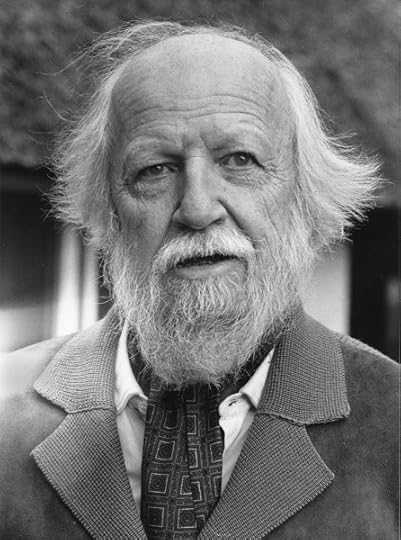

Jack Ross's Blog, page 13

April 29, 2021

Takapuna Poetry Tour - Saturday 8 May, 2-4 pm

Takapuna Poetry Tour (8/5/21)

If you're at a loose end next Saturday, why not try one of the walks in Auckland's Urban Walking Festival? In fact - hint, hint - you might choose the one that I'm involved with, the Takapuna Poetry Tour.

The walk is free, but you're asked to book at this link to give some approximate idea of numbers. Here's Festival Director Melissa Laing's description of the event:

Urban Walking Festival 2021

In the mid 20th Century Takapuna was the home to many of New Zealand's significant writers, poets, and playwrights, including Frank Sargeson, Bruce Mason, Janet Frame, and Karl Wolfskehl. The works they wrote influenced the shape of New Zealand literature for generations to come. The Takapuna Poetry Tour features writers performing poems in response to Takapuna’s literary history and urban future. Join us for spoken word and poetry on the streets.

Our poets include: Zak Devey, Amèlia Homs Ferrer, Renee Liang, Elizabeth Morton, Kiri Piahana-Wong, Ruby Porter, and Jack Ross.

Duration: 90 min

Access: Wheel Accessible

The Takapuna Poetry Tour is part of a day of activities presented in partnership with 38 Hurstmere, including films screened on site.

•

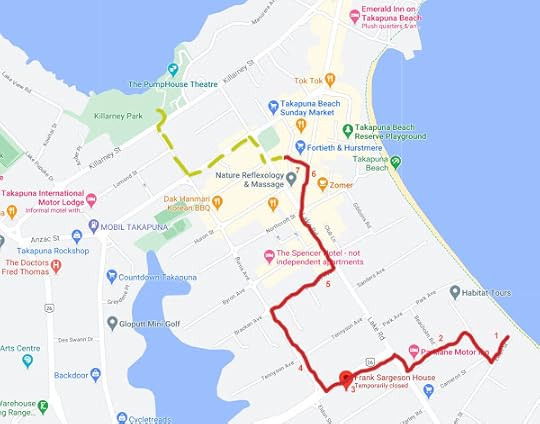

As you'll see from the map above, there are approximately 8 stops on the route, at each of which one of us poets will regale you with a short performance of one of our (Takapuna-related) works.

I have to say, Shore-ite though I've always been, I did find it a bit challenging to locate any specific references to Takapuna in my collected works, so have decided to settle instead for something more generically "North Shore" in inspiration.

I shall be stationed at stop 3 on the tour, the Frank Sargeson House at no. 14A Esmonde Road. I'm told that we'll be reading in the garden, as his bach is closed for refurbishment at present. I have to say that I'm hoping devoutly that it doesn't rain, as there's no real shelter anywhere near.

The proposed stops are as follows (at present - they're still subject to change on the day):

Bruce Mason: The End of the Golden Weather, dir. Ian Mune (8/5/21: 12-3 pm)

Takapuna Beach / Bottom of Ewen Street - Bruce Mason's Home

Mason moved to Takapuna at the age of 5 and lived in Ewen St from 1926 until 1938.

Paul Estcourt: Kevin Ireland (2007)

9 Rewiti Ave - Kevin Ireland's home in the 1940s

Frank Sargeson House (2006)

14A Esmonde Rd - Frank Sargeson House

Janet Frame also lived here in a shed in 1955-56, while she worked on her first novel, Owls Do Cry. We'll be reading in the garden, as the house is closed at present.

Rachel Barrowman: Mason (2004)

24 Tennyson Ave - R. A. K. Mason's house

We'll do the reading in the car park of 22 Tennyson Ave, which is a medical cannabis practice beside Mason's old house. NB: Karl Wolfskehl also lived near here, on the corner of Burns Ave and Bracken Ave.

Takapuna Tennis Club

Takapuna Bowling Club and Tennis Courts - not yet confirmed

Brett Graham: Mataoho Wall (2012)

Hurstmere Green Park

This space was built in 2013 as part of a revitalisation of Takapuna, creating better town centre beach connections. It contains a text work: "Story Wall,” by Brett Graham, which concerns the myth of the origins of Lake Pupuke and Rangitoto.

38 Hurstmere

38 Hurstmere

"A transitional space and home for tactical urbanism and placemaking, the first phase of a redevelopment of public land in Takapuna’s City Centre – a place for all of Takapuna.”

Christine Young: Soapbox (2019)

Soap Box, Killarney Park - (a possible extension to the walk)

This sculpture was made to mark 125 years of women's suffrage

•

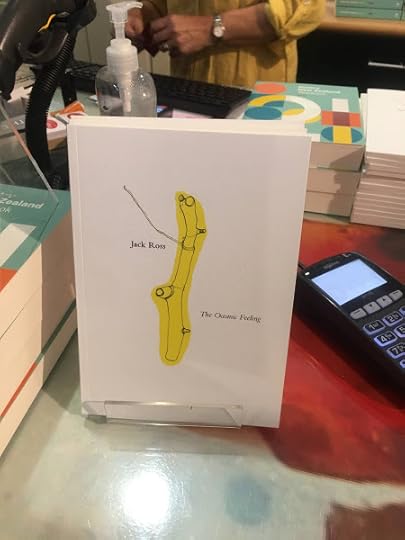

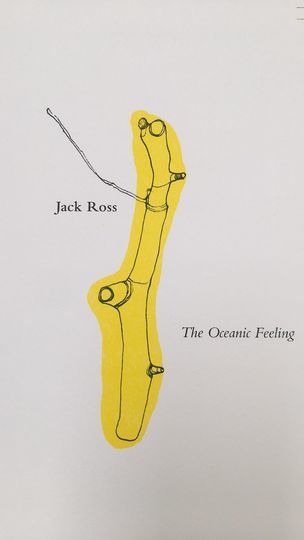

Jack Ross: The Oceanic Feeling (2021)

Actually, I tell a lie, I have managed to located a poem from my latest collection, The Oceanic Feeling, which references some of my feelings about Takapuna. I'm not sure that it's entirely appropriate to the occasion, though, so will include it here instead:

Anthony Minghella, dir.: Truly Madly Deeply (1991)

Rather a shock

i.m. Alan Rickman (1947-2016)

to think it’s been 25 years since

Truly Madly Deeply

1991

my sister died

or rather

killed herself

so hungry ghosts

seemed documentary realism

to me

living by Lake Pupuke

with its gigantic eels

and those students next door

who had to pump up the stereo

to psych themselves

into going out

every evening

1991

an unhappy time

as Rickman said

roles win Oscars

actors don’t

that swing inscribed for

Alice who used to play here

that makes the other parents

hold onto their kids

so tight

as though death were an infection

they might pick up

Te Ara: Lake Pupuke

Published on April 29, 2021 16:44

April 15, 2021

Tracey Slaughter: Devil's Trumpet

Tracey Slaughter (15-4-21)

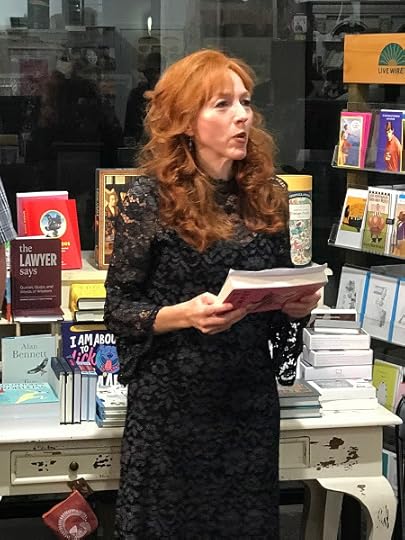

[All launch photos by Bronwyn Lloyd]

It was a dark and stormy night in Kirikiriroa. There were roadworks outside Mercer which delayed us by half an hour or so, but when we finally got to Poppies Bookshop, a block back from Victoria Street, we found that the faithful had not deserted the cause. Once again, the place was overflowing with people.

Tracey's publisher Fergus Barrowman had come up from Wellington. Bronwyn and I had come down from Auckland. It was students from Waikato Uni and the local literati that really packed the space, though. I could hardly hear myself think!

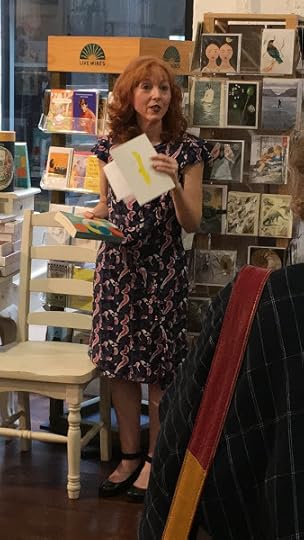

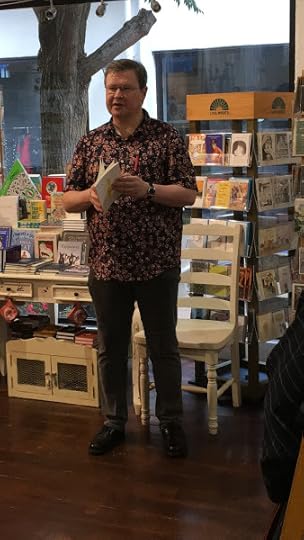

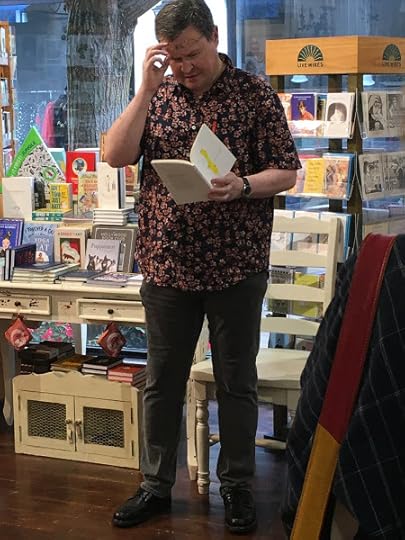

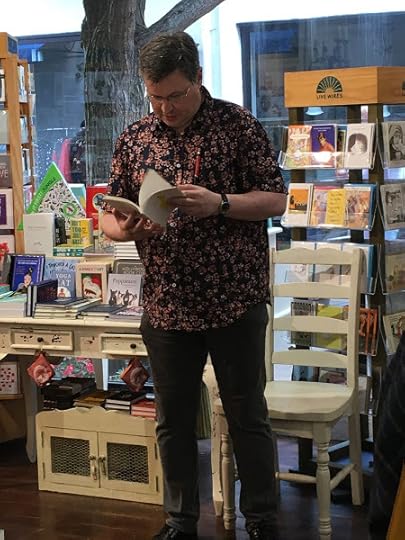

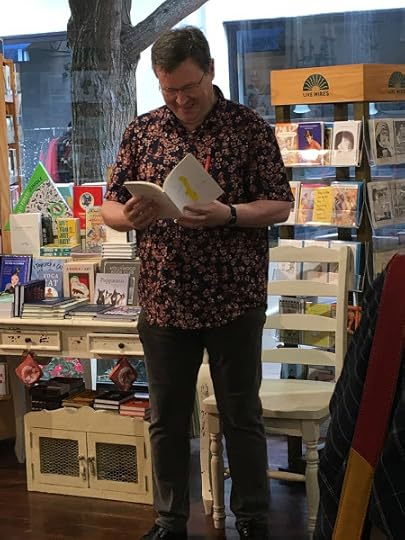

MC Jack Ross reads out his launch speech

You'll notice Tracey's new book in the foreground of the picture above.

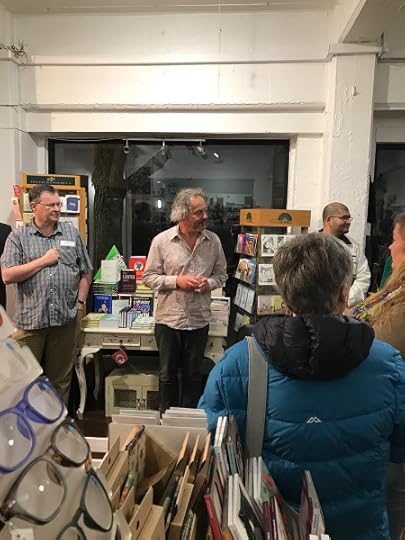

VUP Publisher Fergus Barrowman speaks about Tracey's book

Fergus was as witty as ever, quoting from the recent Spinoff article by Catherine Woulfe which lists "The sexiest lines from New Zealand’s sexiest new book, Devil’s Trumpet."

"Publicity like this is music to a publisher's ears," as he said.

Dave Taylor & Jack Ross

Here I am beside Tracey's Mayhem co-editor and long-time literary accomplice, Dave Taylor.

Fergus Barrowman with VUP authors Catherine Chidgey, Tracey Slaughter & Essa Ranapiri

And here's my launch speech for the book:

•

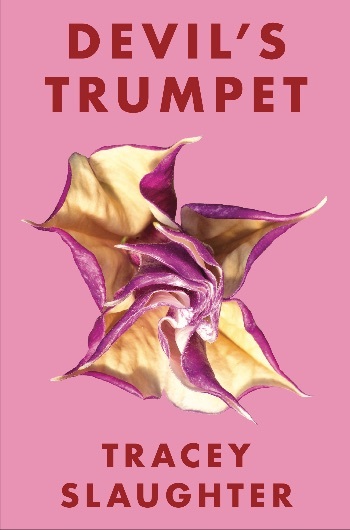

Tracey Slaughter: Devil's Trumpet (Wellington: VUP, 2021)

What do dead girls talk about? They don’t ever talk to me.

– “ladybirds” [169]

We have a stage three creative writing course at Massey University, where I work, called "Starting Your Manuscript." The course is designed to ask students to analyse the kinds of decisions authors make when creating a book-length collection of stories or poems. The intention, of course, is to get them to apply the same thinking to their own writing.

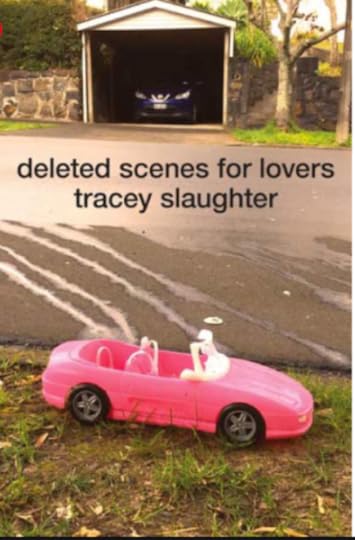

When I was asked to contribute one example of a thoroughly thought-through collection to the course materials, I realised that – among the contemporary New Zealand writers I was determined to get the students to focus on – only one book stood out for me: I accordingly chose Tracey Slaughter's 2016 book of short stories deleted scenes for lovers.

Tracey Slaughter: deleted scenes for lovers (Wellington: VUP, 2016)

I still think that's a marvellous book, and every time I look through it I'm struck at how well it builds up a collective sense of atmosphere, and how thoroughly it paints the small-town New Zealand backdrop of most of the stories. Some of the individual pieces – “Consent,” for instance – strike like lightning bolts, but they strike a prepared audience, in a carefully prepared context.

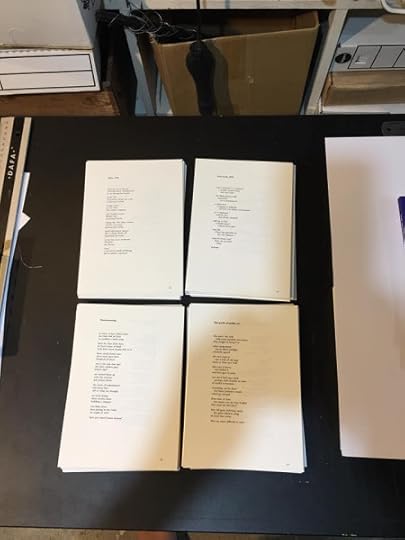

Her new book, Devil’s Trumpet, is better. I have to say that that came as a bit of a surprise to me when Tracey first lent me the typescript. At most I guess I was expecting something as good as 'deleted scenes'. But there are some extra points about this one which work very much in its favour.

Tracey Slaughter: The Longest Drink in Town (Auckland: Pania Press, 2015)

Deleted scenes for lovers, as a collection, was focussed around the separately published, tour-de-force piece The Longest Drink in Town. I love that story, its multiple plotlines, its central, terrible incident, too tragic, almost, to be spoken aloud.

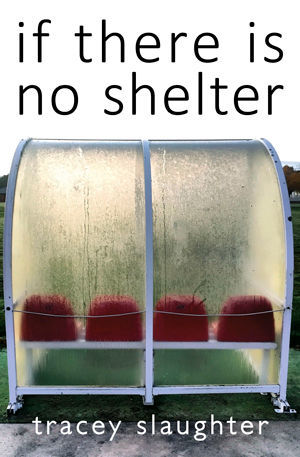

Tracey Slaughter: if there is no shelter (UK: AdHoc Fiction, 2020)

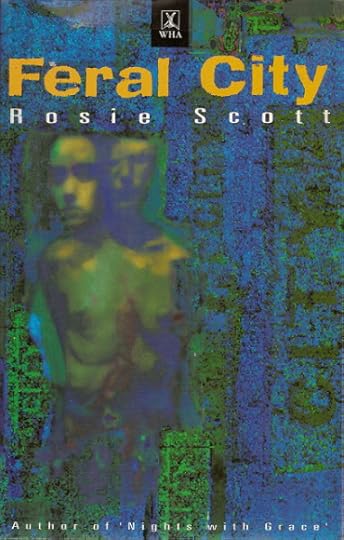

This time, too, Tracey has focussed her collection around the novella-length story if there is no shelter. That story is atmospheric in the extreme. Despite its being set in an unnamed city (possibly not a million miles from here), which has recently suffered a catastrophic earthquake, and despite the dark love story it tells, it reminds me more than anything of Rosie Scott's classic 1992 novel Feral City, set in a phantasmagoric future Auckland, ravaged by the economic reforms of the late twentieth century. And, as in that novel, small-scale human relationships are all that retain any value among the rubble of the past.

Rosie Scott: Feral City (1992)

Over the past few years, Tracey has been experimenting more and more with flash fiction. Partially, I guess, because it's become such a popular form here in New Zealand and worldwide, but mainly (I suspect) because in it she can combine the intensity of her stories with the cut-throat verbal directness of her poetry.

As I started to read the typescript of her new collection, I followed my usual practice of rationing myself to two stories per night. I can't read much more than that without losing focus on the individual scenes and characters. That was how I first read deleted scenes for lovers, and I assumed that the same technique would work with Devil's Trumpet.

Not so. It might sound like a small point, but it's one of those technical decisions which can be devastatingly effective in context. I’d read a long story, then start the next one, subconsciously drawing in breath for another long haul, only to find that it stopped at the bottom of the page!

Nor was it as simple as alternating ‘normal’-length stories with flashes. Sometimes Tracey puts three short pieces in a row, other times only two. The longer ones, too, come in twos and threes. You never know that you’re going to get next.

That's what I mean by really shaping a manuscript. I'd read many – by no means all – of the stories before, but the layered, textured way they were folded into the mix made the book as a whole seem more like the product of a single creative impulse than the more familiar showcase for many different moods.

Fata Morgana mirage

The book is devastatingly easy to read. It beguiles you in, like a fata morgana into a haunted wood where you literally have no idea where you're going to end up.

So what are the high-points those of you who’ve just bought – or are about to buy – this book are going to experience? Well, besides that beautiful, meditative, central novella, there are mosaic stories such as “postcards are a thing of the past” or “some facts about her home town”. Then there are the teasing complexities (perhaps particularly for those of us in the trade, but really for all attentive readers) of such stories as “point of view” or “stage three.”

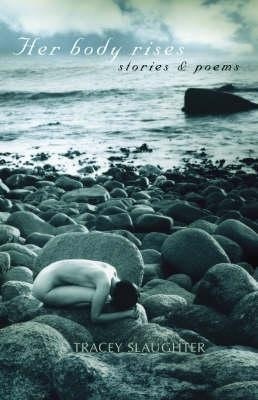

Tracey Slaughter: Her body rises (Auckland: Random House, 2005)

No doubt these stories are the products of many moods, at many times. And yet here they seem unified, not disparate. Another thing I particularly liked about the structure of the book was its return to the alternating strobe effects of Tracey’s first book Her body rises (2005).

There the alternation was between stories and poems, which certainly had the effect of showcasing each individual piece. That difference in genre did give it a somewhat start-stop effect at times, admittedly, but I still think that it's one of the crucial components which has led to the breakthrough of this, her latest book.

Mind you, I'm not saying that if I (for example) were to alternate short pieces and longer stories, it would necessarily have the same effect. This is certainly not a panacea for writers grappling with similar basic problems of unity-in-diversity.

All the work here, whether it be one, a dozen, or fifty pages long, includes the verbal economy-in-exuberance and precise plot machinery we’ve come to associate with a Tracey Slaughter story. But the jump-cuts and unpredictable blindsiding each time one turns a page makes this her most inexhaustible box of delights to date: be they devilish (as the title suggests) or heavenly (as I myself prefer to believe).

To return to the quote I opened with, “What do dead girls talk about?” They may not ever talk to me, but they do seem to talk to Tracey Slaughter, and this book constitutes some of her transcripts from the edge.

[6-13/4/21]

Tracey Slaughter

Published on April 15, 2021 12:51

April 11, 2021

The Mysteries of Auckland: H. P. Lovecraft

Upper Queen St. from West St. (7/4/21)

photograph by Bronwyn Lloyd

We took the bus into town last Wednesday - Bronwyn to deliver some beautiful new textile works for a group show at Masterworks Gallery on Upper Queen Street, and me to have a snout around the famous Hard-to-Find Secondhand Bookshop, which is literally just around the corner in St. Benedict's Street.

Mark Dery: Born to be Posthumous (2018)

Among the books I bought was a biograpy of Edward Gorey, whose work I've been collecting for a number of years now.

Edward Gorey: Amphigorey (1972)

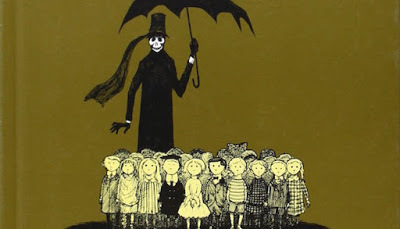

For those of you unfamiliar with the name, Edward Gorey (1925-2000) specialised in strange little picture books, set in a kind of sub-Victorian haze, which chronicled the unfortunate fates of various hapless individuals, mostly orphan children.

Edward Gorey: The Gashlycrumb Tinies (1963)

If that sounds a little macabre, it is. If it also sounds reminiscent of such works as Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events, or Ransom Riggs' Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children, then that's no accident. Both authors admit a considerable debt to Gorey's work, as does Tim Burton, many of whose films also display his unmistakable influence.

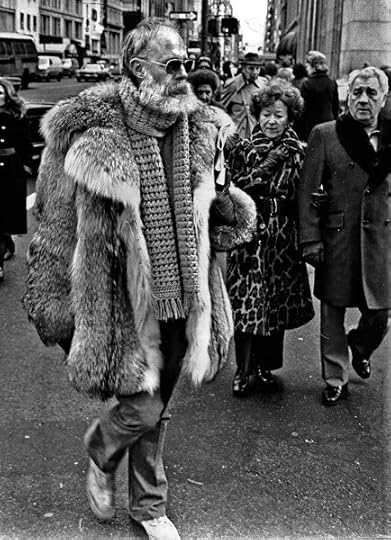

NY Times: Edward Gorey (c.1970s)

Gorey, who lived a life of high camp and preposterous eccentricity (as chronicled in an earlier book of interviews with him, Ascending Peculiarity), was certainly one of the great originals of the twentieth century.

Karen Wilkin, ed.: Ascending Peculiarity (2001)

It's no surprise, then, when things begin to take on a rather Gorey-esque atmosphere after even the slightest encounter with his work.

•

West Street: No Exit (7/4/21)

photograph by Bronwyn Lloyd

We were, as I said, in Upper Queen Street, walking down towards K Rd, on the other side of the Southern Motorway. At this point I spotted the sign, pictured above, for West Street.

Yes, and - so what? What's so important about West Street? I understand your impatience, but permit me to backtrack a little.

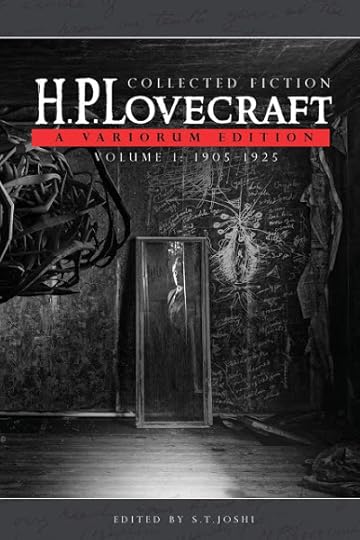

H. P. Lovecraft: Collected Fiction. Ed. S. T. Joshi (3 vols: 2015)

A year or so ago I purchased a copy of the latest, 'variorum' edition of H. P. Lovecraft's Collected Fiction. I've been reading through these very familiar stories of an evening before I go to sleep (which might account for some of the more baroque dreams I've been having lately).

I was interested to encounter, in that classic tale "The Call of Cthulhu," something I must have noticed many times before, a reference not only to New Zealand (the Antipodes figure quite often in Lovecraft's lists of 'eldritch' spaces), but to Auckland itself:

H. P. Lovecraft: The Call of Cthulhu. Illustrated by Dave Shephard (2015)

In Auckland I learned that Johansen had returned with yellow hair turned white after a perfunctory and inconclusive questioning at Sydney, and had thereafter sold his cottage in West Street and sailed with his wife to his old home in Oslo.

- H. P. Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu"

(written 1926; first published in Weird Tales in 1928; plot summary - which I've borrowed from extensively below - available here)

H. P. Lovecraft: The Call of Cthulhu. Illustrated by Jerry Voigt (2019)

But wait. What's this? It turns out that I'm not the only one to see an affinity between Edward Gorey and H. P. Lovecraft (another useful reference is Mike Davis's 2012 article, What if Edward Gorey illustrated Lovecraft?).

Part Three of Lovecraft's "Call of Cthulhu,"entitled "The Madness from the Sea," begins with the narrator, Francis Thurston's chance discovery of:

an article from the Sydney Bulletin, an Australian newspaper, for April 18, 1925, that reported the discovery of a derelict ship in the Pacific Ocean with only one survivor — Norwegian sailor Gustaf Johansen, second mate on the schooner Emma out of Auckland, New Zealand [my emphasis], which on March 22 encountered a heavily armed yacht, the Alert, crewed by "a queer and evil-looking crew of Kanakas and half-castes" from Dunedin, New Zealand. After the Alert attacked without provocation, the crew of the Emma fought back and, though losing their own ship, managed to board the opposing ship and kill all their attackers.Thurston travels to Dunedin:

The article went on to say that the survivors encountered an island the next day, in the vicinity of 47° 9' S, 126° 43' W, even though there are no charted islands in that area. Most of the remaining crew died on the island, but Johansen is said to be "queerly reticent" about what happened to them.

where, however, I found that little was known of the strange cult-members who had lingered in the old sea-taverns. Waterfront scum was far too common for special mention; though there was vague talk about one inland trip these mongrels had made, during which faint drumming and red flame were noted on the distant hillsAfter that he pays a flying visit to Auckland, with the results mentioned above ("Of his stirring experience he [Johansen] would tell his friends no more than he had told the admiralty officials, and all they could do was to give me his Oslo address"). So Thurston's next stop is Sydney, where:

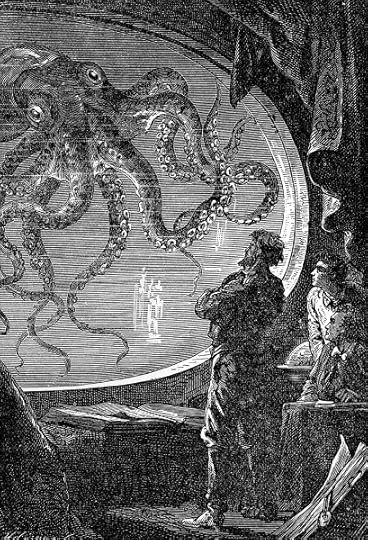

I saw the Alert, now sold and in commercial use, at Circular Quay in Sydney Cove, but gained nothing from its non-committal bulk. The crouching image with its cuttlefish head, dragon body, scaly wings, and hieroglyphed pedestal, was preserved in the Museum at Hyde Park; and I studied it long and well, finding it a thing of balefully exquisite workmanship [...] utter mystery, terrible antiquity, and unearthly strangeness of material[.]Finally, "shaken with such a mental revolution as I had never before known, I now resolved to visit Mate Johansen in Oslo."

and one autumn day landed at the trim wharves in the shadow of the Egeberg. Johansen’s address, I discovered, lay in the Old Town of King Harold Haardrada, which kept alive the name of Oslo during all the centuries that the greater city masqueraded as “Christiana”. I made the brief trip by taxicab, and knocked with palpitant heart at the door of a neat and ancient building with plastered front. A sad-faced woman in black answered my summons, and I was stung with disappointment when she told me in halting English that Gustaf Johansen was no more.Fortunately, Johansen left behind "a long manuscript — of 'technical matters' as he said — written in English, evidently in order to safeguard her from the peril of casual perusal." From this, the narrator learns:

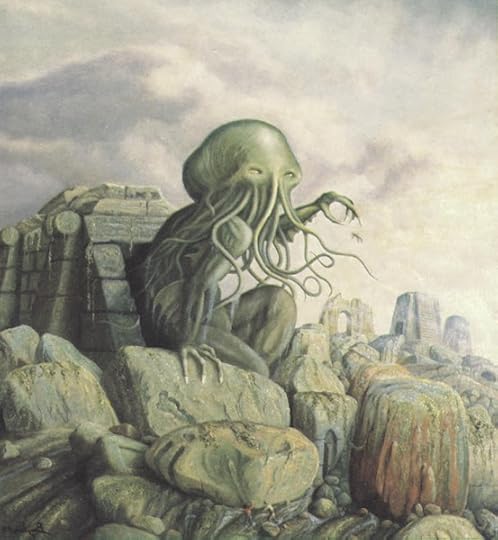

of the crew's discovery of the uncharted island, described as "a coastline of mingled mud, ooze, and weedy Cyclopean masonry which can be nothing less the tangible substance of earth's supreme terror — the nightmare corpse-city of R'lyeh." Exploring the risen land, which is "abnormal, non-Euclidian, and loathsomely redolent of spheres and dimensions apart from ours," the sailors manage to open a "monstrously carven portal," and fromAfter reading this manuscript, Thurston concludes that he will soon meet the fate of Johansen: "I know too much, and the cult still lives." He guesses, however, that Cthulhu, whilst restoring his broken head, was dragged down again with the sinking city, thus keeping humanity safe until the next time, when the stars are right.the newly opened depths [...] It lumbered slobberingly into sight and gropingly squeezed Its gelatinous green immensity through the black doorway [...] The stars were right again, and what an age-old cult had failed to do by design, a band of innocent sailors had done by accident. After vigintillions of years great Cthulhu was loose again, and ravening for delight.Thurston (or Johansen) writes that "The Thing cannot be described," though the story does call it "the green, sticky spawn of the stars," and refers to its "flabby claws" and "awful squid-head with writhing feelers." ... Johansen manages to get back to the yacht; when Cthulhu, hesitantly, enters the water to pursue the ship, Johansen turns the Alert around and rams the creature's head, which bursts with "a slushy nastiness as of a cloven sunfish" — only to immediately begin reforming as Johansen and William Briden (insane, and soon dead) make their escape.

•

West Street, Eden Terrace

There's something rather enchanting in this account of the grand tour, ranging from the Antipodes to Scandinavia, which H. P. Lovecraft was too poverty-stricken ever to undertake in person. The rapturous letters and essays he devoted to visits to more easily attainable beauty spots such as Quebec or Charleston make it clear that nothing would have delighted him more.

Failing this, one imagines him poring over any maps and guidebooks he could locate in Providence, Rhode Island (or even nearby New York) in quest of local colour for his globe-trotting tale.

West Street, Eden Terrace

I have to say that I'd always assumed "West Street" to be a plausible fabrication on his part (what city doesn't include a few streets named after the points of the compass?). I am, after all, a native Aucklander - albeit one born and bred on the North Shore - but I could have sworn that there was no West Street hereabouts.

However, as it turns out, Lovecraft was right.

West Street (7/4/21)

photograph by Bronwyn Lloyd

It may not be now much more than a place to park your car while you go shopping, but before they drove the motorway through, it was clearly a far more extensive boulevard.

Looking down West St., entrance to Galatos St. (c. 1920s)

Here's an old picture taken facing down it, in the general direction of the sea. Lovecraft's story was written (and published) in the mid to late 1920s, and that, too, is the approximate date of this photograph.

Under the circumstances, any search for the possible location of First Mate Gustaf Johansen's cottage seems rather pointless. It probably stood on land long carved out to create Auckland's Spaghetti Junction.

However, in the spirit of the chain of strange coincidences chronicled in Lovecraft's story, I have to say that I was rather struck by some of the graffiti in the parking lot across from West Street, just below the louring presence of St. Benedict's Catholic Church.

Upper Queen Street (7/4/21)

photograph by Bronwyn Lloyd

It's difficult to make out the inscription on the fence. Does it seem to you to read something like CTH[ulhu] SMI[les] [upon you]?

I suppose it's a bit strained of me to see it as an invitation to any potential votaries to join with the other worshippers at the local branch of the Esoteric Order of Dagon, but it does look somewhat suspiciously prominent, up there beside the brick-walled church.

Upper Queen Street Graffiti (7/4/21)

photograph by Bronwyn Lloyd

As for the writing on the parking building, it doesn't really seem to be in any easily recognisable script. It actually looks more like Hebrew than English: Hebrew, or possibly Amharic, or even some South-East-Asian language such as Lao or Thai. It's hard to guess what it might say.

Daniel Stride: H. P. Lovecraft Does Dunedin (2020)

For the rest, although he never came here, H. P. Lovecraft's influence still seems to weigh as heavily on this one section of Central Auckland as does Chicago-born Edward Gorey's over the ghostly mansions of his own adoptive region, New England.

Edward Gorey House (Cape Cod)

•

(1890-1937)

Published on April 11, 2021 13:28

April 4, 2021

Hershel Parker: Archivist Agonistes

Hershel Parker: Melville Biography: An Inside Narrative (2012)

I must have read Hershel Parker's great biography of Herman Melville sometime in 2005. It's hard to be more precise than that, but the details about Melville's unpublished (and now lost) eighth novel I used in my own short story "The Isle of the Cross" certainly came from there.

Tina Shaw & Jack Ross, ed.: Myth of the 21st Century (2006)

That story first saw the light of day in Myth of the 21st Century: An Anthology of New Fiction , co-edited by Tina Shaw and me. That's the only reason I can be so precise.

In those days I used to spend lots of time haunting the stacks in the Auckland Public Library. The extensive collection of graphic novels they kept on the ground floor was always beguiling, but for anything more weighty one generally had to fill in a little card and have it hoisted up from the off-limits basement below.

I don't recall if Parker's two immense volumes were kept down there, but I hope not. They were, after all, only a few years old at that point.

Hershel Parker: Herman Melville: A Biography. Vol. 1, 1819-1851 (1996)

When I mentioned the treasure trove of information in these books to a prominent Melvillean of my acquaintance, I was rather taken aback to receive a belittling reply. A few pages by a real critic, such as Tony Tanner, he informed me, were worth reams of such stupefyingly immersive material.

Hershel Parker: Herman Melville: A Biography. Vol. 2, 1851-1891 (2002)

I suppose that that was my first intimation that all was not well in the flowery fields of Melville biography - or criticism, for that matter. Clearly there were at least two schools of thought on the matter.

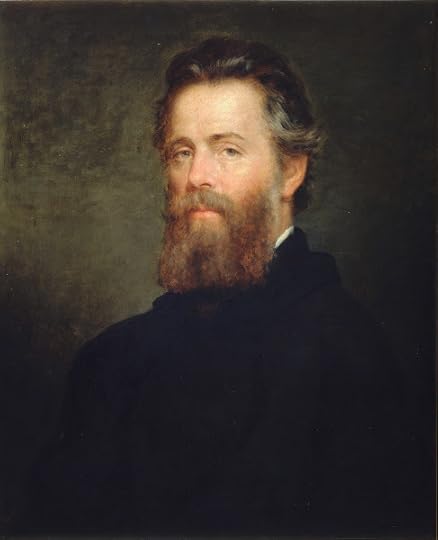

Joseph Oriel Eaton: Herman Melville (1819-1891)

My own rule of thumb (for what it's worth), is always to award the plum to the critic or editor who seems most disposed to provide me with what the great Grady Tripp in Wonder Boys calls my "drug of choice": new printed material.

Biographers International Organisation: Hershel Parker (1935- )

Hershel Parker certainly comes up trumps in that department. As well as his immense biography, he's also largely responsible for a whole series of Melvillean volumes in the Northwestern-Newberry edition of Melville's complete works, the Norton Critical Editions series, and the Library of America (you can see some pictures of the more prominent examples here, if you wish).

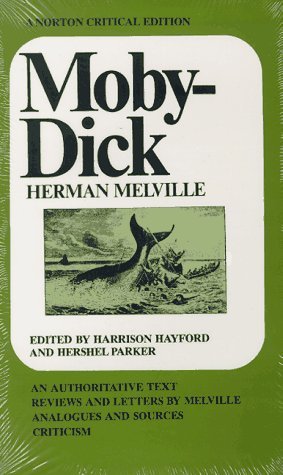

Herman Melville: Moby-Dick. Ed. Harrison Hayford & Hershel Parker (1967/1999)

It will therefore come as no surprise to you that when I first saw his subsequent book Melville Biography: An Inside Narrative advertised online, I felt extremely curious to read it. At that point I'd made a good resolution to try to read more books from libraries instead of buying them as soon as I saw them, so I duly ordered it for the Massey University Library.

Herman Melville: Redburn. Ed. Harrison Hayford, Hershel Parker & G. Thomas Tanselle (1969)

They wouldn't get it for me! The process of listing books and having them acquired for my delectation had worked quite flawlessly up until then. A new policy of denying Academics the books they needed must have come in, however, and I can't recall them buying anything I've asked for from that day to this!

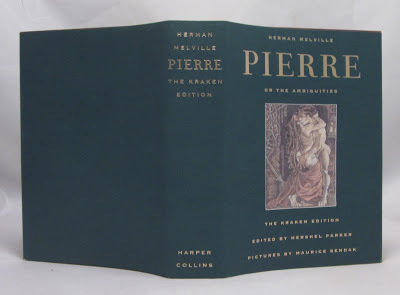

Herman Melville: Pierre: The Kraken Edition. Ed. Hershel Parker (1995)

Anyway, to make a long story short, the other day I cracked and finally ordered all three books from Amazon.com. Their service had been pretty lousy over lockdown, but they seem to be making up for it now: the books were all with me in two shakes of a lamb's tail. Hence the title of this piece. I've finally succeeded in reading Hershel Parker's book, after almost a decade of waiting, and am busting to tell the rest of you all about it.

Herman Melville: Complete Poems. Ed. Hershel Parker (2019)

•

Richard F. Burton (1821-1890)

But first, a slight digression. I've always had a lot of time for cranky, obsessive scholars who go a bit strange from excessive concentration on their subject, and who gradually develop a sense of grievance at the world's indifference to their work - not to mention the rewards lavished on other, lesser researchers in the same field. Who do I have in mind?

Richard F. Burton: The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night (16 vols: 1885-88)

Well, obviously, Sir Richard Francis Burton (you can find more information about him at the link here). On pp. 387-500 of the final volume of his massive translation of the 1001 Nights, he includes a section called 'The Reviewers Review'd.' This is how I described it in an earlier post on this blog:

In one of the six “Supplemental” volumes to his infamous ten-volume translation of the Arabian Nights (1885-88), Richard Burton included a section called “The Reviewers Review’d,” in which he heaped scorn and contumely on various imprudent critics who’d thought to question his command of Arabic. It’s very amusing to read, though occasionally a little unedifying (in another part of the same volume he put in a long essay abusing Oxford’s Bodleian Library, who’d dared to deny him their copy of the famous Wortley-Montague ms. of the Nights – he’d had to employ someone to make primitive photocopies, or “sun pictures,” of it instead. If they had agreed to lend it to him, he crowed, he would have felt honour-bound to suppress some of the more explicit passages, but since he’d had to pay for the pages out of his own pocket, he’d felt at liberty to spell out every last unsavoury detail for the delectation of his readers!)Yes, that's the attitude, all right. No wonder his employers, the British Foreign Office, exiled him to the backwater of Trieste in the (vain) hope of keeping him out of trouble. What is it they called him? "Brilliant but unsound." One would have to admit that he's had the last laugh in the eyes of posterity, though.

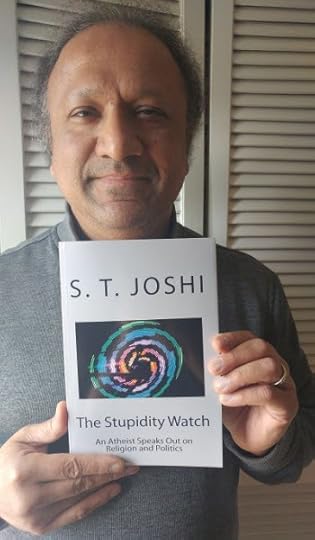

S. T. Joshi: The Stupidity Watch (2017)

My next exhibit is the prodigiously energetic Sunand Tryambak Joshi (1958- ), otherwise known as S. T. Joshi. Like Hershel Parker, he is both editor and biographer, and his work on - in particular - H. P. Lovecraft has definitely revolutionised the field.

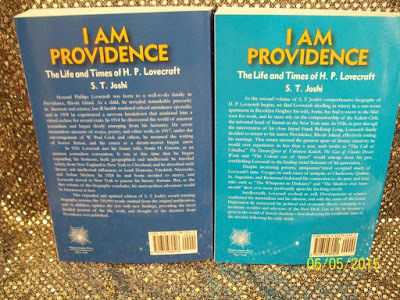

S. T. Joshi: I am Providence: The Life and Times of H. P. Lovecraft (2 vols: 2010-11)

Joshi's self-appointed, life-long task has been to tidy up Lovecraft's literary legacy by re-editing his works (not just the fiction, but the essays and poetry as well), as well as chronicling various other aspects of this activities. This resulted, initially, in the lengthy H. P. Lovecraft: A Life (1996), subsequently re-issued in its even longer original form, in two large volumes, as I am Providence.

Does Lovecraft really deserve all this effort? Well, you're talking to the wrong person, I'm afraid. I accept that his prose is clunky and overblown, his plots predictable, and his racial and cultural attitudes pernicious - but I can't help finding him fascinating even so. The same appears to be true for Joshi, who - as an Asian American - can hardly relish all Lovecraft's diatribes about the 'mongrel races' thronging the Eastern seaboard ...

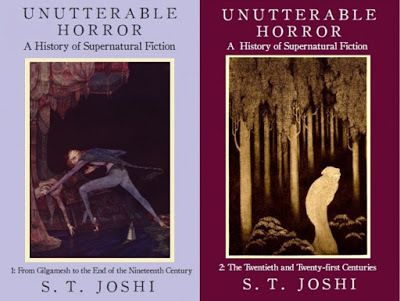

S. T. Joshi: Unutterable Horror: A History of Supernatural Fiction (2 vols: 2014)

Joshi, to do him justice, is pretty omnivorous in his taste for Fantastic literature. He's edited editions of Lord Dunsany, Arthur Machen, and Edward Lucas White, among many, many others. He's also written voluminously on Supernatural Fiction in general.

As the title of his book The Stupidity Watch: An Atheist Speaks Out on Religion and Politics (2017), pictured above, would suggest, however, he's also fairly combative when it comes to any belittling of his views - by other, blander, Lovecraftians, for instance. He, too, then, would have to be seen as a prime example of your textbook "irascible scholar".

•

Alchetron: Hershel Parker (1935- )

All of which brings us, by a commodius vicus of recirculation, back to Hershel Parker, the ostensible subject of this post. Who are his particular enemies?

Well, basically anyone who doubts the value of minute archival research on the lives and texts of famous writers is liable to incur his ire: in other words, New Critics, Structuralists, Deconstructionists, and New Historicists (the latter get an extra caning for frivolously pretending to be real researchers without understanding the true rules of the craft). In essence, he's opposed to most of the major trends in American literary-Academic studies since the end of the Second World War.

And, like Burton and Joshi, one has to admit that he makes a strong case. The famous, oft-quoted example of the critic (F. O. Matthiesson) who made a huge to-do over the metaphysical implications of the phrase "soiled fish of the sea" in Melville's White-Jacket, only to end up up with egg on his face when it turned out that Melville actually wrote "coiled", goes a long way to prove his point.

The fact is that, without reliable texts, such hi-faluting scholarship is pretty much of a waste of time. Hence Parker's fifty-odd years of service as co- and eventually managing editor of the 15-volume Northwestern-Newberry edition of Melville's complete works (1968-2017).

Encyclopedia Virginia: Fredson Bowers (1905-1991)

It isn't quite as simple as that, however. Parker has an additional enemy in the famously irritable (and, according to Parker, not particularly competent) textual authority Fredson Bowers. Parker's monograph - jointly authored with Brian Higgins - denouncing Bower's poor choice of copytext for his edition of Stephen Crane's early novel Maggie: A Girl of the Streets (suppressed when it was first written, in the 1970s, and not finally published until 1995, here, down under, in the The Bulletin of the Bibliographical Society of Australia and New Zealand) constituted his declaration of war:

However purely he began, Bowers became the Mad Scientist of Textual Editing - a Mad Scientist who ran what may have been the world's sloppiest textual lab and promulgated varying self-serving high-sounding textual theories to cover the slovenliness. [29]In particular, the tedious (and largely pointless) lists of hyphenated words and other trivia in editions of American works of literature promulgated by the Bowers-dominated MLA Center for Scholarly Editions occupied time and space which could more profitably allotted to considering more substantive variants, in Parker's opinion.

When experts disagree, it generally behoves the rest of us to stay silent. It certainly is true that obstrusive over-editing is a feature of many of the scholarly editions prduced under the auspices of this organisation.

Edmund Wilson (1895-1972)

But then, that's more or less what Edmund Wilson said, in his late essay "The Fruits of the MLA" (1968). And Wilson - or at any rate his army of followers - is another enemy. One of the principal targets of his essay was the then just published first volume in the Northwestern-Newberry edition of Melville's works:

Wilson acknowledged that there was some minimal significance in the textual and historical scholarship. He was even "prepared to acknowledge the competence of Mr. Harrison Hayford, Mr. Hershel Parker, and Mr. G. Thomas Taselle [sic] in the stultifying task assigned them" ... [However,] Wilson's prestige was such that flatterers leapt to endorse his views without ever studying the CEAA editions for themselves. Even thirty and forty years later younger critics justified themselves to their coteries by huddling behind the corpse of Wilson as they lobbed fuzees underhanded toward scholarly editions and biographies. [42-43]Parker concludes:

The CEAA [Center for Editions of American Authors] had been a nobly conceived enterprise but now it was, in fact, flawed, often deeply flawed. Intelligent, constructive criticism, just then, might have worked some good later on. Wilson and [Lewis] Mumford were so extreme as to be merely destructive. [43]

Andrew Delbanco: Melville: His World and Work (2005)

All of which brings us to Public Enemy No. 1, Andrew Delbanco, author of the above biography of Melville, and a vicious critic - in the reviews pages that matter - of Parker's own biography.

In the chapter 'Agenda-driven Reviewers' [pp.167-93 of his book], Parker documents in immense detail the cabal of New York critics and professors who poured scorn on the plethora of new, archivally gleaned facts in his massive work.

Aside from ingratiating himself with the Wilson-revering New York Review of Books crowd, Delbanco had a pretty clear agenda. He could establish himself as an authority on Melville the easy way, not by doing research on Melville, but by reviewing what I published, then what I published next, and then what I published after that. Thereafter, plundering the Higgins-Parker collection of reviews and my two volumes of the biography, he could emerge with a biography of his own, even if he did not get around to learning some basic episodes in Melville's life until after 2002 ... [182]The collective contempt shown by these ignoramuses for the "gigantic leaf-drifts of petty facts" [177] in Parker's first volume went into overdrive when the second volume appeared in 2002:

In the May 20, 2002, Nation Brenda Wineapple (whose vulgar ignorance of Melville and desecration of the Lamb of God I look at elsewhere in this book) declared that I was as secure in my fantasy biography "as Edmund Morris is in his imaginary Dutch: A Memoir of Ronald Reagan" ... [Richard H.] Brodhead in the June 23, 2002, New York Times implied that I had invented The Isle of the Cross (1853) and Poems (1860) out of thin air ... In the New Republic (September 30, 2002) the look-ma-no-hands biographer-to-be Andrew Delbanco said I couldn't be trusted at all on anything because I had merely surmised the existence of those lost books [188].Needless to say, Parker (pp.295-300) proceeds to produce oceans of documentary evidence for the existence of these two lost books by Melville. More to the point, though, he quotes the following passage from Delbanco's own biography, written a couple of years later:

Andrew Delbanco (2012)

When Hawthorne replied, in effect, thanks but no thanks, Melville decided after all to have a crack at the story himself. The result was a novel-length manuscript, now lost [my emphasis - JR], submitted the following spring to Harpers under the title The Isle of the Cross and promptly rejected, possibly because the Harpers anticipated a legal dispute involving descendants of Agatha and her bigamous husband. [301]In other words, precisely what Parker had been saying all along, and a direct contradiction of Delbanco's earlier sneers at the allegedly "merely surmised" existence of this lost book. "Later," Parker goes on, "Delbanco also belatedly recognized the existence of a collection of poems:"

Exactly when Melville started writing verse is unknown, but by the spring of 1860 he had accumulated enough poems to fill a small manuscript, and while in New York waiting to board the Meteor, he asked his brother Allan to place it with a publisher [301].A very belated acknowledgement by Delbanco of his debt to the "prodigious scholarship" of Hershel Parker, "whose discoveries have immeasurably deepened our knowledge of Melville's life" [303] has done little to placate the latter, especially when it turned out that this phrase was entirely absent from the bound-up proofs of Delbanco's biography, which seem to have somehow fallen into Parker's hands.

Need I go on? Like Caesar's Gaul, Parker's book is divided into three parts: an autobiographical opening, outlining his coming-of-age as a Melville scholar; a long denunciation of modern scholarly ignorance; and, finally, a set of fascinating excursions into particular episodes from Melville's life, designed as a kind of supplement to his biography.

Livid with rage at the effrontery of critics who sneer at a book one day and appropriate its findings the next, he finds it difficult to take his foot off the gas-peddle at times, but it can be justly said that his book is never dull. And while his opponents may be more typically sold-out products of the Academic machine than he acknowledges, preferring to type them as fiends incarnate, there seems little doubt that Delbanco and co. did do considerable damage to his scholarly reputation.

Some of his most extreme vitriol is reserved for a comparative bystander, however, the Hawthorne-biographer Brenda Wineapple, whose comparison of Parker's biography with Edmund Morris's notoriously fraudulent Dutch: A Memoir of Ronald Reagan I quoted above:

Brenda Wineapple

In her review of the second volume of Parker's biography, Wineapple cast back in time to throw doubt on the veracity of the November 1851 meeting between Melville and Hawthorne which served as the culmination of the first volume. A year later, however, in her own biography of Hawthorne, this "fantasy" meeting appears to have become an historical fact:

Early in November, Hawthorne met Melville for dinner at the Lenox hotel, and that night Melville presumably gave Hawthorne his inscribed copy of Moby-Dick, cooked, Melville hinted, partly at Hawthorne's fire. "I have written a wicked book," Melville was to tell him, "and feel spotless as a lamb." [423]"Dirty pool, old man, dirty pool!" as Gomez Addams was wont to say. Wineapple can't really have it both ways. Either it was a fantasy, a complete fabrication from a scholarly fraud, or it was a real meeting, abundantly documented by the kinds of sources Parker has made a speciality of delving into.

Brenda Wineapple: Hawthorne: A Life (2003)

Whether Wineapple really merits this much attention is beside the point. She has sinned against the basic tenets of scholarly integrity, sneering in print at a purveyor of facts which she subsequently relied on herself. Parker's denunciations of her "cheeky, vulgar writing" might go a bit far, but he is certainly right to point out that she fundamentally misconstrues the meaning of Melville's "lamb" remark:

Wineapple misquoted what Melville wrote Hawthorne three days or so later, his claiming to "feel spotless as the [not a] lamb." We are dependent on Rose Hawthorne Lathrop's transcription, but this daughter of Hawthorne's knew a biblical reference when she saw one. Melville felt then ... - anyone who knows the Bible or falteringly consults a biblical concordance would have recognized - as spotless as Jesus, the Lamb of God. [424]

The Great Bible (1539)

As an ex-fundamentalist Christian myself, I must confess it hadn't occurred to me that anyone could miss so obvious a reference, but of course the Bible is no longer obsessively studied by most of the population nowadays. It's not that I think it necessarily should be, but anyone hoping to make a profession of literary criticism had better try to acquire a familiarity with it.

There's scarcely an author in English who doesn't constantly drop in phrases from it from the mid-sixteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries, a span of approximately five hundred years. And I'm afraid it never really occurred to most of them (including Melville) that these allusions wouldn't be recognised as such.

The Bible: Authorised Version (1611)

So, would I recommend that you rush out and buy a copy of Melville Biography: An Inside Narrative, then? Not really - not unless you're a literary biographer or a critic of same. It certainly has an eccentric charm as a book, but one can only salute Parker's wisdom in confining most of this stuff to a single, stand-alone monograph.

His biography will continue to be the one indispensible work on the subject of Melville in English for the foreseeable future, and I guess all his fans continue to await the eventual appearance of his revised edition of Jay Leyda's classic Melville Log.

Parker certainly needed to get all these corrections of fact and emphasis off his chest, but - as is the case with Burton and Joshi (though I doubt the former would relish the comparison) - their true monument remains the splendid works they've managed to usher into the light of day for the rest of us.

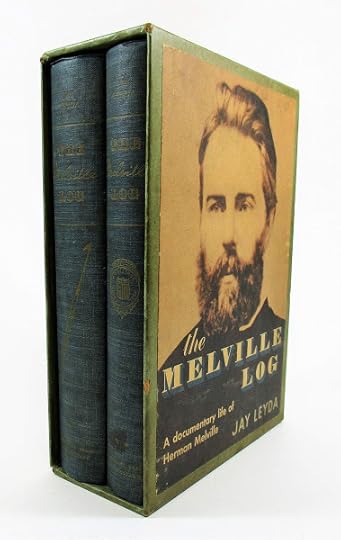

Jay Leyda: The Melville Log (1951)

•

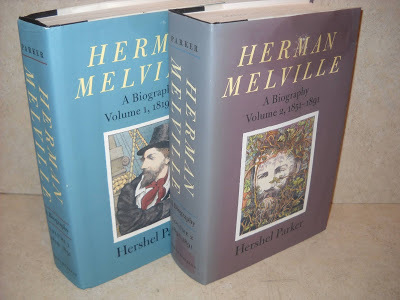

Hershel Parker: Herman Melville: A Biography (2 vols: 1996 & 2002)

Hershel Parker (1935- ):

His Books in my Collection

As Author:

Herman Melville: A Biography. Volume 1, 1819-1851. Baltimore & London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

Herman Melville: A Biography. Volume 2, 1851-1891. Baltimore & London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002.

Melville Biography: An Inside Narrative. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 2012.

As Editor:

Herman Melville. Mardi, and A Voyage Thither. 1849. Ed. Harrison Hayford, Hershel Parker & G. Thomas Tanselle. The Writings of Herman Melville: the Northwestern–Newberry Edition, vol. 3. Evanston & Chicago: Northwestern University Press & The Newberry Library, 1970.

[with Harrison Hayford]. Moby-Dick as Doubloon: Essays and Extracts (1851-1970). A Norton Critical Edition. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1970.

Herman Melville. The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade. An Authoritative Text / Backgrounds and Sources / Reviews / Criticism / An Annotated Bibliography. 1857. Ed. Hershel Parker. A Norton Critical Edition. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1971.

Herman Melville. Clarel: A Poem and Pilgrimage in the Holy Land. 1876. Ed. Harrison Hayford, Alma A. MacDougall, Hershel Parker & G. Thomas Tanselle. The Writings of Herman Melville: the Northwestern–Newberry Edition, vol. 12. Evanston & Chicago: Northwestern University Press & The Newberry Library, 1991.

Herman Melville. Pierre, or The Ambiguities: The Kraken Edition. 1852. Ed. Hershel Parker. Pictures by Maurice Sendak. New York: HarperCollins, 1995.

Herman Melville. Published Poems: Battle Pieces; John Marr; Timoleon. 1866, 1888 & 1891. Ed. Robert C. Ryan, Harrison Hayford, Alma MacDougall Reising & G. Thomas Tanselle. Historical Note by Hershel Parker. The Writings of Herman Melville: the Northwestern–Newberry Edition, vol. 11. Evanston & Chicago: Northwestern University Press & The Newberry Library, 2009.

Herman Melville. Billy Budd, Sailor and Other Uncompleted Writings: Billy Budd, Sailor; Weeds and Wildlings; Parthenope; Uncollected Prose; Uncollected Poetry. Ed. Harrison Hayford, Alma A. MacDougall, Robert A. Sandberg & G. Thomas Tanselle. Historical Note by Hershel Parker. The Writings of Herman Melville: the Northwestern–Newberry Edition, vol. 13. Evanston & Chicago: Northwestern University Press & The Newberry Library, 2017.

Herman Melville. Complete Poems: Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War / Clarel: A Poem and Pilgrimage in the Holy Land / John Marr and Other Sailors with Some Sea-Pieces / Timoleon Etc. / Posthumous & Unpublished: Weeds and Wildlings Chiefly, with a Rose or Two / Parthenope / Uncollected Poetry and Prose-and-Verse. 1866, 1876, 1888 & 1891. Library of America Herman Melville Edition, 4. Ed. Hershel Parker. Note on the Texts by Robert A. Sandberg. The Library of America, 320. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 2019.

•

Alchetron: Hershel Parker & friend

Published on April 04, 2021 15:24

March 19, 2021

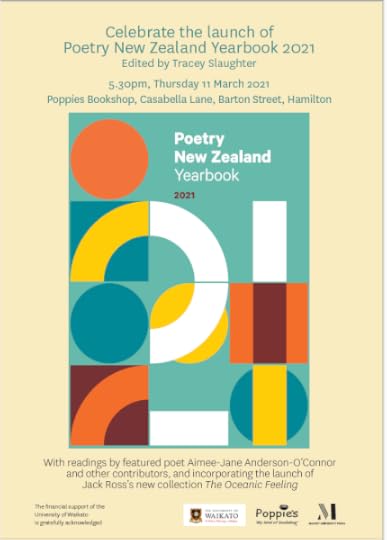

The Oceanic Feeling - Pictures from a Booklaunch

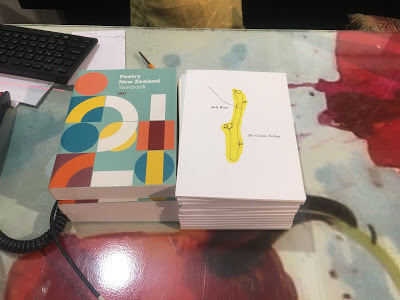

Cover image: Katharina Jaeger / Cover design: William Bardebes (2020)

[All Photographs by William Bardebes (11/3/21)]

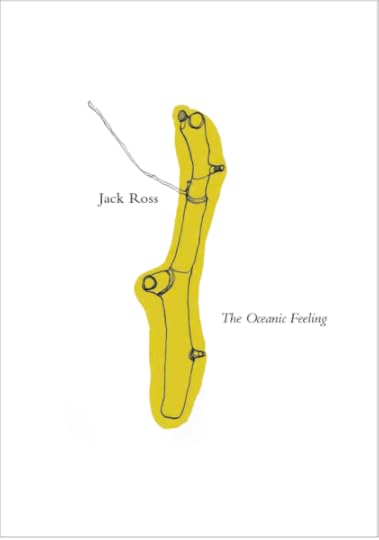

The Oceanic Feeling . Drawings by Katharina Jaeger. Afterword by Bronwyn Lloyd.

ISBN 978-0-473-55801-7. Auckland: Salt & Greyboy Press, 2021. 72 pp.

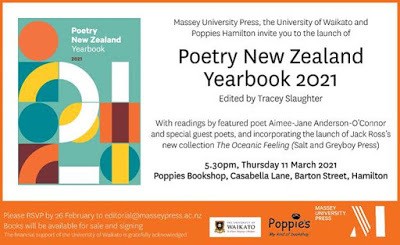

So Bronwyn and I drove down to Hamilton last Thursday with our good friend Liz Morton for the dual launch of Poetry New Zealand Yearbook 2021 and my own new poetry book The Oceanic Feeling .

Poppies Bookshop Hamilton

[l-to-r: Mark Houlahan, Aimee-Jane Anderson-O'Connor, Alison Southby, Bronwyn Lloyd, Janet Charman]

Luckily my publishers at Salt & Greyboy Press, William Bardebes and Emma Smith, were able to come down as well - and the former got a number of pictures of the event.

Tracey Slaughter launching the book

& me reading from it

So what is this "Oceanic Feeling," anyway?

J. M. Masson: The Oceanic Feeling (1980)

Here's a book on the subject by Sanskritist and animal-expert Jeffrey Masson. To quote my own abstract (alas, those of us in Academia do have to compose such statements when claiming such works as 'creative research'):

In a 1927 letter to Sigmund Freud, French writer Romain Rolland coined the term "the oceanic feeling" as a way of referring to that "sensation of ‘eternity’," of "being one with the external world as a whole," which underlies all religious belief (but does not necessarily depend on it). In his reply, Freud described this as a simple characterisation of the feeling an infant has before it learns there are any other people in the world.Of course, those of us who live in Oceania, may have our own alternative interpretations of the phrase. This, at any rate, is mine.

Huge, heartfelt thanks, then, to everyone who worked so hard to make this event a success: Tracey Slaughter, for her luminous launch speech (and for inviting me along in the first place); Katharina Jaeger, for the use of her beautiful images in the book; Bronwyn Lloyd, for her afterword, not to mention her imperturbability in the midst of crisis; William Bardebes, for his amazing book design, as well as for rushing the copies down-country in time for the launch; Alison Southby for offering to sell it at her delightful bookshop Poppies Hamilton; and (of course) to all those who turned up on the day for the Yearbook launch, and kindly stayed on for this part of the event.

•

•

Published on March 19, 2021 14:10

March 13, 2021

Classic Ghost Story Writers: Margaret Irwin

Lafayette: Margaret Irwin (1928)

I suppose that this one is a bit of a stretch. While two of the finest ghost stories I've ever read - "The Book" and "The Earlier Service" - were written by Margaret Irwin, there's no denying that her real fame stems (not unreasonably) from her work as an historical novelist.

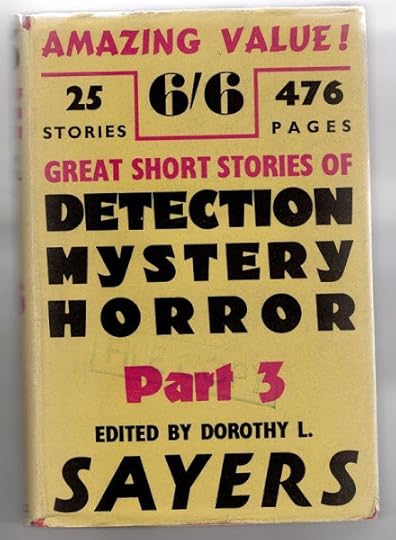

Dorothy Sayers, ed.: Great Short Stories of Detection, Mystery, and Horror (3 vols: 1928-34)

I first encountered these two stories in the multi-volume anthology above. As for her novels, I collected those gradually from various secondhand bookshops.

The four set in the seventeenth century, around about the time of what we used to refer to as the English Civil War (and would now have to call the British Wars), are probably my favourites. I've read each of them a number of times, and they've been a great help to me in disentangling many of the political complexities of the era.

They are, in order of publication (though not chronology):

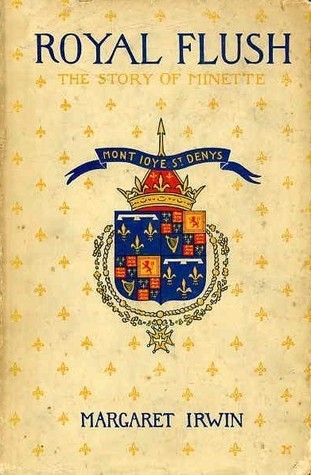

Margaret Irwin: Royal Flush (1932)

Royal Flush: The Story of Minette. 1932. London: Chatto & Windus, 1947.The Proud Servant: The Story of Montrose. 1934. London: Pan Books, Ltd., 1966.The Stranger Prince: The Story of Rupert of the Rhine. 1937. London: Chatto & Windus, 1947.The Bride: The Story of Louise and Montrose. London: Chatto & Windus, 1939.

Margaret Irwin: The Proud Servant (1934)

The best of these, I suppose, is The Proud Servant - about that super-romantic figure the Marquis of Montrose, and his one-man war against the Covenanters in Scotland. But all of them are interesting. In particular, the portrait given of the Dutch household of the 'Winter Queen,' the exiled Queen of Bohemia, daughter of the British monarch James 1st and mother of Prince Rupert, in both The Stranger Prince and The Bride, retains a certain fascination.

Margaret Irwin: The Stranger Prince (1937)

She followed up these triumphs with another group of novels set in the sixteenth century: one rather disappointing one about Mary Queen of Scots, followed by a brilliant trilogy about Queen Elizabeth the First:

Margaret Irwin: The Gay Galliard (1941)

The Gay Galliard: The Love Story of Mary Queen of Scots. London: Chatto & Windus, 1941.The Queen Elizabeth Trilogy:Young Bess. 1944. Grey Arrow. London: Arrow Books, Ltd., 1960.Elizabeth, Captive Princess. 1948. London: The Reprint Society, 1950.Elizabeth and the Prince of Spain. London: Chatto & Windus, 1953.

George Sidney, dir.: Young Bess (1953)

The most famous of these is undoubtedly Young Bess. It was even used as the basis of a film starring Jean Simmons and Deborah Kerr (not to mention Charles Laughton as Henry the Eighth!).

Besides that, there are a number of other novels. She started off in the fantasy genre, in the gentler, pre-Tolkien, early twentieth century mode of Stella Benson and Robin Hyde:

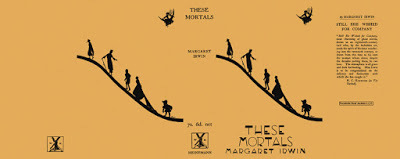

Margaret Irwin: Still She Wished for Company (1924)

Still She Wished for Company. 1924. A Peacock Book. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1979.These Mortals. 1925. Uniform Edition. 1952. London: Chatto & Windus, 1968.Knock Four Times. 1927. Uniform Edition. London: Chatto & Windus, 1951.Fire Down Below. London: Chatto & Windus, 1928.None So Pretty. 1930. London: Chatto & Windus, 1935.

Margaret Irwin: None So Pretty (1930)

Still She Wished for Company is an intricately told ghost story, and None So Pretty a tautly written period piece. Both show her already developing the skills which would lead to her mature historical novels a few years later.

The middle three are rather twee fantasy novels, which don't quite work for me, but which were certainly very popular at the time - hence the need for a 'uniform edition' of her works in the 1950s. I should note, though, that Rob Maslen mounts a spirited defence of These Mortals in the third of three posts about "Margaret Irwin between the wars" on his City of Lost Books blog.

A number of the online bibliographies for Irwin list another couple of late novels which I can't find available for sale anywhere, on Amazon or elsewhere, and whose existence I've therefore begun to doubt.

The Heart's Memory (1951)Hidden Splendour (1952)

The fact that those same bibliographies (on Wikipedia, the Fiction Database, Fantastic Fiction and Agora Books) significantly misdate a number of her books, and - what's more - repeat the same errors from list to list, suggests to me that they're based on a comparison with each other, rather than independent library research.

The dates in my own listings are based on my own copies of each of the books in question (with the exception of Fire Down Below and her two, fabulously rare, early volumes of short stories, Madame Fears the Dark and Mrs. Oliver Cromwell, all of which I'm still searching for).

Margaret Irwin: That Great Lucifer (1960)

Irwin also published one work of non-fiction - a spirited biography of Sir Walter Ralegh.

[NB: The Featherstones and Halls: Gleanings from Old Family Matters, Letters and Manuscripts (1890, reprinted 2018), is not hers, though it's listed under her name in several bibliographies]My main interest here, however, is in her short stories. Here are her three collections (with the stories I don't have access to marked in italics):

Margaret Irwin: Madame Fears the Dark (1935)

Madame Fears the Dark: Seven Stories and a Play. London: Chatto & Windus, 1935:

The BookMr CorkThe Earlier ServiceMadame Fears the DarkMonsieur Seeks a WifeTime Will TellThe Curate and the Rake"Where Beauty Lies"

Margaret Irwin: Mrs. Oliver Cromwell (1940)

Mrs. Oliver Cromwell and Other Stories . London: Chatto & Windus, 1940:

CourageBreaking-PointThe DoctorMayflyMrs. Oliver CromwellThe Country GentlemanBloodstock'I See You'The CollarThe Cocktail Bar

Margaret Irwin: Bloodstock (1953)

Bloodstock and Other Stories . 1935 & 1940. Uniform Edition. London: Chatto & Windus, 1953:

Stories from Ireland CourageThe Country GentlemanThe DoctorBloodstockThe Collar Uncanny Stories The BookMonsieur Seeks a WifeMistletoeThe Earlier Service Mrs. Oliver Cromwell and Where Beauty Lies Mrs. Oliver CromwellWhere Beauty Lies

So, after all that preamble, what are the two ghost stories I mentioned above actually about? [Warning: plot spoilers ahead ...]

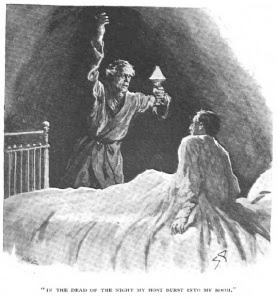

Margaret Irwin: The Book (1930)

The first one, "The Book," is concerned with that favourite theme of the ghost story writer, the haunted book. In this case the early, sound financial advice given by the book to the hapless Mr. Corbett becomes rapidly more sinister as he becomes more and more dependent upon it.

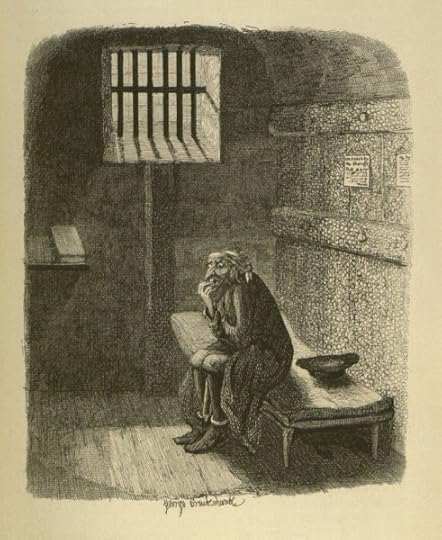

I guess what's really stuck in my mind about this story are the 'tainted' literary opinions - presumably conveyed by the book itself - which gradually poison his favourite authors for Corbett. Having taken out The Old Curiosity Shop and Marius the Epicurean from his shelves for some late night reading, since "Reading was the best thing to calm the nerves, and Dickens a pleasant, wholesome and robust author."

Tonight, however, Dickens struck him in a different light. Beneath the author's sentimental pity for the weak and helpless, he sensed a revolting pleasure in cruelty and suffering, while the grotesque figures of the people in Cruikshank's illustrations revealed too clearly the hideous distortions of their souls.

George Cruikshank: Illustration for Oliver Twist (1838)

"What had seemed humorous now appeared diabolic, and in disgust at these two old favourites, he turned to Walter Pater for the repose and dignity of a classic spirit."

But presently he wondered if this spirit was not in itself of a marble quality, frigid and lifeless, contrary to the purpose of nature. "I have often thought," he said to himself, "that there is something evil in the austere worship of beauty for its own sake.” He had never thought so before, but he liked to think that this impulse of fancy was the result of mature consideration, and with this satisfaction he composed himself for sleep.However, his sleep is plagued with dreams "of these blameless Victorian works."

Sprightly devils in whiskers and peg-top trouses tortured a lovely maiden and leered in delight at her anguish; the gods and heroes of classic fable acted deeds whose naked crime and shame Mr. Corbett had never appreciated in Latin and Greek Unseens. When he had woken in a cold sweat from the spectacle of the ravished Philomel’s torn and bleeding tongue, he decided there was nothing for it but to go down and get another book that would turn his thoughts in some more pleasant direction.He can't quite nerve himself up to do so, though. Instead, in the days that follow, he finds that, like his children, who have started to detect cruelty and cynicism in such works as Thackeray's The Rose and the Ring, and even an expurgated Boy's Gulliver's Travels, he is "off reading":

Authors must all be filthy-minded; they probably wrote what they dared not express in their lives. Stevenson had said that literature was a morbid secretion; he read Stevenson again to discover his particular morbidity, and detected in his essays a self-pity masquerading as courage, and in Treasure Island an invalid's sickly attraction to brutality."This gave him a zest to find out what he disliked so much, and ... he explored with relish the hidden infirmities of minds that had been valued by fools as great and noble."

He saw Jane Austen and Charlotte Brontë as two unpleasant examples of spinsterhood; the one as a prying, sub-acid busybody in everyone else's flirtations, the other as a raving, craving maenad seeking self-immolation on the altar of her frustrated passions. He compared Wordsworth's love of nature to the monstrous egotism of an ancient bell-wether, isolated from the flock.Well might Mr. Corbett conclude that "with a mind so acute and original he should have achieved greatness".

The interesting thing about these opinions is that they are extremely cogent. Commentators on the story find it difficult to explain just why we should reject these "jejune" or "prematurely cynical" conclusions on their own merits, and are forced to fall back on the fact that - in the context of the story, at least - they are portrayed as the emanations of a deceiving, unholy spirit.

That description of Wordsworth, in particular, is worthy of an F. R. Leavis or a Leslie Fiedler - but the "possessed" Corbett is pretty close to the mark on Dickens and Stevenson, also. Or so a Bloomsbury-inspired critic might well have thought. The date of the story, 1930, was, after all, the heyday of Lytton Strachey's influence.

J. C. Squire (1884-1958)

The London Mercury, where the story first appeared, was a notoriously reactionary literary monthly edited by the anti-modernist, "wholesome and hearty" J. C. Squire. The true cunning of "The Book," then, is to smuggle in such opinions in the guise of satire, leaving them to germinate secretly in unsuspecting readers.

Margaret Irwin's story is a masterpiece. It continues to provoke and nag at us to this day. Whether she shared any of these against-the-grain opinions of canonical British authors is impossible to say. Certainly she was capable of formulating them, which is proof that they must have existed somewhere within her.

She hasn't stopped me reading (and enjoying) any of the five authors she skewers - or, rather, whom her character challenges under the influence of an evil monk-turned-book - but she has made me think harder about each of them. The bleatings of Wordsworth, turned from love of the French Revolution to fulsome praise of his worthless patron Lord Lonsdale - the hypocritical sympathy of Dickens for oppressed young ladies while living under an assumed name with the powerless young Ellen Ternan - the gloating tone of Stevenson as he describes deaths and summary executions in The Black Arrow - the sheer weirdness of Charlotte Brontë's universe - the glaring omissions in Jane Austen's - all of these lend some weight to the insidious power of the story and of its ideas.

Who can say what it's really about? It enters the ranks of supernatural classics because it continues to tease and irritate us, like the very finest of the works of Poe or Hoffmann.

Margaret Irwin: The Earlier Service (1935)

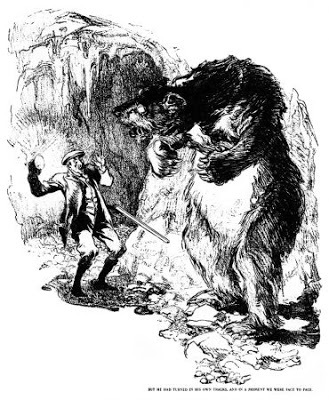

The second of the two, "The Earlier Service," transfers the basic conceit of Nathaniel Hawthorne's "Young Goodman Brown" - a witch cult concealed under a facade of piety - to an English country church, with a time-shift element built in for good measure.

The extra turn of the screw this time comes from the presence of a crusader tomb in the church, which gives comfort to Jane, the young girl at the centre of the plot, as she finds herself increasingly drawn under the influence of these sinister past events. She finds herself repeatedly reciting - or rather, misquoting - Coleridge's lines:

The knight is dust.The young man York, an enthusiastic antiquarian, and the only one who takes her premonitions seriously, eventually unearths the reason for this shadowy presence hovering over the parish:

His good sword rust.

His soul is with the saints we trust.

In the reports of certain trials for sorcery in the year 1474, one Giraldus atte Welle, priest of the parish of Cloud Martin in Somerset, confessed under torture to having held the Black Mass in his church at midnight on the very altar where he administered the Blessed Sacrament on Sundays. This was generally done on Wednesday or Thursday, the chief days of the Witches’ Sabbath when they happened to fall on the night of the full moon. The priest would then enter the church by the little side door, and from the darkness in the body of the church those villagers who had followed his example and sworn themselves to Satan, would come up and join him, one by one, hooded and masked, that none might recognize the other. He was charged with having secretly decoyed young children in order to kill them on the altar as a sacrifice to Satan, and he was finally charged with attempting to murder a young virgin for that purpose.Jane, it seems, has been chosen to fill in for the young virgin, since Giraldus never succeeded in completing his ritual:

All the accused made free confessions towards the end of their trial, especially in as far as they implicated other people. All however were agreed on a certain strange incident. That just as the priest was about to cut the throat of the girl on the altar, the tomb of the Crusader opened, and the knight who had lain there for two centuries arose and came upon them with drawn sword, so that they scattered and fled through the church, leaving the girl unharmed on the altar.York is too late to prevent Jane's abduction by the hungry ghosts.

He walked up to the little gate into the churchyard. There was a faint light from the chancel windows, and he thought he heard voices chanting. He paused to listen, and then he was certain of it, for he could hear the silence when they stopped. It might have been a minute or five minutes later that he heard the most terrible shriek he had ever imagined, though faint, coming as it did from the closed church; and knew it for Jane’s voice. He ran up to the little door and heard that scream again and again. As he broke through the door he heard it cry “Crusader! Crusader!” The church was in utter darkness, there was no light in the chancel, he had to fumble in his pockets for his electric torch. The screams had stopped and the whole place was silent. He flashed his torch right and left, and saw a figure lying huddled against the altar. He knew that it was Jane; in an instant he had reached her. Her eyes were open, looking at him, but they did not know him, and she did not seem to understand him when he spoke. In a strange, rough accent of broad Somerset that he could scarcely distinguish, she said, “It was my body on the altar.”I guess one reason I like this story so much is the careful detailing of the backdrop - the shy attraction of Jane to York, and his own growing fascination with this intelligent but troubled young girl.

But I do have to admit that I also like that moment of what Tolkien would call Eucatastrophe (the opposite of catastrophe: the sudden lucky turn that saves everything) when the Crusader comes to life and hunts the devil worshippers from the church.

So much did I like it that I wrote a long poem about it when I was in my teens (now, luckily, long burnt to ashes). It completely failed to reproduce the atmosphere of Irwin's story. That may have been the first moment when I really started to understand how much skill and careful artifice went into the creation of such effects.

I don't have much to say about the rest of Irwin's short stories. Some of them are quite good of their kind, such as the one about Cromwell's nominee attempting to take over his new estate in Ireland, but none of them rise to the heights of the two discussed above. Irwin clearly had a fascination with the supernatural, but it was the deep romanticism of her nature which brought the historical novels so vividly to life.

J. R. R. Tolkien: Moments of Eucatastrophe (The Return of the King: 1955)

•

Bassano Ltd.: Margaret Irwin (1939)

Margaret Emma Faith Irwin

(1889–1967)

Novels:

Still She Wished for Company. 1924. A Peacock Book. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1979.These Mortals. 1925. Uniform Edition. 1952. London: Chatto & Windus, 1968.Knock Four Times. 1927. Uniform Edition. London: Chatto & Windus, 1951.Fire Down Below. London: Chatto & Windus, 1928.None So Pretty. 1930. London: Chatto & Windus, 1935.Royal Flush: The Story of Minette. 1932. London: Chatto & Windus, 1947.The Proud Servant: The Story of Montrose. 1934. London: Pan Books, Ltd., 1966.The Stranger Prince: The Story of Rupert of the Rhine. 1937. London: Chatto & Windus, 1947.The Bride: The Story of Louise and Montrose. London: Chatto & Windus, 1939.The Gay Galliard: The Love Story of Mary Queen of Scots. London: Chatto & Windus, 1941.The Queen Elizabeth Trilogy:Young Bess. 1944. Grey Arrow. London: Arrow Books, Ltd., 1960.Elizabeth, Captive Princess. 1948. London: The Reprint Society, 1950.Elizabeth and the Prince of Spain. London: Chatto & Windus, 1953.The Heart's Memory (1951) [?]Hidden Splendour (1952) [?]

Short stories:

Madame Fears the Dark: Seven Stories and a Play. London: Chatto & Windus, 1935.Mrs. Oliver Cromwell and Other Stories. London: Chatto & Windus, 1940.Bloodstock and Other Stories. 1935 & 1940. Uniform Edition. London: Chatto & Windus, 1953.

Biography:

That Great Lucifer: A Portrait of Sir Walter Ralegh. 1960. London: The Reprint Society, 1961.

Margaret Irwin: These Mortals (1925)

Published on March 13, 2021 13:25

March 8, 2021

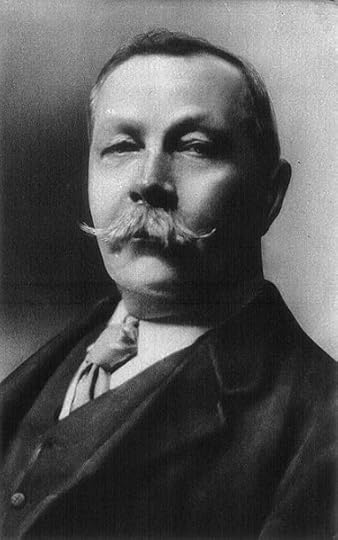

Classic Ghost Story Writers: Arthur Conan Doyle

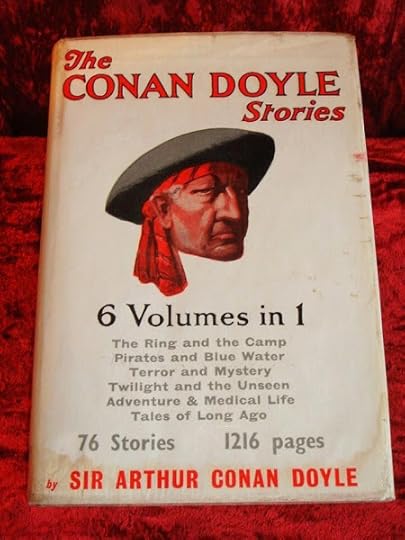

The Conan Doyle Stories (1929)

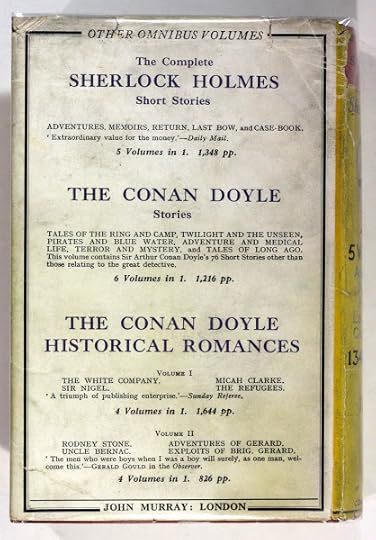

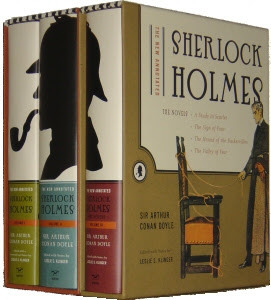

Towards the end of his life, the vogue of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) was still such that it made good commercial sense to collect his works in convenient omnibus form. First of all (of course) came Sherlock Holmes, with one volume (1928) for the five volumes of short stories and another (1929) for the four novels.

Next came the collected short stories (1929), then two volumes of 'historical romances' (1931 & 1932). Long after that, in the 1950s, came the Professor Challenger stories (The Lost World and its successors) and even an omnibus of Napoleonic Stories (though the latter overlaps considerably with the second volume of historical romances) - seven books in all, then, containing 16 novels and at least 11 volumes of short stories.

Arthur Conan Doyle: The Sherlock Holmes Short Stories (1928)

Sherlock Holmes was a rationalist, concerned only with what could be scientifically proven and deduced from the evidence. His creator was anything but. I've written elsewhere (here and here) about Charles Sturridge's wonderful film Fairy Tale (1997), which retells the strange story of the Cottingley Fairies.

Peter O'Toole as Conan Doyle (1997)

Peter O'Toole does an excellent job of impersonating the distinctly credulous but still (paradoxically) occasionally astute Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. It becomes clear in the course of the action that it was the loss of his son Kingsley in the First World War - he died of influenza caught at the front two weeks before the armistice - that compels Doyle to continue his quest for communication beyond the veil.

This monstrous pall of loss hanging over the whole western world does explain, to some extent, the post-war growth of interest in spiritualism. The hitherto widely respected physicist Sir Oliver Lodge's book Raymond, or Life and Death (1916), about the séances he held to contact his own dead son, had an immense influence over other grieving parents, and Doyle gradually became their spokesman and standard-bearer.

Arthur Conan Doyle: The Land of Mist (1925-26)

Even the hard-headed Professor Challenger, the dinosaur hunter of The Lost World (1912), was pressed into service as a psychic investigator in Doyle's late novel The Land of Mist (1926). Sherlock Holmes must be said to have had a narrow escape in not being conscripted similarly - even in The Hound of Baskervilles, where all the spectral appearances turn out to have a distinctly rational explanation.

Arthur Conan Doyle: "The Story of the Brown Hand" (1899)

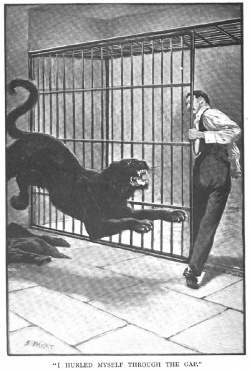

It's not really those stories I want to discuss here, though. It's the ones collected in those two sections of The Conan Doyle Stories entitled "Tales of Terror & Mystery" and "Tales of Twilight & the Unseen." These include such frequently anthologised classics as "The Brown Hand" and "The Brazilian Cat."

Arthur Conan Doyle: "The Story of the Brazilian Cat" (1898)

A great many of the others are equally memorable, though. For the most part they predate the period of his full-fledged involvement with Spiritualism, but it was already plain that he already had a strong affinity with the supernatural and mystical. Two stories that made a particular impression on me when I first read them as a boy were "The Terror of Blue John Gap" and "The Leather Funnel."

Arthur Conan Doyle: "The Terror of Blue John Gap" (1910)

The first of these is somewhat reminiscent of H. P. Lovecraft's early story "The Beast in the Cave," written in 1904 (though not published until 1918). The fourteen-year-old Lovecraft could certainly not yet match the storytelling prowess of the immensely experienced Conan Doyle, but a comparison of the stories does offer some interesting reflections on what two different writers can do with not dissimilar material.

Arthur Conan Doyle: "The Leather Funnel" (1902)

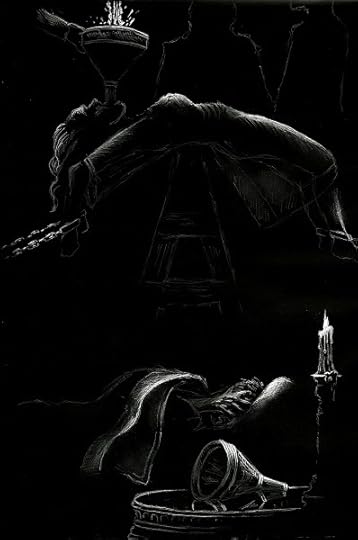

"The Leather Funnel," by contrast, with its interest in psychometry and the sadistic excesses of the Inquisition, has an atmosphere of sadistic sexuality quite alien to Lovecraft but clearly quite attractive to Doyle.

[NB: It's worth stressing here the availability of these and other works by Doyle on the wonderfully comprehensive Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia website. You can find there both the texts and contemporary illustrations for all of the stories mentioned in this post.]

Arthur Conan Doyle: "Lot No. 249" (1892)

What else? There's a wonderfully vivid Egyptian-mummy-coming-to-life story in "Lot No. 249" - which predates by a decade Bram Stoker's classic (1903). Nor did Doyle avoid conventional 'occultism' in his earlier stories. There's also a striking account of a séance going terribly wrong in "Playing with Fire," and a nice piece of automatic writing in "How It Happened" (1913).

Sidney Paget: "Illustration for "Playing with Fire" (1900)

Need I go on? Doyle is, I think, at his best as a ghost story writer when he can combine aspects of his fascination with historical detail with nasty doings in the present. This is certainly the case in "The Leather Funnel," and also in "The New Catacomb" (1898), a neat variation on Poe's "Cask of Amontillado."

Not all of his work in this genre is included in the 1200 pages of The Conan Doyle Stories, however. A useful round-up of his unknown and uncollected pieces is provided by the late Richard Lancelyn Green's excellent The Unknown Conan Doyle: Uncollected Stories.

Uncollected Stories. Ed. John Michael Gibson & Richard Lancelyn Green (1982)

If it's Doyle's occultism that really interests you, though, you could do worse than try to find the recent (2013) Hesperus Press volume On the Unexplained, a selection from his late collection The Edge of the Unknown.

Arthur Conan Doyle: The Edge of the Unknown (1930)

•

Arthur Conan Doyle (1914)

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle

(1859-1930)

Fiction:

The Complete Sherlock Holmes Long Stories. 1929. London: John Murray, 1949.A Study in Scarlet (1887)The Sign of the Four (1890)The Hound of the Baskervilles (1902)The Valley of Fear (1915)

The Conan Doyle Historical Romances. Volume 1 of 2. London: John Murray, 1931.Micah Clarke (1889)The White Company (1891)The Refugees (1893)Sir Nigel (1906)

The Mystery of Cloomber (1889)

The Firm of Girdlestone (1890)

Mysteries and Adventures (1890) [short stories]

The Captain of the Polestar and Other Tales. 1890. London & New York: Longmans, Green & Co., 1893. [short stories]

The Doings of Raffles Haw (1891)

The Complete Sherlock Holmes Short Stories. 1928. London: John Murray, 1949.The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1892)The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (1894)The Return of Sherlock Holmes (1905)His Last Bow (1917)The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes (1927)

The Complete Napoleonic Stories. London: John Murray, 1956.The Great Shadow (1892)The Exploits of Brigadier Gerard (1896)Uncle Bernac (1897)The Adventures of Gerard (1903)

The Gully of Bluemansdyke (1893) [short stories]

The Parasite (1894)

Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life (1894) [short stories]

The Stark Munro Letters (1895)

The Conan Doyle Historical Romances. Volume 2 of 2. London: John Murray, 1932.The Exploits of Brigadier Gerard (1896)Rodney Stone (1896)Uncle Bernac (1897)The Adventures of Gerard (1903)

The Original Illustrated Arthur Conan Doyle. Castle Books. Secausus, New Jersey: Book Sales, Inc., 1980.The Tragedy of the Korosko (1898)

A Duet, with an Occasional Chorus (1899)

The Green Flag and Other Stories of War and Sport (1900) [short stories]

Round the Fire Stories (1908) [short stories]

The Last Galley (1911) [short stories]

The Complete Professor Challenger Stories. 1952. London: John Murray, 1963.The Lost World (1912)The Poison Belt (1913)The Land of Mist (1926)"The Disintegration Machine" (1928)"When the World Screamed" (1929)

Danger! and Other Stories (1918) [short stories]

Three of Them (1923) [short stories]

The Conan Doyle Stories. 1929. London: John Murray, 1951.Tales of the Ring & the CampTales of Pirates & Blue WaterTales of Terror & MysteryTales of Twilight & the UnseenTales of Adventure & Medical LifeTales of Long Ago

The Maracot Deep. 1929. London: John Murray, 1961.

The Annotated Sherlock Holmes: The Four Novels and the Fifty-Six Short Stories Complete, by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Ed. William S. Baring-Gould. 2 vols. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1967.

The Unknown Conan Doyle: Uncollected Stories. Ed. John Michael Gibson and Richard Lancelyn Green. 1982. London: Secker & Warburg, 1983.

The Uncollected Sherlock Holmes. Ed. Richard Lancelyn Green. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983.

A Study in Scarlet: Based on the Story by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. A Sherlock Holmes Murder Mystery. 1887. Webb & Bower (Publishers) Limited. 1983. London: Peerage Books, 1985.

The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes: After Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Ed. Richard Lancelyn Green. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985.

The Original Illustrated 'Strand' Sherlock Holmes: The Complete Facsimile Edition. 1989. Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions Ltd., 1990.

The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes. Vol. 1: The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes & The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2005.

The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes. Vol. 2: The Return of Sherlock Holmes, His Last Bow & The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2005.

The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes. Vol. 3: A Study in Scarlet, The Sign of Four, The Hound of the Baskervilles & The Valley of Fear. Ed. Leslie S. Klinger. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2006.

Poetry:

Songs of Action (1898)