Scott Timberg's Blog, page 29

September 3, 2014

Alex Ross on the Physicality of Music

THE New Yorker’s classical music critic is one of the least stodgy and most forward-looking of writers; he got in on blogging early and thinks classical music and digital technology are natural allies. But even he has reservations about the disappearance of records and CDs into the cloud. His new piece, about “The pleasures and frustration of listening online,” is well worth reading.

The idiosyncrasies of aging critics aside, there are legitimate questions about the aesthetics and the ethics of streaming. Spotify is notorious for its chaotic presentation of track data. One recording of the Beethoven Ninth is identified chiefly by the name of the soprano, Luba Orgonášová; I had to click again and scrutinize a stamp-size reproduction of the album cover to determine the name of the conductor, John Eliot Gardiner. A deeper issue is one of economic fairness. Spotify and Pandora have sparked protests from artists who find their royalty payments insultingly small. In 2012, the indie-rock musician Damon Krukowski reported that his former band Galaxie 500 received songwriting royalties of two hundredths of a cent for each play of its most popular track on Spotify, with performance royalties adding a pittance more.

Then comes my favorite line in the piece:

Spotify has assured critics that artists’ earnings will rise as more people subscribe. In other words, if you give

us dominance, we will be more generous—a somewhat chilly proposition.

He concludes this way, talking about a record label that has put out a Leon Fleisher (pictured) recital he quite likes:

Bridge Records, a family-run concern, has placed most of its releases on Spotify and other streaming services, and you can have equally intense encounters there. But only by buying the albums are you likely to help the label stay in business.

September 2, 2014

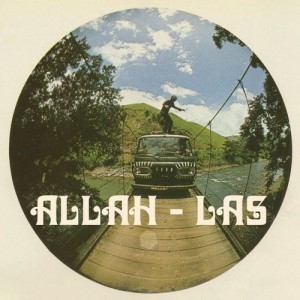

An Interview with the Allah-Las

ONE of the best bands going these days is an LA group who met at Amoeba Music on Sunset. Their records sound like lost tracks from the West Coast garage collection Nuggets. And unlike a lot of revivalists, these guys can put it across live and make the music sound not retro but somehow timeless.

Your humble blogger corresponded with the Allah-Las right before their Sept. 4 show at the Santa Monica pier.

Most of you guys met, I think, while working at Amoeba. Did your time there – with all that access to rare music and an environment of fellow music lovers – shape what you do with the band at all?

Matt, Miles and Spencer went to high school together. While working at Ameoba, Matt and Spencer met Pedrum.

Having access to a library of music allowed us to easily find and get into lots of records that we wouldn’t have been able to otherwise

You’ve got a song on the new record called “Ferus Gallery,” the most important spot for LA art in the ‘60s. To what extent does West Coast history – art and architecture in particular – inspire your stuff?

Los Angeles has made such a unique mark on the world of art, design and architecture. Like much of Los Angeles history, Ferus Gallery, was an important place and movement that doesn’t get the recognition it deserves. We have interests that inspire us and we have weaved then into our sound, song tittles and artwork.

Do the bands on the Nuggets collections and other garage-rock collections have an important place for you guys? I hear that tradition as much as I hear the Byrds and Arthur Lee in your songs.

Yeah there is definitely a unanimous love for ‘60s garage rock between us, especially the stuff that came out of LA around that time. Hearing Nuggets for the first time was almost like a revelation. It’s a starting point for an endless pursuit of rare and interesting records from that world.

How do you that distinctive Allah-Las sound? Looks like your lead singer plays mostly hollow-bodies and semi-hollows. Do you use vintage guitars? Tube amps? Is there a lot of reverb or delay pedals, etc.?

We try to use instrumentation that complements each other to create a balanced and full sound. We have been playing together long enough to know how to do that with tones as well as perfo rmance. We don’t try to outshine or play over one another – that has been something that has shaped our sound all along. We do happen to like older guitars, tube amps, and our penchant for reverb is no secret.

rmance. We don’t try to outshine or play over one another – that has been something that has shaped our sound all along. We do happen to like older guitars, tube amps, and our penchant for reverb is no secret.

You play this kind of garage/psych blend about as well as can be imagined. I wonder if you’ll find, a few years down the road, that you’ve mined this style pretty thoroughly.

If that’s the case, we won’t have any qualms about moving on. We’re not die-hard anything, we simply make music that sounds like something we’d like to listen to. However, we have been digging for records from this era and genre for many years and have yet to come to any sort of end to the findings.

Can we expect the next phase of the Allah-Las to involve rockabilly, or glam rock, or post-punk? Or does it feel like there’s a lot of room left where you guys are aiming?

We don’t really conceptualize our music in terms of genre or style – like we mentioned, we simply make music that sounds like something we would listen to. We haven’t listened to those specific types of music for many years, and it doesn’t seem to be the direction our tastes are leading us, so it’s highly likely there will never be rockabilly, glam rock, or post-punk in our music.

The Allah-Las release their new LP, Worship the Sun, on Sept. 16. They play the Santa Monica Pier on Sept. 4, Amoeba Music (Los Angeles) on Sept. 5, and embark on a tour of Europe soon after. They return to a series of shows in the U.S. and Canada in November.

September 1, 2014

David Lowery: The Internet is a Cargo Cult

TODAY your humble blogger speaks to the musicians’ rights advocate and gets into some new territory — not just the way music streaming hurts artists, but the US government’s complicity in the current mess, the feckless Department of Justice, and the irrational way people view the Internet in general. Here’s Lowery in my Salon story:

The Internet has become cargo cult. People worship the Internet like a cargo cult. It’s this thing that they have that brings them free stuff, and they think it’s magic. It’s beyond rational thought and reason, right? And they have no sense that behind all that free stuff are the drowned ships and sailors. They don’t want to hear that behind the way you get this free stuff, some really actually fucked-up things have happened to individuals and their individual rights.

The occasion for this interview was a lawsuit about royalties for music recorded pre-1972, which Camper Van Lowery thinks has major consequences that will become clear over time. Some advocates of streaming — including those inside the services — have said that these musicians never expected royalties and don’t need to receive them. Lowery’s response:

I mean, if Pandora is going to stream these things and if Sirius is going to broadcast these things, why shouldn’t they get paid? We’re America, we’re a

fair country. We’re not a country like China, where we just go, “Here’s a politically well-connected elite, we’re just going to hand them the rights to something that somebody created.” Just so the politically well-connected can get richer. It’s really funny to me — look, I’m not really a lefty or liberal, I’m basically a little right of center in my politics — and it’s just funny to see consumers sort of rallying around the rights of corporations and against the rights of individuals.

And on a holiday made possible by the protests of workers, we wish everyone a happy Labor Day.

August 27, 2014

One Publisher Takes on Amazon

IT’S hard to know what an author or publisher should do when faced with Amazon’s dominance of the market: It’s hard to withdraw from a distributor who handles so large a portion of book (especially e-book) sales. But just as several small record labels have pulled their music from Spotify and other streaming services, the Oklahoma-based Educational Development Corporation, decided enough was enough.

A Slate story, “How One Publisher Ditched Amazon and Succeeded,” looks at what led Randall White to back out.

“Remember Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, when they’re on the cliff and getting ready to jump and one guy says, ‘I can’t swim?’” asks the folksy 72-year old, referring to the classic Robert Redford–Paul Newman film. “And the other guy says, ‘What are you worried about? The fall’s going to kill you.’”

That was essentially the situation White found himself in, watching helplessly as EDC’s revenues were steadily eaten away by competition from world’s most successful—and most aggressive—online retailer. “We were selling more to Amazon but our business kept declining,” he says, describing a dip of some 40 percent in one division alone. “I’m thinking, ‘What can I do here? This is crazy.’ You had to fix it, or you’re going to die anyway.”

It’s financially difficult — maybe impossible — for larger publishers to do this. The story concludes by wondering if EDC is anomalous or if other publishers can make a similar move. “The more important lesson may be to align themselves more aggressively the few local bookstores that still remain in business—probably the only entities more threatened by Amazon than publishers are. A strong alliance accompanied by a noisy publicity push might at least put them in a more advantageous negotiating position the next time Amazon comes around looking for better terms.”

We’ll keep watching.

August 26, 2014

Will the Internet Ever Get Less Nasty?

BY now, anyone who writes for a living knows the kind of nasty comments and chatter that accompanies almost any public utterance. (This seems like a cross between the hostility that’s bred on places like Fox News and the larger “snark” culture, with an extra layer of nastiness unique to the Internet.) How did it happen, what are the consequences for our public discourse, and can it ever get any better?

Is the Internet — often compared to the Wild West — just going through a Deadwood phase, with a gentler, more civilized state to come?

A number of scribes have mused on Internet trolls lately, in part because of the social-media retreat by Robin Williams’ daughter. But this piece, is my favorite of them, and not just because it was written by someone close to me. Sara Scribner writes:

Although the initial promise of the Internet was that it was a noncommercial, alternative space where anyone could have a public forum, there is clearly something about the structure of the Internet and what happens to people when they are using a computer that taps into something deep, dark, com

pletely judgmental and furious. The worry is that the fury will reshape our online world. Will the Internet become a nasty, brutish place where only the bullies can find a voice? Is there a chance for civility and free speech online?

For what it’s worth, I’ve been amazed over the months I’ve written this blog just how civil and smart the comments and discussion has been here, even when people disagree with me or other readers. I hope and trust we can all keep it that way.

August 25, 2014

Journalism’s Phony Golden Age

IT was only, I guess, a matter of time before the digital utopians started telling us — including laid off scribes — how great journalism has gotten. The latest is a Wired piece, “How the Smartphone Ushered in a Golden Age of Journalism. (It’s venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, and not the Wired writer, who calls it a “golden age.”)

Certainly, a very selective reading of the most hopeful developments — there’s good work being done in many places, The New Yorker still comes out every week, we have high hopes for Glenn Greenwald’s new site, and soon — would make it seem like things are humming along.

But if you look at the newsrooms cut in half, the state capitols with almost no reporters watching them, and the papers that continue to fold, the suggestion of a golden age is just ludicrous. Salon’s Andrew Leonard gets it right here, where he refers to the way several billionaires have recently invested serious sums in news organizations:

But what kind of money is coming out of it? A true golden age of journalism, if it is to last more than a few ephemeral years subsidized by check-writing billionaires and venture-capital speculation, will require that publishers make a profit and writers and reporters can make a decent living.

But I’m not hearing from a whole lot of happy writers. If you are lucky, you might be able to command a freelance pay rate that hasn’t budged in 30 years. But more people than ever work for nothing.

Yes, there are a handful of high-profile start-ups making waves, but it’s not at all clear that they’ve replaced the hundreds and thousands of metro and fore

ign desk reporter jobs that have vanished in the last decade… And “nationwide, the number of full-time reporters covering state capitals was cut almost in half between 2003 and 2009.

The recent Clay Shirky post, Last Call, looks at just how dire things are for print journalism, especially when you look at the collapse of print ad revenue.

If you are a one-percenter in Silicon Valley — and believe us “content providers” should work for free — I expect things look a lot different.

August 22, 2014

Endgame: Culture and Suicide

HOW has Western literary culture dealt with the ending of life? How do we see it now? Today guest columnist Larry Christon looks at a bundle of complex and painful issues, as recent as the death of Robin Williams and as old as the work of Albert Camus and perhaps Shakespeare. This one is not for the faint of heart.

“ENDGAME,” By Lawrence Christon

Albert Camus’ famous declaration in “The Myth of Sisyphus,” “There is only one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide,” was addressed to the war-torn, blood-soaked 20th century, “A world of inverted values,” as he put it. But it still rings in ours, most piercingly in the recent death of not just a public figure, but one beloved beyond the dumb show of celebrity.

Out of simple decency and respect for a brilliant and generous-spirited man, not to mention his family, I’m not going to offer any presumptuous speculation on the whys of Robin Williams’ ultimate act, except to suggest that the cause for banishing the shadow between idea and execution, that swift and irreversible decision to make the final leap, is indeed unknowable. And that too demands respect.

You’d hardly think it, though, judging by the outpouring of opinion, and tacit denunciation, by most of the chattering class, that basically comes down to this: If only he’d taken his meds; if only he’d sought help. The fact that he did doesn’t seem to matter. The shock and grief that’s followed a popular figure richly endowed with the gift of laughter is heartfelt and appropriate. But the underlying notion that the canon ‘gainst self-slaughter is based on the precepts of the mental health industry, which now govern our social discourse, seems to me to reduce the scope of what it is to be human.

I’m not tilting my lance at mental health experts, nor do I discount the crucial value of therapy and psychotropic drugs in relieving millions of the horrible confusi on, helplessness and agony of mental disorder. I worked in a mental hospital during the era of Thorazine, Compazine, electroshock therapy and lobotomy, and saw what it is to be a ghostly, fitful remnant of a self, completely unable to function in the normal comings and goings of everyday life.

on, helplessness and agony of mental disorder. I worked in a mental hospital during the era of Thorazine, Compazine, electroshock therapy and lobotomy, and saw what it is to be a ghostly, fitful remnant of a self, completely unable to function in the normal comings and goings of everyday life.

And who cannot feel the mortal anguish underlying author David Foster Wallace’s words when he began his 1998 essay, “The Depressed Person,” by observing, “The depressed person was in terrible and unceasing emotional pain, and the impossibility of sharing or articulating this pain was itself a component of the pain and a contributing factor in its essential horror.” Wallace capitulated to that horror by taking his life in 2008.

For most of recorded history, philosophy and the arts have reflected both the mutability and constancy of human experience. Suicide, in a social context, was usually seen as an act of redemption for dishonor or disgrace, as when the Roman fell on his sword, or a Japanese committed seppuku. In an excellent piece that ran August 18 in the Los Angles Times, theater critic Charles McNulty took up the theme by contrasting epochs in drama, citing the conditions that made Antigone’s suicide differ from Willy Loman’s, for example. All roads to modernity lead through, Hamlet, however, about whom McNulty writes:

Suicidal preoccupation in Hamlet is paradoxically a source of his humanity. What draws us to him is the eloquence with which he articulates hidden feelings that most sentient human beings have shared at one point or another in their long and sometimes overwhelming journey. Most of us, thank heaven, won’t commit suicide, but one reason suicides fascinate and appall us is that they raise fears about the boundary between black thoughts and irrevocable action.

But something happened beginning in the late 19th century and continuing into ours: The revolutions and discoveries in art were nothing compared to the phenomenal advances made by science and technology, in which anything goes as long as you can prove it. Science, not philosophy or the intuitions of art, became the arbiter and ultimate authority on truth. The unintended byproduct, which is still with us, is the assumption that what is not demonstrable is not true.

Renaissance man, the measure of all things, shrank to a consumer, a taker of selfies. The poet, as one critic noted, has been reduced to making “mere facticity a secular creed.” Hart Crane’s line, “As silent as a mirror is believed/Realities pass in silence by,” makes no sense to our modern, pragmatic mind. Hence our discomfort with the mystery of the human heart, our conversion of ineffable mind into chemically tractable brain. Not every psychotherapist feels this way, incidentally. Well-respected L.A.-based Dr. Terrence McBride e-mails, “…all our emotions, moods and behavior are not due to brain chemistry. Mostly, it’s the other way around.”

My younger brother, who had AIDS, opened his veins in a bathtub of our shared apartment. Afterwards, a nurse attending him said, “His needs were greater than yours.” Who asked you? I thought angrily. Since when does death have to answer to a banal hierarchy of needs? But I respected my brother’s choice, even as I cleaned up his blood.

Instead of complaining and pointing a moral, why can’t we just mourn the dead and leave them in the peace they so desperately craved?

August 21, 2014

German Writers Stand Up to Amazon

WHETHER opposition to the online octopus is growing and spreading is hard to tell, but some of the anger we’ve seen in the US literary community seems to be driving authors in the German-speaking world as well. A New York Times story reports that more than a thousand German-language authors have written a letter of protest. The whole thing is complex, but it’s similar in some ways to the tussle here between Amazon and the Hachette publishers. From the Times:

The writers, supported by several hundred artists and readers, have signed an open letter to Amazon, the online retailing giant, accusing it of manipulating its recommended reading lists and lying to customers about the availability

of books as retaliation in a dispute over e-book prices.

“Amazon’s customers have, until now, had the impression that these lists are not manipulated and they could trust Amazon. Apparently that is not the case,” read the letter, which was to be sent to Amazon and was to appear in leading publications in Austria, Germany and Switzerland on Monday. “Amazon manipulates recommendation lists. Amazon uses authors and their books as a bargaining chip to exact deeper discounts.”

Part of what’s interesting about this — and it comes a bit late in the story for my taste — is that Germany, unlike the States, has a series of laws that help bookstores and small publishers thrive. (Among them are laws that limit the way books can be discounted, which on the surface cost consumers more, but which protect the broader publishing ecology.)

People like me have long hoped the the U.S. would adapt some variation of what Germany has. This story makes clear that even with that, Amazon has expanded inside Germany and in nearby nations like Poland. Those indie bookstores and small publishers may not last much longer.

A sad coda to this is the likely extinction of the last Shakespeare & Co. bookstores from New York City. Publishers Weekly: “After news surfaced last week that the company’s Broadway store is closing, PW learned that the one remaining Shakespeare & Co. outpost, on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, may close as well.”

It’s competition from online as well as high rents — all-too-familiar killers.

August 20, 2014

Will Indie Film Survive?

ONE of the casualties of our current cultural situation is the erosion of the middle — the middle class, the midlist author, the middlebrow, and the mid-budget film. Independent film, with its interest in boundary pushing and risk-taking, may not seem to belong in that company, but it’s vulnerable to all the same forces. The New York Times tells us that Tom Bernard of Sony Pictures Classics recently compared indie film to Petey the Puffin, who, “on a widely watched webcam video, starved to death in Maine before a horrified audience because climate change had disrupted the food chain.” (The environment for indie, that story tells us, may be getting worse, because of a change involving the Toronto Film Festival.)

A more complex but almost as dispiriting tale comes from Ted Hope, an indie producer of legend who helped make many of the films of Hal Hartley, The Ice Storm, Happiness, Todd Haynes’s Safe, and much more. It’ a kind of roller coaster reading this excerpt from Hope’s new book on Soft Skull, Hope For Film .

.

Again and again, his basic optimism and urge to innovate get overcome by events. Generally, his ambition was to make films with “midsized budgets—low enough that you could take creative risks, but high enough that you could compete at the Academy Awards if you delivered the goods.”

At one point, he writes:

Even as I watched my income drop over a four- to five-year period, I didn’t think I needed to do a complete 180-degree

shift. I was still getting good movies made, although there was no denying they were being seen less, having less impact, and were less satisfying, as a result. I was also starting to feel that I wasn’t being realistic about the changes that were coming to the industry. Or perhaps how these changes had already arrived.

And the recession was not as temporary as he’d expected:

The downturn lasted more than three years. And the indie world wasn’t changing for the better; it actually got harder to finance or sell those films. And yet, it was becoming easier, at least on a technical level, to make interesting movies on increasingly smaller budgets.The optimist in me believed that both the indie-film culture and the indie business would bounce back, that this was just a blip caused by the economic crisis and that people (and the industry) would again hunger for quality tales told well. So I set myself a three-year goal of trying to make five films, regardless of budget, provided at least two had a budget of at least three million dollars so that I could earn enough to support myself and an assistant.

One of the the things I like about Hope’s assessment is the way he looks — to use the metaphor I started this discussion with — at the larger ecology, in this case the sustenance provided by journalistic criticism. Here is he again:

People trust the people they’re closest to.That’s the great crime in the firing of so many film critics in America over the last few years. Local audiences trusted those local critics; after years of engagement, the critics had developed a relationship with their audience, which came to know when to take something with a grain of salt and when to follow their advice like a close friend. Those critics may blog, but blogging does not have the same authority as when they were the voice of their local community.

We’re eager to see Hope’s book, which sounds like it has some concerns in common with (shameless plug ahead) our own Culture Crash.

August 18, 2014

Allah-Las and Woods in Echo Park

IT was 1966 again on Friday night, as two of today’s best retro-rock bands, the folky Woods and the garage-psych Allah-Las played at the free Echo Park Rising Festival. Ideally I would have taken in more of the festival, but these were two really strong sets.

I was there to see LA’s Allah-Las, whose reverb-heavy take on folk rock — they seem equally grounded in the Byrds, Love, and the obscure but wonderful bands from the Nuggets collections — has made them one of my favorite newish groups. The show didn’t let me down — these guys have not only mastered a perfect ’60s sound,which they can put across live, they’ve got songs with memorable hooks and a guitarist ripping out great, echoey riffs and fills.

Here is a song from their self-titled debut album. Their sound and look is a bit rougher now; I’ve got their new album (due next month) and it’s excellent. These guys met while working at the Amoeba Music on Sunset, and they have not only endless musical references, but a gift for tunefulness as well.

I first heard the Allah-Las on a British compilation of contemporary Byrds-derived bands. Also on that disc was the Brooklyn-to-upstate New York band Woods, whose stuff I know only slightly. This was the night’s big surprise.

These guys have a great old-school sound as well — more influenced by the ’70s and Neil Young — but were almost as gripping live. Mostly, I was struck by how good the songwriting was — melodies that surprise you but unfold naturally. Love the weird modal stuff the guitarist was pulling out.

I dig their songs like Hand it Out and Moving to the Left. I’m headed to the record store to grab their last few albums, the new one especially. Long may they wave.

Scott Timberg's Blog

- Scott Timberg's profile

- 7 followers