Scott Timberg's Blog, page 35

June 9, 2014

Lonnie Johnson’s “St. Louis Blues”

WHAT’s the most influential song in history? The Atlantic Monthly recently asked Ted Gioia for his answer, and he suggested this W.C. Handy classic, for all the blues songs it engendered, its enduring melody, and partly for its “Spanish tinge.”

I don’t think Ted, a longtime friend of CultureCrash, was thinking of this version; it’s not especially well known. But guitarist Lonnie Johnson, who straddled blues and jazz and may have invented the guitar solo, is one of my favorite interpreters. His version, recorded during his comeback during the ’60s folk-blues revival, starts in the song’s middle section, and he plays up its Latin quality.

I don’t think Ted, a longtime friend of CultureCrash, was thinking of this version; it’s not especially well known. But guitarist Lonnie Johnson, who straddled blues and jazz and may have invented the guitar solo, is one of my favorite interpreters. His version, recorded during his comeback during the ’60s folk-blues revival, starts in the song’s middle section, and he plays up its Latin quality.

Anyway, here it is. I’ll try to write more fully about Johnson another time. He deserves to be way better known.

June 6, 2014

Celebrating Route 66

Collection of Steve Rider

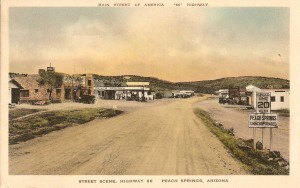

WELL, that sure was an unexpected pleasure. I thought I knew a bit about Route 66, but there are apparently dimensions to the legendary historic highway I’d not considered. The press preview I walked out of this morning left me thinking that this medium-sized exhibit at the Autry was the best social-history show I’ve seen in many moons. For enthusiasts of California history, it’s simply essential. (The show opens on Sunday June 8.)

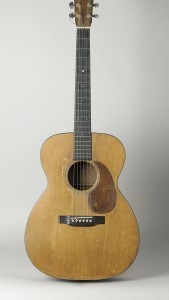

The show is structured chronologically, mostly, but tells a larger story of the planning, growth, packaging, decline and revival of the 2,400-mile long thoroughfare. Dating back to the age of railroads, to the turns of the century “Good Roads” movement which saw the spread of bicycles, and an enlarged building role for the federal government (roads have previously often been privately established), Route 66 was initiated in 1926. Before long it was known as America’s Main Street. The Depression came to associate it with the down-and-out — there’s some attention to the books of Steinbeck, the photography of Dorothea Lange, and the music of Woody Guthrie, whose battered Martin guitar is part of the exhibit. The New Deal helped it get paved.

Postwar car culture, motels, neon advertising, and Burma-Shave ads transformed it. Dozens of “sundown towns” in which black people were not welcome after dark means a color line ran right through the middle of the highway. The Beat generation loved Route 66, and Kerouac’s original scroll for On the Road, which has never been shown in Los Angeles, is part of the show. (Curator Jeffrey Richardson said that for all his pharmaceutical enthusiasms, Keruoac write it on nothing stronger than coffee. Richardson, who led the tour with great energy, seemed quite familiar with caffeine, so I’m willing to take him at his word.)

Oklahoma’s Ed Ruscha, who seems himself like a figure from Route 66 myth, photographed its gas stations, which were revisited by a contemporary photographer; both are part of the show.

But just as the road was becoming a tourist draw and a legend of Americana, the interstate highway system, destinations like Disney World and Vegas, cheap air travel, and a diminishing sense of place conspired to undercut it. The myth tarnished; the highway began to literally come apart, as its asphalt crumbled. Route 66 ceased to be an official national highway. But for reasons I had not considered, it began to come back.

But just as the road was becoming a tourist draw and a legend of Americana, the interstate highway system, destinations like Disney World and Vegas, cheap air travel, and a diminishing sense of place conspired to undercut it. The myth tarnished; the highway began to literally come apart, as its asphalt crumbled. Route 66 ceased to be an official national highway. But for reasons I had not considered, it began to come back.

Guthrie’s Martin Courtesy EMP Museum

You probably knew some of this stuff, but the details and artifacts are fascinating, especially the way it fits into the larger contours of 20th century history. I could go on, about oil boomtowns and Roy Rogers and Jackson Pollock and the LAPD’s “bum blockade,” but I’ll stop here.

Even if you’re sick to death of the Bobby Troup song (and like the Depeche Mode cover even less), this is one to see.

The Dead End of Rock Touring

JUST go on the road! Musicians who’ve seen their earnings from recorded music collapse should just tour more often, digital utopians tell them. But a new report shows that even with ticket prices getting higher, a 60 percent growth in touring revenues since 2000, and a supposed recovery from the depths of the recession, the musicians are making less money touring than they used to. Here’s the Music Industry Blog:

The live music value chain is an incredibly complex one with multiple stakeholders taking their share (ticketing, secondary ticketing, venues, booking agents, promoters, tax, expenses etc.). The share of live revenue that artists make from live has declined every year since 2000. The impact on the total m

arket is that total artist income (i.e. from all revenue sources) has declined every year too since 2009.

This comes from a report about music’s growing superstar economy: Both the Internet and the music industry serve as the cutting edges of inequality. I’ll keep tracking this as best I can.

June 5, 2014

Songwriters Struggle in the Digital Age

TWO more musicians have expressed their frustrations with the post-label era of music distribution, which many technologists tell us is the best of all possible worlds.

The first is the estimable eclecticist Van Dyke Parks, who writes in the Daily Beast about “How Songwriters Are Getting Screwed in the Digital Age.” (I know Van Dyke well enough to know that that was not his headline.) He’s writing specifically about the low royalty rates musicians (especially songwriters) make from Spotify and the like, but sees the crisis as part of a larger battle.

There’s less support for all the arts today, and the blade gets duller with every cut in arts funding. It degrades dance, opera, even academia and, significantly, the art of journalism. As a result, in the U.S., public opinion suffers from what we call “infotainment.” That’s a genre of media news that is not informing, entertaining, or remedial. And it’s a direct result of a vacuum of patronage (and by patronage, I don’t mean just Medici-style sponsorship but the willingness of all arts consumers to pay for what they listen to, read, and watch, and for the industry to fairly recompense creators).

The second piece is by producer T-Bone Burnett, known for his work in television (Nashville) and film (the Coen Brothers movies.) His piece is largely about a lawsuit over whether musicians who recorded before 1972 will earn royalties on their work, since national copyright did not exist then. The streaming services and Internet radio are trying to avoid paying anything.

is by producer T-Bone Burnett, known for his work in television (Nashville) and film (the Coen Brothers movies.) His piece is largely about a lawsuit over whether musicians who recorded before 1972 will earn royalties on their work, since national copyright did not exist then. The streaming services and Internet radio are trying to avoid paying anything.

Several lawsuits have been filed over the last year on behalf of artists and copyright owners against Pandora or Sirius XM to rectify this disregard for what legacy artists created. It turns out that recordings made before 1972 are protected by state law and newer recordings are protected by federal law. It’s a distinction that matters to lawyers but not to those who make music for a living — or their fans. And why should it?

Burnett also sees the issue in broader terms: “For the last 20 years we’ve witnessed an assault on the arts by the technology community — especially when it comes to music.”

These issues are central to my book; I get into them in some detail then. And I’ll be writing over the music-streaming fight in the near future.

UPDATE: British folk/punk Billy Bragg and Ed O’Brien of Radiohead have just spoken out about what they describe as YouTube bullying indie labels for their upcoming streaming service. Story here.

June 4, 2014

Massenet’s “Thais” at LA Opera

WHAT kind of love is the truest and most enduring, spiritual or erotic? That’s a theme that echoes through the opera I saw the other day. My experience with Massenet is limited, so I have little sense of what to expect. But Thais, which stars Placido Domingo as an earnest and confused fourth-century monk seeking out an Alexandrian courtesan, hit me pretty hard. I’m sorry to see this season of Los Angeles Opera draw to a close.

The opera is set during a fascinating and unsteady period in which the Mediterranean world was teetering between paganism and early Christianity, and both main characters – Domingo’s monk and the high-class prostitute Thais, portrayed by Georgian soprano Nino Machaidze – represent the different positions. The opera, which starts slow but includes some lovely arias and smart sets, is a kind of complex dialogue between these two worlds and their two points of view: Is bodily lust of the love of Christ the truest path?

My colleague Mark Swed calls it “an exotic, erotic antique” and praises the opera here. He also describes Domingo’s monk’s trip through the desert to take Thais to a convent.

Raab’s production treats the desert as a treacherous terrain for the monk. Sand dunes are shaped as breasts (shades of Sanderson?). The monks, their white tie and tails in tatters, sit among theatrical ruins of broken seats and phallic Greek columns that revolve around the sandy breasts. By the time Athanaël accepts his inner lust, Thaïs has already exchanged depravity for saintly deprivation as a ticket to sainthood.

I was impressed at how rich and resonant Domingo’s voice was. A few years ago, he told me his voice was darkening, and we hear the results of that in robust fashion here. And Machaidze’s entrance, visually and musically, floored me.

More than anything, the opera made me think of poetry – Wallace Stevens’ “Sunday Morning,” which sways between hedonism and devotion, and the verse of Cavafy, who came from Alexandria and was fascinated with the way the world changed when the old gods gave way to a new one.

It’s not many operas that can summon so much to it. There are too more productions in Los Angeles, tonight and on Saturday.

Caveat: While I’ve reviewed books, jazz records and rock bands, I am not a professional critic but an culture reporter and enthusiast of the arts. I have linked to a credentialed critic; the distinction does, to me, matter.

Irony’s Dead End: Guest Columnist

DOES irony leads us anywhere valuable? How does cultural postmodernism fit in? These are questions guest columnist Lawrence Christon gets into today, extending a much-discussed essay by David Foster Wallace (pictured). Despite being a child of Letterman, novelists like Pynchon, and the indie-rock’90s, I’m increasingly agreeing with opponents of irony like Lewis Hyde, who said, “Irony has only emergency use. Carried over time it is the voice of the trapped who have come to enjoy their cage.”

Here’s Larry.

The subject keeps popping up. Newsweek, The Economist, Salon, The Atlantic, more than once in Slate. The general tone about irony is that it’s become the general tone, not just of artistic expression and cultural discourse, but of everyday life. Wink-wink. Double-entendre. Air quotes. The snide remark, the sitcom comebacker.

Nobody asks ,“What’s the catch?” anymore. Is it because everything, one way or another, is the catch?

Matt Ashby and Brendan Carroll recently wrote in Slate, ”…cynicism saturates popular culture, and it has afflicted contemporary art by way of postmodernism and irony…”

What is it about irony that draws the attention of the cultural commentariat, as though it’s been isolated as  a new pathology. How new is it? Aristophanes formalized it. Socrates used it, even at his own trial. Cervantes made a parable of it. Swift broadened it into a human meta-condition. Societies gripped in rigid social and political hierarchies made it obligatory, as with Moliere, La Rouchefoucauld, Shaw, Wilde and Gogol. If not hierarchies, then conditions. Joseph Heller made “Catch-22” a universal reference for rational lunacy. So did, unwittingly, Donald Rumsfeld (and the Bush II administration’s proclamation of its own reality).

a new pathology. How new is it? Aristophanes formalized it. Socrates used it, even at his own trial. Cervantes made a parable of it. Swift broadened it into a human meta-condition. Societies gripped in rigid social and political hierarchies made it obligatory, as with Moliere, La Rouchefoucauld, Shaw, Wilde and Gogol. If not hierarchies, then conditions. Joseph Heller made “Catch-22” a universal reference for rational lunacy. So did, unwittingly, Donald Rumsfeld (and the Bush II administration’s proclamation of its own reality).

What’s the difference between contemporary irony and the O.E.D definition: “A figure of speech in which the intended meaning is the opposite of that expression used by the words, usually taking the form of sarcasm or ridicule…” and ”A contradictory outcome of events as if in mockery of the promise and fitness of things”?

It isn’t always just snark. Irony is mutable. It’s a base for comedy’s conjunction of the irreconcilable. It’s a philosophical posture toward intractable hypocrisy, as in Camus’ line, “The tragedy of America is that the appearance of justice conceals the reality of injustice.” It’s a nimble form of self-reparation, of psychic release from the inescapable.

That’s where postmodern irony comes in. Pop culture is the inescapable condition, culminating in the 1990s, when low culture and high culture went to war in a horrible mismatch in which the high was seized and condemned, not to death, but scorned irrelevance. And not just culture, incidentally. In “Amusing Ourselves to Death,” Neil Postman warned that the way things are going, mere derision and not force of arms will be enough to overthrow governments.

If irony is the new quotidian, it’s been building for a long time. Pound, Auden, Mumford, Dada and the Absurdists. George Trow of “The Context of No Context.” Warhol, the idiot savant, whose Delphic utterances seem somehow fitting in an era when cultural authority crumbles before the fatuous sneer, and there’s no one to explicate what’s phony and what’s real. In what other age have we had something as absurd as the reality show, whose mere category is an oxymoron?

All roads on the topic lead to David Foster Wallace’s summary 1993 essay, “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction.”

“Make no mistake,” Wallace writes. “Irony tyrannizes us.”

“Irony’s useful for debunking illusions, but most of the illusion-debunking in the U.S. has now been done and redone. All we seem to want to do is keep ridiculing the stuff. Postmodern irony and cynicism’s become an end in itself. “

Wallace’s hope was for the rise of an anti-rebel who would risk the dismissive ennui of the ironist in speaking for (one assumes) conviction, sane belief, ethical reality, hope, community, God, meaning; not as a sap or square, but as someone who understands what was once called the forces of darkness and might now be called the forces of negation, breakdown. One who joins in, conscious of the struggle. There are those people. Why don’t they count? In “Waiting for Godot,” Vladimir says to Estragon (or maybe it’s the other way around), “We kept out appointment. How many can say that?” The answer? “Billions.”

People have complained about means of communications before, beginning when epics and legends were written down instead of memorized. But nothing has gone farther than commercial television to cheapen and exploit every basic human value out there while bleeding into the general category of Media, which has colonized the consciousness of generations. Now we have TV’s extension, ubiquitous screens, to mirror the phenomenon. “America is great…it’s the individual that’s dead,” said Paddy Chayefsky in 1976’s “Network.” That may still be a premature post-mortem, but the relentlessness of a monetized, celebrity-driven, factionalized, out-of control, in-your-face, warp-speed world has given us no place to go except in the shifting crawl space of irony.

Let’s take it for what it is, no longer a development, but a chronic symptom. What does it say about art and the people who make it, aka the creative class?

Irony is detachment. Art is engagement. Right now they’re in a toxic mix.

Lawrence Christon, Guest Columnist

June 3, 2014

The Withering of College Radio

COLLEGE radio did an enormous amount to power the indie- and alt-rock movements, as well as to create havens on campuses. But is it now being crushed? That’s the argument behind a Salon story timed to the loss of music programming at Georgia State’s WRAS in Atlanta, as “GSU announced an agreement to hand over WRAS’s 100,000 watt signal to Georgia Public Broadcasting for 14 hours a day, from 5 a.m. to 7 p.m.” Which means: “The student-produced programming that WRAS has broadcast during those hours since 1971 will now be confined to an Internet stream.”

timed to the loss of music programming at Georgia State’s WRAS in Atlanta, as “GSU announced an agreement to hand over WRAS’s 100,000 watt signal to Georgia Public Broadcasting for 14 hours a day, from 5 a.m. to 7 p.m.” Which means: “The student-produced programming that WRAS has broadcast during those hours since 1971 will now be confined to an Internet stream.”

A group trying to save the station’s student programming has made this video.

College radio stations — at Wesleyan’s WESU, Chapel Hill’s WXYC, Loyola Marymount’s KXLU, and others — have meant a lot to me over the years; they helped make me a zealous music fan. The local programming also helps provide a sense of place.

WRAS was among the first stations to play Outkast, R.E.M., and Indigo Girls. More broadly, great bands like the Smiths and the Pixies were largely ignored by American commercial radio, and found their audience through college stations. It still matters today for both musicians and off-the-mainstream bands.

Before the Internet conquered the world, college radio was the most reliable way to hear new underground music. Seventies punk grew into ’80s college rock and ’90s indie rock in seclusion at the left end of the FM dial, while the commercial radio stations and mainstream music industry that so smugly dismissed them chased trends and cycled through formats. College radio filled a vital gap, and although it has diminished in the face of 21st century technology, college radio stations are still as valuable as ever.

Beyond letting students gain experience on FM radio or serving as a social club for students who aren’t into sports or Greek culture, college radio is still one of the easiest entry points into subcultures ignored by mainstream media. It provides college students and teenagers bored with the pop music that’s played everywhere else with a window into a secret and more honest world. It isn’t just for the young, though; college radio is for anybody bored by the artless sounds and repetitive playlists of commercial radio.

I don’t know the details of the deal at WRAS, and I’ a longtime fan of NPR’s talk and news programming, which sounds like it will replace the student-run music programming. In Los Angeles, we a lucky enough to have KCRW and KPCC. Do folks in the rest of the country feel this crisis is serious? If so, please weigh in.

June 2, 2014

The Amazon Fight: David Carr and Malcolm Gladwell Weigh In

THIS fight between Amazon and the Hachette publishers doesn’t seem to be going away. And it may be damaging the online booksellers’ “brand,” says David Carr in the New York Times.

As the uproar grows, Amazon is learning that while it may own the publishing industry with a 40 percent market share of all new books sold, according to Publishers Weekly, it doesn’t own the debate. By blocking inventory, Amazon has become the less-than-everything store. Books may be a small fraction of what it sells, but books are precious, troves of speech, not just products for commerce. They were also the linchpin of the company’s early march to retail dominance. The symbolism is profound.

Carr also quotes James Patterson, who said, at BookExpo, “If Amazon’s not a monopoly, it’s the beginning of one. If this is to be the new American way, this has to be changed, by law if necessary.”

Bestselling writer Malcolm Gladwell has also broken his silence here.

It’s sort of heartbreaking when your partner turns on you. Over the past 15 years, I have sold millions of dollars’ worth of books on Amazon, which means I have made millions of dollars for Amazon. I would have thought I was one of their best assets. I thought we were partners in a business that has done well. This seems an odd way to treat someone who has made you millions of dollars.

Meanwhile, Jack Shafer — long one of the most credible and independent-minded critics of press and media, says he’s appalled by Amazon’s recent behavior, especially its silence in the press, and is cancelling his account.

One would think with that many hooks into me, I’d be more an Amazon slave than a customer. But that’s not so. Thanks to the company’s recent non-response to criticism that it’s abusing its market power — a silence that’s consistent with Amazon’s we’ll only-talk-if-we-want-to-promote-something media policy — I’ve made the easy decision to turn my back on the world’s biggest store.

This is especially striking since Shafer is a pro-business libertarian with little patience for moral grandstanding. If he’s pissed, too, things are bad.

June 1, 2014

The Internet and the Future with Jaron Lanier

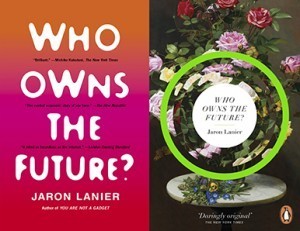

THE technologist and Internet skeptic Jaron Lanier is someone I speak to every few months whether I need to or not — he’s got some of the sharpest sense of how digital technology has reshaped life for the creative class and the larger middle class it sits inside. It helps that he’s also an experimental/classical musician who collects tons of weird old instruments.

The other day we spoke about Amazon, Kickstarter, income inequality, and last year’s hit book, Who Owns the Future?, recently out in paperback. That Salon Q+A is here.

May 30, 2014

Are Human Tastemakers Waging a Comeback?

THE phrase “we love you people” may have a new resonance: Apple’s purchase of Beats may mean Silicon Valley may be turning toward actual people as “curators” over the faceless algorithms it’s been using. Years into a process by which your bookstore or record store clerk found himself made obsolete by an Amazon recommendation, this is a rare victory for the human race in general and the creative class in particular. The catch is that for a technology company to be interested in you, you’ve got to be as famous as Dr. Dre.

In any case, this is the upshot of a New York Times story, “What the Beats Deal Says About Apple: It Loves Tastemakers.” Here’s Farhad Manjoo:

If Silicon Valley is known, in the popular imagination, as a place bent on replacing human judgment with algorithmic efficiency, Apple wants to hold itself up as the one tech company that stands proudly against that trend. The firm has long played up personal dimension of tech. But the Beats d

eal, as well as several recent hires from the realms of luxury fashion and design, point to the firm’s growing interest in human curation and, especially, culturally-savvy expertise. Apple is doubling down on tastemakers.

He quotes Apple’s Tim Cook praising Beats’ system of having celebrities like Dre and Jimmy Iovine shape the lists. “It’s something that a technology company alone wouldn’t do,” Cook told him. “Everybody would be focused on the zeroes and ones and how to make it machine learning, and forget about the human approach to it.”

Well, this is better than letting a machine do everything, I guess. (And for what it’s worth, Dre’s The Chronic is one of the best albums of all time; the guy has good taste.) I still miss the people who worked in bookstores and record shops, though, in the pre-winner-take-all era.

Scott Timberg's Blog

- Scott Timberg's profile

- 7 followers