Jack Ross's Blog, page 22

November 16, 2018

Boneland: Alan Garner

Alan Garner (1934- )

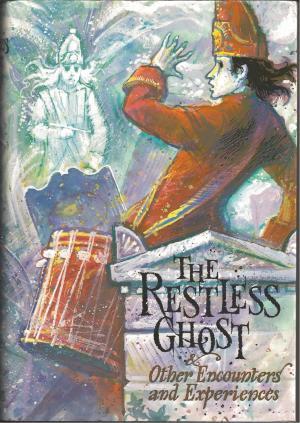

There's an early Alan Garner story called "Feel Free" included in Susan Dickinson's anthology The Restless Ghost and Other Encounters and Experiences (1970). I read it while I was at Intermediate School, but I've never seen it collected anywhere else.

I remember it surprised me quite a bit. It was too advanced and complex to be as satisfactory to me, then, as the other stories by the likes of Joan Aiken and Leon Garfield in the same collection. There was something very intriguing about it, though.

Susan Dickinson, ed. The Restless Ghost (1970)

The story begins with a boy, Brian, who is copying a design from an old plate in a small provincial museum:

The dish stood alone in its case, a typed label on the glass: "Attic Krater, 5th Century BC, Artist Unknown. The scene depicts Charon, ferryman of the dead, conveying a soul across the river Acheron in the Underworld."He persuades the curator to let him take it out for a moment:

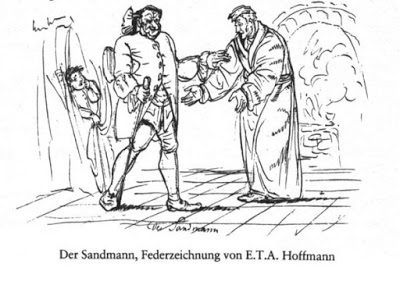

Anthony Maitland: "Feel Free" illustration (c.1970)

"Tosh, look!" Brian nearly dropped the dish. On the base was a clear thumb print fired hard as the rest of the clay.Tosh, the curator, is at first disposed to scoff. Eventually he admits: "Very close, I'll allow, but see at yon line across the other feller's thumb. That's a scar. You haven't got one."

"There he is," whispered Brian.

The change from the case to the outside air had put a mist on the surface of the dish, and Brian set his own fingers against the other hand.

"Two thousand year, Tosh. That's nothing. Who was he?

"No, he'll not have a headache."

Brian stared at his own print and the fossilled clay. "Tosh," he said, 'they're the same. That thumb print and mine. What do you make of it?

Brian is unconvinced: "But a scar's something that happens ... It's nothing to do with what you're born like. If he hadn't gashed his thumb, they'd be the same."

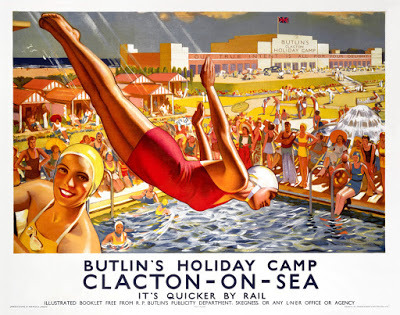

Butlins: Clacton-on-Sea (1940)

Later Brian meets his girlfriend Sandra for their date at the open day at the local holiday camp:

Hello! Hello! Hello! Feel free, friends! This is the Lay-Say-Far Holiday Camp, a totally new concept in Family Camping, adding a new dimension to leisure, where folk come to stay, play, make hay, or relax in the laze-away days that you find only at the Lay-Say-Fair Holiday Camp."Where shall we go on now?" asks Brian, after they've wandered around for a bit, and gone on most of the rides:

"There's the Tunnel of Love, if you're feeling romantic," said Sandra.The tunnel is predictably cheesy, but a little macabre as well:

"You never know till you try, do you?" said Brian.

Beyond the gate was a grotto of plaster stalactites and stalagmites, and the channel rushed among them to to a black tunnel.The heel of Sandra's shoe gets caught as she tries to climb in the boat, and he is unable to free it in time for her to join him:

"Queer green light there, isn't it?" said Sandra. "Ever so eerie."

She was swinging away from him, a tiny figure lost among stalactites. He stood, looking, looking and slowly lifted his hand off the nail that had worked loose at the edge of the stern. He had not felt its sharpness, but now the gash throbbed across the ball of his thumb. The boat danced towards the tunnel.

Tunnel of Love

I guess what I like, still, so much about this story is the way in which it manages to introduce all the characteristic themes Alan Garner is known for in such a short compass of time.

There's the idea of artefacts carrying baggage with them from the past (like the patterned plates in The Owl Service, or - even more so - the stone axe in Red Shift). There's also the (implicit) comparison between a dignified, layered past of cottage industries and individual destinies and the mass-produced, plastic present.

There's something uncomfortably prescient in the passage where Brian and Sandra sit together in the Willow Pattern Garden:

"No. Look, said Brian, and leant backwards to gather a handful of earth from a rockery flower bed. "Soil isn't muck, it's ... well, I'll be ... Sandra? This here soil's plastic."As it turns out, there are no bees to kill. "They were each mounted on a quivering hair spring, the buzzer plugged in to a time switch."

Smooth, clean granules rolled between his fingers.

"The whole blooming lot's plastic - grass, flowers, and all!"

"Now that's what I call sensible. It helps to keep the costs down," said Sandra. "And it doesn't kill bees."

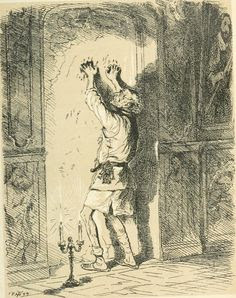

In someone else's hands, this could be quite a heavy-handed story. But Garner leaves an air of mystery about almost every aspect of it. Does the fact that Brian has now acquired a scar to match the one left on the ancient plate mean that he is going to join its owner as his own boat moves towards the dark mouth of the tunnel? There's certainly something a bit ominous about the fact that the pattern of the plate shows Charon the ferryman carrying souls to the land of the dead.

And then there's the title, "Feel Free." The point appears to be that while Brian may feel free, his actions are somehow predetermined by an inexorable, inescapable past. For all the wondrous patina on the artefacts in the old museum, they can exert an uncomfortable, even (possibly) an unhealthy influence on the present.

Brian and the other character's use of a few provincial turns of phrase also seemed pretty innovative to me when I read it first. Garner's characters move downwards in social level as his work progresses. Colin and Susan in his first two books talk standard English to the other characters' Cheshire dialect. The children in Elidor are closer to the working classes, but they still use something resembling received pronunciation.

Class becomes an issue for the first time in The Owl Service, but even there it's a more standard Middle-Class English / Working-Class Welsh contrast. After that, though, Garner's characters mostly speak in dialect, though there are always a few toffs around in the stories - reflecting their author's own divided identity, I guess.

The story, like the old Greek plate at its centre, is a small masterpiece: better than one has any right to expect in such a context. The museum, its curator, Brian himself, are sketched deftly, in a few strokes. Only the fun fair descends to caricature (Sandra, too, I fear: a typically unimaginative female who could have walked straight out of any story from the Angry Young Man era).

The focus really isn't on Sandra, though, it's on Brian: Brian whose sense of rightness and perfection in design has made him blind to the charms of the present, and predisposed him to flirtations with the dark past:

"Have you ever hidden anything to chance it being found again years and years later - perhaps long after you're dead?It's not hard to see the analogies here between Brian and his creator: Brian Walton / Alan Garner. Writers, too, bury things in the dark, hide them inside the containers they make: "You're talking to someone you'll never meet, never know: but if they find the bottle they'll know you."

"No," said Sandra.

"I have," said Brian. "I was a great one for filling screw-top bottles with junk and then burying them. I put notes inside, and pieces out of the newspaper. You're talking to someone you'll never meet, never know: but if they find the bottle they'll know you. There's bits of you in the bottle, waiting all this time, see, in the dark and as soon as the bottle's opened - time's nothing - and - and -"

"Eh up," said Sandra, "people are looking. You do get some ideas, Brian Walton!

Terracotta Perfume Flask: Charon (c.340 BC)

•

Susan Dickinson, ed.: The Restless Ghost: Acknowledgements

That may be a lot of significance to lay on one short, uncollected story - dating from 1968, if we can trust the acknowledgments section above - but if anything is apparent in Garner's work in general, it's that he expects each page, each line, each word even to do a great deal of work. It's no accident that his books tend to be short. The weight of significance each one of then bears is disproportionate to the number of pages: in that he has far more in common with a poet than a more conventional prose writer.

His publications to date fall into several discrete groups. Before continuing any of these trains of thought, I think I'd better outline just what we're talking about. First of all, both chronologically and in popularity, there are those books which - despite their increasing subtlety and complexity - still have to be thought of as primarily for children:

Alan Garner: The Weirdstone of Brisingamen (1960)

The Weirdstone of Brisingamen: A Tale of Alderley. 1960. London: William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., 1990.

Alan Garner: The Moon of Gomrath (1963)

The Moon of Gomrath. 1963. An Armada Lion. London: Collins, 1974.

Alan Garner: Elidor (1967)

Elidor. Illustrated by Charles Keeping. 1965. London: William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., 1971.

Alan Garner: The Owl Service (1967)

The Owl Service. 1967. An Armada Lion. London: Collins, 1974.

Alan Garner: Red Shift (1973)

Red Shift. 1973. London: Collins, 1973.

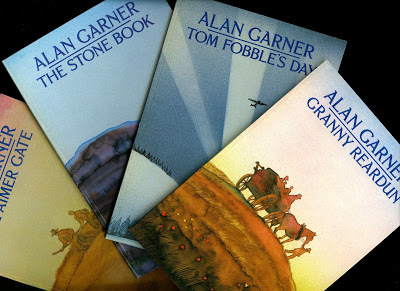

Alan Garner: The Stone Book Quartet (1976-78)

The Stone Book. The Stone Book Quartet. 1. 1976. Illustrated by Michael Foreman. Fontana Lions. London: Collins, 1979.

Tom Fobble’s Day. The Stone Book Quartet, 2. 1977. Illustrated by Michael Foreman. Fontana Lions. London: Collins, 1979.

Granny Reardun. The Stone Book Quartet, 3. 1977. Illustrated by Michael Foreman. Fontana Lions. London: Collins, 1979.

The Aimer Gate. The Stone Book Quartet, 4. 1978. Illustrated by Michael Foreman. Fontana Lions. London: Collins, 1979.

These six books (I think one can describe the Stone Book Quartet as a single work, despite its quite separate sections) range from the madcap magical adventurousness of The Weirdstone of Brisingamen to the terrifying intensities of The Owl Service with no diminution of quality at any point. Garner is one of those rare writers who is content only with masterpieces, and who constantly racks up the pressure with each new work.

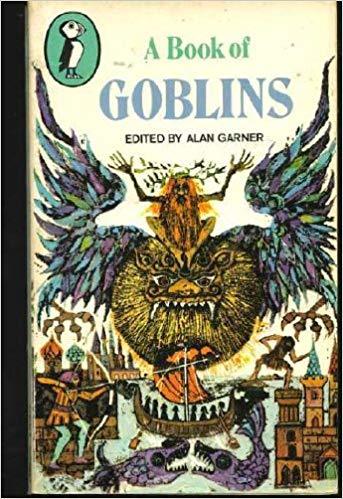

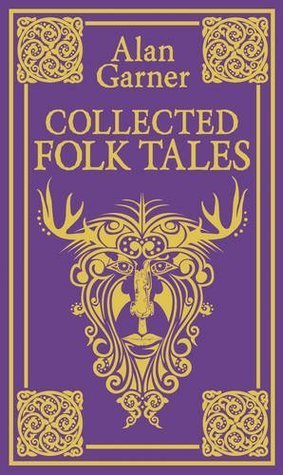

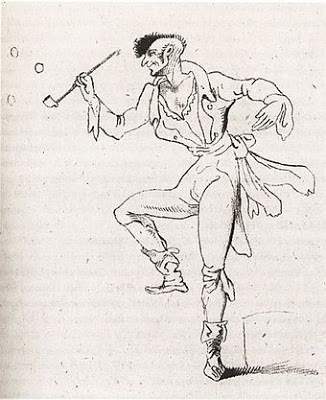

Alongside this very original sequence of imaginative works, though, there is a very different set of publications. I don't have all of these folktale anthologies and retellings, but this is most of them. They are quite exceptionally good of their kind, I would say, and I speak as one who has read more than his fair share of such books. The figure of the trickster appears to appeal particularly to Garner, and he writes of him brilliantly and (at times) quite disconcertingly:

Alan Garner: A Book of Goblins (1969)

Garner, Alan, ed. A Book of Goblins. Illustrated by Krystyna Turska. 1969. Puffin Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972.

Garner, Alan, ed. The Guizer: A Book of Fools. 1975. Fontana Lions. London: Collins, 1980.

Alan Garner's Book of British Fairy Tales. Illustrated by Derek Collard. 1984. London: Collins, 1988.

Garner, Alan, ed. A Bag of Moonshine. 1986. Lions. London: HarperCollins, 1992.

Collected Folk Tales. London: HarperCollins Children's Books, 2011.

Alan Garner: Collected Folk Tales (2011)

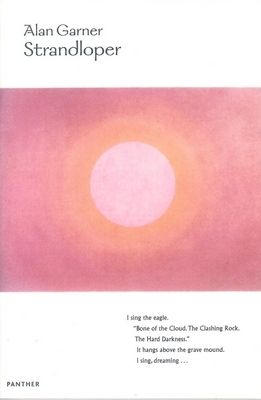

Which brings us to his novels for grown-ups. Or at least I suppose that's who they're for. They require such careful, attentive reading, that I guess they're for anyone prepared to invest in them fully.

The first, in particular, is another masterpiece. And while one can recognise many elements of the earlier Garner of the 'Weirdstone' books: the obsession with Alderley Edge, for instance, Strandloper is really sui generis as a novel. It is, among other things, the work of someone determined to reinvent himself wholly for each new project - a pretty terrifying prospect for other, more workaday writers.

Alan Garner: Strandloper (1996)

Strandloper. 1996. London: The Harvill Press, 1997.

Alan Garner: Thursbitch (2003)

Thursbitch. 2003. London: Vintage, 2004.

Alan Garner: Boneland (2012)

Boneland. Fourth Estate. London: HarperCollins Publishers, 2012.

The last of these is the oddest and - to my mind - probably the least successful. It attempts to close off the 'Weirdstone' trilogy, fifty years after it was begun. And yet it's hard to see exactly who it was written for. Certainly not for the children who enjoyed those adventurous encounters with magicians and dwarves.

Neither is it really for admirers of his previous two novels, though it shares many features with them: allusiveness in place of direct utterance, absence of affect where one would most expect it, and intricate pattern-making of an almost Celtic, Book of Kells-like, nature.

Which brings us to the last set of books. His recent memoir and his book of essays:

Alan Garner: The Voice that Thunders (1997)

Non-fiction:

The Voice That Thunders: Essays and Lectures. London: The Harvill Press, 1997.

Where Shall We Run To? A Memoir. London: Fourth Estate, 2018.

Alan Garner: Where Shall We Run To? A Memoir (2018)

The picture these two books paint of their author is not an entirely positive one. The memoir concerns only his early childhood, before he went off to Grammar School, and contains little more compromising than the revelation that his 'scientific' curiosity about the effects of dock-leaves on nettle stings inspired him to push one of his friends, Harold, into a field of them at one point:

I'd not heard a boy scream before. It went on. It didn't stop. It wasn't Harold. I ran. I ran all the way home, up the stairs, fell on my bed, and yelled and yelled, still hearing the scream in my head, and cried and cried; but I hadn't got any dock-leaves.The book is constructed in a curiously spiral manner. It concludes with a few late anecdotes (one about Harold), but the narrative proper ends with the author sitting the eleven-plus examination in Manchester. We've already heard the results of this at the end of chapter two, shortly after the nettling incident, however:

The next day, Harold called me a daft beggar and a mucky pup.

A letter came for me in the post some time after, and my mother was waiting for me at the end of School Lane when lessons were over. She told me I'd won a scholarship.In a sense, it's clear that everything Alan Garner has written since - all the novels, the essays, even the retellings of folktales - has been one long attempt to understand this moment when something went and did not come back.

That evening, the gang were playing round the sand patch. It was Ticky-on-Wood. Harold's mother came out of the house. Her face was different. 'Well, Alan,' she said, 'you won't want to speak to us any more.'

I didn't understand. I felt something go and not come back.

•

Published on November 16, 2018 19:02

November 10, 2018

11th Hour of the 11th Day of the 11th Month

P.J. Hammond: Sapphire and Steel: The Railway Station (1979)

Perhaps all wars require a mythic dimension to put alongside their otherwise irredeemable horror and brutality. The abduction of Helen by Paris adds a romantic sheen to what may actually have been a protracted struggle between the Achaean and Hittite Great Kings over trade access to Asia Minor.

In Homer's version of the Trojan War, of course, the irony of the whole thing lies in the fact that Helen is back as reigning Queen of Sparta by the beginning of the Odyssey, and is clearly inclined to see the whole thing as a youthful bagatelle. There's a slight edge to it all still, though.

In her version, she was the only one to recognise Odysseus when he entered the besieged city disguised as a beggar, and aided him in his mission, having (by then) repented her past indiscretions:

... since my heart was already longing for home, and I sighed at the blindness Aphrodite had dealt me, drawing me there from my own dear country, abandoning daughter and bridal chamber, and a husband lacking neither in wisdom nor looks.Her husband Menelaus's account is, to say the least, a little different. He sees her as, if not an active collaborator with the Trojans, at any rate somewhat ambivalent in her support of the Greeks:

You circled our hollow hiding-place, striking the surface, calling out the names of the Danaan captains, in the very voices of each of the Argives’ wives. Diomedes, Tydeus’ son, and I, and Odysseus were there among them, hearing you call, and Diomedes and I were ready to answer within, and leap out, but Odysseus restrained us, despite our eagerness. [Odyssey 4, 220-89]The Allied soldiers who fought at Gallipoli, just across the straits from Hissarlik, the probable site of ancient Troy, were by no means unaware of these parallels. Their classically trained young officers were, indeed, preoccupied by the subject - possibly to the exclusion of other, more vital, concerns.

Jean Giraudoux: La Guerre de Troie n'aura pas lieu

[The Trojan War will not take place] (1935)

Take, for instance, Patrick Shaw-Stewart's famous poem "Achilles in the Trench":

I saw a man this morningThe poem is valorised not only by those remarkable last two lines, but also by its author's own death, on active service, in 1917. I suppose what it's always recalled to me, though, rather than all of Achilles' dazzling deeds in the Iliad, are the last words we hear in his own voice, when he encounters Odysseus on his own journey to the Underworld:

Who did not wish to die;

I ask, and cannot answer,

if otherwise wish I.

Fair broke the day this morning

Upon the Dardanelles:

The breeze blew soft, the morn's cheeks

Were cold as cold sea-shells.

But other shells are waiting

Across the Aegean Sea;

Shrapnel and high explosives,

Shells and hells for me.

Oh Hell of ships and cities,

Hell of men like me,

Fatal second Helen,

Why must I follow thee?

Achilles came to Troyland

And I to Chersonese;

He turned from wrath to battle,

And I from three days' peace.

Was it so hard, Achilles,

So very hard to die?

Thou knowest, and I know not;

So much the happier am I.

I will go back this morning

From Imbros o'er the sea.

Stand in the trench, Achilles,

Flame-capped, and shout for me.

Odysseus, don’t try to reconcile me to my dying. I’d rather serve as another man’s labourer, as a poor peasant without land, and be alive on Earth, than be lord of all the lifeless dead. [Odyssey 11, 465-540]

Kurz & Allison: First Battle of Bull Run (1861)

The American Civil War famously began in Wilmer McLean's front yard and finished in his back parlour.

McLean, a wholesale grocer, was so appalled by the experience of having his farm fought over in the first major engagement between the Union and Confederate armies, that he relocated his family in 1863. Unfortunately, the place he chose, an obscure little hamlet called Appomattox Courthouse, turned out to be the location of Robert E. Lee's surrender to Ulysses S. Grant in 1865.

Wilmer McLean's two houses (1861 & 1865)

That's what I mean by a mythic dimension. There's no real meaning in this strange coincidence, but it seems to betoken some kind of cosmic symmetry in things: a design behind all the relentless bloodshed human beings seem determined to mete out upon one another.

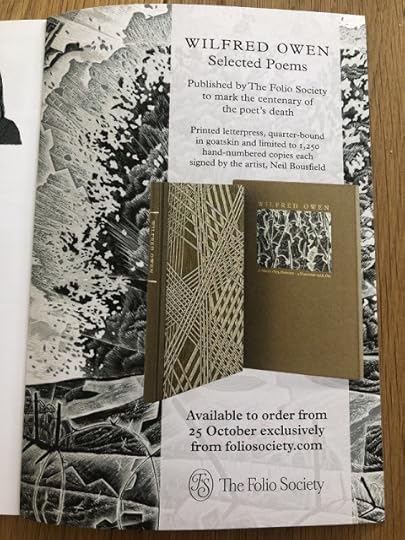

Wilfred Owen: Selected Poems (2018)

Another, of course, is the awful fatality of Wilfred Owen's life and death. He died, on the 4th of November 1918 - almost exactly one hundred years ago - in an assault on the Sambre–Oise Canal. However, as the Folio Society are at pains to remind us in the advertisement for their sumptuous new illustrated edition of his selected poems:

... his parents received the telegram announcing his death on 11 November itself, just as the church bells rang out in Shrewsbury to mark the end of the Great War.There lies the apparent design. The poet who wrote in the draft preface to his as yet unpublished poems:

This book is not about heroes. English Poetry is not yet fit to speakcould somehow not be permitted to survive the war. Like Abraham Lincoln, or Achilles himself, he had to fall victim to it in order to achieve his full status as a sacrificial victim.

of them. Nor is it about deeds or lands, nor anything about glory, honour,

dominion or power,

Except War.

Above all, this book is not concerned with Poetry.

The subject of it is War, and the pity of War.

The Poetry is in the pity.

"He died that we may live." That's the kind of unctuous platitude that tends to come out on these occasions. And yet, it's hard to avoid a sense of strangeness about the whole thing, about the idea that the author of "Anthem for Doomed Youth" could not himself be allowed to outlive the war that turned him into perhaps the greatest of all war poet since Homer.

Mary Renault: The King Must Die (1958)

Mary Renault perhaps puts it best, in her novel The King Must Die (about the myth of Theseus), where she tries to explain the Ancient Greek concept of moira as:

The finished shape of our fate, the line drawn round it. It is the task the gods allot us, and the share of glory they allow; the limits we must not pass; and our appointed end. Moira is all these things."The king must go willingly, or he is no king." Whether it is Abraham Lincoln going to Ford's Theatre to show himself to the public one last time, Wilfred Owen refusing to accept non-active service away from the Front Line, or Achilles weeping with Priam over the body of Hector, there is something superhuman about all these noble, almost transcendent gestures.

The armistice itself is replete with legends: many of them clustering around the strange symmetry of "the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month."

Sapphire and Steel (1979)

In the cult British TV Sci-fi classic Sapphire and Steel, for instance (pictured at the head of this post), the storyline called "The Railway Station" concerns an out-of-the-way deserted railway platform haunted by a First World War soldier.

The precise nature of his grievance, and the reason he's been able to gather so many other disgruntled souls around him, hinges on the armistice: specifically, on the equation he keeps on drawing on the windows of the building:

11 / 11 / 11 / 11 = 18It turns out that he was killed eleven minutes into that eleventh hour, and was thus an altogether unnecessary sacrifice to the gods of war.

Thomas Keneally: Gossip from the Forest (1975)

An even more complex set of ironies is explored in Thomas Keneally's 1975 novel Gossip from the Forest (subsequently made into a powerful, atmospheric film), about the German deputation sent to negotiate the surrender, and the subsequent murder by a right-wing fanatic of their leader, politician Matthias Erzberger, whilst walking in the Black forest a few years later.

From the Forest of Compiègne to the Black Forest, in fact.

Lady Ottoline Morrell: Siegfried Sassoon and Robert Graves (1920)

I don't mind admitting, though, that my favourite of all of the poetic moments associated with the armistice is the one recorded in Siegfried Sassoon's great poem "Everyone Sang":

Everyone suddenly burst out singing;

And I was filled with such delight

As prisoned birds must find in freedom,

Winging wildly across the white

Orchards and dark-green fields; on - on - and out of sight.

Everyone's voice was suddenly lifted;

And beauty came like the setting sun:

My heart was shaken with tears; and horror

Drifted away ... O, but Everyone

Was a bird; and the song was wordless; the singing will never be done.

Sassoon survived. He went on to write many (mostly disappointing) further volumes of poems, but also a wonderful series of war memoirs and autobiographies. He got married, had a son, lived a long life. So let's not get too beguiled by the beautiful symmetries and high-mindedness of these seductive legends:

It is well, as Robert E. Lee said, that war is so terrible. We should grow too fond of it.

Robert E. Lee & Traveller (1865)

Or, as the somewhat more mordant A. E. Housman said in his "Epitaph on an Army of Mercenaries":

These, in the day when heaven was falling,

The hour when earth's foundations fled,

Followed their mercenary calling,

And took their wages, and are dead.

Their shoulders held the sky suspended;

They stood, and earth's foundations stay;

What God abandoned, these defended,

And saved the sum of things for pay.

A. E. Housman (1859-1936)

Published on November 10, 2018 14:00

November 3, 2018

Classic Ghost Story Writers (5): Colin Wilson

Colin Wilson (1957)

I used to feel a bit ashamed of reading books by Colin Wilson. They definitely fall into the 'guilty pleasures' category. As you can see from the list below, I collected his fiction fairly assiduously up until the end of the 1970s, but then let the habit lapse.

I do have most of them, though - with the exception of the late 'Spider World' series (1987-2002), and a few others such as The Janus Murder Case (1984), The Personality Surgeon (1985), and the posthumous Lulu: an unfinished novel (2017).

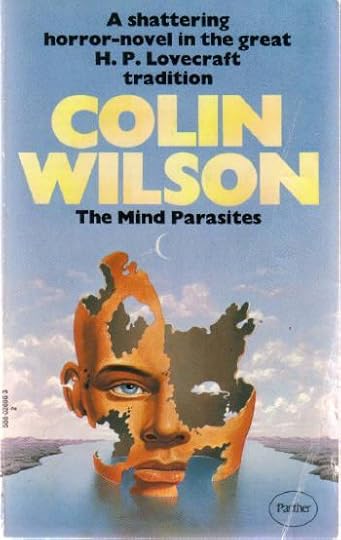

The first one I encountered - and it's still my favourite - was The Mind Parasites (along with, to a slightly lesser extent, its successors The Return of the Lloigor and The Philosopher's Stone).

I'm not quite sure why I liked it so much at the time. True, it was full of bookish information, and ended with one of those characteristic Campbell-era Sci-fi Man-plus resolutions, but there was an unmistakable zest about it.

Colin Wilson: The Mind Parasites (1967)

Fiction:

Ritual in the Dark. 1960. Panther Books. Frogmore, St Albans, Herts: Granada Publishing Limited, 1976.

Adrift in Soho. 1961. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1964.

The World of Violence. 1963. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1965.

Man Without a Shadow. 1963. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1966.

Necessary Doubt. 1964. London: Panther Books Ltd., 1966.

The Glass Cage: An Unconventional Detective Story. 1966. New York: Bantam Books, 1973.

The Mind Parasites. 1967. Berkeley, California: Oneiric Press, 1983.

'The Return of the Lloigor.' In Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos. Ed. August Derleth. 1969. London: Grafton, 1988. 439-501.

The Philosopher's Stone. 1969. Panther Books. Frogmore, St Albans, Herts: Granada Publishing Limited, 1974.

The God of the Labyrinth. 1970. Panther Books. Frogmore, St Albans, Herts: Granada Publishing Limited, 1977.

The Killer. 1970. Panther Books. Frogmore, St Albans, Herts: Granada Publishing Limited, 1977.

The Black Room. 1971. London: Sphere Books Ltd., 1977.

The Schoolgirl Murder Case. 1974. Panther Books. Frogmore, St Albans, Herts: Granada Publishing Limited, 1977.

The Space Vampires. Granada Publishing Limited. Frogmore, St Albans, Hertfordshire: Hart-Davis, MacGibbon Ltd., 1976.

'A Novelization of Events in the Life and Death of Grigori Efimovich Rasputin.' In Tales of the Uncanny. New York: The Reader’s Digest Association, Inc., 1983. 487-606.

Colin Wilson: The Philosopher's Stone (1969)

Already, though, I could see some of the features of Wilsonian fiction in general: the weird lack of affect, of any attempt to convey an atmosphere of reality - an atmosphere of anything, really, except people reading books and meeting other people to plan meeting more people to talk about the books and the ideas in them.

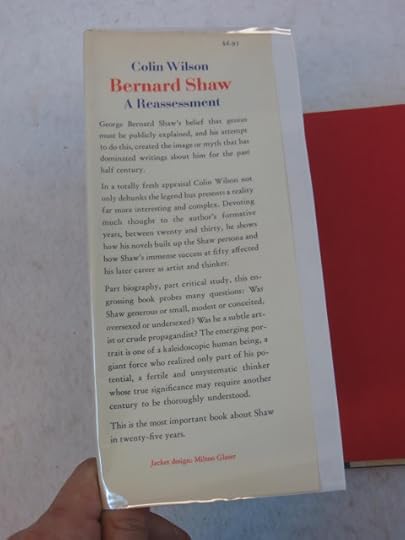

One might charitably call it Shavian, after one of his greatest influences, George Bernard Shaw. He too, eschews stylistic and tonal effects in favour of raw ratiocination.

Colin Wilson: Bernard Shaw: A Reassessment (1969)

The thing about Shaw, though, is that he makes difficult ideas sound simple. He has a lot of sensible things to say about a great many features of the world around him. Colin Wilson really only has one idea, dished up again and again in slightly different forms.

That idea is (in its simplest form) that we don't use our brains to the uttermost - that if there were some way in which we could protract and/or artificially induce what psychologist Abraham Maslow called "peak experiences," then mankind could be transformed.

Now whether or not this is a good idea is beside the point. Maslow denied the possibility that the euphoria of peak experiences could be brought on in such a way, but Wilson was convinced that he was wrong. Most of his - very extensive - work on the occult was concerned with whether or not certain mystics and clairvoyants had succeeded in doing so.

His interest in H. P. Lovecraft was mainly to denounce him as an enemy of this "positive" vision of life. That is, until he started writing Lovecraftian fiction himself, after which he used the mechanics of the Cthulhu Mythos to promote the idea of - guess what? - peak experiences, only by now he'd started calling them "faculty x."

Colin Wilson: Peak Experiences and the New Human (1993)

Wilson was an appallingly prolific writer. There were, no doubt, many reasons for this: the need to make a living on book advances must have constituted a considerable temptation to pitch an endless series of books to his publishers (many of them thinly disguised re-hashes of what had gone before).

Colin Wilson: The Outsider (1956)

In critical terms, however, this is what doomed him to the literary fringes. The reviewers who'd hailed his first work The Outsider (1956) as an amazing piece of cultural insight, written by a 24-year-old working-class genius, were somewhat disconcerted to see Religion and the Rebel come thumping down the book-chute the very next year. They began to suspect they'd been had.

In reality, of course, The Outsider was not nearly as original and ground-breaking as they'd thought. It's a sign of the shallowness of British book culture of the time that names such as Dostoyevsky and Hamsun and Rilke, mentioned by a man who'd clearly actually read them, seemed unduly impressive to a great many of these half-educated bigmouths. But then, its successors weren't nearly as bad as they claimed either.

Wilson's first six books, known collectively as "The Outsider Cycle": Religion and the Rebel (1957), The Age of Defeat (1959), The Strength to Dream (1962), Origins of the Sexual Impulse (1963), Beyond the Outsider (1965) and the summary volume Introduction to the New Existentialism (1966) may sound a bit monotonous at times, but they did introduce readers to one of his most considerable virtues: the ability to summarize other people's books and ideas clearly and interestingly - albeit at great length.

You may see this as a journalistic rather than a strictly writerly skill - but it does explain why even Wilson's more reluctant fans (such as myself) are prepared to lend shelf room to so many of his tomes.

Speaking personally, I could give a shit about 'faculty x'. None of the stuff he says about it seems to me to make it sound more than an agreeable fairy tale. He always cranks round to it sooner or later, though - except, perhaps, in some of his later, more unabashedly commercial, compilations, such as the 1991 Mammoth Book of the Supernatural, 'edited' by his son Damon Wilson, who also co-wrote a number of these late works. That particular tome, despite its considerable size, didn't even make it to the (admittedly rather flawed) listings on Wikpedia's Colin Wilson Bibliography page).

Colin Wilson: The Occult: A History (1971)

His bestselling book The Occult (1971) and its sequels Mysteries (1978) and Beyond the Occult (1988), as well the host of others on telemetry, past lives, poltergeists, After-death experiences, etc. etc. consist mainly of retellings of classic ghost stories and other strange happenings. That's why they're so very entertaining to read.

The Essential T. C. Lethbridge (1980)

If you've tried the experiment of going from Wilson's version to the actual published work it was based on (as I have in the case of T. C. Lethbridge), you find just how grossly he simplifies, and how blatantly he bends their insights to fit in with his vision of a 'faculty x' dominated universe. This is bad.

Catherine Crowe: The Night-Side of Nature (1848)

On the other hand, however, I would probably never have encountered T. C. Lethbridge, or Catherine Crowe, or Atlantis theorist Rand Flem-Ath, or a host of other fascinating people and writers without the nudge given me by Colin Wilson's many, many works of summary and synthesis. It may not make him a great mind, but it certainly makes him a benefactor of a sort.

Harry Ritchie: Success Stories (1988)

Of course, there will always be mockers and scoffers who see Colin Wilson as a bit of a fraud or even (what's worse) a joke. If you'd like to read the case for the prosecution, I do recommend the very amusing chapter on Wilson and his acolytes (principally novelist Bill Hopkins and pop philosopher Stuart Holroyd) in Harry Ritchie's 1988 book Success Stories: Literature and the Media in England, 1950-1959 (conveniently summarised in this 2006 article):

[When he] handed his journals over to the Daily Mail [in December 1956] ... Wilson's private thoughts made for juicy copy. "The day must come when I am hailed as a major prophet," was one quote. "I must live on, longer than anyone else has ever lived ... to be eventually Plato's ideal sage and king ..."Harry Ritchie is okay in my book. I met him once in a pub, and he insisted on shaking me by the hand when he heard that I was the only other human being he'd ever met who'd actually heard of, let along read Kingsley Amis's first book of poems Bright November (1947). I'm not sure if I dared to admit to him that I actually had a xeroxed copy of the book shelved with all my other Amis-iana at home in New Zealand ...

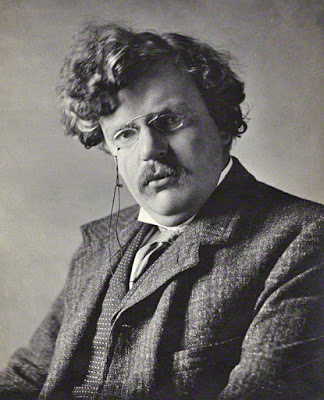

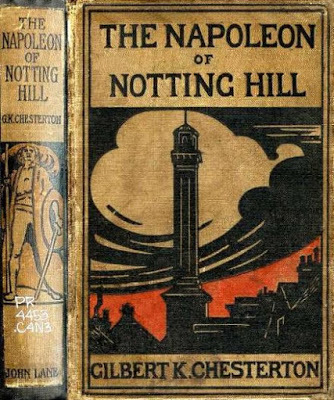

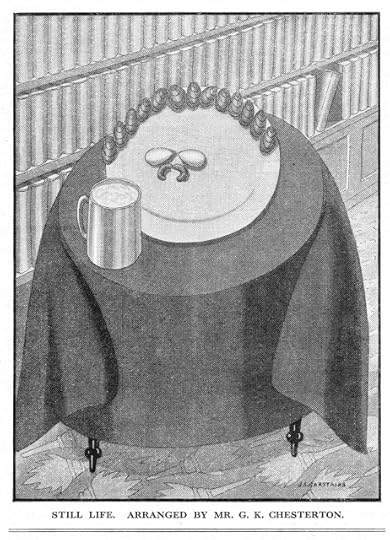

Is Ritchie right about Wilson? Objectively, I fear he may well be. But that doesn't really account for the fact that I've had so much pleasure reading about obscure supernatural events in the endless pages of Wilson's stream-of-consciousness reading-notebooks-in-the-form-of-individually-titled-volumes. As one of G. K. Chesterton's characters once remarked (in his first novel The Napoleon of Notting Hill):

Next to authentic goodness in a book ... we desire a rich badness.Wilson may be, in many ways, a bad writer, but it is a rich badness - and, really, who, even (I was about to write 'especially') among geniuses, isn't a bad writer at times?

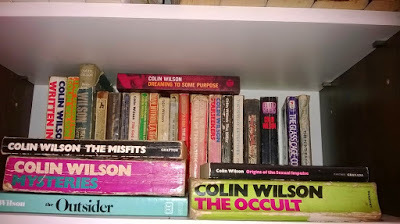

So here it is, then, in all its glory, my own private library of Colin Wilsoniana. You'll note that it even includes a few of his many books on murder and serial killers, but that aspect of his interests I don't share at all. It's the occult and paranormal investigation stuff that really fascinates me:

•

A Colin Wilson library

Colin Henry Wilson

(1931-2013)

Non-fiction:

The Outsider. 1956. Pan Piper. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1963.

Religion and the Rebel. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1957.

[with Patricia Pitman]: Encyclopedia of Murder. 1961. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1964.

The Strength to Dream: Literature and the Imagination. 1962. Abacus. London: Sphere Books Ltd., 1982.

Origins of the Sexual Impulse. 1963. London: Panther Books Ltd., 1966.

Rasputin and the Fall of the Romanovs. 1964. Panther Books. Frogmore, St Albans, Herts: Granada Publishing Limited, 1977.

Colin Wilson On Music (Brandy of the Damned). 1964. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1967.

Beyond the Outsider. 1965. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1966.

Voyage to a Beginning: A Preliminary Autobiography. Introduction by Brocard Sewell. London: Cecil and Amelia Woolf, 1969.

The Occult: A History. 1971. New York: Vintage Books, 1973.

Order of Assassins: The Psychology of Murder. 1972. Panther Books. Frogmore, St Albans, Herts: Granada Publishing Limited, 1975.

Strange Powers. 1973. London: Abacus, 1975.

Tree by Tolkien. Santa Barbara, CA: Capra Press, 1974.

Mysteries: An Investigation into the Occult, the Paranormal and the Supernatural. 1978. London: Granada Publishing, 1979.

Starseekers. 1980. London: Granada Books, 1982

Poltergeist! A Study in Destructive Haunting. London: New English Library, 1981.

The Psychic Detectives: The Story of Psychometry and Paranormal Crime Detection. London & Sydney: Pan Books, 1984.

Afterlife: An Investigation of the Evidence for Life after Death. London: Harrap, 1985.

Beyond the Occult. London: Guild Publishing, 1988.

The Mammoth Book of the Supernatural. Ed. Damon Wilson. London: Robinson Publishing, 1991.

[with Damon Wilson]: World Famous Strange Tales & Weird Mysteries. London: Magpie Books Ltd., 1992.

[with Damon Wilson & Rowan Wilson]: World Famous Scandals. London: Magpie Books Ltd., 1992.

From Atlantis to the Sphinx. London: Virgin Books, 1996.

Ghost Sightings. Strange But True. Sydney: The Book Company, 1997.

[with Rand Flem-Ath]: The Atlantis Blueprint. 2000. London: Warner Books, 2001.

•

Colin Wilson (2006)

Published on November 03, 2018 15:08

October 28, 2018

The Peripeteia of Frances Yates

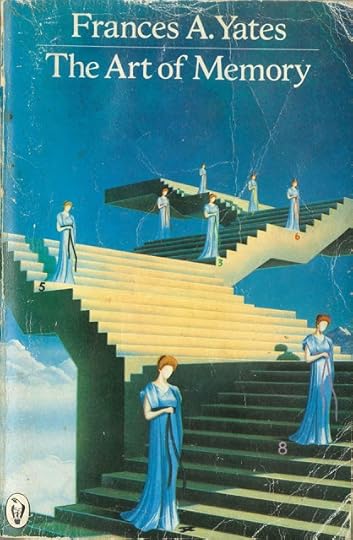

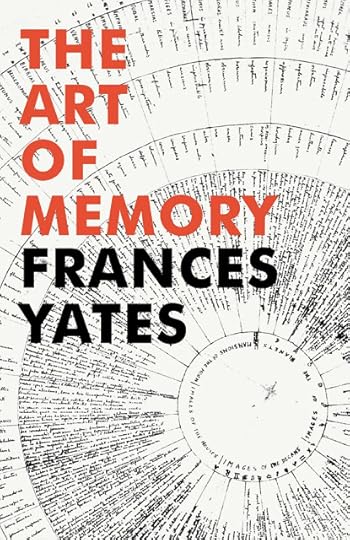

Frances Yates: The Art of Memory (1966)

And what, pray tell, does 'peripeteia' mean when it's at home?

a sudden reversal of fortune or change in circumstances, especially in reference to fictional narrativeis the best definition the online dictionary can provide.

I guess, in the case of Frances Yates, it refers to her transformation from an immensely learned but fairly dry-as-dust scholar of the intellectual life of the sixteenth and seventeenth century in Europe (with particular reference to the flourishing of hermetic and magical discourses in the allegedly proto-scientific late Renaissance) into a kind of pop culture guru: the High Priestess of the more respectable side of New Age Occultism.

Dame Frances Amelia Yates (1899-1981)

Southsea, Portsmouth

Her earlier books, on John Florio, the first translator of Montaigne into English (1934); Shakespeare (Love's Labour's Lost, 1936), and such apparently recondite subjects as The French Academies of the Sixteenth Century (1947) and The Valois Tapestries (1959), gave few signs of what was to come.

Reviewers were cautious about some of her 'wilder' conjectures, but for the most part she appeared just another habitué of Aby Warburg's superb library, transferred to England to avoid Nazi repression in 1933, and (as the Warburg Institute), affiliated with the University of London in 1944.

Frances Yates and the Hermetic Tradition (2008)

John Florio: The Life of an Italian in Shakespeare's England. 1934. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

A Study of Love's Labour's Lost. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1936.

The French Academies of the Sixteenth Century. 1947. London: Routledge, 1989

The Valois Tapestries. 1959. London: Routledge, 2010.

A Study of Love's Labour's Lost (1936)

The sea-change came with her next two publications: the double-whammy of Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition (1964) and The Art of Memory (1966). Wow! Talk about time, place and opportunity all coming together.

It was the age of The Morning of the Magicians (UK, translated as 'The Dawn of Magic': 1963 / US: 1964), Louis Pauwels' and Jacques Bergier's 1960 bestseller about the wilder side of twentieth century occultism. It all sounds familiar enough nowadays, but at the time most people had never even heard of the 'Vril Society' or the 'Thule Spceity" - let alone their philosophical connections with Nazism.

Le Matin des magiciens mixed up information about "conspiracy theories, ancient prophecies, alchemical transmutation, a giant race that once ruled the Earth, and the Nazca Lines" into what (in retrospect) seems a kind of blueprint for New Age nuttiness generally. Some of it may actually have been true, mind you.

It's not, I hasten to say, that Frances Yates's serious study of the memory systems of Ramon Lull and Giordano Bruno, and of the Renaissance Hermetic tradition generally had anything in common intellectually with Pauwels and Bergier's rather formless compendium of mid-twentieth century bugaboos and conspiracy theories, but it's impossible to deny that the same readers were attracted to both.

The Art of Memory in particular, outmoded though it may be in some few particulars fifty years after its publication, remains one of the most exciting books of intellectual history I've ever read. Its devotees are many, and the number of memory system addicts it has spawned must be many (even TV mentalist Derren Brown has claimed to practise its precepts).

Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition (1964)

Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition. 1964. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul / Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 1982.

The Art of Memory. 1966. A Peregrine Book. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978.

The Art of Memory (1966)

All of which brings me to the second meaning of peripeteia in my title above.

I wish I could date it precisely, but it must have been sometime in the mid-1980s that I was browsing through Anah Dunsheath's Rare Books on High Street, when I stumbled across a little pile of books shoved to one side of the entrance to her shop.

They were, in fact, four. As well as the two books mentioned directly above, there were also:

Lull and Bruno (1982)

Frances Yates. Lull and Bruno. Collected Essays 1 (of 3). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1982.

Scott, Walter, ed. & trans. Hermetica: The Ancient Greek and Latin Writings which Contain Religious or Philosophic Teachings Ascribed to Hermes Trismegistus. Vol. 1: Introduction / Texts and Translation. 4 vols. 1924. Boulder: Hermes House, 1982.

Hermetica, vol. 1 (1982)

All in all, it looked as if some budding Occultist had bought a bunch of exciting looking books about all sorts of esoteric matters, and had either found them too boring and abstruse for their taste, or else found a more desperate need for ready cash. Reader, I bought them.

Bought them and took them home with me and immediately started in on The Art of Memory and, really, nothing has been the same for me ever since. It was just so strange and fascinating: it gave an entirely new angle on classical antiquity, on figures as well known as Simonides and Cicero, but then - in the later chapters - it completely overturned any notions I'd had that Giordano Bruno had been a martyr to science, or that any number of my Renaissance heroes had been devoted to "reason" in any modern sense of the term.

It was, I must confess, a long time before I read the first part of her diptych, Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, which seemed to me then (it doesn't now) a bit anticlimactic after the highs of The Art of Memory. Nor did I get very far with the rather boring translation of the Hermetica. The book of essays, Lull and Bruno, was very good value indeed, though, and offered a whole series of new perspectives on this matter of the Hermetic tradition.

There is a certain amount about Ramon Lull in The Art of Memory, but the essays collected here gave a glimpse of her mind at work: her painstaking way of collecting evidence, venturing conjectures, and building on them to make immensely pleasing - if not always entirely convincing - wholes.

Anyone who's at all familiar with my own fiction (a somewhat select group, admittedly) will have observed the pervasive Yatesian influence. It's particularly strong in my first two novels, Nights with Giordano Bruno (the title is a bit of a giveaway), and The Imaginary Museum of Atlantis (which lent its name to this blog), but also in the novella Trouble in Mind (2005).

After that the fever subsided a bit, but Frances Yates still is my go-to gal when it comes to any kind of abstruse or coded information. Her work has its ups and downs, definitely, but basically I consider her both completely intellectually honest and greatly gifted creatively - the models she came up so regularly with in her works of intellectual history have a huge mythopoetic force to them.

Her later work is more of a mixed bag. It was assured of a much wider sale than most historians of ideas enjoy, which led to jealousy from less fortunate colleagues. It also, at times, advanced some rather dubious conjectures on such subjects as the underlying design of Shakespeare's Globe theatre, and the precise influences at work in the court of King Frederick of Bohemia (whose ousting from the throne led directly to the Thirty Years War in Germany).

Here are her five late books, copies of all of which I've collected along the way:

Theatre of the World (1969)

Theatre of the World. 1969. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1969.

The Rosicrucian Enlightenment (1972)

The Rosicrucian Enlightenment. 1972. A Paladin Book. Frogmore, St Albans: Granada Publishing Ltd., 1975.

Astrea (1975)

Astraea: The Imperial Theme in the Sixteenth Century. 1975. Ark Paperbacks. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1985.

Shakespeare's Last Plays (1975)

Shakespeare's Last Plays: A New Approach. 1975. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1975.

The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age (1979)

The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age. 1979. Ark Paperbacks. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1983.

It's hard to avoid the conclusion that she was having fun in these last books. They touch on all the themes dear to her heart, and they're all exhaustively researched, and yet they're not quite so convincing as the best of her mature work. The Rosicrucian Enlightenment, in particular, is a dazzling read. Whether or not "Christian Rosenkreuz" and the various strange letters circulating around the continent in the early seventeenth century can really be explained by reference to the politics of the Holy Roman Empire may seem doubtful at times, but certainly nobody else has succeeded in making more sense of that strange tangle of esoteric philosophy and partisan religious politics.

Similarly, I'm not sure that she proves her point about the shape and structure of Shakespeare's various theatres, but she brings in Robert Fludd, John Dee, and an awe-inspiring range of learning which gives one some idea of just how complex and delightful such intellectual puzzles can be.

Nowadays, of course, these things have been vulgarised and made ridiculous by such absurd gallimaufries of half-digested platitude and pointless factoid as The Da Vinci Code and its progenitor The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail. When Yates was writing, though, one could still theorise without the haunting shadow of Indiana Jones, Robert Langdon, and Benjamin Gates (from National Treasure).

By contrast, it's never safe to assume that Yates has gone out too far on a limb, or that she doesn't really know what she's talking about. All of her books, in the final analysis, constitute tentative suggestions for future researchers in the field. She's no crank, but is always evidence-driven and willing to change her mind as and when new facts and theories emerge.

I've often dreamed of completing my Frances Yates collection: buying up all the older books I don't have, as well as the remaining volumes in her collected essays. They are quite expensive, for the most part, though, so I guess I'm still waiting for some blessed windfall like that day 35-odd years ago when I bent over to look at a stack of dusty-looking books on Anah Dunsheath's floor.

Frances Yates: Renaissance and Reform: The Italian Contribution (1983)

Lull and Bruno. Collected Essays, vol. 1 of 3 (1982)

Renaissance and Reform: The Italian Contribution. Collected Essays, vol. 2 of 3 (1983)

Ideas and Ideals in the North European Renaissance. Collected Essays, vol. 3 of 3 (1984)

Frances Yates: Ideas and Ideals in the North European Renaissance (1984)

•

Dame Frances Yates

Published on October 28, 2018 20:06

October 26, 2018

Classic Ghost Story Writers (4): H. P. Lovecraft

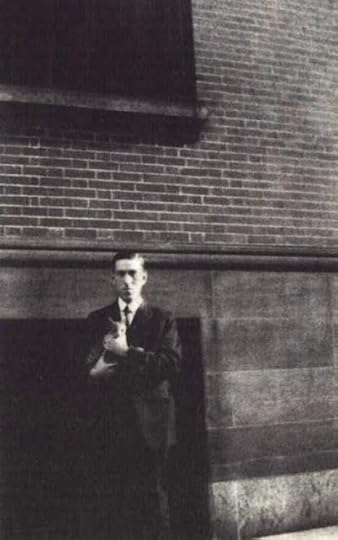

H. P. Lovecraft and friend

It's tempting to be facetious about the strange worlds of H. P. Lovecraft, "the twentieth century horror story's dark and baroque prince," as Stephen King famously described him.

I think a quick peek at the picture above will cure you of any notion that Howard Phillips Lovecraft (1890-1937) was gifted with much of a sense of humour. Life, for him, was a terrifying and frustrating business.

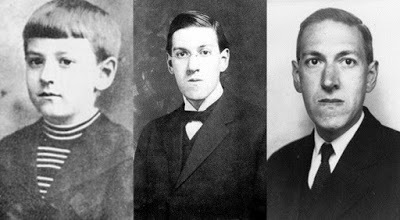

Here's a little photo-montage to enable you to visualise him more clearly:

Three faces of H. P. Lovecraft

What kind of a writer was he? An over-the-top, boots-and-all, pedal-to-the-metal user of every adjective and adverb under the sun to get the extreme effects he craved. His prose may not always be pretty, but it does have a certain brute effectiveness to it.

Here's an example of his early fantasy writing, "The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath," a long novella deeply indebted to Lord Dunsany:

Well did the traveler know those garden lands that lie betwixt the wood of the Cerenerian Sea, and blithely did he follow the singing river Oukranos that marked his course. The sun rose higher over gentle slopes of grove and lawn, and heightened the colors of the thousand flowers that starred each knoll and dangle. A blessed haze lies upon all this region, wherein is held a little more of the sunlight than other places hold, and a little more of the summer's humming music of birds and bees; so that men walk through it as through a faery place, and feel greater joy and wonder than they ever afterward remember.

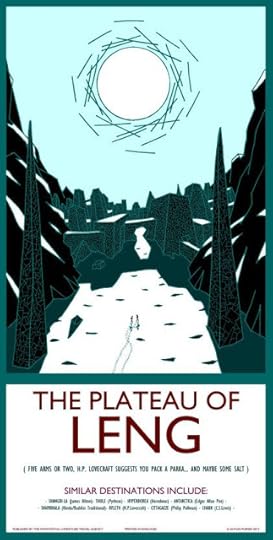

The Plateau of Leng

And here's a piece of his more mature writing:

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

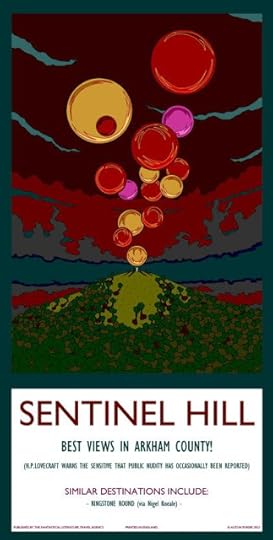

Sentinel Hill

I guess what those of us brought up on his stories relish most, though, are the fragments of unknown, hellish languages he liked to mix into his stories. Here's a wonderful example from 'The Shadow over Innsmouth', cunningly blended with New England dialect:

"Yield up enough sacrifices an' savage knick-knacks an' harbourage in the taown when they wanted it, an' they'd let well enough alone. Wudn't bother no strangers as might bear tales aoutside—that is, withaout they got pryin'. All in the band of the faithful—Order o' Dagon—an' the children shud never die, but go back to the Mother Hydra an' Father Dagon what we all come from onct—Iä! Iä! Cthulhu fhtagn! Ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah-nagl fhtagn—"

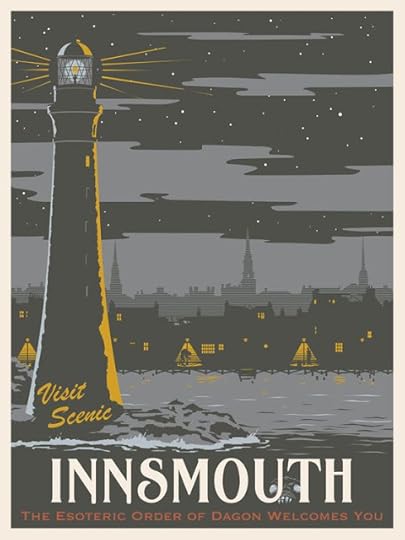

Steve Thomas: Innsmouth

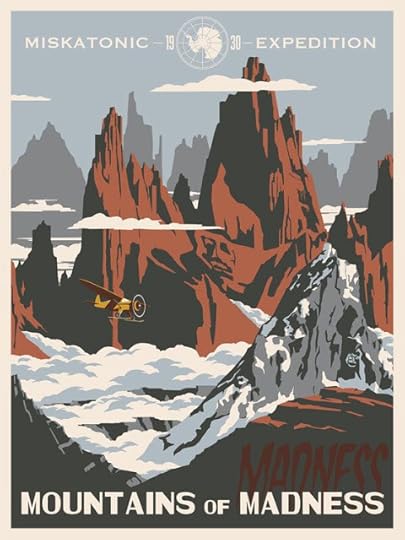

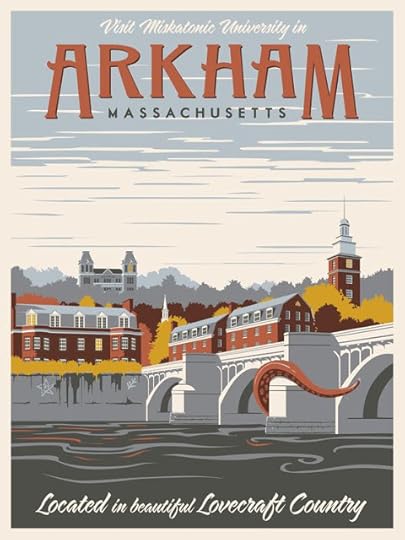

He's best known for his creation of a thing called the 'Cthulhu Mythos': a more-or-less consistent, interconnected mythology which gradually came into being in such stories as 'The Call of Cthulhu' and 'The Dunwich Horror,' and reached its full flowering in the late novel 'At the Mountains of Madness' and his final completed story 'The Shadow Out of Time'.

Steve Thomas: The Mountains of Madness

The artist Steve Thomas has created a series of mocked-up travel posters for particularly significant Lovecraftian destinations:

Steve Thomas: Arkham, Massachusetts

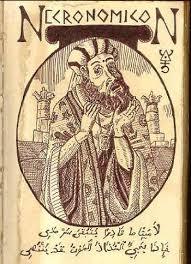

Chief among them, of course, is Arkham, Massachusetts, home of the Miskatonic University, whose library boasts a copy of that most recondite of volumes The Necronomicon, written by the mad Arab Abdul Alhazred, and a source of considerable inconvenience to everyone who encounters it, whether in the original or in its variously expurgated translations into a myriad of tongues.

Abdul Alhazred: The Necronomicon

Arkham (allegedly a blend of Salem, Massachusetts, and the author's hometown Providence, Rhode Island), has more than its fair share of demons, hauntings, empty graves, corpses with their faces gnawed off, spectral beasts, and even radioactive meteorites from outer space.

Nor is there any sense in pretending that Lovecraft was just playing around with these things for poetic effect. His paranoias and neurotic fears were very real. Take, for instance, the following conversation about "H. P. Lovecraft's Phobias" on Yahoo Answers!:

Question: I've heard that Lovecraft had various phobias, what were they?If you'd like to know more about that or other recondite matters, you could do worse than consult the following tome, by the indefatigable Leslie S. Klinger, annotator of Sherlock Holmes, Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, Bram Stoker's Dracula, Neil Gaiman's Sandman, Alan Moore's Watchmen and a host of others:

Best Answer:Gelatinous seafood and the smell of fish (severe).Unfamilar types of human faces that deviated from his ethnic norm (severe).Doctors and hospitals (mild).Large enclosed spaces (subway systems, large caves etc., mild).He also seems to have had a mild phobia about tall buildings and the possibility of being trapped under one after a collapse.Very cold weather (probably justifiable, since he tended to faint in it).- Source: David Haden

Leslie Klinger, ed. The New Annotated H. P. Lovecraft (2014)

Klinger, Leslie S., ed. The New Annotated H. P. Lovecraft. Introduction by Alan Moore. Liveright Publishing Corporation. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2014.

The main thing to emphasise is that this strange mixture of aesthetic recidivism, obsessive compulsion, and perverse white supremacism somehow combined into a body of work almost as influential on the twentieth century as Poe's was on the nineteenth.

If you think I'm exaggerating, just try googling "H. P. Lovecraft in popular culture" sometime.

Nor is his fan base entirely confined to readers of comics and pulp paperbacks with their caps on backwards (a proud group of human beings I'm happy to belong to: with the exception of the cap, that is). He recently joined the very select company of the Library of America, the only twentieth century horror writer as yet to do so (with the exception of the comparatively high culture Shirley Jackson):

H. P. Lovecraft. Tales, ed. Peter Straub (2005)

Lovecraft, H. P. Tales. Ed. Peter Straub. The Library of America, 155. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 2005.

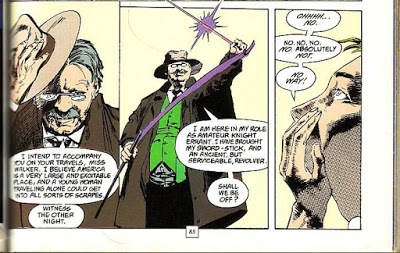

One of the most pleasing of the recent tributes to his influence is Alan Moore's remarkable series of comics set in a slightly alternative America of the 1930s:

Jasen Burrows: Providence 3 Cover (2015)

Neonomicon. Illustrated by Jacen Burrows. Rantoul, Illinois: Avatar Press, 2011.Providence: Act 1. Illustrated by Jacen Burrows. Issues #1-#4. Rantoul, Illinois: Avatar Press, 2017.Providence: Act 2. Illustrated by Jacen Burrows. Issues #5-#8. Rantoul, Illinois: Avatar Press, 2017.Providence: Act 3. Illustrated by Jacen Burrows. Issues #9-#12. Rantoul, Illinois: Avatar Press, 2017.

Jacen Burrows: Providence (2017)

Composed in his characteristic cross-genre mix of 'straight' comics and associated prose pieces and appendices, Moore's narrative described the odyssey of a hapless journalist over a thinly disguised version of Lovecraft's New England, resulting in the usual dire consequences for the entire human race.

Let's just say that these comics go some places that other fan fictions seldom do. They take a good look at Lovecraft's xenophobia and misognyny but pay full tribute to the power of his mythopoeic imagination, also. Not always to comforting effect, it should be said:

Jasen Burrows: Neonomicon 3 Cover (2010)

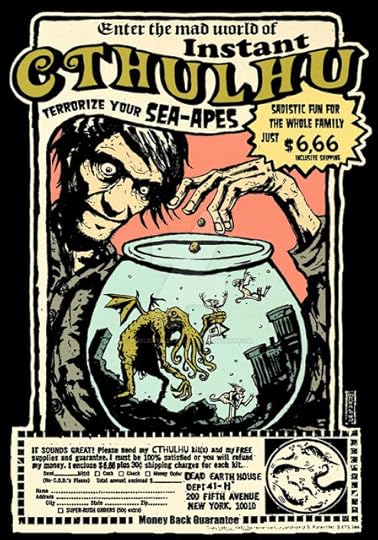

Beyond that, I have to say that I can't help but find amusing some of the Lovecraftian spoofs that seem to throng the web. This one, for instance, parodying those 'Sea-monkey' adverts so madly attractive to us as kids - when we were lucky enough to come across a stash of bona fide American comics, that is:

I guess that a lot of the 'shoggoth' references, and mentions of the "Great Old Ones' - not to mention 'Nyarlathotep, the Crawling Chaos', or 'Shub-Niggurath, Goat with a Thousand Young', or even great Cthulhu him - it? - self, don't really make much sense to the uninitiate, but this one, at least, has a pleasing brevity to it:

And these are all very sound rules if you ever be unfortunate enough to find yourself caught in the midst of a Lovecraftian scenario:

On and on and on they go: Lovecraftian ice-cream flavours, carnival exhibitions, you name it, it's there:

But back to the serious world of bibliomania and book-collecting. I still remember the disquieting experience of asking in a Takapuna bookshop if they had any Lovecraft books, only to be solemnly informed by the shop assistant that not only did they not, but that she doubted the very existence of such books. I recall the slightly roguish expression on her face when I brought out the dread syllables 'Love-craft,' and the distinct impression she gave that I was on some kind of subterranean quest for porno. Fat chance in the New Zealand of the early 1970s!

To add insult to injury, I'd seen those very books in that same bookshop only a month or two before. So her denials were, to say the least, somewhat disingenuous. When I tell you that what I'd seen was something like this, though, you may understand better her reluctance to engage with such "literature." God bless pulp cover illustrators!

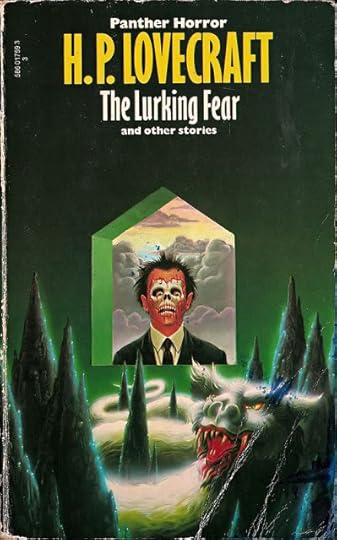

H. P. Lovecraft. The Lurking Fear and Other Stories (1973)

Never mind. In spite of the opposition of such petty minds, I eventually managed to assemble the six garish paperbacks which constituted the Master's collected horror fiction: Lovecraft, H. P. The Case of Charles Dexter Ward. 1951. London: Panther, 1970.

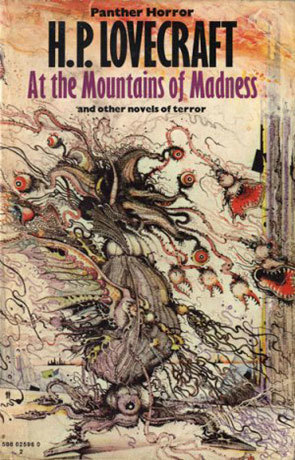

Lovecraft, H. P. At the Mountains of Madness and Other Novels of Terror. 1966. London: Panther, 1973.

Lovecraft, H. P. The Lurking Fear and Other Stories. 1964. London: Panther, 1973.

Lovecraft, H. P. The Haunter of the Dark and Other Tales. 1964. London: Panther, 1970.

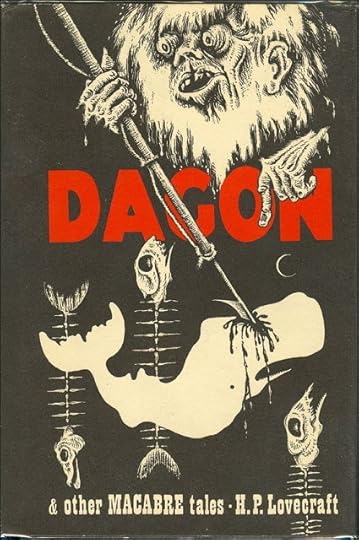

Lovecraft, H. P. Dagon and Other Macabre Tales. 1967. London: Panther, 1973.

Lovecraft, H. P. The Tomb and Other Tales. 1967. London: Panther, 1974.

H. P. Lovecraft. At the Mountains of Madness and Other Novels of Terror (1973)

If you looked carefully enough (I did), you'd observe that these six paperbacks actually constituted trimmed-down, British versions of the following three American hardbacks, all edited by by Lovecraft's most faithful disciple August Derleth, and published by Arkham House, the firm Derleth started to perpetuate the Master's work after his untimely death at the age of 47.

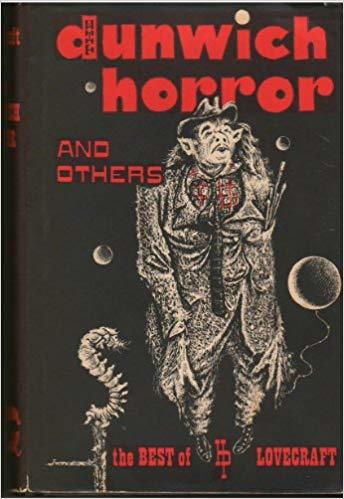

H. P. Lovecraft. The Dunwich Horror and Others (1963)

Lovecraft, H. P. The Dunwich Horror and Others: The Best Supernatural Stories. Ed. August Derleth. Sauk City, Wisconsin: Arkham House, 1963.

Lovecraft, H. P. At the Mountains of Madness and Other Novels. Ed. August Derleth. Sauk City, Wisconsin: Arkham House, 1964.

Lovecraft, H. P. Dagon and Other Macabre Tales. Ed. August Derleth. Sauk City, Wisconsin: Arkham House, 1965.

H. P. Lovecraft. Dagon and Other Macabre Tales (1965)

The first two collections of Lovecraft's work issued by Arkham House are now fabulously rare and valuable. Here they both are (I'm sorry to say, if you're wondering, that I don't own copies of either of them):

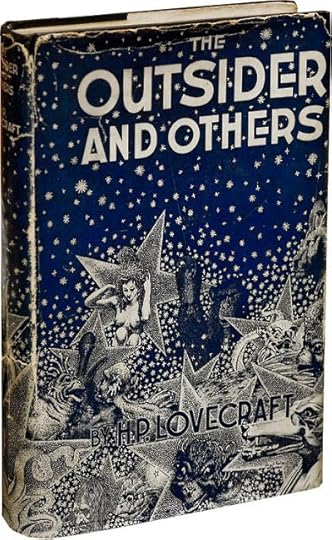

H. P. Lovecraft. The Outsider and Others (1939)

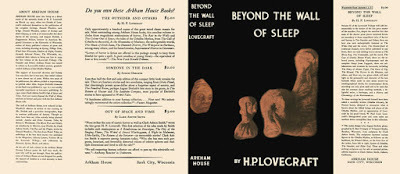

H. P. Lovecraft. Beyond the Wall of Sleep (1943)

Note the advertisement, above, for a book by Clark Ashton Smith, who, along with Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard, constituted the 'Big Three' of the classic pulp magazine Weird Tales, which flourished - largely because of their work and that of other members of the Lovecraft group - throughout the early to mid-1930s.

There are innumerable modern editions of Lovecraft - many of them 'corrected' or at least re-edited by horror story polymath S. T. Joshi:

Leslie Boba: S. T. Joshi (1958- )

Lovecraft, H. P. The Thing on the Doorstep and Other Weird Stories. Ed. S. T. Joshi. 2001. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2002.

Lovecraft, H. P. The Dreams in the Witch House and Other Weird Stories. Ed. S. T. Joshi. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2005.

There's also a weird, less easily classifiable penumbra of works 'edited by' Lovecraft (this was indeed the main way he made his meager living), or 'based on' his manuscripts, or 'inspired by' his themes (particularly those embodied in the Cthulhu mythos). I have a small collection of these, but the field is a vast one:

August Derleth (1909-1971)

Lovecraft, H. P., & August Derleth. The Shadow out of Time and Other Tales of Horror. London: Victor Gollancz, 1968.

Lovecraft, H. P., & August Derleth. The Lurker at the Threshold: A Novel of the Macabre. 1945. London: Victor Gollancz, 1968.

Lovecraft, H. P. & Others. Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos. Ed. August Derleth. 1975. London: Grafton, 1988.

Then there's the miscellaneous and secondary literature. There are collections of letters, of poetry (including his masterwork in this form, 'Fungi from Yuggoth'), of essays, of virtually anything you please. There are also numerous biographies and critical studies.

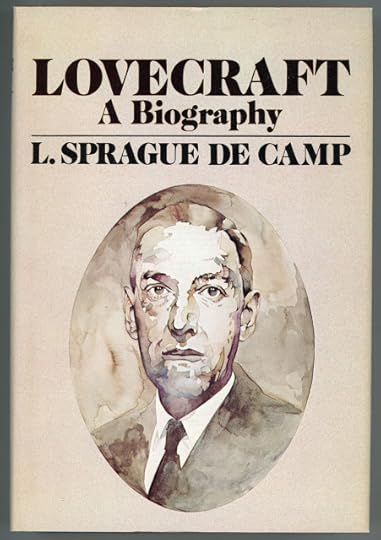

Of these I have only the first, somewhat dismissive one by L. Sprague de Camp, along with Colin Wilson's pioneering essay of 1962. Since then, however, the field has expanded vastly, due initially to the combined efforts of Derleth and Joshi, but now thanks largely to the incremental effect Academia tends to have on all such harmless pursuits:

L. Sprague de Camp: Lovecraft: A Biography (1975)

De Camp, L. Sprague. Lovecraft: A Biography. 1975. London: New English Library, 1976.

Wilson, Colin. The Strength to Dream: Literature and the Imagination. 1962. Abacus. London: Sphere Books Ltd., 1982.

Colin Wilson: The Strength to Dream (1962)

•

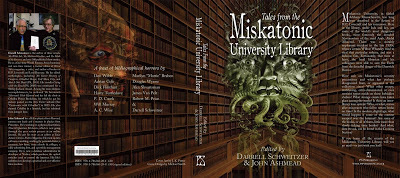

Tales from the Miskatonic University Library (2016)

Published on October 26, 2018 15:42

October 21, 2018

In Haunted Christchurch

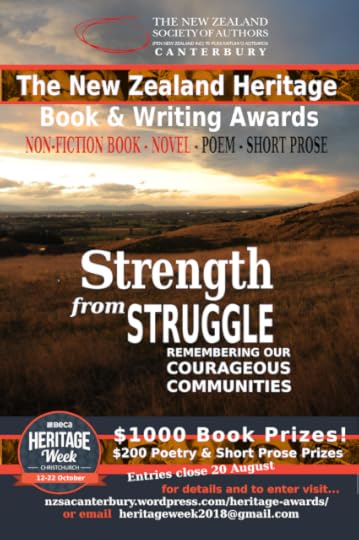

NZSA (Canterbury)

Invitation

We flew down for this event. Partly from curiosity, I must confess. I haven't really spent any time in Christchurch since the earthquake (though Bronwyn has), and I wanted to see what it was like.

Latimer Square by Night (Bronwyn Lloyd: 18/10/18)

Also, the hotel we were staying at, Rydges Latimer, was the scene of a haunting a few years ago, when Pakistani cricketer Haris Sohail had his bed shaken by an invisible something, so that constituted a bit of a temptation, too.

Church of St. Michael & All Angels (Bronwyn Lloyd: 18/10/18)

Nothing like that happened to us, but when we compared notes later, we realised that each of us had woken up during the night to find the room bathed with light from the clock radio beside the bed (this despite the fact that I'd covered it with a pillow before going to sleep). The pillow was certainly still there, in place, next morning - what can have led us to think that it had shifted, or been lifted off, by something or someone, in the middle of the night, then?

Keep out! (Bronwyn Lloyd: 18/10/18)

Perhaps these are mysteries we'll never understand. Valiant Christchurch is still in many ways a troubled city, though: witness many of the poems and stories read out at the awards ceremony.

Bell tower (Bronwyn Lloyd: 18/10/18)

Not only that, but it's also an intensely atmospheric one to wander around at night.

Tree (Bronwyn Lloyd: 18/10/18)

For the rest, we certainly had a great time while we were there, doing touristy things around the Square and the Avon, and then (next day) taking the bus out to Lyttelton and the Tannery.

Phone box (Bronwyn Lloyd: 18/10/18)

Bridge of Remembrance (Bronwyn Lloyd: 18/10/18)

It seemed strangely appropriate to have ended up in a restaurant called "Original Sin' - certainly their pasta was to die for!

Original Sin (Bronwyn Lloyd: 18/10/18)

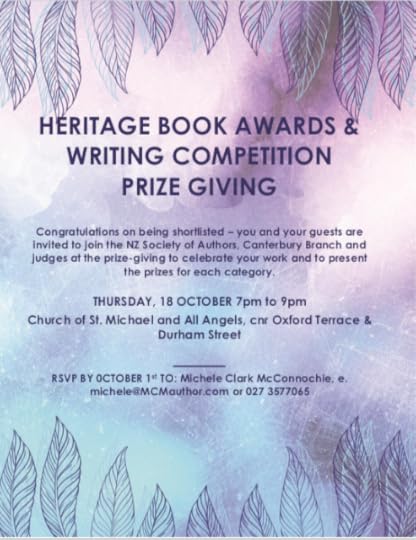

The event itself was run very smoothly and professionally by the Canterbury branch of the New Zealand Society of Authors. Every reader stuck to their allotted time - perhaps because the sheer splendour of the surroundings made us all determined to mind our p's and q's.

Reading from my novel (Bronwyn Lloyd: 18/10/18)

Here's the fiction shortlist:

NZSA Canterbury Heritage Book and Writing Awards 2018No fewer than 18 novels were entered for this part of the competition, apparently - along with 24 in the non-fictional book category, and many poems and essays. The judges certainly had their work cut out for them.

Judge: Fiona Farrell

Harvest by Christine Carrell (Nugget Stream Press 2017)The Life of De’Ath by Majella Cullinane (Steele Roberts Publishers, 2018)Finding by David Hill (Puffin 2018)This Mortal Boy by Fiona Kidman (Vintage Penguin Random House 2018)The Annotated Tree Worship: List of Topoi / Draft Research Portfolio by Jack Ross (Paper Table 2017)Gone to Pegasus by Tess Redgrave (Submarine Press 2018)

by the door (Bronwyn Lloyd: 18/10/18)

The winner was Dame Fiona Kidman's powerful novel about capital punishment in New Zealand, This Mortal Boy. The runner-up was David Hill's wonderful YA historical novel Finding. I was more than a little surprised, then, when Fiona Farrell announced that she'd insisted on creating a special category for my novel The Annotated Tree Worship, since (as she said) experimental fiction has a vital place in the literary firmament, too.

So here I am, looking proud as punch, with my 'Highly Commended' certificate. Thanks, Fiona:

Inside the church (Bronwyn Lloyd: 18/10/18)

Certificate

Published on October 21, 2018 12:14

October 13, 2018

The Protean Ursula K. Le Guin

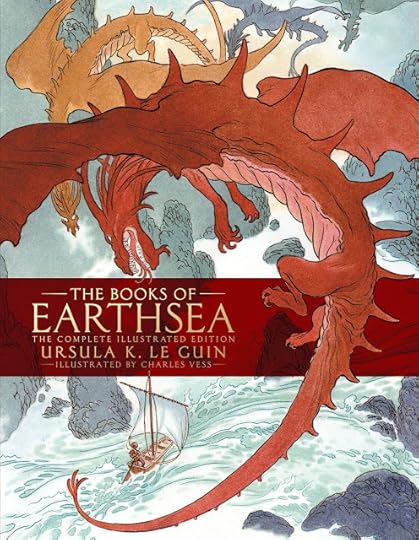

Charles Vess: The Books of Earthsea (2018)

i.m. Ursula Kroeber Le Guin

(21 October 1929 - 22 January 2018)

It's hard to think of a time when I hadn't read Ursula Le Guin's work. I suppose I can date it fairly precisely if I think about it. A Wizard of Earthsea was lent to my sister Anne by her standard four teacher, a thin, dark-haired, intense young woman whose name escapes me now. And since Anne was only a year ahead of me at school, that would make it 1971, when the book (first published in 1968) was only a few years old. That means I've been reading Le Guin for roughly 47 years - amazing, really, when you think about it.

Ursula Le Guin: A Wizard of Earthsea (1968)

Already a fan of such writers as Alan Garner, C. S. Lewis, and J. R. R. Tolkien, I could see that this was something quite different: different, but equally valid.

The Tombs of Atuan (1971), which we all read next, was a very different kettle of fish: more layered, subjective and intensely personal. I didn't like it as much as the more objective, epic voice of A Wizard of Earthsea, but (once again), even at that age, I could see it was just as valid.

Ursula K. Le Guin: The Lathe of Heaven (1971)

The Farthest Shore (1972), when it came out the next year, seemed to combine the best features of the two styles.

By then I was hopelessly hooked, and - soon after - started my long, slow immersion in her early science fiction: first The Lathe of Heaven (which my father had in a scruffy little paperback edition: still possibly my favourite among all of her books), then the far more difficult Left Hand of Darkness - which still terrifies as much as it enthuses me - and finally her wonderful 'ambiguous Utopia', The Dispossessed.

Ursula K. Le Guin et al.: The Left Hand of Darkness (1969)

After those early books came a long period of disappointment for me. Her early work seemed to me to constitute a touchstone of excellence in speculative fiction that only the greatest could hope to equal. But what was I to make of The Eye of the Heron or Buffalo Gals?

It seemed to me as if (to quote C. S. Lewis's witty denunciation of H. G. Wells) she "had sold her birthright for a pot of message." The wonderfully subtle and nuanced gender relations in books such as The Left Hand of Darkness or the original Earthsea Trilogy had been traded in for the strident excesses of militant feminism.

Ursula K. Le Guin et al.: The Eye of the Heron (1978)

The thing about addicts, though, is that it's very hard for them to break free from their addictions. By now the habit was formed, and I dutifully read book after book of hers, hoping against hope for a return to form. This even after she'd dared to politicise the pristine fantasy world of her own Earthsea with the bitter pill of Tehanu (1990).

Ursula K. Le Guin et al.: Tehanu (1990)

The years came and went, the books piled up: particularly the collections of short stories, a form which has always seemed particularly congenial to her. Eventually even I, the stupid mule, began to get it, began to read back with a bit more insight, began to see how my adolescent judgements of her work simply betokened a lack of political maturity.

Now even those novels and stories of her middle period seem to me clearly integrated into her work as a whole - it makes me blush to realise how blindly stuck in my ways I must have been to think otherwise: to fail (for instance) to see the merits of such a wonderful story as 'Buffalo Gals, Won't You Come Out Tonight.'

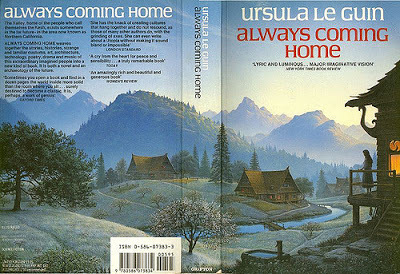

Ursula K. Le Guin: Always Coming Home (1985)

Interestingly enough, I didn't share the adverse reaction to Always Coming Home when it first came out - after, that is, I'd learned that it had to be read straight through: songs, folklore, ethnologies, etymologies and all, if one was to have any hope of understanding the narrative all those things frame. Do they exist for the story, or does the story exist for them? It's an interesting question, but one - by its very nature - which remains unanswerable.

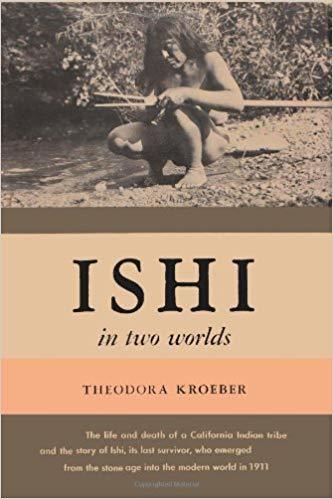

Ishi and Kroeber (1911)

Always Coming Home remains her most ambitious novel: the one which really betrays how much she was her father's daughter: Alfred L. Kroeber (1876-1960), one of the most influential ethnologists who ever lived, famous (or infamous, depending on how you read it) as one of the protagonists of the so-called Ishi saga, the story of which was eventually written as Ishi in Two Worlds (1961) by Theodora Kroeber, Ursula's mother - who never met Ishi himself - after her husband's death.

Theodora Kroeber: Ishi in Two Worlds (1961)

Always Coming Home, for those of you who haven't read it, is a strange combination of a fantasy novel set in the near (or far) future, and an ethnography of a people called the Kesh, inhabitants of what is now Northern California. It includes accounts of their religious rituals, castes and guilds, stories and poems, their diet, and virtually the whole of their life-style from birth to death. It’s a hugely ambitious text, involving the creation of a whole imaginary future people, but – of course – also aspires to be a readable story.

Alfred L. Kroeber: Handbook of the Indians of California (1925)

It’s always seemed obvious to me that it was, at least in part, inspired by her father's work: his Handbook of the Indians of California, or one of his many, many other works on Native American culture and folklore, such as Indian Myths of South Central California (1907) or the posthumously published Yurok Myths (1976).

Her mother's influence is just as strong, though: perhaps a unique case of a novelist daughter influenced by her linguist and anthropologist father and her biographer mother - who followed up her first, more scholarly book Ishi in Two Worlds with a more popular, lightly fictionalized version, Ishi: Last of His Tribe - in creating a work which can really only be described as ethno-speculative-fiction.

Ursula K. Le Guin: Searoad: Chronicles of Klatsand (1991)

Whether or not you agree with that reading, it's clear that all three of these writers, mother, father and daughter do have in common a deep kinship with the region they live in: the North-West Coast of the United States.

Perhaps her most potent expression of this feeling came in the book Searoad, an innovative book of linked short stories which combine to create the sense of a single place: Klatsand, a small town on the edge of the Pacific Ocean. Given this unity of conception, I've classed it as a novel in my bibliography of her work below, but actually it would fit just as well in the list of books of short stories.

That's quite characteristic of Le Guin, actually. She defies simple classification into genres. Her potted biography on Amazon.com reads as follows:

Ursula K. Le Guin (1929-2018) has published twenty-one novels, eleven volumes of short stories, four collections of essays, twelve books for children, six volumes of poetry, and four of translation.Given that they go on to say: "Her recent publications include the novel Lavinia [2008], Words Are My Matter, an essay collection [2016], and Finding My Elegy, New and Selected Poems [2012]," one can't help wondering how up-to-date these statistics are actually meant to be.

Myself, I count 13 'adult' novels alongside 9 for YA readers, which I would say adds up to 22. Given the doubts I've already signalled about Searoad, however, as well as the fact that The Word for World is Forest (1977) and Very Far Away from Anywhere Else (1976) are really more novella than novel-length, albeit published as stand-alone volumes, one could certainly argue for any figure around the 20s.

11 volumes of short stories does sound correct to me (including, as it should, her 2001 book Tales from Earthsea). The four collections of essays is hopelessly out-of-date, however. I count at least seven major volumes of these - although one could easily expand that to 8 if one included the British collection Dreams Must Explain Themselves (or, for that matter, 9, with the addition of the posthumous volume of Conversations on Writing with David Naimon).

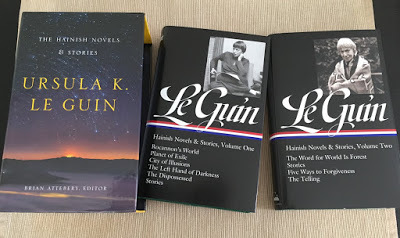

The 12 books for children have risen to 13, the 6 books of poetry to 12, but the 4 of translation still seems accurate. By my count, then, 72 books (ignoring - mind you - a number of the chapbooks listed on her Wikipedia bibliography page), plus at least 10 volumes of collected works, ranging from the various editions of the Earthsea series to the four-volume Library of America collection.

It's an impressive total. It's not so much how many there are as how many masterpieces there are among them, though. She really was one of a kind.

Ursula K. Le Guin: The Hainish Novels & Stories (2017)

•

Dana Gluckstein: Ursula K. Le Guin (1929-2018)

Select Bibliography

(1966-2018)

Novels:

Rocannon's World. 1966. A Star Book. London: W. H. Allen & Co., Ltd. 1980.

Planet of Exile / Thomas M. Disch. Mankind under the Leash. Ace Double. New York: Ace Books, Inc., 1966.

City of Illusions. 1967. Panther Science Fiction. St Albans, Herts: Panther Books, 1973.

The Left Hand of Darkness. 1969. Panther Science Fiction. St Albans, Herts: Panther Books, 1975.

The Lathe of Heaven. 1971. Panther Science Fiction. St Albans, Herts: Panther Books, 1974.

The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia. 1974. Panther Science Fiction. St Albans, Herts: Panther Books, 1975.

The Word for World is Forest. 1977. Panther Books. London: Granada Publishing, 1980.

Malafrena. 1979. Panther Books. London: Granada Publishing, 1981.

Threshold. [As ‘The Beginning Place’, 1980]. Panther Books. London: Granada Publishing, 1982.

Always Coming Home. Artist: Margaret Chodos. Composer: Todd Baron. Geomancer: George Hersh. 1985. London: Victor Gollancz, 1986.

Searoad: Chronicles of Klatsand. 1991. London: Victor Gollancz, 1992.

The Telling. 2000. London: Gollancz, 2003.

Lavinia. 2008. Mariner Books. Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2009.

Short Stories:

The Wind's Twelve Quarters. 1975. 2 Vols. Panther Books. London: Granada Publishing, 1978.

Orsinian Tales. 1976. Panther Books. London: Granada Publishing, 1978.

Virginia Kidd, ed. The Eye of the Heron and Other Stories. By Ursula K. Le Guin et al. [As ‘Millennial Women’, 1978]. Panther Books. London: Granada Publishing, 1980.

Le Guin, Ursula K. The Compass Rose: Short Stories. 1982. London: Victor Gollancz, 1983.

Buffalo Gals, and Other Animal Presences. 1987. A Plume book. New York: New American Library, 1988.

A Fisherman of the Inland Sea. 1994. London: Vista, 1997.

Four Ways to Forgiveness. 1995. HarperPrism. New York: HarperCollins, 1996.

Unlocking the Air and Other Stories. 1996. HarperPerennial. New York: HarperCollins, 2005.

The Birthday of the World and Other Stories. 2002. London: Gollancz, 2003.

Changing Planes: Stories. Illustrated by Eric Beddows. Orlando, Fl: Harcourt, Inc., 2003.

YA Fiction:

A Wizard of Earthsea. 1968. Drawings by Ruth Robbins. Puffin Books, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1976.

The Tombs of Atuan. 1971. Puffin Books, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1975.

The Farthest Shore. 1972. Puffin Books, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1975.

A Very Long Way from Anywhere Else. [As ‘Very Far Away from Anywhere Else’, 1976]. Peacock Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978.

Tehanu: The Last Book of Earthsea. London: Victor Gollancz, 1990.

Tales from Earthsea. 2001. London: Orion Children’s Books, 2002.

The Other Wind. 2001. London: Orion Children’s Books, 2002.

Gifts. Annals of the Western Shore, 1. 2004. Orlando, Fl: Harcourt, Inc., 2006.

Voices. Annals of the Western Shore, 2. 2006. Orion Children's Books. London: Orion Publishing Group Ltd., Inc., 2007.

Powers. Annals of the Western Shore, 3. 2007. Orion Children's Books. London: Orion Publishing Group Ltd., Inc., 2008.

Children's Books:

Leese Webster. Illustrated by James Brunsman (1979)

The Adventure of Cobbler's Rune. Illustrated by Alicia Austin (1982)

Solomon Leviathan's Nine Hundred and Thirty-First Trip Around the World. Illustrated by Alicia Austin (1983)

A Visit from Dr. Katz. Illustrated by Ann Barrow (1988)

Fire and Stone. Illustrated by Laura Marshall (1988)

Catwings. Illustrated by S. D. Schindler (1988)

Catwings Return. Illustrated by S. D. Schindler (1989)

Fish Soup. Illustrated by Patrick Wynne (1992)

A Ride on the Red Mare's Back. Illustrated by Julie Downing (1992)

Wonderful Alexander and the Catwings. Illustrated by S. D. Schindler (1994)

Jane On Her Own. Illustrated by S. D. Schindler (1999)