Eve Lazarus's Blog: Every Place has a Story, page 31

March 8, 2019

Aborted Plans: Deadman’s Island

Members of the Town Planning Commission passed a resolution stating that they were not in favour of Deadman’s Island as a site for a proposed museum of Vancouver art, historical and scientific society. It was declared the Coal Harbour site was too inaccessible—Province: April 9, 1932

Deadman’s Island via Google

Deadman’s Island via GoogleIt continues to amaze me that Stanley Park has survived, despite all the attempts to develop it over the years.

In 1912, there was a push to “transform” Lost Lagoon into Grand Round Pond, with a surrounding museum, stadium and amusement park. There would be ornamental gardens, fountains a children’s playground, library and Georgia Street would be the “Champs-Elysees.”

Plans for Lost Lagoon in the Vancouver Sun, December 28, 2018

Plans for Lost Lagoon in the Vancouver Sun, December 28, 2018Fortunately, commonsense prevailed. Said Mayor James Findlay: “Thomas Mawson may be the finest architect in the world, but he cannot put Stanley Park back for us once it is destroyed.”

In the 1960s and ‘70s there were three attempts to turn Seasons Park—the 14 acres at the entrance—into a massive hotel and condo complex.

Sharp and Thompson Architects drawing of a proposed museum at Deadman’s Island in 1930. Courtesy VPL #7899

Sharp and Thompson Architects drawing of a proposed museum at Deadman’s Island in 1930. Courtesy VPL #7899And in the early ‘30s there were plans to plop what the Sun’s John Mackie describes as “an Empire State Building-style tower and an adjoining citadel-style building” on Deadman’s Island.

Sharp and Thompson Architects drawing of the Pacific Museum for Deadman’s Island. Courtesy VPL #7898

Sharp and Thompson Architects drawing of the Pacific Museum for Deadman’s Island. Courtesy VPL #7898Measuring just 3.8 hectares, and attached to Stanley Park by a short causeway, Deadman’s Island, or Skwtsa7s (meaning island), has an amazing history. It was a battle site. It was an indigenous burial ground, where the dead were placed in wooden coffins and buried both in the ground and up in the trees. When small pox hit, it was used to quarantine the victims, and later bury those who didn’t make it. The land has also claimed British Merchant seaman, people from Moodyville, victims from the Great, and workers killed while extending the CPR line from Port Moody to Coal Harbour. One article says West Vancouver’s Navvy Jack is buried there.

Deadman’s Island seen just behind the second CPR station at the foot of Granville Street in the early 1900s. Courtesy VPL #9834

Deadman’s Island seen just behind the second CPR station at the foot of Granville Street in the early 1900s. Courtesy VPL #9834In 1930, the federal government leased the island to the city. Shortly after, the city commissioned Sharp and Thompson Architects to draw up designs for Pacific Museum. It didn’t get very far, and in 1944, became the site of HMCS Discovery Naval Reserve.

When the 99-year lease came up for renewal in 2007, Mayor Sam Sullivan tried to make it publicly accessible. He told the Globe and Mail he wanted a ferry service from downtown and a museum that could preserve and display the maritime heritage of native people.

Vancouver in 1933 with Deadman’s Island in the background. Courtesy VPL 4368

Vancouver in 1933 with Deadman’s Island in the background. Courtesy VPL 4368The Musqueam just wanted it back.

Except for an open house once or twice a year, which I always seem to miss it, the site remains off limits.

Sources:

Jason Vanderhill’s Illustrated Vancouver

Vancouver Public Library’s Special Collections

Globe and Mail , April 27, 2006

Vancouver Sun , December 28, 2018

Vancouver Courier , March 30, 2010

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

March 1, 2019

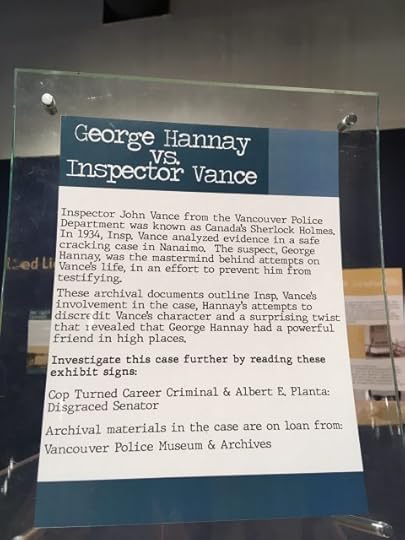

Nanaimo Mysteries

I’m currently experiencing technical problems with the blog. If you would like to subscribe to notifications, please send me an email at info@evelazarus.com and I’ll add you to the list.

With Aimee Greenaway, Nanaimo Mysteries curator

With Aimee Greenaway, Nanaimo Mysteries curatorAimee Greenaway was reading Blood, Sweat, and Fear when she came across George Hannay, a safe cracker from Nanaimo. She’d heard a story about the former BC Provincial police officer turned criminal, but this was the first time she’d seen evidence of his crimes.

Aimee thought Hannay’s story would make a great inclusion in the museum’s new exhibit—Nanaimo Mysteries.

The exhibit opened February 16, and my friend (and book editor) Susan Safyan and I went over to check it out. It’s the first time I’ve been to the Nanaimo Museum, and it blew me away.

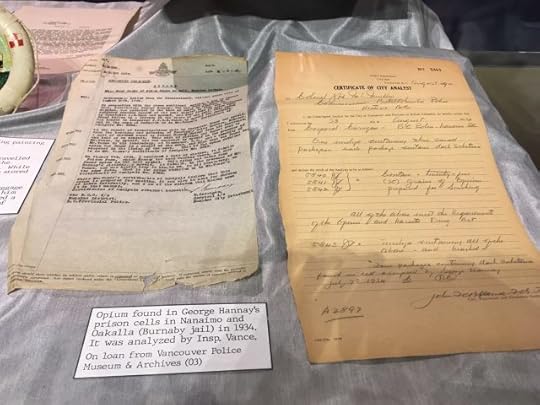

Inspector Vance, the subject of Blood, Sweat, and Fear and founder of the Vancouver Police Museum’s building on East Cordova Street, gets a starring role. Vance was known as the “Sherlock Holmes of Canada” in the media at the time, and in 1934 there were seven attempts against his life. The last and most brutal was an attempt to blind him with acid and stop him from testifying against Hannay in court. The attack was thought to be instigated by Hannay—at least the note left in Vance’s garage was signed “Hannay’s pals”— (apparently criminals weren’t too smart back then either). The attack on Vance delayed the trial, but went ahead a few weeks later with the Inspector under police guard.

Province, October 10, 1934

Province, October 10, 1934Vance linked Hannay to the robbery through trace evidence. But even though fibres found at the scene were from Hannay’s clothing and a splinter in his coat matched a floor board, the jury was unable to reach a decision because the foreman—a friend of Hannay’s—refused to bring in a guilty verdict.

The material for this chapter and the archival material that Aimee has curated for the display, was found in the garage of one of Vance’s grandsons, in 2016 while I was researching the book. He found several cardboard boxes filled with photos, newspaper clippings, forensic materials and case notes predating 1950. After the book was finished, the Vance family donated everything to the Vancouver Police Museum.

This is the first time any of these documents have been displayed, and there’s some intriguing, material including a letter that Hannay wrote to Vance’s boss in an attempt to discredit him. Aimee has also uncovered Hannay’s connection to Albert Planta, a corrupt senator from Nanaimo.

Nanaimo, it turns out, is quite mysterious. The exhibit has a section on hauntings and ghosts, another on murders and missing children, the red-light district and the infamous Brother X11, who started a cult in 1927 until 1932, when he and Madame Zee skipped town with donations from their wealthy followers.

The exhibit runs through until September 2, and if it’s your first time, there’s plenty of other things there to keep you fascinated, including the mystery of a samurai sword dug up in downtown Nanaimo in the late 1800s.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

February 23, 2019

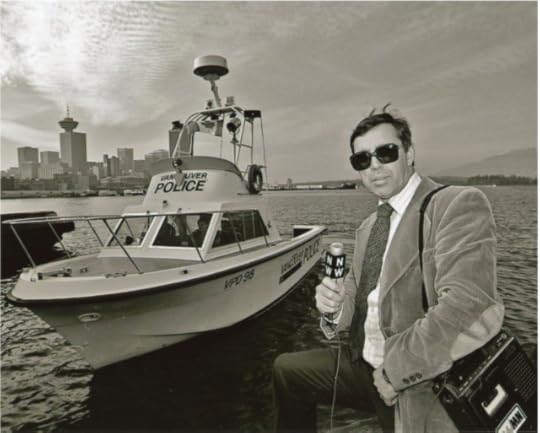

George Garrett: Intrepid Reporter

I’m currently experiencing technical problems with the blog. If you would like to subscribe to notifications, please send me an email at info@evelazarus.com and I’ll add you to the list.

If you listened to CKNW any time from the mid-1950s to the end of the ‘90s, you’ll remember George Garrett.

George Garrett in the CKNW news cruiser in 1959

George Garrett in the CKNW news cruiser in 1959His memoir, George Garrett Intrepid Reporter has just been published, and it’s a great ride through four decades of politics, disasters, consumer investigations and murders.

I met George in the mid-1990s, when I was a Vancouver Sun reporter at the beginning of my career and George was nearing the end of his. I’d studied some of his investigative work in journalism school which included going undercover as a tow truck operator to expose a scam in the ‘70s and covering a riot at the B.C. Pen.

George reporting from the North Shore in 1982. Alex Waterhouse-Hayward photo

George reporting from the North Shore in 1982. Alex Waterhouse-Hayward photoKnown as “Gentleman George,” because in the competitive world of journalism, he was just so darn nice. Daphne Bramham told me she once arrived late to a scrum and George handed her his notes. She asked him why he’d do that—a reporter from a competing media outlet—and he just said ‘why not?’

George helped me when I was researching Murder by Milkshake, my book about the murder of Esther by her husband CKNW personality Rene Castellani who was having an affair with Lolly, the young receptionist. George worked with Rene and knew “Lolly the dolly,” and covered the case for the station during Rene’s two trials for capital murder.

George covered the murder trial of Jeannine’s mother by her father Rene Castellani in 1966, but this was the first time he met Jeannine. Ashley Waller photo, 2018

George covered the murder trial of Jeannine’s mother by her father Rene Castellani in 1966, but this was the first time he met Jeannine. Ashley Waller photo, 2018George was there for all the major events. He covered the Second Narrows Bridge collapse in 1958 that claimed 19 lives and the Hope slide of January 1965.

He wrote the book the same way he reported his stories, with humour and compassion, relying on brief notes and memory. That doesn’t mean he wouldn’t go to great means to get a good story, and some of the methods he used are not only very funny, but should be required reading for journalism students.

He covered some of the most sensational murders of last century. There was the disappearance of Lynn Duggan in 1993, and the discovery of her skull in the North Vancouver forest a year later. Her boyfriend, a former VPD police officer was eventually charged in her murder and that of another girlfriend.

George covering the arrest of a woman in Clayoquot Sound in 1993 for CKNW

George covering the arrest of a woman in Clayoquot Sound in 1993 for CKNWThere was 19-year-old Sian Simmonds, sexually assaulted by her doctor and murdered by a hitman to stop her reporting him and ending his medical career.

George personally knew Doris Leatherbarrow and her daughter Sharon Heunemann who ran a lady’s wear shop in North Delta, and whose son/grandson Darren recruited two teenage friends to murder them so he could inherit the money. George went to the funeral and was shocked when Sharon’s husband wrote a eulogy with an unflattering description of her in gym wear. “After the service, I complimented the minister on how well he had conducted the service and commented on the husband’s eulogy, saying I wanted to make sure I quoted it correctly,” writes George. It was a thinly veiled attempt on my part to get that eulogy—and it worked! The minister reached into his inner jacket pocket and handed me the eulogy. I admit that sometimes I was shameless in order to get a good story.”

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

February 16, 2019

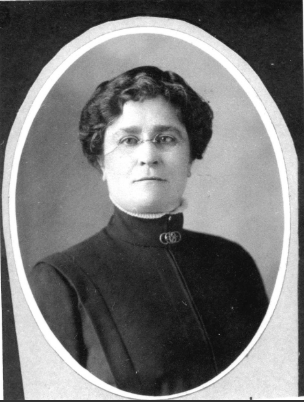

Muriel Lindsay, Murdered in Mole Hill

Several people have asked me, why out of hundreds of unsolved murders, I chose the 25 people for my book Cold Case Vancouver.

Mostly, they chose me.

Each person has a compelling story that needed to be told. Some like the Babes in the Woods are well known, but most just received an item or two in the newspaper and then disappeared, consigned to Vancouver’s not-so-nice history.

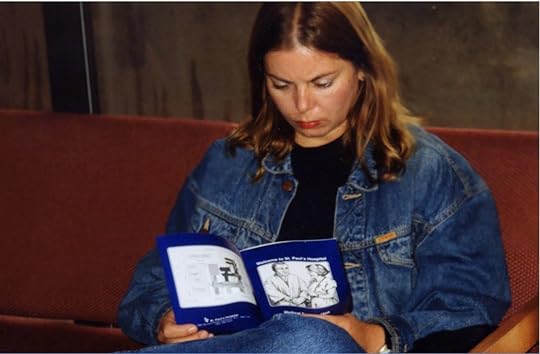

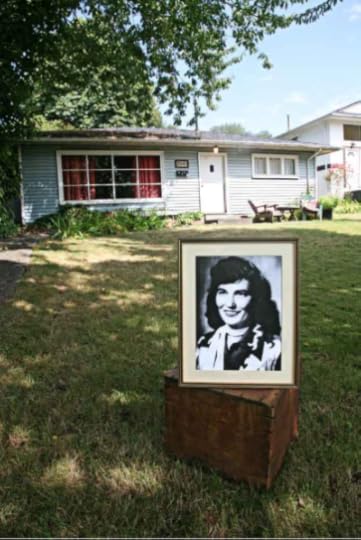

Muriel Lindsay waiting for cancer treatment at St. Paul’s Hospital ca.1990s. Photo courtesy Kent LIndsay

Muriel Lindsay waiting for cancer treatment at St. Paul’s Hospital ca.1990s. Photo courtesy Kent LIndsayMuriel Lindsay, for instance, was a 40-year-old Canada Post worker, who had recently beaten cancer, and was about to move into a new apartment when she was beaten to death in her West End boarding house. I contacted her brother Kent, and learned about Muriel’s story—one with many layers and connections to West Vancouver.

Richard Levis, 1914. Courtesy Vancouver Police Museum

Richard Levis, 1914. Courtesy Vancouver Police MuseumEight decades before Muriel’s murder, her great-grandfather Richard Levis, a 28-year-old Vancouver police officer, was shot and killed while hunting down a criminal known as “Mickey the Dago.” His wife Estelle was left to raise their three children—Cyril, Muriel and Carroll—all under the age of five. Estelle was hired as a matron in the women’s division of the Vancouver Police Department and worked there until 1919.

Cyril became an actor, and he and his brother Carroll Richard Levis, moved their families to England. Carroll became quite famous in the ‘40s and ‘50s hosting his own television program The Carroll Levis Discovery Show, on the BBC.

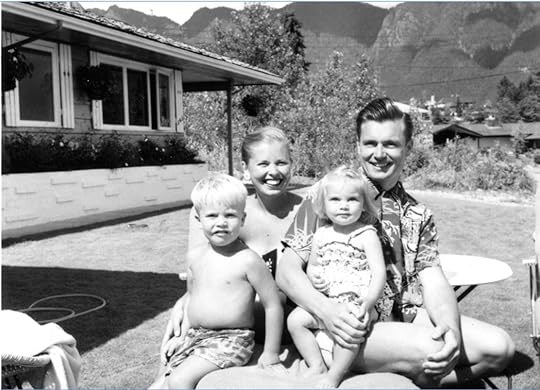

Kent, Marjorie, Muriel and Eric Lindsay at their British Properties home late 1950s

Kent, Marjorie, Muriel and Eric Lindsay at their British Properties home late 1950sMuriel (May), Muriel Lindsay’s namesake and grandmother, was a successful businesswoman in the ‘50s, who had the exclusive rights to sell real estate in the British Properties, and was a shareholder of West Vancouver’s Panorama Film Studios (the studio produced movies such as Carnal Knowledge and McCabe and Mrs. Miller). Muriel’s father, Eric Lindsay, was a celebrity photographer and reporter for the Vancouver Sun. Eric took a job with CBC’s the National and the family moved to Toronto. Soon after he split with his wife Marjorie, and young Muriel’s mental health started to unravel.

The Comox Street house where Muriel was murdered in 1996. Photo courtesy Quentin Wright

The Comox Street house where Muriel was murdered in 1996. Photo courtesy Quentin WrightMuriel eventually followed her mother and brother back to B.C., and in 1983, moved into a room in a heritage house in Mole Hill, where she stayed for the next 13 years. In the months before her death, she received bizarre anonymous letters, and her brother believes she had a stalker.

Part of a chilling letter Muriel sent to her father shortly before her murder. Courtesy Kent Lindsay

Part of a chilling letter Muriel sent to her father shortly before her murder. Courtesy Kent LindsayMuriel died from blows to her head and larynx, just after finishing her shift at Canada Post. Her mother found her body.

In April 2017, I received an email from a man who had heard another man talk about murdering Muriel Lindsay some years ago. I chatted with him, and for a number of reasons, he didn’t want to contact police; so I did it for him. I was told by a VPD sergeant that the “file was solved” and the man my source mentioned, wasn’t the suspect. I’m not sure what this means-that the suspect is dead, or in jail or they just don’t have the evidence to convict him, and I can’t find out, because police won’t talk about unsolved cases.

Find the full story of Muriel Lindsay in Cold Case Vancouver: the city’s most baffling unsolved murders.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

February 2, 2019

St. Andrews-Wesley Church’s $30 Million Dollar Makeover

I’m currently experiencing technical problems with the blog. If you would like to subscribe to notifications, please send me an email at info@evelazarus.com and I’ll add you to the list.

I have just acquired a piece of St. Andrews-Wesley Church. A rug that’s worn in all the places that you’d expect of something that has graced the entranceway of this downtown heritage building for eight decades and hosted thousands of multi-denominational feet.

The renovations were made possible by the sale of church land and a 20-storey condo tower in 2002.St. Andrews-Wesley church at Burrard and Nelson is a special kind of place, and I was lucky to get a tour from Kathy Murphy last month before the church closes for a $30 million makeover.

It’s the first time I’ve been inside the church, and even in its less-than-perfect self, it’s breath-taking. From the stained-glassed windows to the gothic tower, it’s easy to see why people want to get married or buried there, play music, shoot movies, and yes, even worship.

St. Andrews Presbyterian Church at 686 Richards Street ca.1934 (now a 10-storey building designed by Zoltan Kiss in 1974 and the new home of Canada Post) Courtesy Vancouver Archives

St. Andrews Presbyterian Church at 686 Richards Street ca.1934 (now a 10-storey building designed by Zoltan Kiss in 1974 and the new home of Canada Post) Courtesy Vancouver ArchivesWhile the Church has operated from the corner of Burrard and Nelson since 1933, it was the result of a merger between St. Andrews Presbyterian Church and Wesley Methodist, both designed by William Blackmore, and both demolished in the early ‘30s.

Wesley Methodist Church at the corner of Burrard and West Georgia in 1908. Built (1900-1904) courtesy BC Archives B-01433

Wesley Methodist Church at the corner of Burrard and West Georgia in 1908. Built (1900-1904) courtesy BC Archives B-01433It was the Great Depression when the current church opened, and there wasn’t a lot of cash. The pews were made from fir instead of oak. The bell tower didn’t have a bell, and the planned terrazzo floor became a cheap lino stop-gap. The temporary fix became permanent, and will now be updated along with a seismic upgrade, a new copper roof, and an electrical system that will also light up the incredible stained-glass windows.

January 2019. Eve Lazarus photo

January 2019. Eve Lazarus photoThe Mandela of Compassion will go back after the rehab, and its very presence is an indication that this is a different kind of church. Made of sand by three Buddhist monks over three days, the Mandela looks like an exquisite tapestry. Normally, the monks, who do not believe in having material things stick around, would blow the sand away when they’d finished, but church officials talked them into letting it stay.

The Mandela of compassion, made in three days in 2009

The Mandela of compassion, made in three days in 2009The pipe organ—the largest in Vancouver—is off to Montreal for a refit. While we were up there inside the guts of the organ, Darryl Nixon, Minister of Music, started playing the music he’d chosen for the following Sunday’s service.

Darryl Nixon, playing the pipe organ. January 2019. Eve Lazarus photo

Darryl Nixon, playing the pipe organ. January 2019. Eve Lazarus photoThe chapel is as an interesting room. Aside from hosting Tony and Tina’s wedding for 14 years, it has a 14-foot tracker organ (that’s for sale). The room has been used for small weddings and for yoga, the pews long ago repurposed into a cabinet, a table, and a casket for the carpenter.

Kathy Murphy with the church’s oldest artifact. Eve Lazarus photo

Kathy Murphy with the church’s oldest artifact. Eve Lazarus photoThe Church is expected to be closed for up to two years. But it’s not too late to see it. Services run as normal tomorrow Sunday February 3.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

January 26, 2019

The Maharajah of Alleebaba

I’m currently experiencing technical problems with the blog. If you would like to subscribe to notifications, please send me an email at info@evelazarus.com and I’ll add you to the list.

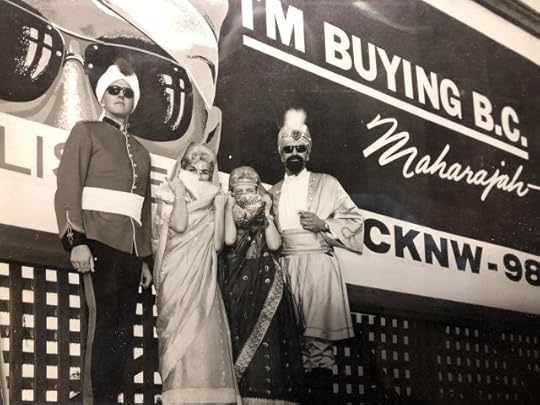

Last week, Bob Shiell sent me a note telling me that he worked with Rene Castellani at CKNW in the early 1960s, and was a huge force in one of the station’s most visible promotions—the Maharajah of Alleebeeba.

I wrote about Rene the Maharajah in Murder by Milkshake, but Bob added a personal twist.

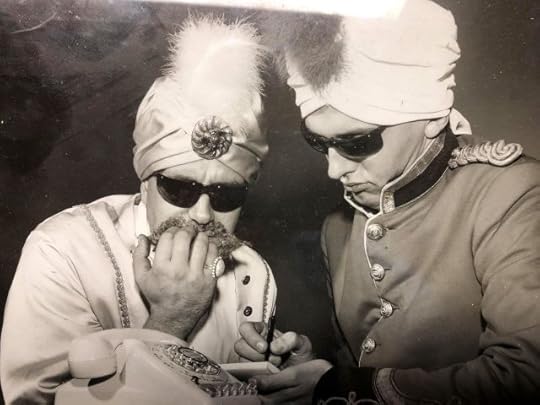

Rene Castellani and Bob Shiell in 1963, courtesy Bob Shiell

Rene Castellani and Bob Shiell in 1963, courtesy Bob ShiellIn 1963, Bob was 22 and worked in the promotions department for CKNW. Rival station CKLG had brought up Marvin Miller, an actor in a US-show called the Millionaire (1955-1960) where Miller give away money to people he’d never met. CKLG saw this as a great way to boost ratings in the upcoming BBM wars and had Miller go around town handing out cash.

“We had to come up with an idea for something that would counter that,” says Bob, and the Maharajah was born. “The idea was that he was coming over to buy the province of British Columbia.”

Courtesy Bob Shiell

Courtesy Bob ShiellRene was hired and dressed up as the Maharajah. Bob played Ugie, his driver and wore a red tunic and striped pants. The black Rolls Royce was a loan from one of the station’s owners—Robert Ballard, of Dr. Ballard’s dog food. They hired an off-duty motorcycle cop who provided an escort, and two women who normally did in-store food demonstrations for the station were dressed up as harem girls.

“We had a crossed sword logo made with sticky tape and we put that on the passenger and the driver’s door, and I found a little flag—the kind of embassy flag that you see on the President’s car. It was actually the flag of the Republic of Germany, but nobody noticed,” says Bob.

The Maharajah at a BC Lions game at Empire Stadium. Courtesy VPL)

The Maharajah at a BC Lions game at Empire Stadium. Courtesy VPL)They stashed the Rolls at Bob’s Mum’s house on Granville Street, met there each morning and got changed in the basement. For two weeks the entourage drove around Vancouver—to clubs, restaurants, hotels, drive-ins, and a BC Lions game at Empire Stadium, often accompanied by a CKNW reporter named Sherwin Shragge (yes, that’s his real name) who would interview them on radio.

“I had this big leather suitcase handcuffed to my wrist full of silver dollars,” says Bob. “I would go around and give people a silver dollar from the Maharajah.”

Rene, says Bob, was a great guy to work with. “He just loved it, he was a born Maharajah, he loved the attention, he loved the harem girls, he loved riding around in the rolls Royce, it was the ideal role for him.”

In fact, it was so successful that locals got out with their hand made signs that said “Keep BC British.”

“A lot of people took it really seriously, they really bought into this whole idea, they did a really good job of selling this concept of a guy coming in to buy the province,” says Bob.

A little over a year later, Rene Castellani would become famous for poisoning his wife Esther with arsenic milkshakes . Read the story in Murder by Milkshake.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

January 19, 2019

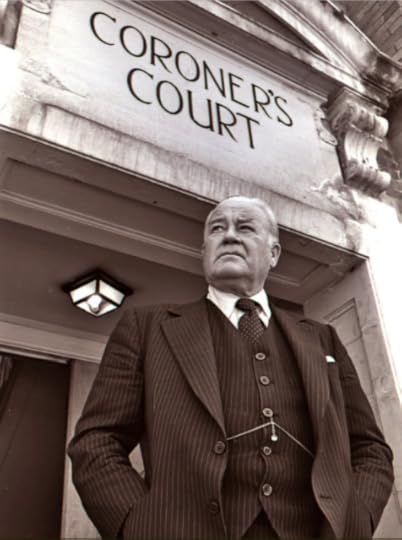

Glen McDonald: Vancouver’s Colourful Coroner

I’m currently experiencing technical problems with the blog. If you would like to subscribe to notifications, please send me an email at info@evelazarus.com and I’ll add you to the list.

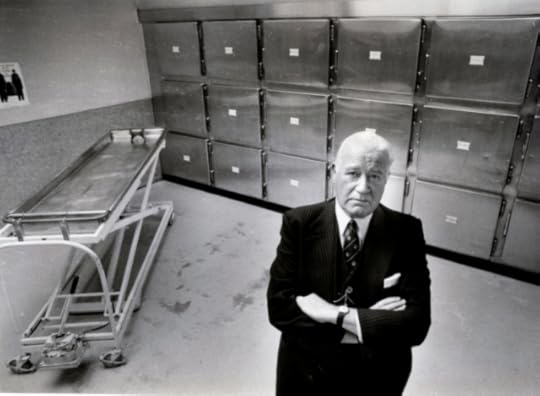

Glen McDonald Courtesy Vancouver Sun, 1979.

Glen McDonald Courtesy Vancouver Sun, 1979.If I was able to go back in time and choose six people to interview, Glen McDonald would be high up on the list. I got to know him while I was researching Murder by Milkshake, and his 1985 book How Come I’m Dead? has a prime position on the book shelf above my desk.

McDonald was Vancouver’s coroner from 1954 to 1980. Unlike the star of CBC’s new show Coroner, McDonald was not a doctor. In BC—and I’m quoting from a government job posting—there are 32 full-time coroners with backgrounds in law, medicine, investigation and journalism.

Glen McDonald, courtesy Vancouver Sun 1965

Glen McDonald, courtesy Vancouver Sun 1965McDonald, who was a lawyer and a judge, called himself the “Ombudsman of the Dead.” He told people it was his job to find the cause of death in order to help the living, and he did this from his morgue on East Cordova Street, where an average of 1,100 bodies passed through each year. He smoked 50 cigarettes a day, drank beer and spirits kept beside forensic specimens in an office fridge, and conducted one or two inquests a week that looked into deaths ranging from shootings and stabbings to drug overdoses and traffic accidents.

You can visit McDonald’s old morgue and Coroner’s Court at the Vancouver Police Museum, 240 East Cordova Street. Courtesy VPM

You can visit McDonald’s old morgue and Coroner’s Court at the Vancouver Police Museum, 240 East Cordova Street. Courtesy VPMHis job was to assemble a jury and determine whether death was natural, accidental, suicide, or homicide. After he retired, he admitted to occasionally lying to priests so that his Catholic victims could be buried in consecrated ground. He’d say he hadn’t reached a conclusion. The funeral would go ahead as if the death was not a suicide and McDonald would sign the death certificate when the body was safely in the ground.

He said his job was to find the cause of death in order to protect the living, and he investigated everything from deaths by shooting, stabbing, and strangulation, to poisoning, suicide, drug overdoses, and death by traffic, rail and boat accidents.

Glen McDonald. Photo by Alex Waterhouse-Hayward for Vancouver Magazine, 1984

Glen McDonald. Photo by Alex Waterhouse-Hayward for Vancouver Magazine, 1984He officiated over the Inquest of 18 men who were killed when the Second Narrows Bridge collapsed while under construction in 1958. And, he was in charge when CP Flight 21 blew up over the BC Interior killing all 52 people on board in 1965.

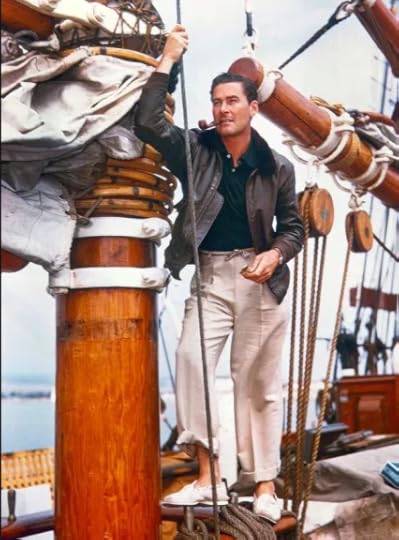

One of his more famous cases was the death of Aussie actor Errol Flynn in 1959. Flynn, 50, was in Vancouver with his 17-year-old girlfriend trying to sell his yacht Zaca to a local millionaire. He had a heart attack while at a party in the West End and ended up in McDonald’s morgue. (The full story is in Sensational Vancouver).

Errol Flynn aboard the Zaca. From the collection of Luther Greene

Errol Flynn aboard the Zaca. From the collection of Luther GreeneThe first time McDonald came across death by arsenic poisoning was in 1965 with the murder of Esther Castellani. The first thing he did was install himself in the science section of the VPL and read everything he could find about arsenic poisoning. As he wrote in How Come I’m Dead? he suspected that Rene Castellani had been at the library some months before, doing exactly the same thing.

My favourite McDonaldism is when he gained national notoriety for calling Bingo Canada’s most dangerous sport. He was referring to the number of seniors who were run over while walking to their weekly games.

McDonald died 23 years ago—on January 23, 1996. He was 77.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

January 11, 2019

Fritz Autzen and the West End’s Hippocampus

I’m currently experiencing technical problems with the blog. If you would like to subscribe to notifications, please send me an email at info@evelazarus.com and I’ll add you to the list.

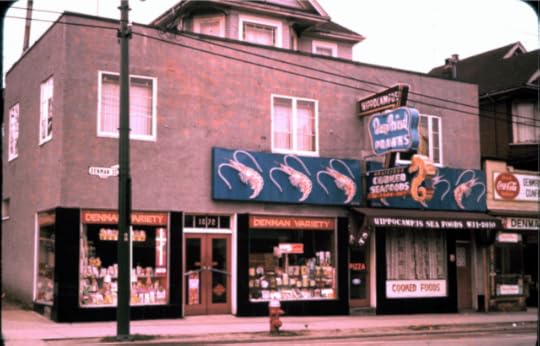

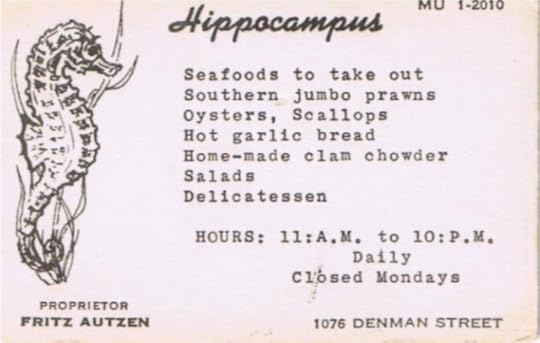

The Hippocampus at 1076 Denman Street, ca.1960. Fritz Autzen photo

The Hippocampus at 1076 Denman Street, ca.1960. Fritz Autzen photoWhen Fritz Autzen, a baker from Neukölln, Germany moved his family to British Columbia in 1954, his first job was a cook at the Surrey Drive-in based in Newton. Five years later he moved his family to the West End and took over the Hippocampus, a fish & chip shop and deli on Denman and Comox Streets.

The Surrey Drive-in, 1956. Fritz Autzen photo

The Surrey Drive-in, 1956. Fritz Autzen photoWhen he wasn’t working, Fritz loved to take photos in and around Vancouver, and his daughter Chris Stiles recently sent me some of her favourites.

One of them is of a business card with the opening hours 11 am to 10 pm Tuesday to Sunday. “I remember the first few years my dad had the business he never closed for holidays because he was afraid that somebody else would come and take his customers,” she says.

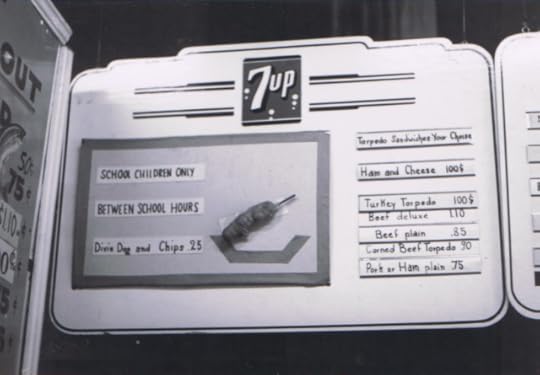

Fritz invented the torpedo sandwich and garlic vinegar to put on your fish and chips.

Fritz Autzen invented the Torpedo Sandwich, a forerunner to the Subway.

Fritz Autzen invented the Torpedo Sandwich, a forerunner to the Subway.Chris and her older brother Michael went to Lord Roberts Elementary. The house and business are still there—one of a row of four along Denman near Davie, and some of Vancouver’s few remaining “buried houses.”

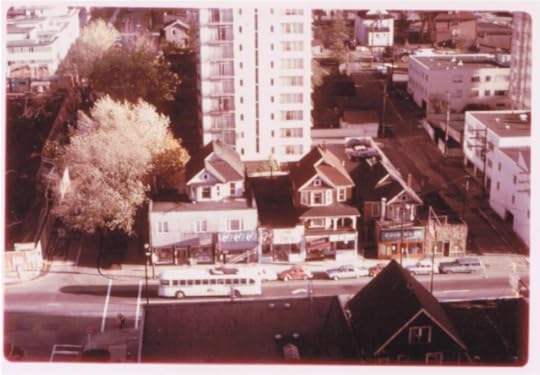

In this photo of the 1000 block Denman you can see the early construction of Denman Place Mall on the left of the frame. Fritz Autzen photo, ca.1965

In this photo of the 1000 block Denman you can see the early construction of Denman Place Mall on the left of the frame. Fritz Autzen photo, ca.1965The houses were built in the early 1900s, but a look through the city directories shows the storefronts weren’t added until the 1940s. By the end of that decade, Harry Almas, who owned the King Neptune Seafood Restaurant in New Westminster, and in 1959, North Vancouver’s Seven Seas Restaurant at the foot of Lonsdale Avenue, bought the house and divided it into three apartments. The Hippocampus was added in 1953. Fritz and Herta moved into Harry and Eva Almas’s apartment and managed the other two apartments in return for a break in the rent.

Fritz Autzen at work in the Hippocampus ca.1960. Courtesy Chris Stiles

Fritz Autzen at work in the Hippocampus ca.1960. Courtesy Chris StilesBecause Monday was the only day the store closed, Fritz would grab his camera and take the kids out of school and hit Stanley Park, pick huckleberries at Lost Lagoon, and eat at the Marco Polo in Chinatown. In summer, the kids would wait for the diving barge and slide to come in at English Bay.

Chris still has Fritz’s immigration papers when he entered Canada a few months ahead of his family in 1954. His net worth was $226 and included his clothes (valued at $160), a pair of binoculars and his Teco camera.

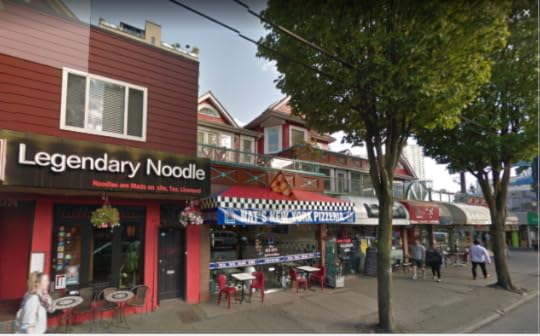

Denman Street “buried houses” in 2017

Denman Street “buried houses” in 2017The family lived above the store from 1959 to 1967. That year they moved to Richmond and Fritz opened the Seahorse Café.

When Fritz died in 1981, he left over one thousand slides.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

January 5, 2019

Guy in the Sky: The BowMac Sign

The following story is an excerpt from Murder by Milkshake: An Astonishing Story of Adultery, Arsenic, and a Charismatic Killer.

Photo courtesy Angus McIntyre ca.1968. From the roof of the Fairmont Apartments at Spruce and W.10th

Photo courtesy Angus McIntyre ca.1968. From the roof of the Fairmont Apartments at Spruce and W.10thOn June 4, 1965, CKNW personality Rene Castellani climbed to the top of the scaffolding next to the BowMac Sign and promised not to come down until every last car on the lot was sold.

That would take nine days.

Courtesy Vancouver Archives, ca.1960.

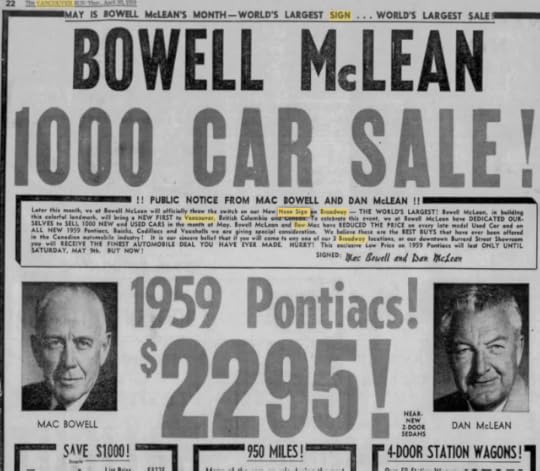

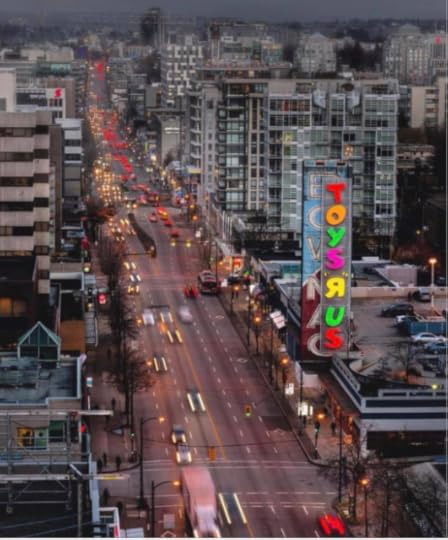

Courtesy Vancouver Archives, ca.1960.These days, the scene takes a bit of imagination. Auto row and the Bowell McLean Motor Company on West Broadway are long gone, and the giant neon sign has been neglected and was partially covered over by the current tenant—Toys-R-Us—more than 20 years ago.

But back to 1965.

The BowMac car dealership had a history of staging stunts to lure customers away from the Dueck Chevrolet Oldsmobile dealership down the road. Under Jimmy Pattison’s management, promotions included dressing up a performing monkey in overalls and hiring the Leavy brothers—seven-foot-tall twins—to hang out in the used car lot. In 1958, Pattison staged what was billed as the “world’s largest checker game” where models in red or black bathing suits became the checkers moving across a board of two-foot squares.

Pattison topped even that the following year when he commissioned Neon Products—a company he later brought—to build a sign the height of a seven-storey building with orange and red letters that spelled BOWMAC, and powered by a transformer that could light up 30 houses.

The sign cost $100,000, weighed 12 tons, and was briefly North America’s largest free-standing sign.+

April 30, 1959. Courtesy Vancouver Sun

April 30, 1959. Courtesy Vancouver SunCastellani’s assignment was called “the Guy in the Sky” and the stunt called for him to live in a station wagon next to the neon sign. The station wagon was equipped with a telephone and a direct line to CKNW, bedding, and a chemical toilet. Food was sent up to him in a bucket. The car was brightly lit up, and he was quite visible from the ground most of the time. He would give regular broadcasts from the tower. Passerbys were encouraged to drive by and honk their horns, and they could see a clothesline strung from the station wagon to the sign with a pair of Castellani’s shorts swaying in the wind.

Rene Castellani and Jack Cullen, ;1964. Courtesy Colleen Hardwick

Rene Castellani and Jack Cullen, ;1964. Courtesy Colleen HardwickThe BowMac Sign promotion became a central part in Castellani’s capital murder trial for the arsenic poisoning of his wife Esther. A Toronto lab was able to use a nuclear reactor to chart the progress of arsenic in Esther’s hair and fingernail growth and provide a rough timeline of when she received the poison and in what quantities. Esther, who had been in Vancouver General Hospital for the nine-day duration of the promotion, had greatly improved while Castellani was away. On the day after he came back down from the sign, she got really ill and never recovered. It coincided with the charts that showed she had received a massive dose of arsenic while she was in hospital and sometime within 35 days of her death on July 11, 1965.

From FB group I Grew up in Vancouver. Photographer unknown

From FB group I Grew up in Vancouver. Photographer unknownAs for the sign, it was the subject of a Heritage Revitalization Agreement in 1997 where Toys-R- Us was allowed to add their signage instead of demolishing the sign. That agreement now runs until 2022 or until Toys-R-U goes bankrupt.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

December 22, 2018

The Introvert’s Guide to the Holiday Season

After you’ve spent most of December at Christmas Parties and work functions, the small talk can just dry up. Here are some conversational kickstarters to get you back on track over the holiday festivities and help you find your feet.

The Story of the Severed Feet

I was at a Christmas party last week when the conversation turned to severed feet. You remember all those ones that turned up wearing running shoes in spots like False Creek, Richmond and Gabriola Island? It wasn’t some twisted serial killer or gang sign, when the body decomposes the feet separate (disarticulate). Normally the feet would sink, but sneakers like Nike Air have air pockets, which turns them into little life jackets. Sadly, the found feet belonged to suicides.

The Ku Klux Klan’s Shaughnessy digs:

In 1925, the Ku Klux Klan moved into a Glen Brae, a Shaughnessy mansion on Matthews Street. While Vancouverites were a racist bunch back then, apparently living near a mob of men wearing white robes and hoods and carrying fiery crosses through the tree-lined streets, was over the top. The KKK lasted less than a year in Vancouver. The mansion is still there, it’s now Canuck’s Place Children’s Hospice.

Source: At Home With History: The Secrets of Greater Vancouver’s Heritage Houses

KKK at Glen Brae in 1925. Courtesy CVA 99-1501

KKK at Glen Brae in 1925. Courtesy CVA 99-1501Hit and Run Over:

My favourite Chuck Davis story is from October 6, 1909. Vancouver’s first mechanized ambulance was out for a trial spin, dodged a couple of streetcars and then hit and killed a wealthy American tourist crossing Granville and Pender Street. The story ran in several North American newspapers and reported that C.F. Keiss, from Austin, Texas was in Vancouver “preparing to start on an extended hunting trip.”

Source: The Chuck Davis History of Metropolitan Vancouver

Vancouver’s first ambo would have looked something like this. Courtesy Just a Car Guy

Vancouver’s first ambo would have looked something like this. Courtesy Just a Car GuyLurancy Harris’s Beat

If you think it’s tough being a woman in the police, RCMP or military ranks today, imagine what it was like back in 1912 when Lurancy Harris became one of the first two women police officers in Canada. She was sworn in as a fourth-class constable, given full police powers and thrown into the job with no training, no uniform and no gun. Her big break came when she got the job of escorting Lorena Mathews on the train back to Oklahoma to stand trial for murder. Mathews had bolted to Vancouver with her two children and Jim Chapman, her 25-year-old black lover who were suspected of murdering her much older husband (you just can’t make this stuff up!) Chapman was convicted, Mathews was acquitted and Lurancy got a promotion. She ended her career as an inspector with the VPD, although she was kept at the pay scale of a sergeant.

Source: Sensational Vancouver

Lurancy Harris

Lurancy HarrisShark Attack in False Creek:

On July 5, 1905 eight-year-old Harry Menzies was wading near the mouth of False Creek when he was nearly eaten by a 1,100 pound shark. “The boy ran; the shark followed,” reported the Vancouver Daily World. Ed Dusenberry saw the dorsal fin and attacked the shark with the hook of a pike pole and tried to pull it ashore. “Enraged by the pain, the shark opened its mouth and showed the most ferocious set of teeth he had ever seen, something like a man would expect in a horrible nightmare.” After it died, Dusenberry put a tent up around the shark and charged 10 cents admittance.

Source: This Day in Vancouver

Courtesy Past Tense

Courtesy Past TenseThe World Belly Flop and Cannonball Diving Championship

Yup, belly flops started here in Vancouver, or more accurately, were a way to publicize the (Westin) Bayshore’s new pool in 1974. The event quickly gained momentum and spread to the old Coach House Inn in North Vancouver, drawing between 3,000 and 4,000 spectators, entrants from Fiji and Japan, as well as US President Jimmy Carter’s brother Billy as a judge. Tom Butler, the PR guy behind the stunt, told the Globe and Mail: “It’s something that is universally understood. I mean, there’s no subtlety to it. But what else can a 300-pound truck driver do and get to have NBC television declare that he’s champion of the USA?”

Source: Tom Butler, the Coach House Inn and the Belly Flop that Soared

Coach House Inn, 1979. Courtesy John Denniston

Coach House Inn, 1979. Courtesy John DennistonLoretta Lynn and the Chicken Coop

Country music singer Loretta Lynn was discovered in Vancouver. No, it wasn’t at the Cave or the Palomar or another club of those times, she was singing in a backyard chicken coop on East Kent Avenue in Fraserview. Executives from a local record company called Zero Records, and with financial backing from Art Phillips (who became mayor in 1973), heard her sing, signed her up, and Loretta’s first single “I’m a Honky Tonk Girl,” came out in 1960.

Source: Vancouver Was Awesome: A curious Pictorial History

Courtesy Vancouver Courier, 2012

Courtesy Vancouver Courier, 2012Van-Tan

Have you hard the story about the nudist camp at the top of Mountain Highway in North Vancouver? Turns out it’s not an urban myth, Van Tan was founded in 1939 and now has about 60 members that get to hang out sans clothes on several acres of cleared forest. When you get to the car park, it’s behind a locked gate, and another two clicks up a curvy, unpaved road. Sure you can hike it, but why not wait and check it out at one of their open houses this summer?

Source: Van Tan Nudist Camp

Eve Lazarus photo, 2016

Eve Lazarus photo, 2016Project 200

Gordon Price called it “the most important thing that never happened” to Vancouver, and certainly if Project 200 and the rest of the freeway plans had gone ahead, Vancouver would be unrecognizable today. The plan was to construct a freeway system that would connect Vancouver to the Trans-Canada Highway and to Highway 99. The freeway would run between Union and Prior Streets, and wipe out Strathcona, most of Chinatown, much of the West End, plop an ocean parkway along English Bay, and turn Vancouver into a mini Los Angeles. To get a sense of the magnitude of Project 200, check out the plaza and the tower at the foot of Granville Street. Then imagine a forest of office and residential towers, plazas, a major hotel, and parking for 7,000 cars that would take out Waterfront Station, most of the Sinclair Centre and the heritage buildings in Gastown.

Source: aborted plans

The Murder Factory

If you are driving up East Cordova Street these holidays, take a look at #629. It’s now a duplex, but back in 1931 it was a “private hospital” run by a Japanese man named Shinkichi Sakurada. Sick people would go in, they’d take out an insurance policy naming Sakurada as their beneficiary, and then they would die. According to the Globe and Mail, the “murder factory” was run by an “organized assassination ring” and was responsible for as many as 20 deaths.

Source: Blood, Sweat, and Fear: The Story of Inspector Vance, Vancouver’s First Forensic Investigator

Eve Lazarus photo, 2017

Eve Lazarus photo, 2017© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.