Jack Ross's Blog, page 17

February 22, 2020

Classic Ghost Story Writers (7): Ann Radcliffe

Ann Radcliffe (1764–1823)

There's an excellent story about Ann Radcliffe quoted in Devendra P. Varma's introduction to the Folio Society reprint of her very first novel, The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne: A Highland Story (1789):

Fantasies gathered around Mrs Radcliffe's later life. As the years rolled by in silence, various rumours floated on the wind. It was suggested that she was away in Italy gathering materials for a new romance. ... Another persistent report was that she had been driven insane by her own ghostly creations and confined to an asylum. A minor poet of the time rushed into print an 'Ode to Mrs Radcliffe on her lunacy.' It was often openly asserted that she was dead, and obituary notices appeared in some newspapers. The fun of it all is that she did not trouble to contradict more than one of the misleading reports. In an amazing anecdote narrated by Aline Grant, the biographer of Mrs Radcliffe, Robert Will, a hack writer, approached Cadell the publisher after a report of the novelist's death and offered him a romance - The Grave - under the name of The late Mrs Radcliffe. Consequently advertisements appeared in the newspapers.Se non è vero, è ben trovato, as the Italians put it - even if it's not true, it's well conceived. The story may be a bit hard to believe, but at least it paints her as a rather less solemn and humourless character than one might otherwise have expected, given her somewhat ponderous prose style.

Amused by this ridiculous news, Mrs Radcliffe arrived one evening at Soho Square and silently climbed the steep steps to Robert Will's attic. Opening the door noiselessly she stepped into a small chamber hung with black and decorated with skull, bones and other graveyard trappings. An hourglass stood upon a coffin and crossed-swords and a poniard adorned a side table. A young man in monk's garb was feverishly plying his quill in the light of a guttering candle.

Mrs Radcliffe seated herself in a chair opposite him, and whispered, 'Robert Will, what are you doing here?' The young man's hair stood on end with fright as he viewed the pale apparition opposite, ghastly in the flickering light. Her thin, white hand stretched out slowly, took the manuscript and held it over the candle flames. When it was reduced to ashes, the visitor glided out of the room as silently as she entered. Next day the terrified Robert Will rushed to inform the publisher that the ghost of Mrs Radcliffe had burned the manuscript. [x-xi]

E. Hull: 'Death found an author writing his life' (1827)

Of course, Ann Radcliffe's main claim to fame and the attention of posterity lies in Jane Austen's decision to guy the former's style and approach to fiction in Northanger Abbey , her own first novel, completed in 1803, but not published until after Austen's death in 1817.

The two are portrayed as meeting for a bit of a heart-to-heart in the 2007 film Becoming Jane , but there's no real evidence that this ever happened. It's rather sad to think that Radcliffe may have lived to read this parody of her early style, given the fact that Austen, her junior by more than a decade, actually predeceased her by six years. Talk about outliving your own fame!

Jane Austen meets Ann Radcliffe in Becoming Jane (2007)

The comparative crudity of Northanger Abbey has led some to underrate it by comparison with Austen's more mature romances. I remember once trying to persuade a tutorial class that the approach she had chosen was very similar to that employed by the - then current - Clint Eastwood film Unforgiven . They remained unconvinced (though, to do them justice, I doubt many of them had more than a superficial acquaintance with the classic westerns the film was parodying).

Unforgiven (1992)

As in most Clint Eastwood films, the main character, William Munny, is a superman who is able to mow down a whole saloon full of murdering hoodlums at the climax of the picture. Since it also aspires to be a 'realistic,' 'revisionist' western, this had to seem plausible in context.

The author of the screenplay, David Webb Peoples, accomplished this in a most elegant way:

First, by introducing a subplot about 'English Bob,' a murderous British bounty hunter (played by Richard Harris), who claims - mendaciously - to be a Duke, and who goes about accompanied by his biographer, W. W. Beauchamp, a naive hack whose job is to churn out an endless series of dime romances, with titles such as The Duke of Death, celebrating his employer. The sillier aspects of these books are relished greatly by Bob's nemesis, Sheriff 'Little Bill' Daggett (played by Gene Hackman), who takes it upon himself to instruct Beauchamp in the 'true' nature of frontier conflict.

Next, by peppering the second half of the film with anecdotes (mostly told by Little Bill) stressing how difficult it is to aim in the heat of the moment, how few bullets actually find a target, and the fact that even shooting a man in the back from a few feet away is far easier to accomplish in theory than in practice.

The film thereby sets up its own rival paradigms of truth and fiction. Fiction is the world of the dime novels, the inexhaustible six-guns, the dead-eyed marksmen, the ridiculously long odds in each mortal conflict. Truth (or should we say verisimilitude?) is the world of the movie itself: the mud, the filth, the racism and corruption of lawmen such as Little Bill, the easy victimisation of the innocent (such as the town whores), as well as the vicious amorality of mercenaries such as Munny.

And yet, in the final analysis, Clint Eastwood's character is as noble, straight-shooting, and basically invulnerable as any gunslinger in history! But we've been set up in advance to see this as believable because it is at least tangentially more realistic than The Duke of Death ...

Jane Austen: Northanger Abbey (1817)

I trust you see the analogy with Northanger Abbey? My students didn't. In short, then, Austen carefully sets up a fantasy realm in Catherine Morland's head, constructed of details from the Gothic novels she delights in reading (the more 'horrid' the better).

In this world, mysterious treasure-chests, floating apparitions and spectres, wicked noblemen, and imprisoned nuns are all commonplaces. She therefore assumes that a place so romantically named as 'Northanger Abbey' must be a positive hotbed of such things.

The truth of the matter, however, is that General Tilney, whom she falsely suspects of having murdered or imprisoned his own wife, is actually a far more commonplace thing: a money-grubbing snob who turns her out of doors as soon as he discovers her lack of funds.

The dramatic nature of Catherine's expulsion from the castle, and the unlikeliness of level-headed Henry Tilney sacrificing his future inheritance to win her hand, are thus (in their turn) rendered plausible by their contrast with the sheer absurdity of her Gothic imaginings.

In other words, a very unlikely rags-to-riches romance is made into a persuasively realistic-seeming piece of narrative by constantly contrasting it with another set of - patently ridiculous - fictional assumptions.

Northanger Editions of Jane Austen's Horrid Novels (Folio Society, 1968):

Castle of Wolfenbach

The Necromancer

The Mysterious Warning

The Orphan of the Rhine

Horrid Mysteries

The Midnight Bell

Claremont

in other words, there is no realism to be found in fiction except by contrast. Things do not unfold in reality the way they do in stories because, just as there are no straight lines in nature, there are no real narratives (with well-defined beginnings, middles, and ends), in the world around us.

To give our audiences - in whatever narrative genre - a sense of reality, we are forced to include elements sufficiently discordant with what they are used to encountering in stories (details such as the description of Leopold Bloom's bowel movements in the early pages of Ulysses, or the inordinate factual information in Zola-esque naturalism) to make them feel that they've somehow escaped from the tropes they're already so familiar with.

Since this is, in actuality, no more than a trick, it's necessary to keep on changing it up. For a while, simply breaking the fourth wall and acknowledging the illusory nature of the story we were being told was enough to recapture our attention (witness the work of Milan Kundera or Italo Calvino), but such techniques get steadily less effective over time.

What, then, of Ann Radcliffe herself? Was she really the naive and childish narrator pilloried by so many Austen critics, or did she have her own native sophistication as a narrative theorist?

What she's most famous for, of course, is providing - eventually - naturalistic explanations for all the apparently supernatural phenomena in her stories.

Stephen King: Danse Macabre (1981)

In Danse Macabre, his classic history / meditation on the whole horror genre, Stephen King explains succinctly just what's at stake when you make such decisions:

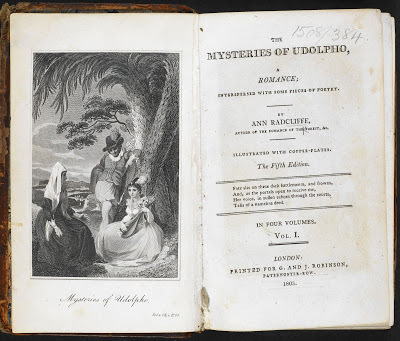

Nothing is so frightening as what's behind the closed door ... The audience holds its breath along with the protagonist as she/he (more often she) approaches that door. The protagonist throws it open, and there is a ten-foot-tall bug. The audience screams, but this particular scream has an oddly relieved sound to it. 'A bug ten feet tall is pretty horrible', the audience thinks, 'but I can deal with a ten-foot-tall bug. I was afraid it might be a hundred feet tall'.Only in her very last book, Gaston de Blondeville, written in 1802 but not published until three years after her death, in 1826 - a little like Northanger Abbey (1803/1817) itself, in fact - did Ann Radcliffe commit herself to a genuine spook. And even that may have been because the book was more of a private jeu-d'esprit than a commercial opus meant for publication.

... the artistic work of horror is almost always a disappointment. It is the classic no-win situation. You can scare people with the unknown for a long, long time ... but sooner or later, as in poker, you have to turn your down cards up. You have to open the door and show the audience what's behind it ... The thing is - and a pretty good thing for the human race, too, with such neato-keeno things to deal with as Dachau, Hiroshima, the Children's Crusade, mass starvation in Cambodia ... - the human consciousness can deal with almost anything ... which leaves the writer or director of the horror tale with a problem which is the psychological equivalent of inventing a faster-than-light space drive in the face of E=MC2.

There is and always has been a school of horror writers (I am not among them - it is playing to tie rather than to win) who believe that the way to beat this rap is never to open the door at all. [114-15]

Tzvetan Todorov: The Fantastic (1975)

Mind you, there are other ways to read it. As I explained in my previous post on E. T. A. Hoffmann, in his classic book on the Fantastic as a literary genre, Bulgarian critic Tzvetan Todorov explains how essential this moment of doubt and trepidation before the closed door is to a clear understanding of the form itself:

The fantastic occupies the duration of this uncertainty. Once we choose one answer or the other, we leave the fantastic for a neighbouring genre, the uncanny or the marvellous. The fantastic is that hesitation experienced by a person who knows only the laws of nature, confronting an apparently supernatural event.Ann Radcliffe is the prophet and lawgiver of this necessarily fleeting sense of the uncanny - acknowledged as such by Todorov and other European critics who've always showed her considerably more respect than her Austen-influenced compatriots.

As a child the young Fyodor Dostoyevsky was deeply impressed by Radcliffe. In Winter Notes on Summer Impressions (1863) he writes, "I used to spend the long winter hours before bed listening (for I could not yet read), agape with ecstasy and terror, as my parents read aloud to me from the novels of Ann Radcliffe. Then I would rave deliriously about them in my sleep." - WikipediaPerhaps, then, it might be as well to give the last word to Radcliffe herself:

O! useful may it be to have shewn, that, though the vicious can sometimes pour affliction upon the good, their power is transient and their punishment certain; and that innocence, though oppressed by injustice, shall, supported by patience, finally triumph over misfortune!

And, if the weak hand, that has recorded this tale, has, by its scenes, beguiled the mourner of one hour of sorrow, or, by its moral, taught him to sustain it — the effort, however humble, has not been vain, nor is the writer unrewarded. ― Ann Radcliffe, The Mysteries of Udolpho

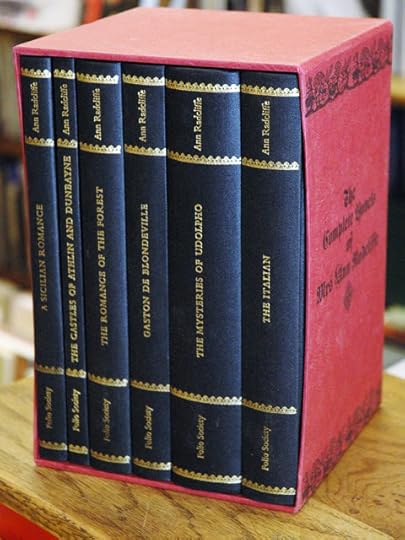

The Complete Novels of Mrs Ann Radcliffe (Folio Society, 1987)

Ann Radcliffe

(1764–1823)

The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne: A Highland Story. 1789. Introduction by Devendra P. Varma. Wood Engraving by Sarah van Niekerk. The Complete Novels of Mrs Ann Radcliffe, 1. London: The Folio Society, 1987.

A Sicilian Romance. 1790. Introduction by Devendra P. Varma. Wood Engraving by Sarah van Niekerk. The Complete Novels of Mrs Ann Radcliffe, 2. London: The Folio Society, 1987.

The Romance of the Forest. 1791. Introduction by Devendra P. Varma. Wood Engraving by Sarah van Niekerk. The Complete Novels of Mrs Ann Radcliffe, 3. London: The Folio Society, 1987.

The Mysteries of Udolpho: A Romance, Interspersed with Some Pieces of Poetry. 1794. Ed. Bonamy Debrée. Notes by Frederick Garber. 1966. Oxford English Novels. London: Oxford University Press, 1970.

The Italian, or The Confessional of the Black Penitents: A Romance. 1797. Ed. Frederick Garber. 1968. Oxford English Novels. London: Oxford University Press, 1970.

Gaston de Blondeville, or The Court of Henry the Third Keeping Festival in Arden. 1826. Introduction by Devendra P. Varma. Wood Engraving by Sarah van Niekerk. The Complete Novels of Mrs Ann Radcliffe, 6. London: The Folio Society, 1987.

Ann Radcliffe: The Mysteries of Udolpho (1803)

Published on February 22, 2020 12:42

January 27, 2020

Classic Ghost Story Writers (6): Edward Lucas White

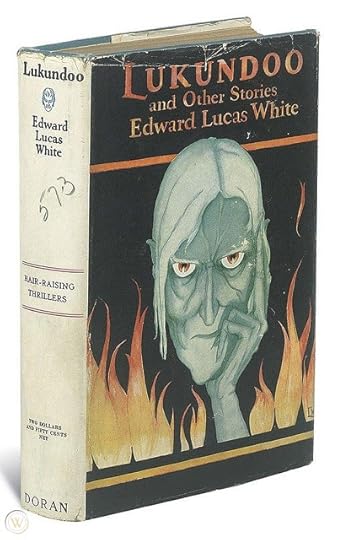

Edward Lucas White: Lukundoo (1927)

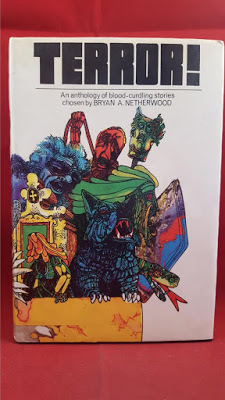

I think that the first time I encountered one of Edward Lucas White's stories was in Bryan Netherwood's aptly named collection Terror! An Anthology of Blood-curdling Stories. The story in question was 'Amina,' and there was a matter-of-fact simplicity about it which made a deep impression on me.

To be sure, it concerns a ghoul, but she is certainly the most realistic - and, indeed, most sympathetic - bloodsucker I'd ever met. Her simple remark, 'We shall have to drink shortly, but it will be warm,' still haunts me to this day.

Bryan Netherwood, ed.: Terror! An Anthology of Blood-curdling Stories (1970)

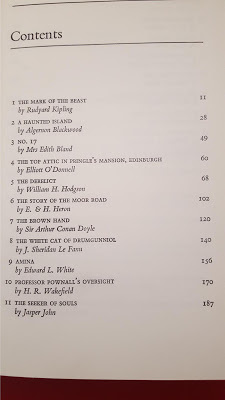

Next came the title story in Kathleen Lines' The House of the Nightmare and Other Eerie Tales. I spent a good deal of my time as a kid reading such anthologies, most of the time coming across the same old chestnuts: H. G. Wells' 'The Red Room,' Rudyard Kipling's ' The Mark of the Beast,' Arthur Conan Doyle's 'Lot no. 249' ...

Every now and then, though, I'd find something new and exciting. There was something quite strange and original about this E. L. White's fiction - something that made it stand out from the otherwise fairly predictable ruck of Edwardian spine-chillers.

It was an experience of the same order - though certainly not of the same kind - as my first reading of H. P. Lovecraft's 'The Dunwich Horror.' I'd already read 'The Colour out of Space' (Lovecraft's personal favourite among all of his stories). That was still roughly assimilable to my own general sense of the outlines of the 'weird story, though - 'The Dunwich Horror,' and the various vicissitudes of Wilbur Whateley and his sinister kinfolk, came from another universe entirely.

Kathleen Lines, ed. The House of the Nightmare and Other Eerie Tales (1967)

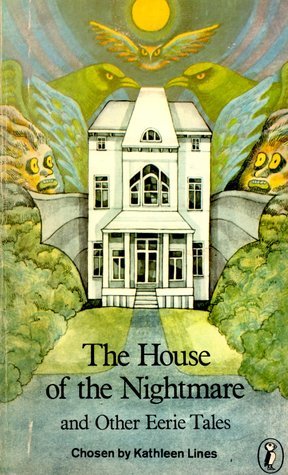

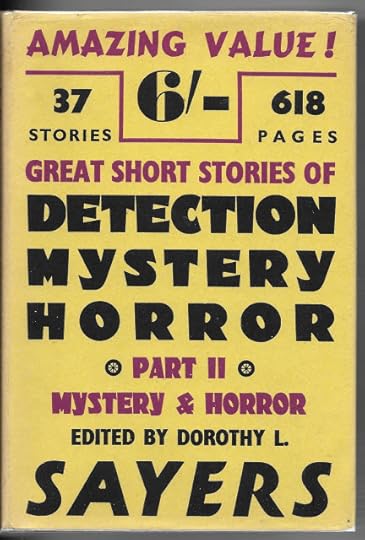

Last (but not least) I read 'Lukundoo' itself in one of the greatest of all short story anthologies, Dorothy L. Sayers' 3-part Great Short Stories of Detection, Mystery and Horror (1928-34 / reprinted in 6 volumes in 1950-51).

Dorothy L. Sayers, ed. Great Short Stories of Detection, Mystery and Horror (1928 / 1951)

'Lukundoo' was a trip, all right. I still have nightmares about that razor. But, of course, that was really the point. I'd gathered from carefully poring over the bio-notes in each of the collections above that White's fiction was - or at least purported to be - a simple transcript of his dreams.

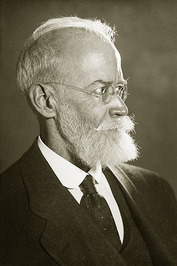

Edward Lucas White (1866-1934)

He'd apparently had an illness during which his nightmares became particularly vivid and unpleasant, and had tried to exorcise the effect of these haunting images by writing them down as 'short stories.'

Looking at the blurb to the first edition, below, one gets the impression that this must have come as a bit of a nasty shock to his regular publishers, as well as what they refer to optimistically as 'his army of readers,' who were presumably expecting another historical novel in his more customary style:

Lukundoo: blurb (1927)

Mr. White, best known as the author of the memorable EL SUPREMO, here shows himself master of quite another style.

Tales of mystery and horror compose the greater part of the present volume - tales that prickle the skin and curdle the blood - tales that are told with that fine art of the thriller which, opening on a subtle note of suspense, develops surely and fearfully until the heart is brought pounding to the throat and the dénouement is reached with a sense of pure relief.

Whatever the personal preferences of Mr. White's army of readers, they will find him as expert a story-teller in the realm of the weird and the fantastic as ever they found him in that of the historical novel wherein his reputation has been so firmly established.

Certainly the 'personal preferences' of the blurb writer do not seem to extend as far as the actual enjoyment of these heart-pounding dénouements, reached in each case (it would appear) 'with a sense of pure relief.'

In any case, he did not offend in the same way again. His only subsequent publications were a history book, Why Rome Fell (1927), and a memoir attesting to the happiness of his marriage, Matrimony (1932):

On March 30, 1934, seven years to the day after the death of his wife Agnes Gerry, he committed suicide by gas inhalation in the bathroom of his Baltimore home.It's hard to convey to young readers today the sheer difference between exploring such byways of weird fiction in the 1970s and the comparative ease of doing so now, more than forty years later. The book Lukundoo was unobtainable to me. It wasn't in any of the libraries I frequented, or even had access to via interloan. In fact, it wasn't until I went to the UK to study in the mid-1980s that I began to be able to read such things.

- Wikipedia

Edinburgh, where I was studying, was the proud possessor of a copyright library. There are six of these in Britain:

In the United Kingdom, the Legal Deposit Libraries Act 2003 restates the Copyright Act 1911, that one copy of every book published there must be sent to the national library (the British Library); five other libraries (the Bodleian Library at Oxford University, the Cambridge University Library, the National Library of Scotland, the Trinity College Library, Dublin, and the National Library of Wales) are entitled to request a free copy within one year of publication.This did not mean that the National Library of Scotland had everything contained in the British Library, but it did mean that there was a reasonably good chance of having access to most things you could think of through its stacks.

- Wikipedia

And, yes, it did have a copy of Lukundoo. Which I duly read, perched uncomfortably in the reading room there, possibly the least congenial place imaginable to pore over so strange and atmospheric a work.

Lukundoo (1927)

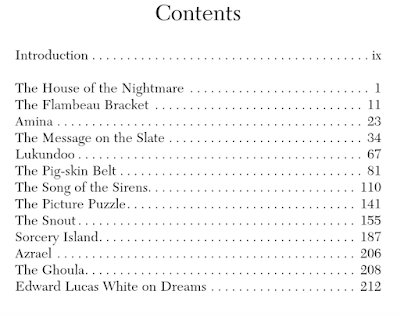

Lukundoo and Other Stories (1927):

contents: LukundooFloki's BladeThe Picture PuzzleThe SnoutAlfandega 49aThe Message on the SlateAminaThe Pig-Skin BeltThe House of the NightmareSorcery Island

Possibly for that reason, it came as a sore disappointment to me. None of the other stories, 'weird' though they undoubtedly were, seemed to come up to the standard of the three I'd read already. They seemed too arbitrarily 'dream-like', lacking the circumstantial solidity of (especially) 'Amina' and 'Lukundoo.'

S. T. Joshi, ed.: The Stuff of Dreams: The Weird Stories of Edward Lucas White (2016)

The other day, whilst pursuing my strange quest to acquire everything substantive by (or about) H. P. Lovecraft - for more on this, see my posts here and here - I stumbled across the volume above.

So great had been my disappointment on finally getting to read White's book, that it had never really occurred to me to research him since. Now, though, for a very reasonable cost, it seemed possible to obtain most of the stories in Lukundoo together with some of the posthumous material published since.

S. T. Joshi, ed.: The Stuff of Dreams: contents (2016)

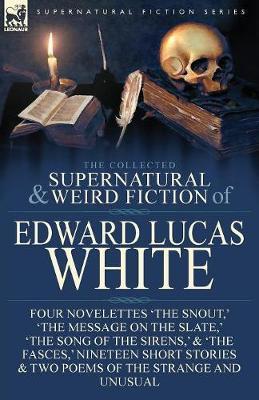

Mind you, if I'd waited a bit longer, I might have been tempted to go as far as the book below, described on its cover as containing 'Four Novelettes: "The Snout," "The Message on the Slate," "The Song of the Sirens," & "The Fasces," Nineteen Short Stories & Two Poems of the Strange and Unusual':

The Collected Supernatural and Weird Fiction of Edward Lucas White (2017)

That might, however, have been a step too far. In any case, I note from the Wikipedia article on him that:

During 1885 White began a utopian science fiction novel, Plus Ultra. He destroyed the first draft and started over in 1901, then worked on it for most of the rest of his life. The resulting monumental work — estimated by one critic [S. T. Joshi] at 500,000 words — remains unpublished, although a portion of it was released separately in 1920 as the novella From Behind the Stars.This fascinating sounding work must therefore have been begun by White before the appearance of Edward Bellamy's classic Looking Backward (1888), and written over roughly the same period as Austin Tappan Wright's similarly immense Islandia (1941), which I've previously written about .

•

That was the before. Here is the after. I've now received (and read) Joshi's selection of Edward Lucas White's 'weird stories', and I'm sorry to report that most of the 'extra' stories in it suffer from the excessive padding so typical of the period, and yet so conspicuously lacking in the three described above. It's almost, in fact, as if they were written by another author altogether ...

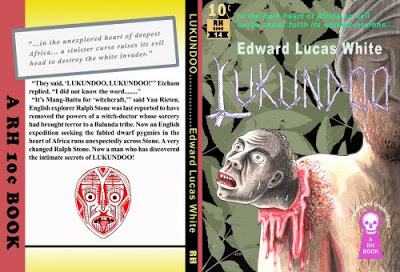

There remains, in any case, 'Lukundoo' itself. According to the blurb of the horribly garish version below:

One of Alfred Hitchcock's favorite tales, he lamented that it was a story "they wouldn't let him do on TV."In case even that isn't alluring enough, they add helpfully: 'This is a book that goes to the heart of darkness - and beyond.'

Edward Lucas White: Lukundoo (1927)

Published on January 27, 2020 17:11

January 20, 2020

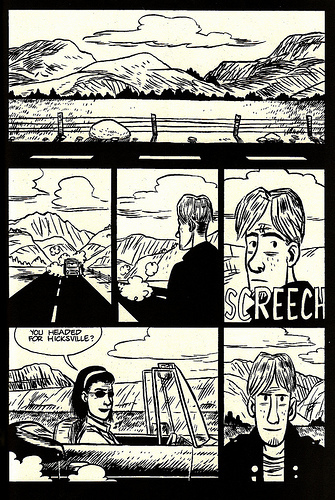

'You headed for Hicksville?'

'You headed for Hicksville?'

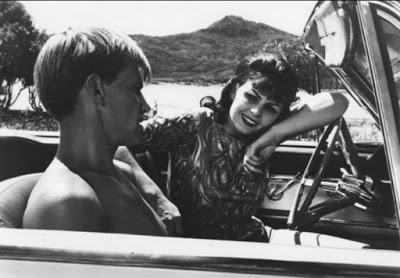

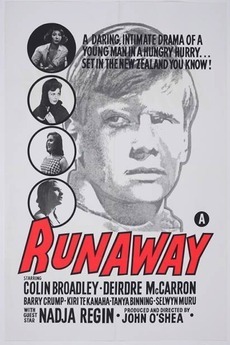

In my earlier post on Dylan Horrocks graphic novel Hicksville (1998), I mentioned that this page of his comic reenacts a classic scene from John O'Shea's 1964 film Runaway.

John O'Shea, dir.: Runaway (1964)

The scene with the car in O'Shea's film is (you'll no doubt recall) set up north, on the Hokianga harbour, whereas Horrocks' imaginary "Hicksville" is located in Hicks Bay, near the tip of East Cape.

John O'Shea, dir.: Runaway (1964)

More than fifty years on, East Cape really is one of the last parts of New Zealand where you can recover that sense of emptiness and distance which were once an essential part of the local experience. As the poster says: 'Set in the New Zealand you know' - or, rather, that you once knew.

Te Araroa and East Cape

So, on our latest drive back home from Wellington, we decided to go the long way round. Headed for Hicksville? You betcha!

•

How do you get there?

Reading the Maps (2007)

Well, obviously the first thing to is to check it out on the map. I knew that the road would be pretty rough from Gisborne, but I have to say that I hadn't remembered that the route from Napier to Gisborne was so long and demanding. East Cape, with its wide open spaces and gentle curves, was quite a rest-cure by comparison!

Bronwyn Lloyd [BL]: Tolaga Bay (18/1/20)

Tolaga Bay was the scene of a particularly traumatic childhood holiday for Bronwyn, so we were duty-bound to stop and take a look at the place. It gives you some sense of the territory, I think - a few sandy footprints, a driftwood-strewn beach, a half-empty campground ...

•

Where should you stay?

BL: Hicks Bay Motel Lodge (18/1/20)

There's really only one answer. If Hicks Bay is your destination, then the Hicks Bay Motel Lodge is the obvious place to hang your hat.

Situated on the hill above the township, there's certainly no shortage of magnificent views. The buildings themselves seem to date from another era. They've been modernised a bit inside, but from the outside they look like nothing so much as the Christian Youth Camps we used to get sent to periodically when my parents wanted a bit of peace and quiet.

There's even a restaurant - with a bar and off-licence attached. There's not a lot of choice, really, but we did enjoy our meal there, nestled romantically in the far corner of the dining room.

•

Why Hicks Bay?

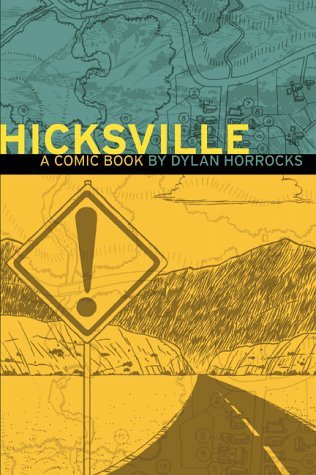

Dylan Horrocks: Hicksville (1998)

I've already mentioned the Dylan Horrocks connection: Hicks Bay is the approximate setting for his imaginary hamlet of Hicksville, "a quiet seaside town where the beach is sunny, the tea is hot, the locals are friendly, and everyone loves comics", as the blurb to the slightly expanded 2010 version has it:

Dylan Horrocks: Hicksville (2010)

Every detail of this town is etched in the memory of his fans: The Rarebit Fiend tearooms; Mrs. Hicks' Hicksville Book Shop and Lending Library; Kupe's lighthouse, home of the secret comics library ...

Xavier Guilbert: Interview with Dylan Horrocks (2016)

And, for a moment at least, one can almost persuade oneself that it's really (almost) all there:

JR: Hicks Bay (19/1/20)

Rarebit Fiend, anyone?

There is, of course, a lot more to the place than that. Thirty years before Hicksville, New Zealand novelist David Ballantyne wrote a dark, strange, moody thriller, set in the imaginary beach settlement of "Calliope Bay," which just happens to bear an uncanny resemblance to Hicks Bay.

David Ballantyne: Sydney Bridge Upside Down (1968)

There was an old man who lived on the edge of the world, and he had a horse called Sydney Bridge Upside Down. He was a scar-faced old man and his horse was a slow-moving bag of bones, and I start with this man and his horse because they were there for all the terrible happenings up the coast that summer, always somewhere around.How's that for an arresting opening? It's almost as if he'd set out to beat the celebrated first sentence of The Scarecrow, published just five years before:

- David Ballantyne. Sydney Bridge Upside Down. 1968 (Auckland: Longman Paul, 1981): 5.

The same week our fowls were stolen, Daphne Moran had her throat cut.If you're curious to know more, there's an excellent discussion of Ballantyne's novel and its background on pp. 162-67 of Bryan Reid's After the Fireworks: A Life of David Ballantyne (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2004).

- Ronald Hugh Morrieson. The Scarecrow. 1963 (Auckland: Penguin, 1981): 1.

Nor do the literary antecedents end there. Four decades later, Steve Braunias decided to play the place a visit, and this is how he begins his account:

Steve Braunias: Civilisation: Twenty Places on the Edge of the World (2012)

There was an old man who lived at the edge of the world. 'When I look back on my life,' Lance Roberts said, 'I've done a lot of killing.

I met him at his monstrous house. Someone had once written that they heard screams and bleats there on still nights. Outside, the long horizontal line of the blue Pacific looked sharp as a knife. The blade flashed in the bright sun. It cut the sky in half.

- Steve Braunias. 'Hicks Bay: A History of Meat.' In Civilisation: Twenty Places on the Edge of the World. 2012 (Wellington: Awa Press, 2013): 1.

Here's Lance Roberts' "monstrous house", the old Hicks Bay freezing works, seen from the road, half-hidden by trees - then closer up:

BL: Hicks Bay (19/1/20)

And here's "the long horizontal line of the blue Pacific":

•

Hicks Bay or Hicksville?

BL: Hicks Bay (19/1/20)

Just a few atmosphere shots to remind us what it's like if we ever feel tempted to go back there.

JR: Hicks Bay (19/1/20)

Though, to be honest, I'd really have preferred to have stayed a bit longer. It certainly is peaceful there. Edgy, yes - Braunias is right about that, but there's no point in pretending that we were even able to start on the long task of unravelling its mana and mystique.

I don't know if this trip means that I'll be able to appreciate Hicksville - or, for that matter, Sydney Bridge Upside Down - any better from now on, but there's no denying that HIcks Bay certainly is unique.

And those of you who've never explored the East Cape of New Zealand are definitely missing something: a tiny window on what the country used to be, how it felt to drive around it in my father's station waggon some fifty years ago.

•

BL: Hicks Bay (19/1/20)

Published on January 20, 2020 14:57

December 17, 2019

The Terror

The Terror

[2018 TV series created by David Kajganich, based on Dan Simmons's 2007 novel]

Friday, 28th June, 1850

A curious thing. We were in our small boat examining a piece of flotsam spotted by Abbot in the hope that it might have come from one of the ships. There was ice all around us, but being in deep water this neither obstructed nor threatened us in any way. The flotsam gave no indication of its origin, and as I inspected my pocket watch to note the time of our sighting for Pioneer's log, Abbot warned me against losing it overboard, pointing out to me that such was the depth of the water upon which we rowed that had I been careless enough to drop the watch it would have been telling yesterday's time before it struck the bottom.

Lt Sherard Osborn R. N.

Stray Leaves from an Arctic Journal, 1852

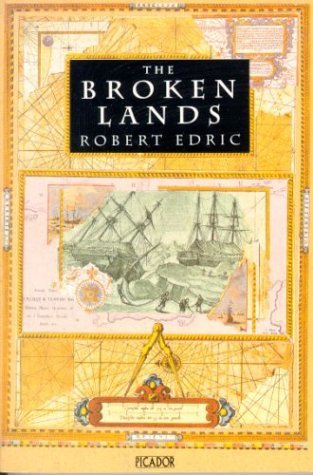

That's not a quote from either David Kajganich's TV series The Terror, or even from Dan Simmons' book of the same name. Instead, it stands as the epigraph for Robert Edric's earlier novel The Broken Lands, which also attempted, a couple of decades earlier, to recreate the horror of Sir John Franklin's famous 'lost expedition.' Franklin set out in 1845 in the two (appropriately-named) ships Erebus and Terror to find the North-West passage, and not one of the participants, officers or crew, was ever seen alive again.

Robert Edric: The Broken Lands (1992)

There's a kind of poetic trippiness about Edric's version which perhaps befits what seems, in retrospect, a somewhat statelier time (not that the 1990s felt like that to us then). Evocative vistas, carefully honed epiphanies, and a general emphasis on style above substance distinguished much of the fiction of that decade.

I do still love that idea of the pocket watch sinking rapidly into the icy water, down and down and down, far enough down to strike "yesterday's time before it struck the bottom," though. I suppose it's as good an image as any for the art of the historical novelist - painting a vision so detailed and psychologically acute that it convinces all who experience it that that's how it must have been.

Edwin Landseer: Man Proposes, God Disposes (1864)

Not that Edric was the first to attempt it, by any means. There's always been something about the Franklin expedition which has appealed to myth-makers and psychogeographers. Edwin Landseer, better known for 'The Monarch of the Glen' and The Stag at Bay,' was much criticised for his vision, above, of polar bears gnawing at the exposed ribs of frozen sailors, when he showed it at the 1864 Royal Academy exhibition.

Perhaps, indeed, that was the motivation behind Millais's even more famous painting 'The North-West Passage' - promoting a message of imperial derring-do and bulldog intrepidity more acceptable to the Victorian establishment:

John Everett Millais: The North-West Passage (1874)

It seems only fitting that the figure of the Old Salt in Millais's picture should have been modelled on Lord Byron's old friend Edward John Trelawny. Trelawny, author of the novel Adventures of a Younger Son (1831) as well as the almost equally fictional memoir Recollections of the Last Days of Shelley and Byron (1858), wrote a famous account of plucking the unburnt heart of Shelley from that famous bonfire on the beach after the latter was drowned at sea. Whether he really did risk the flames in that reckless manner is anyone's guess.

Louis Édouard Fournier: The Funeral of Shelley (1889)

[l-to-r: Trelawny, Leigh Hunt, and Byron; Mary Shelley, seen kneeling, was actually not allowed to attend]

All of which brings us back to The Terror. My own interest in the whole subject of the many, many expeditions in search of the North-West passage probably goes back as far as my childhood reading of the 'Classics Illustrated' comic below (which I'm glad to say I still own):

World Illustrated: Story of the Northwest Passage (No. 531)

A rather more sophisticated - though actually just as dramatic - account is given in Glyn Williams' more recent Voyages of Delusion (entitled, in America, Arctic Labyrinth: The Quest for the Northwest Passage):

Glyn Williams: Voyages of Delusion: The Search for the Northwest Passage in the Age of Reason (2002)

So you can imagine that as soon as I saw those images of poor old Ciarán Hinds contemplating his end in the snow, it was only a matter of time before I watched the whole series. It might have been nice if it'd been possible to do so on some convenient streaming service, but never mind, I'm now the owner of a brand spanking new DVD of the whole thing.

The Terror (2018)

Is it a masterpiece? Too early to say, I suppose, but certainly the mise-en-scène looks brilliantly, hauntingly real - as befits any production under the supervision of Ridley Scott, or at any rate his production company Scott Free. The performances from all the various principals - Jared Harris as Captain Francis Crozier, Tobias Menzies as Commander James Fitzjames, Paul Ready as Dr. Harry Goodsir, and Ciarán Hinds as Franklin - are flawless. It also contains the slimiest, most reprehensible villain since Shakespeare dreamed up Iago as the ideal foil for his hero Othello.

I don't really want to say too much more about it, for fear of ruining the suspense for those of you who haven't yet watched it. Suspense and mystery are, after all, the lifeblood of stories such as these. Suffice it to say that all is not as it seems in these frozen wastes, and that David Kajganich's vision is probably closer to Edwin Landseer's (above) than to John Millais's.

If you'd like something more decorous and meditative, stick to The Broken Lands. This particular version of Franklin's story is as violent and bloody as anything I've ever seen on TV. It's more for fans of H. P. Lovecraft's lurid melodrama At the Mountains of Madness than for admirers (if there are any still left) of the 1948 film version of Scott of the Antarctic .

Jared Harris (1961- )

The presence, in the cast, of Jared Harris, has the effect - or so I would imagine, at least - of reminding us of his more recent star-making turn in the HBO miniseries Chernobyl. The pompous inanities and downright lies of such people as Sir John Franklin and his allies back in London seem not too far away from the rather more serious untruths promulgated in the latter series. In both cases, it would seem, if you want the craggy face of integrity, you go to Jared Harris (a long cry from his role as the most villainous villain of all in the TV Sci-fi series Fringe ).

Chernobyl

[2019 TV series created and written by Craig Mazin, directed by Johan Renck]

'Every lie we tell incurs a debt to the truth. Sooner or later that debt is paid.'

- Craig Mazin, Chernobyl (2019).

I wrote this poem some time ago, as a response to the (so-called) 'Polar-Bear-gate' scandal. It now seems to me strangely appropriate to the themes and atmosphere of the magnificent Chernobyl and the gut-wrenching The Terror alike:

•

Peter Gleick: Stranded Polar Bear (2010)

Stranded Polar Bear

The ripples imply

a boat’s passed by

or something larger

like a whale

the islet’s small

and artificial

looking

like the bear

enduring exile

Augustus sent

his family

to islands

small enough

to terrify

even the young

willing to die

until you realise

it’s a fake

that bear

was never there

even his shadow

clouds and drift ice

carefully placed

to make the point

that lying is okay

when the legend becomes fact

print the legend

said John Ford

by saying it

he showed

he didn’t mean it

Paul Nicklin: Polar Bears (2010)

Published on December 17, 2019 11:29

December 11, 2019

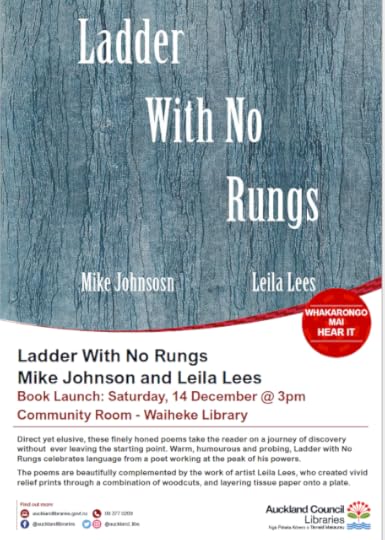

Mike Johnson & Leila Lees - Booklaunch on Waiheke Saturday 14th December

Mike Johnson & Leila Lees: Ladder With No Rungs

Booklaunch

Mike Johnson & Leila Lees:

Ladder With No Rungs

Community Room - Waiheke Library.

Saturday 14th December @3 pm.

ALL WELCOME

Mike asked me to come along on Saturday to say a few words about his new book, but unfortunately I'm unable to make it. Once before, in 2007, I did make the trip to Waiheke to speak about one of his books of poetry, and this is what I had to say on that occasion.

That was a lot of years ago, though. Since then his rate of production has, if anything, increased - as you can see from the bibliography I've included below. Nor has he allowed himself to be pigeon-holed as a novelist who occasionally writes poetry (or, for that matter, as a poet who's gone over to prose ...). Both modes seem equally natural to Mike, and he's continued to produce distinguished work in each genre.

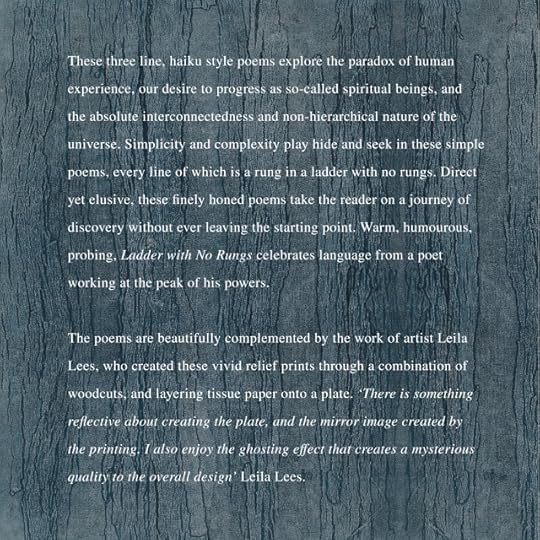

I'm told that there's a substantial new novel in the offing, and I'm very much looking forward to reading that. In the meantime, though, this latest book of poems seems quite ambitious enough. The poems themselves are short, "haiku style" verses charting the way of a soul in the world and (in particular) through relationships with nature and with each other.

Ladder With No Rungs: Blurb

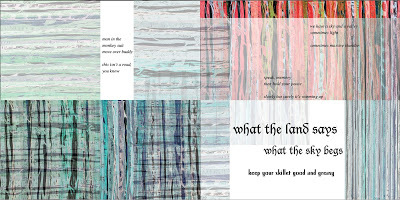

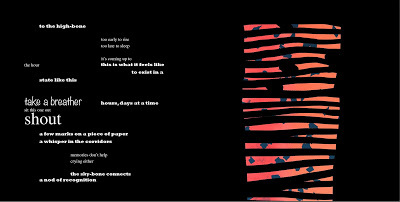

Leila Lees' graphic works do indeed seem like the perfect accompaniment to Mike's words. The book would be well worth having just for those, in fact. There's yet another technical innovation - albeit quite a light-hearted one - to recommend it, though. I'm referring to the final section, where lines and words surplus to the main text have been presented in a graphic extravaganza of colour and experimental form.

This is what Mike had to say about this part of the book on Facebook (25/9/19):

Ladder With No Rungs: Rejects (1)

What qualifies a poem as a reject? My next book of poetry, LADDER WITH NO RUNGS is in preparation, with the last section entitled REJECTS. Instead of the rejects going into the trash, I suggested to Daniela Gast, our book designer, that she 'mangle them up' in contrast to the rest of the book. Like you'd screw up a piece of paper. And what a wonderful result she achieved. So these are my words, suitably mangled, Leila Lees' art work, suitably mangled, and the work of Daniela, Mangler in Chief. Enjoy!

Ladder With No Rungs: Rejects (2)

I hope that everyone who's able to attend has a wonderful time. I'm sure they will. Though I can't be there in person, I'll certainly be lifting a glass to Mike and Leila in spirit. This is probably the most delightful books of poems I've read this year - moreover, it's a truly collaborative work between artist, designer and poet, something much rarer than it should be.

Lasavia Publishing is quitting the year 2019 in style. Bring on 2020, and the bumper crop of new books it no doubt has in store for us!

on the seventh hour they lay down

to rest

their words hung in the ruby air

first ever dawn chorus

making a fuss

[Ladder With No Rungs, p.24]

•

Mike Johnson

Mike Johnson

Select Bibliography:

Poetry:

The Palanquin Ropes. Wellington: Voice Press, 1983.From a Woman in Mt Eden Prison & Drawing Lessons. Auckland: Hard Echo Press, 1984.Standing Wave. Auckland: Hard Echo Press, 1985.Treasure Hunt. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1996.The Vertical Harp: Selected Poems of Li He. Auckland: Titus Books, 2006.To Beatrice Where We Crossed The Line. Auckland: Second Avenue Press, 2014.Two Lines and a Garden. Illustrated by Leila Lees. Auckland: Lasavia Publishing, 2017.Ladder with No Rungs. Illustrated by Leila Lees. Auckland: Lasavia Publishing, 2019.

Fiction:

Lear: the Shakespeare Company Plays Lear at Babylon. Auckland: Hard Echo Press, 1986.Lear: the Shakespeare Company Plays Lear at Babylon. Auckland: Lasavia Publishing, 2016.Anti Body Positive. Auckland: Hard Echo Press, 1988.Zombie in a Space Suit. Auckland: Lasavia Publishing, 2018.Lethal Dose. Auckland: Hard Echo Press, 1991.Lethal Dose. Auckland: Lasavia Publishing, 2019.Foreigners. Auckland: Penguin, 1991.Dumbshow. Dunedin: Longacre Press, 1996.Counterpart. Auckland: Voyager, 2001.Stench. Christchurch: Hazard Press, 2004.Travesty. Illustrated by Darren Sheehan. Auckland: Titus Books, 2010.Hold my Teeth While I Teach you to Dance. Auckland: Lasavia Publishing, 2014.Back in the Day: Tales from NZ’s Own Paradise Island. Auckland: Lasavia Publishing, 2015.Confessions of a Cockroach / Headstone. Auckland: Lasavia Publishing, 2017.

For children:

Taniwha. Illustrated by Jennifer Rackham. Auckland: Lasavia Publishing, 2015.

Non-fiction:

The Angel of Compassion. Auckland: Lasavia Publishing, 2014.

•

Leila Lees

Leila Lees

Select Bibliography:

Mike Johnson: Two Lines and a Garden. Illustrated by Leila Lees. Auckland: Lasavia Publishing, 2017.Into the World: A Handbook for Mystical and Shamanic Practice. Auckland: Lasavia Publishing, 2019.Mike Johnson: Ladder with No Rungs. Illustrated by Leila Lees. Auckland: Lasavia Publishing, 2019.

•

Leila Lees: Into the World: A Handbook for Mystical and Shamanic Practice (2019)

Published on December 11, 2019 12:06

December 8, 2019

Behrouz Boochani and Kyriarchy

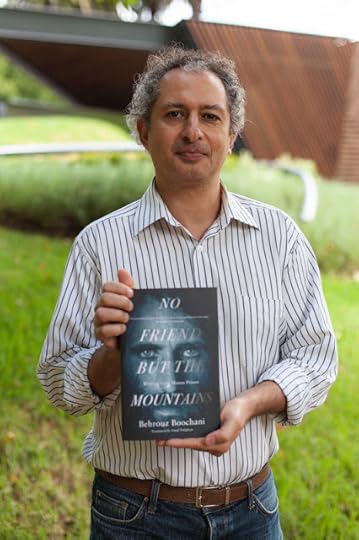

Behrouz Boochani: No Friend but the Mountains: Writing from Manus Prison (2019)

"The sovereignty of the waves has collapsed the moral framework."

- Behrouz Boochani, No Friend but the Mountains, p.16

You know how it is when everyone's telling you that you simply must read a particular book? How a certain reluctance starts to set in? A refusal to be herded, to walk in their footsteps in order to repeat some pale simulacrum of their experience?

Unreasonable, perhaps, but that's how it is. One of my colleagues, Rand Hazou, lent me his own copy of Behrouz Boochani's prison memoir, so I thought this might be a good way to sample it before actually deciding whether or not to add it to my already overcrowded bookshelves.

Varlam Shalamov: Kolyma Tales (1995)

I have read a number of prison memoirs in my time: I date from the era when every dissident memoir from the Soviet Union was there to be appalled by: Evgenia Ginzburg (Into the Whirlwind & Within the Whirlwind), Natalia Gorbanevskaya (Red Square at Noon), Anatoly Marchenko (My Testimony), Irina Ratushinskaya (Grey is the Colour of Hope) - not to mention the collected works of Andrei Sakharov, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Varlam Shalamov (if you haven't read him, you really should: Kolyma Tales is a great work).

Jacobo Timerman:

As well as those, there were books from Latin America (Prisoner Without A Name, Cell Without a Number, by Jacobo Timerman); Africa (The Man Died: Prison Notes, by Wole Soyinka); not to mention - going back a bit - Nazi Germany (I was Hitler's Prisoner, by Stefan Lorant); and the Spanish Civil War (Dialogue with Death, by Arthur Koestler). Let's just say, in summary, that it's not an entirely unfamiliar genre to me.

Much of the interest around Boochani's book has focussed on its extraordinarily convoluted mode of composition and transmission to the outside world: it was sent in fragments through text messages, then converted into blocks of pdf text, and finally passed on to his translator, Omid Tofighian.

Omid Tofighian (2019)

Actually this is probably the least interesting aspect of the book. Certainly this method has had an influence on the extraordinarily close relationship between translator and author which characterises it, but possibly this would have grown up organically anyway.

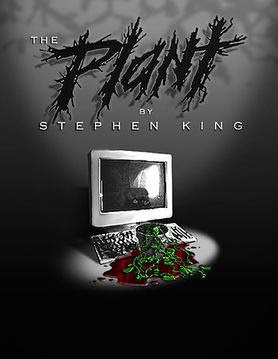

Stephen King: The Plant (2000)

All in all, it reminds me a little of Stephen King's somewhat abortive experiment with online publication twenty years back, when he published his then-latest short story, Riding the Bullet, as the "world's first mass-market e-book, available for download at $2.50."

King complained later that everyone who wanted to talk to him about it focussed on the method of publication, while none of them seemed to feel the slightest interest in the story itself. Frustrated, he gave up on his follow-up plan to issue a serial novel, , in digital form. It remains to this day a magnificent fragment.

In other words, to paraphrase King's own motto: "Trust the tale, not the one who tells it." If you do decide to read Boochani's tale, you'll immediately notice a few things about it:

First of all, it's very 'poetically' written. In other words, the prose passages are interspersed with more focussed passages of free verse. What precisely this echoes in the original text, it's hard to say, but it's certainly very effective in English.

Secondly, Boochani has the soul of a novelist, as well as that of a poet. His character studies are brilliantly biting and witty.

Thirdly (and perhaps least palatably for many readers), he is an intellectual of the deepest water: prepared to argue theoretical definitions of oppression and perception to the n-th degree. Principal among the concepts he uses is that of Kyriarchy.

Anthony Haden-Guest: The Resistance to Theory

To my deep shame, I have to confess that this term did not immediately ring a bell with me. Now, of course, I've googled it and am getting ready to sound like I knew what it meant all along. But no, don't believe me. I didn't.

Or rather, I thought I didn't ...

•

Countdown Supermarket (Mairangi Bay)

Since it was first built in the 1970s, we've been living next door to a supermarket which started out as a SuperValue, then became a Woolworths, and is now a Countdown. Originally it had two entrances, one at the back and one at the front, but at a certain point, a couple of decades ago now, they decided to make the back carpark a loading area.

This didn't stop us walking through there. Once or twice it was necessary to dodge the front-end loader, but I never heard of any accidents or problems with that (though cars were only allowed through when no unloading was taking place).

Last Christmas we were rolling a trolley full of goodies towards the loading area when a young uniformed fellow started shouting at us. "You can't go through there," he said. The fact that we claimed to have been doing so for years did not sway him. We were forced, instead, to take the long way round and roll the trolley back through the rest of the shopping centre.

Alas, this was an augury of things to come. We continued to walk through, but we could see the signs of construction work beginning. Eventually this culminated in a pair of gates, at either end of the loading zone, which have made it impossible for anyone without a key to get in or out.

Film historian Marc Wanamaker at the gates of Hogan's Heroes

These were not just any gates: they were topped with barbed wire, padlocked and chained, and surrounded on all sides by extra razor-wire extensions to stop anyone trying to slip in or out unobserved. If you imagine something like the prison camp in that old TV series Hogan's Heroes , that should give you the general idea.

Nor is the process of getting them open and shut a trouble-free one. We frequently see lines of trucks stalled in the alley leading up to the first gate, honking their horns and cursing the absence of anyone to let in and unload their goods.

The gates at the other end, however, are even worse. They were wrongly balanced to start with, and could not be closed without immense effort and much cursing. Eventually they just left them open most of the time, until they could be removed and an entirely new set of gates installed.

To what end, exactly? The one thing they didn't try, over all the years we roamed freely through this loading zone, was a sign to the effect that people shouldn't walk through there - "for health and safety reasons." There's a sign there to that effect now, but given the simultaneous presence of the barbed wire and padlocks, it's not really necessary any longer.

I can see that the job of manning the loading area has become at least fifty percent more onerous since the great gates were installed. They have to be opened and closed, with much ceremony, many times a day - the truck drivers clearly hate them, and so (one suspects) do the supermarket staff. Sometimes I've been inside buying groceries when the call comes over the tannoy: "So-and-so to the loading area," generally accompanied by loud honkings and shoutings from outside.

The analogy may seem a trivial one, but this is the best I can come up with as a running definition of kyriarchy: a completely unnecessary set of extra rules and regulations, reinforced by physical barriers and new holding areas, which transforms lives by adding an extra level of inconvenience and time-wasting, on order to achieve a very debatable end.

Why didn't they try asking us not to walk through? It might not have worked, but putting up a couple of signs to that effect would surely have been easier than going the full nine yards with the locks and the razor wire?

The idea that there's nothing accidental in such decisions, whether they concern the detention structures on Manus Island, the roads and barriers around West Bank settlements in the Middle East, or the management structures in large institutions, is (as I understand it) the idea behind this theoretical construct:

Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza (2008)

In feminist theory, kyriarchy ... is a social system or set of connecting social systems built around domination, oppression, and submission. The word was coined by Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza in 1992 to describe her theory of interconnected, interacting, and self-extending systems of domination and submission, in which a single individual might be oppressed in some relationships and privileged in others. It is an intersectional extension of the idea of patriarchy beyond gender. Kyriarchy encompasses sexism, racism, ableism, homophobia, transphobia, classism, xenophobia, economic injustice, prison-industrial complex, colonialism, militarism, ethnocentrism, anthropocentrism, speciesism and other forms of dominating hierarchies in which the subordination of one person or group to another is internalized and institutionalized.Once you start looking for it, you spot it everywhere. They just announced the introduction of a new scale of parking charges at work, without any consultation with staff, just after we'd finished a long set of negotiations over pay and conditions with them through our Union delegates. Merry Christmas to you, in other words - don't think you can get us because we'll get you.

Wikipedia

Is kyriarchy too large and all-encompassing a concept to be useful for critical analysis of these structures? Not really. The point is to try and encompass the protean slipperiness with which power structures adapt themselves to each new change to the status quo.

I wish Behrouz Boochani well, and think his book a narrative masterpiece, but I think he would be the first to say that this is the beginning, not the end, of the conversation. The mere existence of places such as Manus Island raises uncomfortable questions. If we fail to see them as the extension of the petty power structures all around us designed - with more or less success - to keep us in line, then we've missed the whole thrust of his argument.

Manus Island Detention Centre (2018)

Published on December 08, 2019 13:30

November 22, 2019

The King in Yellow

Michael Cimino, dir. & writ.: Heaven's Gate (1980)

"Heaven's Gate - like the movie?"

- Elizabeth Knox, The Absolute Book

(Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2019): 217

Elizabeth Knox: The Absolute Book (2019)

[WARNING: this post contains significant plot spoilers - proceed no further unless you don't care about such things, or are not actually intending to read the book]:One of the most interesting lapses in Elizabeth Knox's latest novel The Absolute Book comes quite early on, where her heroine Taryn Cornick is discoursing learnedly to an M.I.5. spook:

"... The Necronomicon is a fictional forbidden book, like M. R. James's Tractate Middoth or Robert Chambers' Yellow Sign. Someone handing me a card with Abdul Alhazred on it would mean to say: 'I am the master of forbidden knowledge'." [76]

Abdul Alhazred: The Necronomicon

Alas, not so. Mind you, H. P. Lovecraft's imaginary Necronomicon, ostensibly composed by the "mad Arab Abdul Alhazred" is indeed precisely what Taryn claims, but M. R. James's allegedly "forbidden" book is not. It is, rather, a perfectly respectable and well-known portion of the Jewish Talmud, as a few minutes of online searching should have revealed:

Dalia Marx: Tractates Tamid, Middot and Qinnim: A Feminist Commentary (2013)

Tractate Middot (Hebrew: מִדּוֹת, lit. "Measurements") is the tenth tractate of Seder Kodashim ("Order of Holies") of the Mishnah and of the Talmud. This tractate describes the dimensions and the arrangement of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, and the Second Temple buildings and courtyards, various gates, the altar of sacrifice and its surroundings, and the places where the Priests and Levites kept watch in the Temple.

- Wikipedia

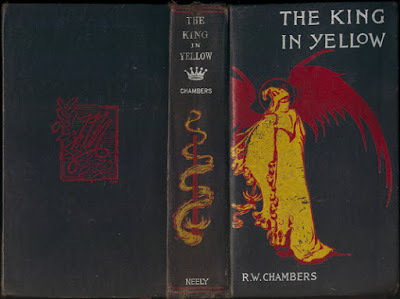

Robert W. Chambers: The King in Yellow (1895)

The Robert W. Chambers error is more interesting - and possibly more revealing. The book in question is not called The Yellow Sign but The King in Yellow .

It's notorious among fans of supernatural fiction not so much for the quality of its prose, which is fairly standard 1890-ish Wardour Street tushery, but for the sheer force of the idea behind it. Each of the first four stories references The King in Yellow, a "forbidden play which induces despair or madness in those who read it."

Aaron Vanek, dir.: The Yellow Sign (2001)

It's true that one of those four stories is entitled "The Yellow Sign." More to the point, though, The Yellow Sign was the name of a 2001 movie based on Chambers' stories, made by indie film director Aaron Vanek.

The idea of the literally unreadable book has been used many, many times since - perhaps most amusingly by Martin Amis in his 1995 novel The Information, where his writer protagonist's novel Untitled - "No, it's not untitled, that's the book's name: Untitled," as he is forced to explain again and again throughout the narrative - causes nosebleeds, nausea and even brain tumours in anyone who attempts to read it.

Dan Gilroy, writ. & dir.: Velvet Buzzsaw (2019)

Another, more recent twist on the idea can be found in the netflix movie Velvet Buzzsaw where an unscrupulous art critic (played by Jake Gyllenhaal) is destroyed by a set of paintings he has connived in stealing from a dead artist's apartment. Unsurprisingly, various references to The King in Yellow can be seen in the paintings themselves.

Elizabeth Knox

At first sight there do seem to be an unusual number of simple errors of nomenclature in Knox's book. For instance, when describing a large public sculpture outside a library in Aix-en-Provence which the heroine is visiting, she says:

Three giant-sized books had been reproduced in enamelled steel ... In order, they were The Little Prince, leaning; Molière's Les Malades in the middle; and Camus's The Stranger, which was nearest to Taryn. [89]Why are two of the titles in English, and the other one in French? More to the point, though, what's this "Molière's Les Malades" when it's at home? Molière did indeed write a play called Le Malade imaginaire [The Imaginary Invalid, or - if you prefer - the Hypochondriac] - it was, in fact, his very last work for the stage - but he never wrote one called Les Malades.

Honoré Daumier: Le Malade imaginaire (c.1860)

Again, further down:

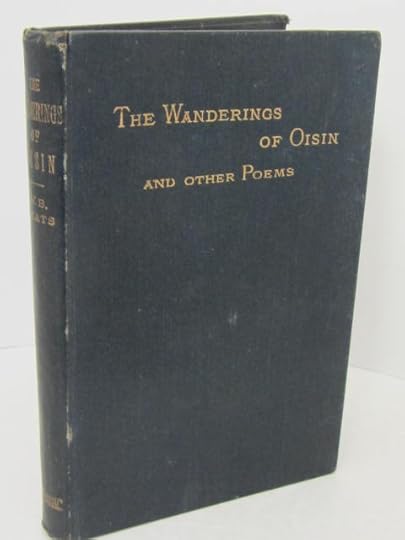

According to folktales, and later literary productions, the fairy took pretty children, like the boy Oberon and Titania squabble over in A Midsummer Night's Dream. They stole away bards like Yeats's Ossian, or beautiful knights like Tamlin. [243]Yeat's bard is named Oisin [pronounced Osheen], not Ossian. It's true that Ossian is a legitimate variant of the name - the one used by in his series of eighteenth-century epic poems adapted from the Gaelic, in fact - but Yeats's 1889 poem is called The Wanderings of Oisin (though in later editions he occasionally spelt the name 'Usheen' - perhaps for easier pronunciation). A small lapse, admittedly, but one which would definitely lose you the point in Mastermind or Who Wants to be a Millionaire?

W. B. Yeats: The Wanderings of Oisin and Other Poems (1889)

Yet again, still further down, in a discussion of the disposition of the family library on which so much of the plot hinges:

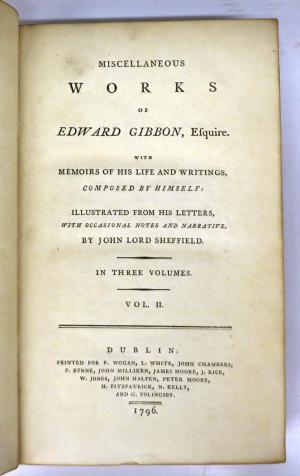

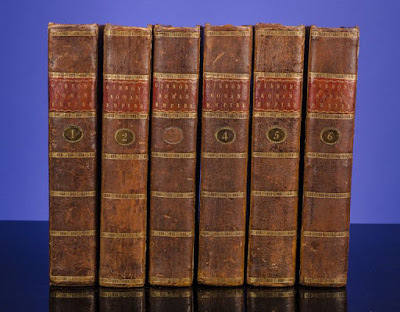

'There were quite a few things your grandad packed up himself. With personal notes. ... And there were one or two large crated consignments of books, like his whole set of Gibbon. [547]'Like his whole set of Gibbon.' Huh? Wha ...? Edward Gibbon's great work on The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire first appeared in six volumes between 1776 and 1789. Subsequent reprints have sometimes swelled this to seven or eight volumes, but seldom more than that. As for his other miscellaneous works, the most compendious (Swiss) edition of these ran to seven octavo (i.e. small) volumes (1796), but the more standard English edition of 1814 is in five volumes.

Edward Gibbon: Miscellaneous Works (3 vols: 1796)

Would you really need a separate crate for eleven books? Taryn's grandfather may, of course, have been a mad Gibbonian who collected innumerable different versions and reprints, but in that case why is the reference to his 'whole set of Gibbon' rather than his many, many copies of the same book?

I guess the problem here is that if you're not really familiar with his work, the mere fact that Gibbon is a classical historian famous for his verbosity and longwindedness ('Another damn'd thick, square book! Always, scribble, scribble, scribble! Eh! Mr. Gibbon?', as the Duke of Leicester reportedly remarked when presented with volume one of his long-awaited history) might lead you to suppose that his collected works would reach quite a bulk.

They do not. Gibbon is in fact the most terse and pithy of writers, with sentences packed to hold the utmost possible meaning.

Edward Gibbon: The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1788-89)

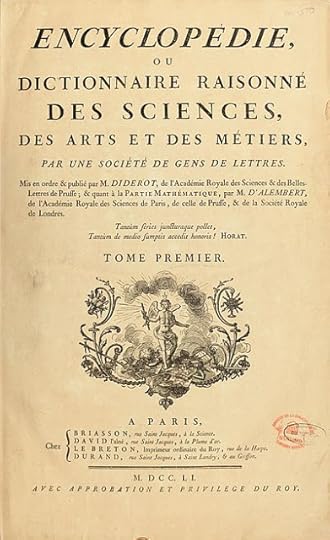

A much better choice here would have been one of his more prolific contemporaries, such as Voltaire, the most recent edition of whose collected works runs to 144 volumes. He might well merit a packing case to himself. Or, for that matter, Diderot, whose Encyclopédie (1751-80) fills 35 huge volumes. As the Encyclopédie Méthodique (1782-1832), it was eventually expanded to 166.

Denis Diderot, ed.: Encyclopédie (28 vols: 1751-66)

We are left, then, with two alternatives - either the author (and editor) of The Absolute Book didn't bother to check any of the bibliographical 'facts' it contains, but instead decided to rely on the by-guess-and-by-God system of literary divination. Or, alternatively, that early reference to 'The Yellow Sign' is meant as a code for a system of hidden correspondences underlying this book, also.

Perhaps (I'm guessing here), as with the Navaho, intentional errors had to be inserted to stop the book starting to ... operate upon its readers?

Stranger things happen in the plot itself, after all: we've hardly got stably located in one world than we're dashing off to another - Fairyland, Purgatory, Auckland - you name it.

Perhaps, too, the long (and rather irrelevant) description of a celebrated session at the 2016 Auckland Writers' festival, is meant as a part of this coding. That conversation hinged on the subject of saffron (I know because I was there).

Paul Muldoon (2016)

Basically, the person she refers to as 'the Irish poet' (Paul Muldoon) was being interviewed - or, rather, subjected to a long rambling monologue - by C.K. Stead, who (in his defence) had been roped in at the last minute to replace Bill Manhire, who was ill. They somehow got onto the subject of saffron - "You mean, what I use to colour my rice?" observed Stead hopefully - and Muldoon claimed he could write a whole book about it, like "those books about salt, or coffee, or cod" [315].

Unfortunately this roused the ire of a young man in the audience who trooped down to the microphone at the front of the auditorium to ask a rather long and involved question:

"... the guy said he read feminist poetry, and poetry by people of colour, and trans people. Poetry with politics in it. How he made a point of doing that. And then he said, 'I haven't read your books and I might find they're full of beautiful poetry, but where is it coming from?'" [316]Renee Liang's account of the event, posted at the time on The Big Idea, was somewhat different:

In One Thousand Things Worth Knowing, after the title of [his] most recent collection, Irish-US poet Paul Muldoon was interviewed by ‘last minute ring in’ CK Stead. Muldoon kicked off the session by announcing that Stead’s The New Poetic had profoundly influenced him as a young poet. The two old acquaintances then had a leisurely chat, seemingly forgetting the hundreds watching [my emphasis]. Muldoon on writing poetry with a jolt factor: “If I know what I’m doing, it’s almost certain everyone else will too. If I write what I don’t know, I might have the element of surprise.” He and Stead wandered gently around the subject of poetry, with seemingly unrelated side trips: “Now, saffron. You could write about saffron forever.”

Things became more lively when, with 20 minutes to go, Muldoon asked for the lights to be brought up on the audience. “Ah, there you are. You must have some things to ask?” Up first, a young man with a challenge: “I’m young, gay and Irish. Why are you talking about saffron? If you have that talent – do you not have a responsibility to use it?” Muldoon gently admonished him. “Subject matter is irrelevant. Any subject in the world could be illuminated through the prism of saffron. Or tea, for that matter. Now, a cup of tea is not a simple thing – it carries so much weight of history. Look at all the trouble tea caused in Boston Harbour.” It was hard not to admire a man who can turn anything into a metaphor ...

Bertrand Russell (1872-1970)

It reminds me a bit of that old anecdote about the London cabbie: "I have lots of famous people in my cab. The other day I had Bertrand Russell in there. The philosopher. And I said to him, 'Well then, Bertie, what's it all about?' And, d'you know, he didn't have an answer!"

Knox's account of the event concludes with a few bitchy put-downs of the PC young man, and some vaunting of the poet's 'gentle reply', with a suggestion that the whole thing could have been settled by asking, 'Excuse me, is there a question in your question?' [316].

Perhaps that's a stock author's perspective - motivated principally by the fear of getting just such a grilling oneself. Renee concludes with some oblique praise of Muldoon's ability to 'contort time' - and a suggestion that if he were a working mum, he might find it a bit harder to contemplate saffron in such a leisurely way.

For myself, I guess that the whole thing was just a huge disappointment. I adore Muldoon's poetry (which, unlike - I suspect - most of the other commentators, I have read, and taught, and discussed, at length). All this bullshit about saffron was so far from what I wanted to hear from the author of 'The More a Man Has the More a Man Wants’ or 'Incantata' that I found myself resenting most of all the conference organisers' decision to pair him off in a 'conversation' rather than simply letting him read. But perhaps I'm the one going off at a tangent now ...

So what (if anything) links all of these things?

Robert W. Chambers: The King in Yellow: Annotated Edition

Forbidden books (or works of art): - In this case, a book such as The King in Yellow, deliberately misnamed (or should I say misleadingly named) to draw the attentive reader.

Sickness (or disease generally): - This takes the form of Molière's Les Malades [the sick people] - an obvious distortion of the title Le Malade imaginaire to stress the fact that this particular malady is far from imaginary:

In 1673, during a production of his final play, The Imaginary Invalid, Molière, who suffered from pulmonary tuberculosis, was seized by a coughing fit and a haemorrhage while playing the hypochondriac Argan. He finished the performance but collapsed again and died a few hours later.Poetry (or bardic verse): - This is underlined by reference to the abducted Fenian bard Oisin (or Usheen, or Ossian) - clearly misnamed, despite the fact that this is one of best-known of Yeats's early poems.

- Wikipedia

Size (or number): This arises from that passing reference to the bulk - or, in this case, otherwise - of someone's 'whole set' of Edward Gibbons' works. But Gibbon did indeed propose the publication of a collected edition of the historical materials used by him in reconstructing the history of Europe during the late Roman Empire, the Byzantine period and the Dark Ages. If Taryn's grandfather had access to Gibbon's list of works - or had taken the initiative to compile such a monumental collection himself - that really might have occupied an entire packing-crate.

Geoffrey Keynes: Edward Gibbon's Library (1940)

One could perhaps summarise as follows:

MadnessDiseaseAbductionSize

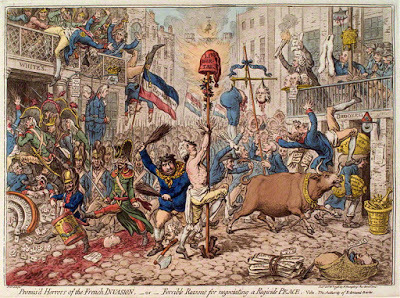

James Gillray: The Promis’d Horrors of the French Invasion (1796)

All in all, it sounds to me rather like a warning of some kind. I also note, parenthetically, the tendency of each of these works to group in the fin de siècle of each of the last few centuries: 1789 (the year of the French revolution) for Gibbon's Decline and Fall, 1889 and 1895 for (respectively) Yeats' and Chambers' books, 1673 for Molière's fatal last play ...

Burned Classical Scroll from Herculaneum

The ostensible subject (or should I say 'The MacGuffin'?) of Knox's work is a book referred to only as 'the firestarter', which is presumed to have been the cause of several of the most celebrated library fires in history. It takes the form of a sealed, almost indestructible box, which contains:

a scroll made from the skin of an angel. The skin is tattooed with words, in an ink made of the angel's own blood. The scroll is a primer of the tongues of angels, otherwise known as the Language of Command. A language which, like the language of the Sidhe, has no written form. The primer is ... in the Roman alphabet, with the phonetics of Latin used to approximate the sounds of the words of the language of Command [622-23]It also contains, we discover a bit later - after the original scroll has been used to buy off the demons who have been making trouble throughout most of the book - 'in Latin as well as the language of angels,' a letter from the mother of the character Shift, a minor god who plays a major part in the action of the book:

She apologises for all the deceptions she practised on me. And for hiding me. [632]"By virtue of its being the same text written in two languages, it is also a cipher key," comments Hugin, one of Odin's two ravens of wisdom, also an important character in the plot.

'The phonetics of Latin.' Well, even that is not quite so easy as it sounds. Anyone who's ever tried to learn Latin knows that it has at least two systems of pronunciation: The first is the established Continental system, used by the Catholic church, which roughly equates its sounds with those of a modern Romance language such as Italian.The second is the nineteenth-century British pronunciation which attempted to reconstruct the 'original' classical sounds of the letters by analogy with transliterations in other languages (such as Greek). Hence the infamous 'Wainy, Weedy, Weeky' sounding of Caesar's epigrammatic'Veni, Vidi, Vici' [I came, I saw, I conquered]. Hence, too, "Kikero" for "Cicero", and (of course) "Kaiser" for "Caesar."

What if you got it wrong? Surely a certain precision must be employed whilst intoning the sounds of this 'Language of Command'? Unless it's all a cunning plot on the original angel's part to make his scroll unusable by any but those previously initiated into his system of pronunciation?

Alan Garner: The Moon of Gomrath (1963)

In his author's note at the end of The Moon of Gomrath, Alan Garner remarks:

The spells are genuine (though incomplete: just in case)Are Knox's instructions to initiated readers similarly "incomplete: just in case"? It's tempting to think so. It's hard, therefore, to conjecture just what the final message of the book might be.

It certainly involves danger (The King in Yellow) - though what that danger is is not quite clear. Is it madness, as in Chambers' original play? Abduction to the Other Side, to Fairyland (or, if you prefer, Swedenborgian space) - like Yeats's Oisin? Is it death, as in Molière's own play?

Joseph Noel Paton: The Reconciliation of Titania and Oberon (1847)

It's just a suspicion, but I feel that the question of size is crucial here. Opnions differ on the precise dimensions of Faerie. Modern writers have poured scorn on the idea that Fairies are of diminutive size, with gossamer wings and diaphanous dresses. Another world might well be ruled by an entirely different set of dimensions, however. Oisin may well have shrunk when he followed his fairy princess to the three islands of Yeats's poem - "Vain gaiety, vain battle, vain repose" - even though he resumed his original giant-like dimensions on his return to St. Patrick's Ireland.

Enough said, perhaps. I cannot say message received, as that would be mendacious in the extreme, but certainly I remain poised for further communications from the other side. Size, yes, and saffron. That particular reddy-yellow spice comes up again and again, and is perhaps the most important ingredient to be gathered from this colourfully encoded work.

Persian Saffron

Published on November 22, 2019 14:01

November 14, 2019

Der Bau

Elias Canetti: Auto da Fé (1935)

Someone has stolen my copy of Auto da Fé, by Elias Canetti.

They did it in quite an ingenious way. I had it in a bookcase arranged with double rows of books on each shelf. The idea is that a quick scan of the books in front will enable you to guess what's concealed behind.

In this case, there were two Penguin paperbacks by Canetti - Crowds and Power and Auto da Fé - in the front row, and a group of his other books (including his four-volume autobiography) hidden behind.

What the thief did was to move one of the books from the back row to fill the gap in the front row, and thus conceal the fact that anything was missing from that shelf at all.

There's a certain irony in the fact that they chose that particular book to run off with. It's a novel about an obsessive scholar, Dr Peter Kien, who lives entirely in, and for, his library of rare books.

When I say he lives in his library, I mean just that. He moves his little portable bed and washstand from room to room, depending on what he happens to be working on at the time.

Elias Canetti: Die Blendung (1935)

The original German title of the book, Die Blendung, translates literally as 'the blinding.' His English translator, the well-known historian C. V. Wedgwood, chose to change this to Auto da Fé ['Act of Faith' - the name for the mass burnings of heretics conducted by the Spanish Inquisition], presumably because she thought that this might better convey the book's claustrophobic sense of entrapment and sacrifice.

Elias Canetti: Party in the Blitz: The English Years (2003)

The book my thief chose to move forward was a hardback edition of one of Canetti's last works: Party in the Blitz (2003). Once again, there's a certain irony in that, as the novel concludes with the protagonist's self-immolation on a heap of his own books (they've been stolen and sold on by his unscrupulous housekeeper-turned-wife and her louche accomplices, but then recovered and brought back to him by his rather saintly brother).

I imagine I'll succeed in finding another copy of Auto da Fé to fill the gap. That isn't really the point, though.

Any collector of anything has to face the paradox that the more things you have, the less control you have over each part of your collection. While you're gleefully filling gaps in your holdings of some particular author, the most precious volume of all may just have disappeared into somebody's pocket.

Nor do we all have similar ethical standards in such matters. I know plenty of people who regard it as quite unnecessary to return books they've borrowed, and in fact react most indignantly to anyone who tries to recover their own property - they seem to envisage some wondrous freemasonry of books, passing from hand to hand like lightning rods: albeit with the slight, disquieting, detail that it's generally someone else providing the raw material.

And certainly getting too obsessed with ownership can become a bit excessive. At one point, to combat my own tendencies in that direction, I formulated a theory that the only books which would available to one in the afterlife would be those which had been given away. I accordingly began a programme of donations which would guarantee my own future reading pleasure - on the offchance I don't end up in the burning place instead, that is.

The burning place. Elias Canetti's novel is certainly not meant as an endorsement of bibliomaniacs such as his Peter Kien - on the contrary, in fact - but his success in portraying one would certainly seem to show certain tendencies in that direction on his own part.

Perhaps the thief meant to do me a favour by running off with the book. Perhaps they thought it would be unhealthy for me to brood too much over the dark material included in it. And it's probably true that it will be a long time before I feel it necessary to read it again - though Canetti's autobiography, in particular, is a delight.

Franz Kafka: Der Bau (1924)

The other thing it made me think of, I'm afraid, was Kafka's great short story 'Der Bau' [The Burrow]. Written six months before his death, and published posthumously in 1931, it describes a large burrowing animal who has built a most marvellous underground structure which he is engaged in constantly improving.

Gradually he becomes aware of little piles of loose dirt, betokening the presence of some alien invader, which he tidies as best he can, but which continue to appear, threatening to undermine all the - illusory - grandeur of the dwelling he's built for himself. It's the rift within the lute, the maggot in his brain, the ideé fixe which will end up by destroying him.

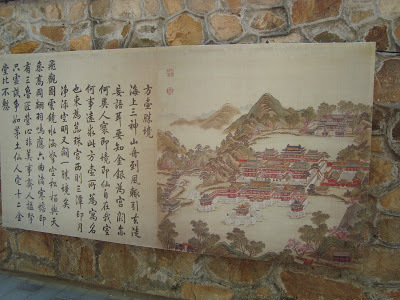

Donald A. Mackenzie: Teutonic Myth and Legend (1912)

I remember once, in a university class on the Old English epic Beowulf, suggesting that the dragon whose horde is invaded by the hero Beowulf towards the end of the poem might feel similarly about his own treasure chamber - that he might feel a deep sense of repulsion at the mere fact that an intruder has succeeded in invading his sanctuary.

I remember one of my classmates laughing at this: "I don't think he feels like the creature in Kafka, Jack."

'Why not?' I asked at the time. Why shouldn't he feel like that? The poet gives few clues to his feelings.

At present (Der Bau-like), I'm engaged in a large-scale project to map every one of the books in our house, and - in the process - adding protective covers to all the vulnerable hardbacks. I've also decided to write my name in each and every one of them, rather than reserving that for the more interesting acquisitions.

From now on there will be a small sign on the shelves in our guest space:

Feel free to read the books, but please be careful of them if you do.So if that bookthief was sending me a message about the perils of getting too attached to my collection, I'm afraid that I've chosen to ignore it.

Don't take anything away without asking. That will be regarded as theft.

Elias Canetti: Auto da Fé (English translation, 1946)

•

And, to show how thoroughly I've missed the point, here are my holdings of Elias Canetti, Franz Kafka, and - the poet.

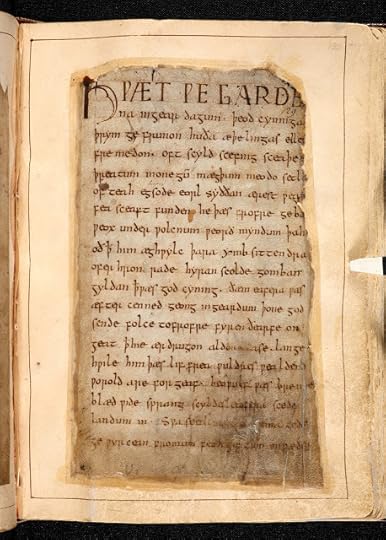

The Southwick Codex (c.1000)

Beowulf

(c.8th-early 11th century)

Editions:

Klaeber, Franz, ed. Beowulf and The Fight at Finnsburg. 1922. Third Edition with First and Second Supplements. Boston: D. C. Heath and Company, 1950.

Swanton, Michael, ed. Beowulf: A Glossed Text. Manchester Medieval Classics. Ed. G. L. Brook. Manchester: Manchester University Press / New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1978.

Alexander, Michael, ed. Beowulf: A Glossed Text. 1995. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2000.

Translations: