Eve Lazarus's Blog: Every Place has a Story, page 34

July 21, 2018

Captain Pybus and Vancouver’s St. Clair Hotel

A little while ago I was having lunch with Tom Carter and Maurice Guibord at the newly renovated Railway Club. Afterwards, we were walking along Richards Street and Tom gave us a tour of the St. Clair Hotel-Hostel.

The Blushing Boutique is on the ground floor and a set of very steep stairs takes you up to the Hostel. The whole interior is designed in a nautical theme, which I guess isn’t surprising since it was designed by architect Samuel Birds for Captain Henry Pybus.

The Blushing Boutique is on the ground floor and a set of very steep stairs takes you up to the Hostel. The whole interior is designed in a nautical theme, which I guess isn’t surprising since it was designed by architect Samuel Birds for Captain Henry Pybus.

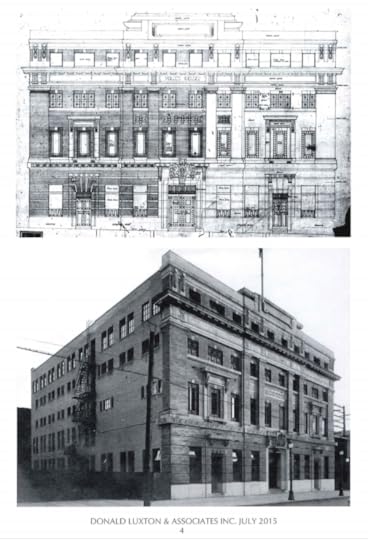

The four-storey brick building at 577 Richards Street was finished in 1911 and initially known as the Dunsmuir Rooms until 1930 when it became the St Clair Rooms. It sits next door to BC Stamp Works, which was built in 1895 as a boarding house.

When Pybus was building his commercial block, it looks like the owner at BC Stamp Works (583 Richards) took the opportunity to have the first floor lifted so a retail store or offices could be added—one of Vancouver’s few remaining buried houses.

Captain Henry Pybus in 1909. Courtesy CVA Port P1645

Captain Henry Pybus in 1909. Courtesy CVA Port P1645Pybus captained the Empress of China, and later and the Empress of Japan—a white clipper-ship, which with Pybus at the helm, held the record for crossing the Pacific for over 20 years. Pybus retired in 1911 at age 60. The Empress of Japan was decommissioned in 1922 and left to rot in Vancouver Harbour. Fortunately, the editor of the Province heard she was to be scrapped and had his staff rescue her dragon figurehead, donated it to the city, and it sat in Stanley Park until 1960 when it was replaced with a fiberglass replica. (The original was restored and remains with the Vancouver Maritime Museum).

The dragon figurehead from the Empress of Japan in 1936. Courtesy CVA Bo N83.1

The dragon figurehead from the Empress of Japan in 1936. Courtesy CVA Bo N83.1According to Michael Kluckner’s Vanishing Vancouver, the South African born Pybus, fancied himself as a speculator and owned a bunch of property around the city—including a pre-fab Model J BC Mills house that sat at East 1st and Lonsdale from 1908 until 1995 when it was moved—and remains at—Lynn Headwaters Regional Park.

Pybus’s BC Mills House now at Lynn Headwaters

Pybus’s BC Mills House now at Lynn HeadwatersPybus lost most of his properties in the land crash of 1913/14. He spent the rest of his long life in the West End and died in 1938. Fifty years later, his grandson, Henry Pybus Bell-Irving became the 23rd Lieutenant Governor of BC

What’s surprising, is how little change there has been on the Richards Street block. The retail space below the St. Clair started as a storefront for the United Typewriter Company, became the Vancouver Auction Rooms in the ‘20s, and by 1930 was the headquarters for Pluto Office Furniture. BC Stamp Works, the St. Clair and the office furniture business were still co-existing 25 years later, and not much has changed in the years since.

Top photo: The St. Clair Hotel and BC Stamp Works on the 500-block Richards Street in 1985. Courtesy CVA 790-1797

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

July 14, 2018

Rhona Duncan (1959-1976)

Rhona Duncan died years before I moved to North Vancouver, but whenever I drive up Larson and cross Bewicke I think of her. And, 42 years later, her murder still haunts my friends and neighbours who either knew her or of her. This is an excerpt from Cold Case Vancouver.

Rhona Duncan, her boyfriend Shawn Mapoles, and their friends Owen Parry and Marion Bogues left the party on East Queens Road in North Vancouver in the early hours of July 17, 1976. It was a warm summer night and they took their time walking in the direction of their homes. The teens, who were to enter Grade 12 at Carson Graham in the fall, stopped at the municipal hall on West Queens. Owen and Shawn lived up the hill, and Rhona and Marion lived in the Hamilton area. The girls wanted to be by themselves to talk about the night; it was an easy walk down Jones Avenue.

Rhona and Marion stopped and talked for a while and then parted company near Marion’s home at the corner of Larson Road and Wolfe Avenue. Rhona disappeared into the darkness of Larson Road, turned south on Bewicke Avenue, and was at the intersection at West 15th, the quiet residential street where she lived, when someone stopped her. She was in sight of the safety of her home.

Rhona and Marion stopped and talked for a while and then parted company near Marion’s home at the corner of Larson Road and Wolfe Avenue. Rhona disappeared into the darkness of Larson Road, turned south on Bewicke Avenue, and was at the intersection at West 15th, the quiet residential street where she lived, when someone stopped her. She was in sight of the safety of her home.

By 4:00 a.m. Rhona, the oldest of four girls, was dead. She had been raped and strangled.

Shawn found out about his girlfriend’s murder the next day from one of his friends. Later that morning the RCMP arrived, bagged his clothes and interviewed him. He voluntarily took a polygraph, and when DNA came on the scene two decades later, he volunteered his as well.

Shawn, who still lives in North Vancouver, told me: “I felt guilty. Normally, I would walk a woman home, but Rhona didn’t want me to walk her home that night.”

Police asked Shawn if he remembered anyone paying a lot of attention to Rhona at the party. He told them that while he knew a lot of the kids there that night, he couldn’t remember anything that seemed strange or out of place. “We were just getting to know each other, so I was focusing my attention on Rhona, not on my surroundings.”

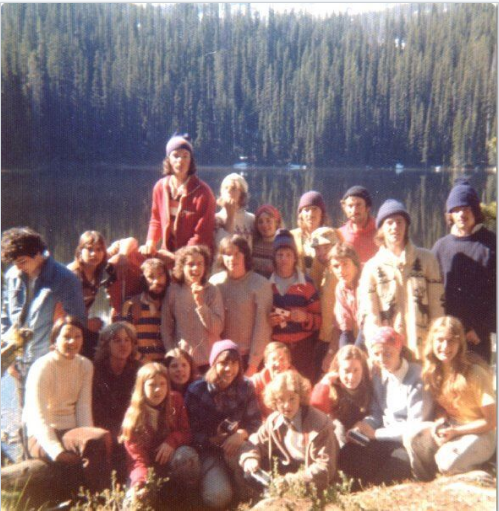

Carson Graham Students in 1976. Rhona front row left. Photo courtesy Gord Curl

Carson Graham Students in 1976. Rhona front row left. Photo courtesy Gord CurlOn July 22, five days after the murder, the RCMP announced that they had formed a special squad to check for similarities in the unsolved sex slayings of at least 12 women since January 1975.

Police say they’ve interviewed hundreds of witnesses and suspects in the Rhona Duncan case, performed polygraphs on the higher priority suspects, and tested DNA. The case remains inside eight boxes of evidence in the cold file room, where every now and then it’s taken out, dusted off, and re-examined.

Duncan home on West 15th. Eve Lazarus photo

Duncan home on West 15th. Eve Lazarus photoFrom the RCMP website:

“A list of 172 males consisting of all of Duncan’s acquaintances and all of the suspects on the file was compiled. Investigators have obtained DNA samples from the vast majority of the subjects on the list and compared them with the suspect DNA with negative results. All of the higher priority subjects on the list have been eliminated. Many of the remaining subjects are either deceased or have not been located.”

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

July 7, 2018

The History Store

Chris Wright wants to start a cultural movement around history. A former location scout for the film industry and a treasure hunter with a metal detector, he is the owner of The History Store in Mount Pleasant.

Chris Wright wants to start a cultural movement around history. A former location scout for the film industry and a treasure hunter with a metal detector, he is the owner of The History Store in Mount Pleasant.

The store has been there almost a year, but unless you have an appointment, it’s only open from noon to 4:00 pm. on Saturdays. And, trust me that’s not long enough.

Chris specializes in photos, negatives, slides and postcards. But he also has movie size posters, maps, blueprints, letters—even a section of the Lions Gate Bridge.

A piece from the Lions Gate Bridge after the late 1990s retrofit. Eve Lazarus photo

A piece from the Lions Gate Bridge after the late 1990s retrofit. Eve Lazarus photoThere are boxes offering photos of animals, costumes and cars for $3. For $2 you can pick up a Christmas postcard or a photo of early New Westminster.

Chris tells me he has 400 pounds of negatives to go through and has looked at more than 30,000 slides this past week. He buys them in bulk and pays 10 cents per slide. It’s worth it he says, every now and then one slide will net him $400 or more. Negatives are the future of the business. He has glass negatives dating back to 1900 and his intention is to develop the negatives, blow them up and sell them with the photo—so you know you have a one-of-a-kind photo hanging on your wall.

Vic Steele lives in Coquitlam and spends most Saturday afternoons at the store. He’s a military collector and says his best find to date is a Royal Air Force tunic that belonged to a pilot who flew in the Battle of Britain. The pilot survived the war and his uniform is now displayed in Vic’s man cave.

I knew this was a serious store when Neil Whaley walked in. Chris tells him that he’s just come into 18 boxes of film and television photos. Like any collector (or writer for that matter) there’s nothing more exciting than getting first crack at something archival.

When I asked Neil what he thought was the coolest thing in the store, he pointed to a poster for the 1922 film The Radio King, considered a “lost film,” likely destroyed in the fire at Universal Studios.

The poster was found under an oak floor during a home renovation in Kerrisdale ten years ago. It will find a home at North Vancouver’s Polygon Gallery.

Neil tells me that his favourite History Store find is a series of photos of the Black Gospel Rescue with Rev. Melinda Thorne. According to James Johnstone’s Blog, Thorne led the Mizpah African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church between 1966 and 1971 at 823 Jackson Street.

The History Store is addictive. I found some great aerial photos of Vancouver by George Allen taken in the 1980s.

Chris says he recently donated some George Nye photos to North Vancouver Museum and Archives. “I think we can do better for history by sharing it,” he says. “If you share more than you take, it rains down on you.”

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

June 30, 2018

Our Missing Heritage: Vancouver’s First Hospital

Last week, Michael Kluckner and I were over at Tom Carter’s studio looking out his seventh storey window onto the EasyPark—a cavernous concrete lot that fronts West Pender and takes up the entire city block from Cambie to Beatty Streets.

Last week, Michael Kluckner and I were over at Tom Carter’s studio looking out his seventh storey window onto the EasyPark—a cavernous concrete lot that fronts West Pender and takes up the entire city block from Cambie to Beatty Streets.

In 2013, Michael had the dubious honour (my words) of presenting the parking lot with a heritage plaque on behalf of Places That Matter.

He wasn’t recognizing the parking lot of course, but the buildings that were once Vancouver’s first city hospital and included a men’s surgical ward, a maternity ward, a tuberculosis ward, and the city morgue which faced Beatty Street.

Pender and Beatty Street in 1939. Note the Sun Tower left of frame and former Hospital buildings behind. Courtesy Tom Carter

Pender and Beatty Street in 1939. Note the Sun Tower left of frame and former Hospital buildings behind. Courtesy Tom CarterIf we’d been looking out Tom’s window back in 1912, we would have had a great view of the courthouse in what’s now Victory Square, the shiny new Dominion Building, and the former city hospital, built in 1888, which according to Michael’s Vancouver: The Way it Was consisted of a compound of brick buildings with wooden balconies set back from the street, flower gardens and a picket fence.

Aerial view of Larwill Park construction, the Sun Tower and the Vancouver hospital buildings. Note the Central School bottom right of frame demolished in 1946. Courtesy Tom Carter

Aerial view of Larwill Park construction, the Sun Tower and the Vancouver hospital buildings. Note the Central School bottom right of frame demolished in 1946. Courtesy Tom CarterBy the turn of the century, the 50-bed hospital was too small for Vancouver’s growing population and a new hospital was built in Fairview in 1906 which became the Vancouver General Hospital as we know it now.

The first city hospital was repurposed into the headquarters for McGill University College (BC). And that’s another interesting story.

A former hospital building in 1949, shortly before it was turned into a parking lot. Courtesy CVA 447.61

A former hospital building in 1949, shortly before it was turned into a parking lot. Courtesy CVA 447.61In 1899, Vancouver High School joined forces with McGill to offer first year arts courses. Six years later the school moved to fancy new digs at Oak and 12th Avenue (later renamed King Edward High School), and McGill moved into the former hospital buildings. McGill stayed in the old hospital until 1911 and faded from the landscape after UBC opened in 1915.

The tuberculosis ward, courtesy Tom Carter

The tuberculosis ward, courtesy Tom CarterJFCB Vance from Blood, Sweat, and Fear had a lab in there from around 1912 when the police station on East Cordova was demolished until the new station opened in 1914. According to City Directories, a former hospital building became the “old people’s home” until 1915 when Social Services (the City Relief and Employment Department) moved in and stayed until the late ’40s.

And just like that it’s a parking lot. 1951 photo courtesy Tom Carter

And just like that it’s a parking lot. 1951 photo courtesy Tom CarterThe city hospital buildings were gone by 1950 and now all that’s left is a plaque affixed to a parking lot.

Just look what we did with the space! Beatty and West Pender, Google maps 2018

Just look what we did with the space! Beatty and West Pender, Google maps 2018Top photo: The first Vancouver Hospital in 1902. Courtesy CVA Bu P369

With thanks to Tom Carter for finding all these great photos and to Places That Matter for all the work that they do.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

June 23, 2018

Kits Point and the Summer of ‘23

Michael Kluckner is a writer and artist with a list of books that includes Vanishing Vancouver and Toshiko. His most recent book is a graphic biography called Julia. He is the president of the Vancouver Historical Society and chair of the city’s Heritage Commission.

Summertime, traffic jams, and the changing city are caught in a set of previously unpublished photos taken from the front porch of a Kits Point house in 1923.

In 1923, Ogden was a corduroy road. The parkland in the background at Ogden and Maple Street which had been popular as an informal camping area in the early 1900s, was bought for the City by retired jeweller Harvey Hadden in 1928. I was given this photograph (above) a dozen years ago by Anne Terriss, who lived with her architect husband Kenneth at 1970 Ogden Avenue, and published it in Vancouver Remembered in 2006.

I was intrigued by the number of families who arrived by car rather than by the streetcar that serviced the beach from a line a few blocks away near Cornwall Avenue. Also, I noted the number of cars parked in the sun with torn-up brush covering their tires to stop the rubber from cracking in the heat.

As it turned out, there were two other photographs taken in 1923 from the front porch of 1982 Ogden, probably by a member of the Bell family. (Photos courtesy of Shirley Wheatcroft, who lives there today.) The photo (below) shows the view northward of the West End and its English Bay waterfront with the Sylvia Hotel visible near the left edge.

Anne and Ken Terriss were long-time members of the Kitsilano community and were part of the generation of volunteers and patrons who created the theatre and arts scene in Vancouver in the 1950s and 1960s. Anne was one of the handful of people in Kitsilano in the 1960s and early 1970s with a good camera and an eye for photographing the passing parade, and freely gave her photographs for publication to the Around Kitsilano community newspaper and, later, to me.

Visible on the right-hand side of the above photo, are porch posts from a cottage, actually one of three BC Mills Model J prefab cottages that faced Yew Street. At the time, this corner was part of a dense little beach community—on a 100-foot-square lot, there stood the apartment building, the three BC Mills cottages facing Yew Street, plus two more that faced onto the lane! Anne recalled that a private lending library charging 10 cents a book operated from one of the cottages.

The strategic corner tenant of the apartment building has been a Starbucks for many recent years.

Courtesy Hal Kalman, Exploring Vancouver, 1978 (p. 198)

Courtesy Hal Kalman, Exploring Vancouver, 1978 (p. 198)Ken Terriss was an architect with a deft touch who made most of his living working independently with small residential commissions. He designed his own house on Ogden in 1971 and fitted it into the vintage streetscape. In Exploring Vancouver, Hal Kalman described the house as “exuberantly imaginative” and noted that the “angle of the plan exploits the spectacular mountain views.” “Despite the house’s explicit modernity,” he wrote, “it respects the size and scale of its older neighbours.” The house next door in the photo was one of the five “show homes” built by the CPR in 1909 to entice settlers to the area.

Ken and Anne’s house was torn down and replaced by an even more modern house—the kind of glassy box that has become the current style du jour on Kits Point, which is apparently the most expensive “detached house” real estate per square foot in Vancouver.

For other guest blogs by Michael Kluckner see:

Saving History: the Rec Room and the Player Piano

Vancouver’s Buried Houses

June 15, 2018

West Coast Modern Architecture

There is a chapter in Sensational Vancouver called West Coast Modern which explains the connections between artists and architects and the West Coast Modern movement in Vancouver.

Last week I wrote about Selwyn Pullan’s photography exhibition currently on display at the West Vancouver Museum. I focused on his shots of West Coast Modern houses now almost all obliterated from the landscape.

But Selwyn also did a lot of commercial photography and one of his largest clients was Thompson Berwick Pratt, the architecture firm headed up by Ned Pratt who hired and mentored some of our most influential West Coast Modern architects. Arthur Erickson, Ron Thom, Paul Merrick, Barry Downs and Fred Hollingsworth all cut their teeth at TBP, and BC Binning consulted on much of the art that went along with the buildings.

BC Electric from the back cover of Sensational Vancouver. Courtesy Selwyn Pullan, 1957.

BC Electric from the back cover of Sensational Vancouver. Courtesy Selwyn Pullan, 1957.Ned Pratt’s crowning achievement was winning the commission to design the BC Electric building on Burrard Street—a game changer in the early 1950s. While the building is still there, now dwarfed by glass towers and repurposed into the Electra—a few of the firm’s other creations are long gone.

There was the Clarke Simpkins car dealership built in 1963 on West Georgia that demonstrated Vancouver’s growing fascination with neon.

CKWX (News 1130) building designed at 1275 Burrard in 1956, demolished 1989. Replaced by The Ellington. Selwyn Pullan photo 1956

CKWX (News 1130) building designed at 1275 Burrard in 1956, demolished 1989. Replaced by The Ellington. Selwyn Pullan photo 1956Our love for neon also showed up in the former CKWX headquarters at 1275 Burrard Street. According to the Modern Movement Architecture in BC (MOMO) the building won the Massey Silver Medal in 1958. “This skylit concrete bunker was home to one of Vancouver’s major radio stations until the late 1980s. The glassed-in entrance showcased wall mosaics by BC Binning, their blue-gray tile patterns symbolizing the electronic gathering and transmission of information.”

The building is long gone, replaced by a 20-storey condo building called The Ellington in 1990.

The Ritz Hotel at 1040 West Georgia was originally a 1912 apartment building. It was remodeled into a hotel when this photo was taken in 1956 and demolished in 1982. It was replaced by the 22-storey hideous gold Grosvenor building. Selwyn Pullan photo

The Ritz Hotel at 1040 West Georgia was originally a 1912 apartment building. It was remodeled into a hotel when this photo was taken in 1956 and demolished in 1982. It was replaced by the 22-storey hideous gold Grosvenor building. Selwyn Pullan photoI wonder what happened to the murals?

The Exhibition runs until July 14.

Top photo: Clarke Simpkins Dealership, 1345 West Georgia. Built 1963, demolished 1993. Selwyn Pullan photo, 1963.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus

June 9, 2018

Selwyn Pullan Photography: What’s Lost

I finally got a chance to drop by the West Vancouver Museum yesterday to check out the latest exhibition on the photography of Selwyn Pullan. Assistant curator Kiriko Watanabe has done an amazing job, not only pulling out some of Selwyn’s most interesting work, but also displaying the cameras that he used to shoot them with.

I finally got a chance to drop by the West Vancouver Museum yesterday to check out the latest exhibition on the photography of Selwyn Pullan. Assistant curator Kiriko Watanabe has done an amazing job, not only pulling out some of Selwyn’s most interesting work, but also displaying the cameras that he used to shoot them with.

After serving in the Canadian Navy during the Second World War, Selwyn moved to Los Angeles to study photography at the Art Center School in Los Angeles where Ansel Adams taught. He worked as a news photographer at the Halifax Chronicle, and when he moved back to Vancouver in 1950 he found a new movement of artists and architects who were reinventing the house.

Selwyn reinvented architectural photography.

When he found that the Speed Graphic was inadequate for the movement needed for photographing West Coast Modern architecture, Selwyn built his own camera. Eve Lazarus photo

When he found that the Speed Graphic was inadequate for the movement needed for photographing West Coast Modern architecture, Selwyn built his own camera. Eve Lazarus photoSeveral years ago, I asked him how he went about taking these photos. “I just look at the house and photograph it,” he said. “It’s a journalistic assignment not a photographic one.”

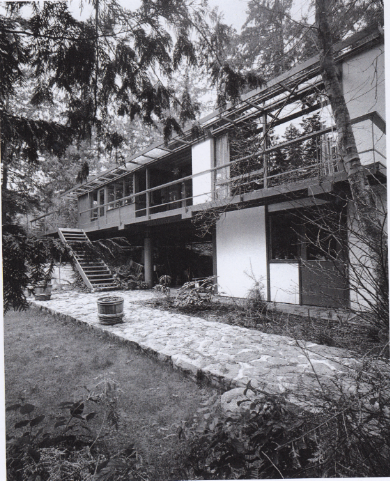

Shadbolt residence, Burnaby.. Architect Doug Shadbolt, owners & designers Jack and Doris Shadolt. Built 1950, Demolished 2004

Shadbolt residence, Burnaby.. Architect Doug Shadbolt, owners & designers Jack and Doris Shadolt. Built 1950, Demolished 2004Many of his photos were taken in the 1950s and ‘60s. They evoke a sense of time, optimism for the future, and perhaps even a new way of thinking. He intuitively understood the work of the architects he photographed, emphasizing light and space and often pulling in the homeowners and their children to show how the architectural and interior design fit with family life.

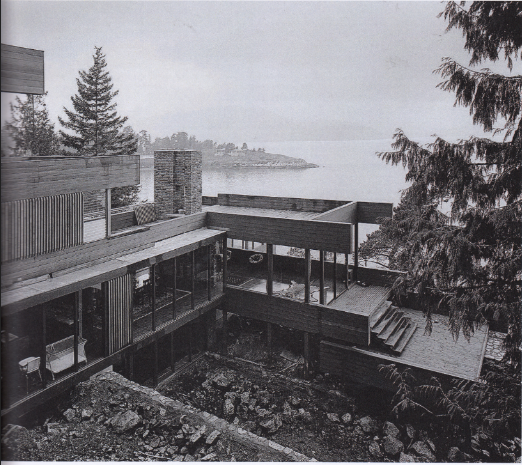

Home of artist Gordon Smith, West Vancouver. Erickson and Massey architects. Built 1954. Demolished 2010

Home of artist Gordon Smith, West Vancouver. Erickson and Massey architects. Built 1954. Demolished 2010His pictures show Gordon Smith painting in the studio designed by Arthur Erickson; there’s a young Erickson lounging in his own adapted garage; and Jack Shadbolt is photographed painting in his Burnaby studio. His stunning portraits of artists and sculptors include E.J. Hughes, George Norris, Bill Reid and Roy Kiyooka.

Phillips residence, West Vancouver. Barry Downs Architect. Completed 1957, demolished 2006.

Phillips residence, West Vancouver. Barry Downs Architect. Completed 1957, demolished 2006.While the photos in the exhibition showcase Selwyn’s work, they are also carefully selected to show our missing heritage—building after building both residential and commercial that no longer exist. The loss is particularly apparent in West Coast Modern.

Go see this exhibition—it runs until July 14. There’s a guest talk by Donald Luxton on Saturday June 30 at 2:00 p.m. which will be well worth your time.

Graham residence, West Vancouver. Erickson & Massey architects. Built 1963, demolished 2007

Graham residence, West Vancouver. Erickson & Massey architects. Built 1963, demolished 2007Selwyn died last September, after spending 65 years in his North Vancouver house, where he worked in his Fred Hollingsworth-designed studio, and where he parked his jaguar under a Hollingsworth-designed carport.

Fred Hollingsworth designed Selwyn’s North Vancouver home/studio in 1960.

Fred Hollingsworth designed Selwyn’s North Vancouver home/studio in 1960.Top photo caption: Birks Building. Architect Somervell and Putnam. Built 1912, demolished 1974.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

June 2, 2018

How the Museum of Exotic World became Main Street’s Neptoon Records

I had the pleasure of visiting Neptoon Records on Main Street for the first time last week. The place was packed with browsers, most of them young. The second thing I noticed was the sheer number of records—thousands of them everywhere you look. They are filed neatly in the store, stacked down the stairs, and they fill the basement. Owner and founder Rob Frith, tells me that he had to stop renting one of the upstairs rooms so he could use it for storage.

Neptoon’s Rob Frith in the basement of his Main Street store. Eve Lazarus photo.

Neptoon’s Rob Frith in the basement of his Main Street store. Eve Lazarus photo.You can pick up a used album for as little as $1 or pay up to $1,500 for a 1960s sealed copy from a Canadian band called the Haunted. Most things will set you back between $5 and $25.

Rob bought the building around 2000 and moved his stock from the Fraser Street store that he started in 1981. At that time, he was in construction, the economy crashed, and when he was casting around for things to do, he knew he didn’t want to work for anyone, and he liked collecting vinyl. “One day I thought maybe I should open a record store.”

Guessing the number of records at Neptoon’s is like guessing the number of jellybeans in the jar

Guessing the number of records at Neptoon’s is like guessing the number of jellybeans in the jar“People who collect are obsessive,” says Rob. He knows because he’s a collector—records, posters, menus, old contracts, buttons, photographs and concert ticket stubs.

His store is now the oldest independent record store in Vancouver. It’s survived CDs, and iTunes and Spotify.

“We hung on long enough that there was a resurgence almost 20 years ago,” says Rob. “It’s gone leaps and bounds since then.”

It started when kids wanted to be deejays and increased when they found mum and dad’s turntable and old records in the basement. Now music labels are releasing new pressings and reissues on vinyl and that’s created a whole new market.

The building also comes with a great history. Rob, it turns out, isn’t the only owner who liked collecting.

3561 Main Street

3561 Main StreetThe storefront first pops up in the city directories in 1951 owned by Harold and Barbara Morgan. The Morgans lived upstairs and ran a spray paint rental business downstairs. Every year since the ‘40s the couple travelled to a different place—New Guinea, Borneo, Africa, Guatemala—and brought back souvenirs. When they retired in 1989, they turned the store into the (free) Museum of Exotic World packed it full of collectables—a stuffed alligator, butterflies, a shrunken head and hundreds of photographs—and opened it for a few hours each day.

There’s a suite upstairs that’s straight out of the 1950s with brand new appliances from that decade including a clothes dryer and a stove that was never used—it still had the instructions inside. Rob has rented it out to a TV show.

When the Morgans died they bequeathed their vast collection and their ashes to Alexander Lamb’s antique store at 3271 Main Street. Which as you might expect, will be the subject of a future blog.

Main Street looking North from 26th, 1920s. Courtesy CVA LGN503

Main Street looking North from 26th, 1920s. Courtesy CVA LGN503© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

May 26, 2018

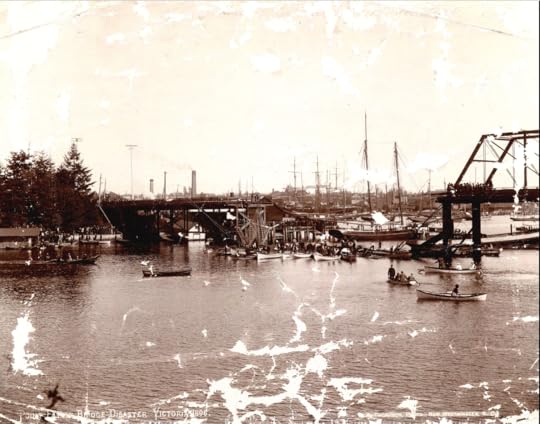

The Point Ellice Bridge Disaster – May 26, 1896

On May 26, 1896, 143 people crammed onto Streetcar No. 16 to cross the Point Ellice Bridge. It was Queen Victoria’s birthday and they were on their way to attend the celebrations at Macaulay Point Park in Esquimalt. They never made it.

The middle span of the bridge collapsed under the weight and the streetcar plunged into the Upper Harbour landing on its right side. Fifty-five people were killed that day, most of whom had been on the streetcar, but also some who were just on the bridge.

Point Ellice Bridge disaster aftermath, May 29, 1896. Courtesy BC Archives C-06135

Point Ellice Bridge disaster aftermath, May 29, 1896. Courtesy BC Archives C-06135The bodies of the victims were laid out on the lawn of the Point Ellice house and those of its neighbours.

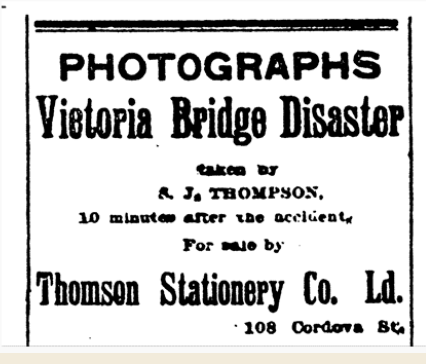

New Westminster photographer Stephen Joseph Thompson, just happened to be in Victoria that day and he had his camera with him. He snapped a photo and quickly realized that he had a business opportunity and ran an ad in the Vancouver News-Advertiser the next day. According to the British Columbia Encyclopedia the Point Ellice Bridge Disaster was the worst accident in Canadian transit history. The cause was attributed to poor bridge maintenance, an overcrowded car and poor safety standards.

According to the British Columbia Encyclopedia the Point Ellice Bridge Disaster was the worst accident in Canadian transit history. The cause was attributed to poor bridge maintenance, an overcrowded car and poor safety standards.

Most people know it as the Bay Street Bridge now—it’s been there since 1957, and it’s the sixth bridge to span the Upper Harbour.

Courtesy BC Archives G-04577

Courtesy BC Archives G-04577Top photo: Point Ellice Bridge disaster May 26, 1896. Stephen Joseph Thompson photo. Courtesy CVA Out-P247.1

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

May 19, 2018

Our Missing Heritage – Vancouver Police HQ

After I stumbled over a photo of the former Vancouver Police Headquarters on East Cordova Street, I asked my friend Tom Carter if he knew why it had been destroyed. Was it to make way for the uninspiring three-storey building that took its place? Tom didn’t know, but I thought his comment was interesting—that it had actually survived longer than many of Vancouver’s other Edwardian buildings.

After I stumbled over a photo of the former Vancouver Police Headquarters on East Cordova Street, I asked my friend Tom Carter if he knew why it had been destroyed. Was it to make way for the uninspiring three-storey building that took its place? Tom didn’t know, but I thought his comment was interesting—that it had actually survived longer than many of Vancouver’s other Edwardian buildings.

236 East Cordova Street shortly after opening in 1914. Courtesy CVA 371-2129

236 East Cordova Street shortly after opening in 1914. Courtesy CVA 371-2129“This never ceases to amaze me,” said Tom. “The second Hotel Vancouver was just over 20 years in use, and the old CPR station was around 20 as well. There were so many incredible Victorian Romanesque granite-clad buildings that also saw just 20 to 40 years of service.”

Amazingly the old Coroner’s Court and morgue (now the Vancouver Police Museum) and the firehall survived. Photo: CVA 447-63 , March 4, 1956.

Amazingly the old Coroner’s Court and morgue (now the Vancouver Police Museum) and the firehall survived. Photo: CVA 447-63 , March 4, 1956.When the building was completed in 1914, JFCB Vance (my hero from Blood, Sweat, and Fear) moved his lab into the top floor. When he walked in the front door and up the wide marble staircase he couldn’t help but notice the huge stained-glass window that let in the light. The stairs led to the second-floor courtrooms, chambers, and witness rooms. Prisoners were transported from the large jail upstairs to the courtrooms by a separate interior staircase. The building also had elevators, a gym, a tailor shop which churned out police uniforms, and a kitchen in which prisoners’ meals were prepared.

The Vancouver Police Headquarters was designed by William Alexander Doctor, an otherwise unnotable architect who arrived in Vancouver in 1908 and was gone nine years later. Doctor may not have designed many buildings, but this one was gorgeous—an imposing brick and steel building with a cream-coloured terra cotta façade.

It was built to last for centuries, instead it came down after just 42 years.

Here’s what we did with the space

Here’s what we did with the spaceTop photo: 236 East Cordova Street on July 22, 1956. Photo by Ernie H. Reksten, courtesy CVA 2010-006.170

Sources: Don Luxton’s Building the West: The Early Architects of British Columbia, 2007 and the Statement of Significance for William Doctor’s house at 5903 Larch Street.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.