Jack Ross's Blog, page 24

March 2, 2018

Novelists in their 80s

Francois-Joseph Sandmann: Napoléon à Sainte-Hélène (1820)

My brother Ken, one of various novelists in our extended family, once explained to us his intention to stop writing at the age of 60. After that there was a great risk of letting one's senile lack of judgement falsify the true nature of your oeuvre, he claimed. He'll be hitting that mark next year, so it'll be interesting to see if he follows his own advice. My bet is he won't.

Nvertheless, I would have to admit that there's a certain amount to be said for this view. Joseph Conrad (1857-1924), for instance, might have been well advised to hang up his spurs before perpetrating, in his sixties, such disappointing works as The Arrow of Gold (1819) or The Rover (1923). James Joyce (1882-1941) died at the age of 60, having finished his work on Finnegans Wake (1939), so we were spared that late epic about the sea he was allegedly intending to write next. Thomas Hardy (1840-1928) stopped writing novels in his fifties and switched to poetry, claiming that he now preferred the conciseness attainable in verse as against the sheer heavy lifting required by novels. Herman Melville (1819-1891) stopped writing prose in his forties, though in that case there was the late flowering of Billy Budd, after nearly thirty years of verse writing.

Sixty might be a bit on the conservative side, but what of eighty? Life expectancies (in the developed world, at any rate) have vastly increased with the advent of modern medications against cholesterol, heart disease and a slew of other silent killers. Perhaps 80 is the new 60?

Over the summer I've been reading some novels - by some of my favourite authors - which nicely illustrate this dilemma. They are:

Umberto Eco: Numero Zero (2013 / 2015)

Tom Keneally: Napoleon's Last Island (2015)

Mario Vargas Llosa: The Discreet Hero (2013 / 2015)

(In the case of Eco and Vargas Llosa, the first date in brackets is the date of original publication, the second the date of publication of the English translation).

Umberto Eco was born in 1932, and died in 2016, at the age of 84. Tom Keneally was born in 1935, and is at present 82. Mario Vargas Llosa was born in 1936, and is now 81. Neither of the latter two show any signs of stopping writing: and writing novels, too. Both have published another one since the title listed above. So what are they like, these late works by an Italian polymath, an Australian jack-of-all-trades, and a Peruvian phenomenon? Surprisingly diverse, to be honest.

•

Umberto Eco, b. 5 January, 1932-d. 19 February, 2016

I have to admit to being a bit blind to the merits of The Name of the Rose when it first burst upon the world in the early 80s. It seemed laboured and over-constructed. I did enjoy the movie, though.

It wasn't until I read Foucault's Pendulum that Eco's true distinction started to dawn on me. It could not be said to be a particularly well-constructed book, either - and it certainly drove away many of The Name of the Rose fans who expected him to continue in the same vein, like a kind of Brother Cadfael for Intellectuals. But the idea of the book was, I thought, brilliantly clever (and prescient, considering how much it predated Dan Brown and his ilk). I began to see how pointless it was to judge Eco by the standards of other writers: he demanded his own style of reading, as cerebral as he was himself, but with a strong streak of emotional vulnerability hidden away inside somewhere.

The Island of the Day Before is probably my favourite of all of his fictions. Again, it was very clever - but the various intermeshing plots seemed to spin more smoothly than Foucault's Pendulum. He was clearly learning on the job. Baudolino and The Prague Cemetery were less pleasing. While full of rich material, they seemed more predictable and linear than their predecessors.

The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana was an exception to this tendency, however. It's hard not to admire the portrait he paints there of a disintegrating mind - the suspicion that some of it might be autobiographical added particular poignancy to the novel.

Numero Zero has the makings of a brilliant book. The idea of painting a counter-history of post-war Italy based on the conceit that Mussolini did not in fact die, but went on hiding in the Vatican for many decades more, is an excellent (though disconcerting) one, and the portrait Eco provides of the world of petty journalism and jobbing writers that constitutes mid-century Italy's New Grub Street is similarly interesting. It is, nevertheless, a terrible piece of writing.

Why? Because it's too short to hold up the weight of its central conceit - because the conversations sound like lecture fragments, and the characters like stick figures in a powerpoint presentation - because he resorts to the most desperate mystery story cliches to finish off this albatross of a narrative. Because, in short, he lacked the energy and time to complete it, and yet somehow managed to persuade himself that it still merited publication.

It's a sad coda to the life work of a unique and brilliant writer. Should we have been allowed to read it? Curiosity was probably always going to commit it to some kind of publication. I suppose the real problem is that it appeared during his lifetime rather than posthumously. A preface apologising for its brevity and lack of finish would have ensured a much better reception, though, I would have thought.

Umberto Eco: Numero Zero (2015)

Umberto Eco (1932-2016)

The Name of the Rose. 1980. Trans. William Weaver. 1983. London: Picador, 1984.

Reflections on The Name of the Rose. 1983. Trans. William Weaver. 1984. London: Secker & Warburg, 1985.

Foucault's Pendulum. 1988. Trans. William Weaver. London: Secker & Warburg, 1989.

The Island of the Day Before. 1994. Trans. William Weaver. 1995. Minerva. London: Mandarin Paperbacks, 1996.

Baudolino. 2000. Trans. William Weaver. 2002. London: Vintage Books, 2003.

The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana. 2004. Trans. Geoffrey Brock. 2005. London: Vintage Books, 2006.

The Prague Cemetery. 2010. Trans. Richard Dixon. Harvill Secker. London: Random House, 2011.

Numero Zero. 2015. Trans. Richard Dixon. Harvill Secker. London: Vintage, 2015.

•

Eva Rinaldi: Thomas Keneally, b. 7 October, 1935 (aged 82)

So, if we take Umberto Eco's last novel as a vote against publishing such late fictions, what of Thomas (now 'Tom') Keneally's next-to-latest tome, Napoleon's Last Island?

I have to admit that, after a somewhat shaky start, I came to love this book. It seemed to me to combine all of Keneally's virtues, and very few of his faults. This despite that fact that the tale of Betsy Balcombe and her relationship with the ex-Emperor is a familiar one. I remember seeing a television play based on the story when I was a teenager, and it's come up for me in a number of other contexts since.

I think the first book I read by Keneally was his wonderful American Civil War epic Confederates. His command of the vernacular and incidental detail seemed to me superior to anything I'd read before about that war, even by bona fide American authors. It was his talent for ventriloquism which first impressed me about him, then.

After that I read desultorily in his work: the books which had been made into films (Schindler's Ark, Gossip from the Forest), and also the ones about Antarctica (The Survivor, A Victim of the Aurora). In all these cases I was struck by how much better they were than they had to be. That sounds a bit paradoxical, but what I mean is that there's a kind of middle style and general competence which many novelists evolve and which drags them through their day-today labours. It sounds terrible, but they don't really pull out the stops unless they absolutely have to.

Keneally was not at all like that. Each new challenge seemed to fill him with gusto. He clearly relished the difficulty of interpreting unlikely characters, and entering strange and alien environments. Reluctant to repeat himself, he remained on the lookout for fresh woods and pastures new.

In the case of Napoleon's Last Island, this has led him to concoct an excellent pastiche of Jane Austen's prose-style and psychological penetration, set in the strange landscape of the tiny mid-Atlantic island of St. Helena. Betsy Balcombe has a good deal in common with Pride and Prejudice's Elizabeth Bennett, with the Emperor as a kind of super Darcy, and even a long-suffering older sister to provide her with a foil.

The dramatic nature of the story leads one to expect a kind of costume drama potboiler, but Keneally's interests seem altogether elsewhere: in the oddities of human psychology as shown under stress, and in the paradox of the man of destiny reduced to an atom in the sea of humanity, but still somehow retaining his uncanny charisma and fascination. Like Foucault's Pendulum, Napoleon's Last Island appears to have disappointed a good many admirers of Keneally's Australian epics: but it's an admirably subtle piece of work for all that.

Chalk that up as a vote for keeping up with your craft even as you approach your ninth decade, then. (The list of his works below is only a selection, I should emphasise: the books by him that have ended up in my collection. A full listing would occupy many more pages).

Tom Keneally: Napoleon's Last Island (2015)

Thomas Keneally (1935- )

The Fear. 1965. London: Quartet Books, 1973.

Bring Larks and Heroes. 1967. London: Quartet Books, 1973.

Three Cheers for the Paraclete. 1968. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971.

The Survivor. 1969. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970.

The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith. 1972. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1973.

Blood Red, Sister Rose. 1974. Glasgow: Fontana/Collins, 1976.

Gossip from the Forest. London: Collins, 1975.

Season in Purgatory. Sydney: Book Club Associates, 1976.

A Victim of the Aurora. London: Collins, 1977.

Passenger. London: Collins, 1979.

Confederates. 1979. Glasgow: Fontana/Collins, 1981.

The Cut-Rate Kingdom. 1980. Ringwood, Victoria: Penguin Books Australia, 1984.

Schindler’s Ark. 1982. London: Coronet Books, 1983.

Searching for Schindler. 2007. A Vintage Book. Sydney: Random House Australia Pty Ltd., 2008.

The Playmaker. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1987.

A River Town. Port Melbourne, Victoria: William Heinemann Australia, 1995.

Napoleon's Last Island. A Vintage Book. Sydney: Random House Australia Pty Ltd., 2015.

Crimes of the Father. 2016. A Vintage Book. Sydney: Random House Australia Pty Ltd., 2017.

•

Mario Vargas Llosa, b. 28 March, 1936 (aged 81)

So what of that wondrous, protean genius Mario Vargas Llosa? He's not the best known of the great writers of the Latin American "boom" of the sixties and seventies (it took him until 2010 to win the Nobel Prize his near-contemporary Gabriel García Márquez was awarded as far back as 1982), but he is - to my mind, at least - the best of them.

Year after year, decade after decade, he's produced a dazzling series of works, constantly reinventing himself and experimenting with new style: after the majestic, quasi-Faulknerian gravitas of those first three socio-historical novels The City and the Dogs, The Green House and Conversation in the Cathedral, he post-modernised himself into the prankster of Pantaleon and the Special Service and the autobiographical Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter.

How I pored over his works while working on my Doctoral thesis on European Images of South American in the late 1980s! The book I was writing about, The War of the End of the World seemed to combine the virtues of both his late and his early style: the trickster in bed with the sociologist at last.

It wasn't for a long long time that he attained similar heights, however. He stood (unsuccessfully) for President of Peru in the late 80s, and his work seemed to suffer somewhat from the increasingly public nature of his life. His politics, too, had gone far to the right to the point that he was hardly on speaking terms with many of his former literary comrades in arms.

None of the books he wrote during these years was unreadable or unchallenging in its way (even the quasi-soft porn of In Praise of the Stepmother and The Notebooks of Don Rigoberto), but it wasn't really until his dictator-novel (almost the classic Latin American subgenre) The Feast of the Goat appeared in 2001 that he really amazed the world again.

The Way to Paradise and The Dream of the Celt are both good ficto-biographies in their own right, but they hardly seemed up to the standard of his earlier work. The Discreet Hero is not among his masterworks, either, but it's a fascinating read for the fans (in particular).

Those of you who've read Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter will recall how the latter's scripts start to fold in on themselves, with characters appearing in the wrong contexts and contaminating the plotlines with unexpected interventions. So many of Vargas Llosa's own old characters - Lituma, Don Rigoberto, the 'Stepmother' herself - turn up in this novel that one has, at times, the odd feeling that the whole thing is set in Vargas-Llosa-land rather than any kind of recognisable Peru.

His obsession with the provincial Peru of the 1950s, its constant recurrence in its work, is supplanted here by an rather more 'contemporary' Lima and Piura. The characters all seem to live in the past, however: his past, Vargas Llosa's, rather more than their own.

The novel is neatly plotted and full of unexpected treats - though perhaps more for readers familiar with his work than any newcomers. The playfulness may seem a little forced at times, the virtuosity a bit tired, but there's no doubt that Vargas Llosa at his worst (and this book is a long way from his worst - The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta, say) is still superior to most other novelists at their best.

Would he, too, be wise to give up this strange compulsion to dream on paper and call the end-result art? I don't think so, no. The Feast of the Goat came after such a long dry spell that most critics had already written him off. I'm not expecting anything as good as that to come up again, but then, the essence of the unexpected is that you don't expect it. Who can say what the future holds for Mario Vargas Llosa? I hope not something as sad as Numero Zero, but it may well contain something as luminous and strange as Napoleon's Last Island.

Let's just say that as long as he's writing, I'll be reading (and buying). To hell with nay-sayers and agists! One can write a bad book at any age - and (I firmly believe) go on to redeem it with a good one. And always in the wings shimmers the alluring prospect of a Billy Budd, that late, redemptive masterpiece that comes out of left field - albeit often posthumously - to astonish the world ...

Mario Vargas Llosa: The Discreet Hero (2015)

Jorge Mario Pedro Vargas Llosa (1936- )

Vargas Llosa, Mario. The Cubs and Other Stories. 1965 & 1967. Trans. Gregory Kolovakos & Ronald Christ. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc., 1979.

The Time of the Hero. 1962. Trans. Lysander Kemp. 1966. Picador. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1986.

The Green House. 1965. Trans. Gregory Rabassa. 1968. Picador. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1986.

Conversation in the Cathedral. 1969. Trans. Gregory Rabassa. 1975. London: Faber, 1993.

Captain Pantoja and the Special Service. 1973. Trans. Gregory Kolovakos & Ronald Christ. 1978. London: Faber, 1987.

Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter. 1977. Trans. Helen R. Lane. 1982. Picador. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1984.

The War of the End of the World. 1981. Trans. Helen R. Lane. 1984. London: Faber, 1986.

The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta. 1984. Trans. Alfred MacAdam. 1986. London: Faber, 1987.

Who Killed Palomino Molero? 1986. Trans. Alfred MacAdam. 1987. London: Faber, 1989.

The Storyteller. 1987. Trans. Helen Lane. 1989. London: Faber, 1990.

In Praise of the Stepmother. 1988. Trans. Helen Lane. 1990. London: Faber, 1992.

Death in the Andes. 1993. Trans. Edith Grossman. 1996. London: Faber, 1997.

The Notebooks of Don Rigoberto. 1997. Trans. Edith Grossman. 1998. London: Faber, 1999.

The Feast of the Goat. 2001. Trans. Edith Grossman. 2002. London: Faber, 2003.

The Way to Paradise. 2003. Trans. Natasha Wimmer. London: Faber, 2003.

The Bad Girl: A Novel. 2006. Trans. Edith Grossman. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007.

The Dream of the Celt. 2010. Trans. Edith Grossman. London: Faber, 2012.

The Discreet Hero. 2013. Trans. Edith Grossman. London: Faber, 2015.

The Neighbourhood. 2016. Trans. Edith Grossman. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018.

Published on March 02, 2018 12:25

February 10, 2018

Tad Williams and the Rise of Epic Fantasy

Tad Williams: The Dragonbone Chair (1988)

I suppose that one advantage of the TV series Game of Thrones is that you no longer have to bother to try to explain to people what epic fantasy is.

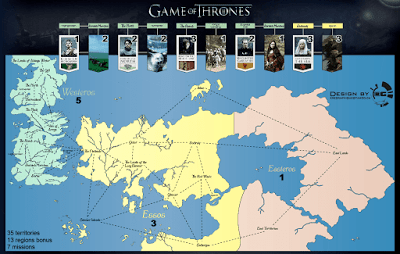

George R. R. Martin: Game of Thrones World Map

Before that, only J. R. R. Tolkien's Lord of the Rings trilogy could be said to have really broken through into popular culture, and - certainly before Peter Jackson's films - he was more the prototype and progenitor of the form than simply an example of it.

William Morris: The Roots of the Mountains (1890)

Of course, Tolkien himself would probably have pointed out how varied his sources actually were. William Morris is the principal one. Such prose romances as The House of the Wolfings (1889) and its sequel, The Roots of the Mountains (1890), gave Tolkien a good deal of his method and tone.

E. R. Eddison: The Worm Ouroboros (1926)

Then there was E. R. Eddison - The Worm Ouroboros (1926), above all. And, in a more relaxed and satirical vein, Lord Dunsany and James Branch Cabell.

Lord Dunsany: The King of Elfland's Daughter (1924)

There was a time in the late 80s and 90s when I read a great many such books (and found some unexpected fellow-fans, too: Prof. D. I. B. Smith of Auckland University's English Department, my erstwhile MA supervisor among them - my PhD supervisor Colin Manlove, too).

Colin Manlove: The Fantasy Literature of England (1999)

I never read much of Terry Pratchett or Stephen Donaldson, who were both loudly proclaimed - rather unfairly, in retrospect - as Tolkien's heirs in the 1970s (the former has enjoyed a bit of a revival of late with the very entertaining TV miniseries The Shannara Chronicles).

The Shannara Chronicles (2016)

So who did I read back then? Here are a few of their names:

Louise Cooper (The Time Master Trilogy, 1986-1987.)

Louise Cooper: The Initiate (1986)

Cecilia Dart-Thornton (The Bitterbynde Trilogy, 2001-2002)

Cecilia Dart-Thornton: The Ill-Made Mute (2001)

Raymond E. Feist (The Riftworld Saga)

Raymond E. Feist: Magician (1982)

Robert Holdstock (The Mythago Cycle, 4 vols: 1984-1998)

Robert Holdstock: Mythago Wood (1984)

Guy Gavriel Kay (The Fionavar Tapestry, 3 vols: 1986-1988. )

Guy Gavriel Kay: The Summer Tree (1986)

Patricia A. McKillip (The Riddle-Master Trilogy, 1976-1979)

Patricia A. McKillip: The Riddle-Master of Hed (1976)

George R. R. Martin (A Song of Ice and Fire, 5 vols: 1996-2011)

George R. R. Martin: A Game of Thrones (1996)

Graham Dunstan Martin (The Soul Master, Time-Slip & The Dream Wall, 1984, 1986 & 1987)

Graham Dunstan Martin: The Soul Master (1984)

Michael Scott Rohan (The Winter of the World Trilogy: 1986-1988)

Michael Scott Rohan: The Forge in the Forest (1987)

Tad Williams (The Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn Trilogy: 1988-1993)

Tad Williams: Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn (1988-93)

Some of the examples in the list below include all of the principal, Tolkien-inherited ingredients: division into a trilogy; the presence of elves, dragons, and/or otherworldly creatures; a threat from some source of 'darkness' - generally in the North; a lost heir or 'chosen one' who has to set all to rights, possibly with the help of some ring, sword, or other talisman.

So far so banal. But then there are the exceptions: the genuinely original takes on the fantasy genre. Take Robert Holdstock's Mythago Wood, for example. His basic notion of a wood that resists visitors is an excellent one, but combined with the discovery that (like the Tardis) this wood is bigger on the inside than the outside, and - in fact - has no effective limit in time or space, since it constitutes a kind of repository for the collective mythological memory of mankind, as far back as the last Ice Age, the working out of his story has a peculiar resonance and even symbolic truth to it.

Michael Scott Rohan takes the idea of the Ice Age more literally, and tries to recreate the vanished kingdoms of an era before the Mediterranean flooded, and when vast areas of land were laid bare by the glaciers.

Cecilia Dart-Thornton relies more on traditional ballads and folklore to shape her own narrative, while Patricia McKillip contributes a beautiful, Ursula Le Guin-like clarity to her storytelling. So, while some of the authors may be a bit perfunctory in their prose-style, it's hard to fault them for richness of invention.

Of course, any fan of the genre will immediately point out how outmoded the above list is. So many new series have appeared since the late 1990s, when I stopped even trying to keep on top of them, that I couldn't begin to discuss them even if I had the knowledge. Rest assured that the presses of the world have been busy adding to the total through all the intervening years.

So why concentrate on Tad Williams in particular, then? Not because he's so much better than the others - though he's probably the most long-winded among them (the cover of The Dragonbone Chair describes it as "the fantasy equivalent of War and Peace", and I think it's as much its length as its narrative ambition the reviewer must have had in mind).

I guess I've chosen to feature him:because (pragmatically) he's one of the few fantasy writers I've actually made an effort to keep up with since I first starting reading him in the early 90s.because (theoretically) I believe him to be the author who's tried hardest and most consistently to experiment with different levels and concepts of reality: from the celestial cyberpunk of the "Bobby Dollar" books to the copyrighted virtual reality domains of the "Otherworld" tetralogy.The fact that, after all that, he's come back round to his starting-place, and is beginning yet another trilogy set in his Tolkien-esque kingdom of 'Osten Ard' also says something telling about the epic fantasy genre, however. Its fans are loyal and supportive - but they also tend to be resistant to change.

Unlike SF fans, who've got used to having all their expectations upset within the first few lines of each new story, Fantasy afficionados like to have horses, staffs, goblins, and elves - or some reasonable variant on same - crowd in to greet them pretty early on, regardless of how each author has chosen to account for their presence (creatures of a remote, post-nuclear-apocalypse future in Terry Pratchett; remnants of the ancient Germanic world in J. R. R. Tolkien).

Anyway, here's a reasonably comprehensive list of his thirty years of publications to date. By Tolkien's standards (at least), his protagonists do have a tendency to whine and demand instant attention to their peevish demands at inopportune moments (whether or not this represents a divergent Old World / New World set of cultural expectations I leave others to ponder). For the most part, though, he does have the ability to immerse his readers fully in a strangely believeable set of very particular fantasy worlds, and I suppose that's all one can really expect of a writer in this rather inflexible genre.

For myself, I'm a little sorry that he hasn't persevered with his virtual reality world Otherland, or even his Edwardian themed fairyland in The War of the Flowers, but with such a rate of production, it's fair to say that there are probably plenty of such departures from type to be expected from him yet!

The Shadowmarch series was a bit of a disappointment, it must be said: adding little to his earlier work on Osten Ard. The fact that he's now resumed that series - with what success it's a little early to say, though one has to salute his determination to make his evil adversaries as full of complex motivations as his "goodies". There's clearly life in the old genre yet, though of course I fully expect to be deluged by a set of suggestions for new such works and authors who have emerged over the past twenty years or so, whom I really must read in order to claim any currency at all. Bring it on!

•

Tad Williams (2007)

Robert Paul Williams (1957- )

Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn:The Dragonbone Chair. 1988. Legend Books. London: Arrow Books Limited, 1990.Stone of Farewell. 1990. Legend Books. London: Arrow Books Limited, 1991.To Green Angel Tower. Legend Books. London: Random House Group, 1993.

Tailchaser's Song. 1985. Legend Books. London: Random Century Group, 1991.

[with Nina Kiriki Hoffman]: Child of an Ancient City. Legend Books. London: Century, 1992.

Caliban's Hour (1994)

Otherland:City of Golden Shadow. Legend Books. London: Random House UK Limited, 1996.River of Blue Fire. An Orbit Book. London: Little, Brown & Company (UK), 1998.Mountain of Black Glass. 1999. An Orbit Book. London: Little, Brown & Company (UK), 2000.Sea of Silver Light. 2001. An Orbit Book. London: Time Warner Books UK, 2002.

The War of the Flowers. An Orbit Book. London: Time Warner Books UK, 2003.

Shadowmarch:Shadowmarch. An Orbit Book. London: Time Warner Book Group UK, 2004.Shadowplay. Orbit Book. London: Little, Brown Book Group, 2007.Shadowrise. DAW Book Collectors No. 1500. New York: DAW Books, Inc., 2010.Shadowheart. An Orbit Book. London: Little, Brown Book Group, 2010.

Bobby Dollar:The Dirty Streets of Heaven. London: Hodder & Stoughton, Ltd., 2012.Happy Hour in Hell. London: Hodder & Stoughton, Ltd., 2013.Sleeping Late on Judgement Day. London: Hodder & Stoughton, Ltd., 2014.

Rite: Short Work. 2006. Burton, MI: Far Territories, 2008.

A Stark and Wormy Knight: Tales of Fantasy, Science Fiction and Suspense. Ed. Deborah Beale. Burton, MI: Subterranean Press, 2012.

The Very Best of Tad Williams (2014)

The Last King of Osten Ard:The Heart of What Was Lost: A Novel of Osten Ard. London: Hodder & Stoughton, Ltd., 2017.The Witchwood Crown. London: Hodder & Stoughton, Ltd., 2017.

Published on February 10, 2018 13:45

January 4, 2018

John Clare / Charles Baudelaire

William Hilton: John Clare (1820)

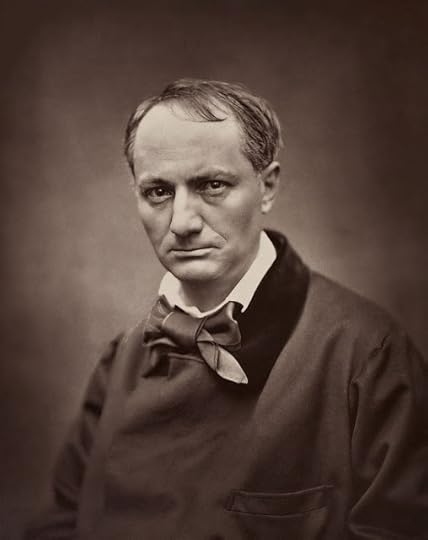

It's not really that I'm trying to be particularly original or provocative in comparing these two poets (perish the thought). They belong to completely different phases of the Romantic era, for a start: John Clare, the peasant poet, born in poverty in 1793 - a contemporary of Keats and Byron; Charles Baudelaire, the original poète maudit, born in the stifling heart of the bourgeoisie in 1821, and dead of alcoholism and self-abuse at the age of 46.

Étienne Carjat: Charles Baudelaire (1863)

Clare was (and remains) the patron saint of pastoral poets everywhere: a soul so pure he seemed to have come from another sphere, the pre-enclosure, peasant world of organic village life, free of the affectations of civilisation.

Baudelaire, by contrast, is the poet of drugs, sex, industrialism, city life, and the principal inspiration for the figure of the flâneur, the idle (but preternaturally observant) dandy - what the Russian critics called 'the superfluous man.' He was impecunious, self-destructive, vindictive, and relentlessly critical: of himself more than anything.

And yet, and yet. They didn't do anything quite as convenient as die in the same year, but they weren't far from it. John Clare died at 70 in 1864, Baudelaire three years later, in 1867. But then Clare spent the last 25 years of his life locked up in an asylum (from which he briefly escaped in 1841). Baudelaire, by contrast, suffered a massive stroke in 1866 and spent the last two years of his life in a succession of hospital wards.

In other words, neither of them could last in the world much beyond their mid-forties. The difference is, of course, that Clare experienced an extraordinary burst of creativity in his madhouse years - some poems written under his own name, others under that of Lord Byron, whom (some of the time) he believed himself to be.

So far so unconvincing. I agree that I haven't made a strong case, as yet, for considering them together. It's just that the other day I was reading The Wood is Sweet, a little selection of John Clare's poems made for children, and ran across one of his most famous poems, 'The Skylark':

Thomas Bewick: The Skylark (1797)

The Skylark (1835)

The rolls and harrows lie at rest beside

The battered road; and spreading far and wide

Above the russet clods, the corn is seen

Sprouting its spiry points of tender green,

Where squats the hare, to terrors wide awake,

Like some brown clod the harrows failed to break.

Opening their golden caskets to the sun,

The buttercups make schoolboys eager run,

To see who shall be first to pluck the prize —

Up from their hurry, see, the skylark flies,

And o'er her half-formed nest, with happy wings

Winnows the air, till in the cloud she sings,

Then hangs a dust-spot in the sunny skies,

And drops, and drops, till in her nest she lies,

Which they unheeded passed — not dreaming then

That birds which flew so high would drop agen

To nests upon the ground, which anything

May come at to destroy. Had they the wing

Like such a bird, themselves would be too proud,

And build on nothing but a passing cloud!

As free from danger as the heavens are free

From pain and toil, there would they build and be,

And sail about the world to scenes unheard

Of and unseen — Oh, were they but a bird!

So think they, while they listen to its song,

And smile and fancy and so pass along;

While its low nest, moist with the dews of morn,

Lies safely, with the leveret, in the corn.

This is a fairly typical Clare poem. He tends to write in standard metres - in this case heroic couplets, at other times ballad measure. His rhythms and versification tend to the traditional and unadventurous also: no sudden breaks in the iambic line, no startling rhymes (unlike his hero, Lord Byron).

So why do we love him so much? It's the detail of the lines, the sudden flashes of careful insight and genuine knowledge that one glimpses from time to time in his choice of phrases or adjectives that gives his verse its peculiar distinction.

On the one hand, it sounds a bit like a setpiece description by another of his models, James Thomson's The Seasons (1730), but the moment one goes below the surface, strange moments of vision start to appear:

Where squats the hare, to terrors wide awake,Clare, the 'whopstraw man,' a labourer whose job it was to harrow the harvested corn, is yet intensely aware of that 'squatting' hare - nor is it the beauty of the creature he chooses to emphasise, but its terror.

Like some brown clod the harrows failed to break.

The schoolboys running to catch buttercups seem pretty conventional figures, too, until we realise that Clare is using them to construct the intense metaphor which governs the last half of his poem:

Had they the wingThey imagine themselves like the skylark, but see it solely in terms of the clouds its flight encompasses. They cannot imagine the truth that it, too, is ruled by fear and the constant threat of destruction of what it holds dearest: its nest.

Like such a bird, themselves would be too proud,

And build on nothing but a passing cloud!

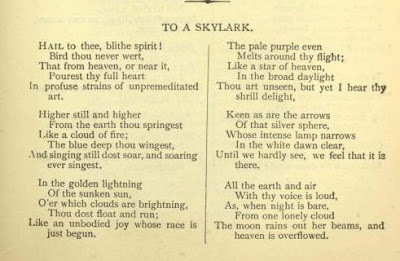

So think they, while they listen to its song,Well, clearly the obvious comparison here is with Shelley's "Ode to a Skylark", whose first five or so lines virtually everyone who's ever read a poem in English can quote by heart:

And smile and fancy and so pass along;

While its low nest, moist with the dews of morn,

Lies safely, with the leveret, in the corn.

P. B. Shelley: To a Skylark (1820)

The "schoolboy" comparison seems fairly apt, also. Shelley was 29 when he died, 27 when he published 'Ode to a Skylark.' Clare, in his mid-forties and at the heart of his powers, must have felt that he knew a good many things about birds which the younger poet had never had the chance - or possibly the desire - to learn. Even his strongest defenders would have to admit to a certain tendency towards abstraction in Shelley's verse. Clare's may be far less accomplished technically, but the precise and concrete was - in the end - all that interested him.

Let's take another tack on this poem of his, then. Here's Baudelaire's "The Albatross": :

Catherine Réault-Crosnier: L'Albatros

L'Albatros (1861)

Souvent, pour s'amuser, les hommes d'équipage

Prennent des albatros, vastes oiseaux des mers,

Qui suivent, indolents compagnons de voyage,

Le navire glissant sur les gouffres amers.

À peine les ont-ils déposés sur les planches,

Que ces rois de l'azur, maladroits et honteux,

Laissent piteusement leurs grandes ailes blanches

Comme des avirons traîner à côté d'eux.

Ce voyageur ailé, comme il est gauche et veule!

Lui, naguère si beau, qu'il est comique et laid!

L'un agace son bec avec un brûle-gueule,

L'autre mime, en boitant, l'infirme qui volait!

Le Poète est semblable au prince des nuées

Qui hante la tempête et se rit de l'archer;

Exilé sur le sol au milieu des huées,

Ses ailes de géant l'empêchent de marcher.

If you click on this link, you can find a selection of English verse translations of this immortal poem by the likes of Roy Campbell, George Dillon, and various others. Rather than add to them, I thought it might be best to provide a simple prose crib. There's a reason why many regard Baudelaire as the greatest European poet since Dante, and it isn't because he dyed his hair green and contracted syphilis: it's the sheer beauty and ease of his writing. Many of the translations on the site are very skillful, but they're still not Baudelaire.

The Albatross (1861)

Often, to amuse themselves, the crewmen

catch albatrosses, vast sea birds

who follow, indolent travelling companions,

the ship as it glides across the bitter gulfs.

Hardly have they dumped them on the deck,

than these kings of the blue, clumsy and ashamed,

let their great white wings trail pitifully

beside them like oars.

This winged traveller, how weak and foolish he is!

He, lately so beautiful, how comic and ugly!

One teases his beak with the stub of a pipe,

another mimes, limping, this invalid who once flew!

The Poet resembles this prince of the clouds

who haunts the storm and laughs at archers;

exiled on earth in the midst of catcries,

His giants' wings impede him from walking.

Just as one can hear, faintly, at the back of Clare's poem, an echo of Percy Shelley's, similarly, here, one senses the presence of Coleridge's "Rime of the Ancient Mariner." Baudelaire was pretty well-read in English literature, a pioneering translator of Poe and De Quincey (among others), and he could hardly have been ignorant of the most famous albatross in poetic history:

'God save thee, ancient Mariner,

from the fiends that plague thee thus! —

Why look'st thou so?' - With my crossbow

I shot the albatross.

Gustave Doré: Illustrations to the Ancient Mariner (1876)

That comment about how Baudelaire's ideal poet resembles the bird "qui hante la tempête et se rit de l'archer" [who haunts the tempest and laughs at the archer] is surely a reference to the crossbow-wielding mariner himself. But where exactly is Clare in this equation?

I guess it's in the reversal of expectations which dominates each poem. In Clare's case, the marauding schoolboys imagine that the skylark must nest in the clouds, since that's what they would do. Actually, though, it hides its nest as low down as it can, below eye level, in the corn with the rabbit and the other creeping creatures.

In Baudelaire's, the albatross is mocked because of its inability to master such simple, everyday arts as walking without stumbling across a deck. In fact it is because of its other great gifts, its giants' wings, that it cannot fit easily into a crowd, but the desire to simplify, to drag everything down to the level of the lowest common denominator is what leaves it so cruelly exposed.

Baudelaire's albatross was born to fly, and lacks the gifts for anything else. Clare's skylark is similarly gifted, but uses its flight to distract its enemies from what it most longs to protect. Both poets write out of an aching sense of loss and unbelonging. In Baudelaire's case this is expressed in loud outrage, in Clare's by the desire to hide and to escape.

If you want to understand John Clare, the first thing is to stop thinking of him as some simple, instinctive personality, lacking the art of his more self-conscious and educated contemporaries. His academy was every bit as rigorous as theirs, and his poetry - vast and uneven a bulk as there is of it - repays the same pains.

Similarly, reading Baudelaire for the cheap thrills of his iconoclasm and diablerie is mostly a waste of time. Those things are there, but it's the penetrating intensity of his intelligence and insight that gives his work its enduring power.

In both cases, paradoxically, it's sometimes best to approach these poets through their own prose. John Clare's "Journey out of Essex" - his heartbreaking account of his 1841 escape from the asylum to find his lost love, Mary Joyce (already dead for three years) - is fascinating enough. But his autobiographical and other prose notes on his life and the countryside he grew up in also have an indescribable charm of their own.

Baudelaire's prose is more multifaceted and complex, but his analyses of the paintings in successive salons show the concentrated critical intelligence which enabled him to revolutionise French - and, eventually, world - poetry. He was never really the idle druggie of legend, but rather a disciplined mind modelled on, but eventually surpassing, his hero, Edgar Allan Poe.

Both are poets not so much to read, as to reread. As soon as you've reached the end of each poem or journal entry, it's time to turn back to the beginning and start again. Only then does the peculiar light of their insight begin to communicate. These are not bodies of work one could ever exhaust.

I conclude, as usual, with a brief list of the books by each I've managed to accumulate in the last thirty-odd years of reading both:

Iain Sinclair: Edge of the Orison (2005)

John Clare

(1793-1864)

Geoffrey Grigson, ed. Poems of John Clare’s Madness. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1949.

J. W. & Anne Tibble, ed. John Clare: The Prose. 1951. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1970.

Eric Robinson & Geoffrey Summerfield, ed. John Clare: The Shepherd’s Calendar. Wood Engravings by David Gentleman. 1964. London: Oxford University Press, 1974.

Eric Robinson & Geoffrey Summerfield, ed. John Clare: The Later Poems. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1964.

J. W. & Anne Tibble, ed. John Clare: Selected Poems. Ed. J. W. & Anne Tibble. Everyman’s Library, 563. London: J. M. Dent, 1965.

David Powell, ed. John Clare: The Wood is Sweet. Introduction by Edmund Blunden. Illustrated by John O'Connor. Poems for Young Readers. London: The Bodley Head Ltd., 1966.

Eric Robinson & Richard Fitter, ed. John Clare’s Birds. Illustrated by Robert Gillmor. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982.

Eric Robinson & David Powell, ed. John Clare: The Oxford Authors. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984.

Eric Robinson, ed. John Clare: The Parish, A Satire. Notes by David Powell. 1985. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1986.

Geoffrey Summerfield, ed. John Clare: Selected Poems. 1990. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin, 2000.

Robinson, Eric, & David Powell, ed. John Clare By Himself. Wood Engravings by Jon Lawrence. 1996. Fyfield Books. Manchester: Carcanet Press, 2002.

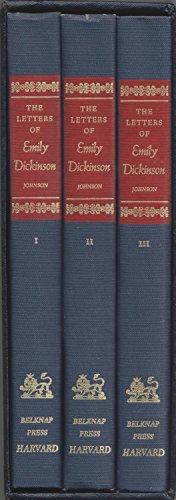

J. W. & Anne Tibble, ed. John Clare: The Letters. 1951. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1970.

Mark Storey, ed. John Clare: Selected Letters. 1985. Oxford Letters & Memoirs. 1988. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

J. W. & Anne Tibble. John Clare: A Life. 1932. Rev. Anne Tibble. London: Michael Joseph Ltd., 1972.

Edward Storey. A Right to Song: The Life of John Clare. London: Methuen, 1982.

•

Édouard Manet: Jeanne Duval (1862)

Charles Pierre Baudelaire

(1821-1867)

Y.-G. Le Dantec, ed. Baudelaire: Oeuvres. Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, 1. 1934. Paris: Gallimard, 1944.

P. Schneider, ed. Baudelaire: L’Oeuvre. Les Portiques, 16. Paris: Le Club Français du Livre, 1955.

Antoine Adam, ed. Baudelaire: Les fleurs du mal: Les Épaves / Bribes / Poèmes divers / Amoenitates Beligicae. Édition illustrée. 1961. Classiques Garnier. Paris: Éditions Garnier Frères, 1970.

Yves Florenne, ed. Baudelaire: Les fleurs du mal: Édition établie selon un ordre nouveau. 1857. Préface de Marie-Jeanne Durry. Le Livre de Poche, 677. Paris: Librairie Générale Française, 1972.

Melvin Zimmerman, ed. Baudelaire: Petits Poèmes en Prose. 1869. French Classics. Ed. Eugène Vinaver. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1968.

George Dillon & Edna St. Vincent Millay, trans. Baudelaire. Les Fleurs du Mal: Translated and Presented on Pages Facing the Original French Text as Flowers of Evil. With an Introduction and an Unusual Bibliographical Note by Miss Millay. 1936. New York: Washington Square Press, Inc., 1962.

Louise Varèse, trans. Baudelaire: Paris Spleen. 1869. A New Directions PaperBook, NDP294. 1947. New York: New Directions Publishing Corporation, 1970.

Francis Scarfe, trans. Baudelaire: Selected Poems. The Penguin Poets. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1961.

Clark, Carol, & Robert Sykes, ed. Baudelaire in English. Penguin Classics: Poets in Translation. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1997.

P. E. Charvet, trans. Baudelaire: Selected Writings on Art and Artists. 1972. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981.

Edgar Allan Poe. Histoires Extraordinaires. Trans. Charles Baudelaire. Préface de Julio Cortázár. Collection Folio, 310. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1973.

Enid Starkie. Baudelaire. 1957. Pelican Biographies. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971.

Claude Pichois. Baudelaire. Additional Research by Jean Ziegler. 1987. Trans. Graham Robb. 1989. London: Vintage, 1991.

Charles Baudelaire: "Spleen: I am like the king of a rainy country ..." (1861)

John Clare: "Lines: I Am" (1848)

Published on January 04, 2018 14:20

December 22, 2017

The English Opium-Eater

Thomas De Quincey: Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1822)

Cors de chasse

Notre histoire est noble et tragique

Comme le masque d'un tyran

Nul drame hasardeux ou magique

Aucun détail indifférent

Ne rend notre amour pathétique

Et Thomas de Quincey buvant

L'opium poison doux et chaste

A sa pauvre Anne allait rêvant

Passons passons puisque tout passe

Je me retournerai souvent

Les souvenirs sont cors de chasse

Dont meurt le bruit parmi le vent

- Guillaume Apollinaire, Alcools (1913)

Jean Cocteau: Guillaume Apollinaire (1917)

Hunting Horns

Our story's noble and tragic

like the deathmask of a tyrant

no drama sparked by chance or magic

no insignificant detail

can render love like this unreal

and Thomas de Quincey drinking

the sweet chaste poison of opium

dreamt all along of his poor Anne

pass on pass on everything passes

I'll return here often

memories are hunting horns

whose sound dies softly in the wind

- trans. JR

Jean Cocteau: Opium (1930)

It's easy to forget that Thomas De Quincey is as significant a figure for French readers as he is for English ones. In fact, like Edgar Allan Poe, one could argue that they admire him more than we do: his peculiar distinction perhaps appeals more to a European audience than an Anglo-Saxon one.

Be that as it may, De Quincey (rightly or wrongly) is famous for one thing, and one thing only: his Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, originally published anonymously in the London Magazine in September-October 1821, and then in book form (still anonymously) the following year.

The Opium-Eater (1822)

I still remember the excitement in my house when my eldest brother finally bought a copy of the Confessions. It was a tiny World's Classics edition, and my other brother and myself were queued up to read it as soon as he finished it. It didn't take long. He said that the whole thing was totally boring, and mainly consisted of a long slanging match in which he denounced Coleridge as a mere dabbler and amateur in opium-consumption beside himself, with long computations of their respective consumption per day. There wasn't a single opium dream to be found in it, he concluded.

I had to acknowledge that he had a point when I did finally get my hands on the book. There was an awful lot of build-up before one got anywhere near the subject of opium, some of it autobiographical background, but most of it arguments with various critics, conducted with maximum pedantry and minimal good humour.

The whole thing, I concluded, was a swizz. Until I got my hands on a Penguin reprint of the first, 1822 edition, that is. Then I began to see what people had been talking about. Then, too, the strange and wistful figure of the young prostitute Ann (Apollinaire, possibly for personal reasons, misremembers it as Anne with an 'e') began to come into sharper focus.

"Ann of Oxford Street"

[idealised portrait]

De Quincey was always in debt. He wrote as rapidly as he could, for a variety of publications, essays and squibs which could be sold for just enough to stave off his creditors and keep his family alive for another day. (And then there was his opium habit to support, too).

The original two-part serial version of the Confessions had many deficiencies and lacunae (or so it seemed to him), few of which he was able to correct when it appeared in book form. He cherished the idea of a 'corrected' edition, where he would be able finally to do more than sketch the effect of opium on him, and on his half-erotic, half-idealised reveries.

That time finally came in the 1850s, when he was labouring away on a revised version of his essays and other works to date. It finally appeared, as Selections Grave and Gay from Writings Published and Unpublished by Thomas De Quincey (14 vols - Edinburgh: James Hogg, 1853-60).

This collection was initially prompted by an American edition - De Quincey's Writings (22 vols - Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1851-59) - which reprinted the original periodical versions of each of the pieces. De Quincey, after initially contracting to supply them with revised copy, failed (not atypically) to reply to any subsequent letters, thus forcing the enterprising Yankees to rely on the resources to hand.

Unfortunately De Quincey in his sixties, beaten down by fate, poverty, and protracted drug-addiction was not really the man he'd been in his vigorous thirties. The additions he made to The English Opium-Eater - some of them quite valuable and interesting in their own right - had the unfortunate cumulative effect of completely masking the dramatic impact of the first version.

In many ways the American edition remains the better of the two, therefore.

This leaves readers with the insoluble paradox of which version to read. The 1821-22 text is definitely superior in terms of design, conciseness, and poetic effect. It's very seldom reprinted, however.

The 1856 text begins very badly, with De Quincey at his most argumentative and twaddly, but then goes on to sharpen and expand on many parts of the fascinating tale of his sojourn in London as a teenage runaway from school, the period in which he met the beautiful young fifteen-year-old prostitute Ann, whom he loved in the most childlike and innocent way possible - one reason why his book appealed so much to the Victorians, with their child fixation (and to love-sick poets, such as Apollinaire - and myself - ever since).

Ann! For many years after he reached manhood, De Quincey paced the streets trying to find her, but no trace of her was ever discovered. The romantic dream of her innocent beauty in the midst of the degradation of turn-of-the-century London remains the most powerful image in his book, transmuted though it is into various strange forms in the dreams recorded in the fascinating section "The Pleasures of Opium."

Rag-picker's daughter (1849)

The standard edition of De Quincey's Collected Writings, edited by David Masson in 1889-90, is forced to rely on the author's corrected texts for all the pieces originally included in Selections Grave and Gay (despite the undoubted superiority of some of the earlier texts).

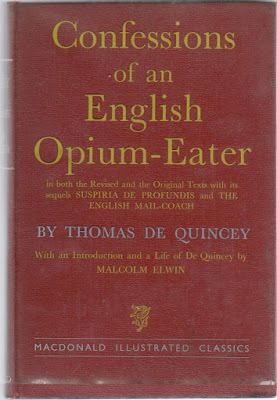

David Masson, ed. Collected Writings of Thomas De Quincey (1889-90)

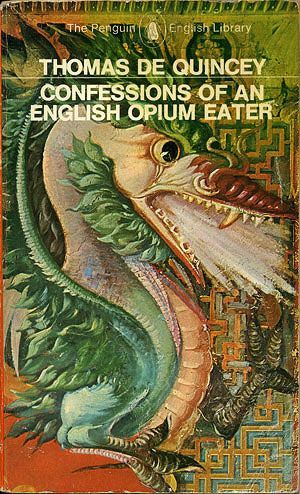

For the most part this doesn't matter too much. For the Confessions, though, it does. Probably the best solution to date is that found by Malcolm Elwin in his 1956 MacDonald Illustrated Classics centennial edition, entitled Confessions of an English Opium-Eater in Both the Revised and the Original Texts, with its Sequels "Suspiria de Profundis" and "The English Mail-Coach". If you're fortunate enough to chance upon a copy of this, you're home and hosed (so to speak).

Malcolm Elwin, ed. Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1956)

Failing that, the Penguin Classics edition of the Confessions is probably the best. You do need both texts: that's the conundrum. But be sure to read the first version first. Otherwise you risk being turned off altogether by the querulous garrulity of an elderly invalid rather than the rapturous, demon-haunted landscapes of a romantic poet in prose.

In either case, you will soon be making the acquaintance of the doomed, tragic Ann, a romantic heroine on a par with Wordsworth's Lucy, Coleridge's Christabel, or Emily Brontë's Cathy Earnshaw. In this case, however, she may well have been real.

•

James Archer: Thomas De Quincey (1855)

Thomas De Quincey

(1785-1859)

De Quincey, Thomas. The Collected Writings: New and Enlarged Edition. Ed. David Masson. 14 vols. 1889-90. London: Adam & Charles Black, 1896-1897:Autobiography from 1785 to 1803Autobiography and Literary ReminiscencesLondon Reminiscences and Confessions of an Opium-EaterBiographies and Biographic Sketches (1)Biographies and Biographic Sketches (2)Historical Essays and Researches (1)Historical Essays and Researches (2)Speculative and Theological EssaysPolitical Economy and PoliticsLiterary Theory and Criticism (1)Literary Theory and Criticism (2)Tales and RomancesTales and Prose PhantasiesMiscellanea and Index

De Quincey, Thomas. The Collected Writings. Ed. David Masson. 14 vols. Vol. I: Autobiography from 1785 to 1803. London: Adam & Charles Black, 1889.

Eaton, Horace A., ed. A Diary of Thomas De Quincey, 1803: Here Reproduced in Replica as well as in Print from the Original Manuscript in the Possession of the Reverend C. H. Steel. London: Noel Douglas, [1927].

Van Doren Stern, Philip, ed. Selected Writings of Thomas De Quincey. London: The Nonesuch Press / New York: Random House, n.d. [1939].

De Quincey, Thomas. Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, Together with Selections from the Autobiography. Ed. Edward Sackville-West. London: The Cresset Press, 1950.

De Quincey, Thomas. Confessions of an English Opium-Eater in Both the Revised and the Original Texts, with its Sequels "Suspiria de Profundis" and "The English Mail-Coach". Ed. Malcolm Elwin. MacDonald Illustrated Classics. London: MacDonald & Co. (Publishers) Ltd., 1956.

De Quincey, Thomas. Confessions of an English Opium-Eater. 1821. Ed. Alethea Hayter. 1971. Penguin English Library. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1979.

De Quincey, Thomas. Recollections of the Lakes and the Lake Poets. 1834-40. Ed. David Wright. 1970. Penguin English Library. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972.

"The Pains of Opium"

Giovanni Piranesi: Carceri [Prisons] XIV (1761)

•

Published on December 22, 2017 12:14

December 15, 2017

Teddy Boy

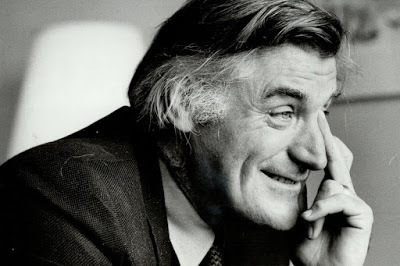

Ted Hughes (1930-1998)

The first time I met Bill Manhire was at a poetry festival in Tauranga in 1998. He was standing there discussing the poetry of Ted Hughes with fellow featured poet Brian Turner. The two of them seemed, if anything, quite respectful of Hughes's oeuvre.

With bumptious self-confidence, I thrust myself into the centre of their conversation and remarked how seond-rate I thought most of Hughes's poetry was.

"Well, perhaps," replied Manhire, politely. "But Tales from Ovid was good."

"Yeah, I'd hoped that would be an exception, but even that seemed pretty bad to me," I riposted.

After that Manhire didn't seem to want to talk to me any more. I wonder why? It remains a bit of a mystery to me to this day, twenty years on.

Tony Lopez: False Memory (1996)

It wasn't the first time that Ted Hughes had got me into trouble. When I first went abroad to study, I recall a conversation in a pub where I ventured the opinion - to the young visiting poet Tony Lopez, who was spending a few semesters teaching at Edinburgh University - that people had seemed to rate Ted Hughes' work quite highly before he was appointed as Poet Laureate, but that the job was definitely the kiss of death for poets.

Lopez denounced this view with fierce indignation. No-one serious had ever rated Ted Hughes, according to him, and the comparison I'd dared to venture with Seamus Heaney was simply ridiculous, and showed how little I knew about the matter.

Lopez could be quite a gentle, nurturing person - but he also had this fiery, vituperative side. After a while we took to referring to these two aspects of his personality as 'Jekyll Lopez' and 'Hyde Lopez.' Certainly I was a little taken back by the vehemence with which he cut me down to size. Clearly it mattered deeply to him that Ted Hughes remain where he belonged: in the dogbox (or should I say the crow's-nest?).

That exchange with Lopez must have been in the late 1980s sometime. The conversation with Manhire was in March 1998 (I known because I just looked up the dates of that poetry Festival online). I'm not sure if news of Hughes's last book Birthday Letters had yet reached New Zealand, but it may well have formed the topic of Manhire and Turner's discussion, given it came out in January 1998 (according to Ann Skea's very useful Ted Hughes timeline).

Hughes died on October 28th 1998, shortly after being awarded the OM, but also shortly before Birthday Letters won the T.S. Eliot Prize for Poetry, the South Bank Award for Literature, and the Whitbread Prize for Poetry and the Book of the Year prize.

Ted Hughes: Birthday Letters (1998)

It's hard to convey now, twenty years later, just how bizarre the appearance of Birthday Letters seemed at the time. Talk about a twice-told tale! Sylvia Plath had died in 1963, some 35 years before. Her work was legendary: taught in virtually every tertiary institution - not to mention high school - in the English-speaking world. There had already been a whole slew of biographies and "responses" to her life and sufferings.

This is just a selection of the ones I happen to own copies of myself:

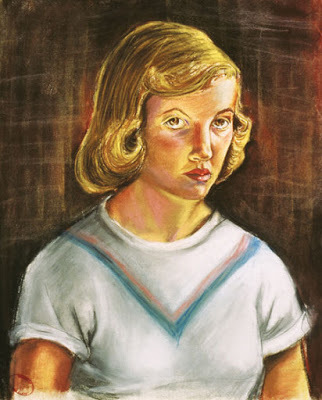

Sylvia Plath: Self-portrait (1951)

Steiner, Nancy Hunter. A Closer Look at Ariel: A Memory of Sylvia Plath. Afterword by George Stade. 1973. London: Faber, 1976.

Kyle, Barry. Sylvia Plath: A Dramatic Portrait, Conceived and Adapted From Her Writing. 1976. London: Faber, 1982.

Stevenson, Anne. Bitter Fame: A Life of Sylvia Plath. With Additional Material by Lucas Myers, Dido Merwin, and Richard Murphy. 1989. New Preface. London: Penguin, 1998.

Malcolm, Janet. The Silent Woman: Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes. 1993. Picador. London: Pan Macmillan General Books, 1994.

Anne Stevenson

While still at Edinburgh, I'd gone to a most interesting talk by Sylvia's biographer (and near-contemporary) Anne Stevenson where she discussed the difficulties of working with the Hughes estate (and, in particular, with his redoubtable sister Olwyn) on her Plath biography. She said that Olwyn would have to be regarded as virtually the co-author of the book, so extensive was her involvement with each chapter of it.

Ted, she said, by contrast, remained aloof from the whole business and seemed to regard it as all water under the bridge.

There seemed a certain dignity in this attitude, this Olympian refusal to comment, and while it did seem a little odd that - by a strange accident of history - Hughes had ended up in complete charge of Sylvia Plath's literary estate, and had thus edited all of her posthumous books, from Ariel (1965) onwards, including the Collected Poems (1981) and (most controversially) a selection from her Journals (1982) - there didn't seem to be anything much there to indicate any systematic desire to falsify her legacy.

But now, in the last year of his life, he'd come back punching, determined to comment on virtually every aspect of their life together, particularly those parts recorded in the searing personal poems written towards the end of her life. Talk about wanting to have the last word!

And the poems were so strange! He claimed to have been writing them continuously over the previous thirty years, but they read as if they'd been poured out in one amorphous mass, taking their cue from the taut, coiled-spring artefacts Plath had bequeathed to the world.

Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath (her version)

Take their respective poems entitled "The Rabbit Catcher," for instance:

Sylvia Plath:

The Rabbit Catcher

It was a place of force —

The wind gagging my mouth with my own blown hair,

Tearing off my voice, and the sea

Blinding me with its lights, the lives of the dead

Unreeling in it, spreading like oil.

I tasted the malignity of the gorse,

Its black spikes,

The extreme unction of its yellow candle-flowers.

They had an efficiency, a great beauty,

And were extravagant, like torture.

There was only one place to get to.

Simmering, perfumed,

The paths narrowed into the hollow.

And the snares almost effaced themselves —

Zeros, shutting on nothing,

Set close, like birth pangs.

The absence of shrieks

Made a hole in the hot day, a vacancy.

The glassy light was a clear wall,

The thickets quiet.

I felt a still busyness, an intent.

I felt hands round a tea mug, dull, blunt,

Ringing the white china.

How they awaited him, those little deaths!

They waited like sweethearts. They excited him.

And we, too, had a relationship —

Tight wires between us,

Pegs too deep to uproot, and a mind like a ring

Sliding shut on some quick thing,

The constriction killing me also.

Given it's already available online here, I've taken advantage of this fact to quote the poem in full. I wouldn't normally do this, but it's so tightly constructed that it's hard to make sense of otherwise.

Plath brilliantly evokes the atmosphere of an oncoming fugue or other psychological event ("a hole in the hot day, a vacancy / The glassy light was a clear wall") but otherwise concentrates almost entirely on her own reactions to this "place of force."

The imagery of the snares ("Zeros, shutting on nothing, // Set close, like birth pangs") contrasts them tellingly against the "little deaths" that excite the man who set them "like sweethearts".

And, of course, at the end of the poem, the snare she's been carefully constructing throughout springs shut and catches her own man, with his "mind like a ring / Sliding shut on some quick thing, / The constriction killing me also."

Is it a fair, a balanced poem? Not really, no. Should it be? According to whose criteria? Clearly it's struck a chord with hundreds of thousands of readers since it first appeared in the early sixties. It may not be as anthemic as "Lady Lazarus" or "Daddy", but it's perhaps all the more effective for that in portraying a woman's experience of a constrictive relationship.

Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath (his version)

So what of Ted's poem? (Which I've once again been able to quote in full, thanks to its previous appearance on the crushed fingers blog: apologies to any copyright holders I may have inadvertently offended by reprinting it here: I promise to remove it immediately if there are any complaints):

Ted Hughes:

The Rabbit Catcher

It was May. How had it started? What

Had bared our edges? What quirky twist

Of the moon’s blade had set us, so early in the day,

Bleeding each other? What had I done? I had

Somehow misunderstood. Inaccessible

In your dybbuk fury, babies

Hurled into the car, you drove. We surely

Had been intending a day’s outing,

Somewhere on the coast, an exploration —

So you started driving.

What I remember

Is thinking: She’ll do something crazy. And I ripped

The door open and jumped in beside you.

So we drove West. West. Cornish lanes

I remember, a simmering truce

As you stared, with iron in your face,

Into some remote thunderscape

Of some unworldly war. I simply

Trod accompaniment, carried babies,

Waited for you to come back to nature.

We tried to find the coast. You

Raged against our English private greed

Of fencing off all coastal approaches,

Hiding the sea from roads, from all inland.

You despised England’s grubby edges when you got there.

The day belonged to the furies. I searched the map

To penetrate the farms and private kingdoms.

Finally a gateway. It was a fresh day,

Full May. Somewhere I’d brought food.

We crossed a field and came to the open

Blue push of sea-wind. A gorse cliff,

Brambly, oak-packed combes. We found

An eyrie hollow, just under the cliff-top.

It seemed perfect to me. Feeding babies,

Your Germanic scowl, edged like a helmet,

Would not translate itself. I sat baffled.

I was a fly outside on the window-pane

Of my own domestic drama. You refused to lie there

Being indolent, you hated it.

That flat, draughty plate was not an ocean.

You had to be away and you went. And I

Trailed after like a dog, along the cliff-top field-edge,

Over a wind-matted oak-wood —

And I found a snare.

Copper-wire gleam, brown cord, human contrivance,

Sitting new-set. Without a word

You tore it up and threw it into the trees.

I was aghast. Faithful

To my country gods — I saw

The sanctity of a trapline desecrated.

You saw blunt fingers, blood in the cuticles,

Clamped around a blue mug. I saw

Country poverty raising a penny,

Filling a Sunday stewpot. You saw baby-eyed

Strangled innocents, I saw sacred

Ancient custom. You saw snare after snare

And went ahead, riving them from their roots

And flinging them down the wood. I saw you

Ripping up precarious, precious saplings

Of my heritage, hard-won concessions

From the hangings and transportations

To live off the land. You cried: ‘Murderers!’

You were weeping with a rage

That cared nothing for rabbits. You were locked

Into some chamber gasping for oxygen

Where I could not find you, or really hear you,

Let alone understand you.

In those snares

You’d caught something.

Had you caught something in me,

Nocturnal and unknown to me? Or was it

Your doomed self, your tortured, crying,

Suffocating self? Whichever,

Those terrible, hypersensitive

Fingers of your verse closed round it and

Felt it alive. The poems, like smoking entrails,

Came soft into your hands.

Well, first of all, you'll notice its length. It's immense! Sylvia gets all her effects in 30 taut lines. Ted, by contrast, takes 77 to refute - or should I say, more politely, supplement? - her version of events.

it's written in a loose, conversational style - with Hughes' usual plethora of adjectives and analogies as as substitute for thought. Essentially, it's a 'she-said, he-said' rewriting of the narrative of this particular picnic.

And, guess what? It was all her fault. She was the one who was in a "dybbuk fury" over something he doesn't even remember doing ("What had I done? I had / Somehow misunderstood"). He, by contrast, was the essence of cool reasonableness: "I simply / Trod accompaniment, carried babies, / Waited for you to come back to nature."

What's more, she shows a distinct lack of respect for the beauty of the English countryside: "You despised England’s grubby edges" - all in all, "The day belonged to the furies." In fact, if it hadn't been for him, they wouldn't even have got to the coast: "I searched the map / To penetrate the farms and private kingdoms ... Somewhere I’d brought food ... We found / An eyrie hollow, just under the cliff-top. / It seemed perfect to me."

I'm a guy myself. Self-justification comes naturally to me. I guess that's why I notice all the techniques of defensiveness in the passage above. I bought the food; I read the map; I found the perfect picnic spot - so what's your problem, bee-atch?

Actually, maybe it's a cultural thing: "Your Germanic scowl, edged like a helmet, / Would not translate itself. I sat baffled." Oh, right, it's because you're such a Nazi that we weren't getting on that day. I suppose Hughes was entitled to feel a little peeved at that famous passage in Plath's poem "Daddy" which appears to equate him with:

A man in black with a Meinkampf lookBut, hey, listen up: you're the one who's a big fascist, not me. Ripping up the snares, which Plath describes as such an act of liberation, is in reality an offence against his "country gods" and the "sanctity" of "Ancient custom":

And a love of the rack and the screw.

And I said I do, I do.

I saw youIt's a bit hard to tell at this stage, but do those last two lines equate her with someone in a gas chamber? Plath herself got into trouble with her propensity to draw parallels between herself and the victims of the Holocaust:

Ripping up precarious, precious saplings

Of my heritage, hard-won concessions

From the hangings and transportations

To live off the land. You cried: ‘Murderers!’

You were weeping with a rage

That cared nothing for rabbits. You were locked

Into some chamber gasping for oxygen

An engine, an engineIs Hughes meaning to confirm the equation here, or undermine it? In any case, one thing's for sure, her rage "cared nothing for rabbits'. They were just bit-parts in her own one-woman show, shaped by the "terrible, hypersensitive / Fingers of [her] verse".

Chuffing me off like a Jew.

A Jew to Dachau, Auschwitz, Belsen.

So, to sum up: Sylvia in a temper was not a pretty sight, and there seemed every risk that she might even harm the children ("What I remember / Is thinking: She’ll do something crazy"). She was quite inaccessible to reason while in this "dybbuk fury", and drove like a maniac while Ted was kept busy minding babies, buying food, reading maps, and steering them towards ideal picnic spots. She simply didn't understand about traplines and snares, seeing them (wrongly) in terms of "baby-eyed / Strangled innocents" instead of as providing pennies for the "Sunday stewpot". In short, she was wrong and he was right, and it's about time the record was set straight on the matter.

It's hard to explain precisely how I feel about this approach to past woes. On the one hand, Birthday Letters is a fascinating book to read, in a kind of tell-all, spill-the-beans way, and the loose, anecdotal nature of the verse certainly doesn't detract from its page-turning qualities.

On the other hand, while I'm no stranger to relationship discord and the passionate desire to justify oneself, there seems something intensely ungentlemanly about setting the record straight in this bald, completely one-sided way, so many years later, when the only other substantive witness has been dead for thirty-odd years. It's one thing to plead one's own cause: it's quite another to publish a whole book on the subject, a book which might as well have been entitled "Why I was Right All Along and She was Quite Wrong". The timing of the whole thing seems odd, too.

I respected the dignity of his silence: his refusal to talk about anything substantive except the canon of his wife's work. It was difficult not to. But it's a little harder to respect the impulse that gave rise to Birthday Letters, though, however much you may admire it as poetry (I don't, really).

I can't help recalling the passage in Elizabeth Bishop's great letter to Robert Lowell, protesting the use, in his book The Dolphin (1973), of edited excerpts from his wife's letters, sent to him while he was in the process of leaving her for another woman:

One can use one's life as material - one does, anyway - but these letters, aren't you violating a trust? IF you were given permission - IF you hadn't changed them ... etc. But art just isn't worth that much. I keep remembering Hopkins's marvelous letter to Bridges about the idea of a "gentleman" being the highest thing ever conceived - higher than a "Christian," even, certainly than a poet. It is not being "gentle" to use personal, tragic, anguished letters that way — it's cruel. - Elizabeth Bishop. One Art: Letters. Selected and edited by Robert Giroux (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1994): 562.

Elizabeeth Bishop & Robert Lowell

So is that all there is to Ted Hughes? The ogre of legend, the wife-killer - Assia Wevill, the woman he left Sylvia for, also killed herself (and her daughter), unfortunately. What is it Lady Bracknell says in The Importance of Being Earnest? "To lose one parent, Mr Worthing, may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness." That applies even more to Significant Others, one would have thought.

And yet, and yet ... his poetry has never precisely appealed to me, but there's so much of it - he was so prolific, and the sheer ambition and heft of his Collected Poems surely deserves some closer attention.

Poetry Foundation

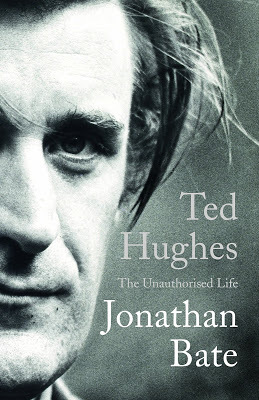

I can't say he's been terribly fortunate in his biographers (so far, at least). I've read both the fairly anodyne one by Elaine Feinstein which came out within a couple of years of his death, and the far fuller and really quite terrifying "Unauthorised" one by Jonathan Bate, which appeared in 2015: in fact it's glaring at me from the shelves right now.

What I have enjoyed reading, I must admit, is the volume of his letters, edited by Christopher Reid, which appeared in 2007. He comes across as a very human character, finally, in these. Opinionated, certainly, but one begins to understand the charisma of his personality.

There are some other very worthwhile Ted Hughes books out in the world now: the Collected Poems for Children has an almost Walter de la Mare like charm (as do his four small volumes of Collected Animal Poems). His Selected Translations show a really formidable talent for making foreign-language poetry sing in English - and a far greater engagement with verse translation than I think anyone would have suspected.

So, all in all, I feel like a bit of a fool for my easy dismissals of Ted Hughes back in the day, back when I was young and brash and opinionated and ready to rely on snap judgements rather than giving each writer the benefit of the doubt (at least initially). In fact, if it weren't that I read so many precisely similar dismissals - generally on even dafter grounds - in Hughes's own letters, I'd feel quite ashamed of myself.

Teddy Boys

Teddy Boy, yes: it seems to fit somehow. Those Teds sure dress up fine, but there's a basic violence in their hearts. I still think that it's right to retain one's suspicions of outright Ted Hughes fans, but there's no doubt that he remains a force to be reckoned with - and many of his poems, especially the animal and childhood pieces, are just excellent of their kind. It makes a big difference hearing him read them out loud himself, too: his Yorkshire accent picks out the details of the words in ways a plummy Home Counties voice never could.

Here's a list of my Hughes-iana to date:

•

Poetry Foundation

Edward James Hughes

(1930-1998)

Poetry:

The Hawk in the Rain. 1957. Faber Paper Covered Editions. London: Faber, 1972.

Lupercal. 1960. Faber Paper Covered Editions. London: Faber, 1973.

Wodwo. 1967. Faber Paperbacks. London: Faber, 1977.

Crow: From the Life and Songs of the Crow. 1972. Faber Paperbacks. London: Faber, 1981.

Moon-Whales. 1976. Illustrated by Chris Riddell. 1988. London: Faber, 1991.

Gaudete. 1977. London: Faber, n.d.

Cave Birds: An Alchemical Cave Drama. Drawings by Leonard Baskin. London: Faber, 1978.

Moortown. Drawings by Leonard Baskin. Faber Paperbacks. London: Faber, 1979.

Selected Poems 1957-1981. London: Faber, 1982.

New Selected Poems 1957-1994. London: Faber, 1995.

Collected Animal Poems. 4 vols. London: Faber, 1996.Volume 1 – The Iron Wolf, illustrated by Chris RiddellVolume 2 – What is the Truth? illustrated by Lisa FlatherVolume 3 – A March Calf, illustrated by Lisa FlatherVolume 4 – The Thought-Fox, illustrated by Lisa Flather

Birthday Letters. 1998. London: Faber, 1999.

Collected Poems. Ed. Paul Keegan. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003.

Ted Hughes Reading His Poetry. 1977. Set of 2 CDs. London: HarperCollins, 2005.

Collected Poems for Children. Illustrated by Raymond Briggs. 2005. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007.

Translation:

Seneca’s Oedipus: An Adaptation. 1969. Faber Paperbacks. London: Faber, 1975.

Selected Translations. Ed. Daniel Weissbort. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006.

Fiction:

How the Whale Became and Other Stories. Illustrated by George Adamson. 1963. A Young Puffin. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983.

The Iron Man: A Story in Five Nights. Illustrated by George Adamson. 1968. Faber Paper Covered Editions. London: Faber, 1975.

Difficulties of a Bridegroom: Collected Short Stories. 1995. London: Faber, 1996.

The Dreamfighter and Other Creation Tales. London: Faber, 2003.

Non-fiction:

Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being. 1992. London: Faber, 1993.

Winter Pollen: Occasional Prose. Ed. William Scammell. 1994. London: Faber, 1995.

Letters:

Letters of Ted Hughes. Ed. Christopher Reid. London: Faber, 2007.

Secondary:

Wagner, Erica. Ariel’s Gift: A Commentary on Birthday Letters by Ted Hughes. 2000. London: Faber, 2001.

Feinstein, Elaine. Ted Hughes: The Life of a Poet. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2001.

Koren, Yehuda, & Eilat Negev. A Lover of Unreason: The Life and Tragic Death of Assia Wevill. London: Robson Books, 2006.

Bate, Jonathan. Ted Hughes: The Unauthorised Life. Fourth Estate. Sydney: HarperCollins Publishers, 2015.

And, just to put things in perspective, here are the books I have by Sylvia Plath:

•

A Poem for Every Day

Sylvia Plath

(1932-1963)

Poetry:

The Colossus: Poems. 1960. London: Faber, 1977.

The Bell Jar. 1963. London: Faber, 1974.

Ariel. 1965. London: Faber, 1974.

Ariel: The Restored Edition. A Facsimile of Plath's Manuscript, Reinstating Her Original Selection and Arrangement. 1965. Foreword by Frieda Hughes. 2004. London: Faber, 2007.

Collected Poems. Ed. Ted Hughes. Faber Paperbacks. London: Faber, 1981.

Fiction:

Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams and Other Prose. Ed. Ted Hughes. 1977. London: Faber, 1979.

Collected Children’s Stories. 1976 & 1996. Illustrated by David Roberts. Faber Children’s Classics. London: Faber, 2001.

Letters & Journals:

Letters Home: Correspondence 1950-63. Ed. Aurelia Schober Plath. 1975. A Bantam Book. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc., 1977.

Kukil, Karen V., ed. The Journals of Sylvia Plath, 1950-1962: Transcribed from the Original Manuscripts at Smith College. 2000. London: Faber, 2001.

•

Sylvia, with Frieda and Nicholas

Published on December 15, 2017 14:54

December 10, 2017

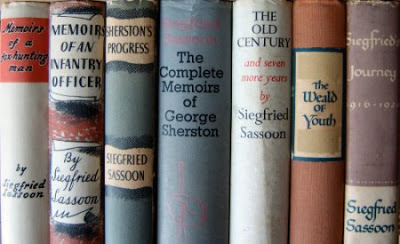

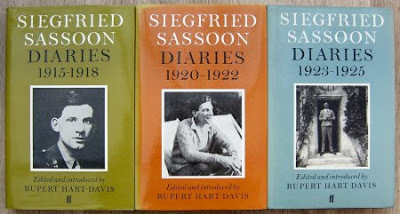

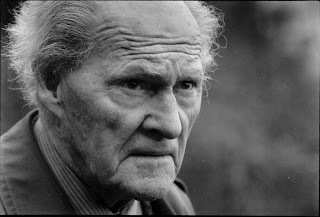

Why Siegfried Sassoon?

George Charles Beresford: Siegfried Sassoon (1915)

A visitor to the house once asked me why there was so much war poetry in the bookcases in the living room: more specifically, why there were so many books by Robert Graves, Siegfried Sassoon and Edward Thomas, and nothing by Wilfred Owen, who is generally regarded as the pick of the bunch? I had to admit she had me there. Why wasn't there any Wilfred Owen? I've since repaired that omission, but it's interesting to me (at least) that it occurred in the first place.

I wouldn't say that I was exceptionally keen on war poetry. Certainly I've read all the usual suspects, and have a number of books on the subject, but it's not really one of my absolute areas of fanatical interest. I do love Edward Thomas, though (as my previous post on the subject should testify). And my fascination with the strange reaches of Robert Graves's imagination remains unabated. Why so much by Siegfried Sassoon, though?

Lady Ottoline Morrell: Siegfried Sassoon and Robert Graves (1920)