Eve Lazarus's Blog: Every Place has a Story, page 30

April 20, 2019

The Kitsilano Laneway House

There’s been a lot about laneway houses in the media over the last couple of years. Loosely defined, it’s a legal way of plonking down a small house in your backyard, and depending on your point of view, either exploiting or helping to ease the current rental squeeze.

Laneway houses have to be under 1,000 square feet.

April 12, 2019

Episode 03: The Suspicious Death of Stewart Ashley

On April 13, 1933, 19-year-old Stewart Ashley went to work out at the YMCA in downtown Vancouver. He didn’t come home. A short time later, a ransom note arrived. It said: “Get $5,000 by April 20 or your son will die.”

Music Credits:

Intro and outro: Duke Ellington’s St.

Episode 3: The Suspicious Death of Stewart Ashley

On April 13, 1933, 19-year-old Stewart Ashley went to work out at the YMCA in downtown Vancouver. He didn’t come home. A short time later, a ransom note arrived. It said: “Get $5,000 by April 20 or your son will die.” Ten days later, Stewart’s body was found on the old Songhees Reserve near Victoria.

April 6, 2019

Streetcar Advertising and the Hobby Lobby Radio Show

My friend, Angus McIntyre emailed me these amazing photos of streetcar advertising that he came across on the Vancouver Archives site this week.

Courtesy CVA 586-1872, 1944

Courtesy CVA 586-1872, 1944The first photo shows Car 211 on the #3 Davie Street route passing the 400-block Granville Street. According to Angus, it was a two-man car, where you would board at the rear and pay the conductor.

Don Coltman, 1943. Courtesy CVA 586-1039

Don Coltman, 1943. Courtesy CVA 586-1039The photos were commissioned by a company called Canadian Street Car Advertising, and the photographer was Don Coltman, who bought Steffens-Colmer Studio in 1944 and took a lot of these fantastic “noir” photos during wartime Vancouver.

Courtesy CVA 586-1873, 1944

Courtesy CVA 586-1873, 1944The ad on the front of the streetcars for Dave Elman’s Hobby Lobby Stage Revue is fascinating. According to Wikipedia, 22-year-old, Dave Elman started his entertainment career on the vaudeville circuit as the “the world’s youngest and fastest hypnotist” in 1922. He was a song writer and moved into radio. In 1937 he approached NBC with an idea for his own show “Hobby Lobby.” The premise was that anybody could advocate for their hobby—the weirder the better—and the most interesting were asked to come on the show and “lobby for their hobby.” Guests included a woman who hypnotized crocodiles, a man who put hot coals in his mouth and cooked bacon on his face, and a fingerless pianist. When Elman went on holidays in 1939, first Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was his replacement.

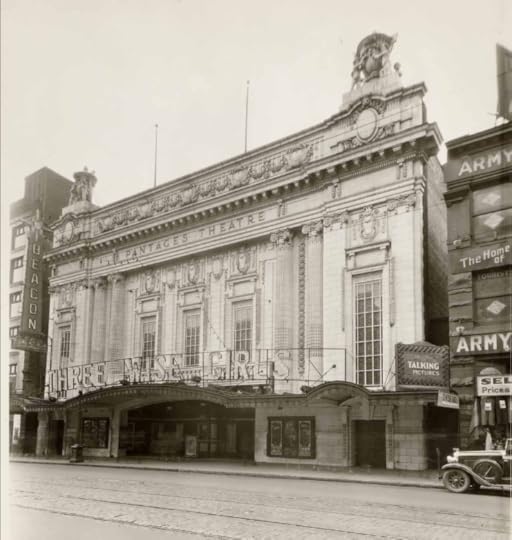

Beacon Theatre in 1932. Courtesy LF00218 JMABC

Beacon Theatre in 1932. Courtesy LF00218 JMABCThe Hobby Lobby ran until 1948, and would have been in its prime when these ads appeared on the front of Vancouver streetcars in 1944. The show was at the Beacon Theatre at 20 West Hastings Street, which according to Changing Vancouver, was replaced by a parking lot in 1967. It became non-market housing in 2000.

“Car 206 was a one-man car on the Powell Street line,” says Angus. “The white X on the front of the car denotes board at front and pay operator.”

Courtesy CVA 586-1874, 1944

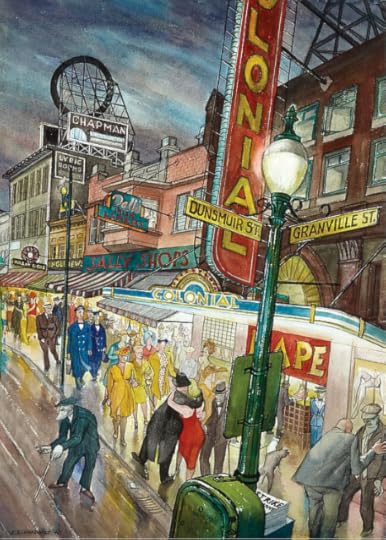

Courtesy CVA 586-1874, 1944Angus also found this painting of Granville Street painted by Jack Shadbolt in 1946 showing the other end of the block. “It sure captures the times. In both the photo and painting, note the blackout hoods on the tops of the streetlights,” says Angus. “By the time our family moved here in 1965, the Colonial Theatre was a second run movie house. It may well have been then.”

The Colonial Theatre was demolished in the early 1970s.

Jack Shadbolt painting, 1946

Jack Shadbolt painting, 1946Don Coltman also shot this photo of interior streetcar advertising in 1946. Car 195 had ads for McGavin’s Bread, a BC Electric concert featuring Allard deRidder (first conductor of the VSO), and the Bible.

Courtesy CVA 586-4586 1946

Courtesy CVA 586-4586 1946© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

April 5, 2019

Episode 02: The Murder Factory

Japantown, Vancouver in 1928 showing the CPR tracks where Watanabe’s body was discovered behind the American Can Company. Courtesy VPL 4269

Japantown, Vancouver in 1928 showing the CPR tracks where Watanabe’s body was discovered behind the American Can Company. Courtesy VPL 4269https://bloodsweatandfear.podbean.com/mf/play/pcqybd/Podcast_2_The_Murder_Factory_mixed.mp3

The murder of Naokichi Watanabe in 1931 exposed an insurance scam, the murder of up to 20 people, a Japanese hitman, and was eventually linked to an assassination ring operating out of a house on East Cordova Street, Vancouver.

Credits:

Intro and outro music: Duke Ellington’s St. Louie Toodle

Background track created by Nico Vettese www.wetalkofdreams.com

Intro and voice overs: Mark Dunn

“The Murder Factory” on East Cordova Street, Vancouver. Eve Lazarus photo, 2016

“The Murder Factory” on East Cordova Street, Vancouver. Eve Lazarus photo, 2016Source materials:

Blood, Sweat, and Fear: The Story of Inspector Vance, Vancouver’s First Forensic Investigator, by Eve Lazarus (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2017)

Nikkei National Museum

Stories of My People: A Japanese Canadian Journal, by Roy Ito (Nisei Veterans Association, 1994)

Various clippings from the Vancouver Sun, Province, Daily Colonist, Globe and Mail, Vancouver News Herald

The Inquest into the death of Naokichi Watanabe

The personal files of John F.C.B. Vance located in a grandson’s garage on Gabriola Island in July 2016.

And if you’d like to sponsor the podcast, my blog, or upcoming books, I’ve set up a page on Patreon.

March 30, 2019

Blood, Sweat, and Fear: A True Crime Podcast

I’ve been working on a true crime/history podcast for the last couple of months based on my book Blood, Sweat, and Fear: The Story of Inspector Vance, Vancouver’s First Forensic Investigator. My original thought was that it would be a great way to reuse some of the research I do for my books, and it is, but it’s become a bit of an obsession, and I plan to do a future series on Cold Case Vancouver, Murder by Milkshake, Sensational Vancouver, Sensational Victoria, and At Home with History where I can weave in many of the interviews that I conducted with family, friends, house owners and experts over the years.

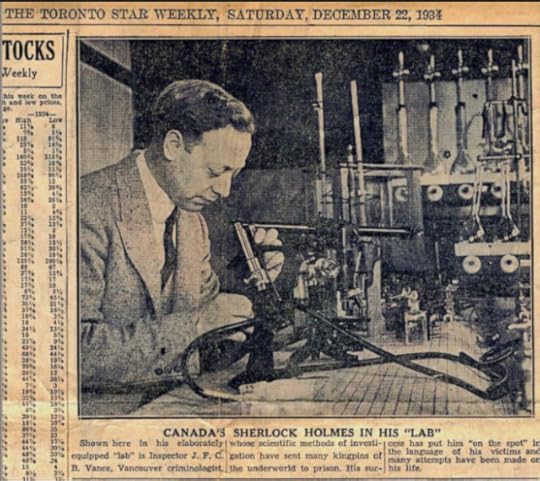

Vance in his lab, now the Vancouver Police Museum and Archives building on East Cordova Street.

Vance in his lab, now the Vancouver Police Museum and Archives building on East Cordova Street.The learning curve is huge and my podcasts are a work in progress. I’m learning to write for the ear, and I’ve spent dozens of hours watching YouTube videos to teach myself Audacity, the free audio software program, so I can produce the show myself.

There will be 12 episodes in this first series, published every second Friday. Each one follows a major crime that Vance helped to solve using cutting-edge forensics during his 42-year-career.

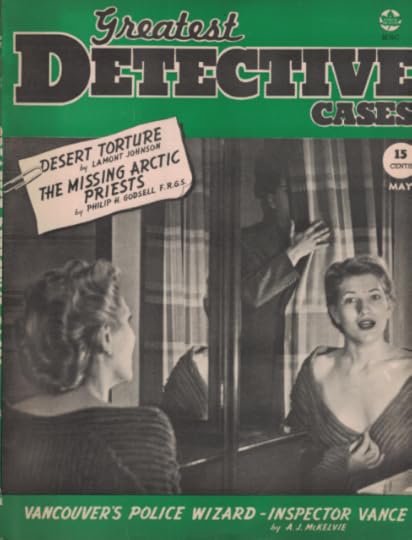

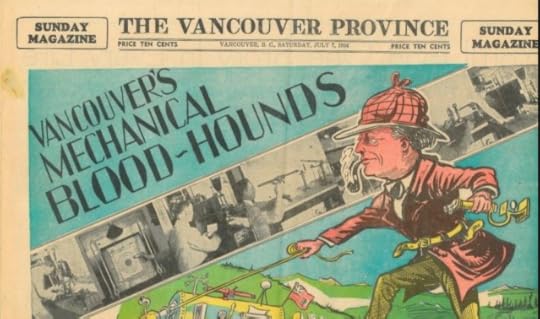

Vance’s exploits frequently appeared in “true crime” detective magazines

Vance’s exploits frequently appeared in “true crime” detective magazinesI’ve tried to show how the social forces of the time impacted the crime. For instance, Vance’s work took him all around the province and up into the Yukon in what is one of the most interesting periods in British Columbia’s history. Vance started work for the city of Vancouver in 1907, four months before anti-Asian riots swept through the city. He worked through the crime-ridden Depression and two world wars, and he was employed by two of the most corrupt police chiefs in the history of the Vancouver Police Department.

Vance’s work turned him into a celebrity, and he became known as the Sherlock Holmes of Canada in the press.

Vance’s work turned him into a celebrity, and he became known as the Sherlock Holmes of Canada in the press.Much of the information came from the Vancouver Sun, Province, Vancouver News Herald, and the World. Most of the quotes are from Coroner’s Inquests, but the bulk of the information (including the clippings shown in the post) came from the personal files of Inspector John F.C.B. Vance that were discovered in a garage on Gabriola Island by one of Vance’s grandchildren when I was doing the research for the book in 2016. The archival material is now with the Vancouver Police Museum and Archives, and some is currently on display at the Nanaimo Museum.

The first episode: The Mysterious Disappearance of Clara Millard, takes place in Vancouver in 1914.

Ways to Listen:

My website

iTunes

Podbean

Stitcher

Please let me know what you think.

If you’d like to sponsor the podcast, my blog, or upcoming books, I’ve set up a page on Patreon.

March 23, 2019

Paul Yee’s Vancouver Archives

About six years ago, I was doing some research for my book Sensational Vancouver and took a tour of Strathcona with James Johnstone. I was excited to meet Paul Yee, a historian who now lives in Toronto, and has written several brilliant books which include Salt Water City, Tales from Gold Mountain, and most recently, A Superior Man (see Paul’s website for a full list).

Paul Yee outside his childhood house at 540 Heatley Street in 2013. Eve Lazarus photo

Paul Yee outside his childhood house at 540 Heatley Street in 2013. Eve Lazarus photoPaul told me that he lived in three different houses in Strathcona between 1960 and 1974.

“I was an orphan,” he said. “When whole blocks of houses around me were demolished, I felt like I was being shoved onto a stage for the world to see all the shame that came from living in a slum. Even as a child, I knew Vancouver had better neighbourhoods. I was embarrassed to tell people my address, show others my library card.”

Paul’s first address was 350 ½ East Pender Street. The house is long gone, and the ½ refers to a smaller house that stood at the rear of the main residence, he says. The family left in 1968 to live above the Yee’s family store at 263 East Pender, and in 1971 they moved to 540 Heatley Street. Later, the Yee’s moved east into the Grandview Woodlands Neighbourhood.

200 Block East Hastings in 1986, from the Paul Yee Fonds, Courtesy CVA 2008-010.0523

200 Block East Hastings in 1986, from the Paul Yee Fonds, Courtesy CVA 2008-010.0523Paul, was amazed at how much Strathcona had changed “When I walk through Strathcona now, what really hits me is how green and lush it is. The place is now respectable, unlike when I lived there,” he said.

This week, Vancouver Archives announced that thanks to funding from the Friends of the Vancouver City Archives, they have now digitized 3,700 photos that the Yee family donated in 2014. Many are Paul’s own photos, and there are also oral interviews online from the ‘70s and ‘80s with Chinese Canadian seniors and community members. You can read more about it on their great blog AuthentiCity.

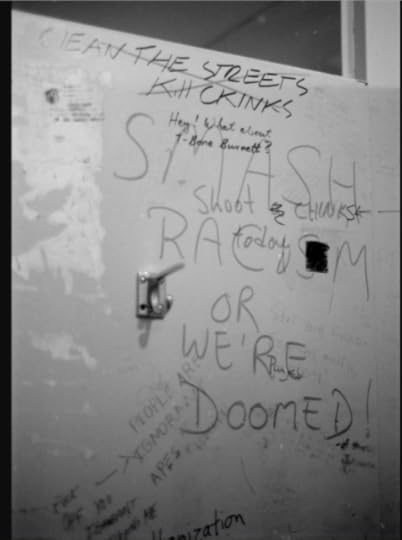

A racist poster from UBC in 1987. Courtesy Paul Yee Fonds and CVA 2008-010.1762

A racist poster from UBC in 1987. Courtesy Paul Yee Fonds and CVA 2008-010.1762Many of the historical photos that you see in our books and on the many Facebook pages that are about “old” Vancouver, including my own Every Place has a Story, come from Vancouver Archives, and it’s all free of charge. It’s an incredible resource, and if you become a member of the Friends of the Vancouver Archives, your money goes to digitizing more of these records.

Arrival of Chinese Statesman Li Hung-Zhang at the CPR dock at the foot of Howe Street in 1896. Courtesy Paul Yee Fonds and CVA 2008-010.4121

Arrival of Chinese Statesman Li Hung-Zhang at the CPR dock at the foot of Howe Street in 1896. Courtesy Paul Yee Fonds and CVA 2008-010.4121Personally, I’m looking forward to the AGM on March 31 with guest speaker Ron Dutton. Ron started the BC Gay and Lesbian Archives in 1976, and he recently donated over 750,000 posters, sound recordings, photographs, magazines and clippings to the Archives.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

March 21, 2019

Episode 01: The Mysterious disappearance of Clara Millard

The first time Inspector Vance was called to work on a police investigation was for a missing persons case in 1914. Charles and Clara Millard lived in Vancouver’s West End with their 16-year-old Chinese houseboy, Jack Kong. Charles who was an executive with the Canadian Pacific Railway, was away on business, and when he returned home his wife Clara was gone. Had she disappeared without telling anyone? Had she been kidnapped? Was she murdered?

The stories for this first series are from my book Blood, Sweat, and Fear: The Story of Inspector Vance (Eve Lazarus, Arsenal Pulp Press, 2017). Vance was one of the first forensic scientists in North America, and during his 42-year-career, helped to solve some of the most sensational murders of the 20th Century. Each episode focuses on one of those cases.

Credits:

Intro and outro music: Duke Ellington’s St. Louie Toodle

Background track created by Nico Vettese www.wetalkofdreams.com

Intro and voice overs: Mark Dunn

Thank you to my first listeners for their feedback and support:

Mark Dunn

Tom Carter

Bill Amos

Amy Erb

Primary source material: Vancouver Sun, Province, Vancouver News Herald, The World; Inquest into the death of Clara Millard; and the personal files of Inspector John F.C.B. Vance.

And if you’d like to sponsor the podcast, my blog, or upcoming books, I’ve set up a page on Patreon.

The Mysterious disappearance of Clara Millard

The first time Inspector Vance was called to work on a police investigation was for a missing persons case in 1914. Charles and Clara Millard lived in Vancouver’s West End with their 16-year-old Chinese houseboy, Jack Kong. Charles who was an executive with the Canadian Pacific Railway, was away on business, and when he returned home his wife Clara was gone. Had she disappeared without telling anyone? Had she been kidnapped? Was she murdered?

March 16, 2019

Iaci’s Casa Capri

I’m currently experiencing technical problems with the blog. If you would like to subscribe to notifications, please send me an email at info@evelazarus.com and I’ll add you to the list.

Rick Iaci was driving down Seymour Street one day when he was horrified to see dozens of framed photographs being thrown into a dumpster outside #1022—the house that was a family restaurant for more than 50 years. He stopped and put as many as he could into his car, and in that moment, saved a piece of Vancouver’s history.

Iaci’s is the house on the far left in this 1981 photo of the 1000 block Seymour Street. Courtesy CVA 779-E06.35

Iaci’s is the house on the far left in this 1981 photo of the 1000 block Seymour Street. Courtesy CVA 779-E06.35Frank and Eva Iaci, cousins to the Filippone’s who ran the Penthouse across the street, raised their six children in the home, and turned it into a bootlegging joint during the Depression. Eva started making plates of pasta so her customers could have something to eat while they drank. The menu was simple—spaghetti with meatballs, T-bone steak, ravioli, chicken cacciatore. A card clipped to the menu read “Dear God. Please save us from the Italian man that expects us to cook as well as his mother. How in the hell can we when his wife can’t?”

Photo of Eva and Frank Iaci (Junior) saved from the dumpster. Courtesy Rick Iaci and Ashley Waller

Photo of Eva and Frank Iaci (Junior) saved from the dumpster. Courtesy Rick Iaci and Ashley WallerHer food was so popular that the house became known as Casa Capri. The family called it #1022, locals just called it Iaci’s.

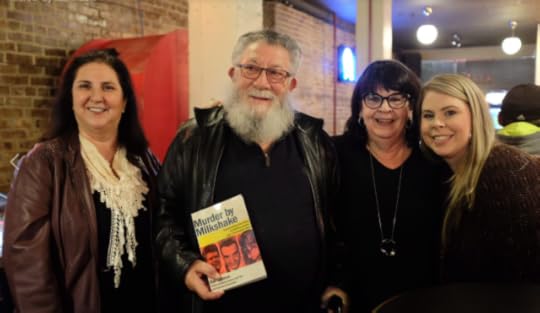

Iaci’s was gone by the time I arrived in Vancouver, and I first heard about it when I was researching Murder by Milkshake. Before Rene Castellani murdered his wife, he, Esther and their daughter Jeannine, would spend a few nights a week in the restaurant, helping out in the kitchen or just hanging out.

Mary and Rick Iaci, Jeannine and Ashley at the book launch for Murder by Milkshake, November 2018. Scott Alexander photo

Mary and Rick Iaci, Jeannine and Ashley at the book launch for Murder by Milkshake, November 2018. Scott Alexander photo“We were at Iaci’s all the time. I don’t even know how many times a week,” says Jeannine. “We never sat in the restaurant. We were always in the kitchen where they were cooking.” When it got late, Jeannine was put to bed in Eva’s downstairs suite which also harboured the illegal booze. “When the police came in, they never checked because they saw me there, sound asleep,” she says.

Customers could park for free in the tiny lot in the back, go through the basement, climb up the stairs to the back porch and then enter through the kitchen. Someone would be there to greet them, take their coats, and find them a seat in one of the three small front rooms, where they could check out the Iaci’s old wedding photos or framed covers of Life and Look magazines.

Courtesy Rick Iaci and Ashley Waller

Courtesy Rick Iaci and Ashley WallerRick remembers the bathroom being covered in stock certificates. One night a broker was using the facilities when he noticed that one of the old stocks was worth money. “They took down half the wall to get it,” says Rick. The magazine covers went up after that.

Casa Capri was the place to go for anyone looking for a good meal and a drink late at night. After performing at the Palomar or the Cave stars such as Dean Martin, Red Skelton, Tom Jones, Louis Armstrong, and Sonny and Cher would head to Iaci’s with an autographed photo made out to one of the family members—usually one of Eva’s daughters—Koko, Teenie and Toots.

Signed to Tootsie and Teenie from the Mills Brothers. Courtesy Rick Iaci and Ashley Waller

Signed to Tootsie and Teenie from the Mills Brothers. Courtesy Rick Iaci and Ashley WallerRick is now the guardian for the old photos. He spent every Saturday night for more than ten years at Casa Capri, sometimes as the bartender when the regular guy didn’t turn up. Once he asked Eva why they were using Tang in the Vodka and orange juice. She told him: “If it’s good enough for the astronauts, it’s good enough for our customers.”

In 2005, Eva and Frank Iaci were posthumously inducted into the BC Restaurant Hall of Fame.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.