Jack Ross's Blog, page 23

September 9, 2018

Classic Ghost Story Writers (2): Michael Cox

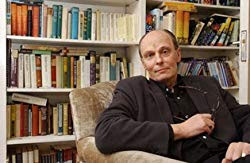

Jerry Bauer: Michael Cox (1948-2009)

Admittedly this is rather a strange follow-up to Sheridan Le Fanu, but Michael Cox gets the nod because he's such an inspiration to nerdy bookworms everywhere.

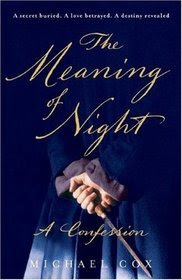

In one of those classic don't-say-it's-over-till-it's-over turn-ups for the books, Cox published his first novel in 2006, in his late fifties, after a lifetime of compiling anthologies and chronologies and other humble aids to readers, only to find it a runaway success, sold to its eventual publisher John Murray at auction for £430,000!

Is The Meaning of Night actually any good? Well, perhaps not in the absolute sense, but it's a very competent and entertaining pastiche of High Victorian Sensation Gothic, not up to the mark of Wilkie Collins or Le Fanu at their best, but clearly the fruit of passionate adoration of their works.

I suppose my main problem with it is its hero, who veers from amoral Poe-like maniac ("William Wilson") to moony lover with scant consistency. Nor can I quite see why his aristocratic ambitions are of such great interest to so many of the people he meets (a criticism which applies even more sharply to its sequel, The Glass of Time).

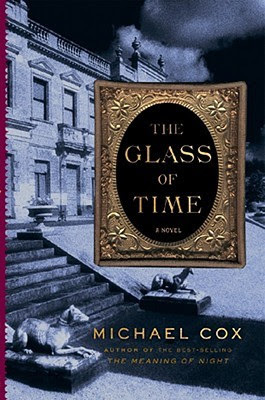

I do in many ways prefer this second novel, though: Esperanza Gorst is a far more attractive and sprightly protagonist than her whining papa - though her taste in men is a little difficult to fathom (with the best will in the world, Cox is unable to make her ghastly pompous cousin Perseus seem in the slightest degree plausible as a love interest).

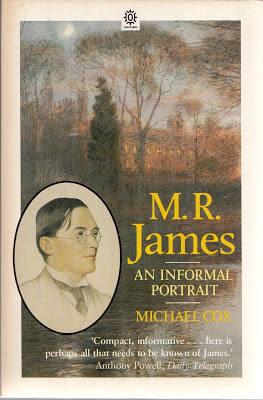

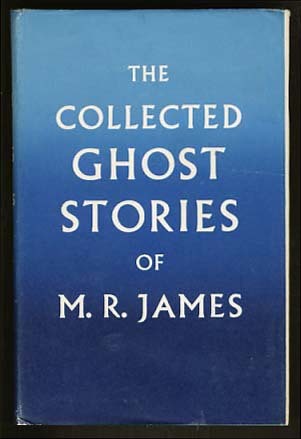

The great thing is, after editing all of those books of other people's work (including a very interesting biography of M. R. James), Cox finally nerved himself up to enter the arena himself. Then, tragically, he died of cancer a couple of years later.

Mind you, he credited his diagnosis with giving him the incentive to finish his long-meditated fiction project. Without it he might well have continued to pile up odd pages without ever finishing either book. However you take it, I think it has to be seen as a very encouraging story for all of those half-completed novels languishing in so many desk drawers. Never say die! Even without the worldwide success and the hugely swollen pre-publication price, Cox would still be a winner.

Seeing how others did it failed to intimidate him: he put himself out there, and his two books bid fair to become minor classics in their own right! Nor is his work as an editor and anthologist likely to be forgotten, either.

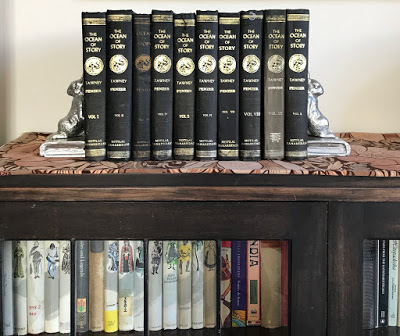

The list of his works below is not exhaustive - there are many anthologies missing: of golden age detective stories, thrillers, and a variety of other genres - but it does include all of the really significant highlights in his career as a ghost story writer and fancier (I hope):

•

Eiko Ishioka: Victorian Gothic Lolita (1983)

Michael Andrew Cox (1948-2009)

Biography:

M. R. James: An Informal Portrait (1983)

M. R. James: An Informal Portrait. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983.

Fiction:

The Meaning of Night (2006)

The Meaning of Night: A Confession. London: John Murray (Publishers), 2006.

The Glass of Time (2008)

The Glass of Time: The Secret Life of Miss Esperanza Gorst, Narrated by Herself. 2008. London: John Murray (Publishers), 2009.

Edited:

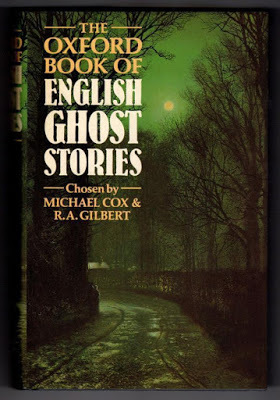

The Oxford Book of English Ghost Stories (1986)

The Oxford Book of English Ghost Stories. Ed. Michael Cox & R. A. Gilbert. 1986. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

The Ghost Stories of M. R. James (1986)

The Ghost Stories of M. R. James. Ed. Michael Cox. Illustrated by Rosalind Caldecott. 1986. London: Tiger Books International, 1991.

‘Casting the Runes’ and Other Ghost Stories (1987)

James, M. R. ‘Casting the Runes’ and Other Ghost Stories. Ed. Michael Cox. The World’s Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987.

The Illustrated J. S. Le Fanu (1988)

The Illustrated J. S. Le Fanu: Ghost Stories and Mysteries by a Master Victorian Storyteller. Equation. Wellingborough, Northamptonshire: Thorsons Publishing Group, 1988.

The Oxford Book of Victorian Ghost Stories (1991)

The Oxford Book of Victorian Ghost Stories. Ed. Michael Cox & R. A. Gilbert. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

The Oxford Book of Twentieth-Century Ghost Stories (1996)

The Oxford Book of Twentieth-Century Ghost Stories. Ed. Michael Cox. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

The Oxford Chronology of English Literature (2002)

The Oxford Chronology of English Literature. Ed. Michael Cox. 2 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Michael Cox

Published on September 09, 2018 20:02

July 25, 2018

Classic Ghost Story Writers (1): J. Sheridan Le Fanu

Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu (1814-1873)

The Perils of Green Tea

If you want to understand just why Sheridan Le Fanu stands out from all other Victorian ghost story writers, the easiest way is simply to pick up his late collection In a Glass Darkly and take it from there.

In a Glass Darkly (1872)

Of the five stories included in the book, at least three are perennial horror classics. The other two are pretty good also. They include the short novella "Carmilla," still probably the most poetic and haunting treatment of the vampire theme in existence; "The Familiar," a strangely psychological account of a haunting; "The Room in the Dragon Volant," a terrifyingly effective mystery story; "Mr. Justice Harbottle," a very original approach to the familiar theme of the haunted house, and, finally, perhaps most powerful of all, "Green Tea," where Le Fanu devises the most truly horrifying ghost in all of paranormal literature.

So much comes out of this book! Bram Stoker was greatly influenced by it. It's hard to imagine Dracula without "Carmilla" (which he in fact references directly in the associated short story "Dracula's Guest"). "Mr. Justice Harbottle," together with its 1851 analogue "An Account of Some Strange Disturbances in Aungier Street," also clearly inspired Stoker's short story "The Judge's House."

"Green Tea" is, however, sui generis. The Occult physician Martin Hesselius, whose selected papers In a Glass Darkly purports to be, certainly gifted certain of his traits to a long series of successors, including Stoker's Dr. Abraham Van Helsing (Dracula, 1897), Algernon Blackwood's John Silence (John Silence, Physician Extraordinary, 1908), William Hope Hodgson's John Carnacki (The Casebook of Carnacki the Ghost Finder, 1913), and even Aleister Crowley's Simmon Iff (The Scrutinies of Simon Iff, 1917-18). None of them came up with anything quite so worrying as the concept of "opening the interior eye" by excessive indulgence in green tea, taken late at night, however.

Mind you, Le Fanu's fiction is a pretty mixed bag. M. R. James said that Le Fanu “succeeds in inspiring a mysterious terror better than any other writer”; whereas Henry James wrote that his novels were “the ideal reading in a country house for the hours after midnight.” He may have meant that quite a few of them are likely to send you to sleep, however.

E. F. Bleiler once estimated that the proportion of mystery and detective to supernatural fiction in Le Fanu's output was something like four or five to one, and even the stories with ghostly overtones seldom commit themsalves definitively to a paranormal explanation. Human psychology was always his major preoccupation, which is why so many of them seem so startlingly - if not modern, at any rate proto-Freudian.

Uncle Silas (1864)

If you like lengthy Victorian sensation novels such as Wilkie Collins' classic The Woman in White (1859), No Name (1862), Armadale (1866), and The Moonstone (1868), however, you'll find Sheridan Le Fanu to be a worthy rival to that master of intertwined plots replete with somnambulism, stolen identity, and downright raving madness.

Uncle Silas (1864) is his one undoubted classic in this line. It's not that the plot of the book is so clever, so much as the appalling strain on the nerves built up by so much terror and suspense in so horribly confined a space. Almost all of his other books have something to be said for them, though: some individual contribution to the mystery genre.

For myself, I find the madhouse scenes in The Rose and the Key (1871) particularly effective - and while it's hard to have patience with Wylder's Hand (1864) as a whole, the strange utterances and prophecies which emanate from at least one of the minor characters lend it a particular poetic atmosphere all its own.

The Passing of J. Sheridan Le Fanu (2016)

The same characters - under different names - tend to recur almost obsessively in Le Fanu's fiction: innocent and easily affrighted young girls are one of his staples; another is a particularly reprehensible and amoral type of self-indulgent young man: Captain Richard Lake in Wylder's Hand would be one example, Sir Henry Ashwoode in his very first novel, The Cock and Anchor (1845), another.

Even though their machinations - like those of Uncle Silas himself, the epitome of this type - always come to ruin, Le Fanu seems fascinated by the mechanics of their smooth roguery. His bona fide heroes and heroines seem, by contrast, more one-dimensional and far less erotically charged. An atmosphere of erotic complication - confused gender identities and lines of attraction - is an almost invariable feature of a long Le Fanu narrative, in fact. As well as his fourteen full-length novels, he wrote many novellas and long short stories, not all of them collected to this day.

Strangely enough, although he's been canonised as a quintessentially Irish writer, only his first three novels are actually set there. All the others take place in old, off-the-beaten-track parts of England. It's hard to see that this makes much difference, though. His ancient, shadowy wooded estates really exist nowhere but in his own imagination, and that imagination remained staunchly Irish throughout his life: for the most part, though, the guilty Anglo-Irish culture of the Protestant ascendancy. It's no accident that Jonathan Swift has a walk-on part in his first novel, and that the sole topic of his conversation is his need to find a living on the other side of the Irish sea.

Le Fanu's own lifestyle was, by all accounts - at least latterly, after the death of his wife - bizarre. He wrote at night, in his grim old house in Dublin, with the help of copious doses of green tea. Like one of his own characters, he had a recurring dream that the house would come down on his head. When he was found dead one morning, at the fairly early age of 58, the doctor who examined him commented wryly that the house had fallen at last. He is reputed - though on somewhat uncertain evidence - to have died of fright.

All I can say in conclusion is that work is distinctly addictive. The more of it you read, the more appetite you feel for it. I've read about half of his novels, and am anxious to read all the others. There's something particularly satisfactory about lying in bed with what my own doctor calls "para-influenza" and reading a series of Le Fanu novellas and novels. The slightly visionary effect of the illness brings out the best in his long, convoluted - at times dreamlike - narratives.

The ghost stories, though, can be read at almost any time, in almost any mood. He was unquestionably a genius. His work may have its limitations, but is almost perfect of its kind within them. If you haven't experienced it yet, bon appétit!

Sheridan Le Fanu

Joseph Thomas Sheridan Le Fanu

(1814-1873)

The Cock and Anchor. 1845. Introduction by Herbert van Thal. The First Novel Library. London: Cassell, 1967.

The Fortunes of Colonel Torlogh O'Brien (1847)

Ghost Stories and Tales of Mystery (1851)The WatcherThe Murdered CousinSchalken the PainterThe Evil Guest

The House by the Churchyard. 1863. Introduction by Elizabeth Bowen. The Doughty Library. London: Anthony Blond, 1968.

Uncle Silas: A Tale of Bartram-Haugh. 1864. Ed. Victor Sage. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin, 2000.

Wylder’s Hand. 1864. New York: Dover, 1978.

Guy Deverell. 1865. New York: Dover, 1984.

All in the Dark. 1866. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015.

The Tenants of Malory. 1867. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015.

A Lost Name. 1868. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015.

Haunted Lives. 1868. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2012.

The Wyvern Mystery. 1869. Pocket Classics. 1994. Phoenix Mill, Far Thrupp, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Alan Sutton Publishing Limited, 2000.

Checkmate. 1871. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2016.

Chronicles of Golden Friars. 1871. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015.A Strange Adventure in the Life of Miss Laura MildmayThe Haunted BaronetThe Bird of Passage

The Rose and the Key. 1871. Pocket Classics. Phoenix Mill, Far Thrupp, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Alan Sutton Publishing Limited, 1994.

In a Glass Darkly: Stories. 1872. Introduction by V. S. Pritchett. London: John Lehmann, 1947.Green TeaThe FamiliarMr Justice HarbottleThe Room in the Dragon VolantCarmilla

Willing to Die. 1872. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015.

The Purcell Papers. 1880. Serenity Publishers, LLC, 2011. The Ghost and the Bone-Setter (January 1838) The Fortunes of Sir Robert Ardagh (March 1838) The Last Heir of Castle Connor (June 1838) The Drunkard's Dream (August 1838) A Passage in the Secret History of an Irish Countess (November 1838) The Bridal of Carrigvarah (April 1839) A Strange Event in the Life of Schalken the Painter (May 1839) Scraps of Hibernian Ballads (June 1839) Jim Sullivan's Adventures in the Great Snow (July 1839) A Chapter in the History of a Tyrone Family (October 1839) An Adventure of Hardress Fitzgerald, a Royalist Captain (February 1840) The Quare Gander (October 1840) Billy Maloney's Taste of Love and Glory (June 1850)

Madam Crowl’s Ghost and Other Tales of Mystery. Ed. M. R. James. 1923. Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Classics, 1994.Madam Crowl's Ghost (from All the Year Round , December 1870)Squire Toby's Will (from Temple Bar, January 1868)Dickon the Devil (from London Society, Christmas Number, 1872)The Child That Went with the Fairies (from All the Year Round, February 1870)The White Cat of Drumgunniol (from All the Year Round, April 1870)An Account of Some Strange Disturbances in Aungier Street (from the Dublin University Magazine, January 1851)Ghost Stories of Chapelizod (from the Dublin University Magazine, January 1851)Wicked Captain Walshawe, of Wauling (from the Dublin University Magazine, April 1864)Sir Dominick's Bargain (from All the Year Round, July 1872)Ultor de Lacy (from the Dublin University Magazine, December 1861)The Vision of Tom Chuff (from All the Year Round, October 1870)Stories of Lough Guir (from All the Year Round, April 1870)

Best Ghost Stories. Ed. E. F. Bleiler. New York: Dover, 1964.

Ghost Stories and Mysteries. Ed. E. F. Bleiler. New York: Dover, 1975.

Sheridan Le Fanu

Published on July 25, 2018 21:01

July 16, 2018

The Eleven Books of Rudyard Kipling

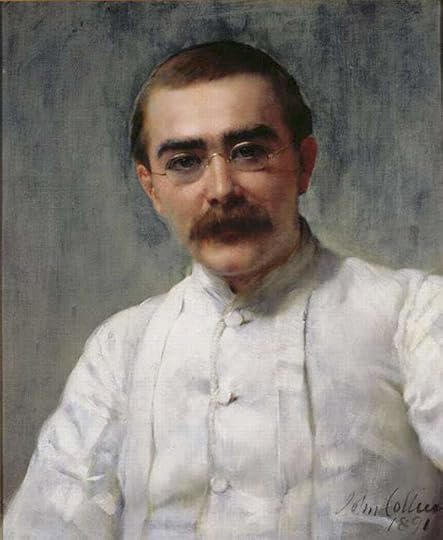

John Collier: Rudyard Kipling (1891)

"There are nine-and-sixty ways of constructing tribal lays

and - every - single - one - of - them - is - right!"

- Rudyard Kipling, 'In the Neolithic Age' (1892)

Of course Kipling wrote far more than eleven books. According to the editor of his online Collected Works, he was responsible (depending on how you count) for at least 4 novels, 351 stories, 553 poems, and 12 volumes of non-fiction.

It is, however, the eleven major books of short stories (excluding the seven collections written - at least ostensibly - for children) that I'd like to discuss here. The list below is arranged in order of publication:

Rudyard Kipling: Plain Tales from the Hills (1888)

Plain Tales from the Hills (1888)

[40 stories]

Soldiers Three / The Story of the Gadsbys / In Black and White (1888)

[24 stories]

Wee Willie Winkie / Under the Deodars / The Phantom 'Rickshaw (1888)

[14 stories]

Life's Handicap: Being Stories of Mine Own People (1891)

[28 stories / 1 poem]

Many Inventions (1893)

[14 stories / 2 poems]

The Day's Work (1898)

[12 stories]

Traffics and Discoveries (1904)

[11 stories / 11 poems]

Actions and Reactions (1909)

[8 stories / 8 poems]

A Diversity of Creatures (1917)

[14 stories / 14 poems]

Debits and Credits (1926)

[14 stories / 21 poems]

Limits and Renewals (1932)

[14 stories / 19 poems]

= 193 stories / 76 poems

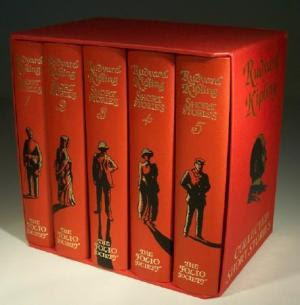

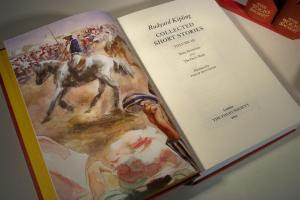

The Folio Society put out a very handsome edition of all eleven in one giant boxset a few years ago:

Rudyard Kipling: The Collected Short Stories (2005)

This set is broken up as follows:Vol.1, Plain Tales from the Hills, Soldiers Three and other storiesVol.2, Wee Willie Winkie and other stories and Life's HandicapVol.3, Many Inventions and The Day's WorkVol.4, Traffics and Discoveries, Actions and Reactions and A Diversity of CreaturesVol.5, A Diversity of Creatures (continued), Debits and Credits and Limits and Renewals

Mind you, one should probably add to this tally of published collections the volume of Uncollected Stories included in the posthumous, authorially sanctioned Sussex edition of Kipling's works. There are also a few other miscellaneous collections such as Abaft the Funnel (1909) and The Eyes of Asia (1917) to one side of his official tally of works.

Full details on the contents of all of these can be found in the supremely useful New Reader's Guide, maintained by the Kipling Society, which includes a complete list of stories, indexed alphabetically, by order of date, and by collection. This indispensable site also includes the full text of many of the stories, including such otherwise unobtainable gems as the classic "Proofs of Holy Writ" (1934), which has never been separately reprinted.

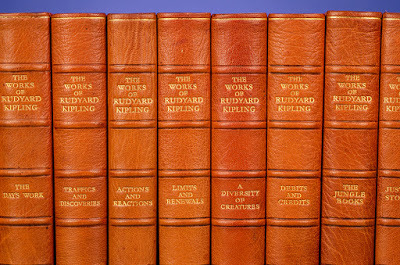

Rudyard Kipling: Sussex Edition (35 volumes: 1937-39)

The stories divide fairly readily into a few well-defined groups. "Kipling," as we know him, started with the remarkable spurt of stories created and published in India, then collected in a set of seven small Indian Railway paperbacks there in 1888:

Plain Tales from the HillsSoldiers ThreeThe Story of the GadsbysIn Black and WhiteWee Willie WinkieUnder the DeodarsThe Phantom 'RickshawThe extraordinary variety and accomplishment of these stories literally - and almost unprecedentedly - put him on the world literary map. Contemporary readers appear to have been most struck by the Maupassant-influenced Plain Tales from the Hills, but probably modern readers will find the insights into race relations in the small collection In Black and White of more enduring interest, and certainly far from the cliché of blind and jingoistic imperialism he's now unfortunately (though not, alas, entirely unjustifiably) identified with.

Next we come to the later Indian and transitional stories, published throughout the 1890s, though with a gradually increasing admixture of American and British settings, dictated by his various places of residence during that decade.

Life's HandicapMany InventionsThe Day's WorkThe stories here are becoming longer and more ingenious, and include a number of experiments in different voices, both animate ("The Children of the Zodiac," "A Walking Delegate") and inanimate (".007," "The Ship that Found Herself"). For the most part, however, they maintain the immediacy of his Indian work, and are seem by many as the summit of his achievement in the form.

After this we move to (so-called) "late Kipling":

Traffics and DiscoveriesActions and ReactionsA Diversity of CreaturesDebits and CreditsLimits and RenewalsThese collections are marked by an intermixture of verse and prose. Most of the stories are preceded or followed by poems which make veiled and far from straightforward comments on their themes and contents. Their style is more oblique and self-consciously "experimental" - sometimes to the point of extreme obscurity and even (presumably deliberate) bafflement.

Just what is the point of "Mrs Bathurst," from Traffics and Discoveries, for instance? Jorge Luis Borges and Paul Theroux debated it during the latter's visit to the former in Buenos Aires (according to Theroux's 1979 travel book The Old Patagonian Express, at any rate). It's a story of particular interest to New Zealanders, given the fact that the bar Mrs Bathurst keeps is in "Hauraki," a small (fictional) town just outside Auckland. The story's other settings include Cape Town and a London train station, in keeping with its themes of human loyalty versus machine-made division and alienation.

These later stories are probably now Kipling's main claim to fame as a writer - as anything but an historical curiosity, that is. The extreme obliquity of their technique, the obsessive use of the recondite jargon of trades, and of multiple levels of narration, certainly place him among the more technically accomplished - and tirelessly innovative - masters of the short story in English.

The last three of these collections constitute a kind of sub-group, dominated by the shadow of the Great War, which added the final ingredient of horror and despair at the waste of a civilisation which we tend to associate with modernists such as Eliot and Woolf. Kipling's late work does not really resemble theirs either in tone or content, but it certainly rivals it in depth and seriousness.

Many other points could be made about Kipling, but the variety and accomplishment on display in these eleven books certainly negate any facile attempts to denigrate him as some kind of also-ran, inferior in subtlety to either Conrad or James. They took him seriously, and so should we.

His fascination with the extreme edges of human psychology, ranging off into the paranormal (a subject of particular interest to him from his very first Poe-influenced stories - such as 'The Strange Ride of Morrowbie Jukes' - to such late masterpieces as 'Wireless' or 'The House Surgeon') provided strange fuel for these last war-shadowed books. In stories like 'The Janeites' or 'The Gardener,' a sense of common humanity and compassion began to emerge, finally, from the man whose adoration of bullies and imperialists had earlier threatened to align him, almost, with Fascism.

Perhaps Kipling's popularity will, in future, be forced to rely on his almost equally ingenious - and rather more charming - children's books: The Jungle Books, Puck of Pook's Hill, and The Just So Stories. These are by no means devoid of politics and his own strange brand of Manichaean extremism, but they need not be read with these things in mind. Who, having experienced them in childhood, can ever subsequently forget the adventures of Mowgli or Rikki-Tikki-Tavi?

It would be a shame to pass by these 11 superb collections of stories, however, without understanding that they do collectively constitute his testament to posterity as a creative writer.

Rudyard Kipling: Traffics and Discoveries (1904)

One of the most interesting teaching experiences I've ever had came when I was discussing the story 'They' with an Honours English class at Edinburgh. They allowed some of us graduate students to acquire a bit of (unpaid) teaching practice, and I'd been allotted a class in Edwardian and pre-war fiction.

'They,' if you haven't read it (and who nowadays has?) is a story about a blind woman who lives in a house full of ghost children whom she is unable to see and therefore able to postulate as 'real' and 'alive.' The narrator can also see them - as it turns out, because he has lost a child himself, and is therefore attuned to their vibrations (or so one assumes). When he finally realises that the children are all ghosts, he self-exiles himself from the house, explaining to her that it is fine for her to live with them, but not for him: perhaps because, being childless, none of them are actually flesh of her flesh.

This theme of lost children is strong in Kipling, both before and after the war, in which he lost his only son in tragic circumstances (Kipling had pulled strings with his influential friends to allow the short-sighted 'Jack' to enlist, and thus blamed himself when he died in a particularly futile attack on the Western front).

Now my class refused to believe that the children in the story were ghosts. They saw them as illegitimate children from the village. When I asked them why, in that case, the narrator thought it improper for him to spend more time there, they attributed this to snobbery and class privilege on his part.

Given the elusive, allusive style of Kipling's late stories, it's hard to find direct textual authority for a particular reading of any passage. I nevertheless attempted to persuade them that they weren't reading carefully enough, and were eliding over any number of passages to maintain their own reading. They riposted that that was simply my opinion, and that they had just as much right to theirs.

I guess I've been conducting that thirty-year-old argument in my head ever since. It was the age of reader response and Stanley Fish's notoriously provocative book Is There a Text in This Class? Certainly, in their eyes, I represented the past of 'authoritative,' 'agreed-upon' textual opinions, maintained by force of hierarchy rather than by argument. To me they seemed addicts of simplistic under-reading, determined to take the line of least resistance in each case.

Late Kipling is like that, though, as I found again recently when arguing with another student about the true 'meaning' of his armistice story 'The Gardener.' Is the grave the protagonist is trying to find that of her own illegitimate son, or is the true tragedy of the story the fact that he is her true son (through love and upbringing) but not in the physical sense? I've always leaned towards the latter reading, while most people assume that the former, more obvious reading is the one to go for.

Does this shadowy indeterminacy make his stories better or worse? The fact that they continued to hold the attention of Borges in his blindness would imply the former. And yet it's hard to know if it isn't simply one's own obtuseness which withholds a 'final' reading of each one. 'Dayspring Mishandled,' 'The Woman in His Life,' 'My Son's Wife' - such stories constitute an amazing legacy. Nobody ever really wrote like Kipling, early or late, and it's hard to foresee such a body of work ever being seen as obsolete - except, of course, by those most unanswerable of critics, those who haven't actually read him in depth.

Rudyard Kipling: Debits and Credits (1926)

*

Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling

(1865-1936)

Collections:

Kipling, Rudyard. The One Volume Kipling: Authorized. 1893 & 1928. New York: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1930.Volume I: Ballads and Barrack-Room BalladsVolume II: The Light that FailedVolume III: City of Dreadful NightVolume IV: Plain Tales from the HillsVolume V: Soldiers ThreeVolume VI: Mine Own PeopleVolume VII: In Black and WhiteVolume VIII: The Phantom 'Rickshaw & Other Ghost StoriesVolume IX: Under the DeodarsVolume X: Wee Willie WinkieVolume XI: The Story of the GadsbysVolume XII: Departmental Ditties and Other Verses

Poetry:

Carrington, Charles, ed. The Complete Barrack-Room Ballads of Rudyard Kipling. 1892. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1973.

Kipling, Rudyard. The Seven Seas. 1896. The Dominions Edition. London: Methuen & Co., Limited, 1914.

Kipling, Rudyard. The Five Nations. 1903. The Dominions Edition. 1914. London: Methuen & Co., Limited, 1916.

Kipling, Rudyard. Rudyard Kipling’s Verse: Definitive Edition. 1912. Second Edition. 1919. Third Inclusive Edition. 1927. Fourth Inclusive Edition. 1933. Definitive Edition. 1940. London: Hodder and Stoughton Limited, 1945.

Kipling, Rudyard. A Choice of Kipling's Verse. Ed. T. S. Eliot. 1941. Faber Paper Covered Editions. London: Faber, 1963.

Rutherford, Andrew, ed. Early Verse by Rudyard Kipling, 1879-1889: Unpublished, Uncollected, and Rarely Published Poems. 1986. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.

Novels:

Kipling, Rudyard. The Light that Failed. 1891. Macmillan’s Colonial Library. London: Macmillan & Co. Limited, 1891.

Kipling, Rudyard, & Wolcott Balestier. The Naulahka: A Story of West and East. 1892. 2 vols. The Service Edition of the Works of Rudyard Kipling. London: Macmillan & Co., Limited, 1915.

Kipling, Rudyard. ‘Captains Courageous’: A Story of the Grand Banks. 1896. Melbourne & London: Macmillan & Company Ltd., 1942.

Kipling, Rudyard. Kim. 1901. London: Macmillan & Co. Limited, 1940.

Short Stories:

Kipling, Rudyard. Plain Tales from the Hills. 1888. The Dominions Edition. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1913.

Kipling, Rudyard. Soldiers Three / The Story of the Gadsbys / In Black and White. 1888 & 1895. The Dominions Edition. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1913.

Kipling, Rudyard. The Phantom 'Rickshaw and other Tales. 1888 & 1895. New York: American Publishers Corporation, n.d.

Kipling, Rudyard. Wee Willie Winkie: Under the Deodars / The Phantom Rickshaw and other Eerie Tales / Wee Willie Winkie and Other Child Stories. 1888 & 1895. Ed. Hugh Haughton. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1988.

Kipling, Rudyard. Life's Handicap: Being Stories of Mine Own People. 1891. Ed. P. N. Furbank. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1987.

Kipling, Rudyard. Many Inventions. 1893. The Dominions Edition. London: Macmillan & Co. Limited, 1913.

Kipling, Rudyard. The Day's Work. 1898. The Dominions Edition. London: Macmillan & Co., Limited, 1913.

Kipling, Rudyard. Traffics and Discoveries. London: Macmillan & Co. Limited, 1904.

Kipling, Rudyard. Actions and Reactions. 1909. Macmillan’s Pocket Kipling. London: Macmillan & Co. Limited, 1920.

Kipling, Rudyard. A Diversity of Creatures. 1917. The Medallion Edition. Dunedin: James Johnston, Limited / London: Macmillan and Co. Limited, n.d.

Kipling, Rudyard. Debits and Credits. The Dominions Edition. London: Macmillan & Co. Limited, 1926.

Kipling, Rudyard. Limits and Renewals. 1932. Ed. Phillip V. Mallett. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1987.

Kipling, Rudyard. Ten Stories. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1947.

Kipling, Rudyard. A Choice of Kipling's Prose. Ed. W. Somerset Maugham. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1952.

Kipling, Rudyard. Short Stories. Volume 1: A Sahib’s War and Other Stories. Ed. Andrew Rutherford. 1971. Penguin Modern Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1977.

Kipling, Rudyard. Short Stories. Volume 2: Friendly Brook and Other Stories. Ed. Andrew Rutherford. 1971. Penguin Modern Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1977.

Children's Stories:

Kipling, Rudyard. The Jungle Books. 1894 & 1895. Illustrated by Stuart Tresilian. 1955. London: the Reprint Society, 1956.

Kipling, Rudyard. The Brushwood Boy. 1895 & 1899. Illustrations by F. H. Townsend. 1907. London: Macmillan & Co., Limited, 1914.

Kipling, Rudyard. Stalky & Co.: Complete. 1899. Ed. Isabel Quigley. The World’s Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Kipling, Rudyard. Just So Stories for Little Children: A Reprint of the First Edition. Illustrated by the Author. 1902. New York: Weathervane Books, 1978.

Kipling, Rudyard. Puck of Pook's Hill. 1906. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1957.

Kipling, Rudyard. Rewards and Fairies. 1910. Macmillan’s Pocket Kipling. London: Macmillan & Co. Limited, 1920.

Kipling, Rudyard. Land & Sea Tales for Scouts and Guides. 1923. London: Macmillan & Co. Limited, 1923.

Kipling, Rudyard, ed. Thy Servant a Dog, Told by Boots. Illustrated by G. L. Stampa. 1930. London: Macmillan & Co. Limited, 1931.

Kipling, Rudyard. Animal Stories from Rudyard Kipling. Illustrated by Stuart Tresilian. 1932. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1961.

Kipling, Rudyard. All the Mowgli Stories. 1933. St. Martin’s Library. 1961. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1962.

Non-Fiction:

Kipling, Rudyard. From Sea to Sea and Other Sketches: Letters of Travel. 1899. 2 vols. Macmillan’s Pocket Kipling. London: Macmillan & Co. Limited, 1914.

Kipling, Rudyard. Sea Warfare. The Dominions Edition. London: Macmillan & Co. Limited, 1916.

Kipling, Rudyard. Letters of Travel (1892-1913). Macmillan’s Pocket Kipling. London: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1920.

Kipling, Rudyard. A Book of Words: Selections from Speeches and Addresses Delivered Between 1906 and 1927. London: Macmillan & Co. Limited, 1928.

Kipling, Rudyard. Something of Myself: For My Friends Known and Unknown. 1937. Ed. Robert Hampson. Introduction by Richard Holmes. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1987.

Secondary:

Gilbert, Elliot L., ed. “O Beloved Kids”: Rudyard Kipling’s Letters to his Children. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson., 1983.

Green, Roger Lancelyn. Kipling and the Children. London: Elek Books Ltd., 1965.

Carrington, Charles. Rudyard Kipling: His Life and Work. 1955. London: Macmillan Limted, 1978.

Published on July 16, 2018 14:44

July 11, 2018

Pessoa World

Pessoa & Jack (Café A Brasileira, Lisbon: 26/6/18)

All photos (unless otherwise specified): Bronwyn Lloyd

So, if the song "Starry, Starry Night" is all about Vincent Van Gogh, did it ever strike you that the ABBA song "Fernando" might really be about the Portuguese poet (and ubiquitous cultural icon) Fernando Pessoa? The evidence, admittedly, is somewhat scanty, but when did that ever get in the way of a good piece of literary detective work?

"Fernando" is a somewhat shadowy figure in the song, repeatedly addressed by the speaker, but in a somewhat equivocal way, as if he were not so much an old comrade as an agent provocateur - perhaps the very one who, by betraying their secrets, guaranteed the loss of their cause? "Though we never thought that we could lose / there's no regret," Agnetha is careful to say. Really? Or is that simply a subterfuge designed to put the treacherous "Fernando" off the scent? I've often wondered ...

Mind you, I don't insist on this conjecture - simply mention it in order to underline just how slippery and subversive this Pessoa (Portuguese for "person" - our hotel had a notice specifying that only 13 "pessoas" were allowed in the lift at one time) can be.

Take the Casa Fernando Pessoa itself, for instance (Coelho da Rocha 16, 1250-088 Lisboa, Portugal):

Casa Pessoa: exterior (30/6/18)

It could not be said to be particularly easy to find: our cab driver had to crawl along the street for quite some time before we stumbled across it.

Casa Pessoa: vestibule (30/6/18)

Once in, however, Pessoa's status as king of the heteronyms is not left in any doubt (for those of you who aren't in the know, Pessoa is famous for evolving a series of parallel identities, or heteronyms, in whose respective voices he wrote a great deal of his oeuvre).

Casa Pessoa: bedroom (30/6/18)

Here is the poet's bed (or, more probably, a reasonable facsimile of same - while he did indeed reside in this house at some stage, little physical evidence of his presence there remains behind).

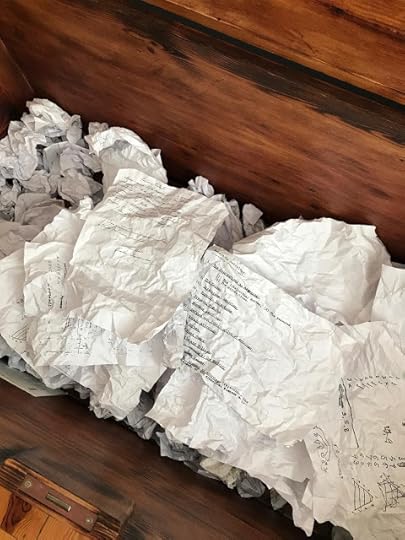

Casa Pessoa: the chest (30/6/18)

This chest definitely is a fake: or, rather, a simulacrum of the famous - and apparently inexhaustible - repository of the mass of unpublished manuscripts he was found to have bequeathed to posterity at his death.

Casa Pessoa: manuscripts (30/6/18)

Whatever they actually looked like, I bet it wasn't like this. Thousands of pages are alleged to have been crammed into this much storied artefact.

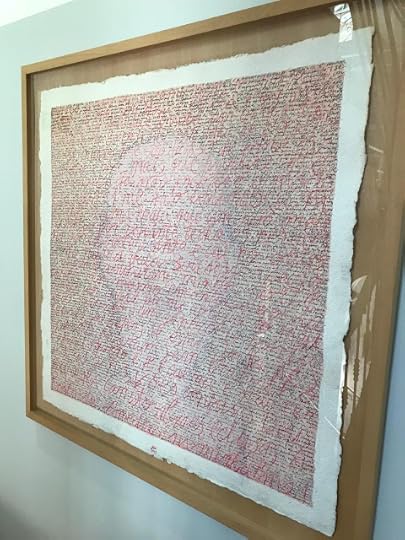

Casa Pessoa: embroidery portrait (30/6/18)

This picture seems to capture something of his peculiar elusiveness as a person (pun intended). It's a piece of embroidery, rather than a painting, so it must have taken an appallingly long time to make.

Casa Pessoa: palimpsest (30/6/18)

This rather more fanciful portrait posits him as a purely textual phenomenon: a creature of words rather than flesh and blood.

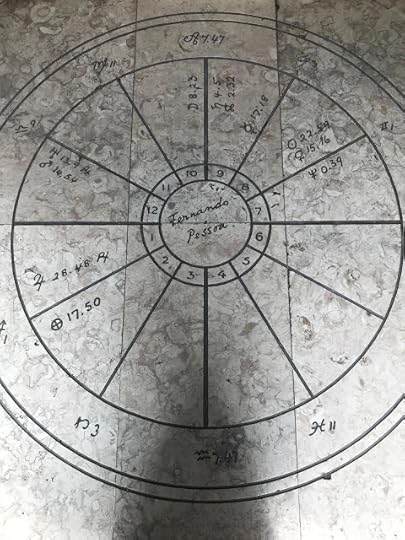

Casa Pessoa: horoscope (30/6/18)

And here's the poet's horoscope (note how Bronwyn, the photographer, has cunningly inserted herself into the composition as a looming shadow).

Casa Pessoa: library (30/6/18)

Here's a shot of the multiple flying Pessoas who infest the Casa's library. I'm not quite sure how these Mary Poppins-like mannequins are supposed to represent him, but they certainly do look rather striking.

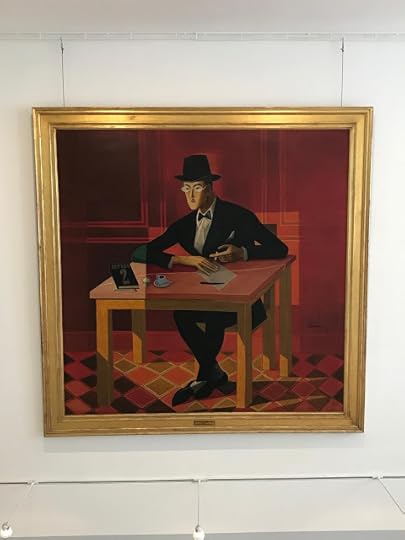

Casa Pessoa: portrait (30/6/18)

And here's one of the most famous paintings of the poet, scribbling industriously in - presumably - the Café A Brasileira now adorned by his statue nestled among the tables outside.

Manuel Amado: Fernando Pessoa's Bedroom I & II (1993)

These two paintings of the view out of his window by day and by night seemed to us the most effective in conveying the strange contrariness of his existence. I don't quite know why they seem so sad to me, so redolent of that peculiar Portuguese quality called saudade, but there they are. I don't know what was portrayed in the third of the group, but its absence makes these two seem even more haunting and thwarted, I feel.

•

Fernando Pessoa: Obras (1986)

Having reached an apparent impasse in tracing his steps through the streets of Lisbon, perhaps the best way to come to terms with this most unstable and equivocal of multiple personalities must be through the comparative solidity of the written word?

The three volumes above, published for the fiftieth anniversary of his death, constitute one of the last attempts to compile a reasonably systematic collected works for the poet. Thereafter everything fragmented into the (more-or-less) complete works of this or that literary persona of his. He has become, in the truest sense, a library rather than a human being.

Nevertheless, there are really only three (or perhaps four) major heteronyms one needs to take account of:

João Luiz Roth: Álvaro de Campos (1890-1935)

Álvaro de Campos is an expansive, Whitman-esque poet of global distances and imperial expansion. In his last phase melancholy overcame him, but he is in many ways the most attractive and accessible of Pessoa's different voices.

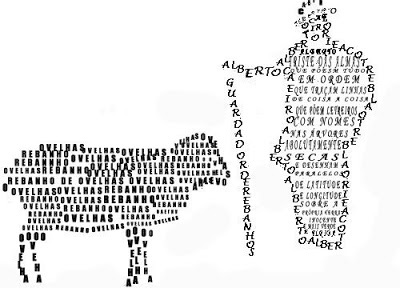

Alberto Caeiro (1889-1915)

Alberto Caeiro, the "keeper of sheep," is more of a pantheist - solitary, nature-loving, and (alas) short-lived, he has something about him of a Portuguese A. E. Housman.

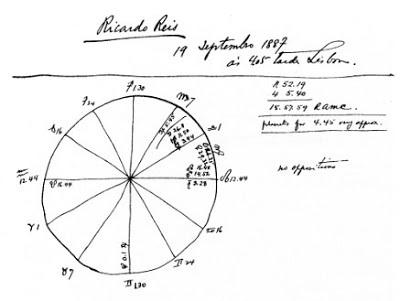

Fernando Pessoa: Ricardo Reis: astrological chart (1887-?)

Ricardo Reis is more of a classicist - and pessimist - than either of his predecessors. The fact that he had no designated time of death led Portugal's other great twentieth-century author, José Saramago, to imagine him as an abandoned spirit, wandering listlessly about Lisbon searching for the remaining vestiges of his creator, in the novel The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis.

Saramago, José. The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis. 1984. Trans. Giovanni Pontiero. 1991. The Harvill Press. London: The Random House Group Limited, 1999.

Bernardo Soares (1890-1935)

Bernardo Soares, the book-keeper, is a prose-writing 'semi-heteronym,' principally responsible for perhaps his most famous work, The Book of Disquiet, first published in 1982, and subsequently edited and re-edited, translated and re-translated in a bewildering variety of versions, each (allegedly, at least) more 'complete' than the last.

Here's are some of the versions available in English: The Book of Disquiet. Ed. Maria José de Lancastre. Trans. Margaret Jull Costa. 1991. Introduction by William Boyd. Serpent's Tail Classics. London: Profile Books Ltd., 2010.The Book of Disquiet. Trans. Alfred Mac Adam, New York: Pantheon Books, 1991.The Book of Disquiet. Trans. Iain Watson. London: Quartet Books, 1991.The Book of Disquietude, by Bernardo Soares, assistant bookkeeper in the city of Lisbon. Trans. Richard Zenith. 1991. New York: Sheep Meadow Press, 1996.Pessoa, Fernando. The Book of Disquiet. Ed. & Trans. Richard Zenith. Penguin Modern Classics. London: Penguin, 2001.Pessoa, Fernando. The Book of Disquiet: The Complete Edition. Ed. Jeronimo Pizarro. 2013. Trans. Margaret Jull Costa. New York: New Directions Publishing, 2017.

•

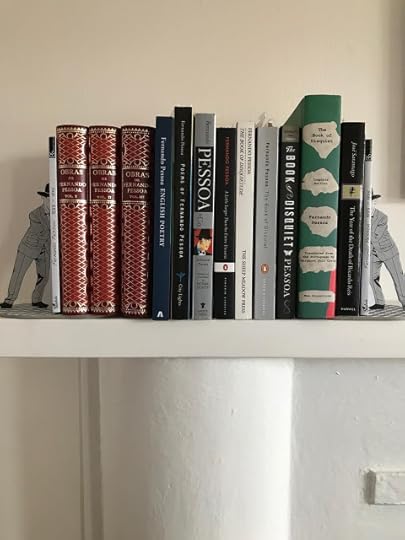

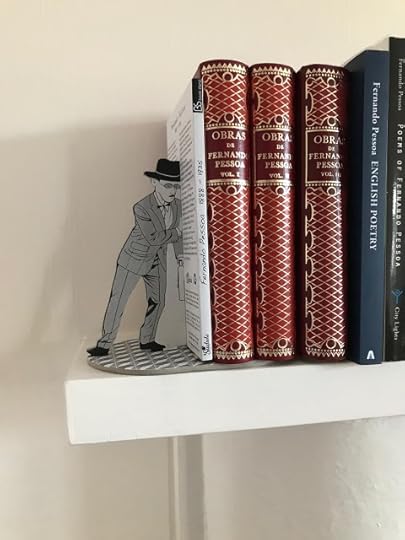

There's a bewildering range of kitschy Pessoa memorabilia in virtually every gift shop in Portugal: t-shirts, mugs, fridge magnets, tote-bags, and ... book-ends. The latter I found irresistible, I must confess:

Pessoa Bookends

And here's my own mini-collection of Pessoa-iana, in all its glory. You may notice a preponderance of translations by Richard Zenith, but he does have the (self-proclaimed) virtue of trying to make sure that his various selections from the poet's works do not overlap too substantially with one another (or even with other translator's selections). So even though you already own one of his books, you more or less have to buy the others.

Pessoa Bookends: left

Fernando António Nogueira de Seabra Pessoa

(1888-1935)

Pessoa, Fernando. Obra Poética e em Prosa. Ed. António Quadros & Dalila Pereira da Costa. 3 vols. Porto: Lello & Irmão - Editores, 1986.

Pessoa, Fernando. Poems of Fernando Pessoa. Trans. Edwin Honig & Susan M. Brown. 1971 & 1986. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1998.

Pessoa, Fernando. Selected Poems. Trans. Jonathan Griffin. Penguin Modern European Poets. Ed. A. Alvarez. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1974.

Pessoa, Fernando & Co. Selected Poems. Ed. & trans. Richard Zenith. New York: Grove Press, 1998.

Pessoa, Fernando. A Little Larger Than the Entire Universe: Selected Poems. Ed. & trans. Richard Zenith. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin, 2006.

Pessoa, Fernando. English Poetry. Ed. Richard Zenith. Documenta poetica, 154. Assírio & Alvim. Porto: Porto Editora, 2016.

Pessoa Bookends: right

So what does it all add up to, this brief excursus through the wonderful world of Fernando Pessoa? "If I could tell you, I would let you know" (to quote W. H. Auden). There's something delightful about his single-minded pursuit of multifarious fragmentedness, as well as in the way Portugal has decided to celebrate him as their greatest poet since the sixteenth-century epic bard Luís de Camões.

On the other hand, there's undoubtedly something depressing in the fact that all this acclaim surfaced only long after his death - and an unmistakable atmosphere of neglect and self-deluding monomania still seems to hang about his head despite it all. He's somewhat of a joke in 'serious' Portuguese literary circles, one local Academic confided to me at the short story conference to which I'd just contributed a paper entitled "Pessoa Down Under," about the local Australasian manifestations of his pervasive influence.

Joke or not, Pessoa is here to say. And if you don't think much of his poetry in translation, well, which writer is it that you're really judging? There are enough of them in there for anyone, I would have thought, and enough collected works to last us till the cows - or, in this case, sheep - come home.

Camões & Jack - in silly hat

(Praça Luís de Camões, Lisbon: 26/6/18)

•

Published on July 11, 2018 14:32

May 30, 2018

Can Poetry Save the Earth?

Our Changing World: Public Lecture Series

(Albany Campus, Massey University, 2018)

What the ...? Of course not, I hear you say. And, naturally, I have a good deal of sympathy with this view. I took the title from Paul Celan-biographer John Felstiner's intriguingly named book Can Poetry Save the Earth?: A Field Guide to Nature Poems. My unfortunate colleagues Jo Emeney and Bryan Walpert have been forced to live with it.

John Felstiner: Can Poetry Save the Earth?: A Field Guide to Nature Poems (2009)

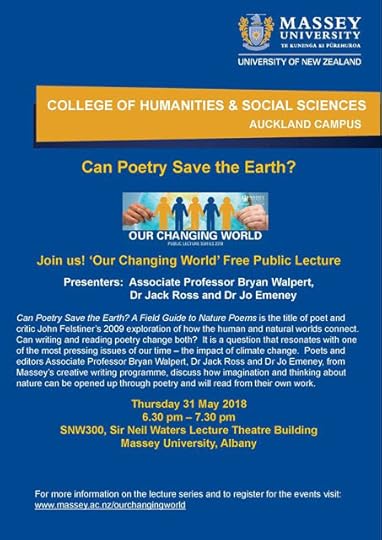

This particular public lecture is by all three of us, you see, but unfortunately I was the one who sent in the rubric for it, some time in the balmy summer days of last year, when all such tiresome things seemed an awful long way off. Now, alas, it's hard upon us:

Not only that, but this:

Watch onlineThese public lectures are available to view online via webcasts.

If you can’t join us in person, why not join online?

Watch Webcast Live via these links

(will be stored so can also be watched after the event):

https://t.co/QDcbKgvkKw

Here's yet another announcement from the Massey website:

Can poetry save the Earth? Thursday 31 May 2018 | Associate Professor Bryan Walpert, Dr Jack Ross, Dr Jo Emeney

Can Poetry Save the Earth? A Field Guide to Nature Poems is the title of poet and critic John Felstiner's 2009 exploration of how the human and natural worlds connect. Can writing and reading poetry change both? It’s a question that resonates with one of the most pressing issues of our time – the impact of climate change. Poets and editors Associate Professor Bryan Walpert, Dr Jack Ross and Dr Jo Emeney, from Massey’s creative writing programme, discuss how imagination and thinking about nature can be opened up through poetry and will read from their own work.

And here's the text of an article our wonderful communications director Jennifer Little wrote about the whole extravaganza:

Can poetry save the Earth?

Can reading, writing and studying poetry have any relevance to how we think about and respond to increasingly grim environmental issues? A trio of award-winning poets, editors and creative writing lecturers from the School of English and Media Studies will share their ideas on this intriguing notion in a public lecture.

In Can poetry save the Earth? (Thursday 31 May at 6:30pm), Associate Professor Bryan Walpert, Dr Jack Ross and Dr Jo Emeney will explore the idea that writing and reading poetry can connect us to the natural world in a way that resonates with one of the most pressing issues of our time – the impact of climate change.

They will discuss how imagination and thinking about nature can be opened up through poetry, and will read their own and others’ work – from home grown greats such as Hone Tuwhare and Brian Turner to American poet Robert Frost and Romantic English poet John Clare. It is the fourth of ten free public lectures in the 2018 Our Changing World series, featuring speakers from the College of Humanities and Social Sciences.

They’ve borrowed their lecture title from Can Poetry Save the Earth? A Field Guide to Nature Poems - poet and critic John Felstiner's 2009 exploration of how the human and natural worlds connect.

While Felstiner may have intended just to give his book a catchy title, “Poetry and poets can use their sway to agitate for change. Why else would so many of us be put in prison?” says Dr Emeney.

“I can think of at least one example where the use of a chemical pesticide (DDT) was banned across the United States as a direct result of a book on the subject written by a poet.”

“I think Felstiner chose the title in a teasing way, since it's so obvious that poetry can't save the Earth. It gets more interesting when you start to question ‘why not’, though,” says Dr Ross. “Why couldn't it at least help? Doesn't poetry - by its nature - suggest certain attitudes which might be of value in keeping us alive?”

“I don’t think a particular poem is likely to save the Earth,” Dr Walpert says, “but I think that poetry as a whole can have an important effect on the way we think about the problems around us.”

Eco-poetry voices 21st century concerns

While there are and always have been ‘nature poets’, there’s now a complete school of thought, with learned journals, anthologies, and growing bodies of work called ‘eco-poetry,’ says Dr Ross.

He and Bryan have co-supervised a PhD thesis in this relatively new, cross-disciplinary field. “I don't see how one can be a poet and not be aware of your environment, regardless of what that awareness actually means or constitutes,” he says.

“Poetry is about respect, about making sure that in future we listen more carefully to the voices who've been warning about this for so long: before Rachel Carson [ecological prose poet and author of the ground-breaking 1962 environmental science book Silent Spring], even, and all the way back to John Clare [19th century English poet) and [Romantic English poet and painter] William Blake (those 'dark satanic mills’).

“Perhaps in the current context,” says Dr Walpert, “at a time when we are so overwhelmed with digital waves of language and such a public experience of it, much of it without nuance – private experiences of language that take more than a few seconds to read, that bear re-reading, and that embrace complexity have a particular value.”

Bios

Dr Jo Emeney has written two poetry collections: Apple & Tree (Cape Catley 2011), and Family History (Mākaro Press 2017), as well as a recent nonfiction book, The Rise of Autobiographical Medical Poetry and the Medical Humanities(ibidem Press 2018).

Dr Jack Ross is managing editor of Poetry New Zealand, New Zealand’s oldest poetry journal (now published by Massey University Press), as well as author of several poetry collections, including A Clearer View of the Hinterland (2014).

Associate Professor Bryan Walpert has published several collections of poetry in the US, the UK and New Zealand, most recently Native Bird (Makaro Press); a collection of short fiction, Ephraim’s Eyes, which includes the short story, 16 Planets, that won the climate change themed Royal Society of New Zealand Manhire Award for fiction. He’s also written two scholarly books on poetry, Resistance to Science in Contemporary American Poetry and the recently published Poetry and Mindfulness: Interruption to a Journey.

Lecture details:

Can poetry save the Earth? 31 May, 6.30pm: Sir Neil Waters Lecture Theatre (SNW300), Massey University Auckland campus, Albany.

Register at massey.ac.nz/ourchangingworld

If all that hasn't put you off, feel free to put in an appearance tonight at the lecture. Failing that, you can see the poems I'm going to be reading as well as the images from my powerpoint here, on my Papyri website. (Hint: it's likely to involve both Paul Celan and John Clare):

Gisèle Celan-Lestrange (1927-1991): "Etching"

Published on May 30, 2018 16:43

May 13, 2018

Isherwood

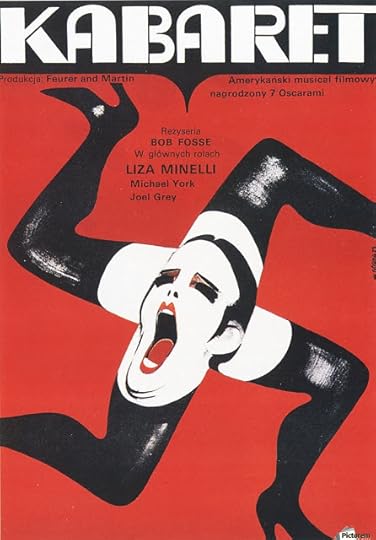

Wiktor Gorka: Cabaret (1972)

My initially tepid interest in Christopher Isherwood started off as a by-product of a far more serious Auden obsession. Isherwood was a close friend (indeed occasional lover) and collaborator of Auden's, who also wrote a lot about him, therefore - I needed to collect all of his books.

Howard Coster: Auden & Isherwood (1937)

That is, in a nutshell, pretty much how a bibliophile's mind works. You start off collecting one thing, but then you have to start a series of sub-collections to flesh out the context of your object of desire (whatever it may be: poetry, military history, the 1001 Nights ...).

The result, twenty or thirty years later, is a living space stuffed to the gills with books and pictures and boxfiles of papers. Freud had a name for it, I'm afraid: the anal-retentive personality. Speaks for itself, really. But it does make for interesting times when you actually get around to reading some of the results of this fixation.

In this particular case, I've just finished reading through Isherwood's immense diary, published in four volumes between 1996 and 2012, in an edition scrupulously edited by Auden scholar Katherine Bucknell.

Of course, the picture above reveals just why Isherwood is really famous: because his Berlin stories inspired John Van Druten's play "I am a Camera," which, in its turn, morphed into the smash-hit Broadway musical turned multiple Oscar-winning film Cabaret. In other words, he's most celebrated for two things he didn't write himself, and didn't even particularly approve of (though he was happy to cash the cheques they earned him).

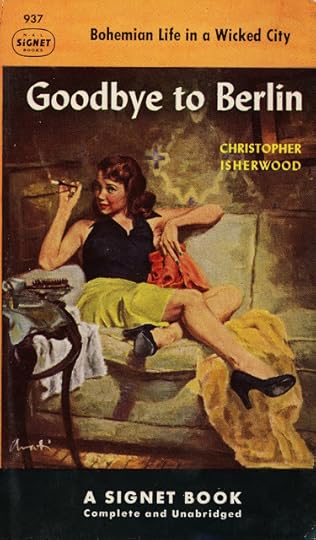

Christopher Isherwood: Goodbye to Berlin (1939)

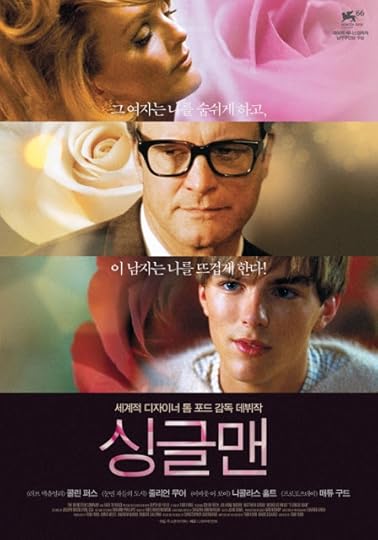

A rather more accurate portrait of Isherwood was provided by Tom Ford's 2009 film A Single Man. This is at least as autobiographical as the Berlin stories - which is to say, not very - but succeeds in giving an impression (at least) of where he ended up: a gay man stuck in a repressed, heterosexual world which he will never be allowed to fit into. (You'll notice that I had to go pretty far afield to find a version of the film poster which didn't imply that it concerned some kind of 'straight' romance between Colin Firth and Julianne Moore).

Tom Ford, dir. A Single Man (2009)

There were a number of ways in which Isherwood was outrageous, of course. Not just the homosexuality, which he grew increasingly outspoken about as he grew older (and the threat of imprisonment receded); there was also his alleged 'cowardice' in 1939, when he and Auden chose to go and settle in America rather than staying to face the music in beleaguered Britain. Vast amounts of ink were spilt at the time condemning - and justifying - this decision. Auden subsequently explained it by saying that he did it precisely to avoid writing any more poems like "September 1, 1939" or "Spain 1937" - anthemic calls to action of a kind which he subsequently regarded as dishonest and untruthful.

Isherwood, by contrast, was no stranger to running away. He'd had himself sent down from Cambridge when he felt he was at risk of acclimatising to its stuffy attitudes by composing the answers to his exams as concealed limericks. He'd subsequently left for Berlin, Greece, and a series of other refuges from the upper-class English background he feared being swallowed up by. California was intended as just one more bolthole, but it was there he got religion and found love (in that order), and where, therefore, he settled for what turned out to be the rest of his life.

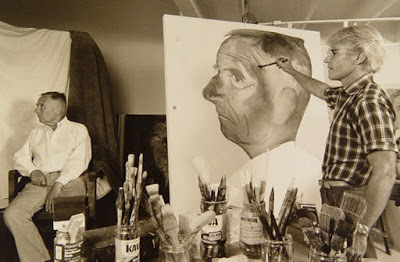

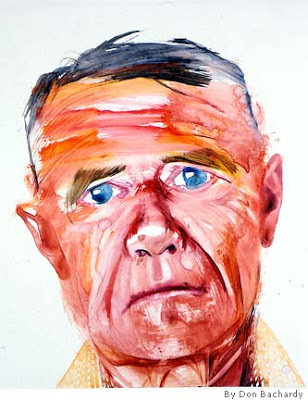

Don Bachardy painting Christopher Isherwood

Here are the various volumes of his diary, as edited by Auden scholar Katherine Bucknell. They're all enjoyable. The posthumously published memoir Lost Years, in which Isherwood tried to reconstruct a particularly interesting part of his life, shortly after his relocation to America, is in many ways the best. It's extremely frank about (in particular) his sex life - the other volumes were more or less censored since he seems to have meant them for eventual publication.

Isherwood, Christopher. Diaries. Volume One: 1939-1960. Ed. Katherine Bucknell. 1996. Vintage Books. London: Random House, 2011.

Isherwood, Christopher. Lost Years: A Memoir, 1945–1951. Ed. Katherine Bucknell. 2000. Vintage Books. London: Random House, 2001.

Isherwood, Christopher. The Sixties: Diaries Volume Two, 1960-1969. Ed. Katherine Bucknell. Foreword by Christopher Hitchens. 2010. Harper Perennial. New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 2011.

Isherwood, Christopher. Liberation: Diaries Volume Three, 1970-1983. Ed. Katherine Bucknell. Preface by Edmund White. 2012. Vintage Books. London: Random House, 2013.

Basically, Isherwood appears to have met everyone who was there to be met during this immense space of time, from the 1940's to the 1980's. He was banned from Charlie Chaplin's house after his host alleged that he'd pissed on his couch whilst in his cups (Isherwood maintained otherwise, but given he was drunk at the time, it's hard to see how he'd know).

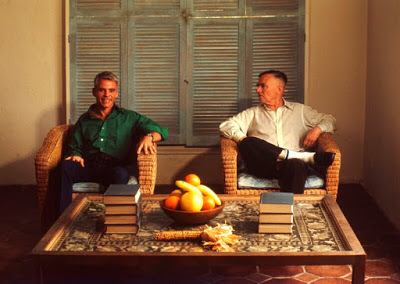

Who else? Stravinsky, Charles Laughton, Brecht, Thomas Mann, Aldous Huxley, David Hockney, to name just a few, as well as an endless line of eminent Hollywood actors and actresses, walked in and out of his life. The true theme of these diaries is marriage, though: his very complicated longterm relationship with the artist Don Bachardy. This began a little like one of the seduction scenes in A Single Man. Don was the gawky younger brother of one of Isherwood's casual conquests from the beach. He grew up into an immensely talented draftsman, portraitist and painter - each stage painstakingly documented here - as well as a valued collaborator on all of Isherwood's later work as scriptwriter for stage and screen.

Bachardy, in fact, turned out to be something of a phenomenon - so gifted in his own right that the initial push he got from being Isherwood's partner eventually became more of a liability. Their marriage was very volatile - with arguments, infidelities, breaks, non-exclusive arrangements at various points - but, finally, durable. It's not easy to warm to the earlier Herr Issyvoo of the Berlin stories, but Don Bachardy's older partner Dobbin is a far more likeable and protean creature.

One can see how Isherwood's obsession with documenting and recording his own life baffled many readers at the time, who saw it as an increasingly boring quest - especially after his apparent surrender to Lala Land after those fascinating chronicles of Germany and China in the turbulent thirties. Now, though, I think it can be seen as something hugely rewarding: an honest record of a way of life which will retain its interest not just as an historical vignette, but as a comfort to those whose own lives may seem (at times) as chaotic as his.

And, while he may have seen his greatest success in character portrayal as the "Christopher" of the Berlin novels and later memoirs, one would have to add that the Don Bachardy of the Diaries turns out, in the end, to be far more beguiling. How many completely believable portrayals of true love can you think of? Not many, that's for sure. The Isherwood-Bachardy partnership is certainly a strong contender for inclusion among them, though.

Don Bachardy: Isherwood (1937)

Christopher William Bradshaw Isherwood

(1904-1986)

Fiction:

Isherwood, Christopher. All the Conspirators. 1928. Foreword by the Author. 1957. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1977.

Isherwood, Christopher. The Memorial: Portrait of a Family. 1932. London: The Hogarth Press Ltd., 1952.

Isherwood, Christopher. Mr. Norris Changes Trains. 1935. Auckland: Penguin NZ, 1944.

Isherwood, Christopher. Goodbye to Berlin. 1939. Penguin Books 504. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1945.

Isherwood, Christopher. The Berlin of Sally Bowles: Mr. Norris Changes Trains / Goodbye to Berlin. 1935 & 1939. London: Book Club Associates / The Hogarth Press Ltd., 1975.

Isherwood, Christopher. Prater Violet. 1945. Penguin Modern Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969.

Isherwood, Christopher. The World in the Evening. 1954. Penguin Book 2399. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966.

Isherwood, Christopher. Down There on a Visit. 1959. A Bard Book. New York: Avo Books, 1978.

Isherwood, Christopher. A Single Man. 1964. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969.

Isherwood, Christopher. A Meeting by the River. 1967. Magnum Books. London: Methuen Paperbacks Ltd., 1982.

Autobiography:

Isherwood, Christopher. Lions and Shadows: An Education in the Twenties. 1938. Magnum Books. London: Methuen Paperbacks Ltd., 1979.

Isherwood, Christopher. Kathleen and Frank. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1971.

Isherwood, Christopher. Christopher and His Kind, 1929-1939. 1976. Magnum Books. London: Methuen Paperbacks Ltd., 1978.

Isherwood, Christopher. My Guru and His Disciple. London: Eyre Methuen Ltd., 1980.

Biography:

Isherwood, Christopher. Ramakrishna and His Disciples. 1965. A Touchstone Book. New York: Simon and Schuster, n.d.

Travel:

Isherwood, Christopher. The Condor and the Cows. Illustrated from photos by William Caskey. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1949.

Miscellaneous:

Isherwood, Christopher. Exhumations: Stories / Articles / Verses. 1966. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969.

Edited:

Isherwood, Christopher, ed. Vedanta for the Western World. 1948. Unwin Books. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1963.

Letters:

Bucknell, Katherine, ed. The Animals: Love Letters Between Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013.

Secondary:

Parker, Peter. Isherwood: A Life. 2004. Picador. London: Pan Macmillan Ltd., 2005.

W. H. Auden & Christopher Isherwood (BBC, 1938)

Chris O'Dell: Don Bachardy & Christopher Isherwood (1976)

Published on May 13, 2018 19:25

April 25, 2018

Yoknapatawpha Blues

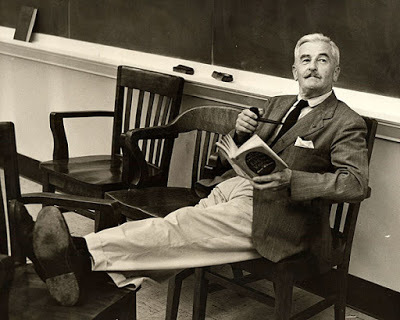

Faulkner in the University

I guess that's a bit of a test, actually. What do the words "Yoknapatawpha County" mean to you? If the answer is not a lot, I suspect you're not alone.

What they should mean, of course, is ground zero for William Faulkner's fictional universe of decaying Southern Colonels and pushy rednecks in the fever-drenched woods and swamps of Old Dixie.

I've just finished reading Joseph Blotner's immense, two-volume life of Faulkner, which seems at times to aspire to chronicle every day of his life in full detail.

Joseph Blotner: Faulkner: A Biography (1974)

Blotner does his best to soften Faulkner's reputation as a hopeless drunk and ne'er-do-well ("Count No 'Count," as some of the locals used to call him), and points out the immense industry and craftsmanship that enabled him to churn out 19 novels, 2 poetry collections, 5 collections of short stories, and 125-odd short stories in forty years of writing.

Nevertheless, Faulkner was definitely a bit of a wild card - prone to sitting for hours in complete silence, suspicious of strangers to an almost paranoid degree, and generally "not a tame lion" (as people keep on remarking of Aslan in C. S. Lewis's Narnia books).

Blotner, vol. I: flyleaf

photos: Bronwyn Lloyd

My own copy of Blotner, bought second-hand sometime in the 1980s, is clean and unannotated apart from a few interesting inscriptions on the fly-leaf. I thought I might share these with you in the hope of further elucidation of just what "P. L. Nairn [?: Nairne? Napier?]" may have meant by them.

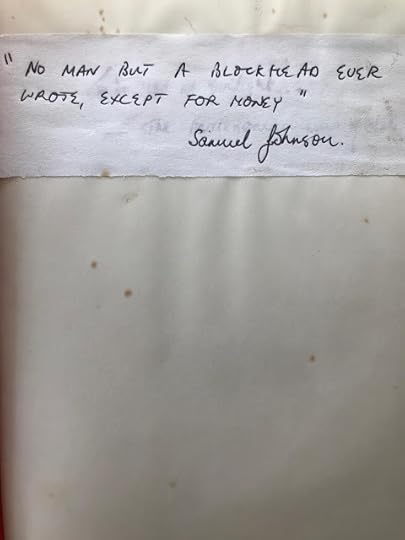

Blotner, vol. I: halftitle

"No man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money"That one seems pretty self-explanatory. One constant theme in Faulkner's letters and daily life is the endless need for money. Selling short stories, selling movie scripts, selling anything that moved in order to maintain his beleaguered Southern Mansion Rowan Oak is a constant theme. This tails off a bit after the award of the Nobel Prize (most of which he actually ended up putting in trust to help other writers: particularly African American ones - which goes some way to giving the lie to his alleged racism), but by then the royalties on his books had begun to grow more substantial, in any case.

- Samuel Johnson

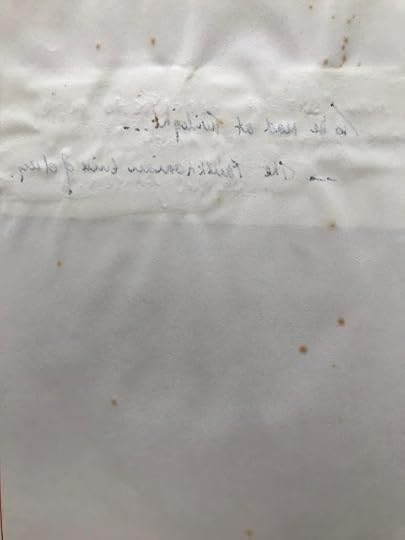

Blotner, vol. I: back of halftitle

What interests me most about this motto, however, is the fact that it's written on a separate piece of paper which has been pasted in over another inscription. One can just dimly make it out if the page is held up to the light:

To be read at Twilight ...

- The Faulknerian time of day.

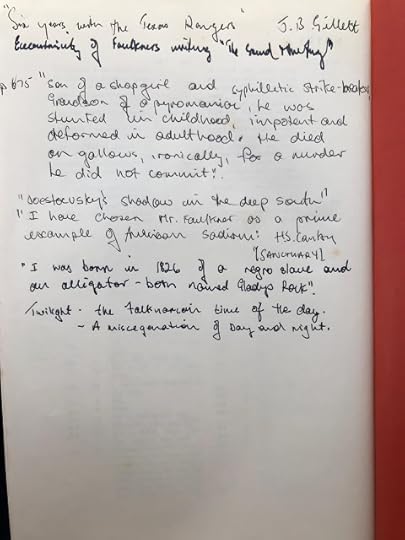

Blotner, vol. I: back flyleaf

It's not till he gets to the back of the book that he really lets himself go, however:

"Six Years with the Texas Rangers" J. B. GillettTowards the end of 1925, Faulkner's friend Phil Stone lent him a number of books (listed on p.489 of Blotner's biography): "As a change of diet from poetry, perhaps, he lent his friend James B. Gillett's Six Years with the Texas Rangers." Interesting? Not to me. It clearly was to P. L. Nairne, however.

Eccentricity [?] of Faulkner's writing "The Sound & The Fury"Roughly 35 pages (pp. 564-98) of Blotner's biography are devoted to the ins and outs of composing The Sound and the Fury, universally agreed to be Faulkner's most dizzyingly experimental piece of work, and regarded by most (myself included) as his masterpiece. Perhaps this is a reference to that strange ordeal.

p. 675: "son of a shopgirl and [a] syphilitic strike-breaker, grandson of a pyromaniac, he was stunted in childhood, impotent and deformed in adulthood. He died on [a] gallows, ironically, for a murder he did not commit."This is a quotation from Blotner's summing-up of the character Popeye in Faulkner's 1931 novel Sanctuary . While perfectly accurate in context, it does sound a little bizarre taken by itself.

"Dostoevsky's shadow in the deep south"This is the title of one of the reviews of Sanctuary, mentioned on p. 685 of Blotner, along with the following quote from Henry Seidel Canby's article about the book in the Saturday Review of Literature:

"I have chosen Mr. Faulkner as a prime example of American sadism: H. S. Cantor [SANCTUARY]And so we come to:

"I was born in 1826 of a negro slave and an alligator - both named Gladys Rock."This is a straight quote from an interview Faukner gave to a reporter called Marshall J. Smith in 1931 (Blotner, 694). He went on: "I have two brothers. One is Dr. Walter E. Traprock and the other is Eaglerock - an airplane." Walter E. Traprock, as it turns out, is the pseudonym under which George Shepard Chappell published a series of parody travel books: The Cruise of the Kawa: Wanderings in the South Seas (1921), My Northern Exposure: the Kawa at the Pole (1922), and Sarah of the Sahara: a Romance of Nomads Land (1923) among them. Faulkner was in fact the eldest of three brothers. The youngest, Dean Swift Falkner (the "u" came later), was killed in an airplane crash in 1935. His eldest brother Bill had bought him the plane and taught him to fly it. Connections! Connections everywhere, from what I can see.

Twilight: The Faulknerian time of the day.This appears to be another version of the obscured quotation at the front of the book, tidied up a little and with the addition of the "miscegenation of day and night" conceit. I'm not sure that it's a particularly happy one.

- A miscegenation of Day and night.

Interestingly enough, it's the Dostoevsky quote, above, which seems to lead in the most promising directions, witness the following passage on p.716 of Blotner's first volume:

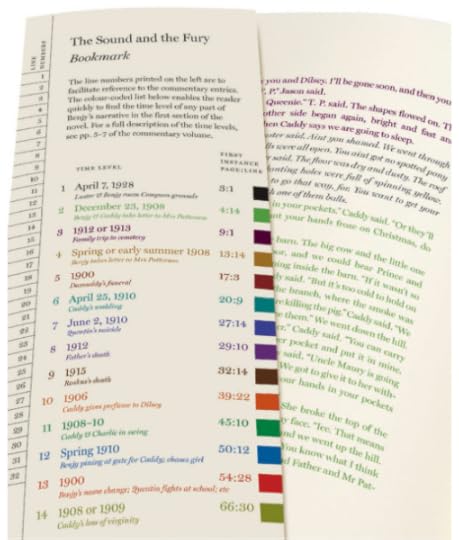

When the [student] reporter [from College Topics, at the University of Virginia, who knocked him up in his hotel room at midnight in late 1931] raised the question of technique, Faulkner talked about Dostoevsky. He could have cut The Brothers Karamazov by two thirds if he had let the brothers tell their stories without authorial exposition, he said. Eventually all straight exposition would be replaced by soliloquies in different coloured inks.It's a well-known fact that Faulkner believed that Benjy's monologue at the beginning of The Sound and the Fury - literally the tale referred in Macbeth's famous soliloquoy as: "told by an idiot" and "signifying nothing" - could be straightened out most easily by the judicious use of coloured inks.

He was eventually persuaded (reluctantly), that this was beyond the printing technology of the time, but he never stopped hankering after it. The proposal of a limited édition de luxe in 1931 brought the idea to life again, and he sent in a complex scheme of three coloured inks to the printers, who had to abandon the notion, unfortunately, due to the damage to the book trade caused by the Great Depression.

William Faulkner: The Sound and the Fury (Folio Society)

You can't keep a good idea down, though, and in 2012 the Folio Society in London actually published such a book: with a full commentary on the text and a complex battery of no fewer than fourteen different coloured inks!

William Faulkner: The Sound and the Fury (Folio Society)

There's a great deal more to be said about Faulkner, some of which I aspire to include on this blog at some point: his immense influence on such Latin American "Boom" novelists as Carlos Fuentes, Mario Vargas Llosa and Gabriel García Márquez, for instance.

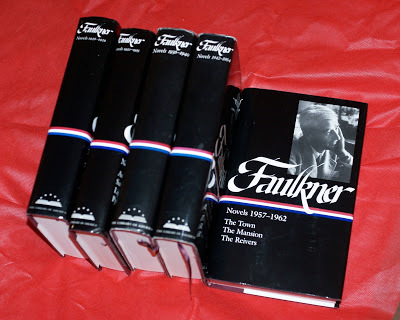

For the moment, though, I'll simply note here the recent completion of the Library of America's five-volume edition of Faulkner's complete novels, all in their revised and "corrected" texts:

William Faulkner: Complete Novels (Library of America)

Faulkner, William. Novels 1926-1929: Soldiers’ Pay / Mosquitoes / Flags in the Dust (Sartoris) / The Sound and the Fury. 1926, 1927, 1929 & 1929. Ed. Joseph Blotner & Noel Polk. The Library of America, 164. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 2006.

Faulkner, William. Novels 1930-1935: As I Lay Dying / Sanctuary / Light in August / Pylon. 1930, 1931, 1932 & 1935. Ed. Joseph Blotner & Noel Polk. The Library of America, 25. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 1985.

Faulkner, William. Novels 1936-1940: Absalom, Absalom! / The Unvanquished / If I Forget Thee, Jerusalem (The Wild Palms) / The Hamlet. 1936, 1938, 1939 & 1940. Ed. Joseph Blotner & Noel Polk. The Library of America, 48. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 1990.

Faulkner, William. Novels 1942-1954: Go Down, Moses / Intruder in the Dust / Requiem for a Nun / A Fable. 1942, 1948, 1951 & 1954. Ed. Joseph Blotner & Noel Polk. The Library of America, 73. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 1994.

Faulkner, William. Novels 1957-1962: The Town / The Mansion / The Reivers. 1957, 1959 & 1962. Ed. Joseph Blotner & Noel Polk. The Library of America, 112. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 1999.

If you add a copy of his Collected Stories (1951) - along with Joeph Blotner's supplementary volume of Uncollected Stories (1979) - you'll have pretty much the whole story laid out in front of you in one convenient canvas.

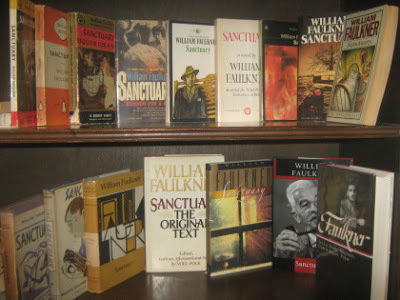

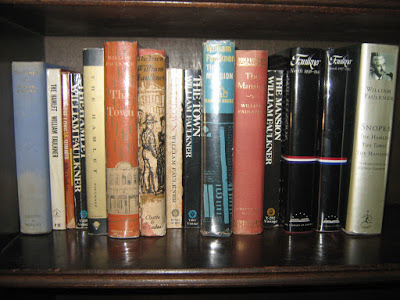

Here's a listing of my own Faulkner collection. Not complete, certainly, but with most of the books that any but the most abject collector would consider to be indispensable to a close knowledge of the subject. Enjoy!

•

William Faulkner: Sanctuary (1931)

William Cuthbert Falkner [Faulkner]

(1897-1962)

Poetry:

Faulkner, William. The Marble Faun and A Green Bough. 1924 & 1933. New York: Random House, Inc., n.d.

Fiction:

Faulkner, William. Soldiers' Pay. 1926. Penguin Modern Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin / London: Chatto and Windus, 1976.

Faulkner, William. Mosquitoes: A Novel. 1927. Introduction by Richard Hughes. London: Chatto & Windus Ltd., 1964.

Faulkner, William. Sartoris. 1929. Foreword by Robert Cantwell. 1953. Afterword by Lawrance Thompson. A Signet Classic. New York: The New American Library, Inc., 1964.

Faulkner, William. Flags in the Dust. 1929. Ed. Douglas Day. 1973. Vintage Books. New York: Random House, Inc., 1974.

Faulkner, William. The Sound and the Fury. 1929. Introduction by Richard Hughes. 1954. Penguin Modern Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin / London: Chatto and Windus, 1970.

Faulkner, William. The Sound and the Fury: An Authoritative Text / Backgrounds and Contexts / Criticism. 1929. Ed. David Minter. 1984. Second edition. A Norton Critical Edition. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1994.

Faulkner, William. The Sound and the Fury. 1929. Ed. Noel Polk & Stephen M. Ross. 2012. London: The Folio Society, 2016.

Faulkner, William. As I Lay Dying: The Corrected Text. 1930. Vintage International. New York: Random House, Inc., 1985.

Faulkner, William. Sanctuary. 1931. Penguin Books 899. Harmondsworth: Penguin / London: Chatto and Windus, 1953.

Faulkner, William. Sanctuary: The Original Text. 1931. Ed. Noel Polk. London: Chatto and Windus Ltd., 1981.

Faulkner, William. Light in August. 1932. London: Chatto and Windus Ltd., 1952.

Faulkner, William. Pylon. 1935. London: Chatto and Windus Ltd., 1955.

Faulkner, William. Absalom, Absalom! 1936. Modern Library College Editions. New York: Random House, Inc., 1964.

Faulkner, William. The Unvanquished. 1938. Penguin Books 1058. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1955.

Faulkner, William. The Wild Palms. 1939. Penguin Modern Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin / London: Chatto and Windus, 1970.

Faulkner, William. The Hamlet: A Novel. 1940. London: Chatto and Windus Ltd., 1958.

Faulkner, William. Go Down, Moses and Other Stories. 1942. Penguin Books 1434. Harmondsworth: Penguin / London: Chatto and Windus, 1967.

Faulkner, William. Intruder in the Dust. 1948. Penguin Modern Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin / London: Chatto and Windus, 1970.

Faulkner, William. Knight’s Gambit: Six Stories. London: Chatto and Windus Ltd., 1951.

Faulkner, William. The Penguin Collected Stories of William Faulkner. 1951. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985.

Faulkner, William. Collected Stories. 1951. Vintage. London: Random House, 1995.

Faulkner, William. Requiem for a Nun. 1951. Penguin Modern Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin / London: Chatto and Windus, 1973.

Faulkner, William. A Fable. 1954. London: Chatto and Windus Ltd., 1955.

Faulkner, William. Big Woods: The Hunting Stories. Drawings by Edward Shenton. New York: Random House, 1955.

Faulkner, William. The Town. 1957. A Vintage Book. New York: Random House, Inc. / Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., n.d.

Faulkner, William. The Mansion. 1959. World Books. London: The Reprint Society Ltd. / Chatto and Windus Ltd., 1962.

Faulkner, William. The Reivers: A Reminiscence. 1962. Penguin Books 899. Harmondsworth: Penguin / London: Chatto and Windus, 1970.

Blotner, Joseph. Uncollected Stories of William Faulkner. 1979. London: Chatto & Windus Ltd., 1980.

Miscellaneous:

Cowley, Malcolm, ed. The Essential Faulkner: The Saga of Yoknapatawpha County, 1820-1950. 1946. A Chatto & Windus Paperback CWP 14. London: Chatto & Windus Ltd., 1967.

Faulkner, William, ed. The Best of Faulkner. London: The Reprint Society Ltd. / Chatto & Windus Ltd., 1955.

Faulkner, William. New Orleans Sketches. Ed. Carvel Collins. 1958. London: Chatto & Windus Ltd., 1967.

Faulkner, William. Essays, Speeches and Public Letters. Ed. James B. Meriwether. 1965. London: Chatto & Windus Ltd., 1967.

Secondary Texts:

Blotner, Joseph, ed. Selected Letters of William Faulkner. New York: Random House, Inc., 1977.

Blotner, Joseph. Faulkner: A Biography. William Faulkner’s Life and Work: Over 100 Illustrations; Photographs, Drawings, Facsimiles; Notes and Index; Chronology and Genealogy. 2 vols. London: Chatto & Windus Ltd., 1974.

Cowley, Malcolm. The Faulkner-Cowley File: Letters and Memories, 1944-1962. 1966. New York: The Viking Press, Inc., 1967.

William Faulkner: Snopes (1940, 1957 & 1959)

Published on April 25, 2018 21:57

April 5, 2018

Why Stanislaw Lem?

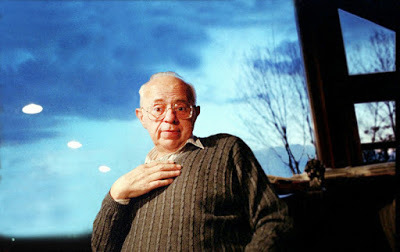

Wojciech Druszcz: Stanisław Lem

What is it about Stanislaw Lem that sets him apart from other SF writers? Because there is something that puts him in a category of his own, somewhere between J. G. Ballard and Philip K. Dick, though with powers of pure intellect quite different from their more sensitive, aesthetic approach to what Lem himself once called (in his essay "Philip K. Dick: A Visionary Among the Charlatans"):

the whole threadbare lot of telepaths, cosmic wars, parallel worlds, and time travel ...

Stanisław Lem: Solaris (1961)

Ever since I first chanced on a copy of Solaris in the local second-hand shop in Mairangi Bay, I've been trying to come to terms with his work. I wasn't even aware then that there was a film - let alone one as beguiling and magical as Tarkovsky's - so the book made its impact on me without any other visual aids.

The long account of the science of "Solaristics" in the middle chapters of Lem's story function as a satire on Academia in general: its tendency to lurch from one one-sided theory to another, but it also shows a faith in the basic seriousness of his readers which transcended any of the more conventional slam-bang American or British Sci-fi I'd grown up on.

Stanislaw Lem: The Invincible (1964)

The other book of his I read at this time was The Invincible. Wow, what a contrast! This grim story of a thwarted attempt at planetary colonisation would have been almost unimaginable in English-language SF at the time. No boosterism - no Campbell-era "man plus" thinking. Lem was a serious dude, and his books clearly repaid study rather than providing instant gratification.

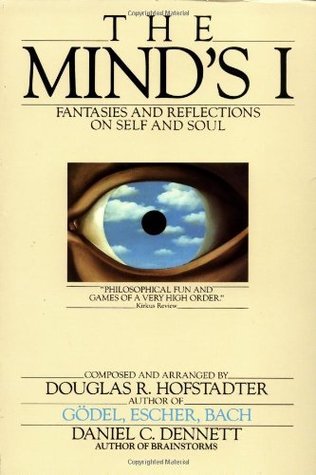

The Mind's Eye, ed. Douglas R. Hofstadter & Daniel C. Dennett (1981)

It's a little difficult now to account for the excitement surrounding Douglas R. Hofstadter's book Gödel, Escher, Bach in the late 1970s. Everyone I knew - in my own little circle of secondary school 'intellectuals,' that is - made some attempt to read it. I got about halfway through. Perhaps some of the others, cleverer at Maths, were actually able to get to the end. This anthology of pieces, co-edited by him and Daniel C. Dennett, appeared a couple of years later, and introduced me to a whole species of thinking about Artificial Intelligence and other cool subjects I knew virtually (pun intended) nothing about.

I'd already read Borges, but meeting him in this new company made me see that his work was the beginning rather than the end of a particular train of thought. And there were pieces in there by Stanislaw Lem, too: strange, non-naturalistic tales of computer derring-do which called all conventional genre-categories into question. I began to realise that the basically realistic settings of Solaris and The Invincible were only a small part of his work. I started to wonder, in fact, if they were simply intended as cynical strategies to lure the unwary into the seamless web of his "deeper" works.

And so my quest began: to explore the strange galaxies of Stanislaw Lem, to attempt to understand just why he was the "most widely read SF writer in the world" (as all his blurbs said). Was it simply because he had a virtual monopoly on the field in the entire Eastern bloc, or was there more to it than that? Did he offer something better than those "threadbare" themes, mentioned above?

Stanislaw Lem: Solaris / The Chain of Chance / A Perfect Vacuum (1961, 1975 & 1971)

As so often in those days, Penguin books came to the rescue. These two wonderful King Penguins from 1981 reprinted the two novels I'd already read alongside a series of strange mock-reviews of imaginary books (A Perfect Vacuum); a bizarrely circumstantial account of a particular 'coincidental' set of events (The Chain of Chance); a completely convincing - because almost completely incomprehensible - account of the future world encountered by a returning astronaut (Return from the Stars); as well as some strangely subversive tales of space-travel by the eponymous Pirx the Pilot.

Stanislaw Lem: Tales of Pirx the Pilot / Return from the Stars / The Invincible (1973, 1961 & 1964)