Eve Lazarus's Blog: Every Place has a Story, page 38

September 16, 2017

More of Vancouver’s Buried Houses

Last month, Michael Kluckner wrote a guest blog about the hidden houses of Vancouver. It was hugely popular and readers wrote in to let me know about more of these houses. Today’s blog is a compilation of those comments, photos and emails.

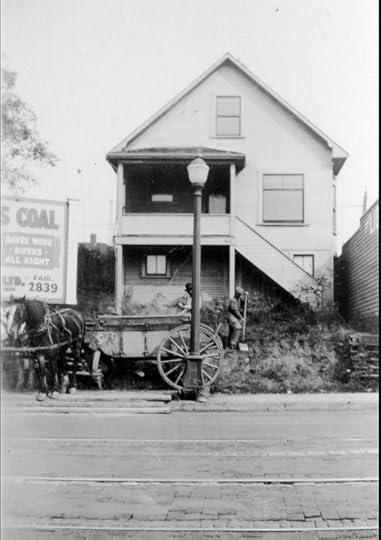

The buried houses on Denman near Beach Avenue are still highly visible. Here they are in 1928 with thanks to David Banks and Vancouver Archives.

The buried houses on Denman near Beach Avenue are still highly visible. Here they are in 1928 with thanks to David Banks and Vancouver Archives. Homeowners started building shops in front of their houses in the 1920s. Businesses ranged from bakeries and meat markets to cigarette and barber shops, shoe repairs and book stores. As Bill Lee points out, often with some bet taking on the side. “Having a small shop was a common second occupation in a family up to the 1960s when women had more opportunities for work,” he says.

1812 West Fourth Avenue via Google Maps. What goes around comes around.

1812 West Fourth Avenue via Google Maps. What goes around comes around.Gregory Melle says the store on Kitsilano’s 4th Avenue near Burrard was his late brother’s “head shop” in the early ’70s. Later it became an Indian restaurant. “I was amused to see last year that it had reverted to the same business for which it was infamous in my brother’s day,” he says.

2818 and 2820 Granville Street via Google maps

2818 and 2820 Granville Street via Google mapsMurray Maisie tells me that the house at Granville (near 12th) was originally owned by Maud Leslie. Maud and her daughter June added a book store called The Library in 1928 at #2820. City directories for that year show Beattie Realty at 2818, which later became the Antiseptic Barber Shop in 1935 (today it is the Black Goat cashmere shop). Daniel le Chocolat is the current tenant at 2820. Check out Murray’s story on his awesome blog Vancouver As it Was.

Vancouver Archives photo from 1928 of , 2818 and 2820 Granville.

Vancouver Archives photo from 1928 of , 2818 and 2820 Granville.Susan Anderson says her favourite buried house dates back to 1911 and hides behind BC Stamp Works at 583 Richards Street. “My great grandparents owned a house at 540 Howe Street and this building is the only remaining building like this north of Georgia Street,” says Susan. ‘The building has been covered up so completely I am not surprised people don’t know it’s there.”

583 Richards Street, courtesy Google Maps

583 Richards Street, courtesy Google MapsKim Richards says the stores on the east side of Mackenzie at 33rd including neighbourhood favourite Bigsby the Bakehouse, are a front for some hidden houses currently facing development pressure. Check out Mackenzie Heights Community page.

Buried houses at Mackenzie and 33rd courtesy Kim Richards, 2017

Buried houses at Mackenzie and 33rd courtesy Kim Richards, 2017 Ryan Dyer has his own hidden house at 820 East Pender, built in 1904 and moved to the back of the property in 1908.

Ryan Dyer has his own hidden house at 820 East Pender, built in 1904 and moved to the back of the property in 1908.

“There were originally three lots with three houses. Two of the houses were moved to the back of the properties and apartment buildings built at the front,” says Ryan. “The third house was amalgamated with the east apartment building, but can be seen if you look at the roof line of the building to the east of mine (828 east Pender).”

820 East Pender Street

820 East Pender StreetDavid Byrnes says he lived in a cottage/storefront at 2291 West 41st in Kerrisdale in the 1960s, and Penny Street notes that 1314 Commercial Drive–now Beckwoman’s Hippie Emporium appropriately fronts a hidden house—”Possibly a BC Mills pre-fab,” she says.

1314 Commercial Drive in 1978 Courtesy CVA 786-78.18

1314 Commercial Drive in 1978 Courtesy CVA 786-78.18Dan Enjo says there is still a house in the rear of Numbers at 1042 Davie, and the older floor space is part of the club. “There’s a noticeable bump between the newer and older buildings on the inside floor in places,” he says.

1141 Davie, courtesy Dan Enjo

1141 Davie, courtesy Dan EnjoThe house that is the Gurkha Himalayan Kitchen is quite visible, even though it’s now fronted by a market at 1141 Davie.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

September 9, 2017

Victory Square: what was there before?

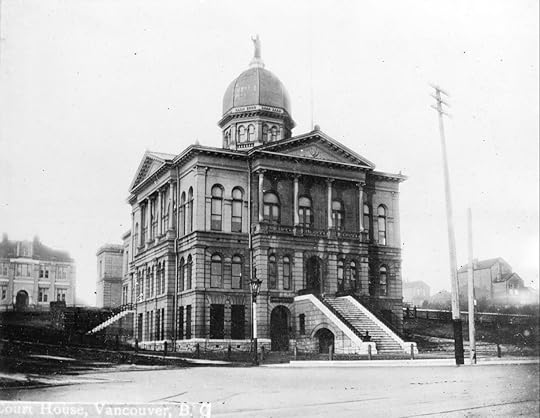

Before Victory Square was Victory Square and home to the Cenotaph, it was a happening part of the city known as Government Square, because it was the site of the first provincial courthouse.

The impressive domed building was operational by 1890 and was the first major building outside of Gastown. It was quickly apparent that it was too small for our growing city, and within a few years had a large addition with a grand staircase and portico facing Hastings Street.

Flack Building and the Courthouse ca.1900. Courtesy Vancouver Archives

Flack Building and the Courthouse ca.1900. Courtesy Vancouver ArchivesBuildings started to spring up around the Courthouse. In 1898, architect William Blackmore (Badminton Hotel, Lord Strathcona Elementary) designed a building for Thomas Flack who had made his fortune in the Klondike and wanted to see an impressive building bear his name.

The Arcade (corner building on the right), 1898. Courtesy Vancouver Archives

The Arcade (corner building on the right), 1898. Courtesy Vancouver ArchivesFour years earlier, Charles Wickenden, the same architect behind Christ Church Cathedral and the first Vancouver Club, designed the Arcade, a wooden building containing 13 shops, at the corner of Hastings and Cambie. It was gone by 1909, replaced by the fancy Dominion Building, at the time, the tallest building in the British Empire. It stayed that way until Mayor L.D. Taylor financed the Sun Tower as a monument to his newspaper (The World) in 1912.

Dominion and the Flack Building 1919. Courtesy Vancouver Archives 99.232

Dominion and the Flack Building 1919. Courtesy Vancouver Archives 99.232While Vancouver gained the Sun Tower and the new lawcourts on West Georgia (now the Vancouver Art Gallery), the city lost the original courthouse building–demolished after just 20 years.

The Square, which is actually more of a triangle than a square, is bounded by Hastings , Cambie, Pender and Hamilton. It didn’t remain empty for long. By 1914 it was filled with a military tent, used to recruit soldiers for World War 1. Then in 1917, up went the Evangelistic Tabernacle where the courthouse once stood.

The Evangelistic Tabernacle under construction in 1917. Courtesy Vancouver Archives

The Evangelistic Tabernacle under construction in 1917. Courtesy Vancouver ArchivesThe church was short lived as well. The Southams, owners of the Province Newspaper, which was housed across the street, donated funds to develop a park on land on the vacant land, which was then renamed Victory Square. By 1924, enough public money had been raised to build the Cenotaph designed by G.L. Sharp. Sharp had the 30-foot Cenotaph constructed from granite from Nelson Island.

The inscription facing Hastings Street reads: “Their name liveth for evermore. Facing Hamilton it says “Is it nothing to you.” And Facing Pender Street: “All ye that pass by.”

Victory Square 1925, courtesy Vancouver Archives

Victory Square 1925, courtesy Vancouver ArchivesTop photo: Courthouse on Hastings and Cambie, courtesy CVA Bu N13 ca.1893

References: Building the West; Public Art in Vancouver; The Vancouver Book; Vancouver Remembered.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

September 2, 2017

The PNE: Party Like it’s 1957

The last time I went to the Pacific National Exhibition was about a decade ago when my kids were still small. I’m guessing it hasn’t changed all that much. But I bet 60 years ago it was a whole different story.

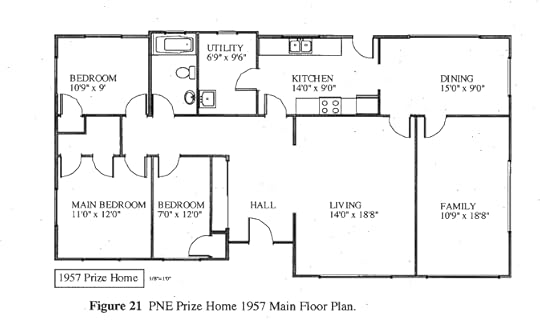

The PNE prize home in 1957. Courtesy Vancouver Archives 180-3947

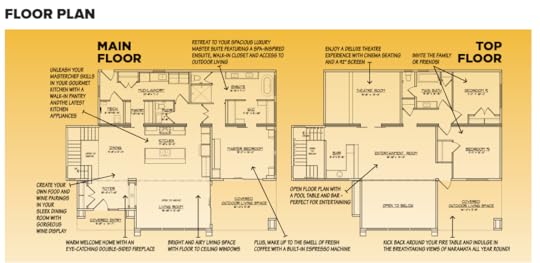

The PNE prize home in 1957. Courtesy Vancouver Archives 180-3947Take the prize home for instance. This year’s house is valued at $1.6 million. It’s 3,100 square feet, and comes with something called an “entertainment lounge,” a separate six-seat home theatre, as well as a built-in Expresso machine in the master bedroom. Seriously, you’ll never have to leave the house.

In 1957, things were a lot less complicated. People went out to movies and drank Nescafe in the kitchen. The prize home, at 1,444 square feet, was one and a half times the size of a normal house. It was a single-storey, boxy, early Ranch style house.

It was also less than half the size of the 2017 prize home.

The 1957 house was taken to, and remains at 6517 Lougheed Highway in Burnaby. It originally sat on a concrete pad, but owners have since added a basement, bringing the total square footage to a little over 2,400. It’s assessed at $1.2 million.

There were good and bad things about the PNE in 1957.

The PNE in 1957. Note the prize home on the left. Photo courtesy: https://www.flickr.com/photos/4537981...

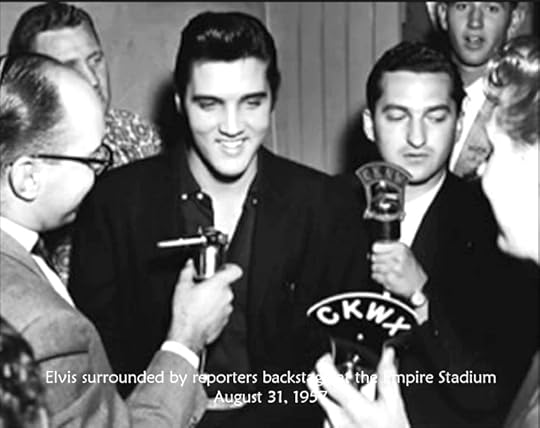

The PNE in 1957. Note the prize home on the left. Photo courtesy: https://www.flickr.com/photos/4537981...First the good. We had Elvis Presley. It’s true. He only ever performed three shows outside of the U.S.—Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver. In August 1957, more than 26,000 fans paid $3.75 each, to see him at Empire Stadium.

Livestock ruled.

Miss PNE 1957, Burnaby’s Carol Lucas presents first prize to poulty farmer

Miss PNE 1957, Burnaby’s Carol Lucas presents first prize to poulty farmerOn the downside, 1957 had beauty queens. In fact, there are 43 Miss PNEs. The last one hung up her crown in 1991.

Courtesy Vancouver Archives 180-3218

Courtesy Vancouver Archives 180-3218The first PNE home was raffled off in 1934. It was worth $5,000 and is still at 2812 Dundas Street. Today it’s valued at $1.6 million. The next house was raffled in 1952, and except for the years 1967 and 1968 when the PNE experimented with $50,000 gold bars, there has been a house raffled off every year. They exist in all areas of Metro Vancouver, and the 2017 prize home will finish up in the Okanagan’s Naramata.

With thanks to Helen Lee for her research, and to Elizabeth MacKenzie for access to her 2005 Master’s thesis, and the 1957 PNE prize home floor plan.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

August 26, 2017

The Buntzen Power Stations on Indian Arm

A couple of weeks ago, I took a boat ride up Indian Arm with Belcarra Mayor Ralph Drew and the Deep Cove Heritage Society. It’s hard to imagine that over a century ago Indian Arm was thriving and serviced by sternwheelers, a floating post office and grocery store.

A couple of weeks ago, I took a boat ride up Indian Arm with Belcarra Mayor Ralph Drew and the Deep Cove Heritage Society. It’s hard to imagine that over a century ago Indian Arm was thriving and serviced by sternwheelers, a floating post office and grocery store.

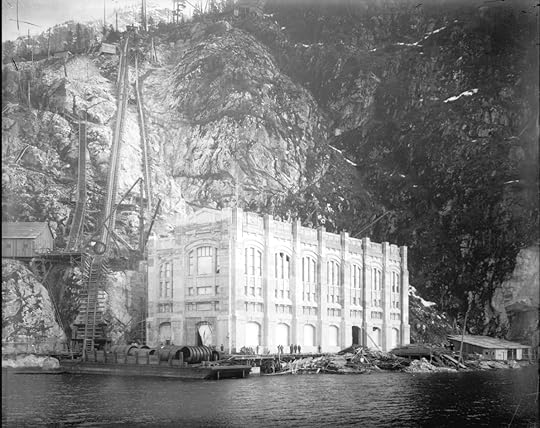

The highlight for me was finally seeing the Wigwam Inn, but almost as exciting were the two massive power stations that dominate the eastern shore at Buntzen Bay.

Power Station #2 was decommissioned in 1964. Eve Lazarus photo, July 2017

Power Station #2 was decommissioned in 1964. Eve Lazarus photo, July 2017Heather Virtue-Lapierre was born up there in 1943. Her grandfather Matt Virtue was one of the first power house operators shortly after #1 opened in 1903. Her father Jim carried on the family tradition from 1941 until the plant was automated in 1953.

1910: Far left Matt Virtue. H.R. Heinrich, master mechanic is in the cap. #5 Tom Lundy, #6 George Henshaw, and #8 Jim Findlay. Courtesy Heather Virtue-Lapierre

1910: Far left Matt Virtue. H.R. Heinrich, master mechanic is in the cap. #5 Tom Lundy, #6 George Henshaw, and #8 Jim Findlay. Courtesy Heather Virtue-Lapierre

Heather’s school was a one-room building above the power house. She was taught by a teacher who had worked as a welder during the war. “You didn’t mess with her!” she says. The teacher and her husband, who worked on the new penstock, lived in a small apartment attached to the school.

Heather at Power House #1 in 1953. Courtesy Heather Virtue-Lapierre

Heather at Power House #1 in 1953. Courtesy Heather Virtue-LapierreHeather says that power house operators were exempt from service during the war years, and instead joined the Pacific Coast Militia Rangers. “Nobody was allowed to land at Buntzen without permission during the war,” she says. “I still remember the blackout curtains in our house.”

1940s, the second generation. Left to right: Jim Virtue (son of Matt), Vic Shorting, George Mantle, Gill McLaughlin, Bill Henshaw (son of George) Courtesy Heather Virtue-Lapierre

1940s, the second generation. Left to right: Jim Virtue (son of Matt), Vic Shorting, George Mantle, Gill McLaughlin, Bill Henshaw (son of George) Courtesy Heather Virtue-LapierreDawson Truax’s father was a floor man, and Dawson was just 18 months old when he moved to Buntzen with his war-bride mother in 1946. They lived in a cabin on the hill above the power plant owned by the BC Electric Railway (the forerunner to BC Hydro). Supplies came weekly on the MV Scenic.

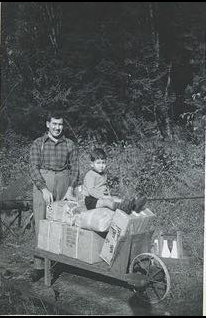

Dawson with his dad, 1948. He used a wheelbarrow to get parcels from the hoist to their cabin. Photo courtesy Dawson Truax

Dawson with his dad, 1948. He used a wheelbarrow to get parcels from the hoist to their cabin. Photo courtesy Dawson Truax“It was quite a small community and only took three men to run the power plant at any time over three shifts a day,” he says. “There was a hoist on tracks that went up the hill from the plant area to the cabin. One of my first childhood memories is of my father putting me on the hoist with a pile of parcels while he walked alongside.”

“My mother talked about it quite a bit. It was quite horrifying for her to move from London, England to the Canadian wilderness,” he says.

Buntzen gets its name from Johannes Buntzen, BCER’s first general manager. According to Ferries & Fjord, the power stations weren’t the first industry on the Arm. The area was populated as early as 1880 by a Japanese Logging Camp. Between 1902 and 1914 around 500 men camped up there while they worked on a tunnel from Coquitlam Lake to Buntzen Lake.

Vancouver’s rapid growth soon demanded more power, and Power Station #2 opened in 1914.

Rumour has it, #2 was designed by Francis Rattenbury, the architect who designed the Parliament buildings and the Empress Hotel in Victoria, and the Courthouse on West Georgia. It certainly looks like his work—large, gothic and creepy (Rattenbury, who was a bit of a jerk, was eventually murdered by his trophy wife’s 18-year-old lover). But according to Building the West, #2 was designed by Robert Lyon, an architect employed by BCER.

Power Station #1. Eve Lazarus photo, July 2017

Power Station #1. Eve Lazarus photo, July 2017Top photo of Power Station #2 courtesy Vancouver Archives LGN 1169 ca.1914

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

August 19, 2017

Saving History: Twinning the Lions Gate Bridge

Lions Gate Bridge in 1940. Courtesy CVA 586-462

Lions Gate Bridge in 1940. Courtesy CVA 586-462The Lions Gate Bridge spans the first narrows in Burrard Inlet, connects Vancouver to the North Shore, and is one of the most iconic structures in the city. Built by the Guinness family to encourage development after they bought the side of a West Vancouver mountain, the suspension bridge was tolled from the time it opened in 1938 until 1963.

It cost 25 cents for cars and five cents for pedestrians.

Vancouver Sun photo

Vancouver Sun photoBy the early 1990s, the bridge was in serious need of an upgrade or replacement and the City narrowed down the options to three proposals. One was to build a tunnel; another to twin the bridge and double the number of lanes; and the third was to double-deck the existing three-lane bridge.

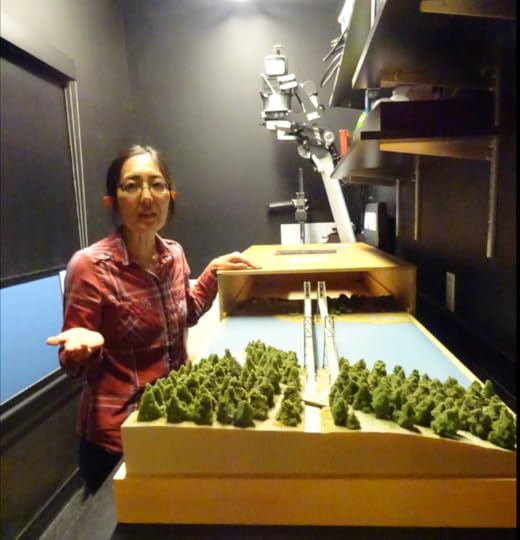

Last year, Daien Ide, reference historian at the North Vancouver Museum and Archives was sitting at her desk when she got a tip. A model of the proposed twinned bridge had turned up at the Burnaby Hospice Thrift Store on Kingsway with a $200 price tag.

A local had saved the model after finding it tossed out in an alley behind his house a couple of decades earlier. For whatever reason, he decided it needed rehoming, and gave it to the thrift shop.

The scaled model is clearly identified with the name of the architectural firm—Safdie Architects. In Canada, Moshe Safdie is a highly regarded architect, known for the Expo 67 Habitat in Montreal, the National Gallery in Ottawa, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, and our very own Vancouver Public Library.

In 1994, Safdie partnered with engineering firm SNC Lavalin, and the Squamish Nation, which owned the land on the north end of the bridge.

They wanted to build an identical bridge to the east of the original structure that would carry northbound traffic, while the original bridge would carry vehicles south into Stanley Park. The new bridge would be tolled, and judging by the model, cut a chunk out of Stanley Park.

As we now know, the Province chose the cheapest and least controversial option, electing to widen the three-lane existing bridge and replace the main bridge deck.

In 2005, the Lions Gate Bridge was designated a National Historic Site of Canada.

Our traffic problems persist.

Huge thanks to the NVMA’s Nancy Kirkpatrick for giving me the idea for the blog and for supplying research materials.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

August 12, 2017

The amazing photography of Stephen Joseph Thompson (1864-1929)

Cordova Street looking west in 1898 with the Dunn-Miller building. Courtesy CVA

Cordova Street looking west in 1898 with the Dunn-Miller building. Courtesy CVAI’m obsessed with a photographer named Stewart Joseph Thompson. I became aware of him a few weeks back when Pamela Post sent me a photo he’d taken of Georgia and Burrard Streets in the 1890s. Then, last week I found a photo he took the day after the fire destroyed New Westminster in 1898, including Thompson’s own Columbia Street studio.

Columbia Street, New Westminster after the fire 1898. Courtesy CVA

Columbia Street, New Westminster after the fire 1898. Courtesy CVAAccording to Jim Wolf’s A photographic history of New Westminster, the Ontario-born Thompson was a talented artist who trained in Toronto, Montreal and New York. He was 21 when he moved to New Westminster in 1886 and partnered up with the Bovill brothers. Many of his early photos were commissioned portraits, but he was also shooting and selling landscapes—mostly along the CPR line.

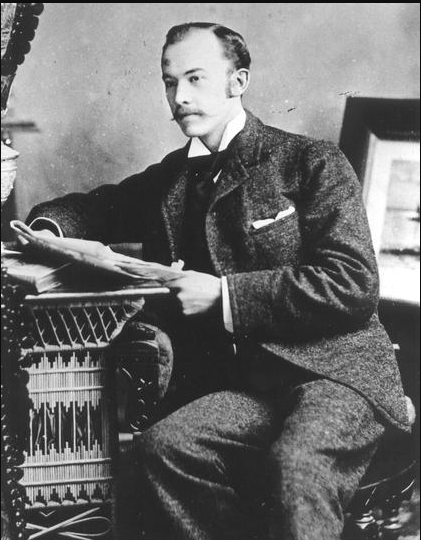

Stephen Joseph Thompson, courtesy NWPL 2927

Stephen Joseph Thompson, courtesy NWPL 2927By 1888 he had his own studio in the Hamley Block on Columbia Street, selling “beautiful views of B.C. mountain scenery and city views for souvenirs.”

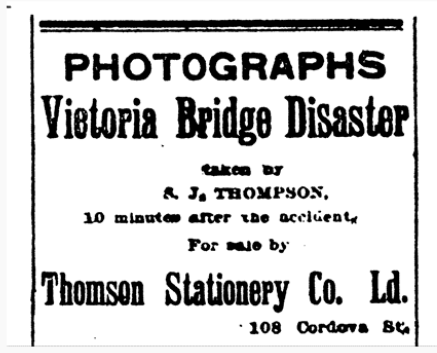

Point Ellice bridge disaster May 26, 1896

Point Ellice bridge disaster May 26, 1896Thompson was in Victoria on May 26, 1896 when a streetcar overflowing with 143 people off to the Queen Victoria birthday festivities, plunged through the Point Ellis bridge killing 55 and injuring many more. Evidently, he saw the disaster as a business opportunity, and took out an ad in the Vancouver News-Advertiser.

Thompson married Constance Victoria Clute In 1897. They moved to Vancouver, opened a studio at 610 West Hastings, and put an assistant in charge of the New West business. The following year, his New West studio and thousands of glass plate negatives were destroyed in the Great Fire.

Vancouver from Mount Pleasant 1898. Courtesy CVA

Vancouver from Mount Pleasant 1898. Courtesy CVAThe city directories show the Thompsons living at various addresses in the upscale West End. He was listed as a photographer and art supplier until around 1911. After that, Thompson joined the ranks of property speculators and set himself up as a realtor, eventually moving into the Standard Building at 510 West Hastings.

From the 1909 Vancouver City Directory

From the 1909 Vancouver City DirectoryIn 1927, the tanking economy likely drove him back to photography. That year the city directory lists Thompson as the manager of Photo-Arts on Dunsmuir, and his home address the Washington Court at Thurlow and Nelson.

He died in 1929.

Granville Street looking north east from the first Hotel Vancouver at Georgia in 1905. Shows Hudson Bay, Bank of Montreal and the spire of Holy Rosary Cathedral. CVA

Granville Street looking north east from the first Hotel Vancouver at Georgia in 1905. Shows Hudson Bay, Bank of Montreal and the spire of Holy Rosary Cathedral. CVA© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

August 5, 2017

Vancouver’s Buried Houses

A few weeks ago, Michael Kluckner ran a painting of a Kitsilano house on his FB page. I googled the address and was astonished to find that the house was still there on busy 4th Avenue, buried behind an ice-cream parlour. Michael tells me that only a handful of these buried houses remain, and he kindly wrote this story illustrated by his paintings from 2010 and 2011 that appeared in Vanishing Vancouver: The Last 25 Years.

By Michael Kluckner

In the interwar years, Vancouver’s commercial streets filled in with single-storey shops, many of them simple boxes with no decorative trim. They were the utilitarian independent stores of the “streetcar suburbs” like Grandview’s Commercial Drive and the West End’s Robson Street. A typical Vancouver commercial street, right up until the 1970s, was a mix of shops, a few apartment buildings, and houses.

Especially during the Great Depression of the 1930s, owners of these houses tried to make their properties viable by adding commercial storefronts in what had been the houses’ shallow front yards.

Just east of Arbutus, 2052 West 4th Avenue (above) is a 1905 house with a 1927 addition on the front. Over the years it has housed a dry cleaner, a build-it-yourself radio shop, and a poster store catering to the hippies in nearby rooming houses. It was nicknamed The Rampant Lion, after the tenants’ rock band.

Visible only from Fraser Street and the back lane, the 1897 house at 708 East Broadway is hidden behind a storefront built by W.M. McKenzie. Later, an electrician named John Grumey, converted it into “Launderama.” It has been further subdivided with a tailor occupying half of the storefront.

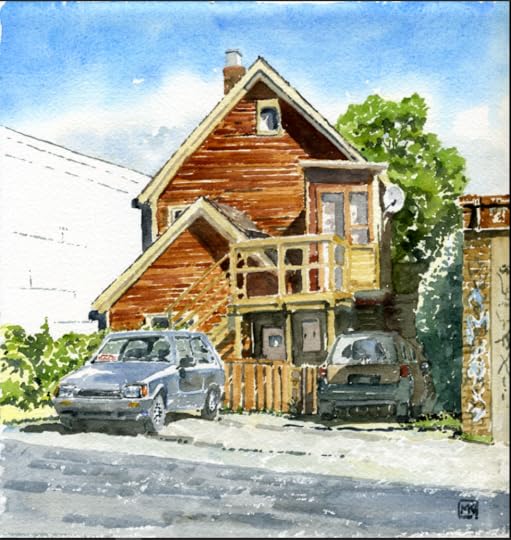

708 East Broadway, where W.M. McKenzie operated a grocery store from 1932 to the 1950s. Michael Kluckner, 2010

708 East Broadway, where W.M. McKenzie operated a grocery store from 1932 to the 1950s. Michael Kluckner, 2010The best set of buried houses in the city are on Renfrew just south of 1st Avenue. The houses were built in 1937, 1921 and 1926 respectively, indicating the slow settlement of Vancouver east of the old city boundary at Nanaimo Street. A small retail hub developed there due to the Burnaby Lake interurban line stop which ended service in 1952.

Renfrew houses at East 1st. Michael Kluckner, 2010

Renfrew houses at East 1st. Michael Kluckner, 2010There are other buried houses on West Broadway near Balaclava, on 4th Avenue just west of Burrard, and Granville around 13th.

Buried house at West 4th Avenue near Burrard, 2017

Buried house at West 4th Avenue near Burrard, 2017A buried house, probably built in 1907 with a horrid concrete-block shop/factory front attached to it is still at 350 East 10th Avenue, directly behind the Kingsgate Mall and next to a Telus parking lot.

350 East 10th Avenue. Michael Kluckner, 2010

350 East 10th Avenue. Michael Kluckner, 2010Until a few years ago, a 1904 house was built at the back of its lot to allow for shops in front on the northeast corner of Broadway and St. Catherines. The shops were demolished a generation ago, the house a few years back. Townhouses now occupy the site.

Broadway and St. Catherines. Michael Kluckner, 2010

Broadway and St. Catherines. Michael Kluckner, 2010The most visible buried houses are the set on Denman Street just up from the beach.

A row of buried houses on Denman near Davie, 2017

A row of buried houses on Denman near Davie, 2017Houses, just like other buildings, adapt or die. There is not a lot of old Vancouver, at least on the commercial streets, that can adapt to the new reality of land prices, taxes, the desire to densify, and the changing retail landscape.

Michael Kluckner is a writer and artist with a list of books that includes Vanishing Vancouver and Toshiko. His most recent book is a graphic novel called 2050: A Post-Apocalyptic Murder Mystery. He is the president of the Vancouver Historical Society and a member of the city’s Heritage Commission.

July 29, 2017

The Navvy Jack House: Past, Present and Future

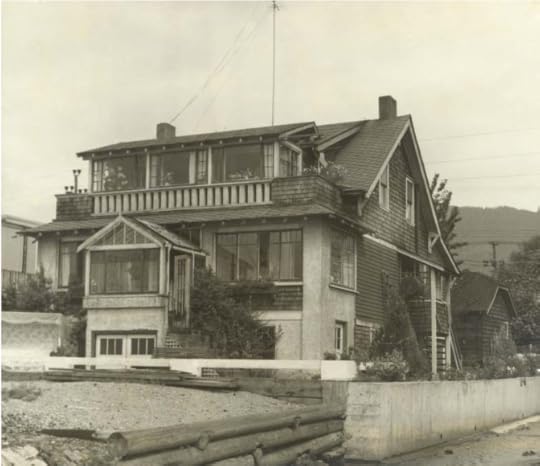

Navvy Jack House, 1957. Photo courtesy West Vancouver Archives

Navvy Jack House, 1957. Photo courtesy West Vancouver ArchivesJane Williams kindly gave me a tour of her parent’s house at 1768 Argyle Avenue last week. Her father, Lloyd Williams died in April at the age of 96, and she was getting ready to hand the keys over to the District of West Vancouver. Lloyd and Jane’s mother Bette paid $50,000 for the house in 1971, before the seawall was installed and when the next-door John Lawson Park was still a field with a few scattered houses.

Lloyd and Bette Williams, 1990s. Photo courtesy Jane Williams

Lloyd and Bette Williams, 1990s. Photo courtesy Jane WilliamsThe District has owned the “Navvy Jack” house since 1990 when the Williams’ made a deal in exchange for life tenancy. It’s the last one following a council decision in 1975 to buy up the 32 houses along the Ambleside waterfront between 13th and 18th either through land sales or expropriation. With the exception of the Silk Purse, the Ferry Building, and the Navvy Jack house, the others have been bulldozed back to nature.

The Hollyburn General Store, post office and Navvy Jack’s house at 17th and Marine Drive in 1914. Photo courtesy Vancouver Archives

The Hollyburn General Store, post office and Navvy Jack’s house at 17th and Marine Drive in 1914. Photo courtesy Vancouver ArchivesDepending on the source, the Navvy Jack house was built between 1868 and 1873. It was shifted from its original location at 17th in 1921 to allow for the opening of Argyle Avenue. While it’s not the oldest house in Metro Vancouver, it’s pretty darn close.

Originally from Wales, Navvy Jack (John Thomas) came to Canada to seek his fortune in the gold fields. Instead, he operated an unscheduled ferry service in 1866. The following year he bought 32 hectares of waterfront land from 16th to 22nd Street and founded a gravel hauling business on the Capilano River (a sand and gravel mix is named for him).

Navvy Jack’s house on the wedding day of John Lawson’s daughter in 1914. The house was white with a veranda that ran the entire width held up by Victorian brackets on turned columns. The exterior is moulded cedar siding. Courtesy West Vancouver Archives

Navvy Jack’s house on the wedding day of John Lawson’s daughter in 1914. The house was white with a veranda that ran the entire width held up by Victorian brackets on turned columns. The exterior is moulded cedar siding. Courtesy West Vancouver ArchivesNavvy Jack married Rowia, granddaughter of Chief Kiepilano and raised four children in the house. By the 1890s he was broke and lost the house in a tax sale.

John Lawson, who was known as the “Father of West Vancouver,” and namesake of the John Lawson Park, bought the house in the early 1900s. It changed hands a few more times until the Williams’ moved in.

Jane standing in the kitchen. Bette made a kitchen hutch and a fireplace from the hatchboards from schooners that washed up on the beach. Eve Lazarus photo, 2017

Jane standing in the kitchen. Bette made a kitchen hutch and a fireplace from the hatchboards from schooners that washed up on the beach. Eve Lazarus photo, 2017Lloyd was born in Kitsilano in 1921. He met Bette at Kitsilano High School, and later became a salesman for Simonds saws. Jane says her father’s passion was the garden that faced the ocean and overflowed with sweet peas, roses and vegetables.

According to the Statement of Significance, Lloyd’s uncle Alfred lived in West Vancouver in 1891. He was rescued from drowning at the mouth of the Capilano by Navvy Jack’s son.

How fitting that a couple of Vancouver pioneers would buy a house filled with so much history and then become its caretakers for over half a century.

Eve Lazarus photo, 2017

Eve Lazarus photo, 2017The house is in rough shape. Over the last 140+ years it has been renovated, changed, and neglected. While it’s on the heritage inventory, it is not on the very small list of designated properties, which means that it has no protection. Hopefully that will soon change.

The District’s Jeff McDonald tells me that while nothing is confirmed, the plan is to turn the house over to the West Vancouver Streamkeepers Society to be run it as a nature house.

Navvy Jack house in 1988. Courtesy West Vancouver Archives

Navvy Jack house in 1988. Courtesy West Vancouver Archives© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

July 22, 2017

West Vancouver’s Ambleside: Then and Now

If you live on the North Shore, chances are that you spend at least some of your summer at Ambleside. Did you know that you are sitting on reclaimed land? Prior to 1965, much of this land was a swamp.

Ambleside Beach in 1918. Photo 0002.WVA.PHO

Ambleside Beach in 1918. Photo 0002.WVA.PHOIn 1914, Ambleside was subdivided into 17 lots and filled with makeshift homes and a few businesses. Because much of the area was often under water, many of the structures, including Overington’s barber shop, were raised on stilts, and most comprised little more than a floor, some wooden sides and a canvas top.

Ambleside East of 13th, taken from Sentinel Hill in 1910. 423.WVA.THO

Ambleside East of 13th, taken from Sentinel Hill in 1910. 423.WVA.THOIn those days, a large slough cut through Ambleside and ran between Capilano River and 14th Street, and boats moored on the north side of Marine Drive. In the winter, residents skated on the frozen slough, in the summer they fished for cod, and shot pigeons and ducks on the surrounding marsh.

Ambleside was designated as a park in 1918.

The Ambleside slough, mouth of the Capilano River and the Capilano Fog and Light Station in 1921. 0461. WVA.RAH

The Ambleside slough, mouth of the Capilano River and the Capilano Fog and Light Station in 1921. 0461. WVA.RAHJust across from the sports field at Ambleside Park is a building that houses the Ambleside Youth Centre. Before that it was home to the West Vancouver Rod and Gun Club, and before that it was one of 18 huts built by the Department of National Defence with four-gun emplacements and anti-aircraft guns to defend the harbour entrance below the Lions Gate Bridge during World War 11.

Ambleside Beach, 1932. 3411.WVA.PHO

Ambleside Beach, 1932. 3411.WVA.PHOAfter the war, the huts were converted into housing for war vets and their families. Officially, the housing development was named the Ambleside Park Village; unofficially locals called it “Diaper Lane.” The huts were built on low land that flooded several times a year, and at those times, food and supplies were brought in by rowboat.

Ambleside War Assets Corporation Huts in the 1940s. Photo courtesy West Vancouver Archives

Ambleside War Assets Corporation Huts in the 1940s. Photo courtesy West Vancouver ArchivesThe playing fields and pitch-and-putt are built on sawdust, bark and wood waste from a North Vancouver sawmill. The duck lagoon was created by dredging part of the slough, while Ambleside beach is a product of 85,000 cubic metres of sand and gravel hauled from the sandbanks west of Navvy Jack Point.

Ambleside Beach 2017. Photo courtesy Eyoalha Baker

Ambleside Beach 2017. Photo courtesy Eyoalha Baker© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

July 15, 2017

Saving History: The Lost Scrapbooks from the Marco Polo

By Tom Carter

Tom Carter is an artist, a musician, a historian, and a private collector. He has kindly agreed to write a guest blog about one of his most exciting finds.

There are some “holy grails” out there in Vancouver entertainment history—stuff we fantasize about that still exists somewhere. I still can’t believe I landed one of the biggest of them—the owner’s scrapbooks from the Marco Polo!

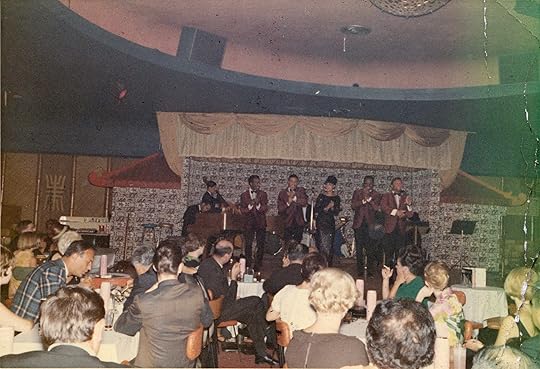

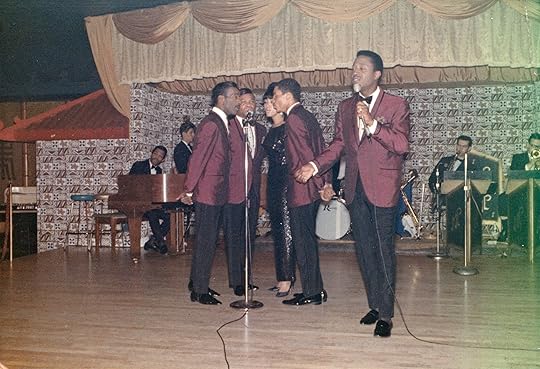

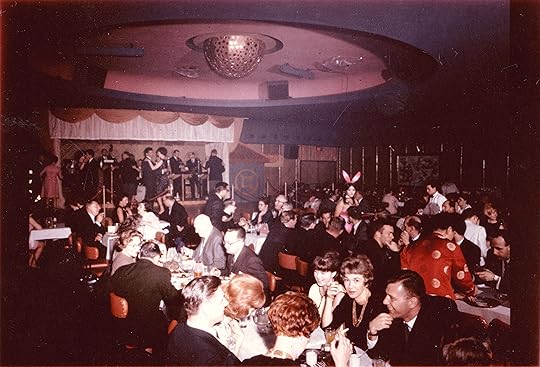

The Marco Polo, a club deep within Chinatown, was one of Vancouver’s legendary nightclubs. In the ‘60s it was considered one of the “big three” along with The Cave on Hornby and Isy’s Supper Club on Georgia. While posters, cards and ephemera are pretty common from The Cave and Isy’s, the Marco Polo has long been shrouded in mystery.

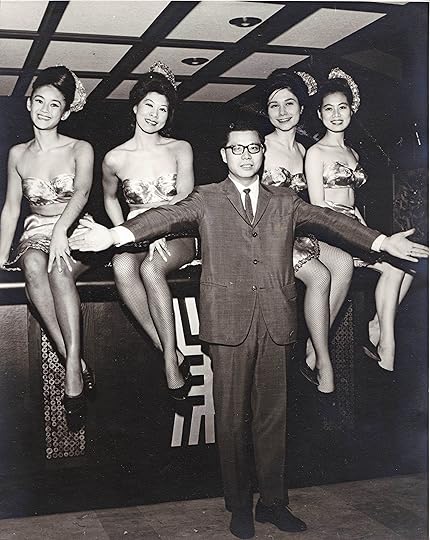

Over the years there have been rumours of scrapbooks kept by Victor Louie, manager and one of the Louie brothers who owned the club. They had become a legend among collectors like Jason Vanderhill and Jim Wong-Chu who have been hunting them for years.

What we knew was that Victor Louie had loaned the scrapbooks to Jason Karman when he was researching a film about Harvey Lowe in the early 1990s. Lowe was a yo-yo champion, owner of the Smilin’ Buddha and a staple of the Chinatown entertainment scene with connections to the Marco Polo.

After Karman returned the scrapbooks they vanished!

Then, last year, they miraculously resurfaced when a dealer I know bought the scrapbooks from a picker who had pulled them out of the garbage behind a warehouse in Chinatown. (A “picker” is someone who combs through junk in alleys, dumpsters, etc. looking for things of value to sell to antique dealers).

The dealer told me he planned to dismantle the books and sell off the bits—effectively destroying their historical value.

Instead, I bought everything.

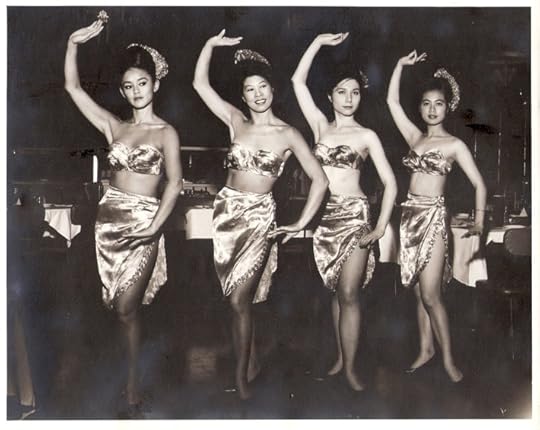

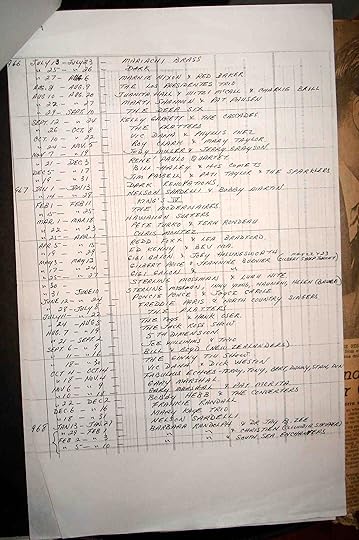

When I got the scrapbooks home, I discovered photos of musicians on stage and chorus girls. There were menus and handbills and all sorts of letters from clients. Harvey Lowe had produced and emceed the opening show, and I found his script. There was even a handwritten listing of every act that played the club from 1964 to 1968!

These scrapbooks form a more-or-less complete history of the Marco Polo from 1960 when the Louie’s took over the Forbidden City and renamed it, through to 1982 when the original Chinatown club closed and moved to North Vancouver.

Everything is now photographed, and with the assistance of BC PAMA and the UBC School of Library Archival and Information Studies, the entire contents of the scrapbooks will eventually be online.

Tom Carter has been painting historical views of Vancouver for many years with artwork in prominent private and corporate collections. Tom serves on the boards of the BC Entertainment Hall of Fame, Friends of the Vancouver Archives and the Vancouver Historical Society. You can read more about his work in Vancouver Confidential “Nightclub Czars of Vancouver and the Death of Vaudeville.”