 'John Wyndham']: The Day of the Triffids [aka 'Revolt of the Triffids']. 1951. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1954.

The Kraken Wakes [aka 'Out of the Deeps']. 1953. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1975.

The Chrysalids [aka 'Re-Birth']. 1955. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1974.

The Midwich Cuckoos. 1957. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1960.

Trouble with Lichen. 1960. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1963.

Chocky. 1968. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970.

Web. 1979. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1980.

Plan for Chaos. Ed. David Ketterer & Andy Sawyer. 2009. Introduction by Christopher Priest. London: Penguin, 2010.

Short Story Collections:

Jizzle. 1954. Four Square. London: New English Library, 1973.JizzleTechnical SlipA Present from BrunswickChinese PuzzleEsmeraldaHow Do I Do?UnaAffair of the HeartConfidence TrickThe WheelLook Natural, Please!Perforce to DreamReservation DeferredHeaven ScentMore Spinned Against

The Seeds of Time. 1956. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972.Foreword by John WyndhamChronoclasmTime To RestMeteorSurvivalPawley's PeepholesOpposite NumberPillar To PostDumb MartianCompassion CircuitWild Flower

Tales of Gooseflesh and Laughter [US selection from 'Jizzle' and 'The Seeds of Time'] (1956)Chinese PuzzleUnaThe WheelJizzleHeaven ScentCompassion CircuitMore Spinned AgainstA Present from BrunswickConfidence TrickOpposite NumbersWild Flower

[with 'Lucas Parkes']: The Outward Urge. 1959 & 1961. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1962.The Space Station A.D. 1994 [aka 'For All the Night'] (1958)The Moon A.D. 2044 [aka 'Idiot’s Delight'] (1958)Mars A.D. 2094 [aka 'The Thin Gnat-Voices'] (1958)Venus A.D. 2144 [aka 'Space Is a Province of Brazil'] (1958)The Asteroids A.D. 2194 [aka 'The Emptiness of Space'] (1960)

Consider Her Ways and Others. 1961. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971.Consider Her WaysOddStitch in TimeOh Where, Now, is Peggy MacRafferty?Random QuestA Long Spoon

The Infinite Moment [US edition of 'Consider Her Ways and Others', with two stories replaced] (1961)Consider Her WaysOddHow Do I DoStitch In TimeRandom QuestTime Out

The Best of John Wyndham. London: Sphere Books Ltd., 1973.The Lost Machine (1932)The Man from Beyond (1934)The Perfect Creature (1937)The Trojan Beam (1939)Vengeance by Proxy (1940)Adaptation (1949)Pawley's Peepholes (1951)The Red Stuff (1951)And the Walls Came Tumbling Down (1951)Dumb Martian (1952)Close Behind Him (1952)The Emptiness of Space (1960)

[as ‘John Beynon’]: Sleepers of Mars. Introduction by Walter Gillings. Coronet Books. 1973. London: Hodder Paperbacks Ltd., 1973.The Fate of the Martians, by Walter GillingsSleepers of Mars (1939)Worlds to Barter (1931)Invisible Monster (1933)The Man from Earth (1934)The Third Vibrator (1933)

[as ‘John Beynon Harris’]: Wanderers of Time. Introduction by Walter Gillings. Coronet Books. 1973. London: Hodder Paperbacks Ltd., 1974.Before the Triffids, by Walter GillingsWanderers of Time [aka 'Love in Time'] (1933)Derelict of Space (1939)Child of Power (1939)The Last Lunarians (1934)The Puff-Ball Menace [aka 'Spheres of Hell'] (1933)

[as ‘John Beynon’]: Exiles on Asperus. Coronet Books. 1979. London: Hodder Paperbacks Ltd., 1980.Exiles on Asperus (1933)No Place Like Earth (1951)The Venus Adventure (1932)

No Place Like Earth [Some stories previously published in 'Jizzle', 'The Seeds of Time', 'Consider Her Ways and Others', Wanderers of Time ' and ' Exiles on Asperus '] (2003) Derelict of Space Time to Rest No Place Like Earth In Outer Space There Shone a StarBut a Kind of a GhostThe Cathedral CryptA Life PostponedTechnical SlipUnaIt's a Wise ChildPillar to PostThe StareTime Stops TodayThe MeddlerBlackmoilA Long Spoon

Short stories:

[Included in Jizzle (1954); The Seeds of Time (1956);

Consider Her Ways and Others / The Infinite Moment {CW / IM} (1961);

Sleepers of Mars / Wanderers of Time / Exiles on Asperus {SM / WT / EA} (1973, 1974, 1979);

The Best of John Wyndham / No Place Like Earth {Best / NPE} (1973, 2003)]