Jack Ross's Blog, page 27

December 2, 2016

Movies about Writers

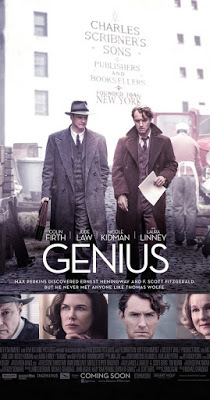

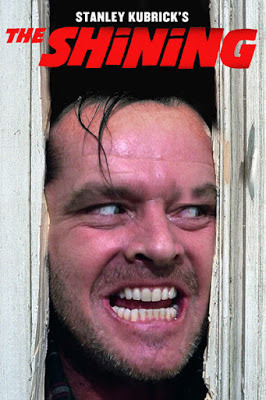

Michael Grandage, dir. Genius (2016)

There's a very funny scene in Evelyn Waugh's novel Vile Bodies (1930) where his usual cast of upper-class snots have decided to make a film. For some incomprehensible reason, they've chosen the life of Methodist firebrand John Wesley as their subject, but are then faced with the inevitable problem of how to make a writer writing seem even vaguely dramatic.

The scene they end up is supposed to show Wesley writing a sermon, and so he does - for five minutes or so - dipping his pen in the ink and scribbling away. Needless to say, the movie is not a great success.

No doubt this was the inspiration for the Monty Python segment showing Thomas Hardy writing his latest novel in front of a huge stadium of adoring fans: "He's written a sentence," gasps the announcer. "Now he's crossed it out!" Due consultation of the manuscript of Jude the Obscure does indeed show a certain amount of indecision over the ideal wording for his opening.

It is, in other words, extremely difficult to make a good movie about a writer. Most of their lives are spent sitting at a desk of some sort, scribbling words with pencils or pens, or banging them out on a typewriter or a computer. Some (such as Rider Haggard) were forced by their various aches and pains to work standing up at a lectern; others (such as Henry James) would walk up and down dictating to a secretary; still others (such as Barbara Cartland - or Patricia Highsmith, for that matter) never actually got out of bed, but instead wrote with a ridge of comforting bedclothes nestled around them.

Whatever they did, however they did it, it's just not very watchable. It's not like the life of a soldier or an athlete - or even a politician. Everything significant in a writer's life goes on behind the scenes.

Be that as it may, I thought I'd assemble a bunch of representative examples to show some of the solutions ingenious directors have come up with. These can be broken down roughly as follows -

•

Woman-behind-the-man films:

Ralph Fiennes, dir. The Invisible Woman (2013)

Charles Dickens did have the advantage of being almost absurdly energetic in his daily life (after his long stint writing each morning, that is). The Invisible Woman tells the tale of his young mistress Ellen Lawless Ternan who - according to the movie, at any rate - was more-or-less pimped out to him by her own mother, who was finding it a bit difficult to make ends meet as an itinerant actor, and had to face the fact that Ellen showed no great talent as a Thespian. It's quite a tragic tale, and certainly doesn't present the old dog Dickens in a particularly flattering light.

Michael Hoffman, dir. The Last Station (2009)

Lev Tolstoy was - if anything - even more of a bastard, if this movie is anything to go by. It's funny how being obsessed with social reform and general injustice has now become a kind of stigma, rather than an accolade. Tolstoy's politics may have been a bit naive (I don't know: were they? They sound pretty sensible to me), but the film gives the usual line that he was wasting time which could have been spent on writing more novels like War and Peace or Anna Karenina (rather than ones like Resurrection). I doubt his Countess Sonya was quite so winsome as Helen Mirren makes her, but certainly - if you consider the rights of aristocrats to keep on living in the style to which they're accustomed as the ultimate aim of humanity - she did get a bit of raw deal. I don't know. It's pretty easy to criticise a person like Tolstoy. It must have been rather harder to be him - given that he clearly possessed that awkward thing called a conscience, and therefore could not be content just to enjoy his own wealth and power. Lovely movie, but not really, in the final analysis, at all profound or up to its subject.

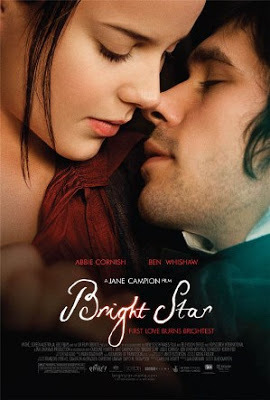

Jane Campion, dir. Bright Star (2009)

John Keats comes out a bit better in this surprisingly sensitive and even moving bio-pic by Jane Campion. Anyone who's read Fanny Brawne's letters to Keats's sister knows that she was never the heartless minx portrayed in early hagiographies of the poet. Campion even manages to get in some not-too-unconvincing "writing a poem" moments into her film - but the heart of it is, of course, the love story. You'd have to be pretty hard-hearted not to see the poignancy of that: Fanny staying up all night to embroider a pillow-slip for the head of Keats's dead brother to rest on in his coffin was particularly affecting, I thought.

John Madden, dir. Shakespeare in Love (1998)

William Shakespeare almost certainly bore no resemblance whatsoever to the impulsive protagonist of this film - but then Tom Stoppard never supposed he did, which is why his screenplay is so full of in-jokes about the absurdity of bardolatry (the "Present from Stratford" mug in one of the scenes is a very nice touch). Perhaps that tongue-in-cheek flavour is why this is such a wonderful film. Even Paltrow-phobes (and we are many, I fear) can tolerate her in this role - though any pretence she could pass for a boy for even a second is, of course, absurd. The great thing is that it's meant to be. None of the cross-dressing feats in the Bard's surviving plays are much more convincing, after all.

Dan Ireland, dir. The Whole Wide World (1996)

Robert E. Howard may seem a little out of place among such exalted company, but those of us brought up on his - still surprisingly readable and entertaining - "Conan" yarns would see him as every bit as influential a writer as his more high culture contemporaries. This is the interesting tale of a young schoolteacher who got to know him in his final years. I'd say it was at least as good as Genius, the more recent Thomas Wolfe bio-pic pictured at the top of this post.

Richard Attenborough, dir. Hemingway in Love and War (1996)

This doesn't quite work as a movie, I'm afraid. It's interesting to learn how closely Ernest Hemingway's classic A Farewell to Arms was based on his own experiences in the war, but unfortunately it leaves one with more of an appetite to reread the novel than to speculate on just how all this suffering "made" him into a writer. Sandra Bullock does her best, but it's hard to stop the story subsiding into banality, which A Farewell to Arms somehow miraculously avoids by the sheer beauty and precision of its writing.

Brian Gilbert, dir. Tom & Viv (1994)

T. S. Eliot was clearly quite a hard person to warm to, but the hatchet-job which is Tom and Viv still takes a bit of justification. Vivienne Eliot was barking mad - there's no serious doubt about that. Even a couple of minutes of her on-screen is pretty hard to take, but when you think of the years and years of her antics Eliot had to endure, The Waste Land suddenly turns into a realist text. It may have made him a great poet (doubtful: "Prufrock" preceded her influence), but it's hard to imagine the kind of mind prepared to stand back and sneer at his final anguished decision to have her committed. It does all add up to a pretty good story, I suppose, but one that's a bit hard to justify in the real world.

Philip Kaufman, dir. Henry & June (1990)

Henry Miller had a lot to say about his sex-life, late and early. And it seems that the reams Anais Nin wrote about her own included the above interesting take on the events that inspired Tropic of Cancer, as well as Miller's later Rosy Crucifixion trilogy. Uma Thurman, as the "June" of the title, makes a rather unconvincing femme fatale, and all in all it might have been better to leave them all to the merciful shelter of the printed page. There are many laughs in the film, admittedly, but I fear the majority of them are unintentional. Richard E. Grant does his usual wide-eyed "which-movie-am-I-actually-in-this-week?" act. It's hard to say what the rest of them think they're doing, or what planet they're on.

•

Women-writers-getting-out-from-under films:

Tony Issac, dir. Iris (1984)

For a made-for-TV movie, this one isn't so bad. Helen Morse is very good as NZ writer Iris Wilkinson (aka Robin Hyde), though the whole thing could probably do with a more up-to-date remake sometime.

Michael Firth, dir. Sylvia (1985)

This, too, about NZ writer Sylvia Ashton-Warner is a valiant pioneering effort. It's a shame that (once again) an English person had to be imported to play a New Zealander, but Eleanor David certainly did a bang-up job.

Jane Campion, dir. An Angel at My Table (1990)

Jane Campion's Janet Frame film still holds up surprisingly well, 25 years on. The performances by the three leads are uniformly excellent - and the visual style of the thing reminds just why she is what she is: one of the greatest filmmakers (perhaps the greatest?) ever to come out of New Zealand.

Christine Jeffs, dir. Sylvia (2003)

This one, alas, is a bit of a mess. Daniel Craig makes a surprisingly good job of playing Ted Hughes, but Gwyneth Paltrow's Sylvia Plath has mercifully faded from the memory of all but the most dedicated movie-goers. It wasn't helped by the fact that the film-makers don't appear to have been allowed to quote any of Plath's actual poetry, so her character flaws are allowed free rein with little to offset them. I do recall some pretty scenery here and there - a nice boating scene off the coast of Cornwall (filmed here, I believe: near Dunedin), but the attempts to dramatise Sylvia's "breaking free" of her oppressive husband are, I fear, pretty unconvincing.

•

Byron-'n'-Shelley-'n'-Mary-Shelley films:

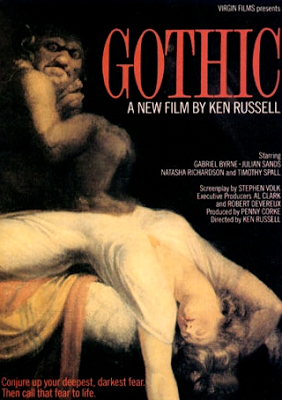

Ken Russell, dir. Gothic (1986)

This is an interesting sub-genre of the above. Clearly something happened that summer on Lake Geneva to inspire Mary Shelley's immortal Frankenstein - and it seems to have involved a lot of nightmares, thunderstorms, and prancing around naked on battlements (in Ken Russell's version, at least). Gothic isn't (as the title suggests) exactly a subtle film, but it's certainly very entertaining.

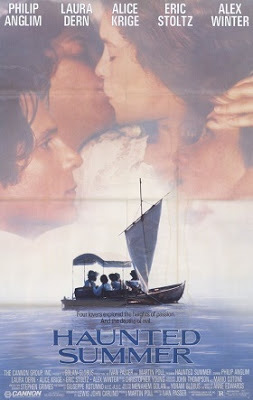

Ivan Passer, dir. The Haunted Summer (1988)

Which is more than can be said for this pallid effort. The "Frankenstein" effects mainly consist of an elaborate practical joke played on Lord Byron by his rather absurd "private physician" Dr. Polidori (or Polly-Dolly, as Byron called him). Given Polidori is played by Alex Winter, more familiar to most of us as Keanu Reeves' sidekick in the Bill & Ted films (complete with painfully overdone upper class accent), the whole thing falls rather flat.

Roger Corman, dir. Frankenstein Unbound (1990)

Unlike Roger Corman's splendidly weird version of Brian Aldiss's SF rewriting of the whole saga. Bridget Fonda plays the most spunky and spirited Mary Shelley to date, and Raul Julia's "Frankenstein" make-up has to be seen to be believed (though the poster above does give you a bit of an idea).

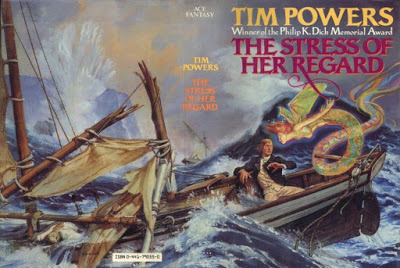

After that, I think the moguls of Hollywood must have thought better of following it up with a film of Liz Lochead's Dreaming Frankenstein or any of the many, many other versions of the story which continue to appear (my own personal favourite is Tim Powers' The Stress of Her Regard. Now that would make a pretty entertaining film, I reckon ...)

Anyway, that's my best attempt at an analysis of some of the more recent highlights of the genre. Feel free to point out any I've missed (I'm sure they must be legion).

Tim Powers: The Stress of Her Regard (1989)

Published on December 02, 2016 14:35

November 25, 2016

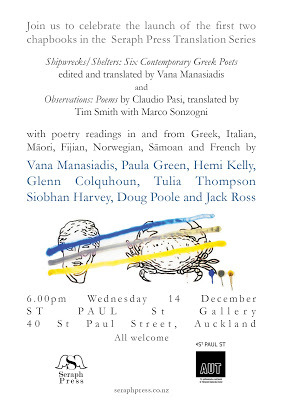

Poetry in Translation: Reading 14/12/16

Seraph Press Translation Series

•

When: Wednesday 14 December, 6.00-8.00pm

Where: St Paul St Gallery, 40 St Paul Street,

Auckland Central (behind AUT)Poetry readings in and from Greek, Italian, Māori, Fijian, Norwegian, Sāmoan and French by Vana Manasiadis, Paula Green, Hemi Kelly, Glenn Colquhoun, Tulia Thompson, Siobhan Harvey, Doug Poole and Jack Ross.

All welcome.

•

Join us at this pre-Christmas reading, organised by Seraph Press to celebrate the launch of the first two chapbooks in their new Translation Series:

Vana Manasiadis, ed. & trans.: Shipwrecks/Shelters (Wellington: Seraph Press, 2016)

Shipwrecks/Shelters: Six Contemporary Greek Poets / Ναυάγια/Καταφύγια: Έξι Σύγχρονοι Έλληνες Ποιητές, edited and translated by Vana Manasiadis

Claudio Pasi: Poems (Wellington: Seraph Press, 2016)

Observations: Poems / Osservazione: Poesie, by Claudio Pasi, translated by Tim Smith with Marco Sonzogni

•

St Paul St Gallery (AUT)

•

Published on November 25, 2016 12:06

November 10, 2016

Two Versions of Shirley Jackson

Ruth Franklin: Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (2016)

When I heard there was a new biography of Shirley Jackson available - presumably published to coincide with the centenary of her birth - I ordered it pretty much straight away. True, the existing one did seem to cover most of the necessary bases in her unfortunately brief life - she died of a heart attack at the age of 48 - but there's always something new to be learned, and she is one of my favourite writers.

Judy Oppenheimer: Private Demons: The Life of Shirley Jackson (1988)

What was the justification for this new version of Jackson? Had a lot of fresh information come to light in the 28 years since Judy Oppenheimer's book appeared? Or was it just an attempt to supply some new emphases? I was a little irritated to find no discussion of the topic in Franklin's introduction. In fact, there was no mention there at all of the earlier book. So I went to her index instead. Nothing. Literally nothing. Nothing in the Acknowledgments, or the Permissions. In fact, so far as the text of Franklin's book is concerned, it's as if Oppenheimer's book had never existed.

This seemed quite strange to me. When I started to look through the source notes at the back of her book, though, the mystery was compounded. Oppenheimer's book was there, all right. It didn't have an abbreviation of its own, unlike virtually every other text used by Franklin, but it came up again and again, in note after note.

For the most parts, these notes were confined to page references to establish points of fact. It seemed as if a great many facts had been gleaned Judy Oppenheimer's pioneering work. But after a while I started to notice that every discussion of a particular point of detail from the previous book attempted to refute it - often quite savagely. Here are a few examples:

"I have always loved" ... This line comes from a document that Judy Oppenheimer, SJ's first biographer, identifies (I believe incorrectly) as an unsent letter from SJ to Howard Nemerov ... (p.506)Virtually everything else in these notes is "by gracious permission of" or "so-and-so kindly allowed me to see" - but not the details from Oppenheimer. She could be used when convenient, it seemed, but any chance to dispute her views or interpretations must be seized with both hands.

a thousand words a day: Oppenheimer, Private Demons, 45. This number has been repeated often by others, but I was unable to confirm it independently. (p.513)

"my rape" ... Judy Oppenheimer provides a conflicting account of SJ's loss of virginity based on interviews with SJ and SEH's friends, in which their first attempt to consummate their relationship was ruined by friends who barged in on them; on their second attempt, Hyman was supposedly too nervous to perform (Private Demons, 68-69). These stories are impossible to verify. Oppenheimer does not mention the letter or the journal entry. (524)

reenact the scene: Oppenheimer gives this as SJ's strategy for Hill House, but Sarah Hyman DeWitt confirms that the book in question was actually Castle ... (573)

You'd have to read her book yourself to understand exactly how this works, but again and again some precious conjecture of Franklin's (such as that Shirley Jackson was "raped" during her first sexual encounter with her future husband Stanley - substantiated by such clues as a "seemingly half in jest" reference in a letter, the words "He forced me God help me" in an (undated) notebook entry - but mainly by analogy with a famously ambiguous rape / seduction scene in the novel Hangsaman (p.156)) must be defended against any other possible interpretation. Particularly (it is implied) against the biased evidence of "interviews" - even though one would have thought the equally ambiguous evidence of random "spiral notebooks" with scraps of scenes and personal reflections written in them at various times was at least equally fallible.

In short, if Oppenheimer thinks it, it must be wrong. These refutations - there are no positive references of any kind to her work in this immense body of notes - are substantiated by such strong indicators as "I believe" ... "I was unable to confirm it independently" ... or opposing accounts in further interviews conducted by Franklin herself.

This is not to say that Franklin is necessarily incorrect in suggesting these revisions to the biographical record established by Oppenheimer. True, they seem a little carping and nit-picky in context, but perhaps that's because Oppenheimer did a truly shocking job in the first place. Did she?

I was glad to see, in looking through some of the reviews of Franklin's book, that I was not the only one to have detected this curious strategy of rhetorical emphasis through exclusion. Here's a passage from Charles McGrath's - basically positive - write-up in the NY Times:

The story of Jackson’s sad and difficult career is told with more vividness and in some ways with more intimacy in an earlier biography, Judy Oppenheimer’s Private Demons, which came out in 1988, and which Franklin, though a careful researcher and fastidious about sources, never mentions in the text. But Oppenheimer is a journalist, not a critic, and her book, based largely on interviews with Jackson’s family and friends, is interested more in the life than the work. The value of Franklin’s book, which benefited from access to archives unavailable to Oppenheimer, is its thoroughness and the way she traces Jackson’s evolution as an artist, sensibly pointing out what’s autobiographical and what isn’t.That seems like fair comment to me. It's a while since I read Oppenheimer's book - though I'd certainly be curious to reread it now, in the dubious light of Franklin's disdain. I do recall that it left me feeling far more depressed than Franklin's: the tragedy of SJ's life seemed more starkly outlined in it. McGrath goes on to define more closely the differences between the two books:

Franklin, more than Oppenheimer, wants to play down the chaos of Jackson’s life, and even suggests that the hurtling back and forth between cooking and cleaning and stolen sessions at her desk may have been as enabling as it was burdensome. Until it wasn’t. Always a heavy drinker and smoker, Jackson, while trying to lose weight, became dependent on pills of every sort, uppers and downers. Her mood swings became more extreme, and in 1963 she suffered a full-fledged breakdown, during which she was not only unable to write, she could barely leave her room. After seeking psychiatric help, she seemed to be recovering, and was happily working again, though also preoccupied with the idea of leaving Hyman and creating a new home somewhere. Then, on the sultry afternoon of Aug. 8, 1965, she had a heart attack and died in her sleep. She was only 48. At the time she was working in what she called “a new style,” on a novel that she hoped would be “a funny book. a happy book.” But her last published story, which came out four months later, was about a solitary New England woman who sent off nightly letters describing the terrible secrets of her neighbors.That's a very sensible summation, I think. Certainly Franklin has a nice convenient villain in the drunken philanderer Stanley, and - I suspect largely imaginary - break for freedom and self-fulfilment on Jackson's part all ready to kick into action on the day that she died.

Her Shirley Jackson is a feminist heroine, not the bedraggled victim of Oppenheimer's narrative. At which point, I feel, the story begins to get stranger. How many Shirley Jackson stories and novels hinge on the relationship between two women: one of them (generally) somewhat fey and indecisive, the other more brusque and business-like?

Judy Oppenheimer

House-bound Constance and roving Merricat, the two sisters in her last completed book, We Have Always Lived in the Castle, are perhaps the most harmonious instance - but Theo and Eleanor in The Haunting of Hill House also have a sexually charged relationship which ends in the former rejecting the latter, and the latter taking her life in response.

Then there's the young college student Natalie in Hangsaman (possibly traumatised by the repressed memory of a rape - we are never told for certain), haunted by her "daemon lover" Tony - who is clearly female, despite Jackson's attempts to evade the issue by claiming that a creation of the mind must be without clear sexual identity. Franklin sees this book as "unmistakably a document of Jackson's rage at her husband" (p.297). I'd say there was nothing "unmistakable" about it - except that Franklin's account of the book is clearly fuelled by her own rage at Jackson's uncaring husband.

Ruth Franklin

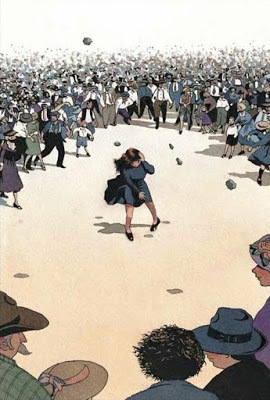

On and on it goes: one might say, in fact, that this is Jackson's great subject: the various subtle and complex ways women can find to torment one another in the guise of friendship and support. One of the characters (Natalie, Eleanor - even Tessie Hutchinson in her most famous story, "The Lottery") is generally clearly identifiable with Jackson herself (or at least with some aspect of her). The other is some kind of aggressor. But which one is Franklin to Oppenheimer?

She'd like to see herself, clearly, as the Jackson figure: a sensitive critic capable of resurrecting the "true" inner meanings of her extensive oeuvre - as opposed to the more superficial and "journalistic" Oppenheimer. The unscrupulous way in which she has attempted literally to write Oppenheimer out of the record: refute each of her conjectures, pour scorn on her interview-based rather than archival methodology, begins to sound uncomfortably bullying after a while.

In the end, I'm afraid, it's Judy we see collapsing under the weight of all the stones that have been sent flying at her; Judy who saw "The Lottery" as a straightforward parable of anti-semitism - as Jackson herself had stated (quoted on p.234) - Ruth who wants to record that as simply one of many conjectures and possibilities.

"If you live in a glass house ..." would be my final comment on this rather unfortunate attempt by Franklin to "bury" her opponent. Her book is well researched and interesting to read. It also contains the normal errors which can hardly be avoided in an enterprise of this scope (despite the massive number of collaborators, fact-checkers and general well-wishers listed at the end of this book they've collectively edited so "impeccably" (p.583)).

Who, for instance, is this "Arthur L. Kroeber" identified on p.232 as the father of the "novelist Ursula K. Le Guin," who wrote in to question Jackson's "motivations" in composing "The Lottery." He couldn't be the colossally famous Anthropologist Alfred L. Kroeber, could he? A small slip, but there are many others. And - given his eminence in the field - it is almost the equivalent of identifying a certain famous physicist as Arthur Einstein.

I could list many more such slips, but the point I wish to make is really very simple. Scholarship is a collaborative enterprise. Trying to imply that your own work so completely supersedes the efforts of a previous researcher - particularly the author of a pioneering biography of so important a figure as Jackson - is childish in the extreme. There were people (many people, I would suggest) who were available to be talked to in 1988 who are no longer with us in 2016. Ruth Franklin's own source notes show how heavy her dependence on Judy Oppenheimer's work has had to be.

What strange maggot of pique (or hubris) led Franklin to try to exclude Oppenheimer from her text? Did the latter poison her dog? Speak slightingly of her in public? Refuse to meet her, or to lend her some research materials? I'll conclude with some of Franklin's own words, her eloquent description of Jackson's own sound recording of "The Lottery":

Like the pointed collar around the throat of the dog Lady in "The Renegade," the recording cuts off abruptly before her voice has a chance to die out, making the last line sound like a question: And then they were upon her? The irony is audible. they have been upon her all along (p.247)

Yan Nascimbene: The Lottery

•

Here's a list of my own Shirley Jackson collection. As you can see, I buy each new book as it comes out, hoping somehow to come closer to the figure in her carpet, to understand better this strangely fascinating - perhaps because so disturbing - genius of the post-Atomic era:

Shirley Jackson (1916-1965)

Jackson, Shirley. The Road through the Wall. 1948. Foreword by Ruth Franklin. Penguin Classics. New York: Penguin, 2013.

Jackson, Shirley. The Lottery: Adventures of the Daemon Lover. 1949. London: Robinson Publishing, 1988.

Jackson, Shirley. Hangsaman. 1951. Foreword by Francine Prose. Penguin Classics. New York: Penguin, 2013.

Jackson, Shirley. The Sundial. 1958. Foreword by Victor LaValle. Penguin Classics. New York: Penguin, 2014.

Jackson, Shirley. The Haunting of Hill House. 1959. New York: Penguin, 1984.

Jackson, Shirley. We Have Always Lived in the Castle. 1962. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1984.

Hyman, Stanley Edgar, ed. The Magic of Shirley Jackson: The Bird’s Nest / Life among the Savages / Raising Demons &c. 1954, 1953, 1956. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1966.

Jackson, Shirley. Come Along with Me. Ed. Stanley Edgar Hyman. 1966. New York: Penguin, 1995.

Jackson, Shirley. Just an Ordinary Day: Part of a Novel, Sixteen Stories, and Three Lectures. Ed. Laurence Jackson Hyman & Sarah Hyman Stewart. 1997. Bantam Books. New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc., 1998.

Jackson, Shirley. Novels and Stories: The Lottery / The Haunting of Hill House / We Have Always Lived in the Castle / Other Stories and Sketches. Ed. Joyce Carol Oates. The Library of America, 204. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 2010.

Jackson, Shirley. Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings. Introduction by Ruth Franklin. Ed. Laurence Jackson Hyman & Sarah Hyman DeWitt. New York: Random House, 2015.

Oppenheimer, Judy. Private Demons: The Life of Shirley Jackson. 1988. New York: Fawcett Columbine, 1989.

Franklin, Ruth. Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life. liveright Publishing Corporation. New York: W.W.Norton & Company, 2016.

Shirley Jackson

Published on November 10, 2016 12:44

October 29, 2016

The President of the Philippines

President Rodrigo Duterte (the two-way: 28/10/16)

The President of the Philippines

told us his vision

last night

on the evening news

he was in a plane

flying back from Japan

when he heard a voice

who are you?

he said

it was God

I want you to stop

using bad language

said God

so no more slang

no more cuss words

you could see the reporters

wanted to laugh

at first

but they sobered up fast

that morning ten men

were shot dead in the street

the mayor of a town

and all his staff

involved in the drug trade

they said

no cuss words now

the doors are open

something that used to live

out in the cold

is shouldering in

•

New York Times (28/10/16)

Published on October 29, 2016 13:02

October 18, 2016

Two Versions of Mawson

David Day: Flaws in the Ice: In Search of Douglas Mawson (2013)

For years I've been encouraging my travel writing students to study two different versions of Douglas Mawson's classic survival yarn from his 1912 Antarctic expedition. On the one hand, there are two chapters from The Home of the Blizzard (1915), as reprinted for a popular account of his journey in 1930; on the other hand, there are his original diaries, edited for publication in 1988:

Mawson, Douglas. Mawson’s Antarctic Diaries. Ed. Fred Jacka & Eleanor Jacka. 1988. North Sydney: Susan Haynes / Allen & Unwin, 1991. 127-29, 147-48, 150-51, 157-59, 170-72 & 174.Mawson, Douglas. The Home of the Blizzard: The Story of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition, 1911-1914. 1915. Abridged Popular Edition, 1930. Adelaide: Wakefield Press, 1996. 158-203.

I was therefore interested recently to come across a new book about Mawson by David Day, author of the fascinating (and, indeed, truly groundbreaking) Antarctica: A Biography (2012). He'd expressed a few doubts about the veracity of Mawson's account in his earlier book, but given it was largely devoted to debunking the various masks behind which sheer naked greed for territorial acquisition were lurking on virtually all Antarctic expeditions old and new, I have to say that they didn't really seize my attention.

Now, however, he's committed himself to a full-scale hatchet job on Mawson, whom he clearly loathes with a passion, in the grand tradition of Roland Huntford's magisterial deconstruction of the "Scott of the Antarctic" legend in his Scott and Amundsen (1979).

In a sense, it's not a particularly difficult task. In his excellent and very balanced review of Day's book in Inside Story, "Debunking Mawson," Tom Griffiths acknowledges that:

All of Mawson’s well-known weaknesses are probed at length – his ambition, selfishness, coldness, competitiveness, meanness, lack of compassion and humour, propensity to dither, and other “flaws” in his icy character.Yes, precisely. I doubt that anyone who has studied Mawson - or even just read his books and diary - was ever tempted to think of him as a nice guy. Scott certainly had charm, though he mostly chose to use it only on his superiors and those he was cajoling to do something for him. Shackleton, too, inspired a kind of love in most of those who encountered him (though he too had his bitter enemies). Mawson was a little more like the emotionally reserved Amundsen, it seems: though he wholly lacked the latter's immense expertise and attention to detail when it came to the mechanics of organizing an expedition.

Was the picture quite as black as Day has painted it, though? A recent book by Karyn Maguire Bradford called The Crevasse: A Critical Response to "Flaws In The Ice" (2015) argues otherwise. Tom Griffiths also points out a couple of respects in which Day's book seems to weight the balance unduly against Mawson:

As revealed in his general history of Antarctica, David Day continues to lack any interest in, or curiosity about, science. This political historian of empire, who casts a perceptive and tenacious eye on the politics of polar annexation, can only ever see science with cynicism. It is for “show”; it “acts as a cover”; it “buttresses scientific credentials”; it is always strategic, self-serving and “disguising” something else ... With such a view, Day is destined to be blind to Mawson’s core motivation, and he is unable to share the wonder and intellectual excitement that drew – and still draws – many expeditioners to Antarctica.Quite so. "Science" is only ever mentioned with a sneer in Day's book, except where it assists him in pointing out how more "successful" both physically and scientifically the other expeditions Mawson sent out from his main base were than his own (scarcely surprising, since his became a desperate struggle for life, while theirs were merely intensely uncomfortable and difficult).

It also seems rather hypocritical of Day to spend so much time sniffing around the bedsheets to determine whether or not Mawson really slept with Scott's widow Kathleen. The same suspicions surround her relations with Fridtjof Nansen, but it's hard to see why it hasn't been allowed to blacken his reputation (though it undoubtedly calls his good judgment into question a little), while it should be so damning to Mawson's? Day is forced to resort to such phony rhetorical measures as balancing their trysts against the progress of the war itself:

That Sunday, as the relentless slaughter on the Somme continued, [Kathleen] went to Kensington Gardens with Peter [her son] to collect caterpillars, before spending a 'very delightful' time with Mawson in a row boat, and 'got home very late'. It wasn't warm enough for such activities, wrote Kathleen, but it was 'otherwise very delightful'. [272]The implication is that they had sex in the row boat ("supine on the floor of a narrow canoe"), though it's hard to see how one can be sure at this distance in time. Day has earlier quoted the statement (echoed by so many contemporary writers: Proust and T. S. Eliot among them) by Kathleen's "biographer and granddaughter Louise Young [that] ... the 'war seemed to send everyone if not sex mad, then love mad, passionate friendship mad, waste-no-time mad'" [269] "Doubtless," he acknowledges somewhat reluctantly, "it was life-affirming amidst the death and despair of a war that was killing millions". Now, however, he lets his real feelings show:

Mawson may have dropped by to show off his ... officer's uniform ... He could hardly confess that he'd spent the war years relaxing on the beach and dancing the nights away at London clubs while a million men were being slaughtered on the Somme. [272]This seems completely gratuitous. To hear Day trumpeting these John Bull-ish clichés ("What did you do in the Great War, Daddy?) a hundred years on is grotesque in the extreme. He tallies the various members of the Mawson expedition who managed to get themselves wounded or killed in the years that followed with almost the same smug satisfaction as some dyspeptic major in a Siegfried Sassoon poem.

WWI poster (1915)

James Joyce had a good answer for that question (or at any rate Tom Stoppard's play Travesties attributes one to him): "I wrote Ulysses. What did you do?"

The more serious charges against Mawson stem mainly from Day's analysis of his famous sledge-journey, after losing one of his two companions (together with the sledge he was guiding) in a crevasse.

You'll be unsurprised when I mention that Day seriously suggests that the accident was largely Mawson's fault because he hadn't told Ninnis that he might be in less danger riding the sledge than walking beside it, and speculates as follows about its cause:

Whether the bridge was already weakened by Mawson's sledge crossing it obliquely, or whether it was just the weight of Ninnis that made the critical difference, cannot be known. [151]In this and other passages, it's clear that the question, for Day, has shifted from "Did Mawson play any significant role in causing Ninnis's accident?" to "Which of Mawson's actions were most crucial in causing Ninnis's accident?" His guilt and complicity in everything that went wrong is simply assumed (albeit with much logic-chopping and admission of gaps in the existing testimony which have not permitted him to prove conclusively this preset conclusion that Mawson was driven by self-interest and folly at this, as at every other moment of his life ...)

Why did Mawson choose to go back by the inland route rather than along the coast? Why did Mawson ration the food so severely on the first part of the journey? Why did his remaining companion, Mertz, die on the way while Mawson survived? All of these questions have now been answered by Day's magical powers of intuition (one of the oddities of his book is that he writes as if he is the first ever to consider the matter: as if his really were the virgin footprints in the snow he'd originally envisaged for his own travel narrative).

The coastal route would have had many advantages, but Mawson didn't choose it because it would have undermined his priority as an explorer (Atkinson's party had already passed that way). The reasons Mawson himself gives: the possiblity of the sea-ice breaking, the prevalence of difficult crevasses, are so much flummery. Day knows that because ... well, for no reason really. As he admits in his preface, he'd hoped to land on Antarctica and do some travelling himself, but his ship couldn't land because of the pack-ice. He did get some nice photos of icebergs out in the bay, though. It certainly isn't his own personal experience of the conditions which enables him to refute Mawson so readily, then.

Why did Mawson cut back on the rations? Because there wasn't enough food on their one remaining sledge to get the two of the back alive without a great deal of luck. That's admitted by everyone. Where Day leads the pack is in suggesting that Mawson deliberately starved Mertz to death by giving him only lean meat while Mawson himself was scarfing down the heavy, fat-laden food they both needed for survival.

The trouble is that no-one knew about these dietary effects of lean meat at the time (a book documenting the fact by "the polar explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson" was published in 1913, though Day acknowledges that "Mawson and Mertz had no way of knowing this" [164]). So how precisely Mawson managed this cunning and systematic murder of his companion by using a dietary sleight-of-hand still controversial a hundred years later seems a little obscure. It does mean that Day isn't forced to major on the old accusation of cannibalism, though. He doesn't need to. However, it would go against the grain to let the old man off too easily:

His denial is not surprising. There is no heroism to be had in cannibalism. His vigorous denial has been acccepted by historians, who argue that it would have contravened Mawson's values and that, anyway, he had no need to do it, once Mertz was dead and all his intended rations were available for Mawson's consumption. [200]I have a countercharge to make. I believe that David Day himself committed cannibalism (like Conrad's "Falk") during his repeated attempts to reach the shore of Antarctica and flesh out [pun intended] his absurd farrago of a book. If he denies it, that's hardly surprising. Cannibalism is not a good look for historians and science writers generally: it tends to alienate the buying public (though, on the plus side, it can make your appearances on TV talkshows more lively). It's true he didn't need to: there was food on the ship. But can we be sure that there was enough food? The verdict must remain unproven. If Day feels he can prove that he never did it, I'll be happy to look over his evidence. I remain unconvinced, though.

You see the point? This kind of "When did you stop beating your wife?" stuff quickly becomes infectious. If you only have one source of information, then at a certain point you do have to admit that relentless speculation about - not to mention shitting all over - that narrative will only get you a limited way. And yet, it seems that - besides a lot of nasty remarks by a strangely volatile and childish fellow called Atkinson who also kept a diary of the expedition - innuendo is all Day really has: not a great deal to guarantee a book contract.

Is there no alternative to all this? Are we forced to accept either Mawson's own hero narrative or Day's relentless put-down? Well, strangely enough, there is. It's mentioned in Day's bibliography, but (curiously) not referred to in his text, which also fails to acknowledge much other earlier scholarship on the matter, as Tom Griffiths remarks in his review:

Although Day draws on the work of many historians who have studied Mawson and the AAE – in particular Philip Ayres, Peter FitzSimons, Brigid Hains, Elizabeth Leane, Beau Riffenburgh and Heather Rossiter – he does not name them in the text or engage explicitly with their scholarship. They are referred to as “other historians” or “other writers,” generally dismissively.I refer, of course, to Tim Jarvis.

•

Tim Jarvis: Mawson: Life and Death in Antarctica (2008)]

In 2007 "Australian Adventurer" Tim Jarvis set out to retrace "Mawson's gruelling experience." As the blurb to his eventual video (it was also released as a book) remarks:

having been almost killed during his own solo trek to the South Pole in 1999, [Jarvis] confronts the deadly ice again - as Mawson did, with similar meagre rations and primitive clothing and equipment."Whether or not one agrees that it's "a bold and unprecedented historical experiment that will provide clues to what happened to Mawson physically - and mentally - as a man hanging on the precipice of life and death," one must surely acknowledge that it's an interesting thing to attempt? And, one would have thought, an enterprise quite like Day's original plan:

to travel in the wake of Mawson's 1911 expedition to Antarctica, so I could visit the hut in which he and other members of the expedition had sheltered for nearly two years, and look out at the windswept vista of ice and snow that had beckoned them into the unknown. [1]"However," Day confesses, "it was not to be."

Reading that passage a little more carefully, though, one realises that for all his talk about composing a book "part travelogue and part history," Day was actually just planning to "look out" of the hut. There's no mention of actually walking in Mawson's footsteps. Why should he bother, anyway? Tim Jarvis had already done the thing so comprehensively that any such efforts would be largely wasted.

The problem, of course, is that mentioning Jarvis at all might risk reminding readers that Day is really just one more desk-bound scholar treading the well-worn steps of so many other archive hounds of the past. Griffiths documents thoroughly Day's attempts to imply a kind of conspiracy of silence surrounding the documentation of Mawson's expedition: his claims to have "uncovered" this or that new source:

Much of the evidence of the expedition, claims Day, “has been hidden away for the last century” and “includes the diaries of Archibald McLean, Robert Bage, Frank Stillwell, John Hunter, Charles Harrisson, and several others.” But the diaries of these men have been available for decades in public libraries and archives and have been studied intensely by many people, including those “other historians.” How strange that a historical scholar should regard the carefully preserved and curated collections of public institutions, long available for research, as “hidden away.” What Day means is that many of those diaries have only recently, in these centenary years of the expedition, been edited for publication.The other unfortunate fact about Jarvis is that this "adventurer" came to conclusions precisely opposite to those of Day himself on most of the significant questions surrounding Mawson's journey. What Griffiths refers to politely as Day's "confidently judgemental conclusions" on these matters can therefore be in no way helped by Jarvis's reenactment of the trip, and might actually be undermined by them. Best not to mention him, then. I'm an Academic myself: I know how that game works: the game of "accidental" omission.

That's not to say that there's anything flawless or forensic about Jarvis's investigation. It is, as he admits himself, a fairly rough and ready affair. Where he comes off way ahead of Day, though, is in his willingness to discuss his methods and debate the nature of his results up front.

I can't claim myself to have noted any particular pro-Mawson bias in his approach, though there may be a certain man-of-action solidarity there as against desk-wallahs in general. I couldn't say. If it's there it's pretty muted, unlike (say) the strident efforts to defend "the defamed dead" by Sir Ranulph Fiennes in his anti-Huntford Captain Scott biography (2003).

Where Day is particularly cock-sure is in his assertion that he has "solved" the mystery of Mertz's death. Rather than scurvy caused by vitamin C deficiencies in their diet, or the previously suggested vitamin A poisoning from the livers of the dogs they were eating, they were killed by the lack of fat in their diet:

Mawson couldn't have known it at the time, but it wasn't the lack of food that killed Mertz so quickly, rather it was the type of food they both were eating - particularly the scrawny dog meat with its almost total absence of fat, which caused them to suffer protein poisoning. [197]Nice to have that cleared up. Lest we should remain in any doubt on the matter, the very first note in his book reminds us: "It is often claimed that Xavier Mertz died from an excess of Vitamin A, after eating too many dog livers. It was later suggested that starvation was the more likely cause of his death. Both claims are wrong." (281) The fact that the two articles which argue these alternatives were published, respectively, in the British Medical Journal and the Medical Journal of Australia, and were presumably peer-edited by the medical professionals overseeing both journals, is neither here nor there. Day has cracked the case!

Of course, being a doctor himself, he'll be in a good position to weigh up all these competing claims from the scanty documentation surrounding the trip: the hints in the diaries as to who ate more of what. But just a second - what is his medical expertise? None, that's what. He started off studying accountancy ("in which he performed poorly due [to] his political activity that included protesting against Australia's involvement in the Vietnam War"), according to his wikipedia page, then switched to History and Political Science, in which he did better.

Jarvis was still running with the Vitamin A deficiency hypothesis when he made his documentary, in 2007, but at least he doesn't claim to know. If Day could only admit the faintest shadow of a doubt about his confident assertions, one might find his book more persuasive. As it is, even if he's right about his "protein poisoning" theory, how on earth could it possibly be proved?

As for the famous incident near the end of his one-man journey where Mawson (according to him) hoisted himself out of a precipice, Jarvis's attempts to reenact it proved quite unavailing, despite the fact that he was in substantially better shape than Mawson was at that stage of his ordeal (Jarvis wass prepared to starve himself, but not to poison himself, in the name of complete verisimilitude).

Here, I think, Day's reasoning is more cogent. He argues that rather than falling fourteen feet, Mawson may have fallen about seven, which makes his feat of strength far more feasible. Agreeing as it does with Jarvis's reenactment, this is one of the few occasions where Day's relentless scrutiny seems to have produced results. The same point is, however, made (at rather less length) in his far better - possibly because it was better edited - Antarctica: A Biography.

So, should we pull down the statues and throw away all our busts of Mawson: stop trumpeting him as the closest thing we have to an authentic Antipodean polar hero? Probably, yes. But then Mawson has always seemed a far more equivocal figure than his "heroic age" contemporaries. A flawed hero, then, but still a hero. His failure to emote all over the page in his stoic Antarctic diaries is one of the reasons they remain such compelling reading today. All Day's efforts to debunk and second-guess Mawson leave us more curious about him than his subject. What kind of a person would dedicate his life to such an avalanche of petty spite and hatred?

The comparison with Roland Huntford is, I think, quite unjustified. Huntford has never been afraid to give praise where it's due. His portraits of Amundsen, Shackleton and Nansen do full justice to the darker sides of their character, while still attempting to account for the charisma they continue to project, so many years later. True, Huntford sees few merits in Scott, but more of his blame is reserved for Sir Clements Markham and the other irresponsible bureaucrats who "pushed" him than for the hapless, demon-driven R. F. Scott himself.

Perhaps David Day's next work should be an autobiography. "What huge imago made / A psychopathic god?" as Auden once asked. Just why does he feel this need to denigrate poor Mawson, to scoff and sneer at and second-guess a man trapped in a coffin-shaped tent, his comrades dead, the snow falling, with a far less than fifty percent chance of survival? Could it be something as simple as jealousy?

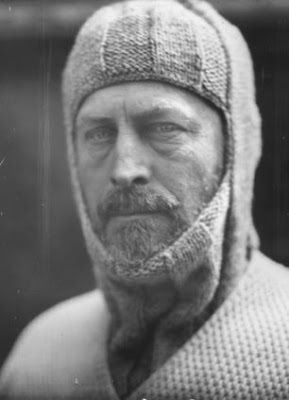

Douglas Mawson (2013)

Published on October 18, 2016 16:14

October 15, 2016

10 Greatest Sci-Fi Movies of All Time

Space

I was thinking about this the other day, and it occurred to me that there were only a very few movies which have reached critical mass in this genre: movies every detail of which is significant not only to scholars but in popular culture as well.

It's hard to rank them in order of importance, given that it's their individuality which constitutes their distinctiveness, in every case. The first few pretty much select themselves, of course. Some of the later ones may inspire a bit more controversy, along with my decision to include two each by Andrei Tarkovsky and Ridley Scott:

Metropolis

Metropolis , dir. Fritz Lang, writ. Fritz Lang & Thea von Harbou - with Alfred Abel, Gustav Fröhlich, Rudolf Klein-Rogge & Brigitte Helm - (Germany, 1927)

I recently rewatched Metropolis in the new, 2010, version, which includes a lot of original footage from a version found in film archive in Argentina. It was quite a revelation! For the first time the plot really seemed to make sense, and all the subsidiary characters were able to take their proper place in the drama.

Mind you, I don't think I can ever recover the thrill I felt when I first watched Giorgio Moroder's disco version at the Auckland Film Festival in 1984. The completely over-the-top nature of the music seemed to fit perfectly with the exaggerated gestures of the actors, and the clever use of tinted prints didn't hurt, either.

One might argue, in fact, that the mark of a great SF movie is that one has to own it in various different versions. I now have the beautifully restored 2002 version, the 2010 version, and (for nostalgia's sake) the Giorgio Moroder version. I have to say that for me it works on almost every level: visually, emotionally, and ideologically.

•

2001: A Space Odyssey

2001: A Space Odyssey , dir. Stanley Kubrick, writ. Stanley Kubrick & Arthur C. Clarke - with Keir Dullea & Gary Lockwood - (USA, 1968)

I recently rewatched 2001, too. This is possibly only the third time I've seen it. The first time, when I was still a small child, was absolutely awe-inspiring. The sheer realism of the space-stations and spaceships enthralled me, and the philosophical complexity of the action went far beyond anything I'd ever seen on the screen before. It immediately became my benchmark for Science Fiction in general, and I pored eagerly over both Arthur C. Clarke's novel and his short-story collection The Lost Worlds of 2001 till I felt I in some way understood it.

The second time was in the 1980s, in a Kubrick retrospective at the Filmhouse in Edinburgh. It seemed a lot weirder the second time round, and the ape men looked more obviously staged in front of a painted backdrop. It was a bit of a disappointment, actually.

This latest time was, I must say, very enjoyable. Of course it shows its age, but almost fifty years on it has the distinct patina of a classic. It looks far better to me now than it did in the eighties. The fact that it still remains unsurpassed in so many ways allows one to explore its conundrums with more pleasure and less anxiety. It stands, I suppose, as the War and Peace of SF cinema.

•

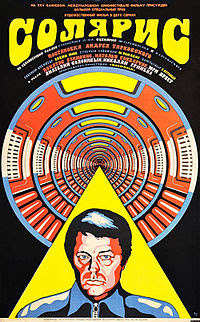

Solaris

Solaris , dir. Andrei Tarkovsky, writ. Fridrikh Gorenshtein & Andrei Tarkovsky (Based on the novel by Stanisław Lem) - with Donatas Banionis, Natalya Bondarchuk, Jüri Järvet, Vladislav Dvorzhetsky, Nikolai Grinko & Anatoly Solonitsyn - (Russia, 1972)

Tarkovsky films can be a bit demanding on an audience's patience, which is one reason why watching them at home on your own TV can be an advantage. Taken in instalments, even experiencing Andrei Rublev seems far less of an ordeal.

Solaris has always been one of my favourites among his movies - and not just because I've read Stanislaw Lem's novel so many times. The two are so profoundly different that it's easier to think of them as entirely separate works. Lem's novel is more obviously satirical of Academic thinking in general, but with a zest and inventiveness which make it probably his most humane and approachable fiction. Tarkovsky's film, by contrast, is all about spirituality and soulfulness.

Suffice it to say, if you don't like long scenes of water moving over waterweed, and cameras tracking over paintings with the music of Bach's St. Matthew Passion in the background, then Solaris is not for you. You'll be missing a lot, though. This is possibly the single greatest exploration of the (so-called) "Android theme" in the history of SF cinema - its only possible rival in that respect is Blade Runner.

•

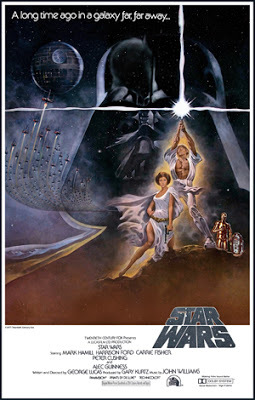

Star Wars

Star Wars , dir. George Lucas, writ. George Lucas - with Mark Hamill, Harrison Ford, Carrie Fisher, Peter Cushing & Alec Guinness - (USA, 1977)

This one really caused me some soul-searching. I just didn't like it when it first appeared - it seemed such a cheesy piece of space opera in comparison with the genuine awe produced by 2001. Over time I have, however, learned to admire certain aspects of it: the scenes on the desert planet are particularly effective, I feel.

One can't deny the influence it's had (though I'm not sure I'd see that as an unmixed blessing). Its successor, The Empire Strikes Back, was probably the most interesting and dramatic in the series to date, but since then it's mostly been downhill: the embarrassing Ewoks were succeeded by the nonsensical foolishness of the prequel trilogy, and it's hard to see the latest film in the franchise as much more than a clone of the first.

I felt that it would be unreasonable to exclude it altogether, though: even with the silly tinkering George Lucas has done to it since its first release, it remains a very watchable and entertaining movie, as long as you don't expect too much (and don't get caught up in poor Joseph Campbell's senile maunderings about how perfectly it embodies the Hero's Journey).

•

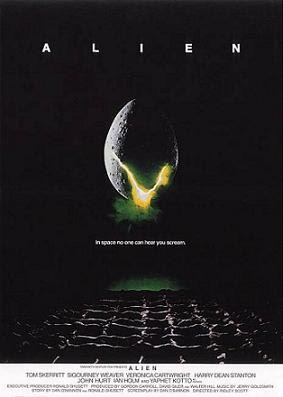

Space

Alien , dir. Ridley Scott, writ. Dan O'Bannon - with Tom Skerritt, Sigourney Weaver, Veronica Cartwright, Harry Dean Stanton, John Hurt, Ian Holm & Yaphet Kotto - (UK / USA, 1979)

No doubts about this one, though. It's still bloody frightening after all these years: more to the point, though, it has that air of existential menace, of a hostile and incomprehensible universe intruding on our little lives which is one of the marks of a genuine SF masterpiece.

Stephen King was very critical of the fact that, after scoring by choosing a gung-ho female protagonist for an action movie, this act of feminist empowerment is let down at the last minute by having her go back to save her cat, dressed only in skimpy underwear. I can see his point, but as a rabid cat-lover myself, I can't see anything unreasonable in her desire to save some other living creature from their wreck.

And as for the underwear, lighten up, dude! Who the hell cares? Maybe no-one wants to see you (or me) in our underwear, but that hardly applies to the young Sigourney Weaver. I suspect that Tabby might have been breathing down Big Steve's neck when he wrote that review, anyway. it sounds a little forced. The H. R. Giger sets are fantastic.

•

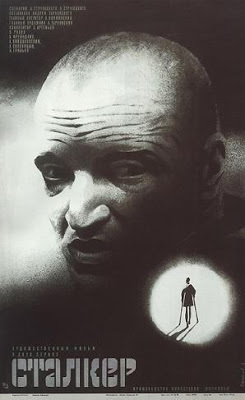

Stalker

Stalker , dir. Andrei Tarkovsky, writ. Arkadi & Boris Strugatsky (Based on their novel Roadside Picnic)- with Alexander Kaidanovsky, Anatoli Solonitsyn, Nikolai Grinko & Alisa Freindlich - (Russia, 1979)

Again, you do need a bit of patience to watch this one. It actually runs for only 161 minutes (2 and a half hours), but it seems like a lot more.

It's a profoundly beautiful and atmospheric work, however - for me, unquestionably Tarkovsky's masterpiece. Much as I love Solaris, there's a certain tinniness to those few special effects he had to put in here and there to persuade us - however tepidly - that the action was actually happening in space, and that can be a little distracting at times.

The advantage of Stalker is that Tarkovsky can use his favourite pieces of Russian countryside, but with the subtle alien dread of the unexpected. Anything can mean anything in this film, and the fastest way between two points is never a straight line.

•

Blade Runner

Blade Runner , dir. Ridley Scott, writ. Hampton Fancher & David Peoples (Based on the novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick) - with Harrison Ford, Rutger Hauer, Sean Young & Edward James Olmos - (USA, 1982)

So how many versions of this film are there? Well, there's the first-release version, with the voice-over which I liked at the time, but which I'm now prepared to accept is not really necessary to sustain Scott's final vision of the film. Then there's the (so-called) Director's Cut, without the voice-over, and with the strange little scene of the unicorn which leads us to question whether Deckard himself might not be a replicant. Then there's the real, restored Director's cut, with complex corrections of various perceived "flaws" in the original footage (such as the blue sky breaking through at the end of Roy Batty's final monologue). Then there's the pre-release version, without the happy ending or the voice-over, the one which was shown at a film festival in teh late eighties and thus inspired the re-release of the movie in the early nineties.

Phew! Actually, the only thing for it is to fork out for that collector's box-set, with all of them included. The unfortunate fact is that I still feel torn between the first two versions (I liked that happy ending), even though I gradually came to feel that the Director's cut was better. The new restored cut adds little of substance, I feel. The blue sky did break the frame, in a sense, but in a good way. it was as if, for a moment, there was relief from the oppressive world of the film. That relief is now denied us by a bunch of officious lab technicians.

What's certain is that this film - in any of its versions - is a masterpiece. It's up there with Metropolis and 2001 and may indeed be greater than either. It's the Citizen Kane of SF cinema, in fact.

•

Dune

Dune , dir. David Lynch, writ. David Lynch (Based on the novel by Frank Herbert) - with Francesca Annis, Linda Hunt, Kyle MacLachlan, Everett McGill, Kenneth McMillan, Siân Phillips, Jürgen Prochnow, Patrick Stewart, Sting, Max von Sydow & Sean Young - (USA, 1984)

I loved this film when I first saw it, though it did seem almost embarrassingly over the top in parts. I suppose the problem was that most of us knew that Ridley Scott had been fired from the project, and were resentful that we'd thus been denied another masterpiece like Alien or Blade Runner.

Over time, though, I learned to apologise for it less and celebrate it more. It's an intensely operatic movie, melodramatic and larger than life, with repeated leit-motifs like a Wagnerian score.

It may seem shocking to some to include it in this list, but I do feel that time has vindicated it. It remains just as vivid, strange and deeply - almost sentimentally - emotional as it did when it first appeared. The miniseries is good, too, but in a quite different way. At all costs avoid the extended, three-hour version of Lynch's film, however: most of the new footage would have been better left on the cutting-room floor. Far better to see it as it was first released, complete with the Brian Eno / Toto score!

•

Naked Lunch

Naked Lunch , dir. David Cronenberg, writ. David Cronenberg & Bill Strait (Based on the novel by William S. Burroughs) - with Peter Weller, Judy Davis, Ian Holm, Julian Sands & Roy Scheider - (Canada / UK / USA, 1991)

Again, I imagine this might be a controversial choice for some. Perhaps I am just a child of the 80s, unable to extricate myself stylistically (or ideologically) from that decade. I have mixed feelings about Cronenberg's films: some I like, some not. This one, however, entranced me when I first saw it, and has fascinated me ever since.

It's fair to say that it's in no way a dramatisation of Burroughs' book. Instead, it's a fantasia based on Burroughs' life, with various motifs from the book woven in. What can I say? It's just an incredibly clever film, which makes a low budget and tinny sets into an intrinsic part of the drama. If this doesn't scare you, nothing will.

It's not really a horror film, though. Burroughs' world is almost as bleak as Beckett's, but - like Beckett - a strange zany humour and unquenchable interest in things is still visible at the back of his devastated worlds.

•

Inception

Inception , dir. Christopher Nolan, writ. Christopher Nolan - with Leonardo DiCaprio, Ken Watanabe, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Marion Cotillard & Ellen Page - (USA, 2010)

Christopher Nolan is (for me) one of the greatest of contemporary film-makers: up there with Lars von Trier and Hayao Miyazaki.

True, some of his films are better than others, but that's probably a promising sign. Interstellar didn't really work, I felt, but when you start listing films such as Memento, The Prestige, and the Batman trilogy, you begin to realise the sheer scale of his achievement.

Inception is so infernally good that it takes some time to disentangle the fascination of the story from the spectacular nature of the cinematography. In a sense, it looks too good for one to realise at first how good it really is. In any case, it seems a good place to stop the list, though no doubt one could go on and on ad infinitum.

•

So there you go. I'm conscious of some massive omissions. None of the Star Trek films, for instance, even though the first of them is really quite an ambitious and interesting movie, and the second, The Wrath of Khan (1982), is a great piece of melodrama: "From Hell's heart I strike at thee, Kirk!" I actually think the first two remakes, with the new cast of Chris Pine, Zoe Saldana et al. are better films than any of the originals. It was with a certain pang of nostalgia that I left all of them out, however.

Another couple of favourites I would have loved to have included (and would have on a longer list, less dominated by the obvious classics) were Pitch Black (2000) - a lot more than just another Vin Diesel vehicle - and Serenity (2005), the film of the innovative SF TV series Firefly . They both look great, have fantastic casts, and a real slam-bang energy to them.

I'd have liked to put in The Quiet Earth (1985), too, and not just for patriotic reasons. It's still a great film, brilliantly adapted by Geoff Murphy from Craig Harrison's novel, and with a show-stopping performance by the late great Bruno Lawrence.

I'd also have liked to put in Lars von Trier's wonderfully moving Melancholia (2011), along with Duncan Jones' Moon (2009), Alfonso Cuarón's Gravity (2013), and one of Ridley Scott's most entertaining films to date, The Martian (2015).

You can't include everything, though, and time must have a stop. Which other masterworks do you think I've missed?

Paul Verhoeven, dir. Starship Troopers (1997)

Published on October 15, 2016 14:46

September 22, 2016

Leicester Kyle & Paul Celan: 2 Corrections

K. J. Walker: Powelliphanta augusta (2005)

Quite some time ago now (in April 2014), I published an article [“Paul Celan & Leicester Kyle: The Zone & the Plateau,” Ka Mate Ka Ora 13 (2014): 54-71] on New Zealand poet Leicester Kyle, attempting to link some of his attitudes towards place with similar ideas in the work of Paul Celan.

Some time later I received two emails which offered corrections to some of the information in the essay. I had (as I thought) arranged with the editor for portions of these to appear in the next issue of the journal, but given that has taken over two years to appear, I imagine these details must have got lost in translation.

In any case, it's perhaps better that I put them on record here instead. The above preamble is simply intended to explain why this process of correction has taken so long.

•

The first letter, from Dave Johnson, Leicester Kyle's brother-in-law, concerns the precise circumstances of Kyle's father’s suicide. The passage in my essay reads:

His father, a journalist with some literary ambitions (he worked with Allen Curnow on the Christchurch Press) came from a well-established Greymouth family, but found it difficult to adjust to life in the city. He committed suicide when Leicester was still in his teens. [60-61]Mr Johnson, in his email of 29th October 2014, makes these adjustments: “Cecil committed suicide (without meaning to) as he rang Helga [Leicester’s mother – JR] on the day of his death asking when she would be home. She was delayed by well over an hour and when she found him after he had swallowed his pills and binged it was too late to save him. Leicester was 29, not a teenager.”

He goes on to comment:

The snail Millertonii you mentioned is not the one from Mt. Augusta (now strip mined) I actually found the first specimen when we tramped up to the old Rainbow mine while botanising. Leicester thought the shell looked different and sent it off to Ch.Ch. It was eventually given the specific name Augusta.This refers to the passage in pp. 62-64 of my essay about the discovery of the rare “Millerton snail,” which I have unfortunately confused with another, even rarer snail discovered on Mt. Augusta.

K. J. Walker: Powelliphanta lignaria (1993)

•

Kath Walker (2011)

The second letter, received 9 April 2015, from Kath Walker of the Department of Conservation, has provided a good deal more detail on the distinction between these two snails:

I just thought I’d get in touch to clarify some confusion in your essay around the snail Leicester found at Millerton township, which we initially thought a newly discovered subspecies of the species Powelliphanta lignaria (we dubbed it Powelliphanta lignaria “Millertoni”) and the famous one which was found higher up on the Plateau on the Mt Augustus ridgeline (now described as Powelliphanta augusta). Your essay has them as one and the same but they are actually 2 separate very different entities, & they suffered different fates.While I hope that it’s true, as Kath Walker is kind enough to say, that this confusion between the two snails and their respective fates does not affect “the theme of [my] essay,” I am nevertheless very anxious to correct any misinformation I’ve unwittingly perpetrated.

I don’t think Leicester ever saw the famous snail, Powelliphanta augusta, whose only habitat high up on Mt Augustus ended up being mined by Solid Energy, with the snails being held in DoC coolstores, tho I certainly had him searching for it for me back in late 2003/early 2004.

Coincidentally, just as I was trying to find the Mt Augustus snail, Leicester contacted me regarding the much bigger snail he’d seen in the Millerton township. We (Dept of Conservation) ran an intensive programme of rat control around the colony of the Millerton snail (P. l. “millertoni”) for several years to protect it while we investigated its origins using genetics. Not surprisingly, given its very limited distribution, very close to human settlement, this Millerton snail turned out not to be something different after all, but rather a population of P. l. lignaria (found north of the Mokihinui River mouth) looking a bit odd as it had been founded from only 1 or 2 individuals artificially transferred there, presumably by a resident in Millerton’s heyday.

None of this changes the theme of your essay – but it would be good to untangle the MAPPs reserve story – in the immediate vicinity of Millerton, which still exists, along with its annoyingly translocated population of P. l. lignaria (biogeographic patterns are important to retain in nature), and the P. augusta story with its much more sombre ending.

I’ve spent a decade trying to protect the Great Buller Sandstone Plateaux and its inhabitants via Environment Court appeals & always felt that Leicester’s poems cut to the chase & were worth far more than all the careful scientific evidence I prepared (“It’s the loss. Not protest notes to the CEO, or grumpy barricades …“). I agree with your thesis – the only chance of protecting a resource rich place is if many people love it for its own sake, and Leicester’s poetry could help that. In the end I wondered if his poetry spoke more to those who already loved and knew the landscape, both the geographical and the political landscape of the Plateaux.

Both Paul Celan and Leicester Kyle were poets who were exceptionally careful to get their facts straight, and I would be doing no service to their memory if I didn’t make every effort to alter these details in my essay.

Mea culpa, then: please bear these facts in mind if you ever feel tempted to revisit the original essay!

J. Ross: Leicester Kyle (2000)

Published on September 22, 2016 16:12

August 26, 2016

Two Readings: Takapuna & Titirangi

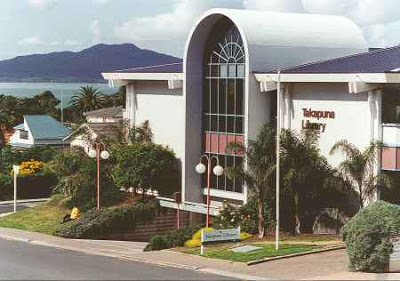

Takapuna Library

As part of the ongoing celebrations for National Poetry Day, please come and check this out (though it is, admittedly, a few days late):

Celebrating Poetry

When: Tuesday 30 August, 6pm - 7.30pm

Where: Takapuna Library, Level 1

Cost: Gold coin/donation

Come and join us as at our annual celebration of poetry with readings from Michael Giacon, Joy MacKenzie, Bronwyn Lloyd, Jack Ross and Stu Bagby as our MC.

Light refreshments will be served from 6pm, with the event starting at 6.30pm.

Booking recommended. Email helen.woodhouse@aucklandcouncil.govt.nz or phone 890 4903.

Photo: Maggie Hall (Wellington, Dec 2014)

•

Titirangi Library

And, assuming you don't have anything better to do on the weekend of the Going West Literary Festival (10-11/9/16):

Titirangi Poets

When: Saturday 10 September, 2pm - 3.45pm

Where: Titirangi Library

Featuring JACK ROSS and STU BAGBY

Jack Ross has been the managing editor of Poetry New Zealand since 2014. His publications to date include five poetry collections, three novels and three books of short fiction. He works as a Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing at Massey University's Albany Campus.

Stu Bagby has published both as an anthologist and a poet. His poetry has appeared in several collections and has been included in the Best of the Best New Zealand Poems and Essential New Zealand Poems. He hopes to have a new collection of poems ready for publication later this year.

Followed by a round robin where everyone is invited to read a poem, their own or anyone else's.

MC Piers Davies 5246 927 or piers@wwandd.co.nz for further information.

Photo: Maggie Hall (Wellington, Dec 2014)

Published on August 26, 2016 14:39

August 6, 2016

Post-Apocalyptic Fiction: An Interview by Karen Tay

The Pantograph Punch (2016)

Auckland writer Karen Tay who (according to her bio note) "reads far too much, obsesses about cats, and dreams of someday escaping this Freudian coil we live in," has just published a fascinating piece entitled "Writing the End of the World," about Post-Apocalyptic Fiction, on local arts and culture website The Pantograph Punch.

I guess one reason I enjoyed the piece was because I was one of the people she interviewed for it (together with Anna Smaill, author of The Chimes, and visiting Scottish author Louise Welsh). I don't think it's just that, though. It's a genuinely intriguing piece, which I highly recommend. It is, after all, a subject much in our minds at present, as the Trump Apocalypse looms.

Louise Welsh: The Plague Times, 2 (2015)

Karen is herself a very talented writer of fiction. I had the privilege of reading her novel Ice Flowers and assessing it for her Masters degree a few years ago, and wish very much that she'd succeeded in getting it into print so that I could recommend that to you, also. She tells me she's working on a second novel, though, so let's hope that that one gets published at some point in the near future.

Coming back to the article, though, Tay sees the genre as cyclic, conditioned by particular pressures of the time:

Each decade brings a unique set of challenges to humanity, but also another way for authors, the memory-keepers of society, to record our collective fears, anxieties and doubts about the future: to imagine both the destruction of the old, but also the beauty of the new rising out of death.She does not, however, see it as a particularly pessimistic form in itself: "Hope is the premise of most post-apocalyptic fiction. The clue lies in the prefix ‘post’ itself – the implication that there is something afterwards, other than the dark finality of the tomb."

Just as a taster for her piece, I thought I'd include here my answers to Karen's original questionnaire:

Anna Smaill: The Chimes (2015)

When do you think eschatological fiction, or more specifically, post-apocalyptic fiction, started becoming popular? Why?

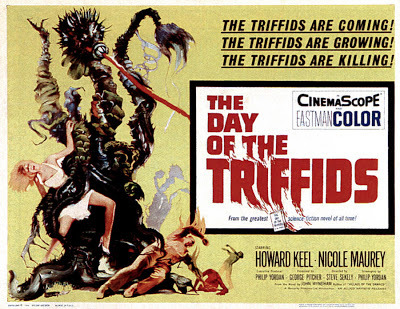

I suppose that the obvious point of origin is the atomic bomb blasts on Hiroshima and Nagasaki: after that, the Apocalypse could not but seem only too imminent. One can certainly point to earlier examples: Mary Shelley's The Last Man, Wagner's Götterdämmerung - but from the late 40s on various types of apocalypse began to dominate Sci-Fi, in particular (John Wyndham's The Day of the Triffids, George Stewart's Earth Abides, and so on and so forth).

John Wyndham: The Day of the Triffids (1951/ 1962)

From the late 1950s/early 1960s to about the late 1980s in particular, nuclear holocaust speculative fiction was an extremely popular subgenre. Why do you think this was?

Well, the Cold War is the simple answer. I remember one of my classmates at school telling me solemnly that there was simply no other subject to think about except nuclear disarmament - so likely did it seem to us, that we were almost literally counting down the days. You have to remember that it was the limited extent of the disaster at Chernobyl, rather than the event itself, that surprised us in those days.In nearly every piece of popular early (pre-2000s) post-apocalyptic/apocalyptic fiction, the hero/heroine turns out to be white. Any "coloured" characters often revert to stereotype - for example, the "wise old coloured woman" cliche like Mother Abagail in Stephen King's The Stand. What do you think about this "whitewashing" says about the genre? Do you think this has changed?

I think one might say that this was fairly typical of SF in general at that time. Even African American authors such as Samuel R. Delaney tended to soft-pedal the issue in his earlier fiction: sexuality was a more open subject for him than race. Delaney did write a classic essay in which he speculates that the hero of Heinlein's Starship Troopers is meant to be black, however. Careful examination of the text would leave that an open question for me, but Delaney does wonderful things with the mere possibility. (Paul Verhoeven's movie, of course, ignores the issue entirely in favour of his own preoccupations with Nazi aesthetics).A lot of post-apocalyptic fiction is in the form of Young Adult or New Adult fiction e.g The Hunger Games, Z for Zachariah, Tomorrow When the War Began, the Maze Runner series. Why do you think this is? Is there something about youth that predisposes them towards a fascination for death and destruction?

Yes, I think there is. Youthful readers are extremists, by definition. They want something grand and overarching, and are ready to be radical in their opinions. They lack the protective cushioning and inertia of older readers. That's one reason why genuinely revolutionary texts, such as Huckleberry Finn, say, or Catcher in the Rye, are so often aimed directly at a childish or adolescent audience.Cli-fi, or climate change fiction is another growing sub-genre of literature, for obvious reasons (climate change and global warming are very confronting realities that current and future generations of humanity are and will have to face). The most popular contemporary example is probably Margaret Atwood's Oryx and Crake series. Do you think this is a reflection of the times? If so, does this follow a historical pattern?

I edited a book of short stories by NZ writers called Myth of the 21st Century in which I and my co-editor, Tina Shaw, invited contributors to speculate what would be the dominant myths, or themes, or memes of the coming century. I expected a lot about climate change (both Tina and I wrote stories dominated by the notion), but it was interesting to me how little it figured in the other writers' visions. There's a wonderful early short story by Arthur C. Clarke in which the glaciers are returning to crush our cities, but for the most part there was a residual optimism in 20th Century SF writers which led them to postulate escape into the cosmos as the answer to climate change. Now, in our more down-beat times, we can no longer really believe such things. Hence movies such as The Day after Tomorrow and Snowpiercer and (the less successful) 2012. Whether there's a great deal of interest to say about it is another question: Waterworld is another example that springs to mind.

Kevin Reynolds, dir.: Waterworld (1995)

As a fan of the post-apocalyptic genre, many of my favourite novels and stories have at the heart of the tale, the struggle between good and evil, with love often winning in the day. Do you think post-apocalyptic fiction is merely another vehicle for moral fables? OR is it something else?

I think it's fundamentally an optimistic genre, in that it presupposes both the survival of the author (long enough to pen his or her screed, that is) and an audience - even if it's an alien one, such as the monkey couple who read the message in a bottle that constitutes Pierre Boulle's Monkey Planet (filmed as Planet of the Apes). I don't think there's anything wrong with moral fables, myself. What else do we have, after all, but attempts at mutual understanding? Whether that takes place in space, or in a nuclear wasteland, or in a busy city doesn't alter the fact that (as the song puts it) "the fundamental facts apply" ("As Time Goes By").Why are you drawn to the genre yourself?