Scott Timberg's Blog, page 9

June 17, 2017

The Late, Great Kevin Starr

LIKE a lot of people, I was originally baffled when I moved to California, which in my case was 20 years ago, this July. Some of the key to its complex code arrived in the books of historian Kevin Starr, which begin with statehood and move epoch-by-epoch to the early post-World War II years.

Today I have a sort of appreciation of the man, who I regret to say I met only once. (He was entirely gracious/ humble, and greeted me as “a fellow toiler in the vineyards of California history,” which I did not quite deserve.)

“He saw the state as one giant narrative,” Gustavo Arellano, the OC Weekly editor known for his Ask a Mexican column, told me. “So much California writing takes only one piece.” Part of the reason this expansive style has fallen out of fashion, Arellano says, is because much scholarly history over the last few decades has been dedicated to overlooked subaltern groups — peasant women, racial and ethnic minorities, working-class men — or specific forgotten figures.

“Starr was an old-school historian, who came up before Chicano Studies,” Arellano said. “He was smart enough to know he had to tell those stories too.” Arellano has been reading Starr’s work since he was a college student, and continues to rely on it as a reference for his journalism, including his regular pieces on OC’s racist and right-wing roots.

One of the puzzles of Starr’s long and productive career was his inability to write a book on the period of his adult life — the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s — which were fascinating and important years for California.

“I wish I knew the answer,” historian William Deverell of USC and the Huntington says of the three-decade gap. “That period demands a kind of Kevin Starr capaciousness. We will miss that book — it may have been too personal.” Indeed, Starr told my wife, when she interviewed him on his imperfect ’90s volume, Coast of Dreams, that he had trouble making sense of that era, especially its darker themes, no matter how hard he tried.

Starr was born in 1940, but there was something old-school about him from the start. Says Deverell: “Kevin was the kind of guy who, when he got a cane, everyone was like, ‘Yes — he’s someone who should have a cane.’ ”

One thing sometimes overlooked about Starr, in part because of his Ivy League style and his affinities with the era of his grandparents, is that he was a great lover of music, from collegiate fight songs to rock n roll.

“The early ‘60s Beach Boys were bringing California to the world,” Deverell says of one of Starr’s favorite groups. “Kevin did that too.”

The list of historians who’ve really shifted the way we see a region or era is not terribly long. W.E.B. DuBois remade our understanding of Reconstruction, racism and capitalism in the first decade of the 20th century, C. Vann Woodward destroyed Southern nostalgia in a series of essays on the burden of the region’s history, Gordon Wood revealed the radicalism of an American revolution known popularly through three-cornered hats, and Eric Hobsbawn reframed “the long 19th century” around class conflict and imperialism.

Was Starr able to do the same for California?

Was Starr able to do the same for California?

In any case, here is my piece for Zocalo Public Square.

June 6, 2017

Pianist Vijay Iyer and the Ojai Music Festival

This year sees an unlikely but, I suspect, fortuitous paring: Pianist Vijay Iyer — one of the most inventive figures in jazz today — is curating the Ojai Music Festival, a friendly, mellow outdoor gathering dedicated to new, challenging, and rarely performed classical music. (The festival starts Thursday and runs through Sunday.)

Part of Iyer’s emphasis is presenting music by the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, a group of Chicago jazz figures founded in the ‘60s and dedicated to progressive racial politics and adventurous musical possibilities. (One of the AACM’s key members, Anthony Braxton, taught a jazz history class I was lucky enough to take, many years ago.)

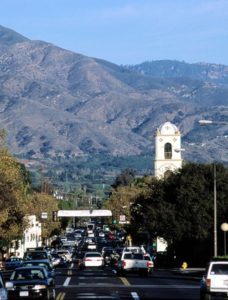

Your humble blogger has visited Ojai, on and off, for two decades now, but for complicated reasons, I’ve not been for three years. So I’m very much looking forward to what elapses this weekend.

What follows is my phone conversation with Iyer, who lives in New York City and teaches at Harvard University.

So you’re a bit of an atypical choice to helm the Ojai Festival; you’re best known as a jazz pianist. On the other hand, you make perfect sense, since the festival has been defined by a kind of eclecticism. How do you see yourself fitting into what Ojai has done over the years.

I don’t really feel pressured to fit in — I’m just doing what I like to do. I’ve brought a lot of my friends along, people I respect, artists whom I trust. That’s really all there is to it.

As you say, I’m best known as a jazz pianist, but nobody is one thing, really. Especially not today.

Did you grow up with classical music? And whenever it hit you, who were the first composers or styles that knocked you out?

Well i don’t really believe in styles. I think styles are fictional unities and ways of stereotyping about people. So i don’t find that a useful concept or approach.

But i grew up playing music in two very different ways. One was that I started Western classical violin lessons at three, and continued that for 15 years — in orchestras, playing solo repertoire, in chamber groups. So a lot of different things.

Did it feel like something for your parents sake or something you got into at some point?

I think what energized me about it was playing in ensembles, playing with people. The way you study, and in private lessons the emphasis is solo repertoire, perfecting  these pieces that have been played millions of times by other people.

these pieces that have been played millions of times by other people.

But the second parallel track, when I was growing up, was that I played piano by ear, at the same time, so i was always improvising at the piano, picking out melodies, and figuring things out and just screwing around basically, on the piano. That eventually developed in a very different way, in a different musical sensibility that was in contrast to my training on the violin.

The music that impacted me when I was about five. I also remember listening to the soundtrack for Saturday Night Fever — that record, when it came out… And I was very into Michael Jackson and Prince, the Police…

Then when I was in high school I became more aware of the African-American composers and improvisers associated with the word “jazz,” started delving into that more seriously. We had a very good jazz ensemble at my high school: They let me in as a pianist and that let me study that musical language, that repertoire in more depth.

In the orchestras we played Rachmaninoff and Borodin and Smetana, a lot of Eastern European stuff. But then also Scandinavian — Sibelius — Brahms… I played concertos by Bruch, Saint-Saens… And I was also studying Thelonious Monk’s music, Duke Ellington’s music, Coltrane’s music, Randy Weston’s music, Andrew Hill, Alice Coltrane, Charlie Parker, a lot of stuff.

While Prince is on the radio around you…

I was a huge Prince fan from basically ’81 to the mid-‘90s; I was obsessed with his music. I saw him a few times; that really stuck with me.

Improvisation has been a part of classical music in the past, but it’s nowhere near as central to it now as it is to jazz. I wonder if you think classical music could be more robust and full of possibility if it restored that lineage that it’s mostly abandoned.

I’m not gonna advance any thesis like that. Because I don’t have any allegiance to a construct called classical music. Nor to a construct called jazz. I’ve been quoted by the Ojai press people as saying we should replace the idea of genres with  community. It’s not about styles, it’s about people, and what people find themselves doing over time…. If you treat it as a style that’s static and has issues with itself, as opposed to a community that evolves and interacts with other communities… Its borders are only as solid as they police themselves to be.

community. It’s not about styles, it’s about people, and what people find themselves doing over time…. If you treat it as a style that’s static and has issues with itself, as opposed to a community that evolves and interacts with other communities… Its borders are only as solid as they police themselves to be.

So when we think of it as a group of human beings working together, it’s got more of a sense of ethics and responsibility…. It’s about, What are people in that community looking to do today?

You say I seem like an outlier, but I think it’s part of a larger trend, in this system called classical music electing to create change.

I don’t know how it’s working elsewhere, but in the last few weeks I’ve been to the LA Phil for an Iceland Festival which included Sigur Ros and ended with this virtual-reality Bjork thing that was very cool; I saw Brooklyn Rider play new music at a hall in Beverly Hills, this summer at the Hollywood Bowl has several mergings of classical and indie rock… So I know its getting more eclectic around the edges. I wonder how representative of the larger world of classical music this is. I’m happy to see the fissures around the edges.

I guess the more interesting question to me is, What kind of sense of resp onsibility does that classical music community feel toward artists of color, music made by people of color in the West, especially people of African descent in the West. Because for a long time, the term classical music has been a code word for whiteness, for music and art and people of European descent. And it’s been willfully and persistently excluding anyone else from that category. So this is the peril we encounter when we talk about stylistic eclecticism — we’re not talking about people. I’m interested in, What is the music doing? And who is it doing it for?

onsibility does that classical music community feel toward artists of color, music made by people of color in the West, especially people of African descent in the West. Because for a long time, the term classical music has been a code word for whiteness, for music and art and people of European descent. And it’s been willfully and persistently excluding anyone else from that category. So this is the peril we encounter when we talk about stylistic eclecticism — we’re not talking about people. I’m interested in, What is the music doing? And who is it doing it for?

You have at least a few events dedicated to the AACM, including a piece by Anthony Braxton. What makes that era, that movement important to you?

When I think of the questions we’re addressing here, I realize, there’s a legacy of people addressing these questions for half a century. And they picked up where others left off. So Braxton, Muhal Richard Abrams, Roscoe Mitchell, Wadada Leo Smith, George Lewis, and a younger generation… And George Lewis’ opera is about the AACM — it’s about a collective of musicians on the segregated South side of Chicago, who decide to create a new world for themselves, in the music that it’s portraying. That music creates its own historical trajectory. And I’ve been mentored by all of these people.

Over the two years that we took programming this thing — Tom Morris and I — there was a mutual interest in shining a light on that body of work, that body of artists. And continuing their presence in the festival — George Lewis’s music has been performed at the festival before.

Those artists paved the way for what I do; they created the reality that I exist in, to put it bluntly.

June 2, 2017

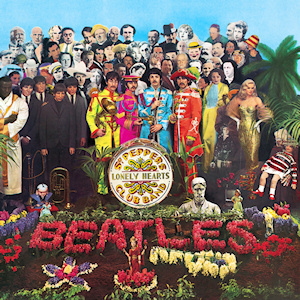

Sgt Pepper’s at 50

SO, you may have heard that a famous record from the ‘60s is marking an anniversary. If you’ve not heard more than you can stand about Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band — which the Beatles released 50 years ago today, in the States — let me offer the assessment of a longtime Fabs fan whose teenage years were in the ‘80s and whose most zealous listening years were probably in the 1990s. That is, I approach this record with zero Boomer nostalgia, a scourge I’ve worked to combat for a long time.

Part of what’s interesting about the album is how polarizing it is. For every statement about how it’s the greatest achievement of the greatest-ever rock band, there is something like Richard Goldstein’s New York Times Review, comparing the album to a spoiled child and calling it “busy, hip, and cluttered,” or a recent LA Times review which rehashes some of the old complaints. Similarly, the new remaster by Sir George Martin’s son Gilles, which I’ve not yet heard, has been hailed as a masterpiece beyond all masterpieces.

I expect I am not unique as a Gen X Beatles fan of having come of age with the weight of this album hanging over my entire record collection, not unlike the original Woodstock concert or, in another idiom, Eliot’s The Waste Lane and Joyce’s Ulysses. There’s no question that the album which sparked the Summer of Love and came out while the Fabs could still do no wrong created a great sense of generational occasion when it was released in June 1967 — who was it who said that not since the Congress of Vienna had The West been so wholly unified as it was that first week?

But for a generation that came across the album in their parents’ record collections (mine had it on reel-to-reel, oddly, alongside Magical Mystery Tour and some Herb Albert extavaganza) or in their babysitter’s cassette tapes, this was a very good, maybe great album that was not quite the match of the two that preceded it, Rubber Soul (1965) and Revolver (1966). This is of course setting the bar pretty high; those are two of the very finest albums of any kind ever.

I have reassessed the album a few times since those youthful discoveries. (Despite my tender age I have been listening closely to Sgt Pepper’s for over 40 years now.)

One of those times was at a hipster karaoke session in Portland (where else?) This was my first and only karaoke experience, hip or otherwise, and it was held among younger folks, mostly in their 30s. There were no silver pony-tails, Dead-inspired tie-dyes or other Boomer-iffic fashions. (For what it’s worth, this was a series with very good backing tracks; we could really hear the album.) In any case, flipping the context of the record — it was played in order, but in the company of screaming drunk people — made clear to me just how lively this was as a collection of individual songs. On that night I was particularly struck by how good Lovely Rita is — its melody, its playful lyric, but especially McCartney’s singing bassline. There are still moments like that that jump out at me about this record.

A year or so later, I was visiting a painter friend with who I had once played acoustic country and folk, who had relocated to Asheville, NC. In his studio one night we played some of our old rustic numbers, but a college friend who plays banjo and fiddle came by and steered us to a repertoire I never would have imagined playing. (I don’t just mean the intricacy of the multi-layered production but the music itself, given my own modest instrumental talents.) On guitar, mandolin, and fiddle the three or four tunes we played were all accessible and sounded pretty damn good. (At least, they were no worse than the Wilco and Gillian Welch numbers that bracketed them.)

My final personal riff is to note that my 10-year-old son, whose initial connection to the Fabs was with The Beatles for Sale, and who has very little sense of Sgt Pepper’s as being any more “important” or portentous than A Hard Day’s Night, recently chose to do Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds in his piano lessons.

This is all a long way of saying that the obsession with the album’s production — an obsession brought on by by the Fabs and Sir George himself — and its status as a groundbreaking deep-think concept album have distracted us, I think. The concept now sounds as solid and fleshed-out as those records made from broken projects like “Lifehouse” (some of which turned into The Who’s Who’s Next LP) or The Jam’s Setting Sons. You can hear a continuity to some of it, but the Billy Shears conceit tails off after a while, and it’s hardly essential to appreciate the thing.

At the very least, this nostalgic record — infused by music hall and circus instruments, with a mournful song about a girl leaving home, another about a very young man turning 64 — in the middle of future-obsessed psychedelic hippie-dom gives the whole thing plenty of ambiguity and resonance.

One thing I hear among my friends is that there are not enough good songs on Sgt. Pepper’s — that besides A Day in the Life there is nothing like the best stuff on the previous albums. But even the sainted Revolver has Good Day Sunshine and the Motown knock off Got To Get You Into My Life, neither of which I ever need to hear again.

Rather than pick up the new version, I recently found a vinyl copy — slightly scuffed — at a record store in Ventura, CA, and have revisited it through my not-terribly good stereo. Bottom line: If we can forget about the whole “not since…” business, the whole Boomer lost-youth frame, the expectations around the band at the time, etc, we have an album with Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds, Getting Better, and Fixing a Hole all in a row, as well as Rita, Good Morning, the title track with its wacked-out guitar, and, concluding it, what may be their finest ever number and an increasingly rare case of a real collaboration between John and Paul.

And all of this was done on a record that came in a hair under 40 minutes.

The Sgt-Peppers-is-trash argument seem to me attention-getting nonsense. Goldstein, an important figure in early rock criticism, has since admitted that his stereo was broken when he listened to it and that his review was largely shaped by a struggle over his own then-closeted sexuality.

The one major critique of the album I take seriously is what a friend calls a “wrong turn” in rock history. The Beatles were so influential they certainly had a role, post-Pepper, in moving the field toward unnecessary orchestras, “progressive” rock, and various kinds of arty excursions that sound hellish and pretentious today. And heavy psychedelia, with a few exceptions like the Zombies and Love, is one of the most dated of ’60s musical trends.

So as much as it pains me to say it, some of the ground-clearing that punk had to do in ’76 and ’77 can be put at the feet of the Beatles. While Rubber Soul and Revolver have inspired bands like Squeeze, the Jam, the Stone Roses, Ride, Velocity Girl, Nada Surf, Yo La Tengo, and many others.

But I must admit, I cannot be entirely dispassionate in my judgments about this album. When I was 7 and my parents split up, my father decided to christen his new apartment by taking us kids to a record store in Annapolis, MD, to get a really good copy of Sgt Pepper’s. (I remember a clerk trying to sell us a fancy Japanese pressing of the LP, the rage back then.) I think for my old man, an album that he loved and that had some cultural weight helped reassure him that this unpleasant transition would include some hope and beauty as well. It was a sort of cultural christening.

My dad was not exactly bringing a fresh Sgt Pepper’s into his new place for nostalgic reasons, either: He had loved the band deeply, and gradually helped stir some of my feelings for them and for music in general. But somewhere in the endless seeming stretch where the Beatles were disappearing into Abbey Road Studios to make the album, his Marine troop transport rolled over a Vietnamese explosive, and his life was changed forever. That tale has been told elsewhere, but let’s just say he experienced the Summer of Love mostly in Japanese hospitals.

And when I hear the record now, I hear a collection of mostly great songs by the most formidable and inventive rock band in history, and an album with a mystical meaning to a man — now gone — who was not really able to experience it the first time around.

Long may its freak flag wave.

Cory Doctorow’s Post-Apocalyptic Utopia

THE other day I hung out with Burbank resident and globe-trotter Cory Doctorow, who is a cult figure with a very large cult. We talked mostly about his new novel, Walkaway, which is intellectually fascinating and really moves.

Will try to fill in this post a bit for now, but here is my LA Times profile.

I will point out that obvious that I find him a bit optimistic re creative-class/ technology/ copyright issues, but he’s smart, informed, and formidable at the very least.

May 28, 2017

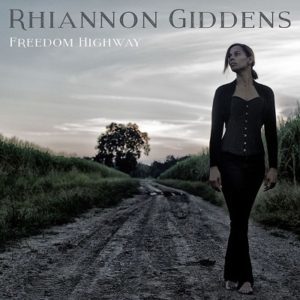

All the Poets: Rhiannon Giddens

The second installment of my Los Angeles Review of Books — All the Poets, in which musicians discuss their literary influences — went up the other day: Rhiannon Giddens, who earned her reputation with the string band The Carolina Chocolate Drops, talked to me about her childhood interest in science fiction, in the African roots of what we think of as Appalachian or country music, and why she reads history.

Giddens is quite a departure from Stephin Merritt, my first interview for the series. Oddly, they both share a love for SF, especially a kids, and a lack of interest in hip hop.

See the whole piece here.

May 18, 2017

Colm Toibin/ CultureCrash in Santa Monica

FOLKS, I’ll be interviewing the great Irish novelist — known for The Master and Brooklyn — onstage at Live TalksLA on Monday night.

Be there or be square. Fancy tickets will get you a copy of his new Greek tragedy-inspired House of Names and an admission to the pre-show reception. Come over and say hi.

May 9, 2017

Brooklyn Rider and a New Cellist

Credit Photo: Erin Baiano

The celebrated New York-based string quartet Brooklyn Rider, which appears at the Wallis Annenberg Performing Arts Center on Saturday night, added a new cellist last year. Today Michael Nicolas, who replaced founder Eric Jacobsen, spoke to CultureCrash about the group, its repertoire, and his own role in the mix.

The quartet will play music by Glass, Janacek, Beethoven, and their violinist Colin Jacobsen.

Worth pointing out that the Wallis, in Beverly Hills, has become one of your humble blogger’s favorite places to see music and theater; more on that later, I hope. For now, here is my email conversation with Michael Nicolas.

Last year you joined a group with a strong reputation and some sense of identity. It’s not quite the same as, say, Mick Taylor joining the Rolling Stones or Nels Cline taking over the guitar chair in Wilco, but I wonder, How  did you approach coming into an established quartet?

did you approach coming into an established quartet?

The group indeed has a strong and unique identity in the musical world, so when they were looking for a cellist to replace Eric, I think they sought out a musician with a similar ethos and spirit, someone like mindedly adventurous and omnivorous, and I was flattered to be considered. My career was, and still is, very multifaceted, performing just about any kind of music that I found interesting or challenging, and those values translated very easily to the new group, as we found we shared many of the same sensibilities as performers.

Who were some of your earliest cello heroes, and what was it about their playing that grabbed and / or influenced you? (I am not a cello player but still remember the first time I heard Janos Starker playing Bach.)

For me, David Soyer and the old Guarneri quartet recordings bring me back to my younger cello days, poring over their recordings, trying to unlock the secrets of their musicality, obsessing over how Soyer nuanced every phrase, whether it was a foundational bass line or a singing melody, and by studying those recordings, and later with him as my teacher, I learned a lot about musical expression, which I have kept with me since.

Part of Brooklyn Rider’s reputation comes from its choice of repertoire. What kinds of pieces do you go looking for, besides — obviously — pieces you and the rest of the guys want to play?

Part of Brooklyn Rider’s reputation comes from its choice of repertoire. What kinds of pieces do you go looking for, besides — obviously — pieces you and the rest of the guys want to play?

I think the criteria for choosing repertoire is just that, and only that: pieces we want to play. The more complicated question to answer is what is it that makes us want to play a piece, and that is a difficult one to pinpoint. Quality is paramount, but I do think that all of us place a great deal of importance on doing things we’ve never done before, to keep challenging ourselves and putting ourselves in musical situations that are new, and possibly uncomfortable. It not only keeps us on our toes, but also we grow more versatile as musicians and performers.

Where does this scene — call it the new new music or alt-classical or the chamber underground — seem to be thriving the most, besides Brooklyn? (The LA Philharmonic recently did an Iceland festival, with a Brooklyn fest a few years ago.) Is there a city with a wealth of the right kind of venues for a group like yours, and an audience and press that supports it all?

The LA Phil should really just check out their own backyard and do an LA fest, because to me there is a great fermenting of creative energy in the region, from composers to young ensembles to the more established performing arts and educational institutions. I, for one, wouldn’t mind somehow becoming a part of it, sharing in the adventurous spirit and California sun, and who knows, the Brooklyn Dodgers moved to LA after all ;-p

Brooklyn Rider is best known for contemporary music, collaborations, and for playing pieces by group members and other composers in the Brooklyn scene. How does Ludwig Van fit in?

Well, we are a string quartet, and Beethoven wrote 16 of them, all masterpieces, but also he represents the same spirit of breaking down walls that we strive for in all our music-making. As one of the first classical music freelancers, not tied to any court or church, he had to step out and make his way in his own. Of course he had the talent and ability to get a steady job just about anywhere, but he decided to move to Vienna and surround himself with the most creative musical minds of the time.

He drew upon all sorts of musical influences, no matter their status as “high” or “low” art: folk tunes from Germany, Russia, Scotland; the urban music of Roma street performers; he simply refused to create any boundaries for himself- not even his hearing loss could stop him. In that, Beethoven is an inspiration not only for musicians like us who never tire of playing his pieces, but for all of us together on this earth, joined by our shared existence. How does Ludwig Van NOT fit in?

Can you say something about one of the pieces on Saturday’s program and why you are looking forward to playing it?

I am most excited about playing Colin’s piece BTT on the program Saturday. To me it represents exactly what Brooklyn Rider is about: boundary-pushing and forward-looking, but drawing from the past, both classical and non, so it still purports to be part of a tradition. It’s a wild ride that touches on many genres and atmospheres, but it all holds together somehow and at the end of it, you feel as if you’ve been on a journey, which is what I look for when I sit down to listen to a piece.

May 5, 2017

Songwriting’s Roots in Poetry and Prose

GENERALLY, I’m skeptical of the glib and automatic denoting of any intelligent or articulate musician as “a poet.” But the connection between popular song and literature go back, in the Anglo-American tradition, at least as long as The Beatles’ interest in Lewis Carroll and Dylan’s borrowing from Scottish Border ballads.

Of course, at the beginning of the Western tradition, the connection is even stronger: Greek lyric poetry was known that way because of its accompaniment by the lyre.

In any case, with Dylan’s Nobel it seemed the right time to launch a series I’ve been thinking about for a long time. My editor at the Los Angeles Review of Books, a young(ish) native of the Soviet-era Ukraine who loves Russian poetry as well as California freak folk, felt the same way, and offered me a monthly berth. He took the title from a lyric by a late, great literary songwriter named Lou Reed: “All the Poets.”

The initial column launched a few weeks ago with my interview (here) with Stephin Merritt of the Magnetic Fields, the grumpy, inspired singer-songwriter whose work I have followed since the mid-90s. Merritt, always intelligent but sometimes a difficult interview, was quite inspired here I think. (The first of the band’s two nights at UCLA Royce Hall, behind the new LP 50 Song Memoir, was hilarious and moving.)

Please keep your eyes out for more of these: Another, with a songwriter from Britain, is in the works for late May.

April 24, 2017

Bella Gaia at Cal Tech

About a week ago, I saw something called Bella Gaia at Cal Tech’s Beckmann Auditorium. I’m still not sure what it was. (At the very least, this was a film with live dancers and musicians in some places.)

Overall, it struck me as a cross between a ’70s planetarium show, Koyaanisqatsi, and a Thievery Corporation concert.

I’ll very much  look forward to whatever director Kenji Williams comes up with next.

look forward to whatever director Kenji Williams comes up with next.

April 14, 2017

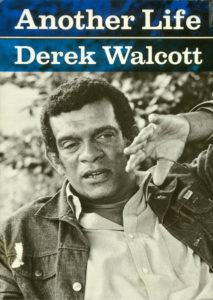

The Late, Great Derek Walcott

Folks, This week CultureCrash guest columnist Lawrence Christon looks at the legacy of the Saint Lucia-born, US-residing poet Derek Walcott, who died March 17. I share Christon’s fondness for DW’s verse, and was pleased enough to meet the poet once or twice at the Eugene O’Neill Theater Inst in CT, which I covered in the mid-’90s.

It’s been nearly a month since Derek Walcott died and I’m still

waiting for a major publication, or even a minor one at this point, to

come out with an authoritative summary of his life and work, the kind

of commentary on his esthetic that puts him to rest with the

illuminating glow reserved for the truly extraordinary.

It looks like it’s going to be a long wait. Except for The New York

Times’ extensive obit and an appreciation by fellow West Indian Hilton

Als in The New Yorker, there’s been virtually nothing, not in places

where you would expect it, like Harper’s, The Atlantic or The Paris

review. Not in the once-literary Esquire, nor the culturally emaciated

Los Angeles Times, which ran an amateur freelancer’s marginally

embarrassing essay and shunted Walcott’s actual obit over to the

Associated Press, which could not resist mentioning sexual harassment

charges. (The half-mad titular poet in Saul Bellow’s 1975 “Humboldt’s

Gift” protested, “I have a thick dick!” as a matter of pride; and as

adventurers of the flesh, e.e. cummings and Dylan Thomas would not

have made the cut in today’s flinty literary scene. How times have

changed.)

Need we be reminded that Walcott, a 1992 Nobel Prize-winner, was one

of the greatest English-speaking poets of the past 70 years, with a

brilliant gift for putting us in an exact setting and extending that

moment, that immediate blend of sight and smell and sound, into

deepening metaphors that reached into history, place, art, political

conditions, memory, emotion, and the ongoing dialogue between the

recurrent and the fleeting, all with a language that, as with the

greats, offered a sensual satisfaction of its own?

Robert Graves, no slouch himself, observed: “Walcott handles English

with a closer understanding of its inner magic than most—if not any—of

his English-born contemporaries.” Not even one of Walcott’s peers, of

whom there are precious few, have stepped up to pay homage as Auden

mourned Yeats: “He disappeared in the dead of winter:/The brooks were

frozen, the airports almost deserted,/And snow disfigured the public

statues;/ The mercury sank in the mouth of the dying day….”

The New York Review of Books ran an excellent piece on April 6, but it

seemed more a happy accident inasmuch as it dealt with Walcott’s

collaboration with painter Peter Doig on a book called “Morning,

Paramin,” and otherwise made no mention of Walcott’s passing. (Though,

to be fair, both the NYRB and Paris Review went to press before they

could mention his death.) Walcott was an expert watercolorist, incidentally,

which helped vivify his poetry’s address to the mind’s eye.

So what gives? Why the shameful, or shameless, neglect? The truth is

that this ignorant indifference extends to the genre itself.

I spent a couple of days reading through numerous poetry websites,

many of them connected with prestigious foundations and publications,

and was dismayed to see that, with a few crossover exceptions, their

listings of our top 20 or more contemporary poets contained completely

different names, as if no one knew or even heard of anyone else. I’m

not speaking of familiars like W.S Merwin, Billy Collins or Kay

Ryan — they’re not even mentioned. If poetry editors can’t agree on a

list, how are us civilians expected to keep up? And what does this say

about consensus figures in the English-speaking landscape?

Poetry, in America at least, has been taking a beating for more than a

half-century, for reasons that overlap. The ’50s was the last decade in

which youthful rebellion expressed itself in literature, as in the

work of the Beats and the epic cry of Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl,” which

came out in 1955, (when T.S. Eliot was still a literary demi-god). In

the Dionysian ‘60s, the shift in cultural energy turned to rock music.

In the Reagan ‘80s, the warring politicization of the arts, both on

the right and left, exacted its price on the hands-off autonomy of

art. By the aught years, movies, TV, cable and the proliferation of

cell phones and “visuals” had all but crowded out the power of the

word as a mediator of experience, leaving us in an aural landscape of

newspeak, psychobabble, academic jargon and a thin slop of everyday

speech.

As much as anything, the abandonment of the western canon has

encouraged a majority of artists, including poets, to make art as if

the shock of the new were the only hit worth taking. Walcott, in

searching for his own identity as a poet, contradicted this willful

amnesia early on. In “Origins,” he writes:

The flowering breaker detonates its surf.

White bees hiss in the coral skull.

Nameless I came among olives and algae,

Foetus of plankton, I remember nothing.

Clouds, log of Colon,

I learnt your annals of ocean,

Of Hector, bridler of horses,

Achilles, Aeneas, Ulysses,

But ‘Of that fine race of people which came off the mainland

To greet Christobal as he rounded Icacos,’

Blank pages turn in the wind.

Walcott spent a lifetime traveling and educating himself in history

and art, writing through the split vision of race, the self and the

world, the colonial place in civilization and vice-versa, shadow and

light (as in the shade that rested between Christ and the cross). He

worked hard at cultivating an erudition that informed his work without

burdening it. The classics enriched his poems and painting (he was

less successful as a playwright). He had a sharp eye for exploitation

and ruin, but he gave no sense of the tradition of Homer, Shakespeare,

Cezanne, Durer, and Pietro della Francesca, etc., as a progression of

Western imperial decadence. He appreciated the best among his

contemporaries, like Hart Crane, Robert Lowell and Elizabeth Bishop,

in friendship and critical appraisal.

The best summary of Walcott came from his late friend, the poet Joseph

Brodsky (also a Nobel prize-winner) who, in a lengthy 2010 piece in

TNYRB, wondered about

…the unwillingness of the critical profession

to admit that the great poet of the English language is a black man.”

Brodsky writes, “For thirty years his throbbing and relentless lines

have kept arriving on the English language like tidal waves,

coagulating into an archipelago of poems without which the map of

contemporary literature would be like wallpaper. He gives us more than

himself or a ‘world’; he gives us a sense of infinity embodied in the

language as well as in the ocean, which is always present in his

poems: as their background and foreground, as their subject, or as

their meter.

Walcott’s last lines, echoing “Origins,” observe the mountains and sea

of his native St. Lucia, and the cloud that “…slowly covers the page

and it goes/white again and the book comes to a close.”

He’s describing his own end, of course, but you can’t help but feel a

great beautiful book has closed on us as well.

Scott Timberg's Blog

- Scott Timberg's profile

- 7 followers