Jack Ross's Blog, page 18

October 18, 2019

Millennials (4): Song of the Brakeman (2006)

Bill Direen: Song of the Brakeman (2006)

Blurb:

Song of the Brakeman happens in a world where the earth's resources are almost exhausted, the water supplies are contaminated and parts of the landmasses have imploded. But the crisis into which this novel plunges the reader is not only an ecological one. An urban technician and his tribal lover are forced to take sides in a life-or-death struggle between irreconcilable forces: one in possession of the earth's remaining wealth and power, the other carrying the genetic key to the survival of mankind.

Bill Direen has written about a Balkans refugee in Berlin, a coma-victim at a rock concert, and the underbelly of art-obsessed Paris. In Song of the Brakeman a new cast of edgy characters is born to a world heading for extinction.

To justify the errors of their machine they sent me for a therapy called Writing. - Bill Direen, Song of the Brakeman (Auckland: Titus Books, 2006): 114.

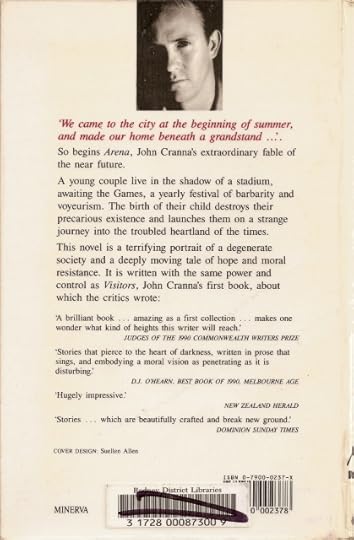

The blurb above certainly doesn't do justice to the profoundly disturbing nature of William (Bill) Direen's masterpiece, Song of the Brakeman.

Direen is probably more famous, still, as an alt rock musician than as a writer. “Bill Direen is Chris Knox for people who think of Chris Knox as Neil Finn” - as Scott Hamilton once mordantly summarised Direen’s status within New Zealand music. As a solo artist, and with his band The Bilders in all its various manifestations, he's compiled a large back-catalogue of deliberately 'lo-fi' recordings and performances.

His writing career came later, in the late 1990s and early 2000s. You can find an annotated list on his Wikipedia page, as well as in the (selected) bibliography below.

Rather than attempt to characterise his work - in its most extreme form, as manifested in such parts of his œuvre as Song of the Brakeman - it seems easier to quote some examples. Here's a touching anecdote from a conversation his protagonist, the Brakeman, has with a fellow customer in a brothel, early on in the novel:

'It's the month of the partial eclipse. I've lost everything and I'm walking along where my house used to be, looking for anything, a dog collar, a plank of wood painted cosy green. Among those fjords that used to be my suburb there it is, docked between two rocks, a trimaran on stilts. A light is shining from the observation window. I climbs a rock and sees a lean figure, scarlet, part-man, part-woman, piece shining like a diamond. She opens her blouse to another, a two-way him-her, who draws a fiber from her heart and eats it neat. He grows, slow and painful like there's a weight inside him. They mock each other on the slippery decking, spitting in the face, you know, and twining like it ain't, y'know, love, like eels on heat. You seen that?'If that doesn't mean a lot to you, fear not. The foreign inflections of the idioms of our future will fall gradually into focus, until finally you'll wonder why you ever had any trouble with them ... One of the central problems with this future, however, is its insistence on the evils of unrestricted writing. One of the Brakeman's earliest misdeeds is cooking up a batch of ink for his upstairs neighbour, an aristocratic young dancer:

The mercenary's rendition was corn porn, but his trade was his will and testament. He had seen a tribeswoman donating to save one of our boys who, like me, was less than tribal. Galveston had him as beefsteak before World Independence Day. [31]

When she asked me for ink I couldn't refuse, though I knew the danger. Anyone who used that stuff was regarded as an enemy of the state. I perfected the mix that would be the cause of her arrest, a crimson viscous concoction thickened with carbon from the incineration pits. You could do anything with it, old conning peasant dark drivel, government poetry, South Sea journals, delta discoveries, but that monkey bile would darken her manuscript best of all. [24]That list could serve quite nicely as a characterisation of the book itself. All of those things (and more) are to be found within these pages.

Matt Kelly: Cover Image (2007)

My brother Ken wrote a review of Bill's book in brief #35. In it he commented particularly on this central linguistic aspect of the novel:

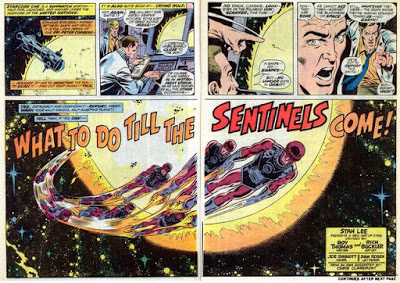

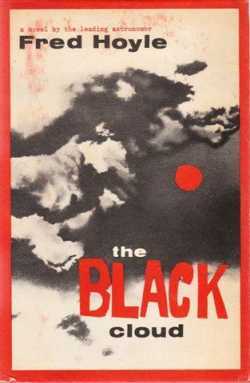

The driving, pulsating, often super-elaborate quality of the language was another fascination. Direen can create a new slang in every page. He can involve mystical reasonings, implied comments on the human condition, in what is largely a fast-moving narrative texture. For those who love language for its own sake, this makes for an invigorating ride. Both these additions and the poetical aspirations of the book take it, in fact, outside the bounds of Science Fiction proper. We could say that by a synthesis of directions, Direen has managed to occupy new literary ground. - K. M. Ross, 'Review of Song of the Brakeman.'With due respect to Ken, I'm not quite sure that I agree there. It's true that such violent dislocations of language do seem more designed to evoke Finnegans Wake than (say) The Day of the Triffids (a comparison already made by Scott Hamilton in his launch speech for the book). 'Science Fiction proper' has always been a bit of a difficult beast to taxonomise, however. As Kingsley Amis and Robert Conquest remark in the epigraph to their 1962 anthology Spectrum 2:

brief 35 - A brief world order, ed. Brett Cross (September 2007): 120-21.

'Sf's no good,' they bellow till we're deaf.I'd like, instead, to suggest a few possible analogues:

'But this looks good.' - 'Well then, it's not sf.- Kingsley Amis & Robert Conquest, ed. Spectrum II: A Second Science Fiction Anthology. 1962. Pan Science Fiction (London: Pan Books Ltd., 1965): 4.

Russell Hoban: Riddley Walker (1980)

The obvious one is with Russell Hoban's classic novel Riddley Walker (1980). Because it's written in a gnomic, riddling style, the fact that this is clearly a piece of SF in the standard understanding of the term - plot-wise, thematically, and in terms of intention - was repeatedly denied by critics who felt that it was too accomplished to deserve the appelation. The generic flexibility of Hoban's other work - from fantasy in The Lion of Boaz-Jachin and Jaachin-Boaz (1973) to the eco-fiction of Turtle Diary (1975) - gave fuel to their argument: somewhat absurdly, in retrospect.

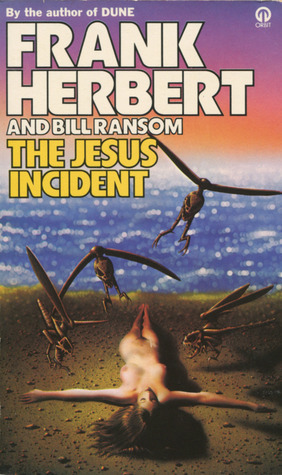

Frank Herbert & Bill Ransom: The Jesus Incident (1979)

I would challenge any reader to go through the first twenty or so pages of the work above and give me an accurate summary of their contents. It takes time for post-new wave SF novels to establish the ground rules both of the cosmos they inhabit and the language in use there. Sometimes it's easy, sometimes (as in this case) extremely challenging. It's something that die-hard fans learn to live with. Non-SF-tempered readers can find it a sore trial, however.

And yet no-one ever proposed the novel above as anything but strict SF, despite its thematic complexity and scope. The same is true of the more conventionally composed Dune (1965), despite its obvious status as one of the most influential novels of the past fifty years (as a pioneering piece of 'planetary ecology', among many other things).

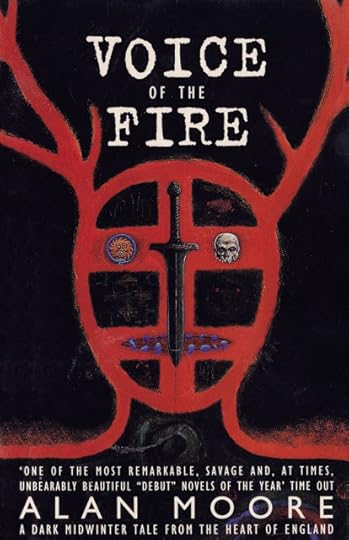

Alan Moore: Voice of the Fire (1996)

My final exhibit is comics-supremo Alan Moore's debut print - as opposed to graphic - novel, Voice of the Fire. The resemblances here with Riddley Walker are strong, despite the prehistoric setting of the first section of his story. This makes it what? Fantasy? Historical fiction? Fantasy-&-SF? In the end, all one can really call it is a singularly ambitious novel, tout court.

And so, without doubt, is Direen's Song of the Brakeman.

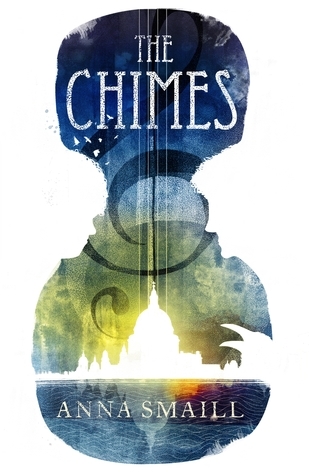

Speaking for myself, I found the first fifty or so pages of the book fairly impenetrable on my first run through - after that, however, things settled into a more or less comprehensible narrative. Turning back, however, the first pages seemed no more difficult than the last: it's as if it simply takes that long for Brakeman's language to come into focus - rather like that in use in the memory-less world of Anna Smaill's The Chimes.

Anna Smaill: The Chimes (2015)

Direen's book is in four sections:

The Yard (pp. 7-98): The Brakeman in his natural state, working to repair the vehicles that roar up and down the broken super-highways of this devastated future world. The start of his love affair with the queen of the rebellion, Enola, and his meeting with the mistress of theory, Myra.

It was twenty five years since the world, or what was left of it, had declared itself one state. The world turned twenty six. The new configuration of the earth's plates was holding. Magnetic lines were settling in to the new order. We were belting through time as before, 365 days a ringband, 67,000 miles an hour, the sun beating through the milky way once every 225 million years. It was eternity as usual ...Pell (pp. 99-179): The Brakeman in prison, tortured within an inch of his life, but finally contriving to escape in a Blackhawk helicopter with Enola, who's been masquerading as a nurse within the facility.

I was afraid to sleep, and afraid not to. I sat up nights watching, waiting. The weather was playing tricks. Cloud was condensing in the yard, dribbling down the walls. It was gray all day, every day. [81]

It had been a long dry, as great a calamity as when the ice caps had melted and the dried-up viscera of the earth had caved in, fragmenting the continents. True water had sunk beneath the petroleum gunge, the dregs of centuries. Underground caves had sucked it way down till it was too deep to bore. Some of the water had returned as steam from volcanic port-holes but it had changed. Its chemical composition was no longer H2O ... A weight, heavy as earth itself, rose above us. [127]

Cyberpunk 2077

The Flood (pp. 181-205): Their subsequent adventures in the viscous soup that passes for the remnants of the world's oceans, in an increasingly dreamlike state, as their son Richie is born and grows into maturity in the space of a few days.

As we penetrated Flood we found that there were areas which did not congeal in the night, and crusted floating masses which did not dissolve during the morning. These merged on contact to form floating islands. Their terrain appeared smooth but was jagged with dangerous crystal blooms. Not all floating objects were dangerous. Some were boons. One floating crate was full of sealed packets of seaweed powder, rich in vitamins. [192]The Tribe (pp. 207-64): The revelations at the heart of the forest, the final battle between Cadena's forces of destruction and the survivors of the tribe: the birth of a new consciousness beyond the alternating forces of life and death.

The chiefs lacked the usual combination of elements, of right and left, male and female. They were formed in a way I had never contemplated. Few of the males had scrotums to speak of and few of their penises had stems - they were knobs of Tyrian purple nosing out of thinning fur. The breasts of those who had them, whom I will call the women, were large. In fact, they were being milked and their primary protein source must have contained some antidote, an ingredient that kept many of the limitless poisons and microbes at bay. The ganglia of many were, nevertheless, tumefied. The necks of some were lymphatic pile-ups, Many had stitch marks where apprentice surgeons had implanted digestive organs. Some displayed evidence of freelance experiments: patches of animal fur, non-human mammalian genitals ineptly implanted. This gave me hope. Where there were surgeons there was some form of anesthesia and stitching thread to retrieve Myra's theory. [225-26]

Jean Wimmerling: Cli-fi (2018)

This last section of Direen's book, in particular, defies easy summary. His prose grows increasingly surrealist and disjointed, till it begins to resemble a strange cross between Angela Carter (the first chapter, in particular, of The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffmann - published in the US as The War of Dreams) and the Comte de Lautréamont's visionary Chants de Maldoror.

Mind you, something like this might be expected of a narrator who learned his art in prison, under the watchful eye of his torturers (as well as Enola, his tribal lover disguised as a nurse):

She had a stack of biros and I was soon working with my left hand. Soon we would have a script, a real pot-boiler. Old trash with the hot stink, survival stories, commando raids, jealous killers, androgynous embryo-farming hitchhiking cannibals, city-born unknowing incest pairs, isosceles political love triangles, rebellious impotent pinned entomologists hot for virgins and farmer-savages, heretic self-made execution-rippers caging leper monks and concupiscent boat-boys.More to the point, however, when Brakeman finally reaches the centre of his personal labyrinth, the regions of the tribe, he is separated from Enola and acclimatised to the new conditions by his new he/she lover Xanjal:

Imagining is free, even in three-word strings. [149]

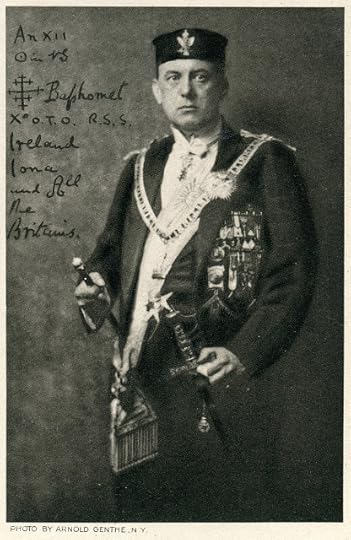

On the fifteenth day we rose from the bed and she guided me through the city. There were two cities, she said, contained in the same space, but she could only show me one. There was no law against looking through the cracks in the temple walls. There were centuries-old icons there, pheasants being roasted over fires of seasoned cherry wood, a priest sprinkling oregano over the flames. In another chapel I saw women being crucified for having failed impossible tasks. I fell back. She laughed at that. She said no one sees other than what is in his or her own mind. She was so like a ghost when we went through the city together, that I asked her if she had ever been in touch with the dead. She said that death returns us to the future. We arrive every moment from the future. When we die we go there eternally. [230-31]"No one sees other than what is in his or her own mind" - is that the final message of Direen's book (insofar as any book needs a 'final message')? Certainly Aleister Crowley's motto (borrowed from Rabelais): 'Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law,' appears to be the only rule that applies in this strange multi-layered city / swamp / forest.

Aleister Crowley (1875-1947)

Another, even stranger influence on his work might be seen elsewhere, in the weird fantasy adventures of Victorian visionary Rider Haggard. Direen's endlessly dying and reviving heroine Enola (named, presumably, for the bomb that spawned all these misadventures and transcendences) reminds one of no-one so much as Haggard's immortal heroine She-who-must-be-obeyed:

Rider Haggard: She (1887)

And not simply in her first incarnation as the white queen of a cannibal tribe in Africa, but her later, even weirder appearance in the mountains of Tibet, as the reborn Ayesha.

Rider Haggard: Ayesha: The Return of She (1905)

We could continue this allusion-hunting indefinitely, however. I have to admit that I still have many questions about Direen's book, though. Why, for instance, is there a state of John Logie Baird, the Scottish inventor of television, outside the spurious 'voting booth' on p.25? Does he have a place in this future polity akin to that of Henry Ford in Aldous Huxley's Brave New World?

Is the trimaran found by Brakeman and Enola in the swamps of Flood, on p.188, the same as the one described in my first extended quote above, the one where a tribeswoman is seen donating her heart's blood to save 'one of our boys'?

What is the significance of the name 'Richie Tibbetts'? Why is Enola and Ex-P's child called that? The account of his birth and upbringing and the strange sledding expedition to save his mother from a trapper (pp.194-96) is pretty trippy even by the standards of the rest of the book. Is this where the dreamtime really begins?

Bill Direen: Onævia (2004)

One obvious source of answers to this and other tantalising mysteries in the book might seem to be this earlier work by Direen, described by him on the SOUTH INDIES TEXT & MUSIC PUBLISHING site as the "invented history of an imaginary land, taking as its lead such masterpieces as Swift's Gulliver's Travels and More's Utopia. It is the first story of an SF sequence that includes Song of the Brakeman, L, and the two parts of Enclosures 'Jonah', and 'The Stadium'."

There is a somewhat more circumstantial blurb on Goodreads:

The nation of Onævia grows and declines on the edge of a vast continent. Games, cuisine, beliefs and unusual practices offer a glimpse of a polymorphic people, from the coronation of the first king to the capture of the last surviving Onævian.In practice, though, even if it is meant to serve as a 'prequel' to Song of the Brakeman, there's little in the strange fabular history of Onævia and its gradual descent into decadence and madness that serves to elucidate the latter work in any obvious way. In fact, the doings of the Boowigs and other descendants of the hunter Ighmut sound more like an exercise in Voltairean satire than the nightmarish, Ballardian headtrip of Brakeman.

There is, however, an intriguing paragraph on the god 'Flood' in the section on mythology in the appendix to Direen's book:

Flood was the fourth child of the second generation. Redundant, you might think, in the sea. But he liked nothing better than to glut himself on the shoreline and coastal plains. He reached his slime-coated needle-toes up, and scooped mouthfuls of soil down into his sieve-like gullet. He rose into the sky making beautiful clouds, before rushing down to have his pleasure of the earth, spreading amorphous over the valleys and plains, gathering huts, animals, soil and inhabitants, before spilling, with his plunder, into the discoloured ocean. - Bill Direen, Onævia: Fable. 2002 (Auckland: Titus Books, 2004): 110.Certainly one can recognise there some of the imagery of (in particular) part three of the later novel. Even if - as is quite probable - there are other anticipations there I've missed, Song of the Brakeman is surely the Huckleberry Finn to Onævia's Tom Sawyer: a sequel so much richer than its original that it must really stand alone.

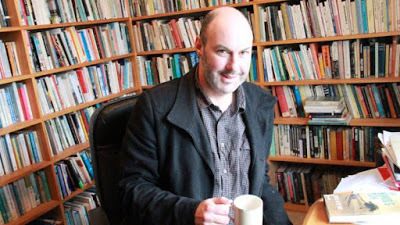

Rose Rees-Owen: Scott Hamilton (2015)

In his launch speech for the book, From First to Fourth Gear, poet and critic Scott Hamilton pointed out the rich heritage Direen's book is drawing on:

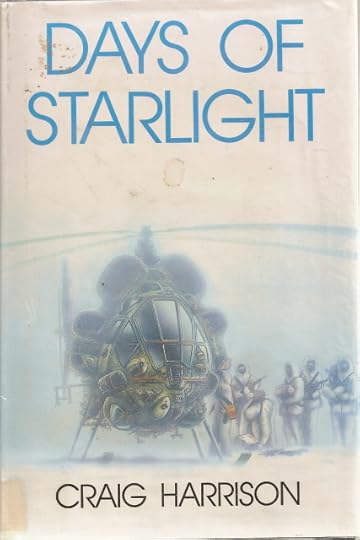

The story of Bill's Brakeman also calls up some interesting parallels in the canon of Kiwi literature. One thinks of Lear, a post-apocalypse novel by Mike Johnson ... and The Quiet Earth, the Craig Harrison novel which Geoff Murphy filmed in the '80s. The Quiet Earth showed us the conflict between a Pakeha scientist partially responsible for an experiment that has depopulated the earth, and a Maori who rejects him and his science, and ends up stealing the last girl on earth from him. There is a similar tension in Bill's novel between the Brakeman, a scientist implicated obscurely in the ecological catastrophe that has befallen the earth, and his lover, who belongs to a group of people who live a pre-industrial life. In Song of the Brakeman, as in The Quiet Earth, there is the question whether science and technology are hopelessly implicated in a way of life which has led to apocalypse, or whether they can be made to serve different ends. Can the scientist redeem himself, or must he suffer the same fate as the order he once served?

Critic Te Arohi (2019)

In a subsequent interview with Megan Anderson, printed in Otago University's student magazine Critic Te Arohi 7 (2007): 46-7), Direen himself offered some insights into the musical (and political) inspirations for his book:

Song of the Brakeman is set in a world like ours, but it is impossible to treat it as such. The landscape Direen portrays is one in which the continents have fragmented, the environment is irrevocably tainted, the ice caps have melted, and the entire hydrological cycle is suspended. Direen calls it “a world of the imagination, rather than of the future.” This is reassuring, as the world Direen paints is the sort of apocalyptic future one could easily envisage for our own world, if global warming is anything to go by ...That seems as good a place as any to end - or, should I say, in the words of the X-Files, to suspend investigations.

During an interview with the Dunedin-based Bill Direen, Critic got the impression that storyline plays a relatively small role in Direen’s writing ... What’s particularly striking about the novel is its musicality. Direen uses narrative as an expressive tool, constantly altering the narrative’s pace, rhythm and tone to represent what it’s describing. What begins as a choppy, violent urban setting reflected through a film noir / Sin City monologue evolves into a retreat into nature — or what is left of it in a deteriorating world — a lyrical prose flooded with imagery. This performative aspect of Direen’s work is something he is obviously passionate about ... and this is evident in his search for a language which “includes the verbal elements and the musical elements which [are] a part of me, which [have] always been a part of me.” Direen emphasises the sound and musicality of language, rather than focusing on just the semantic qualities of words: “Because I was a musician, and still am” he says, “music and rhythm, and a lot of the musical aspects of language play a big part in the way that I see literature” ...

Direen is adamant that his search for an expressive, musical language is not him “purposely trying to be difficult in this language thing” though he admits, “People have accused me of it” ... The actual song of the Brakeman, sung enthusiastically by Brakeman in the midst of the exceedingly violent interrogation scenes of Part II, is, as Direen says “intended as light relief, really, because of all this heavy stuff.” Direen admits that “It’s a satirical piece, I guess. It’s sort of anti-capitalist.” This makes sense when considering how Direen’s interrogation scenes were influenced by the Guantanamo Bay imprisonments. While Direen refers to America extensively in the novel, he stressed that ‘it’s not anti-American, but obviously I use America as a model for the world state.” ...

At the end of the interview Direen asked Critic of his book, “Did you think it was bizarre?”

Song of the Brakeman bizarre? Perhaps. An absorbing novel regardless? Certainly.

The X-Files (1993-2018)

•

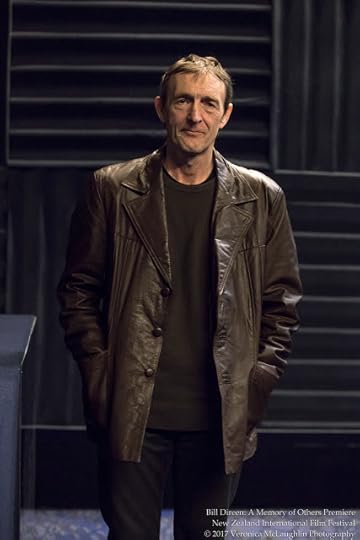

Bill Direen

William (Bill) Direen

(b.1957)

Select Bibliography:

Wormwood: Novel (1997)

The Impossible: Short Stories (2002)

Nusquama: Novel (2002)

Onævia: Fable. 2002. Auckland: Titus Books, 2004.

Jules (2003)

New Sea Land: Poems. Auckland: Titus Books, 2005.

Song of the Brakeman. Auckland: Titus Books, 2006.

Enclosures. Auckland: Titus Books, 2008.

The Ballad of Rue Belliard. Auckland: Titus Books, 2013. [In Brett Cross, ed. brief 48 (June 2013).]

Enclosures 2: Europe, New Zealand; Centre; Stoat: Canal City; Survey. Dunedin: Percutio, 2016.

Enclosures 3: Treatmen(o)t; Scipio Sonn; Nyons-Nice-Venice; Tattoo; from Stoat. Dunedin: in situ, 2017.

Enclosures 4. 2018.

Homepages & Online Information:

Wikipedia entry

William Direen: Jules (2003)

•

Published on October 18, 2019 12:27

October 11, 2019

Millennials (3): Skylark Lounge (2000)

Nigel Cox: Skylark Lounge (2000)

Publisher's Blurb:

In the middle of his life, Jack Grout found himself abducted by aliens. There were other things. His wife left him. His son came one night to the Skylark Lounge - the pool hall Jack bought after throwing in his job in newspaper advertising - and punched him. And there was the mistreatment for melanoma. But what Jack really needed to know was why the aliens, who had first taken him when he was nine years old and shown him his life in unbearably vivid close-up, had returned.

•

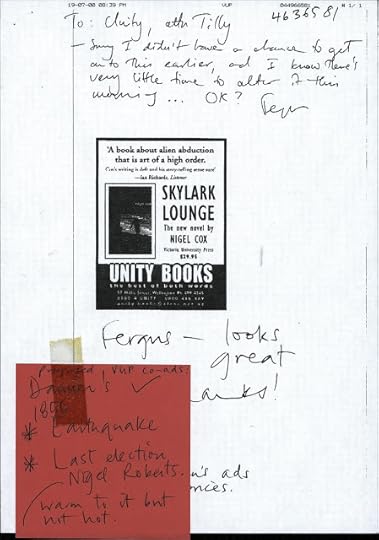

Nigel CoxOkay, I wrote this one – the novel I mean, as well as this review. And I bet that within ten years no-one will ever look at this review, so let’s just say it’s the greatest novel since War And Peace. Well, nearly. Actually, it was very well reviewed – one “the biggest book of the year” – honest! – and one “one of the year’s very best” and “from this unusual material Cox has mined a little gold,” plus, “Once Cox would have been called visionary” and other cheering stuff. Dodgy sales, but you get that – it WAS a serious novel that included an encounter with aliens. I was happy. What I liked was that the reviewers liked what I liked about it, which is that its narrator, Jack, is an ordinary man. In my opinion this is the hardest thing to write, an ordinary person who has a job and a family and is not over-intelligent but no fool either – and who isn’t depressed or depressing or boring, but can give you (this is my idea, but several of the reviewers picked up on it) a sense of the wonder of being in the world. Okay, that’s all I think I want to say: it’s a weird thing to do, this, kind of like an advertisement for yourself. But no-one will ever read it, except you maybe.

1.0 out of 5 stars

Who on earth will ever read this?

February 15, 2004

Format: Paperback

Nigel Cox, Berlin.

Yes, this is indeed Nigel Cox's own Amazon.com review of his 2000 novel Skylark Lounge. He'd published two earlier novels, Waiting for Einstein (1984) and Dirty Work (1987), over a decade before, and this was his big come-back title.

He'd spent much of the time between Dirty Work and Skylark Lounge working as a senior writer at Te Papa - a theme which leaks into Skylark Lounge. The hero's wife Shelley has basically the same job.

Shortly after the publication of Skylark Lounge Cox left New Zealand for Germany, where he took up a job as Head of Communication and Interpretation at the Jewish Museum, Berlin.

Looking at the recorded time (February 15, 2004) and place (Berlin) of the comment above, it must have been composed a year or so before his return to New Zealand in March 2005.

Nigel Cox died of cancer on 28 July 2006. His Wikipedia entry says that it's something he'd 'been battling for some time' - so perhaps that was one of the motivations for writing such an online cri-de-coeur.

Clearly he didn't think that the book - or his whole body of work, for that matter - had been given its due. So far as I can see, there are no such messages on Amazon.com about any of his other titles. Perhaps it was the neglect of this one in particular that really galled him.

What is Area 51?

Skylark Lounge is a novel about aliens. The main character, Jack Grout, had some encounters as a child, but when the aliens rediscover him again in the middle of a road just outside Wellington, his carefully constructed life begins gradually to unravel.

Recently, after a cancer scare, Jack quit his job and bought a pool hall, the eponymous 'Skylark Lounge,' which he runs as a haven of peace and quiet for the beleaguered wage slaves of the city.

All of this is threatened by the return of the aliens. They don't manifest in flying saucers; neither do they look like 'Greys' or any of the other familiar images from contemporary Abduction mythology. In fact, as we learn at the end of the novel, they are so microscopically small as to be virtually undetectable by human senses.

Their dilemma is that they tend to become anything that they pay undue attention to, so Earth, and humans, are maintained by them largely as a museum of Otherness. There's a small cadre of people they call on from time to time - a few thousands from among the millions - and Jack, it would appear, is one of these.

As Cox says above:

What I liked ... is that its narrator, Jack, is an ordinary man. In my opinion this is the hardest thing to write, an ordinary person who has a job and a family and is not over-intelligent but no fool either – and who isn’t depressed or depressing or boring, but can give you (this is my idea, but several of the reviewers picked up on it) a sense of the wonder of being in the world.It's tempting to regard the 'alien' plot as entirely metaphoric: simply a device for pointing out the wonder of 'ordinariness' by depicting its opposite. However, the careful attention Cox has paid to the mechanics of Jack's visions makes them sound more like Thomas Traherne's ecstatic prose-poetry than a kitchen-sink drama:

Tom Denny: Traherne Window (2007)

The corn was orient and immortal wheat, which never should be reaped, nor was ever sown. I thought it had stood from everlasting to everlasting.That's the quote - from Trahern's Centuries of Meditation (c.1674) - which everyone's so familiar with. Compare it to Cox's:

My hand touched a table. There was no boundary between the table and me. What a slow life the wood had. In that life all the past was present - the factory where the table had been built, the log from which it had been cut, the earth where it had grown.And then there's this from Traherne:

So nothing is lost. [142]

The Men! O what venerable and reverend creatures did the aged seem! Immortal Cherubims! And young men glittering and sparkling Angels, and maids strange seraphic pieces of life and beauty! Boys and girls tumbling in the street, and playing, were moving jewels. I knew not that they were born or should die; But all things abided eternally as they were in their proper places.Compare it to Cox's:

We'd come often to Pukerua when I was a kid. Great hook of bay. Immense eyeball of ocean, with seabirds flying long lines across it. Blue-green island long on the horizon, looking like Te Rauparaha's mere that I saw in Te Papa. In the foreground, the rock pools where we poddled, shrimping with milk bottles, prising limpets. [19]or this (from the account of Jack Grout's first 'abduction' experience):

And the world itself was wonderful too - the astonishing diversity of it, and all of it so busy and alive. Even the dead bits like the rocks - they seemed to be sort of humming. As I went higher I could see the coast curving away to the north, and then the outline of the southern end of the island, and finally I could see the whole North Island ... I can't tell you how much I loved the North Island. The shape of it. [24]

•

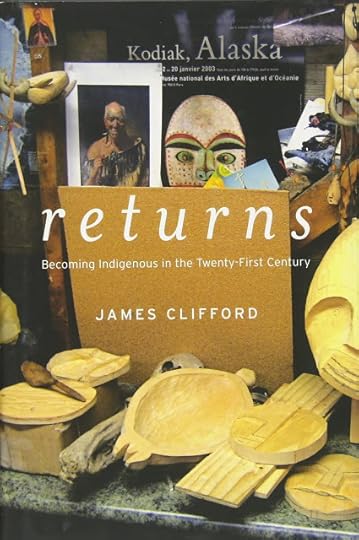

James Clifford: Returns (2013)

Recently a friend sent me a copy of this book about the concept of 'indigeneity' in the 21st century. I found it fascinating on many levels, but was particularly struck by the quotation below, towards the end of the final essay:

A more common "long-view" of history you hear when talking to Natives in rural Alaska is that the coming of the whites and all their technology was something long foretold by shamans and so on. Televisions and airplanes in particular were long foretold. This summer in [the Yup'ik town] Quinhagak I heard a new twist on this in that the little people (who appear now and again to people throughout the circumpolar world) used to appear to their ancestors wearing 20th century clothing and even sitting on tiny versions of 4-wheelers when confronting their 19th century ancestors, because little people have the ability to travel back and forth through time. But if prophesies exist, they don't seem to address what the end-game will be, or if this slow-motion train wreck of contact will continue forever. Or maybe people are just too polite to bring that up.I love that idea of the little people manifesting on four-wheelers, with contemporary clothes, to the distant ancestors - because time means something quite different to them than it does to us.

- Archaeologist Richard ('Rick') Knecht, quoted in Returns: Becoming Indigenous in the Twenty-First Century, by James Clifford (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2013): 318.

There's something of that paradoxical, dislocating nature in Cox's book, also:

I don't believe in synchronicity - as far as I'm concerned, a coincidence is a coincidence. It's important that I get this clear: I don't believe in fairies at the bottom of the garden. Because what I am going to get down in these pages will cast that into doubt. [11]The mention of 'synchronicity' gives us a cue, however. Synchronicity, as you're no doubt aware, is a concept of Carl Jung's, designed to 'account for' the seemingly meaningful webs of coincidences that surround us all.

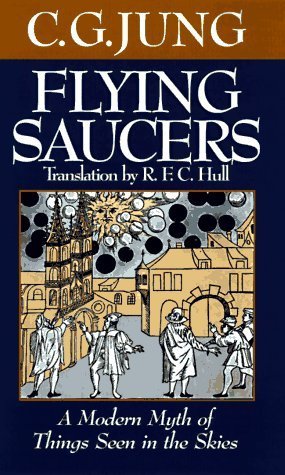

There's something of self-indulgent double-talk about it, as well as something of wisdom (like so much of Jung's thought), but the point is that it leads us naturally to his classic work on Flying Saucers. This long, late essays really put paid to any remaining scientific credibility he may have had - a bit like Freud's final thoughts on Moses and Monotheism - but it remains a small masterpiece of inductive logic.

C. G. Jung: Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Sky (1959)

Jung, Carl Gustav. Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Sky. Trans. R. F. C. Hull. 1959. London & Henley: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1977.

... the problem of the Ufos is, as you rightly say, a very fascinating one, but it is as puzzling as it is fascinating; since, in spite of all observations I know of, there is no certainty about their very nature. On the other side, there is an overwhelming material pointing to their legendary or mythological aspect. As a matter of fact the psychological aspect is so impressive, that one almost must regret that the Ufos seem to be real after all. I have followed up the literature as much as possible and it looks to me as if something were seen and even confirmed by radar, but nobody knows exactly what is seen. In consideration of the psychological aspect of the phenomenon I have written a booklet about it, which is soon to appear. It is also in the process of being translated into English.- C. G. Jung, Letter to Gilbert A. Harrison, editor of The New Republic (December 12th, 1957)Jung's point about the flying saucers is that it doesn't really matter - from the psychological standpoint, at any rate - whether they're 'really there' or not. What interests him is the way in which they infiltrated the imaginations of modern people, immediately after the Second World War, most of whom had denied themselves the release of conventional religious systems (and therefore conventional iconography).

Where an earlier generation would have seen angels and demons, these 'Moderns' saw visions which matched their materialist, scientific world-view: spaceships, and aliens from other planets, and such-like 'possible' manifestations to symbolise their underlying fears and anxieties.

Jung's essay concentrates on dream interpretation, and makes an excellent job of persuading readers that this imagery is only to be expected, given contemporary belief systems and material conditions - not to mention the overwhelming terrors of the (then) brand-new atomic bomb. Never had there been more cogent reasons for fear in the whole previous history of the human race. And this is how it declared itself.

Fiction writers, too, must deal with a world where the truth of what they say is always at a remove. The close attention paid to details of landscape and setting in Skylark Lounge - its intersection (presumably) with details from the author's own life - doesn't alter the fact that everything it is saying is to be taken metaphorically.

Are the 'aliens' meant to be real, in context? It doesn't matter. One could easily read the book either way. Even if Nigel Cox were a zealot for UFOlogy, and had written his novel as a contribution to the cause, it would still be the effect of these beliefs on his character - the things that could be said in this manner - which would actually matter to him.

Shelley is the only writer I've ever heard of who doesn't feel she should be writing a novel. She doesn't leave poems, or bits of poems, around the place on scraps of paper or in the margins of books. She's not an artist. She writes good clear prose, she says, and semi-snappy headlines, and she always hits her deadlines. She doesn't stay up late agonising. [51]Cox's main character certainly doesn't see himself as an artist. The proposed genealogy for the book we are reading is that it was all scribbled in exercise books in a motel in Waiouru shortly before his fateful last encounter with the aliens.

He is, of course, in practice, a hell of a writer - because Cox himself was - but then the same would have to be said of Mark Twain's mouthpiece Huckleberry Finn. Could an illiterate boy really write as resonantly and clearly as that? Of course not. But the tone must sound plausibly his for the writing to succeed at all. The same consideration applies to Jack Grout.

And, since Jack survives this final encounter (sorry for the plot-spoiler), we can imagine a final tidying-up of the manuscript - if not a careful reworking over time of the rough first draft - by him, or even by Shelley (if she ever works her way round to forgiving him).

•

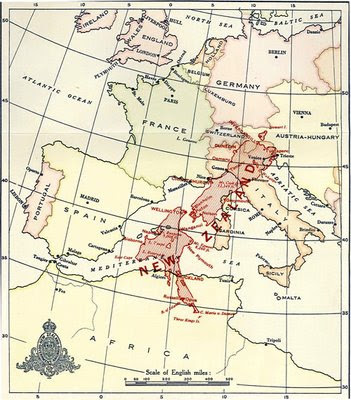

NZ Official Yearbook (1919)

For many years I co-taught a postgraduate course with the catchy title Contemporary New Zealand Writers in an International Context - a bit of a mouthful, certainly.

I suppose the reason for the clunky title was that we didn't want students to be surprised by what they encountered there. There certainly used to be a certain apartheid about literature courses here. 'Local' writers go in through that door - the old shabby one, just past the manuka hedge and the septic tank - and 'international' writers are ushered in through the space-age one covered with zinc, with a big red carpet leading up to it.

The average New Zealand literature class would begin with something along the lines of: "I was talking to Karl Stead the other day, and he said that Ronald Hugh Morriesson once told him that ..." Oodles of name-dropping and regional colour and only the occasional lapse into actual lit crit. I say it who know. I'm as guilty of all that as the next man ('Kendrick once said to me ...' 'I was having tea with Paula Green and she mentioned that ...')

The idea of this one was to compare prominent works by local authors with analogous 'international' texts, and to point out - all appearances to the contrary - that we don't live on an island intellectually and creatively, however far away we may be geographically from everyone else.

One of the texts we taught was Nigel Cox's Dirty Work (1987), and on one occasion his widow came to talk to the class - and us - about his work. I was the poetry person in the course, while my colleague Mary Paul handled the fiction, but I guess if I'd been trying to find a good analogue to Skylark Lounge (which would have been my first choice, much though I do admire Dirty Work), I might have come up with something like this:

Mark Z. Danielewski: House of Leaves (2000)

Those of you who've read it - or even heard of it - will know that Danielewski's debut novel is designed to screw with your head. The typography is odd, the story baffling, the implications quite terrifying - it's one of those stories, like Ring or Videodrome, where even encountering the outer levels of the mystery is enough to doom you to a fearful end. I suppose that's why it was so surprising that it became a runaway bestseller.

The same could not be said for any of Danielewski's subsequent works, which I have to say I found it impossible to make heads or tails of. This one, though, is a classical ghost story, despite all its frills and trimmings. In the same sense, Skylark Lounge is a classical UFO tale. Cox's economy of means is far more profoundly considered, however, which might even lead some readers to see it as throwaway.

Elizabeth Knox.com

Not so Elizabeth Knox. Recently she posted quite a long essay about the novel on her website, in which she made it clear that it was one of her favourites among his works. I won't quote too much of it (you can read it for yourself), but there are a few points she raises which I feel should be mentioned here:

Skylark Lounge is a book by someone who didn’t want to write a “kind” of book; a book with a defensible territory. It is not coincidental that its protagonist’s name is Jack Grout. Grout isn’t what sticks tiles to a wall, it’s what joins the tiles, and seals those joins. Skylark Lounge doesn’t have a single setting ... or a milieu. It has irises that open on its many scenes, a pool hall, a marriage bed, a back porch, a kitchen table in the Grout house, a tennis court, the surface of the moon, a Waiouru Motel.That's very nicely put, I think - and ties in very well with that comment of Cox's I quoted above (and which I first came across as a link on the thread inspired by Knox's article). The fact that it clearly came as news to her, as well as to me, makes the coincidence an even more striking one:

Skylark Lounge is a novel about a middle-aged man having a crisis because the alien abductors of the most ecstatic period of his childhood return, bringing their alienating ecstasies. ... The reader squirms with Jack as he tries to avoid telling his family why he’s off – off by himself, off at odd hours, off in his behaviour. And it cleverly incorporates into the story why Jack’s family at first offers him such latitude with his crisis. He’s recently had a brush with cancer, fruitless scans, and a course of chemo. By putting the cancer alongside the aliens as what might be going on with Jack, Nigel avoids the possibility that the metaphorical scope of his book will be reduced to the aliens representing cancer. I have heard Skylark Lounge discussed that way, and I remember that the first time I read it, with Nigel’s melanoma’s first appearance so fresh in my mind, I was happy to accept the idea that the aliens were a metaphor for cancer (as well as being real science fiction) and that this was a way Nigel had found to write about his illness ...If the book's so metaphoric of the richness of 'ordinary' life, it is tempting to reduce it to a long meditation on the fact of just having been diagnosed with cancer. But if one contents oneself with saying it's 'only' that, it does reduce the significance of the book somewhat - makes it more strictly personal than I think Cox meant it to be.

Reading the novel now, at fifty-seven, a year older than Nigel was when he died, I can still see the aliens as aliens – as character and plot. And I can still see them is something of a metaphor for cancer. Or for the interruption of life by fear of death, which throws us back on life. But now I can see whole new strata of meanings, and a book I always admired and considered intellectually and emotionally deep has flowered further in my understanding.What a coincidence! I'm 56 - due to turn 57 next month. I hadn't realised that that was Nigell Cox's age when he died. There is a certain sense, though, in which certain things come into focus as one gets older - parts even of long-favourite books begin to take on new resonance.

It seems to me now that Skylark Lounge is also a book written by someone who had, at some points in his life, a very real fear of losing his mind. I recognise this partly because between 2000, when I first read the novel, and 2006 when he died, I learned a lot more about Nigel.So it's about cancer, and mental illness, and ordinariness, and - everything really. But there's one last aspect of it, too:

Another thought I had about Jack Grout’s having been press-ganged into the job of revealing human life to aliens, and his pressing need to understand what all that actually means, is that this is the writing life. The fiction-writing life. Jack’s aliens make him go off on his own, make him secretive, vague and cold to his friends and family. Jack’s aliens are an enemy of family life, and the reliably ticking-over everyday. They put thoughts into Jack’s head that no one else can see or hear. They torture him with immanence, with things that have to be solved, with the tantalising, unsettled shimmer of a great pattern. Jack Grout’s aliens are isolating and marvellous, and they do his head in. They are the writing life. They pass through – like novels – leaving him to say, “I’m back. Sorry I was absent. I’ve had enough out, please take me back in.”That's a very writerly thought. As a fellow (albeit far more obscure) fiction-writer myself, I can see the metaphor of 'invasion by outside forces' in this way - as well as empathising strongly with Cox's sense of the neglect of this, his strongest statement to date on the simple mystery of being alive.

I guess where it takes me for my own last statement on the novel is somewhere nearer to an experience I think is available to all of us, albeit in different forms according to our own predispositions. Writers (such as Knox) might see it as inspiration; ecstatic contemplatives (such as Traherne) as visions bearing on the nature of God; Shamans as the various stages on their own interior journey.

That last is the model I think fits best with my own experience of the novel. I note the tendency for imagery of dismemberment and reassembly in accounts of the Shaman's journey to the Otherworld. I note, too, the tendency of Shamans in many cultures to embrace transsexual and culturally dissonant lifestyles.

These do seem to be the experiences (and temptations) endured by Jack Grout at the various stages of his own visionary journey. His final manifestation as a cowboy, outfitted in the tourist shops of Waiouru, commencing his long trajectory home to Wellington, would certainly seem guaranteed to disconcert, at the very least, the people awaiting him:

I'll get out my thumb. Head south. One look at Shelley's face will tell the whole story. [190]

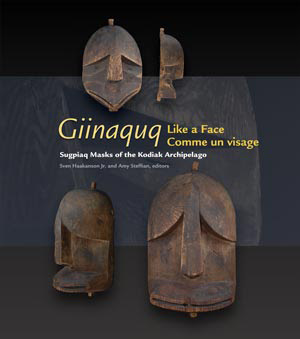

Giinaquq: Like a Face / Comme un visage (2009)

Unnuyauk / Night Traveler'Spirit helper' was originally transliterated, in 1871, as 'дьявол' [d'yavol] (Russian for 'devil'). Alphonse Pinart, the original collector of these masks, translated this as 'esprit' (French: 'spirit'). The new translators have rendered the Alutiiq word ikayuqa as 'spirit helper' - the original meaning is, however, is inaccessible. [297-98].

Why is it my spirit helper, why is it you are apprehensive of me

on the seal rocks?

I will bring you game to be caught.

I went through the inside of the universe;

my helper, that one made me afraid.

I went down where they are motioning.

- from 'Second Life: The Return of the Masks', Returns: Becoming Indigenous in the Twenty-First Century, by James Clifford (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2013): 290.

•

Nigel Cox

Nigel Cox

(1951-2006)

Select Bibliography:

Waiting for Einstein. Auckland: Benton Ross Publishers Ltd., 1984.

Dirty Work. Auckland: Benton Ross Publishers Ltd., 1987.

Dirty Work. 1987. Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2006.

Skylark Lounge. Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2000.

Tarzan Presley. [Reprinted as 'Jungle Rock Blues', 2011]. Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2004.

Responsibility. Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2005

The Cowboy Dog. Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2006.

Phone Home Berlin: Collected Non-fiction. Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2007.

Secondary Literature:

Elizabeth Knox. "Nigel Cox’s Skylark Lounge." Elizabeth Knox website (27/7/16).

Homepages & Online Information:

Wikipedia entry

Unity Books: Skylark Lounge advertisement (19th July 2000)

•

Published on October 11, 2019 15:15

October 6, 2019

Millennials (2): Dylan Horrocks' Hicksville (1998)

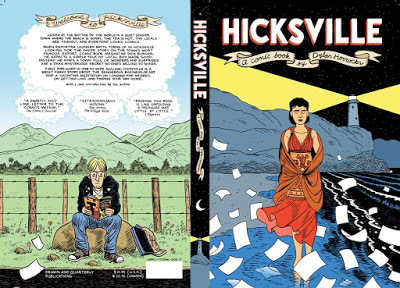

Dylan Horrocks: Hicksville (1998 / 2010)

Is Dylan Horrocks' Hicksville the Great New Zealand Novel?

That sounds like a facetious question, but it isn't meant as one.

This 'Great [...] Novel' idea stems, of course, from all the palaver about the 'Great American Novel.' Is there such a thing? Certainly there have been many attempts to write it, and many somewhat premature advertisements for its appearance: The Great Gatsby, Of Time and the River, Gravity's Rainbow - show me a great American writer, and I'll show you their entry for the elusive prize.

The problem, of course, is that the actual Great American Novel was written long before the idea gained currency. Or one of them had been, at any rate. Personally, I would argue that there are two. The term came (according to Wikipedia) from an 1868 essay by Civil War novelist John William De Forest.

Herman Melville: Moby-Dick (1851)

Candidate 1 has to be Herman Melville's Moby-Dick (1851). Among all the 19 claimants listed on Wikipedia, only this one has the necessary critical heft to have survived all the winds of fashion and the warring schools of interpretation to sail on majestically into the sunset.

It's an impenetrable, Mandarin text, written by an Easterner - a New Yorker, in fact - which is also a great adventure story spanning the world - not to mention all the depths and shallows of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. It embodies paradox - is readable and unreadable at the same time - combines libraries of quotations with poignant accounts of the simplest human interactions.

Many people don't get the point of the first, most famous sentence of the story: "Call me Ishmael." This doesn't meant that the narrator's name actually is 'Ishmael', or even that he's adopted that as a useful nom-de-plume (like 'Mark Twain' for Samuel Clemens, for instance). It means that he is a wanderer upon the Earth, like Ishmael the eldest son of Abraham - in contrast to Isaac, Abraham's younger (but legitimate) son by his wife Sarah, the patriarch of the twelve tribes of Israel.

To a contemporary, 1850s, Bible-soaked reader this would have been so obvious that Melville doesn't even trouble to explain it. We are forced to refer to the narrator as 'Ishmael' for convenience's sake, but it's a description of character, not (strictly) a piece of nomenclature.

You see what I mean? Moby-Dick invites such speculations simply because of the oddball way in which it was written. Leslie Fiedler could cause a furore in the 1960s simply by suggesting that Queequeg and 'Ishmael' really are making love in the first chapter of the books - rather than simply lying together chastely like chums. And once you've thought that unthinkable thought, it opens up a whole serious of new perspectives on the novel (cf. Fiedler's Love and Death in the American Novel).

Mark Twain: Huckleberry Finn (1884)

The real problem arises from the almost equal and opposite claims of Mark Twain's masterpiece Huckleberry Finn, which has to be Candidate 2.

Emerson, Longfellow, Lowell, Holmes - I knew them all and all the rest of our sages, poets, seers, critics, humorists; they were like one another and like other literary men; but Clemens was sole, incomparable, the Lincoln of our literature.So intoned William Dean Howells at the end of his long elegiac volume My Mark Twain (1910). Ernest Hemingway put it more simply (and quotably), in The Green Hills of Africa (1935):

All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn. If you read it you must stop where the Nigger Jim is stolen from the boys. That is the real end. The rest is just cheating. But it’s the best book we’ve had. All American writing comes from that. There was nothing before. There has been nothing as good since.The book grows and grows in its implications - with all its admitted faults - on repeated rereadings. It's hard to imagine any book so embodying the spirit of a country, or (at any rate) the spirit of both the old South and the advancing frontier.

If that isn't the Great American Novel, what is? 'There's been nothing as good since,' is the simple truth, for all the greatness of Faulkner, Fitzgerald, Hemingway himself, Toni Morrison, and all the other great novelists who have flourished on those 'dark fields of the Republic,' that shopsoiled 'green breast of the New World' (to quote The Great Gatsby).

It comes down to one of those classic oppositions: Dostoevsky or Tolstoy? Schiller or Goethe? Wordsworth or Coleridge? One would like to answer all of them with the formula: "Both - and ..." - yet it must be admitted that a sneaking preference always creeps in.

There's always one of the two whom your hand brings down more enthusiastically from the bookshelf. Sometimes it's a simple classical / romantic face-off (Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, for instance) - but such is the complexity of each of their bodies of work, that it never resolves entirely to that.

Jane Austen / Charlotte Brontë would be another, I suppose - or Lady Murasaki / Sei Shōnagon. After a while they dissolve into triads, then groups, then just the whole spectrum of colours and shades of expression ...

Mark Twain and/or Herman Melville, then, is the best I can do for that elusive entity (or should I say chimera?), the author of the Great American Novel. It's a pretty magnificent choice to be confronted by, however!

Dylan Horrocks: Hicksville (1998)

Once before I've asked this question about the Great New Zealand novel. My answer then was a bit facetious, much though I admire the intricacies of Chris Kraus's I Love Dick (1997).

Hicksville, to me, seems to present far more solid claims. In his original article, William DeForest defined the Great American novel as "the picture of the ordinary emotions and manners of American existence." He went on to say:

"Is it time?" the benighted people in the earthen jars or commonplace life are asking. And with no intention of being disagreeable, but rather with sympathetic sorrow, we answer, "Wait." At least we fear that such ought to be our answer. This task of painting the American soul within the framework of a novel has seldom been attempted, and has never been accomplished further than very partially — in the production of a few outlines.

Art Spiegelman: Maus (1980-1991)

I'm sure that Dylan Horrocks had no such lofty intentions when he set out to create Hicksville. From what I gather, it came together from bits and pieces, written and drawn at various times, very much in the mode of his great contemporary Art Spiegelman's Maus , which first appeared, piecemeal, chapter by chapter, in Raw (1980-1991), the comics magazine he co-founded with his wife Françoise Mouly.

The first volume of Maus, 'My Father Bleeds History,' appeared in book-form in 1986, the year of the great graphic novel explosion. It was one of the three groundbreaking works which appeared during 1986-87 to confound dismissive critics (as chronicled in Douglas Wolk's 2007 book Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work and What They Mean).

Frank Miller: The Dark Knight Returns (1986)

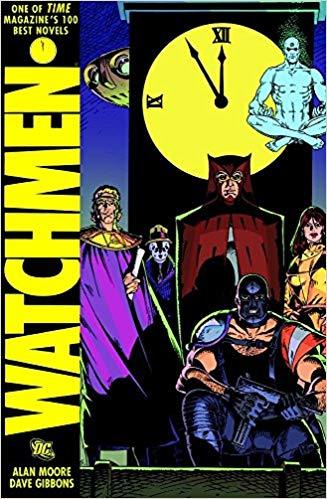

They were (in no particular order), Spiegelman's Maus: A Survivor's Tale, Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns , and Alan Moore's Watchmen .

Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons: Watchmen (1986)

I suppose if you live in a cave you might have avoided encountering any of these classic works. The film of Watchmen (in its various versions) is more illustrator Dave Gibbons' gig than Alan Moore's - it left out one of the graphic novel's crucial subplots - although an animated version of this, a pirate story, was released separately. It's a critique of superhero comics (as Don Quixote is a critique of novels of chivalry), but that's only one of the many things it does.

The Dark Knight Returns is only loosely connected - more on a thematic than a plot level - with Christopher Nolan's 'Batman' film trilogy, though it's hard to imagine the latter existing without the former. It's the most conventional of the three, though Frank Miller's subsequent projects 300 and Sin City show that he, too, is a creative force to be reckoned with.

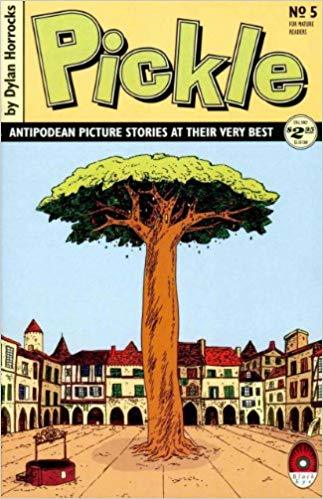

Dylan Horrocks, ed.: Pickle (1993-1997)

The second volume of Spiegelman's Maus, 'And Here My Troubles Began,' appeared in 1991. Dylan Horrock's Hicksville began to be serialised in the second volume of his magazine Pickle, devoted to 'the finest in New Zealand comics', in 1993.

When I met Dylan Horrocks at the 2018 Manawatu Writers' Festival, he told me that in many ways he still considered that the best way to read the novel: in its original serialised form, surrounded by other comics, and all the other contextualising bits and pieces by him and other artists which had to be edited out in book form.

I tried to explain to him something of what Hicksville had meant to me when I first read it in the late 1990s (I was late to Pickle, unfortunately, though I certainly followed his Milo's Week strip comic which ran in the NZ Listener between 1995 and 1997).

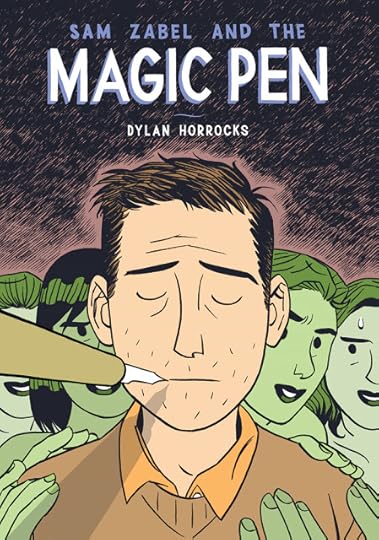

Hicksville was an achievement of another order, however. And - much though I enjoyed its follow-up, Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen (2014), it couldn't really be said to have quite the same heft. But then, the same could easily be said of Twain and Melville's follow-up books: respectively, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (1889), and Pierre, or the Ambiguities (1852)).

Dylan Horrocks: Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen (2014)

So what did speak to me so powerfully in Hicksville? First of all, it was a piece of identity literature: intimately bound up with the problem of what it is to be a Pākehā New Zealander - stuck in what seems to be the wrong hemisphere, with the wrong cultural conditioning, and yet with an increasingly powerful sense of place and identity.

The strip comic with Captain Cook, Charles Heaphy and Hone Heke included at various points in the narrative gives a perfect metaphor for this sense of cultural drift - not quite knowing where you are, but engaged - consciously or unconsciously - in learning how not to worry too much about the fact.

There are nice vignettes of exile, too: strip comics drawn on the kitchen table in a London flat, side-trips to Eastern European countries to pick up on their own complex comics traditions - not to mention Sam's phantasmagorical journey to Hollywood to see the world of his alter-ego / nemesis Dick Burger close-up ...

Above all, Hicksville is a comic obsessed with comics. Everyone in the imaginary town of Hicksville, set on the tip of East Cape, reads comics all the time, and is intimately knowledgeable of their strange, compromised history: caught between the devil of commercialism and the deep sea of unfettered artistic experimentation.

And then there's that Name of the Rose-like secret library of manuscript and limited edition comics, including the greatest works of the greatest creators, the ones that they longed to write, but somehow never managed to, stored in the old lighthouse on the point, watched over by the enigmatic Kupe.

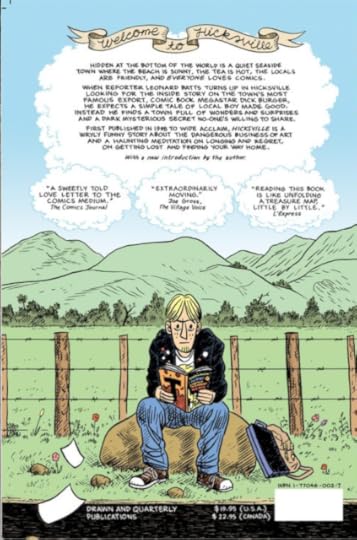

Dylan Horrocks: Hicksville (1998 / 2010)

Into this situation comes Leonard Batts, an American comics journalist, author of a biography of Jack Kirby, who is investigating the latest comics sensation, Dick Burger, by paying a visit to his mysterious Antipodean hometown. (I don't know if the resemblance between his name and that of Leonard Bast, the hapless victim of class snobbery in E. M. Forster's Howards End (1910), is intentional or not, but given the general level of erudition in Dylan Horrocks' work, it wouldn't surprise me at all ...)

Dylan Horrocks: Hicksville (1998)

There's a lovely sense of recognition when the comic reenacts a classic scene from John O'Shea's pioneering NZ film Runaway (1964) to herald Batts's arrival in town. Things only come into existence the moment they're written about - or filmed, or drawn - in this novel, and such imaginative acts appear to be stored forever in some kind of Akashic tablets of the soul. That, at any rate, is how I read the book's overall message.

Is it strictly a work of speculative fiction, could one say? That's harder for me to answer. Certainly the fact that it's set in an impossible place - a town in a parallel universe (not unlike the one in Moore's Watchmen, where Nixon gets perpetually re-elected, and pirate comics have the place superheroes hold in our reality) - would appear to substantiate the claim.

It's less realist at its roots than either Moby-Dick or Huckleberry Finn: that much is certain. Less, too, than any of its possible rivals for 'Great New Zealand Novel': the bone people ? The Lovelock Version ? The Matriarch (either in the original or in its rewritten version)?

However you classify its genre, for me Hicksville holds all the aces: it's funny, sad, wise, intricate, and incorrigibly from here. It took a long time for the Americans to notice what they had in Melville - not to mention the fact that Mark Twain was something far more than a clown. I hope it doesn't take us quite so long to see the merits of Dylan Horrocks' masterpiece.

Dylan Horrocks: sketches (2012)

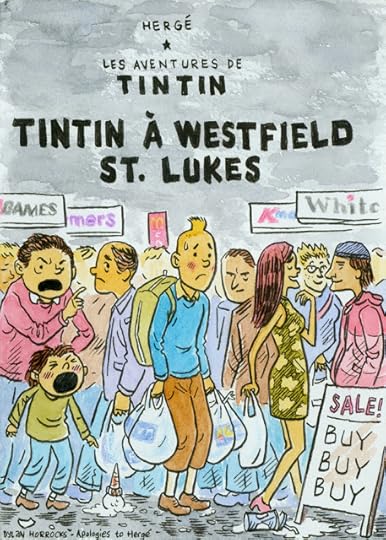

The latest, 2010, edition of the comic includes a wonderfully elegiac introduction. In it Horrocks charts his earliest comics influences - Charles Schulz's Peanuts, Carl Barks' Donald Duck, but above all Hergé's Tintin.

Talk about the landscape (or dreamscape) of my life! I, too, grew up on those comics: Tintin and Asterix, Peanuts and Eagle (my father's particular favourite) - though for us the unquestionable pinnacle was occupied by the seemingly endless permutations of Carl Barks' imagination - even though we didn't even (then) know him by name.

Perhaps, then, I should admit that I am prejudiced. Comics may not be the all-consuming passion for me that they are for Dylan - just one amongst a number of loves - but I understand (and can share) the magic of childhood associations he evokes so well in the Hicksville corpus as a whole.

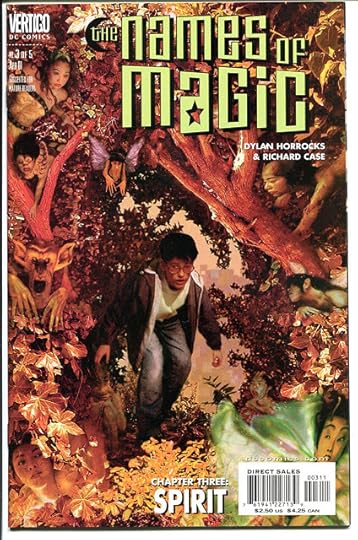

Dylan Horrocks & Richard Case:

Funnily enough, the introduction also touches on his Dick Burger-like decision to get involved in the mainstream comics industry: his work on Timothy Hunter and Batgirl and other titles from Dc's edgier arm Vertigo. As he himself puts it:

The money was great and I worked with some nice people ... but the stories didn't come easily. For the first time in my life I was making comics I couldn't respect. As time went on it grew harder and harder to write or draw my own comics. Soon just looking at a comic - any comic - filled me with dread ... I could no longer see the point of it all ... I should have listened to Sam. [viii]

Dylan Horrocks: Incomplete Works (2014)

Twain and Melville, too, suffered through their long nights of the soul. Both of them ran into a creative doldrums after the supreme effort of their great novels. It was good to see Dylan Horrocks back on the bookshops again in 2014 with the double-whammy of Incomplete Works and Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen. It seems he has learned to listen to Sam again, after all.

Dylan Horrocks: Hicksville (1998 / 2010)

•

Dylan Horrocks (2019)

Dylan Horrocks

(b. 1966)

Select Bibliography:

Hicksville: A Comic Book. 1998. Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly, 2001.

Hicksville: A Comic Book. 1998. New Edition. Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2010.

The Names of Magic. Illustrated by Richard Case. 2001. New York: Vertigo/DC Comics, 2002.

New Zealand Comics and Graphic Novels. Wellington: Hicksville Press, 2010.

[available for download as a pdf here].

Incomplete Works. Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2014.

Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen. Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2014.

Homepages & Online Information:

Author's Homepage

Wikipedia entry

Dylan Horrocks

•

Published on October 06, 2019 13:34

October 4, 2019

Millennials (1): Harry from the Agency (1997)

Philip Gluckman: Harry from the Agency (1997)

I don't know why he saved my life. Maybe in those last moments he loved life more than he ever had before. Not just his life... anybody's life... my life. All he'd wanted was the same answers the rest of us want. Where do I come from? Where am I going? How long have I got? All I could do is sit there and watch him die.

- Wikiquotes

Hampton Fancher & David Peoples: Blade Runner (1982)

Most purists can’t stand the original theatrical release version of Blade Runner, with the intrusive voice-over and the soldered-on happy ending. If that’s the first version of the movie you saw, though (as it was for me), things can seem a bit different.

Some bits of it work pretty well – like the one above, for instance.

I guess that the point of these NZSF essays of mine is somewhat similar – Where did we come from? Where are we going? How long have we got? Does it really matter if New Zealand can claim its own independent SF tradition? Well, I guess that to a dedicated fan, everything matters.

If it gives you a kick - as it does me - to read about a long grey space ship descending over Remuera Rd in Philip Gluckman's Harry from the Agency, then you'll understand what I'm getting at. If not, well:

Breathes there the man, with soul so dead,

Who never to himself hath said,

This is my own, my native land!

- Sir Walter Scott, 'The Lay of the Last Minstrel' (1805)

James Hogg: The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824)

I felt it in Scotland, first, when reading James Hogg's strange, mad Gothic novel The Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824). The streets his hero trod, the fields on top of Salisbury Crags where he saw his vision of the devil, were familiar to me from my everyday wanderings through Edinburgh.

It's a city that stays, for the most part, the same: the same street layout, the same landmarks. It's definitely strange to be able to retrace someone's steps like that when you hail from a New World city like Auckland, one that rebuilds and reinvents itself every few decades: a bit like Blade Runner's futuristic-yet-retro LA, in fact.

Frank Sargeson: That Summer: Stories. Cover by John Minton (1946)

But then, when I picked up an old edition of Frank Sargeson's That Summer on an Edinburgh bookstall, the fascination with the country of my ancestors, Scotland, shifted slowly to a nostalgia for my own native land - New Zealand.

It's true that That Summer portrays a past so distant, even for me, that it has few connections with the Auckland I remember - but so poignant and beautiful was the story that I've never been able to get out from under its spell ever since. It's my benchmark for a completely successful New Zealand novella: a great and moving story by anyone's standards.

William Gibson: Neuromancer (1984) [German edition]

None of this helps us directly with Harry from the Agency, I suppose, but perhaps it helps to explain why the book has such a powerful charm for me. It's a piece of Kiwi cyberpunk, of course - brewed up from a set of ingredients readily located in the complicated zone between Blade Runner and William Gibson's immensely influential debut novel Neuromancer.

And what is Neuromancer about? It's the first book in the 'Sprawl' trilogy, completed in Count Zero (1986) and Mona Lisa Overdrive (1988). It introduces a world of world-weary Chandleresque antiheroes, roaming through strange city landscapes - half ecological devastation, half virtual reality - and their equally world-weary (but super-cool) girlfriends.

The epitome of all these is the streetwise 'Razorgirl' Molly Millions whom burnt-out hacker Henry Case hooks up with in the novel, and under whose protection he undertakes his dangerous mission into cyberspace (a term Gibson is credited with coining).

William Gibson: Neuromancer (1984) [Brazilian edition]

[Warning - numerous plot-spoilers ahead]

Sound familiar? For Gibson's protagonist 'Henry Case,' read Gluckman's "Harry Stone' - both drug addicts, both drifters, both selfish almost to the point of insanity. For Gibson's 'Molly Millions,' read, on the romantic side, Gluckman's lithe, long-suffering brunette heroine Toni; on the genetic modification side, the ninja space-assassin Miyuki.

So much is obvious. But the fact that the tropes of cyberpunk are so essentially repetitive as to be easy to replicate - whether in movies such Johnny Mnemonic or The Matrix, or in novels such Lucius Shepard's Life During Wartime (1987) or Bruce Sterling's Islands in the Net (1988) - doesn't mean that there are no meaningful distinctions to be made between these works.

Like the Gothic novel, Cyberpunk used stereotyped motifs to ever more complex ends. The seeds of its destruction lay mainly in the fact that the future it gestured to so beguilingly is now upon us. What its writers assumed would take decades or centuries to accomplish has fallen in on our heads in a matter of a few years.

William Gibson & Bruce Sterling: The Difference Engine (1990) [Brazilian edition]

In that respect, William Gibson's other great generic breakthrough, Steampunk - as outlined in his novel The Difference Engine, jointly written with Bruce Sterling - may yet prove to be more enduring.

Philip Gluckman: Harry from the Agency (1997)

Third generation of NZ doctors - an old family curse. Keen musician, my novel "Harry from the Agency" is available in all libraries. Absolutely love my job and I have a special interest in treating patients with Hyperhidrosis.According to WebMD, "Hyperhidrosis, or excessive sweating, is a common disorder which produces a lot of unhappiness." I'm not quite sure how it connects with Harry from the Agency, but certainly Harry does a good deal of sweating in the course of the narrative - principally because he's a junkie hooked on heroin, whose horizon is pretty much defined by the prospect of his next fix.

- Dr. Philip Gluckman, 'About.' Albany Family Medical Centre

To add insult to injury (or perhaps to provide Dr. Gluckman with some plot points where he can really use his professional expertise) Harry is also infected with the appalling flesh-eating Delta-8 virus. Rather than offering up hints, though, it might be better simply to quote the book's blurb:

2205 AD. Global warming has accelerated out of control. The middle of the planet is lifeless, drenched in steamy, poisonous rain. Auckland has become a city of islands, and Antarctica is home to most of the world's population. Multinational corporations have deserted Earth to create planetary empires. The Delta-8 virus, a consequence of deep space exploration, is a plague upon the remaining inhabitants.

For Dr Harry Stone, medical section, World Intelligence Agency, time is running out. Not only does he have the virus, the narcotic supply that sustains him is coming to an end. And as his world is failing, Harry is faced with a choice.

Harry from the Agency reveals a convincing future rife with corruption. With its noir atmosphere this book will especially appeal to fans of William Gibson.

Philip Gluckman lives in Auckland. This is his first published novel.

Charlize Theron as Aeon Flux (2010)

Harry from the Agency got a somewhat mixed reception when it first appeared towards the end of the 1990s. I remember hearing a radio review where the two (female) commentators were immensely scornful of Gluckman's heroine Toni. And it's true that, in appearance at least, she sounds a bit like a foretaste of the movie version of Aeon Flux. Slightly more subtle than the animated TV show, but not by much:

Aeon Flux (MTV: 1991-1995)

Toni sat on the floor. Her sky-blue dressing gown, wrapped tightly around her, concealed perfect skin. Even a casual observer would have been drawn to the fullness of her lips. [16]

She changed into skintight trousers and a jacket over her white singlet, her boots, ran down to her new Triumph, threw on her shades and chopped it into gear. [187]Actually Toni can't even sit at a computer console without looking sexy:

'Something up?' Jackson's baritone voice bellowed from behind the lithe figure, sitting hunched forward over her knees, both feet up on the console, her company jacket off and slung casually over the back of the chair. [135]

cyberpunk hero

It wasn't really the fact that Toni was so cool (and so hot) that irritated the two radio commentators. It was the fact that she put up with so much from Harry without any obvious return. He had, after all, left her behind to die on a battlefield - though he does have a few weak-kneed excuses for that.

What's more, for all the latent altruism she detected in him - free clinics for the poor, etc. - his main preoccupation throughout is getting more drugs to feed his habit.

'Why,' Robert Graves once asked, 'have such scores of lovely, gifted girls / Married impossible men?'

Simple self-sacrifice may be ruled out,Toni hasn't actually married Harry, but she certainly puts up with more from him that would seem to make any sense. Robert Graves seems no wiser than the rest of us as to why that might be, however, so I guess we just have to accept it as one of the paradoxes of life (or, as in this case, self-indulgent fiction).

And missionary endeavour, nine times out of ten.

Repeat 'impossible men': not merely rustic,

Foul-tempered or depraved

(Dramatic foils chosen to show the world

How well women behave, and always have behaved).

Impossible men: idle, illiterate,

Self-pitying, dirty, sly,

For whose appearance even in City parks

Excuses must be made to casual passers-by.

Has God's supply of tolerable husbands

Fallen, in fact, so low?

Or do I always over-value woman

At the expense of man?

Do I?

It might be so.

- 'A Slice of Wedding Cake'

Visit Arrakis: Dune Tours

A good deal of the novel is set on the desert planet Alterrin-3. With its muezzin, and its mad AI cyber-sultan, this planet could certainly be said to have a certain amount in common with the more famous Arrakis (aka 'Dune'), beloved of Frank Herbert fans everywhere.

And, as with Paul Atreides, Harry too goes to ground among a group of indigenous desert people, whose wounds he tends, and who therefore prove willing to assist him in his self-appointed task of broadcasting to the universe the cure to the Delta-8 virus which its creators are trying to suppress.

There's also a galactic empire in the mix: a little like that of the Padishah Emperor, Shaddam IV (or, really, like any other Galactic empire in SF: from Servalan's in Blake's Seven to the one Darth Vader manages in Star Wars). This one is run by Maximilian Oesterburg III - with somewhat less than Teutonic efficiency - for the benefit of his eight-year-old heir, and is, like all corporate entities great or small, devoted to profit and the bottomline over all.

Brian Aldiss, ed. Galactic Empires (1975)

So why should you read this book? It does, after all, consist mainly of a shuffle of the major SF trumps, laid out in a not-unconventional order. Perhaps that's why it's had no (published) sequels, either.

Gluckman writes well. He writes very well. And one can't but feel a strong personal involvement with Harry and Toni which endows them with a certain extra-textual solidity. Harry is a fairly self-indulgent self-portrait, I suppose, but he does have enough defects - alongside a few good qualities - to feel like an actual human being much of the time.

Is the same true of Toni? It's hard to say. But she's certainly no more implausible than Rachael in Blade Runner, Chani in Dune, Molly Millions in Neuromancer, or any of the other razorgirl babes who infest cyberpunk - as well (I suppose) as SF in general.

Strangely enough, it's in its settings that Harry from the Agency really comes alive. Alterrin-3 may not have the solidity of Dune, but it does have an Australian outback feel to it which makes it seem very much like a plausible place.

The islanded Auckland of the future is good, too. Gluckman is wise enough not to indulge in too many Ballardian evocations of the vista, but the hints he drops here and there are enough to give it a solid presence in the mind.

Desert Gardens Hotel

Like most SF futures, Harry from the Agency probably errs on the side of optimism. It's taken quite some time for the ice-caps to melt, after all - and there's only one really incurable plague ravaging the population.

William Gibson, too, has had difficulties with sequels. So powerful was the vision of Neuromancer, that it overshadows everything he's produced under his own name since. Only the collaborative Difference Engine could be said to have matched it.

Perhaps Philip (for a moment I was tempted to call him 'Harry') Gluckman was wise to stop at one novel. It is, after all, extremely accomplished in its own right, and to repeat it would be to risk undermining the effect.

I could easily imagine him writing something else, though, something completely different, possible even out of the speculative fiction mode. Harry from the Agency is auspicious enough as a debut to persuade me that it's a lot more than just another Neuromancer / Dune knockoff transposed to downtown Auckland.

Welcome to 2100: Auckland’s futuristic look!

•

Dr Philip Gluckman

Philip Gluckman

Select Bibliography:

Harry from the Agency. Reed Books. Auckland: Reed Publishing (NZ) Ltd., 1997.

Homepages & Online Information:

Albany Family Medical Centre

•

Published on October 04, 2019 14:17

September 24, 2019

Spirit of '92: Albert Wendt's Black Rainbow

Albert Wendt: Black Rainbow (1992)

'... I don't mind admitting I'm scared ...' I reached out and put an arm around him. 'It's times like these you need ...'

'Minties?' Fantail completed his remark.

'No, it's times like these you need a sense of humour,' Aeto said.

'And our family,' I added. My mother's handprints were still warm on my face.

- Albert Wendt, Black Rainbow (Auckland: Penguin Books, 1992): 235.

Black Rainbow is a difficult book to characterise. It moves like a thriller: first-person narration of reckless escapes and knife fights with a variety of opponents, almost invariably cribbed from other fictions - 'Sister Honey' from Janet Frame's Faces in the Water, 'Big Nurse' from Ken Kesey's One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, Maneco Uriarte from Jorge Luis Borges' Gaucho-esque story '' ...

There's an almost manic lack of consistency about its tone, however: no po-faced hard-boiled intensity can survive exchanges like the one quoted above, where the speakers move from portentous invocations of whakapapa to quotations from ad jingles.

So what's it all about? On the one hand, it's about the erasure of history: the losses (and gains) we achieve by simply writing off the past: