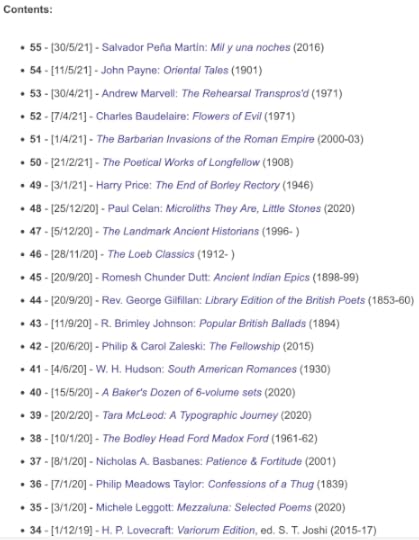

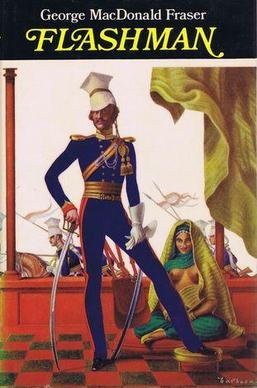

Jack Ross's Blog, page 12

August 31, 2021

Seven Stages of Book Collecting

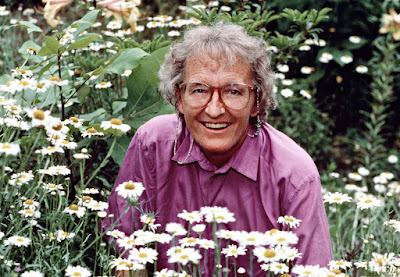

Avow: Elisabeth Kübler-Ross book collection (2019)

In her 1969 book On Death and Dying Swiss-German psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross proposed the celebrated "five stages of grief":

denial anger bargaining depression acceptance(I should perhaps add that the Wikipedia entry on the subject adds - in what seems to me an unnecessarily pompous manner - that:

Although commonly referenced in popular culture, studies have not empirically demonstrated the existence of these stages, and the model is considered to be outdated, inaccurate, and unhelpful in explaining the grieving process.)

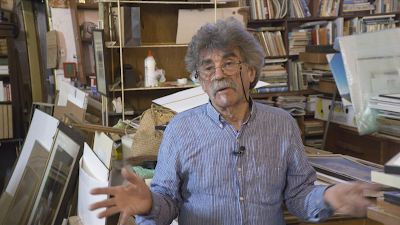

Ken Ross: Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (1926-2004)

Be that as it may, I've decided to follow her example, in a somewhat more humble fashion, by introducing the John Mackenzie Ross "seven stages of book collecting" model. Here it is:

Buy the bookShelve itCover itCatalogue itResearch itRead itWrite about itNaturally, each of these stages may require further exposition. I've more than once been greeted with blank incomprehension when mentioning some (to me) routine aspect of collecting which turned out to be far less self-explanatory than I'd anticipated.

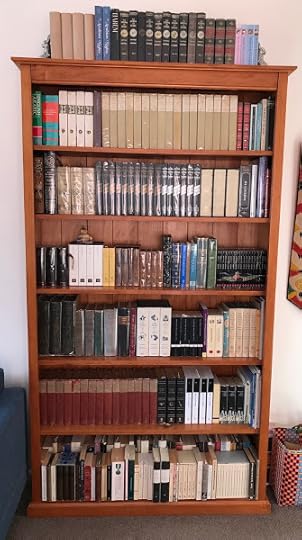

Bronwyn Lloyd: Jack's Arabian Nights Bookcase (30/7/21)

Take, for example, my online interview with novelist Jaspreet Singh on the subject of my 1001 Nights book collection. "When exactly did you start seeing your growing collection as a separate bookshelf?" was one of his questions, and yet to me appropriate display is an obvious outgrowth of the collecting bug.

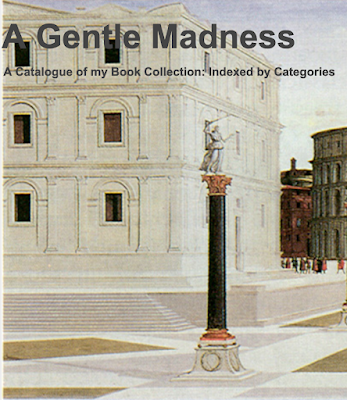

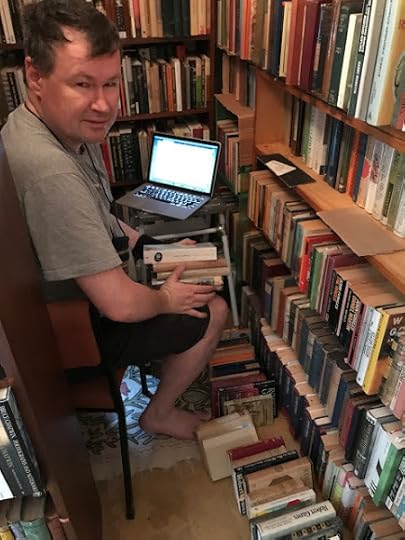

Jack Ross: A Gentle Madness (2009- )

Similarly, one of my ex-students posted the following set of queries on my Book collection blog, A Gentle Madness (prefacing them with the possibly accurate comment, "Captain Jack, you've gone quite mad, but I guess you must have always been this way!"):

Questions:

Did you one day realise you had the makings of a "collection" or was it your intention to "collect"?

What book started your collection (when it first became a collection or when you first realised it)?

Do you read every book you buy?

How do you decide what books to buy? Must they be your personal favourites? Are there boxes you need to tick before a book can be allowed into the collection?

Would you ever allow Stephenie Meyer or Dan Brown in your collection?

These are all good questions, I guess, but they proved surprisingly difficult to answer. I'll leave you to see what kind of a fist I made of that by directing you to the original post here.

•

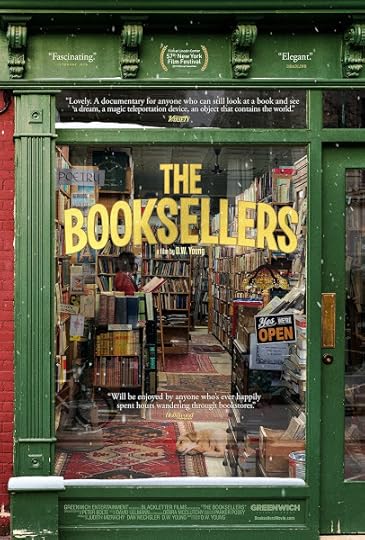

The Booksellers (2019)

Buy the book

The thrill of the chase is probably the most familiar aspect of collecting even to people who don't share this passion themselves. How else account for the immense popularity of such reality TV series as American Pickers or Pawn Stars?

I wrote a post about the Lost Bookshops of Auckland some years ago now, where I tried to convey some of my own nostalgia for the second-hand and antiquarian bookshops which once dotted the city.

Something of the same spirit is conveyed in the recent documentary The Booksellers, which takes us into the inner sanctum of some of New York's most celebrated bookstores.

Now, of course, the game has changed utterly, thanks to the immense convenience and practicality of online purchasing from the likes of Amazon.com or AbeBooks. This, too, is not without its risks and excitements, but it is a somewhat domesticated version of the sport. It's hard to imagine any serious present-day collectors ignoring it when it comes to filling significant gaps in their collections, though.

Mike Wolfe, Danielle Colby-Cushman & Frank Fritz: American Pickers (2010- )

•

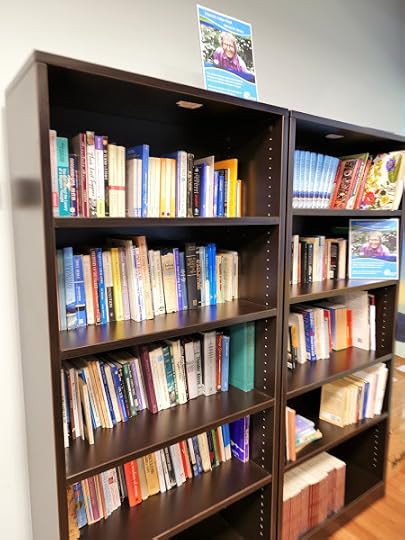

Bronwyn Lloyd: "Before" (2019)

Shelve it

No matter how much shelf space you have, you will fill it eventually. Accordingly, as you'll gather from the "After" picture below, I've had to resort to stowing away my books in double rows.

This is certainly not an ideal way to present them. I've taken to putting one book by some particularly prolific author in the front row, and shelving all the rest of that person's books behind. That way you can deduce with a reasonable amount of certainty what is likely to be there - if you have some idea of the scope of the collection in the first place, that is.

I am not myself a fan of bookcases which graduate the height of the shelves so as to allow for bigger books in one, standard hardbacks in another, and even smaller ones (such as paperbacks) in another. Authors are seldom so obliging as it make all of their books the same size, so one ends up having to run parallel alphabetical rows of books on different levels to accommodate any one writer. Which can be very confusing to outsiders trying to find a specific book.

After considerable research, I've come up with the following rough ratio for the ideal bookcase (for my own requirements, that is). All shelves should have exactly the same dimensions, except for the top one, which should be open on top so as to accommodate exceptionallly large books. Each shelf should be roughly 280 mm. [= c.11 inches] deep, by 280 mm. high. That is tall enough for most books, and also provides ample room for two rows of normal sized volumes. I'd recommend including at least seven shelves, which would add up to a height of 2 metres [= c. 6 feet], with a breadth of at least a metre - or even a metre and a half [= 3-4 feet].

In other words:

Shelves:Aby Warburg saw his own book collection (now housed in the Warburg Institute in London) as a dynamic way of connecting otherwise disparate disciplines. Merely by shelving the books a certain way:

180 mm. deep x

180 mm. high

Bookcases:

1000 mm. tall x

500-750 mm. wide

the library revealed the similarities which existed among each of the investigative approaches pertaining to these disciplines and promoted the insight that multiple problems cannot be solved by considering each of them in isolation.I can make no such lofty claims for my own assortment of disparate titles, but it's true that they do encourage such juxtapositions by the very fact of their coexistence in the same space.

Bronwyn Lloyd: "After" (2019)

•

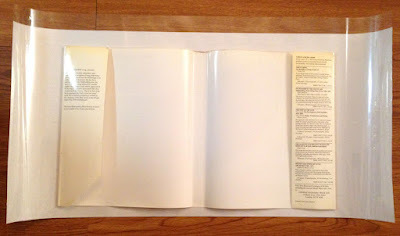

Model Ship World: Covering Dustjackets (2013)

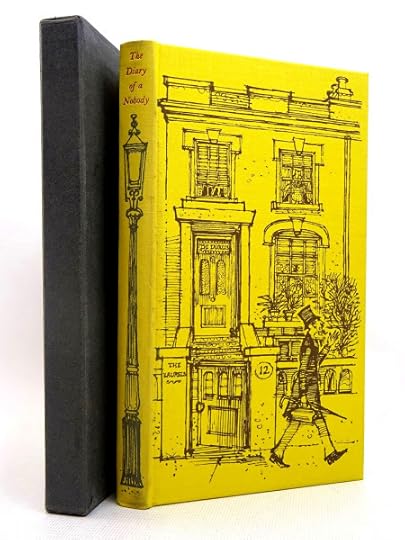

Cover it

For years I've been trying to protect at least a few of my books with plastic covers, but it wasn't until I managed to locate a reliable source of mylar plastic rolls in the past couple of years that I've been able to do this more systematically.

At first it was only hardbacks with dustjackets which received this treatment, but more recently I've taken to covering all the hardbacks, as well as a few of the more vulnerable paperbacks. I make an exception for books in slipcases, as they seem to be quite sufficiently protected already.

Damp air and direct sunlight are the two main enemies of books. The first promotes mould and foxing, the second fades brightly covered spines. Of the two, I prefer sunlight, as I'd rather have a faded dry book than a colourful damp one. Best of all, of course, is a temperature controlled environment (a dehumidifier will help you with this) in a room with appropriately placed curtains.

I am, finally, far more interested in what's inside a book than its outside appearance, but there isn't much point in spending a lot of money on acquiring nice things if you don't take care of them once you have them.

Ubiquitous Books: Mylar Covers for Books (2019)

•

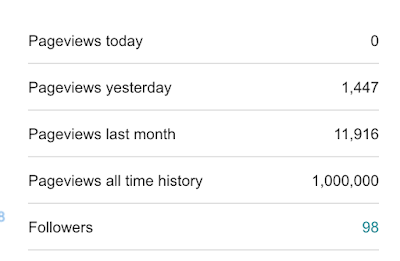

A Gentle Madness (2009- )

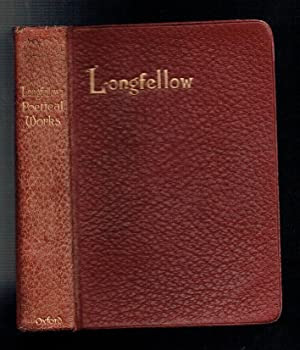

Catalogue it

This is a major part of my collecting endeavour. I catalogue each new book I acquire both by category and by location.

"Mr. Humphries and His Inheritance" is probably my favourite M. R. James story of all time. In it, James relegates his usual ghostly shenanigans to the background even more than usual, since it mostly concerns a bookish young man who's just inherited an old house with a wonderful maze as well as a library of mostly unexamined treasures form a distant relative.

"The drawing up of a catalogue raisonné would be a delicious occupation for winter," is probably the one line from this story which has influenced me most over the years. Yes it would be a "delicious activity" - and it is. Cataloguing can become a chore like any other, but when it's done for pleasure, the possibilities of online book catalogues are as yet in their infancy, I firmly believe.

Besides the principal functions mentioned above, my own book collection website, A Gentle Madness, includes complete listings of the books of favourite authors of mine so that I know what I still need to be be on the lookout for. It also includes a category of posts about recent acquisitions to my library.

Further refinements will no doubt follow. Hopefully they'll be reasonably easy to institute, now that most of the essential data is in place.

Jack Ross: A Gentle Madness: Acquisitions (2012- )

•

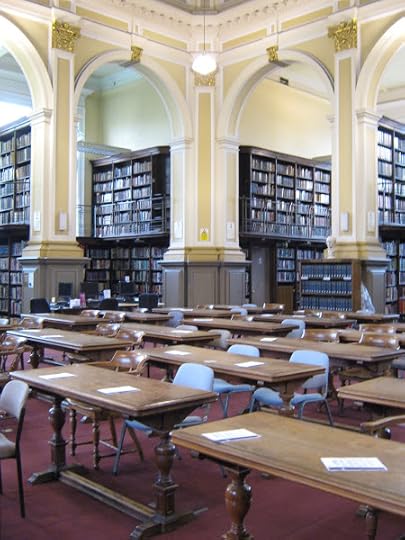

Edinburgh Central Library (2012)

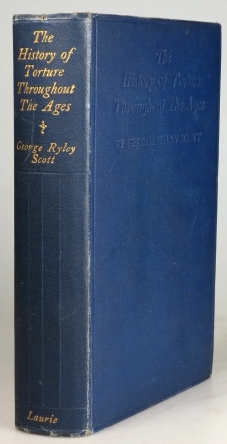

Research it

I suppose, since I have spent thirty years working as a teacher at tertiary level - and ten years as a university student before that - I should know a little bit about this subject.

What's more, I date from an era when dissertations where painstakingly tapped out on typewriters, and when access to a bank of encyclopedias and dictionaries was necessary to provide the necessary facts for literary research.

The horrid truth, though, is that I have a tendency to make my first stop Wikipedia just like most of my students do. And why not? Many of the entries are flawed and incomplete, admittedly, but then so were most of the reference sources I used to access in the university library. The advantage with an online encyclopedia is that one can click on the links to supplement the basic information included there.

It will certainly provide you with most of what you need to know about the contents (and authors) of most of the books in an average library. Beyond that, admittedly, more specialised techniques may hae to be employed - but that's another story (as Rudyard Kipling was probably not the first to say).

Wikipedia (2001- )

•

Eve Arnold: Marilyn Monroe reading James Joyce (1955)

Read it

"Have you read them all?"

This is probably the book collecting equivalent of that infamous question for writers: "Where do you get your ideas?"

No, of course I haven't read all of them. Nor would I really relish looking round at a group of books every one of which I'd already read. "La chair est triste, hélas ! et j'ai lu tous les livres," as Stéphane Mallarmé once put it: "The flesh is sad, alas, and I've read all the books."

I have read a pretty sizeable percentage of them, though, some many times, and am gradually working my way through the others. Interestingly enough, not all book collectors actually do this. There are even some library collections which boast of including only uncut copies, unread and unseen by any human eye.

That's all very well, but my collection exists for use, not ornament. There are a few that are kind of old and delicate, and those I might choose to read in a library copy instead, but most of them I read regardless of any risk to their spines or their ancient acidic paper. It is, after all, a large part of my job, as well as my leisure (though generally somewhat different books).

I am, one might say, a reading machine - by necessity as well as inclination.

Bronwyn Lloyd: Reading at Paekakariki (2013)

•

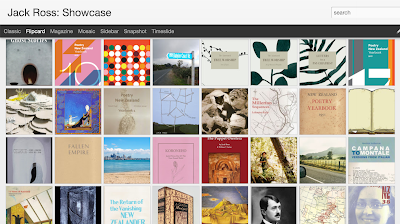

Jack Ross: The Imaginary Museum (2006- )

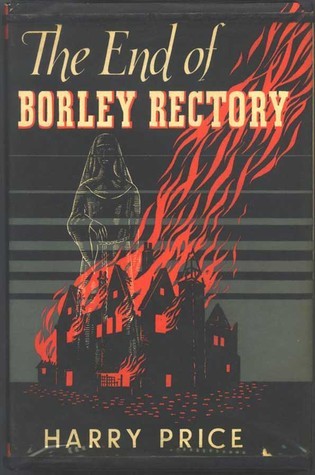

Write about it

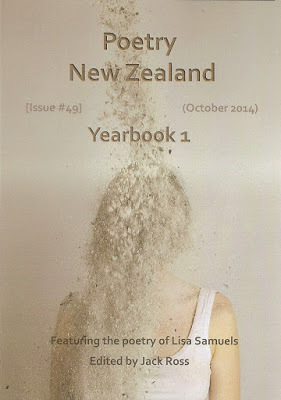

Writing about the books you've bought and read is really the icing on the cake. Ever since I first started this blog in 2006, it's been moving more and more towards an exclusive focus on book collecting. Hence this post, among many others along the same lines, and hence the various series of author or series-focussed blogposts I've written.

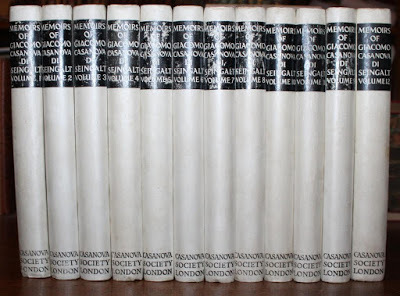

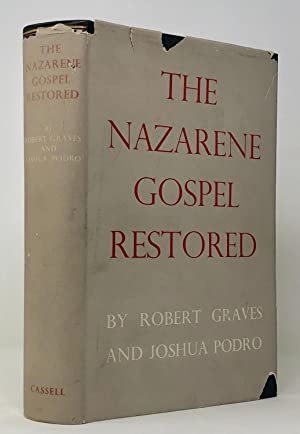

Books are, after all, fascinatingly various objects. They have a physical presence as well as existing on a more ideal or abstract plane. The object interests me as much as its content, in most cases. They can be old or new, big or small, beautifully bound and packaged or scruffily mass-produced.

But I suppose that the main point of collecting them is to connect with them in some way: either by suggesting new ideas or refinements of ideas in you, or just delighting you with "the precious lifeblood of a master spirit, embalmed and treasured up on purpose to life beyond life" (Milton).

A Gentle Madness

So that's a little taste of the background to my madness. What about yours?

I suppose that the term "hobbyist" might be applied by many to what I do here in place of the rather more grandiose "collector." But a collection is nothing but a hobby with a college education (to paraphrase Mark Twain), so yar boo sucks to them!

•

Published on August 31, 2021 14:29

August 14, 2021

Fast Thinkers and Ghost Writers

Britannica: Pierre Bourdieu (1930-2002)

A bit of wisdom here from Pierre Bourdieu:

Fast-thinkers ... think in clichés, in the "received ideas" that Flaubert talks about - banal, conventional, common ideas that are received generally. By the time they reach you, these ideas have already been received by everybody else, so reception is never a problem. But whether you're talking about a speech, a book, or a message on television, the major question of communication is whether the conditions for reception have been fulfilled: Does the person who's listening have the tools to decode what I'm saying?Like most people (I suppose), I used to worry about my inability to shine in contests of quick-flowing wit. I remember once meeting a friend who'd been off at Graduate School in America, and had returned to New Zealand to show off some of what he'd become. The talk came thick and fast, with nary a space to insert a word of one's own, or query exactly what it was we were talking about.

When you transmit a "received idea," it's as if everything is set, and the problem solves itself. Communication is instantaneous because, in a sense, it has not occurred; or it only seems to have taken place. The exchange of commonplaces is communication with no content other than the fact of communication itself. The "commonplaces" that play such an enormous role in daily conversation work because everyone can ingest them immediately. Their very banality makes them something the speaker and the listener have in common.Now, however (thanks largely to Christine Howe), I worry about it less.

- Pierre Bourdieu, 'On Television' (1996/98)

[reference courtesy of Australian novelist Christine Howe, who quoted it at the 'Critical Futures' symposium I attended a couple of years ago at the University of Wollongong]

•

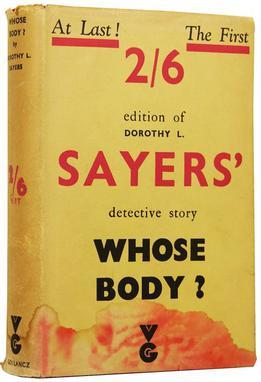

Dorothy L. Sayers: Whose Body? (1923)

At one point the conversation with my friend-recently-returned-from-the-US shifted (for some reason I've now forgotten) to the detective novels of Dorothy Sayers. Now I'd read all of these, in sequence, on more than one occasion, and could easily have answered any random question on campanology or heraldry drawn from her books.

My friend dismissed her quickly with a wry reference to the naming of the evil surgeon Sir Julian Freke ("Freak" - get it?) in her very first novel, Whose Body? , as well as a claim that the book was anti-semitic, given that the murderer's victim was a wealthy financier called Sir Reuben Levy.

Sir Frederick Treves: The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences (1923)

Now this seemed (and seems) - to me - rather a complex matter. The name of Sir Julian Freke had, to my mind, been carefully chosen to recall to the reader that most famous of British surgeons Sir Frederick Treves, discoverer (and promoter) of Joseph Merrick, the (so-called) "Elephant Man."

Treves certainly seems a far more sympathetic figure, so perhaps 'Freke' is supposed to hint at the Mr. Hyde-like double nature lurking in any God-like surgeon. Or perhaps Sayers knew more gossip about Treves than we do now.

Dorothy L. Sayers (1893-1957)

As for the claims of anti-semitism, they don't seem to me to have that much behind them, gruesome though the details of this particular murder undoubtedly are. Certainly Freke is presented as being intensely anti-semitic.

The subject is canvassed interestingly in the Wikipedia article on Dorothy Sayers. Later, in 1936, when "a translator wanted 'to soften the thrusts against the Jews' in Whose Body?, Sayers, surprised, replied that the only characters 'treated in a favourable light were the Jews!'"

In other words: "How can I be a racist? Some of my best friends are [fill in as required ...]."

I guess the overall point I'm trying to make is that my friend, a fast thinker if ever there was one, was onto the next point before any real consideration could be given to this one, wrecked reputations left smoking in his wake. Dorothy Sayers - anti-semite; T. S. Eliot - anti-semite; Pound - Fascist ... and so on and so forth. A label for everyone and the mouth constantly moving on to new aperçus and subtleties: quick subtleties, mind you, so that no-one (such as myself) stoutly bringing up the rear, could be permitted any time to break down or examine the ideas presented.

Talking people down in this matter - battering down their resistance with a shower of facts and figures, flimsy literary and cultural parallels, and random contemporary events, is, of course, one of the more effective ways of ensuring victory in debate. On paper it can seem to work equally well just as long as no-one really reads what you write.

As long as they skate over it in the same way, and at the same speed, that you composed it, the knockdown argument is almost guaranteed.

•

Marina Warner

I'm sorry to say that British cultural critic and historian Marina Warner does seem to me to exemplify some of these traits. Don't get me wrong: I've read a great many of her books, and have received much profit from them. They certainly cover many areas - European folklore and fairy-tales, Ovid's Metamorphoses and the Arabian Nights - which are of profound interest to me. And yet they continue to frustrate me, perhaps because of the speed at which her mind moves from subject to subject.

Here's a list of the books by her I own:

The Dragon Empress: Life and Times of T’zu-hsi (1835-1908), Empress Dowager of China. 1972. London: Cardinal: 1974.Alone of All Her Sex: The Myth and the Cult of the Virgin Mary. 1975. London: Quartet Books, 1978.Joan of Arc: The Image of Female Heroism. 1981. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983.Monuments and Maidens: The Allegory of the Female Form. 1985. London: Vintage, 1996.The Mermaids in the Basement. 1993. London: Vintage, 1994.[Edited] Wonder Tales: Six Stories of Enchantment. Illustrated by Sophie Herxheimer. 1994. London: Vintage, 1996.From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales and Their Tellers. 1994. London: Vintage, 1995.No Go the Bogeyman: Scaring, Lulling and Making Mock. 1998. London: Vintage, 2000.Fantastic Metamorphoses, Other Worlds: Ways of Telling the Self. 2002. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.Signs & Wonders: Essays on Literature & Culture. 2003. London: Vintage, 2004.Stranger Magic: Charmed States & the Arabian Nights. 2011. Vintage Books. London: Random House, 2012.

As you can see, they're a eclectic bunch: history, fiction, literature, folklore ... She certainly covers a lot of ground.

Marina Warner

Her ideas on transformation, cultural fluidity, gender roles, are all very persuasive, and tend to get quoted approvingly by other like-minded writers. But is she reliable? Can you trust her when it comes to tedious matters such as facts and dates?

Not always, I'm sorry to say. Let's take one small example:

Marina Warner: 'Introduction,' to The Arabian Nights (2003)

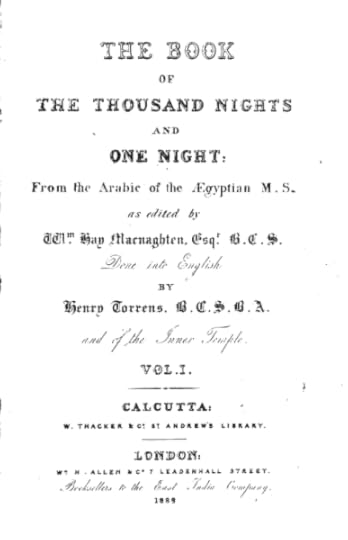

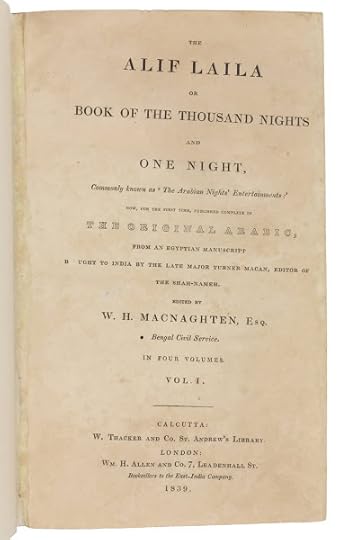

In her introduction to the Folio Society's sumptuous six-volume edition of the Mardrus/Mathers translation of the Arabian Nights, she mentions that:

In the Victorian era, adventure-explorers such as Hugh Lane and Richard Burton, both ardent lovers of Araby, produced translations based on these Arabic compilations. Their editions reflect their own attachments: Hugh Lane's is stuffed full of ethnographical details of Old Cairo (some of it densely researched and nostalgic, other parts rather fanciful): Burton's version is an almost Chattertonian exercise in auncient tongues, prolix and rococo, and is also truffled with lore (much of it salacious, earning Burton his nickname, 'Dirty Dick.'). [p.xiv]But who is this "Hugh Lane" she is speaking of? There was a Hugh Lane (1875-1915), drowned by the sinking of the Lusitania, who is famous for having attempted to leave his priceless collection of impressionist paintings to his native country, Ireland, only to be rebuffed by the local Dublin authorities.

But the Lane Warner means is clearly Edward William Lane (1801-1876), who was indeed the first major translator of the Nights from Arabic into English. I don't think anyone has ever accused him of writing especially "nostalgically" about "Old Cairo", though - let alone "fancifully". On the contrary, his classic work on the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians (1836), remains a most informative and detailed guide to the city, compiled - as it was - in consultation with a number of local Sheikhs. His main claim to fame, however, is the comprehensive Arabic-English Lexicon, which occupied him from 1842 until his death.

Warner is on safer ground with Richard F. Burton. Her description of his work as a "Chattertonian exercise in auncient tongues" is certainly accurate enough. Fans of his version - such as myself - may feel a little affronted by her casual dismissal of this massive labour of love, but she is (of course) perfectly entitled to her opinion, which is by no means an uncommon one.

Marina Warner: Stranger Magic (2012)

A few years later, in her book Stranger Magic, she admitted having mainly relied on the most recent French translation of the Nights - by Jamel Eddine Bencheikh and André Miquel, 3 vols (Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, 2005-7) - in preference to any of the English ones. Had she actually read them? She certainly implies as much. Here, for instance, is her revised version of the paragraph quoted above:

In the Victorian era, adventure-explorers such as Edward W. Lane and Richard Burton, both ardent Arabophiles, produced translations that reflected their own attachments. Lane's, published in 1838-41, followed close on the heels of his ethnographical description of contemporary Cairo (The Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians, 1835); Lane added a huge apparatus of notes on Arab Society (some of it densely researched and nostalgic, other parts rather fanciful). The three-volume set of 1850 includes 600 engravings based on Lane's experiences in Cairo; my copy, which came originally from my great-grandmother's library, is one of the few books that I've owned and read since I was a child, and though it is pretty fustian, with Lane tranquillising so much of the book's agitated emotions and adventures, it is readable to a degree that Richard Burton's lurid and archaising version, made fifty years later, never reaches. [p.18]It's not for me to cast any doubt on the passage referring to her childhood reading of Lane. It just seems a bit odd that someone who didn't even know (or bother to check) his first name a decade before, should treasure a copy of his translation as "one of the few books that I've owned and read since I was a child."

The snap judgements of the first version of the passage remain - "rather fanciful," "translations that reflected their own attachments" - though she has softened some of the more egregious epithets: "lovers of Araby" has become "Arabophiles", and Burton's version is now "lurid and archaising" rather than "an almost Chattertonian exercise in auncient tongues, prolix and rococo ... truffled with lore (much of it salacious ...)."

I certainly don't question Warner's choice of texts to base her discussion on. I, too, am an admirer of the wonderful new French translation: It's just difficult to continue to believe in the reliability of a scholar who was hazy about E. W. Lane's first name - and certainly seems never to have read extensively in Burton's work - as a reliable guide to the intricacies of one of the world's longest books, with a complex textual history which spans cultures and continents as well as millennia of analogues.

In other words, beguiling as so many of Warner's generalisations and juxtapositions are, none of her statements - especially those centred around dates and names - can be trusted without further research. Which is really not much use. Even historical and cultural popularisers (a very worthwhile calling, IMHO) should be careful to check their facts. What exactly are they popularising, otherwise?

•

Helen Sword: Ghostwriting Modernism (2002)

My final exhibit is the book Ghostwriting Modernism, by Auckland University Academic Helen Sword. Like Warner's, Sword's pages are plastered her pages with allusions and lists of possible parallels. Unlike Warner's, though, her notes are a carefully composed repository of bibliographical leads and further information.

In terms of readability, it's probably no accident that Warner's book flew off the shelves whereas Sword's is obtainable only in university libraries and from specialist booksellers. If it weren't for my fascination with its subject-matter - the manifestation of spiritualist tropes in such canonical authors as Joyce, Yeats, Eliot, H. D., Plath and Hughes - I probably wouldn't have bothered to read it myself.

But, having now done so, I've shelved it close to hand for further consultation. This is a book which is more than the sum of its parts. It opens perspectives on masses of further work on such fascinating exhibits as James Merrill's Ouija-board epic The Changing Light at Sandover, or the spirit messages from dead RAF pilots which H. D. collected in the latter years of the Second World War, which have proved such an embarrassment to many of her admirers.

Everyone already knew that Yeats was a convinced Occultist, but simply collecting - in convenient form - so much data on the phenomena of 'ghostliness' in such mainstream twentieth century writers makes it almost impossible to continue to sideline it as some kind of individual aberration on the part of each of them.

That's not to say that there isn't something a bit loony about Sylvia and Ted crouched over the Ouija board receiving messages from the great unknown. But it certainly isn't nearly as odd and uncommon as many critics would like to believe. Did they do it, like Yeats, to access new "metaphors for poetry"? Or was it something more serious for them? All this, and much more, is discussed judiciously, and with ample cross-referencing, by Helen Sword.

Helen Sword

Fast-thinkers or Ghostwriters? So many books now fall into the first category, I'm afraid. You start to read them, only to become gradually aware that they're little more than condensations of the idées reçues [received ideas] mocked so thoroughly by Flaubert in the "Dictionnaire des idées reçues" in his posthumous novel Bouvard et Pécuchet (1881). The research is sloppy and second-hand, the editing perfunctory, and the whole thing a mere "interruption to our studies," in A. E. Housman's devastating phrase.

Think of all those war books which keep on flopping out year after year: Martin Middlebrook's The First Day on the Somme (1971) was regarded as a seminal and revisionist work when it first appeared some fifty years ago now. Now, of course, further research has thrown in doubt many of its conclusions, but do we really need successive legions of books with more or less the same title, gloatingly recounting the same devastating events?

There's a furtive voyeurism about the worst of these books. They look like real books - their publishers try hard to make them resemble genuine historical works - but actually they're just rehashes of the same tired clichés. How many hacks have written books designed to show that Sir Douglas Haig was a great general, a genius on the level of Napoleon or Marlborough? He won, didn't he? And he was British, after all.

The trouble is that the real books concealed in this crimson tide of white noise, those based on real research and genuine new thinking, increasingly seldom emerge from the ruck. Ghostwriting Modernism is such a book. It's not perfect by any means - but it's certainly based on careful reading over many years. Stranger Magic, despite all the extravagant encomia reprinted on its cover ("a flying carpet of a book" - Jeanette Winterson), is, I'm afraid, not. It's hard, even, to say what it's actually about. Does it have a point? Or a theme? If so, I'm not really clear what it is, despite having read it assiduously from cover to cover.

And, when it comes to new books about the Arabian Nights, I can assure you that I'm not a particularly critical reader. Pretty much any and all authors of such can rely on me as a captive audience!

Ghost Writing Book

•

Published on August 14, 2021 16:15

August 11, 2021

Jane Langton's The Swing in the Summerhouse

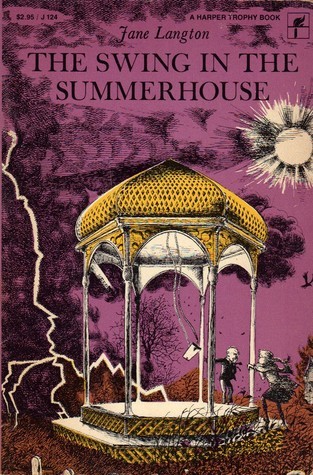

Jane Langton: The Swing in the Summerhouse (1967)

We were always on the lookout for good fantasy novels when we were kids, and after reading all about C. S. Lewis's Narnia, Ursula Le Guin's Earthsea, and J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth, we were rather at a loss. One day I overheard my brother and sister arguing over the merits of a book called The Swing in the Summerhouse.

Anne (I think) quite liked it, whereas Ken found it too doctrinaire. In any case, I resolved to give it a try, and since it turned out to be in the Murrays Bay Intermediate School library, I must have borrowed and read it sometime in the early 1970s.

I thought it very good: better, even, than Madeleine L'Engle's A Wrinkle in Time , which I encountered at roughly the same time. It was a little frustrating, though, as it made numerous references to an earlier book called The Diamond in the Window, which it turned out that my older siblings had read, but which was unfortunately not in the library (perhaps one of the teachers had lent it to them).

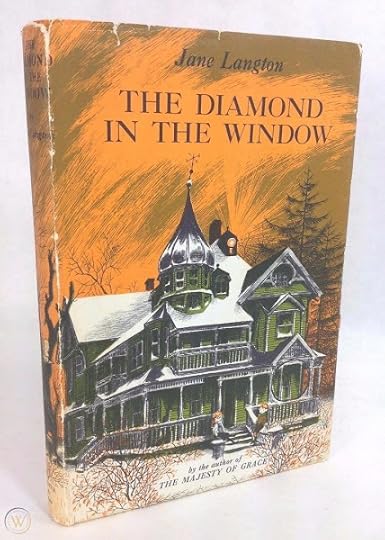

Jane Langton: The Diamond in the Window (1962)

I was pretty excited when I finally ran across a copy of The Diamond in the Window in the local bookshop in Palmerston North (where I was then teaching). The date on the inside cover tells me that it was on my birthday in 1991, so I must have bought it for myself as a present.

You know how it is with old children's books, though - unless you managed to read them at precisely the right moment, their charm can be lost on you. The Diamond in the Window was too obviously infused with Emerson and Thoreau and their Transcendentalist ideology (a bit like Lewis and Tolkien's Christianity), so I couldn't really surrender to it properly. Nor was I able to find a copy of The Swing in the Summerhouse to compare it with, despite searching in vain for many years.

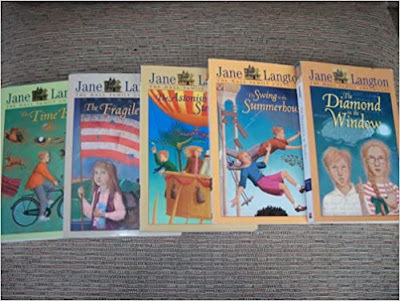

Jane Langton: The Hall Family Chronicles (1962-2008)

The Diamond in the Window (1962)The Swing in the Summerhouse (1967)The Astonishing Stereoscope (1971)The Fledgling (1980)The Fragile Flag (1984)The Time Bike (2000)The Mysterious Circus (2005)The Dragon Tree (2008)

The other day I gave in and decided to order the whole series online. It came as a bit of a surprise to find out that Jane Langton had lived until 2018, and even added three new volumes to her series of "Hall Family Chronicles" in the years since 1991!

But then, just the other day, I found a couple of the books in (respectively) The Hard-to-Find Bookshop and Green Dolphin Bookshop in Uptown Auckland, and so I'm glad to have been able to read the first two again, after (respectively) 30 and 50 years. That last seems unbelievable. Can it really have been fifty years since I first read The Swing in the Summerhouse?

In any case, here they all are, in chronological order:

The Diamond in the Window (1962)

Langton, Jane. The Diamond in the Window. Illustrations by Eric Blegvad. 1962. The Hall Family Chronicles, 1. A Harper Trophy Book. New York: Harper & Row, 1973.

Jane Langton: The Diamond in the Window (1962)

The Swing in the Summerhouse (1967)

Langton, Jane. The Swing in the Summerhouse. Illustrations by Eric Blegvad. 1967. The Hall Family Chronicles, 2. Harper Trophy. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1981.

Jane Langton: The Swing in the Summerhouse (1967)

The Astonishing Stereoscope (1971)

Langton, Jane. The Astonishing Stereoscope. 1971. The Hall Family Chronicles, 3. HarperTrophy. New York: HarperCollins Publishers Inc., 2001.

Jane Langton: The Astonishing Stereoscope (1971)

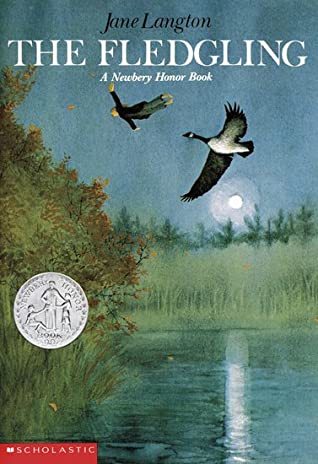

The Fledgling (1980)

Langton, Jane. The Fledgling. Illustrations by Eric Blegvad. 1980. The Hall Family Chronicles, 4. New York: Scholastic Inc., 1990.

Jane Langton: The Fledgling (1980)

The Fragile Flag (1984)

Langton, Jane. The Fragile Flag. 1984. Hall Family Chronicles, Book 5. New York: HarperCollins, 2002.

Jane Langton: The Fragile Flag (1984)

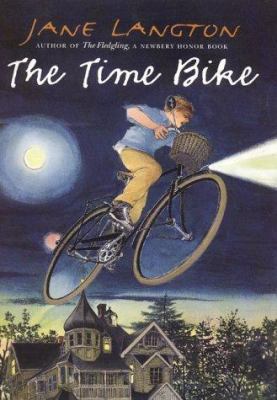

The Time Bike (2000)

Langton, Jane. The Time Bike. 2000. Hall Family Chronicles, Book 6. New York: Scholastic, 2003.

Jane Langton: The Time Bike (2000)

The Mysterious Circus (2005)

Langton, Jane. The Mysterious Circus. Hall Family Chronicles, Book 7. New York: HarperCollins, 2005.

Jane Langton: The Mysterious Circus (2005)

The Dragon Tree (2008)

Langton, Jane. The Dragon Tree. Hall Family Chronicles, Book 8. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2008.

Jane Langton: The Dragon Tree (2008)

Mind you, some of the initial, non series-focussed cover illustrations for the individual volumes seem more spirited than the ones included above: this moonlit scene for The Fledgling, for instance:

Jane Langton: The Fledgling (1980)

Or this turbulent, energetic image of The Time Bike:

Jane Langton: The Time Bike (2000)

As for the books themselves, what's the verdict, after all these years? Was it really worth the wait?

I can certainly understand why it was The Fledgling which got signalled out from the rest of the series to be a Newbery Honor Book (runner-up to the Newbery Medal, awarded for each year's "most distinguished contribution to American literature for children" since 1922).

The Fledgling is more intimate and engaging than some of the others, and its characters are less easily divisible into goodies (Transcendentalists) and baddies (Materialists). All of them have their own magical charm, though, and I have to say that I only wish they'd all been available to me fifty years ago when I was truly desperate for such reading.

•

Jane Langton (1922-2018)

Published on August 11, 2021 16:08

July 21, 2021

The Enigma of George Borrow

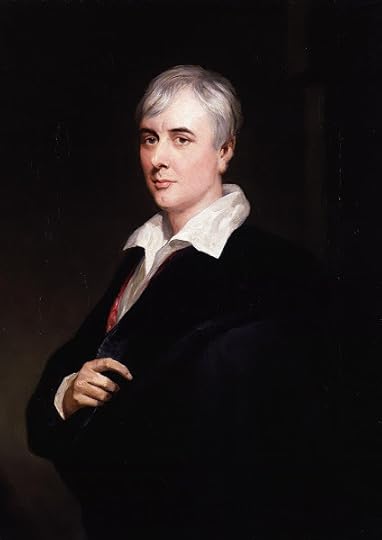

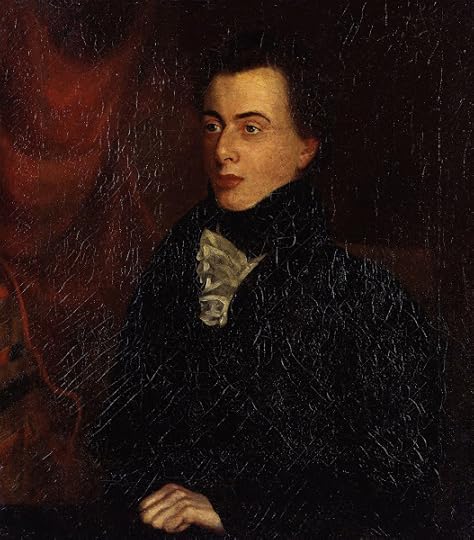

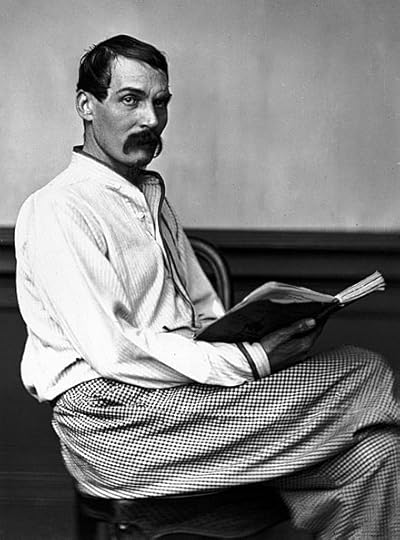

Henry Wyndham Phillips: George Borrow (1843)

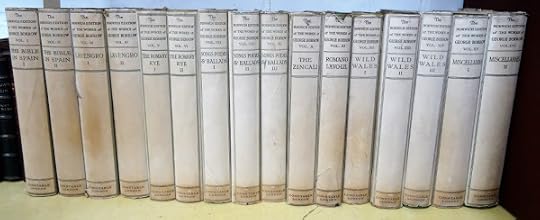

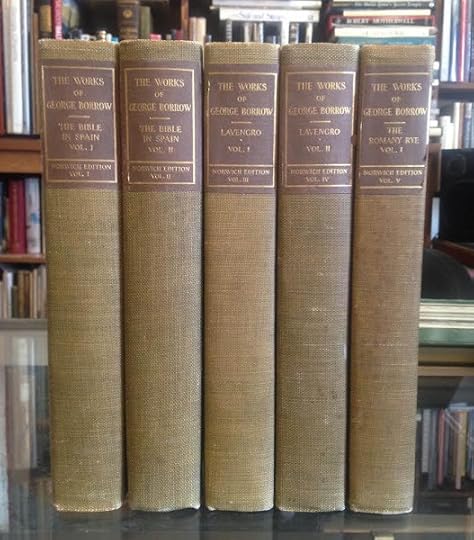

The Works of George Borrow: Edited with Much Hitherto Unpublished Manuscript. Ed. Clement Shorter. Norwich Edition (limited to 775 copies). 16 vols. London: Constable & Co. Ltd. / New York: Gabriel Wells, 1923-24.The Bible in Spain: or the Journey, Adventures, and Imprisonment of an Englishman in an Attempt to Circulate the Scriptures in the Peninsula (1843)The Bible in Spain [vol. 2]Lavengro: The Scholar, the Gypsy, the Priest (1851)Lavengro [vol. 2]The Romany Rye (1857)The Romany Rye [vol. 2]The Songs of Scandinavia, and Other Poems & Ballads (1829)The Songs of Scandinavia [vol. 2]The Songs of Scandinavia [vol. 3]The Zincali: An Account of the Gypsies in Spain (1841)Romano Lavo-Lil: A Wordbook of the Anglo-Romany Dialect (1874)Wild Wales: Its People, Language and Scenery (1862)Wild Wales [vol. 2]Wild Wales [vol. 3]Miscellanies [vol. 1]Miscellanies [vol. 2]

Clement Shorter, ed.: The Works of George Borrow (16 vols: 1923-24)

Does this set of books remind you of anything? Probably not. After all, this is quite an unusual juxtaposition of authors - and texts:

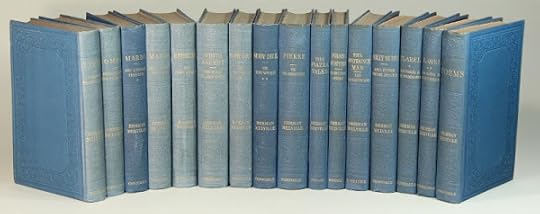

Raymond Weaver, ed.: The Works of Herman Melville (16 vols: 1922-24)

Same publisher. Same number of volumes. Roughly the same date of publication, and (at the time, at least), almost the same degree of obscurity.

The Works of Herman Melville. Ed. Raymond Weaver. 16 vols. London: Constable, 1922-24.Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life (1846)Omoo: A Narrative of Adventures in the South Seas (1847)Mardi: And a Voyage Thither (1849)Mardi [vol. 2]Redburn: His First Voyage (1849)White-Jacket; or, The World in a Man-of-War (1850)Moby-Dick; or, The Whale (1851) [1]Moby-Dick [vol. 2]Pierre; or, The Ambiguities (1852)Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile (1855)The Piazza Tales (1856)The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade (1857)Billy Budd and Other Prose Pieces (1924)Clarel: A Poem and Pilgrimage in the Holy Land (1876)Clarel [vol. 2]Poems (1924)

Of course we now know that this same edition of Melville - the first to collect all of his disparate works (including "Billy Budd", published here for the first time) - would lead directly to the Melville revival, that swelling chorus of interest, appreciation, and (eventually) obsession which would culminate in crowning him one of the world's great authors.

I've written more about this process here.

George Borrow: Collected Works (1923-24)

But what of George Borrow? No such luck, I'm afraid. His mid-nineteenth-century vogue, based principally on that swashbuckling travel yarn The Bible in Spain (1843) - just as Melville's was on Typee (1846) - grew into something of a cult among readers of his distinctly less bestselling autobiographical novels Lavengro (1851) and The Romany Rye (1857).

He even reached the level of being mocked and parodied by the frontrunner of a new wave of popular fiction writers, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, in his 1913 short story "'Borrow'-ed Scenes":

"It cannot be done. People really would not stand it. I know because I have tried." — Extract from an unpublished paper upon George Borrow and his writings.

Thomas Derrick: Illustrations for "'Borrow'-ed Scenes" (1913)

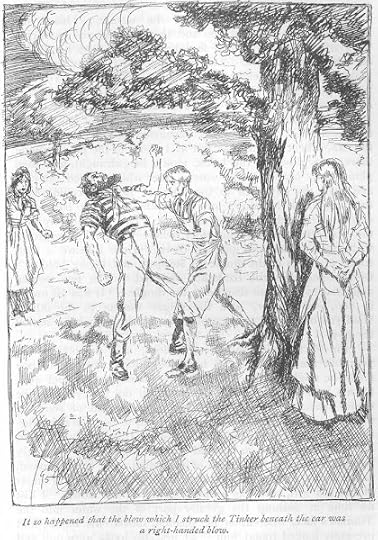

Doyle's rather malicious story portrays the misadventures of a deluded fan who attempts to go about the countryside behaving like the semi-autobiographical protagonist of Borrow's books: accosting Gypsies with snatches of Romany, offering to fist-fight unruly tinkers, and attempting to impress barmaids with his high-flown patter.

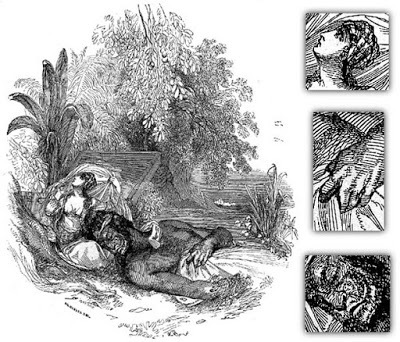

E. J. Sullivan: Lavengro fights the flaming tinker (1900)

Naturally the results are not good. But then anyone who set out to cross America using the methods of Jack Kerouac's similarly semi-autobiographical spokesman "Sal Paradise" from On the Road would hardly fare much better ...

Jack Kerouac: On the Road (1958)

What then, in the Victorian era, seemed bizarre: the deliberate fabrication of a "travel persona" to act as your print protagonist, is now commonplace. The "Bruce Chatwin" or "Bill Bryson" of the travel books resemble only in part those actual individuals.

Travel literature, though it continues to be shelved under "non-fiction" in libraries and bookshops, has always contained a good deal of more-or-less true, or grotesquely exaggerated, or even downright invented material.

Augustus Burnham Shute: Illustration for Melville's Typee (1892)

Melville had the same problem with his own early works. People simply could not get it through their heads that his first book Typee was a novelised version of reality, not a direct transcript of events. So beguiled were they with the winsome Fayaway, from that far-off cannibal valley in the Marquesas Islands (as you can see from the illustration above, her appeal, in the buttoned-up United States of the mid-nineteenth century, is not so terribly hard to fathom), that Melville became, overnight, a kind of sex symbol.

The trouble was that whatever Melville was (and he himself never seemed quite sure), it certainly wasn't that. He was a very much stranger proposition: more of a forerunner of Kafka or Borges than an American avatar of Victor Hugo.

I've written quite a lot about Melville on this blog (and elsewhere): about his poetry; about the claims of Moby-Dick to be considered that mythical beast, the Great American Novel; also about the trials and tribulations of his principal biographer, Hershel Parker. However, I've never written about George Borrow before, despite my early exposure to his works in the form of the beguiling and bewildering Lavengro.

E. J. Sullivan: The Rommany chi (1900)

Why is that? I suppose because despite the obvious parallels between the two, the differences are perhaps even more striking. To put it simply, Borrow never wrote a Moby-Dick or a "Bartleby." Nor, unfortunately, do his posthumous papers appear to contain any lurking parallels to Billy Budd: just piles and piles of poems and ballads in translation.

His fanatical anti-Catholicism is a bit offputting, too - and there's something rather un-English about his boastful self-vaunting and his obvious pride in his own linguistic and literary accomplishments. One can't help feeling, though, that if he had written in a country more in need of literary heroes, as America certainly was in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, that he might have carved out more of a place in the pantheon for himself.

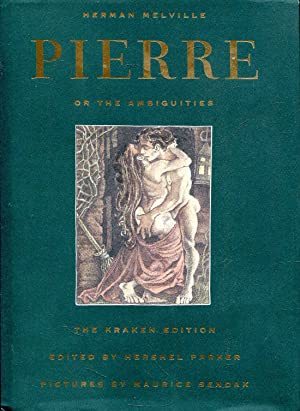

Melville too (dare one say it) has his faults. There's a laborious jocularity in many of his short stories, for instance, which robs them of their full effect. Even the very best of them, "Bartleby," is nearly ruined at the last minute by that add-on information about the "Dead Letter Office." Pierre may have been unjustly criticised at the time for its challenging theme of emotional incest, but even one of his greatest admirers, Hershel Parker, has taken it upon himself to "improve" it by removing the bitter middle section about Pierre's misadventures as an author:

Herman Melville: Pierre: The Kraken Edition, ed. Hershel Parker (1851 / 1995)

Borrow, let's state it plainly, is no Melville. He operates on a distinctly different plane than that. But his charms and accomplishments as an author are many.

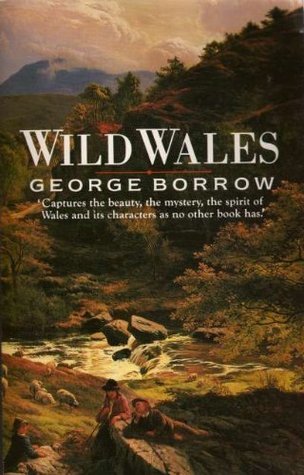

Or so (at least) it appears to me. The wikipedia entry on his 1862 travel book Wild Wales describes his narrative voice as "distinctive and at times a little overbearing," and complains that he "never returned to deepen his knowledge and failed to cover the many parts of Wales he left out of this work." I suppose that few books cover the many things they were forced to leave out, when you really think about it.

George Borrow: Wild Wales (1862)

My suspicion that the author of this entry must be a disgruntled native Welshman is deepened by the following passage:

The author makes much of his self-taught ability to speak the Welsh language and how surprised the native Welsh people he meets and talks to are by both his linguistic abilities and his travels, education and personality, and also by his idiosyncratic pronunciation of their language.I suspect I would feel much the same if I were forced to read the peregrinations of some Sassenach bigmouth through the Scottish Highlands, but since I have no such emotional link to Wales, I'm able to interpret this particular work as quite readable and charming. I can, however understand why this particular page has not one but two notices on it for "imprecise citations" and "importation of original research"!

Borrow, then, is definitely an acquired taste. I fear that I acquired it long ago, when I first picked up a copy of Lavengro in a local secondhand shop. Even now I can't look through its pages without having my spirits lifted: it seems so alive still.

You may not have the same experience, mind you. He is odd, a very eccentric (and egocentric) writer. But then I'm reliably informed that there are many who are impervious to the charms of Melville, too - who can't get past the first page of Moby-Dick, and don't see what all the fuss is about "Billy Budd." I defy them to say that of "Bartleby," though.

Bruce Robinson, dir.: Withnail and I (1987)

The experience of reading Borrow for the first time is (dare I say it) a little like that morning walk in the country taken by the eponymous hero of Withnail and I. As he ruefully concludes, the terrifying locals he encounters are not at all like the denizens of the H. E. Bates novel he's been reading. They're something stranger, darker - and funnier - altogether.

•

John Thomas Borrow: George Borrow (c.1821-24)

George Henry Borrow

(1803-1881)

Collections:

Translations. Ed. Thomas J. Wise. 42 vols. Privately Printed, 1913-14.The Works of George Borrow, Edited with Much Hitherto Unpublished Manuscript. Ed. Clement Shorter. Norwich Edition. No. 533 of 775. 16 vols. London: Constable & Co. Ltd. / New York: Gabriel Wells, 1923-24.The Bible in Spain: or the Journey, Adventures, and Imprisonment of an Englishman in an Attempt to Circulate the Scriptures in the Peninsula (1843) [1]The Bible in Spain [2]Lavengro: The Scholar, the Gypsy, the Priest (1851) [1]Lavengro [2]The Romany Rye (1857) [1]The Romany Rye [2]The Songs of Scandinavia, and Other Poems and Ballads (1829) [1]The Songs of Scandinavia [2]The Songs of Scandinavia [3]The Zincali: An Account of the Gypsies in Spain (1841)Romano Lavo-Lil: A Wordbook of the Anglo-Romany Dialect (1874)Wild Wales: Its People, Language and Scenery (1862) [1]Wild Wales [2]Wild Wales [3]Miscellanies [1]Miscellanies [2]Ballads of All Nations: A Selection. 1826, 1835, 1913, 1923. Ed. R. Brimley Johnson from the Texts of Professor Herbert Wright. London: Alston Rivers Ltd., 1927.

Books:

The Zincali: An Account of the Gypsies of Spain. 1841. London: John Murray, 1908.The Bible in Spain: or, The Journeys, Adventures, and Imprisonments of an Englishman in an Attempt to Circulate the Scriptures in the Peninsula. 1843. Ed. Ulick Ralph Burke. London: John Murray, 1912.Lavengro: The Scholar, The Gypsy, The Priest. 1851. Illustrated by Claude A. Shepperson. Introduction by Charles E. Beckett. London: The Gresham Publishing Co. Ltd., n.d.The Romany Rye. 1857. The Nelson Classics. London: Thomas Nelson & Sons Ltd., n.d.Wild Wales. 1862. Introduction by Brian Rhys. The Nelson Classics. London: Thomas Nelson & Sons Ltd., n.d.Romano Lavo-Lil: A Wordbook of the Anglo-Romany Dialect (1874)

Translations:

Tales of the Wild and Wonderful (London: Hurst, Robinson, and Co., 1825)Klinger, Friedrich Maximilian. Faustus, his Life, Death and Descent into Hell. 1791 (Norwich: W. Simpkin and R. Marshall, 1825)Romantic Ballads, Translated from the Danish; and Miscellaneous Pieces (Norwich: S. Wilkin / London: John Taylor / Wightman and Cramp, 1826)The Talisman: From the Russian of Alexander Pushkin, with Other Pieces (St Petersburg: Schulz and Beneze, 1835)Targum, or Metrical Translations from Thirty Languages and Dialects (St Petersburg: Schulz and Beneze, 1835)[with Stepan Vaciliyevich Lipovtsov] The Manchu New Testament (St Petersburg: The British and Foreign Bible Society, 1835)The Gypsy Luke [Embéo e Majaró Lucas] (1837)Wyn, Elis. The Sleeping Bard, or Visions of the World, Death and Hell. Translated from the Cambrian British (London: John Murray, 1860)The Turkish Jester; or, The Pleasantries of Cogia Nasr ediin Efendi. Translated from the Turkish (Ipswich: W. Webber, 1884)Ewald, Johannes. The Death of Balder: From the Danish (London: Jarrold & Sons, 1889)

George Borrow: Collected Works (1923-24)

Published on July 21, 2021 15:52

July 9, 2021

A Memorial Brass: i.m. Ted Jenner (1946-2021)

Ted Jenner and friends

[l-to-r: Hamish Dewe, Jack Ross, Ted Jenner, Brett Cross]

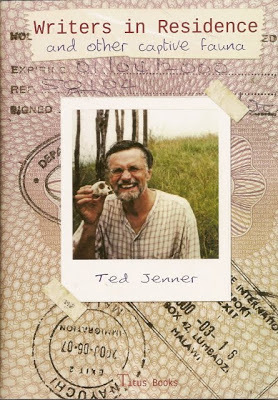

Edward [Ted] Jenner (1946-8 July 2021) was a friend of mine. I guess one of the things I appreciated most about Ted was his unfailing cheerfulness and unflappability even when things appeared to be going very, very wrong indeed.

Perhaps it was his long years working as a Classics lecturer in Malawi that accustomed him to sudden emergencies, or perhaps it was the hand-to-mouth nature of his life as a writer and teacher in New Zealand, but I never saw him at a loss for a wise and witty thing to say.

I had heard that he was ill, and even in hospital, but I'm sorry to say that the news of his death from cancer in the early hours of Friday morning still came as a shock. He wore his years lightly. He was one of that group of baby-boomer New Zealand poets, all born in 1946, at the close of World War II – Sam Hunt, Bill Manhire, Ian Wedde prominent among them – who've been so influential on our literature.

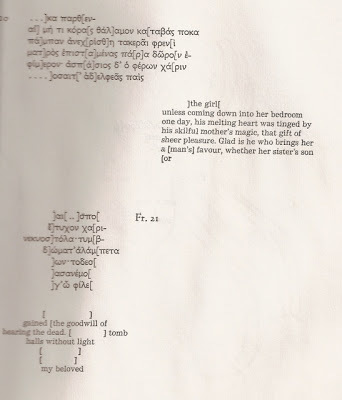

Much though I always enjoyed chatting to Ted – he was a marvellously learned man, a trained classicist with an expertise in Ancient Greek – I suppose it would be true to say that my only real intimate knowledge of him came through his books. The below is probably not a complete list, but it includes all the titles I myself own:

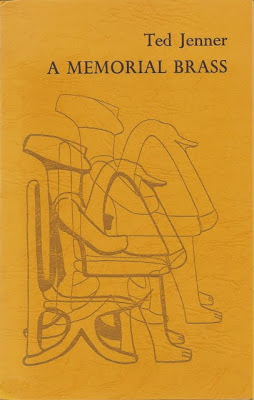

Ted Jenner: A Memorial Brass (1980)

A Memorial Brass. Eastbourne, Wellington: Hawk Press, 1980.

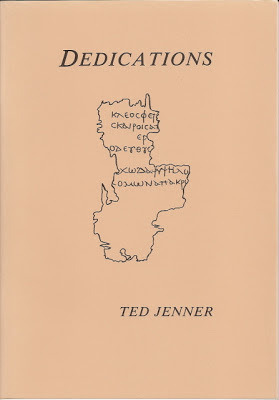

Ted Jenner: Dedications (1991)

Dedications. Auckland: Omphalos Press, 1991.

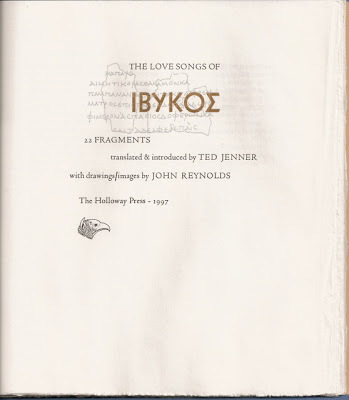

Ted Jenner: Love Songs of Ibykos (1997)

The Love-Songs of Ibykos: 22 Fragments. Images by John Reynolds. Auckland: Holloway Press, 1997.

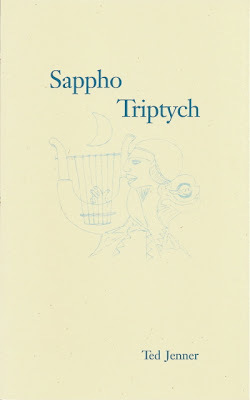

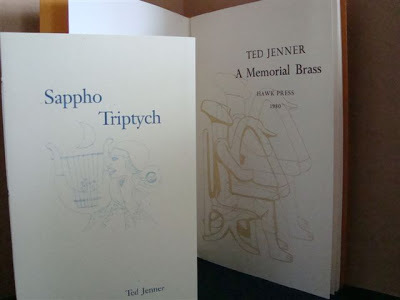

Ted Jenner: Sappho Triptych (2007)

Sappho Triptych. Auckland: Puriri Press, 2007.

Ted Jenner: Writers in Residence (2009)

Writers in Residence and Other Captive Fauna. Auckland: Titus Books, 2009.

Ted Jenner, ed.: brief the fortieth (2010)

brief 40 (July 2010). Ed. Ted Jenner. Auckland: Titus Books, 2010.

Ted Jenner: The Gold Leaves (2014)

The Gold Leaves (Being an Account and Translation from the Ancient Greek of the 'So-Called' Orphic Tablets). Pokeno: Atuanui Press, 2014.

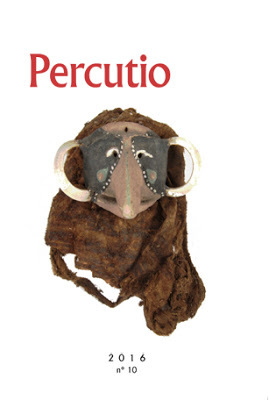

Bill Direen, ed.: Percutio 10: Ted Jenner Issue (2016)

Complete Gold Leaves: Transcriptions of Sixteen Ancient Greek Gold Lamellae. Compiled with English Translations. Dunedin: Percutio Publications, 2016. [In Bill Direen, ed. Percutio 10: A Special Issue devoted to two projects by Classicist and poet Edward Jenner (2016).]

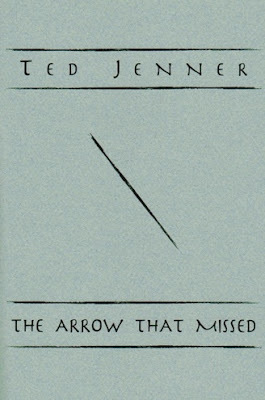

Ted Jenner: The Arrow That Missed (2017)

The Arrow that Missed. Lyttelton: Cold Hub Press, 2017.

Ted Jenner: Sappho Triptych (1980)

Looking back, I seem to have written quite a lot about Ted's work over the years:There's a brief introduction to it here, on this blog.Then there's my review-essay of his Writers in Residence, on the online poetics journal Ka Mate Ka Ora .And, more recently, there's my review of The Arrow that Missed from Poetry NZ Yearbook 2018 .

I'm not sure that there's any need to repeat all that here. Suffice it to say that for me, Ted Jenner combined the twin virtues of precise, scrupulous scholarship with an equally strong taste for experimental fiction and poetry – not that I think he saw much difference between the two genres, and, the way he wrote, there really wasn't.

I borrowed the title for this piece from his earliest book, A Memorial Brass, exquisitely printed by Alan Loney at the Hawk Press in 1980. I'd like to conclude with some more of Ted's own words, taken from the title poem:

My dear, they call us bourgeois

But it was essentially

A bourgeois thing to do –

An image of conjugal

Faith – to cross the hands over chest

And breast and stand on

The goblin pups, a monumental

Brass patent

For the bloodstream-fevers.

I remember it was cold

That May with added expense, upkeep

of allotment, and late

Spring blooms falling fierce as

Snow on the gale-lashed

Oats. Very soon a priest mumbled eight

Sacrificia patriarchae nostri

Above us. Commenting now on the

Canon of his mass, I

Like to think it was

Easy in Abraham's time –

Knowledge and fear were deliberate

Then, total, without cover; but

As for us, we lie awake

Until the sleeping's over.

My profoundest condolences to Ted's wife, Vasalua. If he were here I'm sure he could find the perfect words to thank her for making the last years of his life perhaps the happiest of all.

As for me, I'd like to say once more Ave atque Vale: Hail and farewell, to one of the finest scholars and poets I've ever known. Perhaps we'll meet again some day, when the sleeping's over.

Ted Jenner: Love Songs of Ibykos (1997)

•

NZ Herald obituaries:

A service to celebrate Ted's life will be held at the All Souls Chapel, Purewa, 100 St Johns Road, Meadowbank on Tuesday 13 July at 1pm. No flowers by request please but donations to Forest and Bird would be welcome.

The service will also be livestreamed from 12.50pm to 2.20pm. If you wish to watch or download it, please write to r.jenner@auckland.ac.nz to receive a link.

•

Published on July 09, 2021 16:03

July 3, 2021

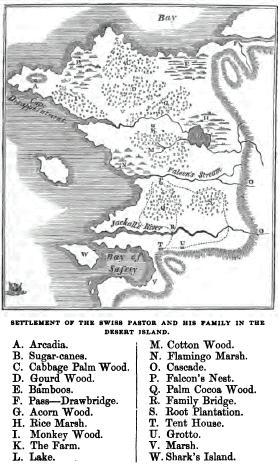

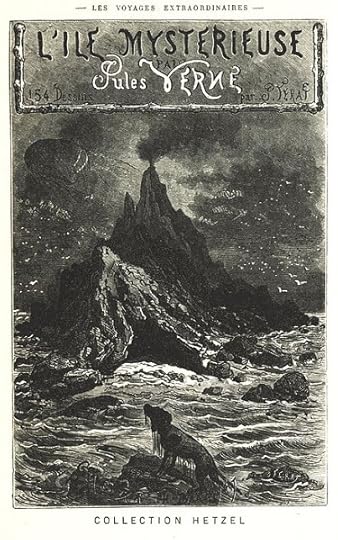

The Mysteries of Auckland: Jules Verne

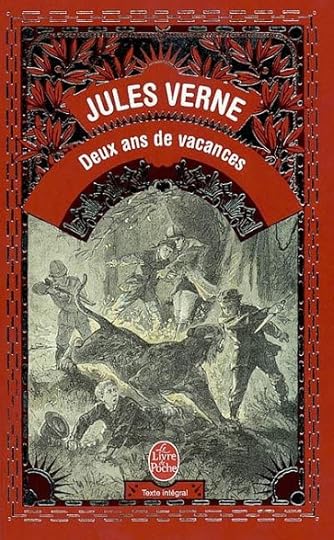

Jules Verne: Deux ans de vacances (1888)

As I remarked in my earlier post on Jules Verne, I recall being much entertained by his 1888 novel A Long Vacation, which I ran across in the Murrays Bay Intermediate School Library in the early 1970s.

I realise now that that Oxford University Press edition - beautifully illustrated though it was by Hungarian artist Victor G. Ambrus, who died earlier this year at the age of 85 - was even more severely abridged than is usual with Verne's books in English.

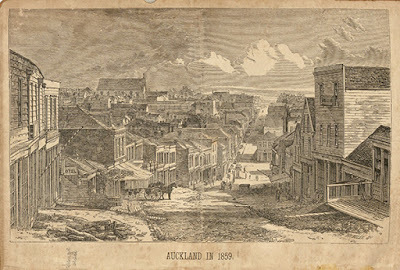

Given that part of the attraction seems to have been the fact that it was - at least in its opening chapters - set in my part of the world, Auckland. So I thought it might be interesting to compare Verne's original version with the picture of the city conveyed by his translator.

Jules Verne: A Long Vacation (1967)

À cette époque, la pension Chairman était l’une des plus estimées de la ville d’Auckland, capitale de la Nouvelle-Zélande, importante colonie anglaise du Pacifique. On y comptait une centaine d’élèves, appartenant aux meilleures familles du pays. Les Maoris, qui sont les indigènes de cet archipel, n’auraient pu y faire admettre leurs enfants pour lesquels, d’ailleurs, d’autres écoles étaient réservées.

Il n’y avait à la pension Chairman que de jeunes Anglais, Français, Américains, Allemands, fils des propriétaires, rentiers, négociants ou fonctionnaires du pays. Ils y recevaient une éducation très complète, identique à celle qui est donnée dans les établissements similaires du Royaume-Uni.- Jules Verne: Deux ans de vacances (1888), 58-81.

["At that time, the Chairman School was one of the most prestigious in the town of Auckland, capital of New Zealand, a major English colony in the Pacific. It included roughly a hundred students, belonging to the best families in the country. The Maoris, who are the native race of this archipelago, were not able to send their children there, although there were other schools reserved for them.

The Chairman School catered only to young English, French, American and German boys, sons of the property owners, businessmen, merchants or civil servants of the country. They received there a very complete education, identical to that provided by similar institutions in the United Kingdom."

- all translations are by me, unless noted otherwise.]

The passengers on the Sloughie were all pupils of the Chairman School, one of the best in Auckland, which was at that time the capital of New Zealand. The school numbered about a hundred pupils: English, French, American, and German. Its traditions and plan of study were those current in the educational institutions of England.- Jules Verne: A Long Vacation, trans. Olga Marx (1967), 19-24.

You'll notice at once how much franker Jules Verne's original is about the colour-bar between such British-style boarding schools as 'la pension Chairman' and the native schools reserved for the 'indigenous people of the country' than the 1960s English version dares to be.

This translation, by the industrious Olga Marx (1894-c.1980), better known for her versions of German writers such as Stefan George and Martin Buber, pares back the incidental detail so dear to Verne to convert his sprawling novel into a much tauter, more explicitly child-focussed adventure story.

•

Annex 1: Education in NZ in the 1860s

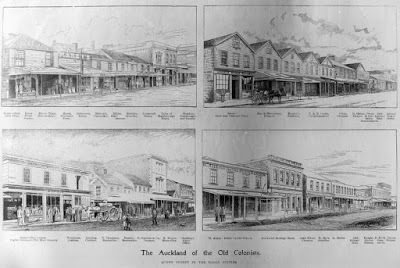

Auckland Libraries: The Auckland of the Old Colonists, Queen Street in the early 1860sTraditionally, Māori educated some children in whare wānanga (houses of learning). From 1816 missionaries also established schools for Māori to teach them literacy and practical skills. These became more numerous in the 1830s and 1840s. British settlers arriving in New Zealand were often less well-educated than Māori.

... Between 1852 and 1876 provincial governments gave grants to existing schools and established more. School systems were well-developed in parts of the South Island, but less so in the North Island. Meanwhile, central government supported a separate ‘native school’ system for Māori children. By 1870 there was a free basic education system in many places but only about half of all children between five and 15 were attending school.

Secondary schools were few, highly academic and charged fees. Early examples included Auckland Grammar School (1869), Wellington College (1867) and Otago Boys’ High School (1863). In 1871 Otago Girls’ High School, the first girls’ secondary school, opened. Some scholarships were offered, but generally only children from well-off families made it to secondary school, and many more boys did so than girls.- Te Ara / The Encyclopedia of New Zealand: Education from 1840 to 1918

•

And now, on with the story:

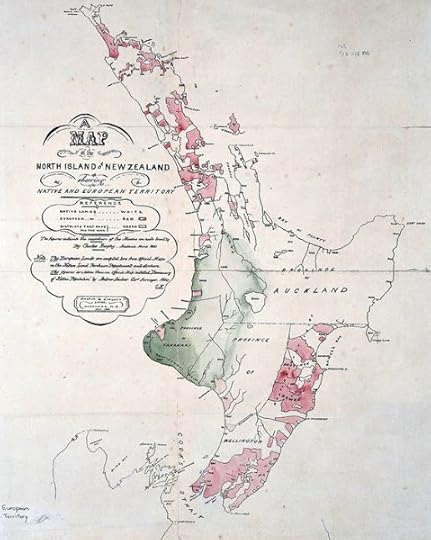

NZ: The North Island (1861)

L’archipel de la Nouvelle-Zélande se compose de deux îles principales: au nord, Ika-Na-Mawi ou Île du Poisson, au sud, Tawaï-Ponamou ou Terre du Jade-Vert. Séparées par le détroit de Cook, elles gisent entre le 34e et le 45e parallèle sud – position équivalente à celle qu’occupe, dans l’hémisphère boréal, la partie de l’Europe comprenant la France et le nord de l’Afrique. (Verne, 59)

["The archipelago of New Zealand consists of two principal islands: to the North, Ika-Na-Mawi [Te Ika-a-Māui] or Isle of the Fish, to the south, Tawaï-Ponamou [Te Waipounamu] or Land of Greenstone. Separated by Cook Strait, they lie between the 34th and the 45th parallel south - a postion equivalent to that occupied by the part of Europe including France and North Africa in the Northern Hemisphere."]

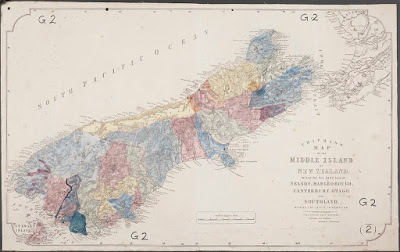

J. Wareham: NZ: The South Island (c. 1860-69)

L’île d’Ika-Na-Mawi, très déchiquetée dans sa partie méridionale, forme une sorte de trapèze irrégulier, qui se prolonge vers le nord-ouest, suivant une courbe terminée par le cap Van-Diemen. (Verne, 59)

["The island of Te Ika-a-Māui, very spread out in its middle parts, forms a kind of irregular trapezoid, which is prolonged towards the north-west, following a curve terminated by Cape Van Diemen."]

It [Auckland] was located on Ika-Na-Mawi, on of the two main islands of the New Zealand archipelago, separated from the other, Tawaï-Ponamou, by Cook Strait ... (Marx 19)

Jules Verne's life-long habit of cribbing information from guide-books and magazine articles serves him well here: he has a pretty good grasp of precisely what New Zealand looks like - on the map, at any rate.

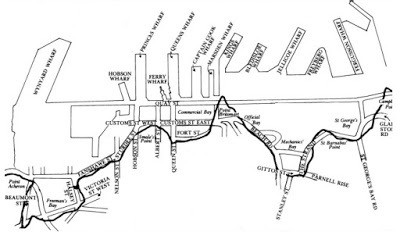

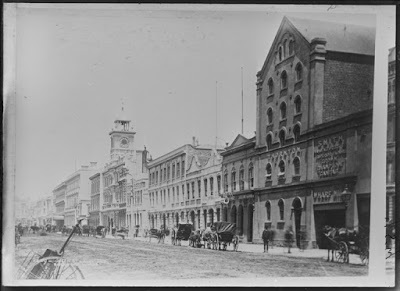

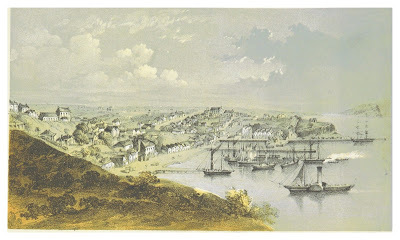

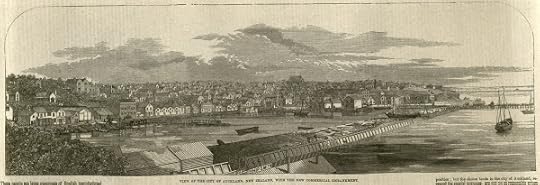

Special Collections, Auckland Library: Auckland (c. 1860)

C’est à peu près à la naissance de cette courbe, en un point où la presqu’île mesure seulement quelques milles, qu’est bâtie Auckland. La ville est donc située comme l’est Corinthe, en Grèce – ce qui lui a valu le nom de « Corinthe du Sud ». Elle possède deux ports ouverts, l’un à l’ouest,l’autre à l’est. Ce dernier, sur le golfe Hauraki, étant peu profond, il a fallu projeter quelques-uns de ces longs «piers», à la mode anglaise, où les navires de moyen tonnage peuvent venir accoster. Entre autres s’allonge le Commercial-pier, auquel aboutit Queen’s-street, l’une des principales rues de la cité.

C’est vers le milieu de cette rue que se trouvait la pension Chairman. (Verne, 59-60)

["It's almost at the beginning of this curve, at a point where the isthmus measures only a few miles wide, that Auckland is built. The city is thus situated like Corinth, in Greece - which has earned it the title of the 'Corinth of the South.' It has two ports, one opening to the west, the other to the east. This last, on the Hauraki Gulf, being shallow, it has proved necessary to project some long 'piers', in the English mode, where ships of deeper draft can tie up. Commercial Pier, one among several others, links up with Queen Street, one of the principal streets of the city.

Chairman school can be found towards the middle of this street."]

Ika-Na-Mawi had a west and an east port. The latter, on the Gulf of Hauraki, was shallow, but piers built out into the water in the British manner made it possible for vessels of medium tonnage to berth there. One of these piers, Commercial Pier, was at the end of Queen's street where Chairman School was situated. (Marx 19)

It's news to me that Auckland was ever referred to as "the Corinth of the South", but then that kind of information is one of the interesting by-products of reading old books. In any case, the translator leaves out much of that information as largely irrelevant to contemporary readers.

•

Annex 2: Auckland geography in the 1860s

Auckland Heritage: The original line of the waterfront (1850s)Auckland ... has, the luxury of two sheltered harbours to choose from: the Manukau on the west, with its lethal sandbar entrance and shallower channels, and the Waitemata on the east. Although the safer choice, the Waitemata waterfront, in its natural state, was a motley array of tidal beaches and mudflats which made loading and unloading the large sailing barques and brigantines a tricky and tedious business. The solution was a 1400′ (427m) long wharf jutting out into Commercial Bay, and once this was completed shops, warehouses, factories and hotels sprang up to receive, resell and redistribute the tons of cargo constantly being off-loaded there.

The area was soon the hub of Auckland’s commercial activity, and prime business real estate, but further inland was far less desirable. Where Aotea Square is now was once a swamp. Rainwater running downhill from Karangahape Ridge pooled in this hollow, before draining away to the harbour along a meandering trench known as the Waihorotiu Stream. Because the stream met the sea at a point near the new wharf, businesses soon sprang up alongside it, and the resulting caravan of wooden shops was declared to be Queen Street. Unfortunately the city had no provisions for sewage, and so Waihorotiu quickly became a low point hygienically, as well as geographically. Human waste and general garbage transformed the stream into a slow-moving cess pit, imparting an unsanitary odour over downtown Auckland and contributing to the spread of vermin, disease and death. In the 1880’s the stream was finally bricked in and paved over, and renamed Ligar’s Canal. Entombed beneath 21st century Queen St traffic and skyscrapers, it still courses through that same curious oval-section tunnel.

Auckland Heritage: Wharf Mill (1880s)

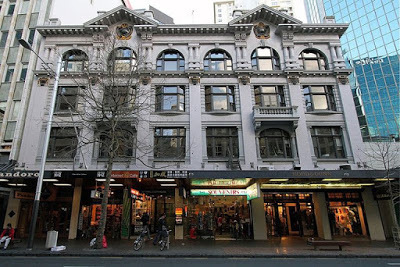

... But the waterfront was changing, or more correctly being changed. Plans were underway, beginning in the 1850’s, to establish commercial docks that could service any ships, and in greater numbers than a single wharf. The solution was to reclaim the harbour – fill in the foreshore and run the land right out past the shallows. To this end, work continued for over 100 years, but large sections were completed quite early on out of necessity.

Auckland Heritage: The Encom Building [Smeeton's Mill] (2016)

... Behind the façade – unchanged for over a hundred years – are the bones of a one hundred and fifty-five year old mill, once the largest and most prominent building in the area, now dwarfed by everything on the block. It marks the spot where Queen St once ended and the Waitemata Harbour began, now can no longer be seen from the waterfront. But it [Smeeton's] is still there, and thousands pass it daily.- Auckland Heritage: Queen Street's Oldest Building (2016)

•

Having set the scene, it's time for the actual adventure story to begin:

Hursthouse: Auckland Port (1857)

Or, le 15 février 1860, dans l’après-midi, il sortait du dit pensionnat une centaine de jeunes garçons, accompagnés de leurs parents, l’air gai, l’allure joyeuse – des oiseaux auxquels on vient d’ouvrir leur cage.

En effet, c’était le commencement des vacances. Deux mois d’indépendance, deux mois de liberté. Et, pour un certain nombre de ces élèves, il y avait aussi la perspective d’un voyage en mer, dont on s’entretenait depuis longtemps à la pension Chairman. Inutile d’ajouter quelle envie excitait ceux auxquels leur bonne fortune allait permettre de prendre passage à bord du yacht Sloughi, qui se préparait à visiter les côtes de la Nouvelle-Zélande dans une promenade de circumnavigation.

Ce joli schooner, frété par les parents des élèves, avait été disposé pour une campagne de six semaines. (Verne, 60-61)

["So, on the afternoon of the 15th of February, 1860, a hundred happy young boys, accompanied by their parents, burst out of the gates of the school with a joyful air - birds whose cage door has been flung open.

The long vacation had begun. Two months of independence, two months of liberty. And, for a certain number of these students, there was also the prospect of a sea voyage, as had long been the custom at the Chairman school. It's pointless to mention how much pleasure was felt by those whose good fortune would permit them to take passage on board the yacht Sloughi, which was preparing for a circumnavigation of both coasts of New Zealand.

This handsome schooner, rented by the parents of the students, had been victualled for a six weeks' voyage."]

On 14 February 1860, crowds of boys and their parents streamed out of the door. Vacation had begun, and they were going home for two months' of freedom and fun. A small number of boys had a special pleasure in store. They were going on a six weeks' cruise. (Marx 19)

Not a lot of information missing from Marx's concise summary there.

Illustrated London News: View of the City of Auckland, New Zealand, With the New Commercial Embankment (1860)

Il appartenait au père de l’un d’eux, M. William H. Garnett, ancien capitaine de la marine marchande, en qui l’on pouvait avoir toute confiance. Une souscription, répartie entre les diverses familles, devait couvrir les frais du voyage, qui s’effectuerait dans les meilleures conditions de sécurité et de confort. C’était là une grande joie pour ces jeunes garçons, et il eût été difficile de mieux employer quelques semaines de vacances. (Verne, 61)

["It belonged to one of their father's, Mr Wiliam H. Garnett, a retired Merchant Marine captain, in whom one could place complete confidence. A subscription, shared between various families, would cover the costs of the voyage, which would take place in the best circumstances of security and comfort. This would be a great pleasure for the young boys, and it would have been difficult for them to employ a few weeks of their vacation in a better manner."]

The father of one of them, Mr. William Garnett, a retired captain in the mercantile marine, owned a schooner, the Sloughie, and various families had joined to charter her to give their sons the opportunity to travel by sea in safety and comfort ... (Marx 19)

Circular Saw Line: Auckland Wharves (c.1860)

Le jour du départ avait été fixé au 15 février. En attendant, le Sloughi restait amarré par l’arrière à l’extrémité du Commercial-pier et, conséquemment, assez au large dans le port. L’équipage n’était pas à bord, lorsque, le 14 au soir, les jeunes passagers vinrent s’embarquer.

Le capitaine Garnett ne devait arriver qu’au moment de l’appareillage. Seuls, le maître et le mousse reçurent Gordon et ses camarades, – les hommes étant allés vider un dernier verre de wisky. Et même, après que tous furent installés et couchés, le maître crut pouvoir rejoindre son équipage dans un des cabarets du port, où il eut le tort impardonnable de s’attarder jusqu’à une heure avancée de la nuit. Quant au mousse, il s’était affalé dans le poste pour dormir. (Verne, 72-73)

["The day of departure had been fixed for the 15th of February. In expectation, the Sloughi was attached to the very end of the Commerical pier, and, consequently, very much in the middle of the port. The crew was not yet on board, when, on the evening of the 14th, the young passengers came down to embark.

Captain Garnett was not due to arrive until the moment of loading the cargo. Only the mate and the cabin boy received Gordon and his friends - the rest of crew had gone to empty a last glass of Whisky. And even then, after all of them had been received and put to bed, the mate thought he had time to join the rest of his crew in one of the port taverns, where he made the terrible mistake of lingering until a late hour of the night. As for the cabin boy, he had left his post to go to bed."]

The Sloughie was to leave on 15 February, and the boys boarded the night before. The Captain was not due to arrive until sailing-time, and the crew were having last drinks at one of the many bars near the port. Only the helmsman and Moko were aboard to receive the passengers and, after these had gone to bed, the helmsman decided to spend the evening in town at a cabaret ... As for Moko, when there was no more for him to do, he too, went to bed. (Marx 22)

Despite that obvious attempt at a Māori name, 'Moko', the cabin-boy is described throughout by Verne as a "nègre" - a Black African. Marx seems unsure how to describe him, and so leaves the question of his precise ethnicity moot. Certainly he is never treated as an equal by any of the white schoolboys.

New Zealand: A Hand-book for Emigrants: Auckland in 1859 (1860)

Que se passa-t-il alors? Très probablement, on ne devait jamais le savoir. Ce qui est certain, c’est que l’amarre du yacht fut détachée par négligence ou par malveillance ... À bord on ne s’aperçut de rien.

Une nuit noire enveloppait le port et le golfe Hauraki. Le vent de terre se faisait sentir avec force, et le schooner, pris en dessous par un courant de reflux qui portait au large, se mit à fuir vers la haute mer. (Verne, 73)

["What happened then? Very probably, we'll never know for sure. What's certain is that the cable attaching the yacht to the pier was let go by negligence or malice .. on board nobody noticed anything.

A black night enveloped the port and the Hauraki Gulf. The land wind was blowing hard, and the schooner, caught from behind by an adverse tide which carried it out, began to make its way out to the open sea."]

What happened then, no one knew. Only one thing was certain: either through negligence in the way her lines had been secured, or by some deliberate and malicious act the Sloughie broke loose from her piling. It was a starless night. The port and the Gulf of Hauraki lay in darkness. The wind freshened, and the schooner, caught in a strong current, was swept out to sea. (Marx 22)

Frederick Rice Stack: Auckland from Takapuna (1860)

Lorsque le mousse se réveilla, le Sloughi roulait comme s’il eût été bercé par une houle qu’on ne pouvait confondre avec le ressac habituel. Moko se hâta aussitôt de monter sur le pont... Le yacht était en dérive!

Aux cris du mousse, Gordon, Briant, Doniphan et quelques autres, se jetant à bas de leurs couchettes, s’élancèrent hors du capot. Vainement appelèrent-ils à leur aide! Ils n’apercevaient même plus une seule des lumières de la ville ou du port. Le schooner était déjà en plein golfe, à trois milles de la côte. (Verne, 73)

["When the cabin boy woke up, the Sloughi was was rolling as if it had been hit by a storm which could not be confused by the usual backwash. Moko hastened up on the bridge ... the yacht was floating free.

At the shouts of the cabin boy, Briant, Doniphan and a few others, jumping from their bunks, ran out of the cabin. They shouted out for help in vain. They could no longer see a single one of the lights of the port. The schooner was already out in the gulf, three miles from the coast"]

When Moko woke she was rolling and pitching. He knew at once that she would not behave like that in port, ran up on deck, and saw that she was loose.

At his cries Briant, Gordon, and Doniphan jumped out of bed and joined him on deck. They called for help. Their voices were drowned by the crash of waves and the roaring wind. Not a single light from the city was visible. The schooner was already three miles out from the coast. (Marx 22)

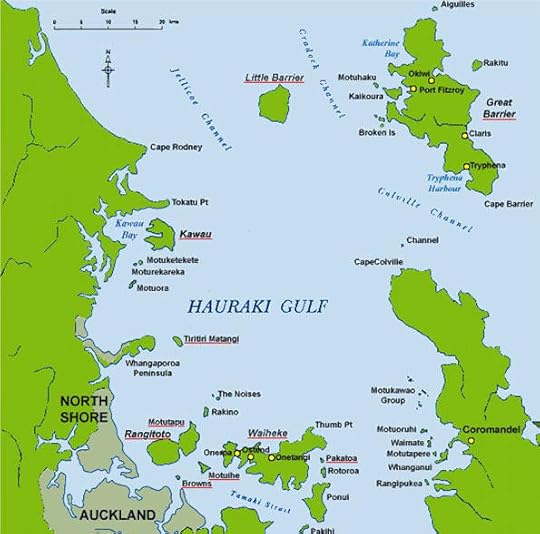

Hauraki Gulf Map

Tout d’abord, sur les conseils de Briant auquel se joignit le mousse, ces jeunes garçons essayèrent d’établir une voile, afin de revenir au port en courant une bordée. Mais, trop lourde pour pouvoir être orientée convenablement, cette voile n’eut d’autre effet que de les entraîner plus loin par la prise qu’elle donnait au vent d’ouest. Le Sloughi doubla le cap Colville, franchit le détroit qui le sépare de l’Île de la Grande-Barrière, et se trouva bientôt à plusieurs milles de la Nouvelle-Zélande. (Verne, 74)

["Right away, at the suggestion of Briant, seconded by the cabin boy, these young boys tried to hoist a sail, in order to return to port in the hopes of a rescue, But, too heavy to be hoisted comfortably, this sail had no effect except to take them further out, as a result of the west wind which had sprung up. The Sloughi rounded Cape Colville, threaded the strait which separates it from Great Barrier island, and soon found itself several miles from New Zealand."]

At Briant's sugggestion the boys, together with Moko, tried to hoist a sail in order to get back to port. But they were too inexperienced and accomplished the opposite of what they had set out to do. The Sloughie was carried farther and farther out to sea. She rounded Cape Colville and was soon many miles away from New Zealand. (Marx 22)

This is an interesting description. I find it hard to believe that any boat could be blown out of Auckland harbour all the way past Cape Colville without encountering one of the myriad islands of the Hauraki Gulf: - Waiheke, for instance - but I suppose some allowance must be made for poetic licence.

James Edward Buttersworth (1817-1894): Schooner in Stormy Seas

On comprend la gravité d’une pareille situation. Briant et ses camarades ne pouvaient plus espérer aucun secours de terre. Au cas où quelque navire du port se mettrait à leur recherche, plusieurs heures se passeraient avant qu’il eût pu les rejoindre, étant même admis qu’il fut possible de retrouver le schooner au milieu de cette profonde obscurité. Et d’ailleurs, le jour venu, comment apercevrait-on un si petit bâtiment, perdu sur la haute mer? Quant à se tirer d’affaire par leurs seuls efforts, comment ces enfants y parviendraient-ils? (Verne, 74)

["The seriousness of the situation was obvious. Briant and his companions could expect no more help from the shore. Even if a ship from the port set out in search of them, several hours would pass before it could catch up with them, even if it should prove possible to find the schooner in the midst of this profound darkness. And then, when day came, how would one be able to find so small a ship, lost on the high seas? As for getting out of trouble by their own efforts, how could these children achieve that?"]

Briant and his companions realized that no aid could come to them from land. A passing vessel was their only hope. But would such a vessel see a small schooner in the dark? (Marx 22)

Jules Verne: Deux ans de vacances (1888)

À Auckland, lorsque la disparition du Sloughi eut été constatée dans la nuit même du 14 au 15 février, on prévint le capitaine Garnett et les familles de ces malheureux enfants. Inutile d’insister sur l’effet qu’un tel événement produisit dans la ville, où la consternation fut générale.

Mais, si son amarre s’était détachée ou rompue, peut-être la dérive n’avait-elle pas rejeté le schooner au large du golfe ? Peut-être serait-il possible de le retrouver, bien que le vent d’ouest, qui prenait de la force, fût de nature à donner les plus douloureuses inquiétudes ?

Aussi, sans perdre un instant, le directeur du port prit-il ses mesures pour venir au secours du yacht. Deux petits vapeurs allèrent porter leurs recherches sur un espace de plusieurs milles en dehors du golfe Hauraki. Pendant la nuit entière, ils parcoururent ces parages, où la mer commençait à devenir très dure. Et, le jour venu, quand ils rentrèrent, ce fut pour enlever tout espoir aux familles frappées par cette épouvantable catastrophe.

En effet, s’ils n’avaient pas retrouvé le Sloughi, ces vapeurs en avaient du moins recueilli les épaves. C’étaient les débris du couronnement, tombés à la mer, après cette collision avec le steamer péruvien Quito – collision dont ce navire n’avait pas même eu connaissance.

Sur ces débris se lisaient encore trois ou quatre lettres du nom de Sloughi. Il parut donc certain que le yacht avait dû être démoli par quelque coup de mer, et que, par suite de cet accident, il s’était perdu corps et biens à une douzaine de milles au large de la Nouvelle-Zélande. (Verne, 79-81)

["In Auckland, after the disappearance of the schooner had been noticed on the night of the 14th-15th of February, Captain Garnett and the various families of these unfortunate children were informed. It's unnecessary to stress what effect such an announcement had on the town, where it caused general consternation.

But, if the cable had been cut or broken, perhaps the ebb tide would have left the ship in the midst of the gulf? In which case, it might still be possible to find them, even though the west wind, which was gathering force, gave rise to much disquiet.

So, without losing a moment, the port director took measures to go to the assitance of the yacht. Two small steam tugs went out to search over a space of many miles around the Hauraki Gulf. Throughout the whole night, they continued their traverses, until the sea began to become very rough. And, when day came, and they returned, it was to remove all hope from the families struck by this terrible catastrophe.

In effect, if they hadn't found the Sloughi, these tugs had at least discovered a few traces of it, It was the debris from the bow, fallen into the sea, after that collision with the Peruvian steamer Quito - a collision which the ship in question had not even noticed.