Eve Lazarus's Blog: Every Place has a Story, page 35

May 12, 2018

Let’s Do The Scramble

There’s a Facebook post going around about “pedestrian scrambles”—intersections where every car stops and pedestrians cross in all directions.

It’s a simple concept that saves you from being turned into road kill by a turning car.

The video goes onto tell us that “over 40% of pedestrian crashes happen at intersections,” and after scrambles are implemented “severe crashes have gone down by 63%.”

More cities are using them—they’re now in Los Angeles, Portland and Washington, DC.

Pedestrian scramble at Granville and Hastings Streets in 1952. Courtesy CVA 772-15

Pedestrian scramble at Granville and Hastings Streets in 1952. Courtesy CVA 772-15Okay, that’s nice, but innovative? No, that makes it sound like something that the Americans have just invented.

Melbourne has had a crisscross, as we called them, for as long as I can remember at Elizabeth Street, across the road from the Flinders Street Station. Albury, a town on the border of NSW and Victoria also has one.

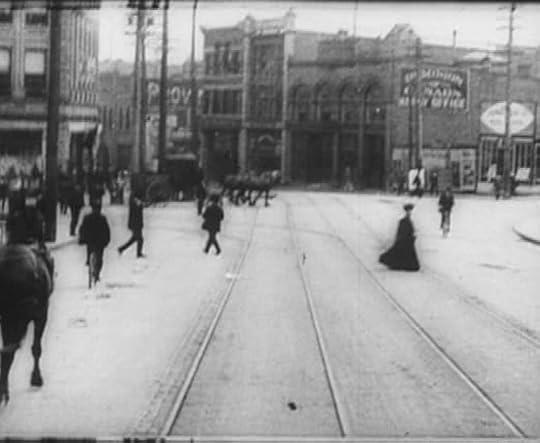

Pedestrian scramble at Granville and Hastings Streets ca.1940s. Courtesy CVA 1184-1810.

Pedestrian scramble at Granville and Hastings Streets ca.1940s. Courtesy CVA 1184-1810.According to Wikipedia, Vancouver was one of the first cities in the world to use them at Granville and Georgia and Granville and Hastings Streets way back in the 1940s. After that it caught on with a traffic engineer from Denver, Colorado who introduced the scramble to his city in the late 1940s and it became known as the Barnes’ Dance, because “Barnes had made people so happy they’re dancing in the streets.”

London, Ontario has had one since the 1960s, and many cities in Canada have them including Calgary and locally here in Steveston, BC.

Pedestrian scramble in Steveston, courtesy Binnie Engineering

Pedestrian scramble in Steveston, courtesy Binnie EngineeringToronto has at least three but took out its Bay and Bloor scramble after a staff report that sideswipes had more than doubled and rear-end crashes were up by 50% “likely due to increased driver frustration.”

The scrambles stayed in Vancouver until the ‘60s when they were nixed because they put pedestrians before cars. More recently, plans to introduce one along Robson Street were cancelled because they could prove confusing for the blind.

Nothing, I’m sure that couldn’t be fixed by a little innovation.

Nothing, I’m sure that couldn’t be fixed by a little innovation.

So, what do you think, should we scramble our busiest crossings or leave them alone?

And while we’re at it, let’s bring back the streetcar.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

May 5, 2018

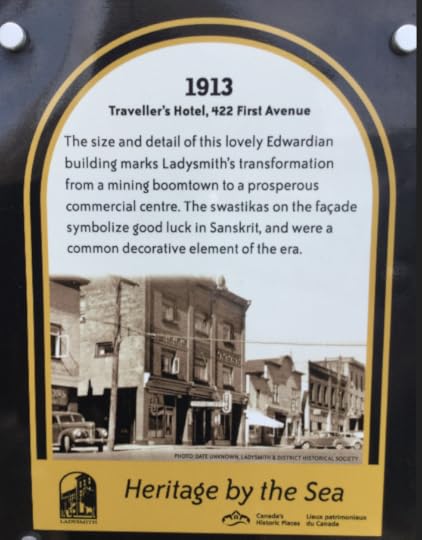

Swastikas and the Traveller’s Hotel

I was over on Vancouver Island this week doing some biking and stopped in at Ladysmith. It’s the first time I’ve been there and it was great to walk down a main drag that still has many of its heritage buildings. Most were in good shape—the one glaring exception was the Traveller’s Hotel which sits on a hill on First Avenue.

Eve Lazarus photo, May 2018

Eve Lazarus photo, May 2018The three-storey Edwardian building is in rough shape, but what struck me was the line of brick swastikas along the façade of the building. I was surprised to learn that swastikas were not a Nazi invention but rather something they co-opted from Asian culture in the 1920s.

According to Wikipedia, Swastika (from Sanskrit Svastika) is an ancient religious symbol that means good luck and dates back at least 11,000 years.

The Traveller’s Hotel was built in 1913, years before the Nazi party turned luck into something evil.

Aside from several grave markers in a Japanese cemetery in Cumberland, it may just be the only structure still standing in Canada that has retained these symbols and their true history.

It’s been a couple of decades since the Traveller’s Hotel was an actual hotel. A biker ran wet T-Shirt contests there at one point and for many years it was overrun by squatters.

Other plans that have fallen through over the years include condos and retail, condos and a restaurant, a chocolate manufacturer and a boutique hotel.

Realtor Wes Smith says more recently the Traveller’s Hotel almost sold to an investor who planned to renovate the building and turn it into a dispensary and vape lounge, as he did quite successfully with the Globe Hotel in Nanaimo. The deal fell through when the City of Ladysmith introduced a by-law to kick marijuana out of town.

Bridget from the Ladysmith and District Historical Society tells me that when she moved to the town in 1966 the hotel was a “jumping, hopping place” and stayed that way through the 1970s and ‘80s.

“It was the place to go on Saturday nights,” she said. “You couldn’t get a parking place on First Avenue for all the different hotels in the evening and on the weekend.”

Courtesy Ladysmith and District Historical Society

Courtesy Ladysmith and District Historical SocietyI didn’t spend much time in Ladysmith, but there didn’t seem to be a huge amount of night life left.

That may change now that a father and son team (the son is a chef) have bought the building and plan to renovate and revitalize it and open an upscale restaurant on the ground floor and a hotel upstairs. Wes says the plan is to have the restaurant open in the fall.

I’m happy the hotel will survive, I hope the Swastika’s do as well—it’s important not to erase our history.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

April 28, 2018

City Reflections: The Epic

I am excited to tell you that City Reflections is now on YouTube . As you’ll read in John Atkin’s story, it was a massive volunteer undertaking by members of the Vancouver Historical Society. It has been, and will continue to be, a huge tool for researchers—I would never have got John Vance (Blood, Sweat, and Fear) to work on his first day in 1907 without it!

A huge thank you to Jason Vanderhill for getting me the stills from the film.

By John Atkin, civic historian

It was a silent, jerky and disjointed film shot from the front of a BC Electric streetcar in 1907 that captivated the Vancouver Historical Society’s audience members one September evening in 2004. Colin Preston, the former CBC Archivist had just introduced everyone to a recently restored version of the earliest known moving image of the city.

The film shot by American film maker William Harbeck was one of a series that played in specially designed theatres that replicated the experience of riding a streetcar. Long thought lost, the film was rediscovered in Australia and sent to the Library of Congress, eventually ending up with Library and Archives Canada.

As the evening ended someone in the audience suggested that it would be fun to create a modern version of the film. And with that, a project was born. It sounded simple enough, so a small group of volunteers got together to think about and begin planning how to tackle the job of recreating Harbeck’s film. The self-imposed deadline of 2007, the film’s hundredth anniversary seemed far enough away to be doable.

However, the project quickly shifted from just reshooting the route to developing a documentary about Harbeck, annotating the streetcar’s route and developing background information about Vancouver in 1907. Scripts were written and then rewritten and written again as the focus of the project shifted.

Wes Knapp chaired the project and helped secure sponsors. Colin Preston contributed the best possible copy of the film on DVD. John Atkin, Andrew Martin and Chuck Davis did much of the research. Mary-Lou Storey acted as production manager. Ernst Schneider and Jason Vanderhill contributed technical expertise and graphic design. John Atkin and Jim McGraw worked on the script. Jim did the final storyboard, directed and narrated. Paul Flucke oversaw the finances.

The project timeline was thrown for a loop with the announcement of the Canada Line construction which meant Granville Street would be off limits in 2007, so initial filming was moved up a year.

On shooting day, the team assembled at CBC on Hamilton Street to set up the camera car and get ready to hit the streets. CBC had generously supplied a camera man (Mike), camera and video stock to assist us in the shoot. Andy and Pacific Camera Car supplied the truck and Vancouver’s film office helped us out on the closure of Cordova Street—we had to drive the wrong way to match the 1907 route.

Another year of work to complete all of the pieces of the project and it was ready to be unveiled. In May of 2008, 101 years after the original film was shot, an audience of 400 people sat down to watch the first public showing of the VHS production of City Reflections.

© All rights reserved.

© All rights reserved.

April 21, 2018

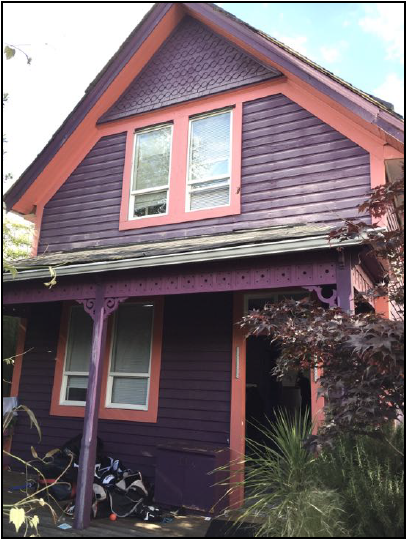

Mount Pleasant’s Coulter House

Did you see the article in the Georgia Straight last week headlined “Modest Vancouver heritage home proposed to be reborn as boutique restaurant”? The accompanying picture showed a funky purple Victorian house with pink trim and the kind of cool architectural doodads, that we don’t see anymore.

Sweet, I thought. Instead of pulling down another heritage house we’re going to repurpose it into a restaurant. And then I looked at the design rendering.

Yikes!

The funkiness has been stripped out along with the colour—it’s now white with a touch of grey—like a piece of public art. I guess someone thought a red door would be a good idea so restaurant patrons could find the entrance. The rest of the house is swallowed up by a six-storey, glassy non-descript building.

This is why people hate facadism.

The house has sat at 35 West 6th Avenue between Manitoba and Ontario Streets for going on 120 years.

The goal for the Vancouver Heritage Commission, says Michael Kluckner, was to try and retain some memory “however marginally,” of the working-class housing that once covered that area.

I sat on the Heritage Commission for North Vancouver District for four years and I understand the frustration of trying to save heritage and its many compromises. But in a case like this I think we have to ask—really?—what’s the point?

Mount Pleasant from City Hall in 1956. Coulter House is in the top right of the frame. Courtesy CVA Sc P144.2

Mount Pleasant from City Hall in 1956. Coulter House is in the top right of the frame. Courtesy CVA Sc P144.2It seems a sad end for a house that gave sanctuary to a century of working class people. William Henry Coulter, who built the house was a millworker. Later owners include a tinsmith, an upholsterer and a shoe store clerk. In 1912, Sidney Boutall built and ran a neighbourhood grocery store in the front of the property and had the forethought to include sleeping quarters. The store lasted until 1978, and for much of its existence was known as the Sixth Avenue Grocery.

This working-class house had a paper makeover and was listed for $1.4 million in 2011.

According to the Statement of Significance the house is ‘important for its historic connection to Mount Pleasant’s early development, for its survival as a residence in what is now an industrial area, for its working-class occupancy history and for its design.”

Nope, not seeing any of that being salvaged in the new design—it’s taken away the context.

But I guess if people want to really know what Mount Pleasant looked like, restaurant customers can just look across the street. Amazingly, there are several of the original homes, still housing people that show what Mount Pleasant used to look like when the streetcar rattled along Main Street.

Houses along West 6th Avenue in 2011, from Vanishing Vancouver the Last 25 Years. Courtesy Michael Kluckner.

Houses along West 6th Avenue in 2011, from Vanishing Vancouver the Last 25 Years. Courtesy Michael Kluckner.As Patrick Gunn at Heritage Vancouver says: “At times, the sum is greater than the parts.”

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

April 14, 2018

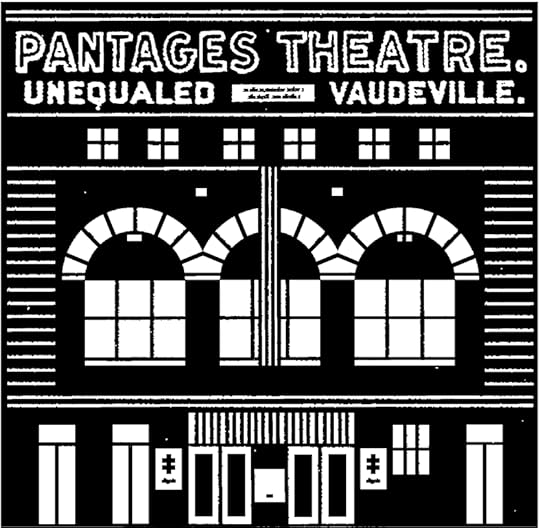

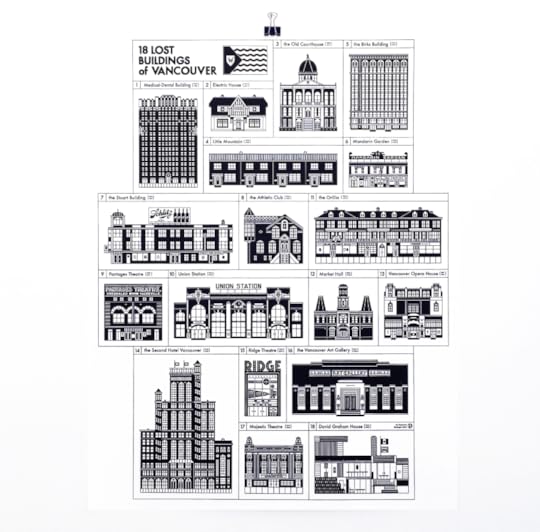

Our Missing Heritage: 18 Lost Buildings of Vancouver

Originally from Edmonton, Raymond Biesinger is a Montreal-based illustrator whose work regularly appears in the New Yorker, Le Monde and the Guardian.

In his down-time, Biesinger is drawing his way through nine of Canada’s largest cities. He’s just finished Vancouver, the sixth city in his Lost Buildings series, and his print depicts 18 important heritage buildings that we’ve either bulldozed, burned down or neglected out of existence.

Biesinger uses geometric shapes to ‘build’ his building illustrations

The lost buildings include iconic ones such as the Georgia Medical-Dental building, the second Hotel Vancouver, and the Birks Building, but it also includes the Stuart Building, the Orillia, Electric House, the Mandarin Garden and Little Mountain–described as “British Columbia’s first and most successful social housing project” (there’s a full list below).

#16 Vancouver Art Gallery (1931-1965) Courtesy CVA 99-4061

#16 Vancouver Art Gallery (1931-1965) Courtesy CVA 99-4061Biesinger spent loads of hours researching photos from different online archival sources, as well as local journalists and blogs such as mine.

Unfortunately, there is no shortage of amazing buildings missing from our landscape for Biesinger to choose from and narrowing down his list was a challenge. He looked for buildings that were socially, architecturally or historically important.

Union Station designed by Fred Townley in 1916. and demolished in 1965. Illustration by Raymond Biesinger

Union Station designed by Fred Townley in 1916. and demolished in 1965. Illustration by Raymond Biesinger“I tried to get a selection of buildings that had a variety of social purposes—so residences, towers, commercial spaces, athletic spaces, transportation spaces, entertainment and that kind of thing,” he says. “At one point my Vancouver list had mostly theatres on it, because there were so many gorgeous old Vancouver theatres.”

Two of the biggest losses for Vancouver, in Biesinger’s opinion, was the Vancouver Art Gallery’s art deco building on West Georgia and the David Graham House in West Vancouver designed by Arthur Erickson in 1963.

David Graham House in West Vancouver. Designed by Arthur Erickson in 1963

David Graham House in West Vancouver. Designed by Arthur Erickson in 1963“It just blew my mind that this west coast modern house was demolished in 2007. Someone bought it for the lot and knocked it down so they could put up a McMansion,” he says. “The VAG building from 1931 is incredible. When I found that it was love at first sight. The supreme irony that it was knocked down and is currently a Trump Tower is insane.”

Biesinger has a degree in history from the University of Alberta, and between 2012 and 2016 was at work on a series that showed 10 different Canadian cities during specific points in their history—for example—Montreal at the opening of Expo ’67 and Vancouver during the opening of the Trans-Canada Highway in 1962.

Vancouver in 1962. Courtesy Raymond Biesinger

Vancouver in 1962. Courtesy Raymond Biesinger“What really fascinated me was the buildings that weren’t standing any more, and that people were surprised that existed,” he says.

So how does Vancouver stack up against heritage losses in Montreal, Toronto, Ottawa, Edmonton and Calgary?

”The worse a city’s record for preserving old buildings, the more enthusiastic people are about these prints,” he said. “Vancouver has done a poor job. I think the economic currents running through Vancouver are just insane and not in favour of preserving the old.”

The Stuart Building sat at the entrance to Stanley Park. It was demolished in 1982. Photo Courtesy Angus McIntyre

The Stuart Building sat at the entrance to Stanley Park. It was demolished in 1982. Photo Courtesy Angus McIntyreThe 18 Lost Buildings:

1. Georgia Medical-Dental building (1928-1989)

2. Electric House (1922-2017)

3. The old Courthouse (1888-1912)

4. Little Mountain (1954-2009)

5. Birks Building (1913-1974)

6. Mandarin Garden (1918-1952)

7. The Stuart Building (1909-1982)

8. Vancouver Athletic Club (1906-1946)

9. Pantages Theatre (1907-2011)

10. Union Station (1916-1965)

11. The Orillia (1903-1985)

12. Market Hall (1890-1958)

13. Vancouver Opera House (1891-1969)

14. The second Hotel Vancouver (1916-1949)

15. Ridge Theatre (1950-2013)

16. the Vancouver Art Gallery (1931-1985)

17. Majestic Theatre (1918-1967)

18. David Graham House (1963-2007)

For more posts on Vancouver’s missing heritage: Our Missing Heritage

Biesinger’s Lost Building posters are $40 and you can order through his website: fifteen.ca

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

April 7, 2018

A Short History of Cates Park

If you’re looking for something a little different, skip Quarry Rock, Honey’s Donuts and the ice-cream shops of Panorama Drive and head to Cates Park.

There’s a ton of history spread over the six kilometres of waterfront park.

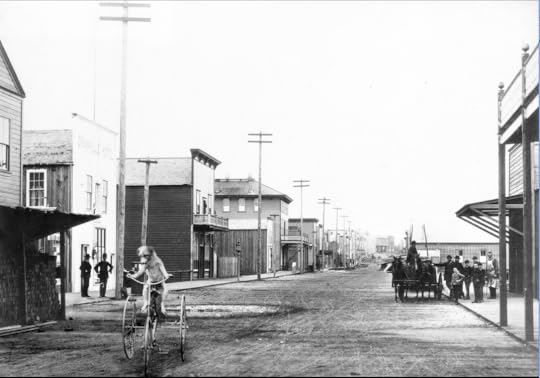

Robert Dollar Sawmill in 1918. Photo courtesy VPL 20574

Robert Dollar Sawmill in 1918. Photo courtesy VPL 20574In 1916 a San Francisco-based lumber baron named Robert Dollar bought 100 acres and built a huge mill at the bottom of what’s now Dollar Road. There were no roads leading into Dollarton, no bridge spanning the Second Narrows, and no regular ferry service. Dollar built a wharf for his ships and a town for his employees with a post office, gardens, community hall, church and school. He rented houses to his employees for $15 a month.

The Dollar Mill operated until 1942.

Worker’s housing at Robert Dollar’s sawmill in 1939. Photo courtesy VPL 6535

Worker’s housing at Robert Dollar’s sawmill in 1939. Photo courtesy VPL 6535See that strange cement structure in Little Cates Park? My kids thought it was a castle and used to play in it when they were little. Although it makes a great fort, it’s actually the remains of a waste burner and the only thing left to tell the story of the lumber mills that operated around Dollarton in the early part of the 20th century.

The mill changed hands a few times and closed permanently in 1929 at the onset of the Depression.

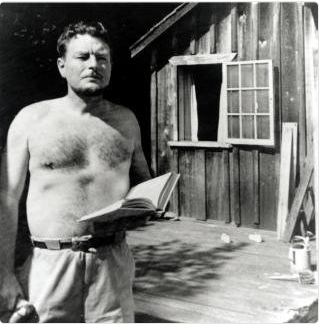

Malcolm Lowry outside his Dollarton shack

Malcolm Lowry outside his Dollarton shackSquatter shacks started to pop up around Roche Point in the 1930s, and by the 1950s there were close to a hundred along the waterfront, many built on pilings and erected from wood and other materials scavenged from the beach. There was no running water, no electricity and no heat. The most famous of the squatters was Malcolm Lowry, author of Under the Volcano among others. His shack was one of the last holdouts–all traces of the shacks were destroyed by 1957.

If you look out over Burrard Inlet you can still see the same view that Lowry looked out on more than 50 years ago—the Burnaby oil refinery that he hated—has been there since 1932.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

March 31, 2018

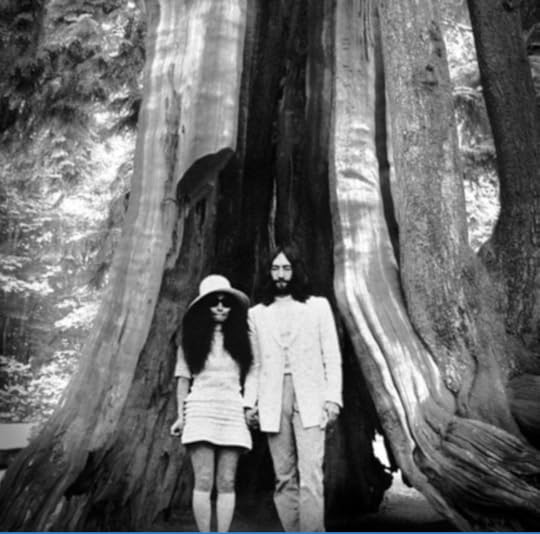

The Mysterious Visit of John and Yoko to Stanley Park

Several years ago, I came across an art project by the Goodweather Collective that re-imagined a Vancouver in which the City had left select old growth trees in those roundabouts that dot the city’s residential neighbourhoods. Their photoshop work was convincing and it was jarring seeing our familiar urban landscape dotted with unfamiliar giant trees. I had been doing my Past Tense Vancouver blog on Tumblr and thought it would be fun to do some photoshopping of my own for April Fools’ Day.

The first one I did was John Lennon and Yoko Ono at the Hollow Tree. This one remains the most successful in terms of the number of likes it got, and also the number of times I’ve seen someone post it to Facebook without any mention that it was fake. I used the image from the cover of John and Yoko’s Wedding Album, thinking it was a familiar enough image that wouldn’t fool too many people, but alas, no. It put me in a bit of an awkward position, since I spend a fair bit of time sorting out what I believe to be the truth of Vancouver’s past; here I was being a purveyor of fake history.

The next fake image I did was a dog riding a tricycle down Water Street in 1887. This one actually may have happened, though I have no proof.

For the last one, I riffed on all of the unsubstantiated stories of Jimi Hendrix’s time in the Vancouver. I photoshopped Jimi’s face onto a bonneted lady in a car visiting Stanley Park. Everyone in the car is smiling and appear to be in on the joke except for a boy with a puzzled expression looking at Jimi. This one was an obvious fake, but the original photo had its own weirdness. On the left is what appears to be another man in women’s garments that I swear I had nothing to do with.

Lani Russwurm is a Vancouver historian who has been blogging for over a decade as Past Tense Vancouver on Tumblr and WordPress , and more recently for Forbidden Vancouver walking tours. He is the author of Vancouver Was Awesome: A Curious Pictorial History and lives and works in the Downtown Eastside.

Source photos:

Hollow Tree, 1905, City of Vancouver Archives, #Port P1257

Britannia, ca. 2010 by the Goodweather Collective

Water Street, 1887, City of Vancouver Archives #Str N58

March 24, 2018

Vancouver’s Monkey Puzzle Tree obsession

In 2012, I wrote a book called Sensational Victoria and one of my favourite chapters was Heritage Gardens. I visited and then wrote about large rich-people’s gardens like Hatley Park, and smaller ones like the Abkhazi Garden on Fairfield road built on the back of a love story. There was Carole Sabiston’s beautiful garden on Rockland Avenue anchored by a 100-year-old purple lilac tree, and the garden Brian and Jennifer Rogers created around their century-old Samuel Maclure designed horse stable. (Brian is the grandson of BT Rogers, the Vancouver sugar king, and another ardent gardener).

Nellie McClung at her Ferndale Road home in 1949. Courtesy Saanich Archives

Nellie McClung at her Ferndale Road home in 1949. Courtesy Saanich ArchivesOn the back cover of the book, there’s a photo of Nellie McClung standing in front of a giant monkey puzzle tree at the house she retired to at Gordon Head in 1935.

Lurancy Harris, the first female police officer in Canada, built her house on Venables in 1916. When I went to photograph it, the now two-storey house was dwarfed by a monkey puzzle tree that she’d planted in her front garden.

Lurancy Harris built 1836 Venables in 1916 and planted herself a monkey tree.

Lurancy Harris built 1836 Venables in 1916 and planted herself a monkey tree.I’ve always had a thing for monkey puzzle trees—they seem to go particularly well with turrets, old houses and great stories. But I’ve never given them much thought until I was chatting with Christine Allen this morning about her upcoming talk for the Vancouver Historical Society next month. Christine—another Australian transplant—is a master gardener. She tells me that there was a huge craze for monkey puzzles trees here in the 1920s and 1930s.

“People were very proud of their monkey puzzle trees. It was so Victorian, they loved that kind of odd ball stuff,” she says. “There is a tiny post-war bungalow in my neighbourhood (Grandview) where somebody planted two massive ones on the south side of the house. That house gets no sun ever.”

Bowen Island Inn in the 1930s with a massive monkey puzzle tree. Courtesy Vancouver Archives

Bowen Island Inn in the 1930s with a massive monkey puzzle tree. Courtesy Vancouver ArchivesChristine says that another reason why these South American natives were so popular is because of Vancouver’s mild climate that allows us to grow anything from arctic tundra plants to palm trees.

But it’s not just people, towns are proud of them to. The tiny town of Holberg on Vancouver Island boasts the world’s tallest monkey puzzle tree. I have no idea how tall it is now, but in 1995 it was measured at 77 feet—that’s higher than a seven-storey building.

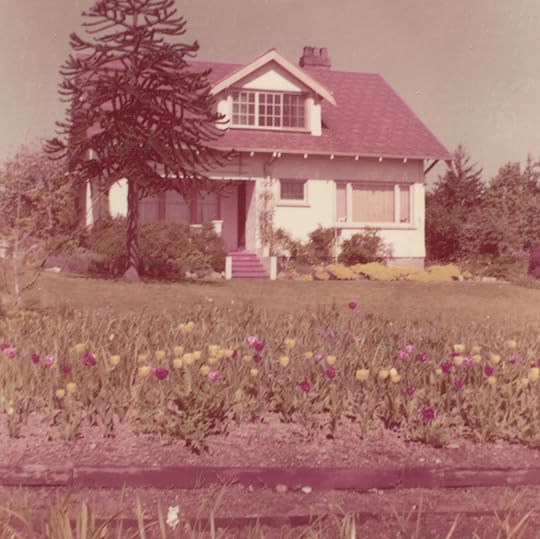

Nellie McClung’s home was known as Lantern Lane after the books she wrote in her upstairs study. Courtesy Saanich Archives, 1960

Nellie McClung’s home was known as Lantern Lane after the books she wrote in her upstairs study. Courtesy Saanich Archives, 1960© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

March 17, 2018

Finding the Rhea Sisters

Courtesy Ital Decor

Courtesy Ital DecorI was driving along Hastings the other day when I saw a huge statue in the yard of Ital Decor in Burnaby. It looked suspiciously like one of the WW1 nurses that guarded the 10th floor of the Georgia Medical-Dental Building before it was imploded in 1989.

Mario Tinucci of Ital Décor, says the one in his yard is a fibreglass version that he cast from an original nurse, and made in 1990. It was the first of four that were replicated—the other three are attached to Cathedral Place, the Paul Merrick-designed tower that replaced the GM-DB.

The three “Sisters of Mercy” were affectionately known as the Rhea Sisters—Gono, Pyor and Dia.

Ital Decor , 6886 Hastings Street, Burnaby

Ital Decor , 6886 Hastings Street, BurnabyAccording to newspaper articles, the eleven-foot-high terra cotta nurses, designed by Joseph Francis Watson, weighed several tonnes each and were in rough shape when they came down. The cost to fix them was upwards of $70,000 each.

Instead, developer Ron Shon donated all three to the Vancouver Heritage Foundation. He also donated some of the terra cotta animals, spandrel panels and chevron mouldings from the main entrance, and the secondary arch (the main one is in the Bill Reid Gallery which is currently closed for renovations).

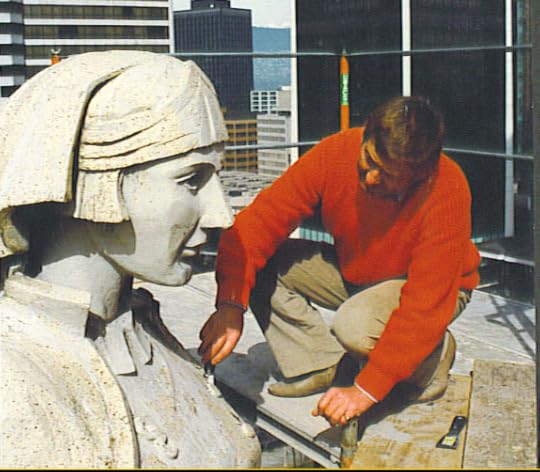

Photo courtesy Ital Decor

Photo courtesy Ital DecorIn 1992, the VHF had their first fundraiser at the Museum of Vancouver’s parking lot and sold off pieces of the GM-DB’s terra cotta.

Maurice Guibord, who was manager of community affairs for the MoV, paid $100 for a piece of the archway, now in his garden, and which came with Certificate of Authenticity #92.

The VHF donated one of the nurses to the MoV in 2000, and later sold the two original nurses to Discovery Parks at UBC.

Nurses on the Technology Enterprise Facility Building at UBC. Courtesy UBC

Nurses on the Technology Enterprise Facility Building at UBC. Courtesy UBCWendy Nichols, curator of collections at the MoV, says their nurse is at UBC on a long-term loan agreement. I’m told all three original nurses are attached to the Technology Enterprise Facility 111 building completed in 2003, although only two are visible in this photo.

I never saw the GM-DB, and neither did Maurice, but on Thursday he, Tom Carter and I took a field trip to Cathedral Place. Tom prefers Cathedral Place to the original art deco building because he says the back was unfinished, and the building was only ever designed to be viewed from the front.

Maurice and Tom inside the Cathedral building with the mystery head

Maurice and Tom inside the Cathedral building with the mystery headRobin Ward described the GM-DB’s “Mayan/Hollywood style lobby” in 1988. “It’s like a film set for a bank robbery in Mexico City,” he wrote.

I get what he means. The lobby in Cathedral Place is very similar to the Marine Building complete with brass doors on the elevators. (The Marine Building and the GM-DB were both designed by McCarter and Nairne architects).

The Hotel Vancouver from the courtyard. Cathedral Place on the left, Christ Church Cathedral on the right. Eve Lazarus photo.

The Hotel Vancouver from the courtyard. Cathedral Place on the left, Christ Church Cathedral on the right. Eve Lazarus photo.It’s easy to appreciate Merrick’s skill when you get into the monastery-like courtyard that joins Cathedral Place to Christ Church Cathedral and the Bill Reid Gallery. He has used a similar CP Hotel-style roof to complement the Hotel Vancouver’s copper lid, and gothic touches and cloisters to connect the buildings together.

Now the questions remain:

Is the head that is displayed at Cathedral Place terra cotta or fibreglass (we couldn’t tell) and where did it come from? (There were three original nurses that are now at UBC and four fibreglass moulds—three are attached to Cathedral Place and one is at Ital Décor)

What is the connection between the Technology Enterprise Facility Building and BC’s nursing history?

The Georgia Medical-Dental Building in 1973. Courtesy CVA 70-28

The Georgia Medical-Dental Building in 1973. Courtesy CVA 70-28© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

March 10, 2018

The Photography of Bob Cain

I had the pleasure of chatting with Bob Cain this week and discovering his beautiful photographs.

The interurban to Marpole. Bob Cain photo, 1957

The interurban to Marpole. Bob Cain photo, 1957Bob grew up in Marpole, at a time when a swing bridge joined Marpole to Sea Island (it was dismantled in 1957 after the Oak Street Bridge opened).

“Marpole was a small town like Kerrisdale and Kitsilano,” he says. “They were just a series of small towns separated by bush and connected by interurban and trams. They had their own mayors, their own celebrations, and they used to have a May Day parade every year.”

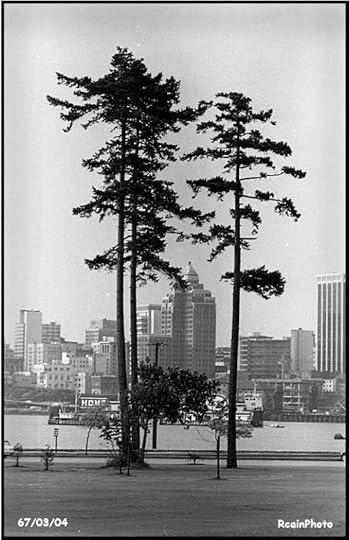

The Vancouver skyline and the Marine Building. Bob Cain photo, 1967

The Vancouver skyline and the Marine Building. Bob Cain photo, 1967When Bob was about 12, he had a morning paper route for the Vancouver News Herald. “I was getting up at 4:00 am, riding down to the Safeway on Granville Street where the papers were tossed in bundles onto the sidewalk and we would count them out and load up our bikes,” he says. “I think I had 70 deliveries which I would finish just in time to go to school.”

When he decided to quit, his manager told him if he’d stay on for another month, he’d give him a camera. “It was a Brownie Hawkeye and my first really good camera.”

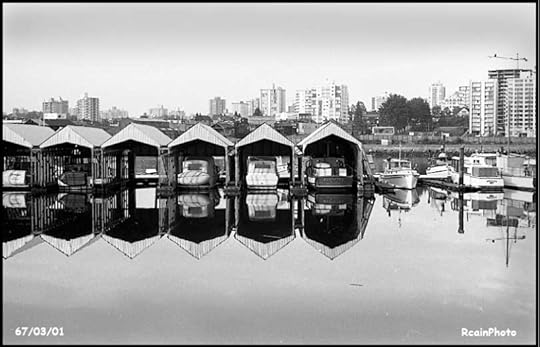

Boats in Stanley Park. Bob Cain photo, 1967

Boats in Stanley Park. Bob Cain photo, 1967What his manager didn’t tell him was the paper was going under and he didn’t want the bother of looking for another paperboy.

Now he had a “Baby Brownie,” Bob started to get more serious about photography. His family had moved into a Marpole fixer upper in the ‘50s that had a basement with a fully working darkroom. He took it over, shot, developed and printed photos as well as 8mm and 16mm reversible movie film.

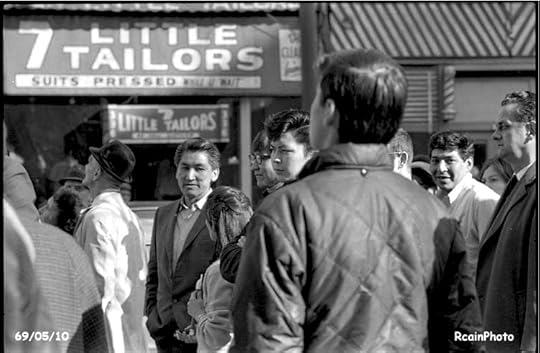

Bob Cain photo, 1969

Bob Cain photo, 1969In 1967, Bob was hired as a darkroom assistant with Focus Prints at 1255 West Pender Street. “Focus Prints was located up one set of stairs and down a long corridor all the way to the back of the building. The office and workroom had gorgeous views of the Burrard Inlet,” he says. (I worked in the same two-storey blue building in the 1980s for Business in Vancouver—now it’s a 15-storey condo building called The Views).

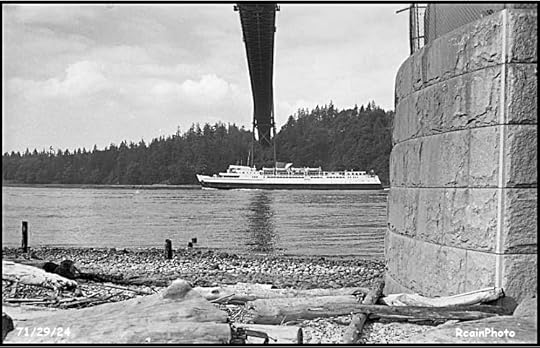

CPR ferry to Nanaimo. Bob Cain photo, 1971

CPR ferry to Nanaimo. Bob Cain photo, 1971Focus Prints mostly dealt with ad agencies in the area, and Bob’s main job was to making what he calls Azos. “Using a 5×7 camera we made line negs (black and white negs, no shades of grey) of the copy sent to us.”

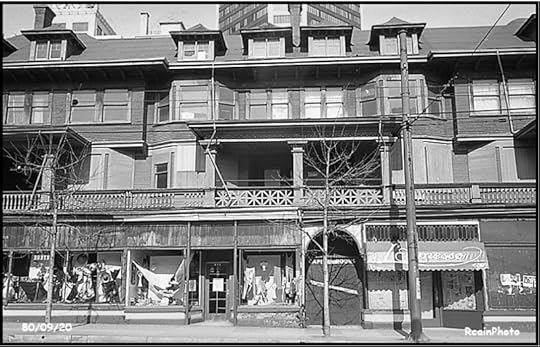

The Orillia on Robson. Bob Cain photo, 1980

The Orillia on Robson. Bob Cain photo, 1980He moved to Hornby Island in the 1970s and became the island’s official photographer—taking passport photos, recording weddings, and marking other events such as art show openings with his camera. He’s retired now, but still taking photos and he’s been adding to his website since 2006.

Britta Dansereau and Ron Schulman. Bob Cain photo 1990

Britta Dansereau and Ron Schulman. Bob Cain photo 1990These days, he gets to Vancouver less and less. “I don’t like Vancouver anymore it’s outgrown itself,” he says.

I asked Bob his favourite photographer. Foncie, he said.

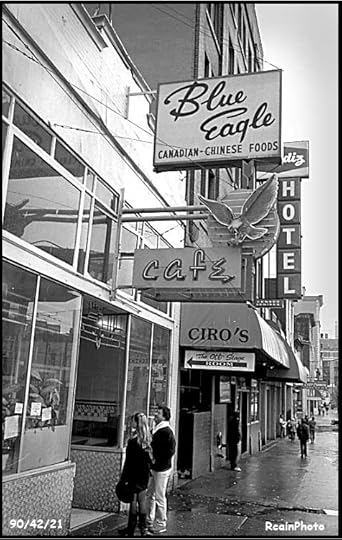

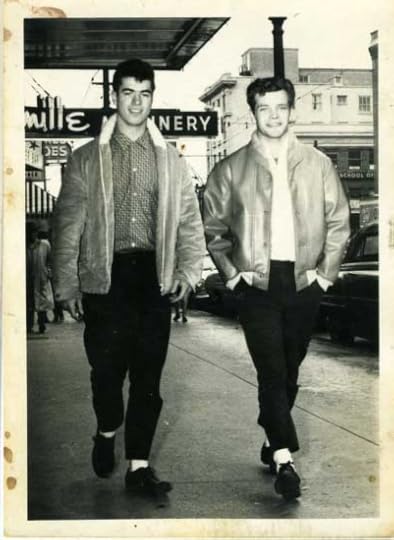

Ron Schulman and Bob Cain. Foncie photo, 1961

Ron Schulman and Bob Cain. Foncie photo, 1961© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.