Eve Lazarus's Blog: Every Place has a Story, page 33

September 29, 2018

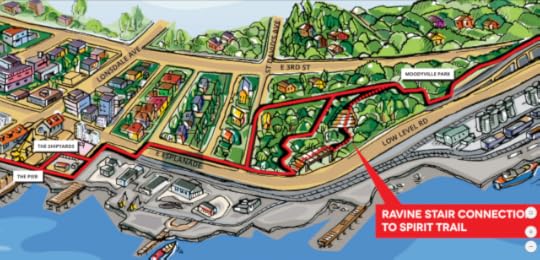

Along the North Shore’s Spirit Trail – Moodyville to Lonsdale Quay (part 2)

At the end of last week’s blog, I left you at Moodyville Park, the only thing left of a once thriving town. Now hop back on your bike and follow the signs west along First Street East—and be careful of those construction trucks! I imagine in another year or so this area will be unrecognizable, but occasionally you’ll see a bungalow–the lone standout in a sea of rubble.

North Vancouver war-time housing 1943. Courtesy BC Archives 41451

North Vancouver war-time housing 1943. Courtesy BC Archives 41451Some of those holdouts were built during WW2 when Wartime Housing, a crown corporation, built tracts of neat cottages for shipyard workers. According to North Vancouver Museum and Archives, rents averaged $20 per month plus $1.35 for water services. The website says about 100 wartime houses still survive, but I’m not confident how current that is.

You’ll see signs taking you down the squiggly path and onto Alder Street and along the working waterfront.

PGE moved to its temporary home on the Spirit Trail in 2014

PGE moved to its temporary home on the Spirit Trail in 2014The old Pacific Great Eastern (PGE) Railway-North Van’s first train station—is boarded up and stuck behind a chain link fence until a new home is found for it (I hope).

On January 1, 1914, the PGE began service from this station at the foot of Lonsdale Avenue to Dundarave. At the time the plan was to extend the tracks to Squamish, but that didn’t eventuate and the railway only went as far as Horseshoe Bay. The railway service ended in 1928, and the station became a bus depot, and then was used as offices until it was moved to Mahon Park in 1971. It was spiffied up and returned to its home at the foot of Lonsdale in 1971, and moved to its current location in 2014.

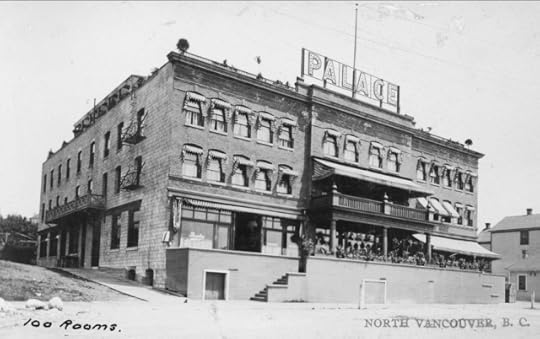

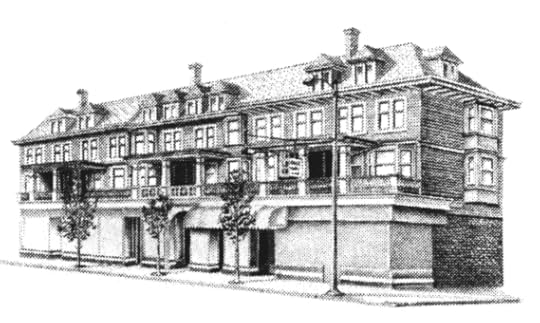

Palace Hotel in 1909. Courtesy NVMA 8155

Palace Hotel in 1909. Courtesy NVMA 8155The Spirit Trail takes you along Esplanade and down St. George’s to Victory Ship Way. If you look up the street you’ll see a 15-storey condo tower at East 2nd called the Olympic. In 1906 Lorenzo Reda built a brick hotel in that spot. Within two years, he added more rooms and a dance hall, and in 1908 the Palace Hotel boasted that it was “the only hotel in British Columbia with a roof garden.” Reda died in 1928. The hotel became the Olympic, and by the ‘70s (when it was known locally as the “Big O”), it was hosting rock bands and strippers. It was demolished in 1989.

The Shipyards in 1948, courtesy CVA Wat P58

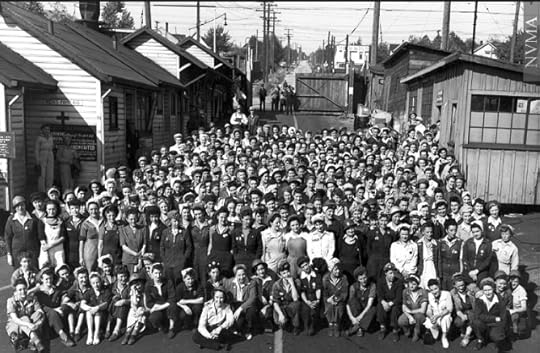

The Shipyards in 1948, courtesy CVA Wat P58.Aside from a couple of the old shipyard buildings and artifacts, most of the buildings have been torn down and replaced with condos. This was a hopping place during WWII, and Burrard Dry Docks was the first to hire women in significant numbers and pay them decent wages.

Women workers at Burrard Dry Docks, 1945. Courtesy NVMA 1421

Women workers at Burrard Dry Docks, 1945. Courtesy NVMA 1421And some of you may remember the Erection Shop that sat at the bottom of St. Georges until political correctness made the shipyards take the sign down for Expo 86.

Clay Mccallum-Dubois photo, ca.1979

Clay Mccallum-Dubois photo, ca.1979We’ll start at Shipyards Coffee at Lonsdale Quay next week for a chat about the history of the area.

If you missed the first leg see the North Shore’s Spirit Trail – Moodyville

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

September 22, 2018

The North Shore’s Spirit Trail – Moodyville (part 1)

In May 2014, the City of North Vancouver inked a deal with the Squamish Nation and moved a step closer to realizing the dream of building a 35-kilometre waterfront trail that would wind its way from Deep Cove to Horseshoe Bay. The mostly finished portion of the Spirit Trail runs from Sunrise Park (just above Park and Tilford Gardens) to 18th Street in West Vancouver–(just past John Lawson Park). The ride (or walk) along the finished portion is about 20 km return.

The Moodyville Park section was completed in 2015. The trail includes an impressive overpass to Heywood Street, a mini-suspension bridge, public art, and some now fading public markers. You’ll have to reach deep down into your imagination, because the only thing left of Moodyville is a small park with some signage surrounded by a lot of building activity.

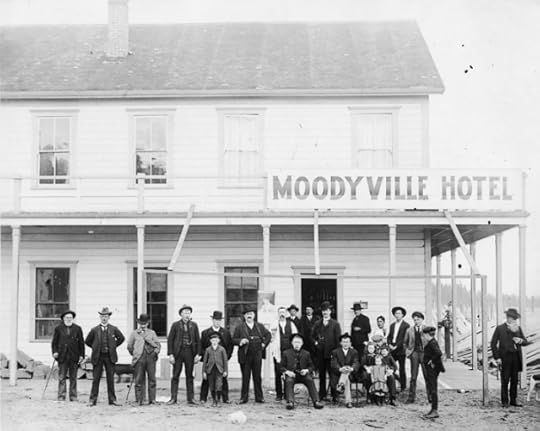

A two-storey hotel opened in 1883 and it was reportedly “a comfortable and exceedingly well-managed” operation, with a bar stocked with top wines and liquors, and where “drunkenness was unknown.” The Columbian, photo NVMA 1900

A two-storey hotel opened in 1883 and it was reportedly “a comfortable and exceedingly well-managed” operation, with a bar stocked with top wines and liquors, and where “drunkenness was unknown.” The Columbian, photo NVMA 1900Up you go over the new overpass, and a great view of the working waterfront that takes you right into Moodyville, once a thriving town built entirely around lumber. Settled in the early 1860s, the town was completely distinct from the rest of North Vancouver with a business district that included a library, Masonic lodge, school, jail and cookhouse situated where the railway tracks and grain elevators are today. The mill was at the foot of what is now Moody Avenue, and a wooden wharf extended from the mill out over deep water. The town even had its own ferry service.

William Nahanee (with laundry bag) and a group of longshoremen on the dock of Moodyville Sawmill in 1889. CVA Mi P2

William Nahanee (with laundry bag) and a group of longshoremen on the dock of Moodyville Sawmill in 1889. CVA Mi P2While the workers were comprised of several different races who could trace their origins back to Europe, Asia, the Pacific Islands “Kanakas,” Latin America and the West Indies, lived in segregated housing; the wealthy lived in “Nob Hill” a nod to San Francisco’s prestigious neighbourhood.

The most prestigious house was Invermere, known as the “Big House” and built in the late 1870s for Hugh Nelson a partner in the Moodyville Sawmill Company (later Lieutenant Governor of BC). Lumberman John Hendry bought Invermere and lived there for a time. His son-in-law Eric Hamber, another Lieutenant Governor of BC, demolished the house after his death. The replacement house is at 543 East 1st Street.

The Big House in 1881. Courtesy NVMA

The Big House in 1881. Courtesy NVMAElectricity came to Moodyville in 1882, a full five years before Vancouver and the electric lights reflected all the way across the waters to Hastings Mill in Vancouver. Moodyville was the first town site north of San Francisco to sport electric street lights.

By 1898 the Mill’s fortunes had peaked and in 1901 it closed. People moved away in search of work, and business activity shifted to the waterfront at the foot of Lonsdale Avenue. Moodyville officially became part of North Vancouver in 1925.

“Moodyville was the largest, oldest, most prosperous and certainly most decorous settlement on the Inlet. It had a population of several hundred, all respectable families, with tidy homes strung along well-laid out streets up the hillside from Moody’s mill.” Photo ca.1890 CVA Mi P22

“Moodyville was the largest, oldest, most prosperous and certainly most decorous settlement on the Inlet. It had a population of several hundred, all respectable families, with tidy homes strung along well-laid out streets up the hillside from Moody’s mill.” Photo ca.1890 CVA Mi P22The Low Level Road, constructed two years later, paralleled the railway line. Much of the hillside was scraped away and re-deposited as fill on the tidal flats to reclaim 15 acres (6 hectares). Midland Pacific was first to locate on the fill and opened a grain elevator in 1928. The area known as Nob Hill was subdivided, war-time housing followed, and a housing development called Ridgeway Place sold in the late 1950s.

Today Moodyville is just one big land assembly parcel for sale

Today Moodyville is just one big land assembly parcel for saleWith thanks to the North Vancouver Museum and Archives for letting me work on their Water’s Edge Exhibit in 2016.

Next week: Riding the Spirit Trail from Moodyville to Lonsdale Quay

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

September 15, 2018

Art, History and a Mission

In 2016, the Vancouver Historical Society was contacted by the Port of Vancouver and asked what we’d like to do with a three metre-high sculpture made from BC granite that had been sitting on their land at the foot of Dunlevy Street since a previous board commissioned it 50 years before.

In 2016, the Vancouver Historical Society was contacted by the Port of Vancouver and asked what we’d like to do with a three metre-high sculpture made from BC granite that had been sitting on their land at the foot of Dunlevy Street since a previous board commissioned it 50 years before.

Since it was the first that any of us had heard of it, we did some research and found out that in 1966, the VHS had contributed funds towards a $4,500, three-piece sculpture created by Gerhard Class to mark the 100th anniversary of Hastings Mill, which for a time, was the nucleus of Vancouver.

We took a field trip to check it out. It’s a beautiful piece of art, and a shame that no one really gets to see it.

The problem for the port was that the sculpture sat in a garden behind the Flying Angels Club, built in 1906 as the headquarters for the BC Mills Timber and Trading company and a fixture of Hastings Mills.

In 1966, the National Harbours Board occupied the house and did so until the 1970s when the Mission for Seafarers, which runs the Flying Angels Club, took possession.

Up until 9/11, the Mission was easily accessible and surrounded by gardens that led to the waterfront. Post 9/11 madness, the Port is wrapped in a chain link of security which has marooned the house in a kind of cul-de-sac.

Over the years, the garden shrank as the port expanded. When we were contacted in 2016, the Port was planning to install shore-power transformers where the sculpture sat. To give the Port of Vancouver’s Carol Macfarlane, a huge amount of credit, she went to enormous lengths to find the sculpture a new home.

“It reminded me of an iceberg,” she said. “The monument is 8.5 ft. tall, but the underground is over three feet high and seven feet wide.”

And, when we realized the sheer lunacy of having to work with three levels of government to make the sculpture more accessible somewhere else, we opted to move it to the front of the house.

It’s not easy, but please go visit this sculpture. Maybe drop in and visit the Mission to Seafarers while you are there. Perhaps even drop off some books or games or clothes that you no longer need. They’ll be most grateful.

Thanks to Carol Macfarlane, project manager, Port of Vancouver for the photos

September 8, 2018

YVR: Fifty Years Ago

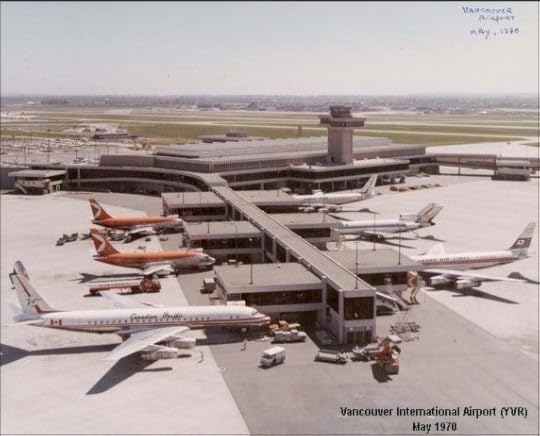

On September 10, 1968 the Vancouver International Airport opened a spanking new terminal building to handle all domestic, US and international flights. It was one of the few airports where aircraft could pull up to gates attached to the terminal and where passengers could load and unload via a bridge.

On September 10, 1968 the Vancouver International Airport opened a spanking new terminal building to handle all domestic, US and international flights. It was one of the few airports where aircraft could pull up to gates attached to the terminal and where passengers could load and unload via a bridge.

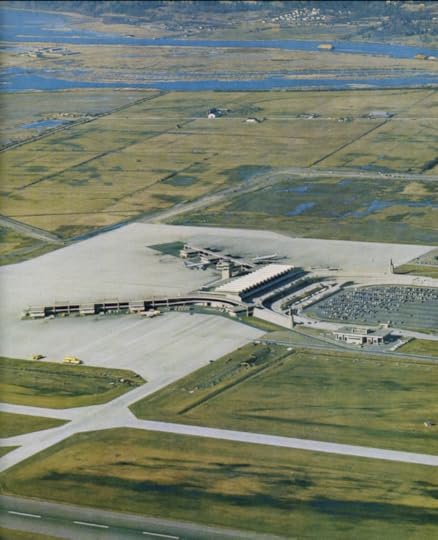

YVR 1960s expansion of runways and taxiways. Courtesy Vancouver Airport Authority

YVR 1960s expansion of runways and taxiways. Courtesy Vancouver Airport AuthorityThe building was designed by Zoltan Kiss of Thompson Berwick Pratt, the firm that served as an incubator for such other up-and-comers as Arthur Erickson, Ron Thom, Barry Downs and Fred Hollingsworth and designed buildings such as the game-changing BC Electric building on Burrard Street in 1957.

Courtesy The Netletter

Courtesy The NetletterThe terminal had the modern design, clean lines and open spaces common to mid-century architecture at the time. It screamed jet-setting technology and speedy travel.

The new terminal building at YVR taken shortly before it opened. Courtesy Vancouver Airport Authority

The new terminal building at YVR taken shortly before it opened. Courtesy Vancouver Airport AuthorityIf you’ve taken a plane from Vancouver to any other point in Canada—you’ve walked through this terminal. You’ve also likely noticed the two large air-intake towers that flank it. These concrete towers were an engineering feat back in 1968 and replaced the old system which had the air intake in the roof. When the wind would blow the wrong way, employees and passengers would complain about the overpowering smell of aviation fuel.

Courtesy Vancouver Airport Authority. YVR 1960s

Courtesy Vancouver Airport Authority. YVR 1960s“I remember how large and modern it was compared to the old (now South) terminals,” says Angus McIntyre. “You could drive your car up to the departure level, park and pay 25 cents at a meter. Hah!”

YVR officially opened in 1931 when the City of Vancouver invested $600,000 in a runway and a small wood framed building topped by a control tower after US aviator Charles Lindbergh refused to visit because there was “nothing fit to land on.”

YVR 1958. Photo courtesy Bob Cain

YVR 1958. Photo courtesy Bob CainBig changes happened in the 1960s after the City sold the Airport to the Department of Transport. By 1968 the airport sat on more than 4,000 acres of land, and the terminal building, which cost $32 million, served close to two million passengers in its first year of operation.

Half a century later, more than 24 million passengers pass through YVR each year.

And, while air travel today generally sucks, the good news is that not one person died in an accident on a commercial passenger jet last year —making 2017 the safest year ever.

Top photo: From “Through Lion’s Gate,” a 1969 Greater Vancouver Real Estate Board publication.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

September 1, 2018

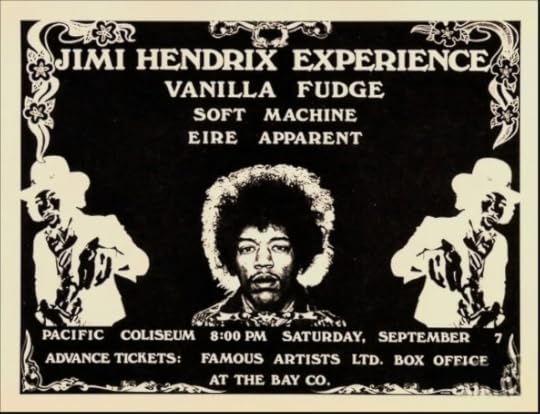

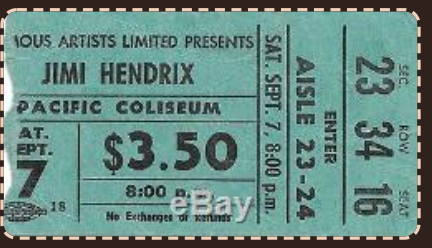

Jimi Hendrix Plays the Pacific Coliseum—September 7, 1968

This is an excerpt from Sensational Vancouver.

On September 7, it will be 50 years since Jimi Hendrix played the Pacific Coliseum. Four years after the Beatles and 11 years after Elvis Presley played Empire Stadium and changed music forever. The difference was that Jimi had a Vancouver connection—his grandmother Nora Hendrix, a one-time vaudeville dancer who moved to Vancouver in 1911 with her husband Ross Hendrix, a former Chicago cop and raised three children. Al, the youngest moved to Seattle at 22, met 16-year-old Lucille, and Jimi was born in 1942.

Nora Hendrix lived at 827 East Georgia between 1938 and 1952. Photo: CVA 786-4736 1978

Nora Hendrix lived at 827 East Georgia between 1938 and 1952. Photo: CVA 786-4736 1978According to Jimi Hendrix, the Man, the Magic, the Truth, a biography published in 2004, Jimi lived in 14 different places, including short stints in Vancouver. “I’d always look forward to seeing Gramma Nora, my dad’s mother in Vancouver, usually in the summer. I’d pack some stuff in a brown sack, and then she’d buy me new pants and shirts and underwear. I kept getting taller and growing out of all my clothes, and my shoes were always a falling-apart disgrace. Gramma would tell me little Indian stories that had been told to her when she was my age. I couldn’t wait to hear a new story. She had Cherokee blood. So did Gramma Jeter. I was proud of that, it was in me too.”

Dawson Annex, Burrard and Barclay Streets, demolished 1969. Courtesy VSB

Dawson Annex, Burrard and Barclay Streets, demolished 1969. Courtesy VSBAccording to the Vancouver School Board Archives and Heritage, in 1949, Jimi attended grade 1 at the West End’s Dawson Annex while living at Nora’s house on East Georgia. “It was a long distance to the school so he probably took the bus or streetcar since the fare was only five cents,” notes the VSB.

Shortly after Hendrix left the army in 1962, he hitchhiked 2,000 miles to Vancouver and stayed several weeks with Nora. He picked up some cash sitting in with a group at a club called Dante’s Inferno on Davie Street, now a gay nightclub called Celebrities.*

Now Celebrities Nightclub, 1022 Davie Street was called Dantes Inferno in the ’60s. Courtesy Places that Matter.

Now Celebrities Nightclub, 1022 Davie Street was called Dantes Inferno in the ’60s. Courtesy Places that Matter.Six years later, when Jimi Hendrix Experience played the Pacific Coliseum, one reviewer described the band as “bigger than Elvis.” Hendrix, dressed all in white, played hits such as “Fire,” “Hey Joe,” and “Voodoo Child.” At one point he acknowledged his grandmother, who sat in the audience, and launched into “Foxy Lady.”

In 2002, Vincent Fodera renovated the building at Union and Main Street and found dishes and a stove that he believes came from Vie’s Chicken and Steak House, part of Hogan’s Alley where Nora once worked as a cook. Seven years later Fodera opened a shrine for the dead rock star. Locals told him that Jimi used the space for rehearsals and sex.

Jimi Hendrix Shrine Main and Union Streets. James Gogan photo, 2013

Jimi Hendrix Shrine Main and Union Streets. James Gogan photo, 2013When Jimi played the Pacific Coliseum in 1968 he was 25. Just over two years later, the man widely recognized as one of the most creative and influential musicians of the 20th century was dead.

1022 Davie Street was designed by architect Thomas Hooper for the Lester Dancing Academy in 1911. Hooper also designed He designed the Victoria Public Library, and Munro’s Books Building in Victoria. And in 1912, the same year he designed Hycroft in Shaughnessy, Vancouver’s Winch Building and submitted plans for UBC, he designed Christina Haas’s, Cook Street brothel

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

August 25, 2018

The 1981 PNE Prize Home

In 1981, British Columbia was in the throes of a recession, house prices were plummeting, and first-time buyers were looking at interest rates of over 20%.

In 1981, British Columbia was in the throes of a recession, house prices were plummeting, and first-time buyers were looking at interest rates of over 20%.

Architectural offices were closing, and even a starchitect like Ron Thom was searching for clients. So, a commission to design the PNE prize home likely would have been very welcome.

Thom had cut his teeth designing more than 60 mid-century modern homes mostly on the North Shore, but had moved onto work on commercial buildings such as the BC Electric Building in Vancouver, and after he opened an office in Toronto, designed the Massey College, the Shaw Festival Theatre and the Toronto Zoo.

For the PNE he designed a bright and airy home of close to 4,000 square feet—more than twice the size of earlier prize homes. Behind the solid oak front door was a dramatic glass-roofed atrium which soared up from the courtyard entrance to the roof. Short flights of stairs led to the living areas, a self-contained master bedroom was placed at the top of the house and four bedrooms below. It was bright and airy, and likely frightening for people used to traditional houses with small rooms, two floors and a basement.

It was also quite complex to build and the cost went from $250,000 to $450,000, which didn’t include the Coquitlam lot which had been purchased as its designated resting place.

Batex Industries, the builder, ran into financial trouble and liens were placed on the house by several contractors, and by Thom.

2324 129B Street, South Surrey

2324 129B Street, South SurreyIn the end, winners Ray and Ruth Swift decided it “was the weirdest house” and PNE staff thought it too modern for the average family. The Swifts took $250,000 in cash, and Ron Thom’s PNE house sold for $2,500 and was shipped to a lot in South Surrey.

In 2018, it was valued at $2.6 million.

Top photo: Courtesy Vancouver Sun, 1981. Ralph Bower photo

For more on the PNE Prize home: The PNE – Party like its 1957 and 10 things you won’t see at the PNE this year

Source:

Elizabeth Mackenzie’s 2005 thesis “The PNE prize home—tradition and change.”

Sensational Vancouver

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

August 18, 2018

10 things you won’t see at the PNE this year

The PNE opens today at Hastings Park, and at 108, must be one of Vancouver’s oldest institutions. Not surprising it’s also changed a lot over the years. Some things will be missed and others not so much. Here are 10 things you won’t be seeing this year.

1. A brill trolley bus

1. A brill trolley bus

You won’t be taking a brill trolley bus to the fair. Angus McIntyre is pictured here on one that was detoured for the PNE parade at Hastings and Commercial in 1974. “There wasn’t always a switch or wire for these maneuvers, so we rode the rear bumper, held onto to a retriever with one hand, and pulled both poles down with the other,” says Angus, adding that this was done while travelling at speeds of up to 30 km/hr. Photo courtesy John Day.

The Challenger relief map, 1954 Courtesy CVA 180-5614

The Challenger relief map, 1954 Courtesy CVA 180-56142. The Challenger Relief Map and the B.C. Pavilion

The B.C. Pavilion was demolished in 1997 and the Challenger Relief Map of B.C. that occupied 1,850 square metres of floor space, was placed in storage at an Air Canada hangar at YVR. George Challenger and his family spent seven years building the map to topographical scale from fir plywood cut into 986,000 pieces. It was at the PNE for 43 years.

3. Babes in the Woods

3. Babes in the Woods

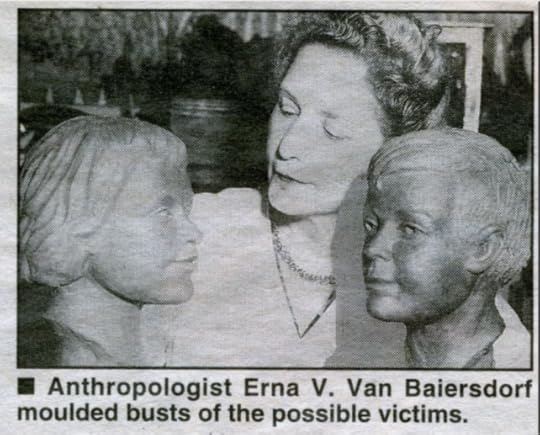

The Babes in the Woods was the name given to the skeletons of two little boys found in Stanley Park in 1953. Unbelievably, their tiny skulls were put on exhibition at the PNE and later at the Vancouver Police Museum. Today they are with the BC Coroners Service, where Laura Yazedjian, identification specialist hopes to give them back their names.

4. A Prize Home under $1 Million

4. A Prize Home under $1 Million

The first PNE home was raffled off in 1934. It was worth $5,000 and is still at 2812 Dundas Street and valued at $1.6 million. This year’s house is worth $1.8 million and that’s only because it’s in Naramata, a five-hour commute from Vancouver. At 3025 square feet, it’s also more than twice the size of the 1934 edition and comes with a sauna, an elevator and interactive art.

5. Inspector Vance’s Crime Lab

5. Inspector Vance’s Crime Lab

I found this ad for the 1933 PNE in a pile of personal papers belonging to J.F.C.B. Vance, once known as the Sherlock Holmes of Canada. The slogan that Depression year was “Forward British Columbia—Prosperity Beckons.” Highlights included my Inspector Vance’s display of scientific apparatus for crime detection. It was insured for a whopping $10,000.

6. Dal Richards

6. Dal Richards

He was known as Vancouver’s King of Swing. Dal Richards, born in 1918, just 8 years after the first PNE, died on December 31, 2015. He was 97. Marpole-raised, Richards is a Magee Secondary grad from 1937. His 11-piece dance band played at the Hotel Vancouver for 25 years, and his radio show Dal’s Place aired for more than two decades. Richards played his 75th PNE—a 17-day-run in 2014.

Miss PNE contestants watching a football game at Empire Stadium in 1966. Courtesy CVA

Miss PNE contestants watching a football game at Empire Stadium in 1966. Courtesy CVA7. Empire Stadium and Miss PNE

Empire Stadium was constructed in 1954 for the British Empire and Commonwealth Games. It’s probably most famous for hosting Elvis Presley in 1957 and the Beatles in 1964 and was home to the BC Lions from 1954 to 1982. The stadium was demolished in 1993 two years after the last Miss PNE was crowned.

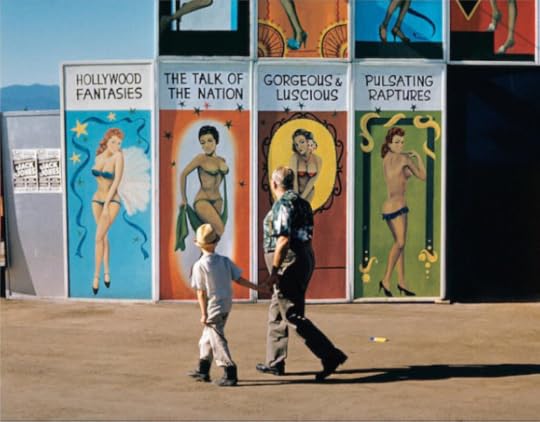

8. Pulsating Raptures

8. Pulsating Raptures

Love this Fred Herzog photo shot in 1962 at the PNE. Mum probably thought they were going to see the pig races. Note the Jack Jones posters, who according to Wikipedia, is 80 years old and still performing—but not at the PNE this year.

August 25, 1947. Courtesy CVA 180-1328

August 25, 1947. Courtesy CVA 180-13289. A Parade

On August 25, 1947 an estimated 100,000 people stood along Georgia, Granville and Hastings Streets waiting for the PNE parade—the first one in six years (because of the war). The first parade was in 1910 and the last—at least along this route—was in 1995.

Courtesy Heritage Vancouver Society

Courtesy Heritage Vancouver Society10. Roller Coaster

Dormer K Treffrey photographed the installation of the PNE’s first roller coaster in 1914. It had the wonderful name of Dip the Dips. It was replaced in 1925. Our wooden roller coaster has been around since 1958 and turns 60 this year (think of that next time you ride it).

Can you add to the list?

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

August 11, 2018

The BC Mills House Museum, a Mystery, a Captain and a Troll

The BC Mills House Museum at Lynn Headwaters plays a cameo role in Rachel Greenaway’s brilliant new mystery Creep where the action all takes place in upper Lynn Valley. While the little house has sat at the entrance to the park for a couple of decades now, I only recently discovered its back story.

Michael Kluckner’s painting of the BC Mills House at 147 East 1st Street in 1989.

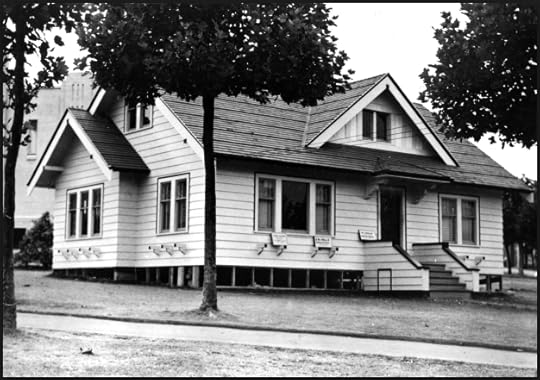

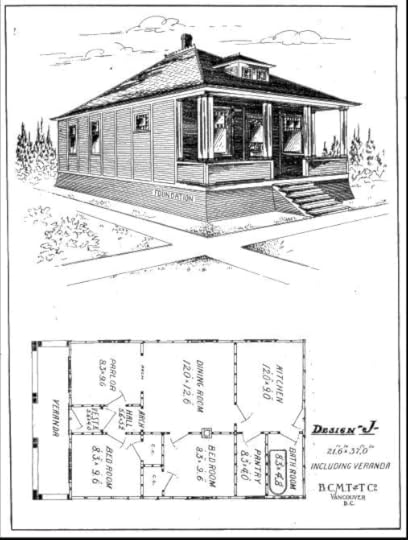

Michael Kluckner’s painting of the BC Mills House at 147 East 1st Street in 1989.According to Michael Kluckner’s Vanishing Vancouver, the two-bedroom house was built in 1908 at East 1st near Lonsdale in North Vancouver as an investment property. It was a pre-fab Model J constructed by the BC Mills, Timber and Trading Company which operated out of what’s now the Mission to Seafarers house at the foot of Dunlevy.

The owner, Captain Henry Pybus went broke along with a lot of other land speculators in the 1913/1914 land crash. A hunt through the city directories suggests the longest owner/resident was Mark Falonvitch, a Russian-born welder/foreman at Burrard Dry Docks who lived there with his wife Ada from the early ‘20s until his retirement in 1949.

Richard The Troll outside his house in Lower Lonsdale in 1988. CBC Archives

Richard The Troll outside his house in Lower Lonsdale in 1988. CBC ArchivesThe house’s most famous resident was Richard “The Troll” Schaller, former leader of the Rhinoceros Party of Canada which fielded candidates between 1963 and 1993 on the promise “to keep none of our promises”. Other platform promises included “repeal the law of gravity,” “provide higher education by building taller schools, and “ban guns and butter—both kill.”

Richard the Troll’s Rhino Party salute. CBC Archives

Richard the Troll’s Rhino Party salute. CBC ArchivesIn 1995, the house was saved thanks to the determination of long-time North Vancouver City Councillor Stella Jo Dean and moved to Lynn Headwaters. The Coronado, a four-storey condo building, is now in its former location.

See story on Fred Varley’s former house which is on the way to Lynn Headwaters

With thanks to Michael Kluckner for letting me pillage his painting and background from Vanishing Vancouver, to CBC Archives for their footage on Richard the Troll which you can watch here, Vancouver as it Was , and Macleans Magazine for the 14 campaign promises of the parti rhinoceros.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

August 4, 2018

The Art of Frits Jacobsen

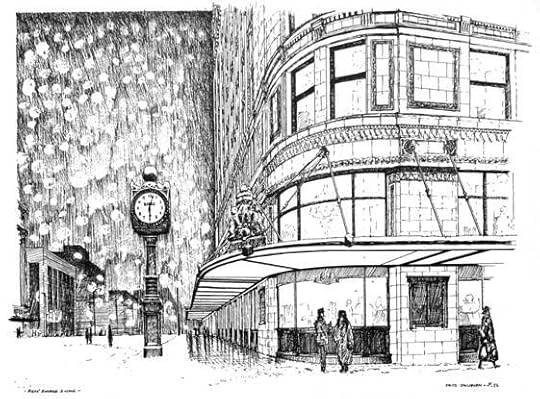

I first heard about Frits Jacobsen, and saw his beautiful drawings in a post by Jason Vanderhill on his Illustrated Vancouver blog. Jason kindly allowed me to repost it here.

Frits Jacobsen studied at the Free Academy of Fine Arts in the Hague before arriving in Canada in 1959. He moved to Vancouver in 1968. I met him in East Vancouver a few years before his death in 2015 and was able to show him a photograph of the door to his studio at 522 Shanghai Alley taken in 1974. His studio was next door, just above the Sam Kee Building. Both buildings are still there.

Courtesy Harold Henry (Hal) Johnston, 1974

Courtesy Harold Henry (Hal) Johnston, 1974The photo reminded Frits of his hostility towards the postal code movement, though when I showed it to him, he shrugged it off as rather comical.

In December 1979, Vancouver Magazine ran a feature titled “Now you see them” by Ian Bateson and featuring some of Vancouver’s threatened heritage buildings. The drawings that accompanied the article were not credited but I was able to confirm with Frits that he drew them.

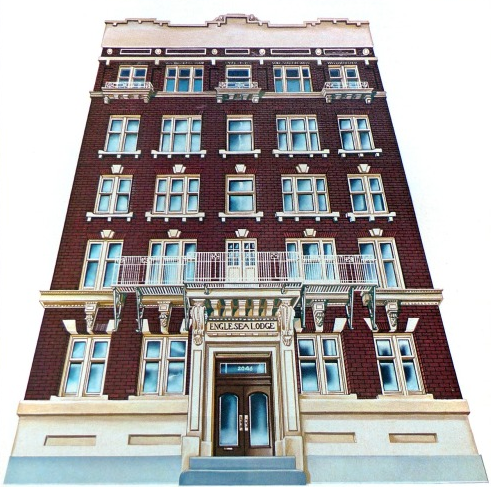

The Englesea Lodge, at the entrance to Stanley Park was the first to go, destroyed by fire in 1981.

In 1979, the Manhattan Apartments at 784 Thurlow Street was also under threat, but fortunately has managed to survive.

Built in 1908 for industrialist W.L. Tait, the Manhattan was one of the city’s first apartment blocks and served as a model for many that came after. The building contains attractive stained-glass windows designed by A.P. Bogardus and made in Vancouver. Three of the windows overlook the ornate, pilastered main entrance to the building, although the two smaller ones that sat above both the main and Robson Street entrances are missing. Hopefully, they have been stored somewhere and not destroyed by vandals.

The VanMag article included Jacobsen’s drawing of the Orillia on Robson and Seymour—demolished in 1985 to make way for a new tower.

Heritage Hall on Main Street rounds out the article. At the time, it had stood empty and neglected for two years and was in serious jeopardy. Thankfully, this was one battle that the heritage advocates won, and the hall survives to this day.

Frits was a remarkable artist and a true Vancouver character. If you happen to be going through the MCC thrift store in Surrey, you might just find his drawing of the missing Birks Building.

If you are lucky enough to own a Frits Jacobsen drawing, or one of his early photographs-likely shot in Strathcona or Kitsilano, please send me a picture or scan of it at info@evelazarus.com and we’ll either do another blog or put it up on Facebook Every Place has a Story. Eve.

July 28, 2018

The Royal Crown Soap Company

Occasionally, when I’m searching for photos using the baffling search engine at Vancouver Archives, I stumble across an interesting building or streetscape that I’ve never seen before. Often the information with the photos is quite detailed, but in the above photo all I had was a photo of the Royal Crown Soap Company building and the date ca.1905.

In front of 97 Water Street in 1936 . Courtesy CVA 99-4900

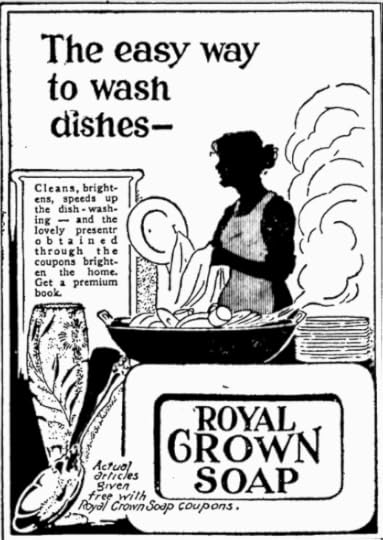

In front of 97 Water Street in 1936 . Courtesy CVA 99-4900As its name implies, the Royal Crown Soap Company was a Canadian company that specialized in soap with factories in Vancouver and Winnipeg.

The company first appears in the City Directories in 1900 at 308 Harris Street—what East Georgia was called prior to 1915—the year the first Georgia viaduct was completed. The company is managed by Frederick T. Schooley, and he stays at the helm for the next 28 years.

http://companiesofcanada.wikia.com/wi...

http://companiesofcanada.wikia.com/wi...Looking at ads from the ‘20s, Royal Crown was quite a prolific print advertiser, regularly engaging in coupon campaigns.

The company—which changes to the Royal Crown Soap Company and finally to Lever Bros Soap Manufacturers in 1942—started to see declining sales of soap in the 1940s. The city directory listing for 1949 is vacant, and the factory was demolished in the 1950s.

http://companiesofcanada.wikia.com/wi...

http://companiesofcanada.wikia.com/wi...A look at Google maps shows the building would have been where the park is at Gore and East Georgia. Today, the only thing left of the Royal Crown Soap Company, is a ghost sign on the side of the London Pub at East Georgia and Main.

Ghost sign at the London Pub. Photo courtesy Lani Russwurm, 2018

Ghost sign at the London Pub. Photo courtesy Lani Russwurm, 2018Top photo: The Royal Crown Soap Company, ca.1905. Photo courtesy CVA 312.27

With a ton of thanks to Lani Russwurm who discovered the ghost sign and put it on his blog PastTense Vancouver. And, then was kind enough to pop around and check if it was still there and snap this photo.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.