Eve Lazarus's Blog: Every Place has a Story, page 32

December 15, 2018

The Unsolved Rape and Convent Murder of Albina Lequiea

On Sunday December 16, 1973, 96-year-old Albina Christiana Lequiea was found dead in her bed on the second floor of the Sisters of Saint Paul School in North Vancouver.

At first, it was thought that she had died from natural causes, but once her body was examined at Lions Gate Hospital, they found that she had been raped and strangled with a nylon stocking. She was still wearing her pink nightgown.

The convent is still there at 524 West Sixth Street, its name is now the Sisters of Instruction of the Child Jesus. The building became part of St. Thomas Aquinas High School in 2003 and backs onto Keith Road.

In 1973, when Albina was a resident, the convent also served as a home for the elderly.

One of the nuns told police that she had found a man in his early 20’s wandering inside the convent at around 3:30 in the morning. He had a beard and shoulder-length dirty blonde hair. He wore jeans, had “striking eyes,” and reeked of booze. He said to her: “Where’s the door? How do I get out?” After he left, she reported it to her superior, but not to the police.

Later they found that he had got in by smashing a glass panel in the front door.

A few days later the Vancouver Sun ran a story with the headline “Psychopathic killer hunted in strangling at convent.”

There was nothing mentioned about Albina’s long life, so I went searching for a death certificate to find out where she was born. Instead, I found an article written in 2007 by Elizabeth Withey, Albina’s great granddaughter.

According to Withey’s story, she was born Albina Christiana Proulx in Nicolet, Quebec in 1877. When she was 19, she married Phillip Lequiea and they raised nine children on a farm near Battleford, Saskatchewan. Albina was a “fervent catholic” who was “tiny, gentle and devoted to her family and God.” She went to church every morning before breakfast, and it must have made her happy that one of her sons became a priest.

Ed Lequiea led the funeral mass for his mother.

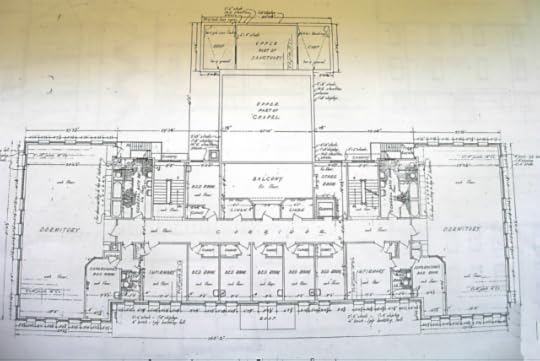

The second floor of the convent. Courtesy NVMA and Churches on Sundays blog

The second floor of the convent. Courtesy NVMA and Churches on Sundays blogEven with the description by the nun and a composite drawing that ran in the newspapers, Albina’s murderer was never found. His description sounds remarkably like the one that was given to police after the murder of 16-year-old Rhona Duncan less than three years later. Rhona had been raped and strangled on her way home from a party at 15th and Bewicke, just blocks from the convent.

Rhona’s murder is detailed in a chapter of Cold Case Vancouver: The City’s Most Baffling Unsolved Murders.

The murders of Albina Lequiea and Rhona Duncan are two of North Vancouver’s 17 unsolved cases dating back to 1964. After 2003, new investigations were transferred to IHIT—the RCMP’s Integrated Homicide Investigation Team.

Top photo: courtesy North Vancouver Museum and Archives #3444 and Suzanne Wilson’s blog: Churches on Sundays

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

December 8, 2018

Lolly, CFUN, and the Brill Trolley Bus

Angus McIntyre was reading Murder by Milkshake when he stopped and took a closer look at a photo snapped by the Vancouver Sun’s Dan Scott in December 1966.

Angus McIntyre was reading Murder by Milkshake when he stopped and took a closer look at a photo snapped by the Vancouver Sun’s Dan Scott in December 1966.

Where I saw a rare photo of Lolly Miller leaving court during the murder trial of her lover, Rene Castellani—Angus was looking at the background.

“I just noticed something about Lolly Miller’s photo on page 58,” said Angus, who was a Vancouver bus driver for 40 years. “In the background there is a Brill trolley bus, with the B.C. Hydro logo visible. On the side there is an advertisement–this was for a disc jockey on CFUN, Tom Peacock.”

The ad reads “Tom Peacock. Afternoons 3 to 6.”

Radio plays a prominent part in Murder by Milkshake. In 1965, CKNW personality Rene Castellani murdered his wife Esther with arsenic so he could marry the station’s 20-something receptionist Lolly Miller.

Brill trolley bus in 1969, Angus McIntyre photo

Brill trolley bus in 1969, Angus McIntyre photo“I just thought it was ironic that behind Lolly there was an ad for a rival radio station,” says Angus who moved to Vancouver in 1965.

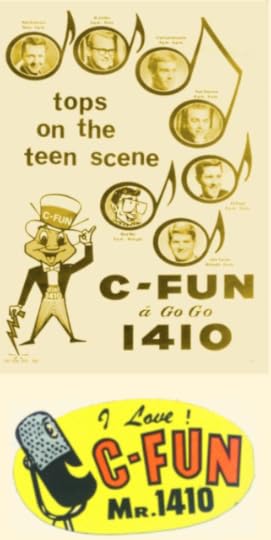

“CFUN had a request line phone number, REgent 1-0000, promoted as ‘REgent ten-thousand, CFUN Requestomatic’. It almost always had a busy signal in the days of relay switches in the telephone exchanges, and kids would yell out their phone numbers over the sound of the busy signal to get a call back,” says Angus. “Some of their contests had so many people phone in that parts of the REgent exchange would crash.”

During the ’50s and ’60s, CKNW, the Top Dog, was a familiar sight in the community. Courtesy CVA 180-2127

During the ’50s and ’60s, CKNW, the Top Dog, was a familiar sight in the community. Courtesy CVA 180-2127According to his broadcast bio, Peacock eventually moved to CKWX (1130) and became the station’s general manager. He died in 2006, at age 67.

In 1965, CKNW was still the “Top Dog,” and as George Garrett, a news reporter for the station for over four decades, told me, “We were the most promotions minded station you could imagine.” The station’s deejays included Jack Cullen, Jack Webster and Norm Grohmann. Over at CFUN, a top 40-station at the time, deejays (below) were Red Robinson, Al Jordan, Fred Latremouille, Tom Peacock, Ed Kargl, Mad Mel, and John Tanner.

It depends what source you look at, but I find it hard to argue with thoughtco.com’s top 10 picks of 1965:

I Can’t Get No Satisfaction; The Rolling Stones

Like a Rolling Stone; Bob Dylan

A Change is Gonna Come; Sam Cooke

Tambourine Man; The Byrds

Ticket to Ride; The Beatles

I’ve Been Loving You Too Long; Otis Redding

Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag; James Brown

My Girl; The Temptations

Stop! In the Name of Love; The Supremes

Do you Believe in Magic?; The Lovin’ Spoonful

Top photo: Lolly Miller. Photo by Dan Scott/Vancouver Sun [PNG Merlin Archive]

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

December 1, 2018

Saving History: The Woodward’s Christmas Windows

When David Rowland heard that Woodward’s was closing in 1993, he phoned up the manager and put in an offer for the department store’s historic Christmas windows. They agreed on a price, and Rowland became the proud owner of six semi-trailer loads of animated teddy bears, elves, geese, children, a horse and cart and various storefronts.

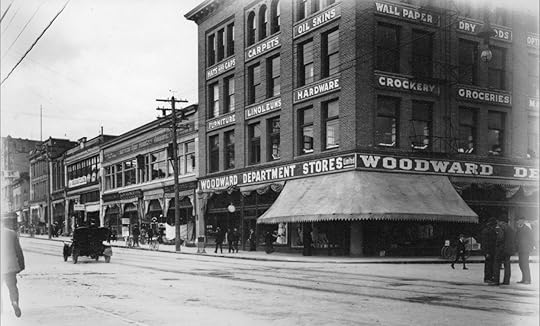

Woodward’s ca.1907. Courtesy Vancouver Archives 677-611

Woodward’s ca.1907. Courtesy Vancouver Archives 677-611In the late 1960s, 14-year-old Rowland rode the bus into Vancouver carrying three samples of puppets and marionettes that he had made. He walked up and down what was then Robsonstrasse trying to interest toy store owners into buying his merchandise.

“They said ‘they are nice little toys, and you are a nice little boy, but come back when you have sold them somewhere else’,” says Rowland. “I was about to give up and I thought well there’s always The Bay.”

Rowland found the manager of Toyland and put his marionettes through their paces.

“A lot of people gathered and shoppers started picking up the boxes looking for prices.”

The manager ordered 50 and had Rowland come in and demonstrate them every Saturday. Later he invented a coin-operated puppet theatre where you put 25 cents in and the lights turned on and music played and the puppets danced across the stage. He sold three dozen of them to shopping centres in B.C. As requests came in to build Santa’s castles and other seasonal structures, Rowland’s business took off.

Original figures made by David Rowland for Woodward’s in the ’70s. Courtesy David Rowland

Original figures made by David Rowland for Woodward’s in the ’70s. Courtesy David RowlandWoodward’s started getting serious about their Christmas windows in the 1960s, and sent buyers off to New York to bring back different figures. The department store hired Rowland in the ‘70s to create mechanical figures for their Toyland and display work for their windows.

When Rowland unpacked his newly acquired Christmas windows in the ‘90s, he found at least a dozen different scenes. He looked around for a venue big enough to display them and found himself at Canada Place. Rowland wanted to rent them, but Canada Place offered to buy them outright. “That wasn’t my initial plan, but at the time I had a banker from hell and I needed some capital and so I sold a lot of it to them,” he says.

Christmas window display at the Grosvenor Building. Courtesy David Rowland

Christmas window display at the Grosvenor Building. Courtesy David RowlandRowland couldn’t bear to part with all of them though, and every year he sets up a few in buildings around Vancouver. You can catch some of the former Woodward’s Christmas windows and Rowland’s own work at:

The Grosvenor Building: 1040 West Georgia Street

FortisBC: 1111 West Georgia Street

BCAA lobby: 4567 Canada Way, Burnaby

The promenade at Canada Place

Christmas window display at FortisBC building. Courtesy David Rowland

Christmas window display at FortisBC building. Courtesy David RowlandTop photo: David Rowland putting together a former Woodward’s Christmas window in 2010 for Canada Place. Courtesy David Rowland.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

November 24, 2018

Our Missing Heritage: The Ritz Hotel

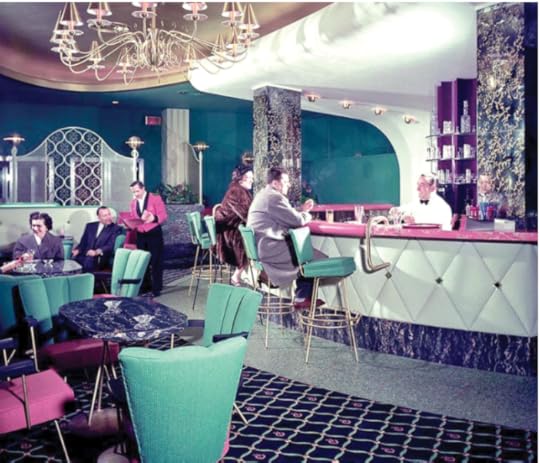

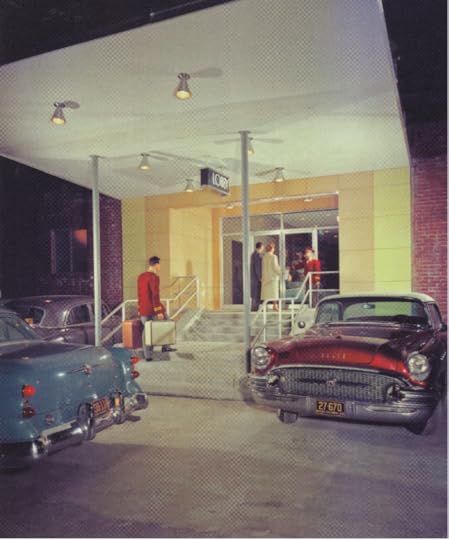

Selwyn Pullan shot these photos of the Ritz Hotel in 1956, shortly after it had been renovated into this awesome mid-century modern look.

Selwyn Pullan shot these photos of the Ritz Hotel in 1956, shortly after it had been renovated into this awesome mid-century modern look.

But while it had a fancy name, the Ritz Hotel at 1040 West Georgia was originally designed as a YMCA in 1912 by Henry Sandham Griffith. Griffith had offices in Vancouver and Victoria and was riding the real estate boom of the time. He made enough money to build himself a castle-like manor he named Fort Garry on Cook Street in Victoria, that later belonged to David Spencer and became known as Spencer’s Castle. It’s now part of a condo development.

St. Julien Apartments, 1924. Designed as a 7-storey reinforced concrete building at a cost of $375,000. Photo: CVA 99-1411

St. Julien Apartments, 1924. Designed as a 7-storey reinforced concrete building at a cost of $375,000. Photo: CVA 99-1411Unfortunately for the YMCA, the economy tanked in 1913, the First World War broke out the following year and the Y couldn’t raise the money to finish the building. It sold, and was completed as the St. Julien Apartments in 1924. Radio Station CJOR launched in 1926, and shared the building for the next three years.

St. Julien Apartments, 1929. Designed by H.S. Griffith in 1912. The only two Vancouver buildings that still exist of his work are the Board of Trade, 402 West Pender and the West End’s Barrymore Apartments on Barclay. Photo: VPL 4759

St. Julien Apartments, 1929. Designed by H.S. Griffith in 1912. The only two Vancouver buildings that still exist of his work are the Board of Trade, 402 West Pender and the West End’s Barrymore Apartments on Barclay. Photo: VPL 4759The St. Julien Apartments didn’t last long. By 1929, it had transformed into the Ritz Apartment Hotel, offering hotel rooms and fully serviced apartments. One of its long-term residents was Mabel Ellen (Springer) Boultbee, a divorcee who is said to be the first white child born on Burrard Inlet. She was born in Moodyville in 1875 and died in her room at the hotel 77 years later. She shared the apartment with her sister Eva.

Ritz Hotel in 1957. Photo VPL 42418

Ritz Hotel in 1957. Photo VPL 42418Mabel and Eva ran a school together in the 1890s, and Mabel wrote for the Vancouver Sun’s women’s pages for 30 years. She was also a member of the swanky women-only Georgian Club which occupied the top floor of the Ritz Hotel from 1947 until the building’s untimely demise in 1982.

One of a series of photos taken from the roof of the Ritz Hotel in 1948. Photo: VPL 80734.

One of a series of photos taken from the roof of the Ritz Hotel in 1948. Photo: VPL 80734.The Devonshire Hotel—our other much loved and storied building just two blocks away on West Georgia, came down in 1981, replaced by the HSBC building.

The Georgia-Medical Dental Building is under construction in this 1929 Leonard Frank photo. The Devonshire is in the middle. Both buildings are long gone.

The Georgia-Medical Dental Building is under construction in this 1929 Leonard Frank photo. The Devonshire is in the middle. Both buildings are long gone.The Ritz Hotel was replaced by the 22-storey hideous gold Grosvenor building.

The Grosvenor Building replaced the Ritz Hotel in 1983 and boasts 12 corner offices on every floor. Photo: Emporis

The Grosvenor Building replaced the Ritz Hotel in 1983 and boasts 12 corner offices on every floor. Photo: EmporisWith thanks to:

the Vancouver Public Library and BC City Directories

Chuck Davis’s Vancouverhistory.ca

Changing Vancouver blog

Building the West: Early Architects of British Columbia by Don Luxton

Find a Grave

To find out more about fabulous buildings that no longer exist – go to: Our Missing Heritage

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

November 17, 2018

Riding the Spirit Trail to West Vancouver Part 7

Lots of history to cover on this last leg of the Spirit Trail. We’re starting at Park Royal, which when it opened in 1950, was the first covered mall in Canada.

Lots of history to cover on this last leg of the Spirit Trail. We’re starting at Park Royal, which when it opened in 1950, was the first covered mall in Canada.

Prior to 1965, most of the land you’re riding on was swamp. Ambleside Beach is the product of 85,000 cubic metres of sand and gravel hauled from the sandbanks west of Navvy Jack Point. The pitch-and-putt is built on sawdust, bark and wood waste from a North Vancouver sawmill, and the duck lagoon used to be part of a slough.

Ambleside Beach, 1918. Courtesy WVA

Ambleside Beach, 1918. Courtesy WVAIf you look to the right, you’ll see the Ambleside Youth Centre. Before that it was the West Vancouver Rod and Gun Club, and before that it was one of 18 huts built by the Department of National Defence with four gun emplacements and anti-aircraft guns to defend the harbour entrance below the Lions Gate Bridge during World War 11. After the war, the District of West Vancouver bought the huts and converted them into housing for war vets and their families.

Ambleside Pool opened in 1954 and was gone by 1977. Courtesy WVA 1954

Ambleside Pool opened in 1954 and was gone by 1977. Courtesy WVA 1954The huts were built on low land that flooded several times a year, and at those times, food and supplies were brought in by rowboat. By 1961, three were moved to the high school for classrooms and the others were destroyed.

Ferry Building, courtesy District of West Vancouver

Ferry Building, courtesy District of West VancouverYou’ll come out onto Argyle Avenue and soon see the Ferry Building. Before it was a quaint little art gallery, it was the headquarters of West Vancouver’s ferries which operated until 1947 from a dock at the foot of 14th Street. On a good day, the ferry trip to Vancouver took 25 minutes. Too bad we don’t still have service.

You’ll pass the imposing 16-foot high Welcome Figure that faces Stanley Park—a gift from the Squamish Nation to the people of West Vancouver in 2001.

Silk Purse. Courtesy District of West Vancouver

Silk Purse. Courtesy District of West VancouverAnd then you’ll see the Silk Purse—one of the last examples of the summer cottages that used to dot the area before the Lions Gate Bridge opened in 1938. Built in 1925, former Vancouver Mayor Tom Campbell inherited the cottage from his father, and in 1969, sold it to John Rowland. Rowland’s son him he was trying to make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear. The name stuck and he rented out the Silk Purse as a ‘honeymoon cottage’ for $12 a night, including breakfast and champagne. The District of West Vancouver has owned the Silk Purse since 1991 and it is operated by the West Vancouver Community Arts Council.

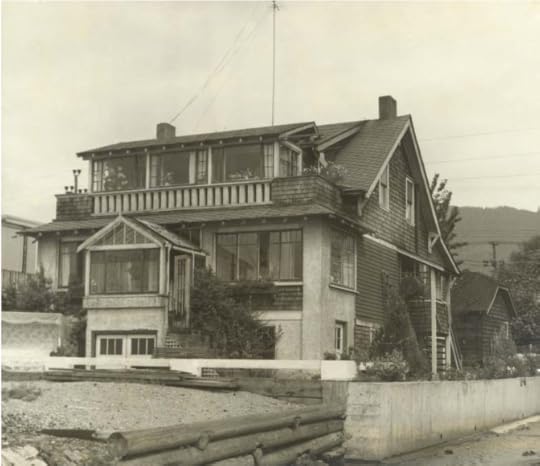

NavvyJack/John Lawson house in 1957. Courtesy WVA

NavvyJack/John Lawson house in 1957. Courtesy WVAYou’ll soon be at John Lawson Park, named for the man known as the “father of West Vancouver.” John was a mover and shaker in the West Vancouver business community. In the early 1900s, he bought Navvy Jack’s former house (1768 Argyle) and lived there until 1928. The house—the oldest on the North Shore—is unrecognizable from old photographs. Another victim of demolition by neglect.

Navvy Jack/John Lawson House 2018. Eve Lazarus photo

Navvy Jack/John Lawson House 2018. Eve Lazarus photoTop photo: Park Royal Shopping Centre in 1949

With thanks and gratitude to North Vancouver Museum and Archives.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

November 10, 2018

Riding the Spirit Trail from Pemberton Avenue to the Capilano River (Part 6)

Last week we stopped our ride at Pemberton Avenue. Today we’re going to cross the border into West Vancouver.

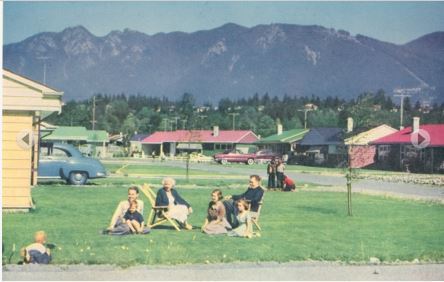

The first part of the Spirit Trail winds through Norgate, a quiet neighbourhood filled with mid-century ranchers built during the post-war boom period. But did you know that the whole area was originally intended to be the Capilano Air Park?

A typical Norgate rancher along the Spirit Trail. Eve Lazarus photo, 2018

A typical Norgate rancher along the Spirit Trail. Eve Lazarus photo, 2018It was first proposed in 1945 and the idea was that it would cater to tourists flying their own planes from other parts of North America. There would be two runways and construction would start in 1947 and include luxury accommodation. In the end, we couldn’t afford it and the land was sold to Hullah Construction for a subdivision.

1950s newspaper ad promoting Norgate as a family-friendly neighbourhood. Courtesy NVMA

1950s newspaper ad promoting Norgate as a family-friendly neighbourhood. Courtesy NVMAAfter we pass through Norgate, it’s a quick ride to the road that leads to the Lions Gate Bridge, built in 1939 by the Guinness brewing family. The provincial government later bought the bridge and the toll came off in 1963.

Now a National Historic Site of Canada. Photo courtesy Vancouver Sun

Now a National Historic Site of Canada. Photo courtesy Vancouver SunIn 1982, a group of UBC engineering students suspended a Volkswagen Beetle from the bridge. On the first night, a group of students attached a cable under the bridge. On the second night, students drove a jeep towing the reinforced Beetle. The students detached the car, slipped a cable under its roof, attached the other end to the side of the bridge, and pushed the car over the railings.

Courtesy: http://bit.ly/2AYeavn, 1982

Courtesy: http://bit.ly/2AYeavn, 1982As we approach the Capilano River and West Vancouver, it’s pretty clear that the district (named by Macleans Magazine as the richest postal code in Canada last year) is not spending its net worth on the Spirit Trail. In fact, it’s lack of enthusiasm is downright dangerous as you cross the bridge that takes you over to Ambleside.

But in 1913, it wasn’t cars that you had to worry about. The sand and gravel that washed down the Capilano River had built up on the north side of First Narrows to such an extent that ships were grounding, especially in bad weather. In July of that year, George Alfred Harris became the first lightkeeper at the newly constructed First Narrows Lighthouse.

The Capilano Fog and Light Station 1914. Coutesy WVA 0032.WVA.PHO

The Capilano Fog and Light Station 1914. Coutesy WVA 0032.WVA.PHOThe lighthouse, and the keeper’s house sat on pilings at the mouth of the Capilano River, and except for very low tide, the Harris family was surrounded by water. The lighthouse operated until 1968.

Top photo: Walking over the Lions Gate Bridge in 1939. Courtesy CVA 260-995

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

Next time, we’ll be riding through Ambleside and along to Dundarave where the Spirit Trail ends for now.

If you’ve missed any of the rides, please see:

The North Shore’s Spirit Trail – Moodyville (part 1)

Moodyville to Lonsdale Quay (part 2)

November 2, 2018

Riding the Spirit Trail – from Mosquito Creek to Pemberton Avenue (part 5)

At the end of our last post, we were watching harbour seals at Mosquito Creek. Now we’re going to take the Spirit Trail to Harbourside. While you may see a large tract of vacant land, as well as some businesses, a Spa Utopia, and an auto mall–developers see 700 condos, office space, retail stores, and a hotel.

Did you know that all the land at the bottom of Fell Avenue used to be tidal flats? In the late 1800s, James Pemberton Fell and his uncle Arthur Heywood-Lonsdale, bought District Lot 265 which included the foreshore rights. James had lofty goals that included a million-dollar marina and industrial complex. He got as far as building a seawall and creating 21 acres (8.5 hectares) of additional land before the Great War hit and all infrastructure plans were put on hold.

So, over 100 years later, let’s not go counting those condos until they’re hatched.

Eve Lazarus photo, 2018

Eve Lazarus photo, 2018Back on our bikes we’re going to ride along the waterfront past the off-leash dog park and take a hard right up Kings Mill Walk and the Harbourside West Overpass and onto Pemberton Avenue.

In the early 1900s several different flumes in North Vancouver transported logs and shingle bolts from the forests to the sea. They were long wooden chutes filled with running water, used by loggers like conveyor belts to float cedar shingle bolts from the hills above to the mills below.

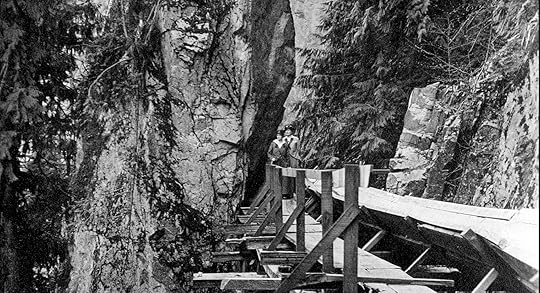

Close up of the Capilano River flume in 1916. People used to walk along it in their Sunday best. Courtesy CVA 21-42

Close up of the Capilano River flume in 1916. People used to walk along it in their Sunday best. Courtesy CVA 21-42The Capilano River flume was the longest at over 12 kilometres in length. Built in 1905, it ran from Sisters Creek, just north of where the Capilano Reservoir is today, to a mill at the foot of Pemberton Avenue. The flume had a catwalk that ran alongside it so crews could do maintenance, but it was also accessible to the public.

In the early part of the 20th century the Capilano Timber Company had its own railway for transporting fir, hemlock and cedar logs from the upper Capilano valley to the firm’s grounds near the foot of Pemberton. The railway ran down the west side of the Capilano River, crossed the river and headed eastward, running along what is now the Bowser Trail behind Save on Foods. The train crossed Pemberton and Marine drive and headed south and lasted until the early 1930s.

Capilano River Flume (on left) for cedar shakes in 1900. Courtesy CVA 122-1

Capilano River Flume (on left) for cedar shakes in 1900. Courtesy CVA 122-1In the 1970s, Pemberton Avenue almost became the jumping off point for the North Shore’s third crossing. Alderman Warnett Kennedy, an architect and town planner lobbied for a tunnel under Thurlow Street that would carry cars and rapid transit to the North Shore over the world’s biggest cable bridge, and exit at Pemberton Avenue.

Instead, you’ll find Vancouver Shipyards and the headquarters of Seaspan, the largest tug and barge company in Canada. After winning a federal government contract in 2011 to build 17 ships that include a Polar-class icebreaker for the Coast Guard, the company built a new office on the western spit of the Seaspan property. Seaspan expects to fill it with more than 1,300 new shipbuilding and office staff by 2020.

Seaspan’s new offices, 2018. Courtesy Seaspan

Seaspan’s new offices, 2018. Courtesy SeaspanNext post we’ll be winding through Norgate to Ambleside.

If you missed the first three legs catch up here:

The North Shore’s Spirit Trail – Moodyville (part 1)

Moodyville to Lonsdale Quay (part 2)

Top sketch: from Concert developers

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

October 19, 2018

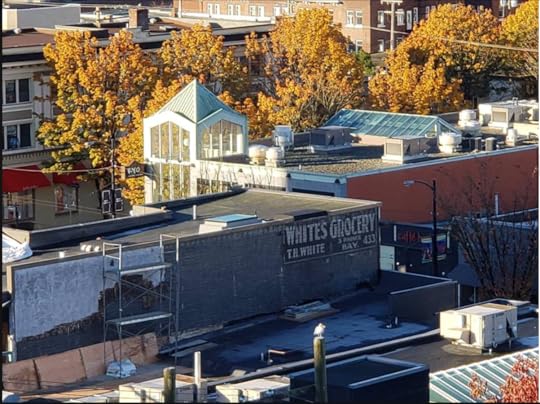

Ghost Signs: White’s Grocery of South Granville

Last Sunday when Fatidjah Nestman looked out of her high-rise on West 13th near Granville she noticed that an old ad for White’s Grocery had popped up when construction workers removed the cement siding from a building at 2932 Granville Street. Her neighbor, Karen Fiorini, took this picture of the ghost sign and kindly sent it to me.

“I wonder how old this is?” Nestman wrote. “The phone number Bay 433 predates the ‘60s.”

It certainly does.

White’s Grocery, a neighborhood store, was at that location from 1915 when the building first appears in the city directories, until 1931. It was owned by Thomas and Mary White, who also lived nearby on 13th Avenue.

Whites Grocery’s second store at 3039 Granville

Whites Grocery’s second store at 3039 GranvilleIn 1932, the Whites moved to a new building in the next block at #3039, and their former store became Treasures and Oriental Goods, owned and operated by a Mrs. Clark who lived in an apartment above. Mrs. Clark ran the store until 1950 when it changed to D’Arcy’s photography studio.

In 2018, the ground floor retail store at 2932 Granville belongs to Lord’s Shoes. The building sits next to a newer building with an upmarket Le Creuset Cookware downstairs and a Korean BBQ upstairs.

Found on a building at Granville & Robson in 2012. Vancouver Sun

Found on a building at Granville & Robson in 2012. Vancouver SunOn Monday, Fatidjah sent me this message: “Good thing we got the photo yesterday, today they are nailing siding over it,” she said. “It was a dream, now it’s gone, I wonder if the workers took any photos?”

I highly doubt it. But I guess that’s why they’re called ghost signs, because of their ephemeral existence.

Ghost sign for the Royal Crown Soap Company. Courtesy Lani Russwurm, 2018

Ghost sign for the Royal Crown Soap Company. Courtesy Lani Russwurm, 2018Other signs that have popped up from that era include Rennie Seeds in False Creek, Shelly’s Bakery on Victoria Drive, Moneys Mushrooms on Prior Street, Wildrose Flower in Chinatown and Royal Crown Soap on the London Hotel on East Georgia and Main Street.

Restored ghost sign at 1190 Victoria Drive, Google Maps.

Restored ghost sign at 1190 Victoria Drive, Google Maps.For more on ghost signs see Lani Russwurm’s great piece at Past Tense Vancouver

And, if you know of any others currently standing, please send me a photo and location!

We’ll continue our ride along the North Shore’s Spirit Trail in November

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

October 12, 2018

The North Shore’s Spirit Trail – Mosquito Creek – (part 4)

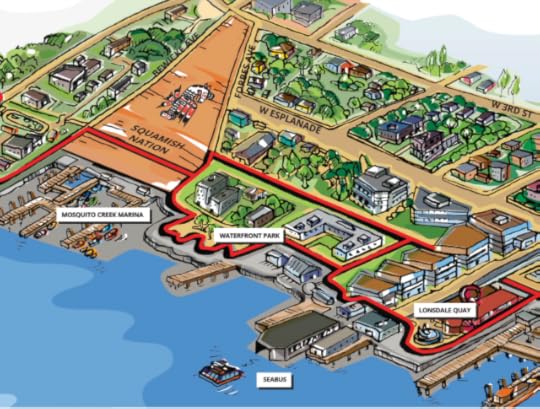

Last week we left off at the Shipyards Coffee at Lonsdale Quay. Grab your bike and we’ll ride the Spirit Trail down Cates court, loop around Waterfront Park and enter Squamish Nation land.

The Coast Salish aboriginal people established a permanent village called Slah-ahn (also known as Ustlawn or Eslha7an), meaning “head bay” in the 1860s. The village was located along a stretch of mudflat at the mouth of Mosquito Creek.

Mission Reserve 1908. Courtesy CVA SGN 52

Mission Reserve 1908. Courtesy CVA SGN 52With the arrival of European settlers, it became known as Mission Indian Reserve No. 1—the first permanent settlement on the north shore of Burrard Inlet.

Emily Carr used to visit her friend Sophie Frank, a Squamish basket maker who lived at Mission Reserve and both she and E.J. Hughes painted the area.

Emily Carr painting, 1908. Courtesy BC Archives

Emily Carr painting, 1908. Courtesy BC ArchivesIn 1932, the Mission Reserve Lacrosse team won the BC Championship—they were that good. The team consisted mostly of members from the Baker, Paull, and George families, who took up the game, because as Simon Baker told a North Shore Press writer, they had nothing else to do during the Depression. “We used to practice and practice and that’s how we became famous in lacrosse. We used to pass that ball, push it in circles real fast. We were good stick handlers,” he said. The team was disbanded after the win because they couldn’t get a sponsor.

Eve Lazarus photo

Eve Lazarus photoYou’ll notice a vibrant community of houseboats. A diner called the High Boat Cafe, and some great art. You can also see the 1884 St. Paul’s Church with its twin spires and gothic revival style.

Eve Lazarus photo.

Eve Lazarus photo.Over the years, the natural course of Mosquito creek has been altered by logging, landfills, and new subdivisions, destroying much of the natural habitat and salmon. Much of that is being restored and rehabilitated.

The most recent portion of the Spirit Trail was just finished this year. It runs below sea level and dips under the boat lifts at the marina. Each time we’ve been there so has a ‘haggle’ of harbour seals, sunning themselves on the wood (behind me) or swimming by the trail.

Watching the harbour seals at Mosquito Creek

Watching the harbour seals at Mosquito CreekWith thanks to the NVMA which makes all this research possible.

Next Week: Harbourside to Norgate.

If you missed the first two legs catch up here:

The North Shore’s Spirit Trail – Moodyville (part 1)

Moodyville to Lonsdale Quay (part 2)

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

October 6, 2018

The North Shore’s Spirit Trail – Lonsdale Quay (part 3)

There’s so much history at Lonsdale Quay, that I thought we’d stay here and let it roll over us while we caffeinate at the Bean around the World (now the Shipyards)

There’s so much history at Lonsdale Quay, that I thought we’d stay here and let it roll over us while we caffeinate at the Bean around the World (now the Shipyards)

If we time travelled back to the late 1880s, we’d be sitting on Tom Turner “ranch.” It stretched from Chesterfield to Rogers Avenue and sloped down from Esplanade to the water. The farm house sat roughly in the middle—where ICBC is today. Turner’s farm supplied vegetables to Moodyville residents, and because he had the only grass field in North Vancouver, his farm became a picnic destination for the locals. Turner later sold the property to J.C. Keith (namesake of Keith Road) and returned to England.

North Vancouver Hotel ca.1905. CVA OUT P575.1

North Vancouver Hotel ca.1905. CVA OUT P575.1In those days, Esplanade was a wide tree-lined promenade that extended west along the shoreline from Lonsdale to just past Chesterfield. The Hotel North Vancouver and its Pavilion were on the north side of the street, where the Shoppers Drug Mart is today. The hotel, owned by Pete Larson, attracted people from all over Vancouver who took the ferry and stayed for $2 a day or $10 a week, or just came for the day to check out the bandstand, balloon flights or perhaps tight-rope walking. The hotel’s grounds also had a boat dock and a swimming beach, because in those days the water reached to just below Esplanade.

North Vancouver train tunnel opening in 1928. Courtesy NVMA

North Vancouver train tunnel opening in 1928. Courtesy NVMAUnless you’ve been stuck at the foot of Chesterfield Avenue waiting for a train to pass, you’ve probably not given much thought to “the Lonsdale Subway.” The Subway is actually a 1,585 foot tunnel, built in the late 1920s to link two railways. The tunnel ran from St. Georges to Chesterfield and connected the Terminal Railway to the Pacific Great Eastern Railway (later BC Rail, then CN Rail).

At the foot of Lonsdale in the 1970s. NVMA 15806

At the foot of Lonsdale in the 1970s. NVMA 15806Most North Vancouver residents will remember the Seven Seas, a restaurant that was moored at the foot of Lonsdale. Some of you may even remember it as Norvan Ferry #5, a forerunner to the Seabus, and one of the ferries that brought people to Vancouver and back. Ferry #5 went into service in 1941 and was sold to restauranteur Harry Almas for $12,000 in 1959, a year after the ferries took their last run across the Inlet.

The Seabus in 1977. Courtesy NVMA

The Seabus in 1977. Courtesy NVMAAfter the Seabus launched in 1977 and kick-started economic activity in Lower Lonsdale, a plan was hatched for the Lonsdale Quay development. The thought was that densification of the area, with over 300 housing units, restaurants and shops would be encouraged, but care would also be taken to restore the heritage buildings in the corridor. Mayor Jack Loucks was certainly optimistic. “It has been said that Lonsdale Quay will become an extension of Granville Street,” he said. “I like to think that when the project is complete, Granville Street will become an extension of Lonsdale Avenue.”

Eve Lazarus photo

Eve Lazarus photoWell, perhaps not. More like a parking lot for billionaires and their luxury yachts.

Next week we’re getting back on our bikes and cycling the newest part of the Spirit Trail from Lonsdale Quay to Mosquito Creek.

*Top photo: View of North Vancouver west of Lonsdale Avenue showing Tom Turner’s cabin in 1890. Courtesy CVA OUT P79

If you missed the first two legs catch up here:

The North Shore’s Spirit Trail – Moodyville (part 1)

Moodyville to Lonsdale Quay (part 2)

The © All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.