Scott Timberg's Blog, page 11

January 23, 2017

Pres Obama’s cultural policy

LIKE a lot of Americans, I’m sorry to see President Obama go. But in at least two areas, he was a real disappointment. One was his gutless response — or lack of response — to the housing crisis, which involved mostly looking the other way and proposing toothless acronyms while banks crushed homeowners struggling with the Great Recession.

His second great failure was his cultural policy, which remained mostly a missed opportunity. Obama and Michelle did make a highly publicized visit to Broadway to see a show, and the playlists he released were smart and wide-ranging. But he was hardly a JFK or even (yikes) a Nixon on this count.

This story gets at what I mean.

January 21, 2017

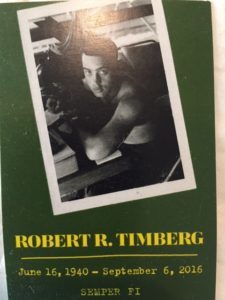

Reflections on a Half Century

His mother was a model. He was a 26-year-old officer driving around the jungle, giving bonus pay to his fellow Marines. Fifty years ago this week, the vehicle he was in rolled over a North Vietnamese land mine. His life would changed radically.

And today, everything my father fought and nearly died for was assaulted by a scheming narcissist.

January 18, 2017

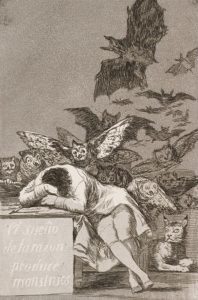

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters

ONE of my favorite writers in any genre is the USC humanities professor Leo Braudy, justly celebrated for his Frenzy of Renown, a history of fame going back to Alexander the Great. Braudy writes widely on literature, film, ancient civilizations. the question of America, the overlap of culture and politics, and all kinds of subjects that interest me. He’s insightful, sometimes inspired, and always accessible to the educated non-specialists. (I wish there were more scholarly writers like him.)

Braudy’s latest book is “Haunted: On Ghosts, Witches, Vampires, Zombies, and Other Monsters of the Natural and Supernatural Worlds.” (The book is on Yale University Press, the publisher of Culture Crash, but I was on record as a fan of Braudy’s before he had the good sense to move to Yale.) In any case, the book is a blast.

What follows is my correspondence with Braudy. Hope readers enjoy it as much as I did.

Q: You’ve tracked the way fear has exerted itself in Western culture from early-modern to contemporary times. But to what extend are fear and terror — and their associated gallery of imagery and narrative — simply a part of human nature? That is, would any culture or any historical (or even pre-historical) time period work the same way, but perhaps with the details changed?

A: Human nature to me is a very ambiguous and frequently changing concept. Yes, we have desires, hopes, and fears that seem innate and timeless, but their expression is shaped by the specific personal and public contexts in which they appear, and so they mutate or at least change in relation to our own biographies and what’s happening around us. By the same token, the expressions of the fears and anxieties of large groups of people are conditioned by the historical times in which they emerge. “Human nature” may be the bricks and mortar, but many different buildings can be created from them. Such a perspective would work in any time period, but the change in the details is exactly the crucial distinction between one era and another. Early on in my literary work I became fascinated by the way emotion tended to be written out of literary and cultural analysis in favor of seemingly more tangible factors like politics and economics and, in the discussion of literature especially, the dictionary meaning of the words in the text. To a certain extent this is the result of the influence of the Marxist distinction between base and superstructure: art in this view is “soft” superstructure, while the “hard” facts of economics are the base and therefore the reality of what is happening or has happened. So the critic uses political and economic facts to “explain” artistic production. I would reverse that formulation, or at least readjust the balance: art embodies a history of emotion that helps determine how history’s otherwise external facts develop and how people respond to them.

The years around the French Revolution and the Industrial Revolution — both late 18th century but bleeding into the “long 19th” — produced a large and acute batch of fearful imagery. Why was that, and what kind of literary/ cultural/ psychic terror did it produce?

The great battle cry of the American and French revolutions was the future: throw off the inherited structures of past tyranny like monarchy and religion and move triumphantly forward to liberty. The Industrial Revolution similarly promised a new sense of individual and collective will; human intelligence would master the repressions of environment and nature: turning rivers into power, replacing individual craftsmen and their unique products with a production line of interchangeable parts that could afford similar quality at much lower cost, etc. So far, so good. But in the process, as in all revolutions, whether technological, economic, or political, the broad brush of change swept aside things of value as well. The rise during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries of gothic literature, painting, and even music that drew upon the supernatural expressed something of the fears of what change had brought, the dark recesses from which monsters emerged.

It sorta makes sense now that Poe invented not only the horror story as well as the detective tale, eh? How are they related?

Some reviewers of Haunted have been puzzled by my inclusion of a chapter on the detective in what is otherwise a book about horror, but to me the monster and the detective are opposite sides of the same coin: the monster the figure of disorder and fear, the detective the seeker for order and reason. That Poe wrote masterpieces in both forms shows their basic dependence on one another, their Jekyll and Hyde-like interaction. Poe didn’t invent the horror story, but his poems, short stories, and longer works arrive in the 1830s and 1840s at a crucial moment. The literature of fear had become a widespread and recognizable genre in England, Europe, and America. To that literature he contributed an intensified version of the first-person narrator (in, say, “Fall of the House of Usher” and “William Wilson”) as well as a self-conscious sense of the supernatural mystery that cannot finally be solved that had a lasting influence on both American and (through Baudelaire) French literature. At the same time the growth of police forces and the arrival of an embryonic crime-solving force in places like the French Sûreté and Scotland Yard offered the possibility that in fact crimes could be solved. Poe’s detective C. Auguste Dupin is, however, not a member of any official police force. As an outsider he has the detachment to mingle reason with a powerful instinct in what Poe called ratiocination, along with a compatibility with the criminal mind, in order to solve his cases. In Poe’s work this combat between the empirical idea that facts will be decisive and the supernatural idea that there are things in the universe we can never know fully is a primary engine of his creativity.

In your book’s opening pages you describe your ambition to write the history of an emotion. Is that difficult to do, intellectually? And is that unconventional way of looking at culture a difficult fit in contemporary academia, including academic presses? Would it be possible without Freud?

I don’t count Freud as a particularly good guide to the understanding of how emotion might have a history, since his theory of the relation of the self to society depends so much on the repression of emotion and inner conflict. In many ways I prefer the point of view of Carl Jung, who explored the way in which the repression of emotion created the monstrous inner self, which without that repression could become vital and creative. This isn’t quite the 60s ‘do your own thing’ or ‘let it all hang out,’ but a recognition that consciousness and rationality have to come to terms with the powers of the unconscious and the emotions. (I’ll leave aside for now Jung’s idea of the collective unconscious, which is a whole other issue.) There’s a great scene in Rouben Mamoulian’s version of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde in which Hyde is pleading with Lanyon to give him the chemicals he needs to turn back into Jekyll. Between them on the wall is a large portrait of Queen Victoria. In other words, if Jekyll hadn’t lived in that era or if he hadn’t taken its repressions so to heart, would Hyde have existed?

How have some images from literature and art — originating perhaps as far back as the Reformation — transmuted themselves into recent popular culture?

Even before the Reformation, religious imagery struggled to present images of both the divine and the diabolical. The earliest images of Jesus, say, were of a young man with curly hair and a lamb over his shoulders—the Good Shepherd of the Gospels as well as a figure out of Greek and Roman pastoral. Satan as well changed his image from being a member of God’s court (in the Book of Job) to the competitor with Jesus for God’s favor to the embodiment of the principle of evil. In religiously oriented horror films that literary and visual history helps create the figures we see, with of course some allowance for the nuances of contemporary creativity on the part of the production designer and the makeup person. The point to remember is that visual representation has its own demands, which may be different from those of literary description. Dracula on film looks little like Dracula in the novel. Sherlock Holmes in the stories and novels never wore a deerstalker hat or smoked a Meerschaum pipe.

Your writing — like Morris Dickstein’s and a few others — reminds me a bit of the generation of Leslie Fiedler and Irving Howe. Do you feel an affinity with that crew?

Morris was a year ahead of me in graduate school at Yale. Yale at that time was not yet the home of Paul De Man’s deconstruction or Harold Bloom’s Romanticism. It was still under the aegis of the New Critics like Cleanth Brooks and William Wimsatt, but I was more intrigued by teachers like Martin Price who were trying to see the main currents of an entire period. Fielder, who was then at SUNY-Buffalo, would be in the same category, especially with his willingness to see popular culture as significant as high culture (such outmoded terms) in understanding an era. At the time too I was more interested in distinguishing what I was doing from what others were doing, but in the long view there are definitively affinities, especially in the willingness to write for magazines and newspapers, otherwise condemned as “belletristic” by the more academically oriented. In high school my critical heroes had been writers like George Orwell and Edmund Wilson, along with the early film critics like Andrew Sarris, Pauline Kael, and Dwight Macdonald. I went to the movies all the time, so any exclusive focus on literature alone was out of the question. Later I took a job at Columbia, where Morris was also on the faculty. Lionel Trilling’s office was across the hall from mine, Edward Said’s down the hall, and the whole Columbia English faculty, as well as the context of New York City, strengthened my sense of the social role of art, the need to take not only the world in which it appeared but also its audience into consideration. Morris and I later co-edited a collection of essays on great film directors for Oxford. His first book, though, was on Keats, while mine was on the relation of history-writing to novels in the eighteenth century. Make of that what you will.

Thank you for being part of the CultureCrash

January 17, 2017

“Best Books of the Last 20 Years,” and the Canon

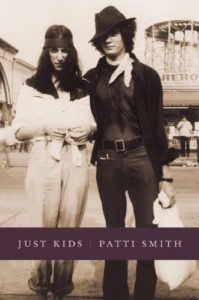

It sounds like a great idea, or at least a revealing one: Assemble a list of the most important books of the last two decades, in any genre, from poetry to the novel. Find accomplished writers in a variety or genres — Rebecca Solnit, Jonathan Lethem, Roxane Gay, Ann Padgett, Patti Smith, and so on — and ask them for their favorites since 1997.

“The end of December is a time when we are bombarded with end-of-year lists—so much so that they start to blur together,” Michele Filgate wrote in a recent post on LitHub. “But what about the books that stay with us for years?”

The list of 128 volumes that emerged from this is intriguing, at least, and makes no pretension to bring scientific, complete, objective, or whatever. It’s just a few dozen smart and famous people picking their favorite books. The big winners, it turns out, are David Foster Wallace’s “Infinite Jest,” Edward P. Jones’ “The Known World,” and Cormac McCarthy’s “The Road,” all tied for first.

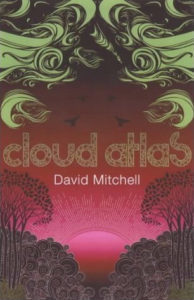

But here’s what’s most fascinating and a bit troubling: This trio of celebrated novels — the ultimate victors in this poll — got only three votes each. And only a handful of other books got more than one vote. (David Mitchell’s “Cloud Atlas,” “Americanah” by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Elena Ferrante’s Naples quartet, Bolano’s “2666,” and eight others got a whopping two votes apiece.)

So pretty much what we have here is 29 really smart writers — Rick Moody, Maggie Nelson, Geoff Dyer, and other luminaries — speaking mostly to themselves.

Of course, it’s not really the fault of the assembled scribes, most of whom would be in my council of sages and some of whom are acquaintances of mine. And while some would argue that literature and books of history and poetry are not well served by the kind of list-making associated with “Late Night With David Letterman” and “High Fidelity,” I’m not among them: We make all sorts of lists and rankings in our heads, consciously, or unconsciously, all the time. Anyone who has edited an anthology, designed a college or high school course, chosen what to read this week for fun, what to give a friend for Christmas, or what to throw in the beach bag for summer vacation has been through this kind of thing in some form. As the Mekons song says, “ We make big decisions every day.”

But part of what we see on this list, I think, is the result of decades of running do wn the canon. Not just a rigid canon monopolized by “dead white European males,” but the idea of a canon itself.

wn the canon. Not just a rigid canon monopolized by “dead white European males,” but the idea of a canon itself.

We live in a period where the very notion of consensus, at least in the world of culture and journalism (remember Edward S. Herman’s and Noam Chomsky’s “Manufacturing Consent”?) connotes a kind of middlebrow plot cooked up by Judy Miller. So it should not surprise us that none of these esteemed American writers — most of whom belong to one of the two PEN groups and go to the same Brooklyn or Echo Park parties, mostly share a left-liberal politics, and often clink glasses at literary fairs and spend a weekend each spring at the Los Angeles Times Book Festival, and so on — can’t really agree on the best, most enduring work in their own field.

The polled writers, for the most part, came of age after the great canon revolts at places like Brown (where the New Curriculum of 1969 made it possible so that “every student might study what he chose, all that he chose, and nothing but what he chose”), Wesleyan, and Stanford (where the cry ““Hey, hey, ho, ho, Western culture’s got to go!” became a great gift to reactionary fools like William Bennett.) They have been taught, in some cases, that the notion of a canon or core curriculum itself — even if it’s liberalized with women and writers and color and so on — is by nature phallic or oppressive or whatever.

In an attempt to emulate the LitHub list, this Stanford-born, Wesleyan-educated reader and writer assembled a hasty kitchen cabinet which included some critic friends, my (Brown-schooled) college mentor, my librarian wife, California’s poet laureate, the best-read indie rocker I know, and, you know, a young guy I met at the coffee shop who was wearing a T-shirt inspired by David Foster Wallace. Ten smart people, at the very least, from three generations and two coasts.

My poll actually came out almost as horizontal as LitHub’s: Of a few dozen books nominated by 10 people, only three got more than two votes. Patt Smith’s “Just Kids” ti ed “Infinite Jest” and “Cloud Atlas”; each got four votes. (My judges were heavy on Gen X and music-lovers.)

ed “Infinite Jest” and “Cloud Atlas”; each got four votes. (My judges were heavy on Gen X and music-lovers.)

A few tomes did better here than on LitHub: Junot Diaz’s “The Brief, Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao,” Joan Didion’s “Where I was From,” Alex Ross’s “The Rest is Noise,” all got multiple votes. But for the most part we had trouble agreeing in anything, either.

Canons, of course, consolidate over time: We could certainly come up with a firmer, more stable list of the best, say, albums from the ‘60s, or movies from the ‘70s, or alt-rock bands from the ‘80s than we could with their 21st century equivalents. (Even if the “Forever Changes” fans tossed grenades at the “Pet Sounds” army, the “Godfather II” enthusiasts made war on the “Chinatown” crowd, cardigan-clad followers of the Smiths arm-wrestled the R.E.M. brigade, and so on.)

The LitHub list certainly has a lot of very strong and wide-ranging work. Is it better to have 128 books on that list, with only three volumes getting more than two votes, than a list of half as many, with more clustering over a few hits? (In other words, a less horizontal and more vertical list.)

Maybe there’s a way of looking at the LitHub list’s flatness as a triumph of diversity. But to me, it says that whatever good things arrived with the coming of multiculturalism, the fragmenting of consensus delivered by the Internet, and the revolts against required readings and cultural gatekeepers and musty old canons and everything else, one of the things that’s ocurred is the loss of a common language.

Without a lingua franca, I’m wishing us all luck in the coming years: We may need it.

January 9, 2017

Jazz and “La La Land”

FOR weeks now I’ve been meaning to write about the poorly named film La La Land, which has drawn acclaim but also divided audiences, and drawn a decidedly split response within the jazz world.

Hoping to get to that today. I really loved the movie, for what it’s worth.

A lot of people I trust disliked or hated it.

But starting today it becomes very cool/ intellectual/ contrarian to say, “I always hated La La Land.”

A belated happy new year to readers of CultureCrash.

December 31, 2016

Music To Say Goodbye To 2016 To

WELL, one of the worst years in recorded history is over. Every morning, as my consciousness returns, I am reminded that Leonard Cohen, Bowie, George Martin, and my dad are dead and that a nasty, incurious bully is on the verge of becoming president.

My employer, Salon, has posted a piece with a mix of happy and sad songs with which to end this year and enter the next one with a “New Year’s Eve Catharsis Party.” It leads with three picks by me — songs by Fairport Convention (Richard Thompson’s old ’60s band), Belle & Sebastian, and Prince. (The piece also includes a Spotify playlist.)

For space reasons, one of my contributions ended up on the cutting room floor. Here it is.

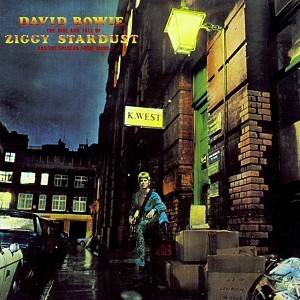

“Five Years,“ David Bowie: This is the opening song of the best album of the musician who may have been the artist of the 1970s. It’s a post-apocalyptic lament with the same blend of bleak romantic humanism as the film “Children of Men.” With kickass guitars. If this song concludes your New Years party, is is likely to have been a pretty morbid affair. If it opens it, though, the gathering can go in as many directions as the late chameleon’s protean career. RIP David Bowie.

Wishing all CultureCrash readers a happy end to this Annus horribilis, and a happy 2017.

Wishing all CultureCrash readers a happy end to this Annus horribilis, and a happy 2017.

— Scott

December 16, 2016

On Stage with the Marx Bros

ONE of the glories of American culture is the cinematic ensemble known as the Marx Brothers. But before Chico, Zeppo, Harpo, and Groucho became anarchic movie stars in film like “A Day at the Races” and “Duck Soup,” they were an anarchic vaudeville troupe that traveled the nation. And they performed and socialized with my grandfather, a Tin Pan Alley songwriter, and his siblings, though I have never quite been clear on the details.

I corrsponded with Robert S. Bader, the author of a new book, Four of the Three Musketeers: The Marx Brothers on Stage, on Northwestern University Press.

I’ll try to fill this in a bit as I get time.

The MarxBros are best known for movies like Duck Soup and A Night at the Opera. What made you want to look into the lesser-known chapter of their vaudeville years?

The MarxBros are best known for movies like Duck Soup and A Night at the Opera. What made you want to look into the lesser-known chapter of their vaudeville years?

I discovered the Marx Brothers when I was around eight years old, and a few years later when I was starting to learn more about them it occurred to me that they were not exactly kids when they made their first movies. I was just curious about what they were doing before the movies and this led me to spend several years researching vaudeville. Pretty soon I was not just researching the Marx Brothers in vaudeville, but the entirety of vaudeville.

How long and hard did they work the vaudeville circuits? How wide-ranging was it geographically?

Groucho started a few months before his fifteenth birthday in the summer of 1905. Gummo joined the act in 1907 and Harpo come on board in 1908. Chico was working as a song plugger for a few years before he got started in vaudeville in 1911. He joined his brothers in 1912 and the Four Marx Brothers spent the next ten years touring vaudeville in just about every corner of the United States and Canada. I was able to document them performing in at least forty states – and there were only forty-five states when they started in vaudeville. They spent a lot of time in small towns, living in fairly squalid conditions. The railroad travel was pretty rough for them with a lot of connections in the middle of the night in remote places. It was a pretty tough life.

Were the Marxes sort of superstars of that world — treated like kings wherever they went — or were they in some ways typical of it

They paid their dues in small-time vaudeville for several years. They built up a good reputation but it took some time before they were big stars. Things got better for them in 1915 when they made it to the big-time circuits. But vaudeville performers were considered social pariahs in most of the country a hundred years ago. They were not treated like kings at all. Once they moved into the world of legitimate theatre in 1923 they were more respectable. But in small towns across the country, people did not want their daughters to get anywhere near a vaudevillian. The Marx Brothers were probably among the most objectionable acts that could possibly visit a small town as far as the father of a young girl was concerned.

What kind of subculture did they come out of in New York? Tell us a bit how that relates to their gift for ethnic mimicry re Irish, Italians, etc.

They grew up in Yorkville, a largely immigrant community on New York City’s upper east side. Their mother Minnie came with her family from Dornum, Prussia and their father Sam came alone from Alsace, France. They began their lives in New York on the lower east side and moved to Yorkville in 1895. The neighborhood had been predominantly Irish before a large influx of German immigrants moved there around the turn of the century. Th ere were also a lot of Italians. There was a fair amount of nti-Semitism among the immigrants of New York City at the time, so as German Jews, the Marx boys were part of an unpopular minority. They learned to fake accents to help them get through the Irish parts of the neighborhood without getting beaten up.

ere were also a lot of Italians. There was a fair amount of nti-Semitism among the immigrants of New York City at the time, so as German Jews, the Marx boys were part of an unpopular minority. They learned to fake accents to help them get through the Irish parts of the neighborhood without getting beaten up.

What surprised you the most in your research/reporting, either specifically or generally?

There were several things. The closeness of the family – and not just the immediate family – was a revelation. Their uncles, aunts and cousins were deeply involved in the Marx Brothers’ early lives and even in their early days in show business. This was actually typical of immigrant life in New York during that period, but I was able to uncover a lot of interesting details about the extended family.

One example that may resonate for knowledgeable Marx fans involves their uncle Julius, for whom Groucho said he was named. Uncle Julius was married to Minnie’s sister Hannah. But they got married when Groucho was fifteen months old. The explanation is that Aunt Hannah married her first cousin and that Groucho was named for this man before he was his uncle. He was named for his mother’s cousin, who later became his uncle.

What role did Los Angeles play in the Marx Bros’ lives, especially their vaudeville career? I think of them as a bunch of New York boys, but at least one of them is buried at Forest Lawn.

They all eventually settled in southern California in the 1930s and lived there for the rest of their lives. But in their early vaudeville days the west coast was not really a consideration. They first played Los Angeles in 1911 on tour of the Pantages circuit, which they played again in 1913. Once they moved up the hierarchy a bit they were regulars on the Orpheum circuit and made regular visits to Los Angeles beginning in 1915. But when they started out in vaudeville Los Angeles might as well have been China. They were mostly working in the northeast and south until that first Pantages tour.

Indulge my family pride for a moment. My grandfather Sammy Timberg used to tell fond stories of traveling with the brothers and rooming with Groucho. Did you find descriptions of him or his siblings Herman and Hattie?

The Marx Brothers worked with the Timbergs in 1921. It was a pretty brief association. Herman Timberg, who had been a big star in vaudeville as a child, became a producer and wrote a new show for them called On the Mezzanine Floor, which was also called On the Balcony. It opened in February 1921. The Marx Brothers purchased the show from Timberg in October and they continued in it for another year.

Herman produced this show with boxer Benny Leonard as the major investor. Leonard was dating Herman’s sister, Hattie. Her stage name was Hattie Darling and she was the leading lady in the show until she was replaced when the Marxes bought out Herman Timberg.

Herman’s brother Sammy was a composer and musical director and he worked on the show as well. If Sammy and Groucho roomed together on the road, it would have been after Groucho’s wife Ruth left the company to have their first child. Arthur was born in July of 1921. The show rarely left New York while the Timbergs were involved, but there were a few road dates after Ruth probably off the tour.

I did find documentation for a performance featuring Herman and Sammy Timberg and the Four Marx Brothers. There was a benefit for the Sidney Ascher Camp at the Hotel Pennsylvania in New York on March 20, 1921 while On the Mezzanine Floor was playing at the Palace Theatre. The principal acts on the bill were the Four Marx Brothers, Benny Leonard, Eddie Cantor and Herman and Sammy Timberg.

In one of those odd coincidences that turn up in show business history, Hattie Darling’s replacement in On the Mezzanine Floor was Helen Schroeder, who later gained fame under her married name Helen Kane with her recording of “I Wanna Be Loved By You.” She became the inspiration for Max Fleischer’s popular cartoon character Betty Boop, and of course you know, Sammy Timberg became quite a success as the musical director of the Fleischer cartoons.

December 4, 2016

Octavia Butler’s Los Angeles

THE posthumous rise of the science-fiction writer Octavia Butler, who died in 2006 and spent most of her life in and around Pasadena, CA, has been fascinating to watch. I’ve been interested in Butler since I moved out here and began to hear of her work, in the late ’90s, and love one of her story collections. But I don’t know her life of output in great detail.

So I’m looking forward to a tour of her life in Southern California today, put on by the LA arts group Clockshop. All the action — there have been panels and numerous events, some involving great LA scribe Lynell George — is driven by the acquisition of Butler’s papers by the Huntington Library.

Butler’s Pasadena was very different than that Rose Bowl/ Cal Tech/ Protestant gentry side of the city that’s generally better known; she came from sternly religious Southern blacks, and started writing as a kid while her mother cleaned houses for wealthy white people. Butler, as an adult, took menial jobs so she could keep her mind free for writing and thinking.

In any case, will report back; please watch this space.

November 28, 2016

Remembering an Old Friend

WHEN I was in high school, I had a slightly older friend who was eccentric, brilliant, and obscure. He had a minor speech impediment, so I couldn’t always tell what he was saying, but whenever I could make it out, it was fascinating and perceptive. I met some very cool and smart people through him.

A few years after I left for college, I heard he got heavily into drugs and petty thievery. We lost touch for a few years. But then a bit later, he went to law school, cleaned up his act, and became really beloved and successful. Some of his old edge was gone, and I missed that side of him. But I was grudgingly glad he was happy.

Still, we drifted apart significantly, and were each on our own respective trip for two decades or more. We each fell in and out of love with various other passions. But we saw each other at a 25th reunion, and weirdly, I was reminded how great he was. And how that dude who went straight was a lot more substantial than I’d thought at the time. We reconnected in a big way and I was reminded of how much I’d missed him.

Oh hold on — that isn’t a high school friend, that’s R.E.M. 1991 album Out of Time. (The drugs/ thievery was a not-terribly-accurate reference to my least favorite of their records, Green.)

The acoustic stuff on Out of Time‘s second disc will remind you why you fell in love with music in the first place. And most of the rest sounds so resonant. End of metaphor. But get the anniversary reissue; it’s quite lovely.

November 25, 2016

Reasons to Be Thankful: Rock n roll

HERE are my 25 favorite rock records. Trying to focus on proper studio albums, so live concerts and anthologies strongly discouraged. No jazz, classical music, pure country, electronica, acoustic blues, or hip hop. (I’ll make an exception for R&B that hews closely to the rock tradition.)

These are albums that have some personal meaning and also have a place in music history. Preference given to bands and albums that were seminal rather than inheritors, so “Marquee Moon” over “Perfect From Now On.” And this list is chronological.

Caveat: Next week the list could be a bit different.

Here they are:

Elvis Presley, The Sun Sessions (1954/’55; 1976)

James Brown, Live at the Apollo, (1963)

The Beatles, Rubber Soul (US version) (1965)

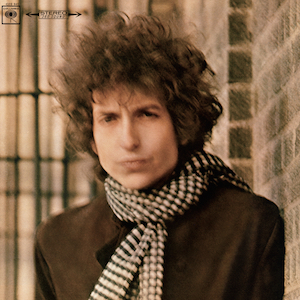

Bob Dylan, Highway 61 Revisited (1965)

The Beatles, Revolver (UK version) (1966)

Bob Dylan, Blonde on Blonde (1966)

Jimi Hendrix, Axis: Bold As Love (1967)

Van Morrison, Astral Weeks (1968)

The Byrds, Sweetheart of the Rodeo (1968)

The Velvet Underground, The Velvet Underground (1969)

–

The Rolling Stones, Sticky Fingers (1971)

David Bowie, Ziggy Stardust (1972)

Richard & Linda Thompson, I Want To See The Bright Lights Tonight (1974)

Neil Young, Zuma (1975)

The Jam, Setting Sons (1979)

Elvis Costello, Armed Forces (1979)

The Clash, London Calling (1979/ ’80)

The Clash, London Calling (1979/ ’80)

Bruce Springsteen, The River (1980)

R.E.M., Fables of the Reconstruction (1985)

The Smiths, The Queen is Dead (1986)

–

Yo La Tengo, Fakebook (1980)

Liz Phair, Exile in Guyville (1993)

Pavement, Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain (1994)

Belle & Sebastian, The Boy With The Arab Strap (1998)

Wilco, Yankee Hotel Foxtrot (2001)

Runners up: Nick Drake, “Five Leaves Left,” Marvin Gaye, “Let’s Get It On,” My Bloody Valentine, “Loveless,” “Lucinda Williams,” Built to Spill, “Perfect From Now On”

Of course, when you make lists like this, it’s impossible not to feel regret at the lack of space for great work (no Kinks, no Beach Boys, no Ray Charles, no Minutemen, no Sonic Youth, no Elliott Smith, no Built to Spill, no “Being There” or “Basement Tapes,” etc.)

So dear readers, please send me your own list — a top 10 or more, using the same ground rules I did — and I will post the best/ most persuasive one on CultureCrash.

Scott Timberg's Blog

- Scott Timberg's profile

- 7 followers