Jack Ross's Blog, page 20

May 9, 2019

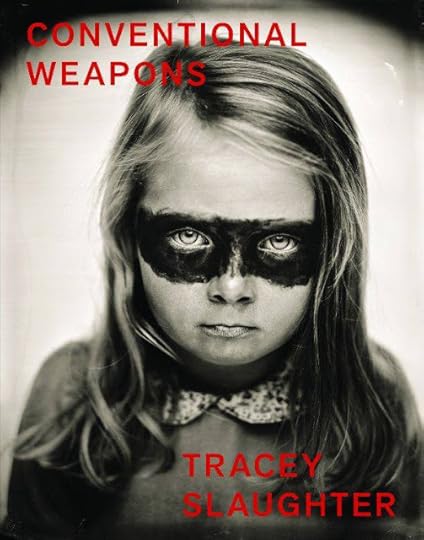

Tracey Slaughter: Conventional Weapons

Bronwyn Lloyd: Tracey & Jack (9-5-19)

So Bronwyn and I drove down last night, after my midday class, to attend Tracey's booklaunch in Hamilton. It was great! The crowd could hardly fit into the space - the refurbished Poppies Bookshop, one block back from Victoria Street - so they were gathering outside as well as in. The drink flowed free, and the catering was splendid.

Bronwyn Lloyd: Crowd Scene (9-5-19)

Here's my launch speech for the book (which - of course - doesn't begin to do it justice, but one must at least try to fix an impression):

Tracey Slaughter: Conventional Weapons (Wellington: VUP, 2019)

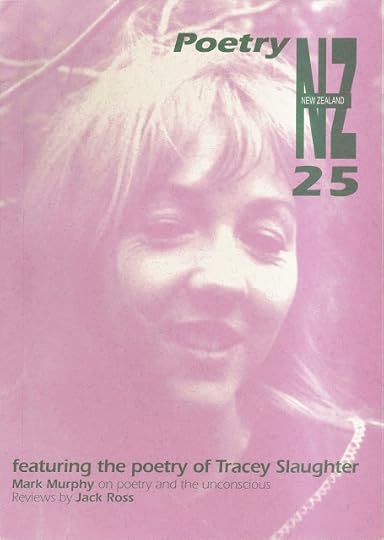

I think that the thing I’d like to stress to begin with is that I first knew Tracey as a poet, long before I knew about her short stories. It was, in fact, her feature in Poetry NZ 25 (2002), which really woke me up to her as a writer.

Poetry NZ 25 (2002)

Just reading the titles of those poems now is very evocative, I must say: “Lone Wolf goes to her Reunion”, “Anatomy of dancing with your Future Wife,” as well as the terrifying “Rules for Teachers (1915).”

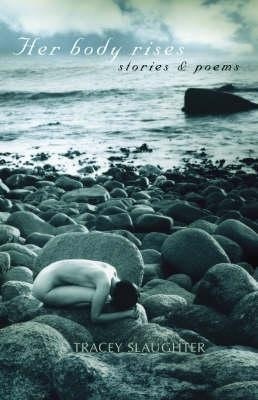

Nor do you have to hunt out old issues of Poetry NZ to see them, either. These – and many more – were included in her first book, the wonderful – and revelatory – Her body rises: stories & poems (2005).

Tracey Slaughter: Her body rises (Auckland: Random House, 2005)

Over the years I’ve been privileged to see a lot more of Tracey’s poems – as a friend, but particularly as an editor. She’s always been very generous to my requests for more material from her. One of the poems in the present book, Conventional Weapons, first appeared in my guest-issue of brief #50 (2014).

In fact, that whole issue was bookended by two long Tracey Slaughter poems, “31 reasons not to hear a heartbeat” at the beginning, and her fascinatingly disproportionate Victorian monologue “The Box of Phantoms” at the end. That one isn’t in this book, alas, but you can look it up in the issue.

brief 50 (2014)

So while it is technically true that this is Tracey’s first stand-alone poetry collection, it’s very misleading to see her as any kind of newcomer to the game. She’s been publishing poetry for more than two decades now, and it’s high time that we started to see her, like Raymond Carver, as someone equally adept at poetry and the short story.

But what kind of a poet is she? Words like ‘bodily,’ ‘visceral’, ‘grimy and dirty’ have frequently been used to characterise her work, and particularly these poems. There is a lot of sex in them. There’s also lot of desperation, pain, and sheer horror of the void. As Hera Lindsay Bird remarked on the dust jacket of another recent VUP book, Therese Lloyd’s The Facts, ‘it won’t make you feel better.’

But all that implies a kind of shock value: a quest for extremity for its own sake. But you have to read deeper and better than that if you want to begin to understand some of the many things Tracey is trying to do in these poems.

As always, she’s extremely, wonderfully literary. Mike Mathers’ Stuff article about this book states that: “If the collection had an overarching theme, it would be one of giving voice to a group of strong female characters of different ages.”

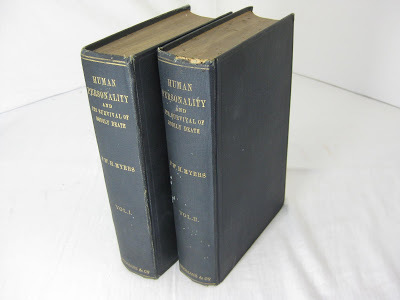

I mentioned before the long Victorian monologue in that old issue of brief magazine. In many ways this collection is a tip of the hat to Robert Browning’s Dramatis Personae (1864): to his idea of embodying complex and subtle character portraits in dramatic monologues – a precedent followed by his disciple Ezra Pound in Personae (1909).

It’s a mistake to think that poets are mostly concerned with self-revelation, leaving fiction writers to concern themselves with the delineation and analysis of character. Perhaps, in fact, it’s Robert’s wife Elizabeth Barrett Browning who’s the stronger influence here: particularly her wonderfully rich and complex verse novel Aurora Leigh (1856).

Federico Garcia Lorca (1898-1936)

Tracey understood long since that to be a good writer you also have to be an insightful reader, and I was particularly delighted to hear the echoes of Federico Garcia Lorca’s great ‘Lament for Ignacio Sanchez Mejias,’ with its repeated refrain of ‘a las cinco de la tarde’ [at five in the afternoon] in her own poem ‘breather’ (shortlisted for the 2018 International Peter Porter Poetry Prize).

Here’s Lorca:A coffin on wheels is his bedHere’s Tracey:

at five in the afternoon.

Bones and flutes resound in his ears

at five in the afternoon.

Now the bull was bellowing through his forehead

at five in the afternoon.

The room was iridescent with agony

at five in the afternoon.

Call your wife, leave a message at the sob. Call your wife, she is learning the hard way. Call your wife, the histology is back. Call your wife, her lipstick is audible. Call your wife, she’s on her third bottle & the kids are starting to look like stars. Call your wife, she remembers the colour of the wallpaper in neonatal. Call your wife, she is talking to you with her head tipped back so you don’t hear the asphyxia. [83]It’s not that Tracey is imitating Lorca’s heart-broken lament for his doomed friend, the dead bullfighter, but she certainly seems to be channelling it somehow. The love trysts in cheap hotels which occur so often in this collection of poems have become a kind of underlying motif or background music, like Lorca’s Andalusian folk traditions and gypsy ballads.

The mention of music brings me to another major theme in Tracey’s work. She is herself an accomplished rock & roll drummer, and has performed for many years as the lead singer in a local covers band. In fact one of the original titles for this book was ‘Covers’ – which does tend to confirm that the complex relations between poetry and music are never very far away for her.

If Lorca, and all he represents, constitutes one pole of her inspiration, then, the sad, frail, whip-thin and radioactively talented Karen Carpenter might be said to embody the other.

Karen Carpenter (1950-1983)

Her long sequence ‘it was the seventies when me & Karen Carpenter hung out’, which covers almost twenty pages of the book, underlines this relationship in all its dangerous, flamboyant glamour. KC, or Kace, was a drummer like Tracey. Like Tracey she fought the pressure to come out from behind her drums. Unlike Tracey, she gave in.

A single review mentioning the word ‘plump’ was enough to set off the nightmarish anorexia which eventually took the star’s life – and it’s that aspect that Tracey’s narrator in the poem explores in all its painful detail. Painful, yes, but also funny with a kind of gallows humour:the feetSo, while I do continue to hear Lorca’s immortal elegy when I read Tracey Slaughter, I also hear Karen Carpenter’s late, great song ‘Calling Occupants of Interplanetary Craft’ – or rather, see the video for that song, with KC’s eyes bugging out of her face, and the jumpsuit emphasising every absent curve.

of me & KC

glue our dreams

like trophies

to the cork-tile

kitchen. When we get

there the cupboards bulge

with Instants

bright in their toxic

brands. Our

tongues are caked

with calories, all for

our mothers’

convenience. You can

just get so lovesick

for puke. [53]

If life wasn’t like that – if young girls didn’t set out to starve themselves to death in the name of a false image of perfection; if desperate souls didn’t get themselves fucked in anonymous hotel rooms in random acts of adultery, then it might not be necessary to write about it.

Tracey has the courage to do so. More importantly, she also has the skill and the depth of poetic knowledge to write it in such a way that we have to go back to her poems again and again to tease out their corners, work out the angles, learn – each time – a little more about the sheer strangeness and beauty of human beings. Buy this book. You won’t regret it.

Tracey Slaughter

Published on May 09, 2019 15:43

April 27, 2019

The Mysteries of Rotorua

List of Strange Occurrences

(Unless otherwise noted, all photographs by Bronwyn Lloyd: 24-26/4/19)

Bronwyn and I had a very mysterious time of it on our recent excursion to Rotorua. This was not intended as a ghost-hunting expedition, but it certainly ended up that way. We seemed to be plagued the whole time by strange portents and coincidences ...

Bonze

Here's the first (and mildest) of them. If you look carefully at the car above, you can see the word 'Bonze' written on the back. 'Bonze' happens to be Bronwyn's childhood nickname (as well, of course, as an old name for a Buddhist priest).

Bonze (detail)

Our plan was to drive down via Cambridge, as we'd heard from a friend that there was a good antique shop there, with lots of books and other treasures. The shop, Colonial Heritage Antiques was located at 40 Duke Street. Unfortunately google maps interpreted this as Duke St, Frankton (just outside Hamilton), so led us on a wild goose chase through the city.

Nothing daunted, we drove on towards Cambridge:

Jack outside Cambridge shop

Here I am outside Colonial Heritage Antiques (and, yes, I did pick up one or two books in there). You'll notice the strange orb-like illumination in the middle of my forehead.

Jack with orb

I've included this detail of the shot to emphasise that this seems to me a fairly normal visual phenomenon - not at all like the one further down in this post ...

Cambridge tree

We spent a pleasant evening in Rotorua on arrival there. Only one slightly strange thing happened. As we were sitting in the restaurant waiting for our meal, a woman came up to us and told Bronwyn what a lovely smile she had, and how it 'lit up the room.'

This was very nice of her, of course, but the point is that it has never happened before, and - but you'll have to wait for further comments on this event below.

Taniwha

We decided to do some sightseeing among the lakes, and stopped to take this rather suggestive shot of Lake Rotoiti as we were driving alongside it.

As she got out of the car, Bronwyn remarked on the little buoy visible in the picture, claiming that it looked like a taniwha, and could easily be made into a picture of Nessie or some other lake monster.

At that moment a motorboat roared by towing a water skier, and I said that if we waited for the wake to reach the buoy, it would look as if the little dark object was causing the waves.

Glade beside Lake Rotoiti

Now I'd like you to look at the picture above very carefully. It was taken a moment after we noticed the bones.

I'd seen that there was a small stack of bones beside one of the trees when we arrived at the rest area (more of a pulling-over place, really). Now I began to see that they were quite large leg bones, and had definitely been gnawed by someone or something.

Bronwyn was standing a bit higher to take her shot, and she said that she could see a large ribcage, with some bits of fur and meat on it. It was much larger than a sheep's. We wondered if it might be a cow, or even a deer? It was about now that we were hit by the smell.

Glade with orb

Bronwyn was reluctant to photograph the bones themselves. A slight feeling of wrongness was already in the air for both of us. We felt like intruders in this place of death, and felt a definite anxiety to get away. It wasn't until much later in the day that we noticed the orb at the bottom of the photo.

Glade (detail)

So what is an orb, exactly? Anyone who's ever watched any ghost shows on TV will be familiar with these small visible disturbances on video and still photographic images.

Sceptics claim these are due solely to backscatter and other natural side-effects of photographic flash. Believers see them as the earliest intimation of an apparition or presence.

Certainly it's a little odd that this is the only one we've ever recorded (discounting the one above, outside the Cambridge shop), and that it was taken in one of the creepiest places we've been to.

Orb (detail)

If you look at it closely, it really is quite an odd thing. It looks almost as if something was trying to come through the picture at that moment.

At first we thought that someone might have stopped for a barbecue or a midnight feast at the spot, but there were no signs of fire, and the bones had definitely been chewed by teeth.

Green Lake

Here's another shot of the green lake, Rotokakahi, a bit further down the road. As you can see, there's nothing odd in the shot - though we did almost get taken out by one of the incredibly aggressive local drivers who was tailgating me at the time.

It was almost, at times, as if they wanted to run us off the road, rather than simply to let us pull over and allow them to pass ...

Whakatane & White Island

Having gone so far, we decided to head on to the coast and check out Whakatane. Here's a shot from a little jetty and children's playground along the foreshore.

What it doesn't show is the omnipresent plague of wasps. Nobody else seemed to notice or react to them at all, but the moment we pulled up, they were buzzing around us, and (seemingly) trying to get into the car with us.

White Island (detail)

We decided instead to drive a bit further along the coast and check out what's billed locally as "NZ's favourite beach", Ohope.

Ohope 1

Here's the view looking north.

Ohope 2

And here's the view looking south.

Once again, the camera hasn't picked up the ubiquitous wasps. We rejected the idea of stopping for a coffee, and instead headed back to the big smoke, Rotorua.

On the way back we were looking out for the place where we'd seen those strange bones. Sure enough, just before we reached it, a black cat ran out across the road in front of us (narrowly avoiding a collision with the car in front). I know that that's good luck in some places, but it's bad luck in others.

Perhaps he was the one who'd been gnawing at them so assiduously.

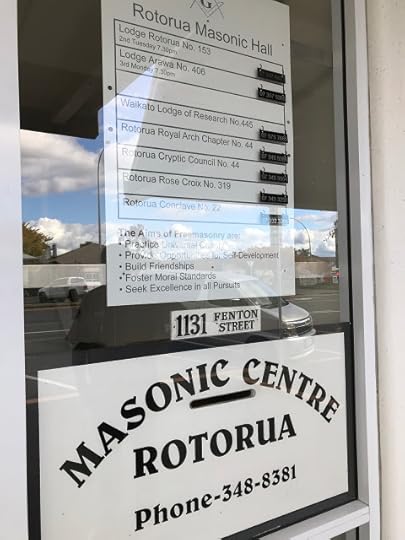

Freemasons 1

Everything was closed in Rotorua. True, it was Anzac Day, but we'd hoped that a few shops might open in the afternoon, as they do elsewhere. No such luck. In particular, Atlantis Books, which I'd hoped to scope out, was clearly closed for the day.

Which brings me to another curious incident. Before leaving Whakatane, we saw online that there was a branch of Atlantis Books located there. We followed the directions, and got to the listed address, only to find - nothing.

For the second time in two days, our Australian-accented guide at google maps (whom we've nicknamed Kylie) had led us wrong. But she's hardly ever done so before - and never in so significant and patterned a way.

Freemasons 2

The blank spot in this sign could be deciphered as once having advertised a'Geyserland Daylight Lodge'. I wonder just why it closed, and why all evidence of it had to be scrubbed out in this way?

Freemasons 3

With no shops open, we continued to wander. But Bronwyn had already fallen and skinned her knee when we set out to get some lunch, so we couldn't go too far.

There was a tiny pebble on the footpath which we concluded must have been the culprit - but really, it was as if she'd been pushed over by somebody, she went down so fast and hard.

The Government Gardens

The gardens were (and are) somewhat spooky - even in the daytime. They're surrounded by lake weed and boiling mud pools, and seem as if they're only precariously maintaining their place on the foreshore.

The animate tree

And some of the trees look positively alive.

The split tree

Though it's hard to see how this one continues to survive.

Inside the gap

What's lurking in there, I wonder?

Atlantis Books

Next day we duly went along to Atlantis Books, and had a high old time. As I was buying a stack of books at the counter, though, the owner asked me if I was in the trade?

'No, just a bibliophile,' I replied. 'I do teach literature, though.'

'At Massey?' he asked.

'Yes."

"Aren't you a poet?'

'Yes.' (That doesn't happen very often - getting spotted).

'I was looking at your picture online last night!'

'What do you mean?'

'I've been thinking of doing some more study, and I was checking out the Massey website. And I saw you there.'

Just a coincidence, of course (and a very pleasant one), but there did seem to have been an awful lot of coincidences over the past couple of days. First someone came up and complimented Brownyn, and now someone claimed to recognise me from the internet ...

I don't know how familiar most of you are with Jung's theory of Synchronicity. Wikipedia defines it as:

a concept, first introduced by analytical psychologist Carl Jung, which holds that events are "meaningful coincidences" if they occur with no causal relationship yet seem to be meaningfully related.Let's look a bit more carefully at our two days in and about Rotorua, at the heart of that mysterious region where not only thermal phenomena but pyschic ones, too, seem so close to the surface of things - a place of strange portals and openings into other realms:

Two abortive bookshop searches (Hamilton & Whakatane)Two orbs (Cambridge & Lake Rotoiti): one fairly 'natural', the other far less soTwo strange encounters at the site of those bones (orb & black cat)Two wasp encounters (Whakatane & Ohope)Two recognitions (Fat Dog Restaurant & Atlantis Books)

Then there's the fact that I was sure I'd seen a shadowy figure in the corner of our room the first night, while Bronwyn felt that I'd taken off my shirt in the middle of the night (I can't have done, though because it was on next morning). Was there someone else lying there in my place at some point?

For what it's worth, I feel a kind of a shadow came down over the day after we'd pulled over - and talked so frivolously and cheekily about 'taniwhas' and monsters - at that strange death-site. It was almost as if there were a tapu over the place, which we'd inadvertently offended against.

I hope that we worked it off in the course of the day. By next morning, everything seemed lighter, somehow. And our intentions were perfectly innocent. I'll be watching out for wasps and sudden falls over the next wee while, though.

And I'd counsel in general showing a certain respect in that area of the North Island. It is a genuinely strange place, and the superficial overlay of tourist sites has not really touched its atmosphere of old bloodshed and restless ghosts.

'NZ's Favourite Beach'

Published on April 27, 2019 16:33

March 29, 2019

Geoffrey Trease: from the 5-Year Plan to Bannerdale

Dawn of the Unread (1909-1998)

It's rather a strange story, really. In 1933 a young man called Geoffrey Trease came across a book called Moscow has a Plan, in which (as wikipedia helpfully informs us):

a Soviet author dramatised the first Five-year plan for young readersDespite his bourgeois origins, Trease had rejected the class-based teaching he'd encountered during his first year of a Classics degree at Oxford, and had moved to London determined to find some other way of becoming a writer.

Now, inspired by the Russian book, he wrote a 'revisionist' children's book about Robin Hood entitled Bows against the Barons (1934), which not only included a left-wing political agenda, but also an unusual - for the time - emphasis on strong characters, both female and male, from a variety of social backgrounds, and an insistence on using contemporary rather than Wardour-Street ("Tush, varlet ... Gadzooks", etc.) English.

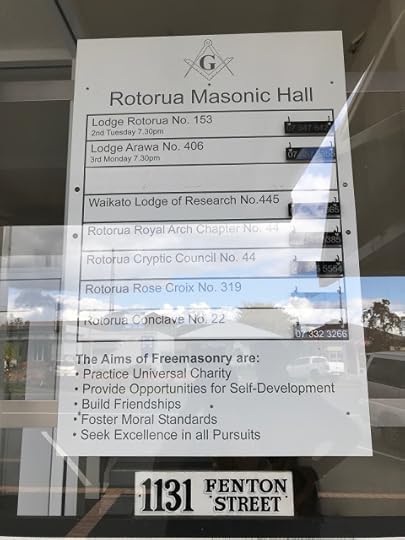

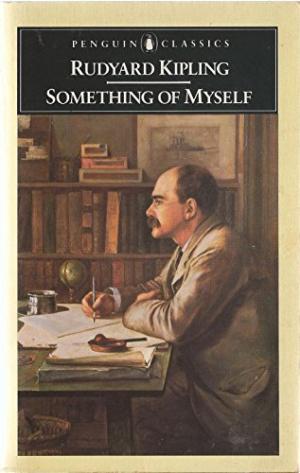

George Orwell on Geoffrey Trease

His specifically communist leanings may have faded over time (the great Stalinist purges of the 1930s were a bit of a disincentive to fellow travellers everywhere), but Geoffrey Trease remained throughout his career a strong proponent of progressive values - in distinct contrast to most of his predecessors (and many of his contemporaries) in children's writing.

Not that he was only a children's writer - or only a writer of historical fiction, for that matter. That was the field in which he achieved greatest distinction, but he also wrote adult novels, non-fiction (including three volumes of memoirs), and even literary criticism.

For more on all these subjects, I recommend his autobiography, the first two volumes of which I bought from a library throwing-out table a few years ago:

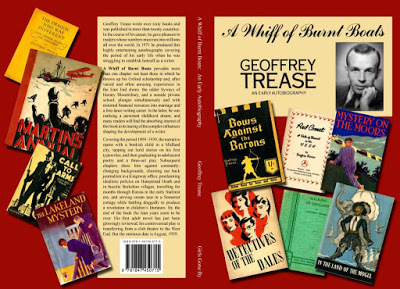

Geoffrey Trease: A Whiff of Burnt Boats (1971)

A Whiff of Burnt Boats: An Early Autobiography. St. Martin’s Press. London: Macmillan & Co., 1971.

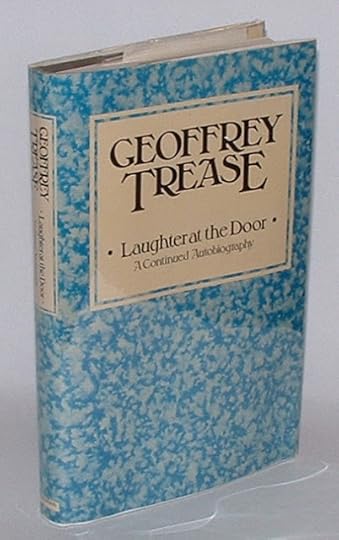

Geoffrey Trease: Laughter at the Door (1974)

Laughter at the Door: A Continued Autobiography. London: Macmillan London Ltd., 1974.Where my own interests come in is with his most famous series of books, the Bannerdale novels, which began with No Boats on Bannermere in 1949, and concluded with The Gates of Bannerdale in 1956. Here they are in order of publication (and chronological sequence):

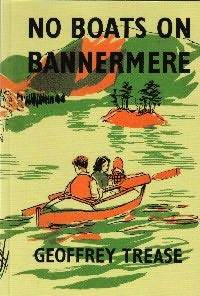

Richard Kennedy: cover for No Boats on Bannermere (1949)

No Boats on Bannermere. Illustrated by Richard Kennedy. Bannerdale series, 1. 1949. London: Heinemann, 1963.

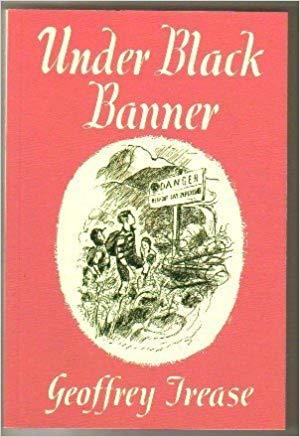

Geoffrey Trease: Under Black Banner (1951)

Under Black Banner. Illustrated by Richard Kennedy. Bannerdale series, 2. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1951.

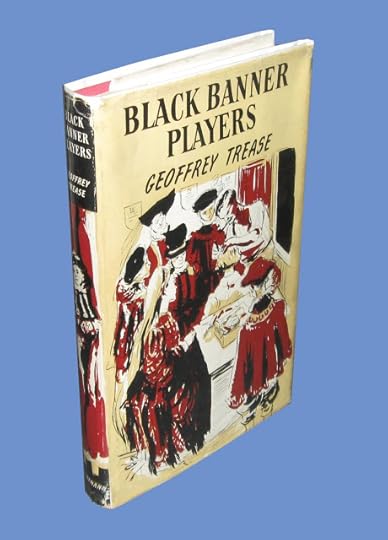

Geoffrey Trease: Black Banner Players (1952)

Black Banner Players. Illustrated by Richard Kennedy. Bannerdale series, 3. 1952. Coleford, Radstock, Somerset: Girls Gone By Publishers, 2005.

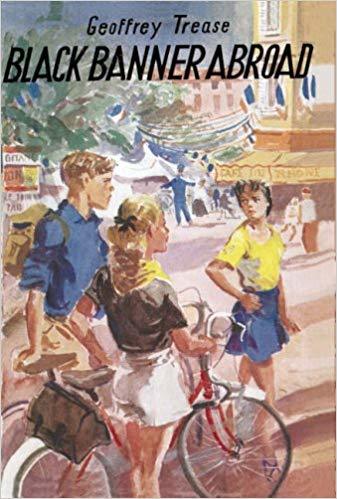

Geoffrey Trease: Black Banner Abroad (1954)

Black Banner Abroad. Bannerdale series, 4. 1954. The New Windmill Series. Ed. Anne & Ian Serraillier. London: Heinemann, 1962.

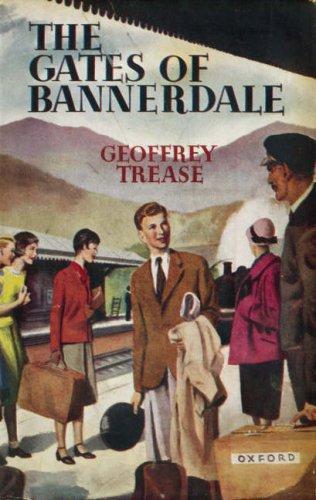

Geoffrey Trease: The Gates of Bannerdale (1956)

The Gates of Bannerdale. Bannerdale series, 5. 1956. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1965.

As a group, I suppose they were inspired mainly by Trease's own residence in the Lake District from the 1940s on. One can't, however, avoid the suspicion that they were also designed as a kind of antidote to an even more famous series of books, Arthur Ransome's 12 Swallows and Amazons books, set on an unnamed lake a little like Windermere, though with features borrowed from various other lakes nearby.

Arthur Ransome: Swallows and Amazons (1930)

Swallows and Amazons (1930)Swallowdale (1931)Peter Duck (1932)Winter Holiday (1933)Coot Club (1934)Pigeon Post (1936)We Didn't Mean to Go to Sea (1937)Secret Water (1939)The Big Six (1940)Missee Lee (1941)The Picts And The Martyrs: or Not Welcome At All (1943)Great Northern? (1947)

Arthur Ransome: Autobiography (1884-1967)

Ransome was by no means a reactionary. He had in fact been suspected of espionage for the Soviets at the time of the Revolution in 1917, and was close to Lenin and Trotsky at that time (he ended up marrying the latter's secretary, Evgenia Petrovna Shelepina). He made a valiant attempt to portray some working class characters in Coot Club and its various sequels, but for the most part his children do live in a kind of fairyland of complete behavioural licence and freedom from economic pressure.

When the children decide to go off and camp on an island in the middle of the lake in the first of the books, for instance, their father's telegram of permission famously reads: "BETTER DROWNED THAN DUFFERS IF NOT DUFFERS WON'T DROWN."

R. M. Ballantyne: The Coral Island (1858)

For Trease, they appear to have acted a little like R. M. Ballantyne's Coral Island did for William Golding's Lord of the Flies. The delightful (or irritating, depending on your point of view) lack of reality in the Swallows and Amazons books may have spurred him into wondering what it would be like if some child characters really did have to deal with modern life in a more-or-less unadorned form?

William Golding: Lord of the Flies (1954)

Which is not to say that No Boats on Bannermere (1949) is not an exciting adventure story. Published almost twenty years after the first of Ransome's Lake District romances, it also deals with a mysterious island, boating adventures, and a host of picturesque characters. The difference is that the children's mother is divorced, has to make money doing 'teas' for visitors, and that a basic pragmatism and verisimilitude underlies all their doings.

Lake Windermere

Trease has also learned that readers can be interested just as easily by the everyday details of life in a North Country cottage as by buried treasure or ancient skeletons. But he doesn't really stint on either. Seventy years after it was published, No Boats on Bannermere now gives an agreeably distant feeling of post-war Britain, complete with rationing, housing restrictions, and other - now fascinating - details of life in that era.

Its sequels go on to flesh out the picture with subjects such as the need to reclaim confiscated - but no longer needed - land from the War Office, the complex politics of local drama groups, the challenges of going abroad on limited funds, and - finally - the realities of life as a first year undergraduate.

In each case one feels that not only does Geoffrey Trease know exactly what he's talking about, but that the mechanics of such everyday dilemmas are, finally, far more interesting than - say - the fantasy worlds of Ransome's Peter Duck or Missee Lee. A rattling good yarn can far more readily be written, he appears to imply, from the day-to-day details of one's own suburb or village than from some half-baked otherwhere.

The Radcliffe Camera (Oxford)

I liked all of the books, but the last one, The Gates of Bannerdale, where Bill Melbury finally leaves his tiny village to go to Oxford, was definitely my favourite. Heightened, packed with incident, certainly - but basically plausible: that was the hallmark of all of Geoffrey Trease's books.

Funnily enough, my father only owned four of the five novels in the series, so the third, Black Banner Players, remained a mystery to us. There were enough references to it in the remaining two books to deduce what it was about, but I didn't read it until I myself went off to university in the UK.

The National Library of Scotland (Edinburgh)

In my first year at Edinburgh university, I'd got into the habit of ordering up piles of books from the stacks from my desk in the National Library of Scotland. One day it occurred to me that, given it was one of Britain's major copyright libraries, they might well have a copy of Black Banner Players. As it turned out, they did, and so that's where I first encountered it.

I didn't like it. The conditions were not particularly conducive to relaxed reading: and it seemed to me to contain too much of a concentration on one of Trease's obsessions: shoplifting (which recurs in his later Maythorn series). That would be a good thirty years ago now, and I've recently re-read the book with very different feelings. It now seems to me every bit as good as the others, and in fact a very satisfactory addition to the series.

It's still by far the most difficult of the books to find second-hand, so I was forced to buy a paperback reprint by a firm called "Girls Gone By," specialising in forgotten children's books. Even that wasn't cheap. So if you ever see a hardback copy in good condition lying around, I'd suggest getting down on it pretty quickly.

And, if you haven't read any of them, you might well feel like giving Geoffrey Trease's books a go. The innovations he pioneered are now pretty universally accepted, so they're unlikely to strike you as particularly modern or revisionist - but the man hailed by George Orwell as "that creature we have long been needing, a ‘light’ Left-wing writer, rebellious but human" is unlikely ever to fade into complete obscurity.

Here's a list of the unfortunately very limited number of books by him I own. They do include some interesting curiosities, though. As well as his two 'Maythorn' books, I also have the pair he wrote about Garibaldi, as well as his novels about Greek drama - The Hills of Varna and The Crown of Violet:

Geoffrey Trease

Robert Geoffrey Trease

(1909-1998)

Cue for Treason. 1940. Illustrated by Zena Flax. Puffin Books. 1965. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971.

The Hills of Varna. Illustrated by Treyer Evans. 1948. London: Macmillan & Co Ltd., 1956.

The Crown of Violet. 1952. Illustrated by C. Walter Hodges. Puffin Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1968.

The Maythorn Story. Illustrated by Robert Hodgson. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1960.

Change at Maythorn. Illustrated by Robert Hodgson. 1962. London: The Children’s Book Club, 1963.

Follow My Black Plume. 1963. Illustrated by Brian Wildsmith. Puffin Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972.

A Thousand for Sicily. Illustrated by Brian Wildsmith. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1964.

The Red Towers of Granada. 1966. Illustrated by Charles Keeping. Puffin Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972.

Geoffrey Trease: Cue for Treason (1940)

Published on March 29, 2019 20:04

March 1, 2019

The Tribulations of T. E. Lawrence

Augustus John: Colonel T.E. Lawrence (1919)

As a kind of add-on to my series of posts about the Garnett family (and, for that matter, as an adjunct to my fascination with polymath poet Robert Graves), I thought I'd write a piece about their mutual friend T. E. Lawrence: a devotee of small-press publishing, and, consequently, something of an idol to book-collectors everywhere.

The portrait above supplies the heroic image of Lawrence we're most familiar with: at the height of his fame, the world at his feet, and his image as the quintessential "desert-mad Englishman" on display front-and-centre in the Paris Peace Conference at the end of World War I.

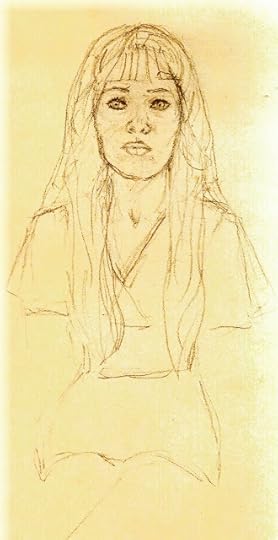

Lawrence himself appears to have preferred the rather more equivocal and self-doubting version of himself presented in this preliminary sketch by Augustus John:

Augustus John: T.E. Lawrence (1919)

In a strange sense, though, his role had already been prepared for him even before the Allied propaganda machine began to focus on him in 1917 - when there was precious little good news anywhere else in the world.

His exploits as a kind of Arabic version of Zorro or the Swamp Fox were vamped up mercilessly by pioneering American film-maker Lowell Thomas after their meeting in Jerusalem in 1918, culminating in his travelling show "With Allenby in Palestine and Lawrence in Arabia" (1919).

Lowell Thomas & T. E. Lawrence (1924)

But even before that, in 1916, Jingoistic author John Buchan had created a kind of Lawrence avatar in the form of "Sandy Arbuthnot," one of the protagonists of his novel Greenmantle, an exciting tale of a religious revolt against the Turks and their German allies, led by the eponymous prophet "Greenmantle," eventually impersonated by Sandy himself.

John Buchan: Greenmantle (1916)

Greatly though Buchan subsequently came to admire Lawrence - "I am not much of a hero-worshipper, but I could have followed Lawrence over the edge of the world" - it's not really possible that he could have known enough about him at this stage to base his hero on him.

Instead, it's thought that the model for Sandy Arbuthnot was his friend Aubrey Herbert, the half-brother of Lord Carnarvon (of Tutankhamun fame), and a colleague of Lawrence's in the intelligence war in the Middle East.

Effigy of Colonel The Honourable Aubrey Nigel Henry Molyneux Herbert DL (1880–1923)

•

So much for the foundations of the myth. Wherever it came from, and whatever its ingredients, it grew far beyond any expectations of wartime propaganda. Nor was this hindered by the immensely complex way in which Lawrence backed his war reminiscences into print. The story is best told by Jeremy Wilson, his authorised biographer:

In 1922 T. E. Lawrence finished work on the third draft of Seven Pillars of Wisdom. The first, written during 1919, had been incomplete when it was stolen from him at Reading station. The second had been a hurried re-write, dashed-off from memory. Using this as a basis, Lawrence worked for many months on a third version, which he corrected and polished. There were probably intermediate drafts of most chapters, because what finally emerged was a fair-copy manuscript. This, the earliest surviving complete text, is nearly 84,000 words longer than the version he later issued to subscribers.This theft of the original, 1919 version has gone into folklore. Many have dreamed of locating that first, scrawled manuscript of what would become an immensely controversial book. What extra secrets did it contain? What indiscretions led to its being stolen - by the British secret service, perhaps? Or was it, as Lawrence himself intimated, simply mislaid?

The new, 1922 draft was printed and bound up in eight copies, which were distributed to a number of influential literary friends: E. M. Forster, Edward Garnett, Robert Graves and George Bernard Shaw among them. As Wilson rather coyly remarks: "It was this 1922 text which convinced readers that Lawrence had written a masterpiece." There was immense interest from publishers, and Edward Garnett offered to make an abridgement if its author still had misgivings about issuing the full text.

On 16 August 1922 Lawrence enlisted in the RAF under the pseudonym of "J. H. Ross." This attempted act of self-abnegation was, however, stymied by press attention, and he was forced to resign in January 1923. A couple of months later, a certain "T. E. Shaw" enlisted as a private in the Tank Corps, which was far less congenial to him. He was able to negotiate a transfer back to the RAF in 1925, however.

Through all these shenanigans, one of the few things keeping him afloat was his work on revising and tightening the text of this (so-called) 'Oxford' version of The Seven Pillars of Wisdom, which eventually resulted in the very expensive, full illustrated subscriber's edition of 100 copies in 1926.

T. E. Lawrence: The Seven Pillars of Wisdom (subscribers edition) (1926)

Lawrence was careful to receive no profit from this publication. The production costs (especially the reproduction of the illustrations) were so high that he actually ended up in deficit. He did, however, allow Jonathan Cape to issue a shorter version, Revolt in the Desert, abridged by Edward Garnett, in 1927.

T. E. Lawrence: Revolt in the Desert (1927)

After Lawrence's death in 1935, his brother A. W. Lawrence, who had been named as his literary executor, decided to reprint the subscriber's edition for the general public. The rest is history. The Seven Pillars of Wisdom has probably never been out of print since. The longer 1922 version was not, however, reprinted until 1997.

T. E. Lawrence: Seven Pillars of Wisdom (trade edition) (1935)

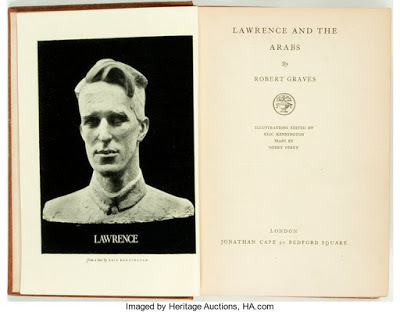

As far as the differences between the two texts go, Robert Graves, who published a popular biography of Lawrence in 1927, gave his views as follows:

There is such a thing as a book being too well written, too much a part of literature ... It should somehow, one feels, have been a little more casual, for the nervous strain of its ideal of faultlessness is almost oppressive ... On the whole I prefer the earliest surviving version, the so-called Oxford text, to the final printed text.Lawrence laughed this off as proof that Graves wanted to assert his superior knowledge by revealing in this offhand way that he'd actually been allowed to see the earlier version. It must have rankled, though (as did Leonard Woolf's comment, in a review of Revolt in the Desert, that "every sentence begins again with a full breath and ends with a really full stop"). A few years later he asked E. M. Forster to read and compare the two texts. Forster's judgement was, when it came, just as equivocal:

I had to admit that the sentences in the revision were more concise and showed a superior sense for the functions, and incidentally for the etymology, of the words employed in them. But the relation between the sentences seemed to me a little impaired: the connection, though logical, wasn't always easy.Later, after Lawrence's death, when the question of which version to reprint arose, Forster responded more straightforwardly:

the Oxford is in the judgment of several critics even superior to the version offered now, and it is good news that a reprint of it may eventually be made.That didn't happen in A. W. Lawrence's lifetime (he died in 1991), but when, a few years later, the 1922 text was finally published, the comparison could finally be made by anyone - not simply a few privileged scholars and friends.

T. E. Lawrence: The Seven Pillars of Wisdom (2014)

•

Does it matter? Not as much as you'd think, I'm sorry to say. Lawrence's legend has always shone brighter in the writings of others than in his own work. The Seven Pillars of Wisdom, I think most of us who've actually read it can attest, is overwritten and difficult to follow. Not so his letters, which are clear, informal and fascinating. But it's as a character - the star of a series of warring biographies, as well as conflicting betrayals on stage and screen - that he's come down to us most vividly.

Michael Goldberg, dir.: The Ascent of F6 (Northern Illinois University)

This began early, in masked form, in W. H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood's play The Ascent of F6 (1936). The latter's autobiography Christopher and His Kind (1976) lays out the dichotomy the two had evolved between the 'truly strong' and the 'truly weak' man:

The truly strong man, calm, balanced, aware of his strength, sits drinking quietly in the bar; it is not necessary for him to try and prove to himself that he is not afraid, by joining the Foreign Legion ... leaving his comfortable home in a snowstorm to climb the impossible glacier ... [192]"From Christopher and Wystan's point of view, the Truly Weak Man was represented by Lawrence of Arabia, and hence by their character Michael Ransom in F.6."

This was, however, during the period when the Lord Chancellor still had to licence all new plays in Britain, and amongst his prerogatives was preventing the portrayal of public figures on stage in any but flattering guises. This power weakened over the years, and even before the abolition of state censorship of theatre in 1968, a number of attempts had been made to subvert this principle.

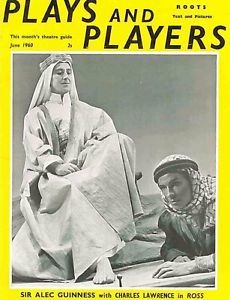

Terence Rattigan: Alec Guinness as Lawrence/Ross (1960)

Among these was Ross - a play by immensely popular dramatist Terence Rattigan (author of The Winslow Boy, The Browning Version and French without Tears).

The play concerns blackmail. It's based on a rumour Rattigan (himself a very closeted homosexual) had heard that a man called Dickinson had threatened to "out" Lawrence while he was hiding under a pseudonym in the RAF. Alec Guinness played Lawrence, and - it is alleged - made the homosexual undertones of the play more apparent in performance than in the published text. Wikipedia adds that:

Ross was originally written as a film script for the Rank Organization, with Dirk Bogarde cast as Lawrence. The project fell through due to a combination of financial difficulties and political turmoil in Iraq, where it was to be filmed. A later attempt to adapt the play, with Laurence Harvey as Lawrence, was scrapped when David Lean's Lawrence of Arabia went into production.

David Lean / Robert Bolt: Peter O'Toole as Lawrence (1962)

Which is where we re-enter history. Who has not seen, and marvelled at, Lawrence of Arabia? It must be one of the single most influential films of modern times. The sweep of it, the epic scope, the cinematography - on and on we rave.

A. W. Lawrence hated it. And it did have the effect of eclipsing the private, scholarly Lawrence he'd been quietly constructing off on his own all those years, and turning his brother into a preening egomaniac, a poseur, a victim - anything but the scholar and gentleman he was (or at least may much of the time have wanted to be).

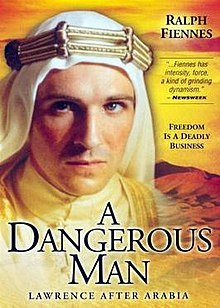

Christopher Menaul / Tim Rose Price: Ralph Fiennes as T. E. Lawrence (1992)

There've been other attempts to resurrect Lawrence since. One of the most creditable is recorded above. But it's rather like trying to rewrite Hamlet. It can be done, of course, but the mould has really been set once and for all. Robert Bolt, David Lean, Peter O'Toole and T. E. Lawrence can never now be seen entirely separately again.

But that's not to say that the battle of the books didn't continue. One thing about writers is that they never allow somebody else the last word. The saga of Lawrence's biographers is perhaps even more interesting - and certainly more complex and involved - that that of his dramatic incarnations.

•

Lowell Thomas: With Lawrence in Arabia (1924)

Robert Graves: Lawrence and the Arabs (1927)

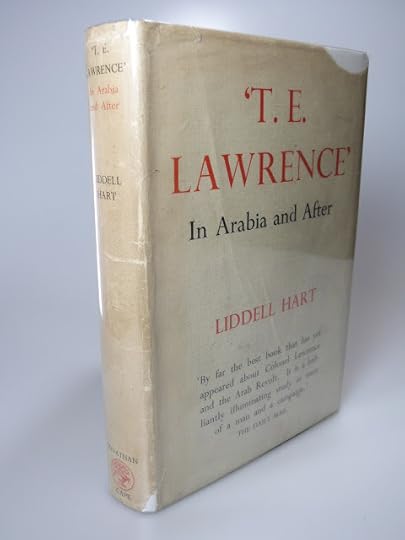

Basil Liddell Hart: 'T. E. Lawrence': In Arabia and After (1934)

It began - after the Lowell Thomas farrago - with subtly modulated hagiography, under the close supervision of (first) Lawrence himself, and then his beloved brother. First Robert Graves, then Basil Liddell Hart, and finally A. W. Lawrence himself had a go at constructing a suitable memorial frieze:

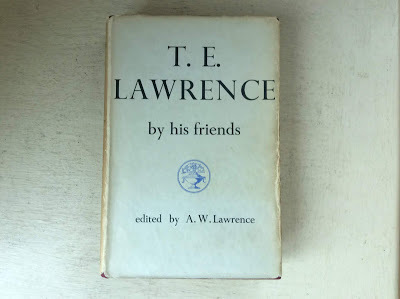

A. W. Lawrence, ed.: T. E. Lawrence by His Friends (1937)

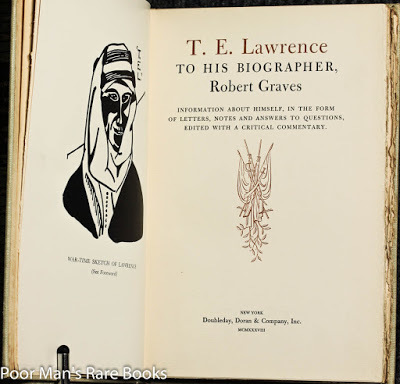

T. E. Lawrence to his Biographer: Robert Graves (1938)

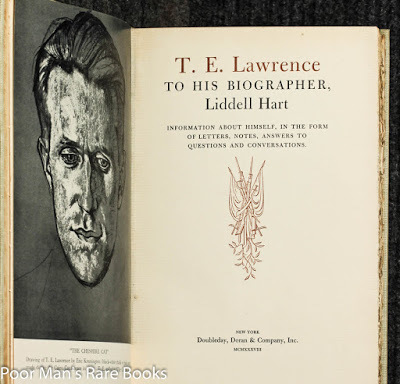

T. E. Lawrence to his Biographer: Liddell Hart (1938)

As you can see from the above, Lawrence was not exactly bashful about supplying his biographers with answers to faqs. But you can't really keep a lid on things forever, however assiduous a literary executor you are.

In 1955 war poet and novelist (and ex-husband of American poet H. D.) Richard Aldington published possibly the most concerted attack on Lawrence and the Lawrence myth ever penned.

Richard Aldington: Lawrence of Arabia: A Biographical Enquiry (1955)

I think the true nature of Aldington's work only struck me when I read a passage where he quotes someone's anecdote about how the Lawrence boys used to cycle to school in single file, one after the other, in order of age. "I don't know what this proves," quips Aldington, "except that a talent for posing manifested in him at an early age."

And so he continues. Oceans of bile are poured over poor Lawrence's head, and the gripes and dissatisfactions of a lifetime (Aldington's) are all attributed to him. This is not to say that the Lawrence legend didn't deserve some debunking, but one can't quite feel that Aldington had the temperament to do a really effective job.

A rather better attempt was made John Mack in his wonderfully titled (and Pulitzer prize-winning) psychological biography A Prince of Our Disorder:

John E. Mack: A Prince of Our Disorder: The Life of T. E. Lawrence (1976)

Just what was wrong with Lawrence? Why did he behave so strangely? Why did he pay a man to come and beat him in his later years in London? Was he a sado-masochist? Was he gay? Was he impotent? Few stones are left unturned in the course of the questioning.

After which, I suppose, a few people thought the poor fellow might be left to lie in his grave undisturbed for a while. It was not to be. The final tombstone of an 'authorised biography' still awaited him:

Jeremy Wilson: Lawrence of Arabia: The Authorised Biography of T. E. Lawrence (1989)

Opinions on Jeremy Wilson's magnum opus differ greatly. It was selected by The New York Times as one of the six best nonfiction books of 1990, while the Toronto Star described it as "an unremarkable book." It all depends on what you're looking for, I suppose.

For myself, I found that it answered almost all of the nagging questions I had about Lawrence: and that its depth and weight of research did have the effect of wiping other, competing attempts at biography (including, I'm afraid, Mack's) out of the field.

Was Lawrence a pathological liar, who shifted and invented things in his own account of his wartime exploits? The apparent inconsistencies in his text had led earlier commentators to assume so, but Wilson makes a surprisingly strong case for the proposition that Lawrence was actually remarkably accurate and truthful: not only about impressions, but also about the recorded facts of events.

Again and again "errors" in Lawrence's book turn out to be backed up by contemporary documents. Before Wilson, it seems that nobody really bothered to check. The website for Wilson's private press Castle Hill Books reveals just how much he's gone on to do for Lawrence's posthumous reputation. This includes a massive, multi-volumed edition of Lawrence's surviving correspondence, and - perhaps most importantly of all - the republication of the 1922 text of The Seven Pillars of Wisdom.

I can't help feeling that many of the sneers (or yawns) that have been directed at his great biography of his hero come either from people who haven't read it, or - even more likely - haven't read any of its forest of predecessors. If you really want to know the facts about T. E. Lawrence, admittedly from a very favourable viewpoint, there's really no alternative to reading Wilson: the full 1989 text, mind you, not the 1992 abridgement.

Here's a list of the Lawrence-iana in my own collection. As you'll see, it's quite extensive, but by no means complete. For a man who published so little in his own lifetime, Lawrence casts a surprisingly long shadow for subsequent bibliographers:

•

T. E. Lawrence at Miranshah (1928)

Thomas Edward Lawrence

(1888-1935)

T. E. Lawrence: Works (1910-35)

Works:

Lawrence, T. E. Crusader Castles. 1910. Ed. A. W. Lawrence. 1936. Introduction by Mark Bostridge. London: The Folio Society, 2010.

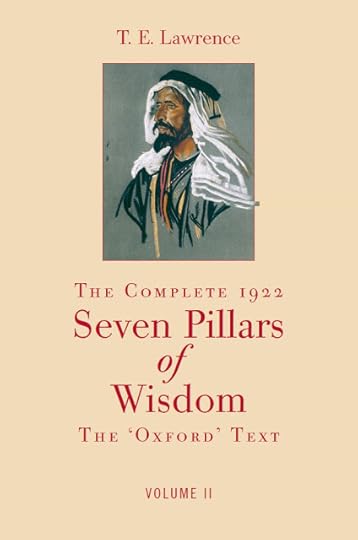

Lawrence, T. E. The Complete 1922 Seven Pillars of Wisdom: The 'Oxford' Text. 1922. Ed. Jeremy Michael Wilson. 1997. 2nd ed. 2003-4. 3rd. ed. 2 vols. Salisbury, England: Castle Hill Press, 2014.

Lawrence, T. E. Seven Pillars of Wisdom: A Triumph. 1926. London: Jonathan Cape Ltd., 1946.

Lawrence, T. E. Revolt in the Desert. New York: Garden City Publishing Company Inc., 1927.

Lawrence, T. E. The Mint: The Complete Unexpurgated Text. Ed. A. W. Lawrence. 1936. Preface by J. M. Wilson. Penguin Modern Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978.

Lawrence, T. E. Oriental Assembly. With Photographs by the Author. Ed. A. W. Lawrence. 1939. London: Williams and Norgate Ltd., 1939.

Garnett, David, ed. The Essential T. E. Lawrence. 1951. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1956.

Garnett, David, ed. The Essential T. E. Lawrence: A Selection of His Finest Writings. 1951. Introduction by Malcolm Brown. Oxford Paperbacks. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Edited:

Lawrence, T. E., ed. Minorities. Ed. J. M. Wilson. Preface by C. Day Lewis. London: Jonathan Cape, 1971.

T. E. Shaw: The Odyssey (1932)

Translations:

Shaw, T. E. (Colonel T. E. Lawrence), trans. The Odyssey of Homer: Translated into English Prose. 1932. London: Oxford University Press, 1960.

T. E. Lawrence: Letters (c.1900-35)

Letters:

Garnett, David, ed. The Letters of T. E. Lawrence. London: Jonathan Cape Ltd., 1938.

Lawrence, M. R., ed. The Home Letters of T. E. Lawrence and His Brothers. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1954.

Lawrence, A. W., ed. Letters to T. E. Lawrence. London: Jonathan Cape Ltd., 1962.

T. E. Lawrence: Biographies (1924-89)

Secondary:

Thomas, Lowell. With Lawrence in Arabia. London: Hutchinson & Co. (Publishers), Ltd., 1924.

Graves, Robert. Lawrence and the Arabs. Illustrations ed. Eric Kennington. Maps by Herry Perry. London: Jonathan Cape Ltd., 1927.

Liddell Hart, B. H. ‘T. E. Lawrence’: In Arabia and After. London: Jonathan Cape Ltd., 1934.

Lawrence, A. W., ed. T. E. Lawrence by His Friends. 1937. London: Jonathan Cape Ltd., 1938.

Aldington, Richard. Lawrence of Arabia: A Biographical Enquiry. London: Collins, 1955.

Mack, John E. A Prince of Our Disorder: The Life of T. E. Lawrence. 1976. New Preface by the Author. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1998.

Wilson, Jeremy. Lawrence of Arabia: The Authorised Biography of T. E. Lawrence. 1989. Minerva. London: Mandarin Paperbacks, 1990.

Howard Brenton: Lawrence after Arabia (2016)

Dramatic versions:

Plays of the Sixties. Volume One: Ross, by Terence Rattigan; The Royal Hunt of the Sun, by Peter Shaffer; Billy Liar, by Keith Waterhouse & Willis Hall; Play with a Tiger, by Doris Lessing. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1966.

Lawrence Of Arabia, dir. David Lean, writ. Robert Bolt – with Peter O’Toole, Alec Guinness, Anthony Quayle – (USA, 1962)

Brownlow, Kevin. David Lean: A Biography. Research Associate: Cy Young. 1996. A Wyatt Book. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1997.

T. E. Lawrence with Emir Abdullah (1921)

Published on March 01, 2019 10:56

February 25, 2019

The Garnett Family (4): Richard the Third

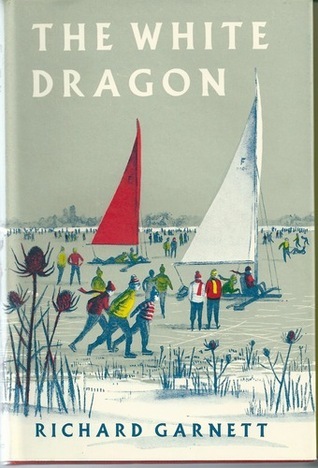

Richard Garnett: The White Dragon (1963)

It's strange how important reading the right children's book at just the right time can be.

I'm not sure just what impression Richard Garnett's White Dragon would have on me now if I were encountering it for the first time, but, as it turned out, it had the effect of introducing me to a whole set of fascinating topics which have interested me ever since:

St. George and the Dragon (St Albans: 2015)

Mummer's Plays

For more on this, I strongly recommend the following:

E. K. Chambers. The English Folk-Play. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1933.

E. K. Chambers: The English Folk-Play (1933)

In the book, the children find the remains of a pantomime dragon, "Old Snap," and are inspired to resurrect an almost forgotten seasonal play in which St. George battles this personification of winter in order to bring life back to the land again.

•

Daniel Defoe: A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain (Folio Society, 2006)

Daniel Defoe's Tour of the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724-26)

Garnett's protagonist, Mark Rutter, also centre stage in his earlier book The Silver Kingdom, reads a passage from Defoe's fascinating compendium of local gossip and anecdotes - combined with direct observation - about a mysterious 'white worm' which can only be seen at certain times of day on a nearby eminence called the 'Wormell' (or Worm-Hill).

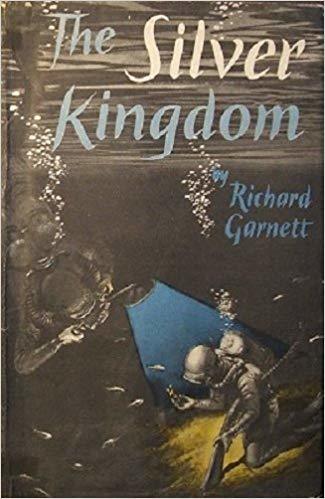

Richard Garnett: The Silver Kingdom (1957)

Mark, who is (according to his archaeologist friend from the previous book) a 'born finder', discovers the solution to this mystery by sheer happenstance, and unearths another dragon to set alongside Old Snap.

•

Uffingdon White Horse (c.1000 BC)

Hillside chalk figures

Sure enough, the second 'white dragon' in the book turns out to be a chalk figure cut into the hillside. Unlike the more familiar examples, where the turf has to be recut periodically to keep them visible, the 'white worme' of the Wormell has been made out of chalk packed into man-made ditches on this artificial eminence. As a result, it proves possible to re-establish its long-overgrown contours by the simple expedient of drilling small holes in the hillside.

Graham Oakley: Cover illustration (1963)

The above illustration shows the contours of the chalk figure as it is eventually revealed. Mark spots it because the snow melts more slowly on the chalk than the earth of the hill, so he is able to photograph its momentarily revealed shape one evening during the thaw: a 'born finder', indeed!

•

Adriaen Pietersz van de Venne: Der Winter (1614)

Ice yachting

Constructing an ice yacht for his cousin Tom, a keen skater injured in a road accident years before, and now forced to go everywhere on crutches, forms most of the actual narrative of the book.

This was the era of the can-do hero, when a set of enterprising boys and girls could easily solve a cipher, reconstruct an old building, start an archaeological dig, or - as in this case - master the mechanics of ice-yachting.

It's strangely inspiring to read about, however little it may resemble the pathetic constructions of cardboard and plastic which were all I and my contemporaries could achieve.

Richard Garnett: The White Dragon (1963)

The original cover of the hardback edition, above, shows the success that attends their efforts. 'The White Dragon' and 'The Red Knight' are the names of the two yachts they build out of a few old planks and some leftover ice-skates provided by the local junkshop owner.

•

Year of the "Dragon" (2012)

Mahjong

This is more of a peripheral reference in the book, but a 'white dragon' in mahjong is a totally blank tile. It's named from the fact that such a sheet of white can represent a white dragon hiding on a field of snow - or nothing at all, depending on how you interpret it.

The beginner's guide to the greatest pastimes: Mahjong

The book concludes with the gift to Mark from his friends of a blank mahjong tile, the fourth (and last) dragon in the story. When asked what the difference is between a white dragon and a blank tile, he replies: "All the difference in the world." Those, rather appropriately, are the last words of the text.

•

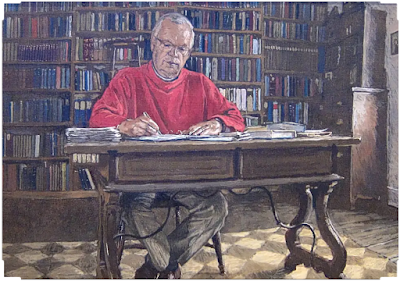

Julian Bell: Richard Garnett (1992)

As you'll have deduced from the title of my blogpost, the author of The White Dragon, Richard Garnett (1923-2013), was the third writer of that name, in direct line of descent from Richard Garnett the Philologist (1789-1850), and Richard Garnett the writer and editor (1835-1906). He was the grandson of Edward and Constance Garnett, and the son of David and Ray Garnett.

Despite - or perhaps because of - the weight of this family legacy, he was a pretty competent and multi-faceted character in his own right.

As well as an author of children's books (his only other published work in this vein, the historical novel Jack of Dover, is pictured below), he was also an editor and publisher.

Richard Garnett: Jack of Dover (1966)

This is his history of the firm that he mainly worked for, Rupert Hart-Davis, co-founded by his father, David Garnett:

Richard Garnett: Rupert Hart-Davis Limited: A Brief History with a Checklist of Publications (2005)

Nicolas Barker has this to say of his skills as a publisher in his 2013 Independent obituary:

Garnett was ... [Rupert Hart-Davis]'s production manager, and soon an expert editor as well. Heinrich Harrer's Seven Years in Tibet, another bestseller, and the three-volume autobiography of Lady Diana Cooper (Hart-Davis's aunt), exercised both skills. Laurence Whistler's books spurred him to become a glass-engraver. His nautical experience came to the fore with the Mariner's Library of sea classics ... But the heart of the firm lay not in these but in scholarly but readable books such as Leon Edel's five-volume life of Henry James, Allan Wade's Letters of W. B. Yeats and Peter Fleming's imperial sagas. All of these achieved their reputation thanks to the joint expertise of Garnett and Hart-Davis. Not for nothing did one of their admiring beneficiaries call the firm "the university of Soho Square".Barker sees his two greatest achievements as: his 1991 biography of his grandmother, Constance Garnett:

But commercial success did not follow. Three times the firm had to be bailed out. Control passed first to Heinemann, then Harcourt Brace and finally to Granada. Hart-Davis himself left in 1963; three years later the firm was merged with MacGibbon & Kee and finally Garnett was sacked. As he left, a water-pipe burst in the attic, leaving him to say "Après moi le déluge". ... Fortunately, Macmillan was in need of just his talents, to supervise copy-editing and proof-correction. He soon became indispensable ... Gerald Durrell's books owed much to his editing, which verged on authorial, as did the natural history books of Bernard Heuvelmans.

Richard Garnett: Constance Garnett: A Heroic Life (1991)

his design work for The Collected Works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, edited by Kathleen Coburn et al., 16 parts in 34 volumes (Princeton University Press, 1969-2002):

Samuel Taylor Coleridge: Biographia Literaria, ed. James Engell and W. Jackson Bate (1983)

That seems as good a place as any to conclude my survey of this unusually talented family of writers and artists.

David "Bunny' Garnett had six children in all. Two sons - including Richard himself - with his first wife Rachel "Ray" Marshall (1891–1940); and four daughters with Angelica (1918–2012). The eldest of these, Amaryllis Virginia Garnett (1943–1973) was an actress who had a small part in Harold Pinter's film adaptation of The Go-Between (1970). She drowned in the Thames, aged 29 - whether by accident or suicide is unclear.

Richard Garnett himself died leaving two sons, but whether or not either of them (or their own children, for that matter) have literary ambitions remains beyond the grasp of that would-be fount of all knowledge, wikipedia.

Joseph Losey, dir.: The Go-Between (1971)

"The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there."

Published on February 25, 2019 13:20

February 14, 2019

The Garnett Family (3): "Bunny"

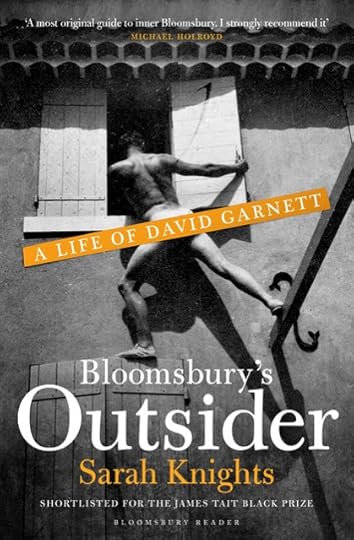

Sarah Knights: Bloomsbury's Outsider: A Life of David Garnett (2015)

Lytton Strachey, perhaps the most thoroughly naturalised of Bloomsbury insiders, once decided that it would be interesting to try to record in detail the events of a single day:

... to realize absolutely the events of a single and not extraordinary day - surely that might be no less marvellous than a novel or even a poem, and still more illuminating, perhaps! If one could do it! But one can't, of course. one has neither the power nor the mere physical possibility for enchaining that almost infinite succession; one's memory is baffled; and then - the things one remembers most one cannot, one dares not ...

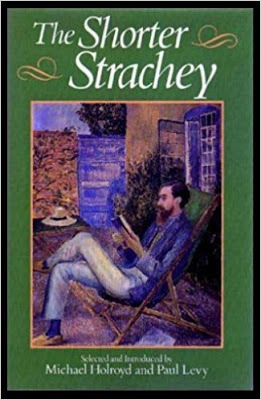

Michael Holroyd & Paul Levy, ed.: The Shorter Strachey (1980)

He decided to have a go at it, anyway. The day he chose was Monday June 26th, 1916. The results were not published till long after his death, in The Shorter Strachey (1980), but they do constitute an irreplaceable record of Bloomsbury in wartime. His biographer Michael Holroyd gives the background of the piece as follows:

Rejected as a conscientious objector, Strachey was also rejected as unfit for any kind of military service. On 26 June 1916 he was staying at Wissett Lodge, a remote Suffolk farmhouse where Duncan Grant and David Garnett had set themselves up as official fruit farmers under the National Service Act. His description of this Bloomsbury colony gives an authentic picture of a matriarchy presided over by Vanessa Bell. [21]

Christopher Hampton, writ. & dir.: Carrington (1995)

This is all material familiar from Christopher Hampton's brilliant film Carrington. What perhaps isn't quite so familiar is the following:

I went out of the room before anyone else, and walked through the drawing-room out onto the lawn. It was still quite light, though it must have been past nine o'clock. I paced once or twice up and down the lawn, when Bunny appeared and immediately joined me. ... I felt nervous, almost neurasthenic - what used to be called 'unstrung'. He was so calm and gentle, and his body was so large, with his shirt (with nothing under it) open all the way down - that I longed to throw myself onto him as if he were a feather-bed, to tell him everything - everything, and to sob myself asleep. And yet, at the same time, the more I longed to expand, the more I hated the thought of it. It would be disgusting and ridiculous. It was out of the question ... We went and sat on a dirty seat at the end of [the kitchen garden], and I thought that if it had been a clean stone seat, and if he had been dressed in white knee-breeches and a blue coat with brass buttons, and if I had been a young lady in a high waist - or should it have been the other way round? - the scene would have done well for an academy picture by Marcus Stone.Of this delightful scene (for Lytton, at least) David Garnett later caustically observed:

Marcus Stone: Two's Company, Three's None (1892)

... We came nearer to one another, and, with a divine vigour, embraced. I was amused to notice, just before it happened, that he looked very nervously in the direction of the house. We kissed a great deal, and I was happy. Physically, as well as mentally, he had assuaged me. That was what was so wonderful about him - he gave neither too little nor too much. I felt neither the disillusionment of having gone too far, nor any of the impatience of desire. I knew that we loved each other, and I was unaware that my cock had moved. [34-37]

What I remember must have been the next day - the day he apparently left. We went for a walk along the edge of a cornfield and he told me that he was in love, or more than a little in love with Carrington and made me promise not to tell Vanessa or Duncan or anyone. ... I kept my promise ... I suppose it was the reassurance I had given him which led him to confide in me and he was also perhaps more ready to confide a heterosexual attachment to me than a daydream about the postman which would have strained my powers of sympathy!Bloomsbury!

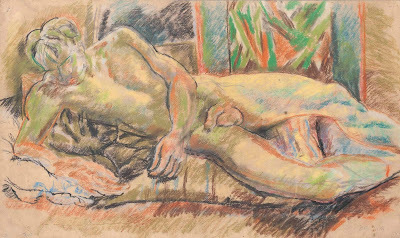

I guess, at the very least, this extract serves to give you some idea of the polymorphous complexity of its day-to-day life. The aptly nicknamed "Bunny" (David Garnett) would go on to marry Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell's daughter Angelica, a quarter of a century his junior, who was not even born at the time. Duncan Grant was, rather awkwardly, an ex-lover of his.

Duncan Grant: Portrait of David Garnett (1915)

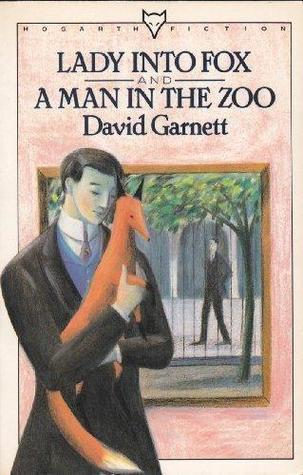

These complexities of his emotional life have grown to overshadow unfairly the range of David Garnett's creative work, though I suppose it could be said that attempts to convey the complexities of love lie at the heart of most of his writing: certainly his first great success, the fantasy Lady into Fox (1922), but also such later novels as Aspects of Love (1955), adapted as a musical by Andrew Lloyd Webber in 1989.

Andrew Lloyd Webber: Aspects of Love (1990)

I suppose what appeals to me most about Garnett is this many-sidedness of his. He could be somewhat censorious of the sexual irregularities of others in later years - witness some very judgemental remarks about the sado-masochistic leanings of his friend T. H. White (included in the published correspondence between the two), as well as the implied sneer at Lytton Strachey above. But you don't have to approve of every aspect of someone's behaviour to find them a fascinating study. In fact, I'd feel inclined to assert the opposite.

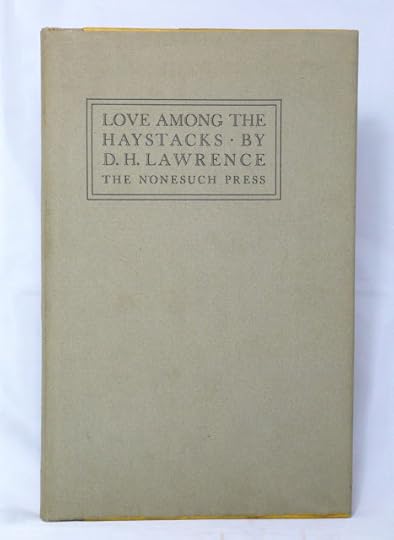

As well as a well-thought-of novelist, he was also a pioneering publisher and editor: co-founder of the Nonesuch Press with Frances Meynell in 1922, and editor of some of its most intriguing volumes of contemporary writing - such as D. H. Lawrence's Love Among the Haystacks & Other Pieces: With a Reminiscence by David Garnett (1930):

D. H. Lawrence: Love Among the Haystacks (1930)

Among his other achievements as an editor, the following all deserve a mention:

David Garnett, ed. The Letters of T. E. Lawrence of Arabia (1938)

The Letters of T. E. Lawrence. London: Jonathan Cape Ltd., 1938.

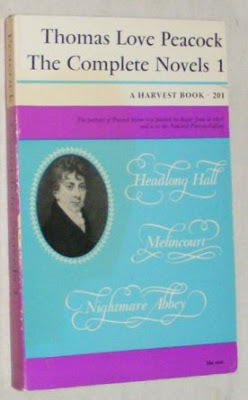

David Garnett, ed.: The Novels of Thomas Love Peacock (1948)

The Novels of Thomas Love Peacock. London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1948.

David Garnett, ed.: The Essential T. E. Lawrence (1951)

The Essential T. E. Lawrence: A Selection of His Finest Writings. 1951. Introduction by Malcolm Brown. Oxford Paperbacks. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

David Garnett, ed.: The White / Garnett Letters (1968)

The White / Garnett Letters. London: Jonathan Cape Ltd., 1968.

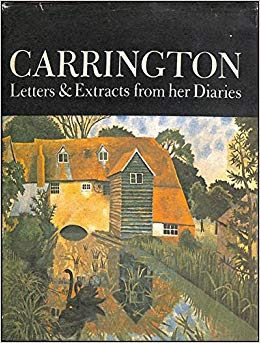

David Garnett, ed.: Carrington: Letters and Extracts from Her Diaries (1970)

Garnett, David, ed. Carrington: Letters and Extracts from Her Diaries. Biographical Note by Noel Carrington. 1970. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979.

Thomas Love Peacock: The Complete Novels I (1948 / 1963)

These are all substantial books, in use to this day, and witness to his wide range of friends and acquaintances - as well as to a set of scholarly skills presumably inherited from his grandfather (who preceded him as an editor of Peacock).

Here's a list of his works (the ones which I myself own - a mere 18 out of 44 - are marked in bold, so you can see that I have a long way to go before I can boast a really comprehensive collection):

David Garnett: Lady into Fox & A Man in the Zoo (1922 / 1944)

David ('Bunny') Garnett

(1892-1981)

Novels:

[as 'Leda Burke'] Dope Darling (1919)

Lady into Fox (1922)

A Man in the Zoo (1924)

The Sailor's Return (1925)

Go She Must! (1927)

No Love (1929)

The Grasshoppers Come (1931)

A Terrible Day (1932)

Pocahontas, or, the Nonpareil of Virginia (1933)

Beany-Eye (1935)

Aspects of Love (1955)

A Shot in the Dark (1958)

A Net for Venus (1959)

Two by Two: A Story of Survival (1963)

Ulterior Motives (1966)

A Clean Slate (1971)

The Sons of the Falcon (1972)

Plough Over the Bones (1973)

The Master Cat (1974)

Up She Rises (1977)

Short Stories:

The Old Dove Cote (1928)

Purl and Plain (1973)

Autobiography & Memoirs:

Never Be a Bookseller (1929)

The Golden Echo (1953)

The Flowers of the Forest (1955)

The Familiar Faces (1962)

Great Friends: Portraits of Seventeen Writers (1979)

Miscellaneous:

A Rabbit in the Air: Notes from a Diary Kept While Learning to Handle an Aeroplane (1932)

The Battle of Britain (1941)

War in the Air (1941)

The Campaign in Greece and Crete (1942)

The First 'Hippy' Revolution (1970)

The Secret History of PWE: The Political Warfare Executive, 1939–1945 (2002)

Edited:

Letters from John Galsworthy, 1900–1932 (1934)

The Letters of T. E. Lawrence (1938)

The Novels of Thomas Love Peacock (1948)

The Essential T. E. Lawrence (1951)

Selected Letters of T. E. Lawrence (1952)

The White / Garnett Letters (1968)

Carrington: Letters & Extracts From Her Diaries (1970)

Translated:

André Maurois: A Voyage to the Island of the Articoles (1928)

Victoria Ocampo: 338171 T. E. (Lawrence of Arabia) (1963)

Secondary:

David Garnett, C.B.E.: A Writer's Library (1983)

Knights, Sarah. Bloomsbury's Outsider: A Life of David Garnett. London: Bloomsbury Reader, 2015.

Angelica & David Garnett (1960s)

I'm conscious, in this Garnett post in particular, of having rather skated over the complex history of the family and their interrelationships. Librarian and bibliographer Donald Kerr has reminded me of the existence of Edward Garnett's bibliophile brother Robert Singleton Garnett (1866-1932), author of - among many other titles - Some Book-Hunting Adventures: A Diversion (1931) and Odd Memories: More Book-Hunting Adventures (1932), whose collection of rare Dumas manuscripts and early editions is now housed in Auckland Public Library, but I have to admit that that's the extent of my knowledge of him.

"How much sex did one writer need?" is the title of one fellow-blogger's review of Sarah Knights' Bloomsbury's Outsider: A Life of David Garnett. Certainly, far more detail on David Garnett's love-life (in particular) than anyone could ever possibly require is included in Knights' very readable book. This is how she sums up his colourful life:

Bunny was not perfect. He espoused honesty but lacked self-awareness. His need for diversion was often destructive. He was cruel to his wife Ray. Perhaps he was selfish in loving Angelica and marrying her. But as an imperfect example of humankind he created courageous stories, wrote beautiful prose, supported his friends, helped other writers, remained true to his convictions and loved his family.The blogger quoted above ripostes as follows:

I have to disagree. I don’t mind that he was bi-sexual or polyamorous, but I do care that he thought about nobody’s emotional needs except his own. Not his wives, not his children’s and certainly not his lovers. Being a great writer did not make up for his other failings.So there the matter stands. I like his books, and I propose to keep on collecting them. That's about the size of it - for me, at least. I hope to say some more about Bunny Garnett in a future post on one of his closest friends, that even more fascinating and mercurial character T. E. Lawrence, but for now, enough said.

David Garnett, trans. Victoria Ocampo: 338171 T. E. (Lawrence of Arabia) (1963)

Published on February 14, 2019 12:48

February 9, 2019

Russian Foreign Languages Publishing House

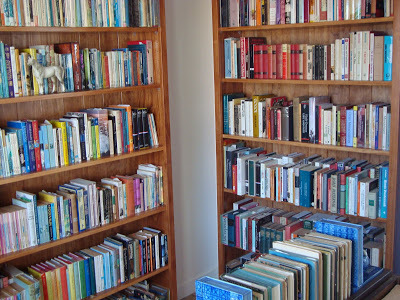

Jack & his new bookcases (Bronwyn Lloyd: 30-1-19)

Recently we decided to get some new bookcases. Above you can see the before: how they looked on delivery day. Below you can see after: how they look now I've finished arranging them:

Children's & Russian books (10-2-19)

It's clear that you'll need a bit of context before you can understand how (and why) I got from point A to point B, however. First of all, the room itself:

Anne's Room I (29-1-19)

This was once my sister Anne's bedroom. After that, it was used as an office. But it's always been a slightly awkward space: too cramped for a guest room, and too hot and stuffy to work in comfortably in the afternoons. Accordingly, we took out all the furniture:

Anne's Room II (29-1-19)

The first set of books I transplanted there were my American history books. As you'll know if you read this blog at all, I have a fascination with all aspects of the American civil war, but actually I'm partial to most of the great American narrative historians: Washington Irving, William H. Prescott, Francis Parkman, and their twentieth century counterparts: Robert Caro, Shelby Foote, David McCullough, Barbara Tuchman, and Edmund Wilson:

American History I (10-2-19)

American History II (10-2-19)

Bronwyn gave me two beautiful bookends for Christmas, a Chinese boy and girl each reading a book. The question was what to put between them?

Chinese Bookends (10-2-19)

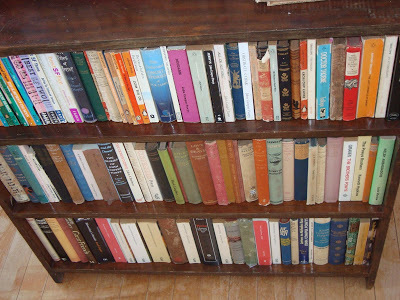

My sister had a particular fondness for books published by the Russian Foreign Languages Publishing House, with their distinctive cover designs and charmingly eccentric typefaces:

Foreign Languages Publishing House II (10-2-19)

I therefore decided to put all the volumes I had in this series (including some that used to belong to her), and put them on top of a central pair of bookcases, counterpointing the three placed against the wall:

Film & TV etc. (10-2-19)

The Powys Brothers et al. (10-2-19)

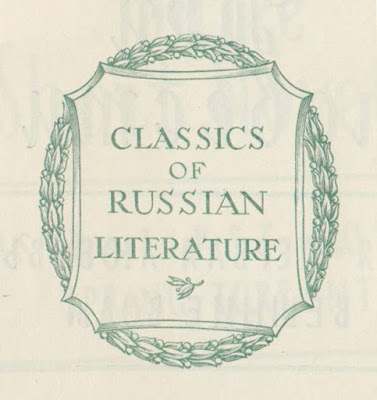

The Moscow-based Foreign Languages Publishing House, founded in 1946, included a series of Classics of Russian Literature, alongside Soviet Literature, Marxist-Leninist Classics, and various others (including the endearingly titled "Soviet Children's Library for Tiny Tots").

The translations were often clumsy and stilted by comparison with the practised smoothness of (say) Constance Garnett's versions, but that just seemed to add to their charms. They seemed so intensely Russian, somehow. Here's a list of the ones I've managed to assemble so far:

•

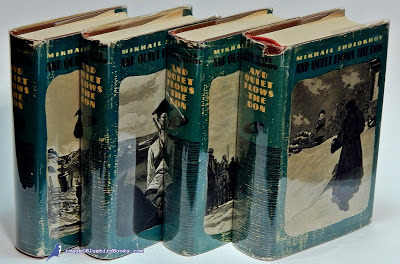

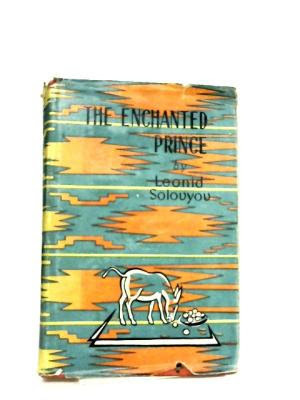

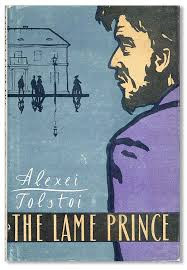

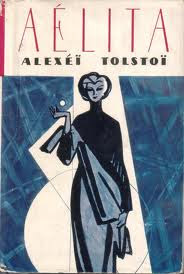

Foreign Languages Publishing House: Classics of Russian Literature (1946-64)

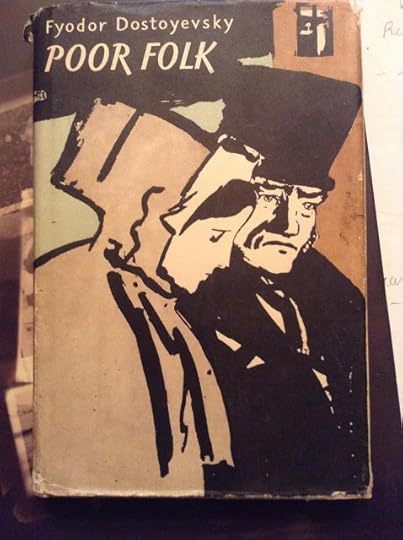

Fyodor Dostoyevsky: Poor Folk (1950s)

Dostoyevsky, Fyodor. Poor Folk. 1846. Trans. Lev Navrozov. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

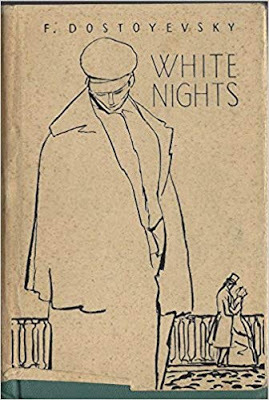

Fyodor Dostoyevsky: White Nights (1950s)

Dostoyevsky, F. White Nights / A Faint Heart / A Christmas Party and a Wedding / The Little Hero. 1848, 1848, 1848 & 1857. Trans. O. N. Shartse. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

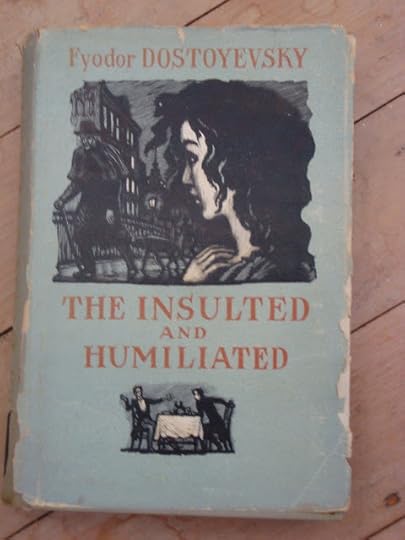

Fyodor Dostoyevsky: The Insulted and Humiliated (1957)

Dostoyevsky, Fyodor. The Insulted and Humiliated. 1861. Ed. Olga Shartse. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d. [1957].

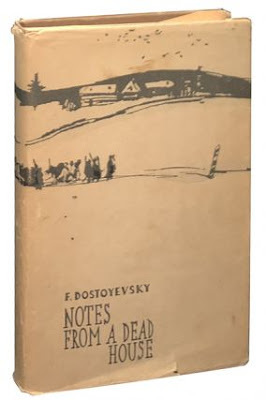

Fyodor Dostoyevsky: Notes from a Dead House (1950s)

Dostoyevsky, F. Notes from a Dead House. 1862. Trans. L. Navrozov & Y. Guralsky. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky: My Uncle’s Dream (1950s)

Dostoyevsky, Fyodor. My Uncle’s Dream / Most Unfortunate / The Gambler. 1859, 1862 & 1867. Trans. Ivy Litvinova. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

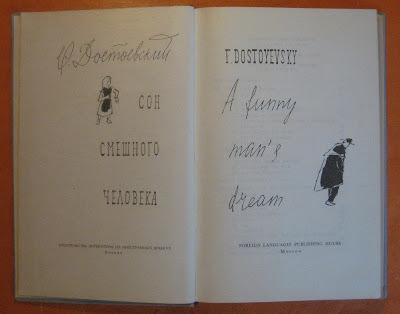

Fyodor Dostoyevsky: A Funny Man’s Dream (1950s)

Dostoyevsky, F. A Funny Man’s Dream: Our Man Marei / The Meek One: A Fantasy / A Funny Man’s Dream: A Fantasy / Stepanchikovo and Its Inhabitants. 1876, 1876, 1877 & 1859. Trans. Olga Shartse. Ed. Julius Katzer. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

Nikolai Gogol: Evenings Near the Village of Dikanka (1950s)

Gogol, Nikolai. Evenings Near the Village of Dikanka: Stories Published by Bee-Keeper Rudi Panko. 1831-1832. Ed. Ovid Gorchakov. Illustrated by A. Kanevsky. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

Nikolai Gogol: Mirgorod (1950s)

Gogol, Nikolai. Mirgorod: Being a Continuation of Evenings in a Village Near Dikanka. 1835. Illustrated by A. Kanevsky. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

Alexaner Kuprin: The Garnet Bracelet (1950s)

Kuprin, Alexander. The Garnet Bracelet and Other Stories. Trans. Stepan Apresyan. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

Mikhail Lermontov: A Hero of Our Time (1956)

Lermontov, Mikhail.A Hero of Our Time. Trans. Martin Parker. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1956.

Alexander Pushkin: The Tales of Ivan Belkin (1954)

Pushkin, A. The Tales of Ivan Belkin. 1830. Trans. Ivy & Tatiana Litvinov. Illustrated by D. A. Shmarinov. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1954.

Alexander Pushkin: Dubrovsky (1955)

Pushkin, A. S. Dubrovsky. 1833. Trans. Ivy & Tatiana Litvinov. Illustrated by V. Kolganov. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1955.

Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin: Judas Golovlyov (1950s)

Saltykov-Shchedrin, Mikhail. Judas Golovlyov. 1880. Trans. Olga Shartse. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

Lev Tolstoy: Childhood, Boyhood, Youth (1950s)

Tolstoy, Lev. Childhood, Boyhood, Youth. 1852, 1854 & 1857. Ed. D. Bitsi. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

Lev Tolstoy: Resurrection (1950s)

Tolstoy, Lev. Resurrection: A Novel. 1899. Trans. Louise Maude. Ed. L. Kolesnikov. Illustrated by O. Pasternak. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

Lev Tolstoy: Short Stories (1950s)

Tolstoy, Lev. Short Stories. Trans. Margaret Wettlin. Illustrated by V. Basov. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

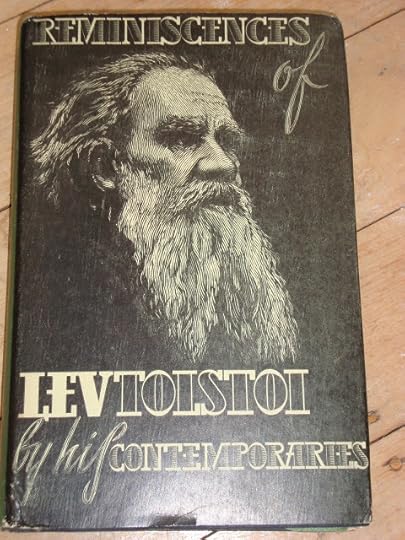

Reminiscences of Lev Tolstoi by His Contemporaries (1950s)

Wettlin, Margaret, trans. Reminiscences of Lev Tolstoi by His Contemporaries. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

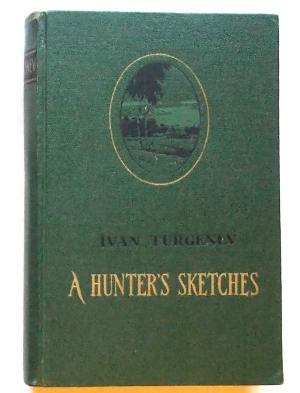

Ivan Turgenev: A Hunter’s Sketches (1950s)

Turgenev, Ivan. A Hunter’s Sketches. 1852. Ed. O. Gorchakov. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

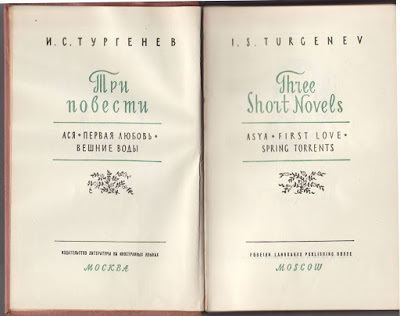

Ivan Turgenev: Three Short Novels (1946-64)

Turgenev, Ivan. Three Short Novels: Asya / First Love / Spring Torrents. 1857, 1860 & 1871. Trans. Ivy & Tatiana Litvinov. Classics of Russian Literature. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.

•

And here's an alphabetically arranged list (by author and title) of some of the other volumes I don't yet own::

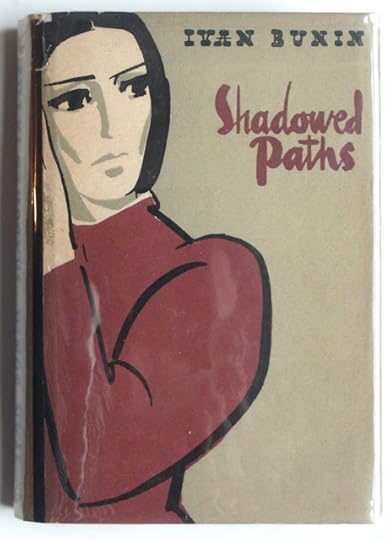

Ivan Bunin: Shadowed Paths (1950s)

Ivan BuninShadowed Paths. Translated from the Russian by Olga Shartse, n.d.

Anton Chekhov: Three Years (c.1950)

Anton ChekhovThree Years. c. 1950. 140 pp.

V. M. Garshin: The Scarlet Flower (1959)

V. M. GarshinThe Scarlet Flower. 1959. 179 pp. Frontis of author. Illustrated with black & white drawings. Navy blue cloth cover ... with red & gold lettering on its spine and a red flower on its front board.

Nikolai Gogol: Taras Bulba (c.1954)

Nikolai Vasilevich GogolTaras Bulba. Translated from the Russian by O.A. Gorchakov. Designed by D. Bisti (illustrator). c. 1958. 143 pp.

Nikolai Leskov: The Enchanted Wanderer (c.1950s)

Nikolai LeskovThe Enchanted Wanderer and Other Stories. Translated By George H. Hanna. Frontispiece photo of the author. n.d. 346 pp.

Alexander Pushkin: The Captain's Daughter (1954)

Alexander Pushkin [Aleksandr Sergeevich Pushkin]The Captain's Daughter. 1954. Beige paper over boards, gilt spine and cover titles.

Tales from M. Saltykov-Shchedrin (1950s)

M. Saltykov-SchedrinTales from M. Saltykov-Shchedrin. Collection of short stories. Translated by Dorian Rottenberg and edited by John Gibbons. n.d.

Lev Tolstoi: The Cossacks (1965)

Lev Tolstoi [Leo Tolstoy]The Cossacks: A Story of the Caucasus. Edited by R. Daglish. c. 1965.

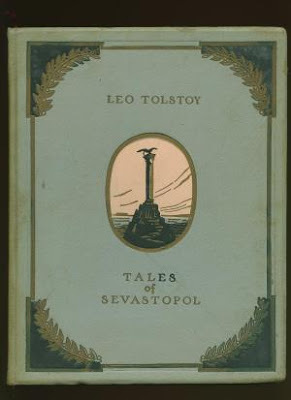

Lev Tolstoi: Tales of Sevastopol (1950)

Tales of Sevastopol. Illustrated by Pyotr Pavlinov. Classics of Russian Literature No. 17. 1950. 154 printed pages of text with one tipped-in colour plate and full-page monochrome illustrations throughout. Hard back binding in publisher's original decorated duck egg blue cloth covers. Gilt title and author lettering to the spine and to the upper panel. Quarto size: 10 1/2'' x 8 1/4''.

Ivan Turgenev: Fathers and Sons (1950s)

I. S. Turgenev [Turgenev, Ivan] [Ivan Sergeevich Turgenev]Fathers and Sons. Translated from the Russian by Bernard Isaacs. Illustrated by Konstantin Rudakov. 1951. 214 pp. 9 tipped in plates.

Ivan Turgenev: Mumu (1960)

MUMU. n.d. 78pp. "Never in the whole of literature has there been a more shattering protest against cruel tyranny."

Ivan Turgenev: On the Eve (1950s)

On the Eve. 1958. Small purple hardcover with black lettering and design on cover, 179 pp.

Books by Ivan Turgenev

Rudin. Translated by O. Gorchakov. Illustrated by V. Sveshnikov. Designed by E. Fomina. 1954. 138 pp.

•

As well as all of these Russian classics, there was the possibly even more characteristic and spirited companion library of Soviet literature:

Maxim Gorky: Childhood (1950s)