Scott Timberg's Blog, page 7

October 5, 2017

Gillian Welch and Dave Rawlings, Darker Than Ever

LAST night, seeing Gillian Welch and Dave Rawlings play their last real LP, 2011’s The Harrow and the Harvest, at the Orpheum in downtown LA, I realized that this was not just a record that I liked, or one that had made me play around with a couple of its songs on guitar, but one of the finest and most timeless albums of the last decade.

It’s got songs like Scarlet Town, Dark Turn of Mind, Down Along the Dixie Line, and The Way the Whole Thing Ends, all of which grow in liver performance.

Here is the LA Times piece I wrote on the two, when Harrow came out six years ago and after hanging out with them for a few hours.

This is a piece I ghosted with Gillian for Salon; here she talks about her interest in scary old folks songs. “This tradition connects with why people make art – to deal with the gnarliest, most painful events that occur. Things beyond your control, almost beyond human understanding.”

I look forward to more cheery and  uplifting work from Gillian and Dave.

uplifting work from Gillian and Dave.

September 29, 2017

Patti Smith in All the Poets

FOR the last few months I’ve been doing a series on musicians and their interest in literature and writers for the Los Angeles Review of Books. So far, all of these have been strong interviews with artists I love about figures I share an ardor for. In some cases, the conversations have taken me down intellectual alleyways I did not expect to go, which is even better. Each interview has been quite different from the last.

Patti Smith is by all measures a major, deeply influential musician going back to the mid-’70s: She was a kind of godmother to the New York punk movement. She’s drawn acclaim for her memoir Just Kids and other writing, as well as her advocacy of French poetry.

Smith now has a slim, strange new book called Devotion on Yale University Press, which blends a meditation on creativity with a fable-like piece of fiction. (This blog is inspired, of course, by my own book on YUP, Culture Crash, so I probably don’t have to underline how proud it makes me to be labelmates not just with Greil Marcus and Terry Eagleton but the great Ms. Smith.)

The interview with Smith, which took place a few hours after she walked in from a trip to Mexico City (for what I take it was a memorial event for Sam Shepard) was wide-ranging and, at least for me a lot of fun. For reasons of length I had to leave out a few lines, such as her fondness for Powell’s Books in Portland, her love of the early Camus novel, A Happy Death, or the difference between John and Paul. (Beatles, not Bible.) But the review busted out its word length — hat-tip to my editor Boris Dralyuk for the space — because of our shared love of her work.

Here, then, is my All the Poets interview with the great Patti Smith.

September 26, 2017

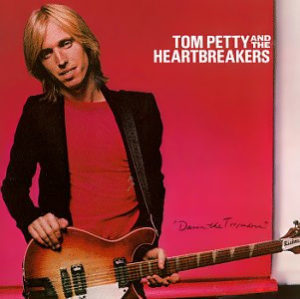

Tom Petty at the Hollywood Bowl

LAST night, Tom Petty concluded a lengthy tour with the third of three shows at the Hollywood Bowl. The tour was designed to look back at 40 years with his band, The Heartbreakers, and is rumored to be the group’s last go-round together. As a music fan who grew up in the ’80s, who heard song after Petty song on both AOR and the local “modern rock” station, it was like a part of my youth was about  to die. So though I’ve never seen Petty live before, and tend to avoid arena-rock shows, I was not gonna miss this one.

to die. So though I’ve never seen Petty live before, and tend to avoid arena-rock shows, I was not gonna miss this one.

The striking thing about Petty, whose breakthrough came with Damn the Torpedoes in 1979, is just how many radio-ready hits he’s produced over the decades. Last night’s Bowl show saw him rip out I Won’t Back Down, Free Fallin’, Breakdown, Refugee, Yer So Bad, Don’t Come Around Here No More, and an encore of American Girl, as well as a few numbers devoted to the cult-favorite Wildflowers record. The Heartbreakers are one of the best bands going, the Bowl is a lovely place to see any musical act — whether Massive Attack or the LA Phil — so while there were no surprises, this would make a more than respectable, almost triumphant last show if it does indeed mark the band’s conclusion.

What stood out for me the most, I think, was the Heartbreakers’ playing. August Brown of the LA Times recounts a wonderful anecdote, here, about how Petty met Mike Campbell, his longtime guitarist and co-writer, when both were teenagers back in Gainesville, FL: It’s got to be one of the great partnerships in rock history. Benmont Tench, the band’s longtime pianist and keyboard player, and someone I’ve seen sitting in at Largo, is also a titan, a player who manages to be tasteful and soulful in equal measures: It’s hard to imagine these songs without his instrument’s voice on them.

Petty comes from a genre I generally don’t much like — “classic rock” or “heartland rock.” So much of the music forced down my and other Gen Xers’ throats in the late ’70s and ’80s through radio, movies, and commercials has not aged well. But Petty’s songs, perhaps because they are rooted in the timeless verities of the early Byrds and Mick Taylor-era Rolling Stones, still sound great.

I guess my only disappointment — besides the fact that Petty skipped two of my favorite of his songs, The Waiting and Even the Losers, both from the Byrdsy end of his songbook — is the arena-rock feel of the whole thing, especially the huge video projection of the band behind the actual stage. It emphasized the side of Petty that is — for all the craft of his songwriting and the artistry of the players — a bit corporate and synthetic. Still, this was a show played with force and love, and it’s hard to imagine anyone who digs Petty’s songs not leaving with a sense of satisfaction and joy.

The opener was Lucinda Williams, who has been making records for nearly as long as Petty. If I had a band, I would not want Williams to open for me: While she’s been a great songwriter for decades now — King of Hearts goes all the way back to 1980 — it’s the strength and focus of her band, Buick 6, that I’ve been struck by over the last few years. She’s been with this group, built around Stuart Mathis’s guitar, for several tours now, and between the genius of her songwriting and the hard-charging musicianship of the backing band, these performances become epic.

Williams played for almost an hour, dedicating a song to the late Chris Cornell and playing Pineola, Drunken Angel, Essence, Honey Bee, Sweet Old World, and as a ranty/ rousing version of Joy. (She has re-recorded her very fine 1992 LP, Sweet Old World; the new This Sweet Old World comes out this week.) At its best, her set was like a twanged-out Texas version of Television. At the very least, it was a tough act to follow.

September 21, 2017

Guest Columnist: Ken Burns’ Vietnam

MUCH of the nation has been debating the latest Ken Burns documentary, which I — the son of a Marine officer nearly killed in 1967 — have not yet had the stomach to watch. This essay on the war comes from regular CultureCrash guest columnist Lawrence Christon, born the same year as my late father, and a fellow Marine with all kinds of complex and conflicted feelings about the conflict. Here he is.

The War That Never Ends

By Lawrence Christon

On a recent flight to Huntsville, Alabama, I sat next to a young career Army officer who mentioned that a lot of GI’s returning from Afghanistan and Iraq, and showing symptoms of PTSD, don’t want to talk to therapists who haven’t seen combat. Their reason? The therapists can’t possibly treat a malady without understanding the condition that created it. And they can’t understand it unless they were there.

Now that the 10-part Ken Burns-Lynn Novick documentary, “The Vietnam War” is airing on PBS and national commentary has mushroomed in countless print and media outlets, I can feel the low moan, the weary “Oh, shit” muttered into the indifferent air, by anyone who, like me, was around at the time: It was all too crazy, too brutal, too senseless, too caught up in a swirling abyss that seemed to envelop the whole country and leave it with a massive morning-after headache of pain and regret. Can’t we just let it go?

The more interesting question is: Why can’t it let us go?

Generations have filled up the census rolls since Vietnam and the ‘60s—I’m reading now about the attitudes of Millennials who have no knowledge of what it was like to live in the age of the Cold War and its background hum of Mutually Assured Destruction (appropriately tagged with the acronym MAD). There’s been the Reagan Revolution, the Clinton Expediency, the hi-tech revolution, the savings and loan crisis, 9/11, the sub-prime mortgage crash of ’08, globalization, the Obama years, the fat-cat international corporate state and the average Joe trying holding on until the next payday while hearing it about identity and gender. Fox News. The Culture of Complaint. You name it.

Behind it all, the ghost in the machine, if you will, is Vietnam. It still whispers of geopolitical power, epic violence, race, campus unrest, street demonstrations, attacks on and by the press, and angry factions yelling past each other. And yes there’s the push for equality and justice, access to education and the voting booth, the sanctity of liberty and law, and the urge for truth to power. The forceful sentiments and even a lot of the vocabulary are still with us, but they began with the war in Vietnam, which went from a skeleton crew of army advisors in the mid-to-late 50s to division-sized troop deployments, Cavalry and Special Forces units, helicopter squadrons, and supply and command bases the size of cities, all in place by the mid-60s.

By then the news about the futility of both American military operations and political strategies began to reach the increasingly fretful Johnson administration and the ears of Hometown U.S.A., along with a rising number of body bags. Grief and consternation began boiling over into rage and the spooky sense of the war flaring up at home, as if Vietnam and the U.S., sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll, all fed off the same deranged power grid.

It’s virtually impossible to fault anything about the Burns/Novick documentary’s nobility of intention and thoroughness of reportage, which includes film footage—among other things, Vietnam was our first televised war—and plenty of commentary from writers and reporters; military figures from both the Vietnamese and American sides; political history from all factions and the story of Vietnamese conflict going back to 1858; a macro view threaded with heartbreaking personal stories; the mounting wreckage of the Johnson presidency and the physical toll on the man himself. The figure who set out to eliminate racism and poverty in America became the most viciously reviled man in modern history.

“The War in Vietnam” depicts the emotional and physical agony of men in combat as well as the horror, desperation and ruin of civilians caught in the conflagration, made more ghastly by depiction of the country as a magical Shangri La inhabited by a graceful, gentle people, albeit bent on national unification. And it doesn’t stint on the damage done when those in power lie to the public, or the steadfast American ignorance of Vietnamese history and culture. (The mind of the average grunt never saw them as anything other than “dinks” and “slopes.”)

But there are other forms of examination of, for want of a less pretentious term, the American condition that are beyond the film’s scope. After all, when Auden wrote, “Mismanagement and grief/ must we suffer them all again?” he wasn’t writing about Vietnam but the beginning of World War II. War has been a feature of human experience ever since homo erectus first got on his feet. But the American promise has been founded on a rock of loving peace and freedom, a spiritually fervent city on a hill. Still, our literature reveals something else in our character, the flight from civilization in Natty Bumppo, the metaphysical conceit of Ahab (“I’d strike the sun if it offended me”), the American soul described by the intuitive Brit D.H Lawrence as “hard, isolate, stoic, a killer.”

“You honestly didn’t know whether to laugh or cry,” wrote Michael Herr in “Dispatches,” which definitively caught the lunatic mix of the horrible and gut-wrenching Vietnam of “mad colonels and death-spaced grunts.” “Few people ever cried more than once there, and if you’d used that up, you laughed; the young ones were so innocent and violent, so sweet and so brutal, beautiful killers.”

I know who they were; I still keep the roster of fellow recruits who made up my Marine Corps platoon in Parris Island, November 1963, two weeks after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. I know who the guys coming back from Iraq and Afghanistan are too, though I’ve never met them. I understand the benefits of therapy, of easing the nightmares and panic attacks and getting people to function again in the World.

But if you concede that the political is personal, than you’d have to go one further in allowing the personal to be private. Silence is a form of freedom, sometimes the only refuge one has left. You have to be careful about asking a person to give it up.

September 20, 2017

The Artistry of Siegfried Tieber, Magician

Photo Lisa Whiteman

THE other night I was invited to a private session at the Magic Castle in Hollywood with a young magician. Siegfried Tieber — his real name, apparently, with no relation to the lion-baiting duo — practices close-up magic, which typically involves cards, rings, dollar bills, and other things that can be observed in small rooms with no smoke and mirrors, no rabbits, no disappearing dwarves.

I’ve been a casual/ on-off fan of close-up magic for more than a decade, ever since I researched an extensive newspaper piece on magicians in Southern California and began occasional trips to the Castle. (A few years back, my son celebrated a birthday by hiring a pretty serious close-up magician to entertain a group of seven or eight-year-olds.) But I am far from an expert on the subject.

In any case, I was entirely knocked out by Siegfried’s artistry and style. Somehow, the Ecuadoran-born, Austrian-descended lad manages to be both deeply sincere and almost campy in his enthusiasm, and despite a heavy accent and some fumbling for words he communicates quite well verbally.

I spent more time speaking to him than seeing him perform,

Photo by Lisa Whiteman

but once my small group commandeered an empty room at the Castle, with just a table and chairs and a stray group dressed up for an office party, Siegfried pulled out some cards and simply knocked us all out.

This weekend — through Oct. 8 — he will be leading a small performance called See/Saw at Civic Center Studios in downtown Los Angeles, here. (There will, apparently, be twins.) I don’t often write about magic, close-up or otherwise, but as someone who tries to shine a light on talent and invention, I could not resist. Here is my conversation with Siegfried Tieber.

You’ve talked about close-up magic as an art form. What does it have in common with traditional arts like chamber music or landscape painting?

Wow, this is an exciting question! Magic—like chamber music, landscape painting, name-your-favorite-art-form—is a means of expression. Different art forms are better at communicating different ideas and evoking different emotions.

Chamber music appeals to the abstract. In landscape painting we can appreciate the craft and technique used to portray reality. Magic combines sleight of hand and applied psychology to create the illusion of something impossible. Ultimately, all art forms appeal to the emotions. Art, I deeply believe, needs to transcend the intellect and hit us on an emotional level. Magic is very good at this.

Can you give us a rough sense of your road from your boyhood in Ecuador to your career as a magician here in Los Angeles — how you got here, and what drew you to LA?

I was born and raised in Ecuador. I went to high school there and at age 18 enrolled at University for Mechanical Engineering. A few months after that, a friend lent me a book on magic tricks. I picked one trick from the book and practiced relentlessly. One glorious Sunday afternoon I gathered my family in the living room of my parents’ house, showed them this one trick and they freaked out. They reacted effusively, and I reacted to their reacting. That was the first time I realized the huge potential magic has. And I fell in love.

Fast forward 5 years. I graduated from Mechanical Engineering, and told my parents I wanted to do card tricks for a living. I was doing very well financially but realized that ther

e wasn’t much room for artistic growth (not many mentors, influences, people to look up to) in that beautiful, tiny country where I was born.

In 2012 I moved to LA to be around the Magic Castle. In 2015 I performed there for the first time: a dream come true.

You studied magic, I think, in the context of a theater education. How does your training in theater and acting shape the way you operate as a magician?

When I moved to Los Angeles I enrolled at a two-year Conservatory Program in acting. Magic involves different skills, for me the performance aspect of it is one of the most important. Training in theater and performance gave me the basic tools of an actor: it taught me how to stand, move, speak on the stage. As simple as this sounds, this takes time—and work—to learn.

I also learned how to work from a script. Close-up magic is highly interactive and the course of the performance is influenced by the audience-participants, but a script is a very useful tool for a magician.

You’ve achieved some fame through an appearance on Penn and Teller’s show. How long have you known their work, and do you feel congruent at all with what they do?

Penn and Teller are the rare kind of artists who have achieved both commercial success and critical acclaim, they have made invaluable contributions to the art of magic and, personally, they are two of my heroes. Being in their show, on their stage, was one of the greatest honors and one of the most exciting experiences of my life (they said very nice things about my performance, which also makes me immensely happy).

I became aware of them when I was still living in Ecuador, 2 or 3 years after I got interested in magic. Since then, I have obsessed over their work. They have been a major influence in my work as a performer.

You’re younger than most, a South American immigrant, and have a distinctive hairstyle. Otherwise, how do you think you differ from the majority of working magicians today?

I’ve been told that my approach to performance, specially to close-up magic and to the interaction with the audience-participants, is unique. I laugh, yell and get very excited when I perform. I’m not faking it, it’s not a theatrical device or a conscious strategy, I genuinely get very excited. Performing makes me very happy. People have mentioned that this resonates with them.

For me, magic is all about co-creating an experience that all of us can share and celebrate together. I’d like to think that’s what I bring to the table when I perform.

Give us a sense of what you’ll be doing at your run of shows in downtown LA.

See/Saw is an exploration of the art of conjuring with playing cards, and an invitation to have a conversation about the art of magic. It is an intimate experience and a performance of magic, up close.

Magic is an unconventional art form that most people don’t experience very often, so we want to give our guests insight into it. I want people to see magic the way I see it. I want them to fall in love.

September 18, 2017

Brad Mehldau and Chris Thile at the Ace Hotel/ LA

IN some ways, this pairing makes absolutely no sense — a jazz pianist and a bluegrass mandolinist, playing together? But in another, it’s nearly inevitable. And, the other night, not just a natural union but often a spectacular one.

Brad Mehldau and Chris Thile are not just universally well-regarded musicians but also virtually parallel figures. Both are (still) reasonably young players who are simultaneously innovators and traditionalists, and both have drawn acclaim for playing music outside the traditional repertoire of their instruments. For Mehldau, it’s Radiohead and expansive versions of Beatles tunes, for Thile, it’s rendering everything from Bach to the blues to postmodern everything on the humble mando.

Finally, and especially relevant to the new project: Both musicians are in a historical sense on the edge of their respective instruments. That is, Mehldau is a white man playing an instrument whose development has been dominated by Hines, Tatum, Powell, Monk, Tyner, and other black players (and yes, yes, I’ve heard of Bill Evans) while Thile is a mandolinist from outside the South. (He grew up near San Diego, mostly, and now lives in Portland.) But they play their instruments with little irony or distance, and are able to get “inside” the tradition in ways that a lot of avant-players can’t. (Ie. witness Mehldau’s recent — and devastating — Blues and Ballads LP.) It may be worth noting, too, that both musicians have well-documented relationships to depression and heartache — they maybe fairly young, and quite celebrated, but they’ve both been through a lot.

This is a long way of saying, Friday’s show, put on by UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance in the first of its beachheads in downtown LA , encapsulated all the tensions and contradiction between the two, but with the impossible-to-describe quality of brilliance along for the ride. Both are flashy soloists but have long record of working in groups, and that sense of empathy was very clear Friday night.

They drew heavily on their Nonesuch LP — the jazz standard I Cover the Waterfront, a Gaelic number by an Irish harpist, Dylan’s Don’t Think Twice It’s Alright, and a few songs with LA roots, Fiona Apple’s Fast as You Can, Elliott Smith’s Independence Day. The level of improvisation — one of the hardest things to put into words — was simply beyond description.

The encore, the Gillian Welch/ David Rawlings number Scarlet Town, from the duo’s last studio record, brought out especially fascinating lines from Mehldau.

Given the strength of the two lead voices — the piano and mandolin — the third, Thile’s voice, is not quite an equal partner. Part of me craved a cameo by a Bessie Smith-style blues singer or a Joe Henderson-type tenor saxophonist to give a song or two some added thrust.

Thile’s singing is fine, but not much better, and while it put me off the LP a bit, in concert it fit in perfectly. I’ll return to the album with new ears, as the precursor to a magical evening.

August 25, 2017

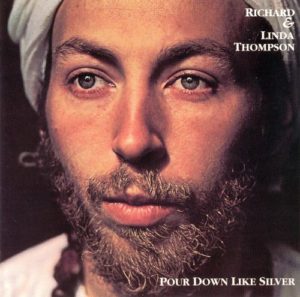

The Literary Richard Thompson

FEW living musicians fascinate me as much as Richard Thompson, the London-reared, Los Angeles-dwelling, Fairport Convention-founding guitarist and songwriter whose recording career just hit the 50 year mark.

I’ve been listening to Richard’s work for three decades now — since I first heard “Valerie” and “A Bone Through Her Nose” on WHFS as a teenager — and have been meeting or speaking to him for nearly a quarter century. I’ve been struck, over the years, by what a serious thinker and deep reader he is, and by the role things outside music play in his songwriting and sense of mission.

When I started the All the Poets column for the Los Angeles Review of Books, Richard was one of the first musicians to come to mind for it. So it’s a real pleasure to have been able to correspond about his literary influences and passions.

The latest Richard Thompson record, Acoustic Classics II, just dropped this week, with Acoustic Rarities due in the fall. Here is our conversation.

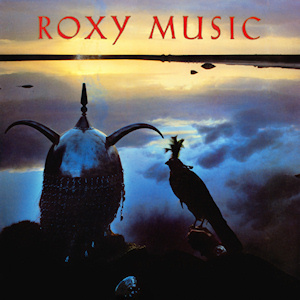

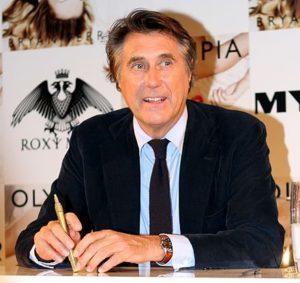

Bryan Ferry, Art, and Roxy Music

EVEN a decade after their heyday, when I first heard them in the mid-’80s, there was nothing like Roxy Music. The sleek, almost alien sound, with its world-weary vocals, European touches, and deep, if bruised, romanticism, was among the most bracing things a suburban teenager could put on his turntable.

It struck me then, and still does, as some of the first and most successful music to really make a new step forward post-Beatles. I even wrote a short story my last year of high school called Siren, named for both the fatal Odyssean beauties and my Roxy’s immortal 1975 LP. I think I had a sense that the group was coming out of something that wasn’t just rock music, but was not aware of the degree of their grounding in old jazz or their leader’s art-school training.

Three decades later, I got the chance to speak to the band’s founder and lead singer, Bryan Ferry, who has led an eclectic solo career. He comes to the Bowl this Saturday to perform solo stuff alongside Roxy songs, including some of the Avalon LP.

We spoke about his love of Ellington and Charlie Parker, and the influence of British Pop artist Richard Hamilton — some of which is in the piece — as well as his openness to working again with Brian Eno and his fondness for Prince and the painter Vanessa Bell, which is (for reasons of length) not.

My interview here.

August 24, 2017

Jazz Singer Cecile McLorin Salvant

FOR some reasons, I typically have trouble with jazz singers after, oh, Sarah Vaughan or Abbey Lincoln. There may have been some great ones over the last two decades, but most of the time I’d rather listen to a pianist or horn player.

But when the debut LP from a young woman from Miami — then still in her early 20s — arrived in the mail to me a few years ago, it hit me directly. And this weekend, Cecile McLorin Salvant opens the Bryan Ferry concert at the Hollywood Bowl.

I spoke to Salvant about a week ago and found her extremely sharp and engaging. Here is my piece. See you at the Bowl.

August 22, 2017

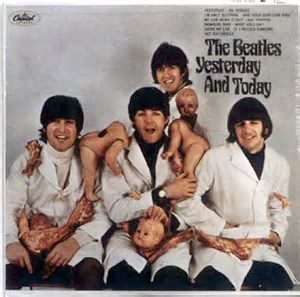

The Beatles After The Beatles

I THINK it was the writer Michael Chabon who once told me he loved family partly because it gave him a glimpse at four different generations and the way they saw the world and its history — starting with his grandparents and all the way down to his own children.

That’s the way it is for most of us, including me. My situation is unusual though not unheard of: My folks were just the right age (born the same years as the actual Fabs) to connect deeply with the band, and to see them change as the world changed. I was born the year the group broke up, so it was already a historical phenomenon, like the poems or Yeats or the films of Hitchcock. And I loved them as much as, perhaps more than my folks did, as emblems of a lost world.

My son, who rejects a lot of what his parents have pushed on him (including customs like setting the table and taking frequent baths) gravitated to the group as if by instinct, connecting directly with the Beatles for Sale record as a toddler and singing and playing on piano songs like Nowhere Man and Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds since.

My grandfather, by contrast, considered the Fabs to be charlatans or lightweights. A vaudevillian and Tin Pan Alley songwriter, he was of the generation and the Irving Berlin-derived style that the Scousers (following Elvis and Little Richard) at least partially destroyed. (Here I will table the fact that many of their songs, especially Paul’s, drew from the American Songbook and in some ways renewed its genius.)

I’ve been thinking about the Beatles in history — or the Beatles as myth — lately because of a fascinating new book that I read in just a few days, like candy (or a really drinkable Pinot of the kind I can’t usually afford.) I spoke to the author Rob Sheffield, like me a Gen-Xer who grew up after the band was done, about his book Dreaming The Beatles, here.

lately because of a fascinating new book that I read in just a few days, like candy (or a really drinkable Pinot of the kind I can’t usually afford.) I spoke to the author Rob Sheffield, like me a Gen-Xer who grew up after the band was done, about his book Dreaming The Beatles, here.

Hope readers enjoy this as much as I did.

Scott Timberg's Blog

- Scott Timberg's profile

- 7 followers