Eve Lazarus's Blog: Every Place has a Story, page 37

November 25, 2017

Saving History: Crime Maps, Surveillance Albums and Mugshot Books

If you enjoy a good murder story, love heritage buildings, or just want to see what a morgue looks like, then you need to make your way down to the Vancouver Police Museum.

For those of us who write about crime, the museum is ground zero when it comes to information, because apart from the static displays there is a vast archive and amazing staff to help you navigate through it.

When the police station at 312 Main Street closed in 2010, the Museum inherited a bunch of really cool stuff. And, when I dropped by last week, Rozz and Elizabeth were kind enough to share a few of their finds.

Most fascinating were the crime maps dated from the 1940s to the mid ’70s.

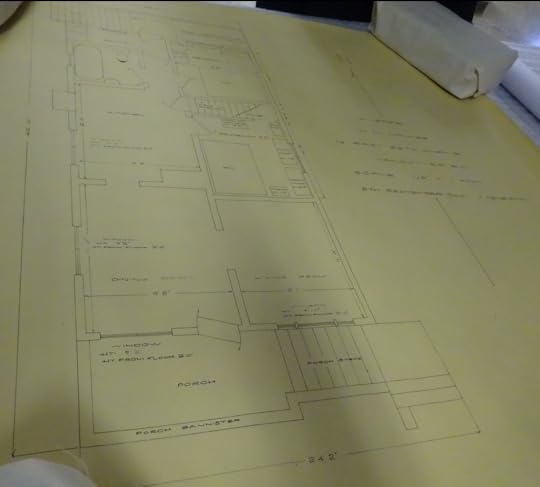

“They are floor plans that were hand drawn by two officers and signed,” explained Elizabeth.

Some of the maps were for murder scenes, others for robberies.

Elizabeth carefully unrolled one of the maps. It was a very detailed drawing of the interior of a house and dated September 8, 1960. The address was 19 East 26th Avenue.

I couldn’t wait to get home.

Street directories showed that the house’s owner was a Mrs. Mina May Holmes. My next step was vital statistics. It turned out that 75-year-old Holmes came to an untimely end when she was beaten to death by “persons unknown.”

A date with the Vancouver Public Library’s microfilm confirmed that she was killed by a brain hemorrhage and a blow so severe that it broke her jaw and bashed in her skull. Police found her lying in a bed splattered with orange pop. They concluded that the pop bottle was the murder weapon and the prime suspect was Sammy Semple, 51, a former vaudeville dancer who had moved into her home the day before.

A check on Google maps shows that her house is still there.

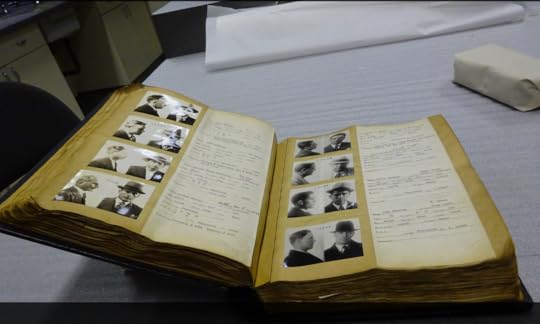

Unfortunately, much of the information in the archives can’t be publicized because it contravenes Freedom of Information laws. One of these gems is an album (pictured at the top) packed full of surveillance photos showing women leaving the Penthouse nightclub on Seymour Street in the mid-1970s.

Elizabeth was able to identify the building from the distinctive exterior of the Penthouse door.

The back of the book has pages of mugshots indicating that surveillance paid off and the cops were able to prosecuted Angela, Kitty and dozens of other Penthouse “staffers.”

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

November 18, 2017

What was here before? The Kingsgate Mall

The thing about the Kingsgate Mall at Broadway and Kingsway is you either love it or you hate it. It’s weird or wonderful, strange or quaint, creepy or quirky, but it rarely goes unnoticed.

The cupola (which is a replica of the one that used to top King Edward School before the fire) has turned the mall into a bit of a landmark, but I can’t imagine calling it a destination by any stretch of the imagination. Aside from a dental surgery and a credit union, one of the only stores not found in most other shopping malls is the Lolli Pretty Clothing Company that has 74 Facebook Likes and the fabulous tagline “Your Candy Store of Fashion.”

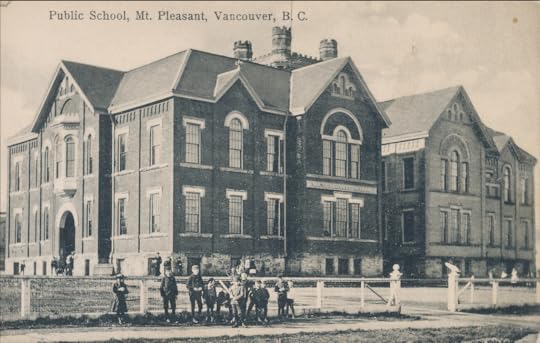

Postcard ca.1906: https://www.flickr.com/photos/45379817@N08/9485117002

Postcard ca.1906: https://www.flickr.com/photos/45379817@N08/9485117002When the mall was built in 1974, it took out the Mount Pleasant Elementary School, an 80-year-old solid brick building built in 1892, that was originally known as the False Creek School.

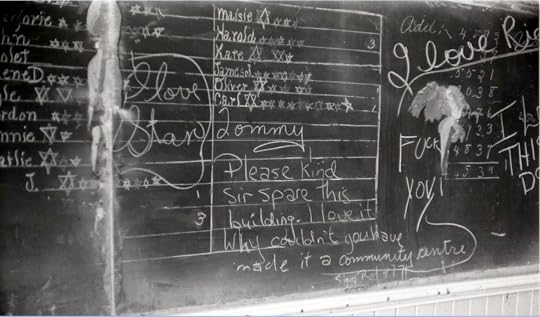

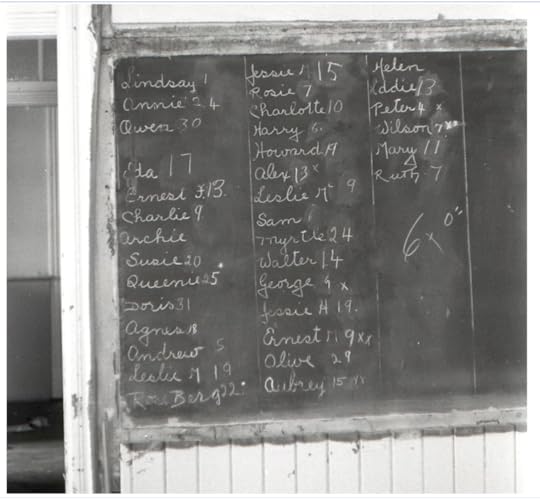

Angus McIntyre shot this photo of the inside of a classroom in June 1972. “Someone did not agree with the plan to keep the school,” he says.

Angus McIntyre shot this photo of the inside of a classroom in June 1972. “Someone did not agree with the plan to keep the school,” he says. Angus McIntyre photo, June 1972

Angus McIntyre photo, June 1972What somehow escaped the bulldozer, was a ca.1907 buried house at 350 East 10th Avenue, directly behind the mall and adjoining a Telus parking lot.

When the Mount Pleasant school was demolished in 1972 the kids moved into a new school at 2300 Guelph, and which is still very much in operation.

These houses in the 2300-block Guelph Street were demolished to make way for the new Mount Pleasant school. Courtesy Vancouver Archives, 1966

These houses in the 2300-block Guelph Street were demolished to make way for the new Mount Pleasant school. Courtesy Vancouver Archives, 1966Oddly, the land underneath the Kingsgate Mall is owned by the Vancouver School Board and has been since the late 1880s. The VSB in turn leases the land to Beedie Development Corp for $750,000 a year, and they operate the mall. No surprise that Beedie would like to buy the mall, pull it down and redevelop it.

Perhaps the pinned tweet on the unofficial twitter account for the Kingsgate Mall says it all: “STILL NOT A CONDO.”

Courtesy Northern BC Archives, June 1971

Courtesy Northern BC Archives, June 1971© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

November 11, 2017

Vancouver’s Parking Meters turn 71

On November 12 it will be 71 years since the first parking meters hit Vancouver. The fee was five cents an hour.

For the first 30 years, police had responsibility for checking the meters, and I bet that assignment was the equivalent of standing in the corner with a dunce cap. Parking meter enforcement was transferred to a civilian force in 1976, and the rates ranged between 10 and 40 cents an hour.

Vancouver’s first parking meter unveiled November 12, 1946, showing Hotel Devonshire and Georgia Hotel in the background. Courtesy CVA 586-4816

Vancouver’s first parking meter unveiled November 12, 1946, showing Hotel Devonshire and Georgia Hotel in the background. Courtesy CVA 586-4816Branca Verde was one of the early “meter maids” when she was hired by the City of Vancouver in 1982. There were 12 in total, she told a Vancouver Sun reporter on her retirement last year, and yes, all were women.

The checkers were given some scratchy dark blue fabric and told to make themselves a skirt, long shorts or pants. Then they were handed old jackets from the engineering department-it doesn’t say whether they were new or used.

Meter checker Branca Verde in 1982. Courtesy Vancouver Sun

Meter checker Branca Verde in 1982. Courtesy Vancouver SunTo outsmart over-parkers who rubbed off the chalk used to mark the tire, the checkers would place a smartie on top of the tire under the wheel well, said Verde.

Today, there are around 10,000 parking meters on Vancouver streets ratcheting up anywhere from $1 to $6 an hour and filling city coffers with $50 million every year and another $20 million in parking tickets.

Gastown parking meters ca.1972. Courtesy CVA 691834

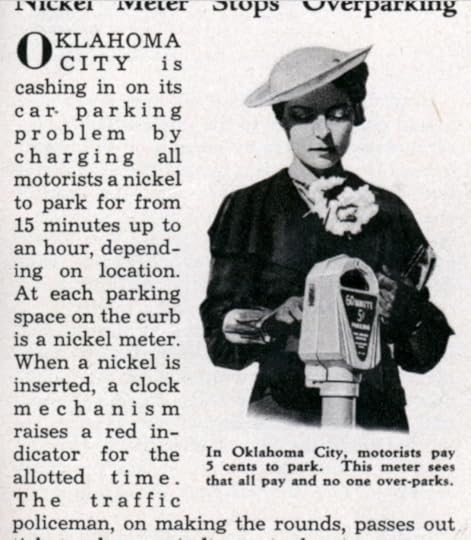

Gastown parking meters ca.1972. Courtesy CVA 691834Where was the world’s first parking meter you ask? Well according to Parking-net it was in Oklahoma City on July 16, 1935 and called Park-O-Meter No. 1.

Sources:

City of Vancouver Archives – http://searcharchives.vancouver.ca/

Chuck Davis’s History of Metropolitan Vancouver

Vancouver Sun, October, 2016

CBC, November, 2016

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

November 4, 2017

Our Missing Heritage: King Edward High School

On June 19, 1973, a three-alarm fire broke out at Vancouver City College at West 12th and Oak Street. Over a thousand students were in class and safely evacuated, but it was too late for the school, destroyed by faulty wiring in the attic.

“My dad, Chief Bill Frederick graduated from King Ed. He sadly told the story of how his crew fought that blaze with all their might,” Patty Frederick, June 2017. Photo courtesy Vancouver Fire Fighters Historical Society.

“My dad, Chief Bill Frederick graduated from King Ed. He sadly told the story of how his crew fought that blaze with all their might,” Patty Frederick, June 2017. Photo courtesy Vancouver Fire Fighters Historical Society.William T. Whiteway, the same architect who designed the Sun Tower and the Storey and Campbell Warehouse on Beatty Street, and Lord Roberts Elementary in the West End, designed the school in the Neoclassical style and topped it off with a central cupola. It was the first secondary school south of False Creek, and appropriately named Vancouver High School. Classes started in 1905, the school was renamed King Edward in 1910, and another section was added in 1912.

Courtesy Andrea Nicholson

Courtesy Andrea NicholsonThe King Ed alumni includes an impressive list of Vancouver luminaries. There is Cecil Green the philanthropist who attended UBC when classes operated out of the 12th and Oak Street building. Broadcasters include Jack Cullen and Red Robinson. While other notables to pass through the school’s corridors are Dal Grauer, Nathan Nemetz, Grace McCarthy, Yvonne De Carlo and Jack Wasserman.

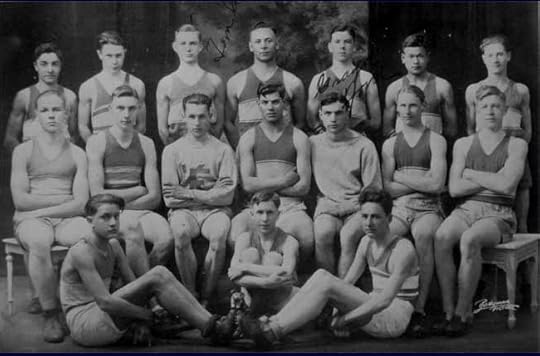

There’s a skinny, very young Percy Williams in a picture of the King Ed high school track team of 1926. Percy had taken up running two years before because it was part of the sports program. Two years later he brought home two gold medals from the Olympics and became a local hero.

Percy Williams in the middle row, third from left. Courtesy Andrea Nicholson.

Percy Williams in the middle row, third from left. Courtesy Andrea Nicholson.In 1962 King Ed became an adult education centre and the kids transitioned to Eric Hamber, says Andrea Nicholson, alumni coordinator.

Andrea’s mum Elizabeth Lowe (MacLaine) taught at the school and later became department head for Business Education. She was supposed to teach night school on the day the school burned down.

“I remember as a child going up into the turret, and I remember when they pulled that school apart the dividers for the bathroom stalls were solid marble,” says Andrea, who could see the flames from the grounds of Cecil Rhodes Elementary at 14th and Spruce.

Courtesy Vancouver Archives Sch P43, 1925

Courtesy Vancouver Archives Sch P43, 1925Vancouver Community College took over the school in 1965 and five years later the building sold to Vancouver General Hospital, although it remained an educational institute until the fire.

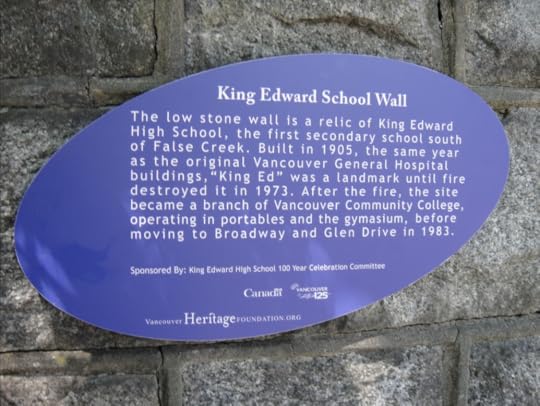

Now, all that’s left of the school building is a stained-glass window installed in VCC’s Broadway campus, a stone wall, a plaque, and a large photograph of the original school in the VGH’s Diamond building which replaced it.

“The architects were very good to include a circle of yellow tile on the main floor which outlines the original King Ed high school,” says Andrea.

The wall received a Places that Matter plaque in 2012. Former King Ed teacher, and vice-president Annie B. Jamieson (1907-1927) recently had an elementary school named after her.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

October 28, 2017

The Ghosts of the Fireside Grill

The Fireside Grill is situated on a ley line that runs down West Saanich Road, through Wilkinson Road, toward the Four Mile House—a reputably haunted inn—to the Portage Inlet and Esquimalt Harbour. This story is an excerpt from Sensational Victoria.

Tim Petropoulos, co-owner of the Fireside Grill since 2000, is a self-described skeptic when it comes to ghosts, but even he can’t discount all the sightings and odd things that have happened over the years and the first-hand accounts from his staff.

The Thatch/Maltwood House, 1979. Courtesy Saanich Archives

The Thatch/Maltwood House, 1979. Courtesy Saanich Archives“I spend so much time here at night and during the day that it feels like somebody is with you all the time,” he says. “I just shrug it off, but I know some of my staff are believers.”

Architect Hubert Savage designed the Tudor Revival house as an English-style tea and dance room in 1939, strategically built on a hilltop between Butchart Gardens and the new Airport.

War-time rationing and gas restrictions quickly killed off the Royal Oak Inn and the business was sold to John Maltwood from England, who sought a fitting home for his artist wife and their large collection of antiques.

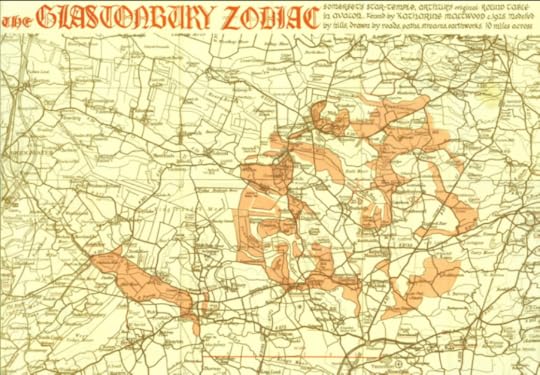

Katharine believed in the occult and wrote a book about her discovery of the Glastonbury Zodiac in 1927. This Zodiac, she believed, plays an important role in occult theories and is essentially the signs of the zodiac formed by features in the landscape such as waterways, roads, streams, walls and pathways.

The Maltwoods added a two-storey studio on the north side for Katharine which connected to the main building by a passageway from the minstrel’s gallery.

The Maltwoods renamed the house “The Thatch.”

Katharine died in 1961 and rumour has it that she was buried on the property. John left the house and art to UVic in 1964, and it operated as the Maltwood Museum until the university sold the property to the District of Saanich in 1980.

Staff say that the inn is haunted by Katharine’s ghost and that of a little pug dog. One staff member reported several sightings of Katharine as a white silhouette with a little dog by her side.

Having a ghost isn’t a bad thing for a restaurant, especially one that’s not mischievous or malevolent. But there have been incidents.

When the house was owned by the University of Victoria, caretakers would be called about alarms going off and things going missing.

“I haven’t found anything missing or changed or moved,” says Tim. “But it’s a restaurant and it’s being used all the time. I probably wouldn’t notice if the cutlery was upside down.”

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

October 21, 2017

Aborted Plans: All Seasons Park

When I think of all the demolition and destruction that we’ve put Vancouver through over the last century, it amazes me that we still have Stanley Park. It’s not from lack of trying though, developers have been trying to chip away at it for years.

A peace sign garden at All Seasons Park, the proposed site of a Four Seasons Hotel near the entrance to Stanley Park, on May 30, 1971. Courtesy Kate Bird.

A peace sign garden at All Seasons Park, the proposed site of a Four Seasons Hotel near the entrance to Stanley Park, on May 30, 1971. Courtesy Kate Bird.I first heard of the All Seasons Park when I was flipping through Kate Bird’s new release: City on Edge. The photo, taken by Province photographer Gordon Sedawie over 46 years ago, shows a peace sign garden. As the caption explains, the site was occupied by people opposed to the development of a Four Seasons hotel and condo complex at the Coal Harbour entrance to Stanley Park.

Coal Harbour and the entrance to Stanley Park ca.1960s. CVA 1435-657

Coal Harbour and the entrance to Stanley Park ca.1960s. CVA 1435-657Kate sent me the photo and some articles explaining the context.

There were three attempts to turn the 14-acre entrance to Stanley Park into a developer’s paradise. The first was by a New York developer in the early ‘60s.

Selwyn Pullan, who died last month, photographed the first proposed model in 1963

Selwyn Pullan, who died last month, photographed the first proposed model in 1963The second was by a local outfit called Harbour Park Developments that bought the land in 1964 and proposed a $55 million development with 15 towers ranging between 15 and 31-storeys in height.

Aerial photo showing the proposed development. Courtesy Vancouver Sun.

Aerial photo showing the proposed development. Courtesy Vancouver Sun.The third, and most promising for Vancouver City Council at least, was a plan by the Four Seasons Hotel chain to build a 14-storey hotel, three 30-storey condos towers, and a bunch of townhouses.

Mayor Tom Campbell riding the wrecking ball that would take out the Lyric Theatre in 1969

Mayor Tom Campbell riding the wrecking ball that would take out the Lyric Theatre in 1969This was the era when Mayor Tom Campbell (1967-72) and the NPA were replacing swaths of heritage buildings with the Pacific Centre and Vancouver Centre, pushing for freeways that would knock out large parts of the city, and lobbying for Project 200, that if it had gone ahead, would have destroyed most of Gastown.

On May 30, 1971 a few dozen hippies took over the site and set up camp (coincidentally, around the same time that the District of North Vancouver was destroying many of the squatter shacks at Maplewood). The Stanley Park protesters planted maple trees and vegetables, dug a pond, and called it All Seasons Park.

They stayed for nearly a year.

Campbell issued a plebiscite where only property owners could vote. It succeeded when less than 60% voted to reject the Four Season’s plan. But while our city council was gung-ho, the plan fell apart in 1972 when the Federal government refused to hand over a crucial piece of land.

Five years later the land was annexed to Stanley Park and oddly renamed Devonian Harbour Park.

Stanley Park in a parallel universe

Stanley Park in a parallel universeSources:

City on Edge: A rebellious century of Vancouver protests, riots, and strikes

The Chuck Davis History of Metropolitan Vancouver

“This week in history” – Vancouver Sun, May 26, 2017

Yippies in Love (2011)

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

October 14, 2017

The Tragic Death of CPR Constable Thomas Sharpe

A couple of months ago Murray Maisey sent me a clipping from the World regarding the death of Thomas Sharpe. Because Constable Sharpe worked for the CPR, I forwarded the clipping to Graham Walker, who did such an amazing job uncovering the story of Charles Painter last year. Graham, now a constable with the Saanich Police Department and a member of the Saanich Police Historical Society, hit the BC Archives, and this story is the result of his investigation.

By Graham Walker

Vancouver Daily World, March 19, 1920. Courtesy Murray Maisey

Vancouver Daily World, March 19, 1920. Courtesy Murray MaiseyOn March 18, 1920, Charles Cook, hotel keeper at the Clifton Rooms on Granville Street, received a call from the Canadian Pacific Railway’s Waterfront station, looking for Thomas Sharpe, a guest at the hotel.

Cook headed upstairs to Room 68 on the fourth floor and knocked and knocked, but there was no answer. Because he worked nights, Cook knew Sharpe was a hard man to wake, so he decided to let him sleep.

1100 block Granville Street, 1928. Courtesy Vancouver Archives

1100 block Granville Street, 1928. Courtesy Vancouver ArchivesAround 7:00 p.m. Cook went back upstairs and knocked again. When he tried his pass key he found the door had been locked from the inside. Cook went back downstairs to get his tools and saw Mr. Francey, a ship caulker, in the sitting room. The two men removed the bolt and opened the door. They found Constable Sharpe in a chair, a bullet wound to his head. Cook phoned police.

Vancouver Police Constable William Thompson was the first to respond. He saw that Sharpe still had a revolver in hand, his head was lying back on the stove, and there was a large pool of blood on the floor. It appeared to be a suicide, but Thompson had the presence of mind to fully examine the room.

Clifton Hotel, 1125 Granville Street, 1978. Courtesy Vancouver Archives

Clifton Hotel, 1125 Granville Street, 1978. Courtesy Vancouver ArchivesAn ammunition box rested on a table in front of Sharpe. One cartridge was missing. Thompson examined the revolver and found one empty shell in the chamber. Except for the body, the room looked in order. The constable noted that the window was open, but the location of the body and the bullet hole led him to believe the shot could not have come from outside, and no one could have left by the window.

Constable Thompson’s testimony at the Inquest

Constable Thompson’s testimony at the InquestMs. Cole, the occupant of the room next to Sharpe’s, told Thompson that she heard a noise around 9 a.m. and thought it was a heavy object that had dropped.

Coroner Thomas Jeffs held an inquisition two days later at the City morgue.

Witnesses told him that 49-year-old Sharpe had worked for the CPR for eight years, and lived at the hotel for the past six.

Sharpe had recently transferred to the night shift because he liked the “quiet,” and had worked the 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. shift the night before his death. He arrived home around 7:00 a.m. and changed into regular clothes.

Sharpe had recently transferred to the night shift because he liked the “quiet,” and had worked the 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. shift the night before his death. He arrived home around 7:00 a.m. and changed into regular clothes.

Sergeant Charles Loscombe, a friend and coworker, described Sharpe as an honest and hard-working man, who was also reserved and introverted. Loscombe confirmed that the .38 calibre revolver found at the scene was not a police weapon. Sharpe’s duty revolver, a .32, was still in his locker at the station. Loscombe said that Sharpe was on a strict diet because he suffered from chronic indigestion. The sergeant also suggested that there may have been some financial troubles having to do with Sharpe’s investments in real estate in North Vancouver and Point Grey, as well as his shares in the CPR.

The Clifton Hotel, 1125 Granville Street, 2017

The Clifton Hotel, 1125 Granville Street, 2017Thomas Pearson, a Reeve in Point Grey testified that he had known Sharpe since they were boys. He said that Sharpe’s father had recently passed away, and Sharpe had talked about taking a leave of absence to help out on the family farm in Quebec.

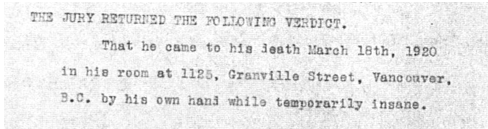

Pearson believed that the shooting was suicide brought on by temporary insanity. The jury agreed.

Sharpe was buried at Sainte-Julienne, Quebec.

Mental health awareness for emergency services workers has been in the spotlight due to many high-profile suicides by law enforcement officers and rescue workers. It’s likely that Sharpe’s work as a railway constable involved significant stress, duties involved, and still involve, responding to tragedies along the rail line.

For workers exposed to traumatic stress, problems can accumulate over time and end up with very serious consequences. Many agencies have taken great steps in recent years to educate their employees on mental health awareness and have provided instructional sessions for those who wish to be peer counsellors. But despite many improvements, tragedies like these still occur across the country.

Mental health resources:

paramedicnatsmentalhealthjourney.com

October 7, 2017

City on Edge

On June 14, 1994, I started my shift in Surrey. My assignment for the Vancouver Sun was to wait until the end of the Stanley Cup final between the New York Rangers and the Canucks, catch the SkyTrain downtown, and report on what happened.

Stanley Cup riot June 14, 1994. Stuart Davis/Vancouver Sun

I crammed into a car with dozens of others who were openly drinking and yelling. The mood was intense. When we got out at Granville, the crowd flowed down the street, breaking the windows of the Bay and looting anything they could carry, including headless mannequins. Everyone drifted towards the epicenter at Robson and Burrard. Later, the riot police circled the crowd firing canisters of tear gas, but neglected to leave an escape route. I watched Anne Drennan, the VPD’s media officer tell national television that everything was under control, even as her mascara streamed down her face. It was a colossal fucking mess.

A march on February 14, 1992 for missing and murdered women in the Downtown Eastside was sparked by the murder of Cheryl Ann Joe. The march became an annual Valentine’s Day event. Denise Howard/Vancouver Sun

A march on February 14, 1992 for missing and murdered women in the Downtown Eastside was sparked by the murder of Cheryl Ann Joe. The march became an annual Valentine’s Day event. Denise Howard/Vancouver SunKate Bird’s latest book City on Edge: A rebellious century of Vancouver protests, riots, and strikes brought all that back to me with one powerful newspaper photo. And, I would be surprised if anyone who has lived in this city for any length of time doesn’t feel a similar connection to something in this book.

For Kate, who moved to Vancouver from Montreal in the ‘70s, and worked as the Vancouver Sun and Province’s librarian for 25 years, it was the peace marches, solidarity and the environment.

Property owners and neighbours protest May 19, 1949 on the site of the Fraserview housing development after a bulldozer destroyed a fifteen-tree cherry orchard. The government expropriated the property, but several holdouts objected to the land price being offered and the method used to divide lots. Vancouver Sun

Property owners and neighbours protest May 19, 1949 on the site of the Fraserview housing development after a bulldozer destroyed a fifteen-tree cherry orchard. The government expropriated the property, but several holdouts objected to the land price being offered and the method used to divide lots. Vancouver SunSelecting photos for the book was a combination of events that Kate had researched in the past and great photos that needed more research.

“When I looked at all these images that I collected, I found some themes running through them,” she says. “Labour of course and anti-government, but also indigenous protests, social justice issues, the environment and hooliganism and riots.”

Residents and sympathizers picket along the 2500-block East Pender to protest land assembly housing development. Peter Hulbert/Province,September 29, 1975.

Residents and sympathizers picket along the 2500-block East Pender to protest land assembly housing development. Peter Hulbert/Province,September 29, 1975.

You might be surprised to learn that housing is a perpetual Vancouver problem. Themes such as affordable housing, evictions for luxury condos, homelessness, and land assembly run through almost every decade of the book.

But some things are better.

“Some people think we are still protesting over the same thing, but of course lots of things have changed. Things have improved for women, for LGBTQ and for labour.”

Residents protested the demolition of a Kerrisdale rental apartment on August 14, 1989, one of three scheduled for demolition that week and the sixth apartment razed in two months to make way for luxury condos. Ralph Bower/Vancouver Sun

Residents protested the demolition of a Kerrisdale rental apartment on August 14, 1989, one of three scheduled for demolition that week and the sixth apartment razed in two months to make way for luxury condos. Ralph Bower/Vancouver SunVancouver, though does seem to have more of its share of protests, says Kate.

“Early in the 1900s, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) came up and got a real foothold here in the resource industries. In the ‘60s there were draft dodgers from the US and a lot of them stayed and got jobs at SFU and UBC as professors and got involved in politics. There was way more influence from the west coast than from eastern Canada.”

Kids picket on Columbia Street in New Westminster against eight-cent chocolate bars after a two-cent price increase. Vancouver Sun, April 30, 1947.

Kids picket on Columbia Street in New Westminster against eight-cent chocolate bars after a two-cent price increase. Vancouver Sun, April 30, 1947.Kate, who is the author of the bestselling Vancouver in the Seventies, says she’s already working on her next book. This time she’ll be looking at Vancouver’s sports history.

The Museum of Vancouver has just opened a fabulous exhibition based on Kate’s book including wall-size photos. It will run until February 18.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

September 30, 2017

Our missing heritage: the forgotten buildings of Bruce Price (1845-1903)

In the 1970s, the Scotia Tower and the hideous Vancouver Centre—currently home to London Drugs—obliterated a block of beautiful heritage buildings at Granville and Georgia Streets. The development took out the Strand Theatre (built in 1920), and the iconic Birks building, an 11-storey Edwardian where generations of Vancouverites met at the clock.

The Birks building and the second and third Hotel Vancouver in 1946. Courtesy Vancouver Archives 586-4615

The Birks building and the second and third Hotel Vancouver in 1946. Courtesy Vancouver Archives 586-4615I was surprised to discover that when the Birks building opened in 1913, it took out three of Vancouver’s earliest office buildings, including the four-storey Sir Donald Smith block (named for Lord Strathcona) and designed by Bruce Price in 1888.

The Donald Smith building opposite the first Hotel Vancouver at Granville and Georgia in 1899. Courtesy Vancouver Archives Bu P60

The Donald Smith building opposite the first Hotel Vancouver at Granville and Georgia in 1899. Courtesy Vancouver Archives Bu P60According to Building the West, New York-based Price was one of the most fashionable architects of the late 19th century. He was the CPR’s architect of choice for a number of Canadian buildings, and although he designed several imposing buildings in Vancouver between 1886 and 1889, not one of them remains today.

The Van Horne block (named for the president of the CPR) at Granville and Dunsmuir, later became the Colonial Theatre, and one of Con Jone’s Don’t Argue tobacco stores, before becoming another casualty of the Pacific Centre in 1972 (see Past Tense blog for more information).

Originally known as the Van Horne building at 601-603 Granville, built in 1888/89. Courtesy Vancouver Archives 447-399 in 1972.

Originally known as the Van Horne building at 601-603 Granville, built in 1888/89. Courtesy Vancouver Archives 447-399 in 1972.Price also designed the Crewe Block in the 600-block Granville: “built of brick and granite, with sixteen-inch pilasters running the height of the three-storey structure”* It lasted until 2001.

The granite-faced New York block (658 Granville) which Price designed in 1888, and the Daily World described as “the grandest building of its kind yet erected here, or for that matter in the Dominion,” would be replaced by the existing Hudson’s Bay store in the 1920s. According to the 1890 city directory, the building had a mixture of residents and businesses including the Dominion Brewing and Bottling Works, the CPR telegraph office, and John Milne Browning, the commissioner for the CPR Land Department.

1890 Vancouver City Directory

1890 Vancouver City DirectoryBrowning lived at West Georgia and Burrard in a stone and brick duplex that Price designed, described as “Double Cottage B.”* According to Changing Vancouver, sugar baron BT Rogers bought the property in 1906, and had the house lifted, enlarged and turned into a hotel called the Glencoe Lodge.

The Brownings home in 1899 would become part of the Glencoe Lodge. Courtesy Vancouver Archives Bu N414

The Brownings home in 1899 would become part of the Glencoe Lodge. Courtesy Vancouver Archives Bu N414The hotel was torn down to make way for a gas station in the early 1930s, and 40 years later, was bought up by the Royal Centre and is now the uninspiring Royal Bank building.

The corner of Georgia and Burrard Streets since 1972. Courtesy Google map

The corner of Georgia and Burrard Streets since 1972. Courtesy Google map *source: Building the West: early architects of British Columbia

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

September 23, 2017

The Brutal Murder of Vancouver Poet Pat Lowther

Pat Lowther died on September 24, 1975, her head smashed in with a hammer at her East Vancouver home. This is a short excerpt from At Home with History: the secrets of Greater Vancouver’s Heritage Houses.

The mustard-coloured house where Pat and Roy Lowther lived on East 46th Avenue near the cemetery, is a three-storey, classic kit home with a welcoming front porch and stained glass on the front door. There’s a church at the end of the street.

566 East 46th Avenue. Eve Lazarus photo, 2006

566 East 46th Avenue. Eve Lazarus photo, 2006Pat, who was just 40 at the time of her murder, grew up in North Vancouver. The Vancouver Sun published her first poem when she was 10. She published her first collection of poems in 1968 and taught at the University of BC’s creative writing department. A Stone Diary, the book she was most known for, was published after her death.

At the time of her murder, Roy Lowther, 51, was a failed poet and teacher. They had four children—two were from Pat’s first marriage.

Vancouver poets Pat Lowther and Fred Candelaria, three weeks before her murder in 1975. Courtesy Vancouver Sun and Kate Bird (Vancouver in the Seventies)

Vancouver poets Pat Lowther and Fred Candelaria, three weeks before her murder in 1975. Courtesy Vancouver Sun and Kate Bird (Vancouver in the Seventies)A week after she’d last seen her mother, Pat’s daughter Kathy went to police and reported her missing. Roy told police that his wife was having an affair with a poet in Ontario, and he assumed she’d gone there to be with him. Police checked airlines, rail and bus companies—no one had seen her.

Three weeks later, a family hiking at Furry Creek found her body lying face down in the water—her head and shoulders jammed under a log. The body was badly decomposed and police identified Pat from fingerprints and dental records.

A search of the couple’s bedroom turned up 117 blood spots on the wall. Police found a blood-stained mattress and a hammer at the Lowther’s house on Mayne Island. Roy was charged with murder.

566 East 46th Avenue in 1985. Courtesy Vancouver Archives 790-1979

566 East 46th Avenue in 1985. Courtesy Vancouver Archives 790-1979Roy’s lawyers put up a fascinating defense. Roy admitted to finding his wife’s naked, battered body in the upstairs bedroom. He thought that the police would suspect him, he said, so he decided to get rid of the body. He put his wife in the family car, drove to Furry Creek, threw her body over a cliff, and hoped she wouldn’t be found.

A reporter attending the trial described Roy as unhealthy looking. “His ill-fitting grey suit jacket—perhaps it was once royal blue—hangs on his frame like a burlap sack and the doubled- up folds in his waistline suggest a drastic loss of weight.”

Pat’s lover also attended the trial. He was described as a chunky Ernest Hemingway in a tweed sports coat—”a short, rumpled intellectual obviously uncomfortable with the entire affair.”

Roy was convicted of murder and died in prison eight years later. In 1980, the League of Canadian Poets established the annual Pat Lowther award.

For more on how Pat’s murder impacted her two young daughters see Christine Lowther’s book Born Out of This.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.