Jack Ross's Blog, page 14

January 6, 2021

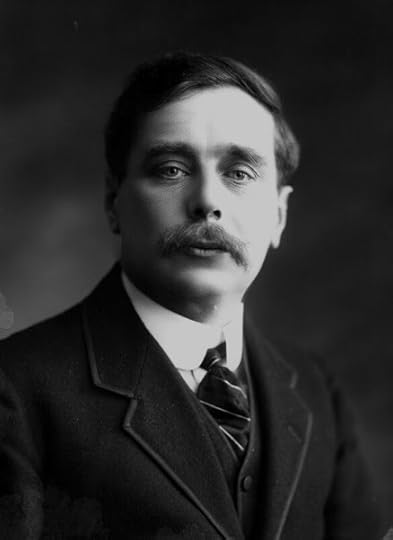

SF Luminaries: H. G. Wells

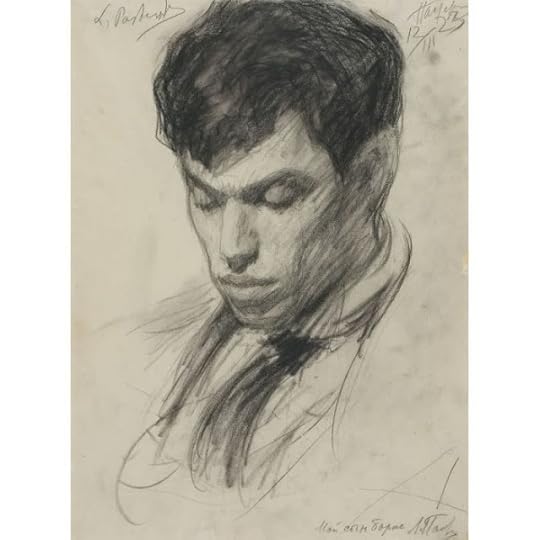

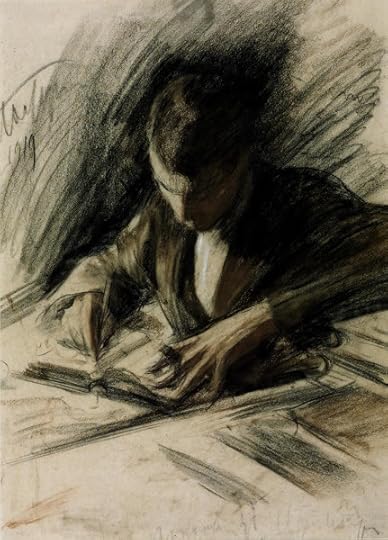

H. G. Wells (1911)

"I beg your pardon, sir," he said in his rather thin cockney voice, "is this your book?"

"It doesn't matter at all," said Wimsey gracefully, "I know it by heart. I only brought it along with me because it's handy for reading a few pages when you're stuck in a place like this for the night. You can always take it up and find something entertaining."

"This chap Wells," pursued the red-haired man, "he's what you'd call a very clever writer, isn't he? It's wonderful how he makes it all so real, and yet some of the things he says, you wouldn't hardly think they could really be possible. ...

Dorothy L. Sayers: Hangman's Holiday (1933)

So begins the first story, "The Image in the Mirror", in Dorothy Sayer's detective story collection Hangman's Holiday. Lord Peter Wimsey's interlocutor goes on to discuss with him the implications of H. G. Wells's "The Plattner Story", an account of a schoolmaster who gets blown into the fourth dimension and comes back reversed: his left turned to right, his right to left.

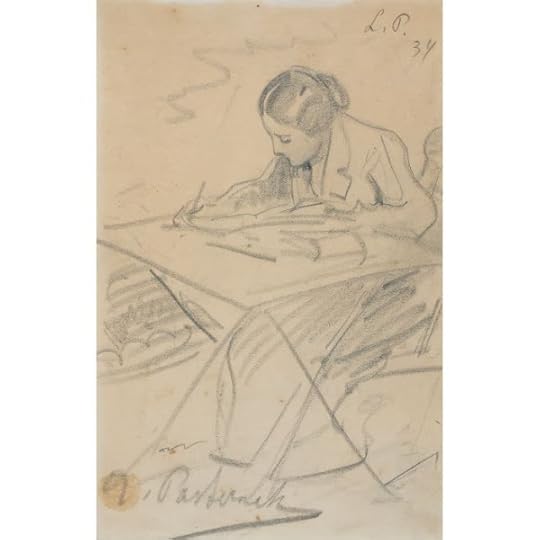

The Short Stories of H. G. Wells (1927)

It's pretty clear that the book they're discussing is the then fairly recently published omnibus edition of The Short Stories of H. G. Wells. What I find most interesting about their conversation, though, is Wimsey's throwaway line about knowing it "by heart".

There was a time when this was my favourite book in the world, and I too knew it virtually by heart. In fact, I had a kind of ritual which involved trying to read the whole thing - all 1100-odd pages - in one day, but it's not an experiment I would really recommend.

H. G. Wells: Short Stories (1952)

By then the stories were so familiar to me that I could practically recite them, racing from The Time Machine:

The Time Traveller (for so it will be convenient to speak of him) was expounding a recondite matter to us.... all the way through to "A Dream of Armageddon", with its wonderfully poetic last lines:

"Nightmares," he cried; "nightmares indeed! My God! Great birds that fought and tore."

H. G. Wells: Complete Short Stories (1970)

Although it was subsequently reprinted under the title The Complete Short Stories, the collection is by no means that - Wells, after all, had another two decades to live when it first appeared.

The 62 stories (and one essay) are divided into five sections, four of which reprint earlier stand-alone collections of Wells's:

The opening section, The Time Machine and Other Stories, never published separately in book form, contains some of his strongest stories, published piecemeal throughout the 1890s. There are also another five separate stories grouped between sections 4 and 5 (for fuller details, see my breakdown of the contents in the Bibliography below).

The Stolen Bacillus and Other Incidents [1895]The Plattner Story and Others [1897]Tales of Space and Time [1899]Twelve Stories and a Dream [1903]

John Hammond, ed.: The Complete Short Stories of H. G. Wells (1998)

There is, however, another collection entitled The Complete Short Stories . This one was edited by John Hammmond in 1998. As well as all of the stories included in the 1927 collection - with the exception of the short novel The Time Machine - it includes another 22, most of them previously published in Hammond's 1984 collection The Man With a Nose and Other Uncollected Stories of H. G. Wells.

No doubt further stories will continue to surface from time to time (for more information, see the "H. G. Wells Bibliography" page on Wikipedia), but for all intents and purposes, these 84 stories might as well be thought of as the established canon.

As Dave, one of the commentators on this book on Goodreads, informs us:

This collection tied for 4th on the Arkham Survey for Basic SF titles ... behind “Seven Science Fiction Novels” by H. G. Wells (the winner), Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World”, and Olaf Stapledon’s “Last and First Men”. It also finished 19th on the 1952 Astounding/Analog All-Time Poll.

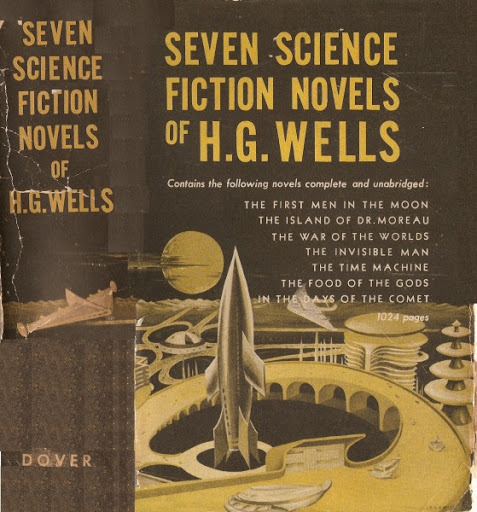

H. G. Wells: Seven Science Fiction Novels (1934)

Those seven novels were very well chosen. They consist of:

It's hard to imagine a more influential set of titles. Between them they introduced virtually every standard trope of the SF genre as it would develop over the next hundred years: space travel, time travel, alien invasion, utopian futures, genetic manipulation ... pretty much everything except robots (which would be added to the mix by Czech writer Karel Čapek's play R.U.R in 1920).

The First Men in the Moon [1901]The Island of Dr. Moreau [1896]The War of the Worlds [1898]The Invisible Man [1897]The Time Machine [1895]The Food of the Gods [1904]In the Days of the Comet [1906]

Karel Čapek: R.U.R (Rossum’s Universal Robots) (2015)

The dazzling talent of the young Wells seemed destined to sweep everything before it. As C. S. Lewis once quipped, however, as time went on he increasingly "traded his birthright for a pot of message" (if you don't get the pun, it's probably because you weren't brought up on the Authorised Version of the Bible. In the Book of Genesis, Esau trades his birthright to Jacob "for a mess of pottage"). Har-de-har-har. Maybe you had to be there ...

His later work does seem to lack the zest of those remarkable works of his first decade as a writer, but he remains one of the great sages and pathfinders for all subsequent work in the field of Speculative Fiction. The fact that he moved so easily from social satire to straight science fiction to the fantastic and supernatural (something very few of his successors succeeded in doing) meant that he avoided being typecast as a 'genre' writer. Though the sheer clarity and power of his prose also had a lot to do with that.

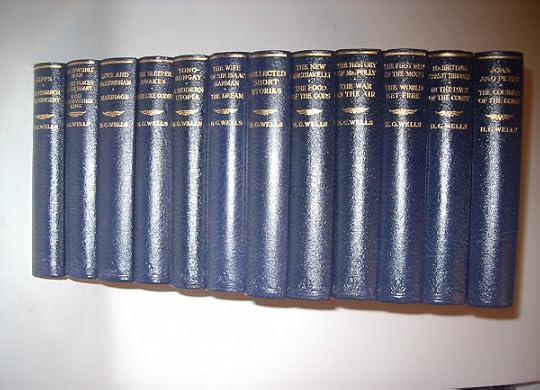

In 1930 Odhams Press published a 12-volume edition of his selected fiction which covered most of his major work in that form:

Odhams: H. G. Wells Collection (1930)

The H. G. Wells Collection. 12 vols. London: Odhams Press Limited, [1930]: The Invisible Man / The Secret Places of the Heart / God the Invisible King (1897, 1922 & 1917)Love and Mr Lewisham / Marriage (1900 & 1912)The First Men in the Moon / The World Set Free (1901 & 1914)Kipps / The Research Magnificent (1905 & 1915)Tono-Bungay / A Modern Utopia (1909 & 1905)The History of Mr Polly / The War in the Air (1910 & 1908)The Sleeper Awakes / Men Like Gods (1910 & 1923)The New Machiavelli / The Food of the Gods (1911 & 1904)The Wife of Sir Isaac Harman / The Dream (1914 & 1924)Mr Britling Sees it Through / In the Days of the Comet (1916 & 1906)Joan and Peter: A Story of an Education / "The Country of the Blind" / "Jimmy Goggles the God" / "Mr Brisher’s Treasure" (1918, 1904, 1898 & 1899)Collected Short Stories (1927)

H. G. Wells: The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896)

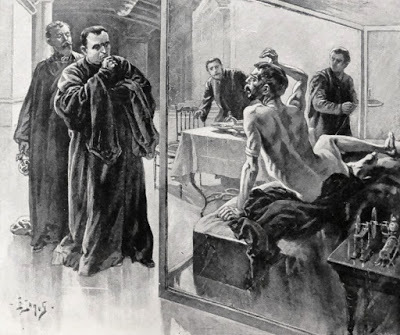

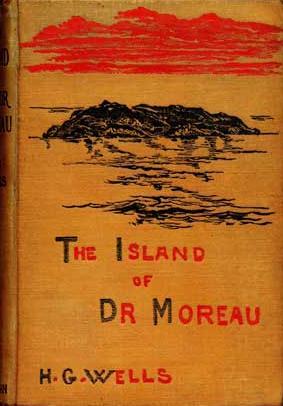

I suppose, if I had to choose myself from this gallery of masterpieces, the one I would go for would be The Island of Doctor Moreau. It's been filmed - badly - on more than one occasion (most recently with Val Kilmer and Marlon Brando in the principal roles), but the book itself has a haunting, nightmarish quality which completely entranced me when I first read it as a teenager.

John Frankenheimer, dir.: The Island of Doctor Moreau (1996)

The figure of the mad scientist, tampering with God's work without fear or scruple, who consequently gets his comeuppance, comes to us straight from Frankenstein, of course. But the colonial setting transfers it into the morally compromised world of the early Conrad: Almayer's Folly (1895), say, or An Outcast of the Islands (1896).

Don Taylor, dir.: The Island of Doctor Moreau (1977)

There are many themes jostling for dominance in this strange early story of Wells's: colonialism and colonial exploitation principal - in my view, at least - among them. One could almost see it as a counterblast to Kipling's Jungle Books (1894-1895). The strange parodic chants the half-animals live by certainly recall some of the stories and songs of Mowgli and his various brethren.

Big Finish: The Island of Doctor Moreau (2017)

The colonial theme continues to recur in Wells's later fiction: in The First Men in the Moon (1901) and - perhaps most explicitly - Tono-Bungay (1909). I suppose the thing which makes Wells's early fiction so durable, in fact, is its refusal to simplify or avoid difficult questions of exploitation and brutality.

Later, of course, when he became a sage, he seems to have felt a responsibility to the 'left' in general which put him in strange company: co-authoring a book with Josef Stalin is not something most of us would want on our CV. Expediency and responsibility choked the initial outrage he felt - as a writer - at injustice and cruelty, just as personal prosperity gradually robbed his social satire of its edge.

The important thing about H. G. Wells, though, is not so much that he went off the rails a bit in his later years, as the extraordinary heights he had to fall from. I would argue strongly that the best place to start is by reading the original edition of The Stories of H. G. Wells, in any of its innumerable reprints. After that, the Seven Science Fiction Novels of 1934 will supply most of the rest of his truly durable work.

H. G. Wells: The History of Mr Polly (1910)

Mind you, this leaves out a number of excellent contemporary novels - Kipps and The History of Mr Polly, for instance. The Sleeper Awakes and The War in the Air should probably have been included among the best of his early Science Fiction novels, too.

Henri Lanos: When the Sleeper Wakes (1899)

•

H. G. Wells Memorial Coin (2021)

The recent news that the Royal Mint has just issued a special coin commemorating 75 years since H. G. Wells's death certainly confirms his continuing importance in British (and world) culture. On the other hand, certain errors on the coin - documented at length by various critics - show how little accurate knowledge of his work people actually have:

As the name suggests, the tripod only had three legs in Wells' novel. "How many people did this have to go through? Did they know how to count? Do they know what the "tri" prefix means??" artist Holly Humphries asked on Twitter.

The War of the Worlds (2018)

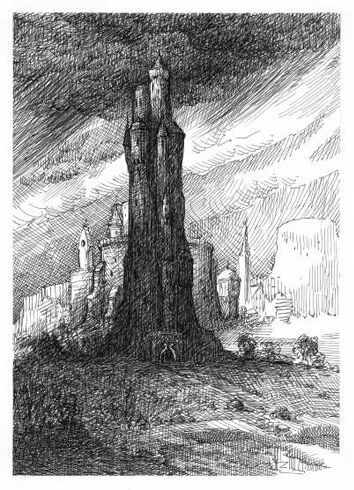

[Note the three legs and flexible limbs in the illustration above]

Not only this, but the portrait of the 'invisible man' on the coin has also drawn criticism:

Fans were also disappointed by the appearance of a top hat, supposedly in homage to Wells' book "The Invisible Man." The scientist Griffin, the titular Invisible Man, "was no gentleman, and did not wear a top hat," [Adam Roberts, vice-president of the H.G. Wells Society,] said.

"I suspect the designer has been influenced consciously or otherwise by DC Comics' 'Gentleman Ghost' - but he had nothing to do with Wells."

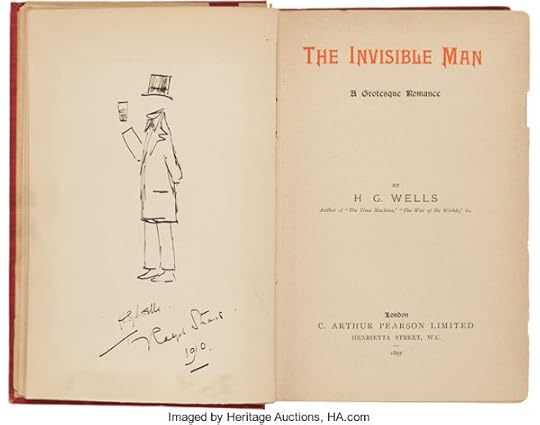

The Invisible Man (1897)

Here, however, I would have to take issue with the critics, whose knowledge of Victorian mores may not be quite so profound as they think. The original drawing above, by Wells himself, in a presentation copy of the book's first edition, clearly shows the invisible man in a top hat.

To complete the hat-trick, another flaw was spotted by Roberts, who said:

"The legend written around the rim of the coin, 'GOOD BOOKS ARE THE WAREHOUSES OF IDEAS', is (though it's sometimes attributed to Wells by various internet quote-sites) not an actual quotation by Wells."Chris Costello, the coin's designer, remains defiant, insisting that "he was intentionally reinterpreting imagery from Wells' works for a modern audience."

"The characters in 'War of the Worlds' have been depicted many times, and I wanted to create something original and contemporary," he said.I'll certainly grant that the choice of a four-legged tripod is "original" (though possibly somewhat misguided), and I don't think any responsibility can be laid at Costello's door for the probably spurious quotation, so I suppose the whole affair remains more a cause for celebration than carping criticism. I do wish, though, that artists would make a point of always - not just sometimes - reading the books they've been asked to illustrate.

"My design takes inspiration from a variety of machines featured in the book - including tripods and the handling machines which have five jointed legs and multiple appendages. The final design combines multiple stories into one stylized and unified composition that is emblematic of all of H.G. Well's (sic) work and fits the unique canvas of a coin."

Bernard Bergonzi: The Early H. G. Wells (1961)

•

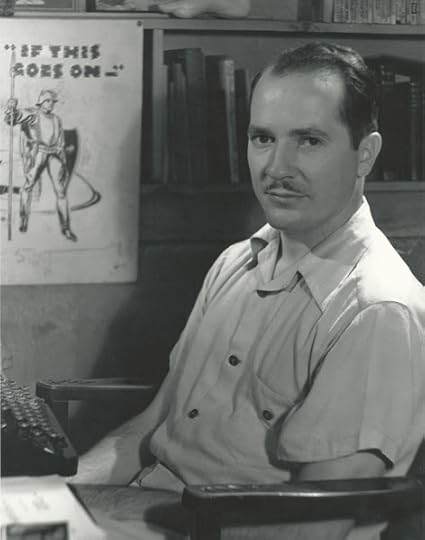

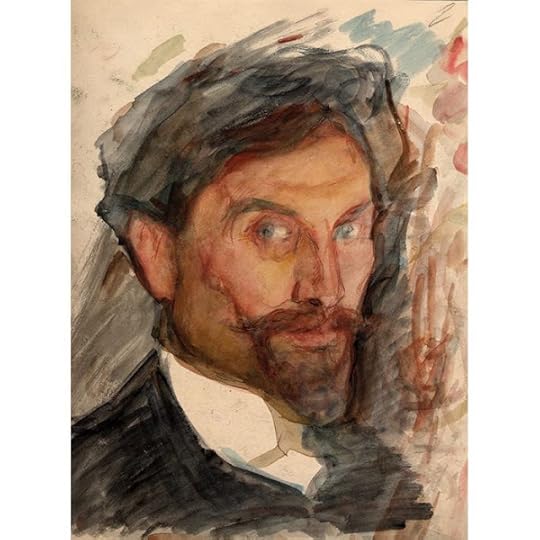

George Charles Beresford: H. G. Wells (1920)

Herbert George Wells

(1866-1946)

Novels:

The Time Machine (1895)The Short Stories of H. G. Wells. 1927. London: Ernest Benn Limited, 1952.The Wonderful Visit (1895)The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896)The Island of Doctor Moreau. 1896. A Magnum Easy Eye Book. New York: Lancer Books, Inc., 1968.The Wheels of Chance (1896)The Invisible Man (1897)The Invisible Man / The Secret Places of the Heart / God the Invisible King. 1897, 1922 & 1917. H. G. Wells Collection. London: Odhams Press Limited, [1930].The War of the Worlds (1898)The War of the Worlds. 1898. Penguin Science Fiction. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1963.When the Sleeper Wakes (1899)When the Sleeper Wakes. 1899. London: Macmillan & Co. Limited, 1906.Love and Mr Lewisham (1900)Love and Mr Lewisham / Marriage. 1900 & 1912. H. G. Wells Collection. London: Odhams Press Limited, [1930].Love and Mr Lewisham. 1900. Introduction by Frank Wells. 1954. Collins Classics. London & Glasgow: Collins Clear-Type Press, 1959. The First Men in the Moon (1901)The First Men in the Moon / The World Set Free. 1901 & 1914. H. G. Wells Collection. London: Odhams Press Limited, [1930].The First Men in the Moon. 1901. Introduction by Frank Wells. Fontana Books. London: Collins Clear-Type press, 1966.The Sea Lady (1902)The Sea Lady: A Tissue of Moonshine. 1902. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1948.The Food of the Gods and How It Came to Earth (1904)The Food of the Gods. 1904. Introduction by Ronald Seth. Collins Classics. London & Glasgow: Collins Clear-Type Press, 1955.Kipps (1905)Kipps / The Research Magnificent. 1905 & 1915. H. G. Wells Collection. London: Odhams Press Limited, [1930].A Modern Utopia (1905)Tono-Bungay / A Modern Utopia. 1909 & 1905. H. G. Wells Collection. London: Odhams Press Limited, [1930].In the Days of the Comet (1906)Mr Britling Sees it Through / In the Days of the Comet. 1916 & 1906. H. G. Wells Collection. London: Odhams Press Limited, [1930].The War in the Air (1908)The History of Mr Polly / The War in the Air. 1910 & 1908. H. G. Wells Collection. London: Odhams Press Limited, [1930].Tono-Bungay (1909)Tono-Bungay / A Modern Utopia. 1909 & 1905. H. G. Wells Collection. London: Odhams Press Limited, [1930].Ann Veronica (1909)Ann Veronica. 1909. Penguin Books 2887. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1968.The History of Mr Polly (1910)The History of Mr Polly / The War in the Air. 1910 & 1908. H. G. Wells Collection. London: Odhams Press Limited, [1930].The History of Mr Polly. 1910. Ed. A. C. Ward. The Heritage of Literature Series. London: Longmans, Green and Co. Ltd., 1959.The Sleeper Awakes (1910)The Sleeper Awakes / Men Like Gods. 1910 & 1923. H. G. Wells Collection. London: Odhams Press Limited, [1930].The New Machiavelli (1911)The New Machiavelli. 1911. Penguin Books 575. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1946.Marriage (1912)Love and Mr Lewisham / Marriage. 1900 & 1912. H. G. Wells Collection. London: Odhams Press Limited, [1930].The Passionate Friends (1913)The Passionate Friends. 1913. London: George Newnes, Limited, n.d.The Wife of Sir Isaac Harman (1914)The Wife of Sir Isaac Harman / The Dream. 1914 & 1924. H. G. Wells Collection. London: Odhams Press Limited, [1930].The World Set Free (1914)The First Men in the Moon / The World Set Free. 1901 & 1914. H. G. Wells Collection. London: Odhams Press Limited, [1930].Bealby: A Holiday (1915)Bealby: A Holiday. 1915. London: George Newnes, Limited, n.d.[as Reginald Bliss] Boon (1915)The Research Magnificent (1915)Kipps / The Research Magnificent. 1905 & 1915. H. G. Wells Collection. London: Odhams Press Limited, [1930].Mr Britling Sees It Through (1916)Mr Britling Sees it Through / In the Days of the Comet. 1916 & 1906. H. G. Wells Collection. London: Odhams Press Limited, [1930].The Soul of a Bishop (1917)Joan and Peter: The Story of an Education (1918)Joan and Peter: A Story of an Education / The Country of the Blind / Jimmy Goggles the God / Mr Brisher’s Treasure. 1918, 1904, 1898 & 1899. H. G. Wells Collection. London: Odhams Press Limited, [1930].The Undying Fire (1919)The Secret Places of the Heart (1922)The Invisible Man / The Secret Places of the Heart / God the Invisible King. 1897, 1922 & 1917. H. G. Wells Collection. London: Odhams Press Limited, [1930].Men Like Gods (1923)The Sleeper Awakes / Men Like Gods. 1910 & 1923. H. G. Wells Collection. London: Odhams Press Limited, [1930].The Dream (1924)The Wife of Sir Isaac Harman / The Dream. 1914 & 1924. H. G. Wells Collection. London: Odhams Press Limited, [1930].Christina Alberta's Father (1925)The World of William Clissold (1926)Meanwhile (1927)Mr. Blettsworthy on Rampole Island (1928)Mr. Blettsworthy on Rampole Island. London: Ernest Benn Limited, 1928.The Autocracy of Mr. Parham (1930)The Bulpington of Blup (1932)The Shape of Things to Come (1933)The Shape of Things to Come. 1933. Corgi SF Collector’s Library. London: Transworld Publishers Ltd., 1974.Things to Come: A Film Story Based on the Material Contained in His History of the Future “The Shape of Things to Come.” (1936)Things to Come: A Film Story Based on the Material Contained in His History of the Future “The Shape of Things to Come.” 1935. London: The Cresset Press, 1936.The Croquet Player (1936)Brynhild (1937)Star Begotten: A Biological Fantasia (1937)Star Begotten: A Biological Fantasia. 1937. Sphere Science Fiction. London: sphere Books Ltd., 1977.The Camford Visitation (1937)Apropos of Dolores (1938)The Brothers (1938)The Holy Terror (1939)Babes in the Darkling Wood (1940)All Aboard for Ararat (1940)You Can't Be Too Careful (1941)

Short Stories:

The Short Stories. 1927. London: Ernest Benn, 1948:

The Time Machine and Other Stories

The Time MachineThe Empire of the AntsA Vision of JudgementThe Land IroncladsThe Beautiful SuitThe Door in the WallThe Pearl of LoveThe Country of the Blind

The Stolen Bacillus and Other Incidents [1895]

The Stolen BacillusThe Flowering of the Strange OrchidIn the Avu ObservatoryThe Triumphs of a TaxidermistA Deal in OstrichesThrough a WindowThe Temptation of HarringayThe Flying ManThe Diamond MakerÆpyornis IslandThe Remarkable Case of Davidson's EyesThe Lord of the DynamosThe Hammerpond Park BurglaryThe MothThe Treasure in the Forest

The Plattner Story and Others [1897]

The Plattner StoryThe Argonauts of the AirThe Story of the Late Mr. ElveshamIn the AbyssThe AppleUnder the KnifeThe Sea-RaidersPollock and the Porroh ManThe Red RoomThe ConeThe Purple PileusThe Jilting of JaneIn the Modern Vein: An Unsympathetic Love StoryA CatastropheThe Lost InheritanceThe Sad Story of a Dramatic CriticA Slip Under the Microscope

The ReconciliationMy First AeroplaneLittle Mother Up the MörderbergThe Story of the Last TrumpThe Grisly Folk

Tales of Space and Time [1899]

The Crystal EggThe StarA Story of the Stone AgeA Story of the Days to ComeThe Man Who Could Work Miracles

Twelve Stories and a Dream [1903]

FilmerThe Magic ShopThe Valley of SpidersThe Truth About PyecraftMr. Skelmersdale in FairylandThe Inexperienced GhostJimmy Goggles the GodThe New AcceleratorMr. Ledbetter's VacationThe Stolen BodyMr. Brisher's TreasureMiss Winchelsea's HeartA Dream of Armageddon

The Complete Short Stories. Ed. John Hammmond. 1998. London: Phoenix, 1999:

The Stolen Bacillus and Other Incidents [1895]

The Stolen BacillusThe Flowering of the Strange OrchidIn the Avu ObservatoryThe Triumphs of a TaxidermistA Deal in OstrichesThrough a WindowThe Temptation of HarringayThe Flying ManThe Diamond MakerÆpyornis IslandThe Remarkable Case of Davidson's EyesThe Lord of the DynamosThe Hammerpond Park BurglaryThe MothThe Treasure in the Forest

The Plattner Story and Others [1897]

The Plattner StoryThe Argonauts of the AirThe Story of the Late Mr. ElveshamIn the AbyssThe AppleUnder the KnifeThe Sea-RaidersPollock and the Porroh ManThe Red RoomThe ConeThe Purple PileusThe Jilting of JaneIn the Modern Vein: An Unsympathetic Love StoryA CatastropheThe Lost InheritanceThe Sad Story of a Dramatic CriticA Slip Under the Microscope

Tales of Space and Time [1899]

The Crystal EggThe StarA Story of the Stone AgeA Story of the Days to ComeThe Man Who Could Work Miracles

Twelve Stories and a Dream [1903]

FilmerThe Magic ShopThe Valley of SpidersThe Truth About PyecraftMr. Skelmersdale in FairylandThe Inexperienced GhostJimmy Goggles the GodThe New AcceleratorMr. Ledbetter's VacationThe Stolen BodyMr. Brisher's TreasureMiss Winchelsea's HeartA Dream of Armageddon

The Door in the Wall and Other Stories

The Door in the WallThe Empire of the AntsA Vision of JudgmentThe Land IroncladsThe Beautiful SuitThe Pearl of LoveThe Country of the BlindThe ReconciliationMy First Aeroplane (Little Mother series #1)Little Mother Up the Mörderberg (Little Mother series #2)The Story of the Last TrumpThe Grisly Folk

Uncollected Stories

A Tale of the Twentieth Century: For Advanced ThinkersWalcoteThe Devotee of ArtThe Man with a NoseA Perfect Gentleman on WheelsWayde's EssenceA Misunderstood ArtistLe Mari TerribleThe Rajah's TreasureThe Presence by the FireMr Marshall's DoppelgangerThe Thing in No. 7The ThumbmarkA Family ElopementOur Little NeighbourHow Gabriel Became ThompsonHow Pingwill Was RoutedThe Loyalty of Esau Common: A FragmentThe Wild Asses of the DevilAnswer to PrayerThe Queer Story of Brownlow's NewspaperThe Country of the Blind (revised version)

Non-Fiction:

Text-Book of Biology (1893)[with R. A. Gregory] Honours Physiography (1893)Certain Personal Matters (1897)Anticipations of the Reactions of Mechanical and Scientific Progress upon Human Life and Thought (1901)Mankind in the Making (1903)The Future in America (1906)This Misery of Boots (1907)Will Socialism Destroy the Home? (1907)New Worlds for Old (1908)First and Last Things (1908)Floor Games (1911)The Great State (1912)Thoughts From H. G. Wells (1912)Little Wars (1913)The War That Will End War (1914)An Englishman Looks at the World (1914)The War and Socialism (1915)The Peace of the World (1915)What is Coming? (1916)[as 'D. P.] The Elements of Reconstruction (1916)God the Invisible King (1917)The Invisible Man / The Secret Places of the Heart / God the Invisible King. 1897, 1922 & 1917. H. G. Wells Collection. London: Odhams Press Limited, [1930].War and the Future (1917)Introduction to Nocturne (1917)In the Fourth Year (1918)[with Viscount Edward Grey, Lionel Curtis, William Archer, H. Wickham Steed, A. E. Zimmern, J. A. Spender, Viscount Bryce & Gilbert Murray] The Idea of a League of Nations (1919)The Outline of History (1920)Russia in the Shadows (1920)[with Arnold Bennett & Grant Overton] Frank Swinnerton (1920)The Salvaging of Civilization (1921)A Short History of the World (1922)A Short History of the World. 1922. Rev. ed. A Pelican Book. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1938.Washington and the Hope of Peace (1922)Socialism and the Scientific Motive (1923)The Story of a Great Schoolmaster: Being a Plain Account of the Life and Ideas of Sanderson of Oundle (1924)A Year of Prophesying (1925)A Short History of Mankind (1925)Mr. Belloc Objects to "The Outline of History" (1926)Wells' Social Anticipations (1927)The Way the World is Going (1928)The Book of Catherine Wells (1928)The Open Conspiracy (1928)[with Julian S. Huxley & G. P. Wells] The Science of Life (1930)Divorce as I See It (1930)Points of View (1930)The Work, Wealth and Happiness of Mankind (1931)The New Russia (1931)Selections From the Early Prose Works of H. G. Wells (1931)What Should be Done — Now: A Memorandum on the World Situation (1932)After Democracy (1932)[with J. V. Stalin] Marxism vs Liberalism (1934)Experiment in Autobiography (1934)Experiment in Autobiography: Discoveries and Conclusions of a Very Ordinary Brain (Since 1886). 1934. 2 vols. Jonathan Cape Paperback JCP 64-65. London: Jonathan Cape Ltd., 1969.The New America: The New World (1935)The Anatomy of Frustration (1936)World Brain (1938)The Fate of Homo Sapiens (1939)The New World Order (1939)Travels of a Republican Radical in Search of Hot Water (1939)The Common Sense of War and Peace (1940)The Rights of Man (1940)The Pocket History of the World (1941)Guide to the New World (1941)The Outlook for Homo Sapiens (1942)The Conquest of Time (1942)[with Lev Uspensky] Modern Russian and English Revolutionaries (1942)Phoenix: A Summary of the Inescapable Conditions of World Reorganization (1942)Crux Ansata: An Indictment of the Roman Catholic Church (1943)'42 to '44: A Contemporary Memoir (1944)[with J. B. S. Haldane & Julian S. Huxley] Reshaping Man's Heritage (1944)The Happy Turning (1945)Mind at the End of Its Tether (1945)Early Writings in Science and Science Fiction (1975)

Secondary:

Bergonzi, Bernard. The Early H. G. Wells: A Study of the Scientific Romances. Manchester, 1961.Dickson, Lovat. H. G. Wells: His Turbulent Life and Times. 1969. London: Readers Union Limited / Macmillan and Company Limited, 1971.Ray, Gordon N. H. G. Wells & Rebecca West. 1974. London: Macmillan London Limited, 1974.West, Anthony. H. G. Wells: Aspects of a Life. 1984. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985.

•

Anthony West: H. G. Wells: Aspects of a Life (1984)

Published on January 06, 2021 11:53

January 1, 2021

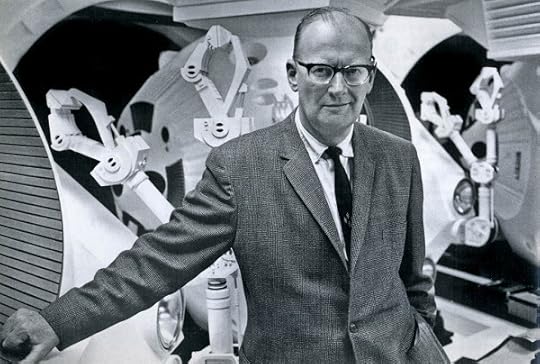

SF Luminaries: Arthur C. Clarke

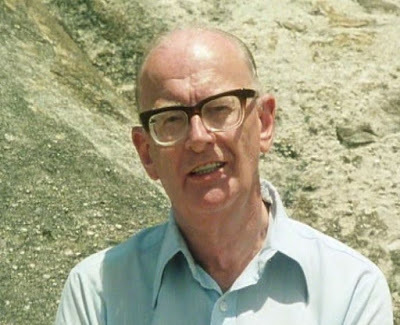

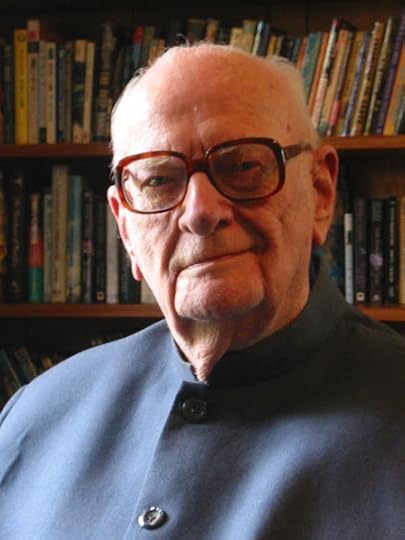

Arthur C. Clarke (1965)

I wonder if this preamble is as familiar to you as it is to me?

Arthur C. Clarke's Mysterious World (1980)

... Mysteries from the files of Arthur C. Clarke, author of 2001 and inventor of the communications satellite. Now in retreat in Sri Lanka, he ponders the mysteries of this and other worlds.

Bookwig: Arthur C. Clarke's Mysterious World (1980)

There are a number of interesting leads in there. What better way to usher in this long-awaited new year, 2021, than by unpacking a few of them?

•

The Utah Monolith (2016-20)

"author of 2001"

The Utah monolith is a metal pillar that stood in a red sandstone slot canyon in northern San Juan County, Utah. ... It was unlawfully placed on public land between July and October 2016, and stood unnoticed for over 4 years until its discovery and removal in late 2020. The identity of its makers, and their objectives, are unknown.

In the weeks after the discovery of the Utah pillar, dozens of similar metal columns were erected in other places throughout the world, including elsewhere in North America and various countries in Europe and South America. Many were built by local artists as deliberate imitations of the Utah monolith.

- Wikipedia

The Gingerbread Monolith (25/12/20)

The culmination of all these efforts was undoubtedly the Gingerbread monolith which appeared in a San Francisco park on Christmas Day, 2020.

When asked if he would be removing it, Phil Ginsburg, the San Francisco Recreation and Parks Department general manager, said that he had no such plans, "as it seemed to bring some joy and amusement to the community":

“Looks like a great spot to get baked. We will leave it up until the cookie crumbles ... We all deserve a little bit of magic right now.”

Joe Fitzgerald: "the cookie has crumbled" (27/12/20)

It's pretty good going if a reference to the central image of a film first released in 1968 makes immediate sense to people fifty years later. The famous black monolith from Kubrick & Clarke's 2001: A Space Odyssey was, of course, rectangular rather than triangular in form, but it's nice to know that it can still evoke such awe and perplexity after all this time.

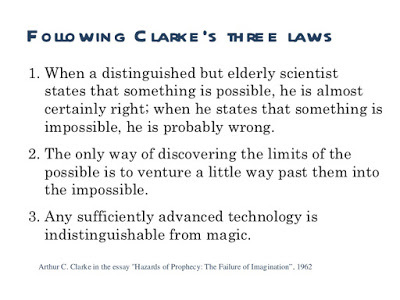

Redbubble: Earth Monolith Greeting Card

It's harder to guess if the other, more subtle reference embedded in Phil Ginsburg's remark is intentional or not: "We all deserve a little bit of magic right now." It seems like a reference to Clarke's third law (discussed in more detail in my earlier post on his friend and rival Isaac Asimov) but perhaps I'm overreading it.

But then again, given the fact that the aptly named Ginsburg (albeit with a 'u' rather than an 'e') is an official of America's hippest city, San Francisco, maybe not.

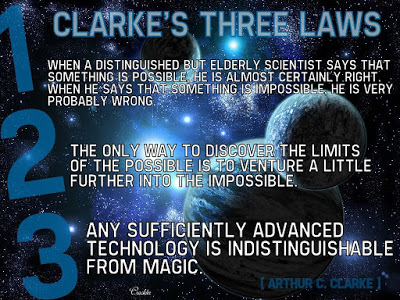

Clarke's Three Laws

•

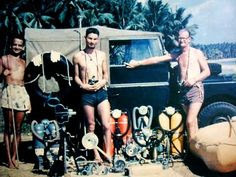

Peter Menzel: Arthur C. Clarke scuba-diving (2000)

"in retreat in Sri Lanka"

For many years the official reason given for Clarke's 1956 shift from the UK to Sri Lanka's tropical shores was his passion for scuba-diving, which was indeed the subject of a great many of his later books (cf. the selected bibliography at the end of this post).

Arthur C. Clarke: The Treasure of the Great Reef (1964)

It seems, in retrospect, very sad that his homosexuality had to remain a secret for so long - though it's hardly suprising, given Britain's archaic laws on the subject. Male homosexuality wasn't actually decriminalised until the Sexual Offences Act of 1967. Nor was that the end of the matter. In his 2017 Guardian article on the subject, Peter Tatchell explains:

The 1967 legislation repealed the maximum penalty of life imprisonment for anal sex. But it still discriminated. The age of consent was set at 21 for sex between men, compared with 16 for sex between men and women; a decision that pandered to the homophobic notion that young men are seduced and corrupted by older men. The punishment for a man over 21 having non-anal sex with a man aged 16-21 was increased from two to five years.Small wonder that so many British writers and artists sought refuge elsewhere in the world. Clarke never did 'come out' precisely - but he made increasingly little secret of his sexuality in his later years.

Until the scandal of his aborted knighthood, that is.

In 1998, the Sunday Mirror reported that he paid Sri Lankan boys for sex, leading to the cancellation of plans for Prince Charles to knight him on a visit to the country. The accusation was subsequently found to be baseless by the Sri Lankan police and was retracted by the newspaper. Journalists who enquired of Clarke whether he was gay were told, "No, merely mildly cheerful."Clarke was knighted for services to literature two years later, in 2000.

- Wikipedia

Leslie Ekanayake & Arthur C. Clarke

Arthur C. Clarke died in 2008. He is buried in Sri Lanka beside Leslie Ekanayake, whom he called his "only perfect friend of a lifetime" in the dedication to his only novel to be set on the island, The Fountains of Paradise (1979).

Arthur C. Clarke & Leslie Ekanayake

In one of his three "posthumous poems," printed for the first time in his Collected Poems (1977), W. H. Auden remarked:

When one is lonely (and You

My Dearest, know why,

as I know why it must be),

steps can be taken, even

a call-boy can help.

- W. H. Auden, 'Minnelied' (c.1967)

W. H. Auden & Chester Kallman (Venice, 1950s)

Clarke's partner, Leslie Ekanayake, died young, in 1977, at the age of thirty (he was killed in a motorcyle accident); Auden's, Chester Kallman, outlived the poet by two years, but had a tumultuous private life which definitely precluded monogamy.

Christopher Isherwood & W. H. Auden (1938)

Auden's own escape from the homophobia of his native England went back as far as the 1920s, though, when he and his friend Christopher Isherwood chose to move to the more tolerant atmosphere of pre-Nazi Berlin.

So why did Clarke continue to keep his sexuality a secret? No doubt he knew that he would probably not have had access to so many circles of scientific and political influence if the fact had been revealed publicly. On the other hand, as Michael Moorcock recalled:

Everyone knew he was gay. In the 1950s, I'd go out drinking with his boyfriend. We met his protégés, western and eastern, and their families, people who had only the most generous praise for his kindness. Self-absorbed he might be and a teetotaller, but an impeccable gent through and through."Everyone knew" - but they didn't have to know it officially. Auden and Isherwood were (latterly, at least) far more upfront about their sexuality, but I don't really think it's a subject anyone else not under the same pressure can offer a meaningful opinion on - given the obvious consequences of such an admission at the time.

Rohan de Silva: Clarke on Hikkaduwa beach (2009)

•

Steven Spielberg, dir. Close Encounters of the Three Kinds (1977)

"the mysteries of this and other worlds"

In his TV series Arthur C. Clarke's Mysterious World, Clarke defines the following three types of mystery:

I guess the most memorable thing about the series - and its two successors, Arthur C. Clarke’s World of Strange Powers (1985) and Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious Universe (1994) - is the scoffing incredulity with which the hard-headed Clarke, with his clipped, Somerset accent, shot down each new 'mystery' in its tracks.

Mysteries of the First Kind: Something that was once utterly baffling but is now completely understood, e.g. a rainbow.Mysteries of the Second Kind: Something that is currently not fully understood and can be in the future.Mysteries of the Third Kind: Something of which we have no understanding.

The Goodies: Big Foot (1982)

Perhaps, in fact, the only real reason to remember those goofy British comedians the Goodies is because of their brilliant parody of Clarke in the "Big Foot" episode of their eponymous TV show. A yeti can be clearly seen on coming in and out of shot as Clarke is seen pontificating in the foreground, declaring the complete lack of any evidence for its existence. "Vewy, vewy wisible", as another group of contemporary comedians were wont to say.

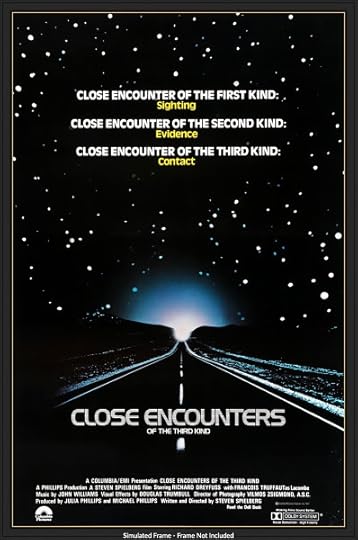

Newgrange, Ireland (1977)

The series as a whole exercised a strange fascination over me and my contemporaries. The main reason I felt compelled to visit the 5,000-year-old Newgrange tomb in Ireland in the late 1980s was as a result of having seen those haunting pictures of the light breaking into its dusty interior at Winter solstice dawn in Episode 8: "The Riddle of the Stones". It did not disappoint.

Winter Solstice, Newgrange

There were strange stories of poltergeists, lake monsters, missing apemen, and - perhaps best of all - Episode 7: "The Great Siberian Explosion", about the then-not-so-well-known Tunguska event of 1908. A great deal of original footage from the the 1930 Kulik expedition to the site was assembled very usefully here, which makes it, still, one of the best accounts of this particularly weird occurrence to date.

The Tunguska Explosion (1908)

In retrospect, it must have been the sheer wet blanket effect of his relentless scepticism which made the series so memorable. If it can get past him, we were more-or-less subtly conditioned to think, there really must be something in it. The fact that one or two of the mysteries stumped even Clarke seemed a powerful argument for their possible validity.

Arthur C. Clarke's Mysterious World (1980)

•

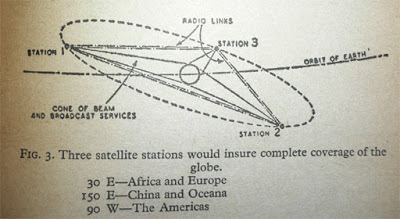

Arthur C. Clarke: "Extraterrestrial relays" (Wireless World, 1945)

"inventor of the communications satellite"

Really? If you ask the question online, you'll soon discover that some doubt has been thrown on this assertion in recent years:

He wasn't the original source for the idea/actual inventor of the concept but starting with the article [above] ... he was a big proponent of the uses you could put geostationary satellites to. ...

The idea for geostationary satellites originally was published by Herman Potočnik in 1928 in his book Das Problem der Befahrung des Weltraums - der Raketen-Motor (The Problem of Space Travel - The Rocket Motor):A partial translation to English, containing most of the essential chapters, was made as early as 1929 for the American magazine Science Wonder Stories and was issued in three parts (July, August and September 1929) and credited to "Captain Hermann Noordung, A.D., M.E., Berlin." The article was also published in Science Wonder Stories' sister publication Air Wonder Stories at the same time.However, Wikipedia's article on Potočnik states the idea was "first put forward by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky."

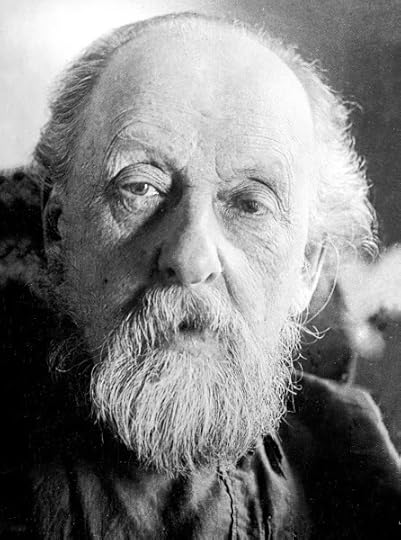

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (1857-1935)

Despite these quibbles, the Wikipedia "Communications satellite" article continues to accord Clarke the distinction:

The concept of the geostationary communications satellite was first proposed by Arthur C. Clarke, along with Vahid K. Sanadi building on work by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. In October 1945, Clarke published an article titled "Extraterrestrial Relays" in the British magazine Wireless World. The article described the fundamentals behind the deployment of artificial satellites in geostationary orbits for the purpose of relaying radio signals. Thus, Arthur C. Clarke is often quoted as being the inventor of the communications satellite and the term 'Clarke Belt' employed as a description of the orbit.I guess the reason for belabouring the point is that there certainly was a fair measure of bigheadedness about Clarke. His later books, in particular, are full of skiting about various distinctions he's earned, asteroids he's had named after him, important people he's met ... It's hard to know, in a contest for greatest Sci-fi / Pop Science Gasbag, whether he or Asimov would gain the prize: let's call it a tie.

Unfortunately this fact can lead one to dismiss his actual importance and influence on many fields. Inventor of the Communications Satellite may be a bit of a stretch, but not by much. The problem, really, was that, like his predecessor H. G. Wells, he outlived his vogue - and the works of his maturity - by a number of decades.

Arthur C. Clarke: Selected titles

It's his early work that will endure - those brilliantly exciting, yet still scientifically plausible thrillers such as A Fall of Moondust or Rendezvous with Rama; those breathtakingly imaginative fantasies such as The City and the Stars or Childhood's End. His short stories, too, taken as a whole, combine the best slambang features of the pulp era with the more urbane prose of contemporaries such as John Wyndham or C. S. Lewis.

Arthur C. Clarke: The View from Serendip (1977)

Of the 'Big Three', it may actually be Clarke's works which will last best. The "View from Serendip" - the name of one of his many collections of reflective essays - seems to have served him well. British by birth, his intimate involvement with his place of residence, Sri Lanka, made his viewpoint not quite that of a Westerner - and the difference shows.

Perhaps I'm just sentimental, but the many happy hours I've spent reading and rereading his books makes me want to send him good thoughts wherever he may be now.

Tod Mesirow: Arthur C. Clarke (1995)

•

Arthur C. Clarke: Astounding Days (1989)

Sir Arthur Charles Clarke

(1917-2008)

Series:

A Space Odyssey:2001: A Space Odyssey: A Novel. Based on the Screenplay by Arthur C. Clarke & Stanley Kubrick. 1968 (London: Arrow Books Ltd., 1974)2010: Odyssey Two. 1982 (London: Granada Publishing Ltd., 1983)2061: Odyssey Three. 1987. Voyager (London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1997)3001: The Final Odyssey. 1997. Voyager (London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1997)

Rama:Rendezvous with Rama. 1972 (London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1973)[with Gentry Lee] Rama: The Omnibus. The Complete Rama Story. Rendezvous with Rama; Rama II; The Garden of Rama; Rama Revealed. 1972, 1989, 1991, 1993. Gollancz (London: Orion Publishing Group, 1973)

A Time Odyssey:[with Stephen Baxter] Time's Eye (2003)[with Stephen Baxter] Sunstorm (2005)[with Stephen Baxter] Firstborn (2007)

Other Novels:

The Lion of Comarre & Against the Fall of Night. 1948, 1953, 1968. Corgi SF Collector’s Library (London: Transworld Publishers Ltd., 1975)Prelude to Space [aka Master of Space & The Space Dreamers]. 1951 (London: Pan Books, 1954)The Sands of Mars. 1951. Sphere Science Fiction Classics (London: Sphere Books Limited, 1972)Islands in the Sky. 1952. Introduction by Patrick Moore. Puffin Books (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1973)Childhood's End. 1953. Pan Science Fiction (London: Pan Books, 1973)Earthlight. 1955. Pan Science Fiction (London: Pan Books, 1973)The City and the Stars. 1956. Corgi SF Collector’s Library (London: Transworld Publishers Ltd., 1975)The Deep Range. 1957. Pan Science Fiction (London: Pan Books, 1973)A Fall of Moondust. 1961. Pan Books (London: Pan Books, 1971)Dolphin Island: A Story of the People of the Sea. 1963. Illustrated by Robin Andersen. Piccolo Science Fiction (London: Pan Books, 1976)Glide Path. 1963 (London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1980)Imperial Earth: A Fantasy of Love and Discord. 1975 (London: Pan Books, 1977)The Fountains of Paradise. 1979 (London: Pan Books, 1980)The Songs of Distant Earth. 1986. Grafton Books (London: Collins, 1987)[with Gentry Lee] Cradle (1988)[with Gregory Benford] Beyond the Fall of Night (1990)The Ghost from the Grand Banks (1990)The Hammer of God (1993)[with Mike McQuay] Richter 10 (1996)[with Michael P. Kube-McDowell] The Trigger (1999)[with Stephen Baxter] The Light of Other Days (2000)[with Frederik Pohl] The Last Theorem (2008)

Stories:

Expedition to Earth. 1953 (London: Sphere Books, 1968)Reach for Tomorrow (New York: Ballantine Books, 1956)Venture to the Moon (1956)Tales from the White Hart. 1957 (London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1973)The Other Side of the Sky. 1958. Corgi SF Collector’s Library (London: Transworld Publishers Ltd., 1974)Tales of Ten Worlds. 1962. Corgi Books (London: Transworld Publishers Ltd., 1971)The Nine Billion Names of God (1967)Of Time and Stars (1972)The Wind from the Sun: Stories of the Space Age. 1972. A Signet Book. New American Library, 1973)The Lost Worlds of 2001 (London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1972)The Best of Arthur C. Clarke 1937-1971 (London: Sphere Books Limited, 1973)The Best of Arthur C. Clarke 1937-1955 (1976)The Best of Arthur C. Clarke 1956-1972 (1977)The Sentinel (1983)Tales From Planet Earth (1990)More Than One Universe (1991)The Collected Stories of Arthur C. Clarke. 2000. Gollancz (London: Orion Publishing Group, 2001)

Non-fiction:

Interplanetary Flight: An Introduction to Astronautics (1950)The Exploration of Space. 1951. Rev ed. 1959. A Premier Book (Greenwich, Conn.: Fawcett Publications, Inc., 1960)The Exploration of the Moon. Illustrated by R.A. Smith (1954)The Young Traveller in Space [aka Going Into Space & The Scottie Book of Space Travel]. 1954 (1957)The Coast of Coral. Photos by Mike Wilson. Text by Arthur C. Clarke. Blue Planet Trilogy 1 (1956)The Reefs of Taprobane: Underwater Adventures around Ceylon. Photos by Mike Wilson. Text by Arthur C. Clarke. Blue Planet Trilogy 2 (1957)The Making of a Moon: The Story of the Earth Satellite Program (1957)Boy Beneath the Sea. Photos by Mike Wilson. Text by Arthur C. Clarke (1958)Voice Across the Sea (1958)The Challenge of the Space Ship: Previews of Tomorrow’s World. 1959. New York: Ballantine Books, 1961.The Challenge of the Sea (1960)The First Five Fathoms. Photos by Mike Wilson. Text by Arthur C. Clarke (1960)Indian Ocean Adventure. Photos by Mike Wilson. Text by Arthur C. Clarke (1961)Profiles of the Future: an Inquiry into the Limits of the Possible. 1962. Rev. ed. 1973 (London: Pan Books, 1976)[with the editors of Life] Man and Space (1964)Indian Ocean Treasure. Photos by Mike Wilson. Text by Arthur C. Clarke (1964)The Treasure of the Great Reef. Photos by Mike Wilson. Text by Arthur C. Clarke. Blue Planet Trilogy 3 (1964)Voices from the Sky: Previews of the Coming Space Age. 1966. London: Mayflower Books Ltd., 1969.The Promise of Space (1968)[with Robert Silverberg] Into Space: a Young Person’s Guide to Space (1971)Beyond Jupiter: The Worlds of Tomorrow. Paintings by Chesley Bonestell. Text by Arthur C. Clarke (1972)Report on Planet Three and Other Speculations. 1972. Corgi SF Collector’s Library (London: Transworld Publishers Ltd., 1973)The View from Serendip. 1977 (London: Pan Books, 1979)[with Peter Hyams] The Odyssey File. 1984. Panther Books (London: Granada Publishing Ltd., 1985)1984, Spring: A Choice of Futures (1984)Ascent to Orbit, A Scientific Autobiography: The Technical Writings of Arthur C. Clarke (1984)20 July 2019: Life in the 21st Century (1986)Astounding Days: A Science Fictional Autobiography (London: Victor Gollancz, 1989)How the World Was One: Beyond the Global Village [aka How the World Was One: Towards the Tele-Family of Man] (1992)By Space Possessed (1993)The Snows of Olympus - A Garden on Mars (1994)Childhood Ends: The Earliest Writings of Arthur C. Clarke (1996)Greetings, Carbon-Based Bipeds!: Collected Works 1934–1988 (1999)

Edited & Introduced:

[Ed.] Time Probe: The Sciences in Science Fiction (1966)[Ed.] The Coming of the Space Age: Famous Accounts of Man's Probing of the Universe (1967)[Foreword] John Fairley & Simon Welfare. Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World. 1980 (London: Collins, 1986)[Ed., with George Proctor] The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume Three: The Nebula Winners 1965–1969 (1982)[Foreword] John Fairley & Simon Welfare. Arthur C. Clarke’s World of Strange Powers. 1984 (London: Collins, 1990)[Foreword] John Fairley & Simon Welfare. Arthur C. Clarke’s Chronicles of the Strange & Mysterious (London: Guild Publishing, 1987)[Afterword] Paul Preuss. Arthur C. Clarke's Venus Prime, Vol. 1: Breaking Strain (1987)[Afterword] Paul Preuss. Arthur C. Clarke's Venus Prime, Vol. 2: Maelstrom (1988)[Afterword] Paul Preuss. Arthur C. Clarke's Venus Prime, Vol. 3: Hide and Seek (1989)[Afterword] Paul Preuss. Arthur C. Clarke's Venus Prime, Vol. 4: The Medusa Encounter (1990)[Afterword] Paul Preuss. Arthur C. Clarke's Venus Prime, Vol. 5: The Diamond Moon (1990)[Ed.] Project Solar Sail (1990)[Afterword] Paul Preuss. Arthur C. Clarke's Venus Prime, Vol. 6: The Shining Ones (1991)[Foreword] John Fairley & Simon Welfare. Arthur C. Clarke’s A-Z of Mysteries: From Atlantis to Zombies. Foreword by Arthur C. Clarke (London: Book Club Associates, 1993)[Introduction] Gentry Lee. Bright Messengers (1995)[Introduction] James Randi. An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural [aka The Supernatural A-Z: The Truth and the Lies] (1995)[Tribute] Isaac Asimov. The Roving Mind: New Edition (1997)Keith Allen Daniels, ed. Arthur C. Clarke & Lord Dunsany: A Correspondence (1998)[Foreword] David G. Stork. Hal's Legacy: 2001's Computer As Dream and Reality (1998)[Foreword] Simon Welfare and John Fairley. Arthur C. Clarke's Mysteries (1998)[Foreword] Victoria Brooks, ed. Literary Trips 2: Following in the Footsteps of Fame (2001)[Foreword] Dan Richter. Moonwatcher's Memoir: A Diary of 2001: A Space Odyssey (2002)Ryder W. Miller, ed. From Narnia to A Space Odyssey: The War of Ideas Between Arthur C. Clarke and C. S. Lewis (2003)[Preface] Anthony Frewin, ed. Are We Alone?: The Stanley Kubrick Extraterrestrial Intelligence Interviews (2005)[Foreword] Dr. Gary Westfahl, ed. Science Fiction Quotations: From the Inner Mind to the Outer Limits (2005)

Cinema & TV:

2001: A Space Odyssey, dir. Stanley Kubrick, writ. Arthur C. Clarke & Stanley Kubrick (based on 'The Sentinel' by Arthur C. Clarke) - with Keir Dullea, Gary Lockwood - (UK/USA, 1968)2010: The Year We Make Contact, dir. & writ. Peter Hyams (based on the novel by Arthur C. Clarke) - with Roy Scheider, John Lithgow, Helen Mirren, Bob Balaban, Keir Dullea - (USA, 1984)Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World, narrated by Gordon Honeycombe, prod. John Fanshawe & John Fairley, dir. Peter Jones, Michael Weigall & Charles Flynn (UK, 1980). 2-DVD set.Arthur C. Clarke’s World of Strange Powers, narrated by Anna Ford, prod. John Fairley, dir. Peter Jones, Michael Weigall & Charles Flynn (UK, 1985). 2-DVD set.Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious Universe, narrated by Carol Vorderman, prod. John Fairley, dir. Peter Jones, Michael Weigall & Charles Flynn (UK, 1994). 4-DVD set.

•

Arthur C. Clarke: The Collected Stories (2001)

Published on January 01, 2021 11:19

December 25, 2020

SF Luminaries: Mary Shelley

Richard Rothwell: Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (1840)

"I write bad articles which help to make me miserable — but I am going to plunge into a novel and hope that its clear water will wash off the mud of the magazines." - Mary Shelley, Letter to Leigh Hunt

Theodor von Holst: Frontispiece to Frankenstein (1831)

There's a section in an 2016 post of mine entitled "Movies about Writers" which includes some remarks on a subgenre I've called "Byron-'n'-Shelley-'n'-Mary-Shelley" films: ones which concentrate on the infamous "haunted summer" of 1816, which she and her husband Percy spent mostly on the shores of Lake Geneva, hob-nobbing with Lord Byron and his hapless companion Dr. Polidori.

Kenneth Branagh, dir.: Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (1994)

This is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to charting the influence of that rather disturbing meeting of minds on popular culture: fiction as well as cinema. I mentioned there Brian Aldiss's SF novel Frankenstein Unbound (1973), Liz Lochead's Dreaming Frankenstein (1984), and Tim Powers' The Stress of Her Regard (1989). (I might also have added Christopher Priest's The Prestige (1995) - though this is far more notable in the novel than in Christopher Nolan's 2006 film version).

Michael Sims: Frankenstein Dreams: A Connoisseur’s Collection of Victorian Science Fiction (2017)

There's also (now) Peter Ackroyd's The Casebook of Victor Frankenstein (2009) to be considered, along with Stephanie Hemphill's Hideous Love (2013) and Jon Skovron's Man Made Boy (2015). Michael Sims, editor of Frankenstein Dreams: A Connoisseur’s Collection of Victorian Science Fiction (2017), mentions these and various other titles in his own 2018 article "8 Books that wouldn't exist without Mary Shelley's Frankenstein".

Leslie S. Klinger, ed.: The New Annotated Frankenstein (2017)

When it comes to movies and TV shows based on the book, it's hard to know exactly where to begin. There's a reasonably complete filmography in Leslie S. Klinger's New Annotated Frankenstein, which takes you all the way from James Whale's classic Frankenstein (1931) and its sequel Bride of Frankenstein (1935) to that curious film Gods and Monsters (1998), which purports to recreate Whale's own last days.

The Frankenstein Chronicles (2015-17)

On the small screen, as well as two series of the UK TV series The Frankenstein Chronicles, there have been three series of that strange amalgam of Dracula, Frankenstein, and The Portrait of Dorian Gray, John Logan's Penny Dreadful ...

Penny Dreadful (2014-16)

All of which brings us to the crucial question: what exactly is Frankenstein? I don't mean that perennial confusion about who the title actually refers to: Victor Frankenstein or Frankenstein's monster (the former, of course). I mean, what kind of a book is it?

Peter Fairclough, ed. Three Gothic Novels (1983)

Mario Praz, author of The Romantic Agony (1933), who contributed an introduction to the edition above, is in no doubt. It's a Gothic novel, and offers all of the seductive attributes of that genre. As the article on on Wikipedia so succinctly puts it:

Gothic fiction tends to place emphasis on both emotion and a pleasurable kind of terror, serving as an extension of the Romantic literary movement ... The most common of these "pleasures" among Gothic readers was the sublime — an indescribable feeling that "takes us beyond ourselves.""The genre had much success in the 19th century," the article goes on to say, "as witnessed in prose by Mary Shelley's Frankenstein [my emphasis] and the works of E. T. A. Hoffmann and Edgar Allan Poe ... and in poetry in the work of Samuel Taylor Coleridge."

The Collected Supernatural and Weird Fiction of Mary Shelley, Vol 1 (2010)

The collection above leaves no doubt what area of the literary firmament they see Mary Shelley as inhabiting: the supernatural and weird.

The Collected Supernatural and Weird Fiction of Mary Shelley, Vol 2 (2010)

But there is, of course, a dissentient vein of opinion on this point. It's hard to say who really started this particular hare, but it's certainly strongly associated with Brian Aldiss, a prolific SF author in his own right, and author of the 1973 history of the genre Billion Year Spree (updated in 1986 as Trillion Year Spree). In a speech made at the launch of a new edition of Frankenstein in 2008, he summarised his views as follows:

Brian Aldiss Billion Year Spree (1973)

... when I was attempting to write [Billion Year Spree], I had to begin at the beginning – as one does. At the same time, there were a lot of people who were very eager to find out who was the ‘Father’ of science fiction, and I was very happy to proclaim that Mary Shelley was the Mother of Science Fiction. It caused a lot of bad blood at the time, but happily it’s been spilt and mopped up now.

... In making this claim, which I took care to buttress with examples, I wanted not only to retrieve the book to current attention in a way that my readers might at first resent but would ultimately profit from, but also to retrieve it from the hands of Universal Studios’ horrific Boris Karloff, because I saw that it was so much more than a horror tale. It had mythic quality ...

The fantastical had been in vogue long before Shakespeare. It was eternally in vogue. Aristophanes’ The Birds creates a cloud cuckoo land between earth and heaven ... Then there’s Lucian of Samosata in the first century of our epoch, who describes how the King of the Sun and the King of the Moon go to war over the colonization of – can you guess? – the colonization of Jupiter ...

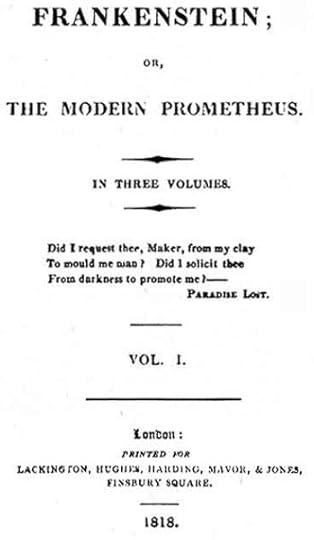

Christendom was full of angels and lots of fibs about the planets being inhabited. One’s knee deep in these discarded fantasies, but it was Mary Shelley, poised between the Enlightenment and Romanticism, who first wrote of life – that vital spark – being created not by divine intervention as hitherto, but by scientific means; by hard work and by research.

That was new, and in a sense it remains new. The difference is impressive, persuasive, permanent.

Mary Shelley: The Last Man (1826)

In a sense the whole argument comes down to The Last Man. This dystopian futuristic fantasy is the only other significant exhibit to consider when attempting to decide whether to weight the scales towards "Gothic novelist" or "Mother of Science Fiction" for Mary Shelley. Brian Aldiss, once again, is in no doubt:

As if to prove this unsuspected truth in the same way that a scientist doesn’t announce his discovery until he can repeat it, Mary later wrote another futurist novel, The Last Man.None of the rest of her seven novels shows any particular elements of speculative fiction: most of them are historical in inspiration, and the others (such as Mathilda, unpublished in her lifetime) tend to be more preoccupied with the complexities of sexual politics.

... [In it] we are asked, for instance: “What are we, the inhabitants of this globe, least amongst the many people that inhabit infinite space? Our minds embrace infinity. The visible mechanism of our being is subject to merest accident.”

Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849)

Jules Verne (1828-1905)

H. G. Wells (1866-1946)

Hugo Gernsback (1884-1967)

Science Fiction has certainly been gifted with quite a number of fathers: Edgar Allan Poe, Jules Verne, H. G. Wells, and Hugo Gernsback, to name just a few. I suppose that I would feel happier to embrace Brian Aldiss's hypothesis if it weren't for the hyper-Gothic tone of Frankenstein in both the 1818 and 1831 versions.

H. G. Wells: The Island of Dr Moreau (1896)

But then, the same could be said of Wells's Island of Doctor Moreau, or - for that matter - almost all of Poe's fictional output.

It it were just a matter of Frankenstein itself, I think I might still see it as a bit exaggerated - but The Last Man, direct ancestor of such novels as Richard Matheson's I am Legend (1954), George R. Stewart's Earth Abides (1949), Susan Ertz's Woman Alive (1935), and M. P. Shiel's The Purple Cloud (1901), does lend potent support to Aldiss's argument.

John Martin: The Last Man (1849)

Admittedly John Clute's magisterial Encyclopedia of Science Fiction complicates the issue somewhat by describing the complex backstory of the idea:

Early treatments, often in verse, include Jean-Baptiste Cousin de Grainville's The Last Man: or, Omegarus and Syderia: A Romance in Futurity (1805; trans 1806); Lord Byron's "Darkness" (1816); "The Last Man" (1823), a poem by Thomas Campbell (1777-1844) which inspired John Martin's mezzotint "The Last Man" (1826); The Last Man (1826), an operatic scena by William H Callcott (1807-1882); "The Last Man" (1826), a poem by Thomas Hood (1799-1845) ...All of these before even mentioning Mary Shelley's novel!

One thing's for certain, Frankenstein seems fated to remain one of those very few works of fiction which transcends the genre it was written in, which taps into some mythic layer of the collective unconscious. Dracula, Sherlock Holmes, Dr Jekyll and Mr. Hyde - they keep on being revised, revisited, reinvented in a constant cycle of desire. Whatever their authors envisaged for them, it's impossible they could have foreseen such a relentless need for this among all the other products of their pen.

Mary Shelley was undoubtedly a genius. Even given her extraordinary background: daughter of two brilliant and intellectually revolutionary parents, William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft; married to another genius, Percy Bysshe Shelley; no-one could really have predicted the heights of renown she would reach.

If SF has to have a single ancestor, why shouldn't it be Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley? The extent of her influence on the genre then and now certainly makes her well worthy of the honour.

Leonard Wolf, ed.: The Annotated Frankenstein (1977)

•

Reginald Easton: Mary Shelley (1857)

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley

(1797-1851)

Novels:

Frankenstein; Or, The Modern Prometheus. 3 vols. London: Printed for Lackington, Hughes, Harding, Mavor, & Jones, 1818.Three Gothic Novels: The Castle of Otranto, by Horace Walpole; Vathek, by William Beckford; Frankenstein, by Mary Shelley. 1764, 1786, & 1818. Ed. Peter Fairclough. Introduction by Mario Praz. 1968. Penguin English Library. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970.The Annotated Frankenstein. 1818. Ed. Leonard Wolf. Art by Marcia Huyette. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1977.The New Annotated Frankenstein: Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. 1818. Rev. ed. 1831. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger. Introduction by Guillermo del Toro. Afterword by Anne K. Mellor. Liveright Publishing Corporation. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. Inc., 2017.Making Humans: Mary Shelley, Frankenstein / H. G. Wells, The Island of Doctor Moreau: Complete Texts with Introduction. Historical Contexts. Critical Essays. 1818 & 1896. Ed. Judith Wilt. New Riverside Editions. Ed. Alan Richardson. Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.Valperga: Or, the Life and Adventures of Castruccio, Prince of Lucca. 3 vols. London: Printed for G. and W. B. Whittaker, 1823.The Last Man. 3 vols. London: Henry Colburn, 1826.The Last Man. 1826. Introduction by Brian Aldiss. Hogarth Fiction. London: the Hogarth Press, 1985.The Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck, A Romance. 3 vols. London: Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, 1830.Lodore. 3 vols. London: Richard Bentley, 1835.Falkner. A Novel. 3 vols. London: Saunders and Otley, 1837.Mathilda. 1819. Ed. Elizabeth Nitchie. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1959.

Travel narratives:

[with Percy Bysshe Shelley] History of a Six Weeks' Tour through a Part of France, Switzerland, Germany, and Holland: with Letters Descriptive of a Sail round the Lake of Geneva, and of the Glaciers of Chamouni. London: T. Hookham, Jun.; and C. and J. Ollier, 1817.Rambles in Germany and Italy, in 1840, 1842, and 1843. 2 vols. London: Edward Moxon, 1844.

Children's books:

[with Percy Bysshe Shelley] Proserpine & Midas. Two unpublished Mythological Dramas by Mary Shelley. 1820. Ed. A. H. Koszul. London: Humphrey Milford, 1922.Maurice, or The Fisher’s Cot. 1820. Ed. Claire Tomalin. 1998. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1999.

Journals & Letters:

The Journals of Mary Shelley, 1814–44. Ed. Paula R. Feldman and Diana Scott-Kilvert. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995.The Letters of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley. 3 vols. Ed. Betty T. Bennett. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980.

Secondary:

Holmes, Richard. Shelley: The Pursuit. 1974. London: Quartet Books, 1976.St Clair, William. The Godwins and the Shelleys: The Biography of a Family. 1989. London: Faber, 1990.Trelawny, Edward John. Records of Shelley, Byron, and the Author. 1878. Ed. David Wright. 1973. Penguin English Library. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1982.

•

Mary Shelley: Frankenstein (1818)

Published on December 25, 2020 13:02

December 18, 2020

SF Luminaries: Isaac Asimov

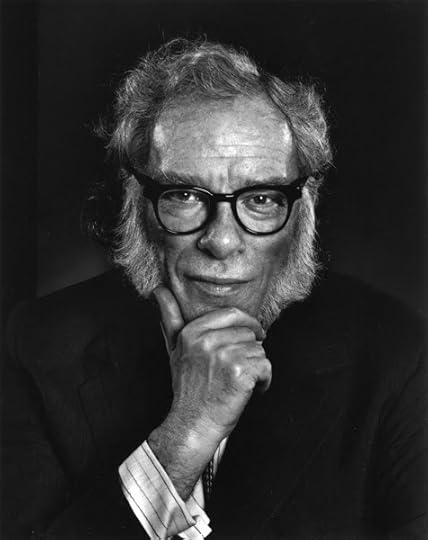

Yousuf Karsh: Isaac Asimov (1985)

So if Robert Heinlein was the 'Dean of Science-Fiction writers' and Arthur C. Clarke was the 'Colossus of Science Fiction', what - in the opinion of paperback blurb-writers, that is - was Dr. Isaac Asimov? He was, it would appear, the 'Grand Master of Science Fiction'.

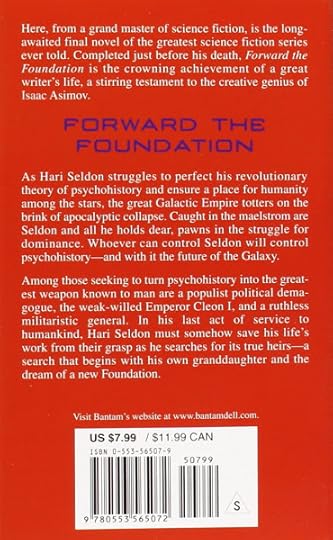

Isaac Asimov: Forward the Foundation (1994)

Whatever your views on this vital matter, it does seem worth mentioning, if only to introduce the subject of the (so-called) 'Big Three' of Science Fiction from the second half of the twentieth century. Clarke dedicated his 1972 book Report on Planet Three and Other Speculations as follows:

In accordance with the terms of the Clarke-Asimov treaty, the second-best science writer dedicates this book to the second-best science-fiction writer.To this Asimov riposted as follows:

Top 3 Asimov-Clarke Quotes

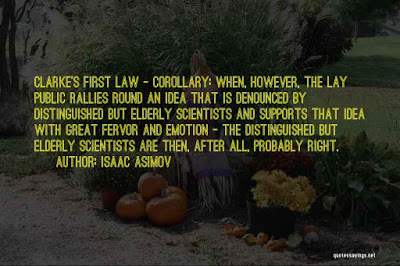

Then, of course, there are Clarke's three famous laws ("As three laws were enough for Newton, I have modestly decided to stop there"):

Clarke's Three Laws

To which the good doctor (Asimov was the only one with a PhD among the three of them, a distinction of which he took full advantage) replied:

Top 3 Asimov-Clarke Quotes

These rather infantile exchanges give you some idea of the level of much of the two writers' work. There's a cheap-smart cleverness to much of it which appeals to teenagers - it certainly did to me - but can wear off somewhat as one processes into middle age.

So what is there to be said for Isaac Asimov? His popular science writing; his historical surveys of this, that and the other (The Bible, American History, Byzantium and Ancient Rome, among many, many others); his joke-books and other ephemera have all lost currency with the passing years. The ongoing controversy about just how many books he had written (500-odd at final count); the 'why aren't you at home writing?' gag whenever anyone spotted him in a public place - all dust, all gone where their worm dieth not, and the fire is not quenched.

The answer, then, would have to depend on two things: Robots, and the Foundation Trilogy.

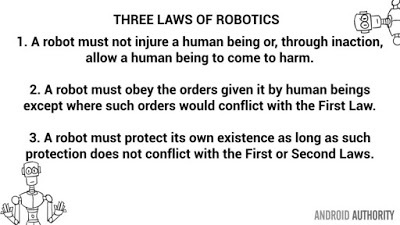

The first of these can be summed up in the following set of laws, formulated in 1942 - long before Clarke's - with the help of Astounding editor John W. Campbell:

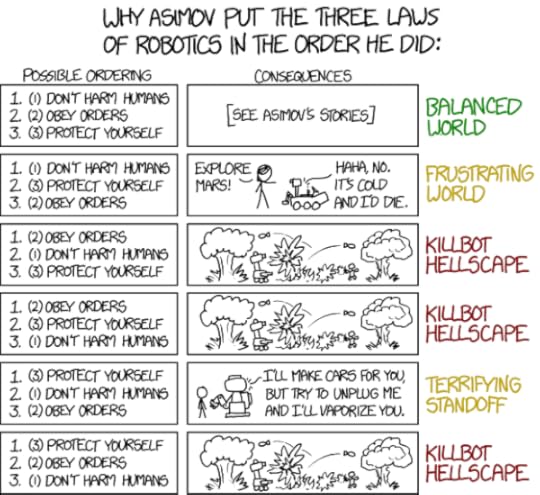

Android Authority

These may seem, at first sight, somewhat simplistic, but they proved fruitful territory for a long series of stories and novels over the next half-century. Here's one breakdown of their possible implications:

explain xkcd

And here's a list of the principal titles in the series:

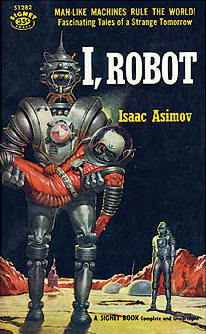

Isaac Asimov: I, Robot (1950)

short story collections:

I, Robot (1950)The Rest of the Robots (1964)The Complete Robot (1982)Robot Dreams (1986)Robot Visions (1990)

novels:

The Caves of Steel (1954)The Naked Sun (1957)The Robots of Dawn (1983)Robots and Empire (1985)

Alex Proyas, dir. : I, Robot (2004)

There's no denying the influence these stories have had on the whole field of SF. In fact, it's hard to consider the omnipresent 'android theme' at all without taking some position on Asimov's laws.

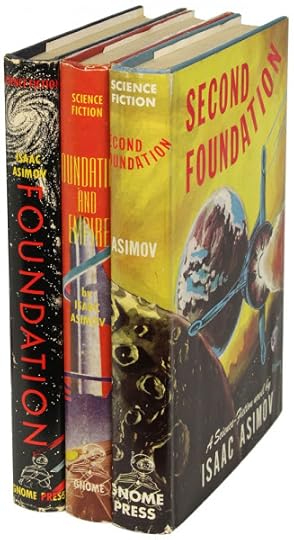

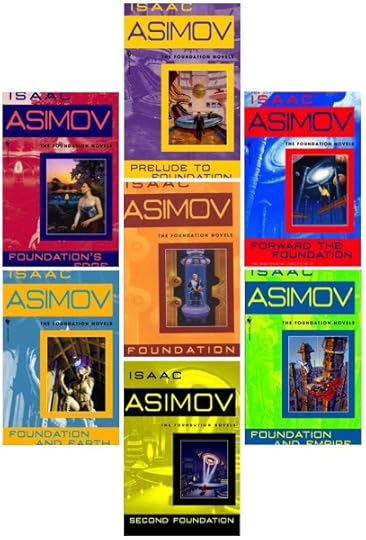

Isaac Asimov: The Foundation Series (1951-53)

However, before waxing too hyperbolic on the subject, it's important to backtrack a little:

In 1966, [Asimov's] Foundation trilogy beat several other science fiction and fantasy series to receive a special Hugo Award for "Best All-Time Series". The runners-up for the award were Barsoom series by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Future History series by Robert A. Heinlein, Lensman series by Edward E. Smith and The Lord of the Rings by J. R. R. Tolkien. - WikipediaMind you, if the vote had been held a few years later, it might well have gone to Frank Herbert's Dune series instead. Or not. Who knows? The point is that Foundation is not only the pinnacle of Asimov's work, but one of the most important sets of stories in SF history.

Isaac Asimov: The Foundation Series (1951-53)

Why? What is it about this series of stories (which first appeared in Campbell's Astounding in the late 1940s) which has given them such longevity? I mean, which of the other contenders for 'best all-time series' - with the exception of Tolkien's Lord of the Rings - can still be taken seriously at this late date?

It all comes down to Psychohistory. Psychohistory is an impossible idea, but it appealed strongly to readers then (and now). This imaginary science, invented by Asimov alter-ego Hari Selden, purports to be able to analyse long-term trends in society with sufficient accuracy to be able to foresee the future.

Isaac Asimov: The Foundation Series (Folio Society, 2016)

At first all goes swimmingly - the rise of the Foundation on the planet Terminus, the fight with the dying Empire, internal squabbles - until the advent of the Mule, a telepathic mutant who manages to upset the apple-cart (almost) entirely.

If you want a plot summary, you'll find a number of them online - or better still, you might feel inspired to read the series yourself. The point is that it was fascinating: not in spite of its pseudo-scientific trappings but because of them. Asimov always had a smooth way with a yarn, but here he outdid himself, wrapping conundrum within conundrum, mystery within mystery.

Isaac Asimov: Foundation's Edge (1982)

Then, some thirty years after publishing the last story in the series, Asimov decided to go back to it. The result, eventually, was two new sequels and two prequels to the original trilogy. These have elicited mixed opinions. Foundation's Edge itself is extremely readable, and certainly equal in merit to Second Foundation. Can the same be said of all the others? Probably not.

They are all interesting, but hardly necessary for the appreciation of the original series. In many ways their main purpose appears to be to accomplish a link-up with Asimov's similarly extended 'Robot' series into a connected history of the cosmos from the near to the far future.

In any case, here they all are, arranged in chronological order for your convenience:

Isaac Asimov: Foundation Series (cover art by Chris Foss, 1976)

Foundation prequels:

Prelude to Foundation (1988)Forward the Foundation (1993)

Original Foundation trilogy:

Foundation (1951)Foundation and Empire (1952)Second Foundation (1953)

Extended Foundation series:

Foundation's Edge (1982)Foundation and Earth (1986)

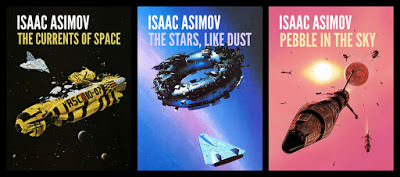

Isaac Asimov: Galactic Empire Series (1951-93)

Galactic Empire series:

The Currents of Space (1952)The Stars, Like Dust (1951)Pebble in the Sky (1950)

In between the 'Robot' and the 'Foundation' series come the 'Galactic Empire' novels. These, though entertaining enough, lack the unity of the other two series, but do - in theory at least - bridge part of the gap between them.

What else? Short stories! Tons and tons of short stories, as befits one of those hardy pioneers who spanned the pulp and the hardback era. These are far too many to discuss in detail, though they do include 'Nightfall', which continues to be routinely included on lists of most important or influential SF stories.

The Early Asimov or, Eleven Years of Trying (1972)

What's most notable about them (imho) is the gradual way in which they morph from the hard Science Fiction of his beginnings into the mystery genre. Not being a great connoisseur of detective stories, it's difficult for me to judge his prowess in this form, but they do, collectively, seem to me to represent a bit of a come-down from his earlier work.

It is, however, arguable that Asimov never wrote anything but mysteries - whether set in the future or the present, fairyland or space. Here, in any case, is a list of his main publications in the field, including two novels and the extensive 'Black Widowers' series:

Isaac Asimov: Murder at the ABA (1976)

Novels:

The Death Dealers (1958)Murder at the ABA (1976)

Short stories:

Asimov's Mysteries (1968)Tales of the Black Widowers (1974)More Tales of the Black Widowers (1976)The Key Word and Other Mysteries (1977)Casebook of the Black Widowers (1980)The Union Club Mysteries (1983)Banquets of the Black Widowers (1984)The Disappearing Man and Other Mysteries (1985)The Best Mysteries of Isaac Asimov (1986)Puzzles of the Black Widowers (1990)The Return of the Black Widowers (2003)

Isaac Asimov: The Black Widowers series (1974-2003)

There's a certain laborious facetiousness in his work in this form - and in the fantasy genre, which he also ventured into in his later years - despite its undoubted smoothness and readability. The constant roguish and would-be flirtatious references to sex also date them somewhat, and make them increasingly difficult to stomach for a contemporary audience. Each to their taste, I suppose. Like virtually all of his fiction, they seem to have sold quite well, judging by the numbers of copies still to be found in second-hand bookshops.

So how should one sum up the life and work of Dr. Isaac Asimov? He appears to have had a good time, for the most part, and to have brought enjoyment to many, many readers. That's not a bad epitaph for any writer.

It's true that his reputation as a sage has now begun to fade, but it's hard to imagine a future where people will no longer read Foundation or the 'Robot' stories. His twin anthologies The Early Asimov (1972) and Before the Golden Age (1974) combine to give an excellent picture of that far-off era when Science Fiction (or the pulp variety, at any rate) was young.

For the rest, it's hard not to feel his levity became him well - at least he resisted the temptation to become a prophet, unlike his near-contemporaries Heinlein and Herbert, or (for that matter) his nemesis Arthur C. Clarke.

Isaac Asimov: Before the Golden Age: A Science Fiction Anthology of the 1930s (1974)

•

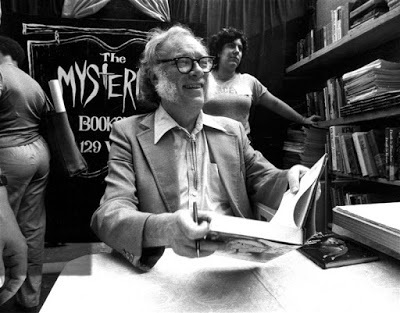

Isaac Asimov (1983)

Isaac Asimov

(1920-1992)

Novels:

Pebble in the Sky. 1950 (London: Sphere, 1974)The Stars, Like Dust. 1951 (London: Panther, 1965)Foundation. 1951 (London: Panther, 1973)Foundation and Empire. 1952 (London: Panther, 1976)The Currents of Space. 1952 (London: Panther, 1971)Second Foundation. 1953 (London: Panther, 1975)The Caves of Steel. 1954 (London: Panther, 1973)The End of Eternity. 1955 (London: Panther, 1972)The Naked Sun. 1957 (London: Panther, 1973)A Whiff of Death [as 'The Death Dealers', 1958] (London: Sphere, 1973)Fantastic Voyage. 1966. SF Collector’s Library (London: Corgi, 1973)The Gods Themselves. 1972. A Fawcett Crest Book (Greenwich, Conn: Fawcett Publications, Inc., 1973)The Heavenly Host (1975)Murder at the ABA [aka 'Authorised Murder']. 1976. A Fawcett Crest Book (Greenwich, Conn: Fawcett Publications, Inc., 1976)Foundation's Edge. 1982. A Del Rey Book (New York: Ballantine, 1983)The Robots of Dawn. 1983. A Del Rey Book (New York: Ballantine, 1984)Robots and Empire. 1985. A Del Rey Book (New York: Ballantine, 1985)Foundation and Earth. 1986. HarperVoyager (London: HarperCollins Publishers, 2016)Fantastic Voyage II: Destination Brain (1987)Prelude to Foundation. 1988. HarperVoyager (London: HarperCollins Publishers, 2016)Nemesis (1989)[with Robert Silverberg] Nightfall (1990)[with Robert Silverberg] Child of Time [aka 'The Ugly Little Boy'] (1992)Forward the Foundation. 1993. A Bantam Book (New York: Doubleday, 1994)[with Robert Silverberg] The Positronic Man (1993)

Short Story Collections:

I, Robot. 1950 (London: Panther, 1971)The Martian Way and Other Stories. 1955 (London: Panther, 1974)Earth Is Room Enough: Science Fiction Tales of Our Own Planet. 1957 (London: Panther, 1960)Nine Tomorrows: Tales of the Near Future (1959)The Rest of the Robots. 1964 (London: Panther, 1970)Through a Glass, Clearly (1967)Asimov's Mysteries. 1968 (London: Panther, 1972)Nightfall and Other Stories. 1969. 2 vols (London: Panther, 1973 / 1976)The Best New Thing (1971)The Early Asimov or, Eleven Years of Trying. 1972. 3 vols (London: Panther, 1979 / 1974 / 1974)The Best of Isaac Asimov (London: Sphere, 1973)Have You Seen These? (1974)Tales of the Black Widowers. 1974 (London: Panther, 1976)Buy Jupiter and Other Stories. 1975 (London: Panther, 1977)The Bicentennial Man. 1976 (London: Panther, 1978)More Tales of the Black Widowers. 1976. A Panther Book (London: Granada, 1980)The Key Word and Other Mysteries (1977)Casebook of the Black Widowers. 1980 (London: Panther, 1983)The Complete Robot. 1982 (London: Panther, 1983)The Winds of Change and Other Stories. 1983 (London: Panther, 1984)The Union Club Mysteries (1983)Banquets of the Black Widowers (1984)The Edge of Tomorrow (1985)The Disappearing Man and Other Mysteries (1985)The Alternate Asimovs (1986)The Best Science Fiction of Isaac Asimov (1986)The Best Mysteries of Isaac Asimov (1986)Robot Dreams (1986)Azazel. A Foundation Book (New York: Doubleday, 1988)Puzzles of the Black Widowers (1990)Robot Visions (1990)The Complete Stories. Vol. 1 of 2 ['Earth Is Room Enough', 'Nine Tomorrows', & 'Nightfall and Other Stories']. (London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1990)The Complete Stories. Vol. 2 of 2 (1992)Gold: The Final Science Fiction Collection (1995)Magic: The Final Fantasy Collection. 1996. Voyager (London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1997)The Return of the Black Widowers (2003)

Children's Books:

David Starr, Space Ranger. 1952 (London: New English Library, 1970)Lucky Starr and the Pirates of the Asteroids. 1953 (London: New English Library / Times Mirror, 1980)Lucky Starr and the Oceans of Venus. 1954 (London: New English Library, 1983)Lucky Starr and the Big Sun of Mercury. 1956 (London: New English Library, 1983)Lucky Starr and the Moons of Jupiter (1957)Lucky Starr and the Rings of Saturn. 1958 (London: New English Library, 1974)

[with Janet Asimov]:

Norby, the Mixed-Up Robot (1983)Norby's Other Secret (1984)Norby and the Lost Princess (1985)Norby and the Invaders (1985)Norby and the Queen's Necklace (1986)Norby Finds a Villain (1987)Norby Down to Earth (1988)Norby and Yobo's Great Adventure (1989)Norby and the Oldest Dragon (1990)Norby and the Court Jester (1991)

Non-fiction:

Asimov on Science Fiction. 1981 (London: Granada, 1983)

Edited:

Before the Golden Age: A Science Fiction Anthology of the 1930s (New York: Doubleday, 1974)The Annotated Gulliver's Travels: Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift. 1726 / 1734 / 1896 (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc. / Publishers, 1980)

•

Isaac Asimov, ed. The Annotated Gulliver's Travels (1980)

Published on December 18, 2020 12:29

December 7, 2020

Bryan Walpert: Late Sonata Launch (7/12/20)

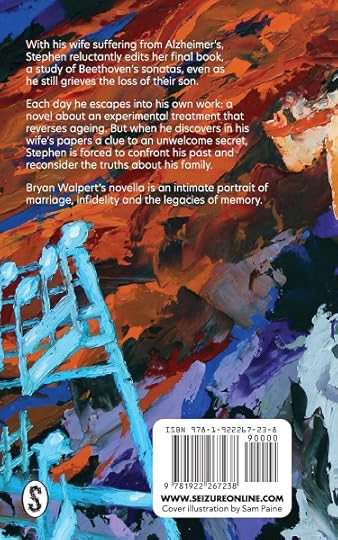

Bryan Walpert: Late Sonata blurb (2020)

Blurb:

With his wife suffering from Alzheimer's, Stephen reluctantly edits her final book, a study of Beethoven's sonatas, even as he still grieves the loss of their son.

Each day he escapes into his own work: a novel about an experimental treatment that reverses ageing. But when he discovers in his wife's papers a clue to an unwelcome secret, Stephen is forced to confront his past and reconsider the truths about his family.

Bryan Walpert's novella is an intimate portrait of marriage, infidelity and the legacies of memory.

WINNER OF THE 2020 VIVA LA NOVELLA PRIZE

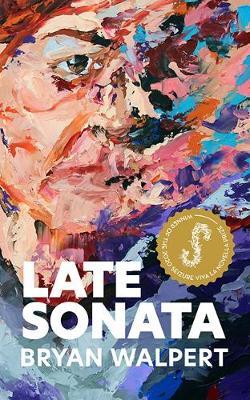

Bryan Walpert: Late Sonata (2020)

Here's my launch speech for Bryan Walpert's new, prize-winning novella, at the Open Book bookshop in Ponsonby:

The Open Book

I have to begin by stating an interest. I love novellas. I've written a number of them myself, and I adore the form. It's my belief that novellas are the jewel in the crown of New Zealand fiction - Katherine Mansfield’s The Aloe (1918), Frank Sargeson’s That Summer (1946), and Kirsty Gunn’s Rain (1994), to name just a few of the more obvious examples.

Not that there's anything wrong with novels. It's just that quite often all the real inventiveness and interest comes in the first hundred pages or so, and the rest serves mainly to protract the plotlines. It's in those cases that one suspects that a commercial motivation may have entered into what should have been a purely aesthetic decision.

Academy of NZ Literature: Bryan Walpert

Viva la Novella, then! It's great that Bryan Walpert has won this prize, offered by Australian publisher Brio Books, thus avoiding the curse of the short novel ("Novellas … boy, as far as marketability goes, you in a heap o’ trouble," as Stephen King, himself a distinguished practitioner of the form, so memorably put it).

Bryan's novella is concise, clever, and beautifully paced. His characters have all the depth and complexity to be expected of any fictional creations, great or small, and it's plain that no other form would have permitted him to shape them so well.

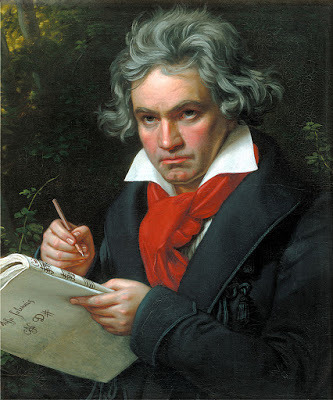

Joseph Karl Stieler: Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Which brings me to Ludwig van Beethoven. Bryan is by no means the first to base a literary work on a musical composition. Anthony Burgess's Napoleon Symphony is probably the most famous example, but they're not hard to find. The point is that it's a sonata he's chosen.