Jack Ross's Blog, page 25

October 25, 2017

Michele Leggott: Vanishing Points Launch

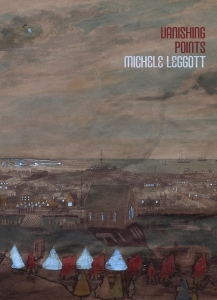

Michele Leggott: Vanishing Points (2017)

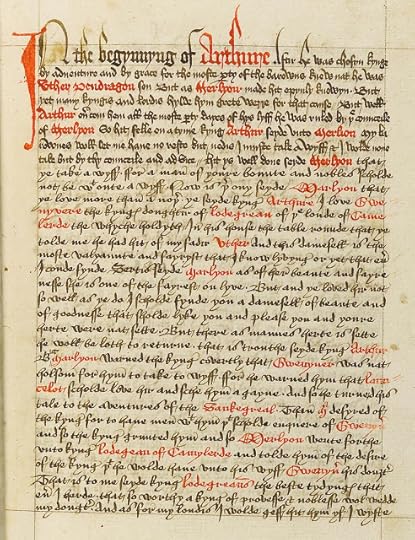

It’s an optical amusement, a punctured surface letting light pour through holes cut out of the picture. Moon, army tents and the windows of houses and St Mary’s church glow or flicker with luminance. Between them move women and children as well as soldiers. Steamers, a brig and a schooner ride on the moonlit sea. Part and not part of the scene is the artist’s son, who lies three days buried in the churchyard at the foot of the hill where his father sits sketching the arrival of imperial troops. Now walk away from the painting when it is lit up and see how light falls into the world on this side of the picture surface. Is this what the artist meant by his cut outs? Is this the meaning of every magic lantern slide?.

In all the excitement of Labour weekend, don’t miss the launch of Michele Leggot’s luminous new poetry collection on Tuesday evening!7–8.30pm, Tuesday 24 October 2017

Devonport Library, 2 Victoria Road, Devonport, Auckland

Koha appreciated.

We had an excellent time on Tuesday night. The Devonport Library Associates once again gave us a rousing welcome: Jan Mason and Paul Beechman gave the opening speeches, and Ian Free presented Michele and myself with some lovely bottles of bubbly. Sam Ellworthy was there to represent Auckland University Press, her publisher, and closed off the evening with a few words.

Tim Page did his usual brilliant job as sound-master, as well as creating a wonderful animation of the book's cover image, Edwin Harris's 1860 painting 'New Plymouth under Siege.' The original has little holes in it which look like twinkling lights when illuminated from the other side. Tim got us as close to that as one can imagine with his screen projection of this strange, haunting, rather Gothic work:

Edwin Harris: ‘New Plymouth under Siege – 40th Regiment, Marsland Hill, Taranaki 1860’ (3 August 1860)

My job was twofold: first to introduce Michele and her book, and secondly to interview her about it. it's always a bit difficult to make these setpiece 'conversations' sound at all spontaneous, but various people told me afterwards that they thought we'd carried it off.

Michele really didn't know what I was going to ask in advance (I hardly did myself), but she certainly had a lot to say in response. My idea was to try and anticipate what questions people might have on looking into the book, and to try to cover as many as possible of those in advance. Here we are in full cry:

photograph: Bronwyn Lloyd

Of course there was also a reading. Michele read four sections from the closing sequence, 'Figures in the Distance,' immediately after my launch speech. Here she is reading, with the help of her ipod:

photograph: Bronwyn Lloyd

I was in two minds whether or not to include the text of my speech. It's hard to recover the spontaneity of a live event, but as long as you bear in mind that it is written to be spoken, not read, I don't suppose there's any harm in it:

Well, needless to say, I felt very flattered when Michele Leggott asked me to launch her latest book of poems, Vanishing Points. Flattered and somewhat terrified. It’s true that I’ve been reading and collecting her work for well over 20 years, and I’ve been teaching it at Massey University for almost a decade now, but I still felt quite a weight of responsibility pressing down on my shoulders!

One thing that Michele’s poetry is not, is simple. It’s hard to take anything in it precisely at face value: what seems like (and is) a beautiful lyrical phrase may be a borrowing from an unsung local poet – a tangle of Latin names can be a reference to an obsolete star-chart with pinpricks for the various constellations.

The first time I reviewed one of her books, as far as I can see, in 1999, I ended by saying “the reading has only begun.” At the time, I suspect I was just looking for a good line to finish on, but there was a truth there I didn’t yet suspect. Certainly, I’ve been reading in that book, and all her others, ever since.

But how should we read this particular book? “Read! Just keep reading. Understanding comes of itself,” was the answer German poet Paul Celan gave to critics who called his work obscure or difficult. With that in mind, I’ve chosen two touchstones from the volume I’m sure you’re all holding in your hands, or (if not) are planning to purchase presently.

The first is a phrase from the American poet Emily Dickinson, referred to in the notes at the back of the book: “If ever you need to say something … tell it slant.” [123] The second is a quote from the great, blind Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges: “I made a decision. I said to myself: since I have lost the beloved world of appearances, I must create something else.” [35]

With these two phrases in mind, I’d like you to look at the cover of Michele’s book. It’s a painting of the just-landed Imperial troops, camped near New Plymouth in August 1860. The wonderful thing about it is the way the light of the campfires shines through the painting: little holes cut in the canvas designed to give the illusion of life and movement.

“War feels to me an oblique place,” wrote the reclusive New England poet Emily Dickinson to Thomas Wentworth Higginson in February 1863, at one of the darkest points of the American Civil War. Higginson, a militant Abolitionist, was the Colonel of the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, the first officially authorized black regiment in American history. He was, in short, a very important and admirable man in his own right. Perhaps it’s unfair of posterity to have largely forgotten him except as the recipient of these letters from one of America’s greatest poets.

New Zealand’s Land Wars of the 1860s may have been on a much smaller scale, but they were just as terrifying and devastating for the people of Taranaki – both Māori and Pakeha – in the early 1860s. In her sequence “The Fascicles,” Michele transforms a real distant relative into a poet in the Dickinson tradition. Just as Emily Dickinson left nearly 1800 poems behind her when she died in 1886, many collected in tidy sewn-up booklets or fascicles, so Dorcas (or Dorrie) Carrell “in Lyttelton, daughter of a soldier, wife of a gardener” [75] provides a pretext for “imagining a nineteenth-century woman writing on the outskirts of empire as bitter racial conflict erupts around her.” [123]

There’s an amazing corollary to this attempt to “Tell all the truth but tell it slant,” in Dickinson’s words. Having repurposed one of her family as a war poet, Michele was fortunate enough to discover the traces of a real poet, Emily Harris, the daughter of the Edwin Harris who painted the picture of Taranaki at war on the wall over there, whose collected works so far consist of copious letters and diaries, but also two very interesting poems. “Emily and her Sisters,” the seventh of the sequences collected here, tells certain aspects of that story.

It’s nothing but the strictest truth to say, then (as Michele does at the back of the book), that one should:walk away from the painting when it is lit up and see how light falls into the world on this side of the picture surface. Is this what the artist meant by his cut-outs? Is this the meaning of every magic lantern slide? [124]I despair of doing justice to the richness of this new collection of Michele’s – to my mind, her most daring and ambitious work since the NZ Book Award-winning DIA in 1994. There are eight sequences here, with a strong collective focus on the life and love-giving activities which go on alongside what Shakespeare calls in Othello “the big wars”: children, family, eating, painting, swimming. One of my favourites among them is the final sequence, “Figures in the Distance,” which offers a series of insights into the world of Michele’s guide-dog Olive – take a bow, Olive – amongst other family members, many of whom, I’m glad to see, have been able to come along here tonight.

This is a radiant, complex, yet very approachable book. It is, in its own way, I’m quite convinced, a masterpiece. We have a great poet among us. You’d be quite crazy to leave here tonight without a copy of Vanishing Points.

At this point, then, I’d like to hand over to Michele, who will read three pieces from the sequence “Figures in the Distance." After that the two of us will have a short conversation about the book, and I’ll try and ask, on your behalf, some of the questions I think you’d like to have answered about how it all connects and how the various parts of it came about.

photograph: Bronwyn Lloyd

Published on October 25, 2017 13:32

October 13, 2017

Dianne Firth: The 'Poetry and Place' Exhibition

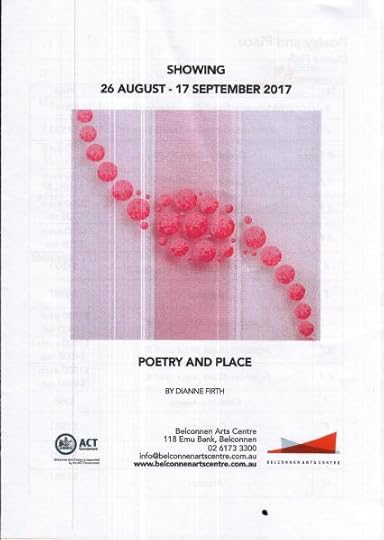

Dianne Firth: Poetry and Place (2017)

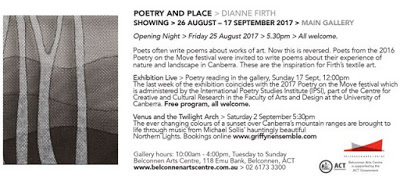

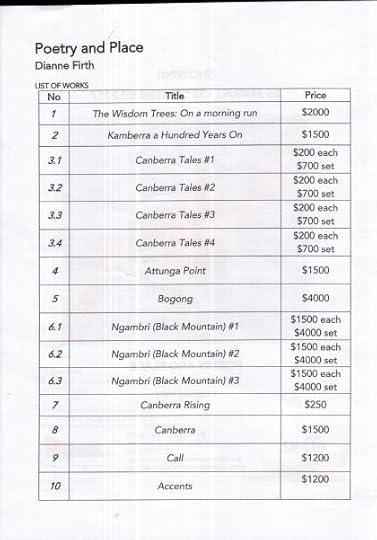

Poetry and Place

Belconnen Arts Centre

Canberra

26 August - 17 September 2017

Dianne Firth: Poetry and Place (2017)

So, a couple of days ago I received a very interesting email from textile artist Dianne Firth, in Australia. In it she said (among other things):

Dear Jack,I haven't yet received the catalogue - I'm looking forward to that very much - but I have managed to learn quite a lot about the exhibition by doing a bit of trawling around the internet.

At the 2016 Poetry on the Move festival, at Paul [Munden]'s request, you wrote a poem about Canberra. For the 2017 festival I created a textile work in response to that poem and I would like to send you a catalogue book from the resulting exhibition 'Poetry and Place'.

Could you please send me your mail address.

Regards,

Dianne

It's not as if this came as a complete surprise. I remember the original request, and doing quite a lot of scrabbling around to put together something which might be construed as a poem about the Canberra landscape (quite unfamiliar to me until my visit to the 2016 Poetry on the Move Festival, as one of the judges of the University of Canberra Vice-Chancellor's Poetry Prize).

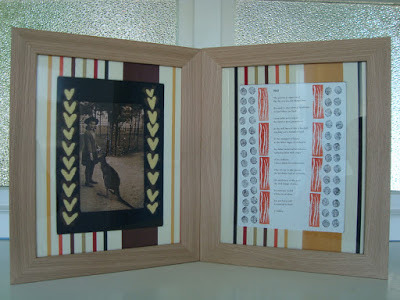

I did duly send off the poem, "Canberra Tales" (which you can read here, if you're curious) before the deadline in December last year, but then after that I don't think I heard any more about it. I assumed that it was a bit too weird and/or insufficiently concerned with landscape to be of much use, and so - instead - I received the lovely present last year of an art piece by Bronwyn based on the first part of the it!

Bronwyn Lloyd: 1942 (2016)

I have to say that I love art-poetry collaborations. It's always so exciting to see what an artist has made of your own crazy musings, and I do seem to have clocked up quite a few of them over the years (check it out here, if you don't believe me).

This one was a bit different, though: this one was international. For a start, Dianne Firth is pretty eminent among Australian artists. In fact, she was honoured with an Order of Australia Medal (OAM) in the 2017 Queen’s Birthday awards, which is no mean feat, and her work is clearly highly valued both in Australia and abroad. The brief for the show was as follows:

Inspired by her love of Canberra’s landscape and by contact with poets at the university’s Centre for Creative and Cultural Research, Firth invited poets from Australia and overseas who were in town for the summit to write about the beauty of our environment.I can't help wondering if I was the principal culprit among those 'who got carried away and came up with many poems' - as you can see from the list below, I seem to have been the only one whose poem got four separate works allotted to it!

Some of them got carried away and came up with many poems. One British poet declined, Canberra was too far from the hedgerows of England.

List of Works

The 14 poets in question, then, were:

From Canberra ... Jen Webb, Merlinda Bobis, Paul Hetherington, Subhash Jaireth, Penelope Layland, Paul Munden, Jen Crawford and Wiradjuri poet Jeanine Leane. From overseas ... Pamela Beasant (Scotland), Katharine Coles (US), Philip Gross (UK), Alvin Pang (Singapore) and Jack Ross and Elizabeth Smither (NZ).And here are a few of the 34 works included in the exhibition:

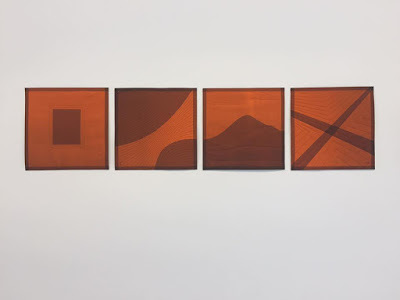

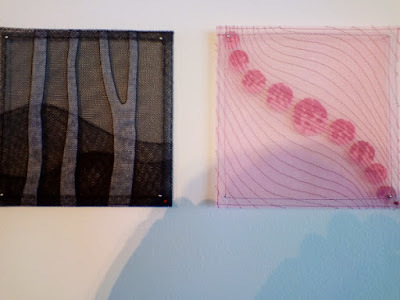

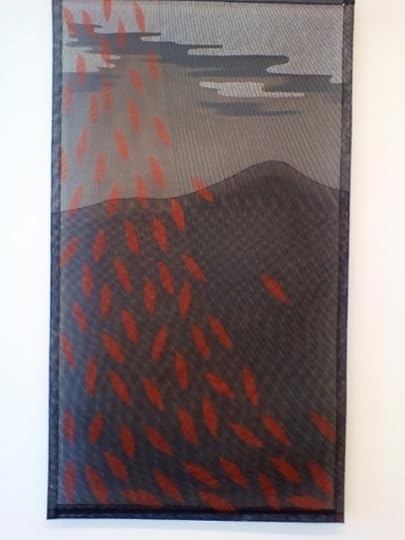

Dianne Firth: Pamela Beasant’s “Canberra”

Dianne Firth: Philip Gross

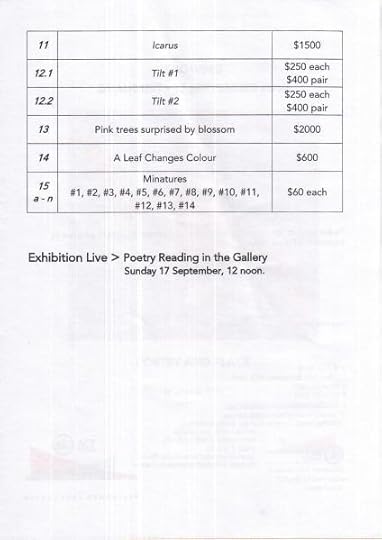

Dianne Firth: Subhash Jaireth’s “Ngambri (Black Mountain) Walking with Kobayashi Issa’s Snail”

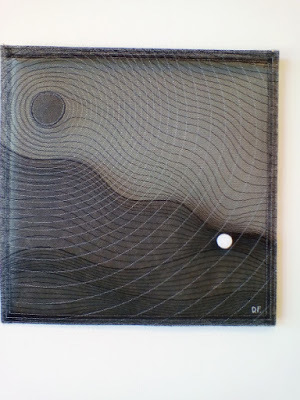

Dianne Firth: Jeanine Leane’s “Kamberra a Hundred Years On”

Dianne Firth: Alvin Pang

Dianne Firth: Jack Ross's "Canberra Tales"

Dianne Firth: Elizabeth Smither's "Pink Trees Surprised by Blossom" (detail)

Dianne Firth: Jen Webb

Dianne Firth: Philip Gross & Elizabeth Smither's works in situ

Dianne Firth: Further works in situ

So there's the show (or the closest I can get to reconstructing it at present). Unfortunately I was too late to buy the works based on my poem, but Jen Crawford and Jen Webb were both kind enough to take photos of it, and no doubt there will be more about it in the catalogue.

So, all in all, I think I'd have to rate this as one of the nicest surprises I've ever had: entirely out of left field, but one of those serendipitous events which sometimes light up one's day. Thanks, above all, Dianne Firth - but thanks, too, to Paul mUnden, for facilitating the choice of poems in the first place, and thanks to Jen Crawford, for reading out my poem at the end-of-exhibition event, and thanks to Jen Webb, for posting about it on facebook, and thus putting me on the right track!

Published on October 13, 2017 15:45

September 30, 2017

Allen Curnow Symposium

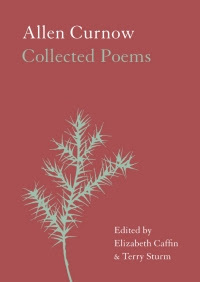

Allen Curnow: Collected Poems (2017)

A Symposium on the Life and Works of

Allen Curnow

30 September 2017

University of Auckland, Arts 1: Room 220

9.30 – 10.45

Panel One: Remembering Allen Curnow (I).

Chair, Alex Calder

C. K. Stead: ‘AC: informal recollections’Elizabeth Smither: ‘Allen & Jeny: a tribute’Wystan Curnow: ‘Venice’

10.45 - 11.00: Morning tea

11.00 - 12.35

Panel two: New Zealand Perspectives

Chair, Tom Bishop

Hugh Roberts: Unsettler Poetry: Curnow’s Literary Nationalism RevisitedJohn Newton, ‘All the History that Did Not Happen’Paul Millar: Curnow and PearsonPhilip Steer: Curnow and Environmentalism

12.35 - 1.15 Lunch

1.15 – 2.50

Panel three: Poetry and Poetics

Chair, Erin Carlson

Roger Horrocks: ‘Trying to save poetry from poetry’Dougal McNeill: ‘Abominable Tempers, Magic Makers: Allen Curnow, Earle Birney and Mid-Century Modernism’Harry Ricketts: ‘Allen Curnow: A post-Christian Poet’John Geraets: ‘Show and Tell: Curnow’s Stealth’

Afternoon tea: 2.50 – 3.10

3.10 - 4.25

Panel four: Early days, Latter days.

Chair, Alex Calder

Mark Houlahan: Curnow at SonnetsPeter Simpson: 'Contraries in two late Curnow poems: “A Busy Port” and “Looking West, Late Afternoon, Low Water”’.Jack Ross: ‘Teaching Late Curnow’.

Short break

4.30 – 5.45

Panel five: Remembering Allen Curnow (II)

Chair, Alex Calder

Michael Hulse: ‘That can’t be it!’Jan Kemp: Poems for Allen Curnow

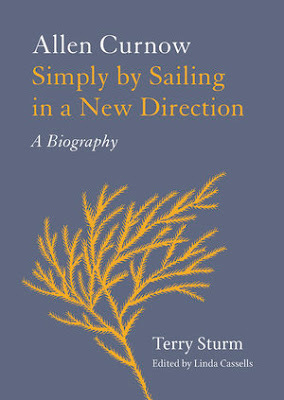

Terry Sturm: Simply by Sailing in a New Direction (2017)

So guess where I was yesterday ... One always approaches these events with a certain trepidation, I fear. I think you'll agree that the above list represents a pretty packed programme, but - as the prime mover of the whole affair, Alex Calder, remarked at the end - all the presenters "brought their A-game," and there was really never a dull moment in the whole day (not to mention an excellent lunch, which is more important than one might think for morale on such occasions).

There were numerous biographical revelations: Curnow's defiant contempt for homophobia, marching down Princes Street arm in arm with his theatre producer, who'd just been convicted of 'lewd acts,' in full sight of Auckland University's powers-that-were, was a particular high point (thanks for that detail, Paul Millar); and many of C. K. Stead's points about the 'authorised' nature of the biography were also shrewd and to-the-point. Michael Hulse, Jan Kemp and Elizabeth Smither contributed fascinating accounts of their very different friendships with both Allen and Jeny Curnow.

The Academic papers were uniformly excellent. I particularly enjoyed the focus on his earlier work provided by Hugh Roberts, John Newton, Dougal McNeill and Mark Houlahan. At times they overlapped, at other times disagreed, but the combined picture they presented certainly helped me to understand a lot of aspects of his poetry which had hitherto been quite opaque to me.

It's the later poetry, from the 1970s onwards, for which I myself feel a real enthusiasm (as I hope I revealed in my own paper on my strategies for teaching some of these poems to local students). Even here, though, there was much to learn. Roger Horrocks' ringing defence of the first book Curnow published after his long silence throughout the 1960s, Tree, Effigies, Moving Objects (1972), from the various accusations of 'roughness' and 'excessive obscurity' which bedevilled it at the time, was very persuasive, and Peter Simpson's analysis of two of these later poems both informative and charming. It tied in very well with Wystan Curnow's account of his father's long love affair with Italy, and - in particular - la città del sogno [dream city] itself, Venice, which Wystan interestingly contrasted with the Lyttelton of his childhood.

What else? My Massey Palmerston North colleague Philip Steer had many interesting things to say about the environmental concerns of the 1930s, and the ways in which they manifest in Curnow's early poetry; Harry Ricketts analysed the 'coldness' many have claimed to detect in Curnow's 'post-Christian' poetry - which (I guess) places it alongside the work of such precursors as Eliot and Montale, as well as the more overtly present Wallace Stevens. John Geraets contributed a condensed overview of his thinking about Curnow over the years, grouped around certain predominant themes.

There were some other voices I would have liked to hear. I would have liked Elizabeth Caffin and Linda Cassells to talk some more about their work on (respectively) the new collected poems and the biography. But since I was unfortunately unable to attend the booklaunch on Friday night, I suspect that they may have already discussed the subject there. It would have been interesting to hear some more details about it, though.

All in all, it was a great day out, and a very fitting tribute to one of our most important and (I suspect) enduring poets.

Another important presence there (albeit in absentia) was that of the late Professor Terry Sturm, whom I knew pretty well when I used to work in the English Department. He was a very kind as well as a very brilliant man, and I have nothing but good memories of him (including a rather surprising speech in the Senior Common Room one day, after probably all of us had had a bit too much to drink, on the improbability of some of the more surprising claims made routinely in Penthouse forum ...). He was a good boss and a straight-shooting talker. I greatly enjoyed reading his biography of pioneering novelist Edith Lyttleton, and anticipate the same enjoyment from his work on Allen Curnow.

•

Mangroves, Little Shoal Bay

Mangroves, Little Shoal Bay[Photograph: Ray Tomes (2009)]

from A Small Room with Large Windows (1957)

Comfortable

To creak in tune, comfortable to damn

Slime-suckled mangrove for its muddy truckling

With time and tide, knotted to the vein it leeches.

- Allen Curnow

New Zealand is a very small country, still. It's strange how many connections you can find with people you hardly know at all (except by reputation). Does it matter? I guess not really. It's fun to table a few of them, though:

My father told me that as kids they stayed in a boarding house in Akaroa where the Curnow family were also guests. They didn't much take to Allen, he said, but they had a great time playing with his brother Tony (this must have been sometime in the late 20s, I imagine, when my grandfather was working as a teacher in Templeton, on the outskirts of Christchurch).

Then my English teacher at Rangitoto College, Mr. Lamb, had many reminiscences of Allen Curnow as a lecturer. He retired from Auckland University a few years before I got there, though. In fact the only time I ever spoke to him was one day in (I think) 1986, when I was in the English Department mailroom and he asked me for help with the fax machine. I had to admit that it was a mystery to me, too, so there went my chance of making a good impression.

The next time I remember seeing him was at a poetry booklaunch in the late 1990s, where my friend Leicester Kyle finally gave into our persuasions that he go over and speak to the great man. Leicester's father, Cecil, who also had poetic ambitions, had been a fellow reporter of Curnow's on the Press in Christchurch in the 1930s, and they had some nice chat about it. There was a suggestion that Allen might write a preface to a collection of Leicester's own poems, but nothing ever came of that.

Connections: I know that Shoal Bay seascape of "A Small Room with Large Windows" very well. My grandmother lived in Ngataringa Bay, just around the headland, and we grew up sailing around on boats and wading over the mudflats. I don't know the West Coast beaches nearly as intimately as Curnow did, mind you. Of course I've been to Karekare many times, but have only stayed overnight there once. Muriwai is my favourite of those wonderfully evocative beaches, perhaps because it's really just round the corner from Mairangi Bay.

Karekare

Karekare[Photograph: Brad's pictures]

from A Dead Lamb (1972)

Never turn your back on the sea.

The mumble of the fall of time is continuous.

A billion billion broken waves deliver

a coloured glass globe at your feet, intact.

You say it is a Japanese fisherman's float.

It is a Japanese fisherman's float.

- Allen Curnow

Japanese Fisherman's Float

•

[Photograph: Marti Friedlander]

[Photograph: Marti Friedlander]Allen Curnow (1911-2001)

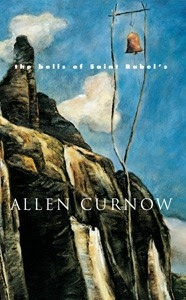

Poetry:

Valley of Decision: Poems. Auckland: Auckland University College Students' Association, 1933.Enemies: Poems 1934-36. Christchurch: Caxton Press,1937.Not in Narrow Seas: Poems with Prose. Christchurch: Caxton Press, 1939.Island and Time. Christchurch: Caxton Press, 1941Sailing or Drowning: Poems. Wellington: Progressive Publishing Society, [1946?]Jack Without Magic: Poems. Christchurch: Caxton Press, 1946.At Dead Low Water, and Sonnets. Christchurch: Caxton Press, 1949.Poems 1949-57. Wellington: Mermaid Press, 1957.A Small Room With Large Windows. London: Oxford University Press, 1962.Trees, Effigies, Moving Objects: A Sequence. Wellington: Catspaw Press, 1972.An Abominable Temper, and Other Poems. Wellington: Catspaw Press, 1973.Collected Poems 1933-1973. Wellington: A.W. and A.H. Reed, 1974.An Incorrigible Music. Dunedin: Auckland University Press, 1979.Selected Poems. Auckland: Penguin, 1982.You Will Know When You Get There: Poems 1979. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1982.The Loop in Lone Kauri Road. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1986.Continuum: New and Later Poems 1972-1988. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1988.Selected Poems 1940-1989. London: Viking, 1990.Early Days Yet: New and Collected Poems 1941-1997. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1997.The Bells of Saint Babel’s. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2001.Sturm, Terry, ed. Whim Wham’s New Zealand: The Best of Whim Wham, 1937-1988. A Vintage Book. Auckland: Random House New Zealand, 2005.Collected Poems. Ed. Elizabeth Caffin & Terry Sturm. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2017.[Appendix to Allen Curnow: Collected Poems. Ed. Elizabeth Caffin & Terry Sturm. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2017. Available at: http://www.press.auckland.ac.nz/en/curnow-collected-appendix.html].

Plays:

The Axe: a Verse Tragedy. Christchurch: Caxton Press, 1949.Four Plays: The Axe, The Overseas Expert, The Duke’s Miracle, Resident of Nowhere. Wellington: A.W. and A.H. Reed, 1972.

Prose:

Look Back Harder: Critical Writings 1935-1984. Edited by Peter Simpson. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1987.

Edited:

Book of New Zealand Verse: 1923-45. Christchurch: Caxton Press, 1945.A Book of New Zealand Verse: 1923-50. Christchurch: The Caxton Press, 1951.Penguin Book of New Zealand Verse. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1960.

Secondary:

Simpson, Peter. Allen Curnow: The Loop in Lone Kauri Road. Titirangi: Lopdell House Gallery, 1995.Sturm, Terry. Simply by Sailing in a New Direction. Allen Curnow: A Biography. Ed. Linda Cassells. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2017.

Webpages:

Aotearoa NZ Poetry Sound ArchiveNZ Book CouncilWikipedia

Published on September 30, 2017 18:09

September 14, 2017

'I Am Lost Without My Boswell'

Sir Joshua Reynolds: James Boswell of Auchinleck (1785)

The 1944 poem "Reading in Wartime" by Scottish poet (and pioneering translator of Kafka) Edwin Muir begins with the lines: "Boswell by my bed, / Tolstoy on my table":

Boswell's turbulent friendIf I understand him correctly, he seems to be saying that no-one can really die - no-one, that is, who leaves behind some kind of memory with the living.

And his deafening verbal strife,

Ivan Ilych's death

Tell me more about life,

The meaning and the end

Of our familiar breath,

Both being personal,

Than all the carnage can,

Retrieve the shape of man,

Lost and anonymous,

Tell me wherever I look

That not one soul can die

Of this or any clan

Who is not one of us

And has a personal tie

Perhaps to someone now

Searching an ancient book,

Folk-tale or country song

In many and many a tongue,

To find the original face,

The individual soul,

The eye, the lip, the brow

For ever gone from their place,

And gather an image whole.

If that is the case, then it's hard to imagine anyone who's left behind a more comprehensive record of himself than James Boswell, 9th Laird of Auchinleck (1740-1795).

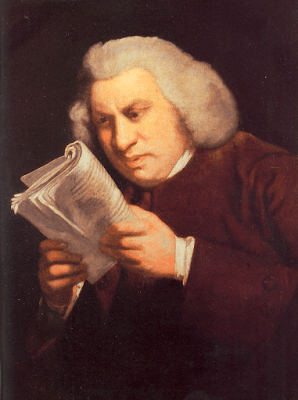

Sir Joshua Reynolds: Samuel Johnson (1775)

Most important of all, of course, is his massive (and still well worth reading) Life of Samuel Johnson (1791). But it's worth remembering that he was known in his lifetime as 'Corsica Boswell,' for his account of that little-known island in the throes of its struggle for freedom against the Genoese.

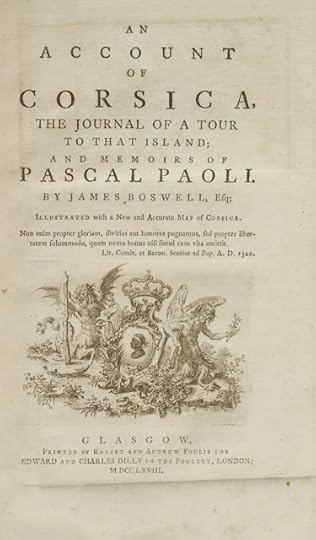

James Boswell: Journal of a Tour to Corsica; and Memoirs of Pascal Paoli (1768)

Here's a short list of his works (or most of the ones published in his lifetime, at any rate):

Boswell, James. Journal of a Tour to Corsica; and Memoirs of Pascal Paoli. 1768. Ed. Morchard Bishop. London: Williams & Norgate Ltd., 1951.

Boswell, James. Boswell’s Column: Being his Seventy Contributions to the London Magazine under the pseudonym The Hypochondriack from 1777 to 1783 Here First printed In Book Form in England. Ed. Margery Bailey. London: William Kimber, 1951.

Boswell, James. The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides with Samuel Johnson. 1785. Introduction by T. C. Livingstone. Collins Classics. London & Glasgow: Collins, 1955.

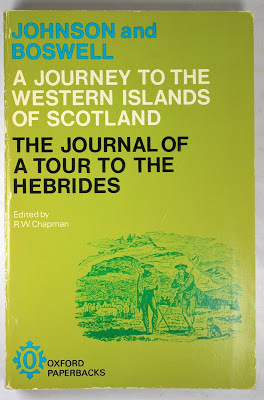

Johnson, Dr. Samuel & James Boswell. Johnson’s Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland & Boswell’s Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides with Samuel Johnson LL.D. 1775 & 1785. Ed. R. W. Chapman. 1924. London: Oxford University Press, 1970.

Boswell, James, Esq. The Life of Samuel Johnson, L.L.D. 1791. Introduction by Herbert Askwith. The Modern Library of the World’s Best Books. New York: Random House Inc., n.d.

Boswell, James. Boswell’s Life of Johnson. 1791. Ed. R. W. Chapman. Oxford Standard Authors. 1904. London: Geoffrey Cumberlege / Oxford University Press, 1953.

Johnson & Boswell: Journey to the Western Islands & A Tour to the Hebrides (1775 & 1785)

•

George Willison: James Boswell in Rome (1765)

Funnily enough, the real story started long after his death. After a memorable slagging off by Macaulay, Boswell's stock sank pretty low during most of the nineteenth century. He was seen as a kind of glorifeed shorthand report, whose sole claim to fame was that he happened to be present during some memorable events.

His undoubted skill in submerging himself in the moment worked very much against him, strangely enough. People continued to read the Life of Johnson, but Boswell's part in creating it was depreciated to the point of invisibility: as if a great book could somehow come into being despite its author.

It was thought, also, that the extensive archives of letters and journals he drew on to create the book had all perished in a 'fire in Scotland.' A few attempts were made to investigate this, but the family rebuffed them for various reasons (mostly to do with the very complicated state of their finances, partially due to the early deaths of both of Boswell's sons: James of illness, and Alexander, his direct heir, in a duel).

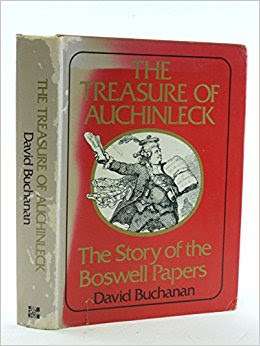

David Buchanan: The Treasure of Auchinleck (1974)

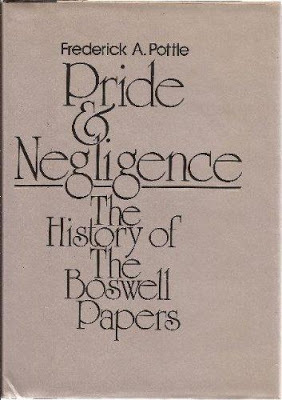

Until, that is, Colonel Isham came to tea. The tea party in question was in Malahide Castle near Dublin, the home of the direct heir to the line of Auchinleck, the time the 1920s, and the result of this fishing expedition by a well-connected American book collector forms the subject of two books: David Buchanan's The Treasure of Auchinleck (which focusses principally on Isham's fascinating thirty-year quest to unite the Boswell papers), and Frederick A. Pottle's more general history of the whole strange sage, Pride and Negligence.

Frederick A. Pottle: Pride and Negligence (1981)

The story is too complicated to summarise here, but suffice it to say that the papers spread over houses in two different countries, in attics and haylofts and cabinets in old dusty rooms, were eventually united -- after various complex law-suits -- at Yale University, whence they've been issuing in a steady stream ever since.

The jewel in the crown of all these efforts was undoubtedly Boswell's incomparable journal, kept on and off for four decades, and now published (not quite in full) with extensive annotations and commentary in a series of 13 volumes:

Frederick A. Pottle, ed.: Boswell's London Journal (1950)

Boswell, James. Boswell’s London Journal, 1762-1763. As First Published in 1950 from the Original Mss. Ed. Frederick A. Pottle. 1950. London: The Reprint Society, 1952.

Boswell, James. Boswell in Holland, 1763-1764: Including His Correspondence with Belle de Zuylen (Zélide). Ed. Frederick A. Pottle. Yale Editions of the Private Papers of James Boswell (Trade Editions, 2). London: William Heinemann, 1952.

Boswell, James. Boswell on the Grand Tour: Germany and Switzerland, 1764. Ed. Frederick A. Pottle. Yale Editions of the Private Papers of James Boswell (Trade Editions, 4). London: William Heinemann, 1953.

Boswell, James. Boswell on the Grand Tour: Italy, Corsica, and France, 1765-1766. Ed. Frank Brady & Frederick A. Pottle. Yale Editions of the Private Papers of James Boswell (Trade Editions, 5). London: William Heinemann, 1955.

Boswell, James. Boswell in Search of a Wife, 1766-1769. Ed. Frank Brady & Frederick A. Pottle. 1957. London: The Reprint Society, 1958.

Boswell, James. Boswell for the Defence, 1769-1774. Ed. William K. Wimsatt & Frederick A. Pottle. Yale Editions of the Private Papers of James Boswell (Trade Editions, 7). London: William Heinemann, 1959.

Boswell, James. Boswell’s Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides with Samuel Johnson, 1773. Ed. Frederick A. Pottle & Charles H. Bennett. Yale Editions of the Private Papers of James Boswell (Trade Editions, 8). London: William Heinemann, 1963.

Boswell, James. Boswell: The Ominous Years, 1774-1776. Ed. Charles Ryskamp & Frederick A. Pottle. Yale Editions of the Private Papers of James Boswell (Trade Editions, 9). London: William Heinemann, 1963.

Boswell, James. Boswell in Extremes, 1776–1778. Ed. Charles McC. Weis & Frederick A. Pottle. Yale Editions of the Private Papers of James Boswell (Trade Editions, 10). New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1970.

Boswell, James. Boswell: Laird of Auchinleck, 1778-1782. Ed. Joseph W. Reed & Frederick A. Pottle. Yale Editions of the Private Papers of James Boswell (Trade Editions, 11). New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1977.

Boswell, James. Boswell: The Applause of the Jury, 1782-1785. Ed. Irma S. Lustig & Frederick A. Pottle. Yale Editions of the Private Papers of James Boswell (Trade Editions, 12). New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1981.

Boswell, James. Boswell: The English Experiment, 1785-1789. Ed. Irma S. Lustig & Frederick A. Pottle. Yale Editions of the Private Papers of James Boswell (Trade Editions, 13). New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1986.

Boswell, James. Boswell: The Great Biographer, 1789-1795. Ed. Marlies K. Danziger & Frank Brady. Yale Editions of the Private Papers of James Boswell (Trade Editions, 14). New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, 1989.

Marlies K. Danziger & Frank Brady, ed.: Boswell: The Great Biographer (1989)

The first of the volumes, Boswell's London Journal (1762-63), which records his famous meeting with Dr. Johnson ("I come from Scotland, but I cannot help it'), was a publishing sensation. Appearing when it did, in buttoned-up 1950, its revelations of Boswell's whoring ways among the street women and courtesans of the metropolis, made it seem like a saucy, rollicking read.

With the best will in the world, the subsequent volumes could not really keep up this reputation, and by the time the series finished in 1989, its British publishers had given up on it entirely, and only MCgraw-Hill in America was prepared to keep on issuing it faithfully. All of which is a bit of a pity, because Boswell's skill as an autobiographer certainly didn't lessen over the years.

What other pieces of Boswelliana ought one to mention? Well, there's the fascinating (and previously unknown) collection of biographical sketches of his friends by Sir Joshua Reynolds, which was found among Boswell's papers, and therefore formed part of the Yale edition of his writings (there are actually two editions: one for the general reader, and another - far more expensive and slow to appear - of critical editions of all the papers in the collection): Reynolds, Sir Joshua. Portraits: Character Sketches of Oliver Goldsmith, Samuel Johnson, and David Garrick, together with other Manuscripts of Reynolds Recently Discovered among the Private Papers of James Boswell and now first published. Ed. Frederick W. Hilles Bodman. Yale Editions of the Private Papers of James Boswell (Trade Editions, 3). London: William Heinemann, 1952.

Boswell, James. Boswell’s Book of Bad Verse (A Verse Self-Portrait), or ‘Love Poems and Other Verses.’ Ed. Jack Werner. London: White Lion Publishers Limited, 1974.

Then there's the collection (above) of Boswell's poetry, for the really keen.

The standard biography is in two parts, the first by Frederick A. Pottle, the second by his long-time collaborator on the papers, Frank Brady. Adam Sisman's book, below, gives a good, succinct account of the complex process of composition which led to Boswell's immortal biography.

Pottle, Frederick A. James Boswell: The Earlier Years, 1740-1769. London: Heinemann, 1966.

Brady, Frank. James Boswell: The Later Years, 1769-1795. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1984.

Sisman, Adam. Boswell’s Presumptuous Task. 2000. London: Penguin, 2001.

So next time anyone solemnly informs you that Boswell was a good writer by accident rather than by design, or that it was somehow easy to compile the greatest biography in the English language, tell them they're full of it. That pompous old windbag Macaulay (as so often) was dead wrong on that one. Boswell's long journal (together with his lifetime's crop of letters) constitute one of the most entertaining reads you'll ever come across, as well as being an incomparable source of information on just about everything to do with British (and Continental) culture in the late eighteenth century.

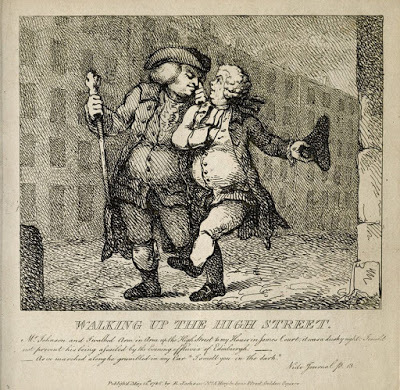

Thomas Rowlandson: The High Street in Edinburgh (1786)

Published on September 14, 2017 15:58

August 4, 2017

John Bunyan, Chief of Sinners

Thomas Sadler: John Bunyan (1684)

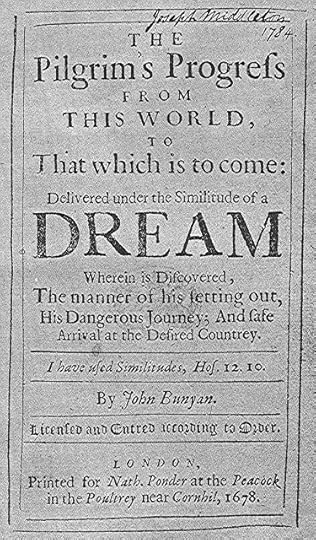

WHEN at the first I took my Pen in handFor quite some time after it came out, a number of informed judges were of the opinion that John Bunyan could not possibly have been the author of such works as The Pilgrim's Progress, written while he was in prison for daring to preach without a licence, though not published until 1678, six years after his release.

Thus for to write; I did not understand

That I at all should make a little Book

In such a mode; Nay, I had undertook

To make another, which when almost done,

Before I was aware I this begun.

Their difficulty lay in conceiving how an ill-educated tinker could have conceived so compelling and vivid a work of the imagination: not to mention demonstrated so consummate a command of English prose. That kind of thing was allowable to established wits such as Dryden and Congreve, not to mention erudite eccentrics such as the regicide Milton, but surely not to a member of the working classes!

John Bunyan: The Pilgrim's Progress (1678)

If you've never read it, rest assured that The Pilgrim's Progress is anything but a piece of dry-as-dust soul-searching. The story, with its fascinating echoes of the seventeenth century everyday of Bunyan's own experience, is absorbing enough, but the precise vernacular bite of the language he created to tell it lies behind virtually everything in the plain style which has been achieved since, from Swift to Cobbett to Orwell (not to mention, albeit at somewhat of a remove, Huckleberry Finn).

"The Author's Apology for His Book" is sometimes quoted as an example of the flatness of Bunyan's verse. I can assure you, though (as one who has tried it), that writing with such simplicity and directness as this is not an easy proposition: it is, in fact, much harder than the so-many-couplets-by-the-yard stuff, full of Classical allusions and pompous periphrases, which poets such as Dryden could more or less produce at will:

Neither did I but vacant seasons spend

In this my Scribble; nor did I intend

But to divert myself in doing this

From worser thoughts which make me do amiss.

John Bunyan: Grace Abounding (1666)

What were these "worser thoughts"? The reason that Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners (1666), his spiritual autobiography, published while he was still in prison, is such a terrifying book to read is that it chronicles such excesses of paranoid self-scrutiny as to border, at times, on madness. There's one famous passage, in particular, where Bunyan is tempted to commit the sin against the Holy Ghost (what precisely this sin consists of has never been made quite clear, which is one reason it continues to terrify neurotic believers - such as myself as a child - to this day):

One day the temptation was hot upon me to try if I had faith by doing some miracle; which miracle was this, I must say to the puddles, Be dry, and to the dry places, Be you puddles.This may sound a bit ridiculous, but it was anything but that to Bunyan. He persuaded himself that he had committed this sin, and was therefore damned to hell, and the sufferings he endured make grim (though also, at times, fascinating) reading. Eventually he escaped from this delusion. Prison was nothing beside it. By comparison, he endured twelve years of incarceration in Bedford Gaol with a light heart:

Thus I set Pen to Paper with delight,The idea of writing fiction was certainly an alien one to Bunyan. There were no English novels as yet, though prose tales had been told and published as far back as the Middle Ages. He therefore chose allegory as his vehicle.

And quickly had my thoughts in black and white.

For having now my Method by the end,

Still as I pull’d, it came; and so I penn’d

It down, until it came at last to be

For length and breadth the bigness which you see.

Well, when I had thus put mine ends together,Luckily he'd learnt by then to trust his own judgement - or, rather, God's:

I shew’d them others, that I might see whether

They would condemn them, or them justifie;

And some said, Let them live; some, Let them die;

Some said, John, print it; others said, Not so:

Some said, It might do good; others said, No.

At last I thought, Since you are thus divided,Admittedly there are one or two aspects of the work which cause a certain amount of consternation nowadays: the cave where the giants 'Pope' and 'Pagan' waylay and eat unwary travellers, for instance, but for the most part the descriptions of the corrupt magistrates of Vanity Fair and the prevarications of Mr. Worldly Wiseman still ring disconcertingly true.

I print it will, and so the case decided.

There are many modern editions of his most famous book. I've listed the ones I myself own below. Funnily enough, the most interesting to read is the one which I've put second on the list, the nineteenth-century 'religious tracts' edition, which gives Biblical references and running commentary in little squares of text along the way. It has a real feel of the intensity with which this book was once read.

The Complete Works is a very strange book indeed, with a carved wooden cover and illustrations throughout. It's not terribly convenient to read, but is definitely a thing of beauty in itself:

John Bunyan: Complete Works (1881)

John Bunyan

(1628-1688)

Bunyan, John. The Complete Works. Introduction by John P. Gulliver. Illustrated Edition. Philadelphia; Brantford, Ont.: Bradley, Garretson & Co. / Chicago, Ills.; Columbus, Ohio; Nashville, Tenn.; St. Louis, Mo.; San Francisco, Cal.: Wm. Garretson & Co., 1881.

Bunyan, John. The Pilgrim’s Progress from This World to That Which Is To Come: Delivered Under the Similitude of a Dream. London: The Religious Tract Society, n.d. [1877].

Bunyan, John. The Pilgrim’s Progress. Ed. Roger Sharrock. 1965. The Penguin English Library. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1975.

Bunyan, John. Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners and The Pilgrim’s Progress from this World to that which is to come. 1666, 1678, & 1684. Ed. Roger Sharrock. 1962 & 1960. Oxford Standard Authors. London: Oxford University Press, 1966.

Bunyan, John. Grace Abounding & The Life and Death of Mr Badman. 1666 & 1680. Introduction by G. B. Harrison. An Everyman Paperback. Everyman’s Library, 1815. 1928. London: J. M. Dent & Sons / New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1969.

Bunyan, John. The Life and Death of Mr. Badman. 1680. Introduction by Bonamy Dobrée. The Worlds’ Classics, 338. London: Humphrey Milford / Oxford University Press, 1929.

Bunyan, John. The Holy War Made by King Shaddai upon Diabolus To regain the Metropolis of the World or, The Losing and Taking Again of the Town of Mansoul. 1682. Ed. Wilbur M. Smith. The Wycliffe Series of Christian Classics. Chicago: Moody Press, 1948.

I wrote this post at the suggestion of my good friend Richard Taylor, who seemed to feel that it might make a good follow-up to my posts on Spenser and Malory. I can't say that I regret having spent so much of my youth reading such ponderous tomes. Now, in my more frivolous middle age, I don't know that I'd have the energy to start on them from scratch (let alone such works as Piers Plowman or Beowulf, which I once had the application to plough through in the original).

Much of Bunyan's work is, however, extremely readable, and The Holy War and The Life and Death of Mr. Badman (great title!) are well worth pursuing if you take a liking to The Pilgrim's Progress (both are better than part two of that work, to be honest).

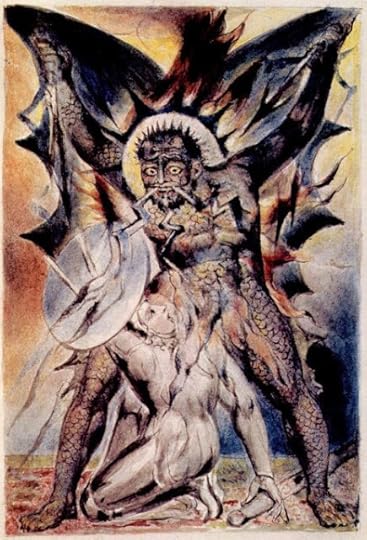

I suppose my main interest in him nowadays is as a predecessor to such literary non-conformists as William Blake and John Clare, however. There's a fascinating tradition there, which I write about in more detail in one of my posts on contemporary English poet Peter Reading.

William Blake: Christian fights Apollyon (c. 1824-27)

Published on August 04, 2017 15:20

July 15, 2017

Orwelliana

Eric Blair ['George Orwell'] (1903-1950)

The other day a bunch of us were sitting around talking about books (as you do), when someone asked us each to name our favourite author. The answers were pretty interesting - and quite revealing. Bronwyn said 'Tracey Slaughter,' her sister Thérèse said 'Anne Carson,' Martin said 'Salman Rushdie,' I said 'Guillaume Apollinaire,' and my brother-in-law Greg said 'George Orwell.'

I guess on another day any one of us might have mentioned somebody else ('Stephen King' would probably have been more accurate for me, if the truth be told). But Orwell - that was the name that really struck me, and the response I envied most.

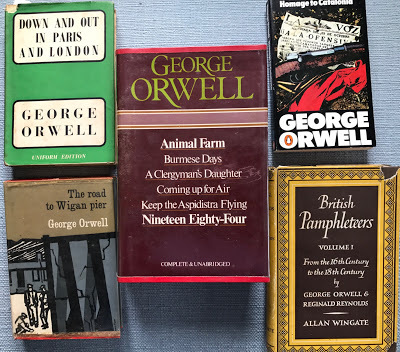

I've been reading his books for forty years, I'm astonished to discover. My second-hand copy of the 'Uniform Edition' of Down and Out in Paris and London cost me 20 cents in 1977, I see on the inside flap, and I acquired copies of The Road to Wigan Pier and Homage to Catalonia not much later. I'm sure I'd already read Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four by then, though it wasn't till I bought the large hardback 'Octopus Books' edition of his complete novels that I read the other ones. Coming Up for Air is probably my favourite book of his, actually.

Orwell, George. Down and Out in Paris and London. 1933. Uniform Edition. 1949. London: Martin Secker & Warburg Ltd., 1951.Orwell, George. The Road to Wigan Pier. 1937. Uniform Edition. London: Martin Secker & Warburg Ltd., 1959.Orwell, George. Homage to Catalonia, & Looking Back on the Spanish War. 1938 & 1953. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978. Orwell, George. Burmese Days / A Clergyman's Daughter / Keep the Aspidistra Flying / Coming Up for Air / Animal Farm / Nineteen Eighty-Four. 1934, 1935, 1936, 1939, 1945, 1949. London: Martin Secker & Warburg Limited / Octopus Books Limited, 1976.Orwell, George, & Reginald Reynolds, ed. British Pamphleteers. Volume 1: From the 16th Century to the French Revolution. London: Allan Wingate, 1948.

Nine books: 6 novels, 3 books of non-fiction reportage, plus a couple of collections of reprinted essays: that was his life's work. Or all of it that was accessible to us for a long time, that is.

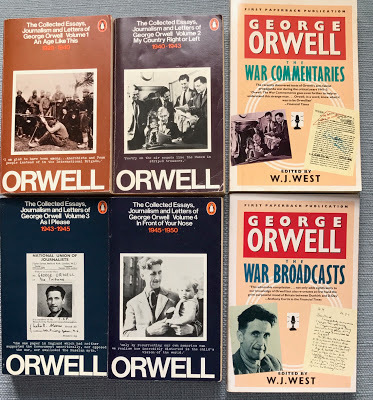

There was all the fuss about him when the year 1984 finally dawned, of course. I dutifully went out and bought the facsimile edition of the manuscript of the novel. More significantly, though, it must have been around then that I discovered the Penguin editions of his Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters:

Orwell, George. Nineteen Eighty-Four: The Facsimile of the Extant Manuscript. Ed. Peter Davison. Preface by Daniel G. Siegel. London: Martin Secker & Warburg Limited / Weston, Massachusetts: M & S Press Inc., 1984.Orwell, George. The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell. Volume 1: An Age Like This, 1920–1940. Ed. Ian Angus & Sonia Brownell. 1968. 4 vols. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970.Orwell, George. The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell. Volume 2: My Country Right or Left, 1940–1943. Ed. Ian Angus & Sonia Brownell. 1968. 4 vols. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1977.Orwell, George. The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell. Volume 3: As I Please, 1943–1945. Ed. Ian Angus & Sonia Brownell. 1968. 4 vols. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978.Orwell, George. The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell. Volume 4: In Front of Your Nose, 1945–1950. Ed. Ian Angus & Sonia Brownell. 1968. 4 vols. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978.

That was an absolute revelation. For the first time it was possible to get some idea of what it must have felt like to be 'George Orwell' - all the ups and downs of his extraordinary life and times, from the slums of the Depression through the Spanish War through the Second World War and out the other side into postwar austerity. I still think this four-volume collection is a miracle of good taste and good editing.

It did, though, have the effect of making me feel that I now knew the man inside out. I did buy the volumes of hitherto undiscovered War Broadcasts which appeared in 1985, but it was with a certain reluctance. They were - to tell the truth - a little tedious taken out of context, and the great thing about Ian Angus and Sonia Orwell's tapestry had been the discovery that Orwell almost never wrote a boring or superfluous word.

Orwell, George. The War Broadcasts. Ed. W. J. West. 1985. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1987.Orwell, George. The War Commentaries. Ed. W. J. West. 1985. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1987.

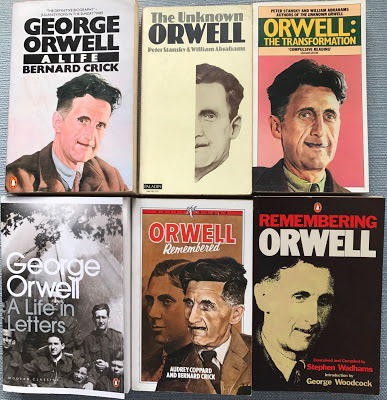

That's where I stopped. For the past thirty years I've refreshed my memory of his work from the collected edition from time to time, but I haven't read each of the successive Orwell biographies, full as each of them has been of hitherto unsuspected 'facts' (that he was an exhibitionist, that he wasn't an exhibitionist, that he calculated his public persona carefully, that he stumbled into his public persona, etc. etc.) I was aware that there was some monstrous multi-volumed beast called the Complete Works, but I assumed that it mostly repeated what I already knew.

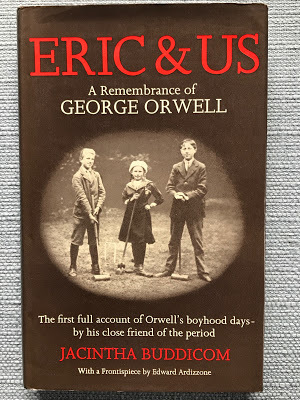

Buddicom, Jacintha. Eric and Us: A Remembrance of George Orwell. London: Leslie Frewin Publishers Limited, 1974.Stansky, Peter, & William Abrahams. The Unknown Orwell. 1972. A Paladin Book. Frogmore, St. Albans, Herts.: Granada Publishing Limited, 1974.Stansky, Peter, & William Abrahams. Orwell: The Transformation. 1979. A Paladin Book. Frogmore, St. Albans, Herts.: Granada Publishing Limited, 1981.Crick, Bernard. George Orwell: A Life. 1980. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1982.Coppard, Audrey, & Bernard Crick. Orwell Remembered. Ariel Books. London: British Broadcasting Corporation, 1984.Wadhams, Stephen, ed. Remembering Orwell. Introduction by George Woodcock. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1984.

That is, until the other day when I ran across a second-hand copy of Orwell's Diaries, edited by a certain Peter Davison (not the Dr. Who actor, in case you were wondering), which claimed on its blurb to be the closest thing to the 'autobiography he never wrote.'

I bought it, of course, and in the process of investigating its introduction and apparatus, chanced on the extraordinary saga of Davison's own forty-year struggle with Orwell's work. (You can read his fascinating 2012 essay "The Troubled History Behind George Orwell's Complete Works" here).

Orwell, George. Diaries. Ed. Peter Davison. Harvill Secker. London: Random House, 2009.Orwell, George. A Life in Letters. Ed. Peter Davison. 2010. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin, 2011.

Peter & Sheila Davison (2010)

The critical response to Peter Davison's self-imposed task has been, to be honest, a little mixed. Quite a few reviewers have criticised him for his 'boots and all' approach to Orwell's work, preferring the more nuanced approach of Ian Angus and Orwell's second wife Sonia. But when I read in one of these pieces that the latter had attempted pretty systematically to expunge his first wife Eileen O'Shaughnessy (who died in 1945) from the record, I began to think that there might be something to be said for the wholesale approach after all.

And so it has proved. I'm steadily working my way through the eleven volumes of what Davidson describes as "his and his wife Eileen’s letters (some 1,100), 265 articles, 380 reviews, lecture notes and research materials, diaries (apart from one or two still believed to be held in the NKVD Archive in Moscow), his hundreds of BBC broadcasts to India and the arrangements for making those, together with a selection of letters written to him." True, some of the juvenilia is a bit lame, but pretty much from the publication of his first pieces of journalism in Paris, the authentic voice is very much in evidence.

Does anyone deserve to be documented on quite this scale? Well, I'm sure that it would horrify Orwell himself, but if anyone merits it, he does. Even his most hurried reviews are always sensible and interesting - and have the effect of providing a potted history of two decades of English intellectual life, as well as their many other virtues. The letters and diaries are also fascinating. Reading it is really like discovering a whole new Orwell: not the careful craftsman of the nine books, or the more expansive - but still rigorously controlled - journalist of the Ian Angus / Sonia Orwell selection, but a warts-and-all portrait of the artiste engagé.

Davison, Peter, with Ian Angus & Sheila Davison, ed. The Complete Works of George Orwell. 10: A Kind of Compulsion: 1903–1936. 1998. London: Secker & Warburg, 2000.Davison, Peter, with Ian Angus & Sheila Davison, ed. The Complete Works of George Orwell. 11: Facing Unpleasant Facts: 1937–1939. 1998. London: Secker & Warburg, 2000.Davison, Peter, with Ian Angus & Sheila Davison, ed. The Complete Works of George Orwell. 12: A Patriot After All: 1940–1941. 1998. London: Secker & Warburg, 2002.Davison, Peter, with Ian Angus & Sheila Davison, ed. The Complete Works of George Orwell. 13: All Propaganda Is Lies: 1941–1942. 1998. London: Secker & Warburg, 2001.Davison, Peter, with Ian Angus & Sheila Davison, ed. The Complete Works of George Orwell. 14: Keeping Our Little Corner Clean: 1942–1943. 1998. London: Secker & Warburg, 2001.Davison, Peter, with Ian Angus & Sheila Davison, ed. The Complete Works of George Orwell. 15: Two Wasted Years: 1943. 1998. London: Secker & Warburg, 2001.Davison, Peter, with Ian Angus & Sheila Davison, ed. The Complete Works of George Orwell. 16: I Have Tried to Tell the Truth: 1943–1944. 1998. London: Secker & Warburg, 2001.Davison, Peter, with Ian Angus & Sheila Davison, ed. The Complete Works of George Orwell. 17: I Belong to the Left: 1945. 1998. London: Secker & Warburg, 2001.Davison, Peter, with Ian Angus & Sheila Davison, ed. The Complete Works of George Orwell. 18: Smothered Under Journalism: 1946. 1998. London: Secker & Warburg, 2001.Davison, Peter, with Ian Angus & Sheila Davison, ed. The Complete Works of George Orwell. 19: It Is What I Think: 1947–1948. 1998. London: Secker & Warburg, 2002.Davison, Peter, with Ian Angus & Sheila Davison, ed. The Complete Works of George Orwell. 20: Our Job Is to Make Life Worth Living: 1949–1950. 1998. London: Secker & Warburg, 2002.Davison, Peter, ed. The Lost Orwell: Being a Supplement to The Complete Works of George Orwell. London: Timewell Press Limited, 2006.

I'm astonished that I didn't think to investigate these 11 volumes (plus supplementary volume) before. In a sense, though, I'm glad. Now I can savour the treat fully, and at my leisure: rather than waiting for each new volume to appear in a fever of impatience.

There is, of course - given Davison's mania for completeness - more to it than that. The first nine volumes of his edition provide critical texts for each of the novels and books of reportage (texts more readily available now through Penguin Modern Classics). He has also edited four volumes of selections from the edition, each focussed on a particular book of Orwell's:

Davison, Peter, ed. Orwell and the Dispossessed: Down and Out in Paris and London in the Context of Essays, Reviews and Letters Selected from The Complete Works of George Orwell. Introduction by Peter Clarke. Penguin Modern Classics. London: Penguin, 2001.Davison, Peter, ed. Orwell's England: The Road to Wigan Pier in the Context of Essays, Reviews and Letters Selected from The Complete Works of George Orwell. Introduction by Ben Pimlott. Penguin Modern Classics. London: Penguin, 2001.Davison, Peter, ed. Orwell in Spain: The Full Text of Homage to Catalonia with Associated Articles, Reviews and Letters from The Complete Works of George Orwell. Introduction by Christopher Hitchens. Penguin Modern Classics. London: Penguin, 2001.Davison, Peter, ed. Orwell and Politics: Animal Farm in the Context of Essays, Reviews and Letters Selected from The Complete Works of George Orwell. Introduction by Timothy Garton Ash. Penguin Modern Classics. London: Penguin, 2001.

Simon Schama's classic TV series on the History of Britain concludes with an episode entitled "The Two Winstons," contrasting Orwell's Winston Smith (from 1984) with that other Winston, Winston Churchill, as a way of exploring the UK in the twentieth century.

Simon Schama: A History of Britain (2002)

It works quite well, really. While I demonstrated in my previous post that I have spent quite a lot of time poring over Winston Churchill's literary remains, there is, I'm afraid, no comparison with the interest I feel in Orwell's. He really is one of the greatest writers of the last century, and it's nice to be able to see his work whole and entire at last, thanks to the largely thankless labours of that culture-hero Peter Davison.

Is Orwell really relevant anymore? What do you think?

Published on July 15, 2017 19:50

June 20, 2017

Churchill on Screen

Ivor Robert-Jones: Winston Churchill (1973)

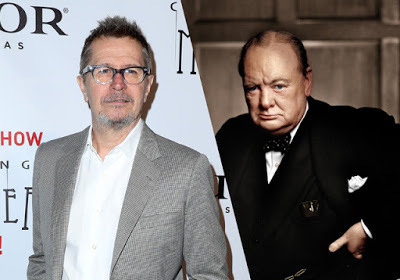

So who, so far, has played Winston Churchill on screen? Just about every portly British actor of a certain age, that's who. Nicholas Asbury, Brian Cox, Albert Finney, Michael Gambon, Robert Hardy, Bob Hoskins, Toby Jones, John Lithgow, Ian McNeice, Gary Oldman, Timothy Spall, Simon Ward, Timothy West - even American comic John Lithgow. Do any of them look at all like the man himself? No, not particularly. But on they come, scowling and spitting, nevertheless.

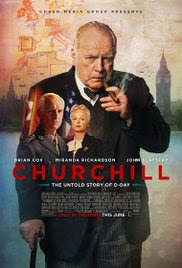

Churchills (2017)

They've certainly come at the problem of how to represent him from virtually every angle, one must admit: as a schoolboy and young adventurer in Young Winston; as a WWI Cabinet Minister in 37 Days; as a prophetic outcast in The Wilderness Years and The Gathering Storm; as wartime PM in Into the Storm, Churchill and the Generals, and now Churchill and the yet-to-be-released Darkest Hour; and then as a dithering old monument of the Tory party in Churchill's Secret and The Crown. Apparently, according to the IMDb, there have been no fewer than 208 such screen impersonations so far.

Why do I keep on watching them? Am I insane? (Don't answer that). It's not that there's much to be expected from each new growl-athon, and yet I find myself drawn to them for some odd reason. It's certainly not that I approve of his Conservative, Empire-building politics - and as for that statement at the end of Churchill, one of the very worst of these films, that he is 'often acclaimed as the greatest Briton of all time,' what does that even mean? Was he a better writer than Shakespeare? A more important statesman than Cromwell? A more visionary strategist than his great ancestor the Duke of Marlborough? Clearly not.

And yet ... It's impossible for someone of my generation, at least, to listen to those 1940s speeches of Churchill's - even soundbytes from same - without emotion. Just those little phrases: "I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat" - "Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few" - and, above all, "Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves, that if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, This was their finest hour."

You ask, what is our policy? I will say: It is to wage war, by sea, land and air, with all our might and with all the strength that God can give us; to wage war against a monstrous tyranny, never surpassed in the dark and lamentable catalogue of human crime. That is our policy. You ask, what is our aim? I can answer in one word: Victory. Victory at all costs — Victory in spite of all terror — Victory, however long and hard the road may be, for without victory there is no survival.

War-time Poster (1940)

Even though large tracts of Europe and many old and famous States have fallen or may fall into the grip of the Gestapo and all the odious apparatus of Nazi rule, we shall not flag or fail. We shall go on to the end. We shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender, and if, which I do not for a moment believe, this island or a large part of it were subjugated and starving, then our Empire beyond the seas, armed and guarded by the British Fleet, would carry on the struggle, until, in God's good time, the New World, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and the liberation of the old.That's the true Churchillian music. That was the moment when a lifetime of poring over maps and old books, and practising his orotund oratorical skills in parliament and on the hustings paid off, and the world suddenly stopped, and listened, and liked what they heard.

What they heard was defiance, and that was what was needed then - but there was more to it than that. It was how he put it. It was the difference between the vicious ravings of Dr. Goebbels - Wollt ihr den totalen Krieg? - and the warlike speeches in Henry V. It mattered, somehow.

Maybe that's why I keep on coming back to these films. After watching the deplorable spectacle a couple of days ago of President Trump introducing his cabinet of dullards and losers, each one of whom said what an "honour" and a "privilege" it was to serve their pitiful Dark Lord - shades of the compulsory standing ovations after each of Stalin's speeches ("Never be the first to stop clapping, Comrade") - it's refreshing to hear someone expressing such honest defiance against all the shopsoiled tyrants of the world ...

So here's my own list. I've seen all but one or two of them, I think. And I fear I'll be trotting along dutifully to watch Gary Oldman add his bit of cigar-puffing and wheezing to all the others in a few months time:

Young Winston (1972)

Young Winston: feature film, dir. Richard Attenborough, writ. Carl Foreman (based on Churchill's memoir My Early Life) - with Simon Ward as Churchill & Anne Bancroft as his Mum, Lady Randolph Churchill (née Jennie Jerome) - (UK, 1972)

Great stuff. Hugely entertaining. It also had the effect of putting me onto My Early Life, which is probably Churchill's most entertaining book.

Churchill and the Generals (1979)

Churchill and the Generals: made-for-TV film, dir. Alan Gibson, writ. Ian Curteis - with Timothy West as Churchill - (UK, 1979)

Haven't seen it. It sounds pretty good, though. I presume it's based - at least partially - on Field Marshall Alanbrooke's very revealing diaries about his time with Churchill.

The Wilderness Years (1981)

Winston Churchill: The Wilderness Years: 8-part TV Series, dir. Ferdinand Fairfax, writ. Ferdinand Fairfax & William Humble (based on Martin Gilbert's biography) - with Robert Hardy as Churchill & Siân Phillips as Clementine Churchill ('Clemmie') - (UK, 1981)

Love it. A lot of detail, and a genuine sense of the complexity of his personality. Siân Phillips plays a sinuous and rather distant Clemmie (a lot like her Livia in I Claudius, actually).

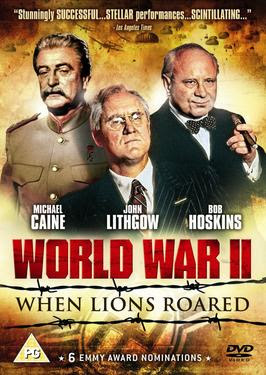

World War II: When Lions Roared (1994)

World War II: When Lions Roared: 3-part TV miniseries, dir. Joseph Sargent, writ. David Rintels - with Bob Hoskins as Churchill, John Lithgow as Roosevelt & Michael Caine as Stalin - (USA, 1994)

Haven't seen it. The prospect of seeing Michael Caine, of all people, play Stalin makes it tempting to hunt it down, though. It's funny to think of John Lithgow going full circle from Roosevelt, here, to Churchill in The Crown - with a quarter of a century in between.

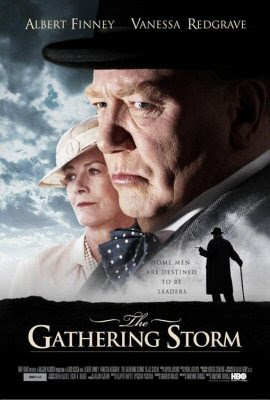

The Gathering Storm (2002)

The Gathering Storm: feature film, dir. Richard Loncraine, writ. Hugh Whitemore - with Albert Finney as Churchill & Vanessa Redgrave as 'Clemmie' - (UK / USA, 2002)

Rather repetitive of The Wilderness Years, but still very dramatic and entertaining. Vanessa Redgrave is a rather more affectionate but distinctly more tempestuous Clemmie than Siân Phillips.

Into the Storm (2009)

Into the Storm [aka Churchill at War]: feature film, dir. Thaddeus O'Sullivan, writ. Hugh Whitemore - with Brendan Gleeson as Churchill & Janet McTeer as Clemmie - (UK / USA, 2009)

A shame they couldn't keep the same cast as in The Gathering Storm, but still a good overview of the war years, focussing on 1940 as a flashback from election defeat in 1945. Brendan Gleeson is a lot less loveable and definitely more of a pain than Albert Finney, but Janet McTeer's Clemmie steers a steady course between the Scylla of Siân and the Charybdis of Vanessa.

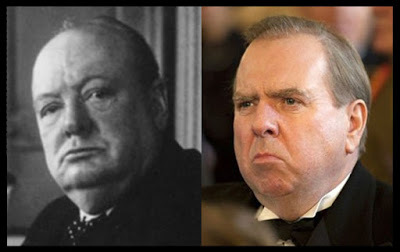

Timothy Spall as Churchill (2010)

The King's Speech: feature film, dir. Tom Hooper, writ. David Seidler - with Timothy Spall as Churchill - (UK, 2010)

I guess it was inevitable that he'd get to do it sooner or later: somewhere between his bestial Turner and his suave and manipulative David Irving comes Timothy Spall's Churchill.

Dr Who: Victory of the Daleks (2010)

Dr Who: Victory of the Daleks: TV series, dir. Andrew Gunn, writ. Mark Gatiss - with Ian McNeice as Churchill - (UK, 2010)

Not a subtle impersonation, perhaps, but then the modern version of Dr Who doesn't really do subtle.

Toby Jones

Fleming: The Man Who Would be Bond: 4-part TV miniseries, dir. Mat Whitecross, writ. John Brownlow & Don Macpherson - with Toby Jones as Churchill - (UK, 2014)

Just a cameo, really, but rather a good show on Toby Jones's part, I thought - making a nice change from the tedious bedhopping of the protagonist and the future Mrs. Fleming.

Nicholas Asbury as Churchill (2014)

37 Days: 3-part TV miniseries, dir. Justin Hardy, writ. Mark Hayhurst - with Nicholas Asbury as Churchill - (UK, 2014)

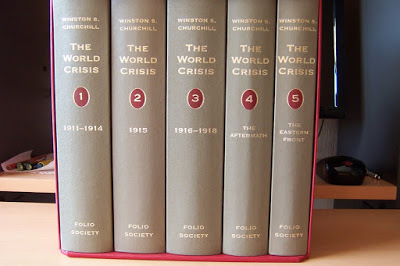

Churchill is played here as a knowing politician, alert to all the complexities of a question which apparently evade his superiors. Whether - to one, like myself, who's read his 5-volume World War I memoirs The World Crisis - this is accurate or not is questionable, but it makes for good drama, at any rate.

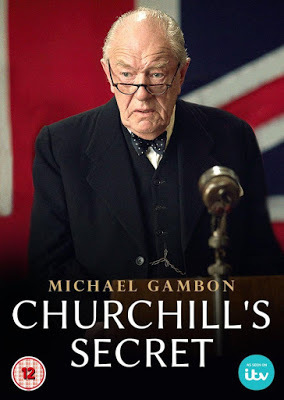

Churchill's Secret (2016)

Churchill's Secret: made-for-TV film, dir. Charles Sturridge, writ. Stewart Harcourt (based on the book The Churchill Secret: KBO by Jonathan Smith) - with Michael Gambon as Churchill & Lindsay Duncan as Clemmie - (UK / USA, 2016)

Kind of a pointless piece of mystification. Churchill's advisors cover up how unfit he is for office, all of which plays some part in making Anthony Eden so frustrated that he takes it out on Nasser. True(ish), possibly, but not exactly earth-shattering.

John Lithgow as Churchill (2017)

The Crown: Series 1: 10-part TV Series, writ. Peter Morgan - with John Lithgow as Churchill - (UK / USA, 2016)

This I haven't yet seen, but I'm rather looking forward to doing so.

Churchill (2017)

Churchill: feature film, dir. Jonathan Teplitzky, writ. Alex von Tunzelmann - with Brian Cox as Churchill & Miranda Richardson as Clemmie - (UK, 2017)

While I have to confess to enjoying it overall, I do think the multiple inaccuracies and exaggerations of the film do make it a very unfortunate version of Churchill. Certainly he was a pain around the office. Certainly he opposed the frontal assault in France (proposing, according to Alanbrooke, a diversion to Portugal at a very late stage in proceedings). Certainly he demanded to go over himself on D-Day - but all the Gallipoli references completely belie his own view of that campaign. Of course it was a disaster, but his point (as expounded very thoroughly in volume 2 of The World Crisis) was that this was inevitable given the piecemeal and futile way the idea of a landing was stumbled into. To give it as the main reason why he opposed the Normandy landings is sentimental tosh and plain wrong: and putting in all those stupid details designed to show how "out-of-date" he was in terms of contemporary tactics is also very misleading. Nor is the choice of Montgomery as the visionary commander putting him straight a particularly happy one, given the latter's blunders in Normandy and after ... Still, there are some pretty moments here and there. Miranda Richardson plays by far the most terrifying and contemptuous Clemmie to date.

Darkest Hour (2017)

Darkest Hour: feature film, dir. Joe Wright, writ. Anthony McCarten - with Gary Oldman as Churchill & Kristin Scott Thomas as Clemmie - (UK, 2017)

I presume - though I don't know - that this will be about the period when Churchill was fighting Lord Halifax in cabinet to prevent the initiation of peace-talks (brokered by Mussolini) after the fall of France. Subsequent historians have suggested that this was a more vicious and no-holds-barred battle than anything that followed it in parliament, let alone the country at large. Hitler still had many friends and admirers in the British establishment at that point, and they would have done virtually anything to prevent a shooting war. That's the context where those speeches, quoted above, come in. Is it better to die on your feet than live on your knees? That's not, and never has been, an easy question to answer.

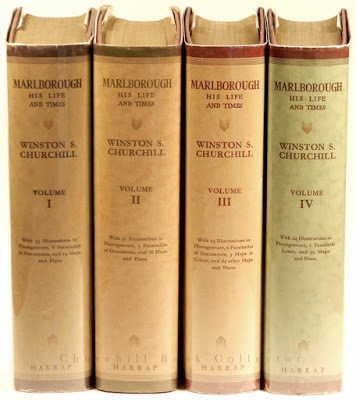

•

And here's a list of my own Churchilliana. I do find his books very readable and well expressed (if a trifle tendentious at times), and certainly indispensable to any student of the great European Civil War (1914-45). Some, though, are genuinely illuminating. Having read both G. M. Trevelyan's classic England Under Queen Anne trilogy (1930-34) and Churchill's four-volume Marlborough biography in very close succession last year, I can tell you that the latter certainly complements the former very well, and (almost) made it possible for me to understand the morass of late seventeenth / early eighteenth century European politics for the first time.

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill

(1874-1965)

Frontiers and Wars (1898-1900)

Churchill, Winston S. Frontiers and Wars: His Four Early Books, Covering His Life as Soldier and War Correspondent, Edited into One Volume. ["The Story of the Malakand Field Force" (1898); "The River War" (1899); "London to Ladysmith via Pretoria" (1900); "Ian Hamilton's March" (1900)]. 1962. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972.

Churchill, Winston S. The River War. 1899. A Four Square Book. London: New English Library, 1964.

Churchill, Winston S. Young Winston’s Wars: The Original Despatches of Winston S. Churchill, War Correspondent 1897-1900. Ed. Frederick Woods. London: Sphere Books, 1972.

Savrola (1900)

Churchill, Winston S. Savrola: a Tale of the Revolution in Laurania. 1900. London: Beacon Books, 1957.

Churchill, Winston S. My African Journey. 1908. London: Icon Books Limited, 1964.

Folio Society: The World Crisis (1923-31)

Churchill, Winston S. The World Crisis. Introduction by Martin Gilbert. 2005. London: The Folio Society, 2007.Volume 1: 1911-1914 (1923)Volume 2: 1915 (1923)Volume 3: 1916-1918 (1927)Volume 4: The Aftermath (1929)Volume 5: The Eastern Front (1931)

Churchill, Winston S. The World Crisis: 1911-1918. 1923, 1927. Rev. ed. 1931. A Four Square Book. London: Landsborough Publications Limited, 1960.

My Early Life (1930)

Churchill, Winston S. My Early Life: A Roving Commission. 1930. The Fontana Library. London: Collins, 1959.

Marlborough: His Life and Times (1933-38)

Churchill, Winston S. Marlborough: His Life and Times. 1933, 1934, 1936, 1938. 4 vols. London: Sphere Books, 1967.

Churchill, Winston S. Great Contemporaries. 1937. The Fontana Library. London: Collins, 1965.

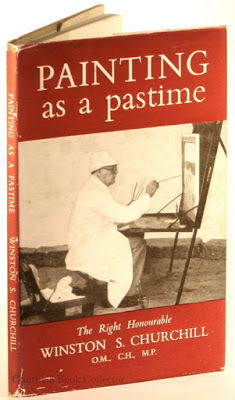

Painting as a Pastime (1948)

Churchill, Winston S. Painting as a Pastime. 1948. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1965.

The Second World War (1948-54)

Churchill, Winston S. The Second World War. Vol. 1: The Gathering Storm. 6 vols. London: Cassell & Co., Ltd., 1948.

Churchill, Winston S. The Second World War. Vol. 2: Their Finest Hour. 1949. 6 vols. London: The Reprint Society, 1951.

Churchill, Winston S. The Second World War. Vol. 3: The Grand Alliance. 1950. 6 vols. London: The Reprint Society, 1953.

Churchill, Winston S. The Second World War. Vol. 4: The Hinge of Fate. 1951. 6 vols. London: The Reprint Society, 1953.

Churchill, Winston S. The Second World War. Vol. 5: Closing the Ring. 6 vols. London: Cassell & Co., Ltd., 1952.

Churchill, Winston S. The Second World War. Vol. 6: Triumph and Tragedy. 1954. 6 vols. London: The Reprint Society, 1956.

Churchill, Winston S. The Second World War. And an Epilogue on the Years 1945 to 1957: Abridged One-Volume Edition. 1948-1954. Ed. Dennis Kelly. London: Cassell, 1959.

A History of the English-Speaking Peoples (1956-58)

Churchill, Winston S. A History of the English-Speaking Peoples. Vol. 1: The Birth of Britain. 1956. 4 vols. London: Cassell, 1972.

Churchill, Winston S. A History of the English-Speaking Peoples. Vol. 2: The New World. 1956. 4 vols. London: Cassell, 1971.

Churchill, Winston S. A History of the English-Speaking Peoples. Vol. 3: The Age of Revolution. 1957. 4 vols. London: Cassell, 1971.

Churchill, Winston S. A History of the English-Speaking Peoples. Vol. 4: The Great Democracies. 1958. 4 vols. London: Cassell, 1971.

Randolph Churchill & Martin Gilbert: Winston S. Churchill (1966-88)

Churchill, Randolph. Winston S. Churchill. Volume 1: Youth, 1874-1900. 8 vols. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1966.

Churchill, Randolph. Winston S. Churchill. Volume 2: Young Statesman, 1901-1914. 8 vols. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1967.

Gilbert, Martin. Winston S. Churchill. Volume 3: The Challenge of War, 1914-1916. 8 vols. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1971.

Gilbert, Martin. Winston S. Churchill. Volume 4: The Stricken World, 1916-1922. 8 vols. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1975.

Gilbert, Martin. Winston S. Churchill. Volume 5: Prophet of Truth, 1922-1939. 8 vols. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1976.

Gilbert, Martin. Winston S. Churchill. Volume 6: Finest Hour, 1939-1941. 8 vols. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1983.

Gilbert, Martin. Winston S. Churchill. Volume 7: Road to Victory, 1941-1945. 8 vols. William Heinemann Ltd. London: Book Club Associates, 1986.

Gilbert, Martin. Winston S. Churchill. Volume 8: Never Despair, 1945-1965. 8 vols. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1988.

Martin Gilbert: The Wilderness Years (1981)

Gilbert, Martin. Winston Churchill: The Wilderness Years. London: Macmillan London Limited, 1981.

•

Churchill (1940)

Published on June 20, 2017 14:10

June 18, 2017

Grenfell Tower

Grenfell Tower (19/6/17)

•

Grenfell Tower Block FireWe built this city on rock ‘n’ roll

– Starship

Waving two children onto the ride

ahead of youit crashes

what does that say

about divine mercy

or coincidence?

they heard them calling out

from the upper floors

as the flames rose

someone threw out a baby

someone else caught it

the others died

•

I don't usually write these sorts of topical poems - let alone publish them - but I had a strange dream the night before it happened (the first incident in the poem), and I found myself turning this out without really meaning to. Such a terrible, terrible tragedy! (I was going to say "accident", but from what's come out since, if that's what it was, then it was an accident waiting to happen ...)

Published on June 18, 2017 15:51

June 15, 2017

Spenser's Ireland

Edmund Spenser (c.1552-1599)

My friend and colleague Simon Sigley has requested a follow-up to my Malory post (below) on the subject of Edmund Spenser, author of The Faerie Queene - possibly the most famous unfinished poem in English (after The Canterbury Tales and "Kubla Khan", that is).

As luck would have it, I do possess some rather interesting bits of Spenser-iana - nothing old or valuable, you understand, but a good selection of the best contemporary editions of his works. Here they are, in any case:

Edmund Spenser: Poetical Works (1965)

Spenser, Edmund. Poetical Works. Ed. J. C. Smith & E. de Selincourt. 1912. Oxford Standard Authors. London: Oxford University Press, 1969.

The standard edition, still. Cramped, and rather hard to read, but very compendious and useful, nevertheless.

Edmund Spenser: The Faerie Queene (2007)

Spenser, Edmund. The Faerie Queene. Ed. A. C. Hamilton. 1977. Longman Annotated English Poets. London: Longman Group Limited, 1980.

Spenser, Edmund. The Faerie Queene. Ed. A. C. Hamilton. 1977. Revised Second Edition. 2001. Text edited by Hiroshi Yamashita & Toshiyuki Suzuki. Longman Annotated English Poets. Edinburgh Gate, Harlow: Pearson Education Limited, 2007.

A wonderful annotated edition, now available in a second, revised edition. (I still remember announcing with an air of triumph having found it in a second-hand shop the day before to an audience at breakfast in my Edinburgh Hall of Residence - only to be punched viciously on the arm by one of them, an Australian girl, who was working on Spenser and Blake and considered such tomes her own lawful prize! I was a little disconcerted at the time, but at least it confirmed the desirability of the find.)

Edmund Spenser: The Faerie Queene (2003)

Spenser, Edmund. The Faerie Queene. Ed. Thomas P. Roche, Jr. & C. Patrick O’Donnell, Jr. Penguin English Poets. 1978. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1979.

A good practical Penguin edition of the epic, with much more readable print, and some annotations also.

C. S. Lewis: Spenser's Images of Life (1967)

Lewis, C. S. The Allegory of Love: a Study in Medieval Tradition. 1936. London: Oxford University Press, 1970.

Lewis, C. S. English Literature in the Sixteenth Century, excluding Drama. 1954. Oxford History of English Literature. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965.

Lewis, C. S. Spenser’s Images of Life. Ed. Alistair Fowler. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1967.

You'll note the exclusivity of C. S. Lewis in the section of secondary texts. This is not so much because I think he's said the last word - or even the best - on the subject, but mainly because I have such an extension collection of his works, both imaginative and critical. Nevertheless, it is true to say that the discussion of Spenser in his classic Allegory of Love is what got me interested in The Faerie Queene in the first place.