Eve Lazarus's Blog: Every Place has a Story, page 40

May 6, 2017

They Paved Paradise and put up a Parking Lot

Bus Depot , 150 Dunsmuir Street in 1953. Photo Courtesy Vancouver Archives LP 205.4

Bus Depot , 150 Dunsmuir Street in 1953. Photo Courtesy Vancouver Archives LP 205.4My friend Angus McIntyre was a Vancouver bus driver for 40 years and often took photos of heritage buildings, neon signs, street lamps and everyday life on his various routes. His photos are always so vivid and interesting (see his posts on Birks and elevator operators) and when he sends me one, I stop whatever I’m doing and nag him for the back story.

Inside the bus depot in 1979. Angus McIntyre photo.

Inside the bus depot in 1979. Angus McIntyre photo.Angus shot this photo of the old bus depot on Dunsmuir Street (Larwill Park) in 1979. He tells me: “This was just after Pacific Stage Lines had been dissolved, and Pacific Coach Lines had started the replacement service. The signs have tape covering the word ‘Stage’.” Angus says that on an earlier busy Sunday, employees conducted a mock funeral for Pacific Stage Lines. “Afterwards, there was a wake at the bus drivers’ booze can across the street on Dunsmuir. Seems Vancouver has this thing for mock funerals,” he says.

Larwill Park today via Google Maps

Larwill Park today via Google MapsSeems we also have a thing for parking lots. Vancouver seems to revere parking lots as much as other cities value heritage buildings, public space, and art. (See Our Missing Second Hotel Vancouver).

Larwill Park is now the huge downtown parking lot that is bounded by Cambie, Dunsmuir, Beatty and Georgia Streets. It began life as the Cambie Street Grounds, a park and sports fields. And, being opposite the Beatty Street Drill Halls, at times operated as a military drill ground. The park was named after Al Larwill, who the story goes, was made “caretaker” after squatting in a shack on the land for many years. He was given a house on a corner of the land where he stored sports equipment and allowed team members to use his dining room to change.

Military exercises Cambie Street Grounds ca.1907. Photo Vancouver Archives 677-980

Military exercises Cambie Street Grounds ca.1907. Photo Vancouver Archives 677-980In 1946, Charles Bentall of the Dominion Construction Company built the bus depot, and it opened the following year as the most modern in Canada. Pacific Stage Lines, Greyhound, Squamish Coach Lines and others operated out of the terminal, until car culture struck in the 1950s and ‘60s and some of the companies went under.

In 1979, when Angus took his photo, Pacific Stage Lines had just merged with Vancouver Island Coach lines to become Pacific Coach Lines. In 1993, the bus depot moved to Pacific Central Station and the land became a parking lot.

How the Vancouver Art Gallery sees the future of Larwill Park.

How the Vancouver Art Gallery sees the future of Larwill Park.The Vancouver Art Gallery has its sights on the land and wants to turn it into a backdrop for its for its bizarre bento-box building.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

April 29, 2017

Bring Back the Streetcar!

Shocked faces of people riding the streetcar as they get their first look at the new Vancouver Brill (trolley) bus in 1949. Photo courtesy Angus McIntyre.

Shocked faces of people riding the streetcar as they get their first look at the new Vancouver Brill (trolley) bus in 1949. Photo courtesy Angus McIntyre.On September 3, 1906 the first North Vancouver streetcar began its journey at the ferry dock, travelled up Lonsdale and stopped at 12th Street. Jack Kelly was the conductor aboard that inaugural run. Everything went smoothly on the way up, but on the way back down, the brakes failed and Car 25 came crashing into another streetcar waiting at the bottom. Three years later, Kelly was at the controls of Car 62 when it headed down Lonsdale to meet the 4:00 p.m. ferry. Once again, the brakes failed. With 15 passengers screaming in fright, including the wife of the North Vancouver mayor, the car careened down the hill and off the end of the dock. Kelly leaped from the car, breaking his leg. The rest of the passengers were fished out of the harbour.

Streetcar #120 going south on Quebec Street into the car barn on Main Street. Photo courtesy Friends of the Olympic Line .

Streetcar #120 going south on Quebec Street into the car barn on Main Street. Photo courtesy Friends of the Olympic Line .Dangers of early street cars aside, I’d love to see some return. At its height, there was a streetcar system that operated in Vancouver, New Westminster and North Vancouver where three lines operated up Lonsdale, Capilano and Grand Boulevard, later extending to Lynn Valley.

Streetcar #153 heads northbound on Lonsdale Avenue in 1946. Photo courtesy North Vancouver Museum & Archives

Streetcar #153 heads northbound on Lonsdale Avenue in 1946. Photo courtesy North Vancouver Museum & ArchivesCar 153 was built by the J.G. Brill Company of Philadelphia and motored up and down Lonsdale Avenue for 35 years. Designed as a “double-ender,” when she reached the Windsor Road terminus at the top of Lonsdale the motorman and the conductor switched places for the return trip.

When streetcars were discontinued in 1947, most of their parts were sold off for scrap, while a few became summer cottages or farm buildings. Car 153 survived first as a motel cabin near Mission, then as a restaurant in Chilliwack, and, before she was rediscovered in 1982, a chicken coop on a Fraser Valley farm. Car 153, which was restored by the North Vancouver Museum & Archives in the early 1990s, and is I believe, still in storage at Mahon Park, where it’s likely to stay.

The interurban running southbound on Commercial at East 2nd in 1950. Photo courtesy Friends of the Olympic Line

The interurban running southbound on Commercial at East 2nd in 1950. Photo courtesy Friends of the Olympic LineLast June, councillor Don Bell’s appeal to bring back the streetcar got promptly flattened. One councillor called it: “pursuing a classic boondoggle,” telling the North Shore News: “Put yourself in Translink’s shoes: if they give this to us, how many municipalities in Metro Vancouver are going to be right at the door asking for exactly the same thing?”

Yes, god forbid Vancouver should have a transit system that makes sense. We called them trams in Melbourne where I grew up, and we took them everywhere. Now they are free in the city centre, and as well as being an amazing tourist attraction, they just make good sense from a transportation and clean energy point of view.

Photo courtesy Vancouver Archives

Photo courtesy Vancouver ArchivesA group called Friends of the Olympic Line Vancouver Civic Railway is lobbying to bring back streetcars to Vancouver. Check out their Facebook page and their website,

Photo courtesy Vancouver Archives

Photo courtesy Vancouver ArchivesFor more about the streetcars and Interurbans of Vancouver:

http://evelazarus.com/may-1-1907-a-trip-across-vancouver/

http://evelazarus.com/the-train-that-ran-down-hastings-street/

April 22, 2017

The Life and Death of Seaton Street

1145 Seaton Street, ca.1890. Owned by Stephen Richards, a lawyer and land agent. Photo Vancouver Archives SGN 297

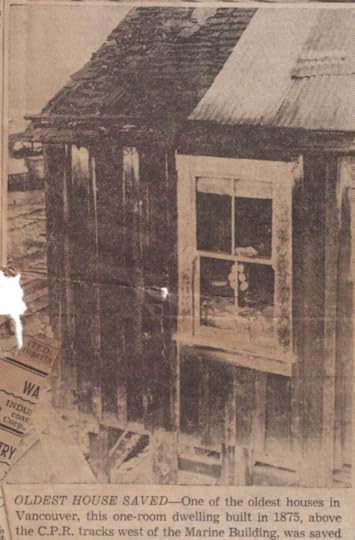

1145 Seaton Street, ca.1890. Owned by Stephen Richards, a lawyer and land agent. Photo Vancouver Archives SGN 297Last week I wrote about the oldest house in Vancouver—well at least that’s what they called it when it burned to the ground in 1946. It was built in 1875, and until 1915, its address was Seaton Street.

1120 Seaton Street in 1895. Owned by John P. Nicolls, a solicitor. CVA Bu P561

1120 Seaton Street in 1895. Owned by John P. Nicolls, a solicitor. CVA Bu P561Unlike most of Vancouver’s streets that are named after old white men, Lauchlan Hamilton, the CPR surveyor, named this one in 1886 after pulling it at random from a map (the town of Seaton is long gone, but used to be near Hazelton in northern BC).

1218 Seaton Street ca.1901. Residents are William Bauer, surveyor and Major-General Twigge. CVA SGN 849.

1218 Seaton Street ca.1901. Residents are William Bauer, surveyor and Major-General Twigge. CVA SGN 849.The street was dubbed Blueblood Alley after its wealthy occupants. It was also a short walk to the original Vancouver Club at Hastings and Hornby Streets (built in 1893), and from 1912, the Metropolitan Club on the next block down.

1117 Seaton Street, 1914. Canadian Army Service Corps building. CVA

1117 Seaton Street, 1914. Canadian Army Service Corps building. CVAIn 1901, the city directory shows 15 houses on Seaton Street from Burrard to Jervis. Residents include Mayor Thomas Townley, Henry Ogle Bell-Irving (known in Vancouver business circles as H.O.), and Vancouver’s first solicitor, Alfred St. George Hamersley. Frank Holt, and his little shack at #1003, is completely ignored by the city directory that year. Frank first gets a listing in 1904, and new neighbor, real estate agent Edward Mahon.

Seaton Street, now West Hastings in 1925. Photo CVA 357-4

Seaton Street, now West Hastings in 1925. Photo CVA 357-4In the early years of the 20th Century, the bluebloods began to leave the alley for higher ground above English Bay, and by 1915, the road was an extension of Hastings Street west of Burrard, and just like the rich, the name disappeared.

Seaton Street/West Hastings 1000, 1100 and 1200 block today. Google Maps

Seaton Street/West Hastings 1000, 1100 and 1200 block today. Google Maps© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

April 15, 2017

The Marine Building and the Little House Next Door

W.J. Moore’s 1935 photo of the Marine Building, the Quadra Club and Frank Holt’s cabin. CVA BU N7

W.J. Moore’s 1935 photo of the Marine Building, the Quadra Club and Frank Holt’s cabin. CVA BU N7It’s hard to imagine today, but when the Marine Building opened in 1930 it was the tallest building in Vancouver and stayed that way for more than a decade. If you look at the photo (above), you can see that when architects McCarter and Nairne, designed it, four of the 22 floors were built into the cliff above the CPR railway tracks. You can also see the second version of the Quadra Club, and then what looks like an old shack perched on the edge of the cliff.

I recently came across this war-time newspaper advertorial by Vancouver Breweries Limited. It shows the same 1935 photo, and circled is “the oldest building in Vancouver.”

According to the story, part of a series called “Do you know Vancouver!” the tiny house was used by CPR land commissioner Lauchlan Hamilton when he was surveying Vancouver in 1885. “Using the old cottage as a mark, Hamilton set the lines of our present Hastings Street, on which the street system of Vancouver is based,” goes the story. “When John Buchan, Baron Tweedsmuir visited Vancouver for the last time as Governor General of Canada, his attention was called to this shabby little relic of our past. ‘I hope the people of Vancouver will preserve it!’ he exclaimed, fervently.”

Well, no sir, we did not.

The little house was built in 1875 as a mess hall for Spratt’s Oilery and originally had five rooms. It survived the Great Fire, and in 1894, Frank Holt moved in. When the cannery moved out, Holt stayed on. When Frank found out that four of the rooms were taxable because they were on city property, he tore them down, and stayed in the one-room shack. He was still living there in 1943 when the foundations started to give way and the front porch fell down the embankment. Frank, who was 90 at the time, helped workers install a new foundation.

Then in 1946 a fire broke out and trapped Frank in the house. Miraculously, firefighters found Frank in the debris and carried him to safety. The house was not so lucky.

Marine Building, photo courtesy Pricetags blog

Marine Building, photo courtesy Pricetags blogFrank came to Vancouver on the first transcontinental train. He was one of the founders of Christ Church Cathedral, and lived as a squatter in the one-room house in the shadow of the Marine Building for over half a century.

He died in December 1946, less than two months after his home burned down.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

April 8, 2017

Murder, Investigation, and a Dash of Forensics

Laura Yazedjian, coroner with the Police Museum’s Rozz Shipp

Laura Yazedjian, coroner with the Police Museum’s Rozz ShippThe first time I went to the Vancouver Police Museum was in the late 1980s. It was a breakfast meeting for a tourist organization called Vancouver AM, and we ate in the autopsy room. I fell in love with the place then in all its macabre glory, and nearly three decades later I still love going there.

Last night I was at a reception to launch the new true crime exhibit. I talked to plain clothes detectives, museum curators, librarians, a criminologist, a forensic anthropologist and a GIS specialist from the coroner’s office who have the grim, but rewarding job of matching remains to missing people—sometimes decades later.

Rosslyn Shipp by part of the new true crime exhibit

Rosslyn Shipp by part of the new true crime exhibitMuseum director, Rosslyn Shipp has spearheaded the changes, mostly on a shoestring budget, and transformed the old morgue in the process. The musty old wooden cases are gone, replaced by stories, case files, trace evidence and photographs from some of the most fascinating murders of last century. Rather than focus on the murder, the exhibits now tell the stories of the victims, putting them front and centre where they belong.

Sandra Boutilier and Carolyn Soltau, whose impending loss from the Sun/Province library will be keenly felt

Sandra Boutilier and Carolyn Soltau, whose impending loss from the Sun/Province library will be keenly feltThe Babes in the Woods, the Pauls and the Kosberg murders have been updated and joined by three more. There’s a skull of a farmer found in the 1970s. He’d been shot in the head and buried along the edge of a river. The remains were matched to a missing person’s report by the coroner’s office. There’s the story of Viano Alto, a night watchman who was shot and killed while on the job in 1959. And there’s the 1994 murder of David Curnick, stabbed 146 times with his own kitchen knife.

The axe used in the Kosberg murders

The axe used in the Kosberg murdersProper attention is now given to the work that went on in the building and its place in the evolution of forensics in Canada. John F.C.B. Vance, a city analyst and scientist (and the subject of my next book Blood, Sweat and Fear) has his place in the exhibit and much more emphasis is placed on the building’s history as the VPD crime lab (1932 to 1996).

Rozz is also the force behind the speaker series now in its 5th year. The series kicks off next Wednesday (April 12) with a talk by Heidi Currie on the Kosberg murders. I’ll be looking at the unsolved murder of 24-year-old Jennie Conroy in 1944, former homicide sergeant Kevin McLaren will walk us through the murder investigation of four members of the Etibako family and Ashley Singh in 2006, former VPD sergeant Brian Honeybourn talks about his time in the Provincial Unsolved Homicide Unit, and staff Sergeant Lindsey Houghton will address how the VPD investigates and prosecutes organized crime.

Book your tickets: https://vancouverpolicemuseum.ca/speaker-series/

The skull of a murdered farmer found in the 1970s

The skull of a murdered farmer found in the 1970s© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

April 1, 2017

The Missing Houses of Yaletown

Gord McCaw shot this photo of Percy Linden outside his home on June 26, 1986

Gord McCaw shot this photo of Percy Linden outside his home on June 26, 1986Do you remember the little house on Richards Street between Nelson and Helmcken? It was one of the last ones standing and for years had quite the garden and lots of funky birdhouses and wheelbarrows. I was reminded of it when Glen Mofford posted a photo that he took of owner Percy Linden outside his house in the summer of 2001. “The house appeared to be a hold out from another age when these Victorian era houses were all over the downtown core,” says Glen.

1021 Richards Street, built in 1907. Photo courtesy Glen Mofford, 2001.

1021 Richards Street, built in 1907. Photo courtesy Glen Mofford, 2001.Percy was an interesting guy. A former truck driver, he bought the house in the ‘50s, rented it out, and moved in there in 1970. At one time the house was a violin studio.

1021 Richards Street in 1975. Photo courtesy Vancouver Archives 780-43

1021 Richards Street in 1975. Photo courtesy Vancouver Archives 780-43“Percy Linden is familiar to east-of-Granville Street regulars, trundling his lawnmower along the sidewalks of the hookers’ strolls, an other-era figure in the shadow of the construction cranes above the old Yaletown warehouse district that flag the march uptown of condominium towers.” wrote Globe and Mail reporter Robert Williamson in 1993.

1000 block Richards Street, west-side in 1981. Courtesy Vancouver Archives 779-E08-36

1000 block Richards Street, west-side in 1981. Courtesy Vancouver Archives 779-E08-36That year, Percy won an award for his garden from the BC Society of Landscape Architects.

“I never, ever thought of what I do in terms of landscaping,” Percy told Williamson. “I didn’t have the faintest intention of even growing a weed. I just set out to clean up the yard, and it evolved, inch by inch. People talk about hours of planning. I didn’t put one second’s planning into it; I just dug wherever I felt like it.”

1000 block Richards Street, east side, 1981. Courtesy Vancouver Archives 779-E08-26

1000 block Richards Street, east side, 1981. Courtesy Vancouver Archives 779-E08-26The birdhouses—a collection of tiny farmhouses, barns, hotels and windmills, were inspired by Percy’s rural upbringing in Alberta. A little sign in the front yard read: “Take a little extra time today to stop and smell the roses long the way.”

Tour buses would stop outside his house, tourists snapped photographs, and others left fan mail in his mailbox. But every year, the house would seem to shrink a little more as a sea of high rises and condominiums grew up beside it.

1062 Richards Street in 2007. Courtesy Vancouver Sun

1062 Richards Street in 2007. Courtesy Vancouver SunNot long after Glen took his photo, Percy gave up his house and garden. And, then a few years later, a feisty little old lady named Linda Rupa, who owned a little cottage in the same block as Percy, gave in under the weight of a $36,000 annual property tax bill. The former Safeway cashier sold the one-time bootlegging joint that she’d owned since 1962 for $6 million.

“When I came in here, I had 17 phones, two private lines to the States and a big poker table upstairs,” she told Vancouver Sun reporter John Mackie in 2007. “It was a lovely neighbourhood, where people cared about each other.”

1000 block Richards Street today, via Google maps

1000 block Richards Street today, via Google maps© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

March 25, 2017

Heritage Streeters from Victoria (with Patrick Dunae, Tom Hawthorn and Eve Lazarus)

This is an occasional series that asks people who love history and heritage to tell us their favourite existing building and the one that never should have been torn down.

603 Manchester Road in Victoria’s Burnside-Gorge neighbourhood

603 Manchester Road in Victoria’s Burnside-Gorge neighbourhoodPatrick A. Dunae is a Victoria-born historian. A past member of the City of Victoria Heritage Advisory Panel, he is currently president of the Friends of the BC Archives.

Favourite Building:

One of my favourite houses is an unprepossessing, colonial-style bungalow on Manchester Road. The house was built in 1908 by Charles Deacon, who had emigrated from England with his family six years earlier, and became the foreman of a Rock Bay sawmill. I like the design and proportions of the house; and I applaud the current owners for painting the exterior a warm yellow, a colour that was popular when the house was built. This is an unfashionable part of Victoria and old houses like this are at risk. Kudos to City of Victoria Heritage Planners, who have recommended that the 600 block of Manchester and adjacent Dunedin Street, be designated as a Heritage Conservation Area. The proposal still needs to be approved by homeowners. Fingers crossed.

The Coburn family home at 2640 Blanshard, an Italianate-style house built in 1898.

The Coburn family home at 2640 Blanshard, an Italianate-style house built in 1898.The one that got away:

In the 1960s when “urban renewal” was popular and local authorities were eradicating “blighted areas,” Victoria City council used the program to demolish nearly 160 houses in its Rose-Blanshard Renewal Scheme. This “blighted” area consisted of houses built in the 1890s and early 1900s. Rose Street was its centre and North Ward School (1894), a four-storey brick structure, was a landmark. The school and neighbouring residences were demolished so that Blanshard Street could be widened to benefit motorists travelling from the new BC ferry terminal. Properties were expropriated, and occupants who refused to leave their homes were forcibly evicted. The Coburn family home was the last house standing when it was bulldozed in March 1969. It was replaced with Blanshard Court, a “low income housing estate,” now called Evergreen Terrace.

The Royal Bank building at 1108 Government St. in Victoria photographed in 1949 (BC Archives I-02169). The building was in disrepair when purchased by bookseller Jim Munro in 1984. The carved lettering in the granite facade above the entrance now read Munro’s Books of Victoria.

The Royal Bank building at 1108 Government St. in Victoria photographed in 1949 (BC Archives I-02169). The building was in disrepair when purchased by bookseller Jim Munro in 1984. The carved lettering in the granite facade above the entrance now read Munro’s Books of Victoria.Tom Hawthorn is a reporter, author and bookseller who lives in Victoria. His latest book The Year Canadians Lost Their Minds and Found Their Country, will hit bookshelves th is May.

Favourite Building:

My daily workplace is a magnificent former bank building. The Edwardian-era former Royal Bank of Canada at 1108 Government St. was in terrible disrepair when purchased (against his banker’s advice) by Jim Munro in 1984. He returned the structure to its former glory, notably removing a suspended ceiling added as part of a modernizing renovation in the 1950s. Today, tapered pilasters and a cast-plaster coffer ceiling attract tourists from around the globe eager to visit a bookstore co-founded in 1963 by future Nobel laureate Alice Munro. Designed in 1909 by local architect Thomas Hooper as a Temple Bank in the Classical Revival style, with an all-granite facade including two impressive Doric columns, Munro’s Books remains a temple to a commerce less pecuniary than literary.

Exhibition Building, Willows Fairgrounds, Oak Bay (Victoria) (BCArchives H-02390)

Exhibition Building, Willows Fairgrounds, Oak Bay (Victoria) (BCArchives H-02390)The one that got away:

In 1899, a grand exhibition hall with an adjacent horse racing track was built on farmland in Oak Bay. The roof stood 56 feet above the ground with central octagonal towers reaching to a height of 100 feet. An open cupola topped the impressive building, which dominated the Willows Fairgrounds like a manor house amid verdant lawns.

Among the visitors to the exhibition hall, which boasted 20,000 square feet of floor space surrounded by galleries, was the future King George V.

The building and the streetcar connection, that now extended from Royal Jubilee Hospital to the fairgrounds, spurred the growth of Oak Bay, which incorporated as a municipality in 1906. Alas, the building was destroyed by fire in 1907, to be replaced by a warehouse structure of little merit. The site of the fairgrounds was subdivided into housing after the Second World War with 10 acres reserved for Carnarvon Park.

Emily Carr’s Oak Bay cabin on Foul Bay Road. Eve Lazarus photo, 2012

Emily Carr’s Oak Bay cabin on Foul Bay Road. Eve Lazarus photo, 2012Eve Lazarus is a journalist, author and blogger who has a passion for unconventional history and a fascination with murder. She is the author of Cold Case Vancouver.

Favourite Building:

Emily Carr paid $900 for a plot of land on Victoria Avenue in 1913, and according to a story built the cottage “nail by nail” with the help of “one old carpenter.” After a bit of digging it turns out the carpenter was Thomas Cattarall, who built Craigdarroch for the Dunsmuir family and worked on Hatley Castle. In 1995, new owners wanted to build a house on the property but didn’t want to destroy the little cottage. Terry Tallentire stepped in, paid the city $1.00, spent another $4,000 to move it to her house, and it now lives behind a Samuel Maclure designed house on Foul Bay Road. (The full story is in Sensational Victoria).

The Wilson mansion at 730 Burdett Avenue, Victoria

The Wilson mansion at 730 Burdett Avenue, VictoriaThe one that got away:

There are many reasons why Victoria should have saved the Wilson Mansion, but perhaps the best one is because its social history is just so eccentric. There’s the overprotective father who surrounded it with high walls, Jane, the daughter who kept exotic birds in the attic and owned a 100 pairs of white gloves. And there’s the beneficiary of her will in 1949—Louis, a macaw parrot from South America, who was then in his eighties. Jane named Wah Wong, the Chinese gardener as trustee and parrot keeper, and the terms of the will stated that the property could not be sold while the birds were still alive. The feathered tenants managed to stave off developers until 1966, when it was bulldozed to make way for the Chateau Victoria Hotel.

For more on the series see:

Heritage Streeters with Bill Allman, Kristin Hardie and Pamela Post

Heritage Streeters with Anne Banner, Tom Carter, Kerry Gold and Anthony Norfolk

Heritage Streeters with Michael Kluckner, Jess Quan, Lani Russwurm and Lisa Anne Smith

Heritage Streeters with Caroline Adderson, Heather Gordon, Eve Lazarus, Cat Rose and Stevie Wilson

Heritage Streeters with John Atkin, Aaron Chapman, Jeremy Hood and Will Woods

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

March 18, 2017

Our Missing Heritage: The Birks Building. WTF were we thinking?

The Birks Building at Granville and Georgia (where the London Drugs store is today) was demolished in May 1974. Two months earlier, on March 24, a group of people got together and held a funeral. Angus McIntyre attended and took photos, and he has kindly written a guest blog about the building and its demise. All photos and captions are by Angus.

The funeral mourners assemble under the Birks clock for the ceremonial laying of the wreaths. Two ladies prepared handmade protest signs, one of which is visible on the far left. Angus McIntyre photo, 1974.

The funeral mourners assemble under the Birks clock for the ceremonial laying of the wreaths. Two ladies prepared handmade protest signs, one of which is visible on the far left. Angus McIntyre photo, 1974.Forty-three years ago this week, I rode my bike downtown to attend a funeral service. The weather was sunny and +10C, and since it was a Sunday, traffic was light, and the Granville Mall was still under construction. I saw the procession of mourners with a police escort coming from the old Vancouver Art Gallery on Georgia at Thurlow. I heard a small band playing a sombre funeral dirge. It looked like the old photos of funerals in Vancouver in the early 1900s.

This view of the Vancouver Birks store interior was taken from the top of the stairs leading up to the mezzanine. There was excellent natural light through the large windows, complemented by attractive incandescent light fixtures.

This view of the Vancouver Birks store interior was taken from the top of the stairs leading up to the mezzanine. There was excellent natural light through the large windows, complemented by attractive incandescent light fixtures.The funeral was put together by a group of staff and students from the UBC School of Architecture, and included architects and historians. As the service was about to start, crews working on the new building at Georgia and Granville shut off the air compressors and laid down their tools. There was a Gathering, a Sharing of Ideas, a Choir performance and a Laying of the Wreaths. A small group of people wearing recycled videotape clothing put hexes on new buildings nearby. As soon as it came time to return to the Art Gallery, the band switched to Dixieland jazz, and the mood became slightly more upbeat.

I am leaning out of an open arched window on the top floor of the Birks Building, and on the floor below me a terracotta man’s face is checking out the scene. The Granville Mall is under construction, the recently opened Eaton’s store has yet to have two additional floors added, and the view to the south is relatively unobstructed.

I am leaning out of an open arched window on the top floor of the Birks Building, and on the floor below me a terracotta man’s face is checking out the scene. The Granville Mall is under construction, the recently opened Eaton’s store has yet to have two additional floors added, and the view to the south is relatively unobstructed.I had been able to photograph the interior of the store through the courtesy of Thom Birks, and was even able to access the roof for some photos. I later presented him with a portfolio of images, and in return he gave me a framed print of the building. I had occasionally shopped there over the years, and the pneumatic tube system for purchases lasted almost to the end. When you entered the store for the first time, you couldn’t help but look up at the incredible ceiling detail. As Thom Birks looked at a model of the new tower to be built, he turned to me and said: “Of course, this interior could never be duplicated.”

This view shows the Birks sign on top of the Vancouver Block, taken from the roof of the Birks Building. The Vancouver Block survives to this day even though it was built in 1912, one year before the Birks building.

This view shows the Birks sign on top of the Vancouver Block, taken from the roof of the Birks Building. The Vancouver Block survives to this day even though it was built in 1912, one year before the Birks building.Demolition had already begun by the time of the funeral service, and it was fitting that enough people cared to have a farewell ceremony. The large R.I.P. banner ended up in a second storey office at the narrow Sam Kee building at Carrall and Pender Streets, visible as I drove my bus every day on the Stanley Park route.

There was some theatre involved in the service, and the wreaths were traditional, although I seem to recall one was made from an old car tire.

There was some theatre involved in the service, and the wreaths were traditional, although I seem to recall one was made from an old car tire.I visited Montreal years later, and was surprised to find Birks in an 1894 building. The store, with its incredible interior, was intact. It was sold recently to a developer for conversion to a boutique hotel, with plans to retain the original building and store. It is sad that Vancouver’s Birks Building did not get the same treatment.

Scaffolding is in place on the top of the Birks Building as the funeral ceremony takes place.

Scaffolding is in place on the top of the Birks Building as the funeral ceremony takes place.There are more of Angus’s photos and details of the funeral at Michael Kluckner’s blog

More about our missing heritage buildings—the Strand, Birks and the Second Hotel Vancouver

See Angus’s post on the Missing Elevator Operators of Vancouver

For more about Angus McIntyre

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.